User login

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Is AI a Cure for Clinician Burnout?

The practice of medicine is evolving rapidly, with clinicians facing enhanced pressure to maximize productivity while managing increasingly complex patients and related clinical documentation. Indeed, clinicians are spending less time seeing patients, and more time in front of a computer screen.

Despite the many rewards of clinical medicine, rates of clinical practice attrition have increased among physicians in all specialties since 2013 with enhanced administrative burdens identified as a prominent driver. Among its many applications, artificial intelligence (AI) has immense potential to reduce the administrative and cognitive burdens that contribute to clinician burnout and attrition through tools such as AI scribes – these technologies have been rapidly adopted across healthcare systems and are already in use by ~30% of physician practices. The hope is that AI scribes will significantly reduce documentation time, leading to improvements in clinician wellbeing and expanding capacity for patient care. Indeed, some studies have shown up to a 20-30% improvement in documentation efficiency.

So, is AI a cure for physician burnout? The answer depends on what is done with these efficiency gains. If healthcare organizations respond to this enhanced efficiency by increasing patient volume expectations rather than allowing clinicians to recapture some of this time for meaningful work and professional wellbeing, it could create a so-called “workload paradox” where modest time savings are offset by greater productivity demands and the cognitive burden of reviewing AI-generated errors. that prioritizes clinician well-being and patient safety in addition to productivity.

In our final issue of 2025, we highlight a recent RCT from Annals of Internal Medicine finding that fecal microbiota transplantation is at least as effective as vancomycin in treating primary C. difficile infection. In this month’s Member Spotlight, we feature Andrew Ofosu, MD, MPH (University of Cincinnati Health), who stresses the importance of transparency and compassion in communicating effectively with patients, particularly around complex diagnoses. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our December issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

The practice of medicine is evolving rapidly, with clinicians facing enhanced pressure to maximize productivity while managing increasingly complex patients and related clinical documentation. Indeed, clinicians are spending less time seeing patients, and more time in front of a computer screen.

Despite the many rewards of clinical medicine, rates of clinical practice attrition have increased among physicians in all specialties since 2013 with enhanced administrative burdens identified as a prominent driver. Among its many applications, artificial intelligence (AI) has immense potential to reduce the administrative and cognitive burdens that contribute to clinician burnout and attrition through tools such as AI scribes – these technologies have been rapidly adopted across healthcare systems and are already in use by ~30% of physician practices. The hope is that AI scribes will significantly reduce documentation time, leading to improvements in clinician wellbeing and expanding capacity for patient care. Indeed, some studies have shown up to a 20-30% improvement in documentation efficiency.

So, is AI a cure for physician burnout? The answer depends on what is done with these efficiency gains. If healthcare organizations respond to this enhanced efficiency by increasing patient volume expectations rather than allowing clinicians to recapture some of this time for meaningful work and professional wellbeing, it could create a so-called “workload paradox” where modest time savings are offset by greater productivity demands and the cognitive burden of reviewing AI-generated errors. that prioritizes clinician well-being and patient safety in addition to productivity.

In our final issue of 2025, we highlight a recent RCT from Annals of Internal Medicine finding that fecal microbiota transplantation is at least as effective as vancomycin in treating primary C. difficile infection. In this month’s Member Spotlight, we feature Andrew Ofosu, MD, MPH (University of Cincinnati Health), who stresses the importance of transparency and compassion in communicating effectively with patients, particularly around complex diagnoses. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our December issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

The practice of medicine is evolving rapidly, with clinicians facing enhanced pressure to maximize productivity while managing increasingly complex patients and related clinical documentation. Indeed, clinicians are spending less time seeing patients, and more time in front of a computer screen.

Despite the many rewards of clinical medicine, rates of clinical practice attrition have increased among physicians in all specialties since 2013 with enhanced administrative burdens identified as a prominent driver. Among its many applications, artificial intelligence (AI) has immense potential to reduce the administrative and cognitive burdens that contribute to clinician burnout and attrition through tools such as AI scribes – these technologies have been rapidly adopted across healthcare systems and are already in use by ~30% of physician practices. The hope is that AI scribes will significantly reduce documentation time, leading to improvements in clinician wellbeing and expanding capacity for patient care. Indeed, some studies have shown up to a 20-30% improvement in documentation efficiency.

So, is AI a cure for physician burnout? The answer depends on what is done with these efficiency gains. If healthcare organizations respond to this enhanced efficiency by increasing patient volume expectations rather than allowing clinicians to recapture some of this time for meaningful work and professional wellbeing, it could create a so-called “workload paradox” where modest time savings are offset by greater productivity demands and the cognitive burden of reviewing AI-generated errors. that prioritizes clinician well-being and patient safety in addition to productivity.

In our final issue of 2025, we highlight a recent RCT from Annals of Internal Medicine finding that fecal microbiota transplantation is at least as effective as vancomycin in treating primary C. difficile infection. In this month’s Member Spotlight, we feature Andrew Ofosu, MD, MPH (University of Cincinnati Health), who stresses the importance of transparency and compassion in communicating effectively with patients, particularly around complex diagnoses. We hope you enjoy this and all the exciting content in our December issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Managing Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Agonists: Practical Insights From Dr. Bridget E. Shields

Managing Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Agonists: Practical Insights From Dr. Bridget E. Shields

Are you seeing any increase or trends in cutaneous adverse effects related to the use of GLP-1 agonists in your practice?

DR. SHIELDS: The use of GLP-1 agonists is increasing substantially across numerous populations. Patients are using these medications not only for weight management and diabetes control but also for blood pressure modulation and cardiovascular risk reduction. The market size is expected to grow at a rate of about 6% until 2027. While severe cutaneous adverse effects still are considered relatively rare with GLP-1 agonist use, mild adverse effects are quite common. Dermatologists should be familiar with these effects and how to manage them. Rare but serious cutaneous reactions include morbilliform drug eruptions, dermal hypersensitivity reactions, panniculitis, and bullous pemphigoid. It is thought that some GLP-1 agonists may cause more skin reactions than others; for example, exenatide extended-release has been associated with cutaneous adverse events more frequently than other GLP-1 agonists in a recent comprehensive literature review.

Do you see a role for dermatologists in monitoring or managing the downstream dermatologic effects of GLP-1 agonists over the next few years?

DR. SHIELDS: Absolutely. When patients develop a drug eruption, bullous pemphigoid, or eosinophilic panniculitis, dermatologists are going to be the ones to diagnose and manage therapy. Awareness of these adverse effects is crucial to timely and thoughtful discussions surrounding medication discontinuation vs a “treat through” approach.

Do you recommend coordinating with endocrinologists or obesity medicine specialists when managing shared patients on GLP-1s (particularly if skin concerns arise)?

DR. SHIELDS: Yes. This is crucial to patient success. Co-management can provide clarity around the indication for therapy and allow for a thoughtful risk-benefit discussion with the patient, primary care physician, endocrinologist, cardiologist, etc. In my practice, I have found that many patients do not want to stop therapy even when they develop cutaneous adverse effects. There are options to transition therapy or treat through in some cases, but having a comprehensive monitoring and therapy plan is critical.

Have you encountered cases in which rapid weight loss from GLP-1s worsened conditions such as loose skin, cellulite, or facial lipoatrophy, leading to new aesthetic concerns? How would you recommend counseling and/or treating affected patients?

DR. SHIELDS: Accelerated facial aging is a noticeable adverse effect in patients who undergo treatment with GLP-1 agonists, especially when used off-label for weight loss. Localized loss of facial fat can result in altered facial proportions and excess skin. There are multiple additional mechanisms that may underlie accelerated facial aging in patients on GLP-1s, and really we are just beginning to scratch the surface of why and how this happens. Understanding these mechanisms will open the door to downstream preventive and therapeutic options. If patients experience new aesthetic concerns, I currently work with them to adjust their medication to slow weight loss, recommend improved nutrition and hydration, encourage exercise and weight training to maintain muscle mass, and engage my cosmetic dermatology colleagues to discuss procedures such as dermal fillers.

All patients starting GLP-1 agonists should be thoroughly counseled on risks and adverse effects of their medication. These are well reported and should be considered carefully. Starting with lower medication dosing in conjunction with slow escalation and careful monitoring can be helpful in combatting these adverse effects.

Are you seeing any increase or trends in cutaneous adverse effects related to the use of GLP-1 agonists in your practice?

DR. SHIELDS: The use of GLP-1 agonists is increasing substantially across numerous populations. Patients are using these medications not only for weight management and diabetes control but also for blood pressure modulation and cardiovascular risk reduction. The market size is expected to grow at a rate of about 6% until 2027. While severe cutaneous adverse effects still are considered relatively rare with GLP-1 agonist use, mild adverse effects are quite common. Dermatologists should be familiar with these effects and how to manage them. Rare but serious cutaneous reactions include morbilliform drug eruptions, dermal hypersensitivity reactions, panniculitis, and bullous pemphigoid. It is thought that some GLP-1 agonists may cause more skin reactions than others; for example, exenatide extended-release has been associated with cutaneous adverse events more frequently than other GLP-1 agonists in a recent comprehensive literature review.

Do you see a role for dermatologists in monitoring or managing the downstream dermatologic effects of GLP-1 agonists over the next few years?

DR. SHIELDS: Absolutely. When patients develop a drug eruption, bullous pemphigoid, or eosinophilic panniculitis, dermatologists are going to be the ones to diagnose and manage therapy. Awareness of these adverse effects is crucial to timely and thoughtful discussions surrounding medication discontinuation vs a “treat through” approach.

Do you recommend coordinating with endocrinologists or obesity medicine specialists when managing shared patients on GLP-1s (particularly if skin concerns arise)?

DR. SHIELDS: Yes. This is crucial to patient success. Co-management can provide clarity around the indication for therapy and allow for a thoughtful risk-benefit discussion with the patient, primary care physician, endocrinologist, cardiologist, etc. In my practice, I have found that many patients do not want to stop therapy even when they develop cutaneous adverse effects. There are options to transition therapy or treat through in some cases, but having a comprehensive monitoring and therapy plan is critical.

Have you encountered cases in which rapid weight loss from GLP-1s worsened conditions such as loose skin, cellulite, or facial lipoatrophy, leading to new aesthetic concerns? How would you recommend counseling and/or treating affected patients?

DR. SHIELDS: Accelerated facial aging is a noticeable adverse effect in patients who undergo treatment with GLP-1 agonists, especially when used off-label for weight loss. Localized loss of facial fat can result in altered facial proportions and excess skin. There are multiple additional mechanisms that may underlie accelerated facial aging in patients on GLP-1s, and really we are just beginning to scratch the surface of why and how this happens. Understanding these mechanisms will open the door to downstream preventive and therapeutic options. If patients experience new aesthetic concerns, I currently work with them to adjust their medication to slow weight loss, recommend improved nutrition and hydration, encourage exercise and weight training to maintain muscle mass, and engage my cosmetic dermatology colleagues to discuss procedures such as dermal fillers.

All patients starting GLP-1 agonists should be thoroughly counseled on risks and adverse effects of their medication. These are well reported and should be considered carefully. Starting with lower medication dosing in conjunction with slow escalation and careful monitoring can be helpful in combatting these adverse effects.

Are you seeing any increase or trends in cutaneous adverse effects related to the use of GLP-1 agonists in your practice?

DR. SHIELDS: The use of GLP-1 agonists is increasing substantially across numerous populations. Patients are using these medications not only for weight management and diabetes control but also for blood pressure modulation and cardiovascular risk reduction. The market size is expected to grow at a rate of about 6% until 2027. While severe cutaneous adverse effects still are considered relatively rare with GLP-1 agonist use, mild adverse effects are quite common. Dermatologists should be familiar with these effects and how to manage them. Rare but serious cutaneous reactions include morbilliform drug eruptions, dermal hypersensitivity reactions, panniculitis, and bullous pemphigoid. It is thought that some GLP-1 agonists may cause more skin reactions than others; for example, exenatide extended-release has been associated with cutaneous adverse events more frequently than other GLP-1 agonists in a recent comprehensive literature review.

Do you see a role for dermatologists in monitoring or managing the downstream dermatologic effects of GLP-1 agonists over the next few years?

DR. SHIELDS: Absolutely. When patients develop a drug eruption, bullous pemphigoid, or eosinophilic panniculitis, dermatologists are going to be the ones to diagnose and manage therapy. Awareness of these adverse effects is crucial to timely and thoughtful discussions surrounding medication discontinuation vs a “treat through” approach.

Do you recommend coordinating with endocrinologists or obesity medicine specialists when managing shared patients on GLP-1s (particularly if skin concerns arise)?

DR. SHIELDS: Yes. This is crucial to patient success. Co-management can provide clarity around the indication for therapy and allow for a thoughtful risk-benefit discussion with the patient, primary care physician, endocrinologist, cardiologist, etc. In my practice, I have found that many patients do not want to stop therapy even when they develop cutaneous adverse effects. There are options to transition therapy or treat through in some cases, but having a comprehensive monitoring and therapy plan is critical.

Have you encountered cases in which rapid weight loss from GLP-1s worsened conditions such as loose skin, cellulite, or facial lipoatrophy, leading to new aesthetic concerns? How would you recommend counseling and/or treating affected patients?

DR. SHIELDS: Accelerated facial aging is a noticeable adverse effect in patients who undergo treatment with GLP-1 agonists, especially when used off-label for weight loss. Localized loss of facial fat can result in altered facial proportions and excess skin. There are multiple additional mechanisms that may underlie accelerated facial aging in patients on GLP-1s, and really we are just beginning to scratch the surface of why and how this happens. Understanding these mechanisms will open the door to downstream preventive and therapeutic options. If patients experience new aesthetic concerns, I currently work with them to adjust their medication to slow weight loss, recommend improved nutrition and hydration, encourage exercise and weight training to maintain muscle mass, and engage my cosmetic dermatology colleagues to discuss procedures such as dermal fillers.

All patients starting GLP-1 agonists should be thoroughly counseled on risks and adverse effects of their medication. These are well reported and should be considered carefully. Starting with lower medication dosing in conjunction with slow escalation and careful monitoring can be helpful in combatting these adverse effects.

Managing Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Agonists: Practical Insights From Dr. Bridget E. Shields

Managing Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Agonists: Practical Insights From Dr. Bridget E. Shields

Update on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Young Children

Update on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Young Children

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with skin barrier impairment and immune system dysregulation.1 Development of AD in young children can present challenges in determining appropriate treatment regimens. Natural remedies for AD often are promoted on social media over traditional treatments, including topical corticosteroids (TCSs), which can contribute to corticophobia.2 Dermatologists play a critical role not only in optimizing topical therapy but also addressing patient interest in natural approaches to AD, including diet-related questions. This article outlines the role of diet and probiotics in pediatric AD and reviews the topical treatments currently approved for this patient population.

Diet and Probiotics

With a growing focus on natural therapies for AD, dietary interventions have come to the forefront. A prevalent theme among patients and their families is addressing gut health and allergic triggers. Broad elimination diets have not shown clinical benefit in patients with AD regardless of age,3 and in children, they may result in nutritional deficiencies, poor growth, and increased risk for IgE-mediated food allergies.4 If a true food allergy is identified based on positive IgE and an acute clinical reaction, elimination of the allergen may provide some benefit.5

The link between gut microbiota and skin health has driven an interest in the role of probiotics in the treatment of pediatric AD. A meta-analysis of 20 articles concluded that, whether administered to infants or breastfeeding mothers, use of probiotics overall led to a significant reduction in AD risk in infants (P=.001). Lactobacillus and mixed strains were effective.6 While broad elimination diets are not used to treat AD, probiotic supplementation can be considered for prevention of AD.

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are the cornerstone of AD treatment; however, corticophobia among patients is on the rise, leading to poor adherence and suboptimal control of AD.7 Mild cutaneous adverse effects (AEs) including skin atrophy, striae, and telangiectasias may occur. Rarely, systemic AEs occur due to absorption of TCSs into the bloodstream, mainly with application of potent steroids over large body surface areas or under occlusion.8 When the optimal potency of a TCS is chosen and used appropriately, incidence of AEs from TCS use is very low.9

Counseling parents about risk factors that can lead to AEs during treatment with TCSs and formulating regimens that minimize these risks while maintaining efficacy increases adherence and outcomes. Pulse maintenance dosing of TCSs typically involves application 1 to 2 times weekly to areas of the skin that are prone to frequent outbreaks. Pulse maintenance dosing can reduce the incidence of AD flares while also decreasing the total amount of topical medication needed as compared to the reactive approach alone, thereby reducing risk for AEs.8

Steroid-Sparing Topical Treatments

Although TCSs are considered first-line agents, recently there has been an advent of steroid-sparing topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for pediatric patients with AD, including topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists. Offering steroid-sparing agents in these patients can help ease parental anxiety regarding TCS overuse.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors—Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% are approved for patients aged 2 years and older and have anti-inflammatory and antipruritic effects equivalent to low-potency TCS. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% is approved for patients aged 16 years and older with similar efficacy to a midpotency TCSs. Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% often are used off-label in children younger than 2 years, as supported by clinical trials showing their safety and efficacy.10

Topical calcineurin inhibitors can replace or supplement TCSs, making TCIs a desirable option for avoidance of steroid-related AEs. The addition of a TCI to spot treatment or a pulse regimen in a young patient can reassure them and their caregivers that the provider is proactively reducing the risk of TCS overuse. The largest barrier to TCI use is the FDA’s black box warning based on the oral formulation of tacrolimus, citing a potential increased risk for lymphoma and skin cancer; however, there is no evidence for substantial systemic absorption of topical pimecrolimus or tacrolimus.11 Large task-force reviews have found no association between TCI use and development of malignancy.12,13 Based on the current data, counseling patients and their caregivers that this risk primarily is theoretical may help them more confidently integrate TCIs into their treatment regimen. Burning and tingling may occur in a minority of pediatric patients using TCIs for AD. Applying the medication to open wounds or inflamed skin increases the risk for stinging, but pretreatment with a short course of TCSs before transitioning to a TCI may boost tolerance.14

Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors—Crisaborole ointment 2%, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, is approved for children aged 3 months and older with mild to moderate AD. Its use has been more limited than TCSs and TCIs, as local irritation including stinging and burning can occur in up to 50% of patients.15 One study comparing crisaborole 2% with tacrolimus 0.03% revealed greater improvement with tacrolimus.16 A second phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for once-daily use in children aged 6 years and older with mild to moderate AD is roflumilast cream 0.15%. Roflumilast reduces eczema severity and pruritus, with AEs also limited to application-site stinging and burning.17

Janus Kinase Inhibitor—Ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, a Janus kinase inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA since 2023 for twice-daily use in children aged 12 years and older with AD. Similar to TCIs, ruxolitinib cream carries a black box warning. Short-term safety data on ruxolitinib cream have revealed low levels of ruxolitinib concentration in plasma18; however, long-term studies on topical Janus kinase inhibitors for AD in pediatric and adult populations are lacking. To reduce the risk for systemic absorption, recommendations include limiting usage to 60 g per week and limiting treatment to less than 20% of the body surface area.19 Ruxolitinib has efficacy similar to or possibly superior to triamcinolone 0.1%.20 Ruxolitinib is emerging as a promising nonsteroidal option that potentially is highly efficacious and well tolerated without cutaneous AEs.

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist—Tapinarof cream 1% is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that has been approved by the FDA since 2024 for children aged 2 years and older as a once-daily treatment for moderate to severe AD. Adverse events include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache, which are mostly mild or moderate.21

Final Thoughts

Topical management of pediatric AD includes traditional therapy with TCSs and newer steroid-sparing agents, which can help address corticophobia. Anticipatory guidance regarding the safety and long-term effects of individual therapies is critical to ensuring patient adherence to treatment regimens. Probiotics may help prevent pediatric AD, but future studies are needed to determine their role in treatment.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Voillot P, Riche B, Portafax M, et al. Social media platforms listening study on atopic dermatitis: quantitative and qualitative findings. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:E31140.

- Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-264.

- Rustad AM, Nickles MA, Bilimoria SN, et al. The role of diet modification in atopic dermatitis: navigating the complexity. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:27-36.

- Khan A, Adalsteinsson J, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:135-144.

- Chen L, Ni Y, Wu X, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of atopic dermatitis in infants from different geographic regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2931-2939.

- Herzum A, Occella C, Gariazzo L, et al. Corticophobia among parents of children with atopic dermatitis: assessing major and minor risk factors for high TOPICOP scores. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6813.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Callen J, Chamlin S, Eichenfield LF, et al. A systematic review of the safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:203-221.

- Reitamo S, Rustin M, Ruzicka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone butyrate ointment in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:547-555.

- Thaçi D, Salgo R. Malignancy concerns of topical calcineurin inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:52-56.

- Berger TG, Duvic M, Van Voorhees AS, et al. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. report of the AAD Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:818-823.

- Fonacier L, Spergel J, Charlesworth EN, et al. Report of the Topical Calcineurin Inhibitor Task Force of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1249-1253.

- Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:495-504.

- Lin CPL, Gordon S, Her MJ, et al. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1451-1453.

- Ryan Wolf J, Chen A, Wieser J, et al. Improved patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes distinguish tacrolimus 0.03% from crisaborole in children with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:1364-1372.

- Simpson EL, Eichenfield LF, Alonso-Llamazares J, et al. Roflumilast cream, 0.15%, for atopic dermatitis in adults and children: INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:1161-1170.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016.

- Sidbury R, Alikhan A, Bercovitch L, et al. Guidelines of carefor the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:E1-E20.

- Sadeghi S, Mohandesi NA. Efficacy and safety of topical JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in paediatrics and adults: a systematic review. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:599-610.

- Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily: significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults and children down to 2 years of age in the pivotal phase 3 ADORING trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:457-465.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with skin barrier impairment and immune system dysregulation.1 Development of AD in young children can present challenges in determining appropriate treatment regimens. Natural remedies for AD often are promoted on social media over traditional treatments, including topical corticosteroids (TCSs), which can contribute to corticophobia.2 Dermatologists play a critical role not only in optimizing topical therapy but also addressing patient interest in natural approaches to AD, including diet-related questions. This article outlines the role of diet and probiotics in pediatric AD and reviews the topical treatments currently approved for this patient population.

Diet and Probiotics

With a growing focus on natural therapies for AD, dietary interventions have come to the forefront. A prevalent theme among patients and their families is addressing gut health and allergic triggers. Broad elimination diets have not shown clinical benefit in patients with AD regardless of age,3 and in children, they may result in nutritional deficiencies, poor growth, and increased risk for IgE-mediated food allergies.4 If a true food allergy is identified based on positive IgE and an acute clinical reaction, elimination of the allergen may provide some benefit.5

The link between gut microbiota and skin health has driven an interest in the role of probiotics in the treatment of pediatric AD. A meta-analysis of 20 articles concluded that, whether administered to infants or breastfeeding mothers, use of probiotics overall led to a significant reduction in AD risk in infants (P=.001). Lactobacillus and mixed strains were effective.6 While broad elimination diets are not used to treat AD, probiotic supplementation can be considered for prevention of AD.

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are the cornerstone of AD treatment; however, corticophobia among patients is on the rise, leading to poor adherence and suboptimal control of AD.7 Mild cutaneous adverse effects (AEs) including skin atrophy, striae, and telangiectasias may occur. Rarely, systemic AEs occur due to absorption of TCSs into the bloodstream, mainly with application of potent steroids over large body surface areas or under occlusion.8 When the optimal potency of a TCS is chosen and used appropriately, incidence of AEs from TCS use is very low.9

Counseling parents about risk factors that can lead to AEs during treatment with TCSs and formulating regimens that minimize these risks while maintaining efficacy increases adherence and outcomes. Pulse maintenance dosing of TCSs typically involves application 1 to 2 times weekly to areas of the skin that are prone to frequent outbreaks. Pulse maintenance dosing can reduce the incidence of AD flares while also decreasing the total amount of topical medication needed as compared to the reactive approach alone, thereby reducing risk for AEs.8

Steroid-Sparing Topical Treatments

Although TCSs are considered first-line agents, recently there has been an advent of steroid-sparing topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for pediatric patients with AD, including topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists. Offering steroid-sparing agents in these patients can help ease parental anxiety regarding TCS overuse.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors—Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% are approved for patients aged 2 years and older and have anti-inflammatory and antipruritic effects equivalent to low-potency TCS. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% is approved for patients aged 16 years and older with similar efficacy to a midpotency TCSs. Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% often are used off-label in children younger than 2 years, as supported by clinical trials showing their safety and efficacy.10

Topical calcineurin inhibitors can replace or supplement TCSs, making TCIs a desirable option for avoidance of steroid-related AEs. The addition of a TCI to spot treatment or a pulse regimen in a young patient can reassure them and their caregivers that the provider is proactively reducing the risk of TCS overuse. The largest barrier to TCI use is the FDA’s black box warning based on the oral formulation of tacrolimus, citing a potential increased risk for lymphoma and skin cancer; however, there is no evidence for substantial systemic absorption of topical pimecrolimus or tacrolimus.11 Large task-force reviews have found no association between TCI use and development of malignancy.12,13 Based on the current data, counseling patients and their caregivers that this risk primarily is theoretical may help them more confidently integrate TCIs into their treatment regimen. Burning and tingling may occur in a minority of pediatric patients using TCIs for AD. Applying the medication to open wounds or inflamed skin increases the risk for stinging, but pretreatment with a short course of TCSs before transitioning to a TCI may boost tolerance.14

Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors—Crisaborole ointment 2%, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, is approved for children aged 3 months and older with mild to moderate AD. Its use has been more limited than TCSs and TCIs, as local irritation including stinging and burning can occur in up to 50% of patients.15 One study comparing crisaborole 2% with tacrolimus 0.03% revealed greater improvement with tacrolimus.16 A second phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for once-daily use in children aged 6 years and older with mild to moderate AD is roflumilast cream 0.15%. Roflumilast reduces eczema severity and pruritus, with AEs also limited to application-site stinging and burning.17

Janus Kinase Inhibitor—Ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, a Janus kinase inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA since 2023 for twice-daily use in children aged 12 years and older with AD. Similar to TCIs, ruxolitinib cream carries a black box warning. Short-term safety data on ruxolitinib cream have revealed low levels of ruxolitinib concentration in plasma18; however, long-term studies on topical Janus kinase inhibitors for AD in pediatric and adult populations are lacking. To reduce the risk for systemic absorption, recommendations include limiting usage to 60 g per week and limiting treatment to less than 20% of the body surface area.19 Ruxolitinib has efficacy similar to or possibly superior to triamcinolone 0.1%.20 Ruxolitinib is emerging as a promising nonsteroidal option that potentially is highly efficacious and well tolerated without cutaneous AEs.

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist—Tapinarof cream 1% is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that has been approved by the FDA since 2024 for children aged 2 years and older as a once-daily treatment for moderate to severe AD. Adverse events include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache, which are mostly mild or moderate.21

Final Thoughts

Topical management of pediatric AD includes traditional therapy with TCSs and newer steroid-sparing agents, which can help address corticophobia. Anticipatory guidance regarding the safety and long-term effects of individual therapies is critical to ensuring patient adherence to treatment regimens. Probiotics may help prevent pediatric AD, but future studies are needed to determine their role in treatment.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with skin barrier impairment and immune system dysregulation.1 Development of AD in young children can present challenges in determining appropriate treatment regimens. Natural remedies for AD often are promoted on social media over traditional treatments, including topical corticosteroids (TCSs), which can contribute to corticophobia.2 Dermatologists play a critical role not only in optimizing topical therapy but also addressing patient interest in natural approaches to AD, including diet-related questions. This article outlines the role of diet and probiotics in pediatric AD and reviews the topical treatments currently approved for this patient population.

Diet and Probiotics

With a growing focus on natural therapies for AD, dietary interventions have come to the forefront. A prevalent theme among patients and their families is addressing gut health and allergic triggers. Broad elimination diets have not shown clinical benefit in patients with AD regardless of age,3 and in children, they may result in nutritional deficiencies, poor growth, and increased risk for IgE-mediated food allergies.4 If a true food allergy is identified based on positive IgE and an acute clinical reaction, elimination of the allergen may provide some benefit.5

The link between gut microbiota and skin health has driven an interest in the role of probiotics in the treatment of pediatric AD. A meta-analysis of 20 articles concluded that, whether administered to infants or breastfeeding mothers, use of probiotics overall led to a significant reduction in AD risk in infants (P=.001). Lactobacillus and mixed strains were effective.6 While broad elimination diets are not used to treat AD, probiotic supplementation can be considered for prevention of AD.

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are the cornerstone of AD treatment; however, corticophobia among patients is on the rise, leading to poor adherence and suboptimal control of AD.7 Mild cutaneous adverse effects (AEs) including skin atrophy, striae, and telangiectasias may occur. Rarely, systemic AEs occur due to absorption of TCSs into the bloodstream, mainly with application of potent steroids over large body surface areas or under occlusion.8 When the optimal potency of a TCS is chosen and used appropriately, incidence of AEs from TCS use is very low.9

Counseling parents about risk factors that can lead to AEs during treatment with TCSs and formulating regimens that minimize these risks while maintaining efficacy increases adherence and outcomes. Pulse maintenance dosing of TCSs typically involves application 1 to 2 times weekly to areas of the skin that are prone to frequent outbreaks. Pulse maintenance dosing can reduce the incidence of AD flares while also decreasing the total amount of topical medication needed as compared to the reactive approach alone, thereby reducing risk for AEs.8

Steroid-Sparing Topical Treatments

Although TCSs are considered first-line agents, recently there has been an advent of steroid-sparing topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for pediatric patients with AD, including topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists. Offering steroid-sparing agents in these patients can help ease parental anxiety regarding TCS overuse.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors—Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% are approved for patients aged 2 years and older and have anti-inflammatory and antipruritic effects equivalent to low-potency TCS. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% is approved for patients aged 16 years and older with similar efficacy to a midpotency TCSs. Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% often are used off-label in children younger than 2 years, as supported by clinical trials showing their safety and efficacy.10

Topical calcineurin inhibitors can replace or supplement TCSs, making TCIs a desirable option for avoidance of steroid-related AEs. The addition of a TCI to spot treatment or a pulse regimen in a young patient can reassure them and their caregivers that the provider is proactively reducing the risk of TCS overuse. The largest barrier to TCI use is the FDA’s black box warning based on the oral formulation of tacrolimus, citing a potential increased risk for lymphoma and skin cancer; however, there is no evidence for substantial systemic absorption of topical pimecrolimus or tacrolimus.11 Large task-force reviews have found no association between TCI use and development of malignancy.12,13 Based on the current data, counseling patients and their caregivers that this risk primarily is theoretical may help them more confidently integrate TCIs into their treatment regimen. Burning and tingling may occur in a minority of pediatric patients using TCIs for AD. Applying the medication to open wounds or inflamed skin increases the risk for stinging, but pretreatment with a short course of TCSs before transitioning to a TCI may boost tolerance.14

Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors—Crisaborole ointment 2%, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, is approved for children aged 3 months and older with mild to moderate AD. Its use has been more limited than TCSs and TCIs, as local irritation including stinging and burning can occur in up to 50% of patients.15 One study comparing crisaborole 2% with tacrolimus 0.03% revealed greater improvement with tacrolimus.16 A second phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for once-daily use in children aged 6 years and older with mild to moderate AD is roflumilast cream 0.15%. Roflumilast reduces eczema severity and pruritus, with AEs also limited to application-site stinging and burning.17

Janus Kinase Inhibitor—Ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, a Janus kinase inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA since 2023 for twice-daily use in children aged 12 years and older with AD. Similar to TCIs, ruxolitinib cream carries a black box warning. Short-term safety data on ruxolitinib cream have revealed low levels of ruxolitinib concentration in plasma18; however, long-term studies on topical Janus kinase inhibitors for AD in pediatric and adult populations are lacking. To reduce the risk for systemic absorption, recommendations include limiting usage to 60 g per week and limiting treatment to less than 20% of the body surface area.19 Ruxolitinib has efficacy similar to or possibly superior to triamcinolone 0.1%.20 Ruxolitinib is emerging as a promising nonsteroidal option that potentially is highly efficacious and well tolerated without cutaneous AEs.

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist—Tapinarof cream 1% is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that has been approved by the FDA since 2024 for children aged 2 years and older as a once-daily treatment for moderate to severe AD. Adverse events include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache, which are mostly mild or moderate.21

Final Thoughts

Topical management of pediatric AD includes traditional therapy with TCSs and newer steroid-sparing agents, which can help address corticophobia. Anticipatory guidance regarding the safety and long-term effects of individual therapies is critical to ensuring patient adherence to treatment regimens. Probiotics may help prevent pediatric AD, but future studies are needed to determine their role in treatment.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Voillot P, Riche B, Portafax M, et al. Social media platforms listening study on atopic dermatitis: quantitative and qualitative findings. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:E31140.

- Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-264.

- Rustad AM, Nickles MA, Bilimoria SN, et al. The role of diet modification in atopic dermatitis: navigating the complexity. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:27-36.

- Khan A, Adalsteinsson J, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:135-144.

- Chen L, Ni Y, Wu X, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of atopic dermatitis in infants from different geographic regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2931-2939.

- Herzum A, Occella C, Gariazzo L, et al. Corticophobia among parents of children with atopic dermatitis: assessing major and minor risk factors for high TOPICOP scores. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6813.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Callen J, Chamlin S, Eichenfield LF, et al. A systematic review of the safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:203-221.

- Reitamo S, Rustin M, Ruzicka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone butyrate ointment in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:547-555.

- Thaçi D, Salgo R. Malignancy concerns of topical calcineurin inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:52-56.

- Berger TG, Duvic M, Van Voorhees AS, et al. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. report of the AAD Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:818-823.

- Fonacier L, Spergel J, Charlesworth EN, et al. Report of the Topical Calcineurin Inhibitor Task Force of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1249-1253.

- Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:495-504.

- Lin CPL, Gordon S, Her MJ, et al. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1451-1453.

- Ryan Wolf J, Chen A, Wieser J, et al. Improved patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes distinguish tacrolimus 0.03% from crisaborole in children with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:1364-1372.

- Simpson EL, Eichenfield LF, Alonso-Llamazares J, et al. Roflumilast cream, 0.15%, for atopic dermatitis in adults and children: INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:1161-1170.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016.

- Sidbury R, Alikhan A, Bercovitch L, et al. Guidelines of carefor the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:E1-E20.

- Sadeghi S, Mohandesi NA. Efficacy and safety of topical JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in paediatrics and adults: a systematic review. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:599-610.

- Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily: significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults and children down to 2 years of age in the pivotal phase 3 ADORING trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:457-465.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Voillot P, Riche B, Portafax M, et al. Social media platforms listening study on atopic dermatitis: quantitative and qualitative findings. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:E31140.

- Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-264.

- Rustad AM, Nickles MA, Bilimoria SN, et al. The role of diet modification in atopic dermatitis: navigating the complexity. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:27-36.

- Khan A, Adalsteinsson J, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:135-144.

- Chen L, Ni Y, Wu X, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of atopic dermatitis in infants from different geographic regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2931-2939.

- Herzum A, Occella C, Gariazzo L, et al. Corticophobia among parents of children with atopic dermatitis: assessing major and minor risk factors for high TOPICOP scores. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6813.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Callen J, Chamlin S, Eichenfield LF, et al. A systematic review of the safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:203-221.

- Reitamo S, Rustin M, Ruzicka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone butyrate ointment in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:547-555.

- Thaçi D, Salgo R. Malignancy concerns of topical calcineurin inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:52-56.

- Berger TG, Duvic M, Van Voorhees AS, et al. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. report of the AAD Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:818-823.

- Fonacier L, Spergel J, Charlesworth EN, et al. Report of the Topical Calcineurin Inhibitor Task Force of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1249-1253.

- Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:495-504.

- Lin CPL, Gordon S, Her MJ, et al. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1451-1453.

- Ryan Wolf J, Chen A, Wieser J, et al. Improved patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes distinguish tacrolimus 0.03% from crisaborole in children with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:1364-1372.

- Simpson EL, Eichenfield LF, Alonso-Llamazares J, et al. Roflumilast cream, 0.15%, for atopic dermatitis in adults and children: INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:1161-1170.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016.

- Sidbury R, Alikhan A, Bercovitch L, et al. Guidelines of carefor the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:E1-E20.

- Sadeghi S, Mohandesi NA. Efficacy and safety of topical JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in paediatrics and adults: a systematic review. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:599-610.

- Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily: significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults and children down to 2 years of age in the pivotal phase 3 ADORING trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:457-465.

Update on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Young Children

Update on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Young Children

COVID-19 Vaccines: Navigating the Chaos of Conflicting Guidance

Hi, everyone. I’m Dr Kenny Lin. I am a family physician and associate director of the Lancaster General Hospital Family Medicine Residency, and I blog at Common Sense Family Doctor.

The receding of the pandemic and the understandable desire to return to normalcy has made COVID-19 vaccines a lower priority for many of our patients. However, family physicians should keep in mind that from October 1, 2024, to September 6, 2025, COVID-19 was responsible for an estimated 3.2 to 4.6 million outpatient visits, 360,000 to 520,000 hospitalizations, and 42,000 to 60,000 deaths.

In a previous commentary, I discussed the worsening disconnect between the evidence supporting the effectiveness and safety of vaccinations and increasing reluctance of patients and parents to receive them, fueled by misinformation from federal health agencies and the packing of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) with vaccine skeptics. Since then, Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Robert F. Kennedy, Jr, has fired Dr Susan Monarez, his handpicked director of the CDC. This caused three senior CDC officials to resign in protest and precipitated further turmoil at the embattled agency.

The FDA has approved 3 updated COVID-19 vaccines targeted to currently circulating strains: an mRNA vaccine from Moderna (Spikevax) for those aged 6 months or older; an mRNA vaccine from Pfizer/BioNTech (Comirnaty) for those aged ≥ 5 years; and a protein subunit vaccine from Novavax (Nuvaxovid) for those aged ≥ 12 years. However, approvals restricting the scope of these approvals to certain high-risk groups, combined with the ACIP’s recent decision to not explicitly recommend them for any group, have complicated access for many patients.

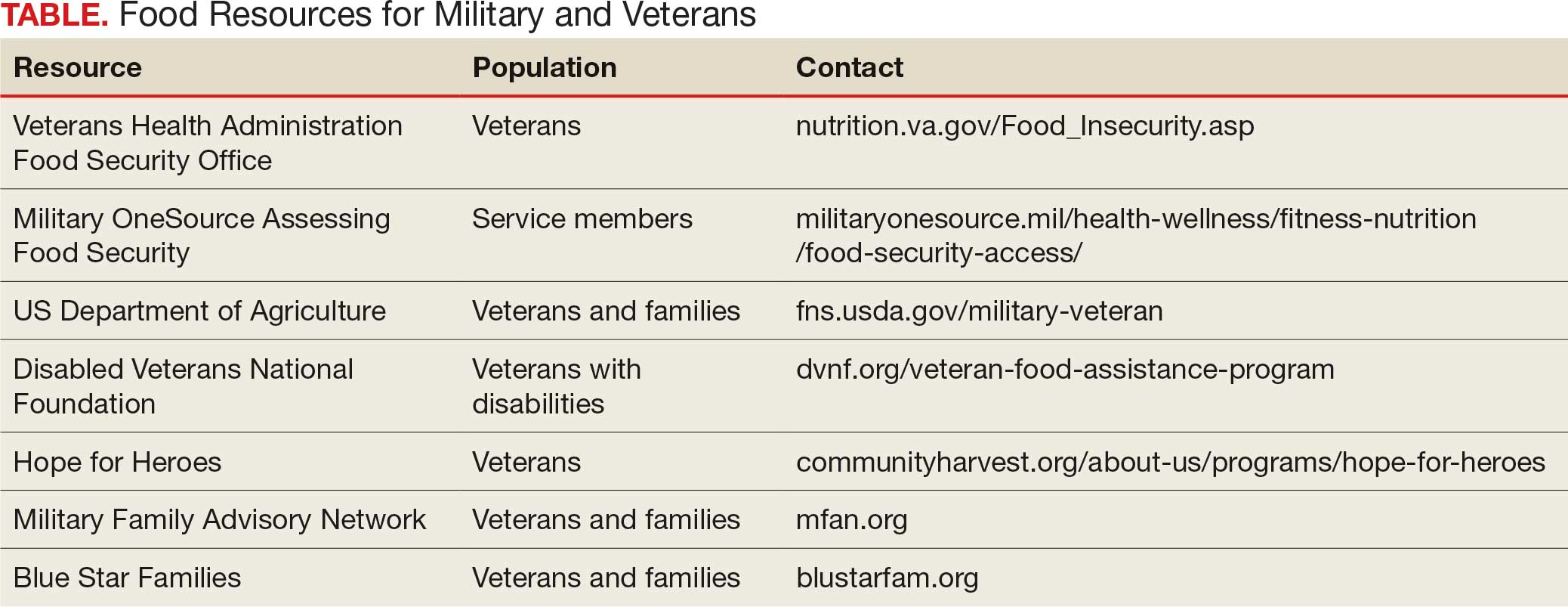

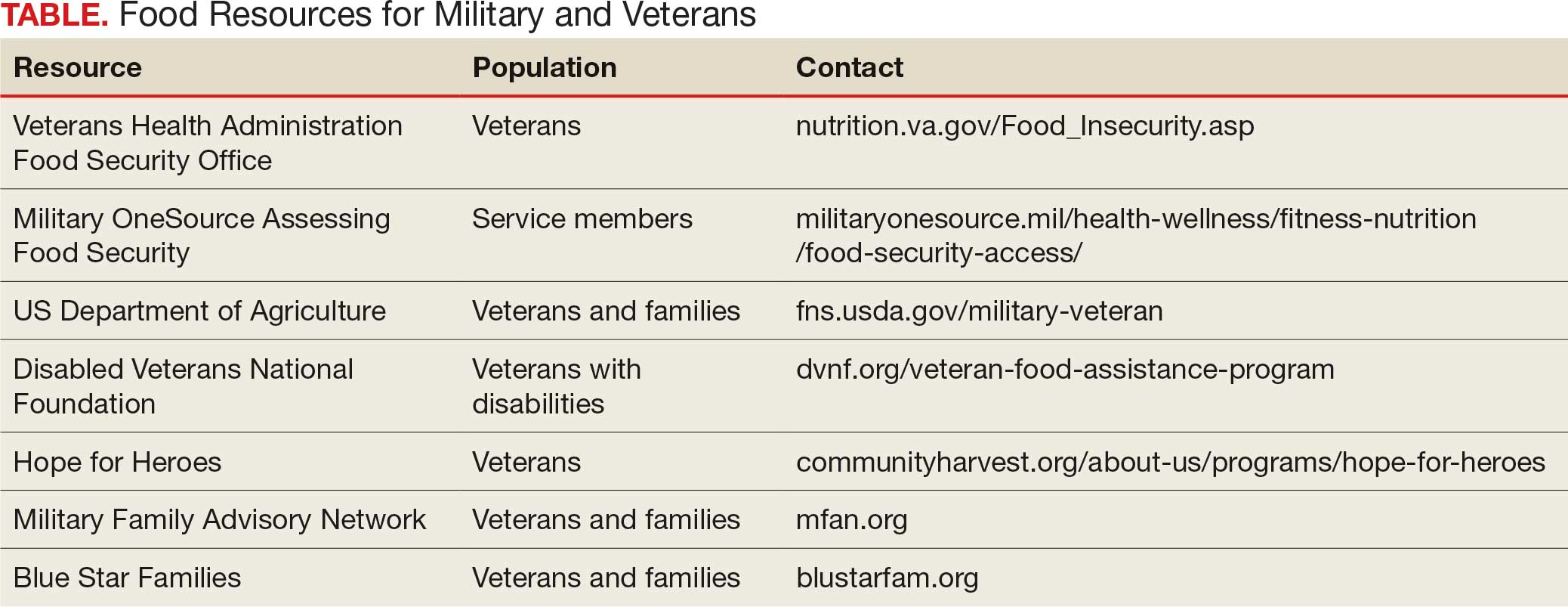

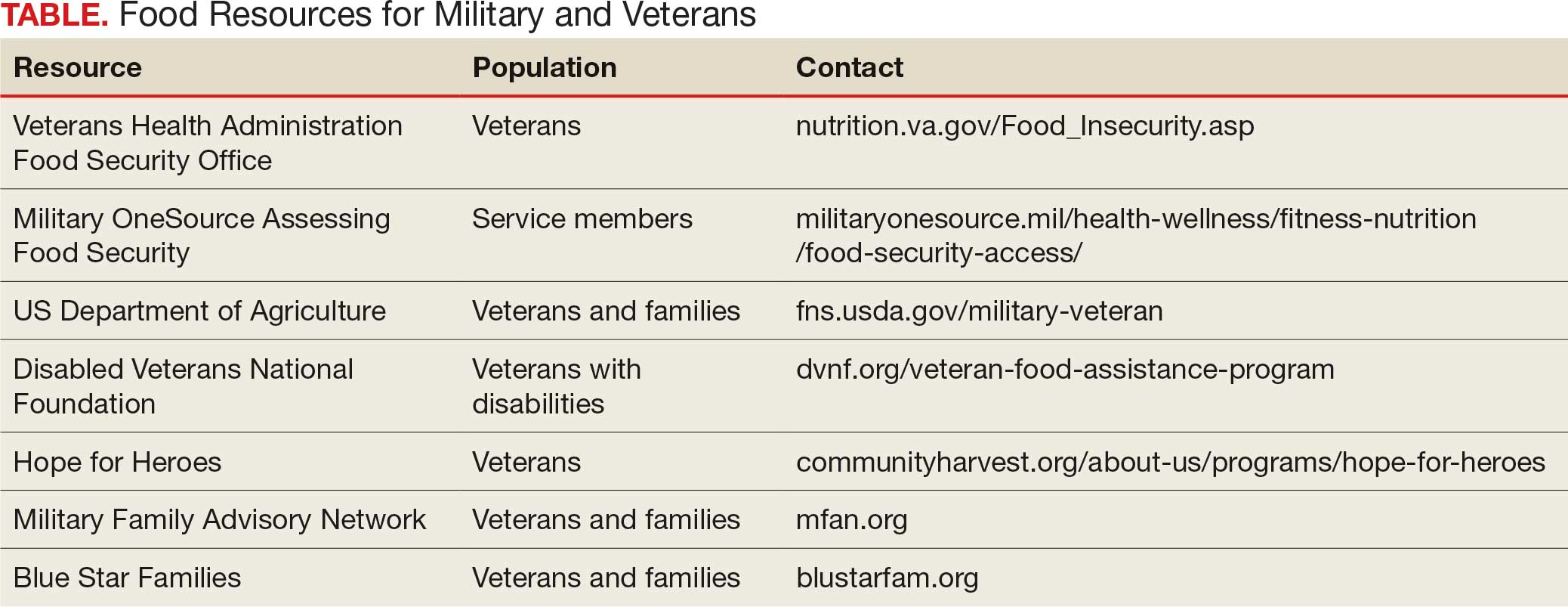

Medical groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), have published their own recommendations (Table). Of note, in opposition to the FDA and ACIP, the AAP and AAFP strongly recommend routine vaccination for children aged 6 to 23 months because they have the highest risk for hospitalization. The AAFP and ACOG both recommend COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy to protect the pregnant patient and provide passive antibody protection to their infants up to 6 months of age. The Vaccine Integrity Project’s review of 12 safety studies published since June 2024 found that mRNA vaccines were not associated with increases in any adverse maternal or infant outcomes and had a possible protective effect against preterm birth.

In my previous commentary, 70% of Medscape readers indicated that they would follow vaccination recommendations from AAP even if they differed from CDC guidance. Administering vaccines outside of FDA labeling indications (i.e., “off label”) typically requires a physician’s prescription, which will almost certainly reduce COVID-19 vaccine uptake in children and pregnant patients, given that most people received these shots in pharmacies during the 2024-25 season. CVS and Walgreens, the country’s two largest pharmacy chains, are requiring physician prescriptions or waiting for ACIP guidance to make the new vaccines available in many states. However, an increasing number of states have implemented executive orders or passed legislation to permit pharmacists to provide vaccines to anyone who wants them. For example, the Pennsylvania State Board of Pharmacy voted unanimously to issue guidance that would allow pharmacists to administer any vaccines recommended by AAFP, AAP, or ACOG.

Erosion of vaccine uptake could easily worsen the burden of illness for our patients and the health system. Navigating the unnecessarily complex landscape of COVID-19 vaccines will be challenging, but it remains worthwhile.

Risk group | FDA | ACIP/HHS | AAFP | AAP | ACOG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Adults aged > 65 | Approved | Shared decision-making | Recommend | N/A | N/A |

6 months to 64 years with high-risk condition | Approved | Shared decision-making | Recommend | Recommend | NA |

Pregnant patients | Unclear, but pregnancy included as high-risk condition | Not approved | Recommend | NA | Recommend |

Children and adults without risk factors | Not approved | Shared decision-making | Recommend for age 6-23 months and administer to all others who desire it | Recommend for age 6-23 months and administer to all others who desire it | NA |

Kenneth W. Lin, MD, MPH, Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: UpToDate; American Academy of Family Physicians; Archdiocese of Washington; Association of Prevention Teaching and Research.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Hi, everyone. I’m Dr Kenny Lin. I am a family physician and associate director of the Lancaster General Hospital Family Medicine Residency, and I blog at Common Sense Family Doctor.

The receding of the pandemic and the understandable desire to return to normalcy has made COVID-19 vaccines a lower priority for many of our patients. However, family physicians should keep in mind that from October 1, 2024, to September 6, 2025, COVID-19 was responsible for an estimated 3.2 to 4.6 million outpatient visits, 360,000 to 520,000 hospitalizations, and 42,000 to 60,000 deaths.

In a previous commentary, I discussed the worsening disconnect between the evidence supporting the effectiveness and safety of vaccinations and increasing reluctance of patients and parents to receive them, fueled by misinformation from federal health agencies and the packing of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) with vaccine skeptics. Since then, Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Robert F. Kennedy, Jr, has fired Dr Susan Monarez, his handpicked director of the CDC. This caused three senior CDC officials to resign in protest and precipitated further turmoil at the embattled agency.

The FDA has approved 3 updated COVID-19 vaccines targeted to currently circulating strains: an mRNA vaccine from Moderna (Spikevax) for those aged 6 months or older; an mRNA vaccine from Pfizer/BioNTech (Comirnaty) for those aged ≥ 5 years; and a protein subunit vaccine from Novavax (Nuvaxovid) for those aged ≥ 12 years. However, approvals restricting the scope of these approvals to certain high-risk groups, combined with the ACIP’s recent decision to not explicitly recommend them for any group, have complicated access for many patients.

Medical groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), have published their own recommendations (Table). Of note, in opposition to the FDA and ACIP, the AAP and AAFP strongly recommend routine vaccination for children aged 6 to 23 months because they have the highest risk for hospitalization. The AAFP and ACOG both recommend COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy to protect the pregnant patient and provide passive antibody protection to their infants up to 6 months of age. The Vaccine Integrity Project’s review of 12 safety studies published since June 2024 found that mRNA vaccines were not associated with increases in any adverse maternal or infant outcomes and had a possible protective effect against preterm birth.