User login

“Blind” endometrial sampling: A call to end the practice

Linda Bradley, MD: The standard in ObGyn for many years has been our reliance on the blind dilation and curettage (D&C)—it has been the mainstay for evaluation of the endometrial cavity. We know that it has risks, but most importantly, the procedure has low sensitivity for detecting focal pathology. This basic lack of confirmation of lesions makes a diagnosis impossible and patients are challenged in getting adequate treatment, and will not, since they may not know what options they have for the treatment of intrauterine pathology.

Because it is a “blind procedure,” done without looking, we don’t know the endpoints, such as when is the procedure completed, how do we know we removed all of the lesions? Let’s look at our colleagues, like GI and colorectal physicians. If a patient presents with rectal bleeding, we would perform an exam, followed by either a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. If a patient were vomiting up blood, a gastroenterologist would perform an upper endoscopy, look with a tube to see if there is an ulcer or something else as a source of the bleeding. If a patient were bleeding from the bladder, a urologist would use a cystoscope for direct inspection.

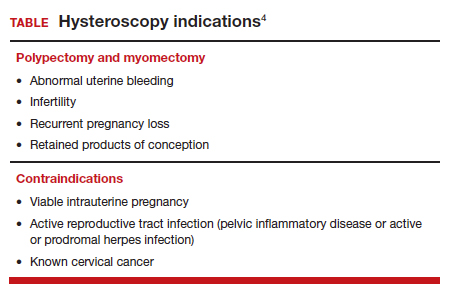

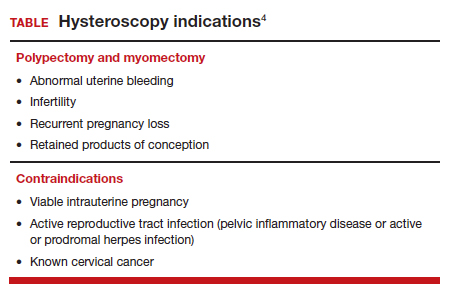

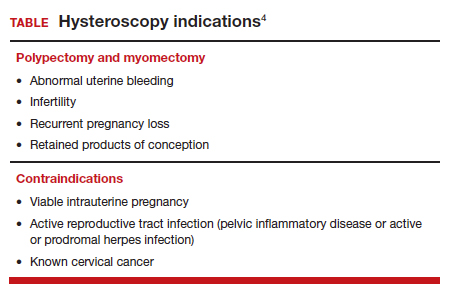

Unfortunately for gynecologists, only about 15% to 25% of us will use hysteroscopy as a diagnostic method2—a method that has excellent sensitivity in detecting endocervical disease, intrauterine disease, and proximal tubal pathology. Compared with blind curettage, we can visualize the cavity; we can sample the cavity directly; we can determine what the patient has and determine the proper surgical procedure, medical therapy, or reassurance that a patient may be offered. We often are looking at focal lesions, lesions in the uterine cavity that could be cancer, so we can make a diagnosis. Or we may be looking at small things, like endometrial hyperplasia, endocervical or endometrial polyps, retained products of conception, or fibroids. We can look at uterine pathology as well as anatomic issues and malformations—such as bicornuate or septate uterus.

I actually say, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope” because it allows us to evaluate for many things. The beauty of the new office hysteroscopes is that they are miniaturized. Doctors now have the ability to use reusable devices that are as small as 3 millimeters. There are disposable ones that are up to 3.5 to 4 millimeters in size. Gynecologists have the options to choose from reusuable rigid or flexible hysteroscopes or completely disposable devices. So, truly, we now should not have an excuse for evaluating a woman’s anatomy, especially for bleeding. We should no longer rely, as we have for the last century or more, just on blind sampling, because we miss focal lesions.

OBG Management: When was the hysteroscope first introduced into the field?

Dr. Bradley: The technology employed in hysteroscopy has been around really since the last 150+ years, introduced by Dr. Pantaleoni. We just have not embraced its usefulness in our clinical practice for many years. Today, about 15% to 25% of gynecologists practicing in the United States are performing hysteroscopy in the office.1

OBG Management: How does using hysteroscopy contribute to better patient outcomes?

Dr. Bradley: We can get a more accurate diagnosis—fewer false-negatives and a high degree of sensitivity in detecting focal lesions. With D&C, much focal pathology can be left behind. In a 2001 study, 105 symptomatic postmenopausal women with bleeding and thickened lining of the uterus greater than 5 mm on ultrasound underwent blind D&C. They found that 80% of the women had intracavitary lesions and 90% had focal lesions. In fact, 87% of the patients with focal lesions still had residual pathology after the blind D&C.3 The D&C procedure missed 58% of polyps, 50% of endometrial hyperplasia, 60% of cases of complex atypical hyperplasia, and even 11% of endometrial cancers. So these numbers are just not very good. Direct inspection of the uterus, with uninterrupted visualization through hysteroscopy, with removal of lesions under direct visualization, should be our goal.

Blind sampling also poses greater risk for things like perforation. In addition, you not only can miss lesions by just scraping the endometrium, D&C also can leave lesions just floating around in the uterine cavity, with those lesions never retrieved. With office hysteroscopy, the physician can be more successful in treating a condition because once you see what is going on in the uterine cavity, you can say, “Okay, I can fix this with a surgical procedure. What instruments do I need? How much time is it going to take? Is this a straightforward case? Is it more complicated? Do I let an intern do the case? Is this for a more senior resident or fellow?” So I think it helps to direct the next steps for surgical management and even medical management, which also could be what we call “one-stop shopping.” For instance, for directed biopsies for removal of small polyps, for patients that can tolerate the procedure a little longer, the diagnostic hysteroscopy then becomes a management, an operative procedure, that really, for myself, can be done in the office. Removal of larger fibroids, because of fluid management and other concerns, would not be done in the office. Most patients tolerate office procedures, but it also depends on a patient’s weight, and her ability to relax during the procedure.

The ultimate goal for hysteroscopy is a minimum of diagnosis, meaning in less than 2, 3 minutes, you can look inside the uterus. Our devices are 3 millimeters in size; I tell my patients, it’s the size of “a piece of spaghetti or pasta,” and we will just take a look. If we see a polyp, okay, if your office is not equipped, because then you need a different type of equipment for removal, then take her to the operating room. The patient would be under brief anesthesia and go home an hour or 2 later. So really, for physicians, we just need to embrace the technology to make a diagnosis, just look, and then from there decide what is next.

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?...

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: I think first is always be patient-centric. Let patients be prepared for the procedure. We have reading materials; our nurses explain the procedure. In the office, I try to prepare the patient for success. I let her know what is going on. A friend, family member can be with her. We have a nurse that understands the procedure; she explains it well. We have a type of bed that allows the patients’ legs to rest more comfortably in the stirrups—a leg rest kind of stirrup. We use a heating pad. Some patients like to hear music. Some patients like to have aromatherapy. We are quick and efficient, and typically just talk to the patient throughout the procedure. Although some patients don’t like this explanatory, “talkative” approach—they say, “Dr. Bradley, just do the procedure. I don’t want to know you are touching the cervix. I don’t want to know that you’re prepping. Just do it.”

But I like what we called it when I was growing up: vocal-local (talk to your patient and explain as you proceed). It’s like local anesthesia. For these procedures in the office you usually do not have to use numbing medicine or a paracervical block. Look at the patient’s age, number of years in menopause, whether or not she has delivered vaginally, and what her cervix looks like. Does she have a sexually transmitted infection or pelvic inflammatory disease? Sometimes we will use misoprostol, my personal preference is oral, but there are data to suggest that vaginal can be of help.4 We suggest Motrin, Tylenol an hour or 2 before, and we always want patients to not come in on an empty stomach. There is also the option of primrose oil, a supplement, that patients buy at the drug store in the vitamin section. It’s used for cervical softening. It is taken orally.5-7

If they want, patients can watch a video—similar to watching childbirth videos when I used to deliver babies. At some point we started putting mirrors where women could see their efforts of pushing a baby out, as it might give them more willpower to push harder. Some people don’t want to look. But the majority of women will do well in this setting. I do have a small number of women that just say, “I can’t do this in the office,” and so in those cases, they can go to the operating room. But the main idea is, even in an operating room, you are not just doing a D&C. You are still going to look inside with a hysteroscope and have a great panoramic view of what is going on, and remove a lesion with an instrument while you watch. Not a process of looking with the hysteroscope, scraping with a curettage, and thinking that you are complete. Targeted removal of focal lesions under continuous visualization is the goal.

OBG Management: Can you describe the goals of the consensus document on ending blind sampling co-created by the European Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy, AAGL, and the Global Community on Hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: Our goal for this year is to get a systematic review and guidelines paper written that speaks to what we have just talked about. We want to have as many articles about why blind sampling is not beneficial, with too many misses, and now we have new technology available. We want to speak to physicians to solve the conundrum of bleeding, with equivocal ultrasounds, equivocal saline infusion, sonograms, equivocal MRIs—be able to take a look. Let’s come up to speed like our other colleagues in other specialties that “look.” A systematic review guideline document will provide the evidence that blind D&C is fraught with problems and how often we miss disease and its inherent risk.

We need to, by itself, for most of our patients, abandon D&C because we have too many missed diagnoses. As doctors we have to be lifelong learners. There was no robot back in the day. We were not able to do laparoscopic hysterectomies, there were no MRIs. I remember in our city, there was one CT scan. We just did not have a lot of technology. The half-life of medical knowledge used to be decades—you graduated in the ‘60s, you could be a great gynecologist for the next 30 years because there was not that much going on. When I finished in the mid to late ‘80s, there was no hysteroscopy training. But I have come to see its value, the science behind it.

So what I say to doctors is, “We learn so many new things, we shouldn’t get stuck in just saying, ‘I didn’t do this when I was in training.’” And if your thought is, “Oh, in my practice, I don’t have that many cases,” you still need to be able to know who in your community can be a resource to your patients. As Maya Angelou says, “When you know better, you should do better.” And that’s where I am now—to be a lifelong learner, and just do it.

Lastly, patient influence is very important. If patients ask, “How are you going to do the procedure?” it’s a driver for change. By utilizing hysteroscopy in the evaluation of the intrauterine cavity, we have the opportunity to change the face of evaluation and treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding.●

To maximize visualization and procedure ease, schedule office hysteroscopy shortly after menstruation for reproductive-age women with regular menstrual cycles, which corresponds to timing of the thinnest endometrial lining.1 By contrast, the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle may be associated with the presence of secretory endometrium, which may mimic endometrial polyps or obscure intrauterine pathology, including FIGO type 1 and 2 submucous leiomyomas.

The following patients can have their procedures scheduled at any time, as they do not regularly cycle:

- those receiving continuous hormonal contraception

- women taking menopausal hormonal therapy

- women on progestin therapy (including those using intrauterine devices).

For patients with irregular cycles, timing is crucial as the topography of the endometrium can be variable. To increase successful visualization and diagnostic accuracy, a short course of combined hormonal contraceptives2 or progestin therapy3,4 can be considered for 10-14 days, followed by a withdrawal menses, and immediate procedure scheduling after bleeding subsides, as this will produce a thin endometrium. This approach may be especially beneficial for operative procedures such as polypectomy in order to promote complete specimen extraction.

Pharmacologic endometrial preparation also is an option and has been associated with decreased procedure time and improved patient and clinician satisfaction during operative hysteroscopy.2,3 We discourage the use of hormonal pre-treatment for diagnostic hysteroscopy alone, as this may alter endometrial histology and provide misleading results. Overall, data related to pharmacologic endometrial preparation are limited to small studies with varying treatment protocols, and an optimal regimen has yet to be determined.

References

1. The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003712.

2. Cicinelli E, Pinto V, Quattromini P, et al. Endometrial preparation with estradiol plus dienogest (Qlaira) for office hysteroscopic polypectomy: randomized pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:356-359. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2011.12.020.

3. Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Muscia V, et al. Endometrial preparation with dienogest before hysteroscopic surgery: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:661-667. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4244-1.

4. Ciebiera M, Zgliczyńska M, Zgliczyński S, et al. Oral desogestrel as endometrial preparation before operative hysteroscopy: a systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2021;86:209-217. doi:10.1159/000514584.

- Orlando MS, Bradley LD. Implementation of office hysteroscopy for the evaluation and treatment of intrauterine pathology. Obstet Gynecol. August 3, 2022. doi: 10.1097/ AOG.0000000000004898.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Epstein E, Ramirez A, Skoog L, et al. Dilatation and curettage fails to detect most focal lesions in the uterine cavity in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1131-1136. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801210.x.

- The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/ AOG.0000000000003712.

- Vahdat M, Tahermanesh K, Mehdizadeh Kashi A, et al. Evening Primrose Oil effect on the ease of cervical ripening and dilatation before operative hysteroscopy. Thrita. 2015;4:7-10. doi:10.5812/thrita.29876

- Nouri B, Baghestani A, Pooransari P. Evening primrose versus misoprostol for cervical dilatation before gynecologic surgeries: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Obstet Gynecol Cancer Res. 2021;6:87-94. doi:10.30699/jogcr.6.2.87

- Verano RMA, Veloso-borromeo MG. The efficacy of evening primrose oil as a cervical ripening agent for gynecologic procedures: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. PJOG. 2015;39:24-28.

Linda Bradley, MD: The standard in ObGyn for many years has been our reliance on the blind dilation and curettage (D&C)—it has been the mainstay for evaluation of the endometrial cavity. We know that it has risks, but most importantly, the procedure has low sensitivity for detecting focal pathology. This basic lack of confirmation of lesions makes a diagnosis impossible and patients are challenged in getting adequate treatment, and will not, since they may not know what options they have for the treatment of intrauterine pathology.

Because it is a “blind procedure,” done without looking, we don’t know the endpoints, such as when is the procedure completed, how do we know we removed all of the lesions? Let’s look at our colleagues, like GI and colorectal physicians. If a patient presents with rectal bleeding, we would perform an exam, followed by either a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. If a patient were vomiting up blood, a gastroenterologist would perform an upper endoscopy, look with a tube to see if there is an ulcer or something else as a source of the bleeding. If a patient were bleeding from the bladder, a urologist would use a cystoscope for direct inspection.

Unfortunately for gynecologists, only about 15% to 25% of us will use hysteroscopy as a diagnostic method2—a method that has excellent sensitivity in detecting endocervical disease, intrauterine disease, and proximal tubal pathology. Compared with blind curettage, we can visualize the cavity; we can sample the cavity directly; we can determine what the patient has and determine the proper surgical procedure, medical therapy, or reassurance that a patient may be offered. We often are looking at focal lesions, lesions in the uterine cavity that could be cancer, so we can make a diagnosis. Or we may be looking at small things, like endometrial hyperplasia, endocervical or endometrial polyps, retained products of conception, or fibroids. We can look at uterine pathology as well as anatomic issues and malformations—such as bicornuate or septate uterus.

I actually say, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope” because it allows us to evaluate for many things. The beauty of the new office hysteroscopes is that they are miniaturized. Doctors now have the ability to use reusable devices that are as small as 3 millimeters. There are disposable ones that are up to 3.5 to 4 millimeters in size. Gynecologists have the options to choose from reusuable rigid or flexible hysteroscopes or completely disposable devices. So, truly, we now should not have an excuse for evaluating a woman’s anatomy, especially for bleeding. We should no longer rely, as we have for the last century or more, just on blind sampling, because we miss focal lesions.

OBG Management: When was the hysteroscope first introduced into the field?

Dr. Bradley: The technology employed in hysteroscopy has been around really since the last 150+ years, introduced by Dr. Pantaleoni. We just have not embraced its usefulness in our clinical practice for many years. Today, about 15% to 25% of gynecologists practicing in the United States are performing hysteroscopy in the office.1

OBG Management: How does using hysteroscopy contribute to better patient outcomes?

Dr. Bradley: We can get a more accurate diagnosis—fewer false-negatives and a high degree of sensitivity in detecting focal lesions. With D&C, much focal pathology can be left behind. In a 2001 study, 105 symptomatic postmenopausal women with bleeding and thickened lining of the uterus greater than 5 mm on ultrasound underwent blind D&C. They found that 80% of the women had intracavitary lesions and 90% had focal lesions. In fact, 87% of the patients with focal lesions still had residual pathology after the blind D&C.3 The D&C procedure missed 58% of polyps, 50% of endometrial hyperplasia, 60% of cases of complex atypical hyperplasia, and even 11% of endometrial cancers. So these numbers are just not very good. Direct inspection of the uterus, with uninterrupted visualization through hysteroscopy, with removal of lesions under direct visualization, should be our goal.

Blind sampling also poses greater risk for things like perforation. In addition, you not only can miss lesions by just scraping the endometrium, D&C also can leave lesions just floating around in the uterine cavity, with those lesions never retrieved. With office hysteroscopy, the physician can be more successful in treating a condition because once you see what is going on in the uterine cavity, you can say, “Okay, I can fix this with a surgical procedure. What instruments do I need? How much time is it going to take? Is this a straightforward case? Is it more complicated? Do I let an intern do the case? Is this for a more senior resident or fellow?” So I think it helps to direct the next steps for surgical management and even medical management, which also could be what we call “one-stop shopping.” For instance, for directed biopsies for removal of small polyps, for patients that can tolerate the procedure a little longer, the diagnostic hysteroscopy then becomes a management, an operative procedure, that really, for myself, can be done in the office. Removal of larger fibroids, because of fluid management and other concerns, would not be done in the office. Most patients tolerate office procedures, but it also depends on a patient’s weight, and her ability to relax during the procedure.

The ultimate goal for hysteroscopy is a minimum of diagnosis, meaning in less than 2, 3 minutes, you can look inside the uterus. Our devices are 3 millimeters in size; I tell my patients, it’s the size of “a piece of spaghetti or pasta,” and we will just take a look. If we see a polyp, okay, if your office is not equipped, because then you need a different type of equipment for removal, then take her to the operating room. The patient would be under brief anesthesia and go home an hour or 2 later. So really, for physicians, we just need to embrace the technology to make a diagnosis, just look, and then from there decide what is next.

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?...

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: I think first is always be patient-centric. Let patients be prepared for the procedure. We have reading materials; our nurses explain the procedure. In the office, I try to prepare the patient for success. I let her know what is going on. A friend, family member can be with her. We have a nurse that understands the procedure; she explains it well. We have a type of bed that allows the patients’ legs to rest more comfortably in the stirrups—a leg rest kind of stirrup. We use a heating pad. Some patients like to hear music. Some patients like to have aromatherapy. We are quick and efficient, and typically just talk to the patient throughout the procedure. Although some patients don’t like this explanatory, “talkative” approach—they say, “Dr. Bradley, just do the procedure. I don’t want to know you are touching the cervix. I don’t want to know that you’re prepping. Just do it.”

But I like what we called it when I was growing up: vocal-local (talk to your patient and explain as you proceed). It’s like local anesthesia. For these procedures in the office you usually do not have to use numbing medicine or a paracervical block. Look at the patient’s age, number of years in menopause, whether or not she has delivered vaginally, and what her cervix looks like. Does she have a sexually transmitted infection or pelvic inflammatory disease? Sometimes we will use misoprostol, my personal preference is oral, but there are data to suggest that vaginal can be of help.4 We suggest Motrin, Tylenol an hour or 2 before, and we always want patients to not come in on an empty stomach. There is also the option of primrose oil, a supplement, that patients buy at the drug store in the vitamin section. It’s used for cervical softening. It is taken orally.5-7

If they want, patients can watch a video—similar to watching childbirth videos when I used to deliver babies. At some point we started putting mirrors where women could see their efforts of pushing a baby out, as it might give them more willpower to push harder. Some people don’t want to look. But the majority of women will do well in this setting. I do have a small number of women that just say, “I can’t do this in the office,” and so in those cases, they can go to the operating room. But the main idea is, even in an operating room, you are not just doing a D&C. You are still going to look inside with a hysteroscope and have a great panoramic view of what is going on, and remove a lesion with an instrument while you watch. Not a process of looking with the hysteroscope, scraping with a curettage, and thinking that you are complete. Targeted removal of focal lesions under continuous visualization is the goal.

OBG Management: Can you describe the goals of the consensus document on ending blind sampling co-created by the European Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy, AAGL, and the Global Community on Hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: Our goal for this year is to get a systematic review and guidelines paper written that speaks to what we have just talked about. We want to have as many articles about why blind sampling is not beneficial, with too many misses, and now we have new technology available. We want to speak to physicians to solve the conundrum of bleeding, with equivocal ultrasounds, equivocal saline infusion, sonograms, equivocal MRIs—be able to take a look. Let’s come up to speed like our other colleagues in other specialties that “look.” A systematic review guideline document will provide the evidence that blind D&C is fraught with problems and how often we miss disease and its inherent risk.

We need to, by itself, for most of our patients, abandon D&C because we have too many missed diagnoses. As doctors we have to be lifelong learners. There was no robot back in the day. We were not able to do laparoscopic hysterectomies, there were no MRIs. I remember in our city, there was one CT scan. We just did not have a lot of technology. The half-life of medical knowledge used to be decades—you graduated in the ‘60s, you could be a great gynecologist for the next 30 years because there was not that much going on. When I finished in the mid to late ‘80s, there was no hysteroscopy training. But I have come to see its value, the science behind it.

So what I say to doctors is, “We learn so many new things, we shouldn’t get stuck in just saying, ‘I didn’t do this when I was in training.’” And if your thought is, “Oh, in my practice, I don’t have that many cases,” you still need to be able to know who in your community can be a resource to your patients. As Maya Angelou says, “When you know better, you should do better.” And that’s where I am now—to be a lifelong learner, and just do it.

Lastly, patient influence is very important. If patients ask, “How are you going to do the procedure?” it’s a driver for change. By utilizing hysteroscopy in the evaluation of the intrauterine cavity, we have the opportunity to change the face of evaluation and treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding.●

To maximize visualization and procedure ease, schedule office hysteroscopy shortly after menstruation for reproductive-age women with regular menstrual cycles, which corresponds to timing of the thinnest endometrial lining.1 By contrast, the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle may be associated with the presence of secretory endometrium, which may mimic endometrial polyps or obscure intrauterine pathology, including FIGO type 1 and 2 submucous leiomyomas.

The following patients can have their procedures scheduled at any time, as they do not regularly cycle:

- those receiving continuous hormonal contraception

- women taking menopausal hormonal therapy

- women on progestin therapy (including those using intrauterine devices).

For patients with irregular cycles, timing is crucial as the topography of the endometrium can be variable. To increase successful visualization and diagnostic accuracy, a short course of combined hormonal contraceptives2 or progestin therapy3,4 can be considered for 10-14 days, followed by a withdrawal menses, and immediate procedure scheduling after bleeding subsides, as this will produce a thin endometrium. This approach may be especially beneficial for operative procedures such as polypectomy in order to promote complete specimen extraction.

Pharmacologic endometrial preparation also is an option and has been associated with decreased procedure time and improved patient and clinician satisfaction during operative hysteroscopy.2,3 We discourage the use of hormonal pre-treatment for diagnostic hysteroscopy alone, as this may alter endometrial histology and provide misleading results. Overall, data related to pharmacologic endometrial preparation are limited to small studies with varying treatment protocols, and an optimal regimen has yet to be determined.

References

1. The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003712.

2. Cicinelli E, Pinto V, Quattromini P, et al. Endometrial preparation with estradiol plus dienogest (Qlaira) for office hysteroscopic polypectomy: randomized pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:356-359. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2011.12.020.

3. Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Muscia V, et al. Endometrial preparation with dienogest before hysteroscopic surgery: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:661-667. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4244-1.

4. Ciebiera M, Zgliczyńska M, Zgliczyński S, et al. Oral desogestrel as endometrial preparation before operative hysteroscopy: a systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2021;86:209-217. doi:10.1159/000514584.

Linda Bradley, MD: The standard in ObGyn for many years has been our reliance on the blind dilation and curettage (D&C)—it has been the mainstay for evaluation of the endometrial cavity. We know that it has risks, but most importantly, the procedure has low sensitivity for detecting focal pathology. This basic lack of confirmation of lesions makes a diagnosis impossible and patients are challenged in getting adequate treatment, and will not, since they may not know what options they have for the treatment of intrauterine pathology.

Because it is a “blind procedure,” done without looking, we don’t know the endpoints, such as when is the procedure completed, how do we know we removed all of the lesions? Let’s look at our colleagues, like GI and colorectal physicians. If a patient presents with rectal bleeding, we would perform an exam, followed by either a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. If a patient were vomiting up blood, a gastroenterologist would perform an upper endoscopy, look with a tube to see if there is an ulcer or something else as a source of the bleeding. If a patient were bleeding from the bladder, a urologist would use a cystoscope for direct inspection.

Unfortunately for gynecologists, only about 15% to 25% of us will use hysteroscopy as a diagnostic method2—a method that has excellent sensitivity in detecting endocervical disease, intrauterine disease, and proximal tubal pathology. Compared with blind curettage, we can visualize the cavity; we can sample the cavity directly; we can determine what the patient has and determine the proper surgical procedure, medical therapy, or reassurance that a patient may be offered. We often are looking at focal lesions, lesions in the uterine cavity that could be cancer, so we can make a diagnosis. Or we may be looking at small things, like endometrial hyperplasia, endocervical or endometrial polyps, retained products of conception, or fibroids. We can look at uterine pathology as well as anatomic issues and malformations—such as bicornuate or septate uterus.

I actually say, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope” because it allows us to evaluate for many things. The beauty of the new office hysteroscopes is that they are miniaturized. Doctors now have the ability to use reusable devices that are as small as 3 millimeters. There are disposable ones that are up to 3.5 to 4 millimeters in size. Gynecologists have the options to choose from reusuable rigid or flexible hysteroscopes or completely disposable devices. So, truly, we now should not have an excuse for evaluating a woman’s anatomy, especially for bleeding. We should no longer rely, as we have for the last century or more, just on blind sampling, because we miss focal lesions.

OBG Management: When was the hysteroscope first introduced into the field?

Dr. Bradley: The technology employed in hysteroscopy has been around really since the last 150+ years, introduced by Dr. Pantaleoni. We just have not embraced its usefulness in our clinical practice for many years. Today, about 15% to 25% of gynecologists practicing in the United States are performing hysteroscopy in the office.1

OBG Management: How does using hysteroscopy contribute to better patient outcomes?

Dr. Bradley: We can get a more accurate diagnosis—fewer false-negatives and a high degree of sensitivity in detecting focal lesions. With D&C, much focal pathology can be left behind. In a 2001 study, 105 symptomatic postmenopausal women with bleeding and thickened lining of the uterus greater than 5 mm on ultrasound underwent blind D&C. They found that 80% of the women had intracavitary lesions and 90% had focal lesions. In fact, 87% of the patients with focal lesions still had residual pathology after the blind D&C.3 The D&C procedure missed 58% of polyps, 50% of endometrial hyperplasia, 60% of cases of complex atypical hyperplasia, and even 11% of endometrial cancers. So these numbers are just not very good. Direct inspection of the uterus, with uninterrupted visualization through hysteroscopy, with removal of lesions under direct visualization, should be our goal.

Blind sampling also poses greater risk for things like perforation. In addition, you not only can miss lesions by just scraping the endometrium, D&C also can leave lesions just floating around in the uterine cavity, with those lesions never retrieved. With office hysteroscopy, the physician can be more successful in treating a condition because once you see what is going on in the uterine cavity, you can say, “Okay, I can fix this with a surgical procedure. What instruments do I need? How much time is it going to take? Is this a straightforward case? Is it more complicated? Do I let an intern do the case? Is this for a more senior resident or fellow?” So I think it helps to direct the next steps for surgical management and even medical management, which also could be what we call “one-stop shopping.” For instance, for directed biopsies for removal of small polyps, for patients that can tolerate the procedure a little longer, the diagnostic hysteroscopy then becomes a management, an operative procedure, that really, for myself, can be done in the office. Removal of larger fibroids, because of fluid management and other concerns, would not be done in the office. Most patients tolerate office procedures, but it also depends on a patient’s weight, and her ability to relax during the procedure.

The ultimate goal for hysteroscopy is a minimum of diagnosis, meaning in less than 2, 3 minutes, you can look inside the uterus. Our devices are 3 millimeters in size; I tell my patients, it’s the size of “a piece of spaghetti or pasta,” and we will just take a look. If we see a polyp, okay, if your office is not equipped, because then you need a different type of equipment for removal, then take her to the operating room. The patient would be under brief anesthesia and go home an hour or 2 later. So really, for physicians, we just need to embrace the technology to make a diagnosis, just look, and then from there decide what is next.

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?...

OBG Management: What techniques do you use to minimize or eliminate patient discomfort during hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: I think first is always be patient-centric. Let patients be prepared for the procedure. We have reading materials; our nurses explain the procedure. In the office, I try to prepare the patient for success. I let her know what is going on. A friend, family member can be with her. We have a nurse that understands the procedure; she explains it well. We have a type of bed that allows the patients’ legs to rest more comfortably in the stirrups—a leg rest kind of stirrup. We use a heating pad. Some patients like to hear music. Some patients like to have aromatherapy. We are quick and efficient, and typically just talk to the patient throughout the procedure. Although some patients don’t like this explanatory, “talkative” approach—they say, “Dr. Bradley, just do the procedure. I don’t want to know you are touching the cervix. I don’t want to know that you’re prepping. Just do it.”

But I like what we called it when I was growing up: vocal-local (talk to your patient and explain as you proceed). It’s like local anesthesia. For these procedures in the office you usually do not have to use numbing medicine or a paracervical block. Look at the patient’s age, number of years in menopause, whether or not she has delivered vaginally, and what her cervix looks like. Does she have a sexually transmitted infection or pelvic inflammatory disease? Sometimes we will use misoprostol, my personal preference is oral, but there are data to suggest that vaginal can be of help.4 We suggest Motrin, Tylenol an hour or 2 before, and we always want patients to not come in on an empty stomach. There is also the option of primrose oil, a supplement, that patients buy at the drug store in the vitamin section. It’s used for cervical softening. It is taken orally.5-7

If they want, patients can watch a video—similar to watching childbirth videos when I used to deliver babies. At some point we started putting mirrors where women could see their efforts of pushing a baby out, as it might give them more willpower to push harder. Some people don’t want to look. But the majority of women will do well in this setting. I do have a small number of women that just say, “I can’t do this in the office,” and so in those cases, they can go to the operating room. But the main idea is, even in an operating room, you are not just doing a D&C. You are still going to look inside with a hysteroscope and have a great panoramic view of what is going on, and remove a lesion with an instrument while you watch. Not a process of looking with the hysteroscope, scraping with a curettage, and thinking that you are complete. Targeted removal of focal lesions under continuous visualization is the goal.

OBG Management: Can you describe the goals of the consensus document on ending blind sampling co-created by the European Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy, AAGL, and the Global Community on Hysteroscopy?

Dr. Bradley: Our goal for this year is to get a systematic review and guidelines paper written that speaks to what we have just talked about. We want to have as many articles about why blind sampling is not beneficial, with too many misses, and now we have new technology available. We want to speak to physicians to solve the conundrum of bleeding, with equivocal ultrasounds, equivocal saline infusion, sonograms, equivocal MRIs—be able to take a look. Let’s come up to speed like our other colleagues in other specialties that “look.” A systematic review guideline document will provide the evidence that blind D&C is fraught with problems and how often we miss disease and its inherent risk.

We need to, by itself, for most of our patients, abandon D&C because we have too many missed diagnoses. As doctors we have to be lifelong learners. There was no robot back in the day. We were not able to do laparoscopic hysterectomies, there were no MRIs. I remember in our city, there was one CT scan. We just did not have a lot of technology. The half-life of medical knowledge used to be decades—you graduated in the ‘60s, you could be a great gynecologist for the next 30 years because there was not that much going on. When I finished in the mid to late ‘80s, there was no hysteroscopy training. But I have come to see its value, the science behind it.

So what I say to doctors is, “We learn so many new things, we shouldn’t get stuck in just saying, ‘I didn’t do this when I was in training.’” And if your thought is, “Oh, in my practice, I don’t have that many cases,” you still need to be able to know who in your community can be a resource to your patients. As Maya Angelou says, “When you know better, you should do better.” And that’s where I am now—to be a lifelong learner, and just do it.

Lastly, patient influence is very important. If patients ask, “How are you going to do the procedure?” it’s a driver for change. By utilizing hysteroscopy in the evaluation of the intrauterine cavity, we have the opportunity to change the face of evaluation and treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding.●

To maximize visualization and procedure ease, schedule office hysteroscopy shortly after menstruation for reproductive-age women with regular menstrual cycles, which corresponds to timing of the thinnest endometrial lining.1 By contrast, the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle may be associated with the presence of secretory endometrium, which may mimic endometrial polyps or obscure intrauterine pathology, including FIGO type 1 and 2 submucous leiomyomas.

The following patients can have their procedures scheduled at any time, as they do not regularly cycle:

- those receiving continuous hormonal contraception

- women taking menopausal hormonal therapy

- women on progestin therapy (including those using intrauterine devices).

For patients with irregular cycles, timing is crucial as the topography of the endometrium can be variable. To increase successful visualization and diagnostic accuracy, a short course of combined hormonal contraceptives2 or progestin therapy3,4 can be considered for 10-14 days, followed by a withdrawal menses, and immediate procedure scheduling after bleeding subsides, as this will produce a thin endometrium. This approach may be especially beneficial for operative procedures such as polypectomy in order to promote complete specimen extraction.

Pharmacologic endometrial preparation also is an option and has been associated with decreased procedure time and improved patient and clinician satisfaction during operative hysteroscopy.2,3 We discourage the use of hormonal pre-treatment for diagnostic hysteroscopy alone, as this may alter endometrial histology and provide misleading results. Overall, data related to pharmacologic endometrial preparation are limited to small studies with varying treatment protocols, and an optimal regimen has yet to be determined.

References

1. The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003712.

2. Cicinelli E, Pinto V, Quattromini P, et al. Endometrial preparation with estradiol plus dienogest (Qlaira) for office hysteroscopic polypectomy: randomized pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19:356-359. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2011.12.020.

3. Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Muscia V, et al. Endometrial preparation with dienogest before hysteroscopic surgery: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:661-667. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4244-1.

4. Ciebiera M, Zgliczyńska M, Zgliczyński S, et al. Oral desogestrel as endometrial preparation before operative hysteroscopy: a systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2021;86:209-217. doi:10.1159/000514584.

- Orlando MS, Bradley LD. Implementation of office hysteroscopy for the evaluation and treatment of intrauterine pathology. Obstet Gynecol. August 3, 2022. doi: 10.1097/ AOG.0000000000004898.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Epstein E, Ramirez A, Skoog L, et al. Dilatation and curettage fails to detect most focal lesions in the uterine cavity in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1131-1136. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801210.x.

- The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/ AOG.0000000000003712.

- Vahdat M, Tahermanesh K, Mehdizadeh Kashi A, et al. Evening Primrose Oil effect on the ease of cervical ripening and dilatation before operative hysteroscopy. Thrita. 2015;4:7-10. doi:10.5812/thrita.29876

- Nouri B, Baghestani A, Pooransari P. Evening primrose versus misoprostol for cervical dilatation before gynecologic surgeries: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Obstet Gynecol Cancer Res. 2021;6:87-94. doi:10.30699/jogcr.6.2.87

- Verano RMA, Veloso-borromeo MG. The efficacy of evening primrose oil as a cervical ripening agent for gynecologic procedures: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. PJOG. 2015;39:24-28.

- Orlando MS, Bradley LD. Implementation of office hysteroscopy for the evaluation and treatment of intrauterine pathology. Obstet Gynecol. August 3, 2022. doi: 10.1097/ AOG.0000000000004898.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Epstein E, Ramirez A, Skoog L, et al. Dilatation and curettage fails to detect most focal lesions in the uterine cavity in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1131-1136. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801210.x.

- The use of hysteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e138-e148. doi:10.1097/ AOG.0000000000003712.

- Vahdat M, Tahermanesh K, Mehdizadeh Kashi A, et al. Evening Primrose Oil effect on the ease of cervical ripening and dilatation before operative hysteroscopy. Thrita. 2015;4:7-10. doi:10.5812/thrita.29876

- Nouri B, Baghestani A, Pooransari P. Evening primrose versus misoprostol for cervical dilatation before gynecologic surgeries: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Obstet Gynecol Cancer Res. 2021;6:87-94. doi:10.30699/jogcr.6.2.87

- Verano RMA, Veloso-borromeo MG. The efficacy of evening primrose oil as a cervical ripening agent for gynecologic procedures: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. PJOG. 2015;39:24-28.

Do scare tactics work?

I suspect that you have heard about or maybe read the recent Associated Press story reporting that four daycare workers in Hamilton, Miss., have been charged with felony child abuse for intentionally scaring the children “who didn’t clean up or act good” by wearing a Halloween mask and yelling in their faces. I can have some sympathy for those among us who choose to spend their days tending a flock of sometimes unruly and mischievous toddlers and preschoolers. But, I think one would be hard pressed to find very many adults who would condone the strategy of these misguided daycare providers. Not surprisingly, the parents of some of these children describe their children as traumatized and having disordered sleep.

The news report of this incident in Mississippi doesn’t tell us if these daycare providers had used this tactic in the past. One wonders whether they had found less dramatic verbal threats just weren’t as effective as they had hoped and so decided to go all out.

How effective is fear in changing behavior? Certainly, we have all experienced situations in which a frightening experience has caused us to avoid places, people, and activities. But, is a fear-focused strategy one that health care providers should include in their quiver as we try to mold patient behavior? As luck would have it, 2 weeks before this news story broke I encountered a global study from 84 countries that sought to answer this question (Affect Sci. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3).

Using the WHO four-point advice about COVID prevention (stay home/avoid shops/use face covering/isolate if exposed) as a model the researchers around the world reviewed the responses of 16,000 individuals. They found that there was no difference in the effectiveness of the message whether it was framed as a negative (“you have so much to lose”) or a positive (“you have so much to gain”). However, investigators observed that the negatively framed presentations generated significantly more anxiety in the respondents. The authors of the paper conclude that if there is no significant difference in the effectiveness, why would we chose a negatively framed presentation that is likely to generate anxiety that we know is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. From a purely public health perspective, it doesn’t make sense and is counterproductive.

I guess if we look back to the old carrot and stick metaphor we shouldn’t be surprised by the findings in this paper. If one’s only goal is to get a group of young preschoolers to behave by scaring the b’geezes out of them with a mask or a threat of bodily punishment, then go for it. Scare tactics will probably work just as well as offering a well-chosen reward system. However, the devil is in the side effects. It’s the same argument that I give to parents who argue that spanking works. Of course it does, but it has a narrow margin for safety and can set up ripples of negative side effects that can destroy healthy parent-child relationships.

The bottom line of this story is the sad truth that somewhere along the line someone failed to effectively train these four daycare workers. But, do we as health care providers need to rethink our training? Have we forgotten our commitment to “First do no harm?” As we craft our messaging have we thought enough about the potential side effects of our attempts at scaring the public into following our suggestions?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

I suspect that you have heard about or maybe read the recent Associated Press story reporting that four daycare workers in Hamilton, Miss., have been charged with felony child abuse for intentionally scaring the children “who didn’t clean up or act good” by wearing a Halloween mask and yelling in their faces. I can have some sympathy for those among us who choose to spend their days tending a flock of sometimes unruly and mischievous toddlers and preschoolers. But, I think one would be hard pressed to find very many adults who would condone the strategy of these misguided daycare providers. Not surprisingly, the parents of some of these children describe their children as traumatized and having disordered sleep.

The news report of this incident in Mississippi doesn’t tell us if these daycare providers had used this tactic in the past. One wonders whether they had found less dramatic verbal threats just weren’t as effective as they had hoped and so decided to go all out.

How effective is fear in changing behavior? Certainly, we have all experienced situations in which a frightening experience has caused us to avoid places, people, and activities. But, is a fear-focused strategy one that health care providers should include in their quiver as we try to mold patient behavior? As luck would have it, 2 weeks before this news story broke I encountered a global study from 84 countries that sought to answer this question (Affect Sci. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3).

Using the WHO four-point advice about COVID prevention (stay home/avoid shops/use face covering/isolate if exposed) as a model the researchers around the world reviewed the responses of 16,000 individuals. They found that there was no difference in the effectiveness of the message whether it was framed as a negative (“you have so much to lose”) or a positive (“you have so much to gain”). However, investigators observed that the negatively framed presentations generated significantly more anxiety in the respondents. The authors of the paper conclude that if there is no significant difference in the effectiveness, why would we chose a negatively framed presentation that is likely to generate anxiety that we know is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. From a purely public health perspective, it doesn’t make sense and is counterproductive.

I guess if we look back to the old carrot and stick metaphor we shouldn’t be surprised by the findings in this paper. If one’s only goal is to get a group of young preschoolers to behave by scaring the b’geezes out of them with a mask or a threat of bodily punishment, then go for it. Scare tactics will probably work just as well as offering a well-chosen reward system. However, the devil is in the side effects. It’s the same argument that I give to parents who argue that spanking works. Of course it does, but it has a narrow margin for safety and can set up ripples of negative side effects that can destroy healthy parent-child relationships.

The bottom line of this story is the sad truth that somewhere along the line someone failed to effectively train these four daycare workers. But, do we as health care providers need to rethink our training? Have we forgotten our commitment to “First do no harm?” As we craft our messaging have we thought enough about the potential side effects of our attempts at scaring the public into following our suggestions?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

I suspect that you have heard about or maybe read the recent Associated Press story reporting that four daycare workers in Hamilton, Miss., have been charged with felony child abuse for intentionally scaring the children “who didn’t clean up or act good” by wearing a Halloween mask and yelling in their faces. I can have some sympathy for those among us who choose to spend their days tending a flock of sometimes unruly and mischievous toddlers and preschoolers. But, I think one would be hard pressed to find very many adults who would condone the strategy of these misguided daycare providers. Not surprisingly, the parents of some of these children describe their children as traumatized and having disordered sleep.

The news report of this incident in Mississippi doesn’t tell us if these daycare providers had used this tactic in the past. One wonders whether they had found less dramatic verbal threats just weren’t as effective as they had hoped and so decided to go all out.

How effective is fear in changing behavior? Certainly, we have all experienced situations in which a frightening experience has caused us to avoid places, people, and activities. But, is a fear-focused strategy one that health care providers should include in their quiver as we try to mold patient behavior? As luck would have it, 2 weeks before this news story broke I encountered a global study from 84 countries that sought to answer this question (Affect Sci. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3).

Using the WHO four-point advice about COVID prevention (stay home/avoid shops/use face covering/isolate if exposed) as a model the researchers around the world reviewed the responses of 16,000 individuals. They found that there was no difference in the effectiveness of the message whether it was framed as a negative (“you have so much to lose”) or a positive (“you have so much to gain”). However, investigators observed that the negatively framed presentations generated significantly more anxiety in the respondents. The authors of the paper conclude that if there is no significant difference in the effectiveness, why would we chose a negatively framed presentation that is likely to generate anxiety that we know is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. From a purely public health perspective, it doesn’t make sense and is counterproductive.

I guess if we look back to the old carrot and stick metaphor we shouldn’t be surprised by the findings in this paper. If one’s only goal is to get a group of young preschoolers to behave by scaring the b’geezes out of them with a mask or a threat of bodily punishment, then go for it. Scare tactics will probably work just as well as offering a well-chosen reward system. However, the devil is in the side effects. It’s the same argument that I give to parents who argue that spanking works. Of course it does, but it has a narrow margin for safety and can set up ripples of negative side effects that can destroy healthy parent-child relationships.

The bottom line of this story is the sad truth that somewhere along the line someone failed to effectively train these four daycare workers. But, do we as health care providers need to rethink our training? Have we forgotten our commitment to “First do no harm?” As we craft our messaging have we thought enough about the potential side effects of our attempts at scaring the public into following our suggestions?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Past, Present, and Future of Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis Management

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or eczema, is a common inflammatory skin disease notorious for its chronic, relapsing, and often frustrating disease course. Although as many as 25% of children in the United States are affected by this condition and its impact on the quality of life of affected patients and families is profound,1-3 therapeutic advances in the pediatric population have been fairly limited until recently.

Over the last 10 years, there has been robust investigation into pediatric AD therapeutics, with many topical and systemic medications either recently approved or under clinical investigation. These developments are changing the landscape of the management of pediatric AD and raise a set of fascinating questions about how early and aggressive intervention might change the course of this disease. We discuss current limitations in the field that may be addressed with additional research.

New Topical Medications

In the last several years, there has been a rapid increase in efforts to develop new topical agents to manage AD. Until the beginning of the 21st century, the dermatologist’s arsenal was limited to topical corticosteroids (TCs). In the early 2000s, attention shifted to topical calcineurin inhibitors as nonsteroidal alternatives when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for AD. In 2016, crisaborole (a phosphodiesterase-4 [PDE4] inhibitor) was approved by the FDA for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 2 years and older, marking a new age of development for topical AD therapies. In 2021, the FDA approved ruxolitinib (a topical Janus kinase [JAK] 1/2 inhibitor) for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 12 years and older.

Roflumilast (ARQ-151) and difamilast (OPA-15406)(members of the PDE4 inhibitor class) are undergoing investigation for pediatric AD. A phase 3 clinical trial for roflumilast for AD is underway (ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT04845620); it is already approved for psoriasis in patients 12 years and older. A phase 3 trial of difamilast (NCT03911401) was recently completed, with results supporting the drug’s safety and efficacy in AD management.4 Efforts to synthesize new better-targeted PDE4 inhibitors are ongoing.5

Tapinarof (a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent) is approved for psoriasis in adults, and a phase 3 trial for management of pediatric AD is underway (NCT05032859) after phase 2 trials revealed promising results.6

Lastly, the microbiome is a target for AD topical therapies. A recently completed phase 1 trial of bacteriotherapy with Staphylococcus hominis A9 transplant lotion showed promising results (NCT03151148).7 Although this bacteriotherapy technique is early in development and has been studied only in adult patients, results are exciting because they represent a gateway to a largely unexplored realm of potential future therapies.

Standard of Care—How will these new topical therapies impact our standard of care for pediatric AD patients? Topical corticosteroids are still a pillar of topical AD therapy, but the potential for nonsteroidal topical agents as alternatives and used in combination therapeutic regimens has expanded exponentially. It is uncertain how we might individualize regimens tailored to patient-specific factors because the standard approach has been to test drugs as monotherapy, with vehicle comparisons or with reference medications in Europe.

Newer topical nonsteroidal agents may offer several opportunities. First, they may help avoid local and systemic adverse effects that often limit the use of current standard therapy.8 This capability may prove essential in bridging TC treatments and serving as long-term maintenance therapies to decrease the frequency of eczema flares. Second, they can alleviate the need for different medication strengths for different body regions, thereby allowing for simplification of regimens and potentially increased adherence and decreased disease burden—a boon to affected patients and caregivers.

Although the efficacy and long-term safety profile of these new drugs require further study, it does not seem unreasonable to look forward to achieving levels of optimization and individualization with topical regimens for AD in the near future that makes flares in patients with mild to moderate AD a phenomenon of the past.

Advances in Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapeutics in pediatric AD also recently entered an exciting era of development. Traditional systemic agents, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, have existed for decades but have not been widely utilized for moderate to severe AD in the United States, especially in the pediatric population, likely because these drugs lacked FDA approval and they can cause a range of adverse effects, including notable immunosuppression.9

Introduction and approval of dupilumab in 2017 by the FDA was revolutionary in this field. As a monoclonal antibody targeted against IL-4 and IL-13, dupilumab has consistently demonstrated strong long-term efficacy for pediatric AD and has an acceptable safety profile in children and adolescents.10-14 Expansion of the label to include children as young as 6 months with moderate to severe AD seems an important milestone in pediatric AD care.

Since the approval of dupilumab for adolescents and children aged 6 to 12 years, global experience has supported expanded use of systemic agents for patients who have an inadequate response to TCs and previously approved nonsteroidal topical agents. How expansive the use of systemics will be in younger children depends on how their long-term use impacts the disease course, whether therapy is disease modifying, and whether early use can curb the development of comorbidities.

Investigations into targeted systemic therapeutics for eczematous dermatitis are not limited to dupilumab. In a study of adolescents as young as 12 years, tralokinumab (an IL-13 pathway inhibitor) demonstrated an Eczema Area Severity Index-75 of 27.8% to 28.6% and a mean decrease in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index of 27.5 to 29.1, with minimal adverse effects.15 Lebrikizumab, another biologic IL-13 inhibitor with strong published safety and efficacy data in adults, has completed short- and longer-term studies in adolescents (NCT04178967 and NCT04146363).16 The drug received FDA Fast Track designation for moderate to severe AD in patients 12 years and older after showing positive data.17

This push to targeted therapy stretches beyond monoclonal antibodies. In the last few years, oral JAK inhibitors have emerged as a new class of systemic therapy for eczematous dermatitis. Upadacitinib, a JAK1 selective inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in 2022 for patients 12 years and older with AD and has data that supports its efficacy in adolescents and adults.18 Other JAK inhibitors including the selective JAK1 inhibitor abrocitinib and the combined JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib are being studied for pediatric AD (NCT04564755, NCT03422822, and NCT03952559), with most evidence to date supporting their safety and efficacy, at least over the short-term.19

The study of these and other advanced systemic therapies for eczematous dermatitis is transforming the toolbox for pediatric AD care. Although long-term data are lacking for some of these medications, it is possible that newer agents may decrease reliance on older immunosuppressants, such as systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. Unanswered questions include: How and which systemic medications may alter the course of the disease? What is the disease modification for AD? What is the impact on comorbidities over time?

What’s Missing?

The field of pediatric AD has experienced exciting new developments with the emergence of targeted therapeutics, but those new agents require more long-term study, though we already have longer-term data on crisaborole and dupilumab.10-14,20 Studies of the long-term use of these new treatments on comorbidities of pediatric AD—mental health outcomes, cardiovascular disease, effects on the family, and other allergic conditions—are needed.21 Furthermore, clinical guidelines that address indications, timing of use, tapering, and discontinuation of new treatments depend on long-term experience and data collection.

Therefore, it is prudent that investigators, companies, payers, patients, and families support phase 4, long-term extension, and registry studies, which will expand our knowledge of AD medications and their impact on the disease over time.

Final Thoughts

Medications to treat AD are reaching a new level of advancement—from topical agents that target novel pathways to revolutionary biologics and systemic medications. Although there are knowledge gaps on these new therapeutics, the standard of care is already rapidly changing as the expectations of clinicians, patients, and families advance with each addition to the provider’s toolbox.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010

- Kiebert G, Sorensen SV, Revicki D, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with a decrement in health-related quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:151-158. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01436.x

- Al Shobaili HA. The impact of childhood atopic dermatitis on the patients’ family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:618-623. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01215.x

- Saeki H, Baba N, Ito K, et al. Difamilast, a selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, ointment in paediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a phase III randomized double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial [published online November 1, 2021]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:40-49. doi:10.1111/bjd.20655

- Chu Z, Xu Q, Zhu Q, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel benzoxaborole derivatives as potent PDE4 inhibitors for topical treatment of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;213:113171. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113171

- Paller AS, Stein Gold L, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and patient-reported outcomes from a phase 2b, randomized clinical trial of tapinarof cream for the treatment of adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:632-638. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.135

- Nakatsuji T, Hata TR, Tong Y, et al. Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:700-709. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: part 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC-H, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336

- Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, Paller AS, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopicdermatitis: results through week 52 from a phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365-383. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2

- Cork MJ, D, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dupilumab provides favourable long-term safety and efficacy in children aged ≥ 6 to < 12 years with uncontrolled severe atopic dermatitis: results from an open-label phase IIa study and subsequent phase III open-label extension study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:857-870. doi:10.1111/bjd.19460

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab demonstrates rapid and consistent improvement in extent and signs of atopic dermatitis across all anatomical regions in pediatric patients 6 years of age and older. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1643-1656. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00568-y

- Paller A, Blauvelt A, Soong W, et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results of the phase 3 ECZTRA 6 trial. SKIN. 2022;6:S29. doi:10.25251/skin.6.supp.s29

- Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:411-420. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0079

- Lebrikizumab dosed every four weeks maintained durable skin clearance in Lilly’s phase 3 monotherapy atopic dermatitis trials [news release]. Eli Lilly and Company; September 8, 2022. Accessed October 19, 2022. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lebrikizumab-dosed-every-four-weeks-maintained-durable-skin

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2

- Chovatiya R, Paller AS. JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:927-940. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.009

- Geng B, Hebert AA, Takiya L, et al. Efficacy and safety trends with continuous, long-term crisaborole use in patients aged ≥ 2 years with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1667-1678. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00584-y

- Appiah MM, Haft MA, Kleinman E, et al. Atopic dermatitis: review of comorbidities and therapeutics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:142-149. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2022.05.015

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or eczema, is a common inflammatory skin disease notorious for its chronic, relapsing, and often frustrating disease course. Although as many as 25% of children in the United States are affected by this condition and its impact on the quality of life of affected patients and families is profound,1-3 therapeutic advances in the pediatric population have been fairly limited until recently.

Over the last 10 years, there has been robust investigation into pediatric AD therapeutics, with many topical and systemic medications either recently approved or under clinical investigation. These developments are changing the landscape of the management of pediatric AD and raise a set of fascinating questions about how early and aggressive intervention might change the course of this disease. We discuss current limitations in the field that may be addressed with additional research.

New Topical Medications

In the last several years, there has been a rapid increase in efforts to develop new topical agents to manage AD. Until the beginning of the 21st century, the dermatologist’s arsenal was limited to topical corticosteroids (TCs). In the early 2000s, attention shifted to topical calcineurin inhibitors as nonsteroidal alternatives when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for AD. In 2016, crisaborole (a phosphodiesterase-4 [PDE4] inhibitor) was approved by the FDA for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 2 years and older, marking a new age of development for topical AD therapies. In 2021, the FDA approved ruxolitinib (a topical Janus kinase [JAK] 1/2 inhibitor) for use in mild to moderate AD in patients 12 years and older.

Roflumilast (ARQ-151) and difamilast (OPA-15406)(members of the PDE4 inhibitor class) are undergoing investigation for pediatric AD. A phase 3 clinical trial for roflumilast for AD is underway (ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT04845620); it is already approved for psoriasis in patients 12 years and older. A phase 3 trial of difamilast (NCT03911401) was recently completed, with results supporting the drug’s safety and efficacy in AD management.4 Efforts to synthesize new better-targeted PDE4 inhibitors are ongoing.5

Tapinarof (a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent) is approved for psoriasis in adults, and a phase 3 trial for management of pediatric AD is underway (NCT05032859) after phase 2 trials revealed promising results.6

Lastly, the microbiome is a target for AD topical therapies. A recently completed phase 1 trial of bacteriotherapy with Staphylococcus hominis A9 transplant lotion showed promising results (NCT03151148).7 Although this bacteriotherapy technique is early in development and has been studied only in adult patients, results are exciting because they represent a gateway to a largely unexplored realm of potential future therapies.

Standard of Care—How will these new topical therapies impact our standard of care for pediatric AD patients? Topical corticosteroids are still a pillar of topical AD therapy, but the potential for nonsteroidal topical agents as alternatives and used in combination therapeutic regimens has expanded exponentially. It is uncertain how we might individualize regimens tailored to patient-specific factors because the standard approach has been to test drugs as monotherapy, with vehicle comparisons or with reference medications in Europe.

Newer topical nonsteroidal agents may offer several opportunities. First, they may help avoid local and systemic adverse effects that often limit the use of current standard therapy.8 This capability may prove essential in bridging TC treatments and serving as long-term maintenance therapies to decrease the frequency of eczema flares. Second, they can alleviate the need for different medication strengths for different body regions, thereby allowing for simplification of regimens and potentially increased adherence and decreased disease burden—a boon to affected patients and caregivers.

Although the efficacy and long-term safety profile of these new drugs require further study, it does not seem unreasonable to look forward to achieving levels of optimization and individualization with topical regimens for AD in the near future that makes flares in patients with mild to moderate AD a phenomenon of the past.

Advances in Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapeutics in pediatric AD also recently entered an exciting era of development. Traditional systemic agents, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, have existed for decades but have not been widely utilized for moderate to severe AD in the United States, especially in the pediatric population, likely because these drugs lacked FDA approval and they can cause a range of adverse effects, including notable immunosuppression.9

Introduction and approval of dupilumab in 2017 by the FDA was revolutionary in this field. As a monoclonal antibody targeted against IL-4 and IL-13, dupilumab has consistently demonstrated strong long-term efficacy for pediatric AD and has an acceptable safety profile in children and adolescents.10-14 Expansion of the label to include children as young as 6 months with moderate to severe AD seems an important milestone in pediatric AD care.

Since the approval of dupilumab for adolescents and children aged 6 to 12 years, global experience has supported expanded use of systemic agents for patients who have an inadequate response to TCs and previously approved nonsteroidal topical agents. How expansive the use of systemics will be in younger children depends on how their long-term use impacts the disease course, whether therapy is disease modifying, and whether early use can curb the development of comorbidities.

Investigations into targeted systemic therapeutics for eczematous dermatitis are not limited to dupilumab. In a study of adolescents as young as 12 years, tralokinumab (an IL-13 pathway inhibitor) demonstrated an Eczema Area Severity Index-75 of 27.8% to 28.6% and a mean decrease in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index of 27.5 to 29.1, with minimal adverse effects.15 Lebrikizumab, another biologic IL-13 inhibitor with strong published safety and efficacy data in adults, has completed short- and longer-term studies in adolescents (NCT04178967 and NCT04146363).16 The drug received FDA Fast Track designation for moderate to severe AD in patients 12 years and older after showing positive data.17

This push to targeted therapy stretches beyond monoclonal antibodies. In the last few years, oral JAK inhibitors have emerged as a new class of systemic therapy for eczematous dermatitis. Upadacitinib, a JAK1 selective inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in 2022 for patients 12 years and older with AD and has data that supports its efficacy in adolescents and adults.18 Other JAK inhibitors including the selective JAK1 inhibitor abrocitinib and the combined JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib are being studied for pediatric AD (NCT04564755, NCT03422822, and NCT03952559), with most evidence to date supporting their safety and efficacy, at least over the short-term.19