User login

Love them or hate them, masks in schools work

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The body of evidence for Paxlovid therapy

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Which exercise is best for bone health?

An 18-year-old woman with Crohn’s disease (diagnosed 3 years ago) came to my office for advice regarding management of osteoporosis. Her bone density was low for her age, and she had three low-impact fractures of her long bones in the preceding 4 years.

Loss of weight after the onset of Crohn’s disease, subsequent loss of periods, inflammation associated with her underlying diagnosis, and early treatment with glucocorticoids (known to have deleterious effects on bone) were believed to have caused osteoporosis in this young woman.

A few months previously, she was switched to a medication that doesn’t impair bone health and glucocorticoids were discontinued; her weight began to improve, and her Crohn’s disease was now in remission. Her menses had resumed about 3 months before her visit to my clinic after a prolonged period without periods. She was on calcium and vitamin D supplements, with normal levels of vitamin D.

Many factors determine bone health including (but not limited to) genetics, nutritional status, exercise activity (with mechanical loading of bones), macro- and micronutrient intake, hormonal status, chronic inflammation and other disease states, and medication use.

Exercise certainly has beneficial effects on bone. Bone-loading activities increase bone formation through the activation of certain cells in bone called osteocytes, which serve as mechanosensors and sense bone loading. Osteocytes make a hormone called sclerostin, which typically inhibits bone formation. When osteocytes sense bone-loading activities, sclerostin secretion reduces, allowing for increased bone formation.

Consistent with this, investigators in Canada have demonstrated greater increases in bone density and strength in schoolchildren who engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity, particularly bone-loading exercise, during the school day, compared with those who don’t (J Bone Miner Res. 2007 Mar;22[3]:434-46; J Bone Miner Res. 2017 Jul;32[7]:1525-36). In females, normal levels of estrogen seem necessary for osteocytes to bring about these effects after bone-loading activities. This is probably one of several reasons why athletes who lose their periods (indicative of low estrogen levels) and develop low bone density with an increased risk for fracture even when they are still at a normal weight (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jun 1;103[6]:2392-402; Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 Aug;47[8]:1577-86).

One concern around prescribing bone-loading activity or exercise to persons with osteoporosis is whether it would increase the risk for fracture from the impact on fragile bone. The extent of bone loading safe for fragile bone can be difficult to determine. Furthermore, excessive exercise may worsen bone health by causing weight loss or loss of periods in women. Very careful monitoring may be necessary to ensure that energy balance is maintained. Therefore, the nature and volume of exercise should be discussed with one’s doctor or physical therapist as well as a dietitian (if the patient is seeing one).

In patients with osteoporosis, high-impact activities such as jumping; repetitive impact activities such as running or jogging; and bending and twisting activities such as touching one’s toes, golf, tennis, and bowling aren’t recommended because they increase the risk for fracture. Even yoga poses should be discussed, because some may increase the risk for compression fractures of the vertebrae in the spine.

Strength and resistance training are generally believed to be good for bones. Strength training involves activities that build muscle strength and mass. Resistance training builds muscle strength, mass, and endurance by making muscles work against some form of resistance. Such activities include weight training with free weights or weight machines, use of resistance bands, and use of one’s own body to strengthen major muscle groups (such as through push-ups, squats, lunges, and gluteus maximus extension).

Some amount of weight-bearing aerobic training is also recommended, including walking, low-impact aerobics, the elliptical, and stair-climbing. Non–weight-bearing activities, such as swimming and cycling, typically don’t contribute to improving bone density.

In older individuals with osteoporosis, agility exercises are particularly useful to reduce the fall risk (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 May;52[5]:657-65; CMAJ. 2002 Oct 29;167[9]:997-1004). These can be structured to improve hand-eye coordination, foot-eye coordination, static and dynamic balance, and reaction time. Agility exercises with resistance training help improve bone density in older women.

An optimal exercise regimen includes a combination of strength and resistance training; weight-bearing aerobic training; and exercises that build flexibility, stability, and balance. A doctor, physical therapist, or trainer with expertise in the right combination of exercises should be consulted to ensure optimal effects on bone and general health.

In those at risk for overexercising to the point that they start to lose weight or lose their periods, and certainly in all women with disordered eating patterns, a dietitian should be part of the decision team to ensure that energy balance is maintained. In this group, particularly in very-low-weight women with eating disorders, exercise activity is often limited until they reach a healthier weight, and ideally after their menses resume.

For my patient with Crohn’s disease, I recommended that she see a physical therapist and a dietitian for guidance about a graded increase in exercise activity and an exercise regimen that would work best for her. I assess her bone density annually using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Her bone density has gradually improved with the combination of weight gain, resumption of menses, medications for Crohn’s disease that do not affect bone deleteriously, remission of Crohn’s disease, and her exercise regimen.

Dr. Misra is chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology at Mass General Hospital for Children and professor in the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. She reported conflicts of interest with AbbVie, Sanofi, and Ipsen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An 18-year-old woman with Crohn’s disease (diagnosed 3 years ago) came to my office for advice regarding management of osteoporosis. Her bone density was low for her age, and she had three low-impact fractures of her long bones in the preceding 4 years.

Loss of weight after the onset of Crohn’s disease, subsequent loss of periods, inflammation associated with her underlying diagnosis, and early treatment with glucocorticoids (known to have deleterious effects on bone) were believed to have caused osteoporosis in this young woman.

A few months previously, she was switched to a medication that doesn’t impair bone health and glucocorticoids were discontinued; her weight began to improve, and her Crohn’s disease was now in remission. Her menses had resumed about 3 months before her visit to my clinic after a prolonged period without periods. She was on calcium and vitamin D supplements, with normal levels of vitamin D.

Many factors determine bone health including (but not limited to) genetics, nutritional status, exercise activity (with mechanical loading of bones), macro- and micronutrient intake, hormonal status, chronic inflammation and other disease states, and medication use.

Exercise certainly has beneficial effects on bone. Bone-loading activities increase bone formation through the activation of certain cells in bone called osteocytes, which serve as mechanosensors and sense bone loading. Osteocytes make a hormone called sclerostin, which typically inhibits bone formation. When osteocytes sense bone-loading activities, sclerostin secretion reduces, allowing for increased bone formation.

Consistent with this, investigators in Canada have demonstrated greater increases in bone density and strength in schoolchildren who engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity, particularly bone-loading exercise, during the school day, compared with those who don’t (J Bone Miner Res. 2007 Mar;22[3]:434-46; J Bone Miner Res. 2017 Jul;32[7]:1525-36). In females, normal levels of estrogen seem necessary for osteocytes to bring about these effects after bone-loading activities. This is probably one of several reasons why athletes who lose their periods (indicative of low estrogen levels) and develop low bone density with an increased risk for fracture even when they are still at a normal weight (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jun 1;103[6]:2392-402; Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 Aug;47[8]:1577-86).

One concern around prescribing bone-loading activity or exercise to persons with osteoporosis is whether it would increase the risk for fracture from the impact on fragile bone. The extent of bone loading safe for fragile bone can be difficult to determine. Furthermore, excessive exercise may worsen bone health by causing weight loss or loss of periods in women. Very careful monitoring may be necessary to ensure that energy balance is maintained. Therefore, the nature and volume of exercise should be discussed with one’s doctor or physical therapist as well as a dietitian (if the patient is seeing one).

In patients with osteoporosis, high-impact activities such as jumping; repetitive impact activities such as running or jogging; and bending and twisting activities such as touching one’s toes, golf, tennis, and bowling aren’t recommended because they increase the risk for fracture. Even yoga poses should be discussed, because some may increase the risk for compression fractures of the vertebrae in the spine.

Strength and resistance training are generally believed to be good for bones. Strength training involves activities that build muscle strength and mass. Resistance training builds muscle strength, mass, and endurance by making muscles work against some form of resistance. Such activities include weight training with free weights or weight machines, use of resistance bands, and use of one’s own body to strengthen major muscle groups (such as through push-ups, squats, lunges, and gluteus maximus extension).

Some amount of weight-bearing aerobic training is also recommended, including walking, low-impact aerobics, the elliptical, and stair-climbing. Non–weight-bearing activities, such as swimming and cycling, typically don’t contribute to improving bone density.

In older individuals with osteoporosis, agility exercises are particularly useful to reduce the fall risk (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 May;52[5]:657-65; CMAJ. 2002 Oct 29;167[9]:997-1004). These can be structured to improve hand-eye coordination, foot-eye coordination, static and dynamic balance, and reaction time. Agility exercises with resistance training help improve bone density in older women.

An optimal exercise regimen includes a combination of strength and resistance training; weight-bearing aerobic training; and exercises that build flexibility, stability, and balance. A doctor, physical therapist, or trainer with expertise in the right combination of exercises should be consulted to ensure optimal effects on bone and general health.

In those at risk for overexercising to the point that they start to lose weight or lose their periods, and certainly in all women with disordered eating patterns, a dietitian should be part of the decision team to ensure that energy balance is maintained. In this group, particularly in very-low-weight women with eating disorders, exercise activity is often limited until they reach a healthier weight, and ideally after their menses resume.

For my patient with Crohn’s disease, I recommended that she see a physical therapist and a dietitian for guidance about a graded increase in exercise activity and an exercise regimen that would work best for her. I assess her bone density annually using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Her bone density has gradually improved with the combination of weight gain, resumption of menses, medications for Crohn’s disease that do not affect bone deleteriously, remission of Crohn’s disease, and her exercise regimen.

Dr. Misra is chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology at Mass General Hospital for Children and professor in the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. She reported conflicts of interest with AbbVie, Sanofi, and Ipsen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An 18-year-old woman with Crohn’s disease (diagnosed 3 years ago) came to my office for advice regarding management of osteoporosis. Her bone density was low for her age, and she had three low-impact fractures of her long bones in the preceding 4 years.

Loss of weight after the onset of Crohn’s disease, subsequent loss of periods, inflammation associated with her underlying diagnosis, and early treatment with glucocorticoids (known to have deleterious effects on bone) were believed to have caused osteoporosis in this young woman.

A few months previously, she was switched to a medication that doesn’t impair bone health and glucocorticoids were discontinued; her weight began to improve, and her Crohn’s disease was now in remission. Her menses had resumed about 3 months before her visit to my clinic after a prolonged period without periods. She was on calcium and vitamin D supplements, with normal levels of vitamin D.

Many factors determine bone health including (but not limited to) genetics, nutritional status, exercise activity (with mechanical loading of bones), macro- and micronutrient intake, hormonal status, chronic inflammation and other disease states, and medication use.

Exercise certainly has beneficial effects on bone. Bone-loading activities increase bone formation through the activation of certain cells in bone called osteocytes, which serve as mechanosensors and sense bone loading. Osteocytes make a hormone called sclerostin, which typically inhibits bone formation. When osteocytes sense bone-loading activities, sclerostin secretion reduces, allowing for increased bone formation.

Consistent with this, investigators in Canada have demonstrated greater increases in bone density and strength in schoolchildren who engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity, particularly bone-loading exercise, during the school day, compared with those who don’t (J Bone Miner Res. 2007 Mar;22[3]:434-46; J Bone Miner Res. 2017 Jul;32[7]:1525-36). In females, normal levels of estrogen seem necessary for osteocytes to bring about these effects after bone-loading activities. This is probably one of several reasons why athletes who lose their periods (indicative of low estrogen levels) and develop low bone density with an increased risk for fracture even when they are still at a normal weight (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jun 1;103[6]:2392-402; Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 Aug;47[8]:1577-86).

One concern around prescribing bone-loading activity or exercise to persons with osteoporosis is whether it would increase the risk for fracture from the impact on fragile bone. The extent of bone loading safe for fragile bone can be difficult to determine. Furthermore, excessive exercise may worsen bone health by causing weight loss or loss of periods in women. Very careful monitoring may be necessary to ensure that energy balance is maintained. Therefore, the nature and volume of exercise should be discussed with one’s doctor or physical therapist as well as a dietitian (if the patient is seeing one).

In patients with osteoporosis, high-impact activities such as jumping; repetitive impact activities such as running or jogging; and bending and twisting activities such as touching one’s toes, golf, tennis, and bowling aren’t recommended because they increase the risk for fracture. Even yoga poses should be discussed, because some may increase the risk for compression fractures of the vertebrae in the spine.

Strength and resistance training are generally believed to be good for bones. Strength training involves activities that build muscle strength and mass. Resistance training builds muscle strength, mass, and endurance by making muscles work against some form of resistance. Such activities include weight training with free weights or weight machines, use of resistance bands, and use of one’s own body to strengthen major muscle groups (such as through push-ups, squats, lunges, and gluteus maximus extension).

Some amount of weight-bearing aerobic training is also recommended, including walking, low-impact aerobics, the elliptical, and stair-climbing. Non–weight-bearing activities, such as swimming and cycling, typically don’t contribute to improving bone density.

In older individuals with osteoporosis, agility exercises are particularly useful to reduce the fall risk (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 May;52[5]:657-65; CMAJ. 2002 Oct 29;167[9]:997-1004). These can be structured to improve hand-eye coordination, foot-eye coordination, static and dynamic balance, and reaction time. Agility exercises with resistance training help improve bone density in older women.

An optimal exercise regimen includes a combination of strength and resistance training; weight-bearing aerobic training; and exercises that build flexibility, stability, and balance. A doctor, physical therapist, or trainer with expertise in the right combination of exercises should be consulted to ensure optimal effects on bone and general health.

In those at risk for overexercising to the point that they start to lose weight or lose their periods, and certainly in all women with disordered eating patterns, a dietitian should be part of the decision team to ensure that energy balance is maintained. In this group, particularly in very-low-weight women with eating disorders, exercise activity is often limited until they reach a healthier weight, and ideally after their menses resume.

For my patient with Crohn’s disease, I recommended that she see a physical therapist and a dietitian for guidance about a graded increase in exercise activity and an exercise regimen that would work best for her. I assess her bone density annually using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Her bone density has gradually improved with the combination of weight gain, resumption of menses, medications for Crohn’s disease that do not affect bone deleteriously, remission of Crohn’s disease, and her exercise regimen.

Dr. Misra is chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology at Mass General Hospital for Children and professor in the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. She reported conflicts of interest with AbbVie, Sanofi, and Ipsen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new ultrabrief screening scale for pediatric OCD

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 1-2% of the population. The disorder is characterized by recurrent intrusive unwanted thoughts (obsessions) that cause significant distress and anxiety, and behavioral or mental rituals (compulsions) that are performed to reduce distress stemming from obsessions. OCD may onset at any time in life, but most commonly begins in childhood or in early adulthood.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention is an empirically based and highly effective treatment for OCD. However, most youth with OCD do not receive any treatment, which is related to a shortage of mental health care providers with expertise in assessment and treatment of the disorder, and misdiagnosis of the disorder is all too prevalent.

Aside from the subjective emotional toll associated with OCD, individuals living with this disorder frequently experience interpersonal, academic, and vocational impairments. Nevertheless, OCD is often overlooked or misdiagnosed. This may be more pronounced in youth with OCD, particularly in primary health care settings and large nonspecialized medical institutions. In fact, research indicates that pediatric OCD is often underrecognized even among mental health professionals. This situation is not new, and in fact the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom stated that there is an urgent need to develop brief reliable screeners for OCD nearly 20 years ago.

Although there were several attempts to develop brief screening scales for adults and youth with OCD, none of them were found to be suitable for use as rapid screening tools in nonspecialized settings. One of the primary reasons is that OCD is associated with different “themes” or dimensions. For example, a child with OCD may engage in cleaning rituals because the context (or dimension) of their obsessions is contamination concerns. Another child with OCD, who may suffer from similar overall symptom severity, may primarily engage in checking rituals which are related with obsessions associated with fear of being responsible for harm. Therefore, one child with OCD may score very high on items assessing one dimension (e.g., contamination concerns), but very low on another dimension (e.g., harm obsessions).

This results in a known challenge in the assessment and psychometrics of self-report (as opposed to clinician administered) measures of OCD. Secondly, development of such measures requires very large carefully screened samples of individuals with OCD, with other disorders, and those without a known psychological disorder – which may be more challenging than requiring adult participants.

To accomplish this, we harmonized data from several sites that included three samples of carefully screened youths with OCD, with other disorders, and without known disorders who completed multiple self-report questionnaires, including the 21-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV).

Utilizing psychometric analyses including factor analyses, invariance analyses, and item response theory methodologies, we were able to develop an ultrabrief measure extracted from the OCI-CV: the 5-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV-5). This very brief self-report measure was found to have very good psychometric properties including a sensitive and specific clinical cutoff score. Youth who score at or above the cutoff score are nearly 21 times more likely to meet criteria for OCD.

This measure corresponds to a need to rapidly screen for OCD in children in nonspecialized settings, including community mental health clinics, primary care settings, and pediatric treatment facilities. However, it is important to note it is not a diagnostic measure. The measure is intended to identify youth who should be referred to a mental health care professional to conduct a diagnostic interview.

Dr. Abramovitch is a clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist based in Austin, Tex., and an associate professor at Texas State University. Dr. Abramowitz is professor and director of clinical training in the Anxiety and Stress Lab at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. McKay is professor of psychology at Fordham University, Bronx, N.Y.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 1-2% of the population. The disorder is characterized by recurrent intrusive unwanted thoughts (obsessions) that cause significant distress and anxiety, and behavioral or mental rituals (compulsions) that are performed to reduce distress stemming from obsessions. OCD may onset at any time in life, but most commonly begins in childhood or in early adulthood.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention is an empirically based and highly effective treatment for OCD. However, most youth with OCD do not receive any treatment, which is related to a shortage of mental health care providers with expertise in assessment and treatment of the disorder, and misdiagnosis of the disorder is all too prevalent.

Aside from the subjective emotional toll associated with OCD, individuals living with this disorder frequently experience interpersonal, academic, and vocational impairments. Nevertheless, OCD is often overlooked or misdiagnosed. This may be more pronounced in youth with OCD, particularly in primary health care settings and large nonspecialized medical institutions. In fact, research indicates that pediatric OCD is often underrecognized even among mental health professionals. This situation is not new, and in fact the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom stated that there is an urgent need to develop brief reliable screeners for OCD nearly 20 years ago.

Although there were several attempts to develop brief screening scales for adults and youth with OCD, none of them were found to be suitable for use as rapid screening tools in nonspecialized settings. One of the primary reasons is that OCD is associated with different “themes” or dimensions. For example, a child with OCD may engage in cleaning rituals because the context (or dimension) of their obsessions is contamination concerns. Another child with OCD, who may suffer from similar overall symptom severity, may primarily engage in checking rituals which are related with obsessions associated with fear of being responsible for harm. Therefore, one child with OCD may score very high on items assessing one dimension (e.g., contamination concerns), but very low on another dimension (e.g., harm obsessions).

This results in a known challenge in the assessment and psychometrics of self-report (as opposed to clinician administered) measures of OCD. Secondly, development of such measures requires very large carefully screened samples of individuals with OCD, with other disorders, and those without a known psychological disorder – which may be more challenging than requiring adult participants.

To accomplish this, we harmonized data from several sites that included three samples of carefully screened youths with OCD, with other disorders, and without known disorders who completed multiple self-report questionnaires, including the 21-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV).

Utilizing psychometric analyses including factor analyses, invariance analyses, and item response theory methodologies, we were able to develop an ultrabrief measure extracted from the OCI-CV: the 5-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV-5). This very brief self-report measure was found to have very good psychometric properties including a sensitive and specific clinical cutoff score. Youth who score at or above the cutoff score are nearly 21 times more likely to meet criteria for OCD.

This measure corresponds to a need to rapidly screen for OCD in children in nonspecialized settings, including community mental health clinics, primary care settings, and pediatric treatment facilities. However, it is important to note it is not a diagnostic measure. The measure is intended to identify youth who should be referred to a mental health care professional to conduct a diagnostic interview.

Dr. Abramovitch is a clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist based in Austin, Tex., and an associate professor at Texas State University. Dr. Abramowitz is professor and director of clinical training in the Anxiety and Stress Lab at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. McKay is professor of psychology at Fordham University, Bronx, N.Y.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 1-2% of the population. The disorder is characterized by recurrent intrusive unwanted thoughts (obsessions) that cause significant distress and anxiety, and behavioral or mental rituals (compulsions) that are performed to reduce distress stemming from obsessions. OCD may onset at any time in life, but most commonly begins in childhood or in early adulthood.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention is an empirically based and highly effective treatment for OCD. However, most youth with OCD do not receive any treatment, which is related to a shortage of mental health care providers with expertise in assessment and treatment of the disorder, and misdiagnosis of the disorder is all too prevalent.

Aside from the subjective emotional toll associated with OCD, individuals living with this disorder frequently experience interpersonal, academic, and vocational impairments. Nevertheless, OCD is often overlooked or misdiagnosed. This may be more pronounced in youth with OCD, particularly in primary health care settings and large nonspecialized medical institutions. In fact, research indicates that pediatric OCD is often underrecognized even among mental health professionals. This situation is not new, and in fact the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom stated that there is an urgent need to develop brief reliable screeners for OCD nearly 20 years ago.

Although there were several attempts to develop brief screening scales for adults and youth with OCD, none of them were found to be suitable for use as rapid screening tools in nonspecialized settings. One of the primary reasons is that OCD is associated with different “themes” or dimensions. For example, a child with OCD may engage in cleaning rituals because the context (or dimension) of their obsessions is contamination concerns. Another child with OCD, who may suffer from similar overall symptom severity, may primarily engage in checking rituals which are related with obsessions associated with fear of being responsible for harm. Therefore, one child with OCD may score very high on items assessing one dimension (e.g., contamination concerns), but very low on another dimension (e.g., harm obsessions).

This results in a known challenge in the assessment and psychometrics of self-report (as opposed to clinician administered) measures of OCD. Secondly, development of such measures requires very large carefully screened samples of individuals with OCD, with other disorders, and those without a known psychological disorder – which may be more challenging than requiring adult participants.

To accomplish this, we harmonized data from several sites that included three samples of carefully screened youths with OCD, with other disorders, and without known disorders who completed multiple self-report questionnaires, including the 21-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV).

Utilizing psychometric analyses including factor analyses, invariance analyses, and item response theory methodologies, we were able to develop an ultrabrief measure extracted from the OCI-CV: the 5-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV-5). This very brief self-report measure was found to have very good psychometric properties including a sensitive and specific clinical cutoff score. Youth who score at or above the cutoff score are nearly 21 times more likely to meet criteria for OCD.

This measure corresponds to a need to rapidly screen for OCD in children in nonspecialized settings, including community mental health clinics, primary care settings, and pediatric treatment facilities. However, it is important to note it is not a diagnostic measure. The measure is intended to identify youth who should be referred to a mental health care professional to conduct a diagnostic interview.

Dr. Abramovitch is a clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist based in Austin, Tex., and an associate professor at Texas State University. Dr. Abramowitz is professor and director of clinical training in the Anxiety and Stress Lab at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. McKay is professor of psychology at Fordham University, Bronx, N.Y.

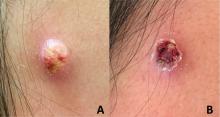

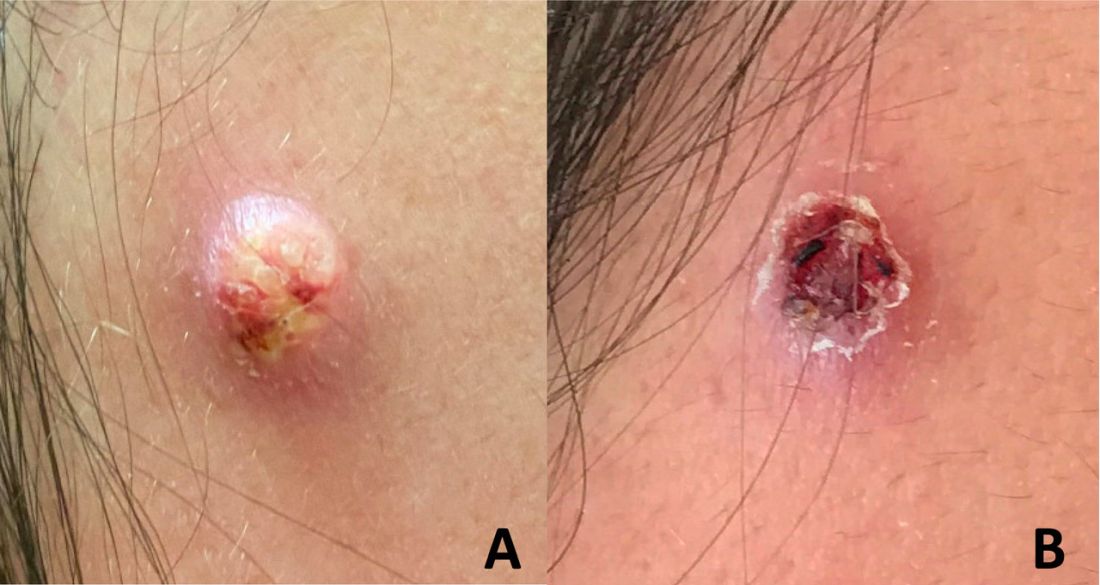

An adolescent male presents with an eroded bump on the temple

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

Will Congress step up to save primary care?

Primary care and family physicians operate on the front lines of health care, working tirelessly to serve patients and their families. However, many primary care practices are operating on tight margins and cannot sustain additional financial hits. As we continue to navigate a pandemic that has altered our health care landscape, we traveled to Capitol Hill to urge Congress to act on two critical issues: Medicare payment reform and streamlining administrative burden for physicians.

The current Medicare system for compensating physicians jeopardizes access to primary care. Family physicians, along with other primary care clinicians, are facing significant cuts in payments and rising inflation that threaten our ability to care for patients.

Each of us has experienced the effects of this pincer in devastating ways – from the independent clinicians who have been forced to sell their practices to hospitals or large health systems, to the physicians who are retiring early, leaving their practices, or even closing them because they can’t afford to keep their doors open.

Practices also struggle to cover the rising costs of staff wages, leasing space, and purchasing supplies and equipment, leaving little room for innovation or investments to transition into new payment models. Meanwhile, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, ambulatory surgery centers, and other Medicare providers receive annual payment increases to account for rising costs.

Insufficient Medicare payments also challenge practices that serve many publicly insured patients. If practices cannot cover their expenses, they may be forced to turn away new Medicare and Medicaid patients – something that goes against the core tenets of our health care system.

Fortunately, we have some solutions. We’re asking Congress to pass the Supporting Medicare Providers Act of 2022, which calls for a 4.42% positive adjustment to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) conversion factor for 2023 to offset the statutory reduction triggered by budget neutrality rules.

We also are calling on lawmakers to end the statutory freeze on annual updates to the MPFS and enact a positive annual update to the conversion factor based on the Medicare Economic Index. This critical relief would stave off the most immediate cuts while giving us more time to work with Congress on comprehensive reforms to the Medicare physician payment system.

As many practices struggle to operate, burnout among primary care physicians has also increased, with research showing that 66% of primary care physicians reported frequent burnout symptoms in 2021. Streamlining prior authorizations – a cumbersome process that requires physicians to obtain preapproval for treatments or tests before providing care to patients, and can risk patients’ access to timely care – is one way to reduce burden and alleviate burnout.

According to the American Medical Association, 82% of physicians report that prior authorization can lead to patients abandoning care, and 93% believe that prior authorization delays access to necessary care.

All of us have had patients whose care has been affected by these delays, including difficulty in getting necessary medications filled or having medical procedures postponed. Moreover, primary care physicians and their staff spend hours each week completing paperwork and communicating with insurers to ensure that their patients can access the treatments and services they need.

That is why we’re urging the Senate to pass the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act, which would streamline the prior authorization process in the Medicare Advantage program.

As family physicians, we are in a unique position to help improve our patients’ health and their quality of life. But we can’t do this alone. We need the support of policy makers to make patient health and primary care a national priority.

Dr. Iroku-Malize is a family physician in Long Island, New York, and President of the American Academy of Family Physicians. Dr. Ransone is a family physician in Deltaville, Va., and board chair, immediate past president of the AAFP. Dr. Furr is a family physician in Jackson, Ala., and President-elect of the AAFP. They reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care and family physicians operate on the front lines of health care, working tirelessly to serve patients and their families. However, many primary care practices are operating on tight margins and cannot sustain additional financial hits. As we continue to navigate a pandemic that has altered our health care landscape, we traveled to Capitol Hill to urge Congress to act on two critical issues: Medicare payment reform and streamlining administrative burden for physicians.

The current Medicare system for compensating physicians jeopardizes access to primary care. Family physicians, along with other primary care clinicians, are facing significant cuts in payments and rising inflation that threaten our ability to care for patients.

Each of us has experienced the effects of this pincer in devastating ways – from the independent clinicians who have been forced to sell their practices to hospitals or large health systems, to the physicians who are retiring early, leaving their practices, or even closing them because they can’t afford to keep their doors open.

Practices also struggle to cover the rising costs of staff wages, leasing space, and purchasing supplies and equipment, leaving little room for innovation or investments to transition into new payment models. Meanwhile, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, ambulatory surgery centers, and other Medicare providers receive annual payment increases to account for rising costs.

Insufficient Medicare payments also challenge practices that serve many publicly insured patients. If practices cannot cover their expenses, they may be forced to turn away new Medicare and Medicaid patients – something that goes against the core tenets of our health care system.

Fortunately, we have some solutions. We’re asking Congress to pass the Supporting Medicare Providers Act of 2022, which calls for a 4.42% positive adjustment to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) conversion factor for 2023 to offset the statutory reduction triggered by budget neutrality rules.

We also are calling on lawmakers to end the statutory freeze on annual updates to the MPFS and enact a positive annual update to the conversion factor based on the Medicare Economic Index. This critical relief would stave off the most immediate cuts while giving us more time to work with Congress on comprehensive reforms to the Medicare physician payment system.

As many practices struggle to operate, burnout among primary care physicians has also increased, with research showing that 66% of primary care physicians reported frequent burnout symptoms in 2021. Streamlining prior authorizations – a cumbersome process that requires physicians to obtain preapproval for treatments or tests before providing care to patients, and can risk patients’ access to timely care – is one way to reduce burden and alleviate burnout.

According to the American Medical Association, 82% of physicians report that prior authorization can lead to patients abandoning care, and 93% believe that prior authorization delays access to necessary care.