User login

The child with hypertension: Diagnosis and management

This transcript has been edited for clarity. The transcript and an accompanying video first appeared on Medscape.com.

Justin L. Berk, MD, MPH, MBA: Welcome back to The Cribsiders, our video recap of our pediatric medicine podcast. We interview leading experts in the field to bring clinical pearls and practice-changing knowledge, and answer lingering questions about core topics in pediatric medicine. Chris, what is our topic today?

Christopher J. Chiu, MD: I was really happy to be able to talk about our recent episode with Dr. Carissa Baker-Smith, a pediatric cardiologist and director of the Nemours preventive cardiology program. She helped us review the pediatric screening guidelines for blood pressure, including initial workup and treatment.

Dr. Berk: This was a really great episode that a lot of people found really helpful. What were some of the key takeaway pearls that you think listeners would be interested in?

Dr. Chiu: We talked about when and how we should be checking blood pressures in children. Blood pressure should be checked at every well-child visit starting at age 3. But if they have other risk factors like kidney disease or a condition such as coarctation of the aorta, then blood pressure should be checked at every visit.

Dr. Berk: One thing she spoke about was how blood pressures should be measured. How should we be checking blood pressures in the clinic?

Dr. Chiu: Clinic blood pressures are usually checked with oscillometric devices. They can differ by manufacturer, but basically they find a mean arterial pressure and then each device has a method of calculating systolic and diastolic pressures. Now after that, if the child’s blood pressure is maybe abnormal, you want to double-check a manual blood pressure using Korotkoff sounds to confirm the blood pressure.

She reminded us that blood pressure should be measured with the child sitting with their back supported, feet flat on the floor, and arm at the level of the heart. Make sure you use the right size cuff. The bladder of the cuff should be 40% of the width of the arm, and about 80%-100% of the arm circumference. She recommends sizing up if you have to.

Dr. Berk: Accuracy of blood pressure management was a really important point, especially for diagnosis at this stage. Can you walk us through what we learned about diagnosis of hypertension?

Dr. Chiu: The definitions of hypertension come from the Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Up until the age of 13, they define prehypertension as systolic and diastolic blood pressures between the 90th and 95th percentile, or if the blood pressure exceeds 120/80 mm Hg. Hypertension is defined when blood pressure reaches the 95th percentile. Now age 13 is when it gets a little hazy. Many changes in the guidelines happen at age 13, when hypertension starts being defined by adult guidelines. The 2017 adult hypertension guidelines define stage 1 hypertension as 130/89 to 139/89, and stage 2 hypertension as greater than 140/90.

Dr. Berk: How about workup of hypertension? The work of pediatric hypertension is always a little bit complex. What are some of the pearls you took away?

Dr. Chui: She talked about tailoring the workup to the child. So when we’re doing our workup, obviously physical exam should be the first thing we do. You have to assess and compare pulses, which is one of the most important parts of the initial evaluation. Obviously, looking at coarctation of the aorta, but also looking for things like a cushingoid appearance. If the child is less than 6 years of age, she recommends a referral to nephrology for more comprehensive renovascular workup, which probably will include renal ultrasound, urinalysis, metabolic panel, and thyroid studies.

We have to be cognizant of secondary causes of hypertension, such as endocrine tumors, hyperthyroidism, aortic disease, or even medication-induced hypertension. She told us that in the majority of these cases, especially with our obese older children, primary hypertension or essential hypertension is the most likely cause.

Dr. Berk: That was my big takeaway. If they’re really young, they need a big workup, but otherwise it is likely primary hypertension. What did we learn about treatment?

Dr. Chui: Just as we tailor our assessment to the child, we also have to tailor treatment. We know that lifestyle modification is usually the first line of treatment, especially for primary hypertension, and Dr. Baker-Smith tells us that we really need to perform counseling that meets the patient where they are. So if they like dancing to the newest TikTok trends or music videos, maybe we can encourage them to move more that way. Using our motivational interviewing skills is really key here.

If you want to start medication, Dr. Baker-Smith uses things like low-dose ACE inhibitors or calcium channel blockers, but obviously it’ll be tailored to the patient and any underlying conditions.

Dr. Berk: That’s great – a lot of wonderful pearls on the diagnosis and management of pediatric hypertension. Thank you for joining us for another video recap of The Cribsiders pediatric podcast. You can download the full podcast, Off the Cuff: Managing Pediatric Hypertension in Your Primary Care Clinic, on any podcast player, or check out our website at www.theCribsiders.com.

Christopher J. Chiu, MD, is assistant professor, department of internal medicine, division of general internal medicine, Ohio State University, Columbus; lead physician, general internal medicine, OSU Outpatient Care East; department of internal medicine, division of general internal medicine, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Dr. Chiu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Justin L. Berk, MD, MPH, MBA, is assistant professor, department of medicine; assistant professor, department of pediatrics, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

This transcript has been edited for clarity. The transcript and an accompanying video first appeared on Medscape.com.

Justin L. Berk, MD, MPH, MBA: Welcome back to The Cribsiders, our video recap of our pediatric medicine podcast. We interview leading experts in the field to bring clinical pearls and practice-changing knowledge, and answer lingering questions about core topics in pediatric medicine. Chris, what is our topic today?

Christopher J. Chiu, MD: I was really happy to be able to talk about our recent episode with Dr. Carissa Baker-Smith, a pediatric cardiologist and director of the Nemours preventive cardiology program. She helped us review the pediatric screening guidelines for blood pressure, including initial workup and treatment.

Dr. Berk: This was a really great episode that a lot of people found really helpful. What were some of the key takeaway pearls that you think listeners would be interested in?

Dr. Chiu: We talked about when and how we should be checking blood pressures in children. Blood pressure should be checked at every well-child visit starting at age 3. But if they have other risk factors like kidney disease or a condition such as coarctation of the aorta, then blood pressure should be checked at every visit.

Dr. Berk: One thing she spoke about was how blood pressures should be measured. How should we be checking blood pressures in the clinic?

Dr. Chiu: Clinic blood pressures are usually checked with oscillometric devices. They can differ by manufacturer, but basically they find a mean arterial pressure and then each device has a method of calculating systolic and diastolic pressures. Now after that, if the child’s blood pressure is maybe abnormal, you want to double-check a manual blood pressure using Korotkoff sounds to confirm the blood pressure.

She reminded us that blood pressure should be measured with the child sitting with their back supported, feet flat on the floor, and arm at the level of the heart. Make sure you use the right size cuff. The bladder of the cuff should be 40% of the width of the arm, and about 80%-100% of the arm circumference. She recommends sizing up if you have to.

Dr. Berk: Accuracy of blood pressure management was a really important point, especially for diagnosis at this stage. Can you walk us through what we learned about diagnosis of hypertension?

Dr. Chiu: The definitions of hypertension come from the Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Up until the age of 13, they define prehypertension as systolic and diastolic blood pressures between the 90th and 95th percentile, or if the blood pressure exceeds 120/80 mm Hg. Hypertension is defined when blood pressure reaches the 95th percentile. Now age 13 is when it gets a little hazy. Many changes in the guidelines happen at age 13, when hypertension starts being defined by adult guidelines. The 2017 adult hypertension guidelines define stage 1 hypertension as 130/89 to 139/89, and stage 2 hypertension as greater than 140/90.

Dr. Berk: How about workup of hypertension? The work of pediatric hypertension is always a little bit complex. What are some of the pearls you took away?

Dr. Chui: She talked about tailoring the workup to the child. So when we’re doing our workup, obviously physical exam should be the first thing we do. You have to assess and compare pulses, which is one of the most important parts of the initial evaluation. Obviously, looking at coarctation of the aorta, but also looking for things like a cushingoid appearance. If the child is less than 6 years of age, she recommends a referral to nephrology for more comprehensive renovascular workup, which probably will include renal ultrasound, urinalysis, metabolic panel, and thyroid studies.

We have to be cognizant of secondary causes of hypertension, such as endocrine tumors, hyperthyroidism, aortic disease, or even medication-induced hypertension. She told us that in the majority of these cases, especially with our obese older children, primary hypertension or essential hypertension is the most likely cause.

Dr. Berk: That was my big takeaway. If they’re really young, they need a big workup, but otherwise it is likely primary hypertension. What did we learn about treatment?

Dr. Chui: Just as we tailor our assessment to the child, we also have to tailor treatment. We know that lifestyle modification is usually the first line of treatment, especially for primary hypertension, and Dr. Baker-Smith tells us that we really need to perform counseling that meets the patient where they are. So if they like dancing to the newest TikTok trends or music videos, maybe we can encourage them to move more that way. Using our motivational interviewing skills is really key here.

If you want to start medication, Dr. Baker-Smith uses things like low-dose ACE inhibitors or calcium channel blockers, but obviously it’ll be tailored to the patient and any underlying conditions.

Dr. Berk: That’s great – a lot of wonderful pearls on the diagnosis and management of pediatric hypertension. Thank you for joining us for another video recap of The Cribsiders pediatric podcast. You can download the full podcast, Off the Cuff: Managing Pediatric Hypertension in Your Primary Care Clinic, on any podcast player, or check out our website at www.theCribsiders.com.

Christopher J. Chiu, MD, is assistant professor, department of internal medicine, division of general internal medicine, Ohio State University, Columbus; lead physician, general internal medicine, OSU Outpatient Care East; department of internal medicine, division of general internal medicine, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Dr. Chiu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Justin L. Berk, MD, MPH, MBA, is assistant professor, department of medicine; assistant professor, department of pediatrics, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

This transcript has been edited for clarity. The transcript and an accompanying video first appeared on Medscape.com.

Justin L. Berk, MD, MPH, MBA: Welcome back to The Cribsiders, our video recap of our pediatric medicine podcast. We interview leading experts in the field to bring clinical pearls and practice-changing knowledge, and answer lingering questions about core topics in pediatric medicine. Chris, what is our topic today?

Christopher J. Chiu, MD: I was really happy to be able to talk about our recent episode with Dr. Carissa Baker-Smith, a pediatric cardiologist and director of the Nemours preventive cardiology program. She helped us review the pediatric screening guidelines for blood pressure, including initial workup and treatment.

Dr. Berk: This was a really great episode that a lot of people found really helpful. What were some of the key takeaway pearls that you think listeners would be interested in?

Dr. Chiu: We talked about when and how we should be checking blood pressures in children. Blood pressure should be checked at every well-child visit starting at age 3. But if they have other risk factors like kidney disease or a condition such as coarctation of the aorta, then blood pressure should be checked at every visit.

Dr. Berk: One thing she spoke about was how blood pressures should be measured. How should we be checking blood pressures in the clinic?

Dr. Chiu: Clinic blood pressures are usually checked with oscillometric devices. They can differ by manufacturer, but basically they find a mean arterial pressure and then each device has a method of calculating systolic and diastolic pressures. Now after that, if the child’s blood pressure is maybe abnormal, you want to double-check a manual blood pressure using Korotkoff sounds to confirm the blood pressure.

She reminded us that blood pressure should be measured with the child sitting with their back supported, feet flat on the floor, and arm at the level of the heart. Make sure you use the right size cuff. The bladder of the cuff should be 40% of the width of the arm, and about 80%-100% of the arm circumference. She recommends sizing up if you have to.

Dr. Berk: Accuracy of blood pressure management was a really important point, especially for diagnosis at this stage. Can you walk us through what we learned about diagnosis of hypertension?

Dr. Chiu: The definitions of hypertension come from the Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Up until the age of 13, they define prehypertension as systolic and diastolic blood pressures between the 90th and 95th percentile, or if the blood pressure exceeds 120/80 mm Hg. Hypertension is defined when blood pressure reaches the 95th percentile. Now age 13 is when it gets a little hazy. Many changes in the guidelines happen at age 13, when hypertension starts being defined by adult guidelines. The 2017 adult hypertension guidelines define stage 1 hypertension as 130/89 to 139/89, and stage 2 hypertension as greater than 140/90.

Dr. Berk: How about workup of hypertension? The work of pediatric hypertension is always a little bit complex. What are some of the pearls you took away?

Dr. Chui: She talked about tailoring the workup to the child. So when we’re doing our workup, obviously physical exam should be the first thing we do. You have to assess and compare pulses, which is one of the most important parts of the initial evaluation. Obviously, looking at coarctation of the aorta, but also looking for things like a cushingoid appearance. If the child is less than 6 years of age, she recommends a referral to nephrology for more comprehensive renovascular workup, which probably will include renal ultrasound, urinalysis, metabolic panel, and thyroid studies.

We have to be cognizant of secondary causes of hypertension, such as endocrine tumors, hyperthyroidism, aortic disease, or even medication-induced hypertension. She told us that in the majority of these cases, especially with our obese older children, primary hypertension or essential hypertension is the most likely cause.

Dr. Berk: That was my big takeaway. If they’re really young, they need a big workup, but otherwise it is likely primary hypertension. What did we learn about treatment?

Dr. Chui: Just as we tailor our assessment to the child, we also have to tailor treatment. We know that lifestyle modification is usually the first line of treatment, especially for primary hypertension, and Dr. Baker-Smith tells us that we really need to perform counseling that meets the patient where they are. So if they like dancing to the newest TikTok trends or music videos, maybe we can encourage them to move more that way. Using our motivational interviewing skills is really key here.

If you want to start medication, Dr. Baker-Smith uses things like low-dose ACE inhibitors or calcium channel blockers, but obviously it’ll be tailored to the patient and any underlying conditions.

Dr. Berk: That’s great – a lot of wonderful pearls on the diagnosis and management of pediatric hypertension. Thank you for joining us for another video recap of The Cribsiders pediatric podcast. You can download the full podcast, Off the Cuff: Managing Pediatric Hypertension in Your Primary Care Clinic, on any podcast player, or check out our website at www.theCribsiders.com.

Christopher J. Chiu, MD, is assistant professor, department of internal medicine, division of general internal medicine, Ohio State University, Columbus; lead physician, general internal medicine, OSU Outpatient Care East; department of internal medicine, division of general internal medicine, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Dr. Chiu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Justin L. Berk, MD, MPH, MBA, is assistant professor, department of medicine; assistant professor, department of pediatrics, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Understanding the Intersection of Homelessness and Justice Involvement: Enhancing Veteran Suicide Prevention Through VA Programming

Despite the success of several US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) initiatives in facilitating psychosocial functioning, rehabilitation, and re-entry among veterans experiencing homelessness and/or interactions with the criminal justice system (ie, justice-involved veterans), suicide risk among these veterans remains a significant public health concern. Rates of suicide among veterans experiencing homelessness are more than double that of veterans with no history of homelessness.1 Similarly, justice-involved veterans experience myriad mental health concerns, including elevated rates of psychiatric symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and self-directed violence relative to those with no history of criminal justice involvement.2

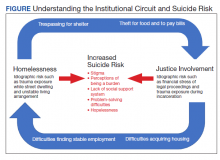

In addition, a bidirectional relationship between criminal justice involvement and homelessness, often called the “institutional circuit,” is well established. Criminal justice involvement can directly result in difficulty finding housing.3 For example, veterans may have their lease agreement denied based solely on their history of criminogenic behavior. Moreover, criminal justice involvement can indirectly impact a veteran’s ability to maintain housing. Indeed, justice-involved veterans can experience difficulty attaining and sustaining employment, which in turn can result in financial difficulties, including inability to afford rental or mortgage payments.

Similarly, those at risk for or experiencing housing instability may resort to criminogenic behavior to survive in the context of limited psychosocial resources.4-6 For instance, a veteran experiencing homelessness may seek refuge from inclement weather in a heated apartment stairwell and subsequently be charged with trespassing. Similarly, these veterans also may resort to theft to eat or pay bills. To this end, homelessness and justice involvement are likely a deleterious cycle that is difficult for the veteran to escape.

Unfortunately, the concurrent impact of housing insecurity and criminal justice involvement often serves to further exacerbate mental health sequelae, including suicide risk (Figure).7 In addition to precipitating frustration and helplessness among veterans who are navigating these stressors, these social determinants of health can engender a perception that the veteran is a burden to those in their support system. For example, these veterans may depend on friends or family to procure housing or transportation assistance for a job, medical appointments, and court hearings.

Furthermore, homelessness and justice involvement can impact veterans’ interpersonal relationships. For instance, veterans with a history of criminal justice involvement may feel stigmatized and ostracized from their social support system. Justice-involved veterans sometimes endorse being labeled an offender, which can result in perceptions that one is poorly perceived by others and generally seen as a bad person.8 In addition, the conditions of a justice-involved veteran’s probation or parole may further exacerbate social relationships. For example, veterans with histories of engaging in intimate partner violence may lose visitation rights with their children, further reinforcing negative views of self and impacting the veterans’ family network.

As such, these homeless and justice-involved veterans may lack a meaningful social support system when navigating psychosocial stressors. Because hopelessness, burdensomeness, and perceptions that one lacks a social support network are potential drivers of suicidal self-directed violence among these populations, facilitating access to and engagement in health (eg, psychotherapy, medication management) and social (eg, case management, transitional housing) services is necessary to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.9

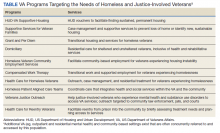

Several VA homeless and justice-related programs have been developed to meet the needs of these veterans (Table). Such programs offer direct access to health and social services capable of addressing mental health symptoms and suicide risk. Moreover, these programs support veterans at various intercepts, or points at which there is an opportunity to identify those at elevated risk and provide access to evidence-based care. For instance, VA homeless programs exist tailored toward those currently, or at risk for, experiencing homelessness. Additionally, VA justice-related programs can target intercepts prior to jail or prison, such as working with crisis intervention teams or diversion courts as well as intercepts following release, such as providing services to facilitate postincarceration reentry. Even VA programs that do not directly administer mental health intervention (eg, Grant and Per Diem, Veterans Justice Outreach) serve as critical points of contact that can connect these veterans to evidence-based suicide prevention treatments (eg, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention; pharmacotherapy) in the VA or the community.

Within these programs, several suicide prevention efforts also are currently underway. In particular, the VA has mandated routine screening for suicide risk. This includes screening for the presence of elevations in acute risk (eg, suicidal intent, recent suicide attempt) and, within the context of acute risk, conducting a comprehensive risk evaluation that captures veterans’ risk and protective factors as well as access to lethal means. These clinical data are used to determine the veteran’s severity of acute and chronic risk and match them to an appropriate intervention.

Despite these ongoing efforts, several gaps in understanding exist, such as for example, elucidating the potential role of traditional VA homeless and justice-related programming in reducing risk for suicide.10 Additional research specific to suicide prevention programming among these populations also remains important.11 In particular, no examination to date has evaluated national rates of suicide risk assessment within these settings or elucidated if specific subsets of homeless and justice-involved veterans may be less likely to receive suicide risk screening. For instance, understanding whether homeless veterans accessing mental health services are more likely to be screened for suicide risk relative to homeless veterans accessing care in other VA settings (eg, emergency services). Moreover, the effectiveness of existing suicide-focused evidence-based treatments among homeless and justice-involved veterans remains unknown. Such research may reveal a need to adapt existing interventions, such as safety planning, to the idiographic needs of homeless or justice-involved veterans in order to improve effectiveness.10 Finally, social determinants of health, such as race, ethnicity, gender, and rurality may confer additional risk coupled with difficulties accessing and engaging in care within these populations.11 As such, research specific to these veteran populations and their inherent suicide prevention needs may further inform suicide prevention efforts.

Despite these gaps, it is important to acknowledge ongoing research and programmatic efforts focused on enhancing mental health and suicide prevention practices within VA settings. For example, efforts led by Temblique and colleagues acknowledge not only challenges to the execution of suicide prevention efforts in VA homeless programs, but also potential methods of enhancing care, including additional training in suicide risk screening and evaluation due to provider discomfort.12 Such quality improvement projects are paramount in their potential to identify gaps in health service delivery and thus potentially save veteran lives.

The VA currently has several programs focused on enhancing care for homeless and justice-involved veterans, and many incorporate suicide prevention initiatives. Further understanding of factors that may impact health service delivery of suicide risk assessment and intervention among these populations may be beneficial in order to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.

1. McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, et al. Predictive modeling and concentration of the risk of suicide: implications for preventive interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935-1942. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302737

2. Holliday R, Hoffmire CA, Martin WB, Hoff RA, Monteith LL. Associations between justice involvement and PTSD and depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):730-739. doi:10.1037/tra0001038

3. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

4. Fischer PJ. Criminal activity among the homeless: a study of arrests in Baltimore. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(1):46-51. doi:10.1176/ps.39.1.46

5. McCarthy B, Hagan J. Homelessness: a criminogenic situation? Br J Criminol. 1991;31(4):393–410.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048137

6. Solomon P, Draine J. Issues in serving the forensic client. Soc Work. 1995;40(1):25-33.

7. Holliday R, Forster JE, Desai A, et al. Association of lifetime homelessness and justice involvement with psychiatric symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:455-461. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.007

8. Desai A, Holliday R, Borges LM, et al. Facilitating successful reentry among justice-involved veterans: the role of veteran and offender identity. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):52-60. Published 2021 Jan 21. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000520

9. Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2021;30(1):41-49. doi: 10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

10. Hoffberg AS, Spitzer E, Mackelprang JL, Farro SA, Brenner LA. Suicidal self-directed violence among homeless US veterans: a systematic review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(4):481-498. doi:10.1111/sltb.12369

11. Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs Suicide Prevention Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness Workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 2):S103-S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399.

12. Temblique EKR, Foster K, Fujimoto J, Kopelson K, Borthick KM, et al. Addressing the mental health crisis: a one year review of a nationally-led intervention to improve suicide prevention screening at a large homeless veterans clinic. Fed Pract. 2022;39(1):12-18. doi:10.12788/fp.0215

Despite the success of several US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) initiatives in facilitating psychosocial functioning, rehabilitation, and re-entry among veterans experiencing homelessness and/or interactions with the criminal justice system (ie, justice-involved veterans), suicide risk among these veterans remains a significant public health concern. Rates of suicide among veterans experiencing homelessness are more than double that of veterans with no history of homelessness.1 Similarly, justice-involved veterans experience myriad mental health concerns, including elevated rates of psychiatric symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and self-directed violence relative to those with no history of criminal justice involvement.2

In addition, a bidirectional relationship between criminal justice involvement and homelessness, often called the “institutional circuit,” is well established. Criminal justice involvement can directly result in difficulty finding housing.3 For example, veterans may have their lease agreement denied based solely on their history of criminogenic behavior. Moreover, criminal justice involvement can indirectly impact a veteran’s ability to maintain housing. Indeed, justice-involved veterans can experience difficulty attaining and sustaining employment, which in turn can result in financial difficulties, including inability to afford rental or mortgage payments.

Similarly, those at risk for or experiencing housing instability may resort to criminogenic behavior to survive in the context of limited psychosocial resources.4-6 For instance, a veteran experiencing homelessness may seek refuge from inclement weather in a heated apartment stairwell and subsequently be charged with trespassing. Similarly, these veterans also may resort to theft to eat or pay bills. To this end, homelessness and justice involvement are likely a deleterious cycle that is difficult for the veteran to escape.

Unfortunately, the concurrent impact of housing insecurity and criminal justice involvement often serves to further exacerbate mental health sequelae, including suicide risk (Figure).7 In addition to precipitating frustration and helplessness among veterans who are navigating these stressors, these social determinants of health can engender a perception that the veteran is a burden to those in their support system. For example, these veterans may depend on friends or family to procure housing or transportation assistance for a job, medical appointments, and court hearings.

Furthermore, homelessness and justice involvement can impact veterans’ interpersonal relationships. For instance, veterans with a history of criminal justice involvement may feel stigmatized and ostracized from their social support system. Justice-involved veterans sometimes endorse being labeled an offender, which can result in perceptions that one is poorly perceived by others and generally seen as a bad person.8 In addition, the conditions of a justice-involved veteran’s probation or parole may further exacerbate social relationships. For example, veterans with histories of engaging in intimate partner violence may lose visitation rights with their children, further reinforcing negative views of self and impacting the veterans’ family network.

As such, these homeless and justice-involved veterans may lack a meaningful social support system when navigating psychosocial stressors. Because hopelessness, burdensomeness, and perceptions that one lacks a social support network are potential drivers of suicidal self-directed violence among these populations, facilitating access to and engagement in health (eg, psychotherapy, medication management) and social (eg, case management, transitional housing) services is necessary to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.9

Several VA homeless and justice-related programs have been developed to meet the needs of these veterans (Table). Such programs offer direct access to health and social services capable of addressing mental health symptoms and suicide risk. Moreover, these programs support veterans at various intercepts, or points at which there is an opportunity to identify those at elevated risk and provide access to evidence-based care. For instance, VA homeless programs exist tailored toward those currently, or at risk for, experiencing homelessness. Additionally, VA justice-related programs can target intercepts prior to jail or prison, such as working with crisis intervention teams or diversion courts as well as intercepts following release, such as providing services to facilitate postincarceration reentry. Even VA programs that do not directly administer mental health intervention (eg, Grant and Per Diem, Veterans Justice Outreach) serve as critical points of contact that can connect these veterans to evidence-based suicide prevention treatments (eg, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention; pharmacotherapy) in the VA or the community.

Within these programs, several suicide prevention efforts also are currently underway. In particular, the VA has mandated routine screening for suicide risk. This includes screening for the presence of elevations in acute risk (eg, suicidal intent, recent suicide attempt) and, within the context of acute risk, conducting a comprehensive risk evaluation that captures veterans’ risk and protective factors as well as access to lethal means. These clinical data are used to determine the veteran’s severity of acute and chronic risk and match them to an appropriate intervention.

Despite these ongoing efforts, several gaps in understanding exist, such as for example, elucidating the potential role of traditional VA homeless and justice-related programming in reducing risk for suicide.10 Additional research specific to suicide prevention programming among these populations also remains important.11 In particular, no examination to date has evaluated national rates of suicide risk assessment within these settings or elucidated if specific subsets of homeless and justice-involved veterans may be less likely to receive suicide risk screening. For instance, understanding whether homeless veterans accessing mental health services are more likely to be screened for suicide risk relative to homeless veterans accessing care in other VA settings (eg, emergency services). Moreover, the effectiveness of existing suicide-focused evidence-based treatments among homeless and justice-involved veterans remains unknown. Such research may reveal a need to adapt existing interventions, such as safety planning, to the idiographic needs of homeless or justice-involved veterans in order to improve effectiveness.10 Finally, social determinants of health, such as race, ethnicity, gender, and rurality may confer additional risk coupled with difficulties accessing and engaging in care within these populations.11 As such, research specific to these veteran populations and their inherent suicide prevention needs may further inform suicide prevention efforts.

Despite these gaps, it is important to acknowledge ongoing research and programmatic efforts focused on enhancing mental health and suicide prevention practices within VA settings. For example, efforts led by Temblique and colleagues acknowledge not only challenges to the execution of suicide prevention efforts in VA homeless programs, but also potential methods of enhancing care, including additional training in suicide risk screening and evaluation due to provider discomfort.12 Such quality improvement projects are paramount in their potential to identify gaps in health service delivery and thus potentially save veteran lives.

The VA currently has several programs focused on enhancing care for homeless and justice-involved veterans, and many incorporate suicide prevention initiatives. Further understanding of factors that may impact health service delivery of suicide risk assessment and intervention among these populations may be beneficial in order to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.

Despite the success of several US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) initiatives in facilitating psychosocial functioning, rehabilitation, and re-entry among veterans experiencing homelessness and/or interactions with the criminal justice system (ie, justice-involved veterans), suicide risk among these veterans remains a significant public health concern. Rates of suicide among veterans experiencing homelessness are more than double that of veterans with no history of homelessness.1 Similarly, justice-involved veterans experience myriad mental health concerns, including elevated rates of psychiatric symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and self-directed violence relative to those with no history of criminal justice involvement.2

In addition, a bidirectional relationship between criminal justice involvement and homelessness, often called the “institutional circuit,” is well established. Criminal justice involvement can directly result in difficulty finding housing.3 For example, veterans may have their lease agreement denied based solely on their history of criminogenic behavior. Moreover, criminal justice involvement can indirectly impact a veteran’s ability to maintain housing. Indeed, justice-involved veterans can experience difficulty attaining and sustaining employment, which in turn can result in financial difficulties, including inability to afford rental or mortgage payments.

Similarly, those at risk for or experiencing housing instability may resort to criminogenic behavior to survive in the context of limited psychosocial resources.4-6 For instance, a veteran experiencing homelessness may seek refuge from inclement weather in a heated apartment stairwell and subsequently be charged with trespassing. Similarly, these veterans also may resort to theft to eat or pay bills. To this end, homelessness and justice involvement are likely a deleterious cycle that is difficult for the veteran to escape.

Unfortunately, the concurrent impact of housing insecurity and criminal justice involvement often serves to further exacerbate mental health sequelae, including suicide risk (Figure).7 In addition to precipitating frustration and helplessness among veterans who are navigating these stressors, these social determinants of health can engender a perception that the veteran is a burden to those in their support system. For example, these veterans may depend on friends or family to procure housing or transportation assistance for a job, medical appointments, and court hearings.

Furthermore, homelessness and justice involvement can impact veterans’ interpersonal relationships. For instance, veterans with a history of criminal justice involvement may feel stigmatized and ostracized from their social support system. Justice-involved veterans sometimes endorse being labeled an offender, which can result in perceptions that one is poorly perceived by others and generally seen as a bad person.8 In addition, the conditions of a justice-involved veteran’s probation or parole may further exacerbate social relationships. For example, veterans with histories of engaging in intimate partner violence may lose visitation rights with their children, further reinforcing negative views of self and impacting the veterans’ family network.

As such, these homeless and justice-involved veterans may lack a meaningful social support system when navigating psychosocial stressors. Because hopelessness, burdensomeness, and perceptions that one lacks a social support network are potential drivers of suicidal self-directed violence among these populations, facilitating access to and engagement in health (eg, psychotherapy, medication management) and social (eg, case management, transitional housing) services is necessary to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.9

Several VA homeless and justice-related programs have been developed to meet the needs of these veterans (Table). Such programs offer direct access to health and social services capable of addressing mental health symptoms and suicide risk. Moreover, these programs support veterans at various intercepts, or points at which there is an opportunity to identify those at elevated risk and provide access to evidence-based care. For instance, VA homeless programs exist tailored toward those currently, or at risk for, experiencing homelessness. Additionally, VA justice-related programs can target intercepts prior to jail or prison, such as working with crisis intervention teams or diversion courts as well as intercepts following release, such as providing services to facilitate postincarceration reentry. Even VA programs that do not directly administer mental health intervention (eg, Grant and Per Diem, Veterans Justice Outreach) serve as critical points of contact that can connect these veterans to evidence-based suicide prevention treatments (eg, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention; pharmacotherapy) in the VA or the community.

Within these programs, several suicide prevention efforts also are currently underway. In particular, the VA has mandated routine screening for suicide risk. This includes screening for the presence of elevations in acute risk (eg, suicidal intent, recent suicide attempt) and, within the context of acute risk, conducting a comprehensive risk evaluation that captures veterans’ risk and protective factors as well as access to lethal means. These clinical data are used to determine the veteran’s severity of acute and chronic risk and match them to an appropriate intervention.

Despite these ongoing efforts, several gaps in understanding exist, such as for example, elucidating the potential role of traditional VA homeless and justice-related programming in reducing risk for suicide.10 Additional research specific to suicide prevention programming among these populations also remains important.11 In particular, no examination to date has evaluated national rates of suicide risk assessment within these settings or elucidated if specific subsets of homeless and justice-involved veterans may be less likely to receive suicide risk screening. For instance, understanding whether homeless veterans accessing mental health services are more likely to be screened for suicide risk relative to homeless veterans accessing care in other VA settings (eg, emergency services). Moreover, the effectiveness of existing suicide-focused evidence-based treatments among homeless and justice-involved veterans remains unknown. Such research may reveal a need to adapt existing interventions, such as safety planning, to the idiographic needs of homeless or justice-involved veterans in order to improve effectiveness.10 Finally, social determinants of health, such as race, ethnicity, gender, and rurality may confer additional risk coupled with difficulties accessing and engaging in care within these populations.11 As such, research specific to these veteran populations and their inherent suicide prevention needs may further inform suicide prevention efforts.

Despite these gaps, it is important to acknowledge ongoing research and programmatic efforts focused on enhancing mental health and suicide prevention practices within VA settings. For example, efforts led by Temblique and colleagues acknowledge not only challenges to the execution of suicide prevention efforts in VA homeless programs, but also potential methods of enhancing care, including additional training in suicide risk screening and evaluation due to provider discomfort.12 Such quality improvement projects are paramount in their potential to identify gaps in health service delivery and thus potentially save veteran lives.

The VA currently has several programs focused on enhancing care for homeless and justice-involved veterans, and many incorporate suicide prevention initiatives. Further understanding of factors that may impact health service delivery of suicide risk assessment and intervention among these populations may be beneficial in order to enhance veteran suicide prevention efforts.

1. McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, et al. Predictive modeling and concentration of the risk of suicide: implications for preventive interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935-1942. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302737

2. Holliday R, Hoffmire CA, Martin WB, Hoff RA, Monteith LL. Associations between justice involvement and PTSD and depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):730-739. doi:10.1037/tra0001038

3. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

4. Fischer PJ. Criminal activity among the homeless: a study of arrests in Baltimore. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(1):46-51. doi:10.1176/ps.39.1.46

5. McCarthy B, Hagan J. Homelessness: a criminogenic situation? Br J Criminol. 1991;31(4):393–410.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048137

6. Solomon P, Draine J. Issues in serving the forensic client. Soc Work. 1995;40(1):25-33.

7. Holliday R, Forster JE, Desai A, et al. Association of lifetime homelessness and justice involvement with psychiatric symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:455-461. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.007

8. Desai A, Holliday R, Borges LM, et al. Facilitating successful reentry among justice-involved veterans: the role of veteran and offender identity. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):52-60. Published 2021 Jan 21. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000520

9. Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2021;30(1):41-49. doi: 10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

10. Hoffberg AS, Spitzer E, Mackelprang JL, Farro SA, Brenner LA. Suicidal self-directed violence among homeless US veterans: a systematic review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(4):481-498. doi:10.1111/sltb.12369

11. Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs Suicide Prevention Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness Workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 2):S103-S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399.

12. Temblique EKR, Foster K, Fujimoto J, Kopelson K, Borthick KM, et al. Addressing the mental health crisis: a one year review of a nationally-led intervention to improve suicide prevention screening at a large homeless veterans clinic. Fed Pract. 2022;39(1):12-18. doi:10.12788/fp.0215

1. McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, et al. Predictive modeling and concentration of the risk of suicide: implications for preventive interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935-1942. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302737

2. Holliday R, Hoffmire CA, Martin WB, Hoff RA, Monteith LL. Associations between justice involvement and PTSD and depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):730-739. doi:10.1037/tra0001038

3. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

4. Fischer PJ. Criminal activity among the homeless: a study of arrests in Baltimore. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(1):46-51. doi:10.1176/ps.39.1.46

5. McCarthy B, Hagan J. Homelessness: a criminogenic situation? Br J Criminol. 1991;31(4):393–410.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a048137

6. Solomon P, Draine J. Issues in serving the forensic client. Soc Work. 1995;40(1):25-33.

7. Holliday R, Forster JE, Desai A, et al. Association of lifetime homelessness and justice involvement with psychiatric symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:455-461. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.007

8. Desai A, Holliday R, Borges LM, et al. Facilitating successful reentry among justice-involved veterans: the role of veteran and offender identity. J Psychiatr Pract. 2021;27(1):52-60. Published 2021 Jan 21. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000520

9. Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2021;30(1):41-49. doi: 10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

10. Hoffberg AS, Spitzer E, Mackelprang JL, Farro SA, Brenner LA. Suicidal self-directed violence among homeless US veterans: a systematic review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(4):481-498. doi:10.1111/sltb.12369

11. Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs Suicide Prevention Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness Workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 2):S103-S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399.

12. Temblique EKR, Foster K, Fujimoto J, Kopelson K, Borthick KM, et al. Addressing the mental health crisis: a one year review of a nationally-led intervention to improve suicide prevention screening at a large homeless veterans clinic. Fed Pract. 2022;39(1):12-18. doi:10.12788/fp.0215

A Simple Message

I do not usually have difficulty writing editorials. However, this month was different. I kept coming up with grand ideas that flopped. First, I thought I would write a column entitled, “For What Should We Hope For?” When I started exploring the concept of hope, I quickly learned that there was extensive literature from multiple disciplines and even several centers and research projects dedicated to studying it.1 It seemed unlikely that I would have anything worthwhile to add to that literature. Then I thought I would discuss new year’s resolutions for federal practitioners. There was not much written about that topic, yet it seemed to be overly self-indulgent and superficial to discuss eating less and exercising more amid a pandemic and a climate change crisis. Finally, I wanted to opine on the futility of telling people to be resilient when we are all exhausted and demoralized, and yet that seemed too ponderous and paradoxical for our beleaguered state. With the third strike, I finally realized I was trying too hard. And perhaps that was exactly what I needed to say, at least to myself, and maybe some readers would benefit from reading that simple message as well.

I was surprised—though I probably should not have been given the explosion of media—to find that Americans were surveyed about what months they hate most. A 2021 poll of more than 15,000 adults found that January was the most disliked month.2 It’s not hard to figure out why. Characterized by a postholiday let down, these months in the middle of winter marked by either too much precipitation or if you live in the West not enough; short days and gray nights that are dark and cold. It is a long time to wait before spring with few holidays to break up the quotidian routine of work and school. January is a hard enough month in a good or even ordinary year. And 2022 is shaping up to be neither. We are entering the third year of a prolonged pandemic. Every time we have hope we are coming to the end of this long ordeal or at least things are moving toward normality, a new variant emerges, and we are back to living in fear and uncertainty.

COVID-19 is only the most relentless and deadly of our current disasters: There are rumors of wars, tornadoes, droughts, floods, shootings in schools and churches, political turmoil, and police violence. American society and the very planet seem to be in a perilous situation more than ever. No wonder then, that in the last month, several people have asked me, “Do you think this is the end of the world?” I suppose they think I am so old that I have become wise. And though I should cite a brilliant philosopher or renowned theologian: I am going to revert to my youth as a rock musician and quote R.E.M.: “It is the end of the world as we know it.” And “most of us do not feel fine!”

The world of 2022 is far more constricted and confined than it was before we heard the word COVID-19. We have less freedom of movement and fewer opportunities for companionship and gathering, for advancement and enjoyment. To thrive, and even to survive, in this cramped existence of limited possibilities, we need different values and attitudes than those that made us happy and successful in the open, hurried world before 2019. No generation since World War II has confronted such shortages of automobiles, paper goods, food, and even medicines as we have.

That is the first of the important simple messages I want to convey. Find something to be grateful for: your loved ones, your companion animals, your friends. Cherish the rainy or sunny day depending on how your climate has changed. Treasure the most basic and enduring pleasures, homemade cookies, favorite music, talking to a good friend even virtually, reading an actual book on a Sunday afternoon. These are things even the pandemic cannot take away from us unless we let our own inability to accept the conditions of our time ruin even what the meager, harsh Master of History has spared us.

The second of these simple messages is even more essential to finding any peace or joy in our current tense and somber existence: to show compassion for others and kindness to yourself. The most consistent report I have heard from people all over the country is that their fellow citizens are angry and selfish. We all understand, and even in some measure empathize with this the frustration and impatience with all the extraordinary pressure of having to function under these challenging conditions. Though we can take it out on the stranger at the grocery store or the family of the patient who has different views of masks and vaccines; it likely will not make the line shorter, the family any less demanding or seemingly unreasonable and probably will waste the little energy we have left to get home with the groceries or take care of the patient.

You never know what burden the person annoying you is carrying; it may perhaps be heavier than yours. And how we react to each other makes the weight of world weariness we all bear either easier or harder to shoulder. It sounds trite and trivial to say, yet tell people you care, and value, and love them. Although no less than Pope Francis in a Christmas present to marriages under strain from the stress of the pandemic that the 3 key words to remember are please, sorry, and thank you.3 I am applying that sage advice liberally to all relationships and interactions in the daily grind of work and home. The cost is little, the reward priceless.

It is good and right to have high hopes. We all need to take care of ourselves, whether we make resolutions to do so or not. Though more than anything else what we need is to be kind to ourselves. It is presumptuous of me to tell you what wellness means for your individual struggle, as it is inhuman of me to deign to tell you to be resilient when many of you face intolerable working conditions.4 As Jackson Browne sang in “Rock Me on the Water”, “Everyone must have some thought that’s going to pull them through somehow. Find your own thought, the reason you keep getting up and going to care for patients who increasingly respond with the rage of denial and resentment. Amid what morally distressed public health professionals have called so many unnecessary deaths,choose what gives you reason to keep serving that other side of this life full of healing.5 And if like so many of my fellow health care professionals, you are so spent and bent, that you feel that you can no longer practice without becoming someone you do not want to be, then let go with grace, get the help you deserve and perhaps one day when rested and mended, find another way to give.6

I rarely self-disclose but I want to end this column with a personal story that exemplifies more than all these words living this simple message. My spouse is a health care practitioner at a Veterans Affairs medical center. Like all of you on the front lines they work far too long hours in difficult conditions, with challenging patients and not enough staff to care for them. My partner had not an hour to get any gifts for me or our furry children. On Christmas Eve, before a long shift, they went to a packed Walgreens to buy our huskies each a toy and me a pair of fuzzy slippers. We sat by the tree and opened the hastily wrapped packages, and nothing could have been more memorable or meaningful. All of us at Federal Practitioner wish you, our readers, find in 2022 many such moments to sustain you.

1. The Center for the Advanced Study and Practice of Hope. T Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://thesanfordschool.asu.edu/research/centers-initiatives/hope-center

2. Ballard J. What is America’s favorite (and least favorite) month?” Published March 1, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/lifestyle/articles-reports/2021/03/01/favorite-least-favorite-month-poll

3. Winlfield N. Pope’s 3 key words for a marriage: ‘please, thanks sorry.’ Associated Press. December 26, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://apnews.com/article/pope-francis-lifestyle-religion-relationships-couples-23c81169982e50c35d1c1fc7bfef8cbc

4. Dineen K. Why resilience isn’t always the answer to coping with challenging times. Published September 29, 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://theconversation.com/why-resilience-isnt-always-the-answer-to-coping-with-challenging-times-145796

5. Caldwell T. ‘Everyone of those deaths is unnecessary,’ expert says of rising COVID-19 U.S. death toll as tens of millions remain unvaccinated. Published October 3, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/03/health/us-coronavirus-sunday/index.html 6. Yong E. Why healthcare professionals are quitting in droves. The Atlantic. November 16, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/11/the-mass-exodus-of-americas-health-care-workers/620713/

I do not usually have difficulty writing editorials. However, this month was different. I kept coming up with grand ideas that flopped. First, I thought I would write a column entitled, “For What Should We Hope For?” When I started exploring the concept of hope, I quickly learned that there was extensive literature from multiple disciplines and even several centers and research projects dedicated to studying it.1 It seemed unlikely that I would have anything worthwhile to add to that literature. Then I thought I would discuss new year’s resolutions for federal practitioners. There was not much written about that topic, yet it seemed to be overly self-indulgent and superficial to discuss eating less and exercising more amid a pandemic and a climate change crisis. Finally, I wanted to opine on the futility of telling people to be resilient when we are all exhausted and demoralized, and yet that seemed too ponderous and paradoxical for our beleaguered state. With the third strike, I finally realized I was trying too hard. And perhaps that was exactly what I needed to say, at least to myself, and maybe some readers would benefit from reading that simple message as well.

I was surprised—though I probably should not have been given the explosion of media—to find that Americans were surveyed about what months they hate most. A 2021 poll of more than 15,000 adults found that January was the most disliked month.2 It’s not hard to figure out why. Characterized by a postholiday let down, these months in the middle of winter marked by either too much precipitation or if you live in the West not enough; short days and gray nights that are dark and cold. It is a long time to wait before spring with few holidays to break up the quotidian routine of work and school. January is a hard enough month in a good or even ordinary year. And 2022 is shaping up to be neither. We are entering the third year of a prolonged pandemic. Every time we have hope we are coming to the end of this long ordeal or at least things are moving toward normality, a new variant emerges, and we are back to living in fear and uncertainty.

COVID-19 is only the most relentless and deadly of our current disasters: There are rumors of wars, tornadoes, droughts, floods, shootings in schools and churches, political turmoil, and police violence. American society and the very planet seem to be in a perilous situation more than ever. No wonder then, that in the last month, several people have asked me, “Do you think this is the end of the world?” I suppose they think I am so old that I have become wise. And though I should cite a brilliant philosopher or renowned theologian: I am going to revert to my youth as a rock musician and quote R.E.M.: “It is the end of the world as we know it.” And “most of us do not feel fine!”

The world of 2022 is far more constricted and confined than it was before we heard the word COVID-19. We have less freedom of movement and fewer opportunities for companionship and gathering, for advancement and enjoyment. To thrive, and even to survive, in this cramped existence of limited possibilities, we need different values and attitudes than those that made us happy and successful in the open, hurried world before 2019. No generation since World War II has confronted such shortages of automobiles, paper goods, food, and even medicines as we have.

That is the first of the important simple messages I want to convey. Find something to be grateful for: your loved ones, your companion animals, your friends. Cherish the rainy or sunny day depending on how your climate has changed. Treasure the most basic and enduring pleasures, homemade cookies, favorite music, talking to a good friend even virtually, reading an actual book on a Sunday afternoon. These are things even the pandemic cannot take away from us unless we let our own inability to accept the conditions of our time ruin even what the meager, harsh Master of History has spared us.

The second of these simple messages is even more essential to finding any peace or joy in our current tense and somber existence: to show compassion for others and kindness to yourself. The most consistent report I have heard from people all over the country is that their fellow citizens are angry and selfish. We all understand, and even in some measure empathize with this the frustration and impatience with all the extraordinary pressure of having to function under these challenging conditions. Though we can take it out on the stranger at the grocery store or the family of the patient who has different views of masks and vaccines; it likely will not make the line shorter, the family any less demanding or seemingly unreasonable and probably will waste the little energy we have left to get home with the groceries or take care of the patient.

You never know what burden the person annoying you is carrying; it may perhaps be heavier than yours. And how we react to each other makes the weight of world weariness we all bear either easier or harder to shoulder. It sounds trite and trivial to say, yet tell people you care, and value, and love them. Although no less than Pope Francis in a Christmas present to marriages under strain from the stress of the pandemic that the 3 key words to remember are please, sorry, and thank you.3 I am applying that sage advice liberally to all relationships and interactions in the daily grind of work and home. The cost is little, the reward priceless.

It is good and right to have high hopes. We all need to take care of ourselves, whether we make resolutions to do so or not. Though more than anything else what we need is to be kind to ourselves. It is presumptuous of me to tell you what wellness means for your individual struggle, as it is inhuman of me to deign to tell you to be resilient when many of you face intolerable working conditions.4 As Jackson Browne sang in “Rock Me on the Water”, “Everyone must have some thought that’s going to pull them through somehow. Find your own thought, the reason you keep getting up and going to care for patients who increasingly respond with the rage of denial and resentment. Amid what morally distressed public health professionals have called so many unnecessary deaths,choose what gives you reason to keep serving that other side of this life full of healing.5 And if like so many of my fellow health care professionals, you are so spent and bent, that you feel that you can no longer practice without becoming someone you do not want to be, then let go with grace, get the help you deserve and perhaps one day when rested and mended, find another way to give.6

I rarely self-disclose but I want to end this column with a personal story that exemplifies more than all these words living this simple message. My spouse is a health care practitioner at a Veterans Affairs medical center. Like all of you on the front lines they work far too long hours in difficult conditions, with challenging patients and not enough staff to care for them. My partner had not an hour to get any gifts for me or our furry children. On Christmas Eve, before a long shift, they went to a packed Walgreens to buy our huskies each a toy and me a pair of fuzzy slippers. We sat by the tree and opened the hastily wrapped packages, and nothing could have been more memorable or meaningful. All of us at Federal Practitioner wish you, our readers, find in 2022 many such moments to sustain you.

I do not usually have difficulty writing editorials. However, this month was different. I kept coming up with grand ideas that flopped. First, I thought I would write a column entitled, “For What Should We Hope For?” When I started exploring the concept of hope, I quickly learned that there was extensive literature from multiple disciplines and even several centers and research projects dedicated to studying it.1 It seemed unlikely that I would have anything worthwhile to add to that literature. Then I thought I would discuss new year’s resolutions for federal practitioners. There was not much written about that topic, yet it seemed to be overly self-indulgent and superficial to discuss eating less and exercising more amid a pandemic and a climate change crisis. Finally, I wanted to opine on the futility of telling people to be resilient when we are all exhausted and demoralized, and yet that seemed too ponderous and paradoxical for our beleaguered state. With the third strike, I finally realized I was trying too hard. And perhaps that was exactly what I needed to say, at least to myself, and maybe some readers would benefit from reading that simple message as well.

I was surprised—though I probably should not have been given the explosion of media—to find that Americans were surveyed about what months they hate most. A 2021 poll of more than 15,000 adults found that January was the most disliked month.2 It’s not hard to figure out why. Characterized by a postholiday let down, these months in the middle of winter marked by either too much precipitation or if you live in the West not enough; short days and gray nights that are dark and cold. It is a long time to wait before spring with few holidays to break up the quotidian routine of work and school. January is a hard enough month in a good or even ordinary year. And 2022 is shaping up to be neither. We are entering the third year of a prolonged pandemic. Every time we have hope we are coming to the end of this long ordeal or at least things are moving toward normality, a new variant emerges, and we are back to living in fear and uncertainty.

COVID-19 is only the most relentless and deadly of our current disasters: There are rumors of wars, tornadoes, droughts, floods, shootings in schools and churches, political turmoil, and police violence. American society and the very planet seem to be in a perilous situation more than ever. No wonder then, that in the last month, several people have asked me, “Do you think this is the end of the world?” I suppose they think I am so old that I have become wise. And though I should cite a brilliant philosopher or renowned theologian: I am going to revert to my youth as a rock musician and quote R.E.M.: “It is the end of the world as we know it.” And “most of us do not feel fine!”

The world of 2022 is far more constricted and confined than it was before we heard the word COVID-19. We have less freedom of movement and fewer opportunities for companionship and gathering, for advancement and enjoyment. To thrive, and even to survive, in this cramped existence of limited possibilities, we need different values and attitudes than those that made us happy and successful in the open, hurried world before 2019. No generation since World War II has confronted such shortages of automobiles, paper goods, food, and even medicines as we have.

That is the first of the important simple messages I want to convey. Find something to be grateful for: your loved ones, your companion animals, your friends. Cherish the rainy or sunny day depending on how your climate has changed. Treasure the most basic and enduring pleasures, homemade cookies, favorite music, talking to a good friend even virtually, reading an actual book on a Sunday afternoon. These are things even the pandemic cannot take away from us unless we let our own inability to accept the conditions of our time ruin even what the meager, harsh Master of History has spared us.

The second of these simple messages is even more essential to finding any peace or joy in our current tense and somber existence: to show compassion for others and kindness to yourself. The most consistent report I have heard from people all over the country is that their fellow citizens are angry and selfish. We all understand, and even in some measure empathize with this the frustration and impatience with all the extraordinary pressure of having to function under these challenging conditions. Though we can take it out on the stranger at the grocery store or the family of the patient who has different views of masks and vaccines; it likely will not make the line shorter, the family any less demanding or seemingly unreasonable and probably will waste the little energy we have left to get home with the groceries or take care of the patient.

You never know what burden the person annoying you is carrying; it may perhaps be heavier than yours. And how we react to each other makes the weight of world weariness we all bear either easier or harder to shoulder. It sounds trite and trivial to say, yet tell people you care, and value, and love them. Although no less than Pope Francis in a Christmas present to marriages under strain from the stress of the pandemic that the 3 key words to remember are please, sorry, and thank you.3 I am applying that sage advice liberally to all relationships and interactions in the daily grind of work and home. The cost is little, the reward priceless.

It is good and right to have high hopes. We all need to take care of ourselves, whether we make resolutions to do so or not. Though more than anything else what we need is to be kind to ourselves. It is presumptuous of me to tell you what wellness means for your individual struggle, as it is inhuman of me to deign to tell you to be resilient when many of you face intolerable working conditions.4 As Jackson Browne sang in “Rock Me on the Water”, “Everyone must have some thought that’s going to pull them through somehow. Find your own thought, the reason you keep getting up and going to care for patients who increasingly respond with the rage of denial and resentment. Amid what morally distressed public health professionals have called so many unnecessary deaths,choose what gives you reason to keep serving that other side of this life full of healing.5 And if like so many of my fellow health care professionals, you are so spent and bent, that you feel that you can no longer practice without becoming someone you do not want to be, then let go with grace, get the help you deserve and perhaps one day when rested and mended, find another way to give.6

I rarely self-disclose but I want to end this column with a personal story that exemplifies more than all these words living this simple message. My spouse is a health care practitioner at a Veterans Affairs medical center. Like all of you on the front lines they work far too long hours in difficult conditions, with challenging patients and not enough staff to care for them. My partner had not an hour to get any gifts for me or our furry children. On Christmas Eve, before a long shift, they went to a packed Walgreens to buy our huskies each a toy and me a pair of fuzzy slippers. We sat by the tree and opened the hastily wrapped packages, and nothing could have been more memorable or meaningful. All of us at Federal Practitioner wish you, our readers, find in 2022 many such moments to sustain you.

1. The Center for the Advanced Study and Practice of Hope. T Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://thesanfordschool.asu.edu/research/centers-initiatives/hope-center

2. Ballard J. What is America’s favorite (and least favorite) month?” Published March 1, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/lifestyle/articles-reports/2021/03/01/favorite-least-favorite-month-poll

3. Winlfield N. Pope’s 3 key words for a marriage: ‘please, thanks sorry.’ Associated Press. December 26, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://apnews.com/article/pope-francis-lifestyle-religion-relationships-couples-23c81169982e50c35d1c1fc7bfef8cbc

4. Dineen K. Why resilience isn’t always the answer to coping with challenging times. Published September 29, 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://theconversation.com/why-resilience-isnt-always-the-answer-to-coping-with-challenging-times-145796

5. Caldwell T. ‘Everyone of those deaths is unnecessary,’ expert says of rising COVID-19 U.S. death toll as tens of millions remain unvaccinated. Published October 3, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/03/health/us-coronavirus-sunday/index.html 6. Yong E. Why healthcare professionals are quitting in droves. The Atlantic. November 16, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/11/the-mass-exodus-of-americas-health-care-workers/620713/

1. The Center for the Advanced Study and Practice of Hope. T Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://thesanfordschool.asu.edu/research/centers-initiatives/hope-center

2. Ballard J. What is America’s favorite (and least favorite) month?” Published March 1, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/lifestyle/articles-reports/2021/03/01/favorite-least-favorite-month-poll

3. Winlfield N. Pope’s 3 key words for a marriage: ‘please, thanks sorry.’ Associated Press. December 26, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://apnews.com/article/pope-francis-lifestyle-religion-relationships-couples-23c81169982e50c35d1c1fc7bfef8cbc

4. Dineen K. Why resilience isn’t always the answer to coping with challenging times. Published September 29, 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://theconversation.com/why-resilience-isnt-always-the-answer-to-coping-with-challenging-times-145796

5. Caldwell T. ‘Everyone of those deaths is unnecessary,’ expert says of rising COVID-19 U.S. death toll as tens of millions remain unvaccinated. Published October 3, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/03/health/us-coronavirus-sunday/index.html 6. Yong E. Why healthcare professionals are quitting in droves. The Atlantic. November 16, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/11/the-mass-exodus-of-americas-health-care-workers/620713/

Teledermatology During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned and Future Directions

Although teledermatology utilization in the United States traditionally has lagged behind other countries,1,2 the COVID-19 pandemic upended this trend by creating the need for a massive teledermatology experiment. Recently reported survey results from a large representative sample of US dermatologists (5000 participants) on perceptions of teledermatology during COVID-19 indicated that only 14.1% of participants used teledermatology prior to the COVID-19 pandemic vs 54.1% of dermatologists in Europe.2,3 Since the pandemic started, 97% of US dermatologists reported teledermatology use,3 demonstrating a huge shift in utilization. This trend is notable, as teledermatology has been shown to increase access to dermatology in underserved areas, reduce patient travel times, improve patient triage, and even reduce carbon footprints.1,4 Thus, to sustain the momentum, insights from the recent teledermatology experience during the pandemic should inform future development.

Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rapid shift in focus from store-and-forward teledermatology to live video–based models.1,2 Logistically, live video visits are challenging, require more time and resources, and often are diagnostically limited, with concerns regarding technology, connectivity, reimbursement, and appropriate use.3 Prior to COVID-19, formal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant teledermatology platforms often were costly to establish and maintain, largely relegating use to academic centers and Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thus, many fewer private practice dermatologists had used teledermatology compared to academic dermatologists in the United States (11.4% vs 27.6%).3 Government regulations—a key barrier to the adoption of teledermatology in private practice before COVID-19—were greatly relaxed during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed restrictions on where patients could be seen, improved reimbursement for video visits, and allowed the use of platforms that are not Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. Many states also relaxed medical licensing rules.