User login

Study: Central sleep apnea is common in ticagrelor users post ACS

The prevalence of asymptomatic central sleep apnea after acute coronary syndrome is high and may be associated with the use of ticagrelor, a new study finds.

Prior studies have suggested that ticagrelor is associated with an increased likelihood of central sleep apnea. The drug’s label notes that two respiratory conditions – central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration – are adverse reactions that were identified after the drug’s approval in the United States in 2011. “Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of an unknown size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure,” the label says.

Among 80 patients receiving ticagrelor, 24 had central sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (CSAHS), whereas of 41 patients not taking ticagrelor, 3 had this condition (30% vs. 7.3%, P = .004), in the new study published online Jan. 20, 2021, in Sleep Medicine. A multivariable analysis included in the paper found that age and ticagrelor administration were the only two factors associated with the occurrence of CSAHS.

Findings are ‘striking’

The different rates of central sleep apnea in the study are striking, but it is not clear that asymptomatic central sleep apnea in patients taking ticagrelor is a concern, Ofer Jacobowitz, MD, PhD, associate professor of otolaryngology at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y, said in an interview.

“Whether this particular drug-induced central sleep apnea is consequential” is an open question, noted Dr. Jacobowitz. “There is no evidence that shows that this is definitely harmful.”

“The different types of central sleep apnea are caused by different mechanisms and this one, we don’t know,” Dr. Jacobwitz added.

Study author continues to prescribe ticagrelor

One of the study authors, Philippe Meurin, MD, said that he continues to prescribe ticagrelor every day and that the side effect is not necessarily important.

It is possible that central sleep apnea may resolve, although further studies would need to examine central sleep apnea over time to establish the duration of the condition, he added. Nevertheless, awareness of the association could have implications for clinical practice, Dr. Meurin said.

Central sleep apnea is rare, and if doctors detect it during a sleep study, they may perform extensive tests to assess for possible neurologic diseases, for example, when the cause may be attributed to the medication, he said. In addition, if a patient who is taking ticagrelor has dyspnea, the presence of central sleep apnea may suggest that dyspnea could be related to the drug, although this possibility needs further study, he noted.

Study included patients with ACS history, but no heart failure

Dr. Meurin, of Centre de Réadaptation Cardiaque de La Brie, Les Grands Prés, Villeneuve-Saint-Denis, France, and colleagues included in their study patients between 1 week and 1 year after acute coronary syndrome who did not have heart failure or a history of sleep apnea.

After an overnight sleep study, they classified patients as normal, as having CSAHS (i.e., an apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or greater, mostly with central sleep apneas), or as having obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS; i.e., an apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or greater, mostly with obstructive sleep apneas).

The prospective study included 121 consecutive patients between January 2018 and March 2020. Patients had a mean age of 56.8, and 88% were men.

Switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor ‘does not seem appropriate’

“CSAHS could be promoted by the use of ticagrelor, a relatively new drug that modifies the apneic threshold,” the study authors wrote. “Regarding underlying mechanisms, the most probable explanation seems to be increased chemosensitivity to hypercapnia by a direct P2Y12 inhibitory effect on the central nervous system.”

Doctors should not overestimate the severity of the adverse reaction or consider it the same way they do OSASH, they added.

Among patients with acute coronary syndrome in the PLATO study, ticagrelor, compared with clopidogrel, “significantly reduced the rate of death from vascular causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke,” Dr. Meurin and colleagues said. “Because in this study more than 9,000 patients received ticagrelor for 12 months, CSAHS (even if it seems frequent in our study) did not seem to impair the good efficacy/tolerance balance of the drug. Therefore, in asymptomatic CSAHS patients, switching from ticagrelor to another P2Y12 inhibitor does not seem appropriate.”

A recent analysis of data from randomized, controlled trials with ticagrelor did not find excess cases of sleep apnea with the drug. But an asymptomatic adverse event such as central sleep apnea “cannot emerge from a post hoc analysis,” Dr. Meurin and colleagues said.

The analysis of randomized trial data was conducted by Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, chairman of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and coauthors. It was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions in April 2020.

They “used the gold standard for medical evidence (randomized, placebo-controlled trials) and found 158 cases of sleep apnea reported, with absolutely no difference between ticagrelor and placebo,” Dr. Sabatine said in an interview. Their analysis examined clinically overt apnea, he noted.

“It is quite clear that when looking at large numbers in placebo-controlled trials, there is no excess,” Dr. Sabatine said. “Meurin et al. are examining a different outcome: the results of a lab test in what may be entirely asymptomatic patients.”

A randomized trial could confirm the association, he said.

“The association may be real, but also may be play of chance or confounded,” said Dr. Sabatine. “To convince the medical community, the next step would be for the investigators to do a randomized trial and test whether ticagrelor increases the risk of central sleep apnea.”

Dr. Meurin and the study coauthors had no disclosures. The analysis of randomized, controlled trial data by Dr. Sabatine and colleagues was funded by AstraZeneca, which distributes ticagrelor under the trade name Brilinta. Dr. Sabatine has been a consultant for AstraZeneca and received research grants through Brigham and Women’s Hospital from AstraZeneca. He has consulted for and received grants through the hospital from other companies as well. Dr. Jacobowitz had no relevant disclosures.

jremaly@mdedge.com

The prevalence of asymptomatic central sleep apnea after acute coronary syndrome is high and may be associated with the use of ticagrelor, a new study finds.

Prior studies have suggested that ticagrelor is associated with an increased likelihood of central sleep apnea. The drug’s label notes that two respiratory conditions – central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration – are adverse reactions that were identified after the drug’s approval in the United States in 2011. “Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of an unknown size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure,” the label says.

Among 80 patients receiving ticagrelor, 24 had central sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (CSAHS), whereas of 41 patients not taking ticagrelor, 3 had this condition (30% vs. 7.3%, P = .004), in the new study published online Jan. 20, 2021, in Sleep Medicine. A multivariable analysis included in the paper found that age and ticagrelor administration were the only two factors associated with the occurrence of CSAHS.

Findings are ‘striking’

The different rates of central sleep apnea in the study are striking, but it is not clear that asymptomatic central sleep apnea in patients taking ticagrelor is a concern, Ofer Jacobowitz, MD, PhD, associate professor of otolaryngology at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y, said in an interview.

“Whether this particular drug-induced central sleep apnea is consequential” is an open question, noted Dr. Jacobowitz. “There is no evidence that shows that this is definitely harmful.”

“The different types of central sleep apnea are caused by different mechanisms and this one, we don’t know,” Dr. Jacobwitz added.

Study author continues to prescribe ticagrelor

One of the study authors, Philippe Meurin, MD, said that he continues to prescribe ticagrelor every day and that the side effect is not necessarily important.

It is possible that central sleep apnea may resolve, although further studies would need to examine central sleep apnea over time to establish the duration of the condition, he added. Nevertheless, awareness of the association could have implications for clinical practice, Dr. Meurin said.

Central sleep apnea is rare, and if doctors detect it during a sleep study, they may perform extensive tests to assess for possible neurologic diseases, for example, when the cause may be attributed to the medication, he said. In addition, if a patient who is taking ticagrelor has dyspnea, the presence of central sleep apnea may suggest that dyspnea could be related to the drug, although this possibility needs further study, he noted.

Study included patients with ACS history, but no heart failure

Dr. Meurin, of Centre de Réadaptation Cardiaque de La Brie, Les Grands Prés, Villeneuve-Saint-Denis, France, and colleagues included in their study patients between 1 week and 1 year after acute coronary syndrome who did not have heart failure or a history of sleep apnea.

After an overnight sleep study, they classified patients as normal, as having CSAHS (i.e., an apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or greater, mostly with central sleep apneas), or as having obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS; i.e., an apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or greater, mostly with obstructive sleep apneas).

The prospective study included 121 consecutive patients between January 2018 and March 2020. Patients had a mean age of 56.8, and 88% were men.

Switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor ‘does not seem appropriate’

“CSAHS could be promoted by the use of ticagrelor, a relatively new drug that modifies the apneic threshold,” the study authors wrote. “Regarding underlying mechanisms, the most probable explanation seems to be increased chemosensitivity to hypercapnia by a direct P2Y12 inhibitory effect on the central nervous system.”

Doctors should not overestimate the severity of the adverse reaction or consider it the same way they do OSASH, they added.

Among patients with acute coronary syndrome in the PLATO study, ticagrelor, compared with clopidogrel, “significantly reduced the rate of death from vascular causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke,” Dr. Meurin and colleagues said. “Because in this study more than 9,000 patients received ticagrelor for 12 months, CSAHS (even if it seems frequent in our study) did not seem to impair the good efficacy/tolerance balance of the drug. Therefore, in asymptomatic CSAHS patients, switching from ticagrelor to another P2Y12 inhibitor does not seem appropriate.”

A recent analysis of data from randomized, controlled trials with ticagrelor did not find excess cases of sleep apnea with the drug. But an asymptomatic adverse event such as central sleep apnea “cannot emerge from a post hoc analysis,” Dr. Meurin and colleagues said.

The analysis of randomized trial data was conducted by Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, chairman of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and coauthors. It was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions in April 2020.

They “used the gold standard for medical evidence (randomized, placebo-controlled trials) and found 158 cases of sleep apnea reported, with absolutely no difference between ticagrelor and placebo,” Dr. Sabatine said in an interview. Their analysis examined clinically overt apnea, he noted.

“It is quite clear that when looking at large numbers in placebo-controlled trials, there is no excess,” Dr. Sabatine said. “Meurin et al. are examining a different outcome: the results of a lab test in what may be entirely asymptomatic patients.”

A randomized trial could confirm the association, he said.

“The association may be real, but also may be play of chance or confounded,” said Dr. Sabatine. “To convince the medical community, the next step would be for the investigators to do a randomized trial and test whether ticagrelor increases the risk of central sleep apnea.”

Dr. Meurin and the study coauthors had no disclosures. The analysis of randomized, controlled trial data by Dr. Sabatine and colleagues was funded by AstraZeneca, which distributes ticagrelor under the trade name Brilinta. Dr. Sabatine has been a consultant for AstraZeneca and received research grants through Brigham and Women’s Hospital from AstraZeneca. He has consulted for and received grants through the hospital from other companies as well. Dr. Jacobowitz had no relevant disclosures.

jremaly@mdedge.com

The prevalence of asymptomatic central sleep apnea after acute coronary syndrome is high and may be associated with the use of ticagrelor, a new study finds.

Prior studies have suggested that ticagrelor is associated with an increased likelihood of central sleep apnea. The drug’s label notes that two respiratory conditions – central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration – are adverse reactions that were identified after the drug’s approval in the United States in 2011. “Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of an unknown size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure,” the label says.

Among 80 patients receiving ticagrelor, 24 had central sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (CSAHS), whereas of 41 patients not taking ticagrelor, 3 had this condition (30% vs. 7.3%, P = .004), in the new study published online Jan. 20, 2021, in Sleep Medicine. A multivariable analysis included in the paper found that age and ticagrelor administration were the only two factors associated with the occurrence of CSAHS.

Findings are ‘striking’

The different rates of central sleep apnea in the study are striking, but it is not clear that asymptomatic central sleep apnea in patients taking ticagrelor is a concern, Ofer Jacobowitz, MD, PhD, associate professor of otolaryngology at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y, said in an interview.

“Whether this particular drug-induced central sleep apnea is consequential” is an open question, noted Dr. Jacobowitz. “There is no evidence that shows that this is definitely harmful.”

“The different types of central sleep apnea are caused by different mechanisms and this one, we don’t know,” Dr. Jacobwitz added.

Study author continues to prescribe ticagrelor

One of the study authors, Philippe Meurin, MD, said that he continues to prescribe ticagrelor every day and that the side effect is not necessarily important.

It is possible that central sleep apnea may resolve, although further studies would need to examine central sleep apnea over time to establish the duration of the condition, he added. Nevertheless, awareness of the association could have implications for clinical practice, Dr. Meurin said.

Central sleep apnea is rare, and if doctors detect it during a sleep study, they may perform extensive tests to assess for possible neurologic diseases, for example, when the cause may be attributed to the medication, he said. In addition, if a patient who is taking ticagrelor has dyspnea, the presence of central sleep apnea may suggest that dyspnea could be related to the drug, although this possibility needs further study, he noted.

Study included patients with ACS history, but no heart failure

Dr. Meurin, of Centre de Réadaptation Cardiaque de La Brie, Les Grands Prés, Villeneuve-Saint-Denis, France, and colleagues included in their study patients between 1 week and 1 year after acute coronary syndrome who did not have heart failure or a history of sleep apnea.

After an overnight sleep study, they classified patients as normal, as having CSAHS (i.e., an apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or greater, mostly with central sleep apneas), or as having obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS; i.e., an apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or greater, mostly with obstructive sleep apneas).

The prospective study included 121 consecutive patients between January 2018 and March 2020. Patients had a mean age of 56.8, and 88% were men.

Switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor ‘does not seem appropriate’

“CSAHS could be promoted by the use of ticagrelor, a relatively new drug that modifies the apneic threshold,” the study authors wrote. “Regarding underlying mechanisms, the most probable explanation seems to be increased chemosensitivity to hypercapnia by a direct P2Y12 inhibitory effect on the central nervous system.”

Doctors should not overestimate the severity of the adverse reaction or consider it the same way they do OSASH, they added.

Among patients with acute coronary syndrome in the PLATO study, ticagrelor, compared with clopidogrel, “significantly reduced the rate of death from vascular causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke,” Dr. Meurin and colleagues said. “Because in this study more than 9,000 patients received ticagrelor for 12 months, CSAHS (even if it seems frequent in our study) did not seem to impair the good efficacy/tolerance balance of the drug. Therefore, in asymptomatic CSAHS patients, switching from ticagrelor to another P2Y12 inhibitor does not seem appropriate.”

A recent analysis of data from randomized, controlled trials with ticagrelor did not find excess cases of sleep apnea with the drug. But an asymptomatic adverse event such as central sleep apnea “cannot emerge from a post hoc analysis,” Dr. Meurin and colleagues said.

The analysis of randomized trial data was conducted by Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, chairman of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and coauthors. It was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions in April 2020.

They “used the gold standard for medical evidence (randomized, placebo-controlled trials) and found 158 cases of sleep apnea reported, with absolutely no difference between ticagrelor and placebo,” Dr. Sabatine said in an interview. Their analysis examined clinically overt apnea, he noted.

“It is quite clear that when looking at large numbers in placebo-controlled trials, there is no excess,” Dr. Sabatine said. “Meurin et al. are examining a different outcome: the results of a lab test in what may be entirely asymptomatic patients.”

A randomized trial could confirm the association, he said.

“The association may be real, but also may be play of chance or confounded,” said Dr. Sabatine. “To convince the medical community, the next step would be for the investigators to do a randomized trial and test whether ticagrelor increases the risk of central sleep apnea.”

Dr. Meurin and the study coauthors had no disclosures. The analysis of randomized, controlled trial data by Dr. Sabatine and colleagues was funded by AstraZeneca, which distributes ticagrelor under the trade name Brilinta. Dr. Sabatine has been a consultant for AstraZeneca and received research grants through Brigham and Women’s Hospital from AstraZeneca. He has consulted for and received grants through the hospital from other companies as well. Dr. Jacobowitz had no relevant disclosures.

jremaly@mdedge.com

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

New light cast on type 2 MI aims to sharpen diagnosis, therapy

The hospital and postdischarge course of patients diagnosed with type 2 myocardial infarction, triggered when myocardial oxygen demand outstrips supply, differs in telling ways from those with the more common atherothrombotic type 1 MI, suggests a new registry analysis that aims to lift a cloud of confusion surrounding their management.

The observational study of more than 250,000 patients with either form of MI, said to be the largest of its kind, points to widespread unfamiliarity with distinctions between the two, and the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of misclassification. It suggests, in particular, that type 2 MI may be grossly underdiagnosed and undertreated.

The minority of patients with type 2 MI were more likely female and to have heart failure (HF), renal disease, valve disease, or atrial fibrillation, and less likely to have a lipid disorder, compared with those with type 1 MI. They were one-fifth as likely to be referred for coronary angiography and 20 times less likely to undergo revascularization.

Indeed, only about 2% of the type 2 cohort ultimately underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG). Yet the analysis suggests that cardiovascular risk climbs regardless of MI type and that in patients with type 2 MI, coronary revascularization might well cut the risk of death in half over the short term.

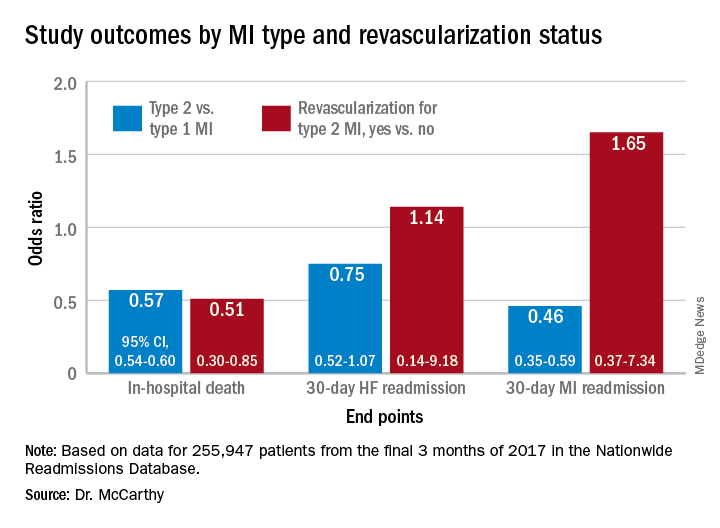

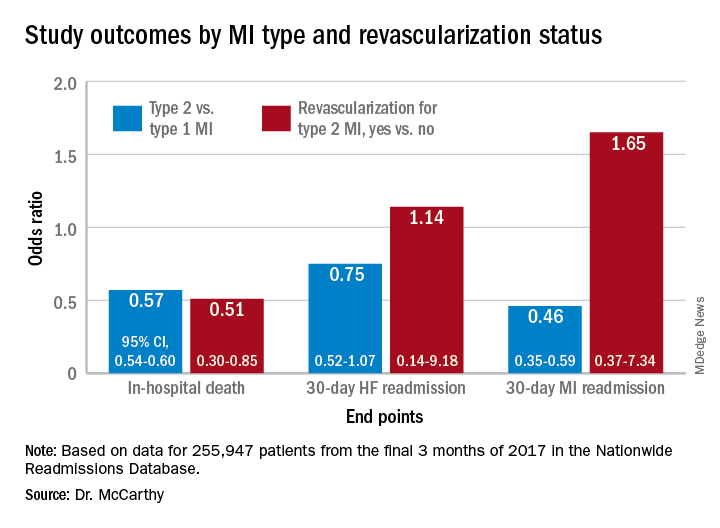

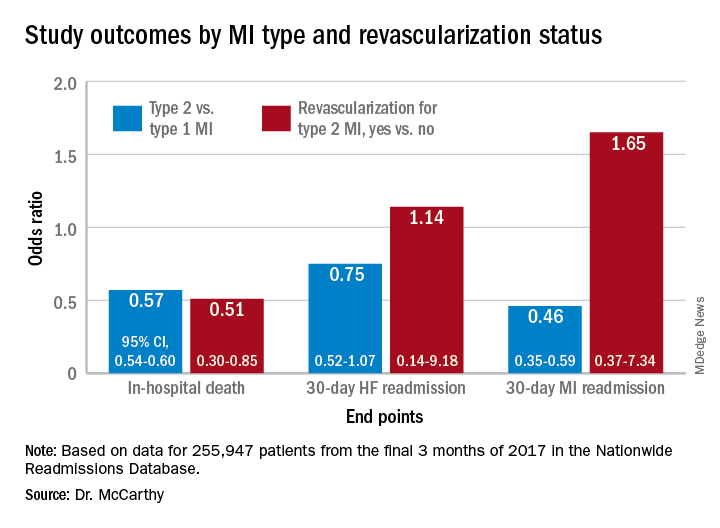

There were also disparities in clinical outcomes in the analysis, based on data from the final 3 months of 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which reportedly documents almost 60% of hospitalizations in the United States.

For example, those with type 1 or type 2 MI – as characterized in the then-current third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction and today’s UDMI-4 – were comparably at risk for both 30-day all-cause readmission and HF readmission. But type 2 patients were less likely to die in the hospital or be readmitted within 30 days for recurrent MI.

Revascularization uncertainty

Importantly, the study’s 3-month observation period immediately followed the debut of a code specifically for type 2 MI in the ICD-10-CM system.

Type 2 accounted for about 15% of MIs during that period, the percentage climbing sharply from the first to the third month. That suggests clinicians were still getting used to the code during the early weeks, “undercoding” for type-2 MI at first but less so after some experience, Cian P. McCarthy, MB, BCh, BAO, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“I can imagine that as people become more aware of the coding, using it more often, the proportion of type 2 MI relative to the total MI cases will probably be much higher,” said McCarthy, lead author on the study published online Feb. 15, 2021, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

What had been understood about type 2 MI came largely from single-center studies, he said. This “first national study of type-2 MI in the United States” sought to determine whether such findings are hospital specific or “representative of what people are doing nationally.”

The new analysis largely confirms that patients with type 2 MI are typically burdened with multiple comorbidities, Dr. McCarthy said, but also suggests that type 2 often was, and likely still is, incorrectly classified as type 1. So, it was “surprising” that they were rarely referred for angiography. “Only 1 in 50 received revascularization.”

Those diagnosed with type-2 MI were far less likely to receive coronary angiography (10.9% vs. 57.3%), PCI (1.7% vs. 38.5%), or CABG (0.4% vs. 7.8%) (P < .001 for all three differences), the report noted.

That, Dr. McCarthy said, “clearly shows that clinicians are uncertain about whether revascularization is beneficial” in type 2 MI.

Coding not in sync with UDMI

If there is confusion in practice about differentiating type 2 from type 1 MI, it likely has multiple sources, and one may be inconsistencies in how the UDMI and relevant ICD codes are applied in practice.

For example, the coding mandate is always to classify ST-segment elevation MI and non-STEMI as type 1, yet UDMI-4 itself states that a type 2 MI may be either STEMI or non-STEMI, noted Dr. McCarthy, as well as an editorial accompanying the report.

“It also can be difficult at times to distinguish type 2 MI from the diagnosis of myocardial injury,” both of which are partly defined by elevated cardiac troponin (cTn), adds the editorial, from Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Crucially, but potentially sometimes overlooked, a diagnosis of infarction requires evidence of ischemia along with the biomarker elevation, whereas myocardial injury is defined by raised cTn without evidence of ischemia. Yet there is no ICD-10-CM code for “nonischemic myocardial injury,” Dr. Thygesen and Dr. Jaffe observed.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” they wrote. “Unfortunately, although some have advocated using this code for myocardial injury, it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading” and thus worsen the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

In the current study, 84.6% of the cohort were classified with type 1 MI, 14.8% with type 2, and 0.6% with both types. Of those with type 1 MI, 22.1% had STEMI, 76.4% had non-STEMI with the remainder “unspecified.”

“I think the introduction of ICD codes for type-2 MI is helpful in that we can study type 2 MI more broadly, across institutions, and try and get a better sense of its outcomes and how these patients are treated,” Dr. McCarthy said. But the coding system’s deficiencies may often lead to misclassification of patients. Especially, patients with type 2 STEMI may be miscoded as having type-1 STEMI, and those with only myocardial injury may be miscoded as having type 2 MI.

Most type 2 MI is a complication

A profile of patients with type 2 MI may be helpful for making distinctions. The analysis showed that, compared with patients with type 1 MI, they were slightly but significantly older and more likely to have clinical depression, alcohol or other substance abuse disorder, and to be female. They also had more heart failure (27.9% vs. 10.9%), kidney disease (35.7% vs. 25.7%), atrial fibrillation (31% vs. 21%), and anemia (26% vs. 18.9%) (P < .001 for all differences).

Type 2 patients were less likely to have CV risk factors usually associated with plaque instability and atherothrombosis, including a history of smoking, dyslipidemia, MI, PCI, or CABG (P < .001 for all differences), the group noted.

Of the 37,765 patients with type 2 MI, 91% received the diagnosis as secondary to another condition, including sepsis in 24.5%, hypertension in 16.9%, arrhythmias in 6.1%, respiratory failure in 4.3%, and pneumonia in 2.8% of cases.

In multivariate analyses, patients with type 2 MI, compared with type 1, showed lower risks of in-hospital death and readmission for MI within 30 days. Their 30-day risks of readmission from any cause and from MI were similar.

In-hospital mortality was lower for patients with type 2 MI who underwent revascularization, compared with those who did not, “but they were a very select, small proportion of the patient group. I would say there are probably unmeasured confounders,” Dr. McCarthy said.

“There’s a real kind of equipoise, so I think we desperately need a trial to guide us on whether revascularization is beneficial.”

Dr. McCarthy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Thygesen disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jaffe disclosed serving as a consultant for Abbott, Roche, Siemens, Beckman-Coulter, Radiometer, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Brava, Quidel, Amgen, Novartis, and Medscape for educational activities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The hospital and postdischarge course of patients diagnosed with type 2 myocardial infarction, triggered when myocardial oxygen demand outstrips supply, differs in telling ways from those with the more common atherothrombotic type 1 MI, suggests a new registry analysis that aims to lift a cloud of confusion surrounding their management.

The observational study of more than 250,000 patients with either form of MI, said to be the largest of its kind, points to widespread unfamiliarity with distinctions between the two, and the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of misclassification. It suggests, in particular, that type 2 MI may be grossly underdiagnosed and undertreated.

The minority of patients with type 2 MI were more likely female and to have heart failure (HF), renal disease, valve disease, or atrial fibrillation, and less likely to have a lipid disorder, compared with those with type 1 MI. They were one-fifth as likely to be referred for coronary angiography and 20 times less likely to undergo revascularization.

Indeed, only about 2% of the type 2 cohort ultimately underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG). Yet the analysis suggests that cardiovascular risk climbs regardless of MI type and that in patients with type 2 MI, coronary revascularization might well cut the risk of death in half over the short term.

There were also disparities in clinical outcomes in the analysis, based on data from the final 3 months of 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which reportedly documents almost 60% of hospitalizations in the United States.

For example, those with type 1 or type 2 MI – as characterized in the then-current third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction and today’s UDMI-4 – were comparably at risk for both 30-day all-cause readmission and HF readmission. But type 2 patients were less likely to die in the hospital or be readmitted within 30 days for recurrent MI.

Revascularization uncertainty

Importantly, the study’s 3-month observation period immediately followed the debut of a code specifically for type 2 MI in the ICD-10-CM system.

Type 2 accounted for about 15% of MIs during that period, the percentage climbing sharply from the first to the third month. That suggests clinicians were still getting used to the code during the early weeks, “undercoding” for type-2 MI at first but less so after some experience, Cian P. McCarthy, MB, BCh, BAO, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“I can imagine that as people become more aware of the coding, using it more often, the proportion of type 2 MI relative to the total MI cases will probably be much higher,” said McCarthy, lead author on the study published online Feb. 15, 2021, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

What had been understood about type 2 MI came largely from single-center studies, he said. This “first national study of type-2 MI in the United States” sought to determine whether such findings are hospital specific or “representative of what people are doing nationally.”

The new analysis largely confirms that patients with type 2 MI are typically burdened with multiple comorbidities, Dr. McCarthy said, but also suggests that type 2 often was, and likely still is, incorrectly classified as type 1. So, it was “surprising” that they were rarely referred for angiography. “Only 1 in 50 received revascularization.”

Those diagnosed with type-2 MI were far less likely to receive coronary angiography (10.9% vs. 57.3%), PCI (1.7% vs. 38.5%), or CABG (0.4% vs. 7.8%) (P < .001 for all three differences), the report noted.

That, Dr. McCarthy said, “clearly shows that clinicians are uncertain about whether revascularization is beneficial” in type 2 MI.

Coding not in sync with UDMI

If there is confusion in practice about differentiating type 2 from type 1 MI, it likely has multiple sources, and one may be inconsistencies in how the UDMI and relevant ICD codes are applied in practice.

For example, the coding mandate is always to classify ST-segment elevation MI and non-STEMI as type 1, yet UDMI-4 itself states that a type 2 MI may be either STEMI or non-STEMI, noted Dr. McCarthy, as well as an editorial accompanying the report.

“It also can be difficult at times to distinguish type 2 MI from the diagnosis of myocardial injury,” both of which are partly defined by elevated cardiac troponin (cTn), adds the editorial, from Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Crucially, but potentially sometimes overlooked, a diagnosis of infarction requires evidence of ischemia along with the biomarker elevation, whereas myocardial injury is defined by raised cTn without evidence of ischemia. Yet there is no ICD-10-CM code for “nonischemic myocardial injury,” Dr. Thygesen and Dr. Jaffe observed.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” they wrote. “Unfortunately, although some have advocated using this code for myocardial injury, it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading” and thus worsen the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

In the current study, 84.6% of the cohort were classified with type 1 MI, 14.8% with type 2, and 0.6% with both types. Of those with type 1 MI, 22.1% had STEMI, 76.4% had non-STEMI with the remainder “unspecified.”

“I think the introduction of ICD codes for type-2 MI is helpful in that we can study type 2 MI more broadly, across institutions, and try and get a better sense of its outcomes and how these patients are treated,” Dr. McCarthy said. But the coding system’s deficiencies may often lead to misclassification of patients. Especially, patients with type 2 STEMI may be miscoded as having type-1 STEMI, and those with only myocardial injury may be miscoded as having type 2 MI.

Most type 2 MI is a complication

A profile of patients with type 2 MI may be helpful for making distinctions. The analysis showed that, compared with patients with type 1 MI, they were slightly but significantly older and more likely to have clinical depression, alcohol or other substance abuse disorder, and to be female. They also had more heart failure (27.9% vs. 10.9%), kidney disease (35.7% vs. 25.7%), atrial fibrillation (31% vs. 21%), and anemia (26% vs. 18.9%) (P < .001 for all differences).

Type 2 patients were less likely to have CV risk factors usually associated with plaque instability and atherothrombosis, including a history of smoking, dyslipidemia, MI, PCI, or CABG (P < .001 for all differences), the group noted.

Of the 37,765 patients with type 2 MI, 91% received the diagnosis as secondary to another condition, including sepsis in 24.5%, hypertension in 16.9%, arrhythmias in 6.1%, respiratory failure in 4.3%, and pneumonia in 2.8% of cases.

In multivariate analyses, patients with type 2 MI, compared with type 1, showed lower risks of in-hospital death and readmission for MI within 30 days. Their 30-day risks of readmission from any cause and from MI were similar.

In-hospital mortality was lower for patients with type 2 MI who underwent revascularization, compared with those who did not, “but they were a very select, small proportion of the patient group. I would say there are probably unmeasured confounders,” Dr. McCarthy said.

“There’s a real kind of equipoise, so I think we desperately need a trial to guide us on whether revascularization is beneficial.”

Dr. McCarthy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Thygesen disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jaffe disclosed serving as a consultant for Abbott, Roche, Siemens, Beckman-Coulter, Radiometer, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Brava, Quidel, Amgen, Novartis, and Medscape for educational activities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The hospital and postdischarge course of patients diagnosed with type 2 myocardial infarction, triggered when myocardial oxygen demand outstrips supply, differs in telling ways from those with the more common atherothrombotic type 1 MI, suggests a new registry analysis that aims to lift a cloud of confusion surrounding their management.

The observational study of more than 250,000 patients with either form of MI, said to be the largest of its kind, points to widespread unfamiliarity with distinctions between the two, and the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of misclassification. It suggests, in particular, that type 2 MI may be grossly underdiagnosed and undertreated.

The minority of patients with type 2 MI were more likely female and to have heart failure (HF), renal disease, valve disease, or atrial fibrillation, and less likely to have a lipid disorder, compared with those with type 1 MI. They were one-fifth as likely to be referred for coronary angiography and 20 times less likely to undergo revascularization.

Indeed, only about 2% of the type 2 cohort ultimately underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG). Yet the analysis suggests that cardiovascular risk climbs regardless of MI type and that in patients with type 2 MI, coronary revascularization might well cut the risk of death in half over the short term.

There were also disparities in clinical outcomes in the analysis, based on data from the final 3 months of 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which reportedly documents almost 60% of hospitalizations in the United States.

For example, those with type 1 or type 2 MI – as characterized in the then-current third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction and today’s UDMI-4 – were comparably at risk for both 30-day all-cause readmission and HF readmission. But type 2 patients were less likely to die in the hospital or be readmitted within 30 days for recurrent MI.

Revascularization uncertainty

Importantly, the study’s 3-month observation period immediately followed the debut of a code specifically for type 2 MI in the ICD-10-CM system.

Type 2 accounted for about 15% of MIs during that period, the percentage climbing sharply from the first to the third month. That suggests clinicians were still getting used to the code during the early weeks, “undercoding” for type-2 MI at first but less so after some experience, Cian P. McCarthy, MB, BCh, BAO, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“I can imagine that as people become more aware of the coding, using it more often, the proportion of type 2 MI relative to the total MI cases will probably be much higher,” said McCarthy, lead author on the study published online Feb. 15, 2021, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

What had been understood about type 2 MI came largely from single-center studies, he said. This “first national study of type-2 MI in the United States” sought to determine whether such findings are hospital specific or “representative of what people are doing nationally.”

The new analysis largely confirms that patients with type 2 MI are typically burdened with multiple comorbidities, Dr. McCarthy said, but also suggests that type 2 often was, and likely still is, incorrectly classified as type 1. So, it was “surprising” that they were rarely referred for angiography. “Only 1 in 50 received revascularization.”

Those diagnosed with type-2 MI were far less likely to receive coronary angiography (10.9% vs. 57.3%), PCI (1.7% vs. 38.5%), or CABG (0.4% vs. 7.8%) (P < .001 for all three differences), the report noted.

That, Dr. McCarthy said, “clearly shows that clinicians are uncertain about whether revascularization is beneficial” in type 2 MI.

Coding not in sync with UDMI

If there is confusion in practice about differentiating type 2 from type 1 MI, it likely has multiple sources, and one may be inconsistencies in how the UDMI and relevant ICD codes are applied in practice.

For example, the coding mandate is always to classify ST-segment elevation MI and non-STEMI as type 1, yet UDMI-4 itself states that a type 2 MI may be either STEMI or non-STEMI, noted Dr. McCarthy, as well as an editorial accompanying the report.

“It also can be difficult at times to distinguish type 2 MI from the diagnosis of myocardial injury,” both of which are partly defined by elevated cardiac troponin (cTn), adds the editorial, from Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Crucially, but potentially sometimes overlooked, a diagnosis of infarction requires evidence of ischemia along with the biomarker elevation, whereas myocardial injury is defined by raised cTn without evidence of ischemia. Yet there is no ICD-10-CM code for “nonischemic myocardial injury,” Dr. Thygesen and Dr. Jaffe observed.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” they wrote. “Unfortunately, although some have advocated using this code for myocardial injury, it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading” and thus worsen the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

In the current study, 84.6% of the cohort were classified with type 1 MI, 14.8% with type 2, and 0.6% with both types. Of those with type 1 MI, 22.1% had STEMI, 76.4% had non-STEMI with the remainder “unspecified.”

“I think the introduction of ICD codes for type-2 MI is helpful in that we can study type 2 MI more broadly, across institutions, and try and get a better sense of its outcomes and how these patients are treated,” Dr. McCarthy said. But the coding system’s deficiencies may often lead to misclassification of patients. Especially, patients with type 2 STEMI may be miscoded as having type-1 STEMI, and those with only myocardial injury may be miscoded as having type 2 MI.

Most type 2 MI is a complication

A profile of patients with type 2 MI may be helpful for making distinctions. The analysis showed that, compared with patients with type 1 MI, they were slightly but significantly older and more likely to have clinical depression, alcohol or other substance abuse disorder, and to be female. They also had more heart failure (27.9% vs. 10.9%), kidney disease (35.7% vs. 25.7%), atrial fibrillation (31% vs. 21%), and anemia (26% vs. 18.9%) (P < .001 for all differences).

Type 2 patients were less likely to have CV risk factors usually associated with plaque instability and atherothrombosis, including a history of smoking, dyslipidemia, MI, PCI, or CABG (P < .001 for all differences), the group noted.

Of the 37,765 patients with type 2 MI, 91% received the diagnosis as secondary to another condition, including sepsis in 24.5%, hypertension in 16.9%, arrhythmias in 6.1%, respiratory failure in 4.3%, and pneumonia in 2.8% of cases.

In multivariate analyses, patients with type 2 MI, compared with type 1, showed lower risks of in-hospital death and readmission for MI within 30 days. Their 30-day risks of readmission from any cause and from MI were similar.

In-hospital mortality was lower for patients with type 2 MI who underwent revascularization, compared with those who did not, “but they were a very select, small proportion of the patient group. I would say there are probably unmeasured confounders,” Dr. McCarthy said.

“There’s a real kind of equipoise, so I think we desperately need a trial to guide us on whether revascularization is beneficial.”

Dr. McCarthy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Thygesen disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jaffe disclosed serving as a consultant for Abbott, Roche, Siemens, Beckman-Coulter, Radiometer, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Brava, Quidel, Amgen, Novartis, and Medscape for educational activities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women and ACS: Focus on typical symptoms to improve outcomes

There are some differences in how women relative to men report symptoms of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), but they should not be permitted to get in the way of prompt diagnosis and treatment, according to an expert review at the virtual Going Back to the Heart of Cardiology meeting.

“We need to get away from the idea that symptoms of a myocardial infarction in women are atypical, because women are also having typical symptoms,” said Martha Gulati, MD, chief of cardiology at the University of Arizona, Phoenix.

Sexes share key symptoms, but not treatment

Although “women are more likely to report additional symptoms,” chest pain “is pretty much equal between men and women” presenting with an ACS, according to Dr. Gulati.

There are several studies that have shown this, including the Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI patients (VIRGO). In VIRGO, which looked at ACS symptom presentation in younger patients (ages 18-55 years), 87.0% of women versus 89.5% of men presented with chest pain defined as pain, pressure, tightness, or discomfort.

Even among those who recognize that more women die of cardiovascular disease (CVD) disease than any other cause, nothing seems to erase the bias that women in an ED are less likely than men to be having a heart attack. About 60 million women in the United States have CVD, so no threat imposes a higher toll in morbidity and mortality.

In comparison, there are only about 3.5 million women with breast cancer. Even though this is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in women, it is dwarfed by CVD, according to statistics cited by Dr. Gulati. Yet, the data show women get inferior care by guideline-based standards.

“After a myocardial infarction, women relative to men are less likely to get aspirin or beta-blockers within 24 hours, they are less likely to undergo any type of invasive procedure, and they are less likely to meet the door-to-balloon time or receive any reperfusion therapy,” Dr. Gulati said. After a CVD event, “the only thing women do better is to die.”

Additional symptoms may muddy the diagnostic waters

In the setting of ACS, the problem is not that women fail to report symptoms that should lead clinicians to consider CVD, but that they report additional symptoms. For the clinician less inclined to consider CVD in women, particularly younger women, there is a greater risk of going down the wrong diagnostic pathway.

In other words, women report symptoms consistent with CVD, “but it is a question of whether we are hearing it,” Dr. Gulati said.

In the VIRGO study, 61.9% of women versus 54.8% of men (P < .001) presented three or more symptoms in addition to chest pain, such as epigastric symptoms, discomfort in the arms or neck, or palpitations. Women were more likely than men to attribute the symptoms to stress or anxiety (20.9% vs. 11.8%; P < .001), while less likely to consider them a result of muscle pain (15.4% vs. 21.2%; P = .029).

There are other gender differences for ACS. For example, women are more likely than men to presented ischemia without obstruction, but Dr. Gulati emphasized that lack of obstruction is not a reason to dismiss the potential for an underlying CV cause.

‘Yentl syndrome’ persists

“Women should not need to present exactly like men to be taken seriously,” she said, describing the “Yentl syndrome,” which now has its own Wikipedia page. A cardiovascular version of this syndrome was first described 30 years ago. Based on a movie of a woman who cross dresses in order to be allowed to undertake Jewish studies, the term captures the societal failure to adapt care for women who do not present disease the same way that men do.

Overall, inadequate urgency to pursue potential symptoms of ACS in women is just another manifestation of the “bikini approach to women’s health,” according to Dr. Gulati. This describes the focus on the breast and reproductive system to the exclusion or other organs and anatomy. Dr. Gulati speculated that this might be the reason that clinicians have failed to apply ACS guidelines to women with the same rigor that they apply to men.

This is hardly a new issue. Calls for improving cardiovascular care in women have been increasing in volume for more than past 20 years, but the issue has proven persistent, according to Dr. Gulati. As an example, she noted that the same types of gaps in care and in outcome reported in a 2008 registry study had not much changed in an article published 8 years later.

The solution is not complex, according to Dr. Gulati. In the ED, guideline-directed diagnostic tests should be offered to any man or woman, including younger women, who present with chest pain, ignoring gender bias that threatens misinterpretation of patient history and symptoms. Once CVD is diagnosed as promptly in women as it is in men, guideline-directed intervention would be expected to reduce the gender gap in outcomes.

“By applying standardized protocols, it will help us to the same for women as we do for men,” Dr. Gulati said.

The meeting was sponsored by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

There are some differences in how women relative to men report symptoms of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), but they should not be permitted to get in the way of prompt diagnosis and treatment, according to an expert review at the virtual Going Back to the Heart of Cardiology meeting.

“We need to get away from the idea that symptoms of a myocardial infarction in women are atypical, because women are also having typical symptoms,” said Martha Gulati, MD, chief of cardiology at the University of Arizona, Phoenix.

Sexes share key symptoms, but not treatment

Although “women are more likely to report additional symptoms,” chest pain “is pretty much equal between men and women” presenting with an ACS, according to Dr. Gulati.

There are several studies that have shown this, including the Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI patients (VIRGO). In VIRGO, which looked at ACS symptom presentation in younger patients (ages 18-55 years), 87.0% of women versus 89.5% of men presented with chest pain defined as pain, pressure, tightness, or discomfort.

Even among those who recognize that more women die of cardiovascular disease (CVD) disease than any other cause, nothing seems to erase the bias that women in an ED are less likely than men to be having a heart attack. About 60 million women in the United States have CVD, so no threat imposes a higher toll in morbidity and mortality.

In comparison, there are only about 3.5 million women with breast cancer. Even though this is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in women, it is dwarfed by CVD, according to statistics cited by Dr. Gulati. Yet, the data show women get inferior care by guideline-based standards.

“After a myocardial infarction, women relative to men are less likely to get aspirin or beta-blockers within 24 hours, they are less likely to undergo any type of invasive procedure, and they are less likely to meet the door-to-balloon time or receive any reperfusion therapy,” Dr. Gulati said. After a CVD event, “the only thing women do better is to die.”

Additional symptoms may muddy the diagnostic waters

In the setting of ACS, the problem is not that women fail to report symptoms that should lead clinicians to consider CVD, but that they report additional symptoms. For the clinician less inclined to consider CVD in women, particularly younger women, there is a greater risk of going down the wrong diagnostic pathway.

In other words, women report symptoms consistent with CVD, “but it is a question of whether we are hearing it,” Dr. Gulati said.

In the VIRGO study, 61.9% of women versus 54.8% of men (P < .001) presented three or more symptoms in addition to chest pain, such as epigastric symptoms, discomfort in the arms or neck, or palpitations. Women were more likely than men to attribute the symptoms to stress or anxiety (20.9% vs. 11.8%; P < .001), while less likely to consider them a result of muscle pain (15.4% vs. 21.2%; P = .029).

There are other gender differences for ACS. For example, women are more likely than men to presented ischemia without obstruction, but Dr. Gulati emphasized that lack of obstruction is not a reason to dismiss the potential for an underlying CV cause.

‘Yentl syndrome’ persists

“Women should not need to present exactly like men to be taken seriously,” she said, describing the “Yentl syndrome,” which now has its own Wikipedia page. A cardiovascular version of this syndrome was first described 30 years ago. Based on a movie of a woman who cross dresses in order to be allowed to undertake Jewish studies, the term captures the societal failure to adapt care for women who do not present disease the same way that men do.

Overall, inadequate urgency to pursue potential symptoms of ACS in women is just another manifestation of the “bikini approach to women’s health,” according to Dr. Gulati. This describes the focus on the breast and reproductive system to the exclusion or other organs and anatomy. Dr. Gulati speculated that this might be the reason that clinicians have failed to apply ACS guidelines to women with the same rigor that they apply to men.

This is hardly a new issue. Calls for improving cardiovascular care in women have been increasing in volume for more than past 20 years, but the issue has proven persistent, according to Dr. Gulati. As an example, she noted that the same types of gaps in care and in outcome reported in a 2008 registry study had not much changed in an article published 8 years later.

The solution is not complex, according to Dr. Gulati. In the ED, guideline-directed diagnostic tests should be offered to any man or woman, including younger women, who present with chest pain, ignoring gender bias that threatens misinterpretation of patient history and symptoms. Once CVD is diagnosed as promptly in women as it is in men, guideline-directed intervention would be expected to reduce the gender gap in outcomes.

“By applying standardized protocols, it will help us to the same for women as we do for men,” Dr. Gulati said.

The meeting was sponsored by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

There are some differences in how women relative to men report symptoms of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), but they should not be permitted to get in the way of prompt diagnosis and treatment, according to an expert review at the virtual Going Back to the Heart of Cardiology meeting.

“We need to get away from the idea that symptoms of a myocardial infarction in women are atypical, because women are also having typical symptoms,” said Martha Gulati, MD, chief of cardiology at the University of Arizona, Phoenix.

Sexes share key symptoms, but not treatment

Although “women are more likely to report additional symptoms,” chest pain “is pretty much equal between men and women” presenting with an ACS, according to Dr. Gulati.

There are several studies that have shown this, including the Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI patients (VIRGO). In VIRGO, which looked at ACS symptom presentation in younger patients (ages 18-55 years), 87.0% of women versus 89.5% of men presented with chest pain defined as pain, pressure, tightness, or discomfort.

Even among those who recognize that more women die of cardiovascular disease (CVD) disease than any other cause, nothing seems to erase the bias that women in an ED are less likely than men to be having a heart attack. About 60 million women in the United States have CVD, so no threat imposes a higher toll in morbidity and mortality.

In comparison, there are only about 3.5 million women with breast cancer. Even though this is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in women, it is dwarfed by CVD, according to statistics cited by Dr. Gulati. Yet, the data show women get inferior care by guideline-based standards.

“After a myocardial infarction, women relative to men are less likely to get aspirin or beta-blockers within 24 hours, they are less likely to undergo any type of invasive procedure, and they are less likely to meet the door-to-balloon time or receive any reperfusion therapy,” Dr. Gulati said. After a CVD event, “the only thing women do better is to die.”

Additional symptoms may muddy the diagnostic waters

In the setting of ACS, the problem is not that women fail to report symptoms that should lead clinicians to consider CVD, but that they report additional symptoms. For the clinician less inclined to consider CVD in women, particularly younger women, there is a greater risk of going down the wrong diagnostic pathway.

In other words, women report symptoms consistent with CVD, “but it is a question of whether we are hearing it,” Dr. Gulati said.

In the VIRGO study, 61.9% of women versus 54.8% of men (P < .001) presented three or more symptoms in addition to chest pain, such as epigastric symptoms, discomfort in the arms or neck, or palpitations. Women were more likely than men to attribute the symptoms to stress or anxiety (20.9% vs. 11.8%; P < .001), while less likely to consider them a result of muscle pain (15.4% vs. 21.2%; P = .029).

There are other gender differences for ACS. For example, women are more likely than men to presented ischemia without obstruction, but Dr. Gulati emphasized that lack of obstruction is not a reason to dismiss the potential for an underlying CV cause.

‘Yentl syndrome’ persists

“Women should not need to present exactly like men to be taken seriously,” she said, describing the “Yentl syndrome,” which now has its own Wikipedia page. A cardiovascular version of this syndrome was first described 30 years ago. Based on a movie of a woman who cross dresses in order to be allowed to undertake Jewish studies, the term captures the societal failure to adapt care for women who do not present disease the same way that men do.

Overall, inadequate urgency to pursue potential symptoms of ACS in women is just another manifestation of the “bikini approach to women’s health,” according to Dr. Gulati. This describes the focus on the breast and reproductive system to the exclusion or other organs and anatomy. Dr. Gulati speculated that this might be the reason that clinicians have failed to apply ACS guidelines to women with the same rigor that they apply to men.

This is hardly a new issue. Calls for improving cardiovascular care in women have been increasing in volume for more than past 20 years, but the issue has proven persistent, according to Dr. Gulati. As an example, she noted that the same types of gaps in care and in outcome reported in a 2008 registry study had not much changed in an article published 8 years later.

The solution is not complex, according to Dr. Gulati. In the ED, guideline-directed diagnostic tests should be offered to any man or woman, including younger women, who present with chest pain, ignoring gender bias that threatens misinterpretation of patient history and symptoms. Once CVD is diagnosed as promptly in women as it is in men, guideline-directed intervention would be expected to reduce the gender gap in outcomes.

“By applying standardized protocols, it will help us to the same for women as we do for men,” Dr. Gulati said.

The meeting was sponsored by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM GOING BACK TO THE HEART OF CARDIOLOGY

ColCORONA: More questions than answers for colchicine in COVID-19

Science by press release and preprint has cooled clinician enthusiasm for the use of colchicine in nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19, despite a pressing need for early treatments.

As previously reported by this news organization, a Jan. 22 press release announced that the massive ColCORONA study missed its primary endpoint of hospitalization or death among 4,488 newly diagnosed patients at increased risk for hospitalization.

But it also touted that use of the anti-inflammatory drug significantly reduced the primary endpoint in 4,159 of those patients with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID and led to reductions of 25%, 50%, and 44%, respectively, for hospitalizations, ventilations, and death.

Lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, director of the Montreal Heart Institute Research Centre, deemed the findings a “medical breakthrough.”

When the preprint released a few days later, however, newly revealed confidence intervals showed colchicine did not meaningfully reduce the need for mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-1.07) or death alone (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.19-1.66).

Further, the significant benefit on the primary outcome came at the cost of a fivefold increase in pulmonary embolism (11 vs. 2; P = .01), which was not mentioned in the press release.

“Whether this represents a real phenomenon or simply the play of chance is not known,” Dr. Tardif and colleagues noted later in the preprint.

“I read the preprint on colchicine and I have so many questions,” Aaron E. Glatt, MD, spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Hewlett, N.Y., said in an interview. “I’ve been burned too many times with COVID and prefer to see better data.

“People sometimes say if you wait for perfect data, people are going to die,” he said. “Yeah, but we have no idea if people are going to die from getting this drug more than not getting it. That’s what concerns me. How many pulmonary emboli are going to be fatal versus the slight benefit that the study showed?”

The pushback to the non–peer-reviewed data on social media and via emails was so strong that Dr. Tardif posted a nearly 2,000-word letter responding to the many questions at play.

Chief among them was why the trial, originally planned for 6,000 patients, was stopped early by the investigators without consultation with the data safety monitoring board (DSMB).

The explanation in the letter that logistical issues like running the study call center, budget constraints, and a perceived need to quickly communicate the results left some calling foul that the study wasn’t allowed to finish and come to a more definitive conclusion.

“I can be a little bit sympathetic to their cause but at the same time the DSMB should have said no,” said David Boulware, MD, MPH, who led a recent hydroxychloroquine trial in COVID-19. “The problem is we’re sort of left in limbo, where some people kind of believe it and some say it’s not really a thing. So it’s not really moving the needle, as far as guidelines go.”

Indeed, a Twitter poll by cardiologist James Januzzi Jr., MD, captured the uncertainty, with 28% of respondents saying the trial was “neutral,” 58% saying “maybe but meh,” and 14% saying “colchicine for all.”

Another poll cheekily asked whether ColCORONA was the Gamestop/Reddit equivalent of COVID.

“The press release really didn’t help things because it very much oversold the effect. That, I think, poisoned the well,” said Dr. Boulware, professor of medicine in infectious diseases at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“The question I’m left with is not whether colchicine works, but who does it work in,” he said. “That’s really the fundamental question because it does seem that there are probably high-risk groups in their trial and others where they benefit, whereas other groups don’t benefit. In the subgroup analysis, there was absolutely no beneficial effect in women.”

According to the authors, the number needed to treat to prevent one death or hospitalization was 71 overall, but 29 for patients with diabetes, 31 for those aged 70 years and older, 53 for patients with respiratory disease, and 25 for those with coronary disease or heart failure.

Men are at higher risk overall for poor outcomes. But “the authors didn’t present a multivariable analysis, so it is unclear if another factor, such as a differential prevalence of smoking or cardiovascular risk factors, contributed to the differential benefit,” Rachel Bender Ignacio, MD, MPH, infectious disease specialist, University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Importantly, in this pragmatic study, duration and severity of symptoms were not reported, observed Dr. Bender Ignacio, who is also a STOP-COVID-2 investigator. “We don’t yet have data as to whether colchicine shortens duration or severity of symptoms or prevents long COVID, so we need more data on that.”

The overall risk for serious adverse events was lower in the colchicine group, but the difference in pulmonary embolism (PE) was striking, she said. This could be caused by a real biologic effect, or it’s possible that persons with shortness of breath and hypoxia, without evident viral pneumonia on chest x-ray after a positive COVID-19 test, were more likely to receive a CT-PE study.

The press release also failed to include information, later noted in the preprint, that the MHI has submitted two patents related to colchicine: “Methods of treating a coronavirus infection using colchicine” and “Early administration of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction.”

Reached for clarification, MHI communications adviser Camille Turbide said in an interview that the first patent “simply refers to the novel concept of preventing complications of COVID-19, such as admission to the hospital, with colchicine as tested in the ColCORONA study.”

The second patent, she said, refers to the “novel concept that administering colchicine early after a major adverse cardiovascular event is better than waiting several days,” as supported by the COLCOT study, which Dr. Tardif also led.

The patents are being reviewed by authorities and “Dr. Tardif has waived his rights in these patents and does not stand to benefit financially at all if colchicine becomes used as a treatment for COVID-19,” Ms. Turbide said.

Dr. Tardif did not respond to interview requests for this story. Dr. Glatt said conflicts of interest must be assessed and are “something that is of great concern in any scientific study.”

Cardiologist Steve Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic said in an interview that, “despite the negative results, the study does suggest that colchicine might have a benefit and should be studied in future trials. These findings are not sufficient evidence to suggest use of the drug in patients infected with COVID-19.”

He noted that adverse effects like diarrhea were expected but that the excess PE was unexpected and needs greater clarification.

“Stopping the trial for administrative reasons is puzzling and undermined the ability of the trial to give a reliable answer,” Dr. Nissen said. “This is a reasonable pilot study that should be viewed as hypothesis generating but inconclusive.”

Several sources said a new trial is unlikely, particularly given the cost and 28 trials already evaluating colchicine. Among these are RECOVERY and COLCOVID, testing whether colchicine can reduce the duration of hospitalization or death in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Because there are so many trials ongoing right now, including for antivirals and other immunomodulators, it’s important that, if colchicine comes to routine clinical use, it provides access to treatment for those not able or willing to access clinical trials, rather than impeding clinical trial enrollment, Dr. Bender Ignacio suggested.

“We have already learned the lesson in the pandemic that early adoption of potentially promising therapies can negatively impact our ability to study and develop other promising treatments,” she said.

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais, and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators. Dr. Glatt reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Boulware reported receiving $18 in food and beverages from Gilead Sciences in 2018.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Science by press release and preprint has cooled clinician enthusiasm for the use of colchicine in nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19, despite a pressing need for early treatments.

As previously reported by this news organization, a Jan. 22 press release announced that the massive ColCORONA study missed its primary endpoint of hospitalization or death among 4,488 newly diagnosed patients at increased risk for hospitalization.

But it also touted that use of the anti-inflammatory drug significantly reduced the primary endpoint in 4,159 of those patients with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID and led to reductions of 25%, 50%, and 44%, respectively, for hospitalizations, ventilations, and death.

Lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, director of the Montreal Heart Institute Research Centre, deemed the findings a “medical breakthrough.”

When the preprint released a few days later, however, newly revealed confidence intervals showed colchicine did not meaningfully reduce the need for mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-1.07) or death alone (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.19-1.66).

Further, the significant benefit on the primary outcome came at the cost of a fivefold increase in pulmonary embolism (11 vs. 2; P = .01), which was not mentioned in the press release.

“Whether this represents a real phenomenon or simply the play of chance is not known,” Dr. Tardif and colleagues noted later in the preprint.

“I read the preprint on colchicine and I have so many questions,” Aaron E. Glatt, MD, spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Hewlett, N.Y., said in an interview. “I’ve been burned too many times with COVID and prefer to see better data.

“People sometimes say if you wait for perfect data, people are going to die,” he said. “Yeah, but we have no idea if people are going to die from getting this drug more than not getting it. That’s what concerns me. How many pulmonary emboli are going to be fatal versus the slight benefit that the study showed?”

The pushback to the non–peer-reviewed data on social media and via emails was so strong that Dr. Tardif posted a nearly 2,000-word letter responding to the many questions at play.

Chief among them was why the trial, originally planned for 6,000 patients, was stopped early by the investigators without consultation with the data safety monitoring board (DSMB).

The explanation in the letter that logistical issues like running the study call center, budget constraints, and a perceived need to quickly communicate the results left some calling foul that the study wasn’t allowed to finish and come to a more definitive conclusion.

“I can be a little bit sympathetic to their cause but at the same time the DSMB should have said no,” said David Boulware, MD, MPH, who led a recent hydroxychloroquine trial in COVID-19. “The problem is we’re sort of left in limbo, where some people kind of believe it and some say it’s not really a thing. So it’s not really moving the needle, as far as guidelines go.”

Indeed, a Twitter poll by cardiologist James Januzzi Jr., MD, captured the uncertainty, with 28% of respondents saying the trial was “neutral,” 58% saying “maybe but meh,” and 14% saying “colchicine for all.”

Another poll cheekily asked whether ColCORONA was the Gamestop/Reddit equivalent of COVID.

“The press release really didn’t help things because it very much oversold the effect. That, I think, poisoned the well,” said Dr. Boulware, professor of medicine in infectious diseases at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“The question I’m left with is not whether colchicine works, but who does it work in,” he said. “That’s really the fundamental question because it does seem that there are probably high-risk groups in their trial and others where they benefit, whereas other groups don’t benefit. In the subgroup analysis, there was absolutely no beneficial effect in women.”

According to the authors, the number needed to treat to prevent one death or hospitalization was 71 overall, but 29 for patients with diabetes, 31 for those aged 70 years and older, 53 for patients with respiratory disease, and 25 for those with coronary disease or heart failure.

Men are at higher risk overall for poor outcomes. But “the authors didn’t present a multivariable analysis, so it is unclear if another factor, such as a differential prevalence of smoking or cardiovascular risk factors, contributed to the differential benefit,” Rachel Bender Ignacio, MD, MPH, infectious disease specialist, University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Importantly, in this pragmatic study, duration and severity of symptoms were not reported, observed Dr. Bender Ignacio, who is also a STOP-COVID-2 investigator. “We don’t yet have data as to whether colchicine shortens duration or severity of symptoms or prevents long COVID, so we need more data on that.”

The overall risk for serious adverse events was lower in the colchicine group, but the difference in pulmonary embolism (PE) was striking, she said. This could be caused by a real biologic effect, or it’s possible that persons with shortness of breath and hypoxia, without evident viral pneumonia on chest x-ray after a positive COVID-19 test, were more likely to receive a CT-PE study.

The press release also failed to include information, later noted in the preprint, that the MHI has submitted two patents related to colchicine: “Methods of treating a coronavirus infection using colchicine” and “Early administration of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction.”

Reached for clarification, MHI communications adviser Camille Turbide said in an interview that the first patent “simply refers to the novel concept of preventing complications of COVID-19, such as admission to the hospital, with colchicine as tested in the ColCORONA study.”

The second patent, she said, refers to the “novel concept that administering colchicine early after a major adverse cardiovascular event is better than waiting several days,” as supported by the COLCOT study, which Dr. Tardif also led.

The patents are being reviewed by authorities and “Dr. Tardif has waived his rights in these patents and does not stand to benefit financially at all if colchicine becomes used as a treatment for COVID-19,” Ms. Turbide said.

Dr. Tardif did not respond to interview requests for this story. Dr. Glatt said conflicts of interest must be assessed and are “something that is of great concern in any scientific study.”

Cardiologist Steve Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic said in an interview that, “despite the negative results, the study does suggest that colchicine might have a benefit and should be studied in future trials. These findings are not sufficient evidence to suggest use of the drug in patients infected with COVID-19.”

He noted that adverse effects like diarrhea were expected but that the excess PE was unexpected and needs greater clarification.

“Stopping the trial for administrative reasons is puzzling and undermined the ability of the trial to give a reliable answer,” Dr. Nissen said. “This is a reasonable pilot study that should be viewed as hypothesis generating but inconclusive.”

Several sources said a new trial is unlikely, particularly given the cost and 28 trials already evaluating colchicine. Among these are RECOVERY and COLCOVID, testing whether colchicine can reduce the duration of hospitalization or death in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Because there are so many trials ongoing right now, including for antivirals and other immunomodulators, it’s important that, if colchicine comes to routine clinical use, it provides access to treatment for those not able or willing to access clinical trials, rather than impeding clinical trial enrollment, Dr. Bender Ignacio suggested.

“We have already learned the lesson in the pandemic that early adoption of potentially promising therapies can negatively impact our ability to study and develop other promising treatments,” she said.

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais, and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators. Dr. Glatt reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Boulware reported receiving $18 in food and beverages from Gilead Sciences in 2018.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Science by press release and preprint has cooled clinician enthusiasm for the use of colchicine in nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19, despite a pressing need for early treatments.

As previously reported by this news organization, a Jan. 22 press release announced that the massive ColCORONA study missed its primary endpoint of hospitalization or death among 4,488 newly diagnosed patients at increased risk for hospitalization.

But it also touted that use of the anti-inflammatory drug significantly reduced the primary endpoint in 4,159 of those patients with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID and led to reductions of 25%, 50%, and 44%, respectively, for hospitalizations, ventilations, and death.

Lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, director of the Montreal Heart Institute Research Centre, deemed the findings a “medical breakthrough.”

When the preprint released a few days later, however, newly revealed confidence intervals showed colchicine did not meaningfully reduce the need for mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-1.07) or death alone (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.19-1.66).

Further, the significant benefit on the primary outcome came at the cost of a fivefold increase in pulmonary embolism (11 vs. 2; P = .01), which was not mentioned in the press release.

“Whether this represents a real phenomenon or simply the play of chance is not known,” Dr. Tardif and colleagues noted later in the preprint.