User login

What’s the future of telehealth? It’s ‘complicated’

pre-AAD meeting.

“We have seen large numbers of children struggle with access to school and access to health care because of lack of access to devices, challenges of broadband Internet access, culture, language, and educational barriers – just having trouble being comfortable with this technology,” said Natalie Pageler, MD, a pediatric intensivist and chief medical information officer at Stanford Children’s Health, Palo Alto, Calif.

“There are also privacy concerns, especially in situations where there are multiple families within a household. Finally, it’s important to remember that policy and reimbursement issues may have a significant effect on some of the socioeconomic barriers,” she added. “For example, many of our families who don’t have access to audio and video may be able to do a telephone call, but it’s important that telephone calls be considered a form of telehealth and be reimbursed to help increase the access to health care by these families. It also makes it easier to facilitate coordination of care. All of this leads to decreased time and costs for patients, families, and providers.”

Within the first few weeks of the pandemic, Dr. Pageler and colleagues at Stanford Children’s Health observed an increase from about 20 telehealth visits per day to more than 700 per day, which has held stable. While the benefits of telehealth are clear, many perceived barriers exist. In a study conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers identified a wide variety of barriers to implementation of telehealth, led by reimbursement, followed by poor business model sustainability, lack of provider time, and provider interest.

“Some of the barriers, like patient preferences for inpatient care, lack of provider interest in telehealth, and lack of provider time were easily overcome during the COVID pandemic,” Dr. Pageler said. “We dedicated the time to train immediately, because the need was so great.”

In 2018, Patrick McMahon, MD, and colleagues at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, launched a teledermatology program that provided direct-to-patient “E-visits” and recently pivoted to using this service only for acne patients through a program called “Acne Express.” The out-of-pocket cost to patients is $50 per consult and nearly 1,500 cases have been completed since 2018, which has saved patients and their parents an estimated 65,000 miles driving to the clinic.

“In the last year we have piloted something called “E-Consults,” which is a provider-to-provider, store-and-forward service,” said Dr. McMahon, a pediatric dermatologist and director of teledermatology at CHOP. “That service is not currently reimbursable, but it’s funded through our hospital. We also have live video visits between provider and patient. That is reimbursable. We have done about 7,500 of those.”

In a 2020 unpublished membership survey of SPD members, Dr. McMahon and colleagues posed the question, “How has teledermatology positively impacted your practice over the past year?” The top three responses were that teledermatology was safe during COVID-19, it provided easy access for follow-up, and it was convenient. In response to the question, “What is the most fundamental change needed for successful delivery of pediatric teledermatology?” the top three responses were reimbursement, improved technology, and regulatory changes.

“When we asked about struggles and difficulties, a lot of responses surrounded the lack of connectivity, both from a technological standpoint and also that lack of connectivity we would feel in person – a lack of rapport,” Dr. McMahon said. “There’s also the inability for us to touch and feel when we examine, and we worry about misdiagnosing. There are also concerns about disparities and for us being sedentary – sitting in one place staring at a screen.”

To optimize the teledermatology experience, he suggested four pillars: educate, optimize, reach out, and tailor. “I think we need to draw upon some of the digital education we already have, including a handout for patients [on the SPD website] that offers tips on taking a clear photograph on their smartphones,” he said. “We’re also trying to use some of the cases and learnings from our teledermatology experiences to teach the providers. We are setting up CME modules that are sort of a flashcard-based teaching mechanism.”

To optimize teledermatology experiences, he continued, tracking demographics, diagnoses, number of cases, and turnaround time is helpful. “We can then track who’s coming in to see us at follow-up after a new visit through telehealth,” Dr. McMahon said. “This helps us repurpose things, pivot as needed, and find any glitches. Surveying the families is also critical. Finally, we need clinical support to tee-up visits and to ensure photos are submitted and efficient, and to match diagnoses and family preference with the right modality.”

Another panelist, Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, who chairs the American Academy of Dermatology’s Task Force on Augmented Intelligence, said that digitally enabled and artificial intelligence (AI)-augmented care delivery offers a “unique opportunity” for increasing access and increasing the value of care delivered to patients.

“The role that we play as clinicians is central, and I think we can make significant strides by doing two things,” said Dr. Ko, chief of medical dermatology for Stanford (Calif.) Health Care. “One: extending the reach of our expertise, and the second: scaling the impact of the care we deliver by clinician-driven, patient-centered, digitally-enabled, AI-augmented care delivery innovation. This opportunity for digital care transformation is more than just a transition from in-person visits to video visits. We have to look at this as an opportunity to leverage the unique aspects of digital capabilities and fundamentally reimagine how we deliver care.”

The AAD’s Position Statement on Augmented Intelligence was published in 2019.

Between March and June of 2021, Neil S. Prose, MD, conducted about 300 televisits with patients. “I had a few spectacular visits where, for example, a teenage patient who had been challenging showed me all of her artwork and we became instantly more connected,” said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology, pediatrics, and global health at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “Then there’s the potential for a long-term improvement in health care for some patients.”

But there were also downsides to the process, he said, including dropped connections, poor picture and sound quality, patient no-shows, and patients reporting they were unable to schedule a telemedicine visit. “The problems I was experiencing were not just between me and my patients; the problems are systemic, and they have to do with various factors: the portal, the equipment, Internet access, and inadequate or no health insurance,” said Dr. Prose, past president of the SPD.

Portal-related challenges include a lack of focus on culture, literacy, and numeracy, “and these worsen inequities,” he said. “Another issue related to portal design has to do with language. Very few of the portals allow patients to participate in Spanish. This has been particularly difficult for those of us who use Epic. The next issue has to deal with the devices the patients are using. Cell phone visits can be very problematic. Unfortunately, lower-income Americans have a lower level of technology adoption, and many are relying on smartphones for their Internet access. That’s the root of some of our problems.”

To achieve digital health equity, Dr. Prose emphasized the need for federal mandates for tools for digital health access usable by underserved populations and federal policies that increase broadband access and view it as a human right. He also underscored the importance of federal policies that ensure continuation of adequate telemedicine reimbursement beyond the pandemic and urged health institutions to invest in portals that address the needs of the underserved.

“What is the future of telemedicine? The answer is complicated,” said Dr. Prose, who recommended a recently published article in JAMA on digital health equity. “There have been several rumblings of large insurers who plan to pull the rug on telemedicine as soon as the pandemic is more or less over. So, all of our projections about this being a wonderful trend for the future may be for naught if the insurers don’t step up to the table.”

None of the presenters reported having financial disclosures.

pre-AAD meeting.

“We have seen large numbers of children struggle with access to school and access to health care because of lack of access to devices, challenges of broadband Internet access, culture, language, and educational barriers – just having trouble being comfortable with this technology,” said Natalie Pageler, MD, a pediatric intensivist and chief medical information officer at Stanford Children’s Health, Palo Alto, Calif.

“There are also privacy concerns, especially in situations where there are multiple families within a household. Finally, it’s important to remember that policy and reimbursement issues may have a significant effect on some of the socioeconomic barriers,” she added. “For example, many of our families who don’t have access to audio and video may be able to do a telephone call, but it’s important that telephone calls be considered a form of telehealth and be reimbursed to help increase the access to health care by these families. It also makes it easier to facilitate coordination of care. All of this leads to decreased time and costs for patients, families, and providers.”

Within the first few weeks of the pandemic, Dr. Pageler and colleagues at Stanford Children’s Health observed an increase from about 20 telehealth visits per day to more than 700 per day, which has held stable. While the benefits of telehealth are clear, many perceived barriers exist. In a study conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers identified a wide variety of barriers to implementation of telehealth, led by reimbursement, followed by poor business model sustainability, lack of provider time, and provider interest.

“Some of the barriers, like patient preferences for inpatient care, lack of provider interest in telehealth, and lack of provider time were easily overcome during the COVID pandemic,” Dr. Pageler said. “We dedicated the time to train immediately, because the need was so great.”

In 2018, Patrick McMahon, MD, and colleagues at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, launched a teledermatology program that provided direct-to-patient “E-visits” and recently pivoted to using this service only for acne patients through a program called “Acne Express.” The out-of-pocket cost to patients is $50 per consult and nearly 1,500 cases have been completed since 2018, which has saved patients and their parents an estimated 65,000 miles driving to the clinic.

“In the last year we have piloted something called “E-Consults,” which is a provider-to-provider, store-and-forward service,” said Dr. McMahon, a pediatric dermatologist and director of teledermatology at CHOP. “That service is not currently reimbursable, but it’s funded through our hospital. We also have live video visits between provider and patient. That is reimbursable. We have done about 7,500 of those.”

In a 2020 unpublished membership survey of SPD members, Dr. McMahon and colleagues posed the question, “How has teledermatology positively impacted your practice over the past year?” The top three responses were that teledermatology was safe during COVID-19, it provided easy access for follow-up, and it was convenient. In response to the question, “What is the most fundamental change needed for successful delivery of pediatric teledermatology?” the top three responses were reimbursement, improved technology, and regulatory changes.

“When we asked about struggles and difficulties, a lot of responses surrounded the lack of connectivity, both from a technological standpoint and also that lack of connectivity we would feel in person – a lack of rapport,” Dr. McMahon said. “There’s also the inability for us to touch and feel when we examine, and we worry about misdiagnosing. There are also concerns about disparities and for us being sedentary – sitting in one place staring at a screen.”

To optimize the teledermatology experience, he suggested four pillars: educate, optimize, reach out, and tailor. “I think we need to draw upon some of the digital education we already have, including a handout for patients [on the SPD website] that offers tips on taking a clear photograph on their smartphones,” he said. “We’re also trying to use some of the cases and learnings from our teledermatology experiences to teach the providers. We are setting up CME modules that are sort of a flashcard-based teaching mechanism.”

To optimize teledermatology experiences, he continued, tracking demographics, diagnoses, number of cases, and turnaround time is helpful. “We can then track who’s coming in to see us at follow-up after a new visit through telehealth,” Dr. McMahon said. “This helps us repurpose things, pivot as needed, and find any glitches. Surveying the families is also critical. Finally, we need clinical support to tee-up visits and to ensure photos are submitted and efficient, and to match diagnoses and family preference with the right modality.”

Another panelist, Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, who chairs the American Academy of Dermatology’s Task Force on Augmented Intelligence, said that digitally enabled and artificial intelligence (AI)-augmented care delivery offers a “unique opportunity” for increasing access and increasing the value of care delivered to patients.

“The role that we play as clinicians is central, and I think we can make significant strides by doing two things,” said Dr. Ko, chief of medical dermatology for Stanford (Calif.) Health Care. “One: extending the reach of our expertise, and the second: scaling the impact of the care we deliver by clinician-driven, patient-centered, digitally-enabled, AI-augmented care delivery innovation. This opportunity for digital care transformation is more than just a transition from in-person visits to video visits. We have to look at this as an opportunity to leverage the unique aspects of digital capabilities and fundamentally reimagine how we deliver care.”

The AAD’s Position Statement on Augmented Intelligence was published in 2019.

Between March and June of 2021, Neil S. Prose, MD, conducted about 300 televisits with patients. “I had a few spectacular visits where, for example, a teenage patient who had been challenging showed me all of her artwork and we became instantly more connected,” said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology, pediatrics, and global health at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “Then there’s the potential for a long-term improvement in health care for some patients.”

But there were also downsides to the process, he said, including dropped connections, poor picture and sound quality, patient no-shows, and patients reporting they were unable to schedule a telemedicine visit. “The problems I was experiencing were not just between me and my patients; the problems are systemic, and they have to do with various factors: the portal, the equipment, Internet access, and inadequate or no health insurance,” said Dr. Prose, past president of the SPD.

Portal-related challenges include a lack of focus on culture, literacy, and numeracy, “and these worsen inequities,” he said. “Another issue related to portal design has to do with language. Very few of the portals allow patients to participate in Spanish. This has been particularly difficult for those of us who use Epic. The next issue has to deal with the devices the patients are using. Cell phone visits can be very problematic. Unfortunately, lower-income Americans have a lower level of technology adoption, and many are relying on smartphones for their Internet access. That’s the root of some of our problems.”

To achieve digital health equity, Dr. Prose emphasized the need for federal mandates for tools for digital health access usable by underserved populations and federal policies that increase broadband access and view it as a human right. He also underscored the importance of federal policies that ensure continuation of adequate telemedicine reimbursement beyond the pandemic and urged health institutions to invest in portals that address the needs of the underserved.

“What is the future of telemedicine? The answer is complicated,” said Dr. Prose, who recommended a recently published article in JAMA on digital health equity. “There have been several rumblings of large insurers who plan to pull the rug on telemedicine as soon as the pandemic is more or less over. So, all of our projections about this being a wonderful trend for the future may be for naught if the insurers don’t step up to the table.”

None of the presenters reported having financial disclosures.

pre-AAD meeting.

“We have seen large numbers of children struggle with access to school and access to health care because of lack of access to devices, challenges of broadband Internet access, culture, language, and educational barriers – just having trouble being comfortable with this technology,” said Natalie Pageler, MD, a pediatric intensivist and chief medical information officer at Stanford Children’s Health, Palo Alto, Calif.

“There are also privacy concerns, especially in situations where there are multiple families within a household. Finally, it’s important to remember that policy and reimbursement issues may have a significant effect on some of the socioeconomic barriers,” she added. “For example, many of our families who don’t have access to audio and video may be able to do a telephone call, but it’s important that telephone calls be considered a form of telehealth and be reimbursed to help increase the access to health care by these families. It also makes it easier to facilitate coordination of care. All of this leads to decreased time and costs for patients, families, and providers.”

Within the first few weeks of the pandemic, Dr. Pageler and colleagues at Stanford Children’s Health observed an increase from about 20 telehealth visits per day to more than 700 per day, which has held stable. While the benefits of telehealth are clear, many perceived barriers exist. In a study conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers identified a wide variety of barriers to implementation of telehealth, led by reimbursement, followed by poor business model sustainability, lack of provider time, and provider interest.

“Some of the barriers, like patient preferences for inpatient care, lack of provider interest in telehealth, and lack of provider time were easily overcome during the COVID pandemic,” Dr. Pageler said. “We dedicated the time to train immediately, because the need was so great.”

In 2018, Patrick McMahon, MD, and colleagues at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, launched a teledermatology program that provided direct-to-patient “E-visits” and recently pivoted to using this service only for acne patients through a program called “Acne Express.” The out-of-pocket cost to patients is $50 per consult and nearly 1,500 cases have been completed since 2018, which has saved patients and their parents an estimated 65,000 miles driving to the clinic.

“In the last year we have piloted something called “E-Consults,” which is a provider-to-provider, store-and-forward service,” said Dr. McMahon, a pediatric dermatologist and director of teledermatology at CHOP. “That service is not currently reimbursable, but it’s funded through our hospital. We also have live video visits between provider and patient. That is reimbursable. We have done about 7,500 of those.”

In a 2020 unpublished membership survey of SPD members, Dr. McMahon and colleagues posed the question, “How has teledermatology positively impacted your practice over the past year?” The top three responses were that teledermatology was safe during COVID-19, it provided easy access for follow-up, and it was convenient. In response to the question, “What is the most fundamental change needed for successful delivery of pediatric teledermatology?” the top three responses were reimbursement, improved technology, and regulatory changes.

“When we asked about struggles and difficulties, a lot of responses surrounded the lack of connectivity, both from a technological standpoint and also that lack of connectivity we would feel in person – a lack of rapport,” Dr. McMahon said. “There’s also the inability for us to touch and feel when we examine, and we worry about misdiagnosing. There are also concerns about disparities and for us being sedentary – sitting in one place staring at a screen.”

To optimize the teledermatology experience, he suggested four pillars: educate, optimize, reach out, and tailor. “I think we need to draw upon some of the digital education we already have, including a handout for patients [on the SPD website] that offers tips on taking a clear photograph on their smartphones,” he said. “We’re also trying to use some of the cases and learnings from our teledermatology experiences to teach the providers. We are setting up CME modules that are sort of a flashcard-based teaching mechanism.”

To optimize teledermatology experiences, he continued, tracking demographics, diagnoses, number of cases, and turnaround time is helpful. “We can then track who’s coming in to see us at follow-up after a new visit through telehealth,” Dr. McMahon said. “This helps us repurpose things, pivot as needed, and find any glitches. Surveying the families is also critical. Finally, we need clinical support to tee-up visits and to ensure photos are submitted and efficient, and to match diagnoses and family preference with the right modality.”

Another panelist, Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, who chairs the American Academy of Dermatology’s Task Force on Augmented Intelligence, said that digitally enabled and artificial intelligence (AI)-augmented care delivery offers a “unique opportunity” for increasing access and increasing the value of care delivered to patients.

“The role that we play as clinicians is central, and I think we can make significant strides by doing two things,” said Dr. Ko, chief of medical dermatology for Stanford (Calif.) Health Care. “One: extending the reach of our expertise, and the second: scaling the impact of the care we deliver by clinician-driven, patient-centered, digitally-enabled, AI-augmented care delivery innovation. This opportunity for digital care transformation is more than just a transition from in-person visits to video visits. We have to look at this as an opportunity to leverage the unique aspects of digital capabilities and fundamentally reimagine how we deliver care.”

The AAD’s Position Statement on Augmented Intelligence was published in 2019.

Between March and June of 2021, Neil S. Prose, MD, conducted about 300 televisits with patients. “I had a few spectacular visits where, for example, a teenage patient who had been challenging showed me all of her artwork and we became instantly more connected,” said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology, pediatrics, and global health at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “Then there’s the potential for a long-term improvement in health care for some patients.”

But there were also downsides to the process, he said, including dropped connections, poor picture and sound quality, patient no-shows, and patients reporting they were unable to schedule a telemedicine visit. “The problems I was experiencing were not just between me and my patients; the problems are systemic, and they have to do with various factors: the portal, the equipment, Internet access, and inadequate or no health insurance,” said Dr. Prose, past president of the SPD.

Portal-related challenges include a lack of focus on culture, literacy, and numeracy, “and these worsen inequities,” he said. “Another issue related to portal design has to do with language. Very few of the portals allow patients to participate in Spanish. This has been particularly difficult for those of us who use Epic. The next issue has to deal with the devices the patients are using. Cell phone visits can be very problematic. Unfortunately, lower-income Americans have a lower level of technology adoption, and many are relying on smartphones for their Internet access. That’s the root of some of our problems.”

To achieve digital health equity, Dr. Prose emphasized the need for federal mandates for tools for digital health access usable by underserved populations and federal policies that increase broadband access and view it as a human right. He also underscored the importance of federal policies that ensure continuation of adequate telemedicine reimbursement beyond the pandemic and urged health institutions to invest in portals that address the needs of the underserved.

“What is the future of telemedicine? The answer is complicated,” said Dr. Prose, who recommended a recently published article in JAMA on digital health equity. “There have been several rumblings of large insurers who plan to pull the rug on telemedicine as soon as the pandemic is more or less over. So, all of our projections about this being a wonderful trend for the future may be for naught if the insurers don’t step up to the table.”

None of the presenters reported having financial disclosures.

FROM THE SPD PRE-AAD MEETING

Guarding against nonmelanoma skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients

The incidence of posttransplant malignancy among solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) is 10%; skin cancer, primarily nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), constitutes 49.5% of all malignancies in this population.1 The etiology of the increased risk of cutaneous malignancy in SOTR is multifactorial:

- The skin of SOTRs is photosensitive, compared to that of immunocompetent patients, thus predisposing SOTRs to carcinogenic damage resulting from exposure to UV light.2

- Immunosuppression plays a key role in increasing the risk of cutaneous malignancy by inhibiting the ability of the immune system to recognize and destroy tumor cells.3

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) can play a role in carcinogenesis by promoting molecular pathways to proliferation and survival of nascent tumor cells4;Times New Romanβ-HPV strains are disseminated ubiquitously in the skin of immunosuppressed patients.5

- Some medications administered after transplantation can be directly carcinogenic.

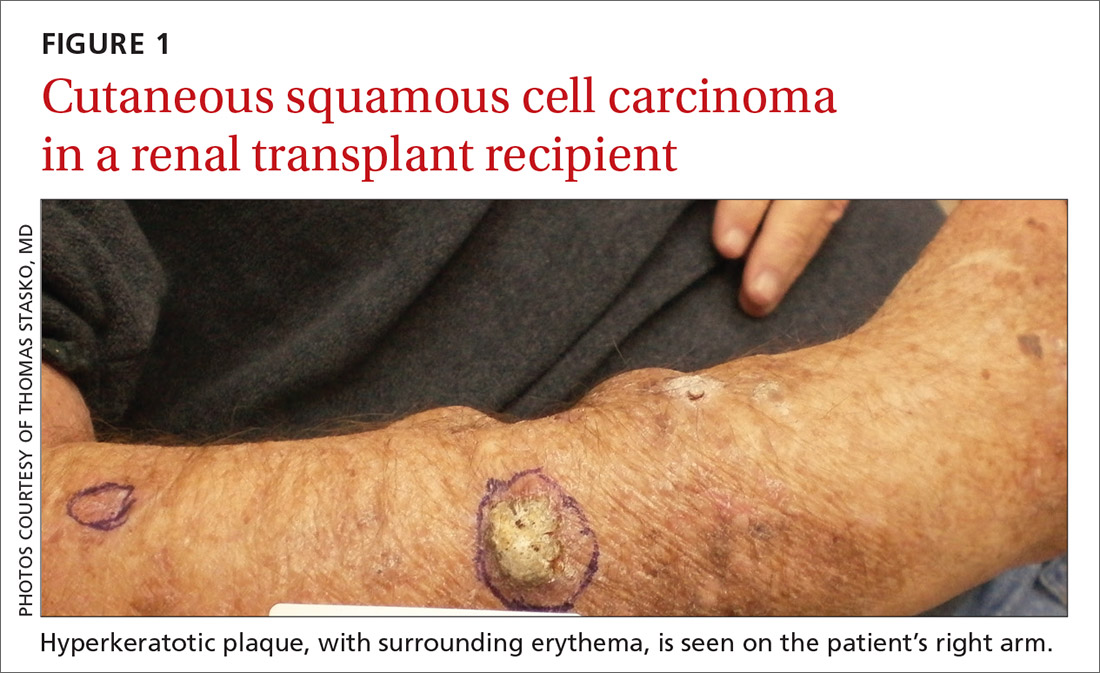

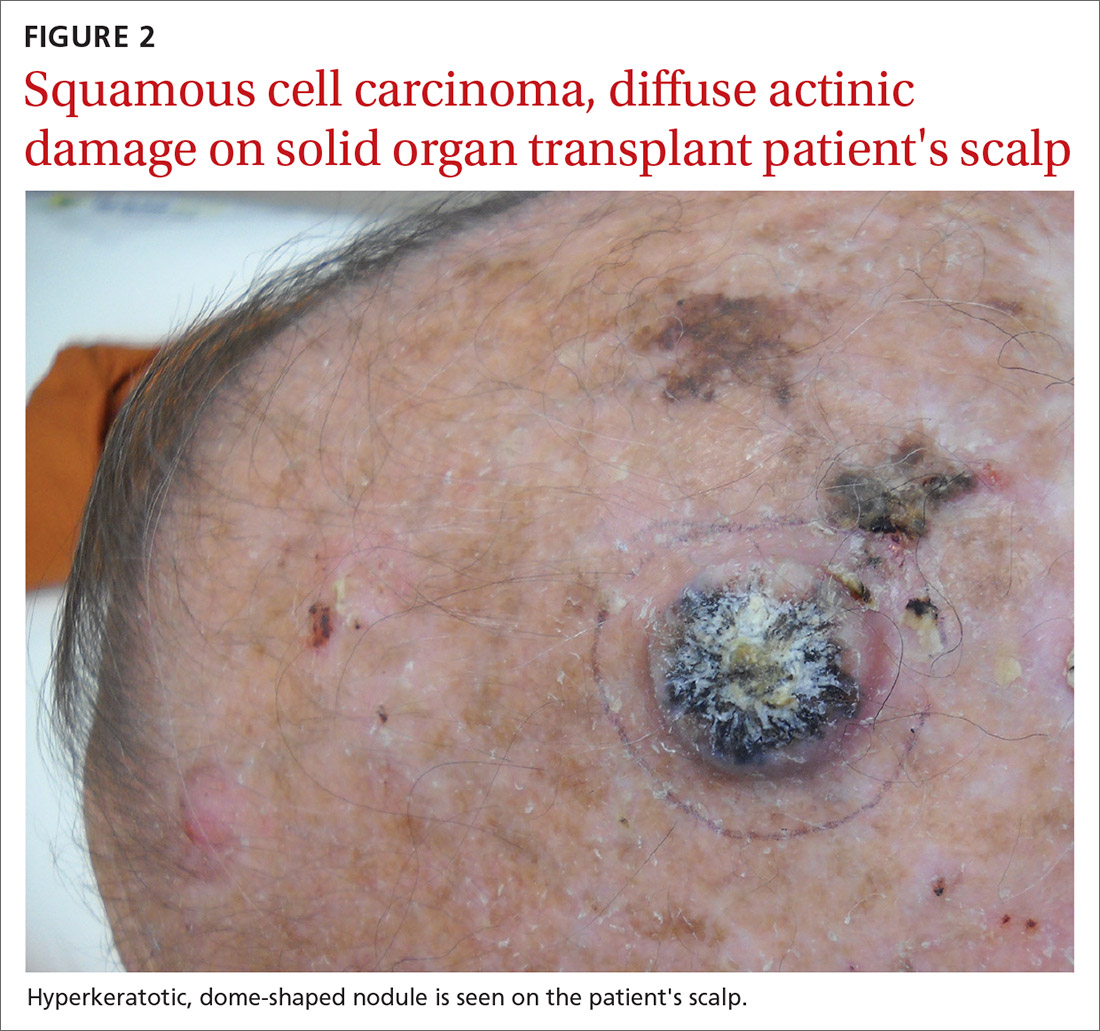

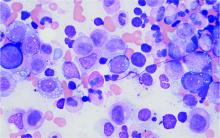

NMSC in SOTRs also differs qualitatively from NMSC in immunocompetent patients. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) (FIGUREs 1 and 2) is the most common skin cancer among SOTRs, whereas basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer in the general population.3 cSCC in the SOTR population tends to be more aggressive, with more rapid local invasion and an increased rate of both in-transit and distant metastases, leading to an increase in morbidity and mortality. Mortality of metastatic cSCC among SOTRs is approximately 50%, compared to 20% in an otherwise healthy population.3,6-8

The problem is relevant to primary care

Screening. Because there is a demonstrated reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with early detection and treatment of NMSC, regular screening of skin is important in the SOTR population.9 A study in Ontario, Canada, from 1994 to 2012 and comprising 10,183 SOTRs, found that adherence to an annual skin check regimen for ≥ 75% of the observation period was associated with a 34% reduction in cutaneous BCC- and cSCC-related morbidity or death (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48-0.92).10 Although routine follow-up with a dermatologist is recommended for SOTRs,9,11-15 only 2.1% of patients in the Canadian study were fully adherent with annual skin examination, and 55% never visited a dermatologist.10 Consequently, primary care physicians can play a key role in skin cancer screening for SOTRs.

Education regarding the importance of protection from the sun is also an essential part of primary care. A 2018 study of SOTRs in Turkey demonstrated that16

- 46% expressed a lack of knowledge of the hazards of sun exposure

- 44% did not recall ever receiving medical advice regarding sun protection

- 89% did not wear sun-protective clothing

- 86% did not use sunscreen daily.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the positive effect that preventive education and attendance at a dermatology or skin cancer screening clinic can have on sun-protective behaviors among SOTRs.9,16-18 In the Turkish study, 100% of patients who reported using sunscreen daily had been undergoing regular dermatologic examination.16

In this article, we review current management guidelines regarding the prevention and treatment of NMSC in SOTRs.

Recommendations for prevention

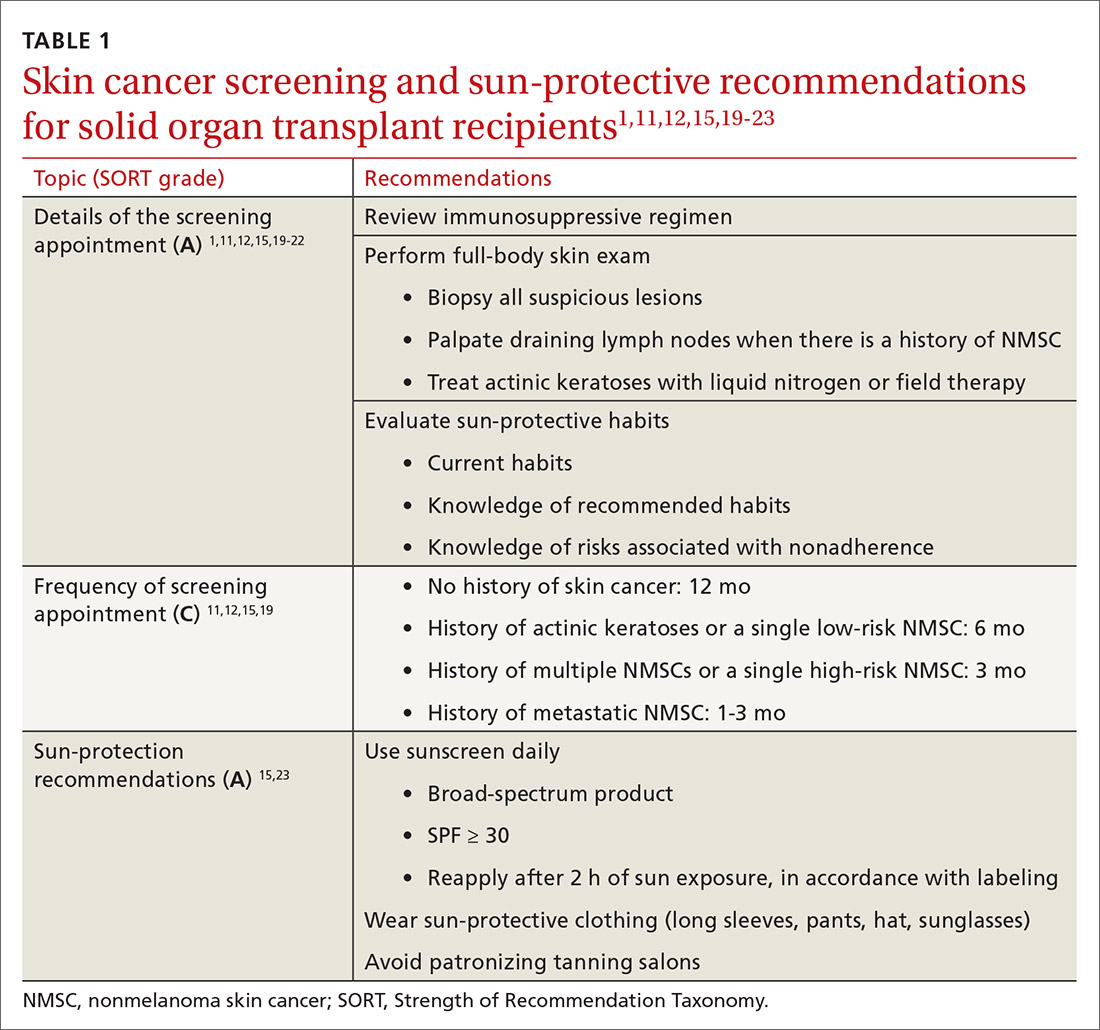

Screening skin exams (TABLE 11,11,12,15,19-23). Although definitive guidelines do not exist regarding the frequency of a screening skin exam for SOTRs, multiple frequency-determining algorithms have been proposed.11,12,15,19 The recommended frequency of a skin exam is based on history of skin cancer; for SOTRs, the most common recommendation19 is a full-body skin examination as follows:

- annually—when there is no history of skin cancer

- every 6 months—when there is a history of actinic keratoses (AKs; precancerous lesions that carry a risk of transforming into cSCC) or a single low-risk NMSC

- every 3 months—when there is a history of multiple NMSCs or a single high-risk NMSC

- every 1 to 3 months—when there is a history of metastatic disease.

Continue to: Other risk factors...

Other risk factors for NMSC to consider in SOTRs when determining an appropriate follow-up regimen include any of the following1,20,21,24-26:

- male gender, fair skin, history of childhood sunburn, history of smoking

- lung or heart transplantation, history of episodes of transplant rejection, age ≥ 50 years at transplantation

- immunosuppression with calcineurin inhibitors, compared to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors

- immunosuppression with cyclosporine, compared to tacrolimus

- an immunosuppressive regimen with > 1 immunosuppressant or an increased degree of immunosuppression

- antithymocyte globulin within the first year posttransplantation.

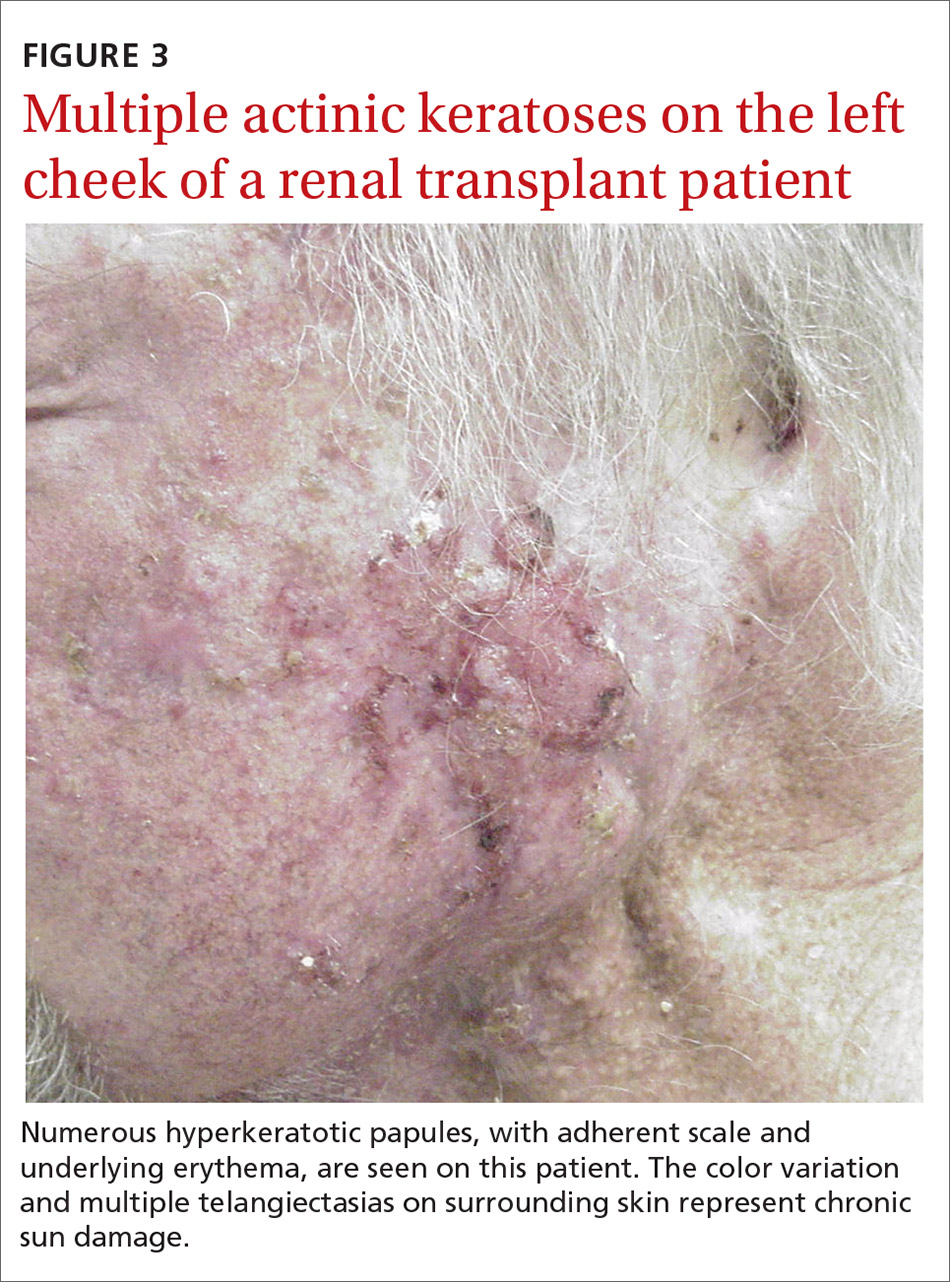

Because the intensity of immunosuppression and individual immunosuppressants used affect the risk of NMSC, conduct a thorough medication review with SOTRs at all visits. Ask about new, changing, or symptomatic (pruritic, painful, bleeding) skin lesions, and perform a full-body skin exam. Palpate draining lymph nodes if the patient has a history of NMSC.15 AKs (FIGURE 3) should be treated aggressively with liquid nitrogen or field therapy. Lesions suspicious for NMSC should be biopsied and sent for histologic evaluation.22 Shave, punch, and excisional biopsies are all adequate techniques; however, because all cSCCs in SOTRs are considered high risk for aggressive features, biopsy should extend at least into the reticular dermis to allow evaluation for invasive disease.22

Sun-protective measures (TABLE 11,11,12,15,19-23). Inquire about patients’ habits related to protection from the sun, their knowledge of recommended sun-protective measures, and risks associated with nonadherence. Recommended sun-protective measures include

- daily broad-spectrum sunscreen (SPF ≥ 30), reapplied every 2 hours of sun exposure, in accordance with labeling instructions23

- sun-protective clothing (pants, long sleeves, hat, sunglasses)23

- avoidance of tanning salons.15

SOTRs who adequately adhere to sun-protective measures might need vitamin D supplementation because sunscreen and sun-protective clothing inhibit cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D.15

Recommendations for treatment

Consider chemoprophylactic therapy for SOTRs who have had multiple prior cutaneous malignancies or multiple AKs.

Continue to: Topical chemoprophylaxis

Topical chemoprophylaxis

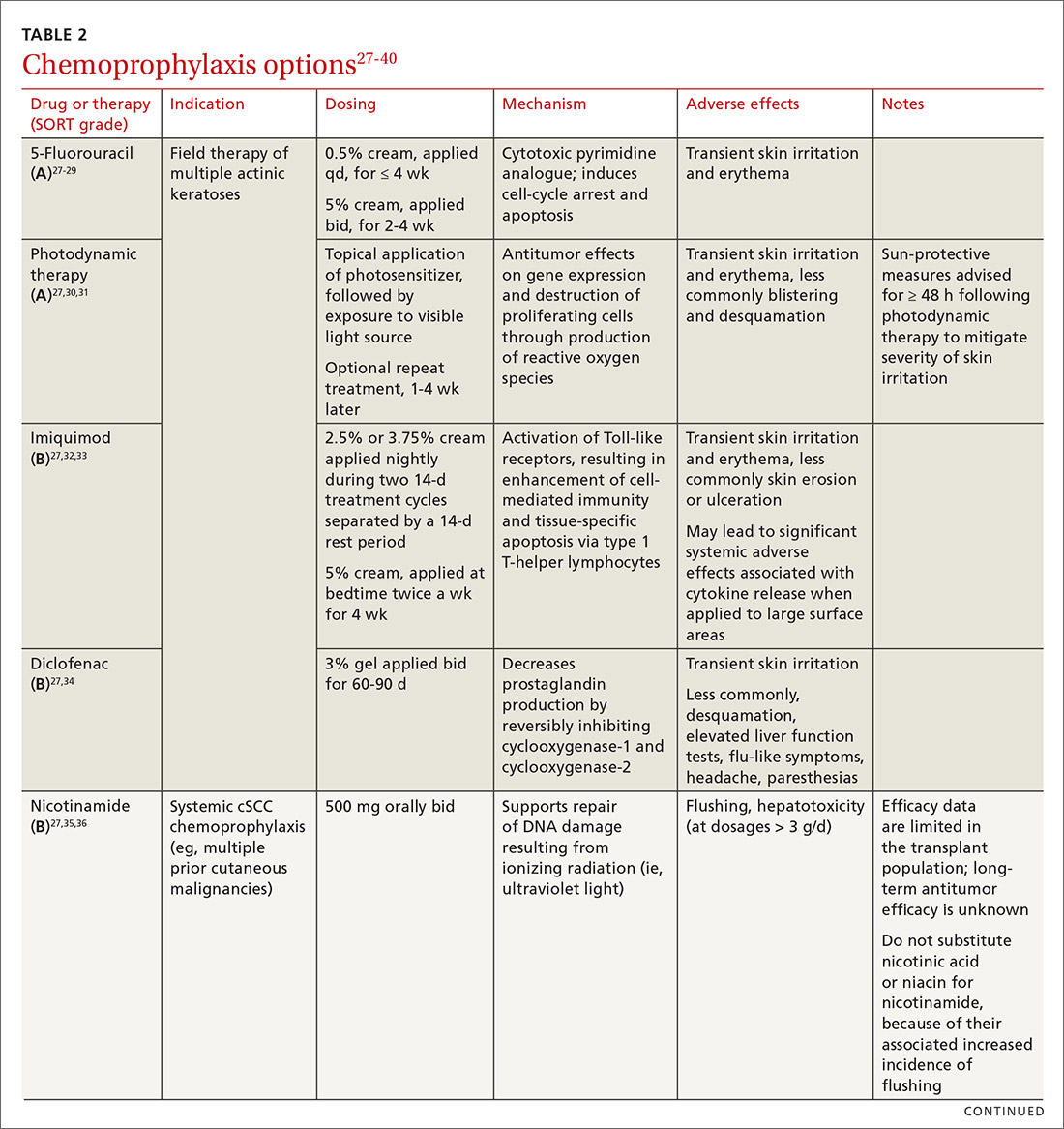

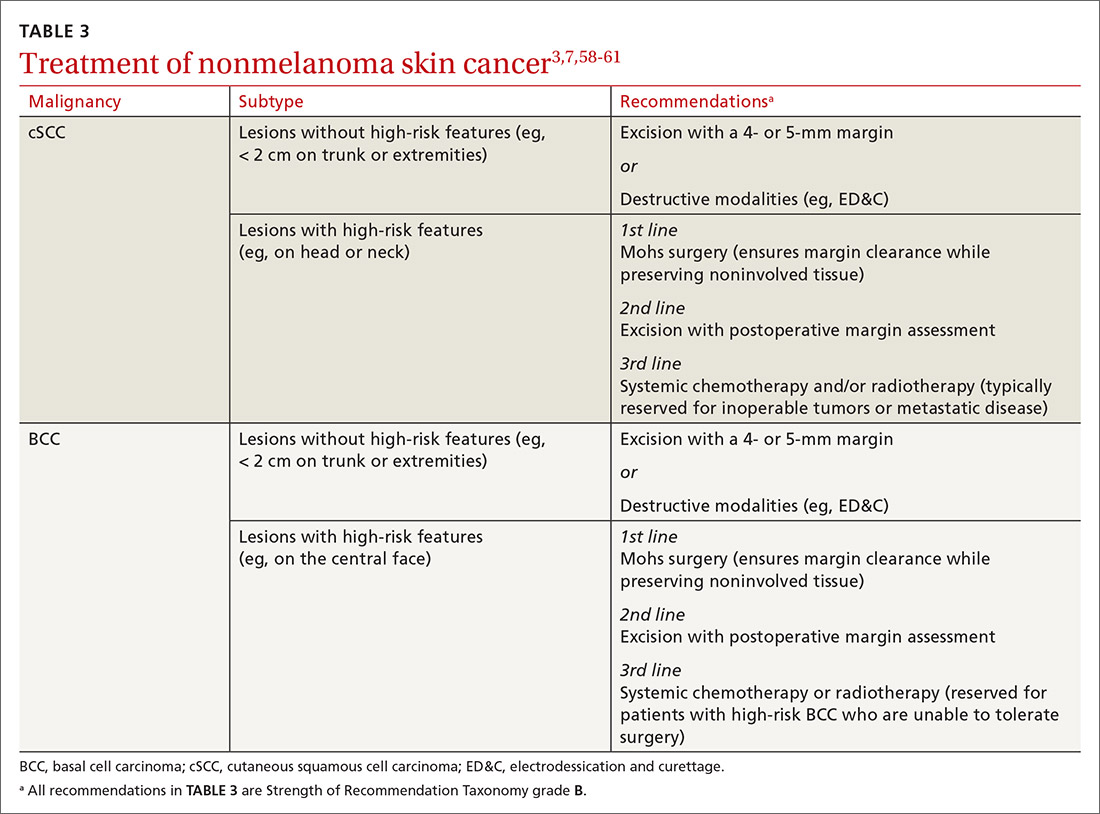

Topical medications used for cSCC chemoprophylaxis include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), photodynamic therapy (PDT), imiquimod, ingenol mebutate, topical retinoids, and diclofenac.27 (See TABLE 2.27-40) Of these, the latter 3 are used less commonly because of the small packaging size of ingenol mebutate and the relative lack of efficacy data for topical retinoids and diclofenac.27 Imiquimod is often avoided when treating large surface areas because of the risk of systemic adverse effects associated with cytokine release.27

5-FU is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of AKs, and is used off-label for treating cSCC in situ (Bowen disease). It is the most commonly used topical therapy for field disease.27-29 5-FU is typically applied once or twice daily for 3 to 4 weeks. Common adverse effects include transient skin irritation and erythema.27

PDT involves topical application of a photosensitizer, such as 5-aminolevulinic acid or methyl aminolevulinate, followed by exposure to a visible light source, leading to antitumor effects on gene expression and destruction of proliferating cells through production of reactive oxygen species.30,31 Evidence is sufficient to support routine use of PDT for AKs and Bowen disease.30 A mild sunburn-like reaction is common following PDT, with transient erythema and discomfort typically lasting 1 to 2 weeks but not typically necessitating analgesic therapy.27

Imiquimod is a ligand that binds to and activates Toll-like receptor 7, leading to enhancement of the cell-mediated antitumor immune response and resultant tissue-specific apoptosis coordinated by type 1 T-helper lymphocytes.32 Topical imiquimod cream is FDA approved for field treatment of AKs at 2.5%, 3.75%, and 5% concentrations; efficacy has been demonstrated in the SOTR population.33,41 Multiple studies in immunocompetent patients have suggested that imiquimod might be slightly less efficacious than 5-FU.42-44

The tolerability of field treatment with imiquimod has been called into question.27 However, in a 2019 study comparing adverse reactions among 513 immunocompetent patients with field disease who were treated with either 5-FU 5% cream; imiquimod 5% cream; PDT with methyl aminolevulinate; or ingenol mebutate 0.015% gel, a similar or smaller percentage of patients treated with imiquimod reported moderate-to-severe itching, moderate-to-severe pain, and any adverse events, compared to patients treated with the other options.44

Continue to: Diclofenac

Diclofenac is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug that reversibly inhibits the enzymes cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2, resulting in a decrease in the formation of inflammatory prostaglandins, which have been observed in chronically sun-damaged skin, AKs, and cSCC.34,45 Diclofenac 3% gel, applied topically twice daily for 60 to 90 days has been approved by the FDA for treatment of AKs, in conjunction with sun avoidance.34 Topical diclofenac has been demonstrated to be efficacious in treating AKs in the SOTR population46,47; however, multiple meta-analyses using data from immunocompetent patients have demonstrated that topical diclofenac is inferior to other treatment options, particularly 5-FU, at achieving complete clearance of AKs.43,48,49 Diclofenac might be a useful option when patient adherence is expected to be difficult because of adverse effects of therapy: Multiple studies have suggested that diclofenac might be more tolerable than other options.43,48,50

Systemic chemoprophylaxis

Systemic therapies that have been used for chemoprophylaxis against cutaneous malignancy include nicotinamide, oral retinoids, capecitabine, and HPV vaccination. (See TABLE 2.27-40)

Nicotinamide, the amide form of vitamin B3, protects against cutaneous malignancy by aiding repair of DNA damaged by ionizing radiation, such as UV light.27 Efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing development of new AKs and cSCC in immunocompetent patients with a history of more than 2 keratinocyte carcinomas within a 5-year span.27,35 Nicotinamide is especially relevant to the SOTR population because it reduces the level of cutaneous immunity suppression induced by UV radiation without altering patients’ baseline immunity.27,36

There are insufficient long-term follow-up data in the literature to assess the sustainability of the antitumor effects of nicotinamide; studies specific to the SOTR population have been underpowered for assessing its impact on formation of cSCC.27,35Patients taking nicotinamide should be informed of the risk of liver failure at dosages > 3 g/d (antitumor efficacy has been demonstrated at 500 mg twice daily) and advised to avoid purchasing over-the-counter nicotinic acid or niacin as a substitute for nicotinamide, because of the increased incidence of flushing associated with their use.27

Oral retinoids. Systemic retinoids—in particular, acitretin—are efficacious in reducing the risk of cSCC in SOTRs.27,37,38 The primary drawback to cSCC prophylaxis with oral retinoids is a rebound effect, in which treatment discontinuation leads to a rapid return to baseline cSCC formation.27

Continue to: Pregnancy must be avoided...

Pregnancy must be avoided while taking an oral retinoid. Because acitretin can persist in the body for years after discontinuation, its use should generally be avoided in patients of childbearing potential. An FDA black box warning states that patients of childbearing potential must be counseled to use 2 forms of birth control to avoid pregnancy for ≥ 3 years after cessation of oral acitretin. Prior to initiation of oral retinoid therapy, the following baseline laboratory tests should be obtained: complete blood count, creatinine, lipid panel, and liver function tests. For patients with a history of chronic kidney disease or renal transplantation, the lipid panel, liver function tests, and creatinine assay should be repeated with each dosage adjustment and every 3 months once goal-dosing is achieved.27

Capecitabine is typically initiated with the help of Medical Oncology.27,40 A prodrug metabolized by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase to 5-FU, capecitabine interacts with warfarin, leading to a significant increase in prothrombin time.39 Other adverse effects associated with oral capecitabine include fatigue, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, diarrhea, and, rarely, neutropenia. Although dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency is rare, treatment with capecitabine in patients who have this enzyme deficiency might lead to severe toxicity or death.27

HPV vaccination. HPV might play a role in the development of cutaneous malignancy, especially in immunosuppressed patients.4,5 The utility of HPV vaccination in the prevention of NMSC has yet to be determined, but vaccination has been shown, in case reports, to be helpful in immunocompetent patients.51,52 The immunogenicity of HPV vaccination in the SOTR population is uncertain, and the most common HPV types found in SOTRs are not specifically covered by available HPV vaccines.19

The role of immunosuppression reduction and immunosuppressive replacement

Both the degree of immunosuppression and the individual agents used can affect a patient’s risk of NMSC. Immunosuppression reduction should be considered if skin cancer poses a major risk to the patient’s health and if that risk outweighs the risk of graft rejection associated with immunosuppression reduction.27 In a cohort of 180 kidney and liver SOTRs who developed de novo carcinoma (excluding NMSC) after transplantation, neither reduction of immunosuppression nor introduction of an mTOR inhibitor affected graft survival or oncologic treatment tolerance.53 Because mTOR inhibitors have a protective effect against development of NMSC, they are the preferred choice of immunosuppressive agent from a dermatologic perspective.1,27,54-57 Decisions regarding changes in immunosuppression are generally made by, or in collaboration with, the patient’s transplant physician.

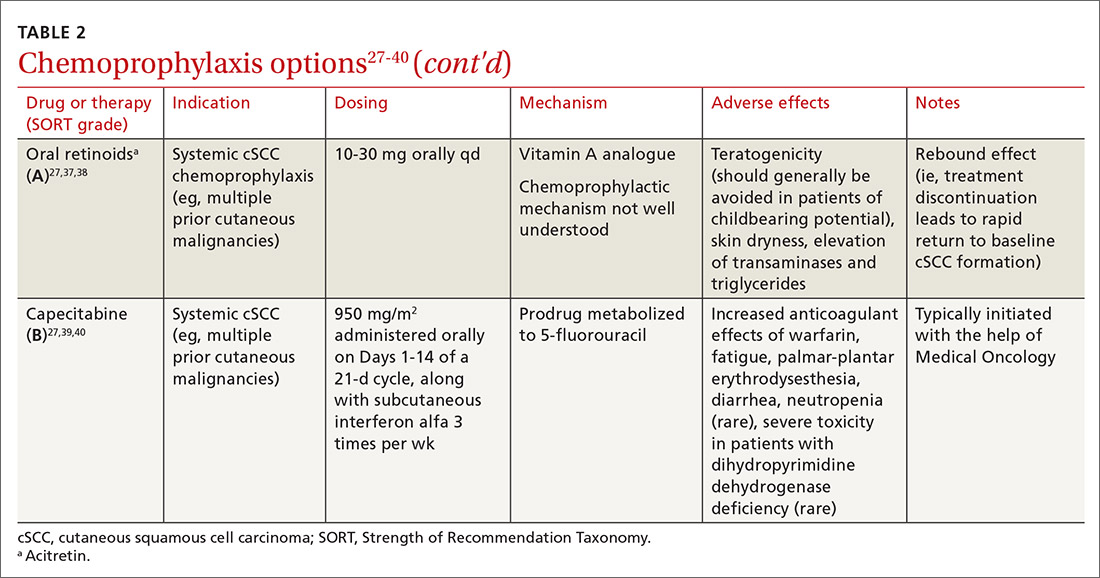

Recommendations: Treating cSCC

Risk should guide strategy

Small lesions of the trunk and extremities without high-risk features can be treated with a destructive method (eg, electrodessication and curettage). However, lesions of the head and neck and those found to have features consistent with an increased risk of recurrence or metastasis should be treated aggressively.3,58,59

Continue to: Risk factors for invasive growth...

Risk factors for invasive growth, recurrence, or metastasis of cSCC in SOTRs are multiple lesions or satellite lesions, indistinct clinical borders, rapid growth, ulceration, and recurrence after treatment.60 The risk of invasive growth, recurrence, and metastasis of cSCC also increases with size and location of the lesion, according to this framework60:

- any size in scar tissue, areas of chronic inflammation, and fields of prior radiation therapy

- ≥ 0.6 cm on hands, feet, genitalia, and mask areas of the face (central face, eyelids, eyebrows, nose, lips, chin, mandible, and temporal, preauricular, postauricular, and periorbital areas)

- > 1 cm on cheeks, forehead, neck, and scalp

- > 2 cm on the trunk and extremities.

In addition, specific findings on histologic analysis portend increased risk of invasive growth, recurrence, or metastasis:

- poor differentiation

- deep extension of the tumor into subcutaneous fat

- perineural invasion or inflammation

- perivascular or intravascular invasion.

Treatment modalities

Mohs surgery is preferred to ensure margin clearance while preserving noninvolved tissue3,7 (FIGURE 4). If Mohs surgery is not possible, the lesion should be excised with 3- to 10-mm margins.3,60 Based on current literature, the roles of nodal staging, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and adjuvant therapy are not well defined, but it is likely that these interventions will play a pivotal role in the management of advanced cSCC in SOTRs in the future.3

Nonsurgical therapeutic options for primary or adjuvant treatment of cSCC include systemic chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors. (For more on treatment modalities, see TABLE 3.3,7,58-61)

Recommendations: Treating BCC

BCC in SOTRs is treated similarly (TABLE 33,7,58-61) to how it is treated in the immunocompetent population—except that SOTRs require closer follow-up than nontransplant patients because they are at higher risk of recurrence and new NMSCs.3 Standard management after biopsy is either3,61:

- Mohs surgery to ensure margin control (for most BCCs on the head and neck and those with clinical or histologic risk factors for recurrence or aggressive behavior)

- excision with a 4- or 5-mm margin or a destructive modality (for BCCs on the trunk and extremities without risk factors for recurrence).

Radiotherapy is an alternative for patients with high-risk BCCs who are unable to tolerate surgery.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Lindsey Collins, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 619 NE 13th Steet, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; Lindsey-Collins@ouhsc.edu

1. Bhat M, Mara K, Dierkhising R, et al. Immunosuppression, race, and donor-related risk factors affect de novo cancer incidence across solid organ transplant recipients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:1236-1246. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.025

2. Togsverd-Bo K, Philipsen PA, Haedersdal M, et al. Organ transplant recipients express enhanced skin autofluorescence and pigmentation at skin cancer sites. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2018;188:1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.08.008

3. Kearney L, Hogan D, Conlon P, et al. High-risk cutaneous malignancies and immunosuppression: challenges for the reconstructive surgeon in the renal transplant population. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:922-930. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.03.005

4. Borgogna C, Olivero C, Lanfredini S, et al. β-HPV infection correlates with early stages of carcinogenesis in skin tumors and patient-derived xenografts from a kidney transplant recipient cohort. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:117. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00117

5. Nunes EM, Talpe-Nunes V, Sichero L. Epidemiology and biology of cutaneous human papillomavirus. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73(suppl 1):e489s. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2018/e489s

6. Pini AM, Koch S, L, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthoma following topical imiquimod for in situ squamous cell carcinoma of the skin in a renal transplant recipient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(suppl 5):S116-S117. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.018

7. Ilyas M, Zhang N, Sharma A. Residual squamous cell carcinoma after shave biopsy in solid organ transplant recipients. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:370-374. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001340

8. Brunner M, Veness MJ, Ch‘ng S, et al. Distant metastases from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma—analysis of AJCC stage IV. Head Neck. 2013;35:72-75. doi: 10.1002/hed.22913

9. Hartman RI, Green AC, Gordon LG; . Sun protection among organ transplant recipients after participation in a skin cancer research study. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:842-844. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1164

10. Chan A-W, Fung K, Austin PC, et al. Improved keratinocyte carcinoma outcomes with annual dermatology assessment after solid organ transplantation: population-based cohort study. Am J Transplant. 2018;19:522-531. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14966

11. Hofbauer GF, Anliker M, Arnold A, et al. Swiss clinical practice guidelines for skin cancer in organ transplant recipients. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139:407-415. doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2014.14026

12. Ulrich C, Kanitakis J, Stockfleth E, et al. Skin cancer in organ transplant recipients—where do we stand today? Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2192-2198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02386.x

13. Chen SC, Pennie ML, Kolm P, et al. Diagnosing and managing cutaneous pigmented lesions: primary care physicians versus dermatologists. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:678-682. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00462.x

14. Ismail F, Mitchell L, Casabonne D, et al. Specialist dermatology clinics for organ transplant recipients significantly improve compliance with photoprotection and levels of skin cancer awareness. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:916-925. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07454.x

15. O‘Reilly Zwald F, Brown M. Skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: advances in therapy and management: part II. Management of skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:263-279. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.063

16. Vural A, A, Kirnap M, et al. Skin cancer risk awareness and sun-protective behavior among solid-organ transplant recipients. Exp Clin Transplant. 2018;16(suppl 1):203-207. doi: 10.6002/ect.TOND-TDTD2017.P65

17. Papier K, Gordon LG, Khosrotehrani K, et al. Increase in preventive behaviour by organ transplant recipients after sun protection information in a skin cancer surveillance clinic. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1195-1196. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16836

18. Wu SZ, Jiang P, DeCaro JE, et al. A qualitative systematic review of the efficacy of sun protection education in organ transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1238-1244.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.031

19. Blomberg M, He SY, Harwood C, et al; . Research gaps in the management and prevention of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1225-1233. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15950

20. Urwin HR, Jones PW, Harden PN, et al. Predicting risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer and premalignant skin lesions in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2009;87:1667-1671. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a5ce2e

21. Infusino SD, Loi C, Ravaioli GM, et al. Cutaneous complications of immunosuppression in 812 transplant recipients: a 40-year single center experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155:662-668. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.18.06091-1

22. Naldi L, Venturuzzo A, Invernizzi P. Dermatological complications after solid organ transplantation. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:185-212. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8657-9

23. Sunscreen FAQs. American Academy of Dermatology Web site. Accessed February 25, 2021. www.aad.org/media/stats/prevention-and-care/sunscreen-faqs

24. Vos M, Plasmeijer EI, van Bemmel BC, et al. Azathioprine to mycophenolate mofetil transition and risk of squamous cell carcinoma after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:853-859. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.03.012

25. Puza CJ, Myers SA, Cardones AR, et al. The impact of transplant rejection on cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in renal transplant recipients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;44:265-269. doi: 10.1111/ced.13699

26. Abikhair Burgo M, Roudiani N, Chen J, et al. Ruxolitinib inhibits cyclosporine-induced proliferation of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e120750. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.120750

27. Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: management of advanced and high-stage tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:249-261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.058

28. Askew DA, Mickan SM, Soyer HP, et al. Effectiveness of 5-fluorouracil treatment for actinic keratosis—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:453-463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04045.x

29. Salim A, Leman JA, McColl JH, et al. Randomized comparison of photodynamic therapy with topical 5-fluorouracil in Bowen‘s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:539-543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05033.x

30. Morton CA. A synthesis of the world‘s guidelines on photodynamic therapy for non-melanoma skin cancer. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:783-792. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.18.05896-0

31. Joly F, Deret S, Gamboa B, et al. Photodynamic therapy corrects abnormal cancer-associated gene expression observed in actinic keratosis lesions and induces a remodeling effect in photodamaged skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;S0923-1811(17)30775-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2018.05.002

32. Patel GK, Goodwin R, Chawla M, et al. Imiquimod 5% cream monotherapy for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen‘s disease): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1025-1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.055

33. Imiquimod. Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc.; 2019. Accessed August 6, 2019. http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/7077?cesid=aRo1Yh9sd0Q&searchUrl=%2Flco%2Faction%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Dimiquimod%26t%3Dname%26va%3Dimiquimod

34. Diclofenac. Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc.; 2019. Accessed August 6th, 2019. http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/1772965?cesid=5vTk7J3Vmvc&searchUrl=%2Flco%2Faction%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Ddiclofenac%26t%3Dname%26va%3Ddiclofenac

35. Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

36. Yiasemides E, Sivapirabu G, Halliday GM, et al. Oral nicotinamide protects against ultraviolet radiation-induced immunosuppression in humans. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:101-105. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn248

37. Otley CC, Stasko T, Tope WD, et al. Chemoprevention of nonmelanoma skin cancer with systemic retinoids: practical dosing and management of adverse effects. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:562-568. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32115.x

38. McKenna DB, Murphy GM. Skin cancer chemoprophylaxis in renal transplant recipients: 5 years of experience using low-dose acitretin. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:656-660. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02765.x

39. Capecitabine. Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc.; 2019. Accessed February 13, 2019. http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/6519?cesid=7WMsK72X7T7&searchUrl=%2Flco%2Faction%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Dcapecitabine%26t%3Dname%26va%3Dcapecitabine

40. Wollina U, Hansel G, Koch A, et al. Oral capecitabine plus subcutaneous interferon alpha in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:300-304. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0656-6

41. Zavattaro E, Veronese F, Landucci G, et al. Efficacy of topical imiquimod 3.75% in the treatment of actinic keratosis of the scalp in immunosuppressed patients: our case series. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31:285-289. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1590524

42. Neugebauer R, Su KA, Zhu Z, et al. Comparative effectiveness of treatment of actinic keratosis with topical fluorouracil and imiquimod in the prevention of keratinocyte carcinoma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:998-1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.024

43. Gupta AK, Paquet M. Network meta-analysis of the outcome ‚participant complete clearance in nonimmunosuppressed participants of eight interventions for actinic keratosis: a follow-up on a Cochrane review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:250-259. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12343

44. Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

45. Bangash HK, Colegio OR. Management of non-melanoma skin cancer in immunocompromised solid organ transplant recipients. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13:354-376. doi: 10.1007/s11864-012-0195-3

46. Ulrich C, Johannsen A, J, et al. Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled safety and efficacy study of topical diclofenac 3% gel in organ transplant patients with multiple actinic keratoses. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:482-488. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1010

47. Ulrich C, Hackethal M, Ulrich M, et al. Treatment of multiple actinic keratoses with topical diclofenac 3% gel in organ transplant recipients: a series of six cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(suppl 3):40-42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07864.x

48. Wu Y, Tang N, Cai L, et al. Relative efficacy of 5-fluorouracil compared with other treatments among patients with actinic keratosis: a network meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12822. doi: 10.1111/dth.12822

49. Stockfleth E, Kerl H, Zwingers T, et al. Low-dose 5-fluorouracil in combination with salicylic acid as a new lesion-directed option to treat topically actinic keratoses: histological and clinical study results. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:1101-1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10387.x

50. Smith SR, Morhenn VB, Piacquadio DJ. Bilateral comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of 3% diclofenac sodium gel and 5% 5-fluorouracil cream in the treatment of actinic keratoses of the face and scalp. J Drug Dermatol. 2006;5:156-159.

51. Nichols AJ, Allen AH, Shareef S, et al. Association of human papillomavirus vaccine with the development of keratinocyte carcinomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:571-574. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5703

52. Nichols AJ, Gonzalez A, Clark ES, et al. Combined systemic and intratumoral administration of human papillomavirus vaccine to treat multiple cutaneous basaloid squamous cell carcinomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:927-930. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1748

53. Rousseau B, Guillemin A, Duvoux C, et al. Optimal oncologic management and mTOR inhibitor introduction are safe and improve survival in kidney and liver allograft recipients with de novo carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:886-896. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31769

54. Mathew T, Kreis H, Friend P. Two-year incidence of malignancy in sirolimus-treated renal transplant recipients: results from five multicenter studies. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:446-449. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00188.x

55. Euvrard S, Morelon E, Rostaing L, et al; Sirolimus and secondary skin-cancer prevention in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:329-339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204166

56. Hoogendijk-van den Akker JM, Harden PN, Hoitsma AJ, et al. Two-year randomized controlled prospective trial converting treatment of stable renal transplant recipients with cutaneous invasive squamous cell carcinomas to sirolimus. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1317-1323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6376

57. Karia PS, Azzi JR, Heher EC, et al. Association of sirolimus use with risk for skin cancer in a mixed-organ cohort of solid-organ transplant recipients with a history of cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:533-540. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5548

58. Stratigos A, Garbe C, Lebbe C, et al; . Diagnosis and treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1989-2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.110

59. Goldman G. The current status of curettage and electrodesiccation. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:569-578, ix. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00022-0

60. Stasko T, Brown MD, Carucci JA, et al; ; . Guidelines for the management of squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients. Derm Surg. 2004;30:642-650. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30150.x

61. Telfer NR, Colver GB, Morton CA; . Guidelines for the management of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:35-48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08666.x

The incidence of posttransplant malignancy among solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) is 10%; skin cancer, primarily nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), constitutes 49.5% of all malignancies in this population.1 The etiology of the increased risk of cutaneous malignancy in SOTR is multifactorial:

- The skin of SOTRs is photosensitive, compared to that of immunocompetent patients, thus predisposing SOTRs to carcinogenic damage resulting from exposure to UV light.2

- Immunosuppression plays a key role in increasing the risk of cutaneous malignancy by inhibiting the ability of the immune system to recognize and destroy tumor cells.3

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) can play a role in carcinogenesis by promoting molecular pathways to proliferation and survival of nascent tumor cells4;Times New Romanβ-HPV strains are disseminated ubiquitously in the skin of immunosuppressed patients.5

- Some medications administered after transplantation can be directly carcinogenic.

NMSC in SOTRs also differs qualitatively from NMSC in immunocompetent patients. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) (FIGUREs 1 and 2) is the most common skin cancer among SOTRs, whereas basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer in the general population.3 cSCC in the SOTR population tends to be more aggressive, with more rapid local invasion and an increased rate of both in-transit and distant metastases, leading to an increase in morbidity and mortality. Mortality of metastatic cSCC among SOTRs is approximately 50%, compared to 20% in an otherwise healthy population.3,6-8

The problem is relevant to primary care

Screening. Because there is a demonstrated reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with early detection and treatment of NMSC, regular screening of skin is important in the SOTR population.9 A study in Ontario, Canada, from 1994 to 2012 and comprising 10,183 SOTRs, found that adherence to an annual skin check regimen for ≥ 75% of the observation period was associated with a 34% reduction in cutaneous BCC- and cSCC-related morbidity or death (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48-0.92).10 Although routine follow-up with a dermatologist is recommended for SOTRs,9,11-15 only 2.1% of patients in the Canadian study were fully adherent with annual skin examination, and 55% never visited a dermatologist.10 Consequently, primary care physicians can play a key role in skin cancer screening for SOTRs.

Education regarding the importance of protection from the sun is also an essential part of primary care. A 2018 study of SOTRs in Turkey demonstrated that16

- 46% expressed a lack of knowledge of the hazards of sun exposure

- 44% did not recall ever receiving medical advice regarding sun protection

- 89% did not wear sun-protective clothing

- 86% did not use sunscreen daily.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the positive effect that preventive education and attendance at a dermatology or skin cancer screening clinic can have on sun-protective behaviors among SOTRs.9,16-18 In the Turkish study, 100% of patients who reported using sunscreen daily had been undergoing regular dermatologic examination.16

In this article, we review current management guidelines regarding the prevention and treatment of NMSC in SOTRs.

Recommendations for prevention

Screening skin exams (TABLE 11,11,12,15,19-23). Although definitive guidelines do not exist regarding the frequency of a screening skin exam for SOTRs, multiple frequency-determining algorithms have been proposed.11,12,15,19 The recommended frequency of a skin exam is based on history of skin cancer; for SOTRs, the most common recommendation19 is a full-body skin examination as follows:

- annually—when there is no history of skin cancer

- every 6 months—when there is a history of actinic keratoses (AKs; precancerous lesions that carry a risk of transforming into cSCC) or a single low-risk NMSC

- every 3 months—when there is a history of multiple NMSCs or a single high-risk NMSC

- every 1 to 3 months—when there is a history of metastatic disease.

Continue to: Other risk factors...

Other risk factors for NMSC to consider in SOTRs when determining an appropriate follow-up regimen include any of the following1,20,21,24-26:

- male gender, fair skin, history of childhood sunburn, history of smoking

- lung or heart transplantation, history of episodes of transplant rejection, age ≥ 50 years at transplantation

- immunosuppression with calcineurin inhibitors, compared to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors

- immunosuppression with cyclosporine, compared to tacrolimus

- an immunosuppressive regimen with > 1 immunosuppressant or an increased degree of immunosuppression

- antithymocyte globulin within the first year posttransplantation.

Because the intensity of immunosuppression and individual immunosuppressants used affect the risk of NMSC, conduct a thorough medication review with SOTRs at all visits. Ask about new, changing, or symptomatic (pruritic, painful, bleeding) skin lesions, and perform a full-body skin exam. Palpate draining lymph nodes if the patient has a history of NMSC.15 AKs (FIGURE 3) should be treated aggressively with liquid nitrogen or field therapy. Lesions suspicious for NMSC should be biopsied and sent for histologic evaluation.22 Shave, punch, and excisional biopsies are all adequate techniques; however, because all cSCCs in SOTRs are considered high risk for aggressive features, biopsy should extend at least into the reticular dermis to allow evaluation for invasive disease.22

Sun-protective measures (TABLE 11,11,12,15,19-23). Inquire about patients’ habits related to protection from the sun, their knowledge of recommended sun-protective measures, and risks associated with nonadherence. Recommended sun-protective measures include

- daily broad-spectrum sunscreen (SPF ≥ 30), reapplied every 2 hours of sun exposure, in accordance with labeling instructions23

- sun-protective clothing (pants, long sleeves, hat, sunglasses)23

- avoidance of tanning salons.15

SOTRs who adequately adhere to sun-protective measures might need vitamin D supplementation because sunscreen and sun-protective clothing inhibit cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D.15

Recommendations for treatment

Consider chemoprophylactic therapy for SOTRs who have had multiple prior cutaneous malignancies or multiple AKs.

Continue to: Topical chemoprophylaxis

Topical chemoprophylaxis

Topical medications used for cSCC chemoprophylaxis include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), photodynamic therapy (PDT), imiquimod, ingenol mebutate, topical retinoids, and diclofenac.27 (See TABLE 2.27-40) Of these, the latter 3 are used less commonly because of the small packaging size of ingenol mebutate and the relative lack of efficacy data for topical retinoids and diclofenac.27 Imiquimod is often avoided when treating large surface areas because of the risk of systemic adverse effects associated with cytokine release.27

5-FU is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of AKs, and is used off-label for treating cSCC in situ (Bowen disease). It is the most commonly used topical therapy for field disease.27-29 5-FU is typically applied once or twice daily for 3 to 4 weeks. Common adverse effects include transient skin irritation and erythema.27

PDT involves topical application of a photosensitizer, such as 5-aminolevulinic acid or methyl aminolevulinate, followed by exposure to a visible light source, leading to antitumor effects on gene expression and destruction of proliferating cells through production of reactive oxygen species.30,31 Evidence is sufficient to support routine use of PDT for AKs and Bowen disease.30 A mild sunburn-like reaction is common following PDT, with transient erythema and discomfort typically lasting 1 to 2 weeks but not typically necessitating analgesic therapy.27

Imiquimod is a ligand that binds to and activates Toll-like receptor 7, leading to enhancement of the cell-mediated antitumor immune response and resultant tissue-specific apoptosis coordinated by type 1 T-helper lymphocytes.32 Topical imiquimod cream is FDA approved for field treatment of AKs at 2.5%, 3.75%, and 5% concentrations; efficacy has been demonstrated in the SOTR population.33,41 Multiple studies in immunocompetent patients have suggested that imiquimod might be slightly less efficacious than 5-FU.42-44

The tolerability of field treatment with imiquimod has been called into question.27 However, in a 2019 study comparing adverse reactions among 513 immunocompetent patients with field disease who were treated with either 5-FU 5% cream; imiquimod 5% cream; PDT with methyl aminolevulinate; or ingenol mebutate 0.015% gel, a similar or smaller percentage of patients treated with imiquimod reported moderate-to-severe itching, moderate-to-severe pain, and any adverse events, compared to patients treated with the other options.44

Continue to: Diclofenac

Diclofenac is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug that reversibly inhibits the enzymes cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2, resulting in a decrease in the formation of inflammatory prostaglandins, which have been observed in chronically sun-damaged skin, AKs, and cSCC.34,45 Diclofenac 3% gel, applied topically twice daily for 60 to 90 days has been approved by the FDA for treatment of AKs, in conjunction with sun avoidance.34 Topical diclofenac has been demonstrated to be efficacious in treating AKs in the SOTR population46,47; however, multiple meta-analyses using data from immunocompetent patients have demonstrated that topical diclofenac is inferior to other treatment options, particularly 5-FU, at achieving complete clearance of AKs.43,48,49 Diclofenac might be a useful option when patient adherence is expected to be difficult because of adverse effects of therapy: Multiple studies have suggested that diclofenac might be more tolerable than other options.43,48,50

Systemic chemoprophylaxis

Systemic therapies that have been used for chemoprophylaxis against cutaneous malignancy include nicotinamide, oral retinoids, capecitabine, and HPV vaccination. (See TABLE 2.27-40)

Nicotinamide, the amide form of vitamin B3, protects against cutaneous malignancy by aiding repair of DNA damaged by ionizing radiation, such as UV light.27 Efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing development of new AKs and cSCC in immunocompetent patients with a history of more than 2 keratinocyte carcinomas within a 5-year span.27,35 Nicotinamide is especially relevant to the SOTR population because it reduces the level of cutaneous immunity suppression induced by UV radiation without altering patients’ baseline immunity.27,36

There are insufficient long-term follow-up data in the literature to assess the sustainability of the antitumor effects of nicotinamide; studies specific to the SOTR population have been underpowered for assessing its impact on formation of cSCC.27,35Patients taking nicotinamide should be informed of the risk of liver failure at dosages > 3 g/d (antitumor efficacy has been demonstrated at 500 mg twice daily) and advised to avoid purchasing over-the-counter nicotinic acid or niacin as a substitute for nicotinamide, because of the increased incidence of flushing associated with their use.27

Oral retinoids. Systemic retinoids—in particular, acitretin—are efficacious in reducing the risk of cSCC in SOTRs.27,37,38 The primary drawback to cSCC prophylaxis with oral retinoids is a rebound effect, in which treatment discontinuation leads to a rapid return to baseline cSCC formation.27

Continue to: Pregnancy must be avoided...

Pregnancy must be avoided while taking an oral retinoid. Because acitretin can persist in the body for years after discontinuation, its use should generally be avoided in patients of childbearing potential. An FDA black box warning states that patients of childbearing potential must be counseled to use 2 forms of birth control to avoid pregnancy for ≥ 3 years after cessation of oral acitretin. Prior to initiation of oral retinoid therapy, the following baseline laboratory tests should be obtained: complete blood count, creatinine, lipid panel, and liver function tests. For patients with a history of chronic kidney disease or renal transplantation, the lipid panel, liver function tests, and creatinine assay should be repeated with each dosage adjustment and every 3 months once goal-dosing is achieved.27

Capecitabine is typically initiated with the help of Medical Oncology.27,40 A prodrug metabolized by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase to 5-FU, capecitabine interacts with warfarin, leading to a significant increase in prothrombin time.39 Other adverse effects associated with oral capecitabine include fatigue, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, diarrhea, and, rarely, neutropenia. Although dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency is rare, treatment with capecitabine in patients who have this enzyme deficiency might lead to severe toxicity or death.27

HPV vaccination. HPV might play a role in the development of cutaneous malignancy, especially in immunosuppressed patients.4,5 The utility of HPV vaccination in the prevention of NMSC has yet to be determined, but vaccination has been shown, in case reports, to be helpful in immunocompetent patients.51,52 The immunogenicity of HPV vaccination in the SOTR population is uncertain, and the most common HPV types found in SOTRs are not specifically covered by available HPV vaccines.19

The role of immunosuppression reduction and immunosuppressive replacement

Both the degree of immunosuppression and the individual agents used can affect a patient’s risk of NMSC. Immunosuppression reduction should be considered if skin cancer poses a major risk to the patient’s health and if that risk outweighs the risk of graft rejection associated with immunosuppression reduction.27 In a cohort of 180 kidney and liver SOTRs who developed de novo carcinoma (excluding NMSC) after transplantation, neither reduction of immunosuppression nor introduction of an mTOR inhibitor affected graft survival or oncologic treatment tolerance.53 Because mTOR inhibitors have a protective effect against development of NMSC, they are the preferred choice of immunosuppressive agent from a dermatologic perspective.1,27,54-57 Decisions regarding changes in immunosuppression are generally made by, or in collaboration with, the patient’s transplant physician.

Recommendations: Treating cSCC

Risk should guide strategy

Small lesions of the trunk and extremities without high-risk features can be treated with a destructive method (eg, electrodessication and curettage). However, lesions of the head and neck and those found to have features consistent with an increased risk of recurrence or metastasis should be treated aggressively.3,58,59

Continue to: Risk factors for invasive growth...

Risk factors for invasive growth, recurrence, or metastasis of cSCC in SOTRs are multiple lesions or satellite lesions, indistinct clinical borders, rapid growth, ulceration, and recurrence after treatment.60 The risk of invasive growth, recurrence, and metastasis of cSCC also increases with size and location of the lesion, according to this framework60:

- any size in scar tissue, areas of chronic inflammation, and fields of prior radiation therapy

- ≥ 0.6 cm on hands, feet, genitalia, and mask areas of the face (central face, eyelids, eyebrows, nose, lips, chin, mandible, and temporal, preauricular, postauricular, and periorbital areas)

- > 1 cm on cheeks, forehead, neck, and scalp

- > 2 cm on the trunk and extremities.

In addition, specific findings on histologic analysis portend increased risk of invasive growth, recurrence, or metastasis:

- poor differentiation

- deep extension of the tumor into subcutaneous fat

- perineural invasion or inflammation

- perivascular or intravascular invasion.

Treatment modalities

Mohs surgery is preferred to ensure margin clearance while preserving noninvolved tissue3,7 (FIGURE 4). If Mohs surgery is not possible, the lesion should be excised with 3- to 10-mm margins.3,60 Based on current literature, the roles of nodal staging, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and adjuvant therapy are not well defined, but it is likely that these interventions will play a pivotal role in the management of advanced cSCC in SOTRs in the future.3

Nonsurgical therapeutic options for primary or adjuvant treatment of cSCC include systemic chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors. (For more on treatment modalities, see TABLE 3.3,7,58-61)

Recommendations: Treating BCC

BCC in SOTRs is treated similarly (TABLE 33,7,58-61) to how it is treated in the immunocompetent population—except that SOTRs require closer follow-up than nontransplant patients because they are at higher risk of recurrence and new NMSCs.3 Standard management after biopsy is either3,61:

- Mohs surgery to ensure margin control (for most BCCs on the head and neck and those with clinical or histologic risk factors for recurrence or aggressive behavior)

- excision with a 4- or 5-mm margin or a destructive modality (for BCCs on the trunk and extremities without risk factors for recurrence).

Radiotherapy is an alternative for patients with high-risk BCCs who are unable to tolerate surgery.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Lindsey Collins, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 619 NE 13th Steet, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; Lindsey-Collins@ouhsc.edu

The incidence of posttransplant malignancy among solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) is 10%; skin cancer, primarily nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), constitutes 49.5% of all malignancies in this population.1 The etiology of the increased risk of cutaneous malignancy in SOTR is multifactorial:

- The skin of SOTRs is photosensitive, compared to that of immunocompetent patients, thus predisposing SOTRs to carcinogenic damage resulting from exposure to UV light.2

- Immunosuppression plays a key role in increasing the risk of cutaneous malignancy by inhibiting the ability of the immune system to recognize and destroy tumor cells.3

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) can play a role in carcinogenesis by promoting molecular pathways to proliferation and survival of nascent tumor cells4;Times New Romanβ-HPV strains are disseminated ubiquitously in the skin of immunosuppressed patients.5

- Some medications administered after transplantation can be directly carcinogenic.

NMSC in SOTRs also differs qualitatively from NMSC in immunocompetent patients. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) (FIGUREs 1 and 2) is the most common skin cancer among SOTRs, whereas basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer in the general population.3 cSCC in the SOTR population tends to be more aggressive, with more rapid local invasion and an increased rate of both in-transit and distant metastases, leading to an increase in morbidity and mortality. Mortality of metastatic cSCC among SOTRs is approximately 50%, compared to 20% in an otherwise healthy population.3,6-8

The problem is relevant to primary care

Screening. Because there is a demonstrated reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with early detection and treatment of NMSC, regular screening of skin is important in the SOTR population.9 A study in Ontario, Canada, from 1994 to 2012 and comprising 10,183 SOTRs, found that adherence to an annual skin check regimen for ≥ 75% of the observation period was associated with a 34% reduction in cutaneous BCC- and cSCC-related morbidity or death (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48-0.92).10 Although routine follow-up with a dermatologist is recommended for SOTRs,9,11-15 only 2.1% of patients in the Canadian study were fully adherent with annual skin examination, and 55% never visited a dermatologist.10 Consequently, primary care physicians can play a key role in skin cancer screening for SOTRs.

Education regarding the importance of protection from the sun is also an essential part of primary care. A 2018 study of SOTRs in Turkey demonstrated that16

- 46% expressed a lack of knowledge of the hazards of sun exposure

- 44% did not recall ever receiving medical advice regarding sun protection

- 89% did not wear sun-protective clothing

- 86% did not use sunscreen daily.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the positive effect that preventive education and attendance at a dermatology or skin cancer screening clinic can have on sun-protective behaviors among SOTRs.9,16-18 In the Turkish study, 100% of patients who reported using sunscreen daily had been undergoing regular dermatologic examination.16

In this article, we review current management guidelines regarding the prevention and treatment of NMSC in SOTRs.

Recommendations for prevention

Screening skin exams (TABLE 11,11,12,15,19-23). Although definitive guidelines do not exist regarding the frequency of a screening skin exam for SOTRs, multiple frequency-determining algorithms have been proposed.11,12,15,19 The recommended frequency of a skin exam is based on history of skin cancer; for SOTRs, the most common recommendation19 is a full-body skin examination as follows:

- annually—when there is no history of skin cancer

- every 6 months—when there is a history of actinic keratoses (AKs; precancerous lesions that carry a risk of transforming into cSCC) or a single low-risk NMSC

- every 3 months—when there is a history of multiple NMSCs or a single high-risk NMSC

- every 1 to 3 months—when there is a history of metastatic disease.

Continue to: Other risk factors...