User login

Why Is There a Lack of Representation of Skin of Color in the COVID-19 Literature?

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a striking paucity of representations of patients with skin of color (SOC) in the dermatology literature. Was COVID-19 underdiagnosed in this patient population due to a lack of patient-centered resources and inadequate dermatology training; reduced access to care, resulting from social determinants of health and reduced skin-color concordance; or the absence of population-based prevalence studies?

Tan et al1 reviewed 51 articles describing skin findings secondary to COVID-19. Patients were stratified by country of origin, which yielded an increased prevalence of cutaneous manifestations among Americans and Europeans compared to Asians, but patients were not stratified by race.1 However, in one case series of 318 predominantly American patients, 89% were White and 0.7% were Black.2 This systematic review by Tan et al1 suggested that skin manifestations of COVID-19 were present in patients with SOC but less frequently than in White patients. However, case series are not a strong proxy for population-level prevalence.

More broadly, patients with SOC are underrepresented in Google image search results, as the medical resource websites (eg, DermNet [https://dermnetnz.org], MedicalNewsToday [www.medicalnewstoday.com], and Healthline [www.healthline.com]) are lacking these images.3 As a result, it is difficult for patients with SOC to recognize diseases presenting in darker skin types. This same tendency may exist for COVID-19 skin manifestations. A systematic review found that articles describing cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 almost exclusively presented images of lighter skin and completely omitted darker skin.4 If images of patients with SOC are absent from online resources, it is increasingly unlikely for these patients to recognize if their skin lesions are associated with COVID-19, which may result in a decrease in the number of patients with SOC presenting with skin lesions secondary to COVID-19, thereby influencing the representation of patients with SOC in case studies.

The lack of representation of SOC in online resources mirrors the paucity of images in dermatology textbooks. According to a search of 7170 images in major dermatology textbooks, most images depicted light or white skin (80.6%), followed by medium or brown skin in 15.5% of images and dark or black skin in only 3.9%.5 Physicians rely on online and print resources for making diagnoses; inadequate resources highlight a component of a larger issue: inadequate training of dermatologists in SOC. In a survey of American dermatologists and dermatology residents (N=262), 47% thought that their medical education had not adequately trained them on skin conditions in Black patients.6

A lack of adequate training for dermatologists may decrease the rate of correct diagnosis of skin lesions secondary to COVID-19 in patients with SOC. A lack of trust in the health care system and social determinants of health may hinder patients with SOC from seeking medical help. Dermatology is the second least diverse of medical specialties; only 3% of dermatologists are Black.7 This is impactful: First, because minority physicians are increasingly likely to provide care for patients of the same race or background, and second, because race-concordant physician visits are associated with greater patient-reported positive affect.7 A lack of availability of race-concordant physicians or physicians with perceived cultural competence may deter patients with SOC from seeking help, which may be further prevalent in dermatologic practice.

Barriers at all levels of social determinants of health hinder access to health care. Patients with SOC experience greater housing insecurity, increased reliance on public transportation, more issues with health literacy, and limited English-language fluency.8 Combined, these factors equate to decreased access to health care resources and subsequently a lack of inclusion in case studies.

COVID-19 infection disproportionately affects patients with SOC,8 but there is a clear lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 dermatology literature. It is imperative to investigate factors that may contribute to this inequity. Recognizing skin manifestations can play a role in diagnosing COVID-19; increased awareness of its presentation in darker skin types may help bridge existing racial inequities. It is vital that physicians receive adequate resources and training to be able to recognize cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in all skin types. Finally, it is important to recognize that the lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 literature represents a larger trend that exists in dermatologic research that warrants further investigation and advocacy for inclusivity.

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2020.12.003

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dematol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Fathy R, Lipoff JB. Lack of skin of color in Google image searches may reflect under-representation in all educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E113-E114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.097

- Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, et al. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:593-595. doi:10.1111/bjd.19258

- Kamath P, Sundaram N, Morillo-Hernandez C, et al. Visual racism in internet searches and dermatology textbooks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1348-1349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.072

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, et al. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:703-706. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa815

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a striking paucity of representations of patients with skin of color (SOC) in the dermatology literature. Was COVID-19 underdiagnosed in this patient population due to a lack of patient-centered resources and inadequate dermatology training; reduced access to care, resulting from social determinants of health and reduced skin-color concordance; or the absence of population-based prevalence studies?

Tan et al1 reviewed 51 articles describing skin findings secondary to COVID-19. Patients were stratified by country of origin, which yielded an increased prevalence of cutaneous manifestations among Americans and Europeans compared to Asians, but patients were not stratified by race.1 However, in one case series of 318 predominantly American patients, 89% were White and 0.7% were Black.2 This systematic review by Tan et al1 suggested that skin manifestations of COVID-19 were present in patients with SOC but less frequently than in White patients. However, case series are not a strong proxy for population-level prevalence.

More broadly, patients with SOC are underrepresented in Google image search results, as the medical resource websites (eg, DermNet [https://dermnetnz.org], MedicalNewsToday [www.medicalnewstoday.com], and Healthline [www.healthline.com]) are lacking these images.3 As a result, it is difficult for patients with SOC to recognize diseases presenting in darker skin types. This same tendency may exist for COVID-19 skin manifestations. A systematic review found that articles describing cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 almost exclusively presented images of lighter skin and completely omitted darker skin.4 If images of patients with SOC are absent from online resources, it is increasingly unlikely for these patients to recognize if their skin lesions are associated with COVID-19, which may result in a decrease in the number of patients with SOC presenting with skin lesions secondary to COVID-19, thereby influencing the representation of patients with SOC in case studies.

The lack of representation of SOC in online resources mirrors the paucity of images in dermatology textbooks. According to a search of 7170 images in major dermatology textbooks, most images depicted light or white skin (80.6%), followed by medium or brown skin in 15.5% of images and dark or black skin in only 3.9%.5 Physicians rely on online and print resources for making diagnoses; inadequate resources highlight a component of a larger issue: inadequate training of dermatologists in SOC. In a survey of American dermatologists and dermatology residents (N=262), 47% thought that their medical education had not adequately trained them on skin conditions in Black patients.6

A lack of adequate training for dermatologists may decrease the rate of correct diagnosis of skin lesions secondary to COVID-19 in patients with SOC. A lack of trust in the health care system and social determinants of health may hinder patients with SOC from seeking medical help. Dermatology is the second least diverse of medical specialties; only 3% of dermatologists are Black.7 This is impactful: First, because minority physicians are increasingly likely to provide care for patients of the same race or background, and second, because race-concordant physician visits are associated with greater patient-reported positive affect.7 A lack of availability of race-concordant physicians or physicians with perceived cultural competence may deter patients with SOC from seeking help, which may be further prevalent in dermatologic practice.

Barriers at all levels of social determinants of health hinder access to health care. Patients with SOC experience greater housing insecurity, increased reliance on public transportation, more issues with health literacy, and limited English-language fluency.8 Combined, these factors equate to decreased access to health care resources and subsequently a lack of inclusion in case studies.

COVID-19 infection disproportionately affects patients with SOC,8 but there is a clear lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 dermatology literature. It is imperative to investigate factors that may contribute to this inequity. Recognizing skin manifestations can play a role in diagnosing COVID-19; increased awareness of its presentation in darker skin types may help bridge existing racial inequities. It is vital that physicians receive adequate resources and training to be able to recognize cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in all skin types. Finally, it is important to recognize that the lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 literature represents a larger trend that exists in dermatologic research that warrants further investigation and advocacy for inclusivity.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a striking paucity of representations of patients with skin of color (SOC) in the dermatology literature. Was COVID-19 underdiagnosed in this patient population due to a lack of patient-centered resources and inadequate dermatology training; reduced access to care, resulting from social determinants of health and reduced skin-color concordance; or the absence of population-based prevalence studies?

Tan et al1 reviewed 51 articles describing skin findings secondary to COVID-19. Patients were stratified by country of origin, which yielded an increased prevalence of cutaneous manifestations among Americans and Europeans compared to Asians, but patients were not stratified by race.1 However, in one case series of 318 predominantly American patients, 89% were White and 0.7% were Black.2 This systematic review by Tan et al1 suggested that skin manifestations of COVID-19 were present in patients with SOC but less frequently than in White patients. However, case series are not a strong proxy for population-level prevalence.

More broadly, patients with SOC are underrepresented in Google image search results, as the medical resource websites (eg, DermNet [https://dermnetnz.org], MedicalNewsToday [www.medicalnewstoday.com], and Healthline [www.healthline.com]) are lacking these images.3 As a result, it is difficult for patients with SOC to recognize diseases presenting in darker skin types. This same tendency may exist for COVID-19 skin manifestations. A systematic review found that articles describing cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 almost exclusively presented images of lighter skin and completely omitted darker skin.4 If images of patients with SOC are absent from online resources, it is increasingly unlikely for these patients to recognize if their skin lesions are associated with COVID-19, which may result in a decrease in the number of patients with SOC presenting with skin lesions secondary to COVID-19, thereby influencing the representation of patients with SOC in case studies.

The lack of representation of SOC in online resources mirrors the paucity of images in dermatology textbooks. According to a search of 7170 images in major dermatology textbooks, most images depicted light or white skin (80.6%), followed by medium or brown skin in 15.5% of images and dark or black skin in only 3.9%.5 Physicians rely on online and print resources for making diagnoses; inadequate resources highlight a component of a larger issue: inadequate training of dermatologists in SOC. In a survey of American dermatologists and dermatology residents (N=262), 47% thought that their medical education had not adequately trained them on skin conditions in Black patients.6

A lack of adequate training for dermatologists may decrease the rate of correct diagnosis of skin lesions secondary to COVID-19 in patients with SOC. A lack of trust in the health care system and social determinants of health may hinder patients with SOC from seeking medical help. Dermatology is the second least diverse of medical specialties; only 3% of dermatologists are Black.7 This is impactful: First, because minority physicians are increasingly likely to provide care for patients of the same race or background, and second, because race-concordant physician visits are associated with greater patient-reported positive affect.7 A lack of availability of race-concordant physicians or physicians with perceived cultural competence may deter patients with SOC from seeking help, which may be further prevalent in dermatologic practice.

Barriers at all levels of social determinants of health hinder access to health care. Patients with SOC experience greater housing insecurity, increased reliance on public transportation, more issues with health literacy, and limited English-language fluency.8 Combined, these factors equate to decreased access to health care resources and subsequently a lack of inclusion in case studies.

COVID-19 infection disproportionately affects patients with SOC,8 but there is a clear lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 dermatology literature. It is imperative to investigate factors that may contribute to this inequity. Recognizing skin manifestations can play a role in diagnosing COVID-19; increased awareness of its presentation in darker skin types may help bridge existing racial inequities. It is vital that physicians receive adequate resources and training to be able to recognize cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in all skin types. Finally, it is important to recognize that the lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 literature represents a larger trend that exists in dermatologic research that warrants further investigation and advocacy for inclusivity.

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2020.12.003

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dematol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Fathy R, Lipoff JB. Lack of skin of color in Google image searches may reflect under-representation in all educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E113-E114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.097

- Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, et al. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:593-595. doi:10.1111/bjd.19258

- Kamath P, Sundaram N, Morillo-Hernandez C, et al. Visual racism in internet searches and dermatology textbooks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1348-1349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.072

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, et al. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:703-706. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa815

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2020.12.003

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dematol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Fathy R, Lipoff JB. Lack of skin of color in Google image searches may reflect under-representation in all educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E113-E114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.097

- Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, et al. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:593-595. doi:10.1111/bjd.19258

- Kamath P, Sundaram N, Morillo-Hernandez C, et al. Visual racism in internet searches and dermatology textbooks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1348-1349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.072

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, et al. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:703-706. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa815

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

THE COMPARISON

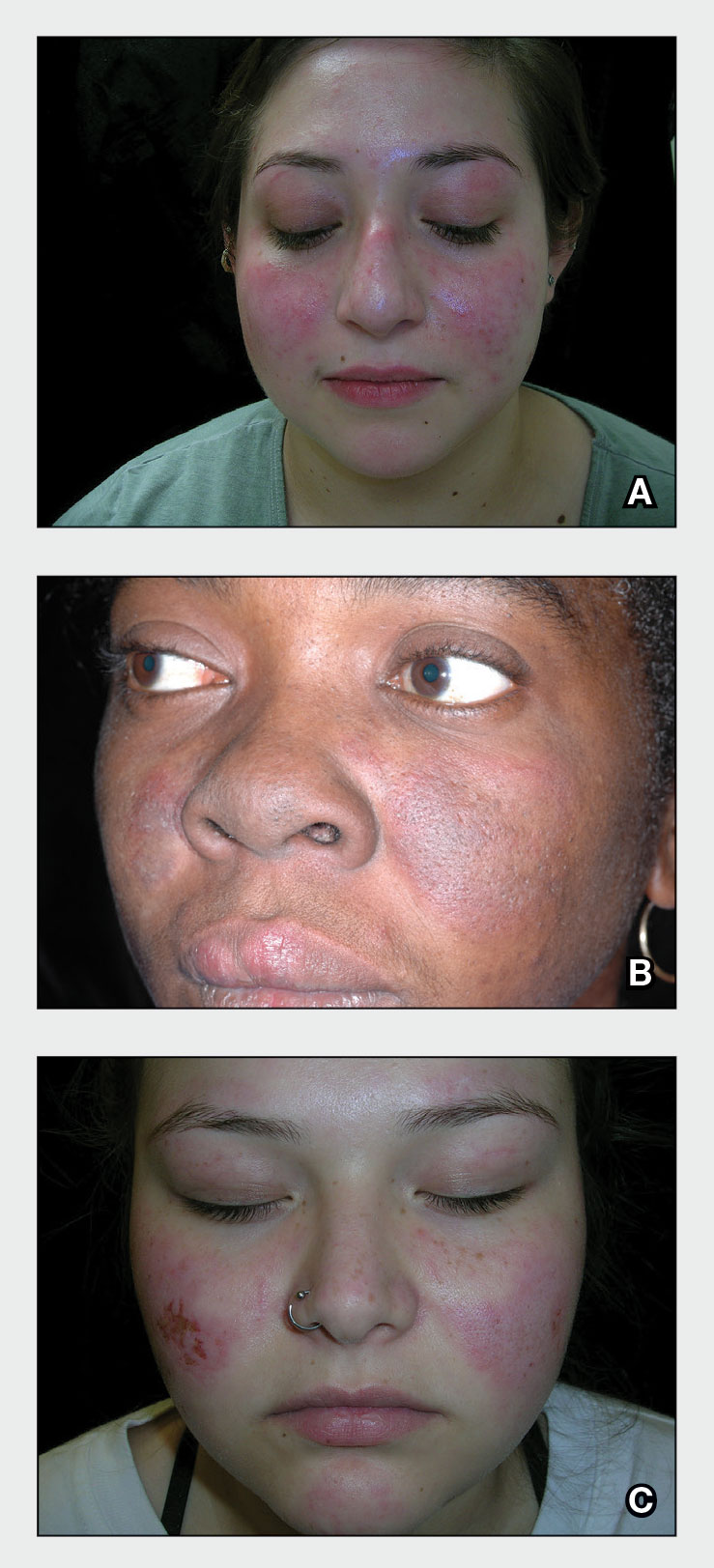

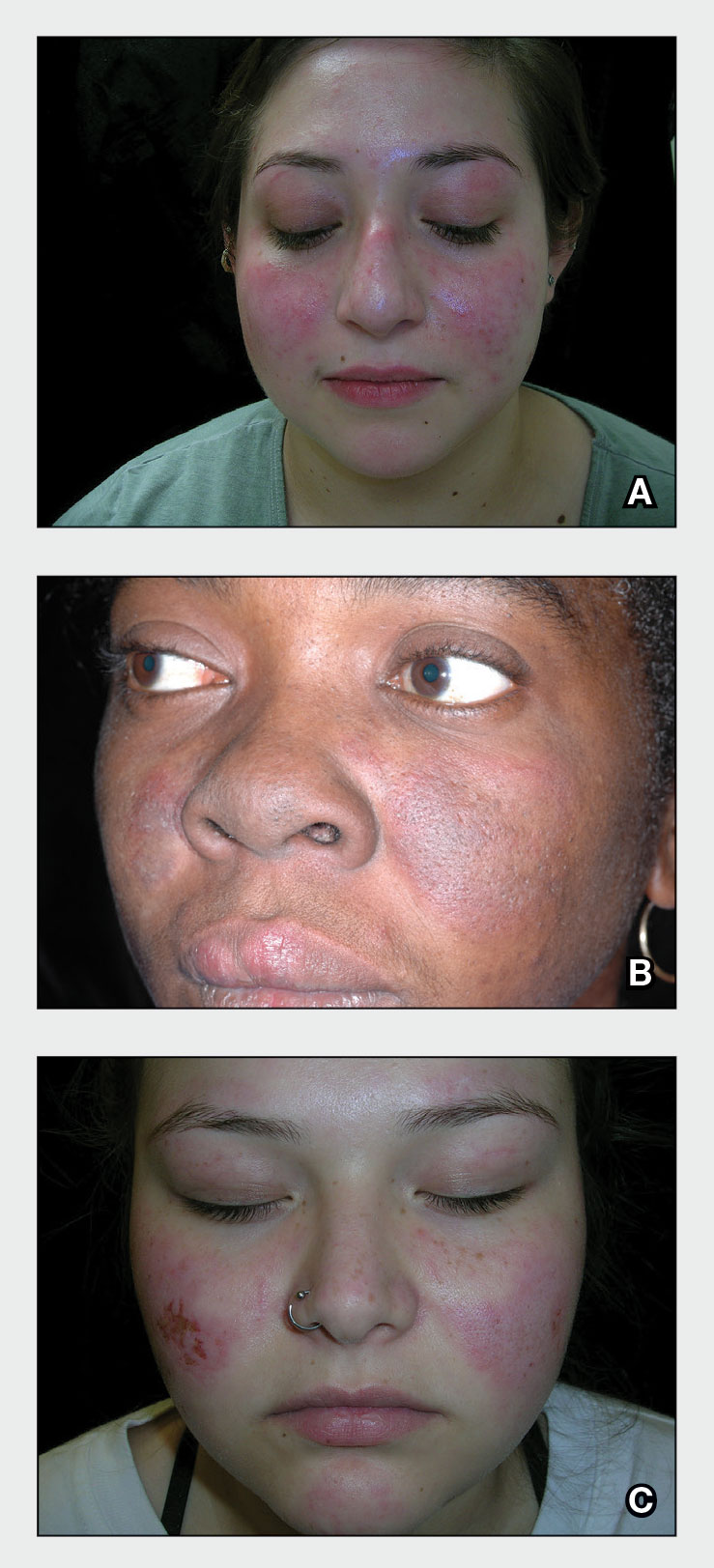

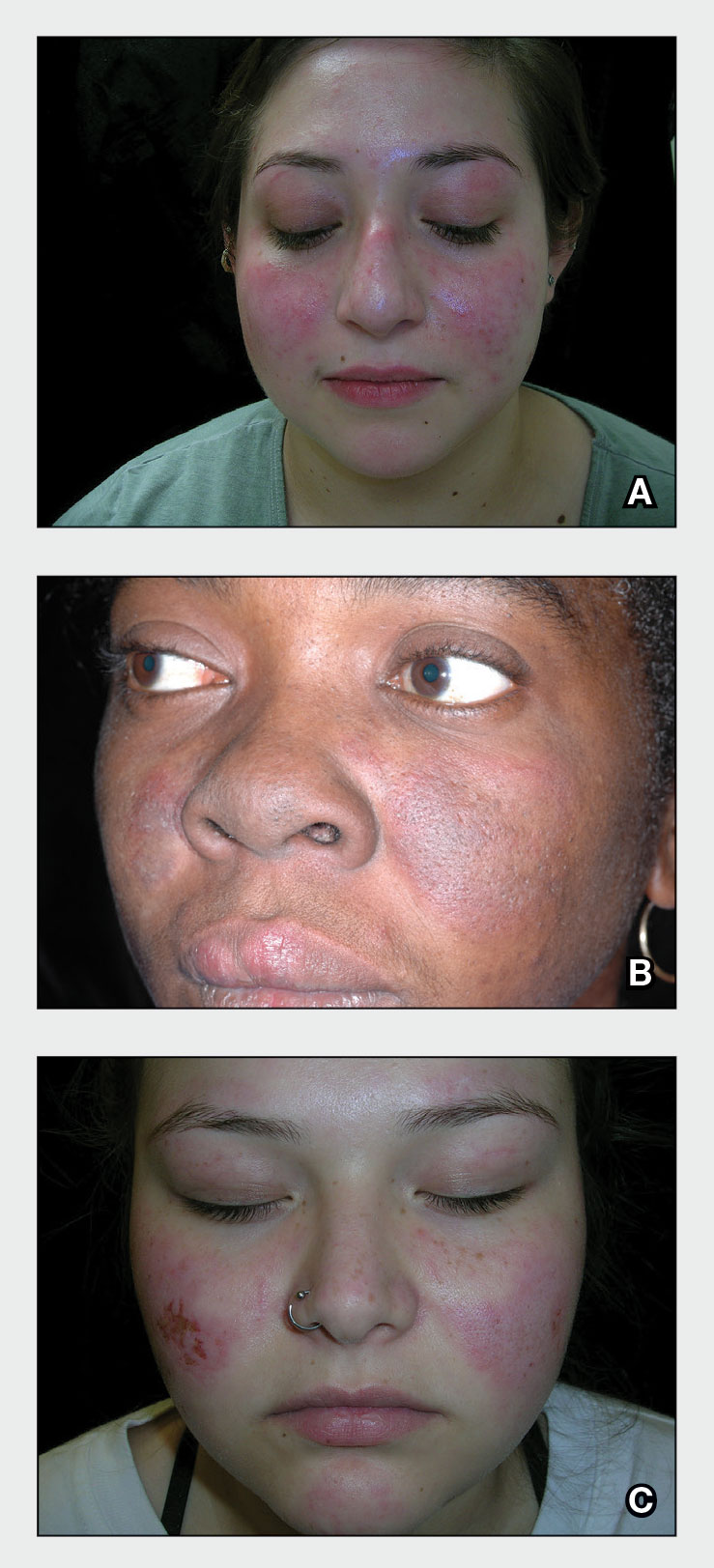

A A 23-year-old White woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds.

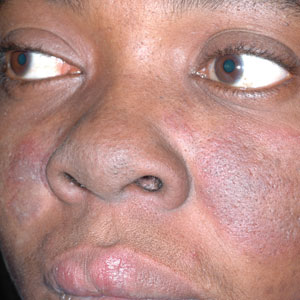

B A Black woman with malar erythema and hyperpigmentation from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The nasolabial folds are spared.

C A 19-year-old Latina woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose, chin, and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds. Cutaneous erosions are present on the right cheek as part of the lupus flare. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune condition that affects the kidneys, lungs, brain, and heart, though it is not limited to these organs. Dermatologists and primary care physicians play a critical role in the early identification of SLE, particularly in those with skin of color, as the standardized mortality rate is 2.6-fold higher in patients with SLE compared to the general population.1 The clinical manifestations of SLE vary.

Epidemiology

A meta-analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registry network including 5417 patients revealed a prevalence of 72.8 cases per 100,000 person-years.2 The prevalence was higher in females than males and highest among females identifying as Black. White and Asian/Pacific Islander females had the lowest prevalence. The American Indian (indigenous)/Alaska Native–identifying population had the highest race-specific SLE estimates among both females and males compared to other racial/ethnic groups.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The diagnosis of SLE is based on clinical and immunologic criteria from the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology.3,4 An antinuclear antibody titer of 1:80 or higher at least once is required for the diagnosis of SLE, as long as there is not another more likely diagnosis. If it is present, 22 additive weighted classification criteria are considered; each criterion is assigned points, ranging from 2 to 10. Patients with at least 1 clinical criterion and 10 or more points are classified as having SLE. If more than 1 of the criteria are met in a domain, then the one with the highest numerical value is counted.3,4 Aringer et al3,4 outline the criteria and numerical points to make the diagnosis of SLE. The mucocutaneous component of the SLE diagnostic criteria3,4 includes nonscarring alopecia, oral ulcers, subacute cutaneous or discoid lupus erythematosus,5 and acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, with acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus being the highest-weighted criterion in that domain. The other clinical domains are constitutional, hematologic, neuropsychiatric, serosal, musculoskeletal, renal, antiphosopholipid antibodies, complement proteins, and SLE-specific antibodies.3,4

The malar (“butterfly”) rash of SLE characteristically includes erythema that spares the nasolabial folds but affects the nasal bridge and cheeks.6 The rash occasionally may be pruritic and painful, lasting days to weeks. Photosensitivity occurs, resulting in rashes or even an overall worsening of SLE symptoms. In those with darker skin tones, erythema may appear violaceous or may not be as readily appreciated.6

Worth noting

• Patients with skin of color are at an increased risk for postinflammatory hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation (pigment alteration), hypertrophic scars, and keloids.7,8

• The mortality rate for those with SLE is high despite early recognition and treatment when compared to the general population.1,9

Health disparity highlight

Those at greatest risk for death from SLE in the United States are those of African descent, Hispanic individuals, men, and those with low socioeconomic status,9 which likely is primarily driven by social determinants of health instead of genetic patterns. Income level, educational attainment, insurance status, and environmental factors10 have far-reaching effects, negatively impacting quality of life and even mortality.

- Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, et al. Overall and cause-specific mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: an updated meta-analysis. Lupus. 2016;25:727-734.

- Izmirly PM, Parton H, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States: estimates from a meta-analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registries [published online April 23, 2021]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:991-996. doi:10.1002/art.41632

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412. doi:10.1002/art.40930

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1151-1159.

- Heath CR, Usatine RP. Discoid lupus. Cutis. 2022;109:172-173.

- Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al, eds. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 8th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

- Nozile W, Adgerson CH, Cohen GF. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:343-349.

- Cardinali F, Kovacs D, Picardo M. Mechanisms underlying postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: lessons for solar. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139(suppl 4):S148-S152.

- Ocampo-Piraquive V, Nieto-Aristizábal I, Cañas CA, et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: causes, predictors and interventions. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:1043-1053. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2018.1538789

- Carter EE, Barr SG, Clarke AE. The global burden of SLE: prevalence, health disparities and socioeconomic impact. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:605-620. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.137

THE COMPARISON

A A 23-year-old White woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds.

B A Black woman with malar erythema and hyperpigmentation from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The nasolabial folds are spared.

C A 19-year-old Latina woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose, chin, and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds. Cutaneous erosions are present on the right cheek as part of the lupus flare. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune condition that affects the kidneys, lungs, brain, and heart, though it is not limited to these organs. Dermatologists and primary care physicians play a critical role in the early identification of SLE, particularly in those with skin of color, as the standardized mortality rate is 2.6-fold higher in patients with SLE compared to the general population.1 The clinical manifestations of SLE vary.

Epidemiology

A meta-analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registry network including 5417 patients revealed a prevalence of 72.8 cases per 100,000 person-years.2 The prevalence was higher in females than males and highest among females identifying as Black. White and Asian/Pacific Islander females had the lowest prevalence. The American Indian (indigenous)/Alaska Native–identifying population had the highest race-specific SLE estimates among both females and males compared to other racial/ethnic groups.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The diagnosis of SLE is based on clinical and immunologic criteria from the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology.3,4 An antinuclear antibody titer of 1:80 or higher at least once is required for the diagnosis of SLE, as long as there is not another more likely diagnosis. If it is present, 22 additive weighted classification criteria are considered; each criterion is assigned points, ranging from 2 to 10. Patients with at least 1 clinical criterion and 10 or more points are classified as having SLE. If more than 1 of the criteria are met in a domain, then the one with the highest numerical value is counted.3,4 Aringer et al3,4 outline the criteria and numerical points to make the diagnosis of SLE. The mucocutaneous component of the SLE diagnostic criteria3,4 includes nonscarring alopecia, oral ulcers, subacute cutaneous or discoid lupus erythematosus,5 and acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, with acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus being the highest-weighted criterion in that domain. The other clinical domains are constitutional, hematologic, neuropsychiatric, serosal, musculoskeletal, renal, antiphosopholipid antibodies, complement proteins, and SLE-specific antibodies.3,4

The malar (“butterfly”) rash of SLE characteristically includes erythema that spares the nasolabial folds but affects the nasal bridge and cheeks.6 The rash occasionally may be pruritic and painful, lasting days to weeks. Photosensitivity occurs, resulting in rashes or even an overall worsening of SLE symptoms. In those with darker skin tones, erythema may appear violaceous or may not be as readily appreciated.6

Worth noting

• Patients with skin of color are at an increased risk for postinflammatory hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation (pigment alteration), hypertrophic scars, and keloids.7,8

• The mortality rate for those with SLE is high despite early recognition and treatment when compared to the general population.1,9

Health disparity highlight

Those at greatest risk for death from SLE in the United States are those of African descent, Hispanic individuals, men, and those with low socioeconomic status,9 which likely is primarily driven by social determinants of health instead of genetic patterns. Income level, educational attainment, insurance status, and environmental factors10 have far-reaching effects, negatively impacting quality of life and even mortality.

THE COMPARISON

A A 23-year-old White woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds.

B A Black woman with malar erythema and hyperpigmentation from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The nasolabial folds are spared.

C A 19-year-old Latina woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose, chin, and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds. Cutaneous erosions are present on the right cheek as part of the lupus flare. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune condition that affects the kidneys, lungs, brain, and heart, though it is not limited to these organs. Dermatologists and primary care physicians play a critical role in the early identification of SLE, particularly in those with skin of color, as the standardized mortality rate is 2.6-fold higher in patients with SLE compared to the general population.1 The clinical manifestations of SLE vary.

Epidemiology

A meta-analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registry network including 5417 patients revealed a prevalence of 72.8 cases per 100,000 person-years.2 The prevalence was higher in females than males and highest among females identifying as Black. White and Asian/Pacific Islander females had the lowest prevalence. The American Indian (indigenous)/Alaska Native–identifying population had the highest race-specific SLE estimates among both females and males compared to other racial/ethnic groups.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The diagnosis of SLE is based on clinical and immunologic criteria from the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology.3,4 An antinuclear antibody titer of 1:80 or higher at least once is required for the diagnosis of SLE, as long as there is not another more likely diagnosis. If it is present, 22 additive weighted classification criteria are considered; each criterion is assigned points, ranging from 2 to 10. Patients with at least 1 clinical criterion and 10 or more points are classified as having SLE. If more than 1 of the criteria are met in a domain, then the one with the highest numerical value is counted.3,4 Aringer et al3,4 outline the criteria and numerical points to make the diagnosis of SLE. The mucocutaneous component of the SLE diagnostic criteria3,4 includes nonscarring alopecia, oral ulcers, subacute cutaneous or discoid lupus erythematosus,5 and acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, with acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus being the highest-weighted criterion in that domain. The other clinical domains are constitutional, hematologic, neuropsychiatric, serosal, musculoskeletal, renal, antiphosopholipid antibodies, complement proteins, and SLE-specific antibodies.3,4

The malar (“butterfly”) rash of SLE characteristically includes erythema that spares the nasolabial folds but affects the nasal bridge and cheeks.6 The rash occasionally may be pruritic and painful, lasting days to weeks. Photosensitivity occurs, resulting in rashes or even an overall worsening of SLE symptoms. In those with darker skin tones, erythema may appear violaceous or may not be as readily appreciated.6

Worth noting

• Patients with skin of color are at an increased risk for postinflammatory hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation (pigment alteration), hypertrophic scars, and keloids.7,8

• The mortality rate for those with SLE is high despite early recognition and treatment when compared to the general population.1,9

Health disparity highlight

Those at greatest risk for death from SLE in the United States are those of African descent, Hispanic individuals, men, and those with low socioeconomic status,9 which likely is primarily driven by social determinants of health instead of genetic patterns. Income level, educational attainment, insurance status, and environmental factors10 have far-reaching effects, negatively impacting quality of life and even mortality.

- Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, et al. Overall and cause-specific mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: an updated meta-analysis. Lupus. 2016;25:727-734.

- Izmirly PM, Parton H, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States: estimates from a meta-analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registries [published online April 23, 2021]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:991-996. doi:10.1002/art.41632

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412. doi:10.1002/art.40930

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1151-1159.

- Heath CR, Usatine RP. Discoid lupus. Cutis. 2022;109:172-173.

- Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al, eds. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 8th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

- Nozile W, Adgerson CH, Cohen GF. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:343-349.

- Cardinali F, Kovacs D, Picardo M. Mechanisms underlying postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: lessons for solar. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139(suppl 4):S148-S152.

- Ocampo-Piraquive V, Nieto-Aristizábal I, Cañas CA, et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: causes, predictors and interventions. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:1043-1053. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2018.1538789

- Carter EE, Barr SG, Clarke AE. The global burden of SLE: prevalence, health disparities and socioeconomic impact. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:605-620. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.137

- Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, et al. Overall and cause-specific mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: an updated meta-analysis. Lupus. 2016;25:727-734.

- Izmirly PM, Parton H, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States: estimates from a meta-analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registries [published online April 23, 2021]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:991-996. doi:10.1002/art.41632

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412. doi:10.1002/art.40930

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1151-1159.

- Heath CR, Usatine RP. Discoid lupus. Cutis. 2022;109:172-173.

- Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al, eds. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 8th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

- Nozile W, Adgerson CH, Cohen GF. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:343-349.

- Cardinali F, Kovacs D, Picardo M. Mechanisms underlying postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: lessons for solar. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139(suppl 4):S148-S152.

- Ocampo-Piraquive V, Nieto-Aristizábal I, Cañas CA, et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: causes, predictors and interventions. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:1043-1053. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2018.1538789

- Carter EE, Barr SG, Clarke AE. The global burden of SLE: prevalence, health disparities and socioeconomic impact. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:605-620. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.137

Interacting With Dermatology Patients Online: Private Practice vs Academic Institute Website Content

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

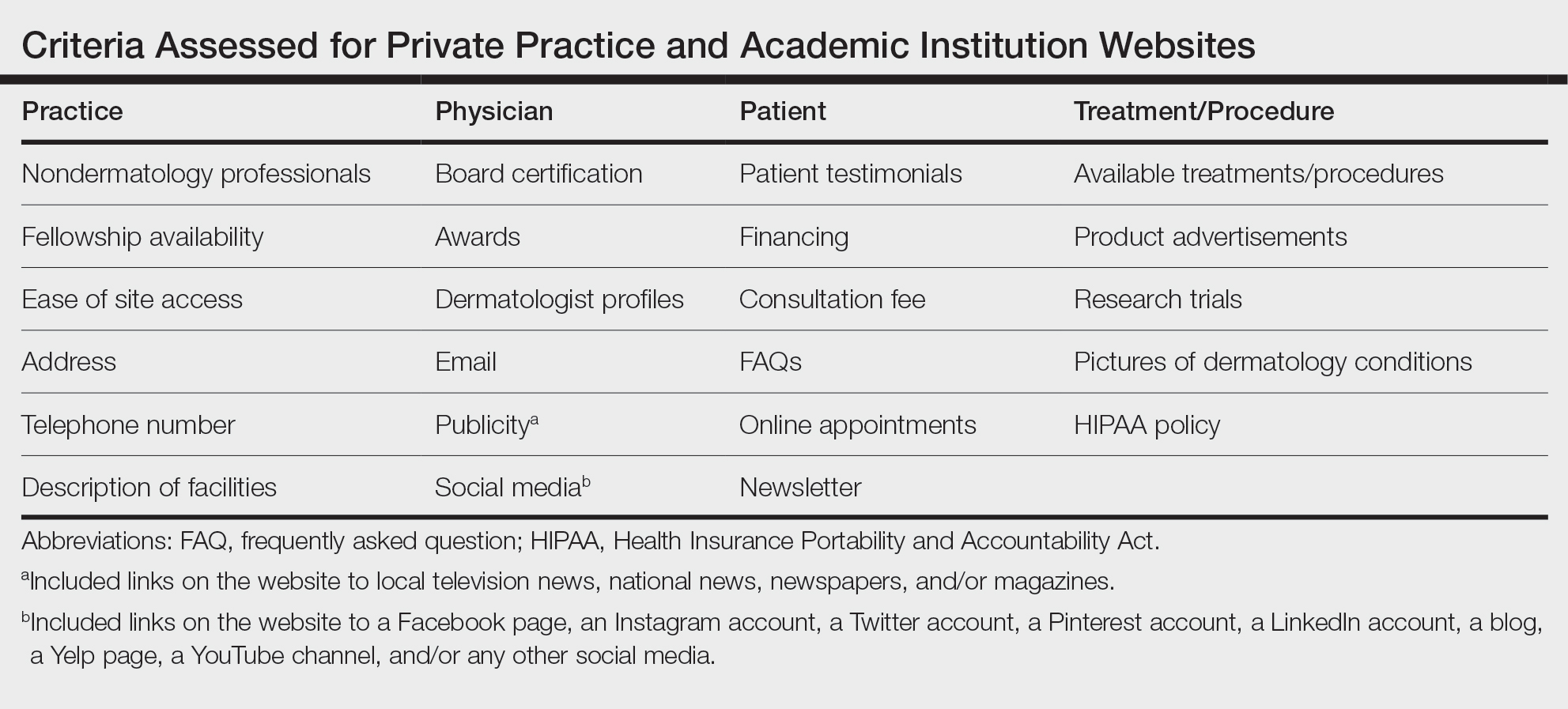

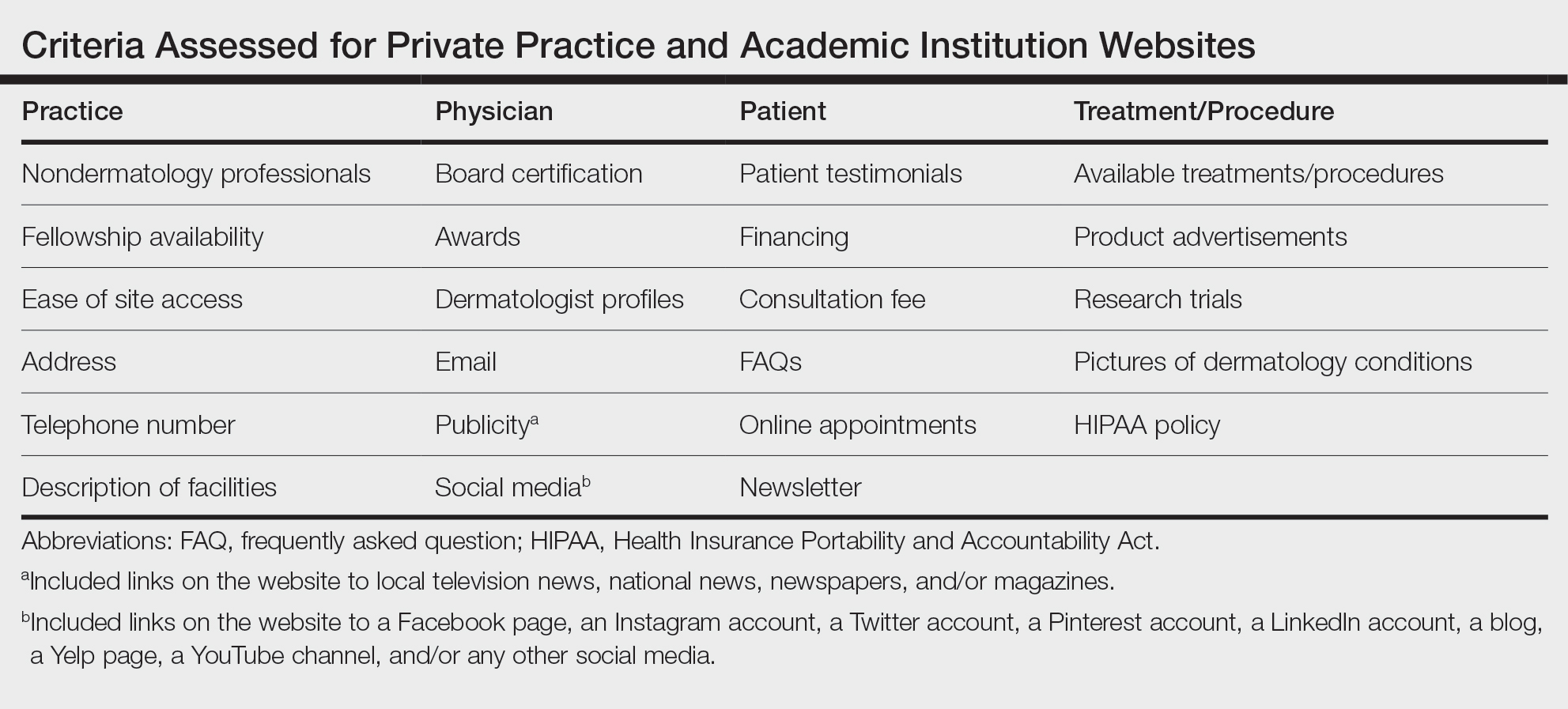

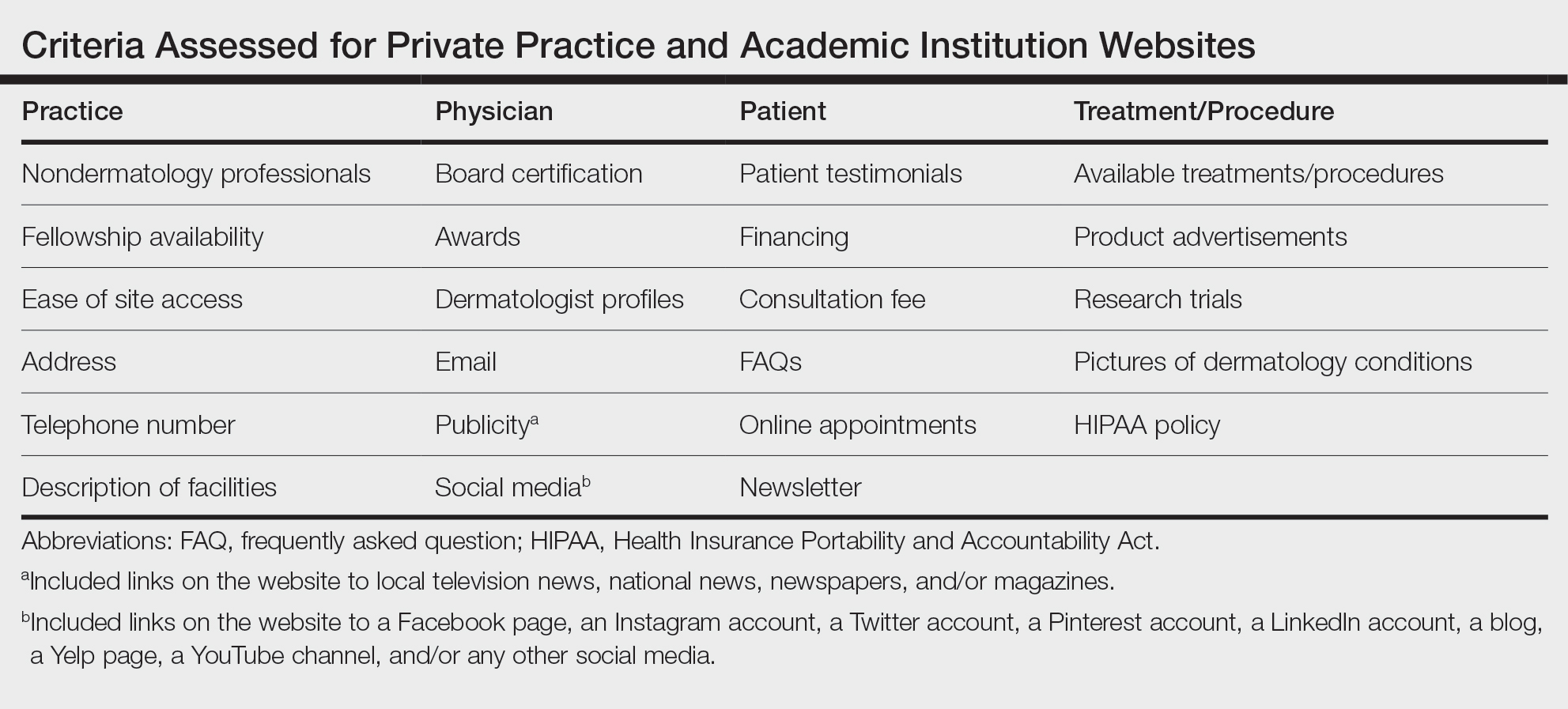

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.

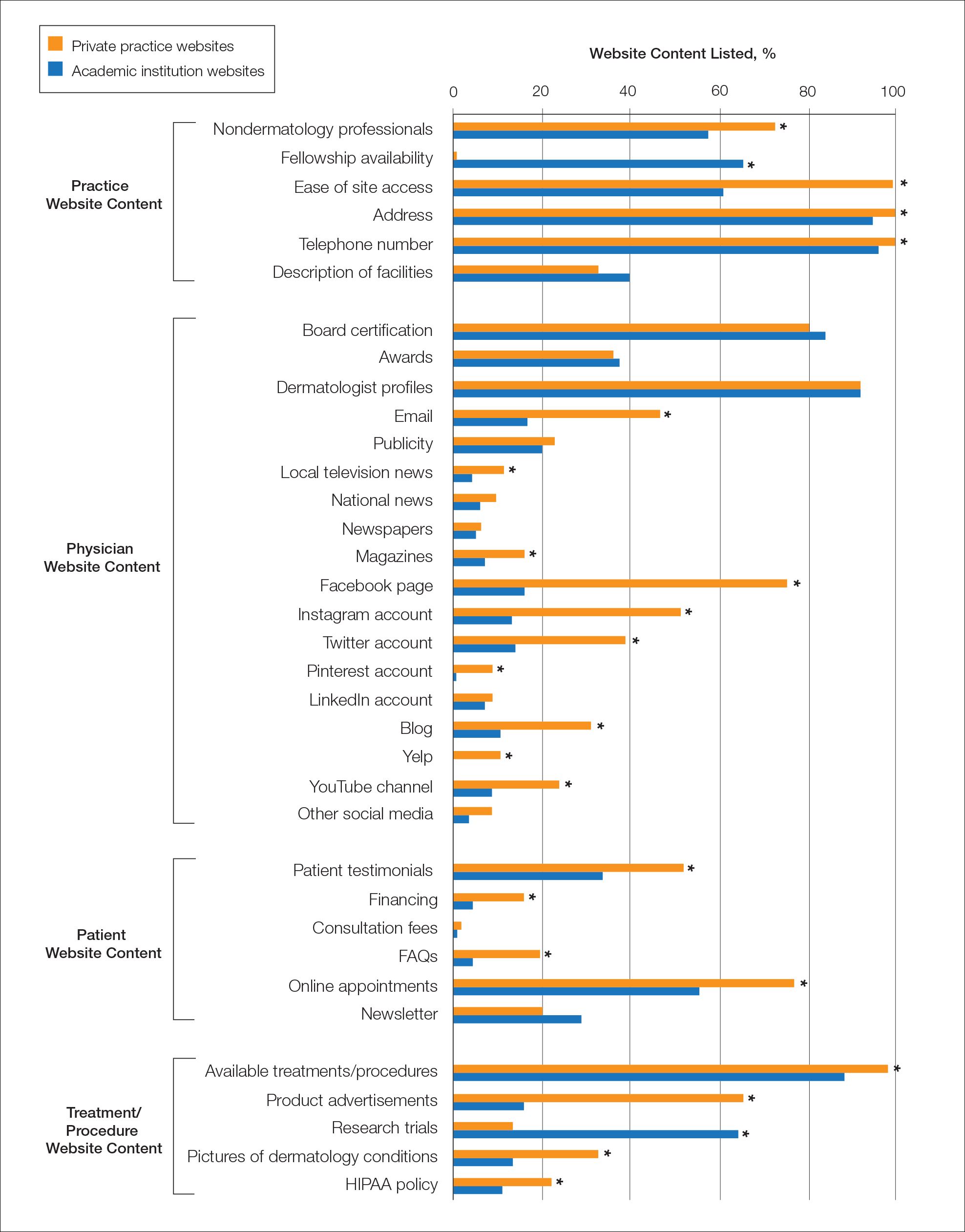

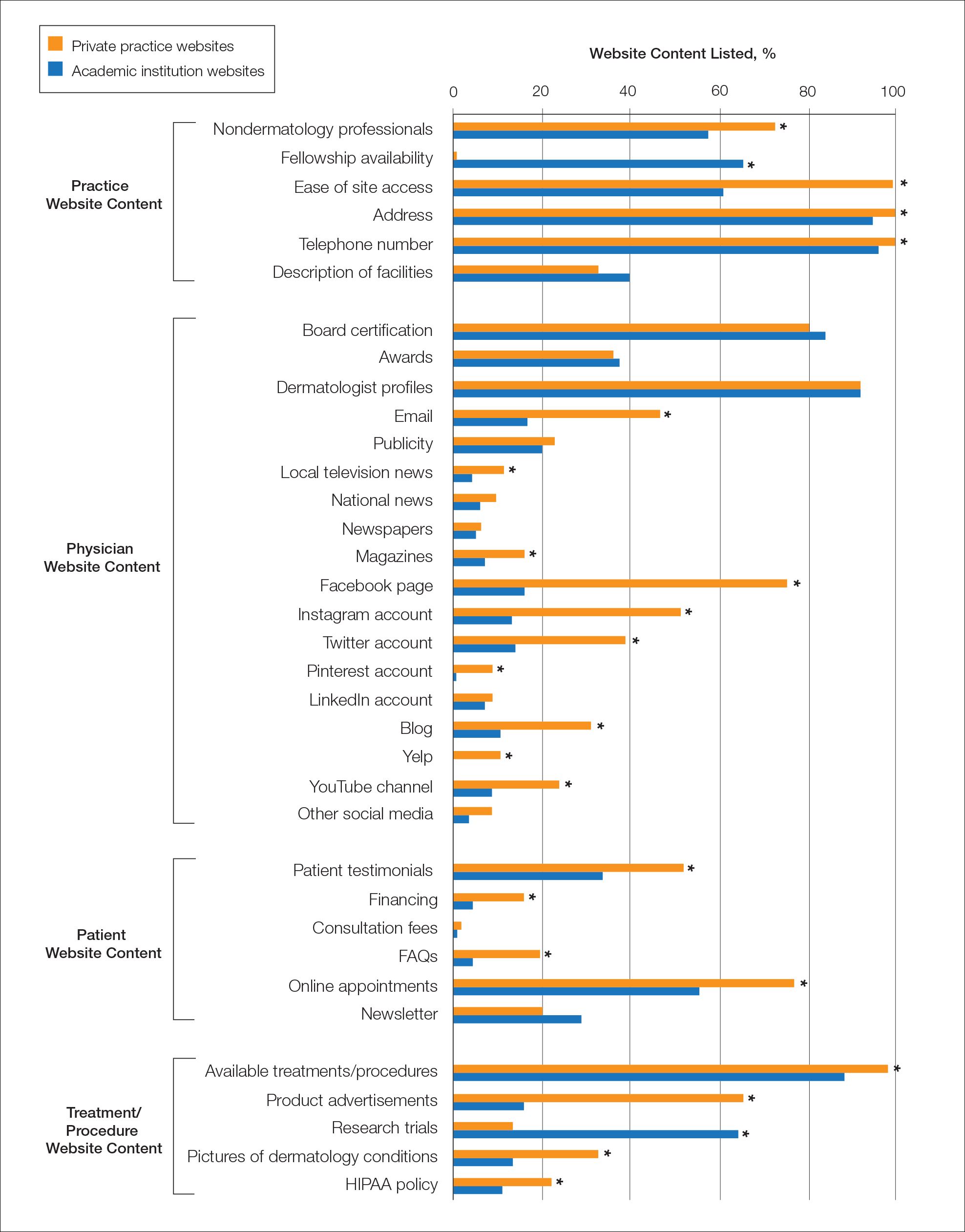

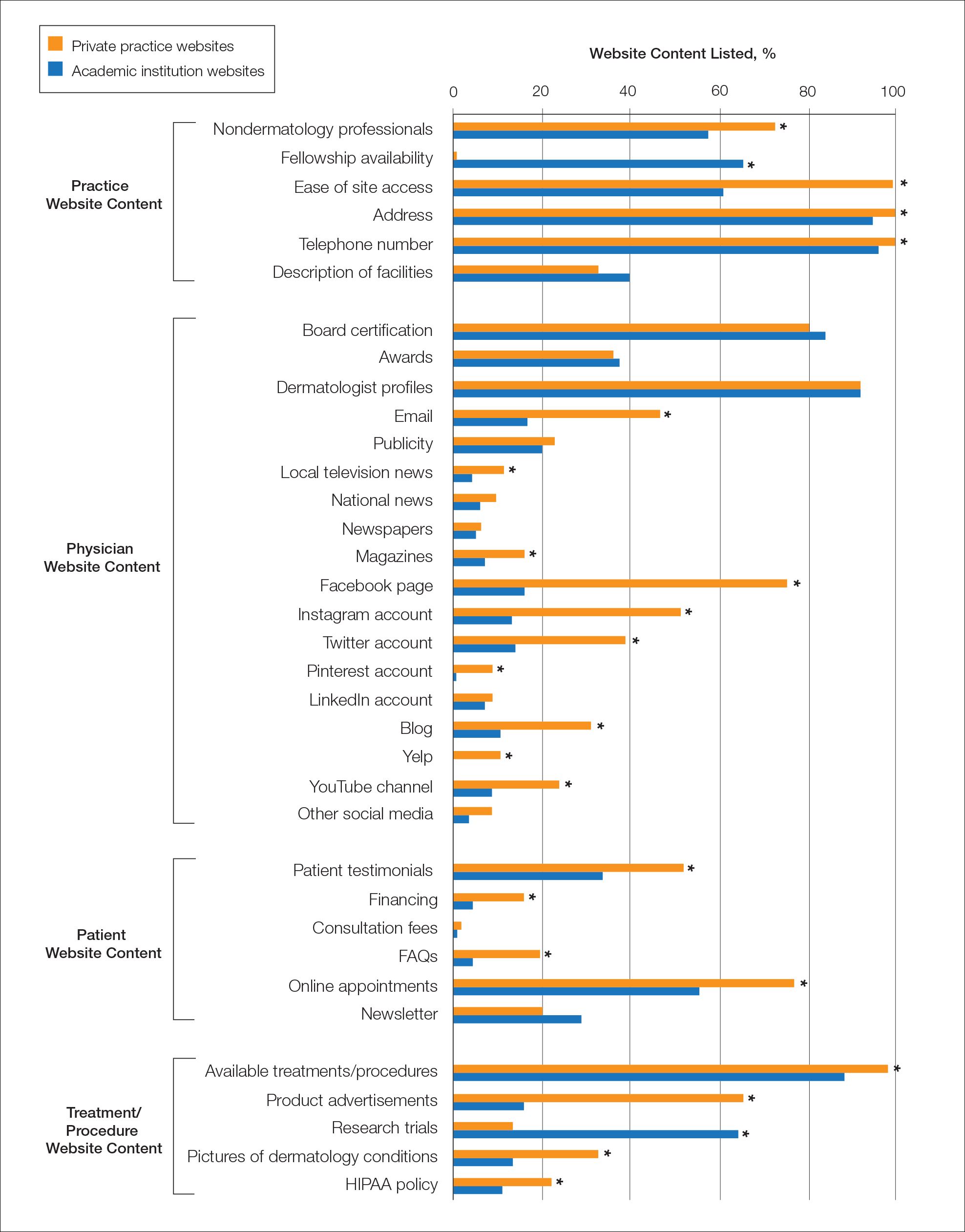

Practice and Physician Content—In the raw analysis (Figure), the most commonly listed types of content (>90% of websites) in both private practice and academic sites was address (range, 95% to 100%), telephone number (range, 97% to 100%), and dermatologist profiles (both 92%). The least commonly listed types of content in both cohorts was publicity (range, 20% to 23%). Private practices were more likely to list profiles of nondermatology professionals (73% vs 56%; P<.02), email (47% vs 17%; P<.0001), and social media (29% vs 8%; P<.0001) compared with academic institution websites. Although Facebook was the most-linked social media account for both groups, 75% of private practice sites included the link compared with 16% of academic institutions. Academic institutions were more likely to list fellowship availability (66% vs 1%; P<.0001). Accessing each website was significantly easier in the private practice cohort (99% vs 61%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list nondermatology professionals’ profiles in densely populated cities when compared with academic institutions (73% vs 41%; P<.01). Academic institutions continued to list fellowship availability more often than private practices regardless of population density. The same trend was observed for private practices with ease of site access and listing of social media.

When controlling for population age, similar trends were seen as when controlling for population density. However, private practices listing nondermatology professionals’ profiles was only more likely in the cities with a proportionately younger population when compared with academic institutions (74% vs 47%; P<.04).

Patient and Treatment/Procedure—The most commonly listed content types on both private practice websites and academic institution websites were available treatments/procedures (range, 89% to 98%). The least commonly listed content included financing for elective procedures (range, 4% to 16%), consultation fees (range, 1% to 2%), FAQs (frequently asked questions)(range, 4% to 20%), and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) policy (range, 12% to 22%). Private practices were more likely to list patient testimonials (52% vs 35%; P<.005), financing (16% vs 4%; P<.005), FAQs (20% vs 4%; P<.001), online appointments (77% vs 56%; P<.001), available treatments/procedures (98% vs 86%; P<.004), product advertisements (66% vs 16%; P<.0001), pictures of dermatology conditions (33% vs 13%; P<.001), and HIPAA policy (22% vs 12%; P<.04). Academic institutions were more likely to list research trials (65% vs 13%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list patient testimonials in densely populated (P=.035) and moderately populated cities (P=.019). The same trend was observed for online appointments in densely populated (P=.0023) and moderately populated cities (P=.037). Private practices continued to list product availability more often than academic institutions regardless of population density or population age. Academic institutions also continued to list research trials more often than private practices regardless of population density or population age.

Comment

Our study uniquely analyzed the differences in website content between private practices and academic institutions in dermatology. Of the 140 academic institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), only 113 had patient-pertinent websites.

Access to Websites —There was a significant difference in many website content criteria between the 2 groups. Private practice sites were easier to access via a Google search when compared with academic sites, which likely is influenced by the Google search algorithm that ranks websites higher based on several criteria including but not limited to keyword use in the title tag, link popularity of the site, and historic ranking. 12,13 Academic sites often were only accessible through portals found on their main institutional site or institution’s residency site.

Role of Social Media —Social media has been found to assist in educating patients on medical practices as well as selecting a physician. 14,15 Our study found that private practice websites listed links to social media more often than their academic counterparts. Social media consumption is increasing, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be optimal for patients and practices alike to include links on their websites. 16 Facebook and Instagram were listed more often on private practice sites when compared with academic institution sites, which was similar to a recent study analyzing the websites of plastic surgery private practices (N = 310) in which 90% of private practices included some type of social media, with Instagram and Facebook being the most used. 8 Social networking accounts can act as convenient platforms for marketing, providing patient education, and generating referrals, which suggests that the prominence of their usage in private practice poses benefits in patient decision-making when seeking care. 17-19 A study analyzing the impact of Facebook in medicine concluded that a Facebook page can serve as an effective vehicle for medical education, particularly in younger generations that favor technology-oriented teaching methods. 20 A survey on trends in cosmetic facial procedures in plastic surgery found that the most influential online methods patients used for choosing their providers were social media platforms and practice websites. Front-page placement on Google also was commonly associated with the number of social media followers. 21,22 A lack of social media prominence could hinder a website’s potential to reach patients.

Communication With Practices —Our study also found significant differences in other metrics related to a patient’s ability to directly communicate with a practice, such as physical addresses, telephone numbers, products available for direct purchase, and online appointment booking, all of which were listed more often on private practice websites compared with academic institution websites. Online appointment booking also was found more frequently on private practice websites. Although physical addresses and telephone numbers were listed significantly more often on private practice sites, this information was ubiquitous and easily accessible elsewhere. Academic institution websites listed research trials and fellowship training significantly more often than private practices. These differences imply a divergence in focus between private practices and academic institutions, likely because academic institutions are funded in large part from research grants, begetting a cycle of academic contribution. 23 In contrast, private practices may not rely as heavily on academic revenue and may be more likely to prioritize other revenue streams such as product sales. 24

HIPAA Policy —Surprisingly, HIPAA policy rarely was listed on any private (22%) or academic site (12%). Conversely, in the plastic surgery study, HIPAA policy was listed much more often, with more than half of private practices with board-certified plastic surgeons accredited in the year 2015 including it on their website, 8 which may suggest that surgically oriented specialties, particularly cosmetic subspecialties, aim to more noticeably display their privacy policies for patient reassurance.

Study Limitations —There are several limitations of our study. First, it is common for a conglomerate company to own multiple private practices in different specialties. As with academic sites, private practice sites may be limited by the hosting platforms, which often are tedious to navigate. Also noteworthy is the emergence of designated social media management positions—both by practice employees and by third-party firms 25 —but the impact of these positions in private practices and academic institutions has not been fully explored. Finally, inclusion criteria and standardized criteria definitions were chosen based on the precedent established by the authors of similar analyses in plastic surgery and radiology. 5-8 Further investigation into the most valued aspects of care by patients within the context of the type of practice chosen would be valuable in refining inclusion criteria. Additionally, this study did not stratify the data collected based on factors such as gender, race, and geographical location; studies conducted on website traffic analysis patterns that focus on these aspects likely would further explain the significance of these findings. Differences in the length of time to the next available appointment between private practices and academic institutions also may help support our findings. Finally, there is a need for further investigation into the preferences of patients themselves garnered from website traffic alone.

Conclusion

Our study examined a diverse compilation of private practice and academic institution websites and uncovered numerous differences in content. As technology and health care continuously evolve, it is imperative that both private practices and academic institutions are actively adapting to optimize their online presence. In doing so, patients will be better equipped at accessing provider information, gaining familiarity with the practice, and understanding treatment options.

- Gentry ZL, Ananthasekar S, Yeatts M, et al. Can patients find an endocrine surgeon? how hospital websites hide the expertise of these medical professionals. Am J Surg . 2021;221:101-105.

- Pollack CE, Rastegar A, Keating NL, et al. Is self-referral associated with higher quality care? Health Serv Res . 2015;50:1472-1490.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Explorer TM tool. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency/residency-explorer-tool

- Find a dermatologist. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://find-a-derm.aad.org/

- Johnson EJ, Doshi AM, Rosenkrantz AB. Strengths and deficiencies in the content of US radiology private practices’ websites. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:431-435.

- Brunk D. Medical website expert shares design tips. Dermatology News . February 9, 2012. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/47413/health-policy/medical-website-expert-shares-design-tips

- Kuhnigk O, Ramuschkat M, Schreiner J, et al. Internet presence of neurologists, psychiatrists and medical psychotherapists in private practice [in German]. Psychiatr Prax . 2013;41:142-147.

- Ananthasekar S, Patel JJ, Patel NJ, et al. The content of US plastic surgery private practices’ websites. Ann Plast Surg . 2021;86(6S suppl 5):S578-S584.

- US Census Bureau. Age and Sex: 2021. Updated December 2, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/age-and-sex/data/tables.2021.List_897222059.html#list-tab-List_897222059

- Porter ME. The competitive advantage of the inner city. Harvard Business Review . Published August 1, 2014. https://hbr.org/1995/05/the-competitive-advantage-of-the-inner-city

- Clark PG. The social allocation of health care resources: ethical dilemmas in age-group competition. Gerontologist. 1985;25:119-125.

- Su A-J, Hu YC, Kuzmanovic A, et al. How to improve your Google ranking: myths and reality. ACM Transactions on the Web . 2014;8. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2579990

- McCormick K. 39 ways to increase traffic to your website. WordStream website. Published March 28, 2023. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2014/08/14/increase-traffic-to-my-website

- Montemurro P, Porcnik A, Hedén P, et al. The influence of social media and easily accessible online information on the aesthetic plastic surgery practice: literature review and our own experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg . 2015;39:270-277.

- Steehler KR, Steehler MK, Pierce ML, et al. Social media’s role in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2013;149:521-524.

- Tsao S-F, Chen H, Tisseverasinghe T, et al. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review. Lancet Digit Health . 2021;3:E175-E194.

- Geist R, Militello M, Albrecht JM, et al. Social media and clinical research in dermatology. Curr Dermatol Rep . 2021;10:105-111.

- McLawhorn AS, De Martino I, Fehring KA, et al. Social media and your practice: navigating the surgeon-patient relationship. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med . 2016;9:487-495.

- Thomas RB, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. Social media for global education: pearls and pitfalls of using Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. J Am Coll Radiol . 2018;15:1513-1516.

- Lugo-Fagundo C, Johnson MB, Thomas RB, et al. New frontiers in education: Facebook as a vehicle for medical information delivery. J Am Coll Radiol . 2016;13:316-319.

- Ho T-VT, Dayan SH. How to leverage social media in private practice. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2020;28:515-522.

- Fan KL, Graziano F, Economides JM, et al. The public’s preferences on plastic surgery social media engagement and professionalism. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2019;143:619-630.

- Jacob BA, Lefgren L. The impact of research grant funding on scientific productivity. J Public Econ. 2011;95:1168-1177.

- Baumann L. Ethics in cosmetic dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:522-527.

- Miller AR, Tucker C. Active social media management: the case of health care. Info Sys Res . 2013;24:52-70.

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.

Practice and Physician Content—In the raw analysis (Figure), the most commonly listed types of content (>90% of websites) in both private practice and academic sites was address (range, 95% to 100%), telephone number (range, 97% to 100%), and dermatologist profiles (both 92%). The least commonly listed types of content in both cohorts was publicity (range, 20% to 23%). Private practices were more likely to list profiles of nondermatology professionals (73% vs 56%; P<.02), email (47% vs 17%; P<.0001), and social media (29% vs 8%; P<.0001) compared with academic institution websites. Although Facebook was the most-linked social media account for both groups, 75% of private practice sites included the link compared with 16% of academic institutions. Academic institutions were more likely to list fellowship availability (66% vs 1%; P<.0001). Accessing each website was significantly easier in the private practice cohort (99% vs 61%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list nondermatology professionals’ profiles in densely populated cities when compared with academic institutions (73% vs 41%; P<.01). Academic institutions continued to list fellowship availability more often than private practices regardless of population density. The same trend was observed for private practices with ease of site access and listing of social media.

When controlling for population age, similar trends were seen as when controlling for population density. However, private practices listing nondermatology professionals’ profiles was only more likely in the cities with a proportionately younger population when compared with academic institutions (74% vs 47%; P<.04).

Patient and Treatment/Procedure—The most commonly listed content types on both private practice websites and academic institution websites were available treatments/procedures (range, 89% to 98%). The least commonly listed content included financing for elective procedures (range, 4% to 16%), consultation fees (range, 1% to 2%), FAQs (frequently asked questions)(range, 4% to 20%), and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) policy (range, 12% to 22%). Private practices were more likely to list patient testimonials (52% vs 35%; P<.005), financing (16% vs 4%; P<.005), FAQs (20% vs 4%; P<.001), online appointments (77% vs 56%; P<.001), available treatments/procedures (98% vs 86%; P<.004), product advertisements (66% vs 16%; P<.0001), pictures of dermatology conditions (33% vs 13%; P<.001), and HIPAA policy (22% vs 12%; P<.04). Academic institutions were more likely to list research trials (65% vs 13%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list patient testimonials in densely populated (P=.035) and moderately populated cities (P=.019). The same trend was observed for online appointments in densely populated (P=.0023) and moderately populated cities (P=.037). Private practices continued to list product availability more often than academic institutions regardless of population density or population age. Academic institutions also continued to list research trials more often than private practices regardless of population density or population age.

Comment

Our study uniquely analyzed the differences in website content between private practices and academic institutions in dermatology. Of the 140 academic institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), only 113 had patient-pertinent websites.

Access to Websites —There was a significant difference in many website content criteria between the 2 groups. Private practice sites were easier to access via a Google search when compared with academic sites, which likely is influenced by the Google search algorithm that ranks websites higher based on several criteria including but not limited to keyword use in the title tag, link popularity of the site, and historic ranking. 12,13 Academic sites often were only accessible through portals found on their main institutional site or institution’s residency site.

Role of Social Media —Social media has been found to assist in educating patients on medical practices as well as selecting a physician. 14,15 Our study found that private practice websites listed links to social media more often than their academic counterparts. Social media consumption is increasing, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be optimal for patients and practices alike to include links on their websites. 16 Facebook and Instagram were listed more often on private practice sites when compared with academic institution sites, which was similar to a recent study analyzing the websites of plastic surgery private practices (N = 310) in which 90% of private practices included some type of social media, with Instagram and Facebook being the most used. 8 Social networking accounts can act as convenient platforms for marketing, providing patient education, and generating referrals, which suggests that the prominence of their usage in private practice poses benefits in patient decision-making when seeking care. 17-19 A study analyzing the impact of Facebook in medicine concluded that a Facebook page can serve as an effective vehicle for medical education, particularly in younger generations that favor technology-oriented teaching methods. 20 A survey on trends in cosmetic facial procedures in plastic surgery found that the most influential online methods patients used for choosing their providers were social media platforms and practice websites. Front-page placement on Google also was commonly associated with the number of social media followers. 21,22 A lack of social media prominence could hinder a website’s potential to reach patients.

Communication With Practices —Our study also found significant differences in other metrics related to a patient’s ability to directly communicate with a practice, such as physical addresses, telephone numbers, products available for direct purchase, and online appointment booking, all of which were listed more often on private practice websites compared with academic institution websites. Online appointment booking also was found more frequently on private practice websites. Although physical addresses and telephone numbers were listed significantly more often on private practice sites, this information was ubiquitous and easily accessible elsewhere. Academic institution websites listed research trials and fellowship training significantly more often than private practices. These differences imply a divergence in focus between private practices and academic institutions, likely because academic institutions are funded in large part from research grants, begetting a cycle of academic contribution. 23 In contrast, private practices may not rely as heavily on academic revenue and may be more likely to prioritize other revenue streams such as product sales. 24

HIPAA Policy —Surprisingly, HIPAA policy rarely was listed on any private (22%) or academic site (12%). Conversely, in the plastic surgery study, HIPAA policy was listed much more often, with more than half of private practices with board-certified plastic surgeons accredited in the year 2015 including it on their website, 8 which may suggest that surgically oriented specialties, particularly cosmetic subspecialties, aim to more noticeably display their privacy policies for patient reassurance.

Study Limitations —There are several limitations of our study. First, it is common for a conglomerate company to own multiple private practices in different specialties. As with academic sites, private practice sites may be limited by the hosting platforms, which often are tedious to navigate. Also noteworthy is the emergence of designated social media management positions—both by practice employees and by third-party firms 25 —but the impact of these positions in private practices and academic institutions has not been fully explored. Finally, inclusion criteria and standardized criteria definitions were chosen based on the precedent established by the authors of similar analyses in plastic surgery and radiology. 5-8 Further investigation into the most valued aspects of care by patients within the context of the type of practice chosen would be valuable in refining inclusion criteria. Additionally, this study did not stratify the data collected based on factors such as gender, race, and geographical location; studies conducted on website traffic analysis patterns that focus on these aspects likely would further explain the significance of these findings. Differences in the length of time to the next available appointment between private practices and academic institutions also may help support our findings. Finally, there is a need for further investigation into the preferences of patients themselves garnered from website traffic alone.

Conclusion

Our study examined a diverse compilation of private practice and academic institution websites and uncovered numerous differences in content. As technology and health care continuously evolve, it is imperative that both private practices and academic institutions are actively adapting to optimize their online presence. In doing so, patients will be better equipped at accessing provider information, gaining familiarity with the practice, and understanding treatment options.

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.