User login

Probiotics with Lactobacillus reduce loss in spine BMD for postmenopausal women

, according to recent research published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

“The menopausal and early postmenopausal lumbar spine bone loss is substantial in women, and by using a prevention therapy with bacteria naturally occurring in the human gut microbiota we observed a close to complete protection against lumbar spine bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women,” Per-Anders Jansson, MD, chief physician at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden), and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Jansson and colleagues performed a double-blind trial at four centers in Sweden in which 249 postmenopausal women were randomized during April-November 2016 to receive probiotics consisting of three Lactobacillus strains or placebo once per day for 12 months. Participants were healthy women, neither underweight nor overweight, and were postmenopausal, which was defined as being 2-12 years or less from last menstruation. The Lactobacillus strains, L. paracasei 8700:2 (DSM 13434), L. plantarum Heal 9 (DSM 15312), and L. plantarum Heal 19 (DSM 15313), were equally represented in a capsule at a dose of 1 x 1010 colony-forming unit per capsule. The researchers measured the lumbar spine bone mineral density (LS-BMD) at baseline and at 12 months, and also evaluated the safety profile of participants in both the probiotic and placebo groups.

Overall, 234 participants (94%) had data available for analysis at the end of the study. There was a significant reduction in LS-BMD loss for participants who received the probiotic treatment, compared with women in the control group (mean difference, 0.71%; 95% confidence interval, 0.06%-1.35%), while there was a significant loss in LS-BMD for participants in the placebo group (percentage change, –0.72%; 95% CI, –1.22% to –0.22%) compared with loss in the probiotic group (percentage change, –0.01%; 95% CI, –0.50% to 0.48%). Using analysis of covariance, the researchers found the probiotic group had reduced LS-BMD loss after adjustment for factors such as study site, age at baseline, BMD at baseline, and number of years from menopause (mean difference, 7.44 mg/cm2; 95% CI, 0.38 to 14.50).

In a subgroup analysis of women above and below the median time since menopause at baseline (6 years), participants in the probiotic group who were below the median time saw a significant protective effect of Lactobacillus treatment (mean difference, 1.08%; 95% CI, 0.20%-1.96%), compared with women above the median time (mean difference, 0.31%; 95% CI, –0.62% to 1.23%).

Researchers also examined the effects of probiotic treatment on total hip and femoral neck BMD as secondary endpoints. Lactobacillus treatment did not appear to affect total hip (–1.01%; 95% CI, –1.65% to –0.37%) or trochanter BMD (–1.13%; 95% CI, –2.27% to 0.20%), but femoral neck BMD was reduced in the probiotic group (–1.34%; 95% CI, –2.09% to –0.58%), compared with the placebo group (–0.88%; 95% CI, –1.64% to –0.13%).

Limitations of the study included examining only one dose of Lactobacillus treatment and no analysis of the effect of short-chain fatty acids on LS-BMD. The researchers noted that “recent studies have shown that short-chain fatty acids, which are generated by fermentation of complex carbohydrates by the gut microbiota, are important regulators of both bone formation and resorption.”

The researchers also acknowledged that the LS-BMD effect size for the probiotic treatment over the 12 months was a lower magnitude, compared with first-line treatments for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women using bisphosphonates. “Further long-term studies should be done to evaluate if the bone-protective effect becomes more pronounced with prolonged treatment with the Lactobacillus strains used in the present study,” they said.

In a related editorial, Shivani Sahni, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Connie M. Weaver, PhD, of Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind., reiterated that the effect size of probiotics is “of far less magnitude” than such treatments as bisphosphonates and expressed concern about the reduction of femoral neck BMD in the probiotic group, which was not explained in the study (Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1[3]:e135-e137. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30073-6). There is a need to learn the optimum dose of probiotics as well as which Lactobacillus strains should be used in future studies, as the strains chosen by Jansson et al. were based on results in mice.

In the meantime, patients might be better off choosing dietary interventions with proven bone protection and no documented negative effects on the hip, such as prebiotics like soluble corn fiber and dried prunes, in tandem with drug therapies, Dr. Sahni and Dr. Weaver said.

“Although Jansson and colleagues’ results are important, more work is needed before such probiotics are ready for consumers,” they concluded.

This study was funded by Probi, which employs two of the study’s authors. Three authors reported being coinventors of a patent involving the effects of probiotics in osteoporosis treatment, and one author is listed as an inventor on a pending patent application on probiotic compositions and uses. Dr. Sahni reported receiving grants from Dairy Management. Dr. Weaver reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jansson P-A et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1(3):e154-e162. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30068-2

, according to recent research published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

“The menopausal and early postmenopausal lumbar spine bone loss is substantial in women, and by using a prevention therapy with bacteria naturally occurring in the human gut microbiota we observed a close to complete protection against lumbar spine bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women,” Per-Anders Jansson, MD, chief physician at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden), and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Jansson and colleagues performed a double-blind trial at four centers in Sweden in which 249 postmenopausal women were randomized during April-November 2016 to receive probiotics consisting of three Lactobacillus strains or placebo once per day for 12 months. Participants were healthy women, neither underweight nor overweight, and were postmenopausal, which was defined as being 2-12 years or less from last menstruation. The Lactobacillus strains, L. paracasei 8700:2 (DSM 13434), L. plantarum Heal 9 (DSM 15312), and L. plantarum Heal 19 (DSM 15313), were equally represented in a capsule at a dose of 1 x 1010 colony-forming unit per capsule. The researchers measured the lumbar spine bone mineral density (LS-BMD) at baseline and at 12 months, and also evaluated the safety profile of participants in both the probiotic and placebo groups.

Overall, 234 participants (94%) had data available for analysis at the end of the study. There was a significant reduction in LS-BMD loss for participants who received the probiotic treatment, compared with women in the control group (mean difference, 0.71%; 95% confidence interval, 0.06%-1.35%), while there was a significant loss in LS-BMD for participants in the placebo group (percentage change, –0.72%; 95% CI, –1.22% to –0.22%) compared with loss in the probiotic group (percentage change, –0.01%; 95% CI, –0.50% to 0.48%). Using analysis of covariance, the researchers found the probiotic group had reduced LS-BMD loss after adjustment for factors such as study site, age at baseline, BMD at baseline, and number of years from menopause (mean difference, 7.44 mg/cm2; 95% CI, 0.38 to 14.50).

In a subgroup analysis of women above and below the median time since menopause at baseline (6 years), participants in the probiotic group who were below the median time saw a significant protective effect of Lactobacillus treatment (mean difference, 1.08%; 95% CI, 0.20%-1.96%), compared with women above the median time (mean difference, 0.31%; 95% CI, –0.62% to 1.23%).

Researchers also examined the effects of probiotic treatment on total hip and femoral neck BMD as secondary endpoints. Lactobacillus treatment did not appear to affect total hip (–1.01%; 95% CI, –1.65% to –0.37%) or trochanter BMD (–1.13%; 95% CI, –2.27% to 0.20%), but femoral neck BMD was reduced in the probiotic group (–1.34%; 95% CI, –2.09% to –0.58%), compared with the placebo group (–0.88%; 95% CI, –1.64% to –0.13%).

Limitations of the study included examining only one dose of Lactobacillus treatment and no analysis of the effect of short-chain fatty acids on LS-BMD. The researchers noted that “recent studies have shown that short-chain fatty acids, which are generated by fermentation of complex carbohydrates by the gut microbiota, are important regulators of both bone formation and resorption.”

The researchers also acknowledged that the LS-BMD effect size for the probiotic treatment over the 12 months was a lower magnitude, compared with first-line treatments for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women using bisphosphonates. “Further long-term studies should be done to evaluate if the bone-protective effect becomes more pronounced with prolonged treatment with the Lactobacillus strains used in the present study,” they said.

In a related editorial, Shivani Sahni, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Connie M. Weaver, PhD, of Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind., reiterated that the effect size of probiotics is “of far less magnitude” than such treatments as bisphosphonates and expressed concern about the reduction of femoral neck BMD in the probiotic group, which was not explained in the study (Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1[3]:e135-e137. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30073-6). There is a need to learn the optimum dose of probiotics as well as which Lactobacillus strains should be used in future studies, as the strains chosen by Jansson et al. were based on results in mice.

In the meantime, patients might be better off choosing dietary interventions with proven bone protection and no documented negative effects on the hip, such as prebiotics like soluble corn fiber and dried prunes, in tandem with drug therapies, Dr. Sahni and Dr. Weaver said.

“Although Jansson and colleagues’ results are important, more work is needed before such probiotics are ready for consumers,” they concluded.

This study was funded by Probi, which employs two of the study’s authors. Three authors reported being coinventors of a patent involving the effects of probiotics in osteoporosis treatment, and one author is listed as an inventor on a pending patent application on probiotic compositions and uses. Dr. Sahni reported receiving grants from Dairy Management. Dr. Weaver reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jansson P-A et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1(3):e154-e162. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30068-2

, according to recent research published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

“The menopausal and early postmenopausal lumbar spine bone loss is substantial in women, and by using a prevention therapy with bacteria naturally occurring in the human gut microbiota we observed a close to complete protection against lumbar spine bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women,” Per-Anders Jansson, MD, chief physician at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden), and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Jansson and colleagues performed a double-blind trial at four centers in Sweden in which 249 postmenopausal women were randomized during April-November 2016 to receive probiotics consisting of three Lactobacillus strains or placebo once per day for 12 months. Participants were healthy women, neither underweight nor overweight, and were postmenopausal, which was defined as being 2-12 years or less from last menstruation. The Lactobacillus strains, L. paracasei 8700:2 (DSM 13434), L. plantarum Heal 9 (DSM 15312), and L. plantarum Heal 19 (DSM 15313), were equally represented in a capsule at a dose of 1 x 1010 colony-forming unit per capsule. The researchers measured the lumbar spine bone mineral density (LS-BMD) at baseline and at 12 months, and also evaluated the safety profile of participants in both the probiotic and placebo groups.

Overall, 234 participants (94%) had data available for analysis at the end of the study. There was a significant reduction in LS-BMD loss for participants who received the probiotic treatment, compared with women in the control group (mean difference, 0.71%; 95% confidence interval, 0.06%-1.35%), while there was a significant loss in LS-BMD for participants in the placebo group (percentage change, –0.72%; 95% CI, –1.22% to –0.22%) compared with loss in the probiotic group (percentage change, –0.01%; 95% CI, –0.50% to 0.48%). Using analysis of covariance, the researchers found the probiotic group had reduced LS-BMD loss after adjustment for factors such as study site, age at baseline, BMD at baseline, and number of years from menopause (mean difference, 7.44 mg/cm2; 95% CI, 0.38 to 14.50).

In a subgroup analysis of women above and below the median time since menopause at baseline (6 years), participants in the probiotic group who were below the median time saw a significant protective effect of Lactobacillus treatment (mean difference, 1.08%; 95% CI, 0.20%-1.96%), compared with women above the median time (mean difference, 0.31%; 95% CI, –0.62% to 1.23%).

Researchers also examined the effects of probiotic treatment on total hip and femoral neck BMD as secondary endpoints. Lactobacillus treatment did not appear to affect total hip (–1.01%; 95% CI, –1.65% to –0.37%) or trochanter BMD (–1.13%; 95% CI, –2.27% to 0.20%), but femoral neck BMD was reduced in the probiotic group (–1.34%; 95% CI, –2.09% to –0.58%), compared with the placebo group (–0.88%; 95% CI, –1.64% to –0.13%).

Limitations of the study included examining only one dose of Lactobacillus treatment and no analysis of the effect of short-chain fatty acids on LS-BMD. The researchers noted that “recent studies have shown that short-chain fatty acids, which are generated by fermentation of complex carbohydrates by the gut microbiota, are important regulators of both bone formation and resorption.”

The researchers also acknowledged that the LS-BMD effect size for the probiotic treatment over the 12 months was a lower magnitude, compared with first-line treatments for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women using bisphosphonates. “Further long-term studies should be done to evaluate if the bone-protective effect becomes more pronounced with prolonged treatment with the Lactobacillus strains used in the present study,” they said.

In a related editorial, Shivani Sahni, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Connie M. Weaver, PhD, of Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind., reiterated that the effect size of probiotics is “of far less magnitude” than such treatments as bisphosphonates and expressed concern about the reduction of femoral neck BMD in the probiotic group, which was not explained in the study (Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1[3]:e135-e137. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30073-6). There is a need to learn the optimum dose of probiotics as well as which Lactobacillus strains should be used in future studies, as the strains chosen by Jansson et al. were based on results in mice.

In the meantime, patients might be better off choosing dietary interventions with proven bone protection and no documented negative effects on the hip, such as prebiotics like soluble corn fiber and dried prunes, in tandem with drug therapies, Dr. Sahni and Dr. Weaver said.

“Although Jansson and colleagues’ results are important, more work is needed before such probiotics are ready for consumers,” they concluded.

This study was funded by Probi, which employs two of the study’s authors. Three authors reported being coinventors of a patent involving the effects of probiotics in osteoporosis treatment, and one author is listed as an inventor on a pending patent application on probiotic compositions and uses. Dr. Sahni reported receiving grants from Dairy Management. Dr. Weaver reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jansson P-A et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1(3):e154-e162. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30068-2

FROM THE LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

Evaluating a Veterans Affairs Home-Based Primary Care Population for Patients at High Risk of Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by the loss of bone density.1 Bone is normally porous and is in a state of flux due to changes in regeneration caused by osteoclast or osteoblast activity. However, age and other factors can accelerate loss in bone density and lead to decreased bone strength and an increased risk of fracture. In men, bone mineral density (BMD) can begin to decline as early as age 30 to 40 years. By age 80 years, 25% of total bone mass may be lost.2

Of the 44 million Americans with low BMD or osteoporosis, 20% are men.1 This group accounts for up to 40% of all osteoporotic fractures. About 1 in 4 men aged ≥ 50 years may experience a lifetime fracture. Fractures may lead to chronic pain, disability, increased dependence, and potentially death. These complications cause expenditures upward of $4.1 billion annually in North America alone.3,4 About 80,000 US men will experience a hip fracture each year, one-third of whom will die within that year. This constitutes a mortality rate 2 to 3 times higher than that of women. Osteoporosis often goes undiagnosed and untreated due to a lack of symptoms until a fracture occurs, underlining the potential benefit of preemptive screening.

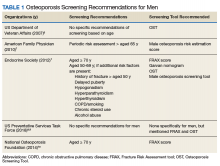

In 2007, Shekell and colleagues outlined how the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) screened men for osteoporosis.5 At the time, 95% of the VA population was male, though it has since dropped to 91%.6 Shekell and colleagues estimated that about 200,0000 to 400,0000 male veterans had osteoporosis.5 Osteoporotic risk factors deemed specific to veterans were excessive alcohol use, spinal cord injury and lack of weight-bearing exercise, prolonged corticosteroid use, and androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer. Different screening techniques were assessed, and the VA recommended the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST).5 Many organizations have developed clinical guidance, including who should be screened; however, screening for men remains a controversial area due to a lack of any strong recommendations (Table 1).

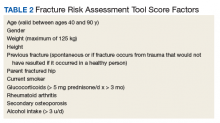

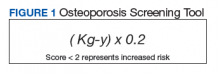

Endocrine Society screening guidelines for men are the most specific: testing BMD in men aged ≥ 70 years, or if aged 50 to 69 years with an additional risk factor (eg, low body weight, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic steroid use).1 The Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX) score is often cited as a common screening tool. It is a free online questionnaire that provides a 10-year probability risk of hip or major osteoporotic fracture.11 However, this tool is limited by age, weight, and the assumption that all questions are answered accurately. Some of the information required includes the presence of a number of risk factors, such as alcohol use, glucocorticoids, and medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, among others (Table 2). The OST score, on the other hand, is a calculation that does not take into account other risk factors (Figure 1). This tool categorizes the patient into low, moderate, or high risk for osteoporosis.8

In a study of 4,000 men aged ≥ 70 years,

A 2017 VA Office of Rural Health study examined the utility of OST to screen referred patients aged > 50 years to receive DEXA scans in patient aligned care team (PACT) clinics at 3 different VA locations.13 The study excluded patients who had been screened previously or treated for osteoporosis, were receiving hospice care; 1 site excluded patients aged > 88 years. Two of the sites also reviewed the patient’s medications to screen for agents that may contribute to increased fracture risk. Veterans identified as high risk were referred for education and offered a DEXA scan and treatment. In total, 867 veterans were screened; 19% (168) were deemed high risk, and 6% (53) underwent DEXA scans. The study noted that only 15 patients had reportable DEXA scans and 10 were positive for bone disease.

As there has been documented success in the PACT setting in implementing standardized protocols for screening and treating veterans, it is reasonable to extend the concept into other VA services. The home-based primary care (HBPC) population is especially vulnerable due to the age of patients, limited weight-bearing exercise to improve bone strength, and limited access to DEXA scans due to difficulty traveling outside of the home. Despite these issues, a goal of the HBPC service is to provide continual care for veterans and improve their health so they may return to the community setting. As a result, patients are followed frequently, providing many opportunities for interventions. This study aims to determine the proportion of HBPC patients who are at high risk for osteoporosis and can receive a DEXA scan for evaluation.

Methods

This study was a retrospective chart analysis using descriptive statistics. It was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC). Patients were included in the study if they were enrolled in the HBPC program at FHCC. Patients were excluded if they were receiving hospice or palliative care, had a limited life expectancy per the HBPC provider, or had a diagnosis of osteoporosis that was being managed by a VA endocrinologist, rheumatologist, or non-VA provider.

The study was conducted from February 1, 2018, through November 30, 2018. All chart reviews were done through the FHCC electronic health record. A minimum of 80 and maximum of 150 charts were reviewed as this was the typical patient volume in the HBPC program. Basic demographic information was collected and analyzed by calculating FRAX and OST scores. With the results, patients were classified as low or high risk of developing osteoporosis, and whether a DEXA scan should be recommended.

Results

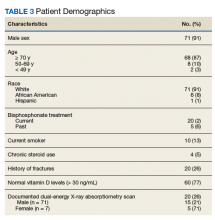

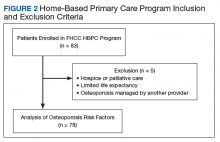

After chart review, 83 patients were enrolled in the FHCC HBPC program during the study period. Out of these, 5 patients were excluded due to hospice or palliative care status, limited life expectancy, or had their osteoporosis managed by another non-HBPC provider. As a result, 78 patients were analyzed to determine their risk of osteoporosis (Figure 2). Most of the patients were white males with a median age of 82 years. A majority of the patients did not have any current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates, 77% had normal vitamin D levels, and only 13% (10) were current smokers; of the male patients only 21% (15) had a previous DEXA scan (Table 3).

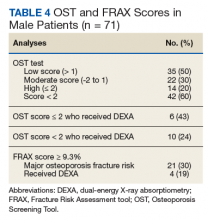

The FRAX and OST scores for each male patient were calculated (Table 4). Half the patients were low risk for osteoporosis. Just 20% (14) of the patients were at high risk for osteoporosis, and only 6 of those had DEXA scans. However, if expanding the criteria to OST scores of < 2, then only 24% (10) received DEXA scans. When calculating FRAX scores, 30% (21) had ≥ 9.3% for major osteoporotic fracture risk, and only 19% (4) had received a DEXA scan.

Discussion

Based on the collected data, many of the male HBPC patients have not had an evaluation for osteoporosis despite being in a high-risk population and meeting some of the screening guidelines by various organizations.1 Based on Diem and colleagues and the 2007 VA report, utilizing OST scores could help capture a subset of patients that would be referred for DEXA scans.5,12 Of the 60% (42) of patients that met OST scores of < 2, 76% (32) of them could have been referred for DEXA scans for osteoporosis evaluation. However, at the time of publication of this article, 50% (16) of the patients have been discharged from the service without interventions. Of the remaining 16 patients, only 2 were referred for a DEXA scan, and 1 patient had confirmed osteoporosis. Currently, these results have been reviewed by the HBPC provider, and plans are in place for DEXA scan referrals for the remaining patients. In addition, for new patients admitted to the program and during annual reviews, the plan is to use OST scores to help screen for osteoporosis.

Limitations

The HBPC population is often in flux due to discharges as patients pass away, become eligible for long-term care, advance to hospice or palliative care status, or see an improvement in their condition to transition back into the community. Along with patients who are bed-bound, have poor prognosis, and barriers to access (eg, transportation issues), interventions for DEXA scan referrals are often not clinically indicated. During calculations of the FRAX score, documentation is often missing from a patient’s medical chart, making it difficult to answer all questions on the questionnaire. This does increase the utility of the OST score as the calculation is much easier and does not rely on other osteoporotic factors. Despite these restrictions for offering DEXA scans, the HBPC service has a high standard of excellence in preventing falls, a major contributor to fractures. Physical therapy services are readily available, nursing visits are frequent and as clinically indicated, vitamin D levels are maintained within normal limits via supplementation, and medication management is performed at least quarterly among other interventions.

Conclusions

The retrospective chart review of patients in the HBPC program suggests that there may be a lack of standardized screening for osteoporosis in the male patient population. As seen within the data, there is great potential for interventions as many of the patients would be candidates for screening based on the OST score. The tool is easy to use and readily accessible to all health care providers and staff. By increasing screening of eligible patients, it also increases the identification of those who would benefit from osteoporosis treatment. While the HBPC population has access limitations (eg, homebound, limited life expectancy), the implementation of a protocol and extension of concepts from this study can be extrapolated into other PACT clinics at VA facilities. Osteoporosis in the male population is often overlooked, but screening procedures can help reduce health care expenditures.

1. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822.

2. Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K, Hutchison JD, Gregori A. Gender differences in epidemiology and outcome after hip fracture: evidence from the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):480-483.

3. Ackman JM, Lata PF, Schuna AA, Elliott ME. Bone health evaluation in a veteran population: a need for the Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX). Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(10):1288-1293.

4. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis in men: why change needs to happen. http://share.iofbone-health.org/WOD/2014/thematic-report/WOD14-Report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 16, 2019.

5. Shekell P, Munjas B, Liu H, et al. Screening Men for Osteoporosis: Who & How. Evidence-based Synthesis Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2007.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Accessed September 16, 2019.

7. Rao SS, Budhwar N, Ashfaque A. Osteoporosis in men. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):503-508.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521-2531.

9. Viswanathan M, Reddy S, Berkman N, et al. Screening to prevent osteoporotic fractures updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2532-2551.

10. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

11. Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, UK. FRAX Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=9. Accessed September 16, 2019.

12. Diem SJ, Peters KW, Gourlay ML, et al; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group. Screening for osteoporosis in older men: operating characteristics of proposed strategies for selecting men for BMD testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1235-1241.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Osteoporosis risk assessment using Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST) and other interventions at rural facilities. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_OST_Issue%20Brief_v2.pdf. Published February 7, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2019.

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by the loss of bone density.1 Bone is normally porous and is in a state of flux due to changes in regeneration caused by osteoclast or osteoblast activity. However, age and other factors can accelerate loss in bone density and lead to decreased bone strength and an increased risk of fracture. In men, bone mineral density (BMD) can begin to decline as early as age 30 to 40 years. By age 80 years, 25% of total bone mass may be lost.2

Of the 44 million Americans with low BMD or osteoporosis, 20% are men.1 This group accounts for up to 40% of all osteoporotic fractures. About 1 in 4 men aged ≥ 50 years may experience a lifetime fracture. Fractures may lead to chronic pain, disability, increased dependence, and potentially death. These complications cause expenditures upward of $4.1 billion annually in North America alone.3,4 About 80,000 US men will experience a hip fracture each year, one-third of whom will die within that year. This constitutes a mortality rate 2 to 3 times higher than that of women. Osteoporosis often goes undiagnosed and untreated due to a lack of symptoms until a fracture occurs, underlining the potential benefit of preemptive screening.

In 2007, Shekell and colleagues outlined how the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) screened men for osteoporosis.5 At the time, 95% of the VA population was male, though it has since dropped to 91%.6 Shekell and colleagues estimated that about 200,0000 to 400,0000 male veterans had osteoporosis.5 Osteoporotic risk factors deemed specific to veterans were excessive alcohol use, spinal cord injury and lack of weight-bearing exercise, prolonged corticosteroid use, and androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer. Different screening techniques were assessed, and the VA recommended the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST).5 Many organizations have developed clinical guidance, including who should be screened; however, screening for men remains a controversial area due to a lack of any strong recommendations (Table 1).

Endocrine Society screening guidelines for men are the most specific: testing BMD in men aged ≥ 70 years, or if aged 50 to 69 years with an additional risk factor (eg, low body weight, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic steroid use).1 The Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX) score is often cited as a common screening tool. It is a free online questionnaire that provides a 10-year probability risk of hip or major osteoporotic fracture.11 However, this tool is limited by age, weight, and the assumption that all questions are answered accurately. Some of the information required includes the presence of a number of risk factors, such as alcohol use, glucocorticoids, and medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, among others (Table 2). The OST score, on the other hand, is a calculation that does not take into account other risk factors (Figure 1). This tool categorizes the patient into low, moderate, or high risk for osteoporosis.8

In a study of 4,000 men aged ≥ 70 years,

A 2017 VA Office of Rural Health study examined the utility of OST to screen referred patients aged > 50 years to receive DEXA scans in patient aligned care team (PACT) clinics at 3 different VA locations.13 The study excluded patients who had been screened previously or treated for osteoporosis, were receiving hospice care; 1 site excluded patients aged > 88 years. Two of the sites also reviewed the patient’s medications to screen for agents that may contribute to increased fracture risk. Veterans identified as high risk were referred for education and offered a DEXA scan and treatment. In total, 867 veterans were screened; 19% (168) were deemed high risk, and 6% (53) underwent DEXA scans. The study noted that only 15 patients had reportable DEXA scans and 10 were positive for bone disease.

As there has been documented success in the PACT setting in implementing standardized protocols for screening and treating veterans, it is reasonable to extend the concept into other VA services. The home-based primary care (HBPC) population is especially vulnerable due to the age of patients, limited weight-bearing exercise to improve bone strength, and limited access to DEXA scans due to difficulty traveling outside of the home. Despite these issues, a goal of the HBPC service is to provide continual care for veterans and improve their health so they may return to the community setting. As a result, patients are followed frequently, providing many opportunities for interventions. This study aims to determine the proportion of HBPC patients who are at high risk for osteoporosis and can receive a DEXA scan for evaluation.

Methods

This study was a retrospective chart analysis using descriptive statistics. It was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC). Patients were included in the study if they were enrolled in the HBPC program at FHCC. Patients were excluded if they were receiving hospice or palliative care, had a limited life expectancy per the HBPC provider, or had a diagnosis of osteoporosis that was being managed by a VA endocrinologist, rheumatologist, or non-VA provider.

The study was conducted from February 1, 2018, through November 30, 2018. All chart reviews were done through the FHCC electronic health record. A minimum of 80 and maximum of 150 charts were reviewed as this was the typical patient volume in the HBPC program. Basic demographic information was collected and analyzed by calculating FRAX and OST scores. With the results, patients were classified as low or high risk of developing osteoporosis, and whether a DEXA scan should be recommended.

Results

After chart review, 83 patients were enrolled in the FHCC HBPC program during the study period. Out of these, 5 patients were excluded due to hospice or palliative care status, limited life expectancy, or had their osteoporosis managed by another non-HBPC provider. As a result, 78 patients were analyzed to determine their risk of osteoporosis (Figure 2). Most of the patients were white males with a median age of 82 years. A majority of the patients did not have any current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates, 77% had normal vitamin D levels, and only 13% (10) were current smokers; of the male patients only 21% (15) had a previous DEXA scan (Table 3).

The FRAX and OST scores for each male patient were calculated (Table 4). Half the patients were low risk for osteoporosis. Just 20% (14) of the patients were at high risk for osteoporosis, and only 6 of those had DEXA scans. However, if expanding the criteria to OST scores of < 2, then only 24% (10) received DEXA scans. When calculating FRAX scores, 30% (21) had ≥ 9.3% for major osteoporotic fracture risk, and only 19% (4) had received a DEXA scan.

Discussion

Based on the collected data, many of the male HBPC patients have not had an evaluation for osteoporosis despite being in a high-risk population and meeting some of the screening guidelines by various organizations.1 Based on Diem and colleagues and the 2007 VA report, utilizing OST scores could help capture a subset of patients that would be referred for DEXA scans.5,12 Of the 60% (42) of patients that met OST scores of < 2, 76% (32) of them could have been referred for DEXA scans for osteoporosis evaluation. However, at the time of publication of this article, 50% (16) of the patients have been discharged from the service without interventions. Of the remaining 16 patients, only 2 were referred for a DEXA scan, and 1 patient had confirmed osteoporosis. Currently, these results have been reviewed by the HBPC provider, and plans are in place for DEXA scan referrals for the remaining patients. In addition, for new patients admitted to the program and during annual reviews, the plan is to use OST scores to help screen for osteoporosis.

Limitations

The HBPC population is often in flux due to discharges as patients pass away, become eligible for long-term care, advance to hospice or palliative care status, or see an improvement in their condition to transition back into the community. Along with patients who are bed-bound, have poor prognosis, and barriers to access (eg, transportation issues), interventions for DEXA scan referrals are often not clinically indicated. During calculations of the FRAX score, documentation is often missing from a patient’s medical chart, making it difficult to answer all questions on the questionnaire. This does increase the utility of the OST score as the calculation is much easier and does not rely on other osteoporotic factors. Despite these restrictions for offering DEXA scans, the HBPC service has a high standard of excellence in preventing falls, a major contributor to fractures. Physical therapy services are readily available, nursing visits are frequent and as clinically indicated, vitamin D levels are maintained within normal limits via supplementation, and medication management is performed at least quarterly among other interventions.

Conclusions

The retrospective chart review of patients in the HBPC program suggests that there may be a lack of standardized screening for osteoporosis in the male patient population. As seen within the data, there is great potential for interventions as many of the patients would be candidates for screening based on the OST score. The tool is easy to use and readily accessible to all health care providers and staff. By increasing screening of eligible patients, it also increases the identification of those who would benefit from osteoporosis treatment. While the HBPC population has access limitations (eg, homebound, limited life expectancy), the implementation of a protocol and extension of concepts from this study can be extrapolated into other PACT clinics at VA facilities. Osteoporosis in the male population is often overlooked, but screening procedures can help reduce health care expenditures.

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by the loss of bone density.1 Bone is normally porous and is in a state of flux due to changes in regeneration caused by osteoclast or osteoblast activity. However, age and other factors can accelerate loss in bone density and lead to decreased bone strength and an increased risk of fracture. In men, bone mineral density (BMD) can begin to decline as early as age 30 to 40 years. By age 80 years, 25% of total bone mass may be lost.2

Of the 44 million Americans with low BMD or osteoporosis, 20% are men.1 This group accounts for up to 40% of all osteoporotic fractures. About 1 in 4 men aged ≥ 50 years may experience a lifetime fracture. Fractures may lead to chronic pain, disability, increased dependence, and potentially death. These complications cause expenditures upward of $4.1 billion annually in North America alone.3,4 About 80,000 US men will experience a hip fracture each year, one-third of whom will die within that year. This constitutes a mortality rate 2 to 3 times higher than that of women. Osteoporosis often goes undiagnosed and untreated due to a lack of symptoms until a fracture occurs, underlining the potential benefit of preemptive screening.

In 2007, Shekell and colleagues outlined how the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) screened men for osteoporosis.5 At the time, 95% of the VA population was male, though it has since dropped to 91%.6 Shekell and colleagues estimated that about 200,0000 to 400,0000 male veterans had osteoporosis.5 Osteoporotic risk factors deemed specific to veterans were excessive alcohol use, spinal cord injury and lack of weight-bearing exercise, prolonged corticosteroid use, and androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer. Different screening techniques were assessed, and the VA recommended the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST).5 Many organizations have developed clinical guidance, including who should be screened; however, screening for men remains a controversial area due to a lack of any strong recommendations (Table 1).

Endocrine Society screening guidelines for men are the most specific: testing BMD in men aged ≥ 70 years, or if aged 50 to 69 years with an additional risk factor (eg, low body weight, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic steroid use).1 The Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX) score is often cited as a common screening tool. It is a free online questionnaire that provides a 10-year probability risk of hip or major osteoporotic fracture.11 However, this tool is limited by age, weight, and the assumption that all questions are answered accurately. Some of the information required includes the presence of a number of risk factors, such as alcohol use, glucocorticoids, and medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, among others (Table 2). The OST score, on the other hand, is a calculation that does not take into account other risk factors (Figure 1). This tool categorizes the patient into low, moderate, or high risk for osteoporosis.8

In a study of 4,000 men aged ≥ 70 years,

A 2017 VA Office of Rural Health study examined the utility of OST to screen referred patients aged > 50 years to receive DEXA scans in patient aligned care team (PACT) clinics at 3 different VA locations.13 The study excluded patients who had been screened previously or treated for osteoporosis, were receiving hospice care; 1 site excluded patients aged > 88 years. Two of the sites also reviewed the patient’s medications to screen for agents that may contribute to increased fracture risk. Veterans identified as high risk were referred for education and offered a DEXA scan and treatment. In total, 867 veterans were screened; 19% (168) were deemed high risk, and 6% (53) underwent DEXA scans. The study noted that only 15 patients had reportable DEXA scans and 10 were positive for bone disease.

As there has been documented success in the PACT setting in implementing standardized protocols for screening and treating veterans, it is reasonable to extend the concept into other VA services. The home-based primary care (HBPC) population is especially vulnerable due to the age of patients, limited weight-bearing exercise to improve bone strength, and limited access to DEXA scans due to difficulty traveling outside of the home. Despite these issues, a goal of the HBPC service is to provide continual care for veterans and improve their health so they may return to the community setting. As a result, patients are followed frequently, providing many opportunities for interventions. This study aims to determine the proportion of HBPC patients who are at high risk for osteoporosis and can receive a DEXA scan for evaluation.

Methods

This study was a retrospective chart analysis using descriptive statistics. It was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC). Patients were included in the study if they were enrolled in the HBPC program at FHCC. Patients were excluded if they were receiving hospice or palliative care, had a limited life expectancy per the HBPC provider, or had a diagnosis of osteoporosis that was being managed by a VA endocrinologist, rheumatologist, or non-VA provider.

The study was conducted from February 1, 2018, through November 30, 2018. All chart reviews were done through the FHCC electronic health record. A minimum of 80 and maximum of 150 charts were reviewed as this was the typical patient volume in the HBPC program. Basic demographic information was collected and analyzed by calculating FRAX and OST scores. With the results, patients were classified as low or high risk of developing osteoporosis, and whether a DEXA scan should be recommended.

Results

After chart review, 83 patients were enrolled in the FHCC HBPC program during the study period. Out of these, 5 patients were excluded due to hospice or palliative care status, limited life expectancy, or had their osteoporosis managed by another non-HBPC provider. As a result, 78 patients were analyzed to determine their risk of osteoporosis (Figure 2). Most of the patients were white males with a median age of 82 years. A majority of the patients did not have any current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates, 77% had normal vitamin D levels, and only 13% (10) were current smokers; of the male patients only 21% (15) had a previous DEXA scan (Table 3).

The FRAX and OST scores for each male patient were calculated (Table 4). Half the patients were low risk for osteoporosis. Just 20% (14) of the patients were at high risk for osteoporosis, and only 6 of those had DEXA scans. However, if expanding the criteria to OST scores of < 2, then only 24% (10) received DEXA scans. When calculating FRAX scores, 30% (21) had ≥ 9.3% for major osteoporotic fracture risk, and only 19% (4) had received a DEXA scan.

Discussion

Based on the collected data, many of the male HBPC patients have not had an evaluation for osteoporosis despite being in a high-risk population and meeting some of the screening guidelines by various organizations.1 Based on Diem and colleagues and the 2007 VA report, utilizing OST scores could help capture a subset of patients that would be referred for DEXA scans.5,12 Of the 60% (42) of patients that met OST scores of < 2, 76% (32) of them could have been referred for DEXA scans for osteoporosis evaluation. However, at the time of publication of this article, 50% (16) of the patients have been discharged from the service without interventions. Of the remaining 16 patients, only 2 were referred for a DEXA scan, and 1 patient had confirmed osteoporosis. Currently, these results have been reviewed by the HBPC provider, and plans are in place for DEXA scan referrals for the remaining patients. In addition, for new patients admitted to the program and during annual reviews, the plan is to use OST scores to help screen for osteoporosis.

Limitations

The HBPC population is often in flux due to discharges as patients pass away, become eligible for long-term care, advance to hospice or palliative care status, or see an improvement in their condition to transition back into the community. Along with patients who are bed-bound, have poor prognosis, and barriers to access (eg, transportation issues), interventions for DEXA scan referrals are often not clinically indicated. During calculations of the FRAX score, documentation is often missing from a patient’s medical chart, making it difficult to answer all questions on the questionnaire. This does increase the utility of the OST score as the calculation is much easier and does not rely on other osteoporotic factors. Despite these restrictions for offering DEXA scans, the HBPC service has a high standard of excellence in preventing falls, a major contributor to fractures. Physical therapy services are readily available, nursing visits are frequent and as clinically indicated, vitamin D levels are maintained within normal limits via supplementation, and medication management is performed at least quarterly among other interventions.

Conclusions

The retrospective chart review of patients in the HBPC program suggests that there may be a lack of standardized screening for osteoporosis in the male patient population. As seen within the data, there is great potential for interventions as many of the patients would be candidates for screening based on the OST score. The tool is easy to use and readily accessible to all health care providers and staff. By increasing screening of eligible patients, it also increases the identification of those who would benefit from osteoporosis treatment. While the HBPC population has access limitations (eg, homebound, limited life expectancy), the implementation of a protocol and extension of concepts from this study can be extrapolated into other PACT clinics at VA facilities. Osteoporosis in the male population is often overlooked, but screening procedures can help reduce health care expenditures.

1. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822.

2. Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K, Hutchison JD, Gregori A. Gender differences in epidemiology and outcome after hip fracture: evidence from the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):480-483.

3. Ackman JM, Lata PF, Schuna AA, Elliott ME. Bone health evaluation in a veteran population: a need for the Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX). Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(10):1288-1293.

4. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis in men: why change needs to happen. http://share.iofbone-health.org/WOD/2014/thematic-report/WOD14-Report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 16, 2019.

5. Shekell P, Munjas B, Liu H, et al. Screening Men for Osteoporosis: Who & How. Evidence-based Synthesis Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2007.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Accessed September 16, 2019.

7. Rao SS, Budhwar N, Ashfaque A. Osteoporosis in men. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):503-508.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521-2531.

9. Viswanathan M, Reddy S, Berkman N, et al. Screening to prevent osteoporotic fractures updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2532-2551.

10. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

11. Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, UK. FRAX Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=9. Accessed September 16, 2019.

12. Diem SJ, Peters KW, Gourlay ML, et al; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group. Screening for osteoporosis in older men: operating characteristics of proposed strategies for selecting men for BMD testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1235-1241.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Osteoporosis risk assessment using Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST) and other interventions at rural facilities. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_OST_Issue%20Brief_v2.pdf. Published February 7, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2019.

1. Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-1822.

2. Holt G, Smith R, Duncan K, Hutchison JD, Gregori A. Gender differences in epidemiology and outcome after hip fracture: evidence from the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):480-483.

3. Ackman JM, Lata PF, Schuna AA, Elliott ME. Bone health evaluation in a veteran population: a need for the Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX). Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(10):1288-1293.

4. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis in men: why change needs to happen. http://share.iofbone-health.org/WOD/2014/thematic-report/WOD14-Report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 16, 2019.

5. Shekell P, Munjas B, Liu H, et al. Screening Men for Osteoporosis: Who & How. Evidence-based Synthesis Program. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2007.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Accessed September 16, 2019.

7. Rao SS, Budhwar N, Ashfaque A. Osteoporosis in men. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):503-508.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521-2531.

9. Viswanathan M, Reddy S, Berkman N, et al. Screening to prevent osteoporotic fractures updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2532-2551.

10. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

11. Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, UK. FRAX Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=9. Accessed September 16, 2019.

12. Diem SJ, Peters KW, Gourlay ML, et al; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research Group. Screening for osteoporosis in older men: operating characteristics of proposed strategies for selecting men for BMD testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1235-1241.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Osteoporosis risk assessment using Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST) and other interventions at rural facilities. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/promise/2017_02_01_OST_Issue%20Brief_v2.pdf. Published February 7, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2019.

Get ready for changes in polypharmacy quality ratings

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – and managed care organizations should start preparing now for the shift.

Panelists at an Oct. 30 session at the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy presented strategies for addressing the three areas of polypharmacy that will be tracked in the new rating system, which will replace the current high-risk medication measurement that is being retired this year.

Anticholinergic medications

The first area presented by the panelists was polypharmacy use of multiple anticholinergic medications in older adults (Poly-ACH). The new quality measure will examine the percentage of members aged 65 years or older who are using two or more anticholinergic medications concurrently.

“We know that anticholinergic burden increases the risk of cognitive decline in particular, but it’s also associated with a higher risk of falls, an increased number of hospitalizations, and [diminished] physical function,” said Marti Groeneweg, PharmD, supervisor of clinical pharmacy services at Kaiser Permanente.

Dr. Groeneweg noted that, in addition to using multiple drugs in this class, patients can also benefit from a decrease in the dosage of their drugs, so that should also be considered in managing the medication of beneficiaries.

She highlighted a program Kaiser Permanente started in the Northwest United States to reduce the concurrent use of these drugs. The program targeted tricyclic antidepressants – nortriptyline, in particular.

The company instituted a multipronged approach that included provider detailing of the risks of using multiple drugs and how they could taper schedules, as well as providing them with other supporting resources and a list of safer, alternative drugs. It also reached out to patients to educate them about the risks of their medications and why it was important for them to taper their medications. The third part of the approach was to use the EHR to provide doctors with the best-available information at the point of prescribing. And finally, there was a pharmacist review process put in place for more complex cases.

Dr. Groeneweg emphasized that this information was incorporated into existing programs.

The intervention, which is fairly new, has not been in place long enough to know exactly how well it is working, but early indicators suggest “we are on the right track,” she said, noting that to date there has been a decrease of 28% in the number of tricyclic antidepressant prescriptions per 1,000 Medicare members per month.

CNS medications

The second area the panelists addressed was the polypharmacy use of multiple CNS-active medications in older adults (Poly-CNS).

Rainelle Gaddy, PharmD, Rx clinical programs pharmacy lead at Humana Pharmacy Solutions, , noted that the clinical rationale for this measure was the “increased risk of falls and fractures when these medications are taken concurrently.”

She pointed out that taking one or more of the CNS medications can result in a 1.5-fold increase in the risk for falls, and that risk increases to 2.5-fold if two or more drugs are taken. In addition, a high-dose of these medications can lead to a threefold increase in risk of recurrent falls.

Dr. Gaddy highlighted a number of interventions that could be implemented when the managed care organization is not integrated in the way Kaiser Permanente is.

“Pharmacists can pay a pivotal role [in helping] patients who are receiving these Poly-CNS medications because they are able to interact and talk through the actual patient picture for all their medications ... because pharmacists have always been seen as being a trusted source,” she said.

Dr. Gaddy added that health plans can take a more direct role in reaching out to patients, for example, through telephone outreach, as well as direct mail, email, and newsletters.

“We want to make sure that members have as much information as possible,” she said.

She added that it is very important to include physicians and other prescribers in this process through faxes and information included in EHRs.

Opioids and benzodiazepines

The final measure highlighted during the session was the one measuring the concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines.

Dr. Gaddy noted that taking the two concurrently is associated with a fourfold increase in risk of opioid overdose and death, compared with opioid use without a benzodiazepine.

She noted that a black box warning on the risks of concurrent use was added to both opioids and benzodiazepines in August 2016 and that resulted in a 10% decrease in the concurrent use.

“This new measure is intended to ensure that the downward trend continues. CMS has indicated as such,” Dr. Gaddy said.

Most of the intervention strategies she highlighted were similar to those for the Poly-CNS category, including the use of medication therapy management programs and targeted interventions, telephone outreach to members, and provider detailing and outreach.

“Provider detailing is really key,” Dr. Gaddy said. “On any given day, it’s so easy for physicians to see 30 patients. The great thing about the provider detailing is that you are able to give the provider a ‘packet’ of their members, you can identify and/or aid in showing them the risk assessment associated with members taking these medications, and then equip them with pocket guides and [materials so they can] streamline the medications.”

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – and managed care organizations should start preparing now for the shift.

Panelists at an Oct. 30 session at the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy presented strategies for addressing the three areas of polypharmacy that will be tracked in the new rating system, which will replace the current high-risk medication measurement that is being retired this year.

Anticholinergic medications

The first area presented by the panelists was polypharmacy use of multiple anticholinergic medications in older adults (Poly-ACH). The new quality measure will examine the percentage of members aged 65 years or older who are using two or more anticholinergic medications concurrently.

“We know that anticholinergic burden increases the risk of cognitive decline in particular, but it’s also associated with a higher risk of falls, an increased number of hospitalizations, and [diminished] physical function,” said Marti Groeneweg, PharmD, supervisor of clinical pharmacy services at Kaiser Permanente.

Dr. Groeneweg noted that, in addition to using multiple drugs in this class, patients can also benefit from a decrease in the dosage of their drugs, so that should also be considered in managing the medication of beneficiaries.

She highlighted a program Kaiser Permanente started in the Northwest United States to reduce the concurrent use of these drugs. The program targeted tricyclic antidepressants – nortriptyline, in particular.

The company instituted a multipronged approach that included provider detailing of the risks of using multiple drugs and how they could taper schedules, as well as providing them with other supporting resources and a list of safer, alternative drugs. It also reached out to patients to educate them about the risks of their medications and why it was important for them to taper their medications. The third part of the approach was to use the EHR to provide doctors with the best-available information at the point of prescribing. And finally, there was a pharmacist review process put in place for more complex cases.

Dr. Groeneweg emphasized that this information was incorporated into existing programs.

The intervention, which is fairly new, has not been in place long enough to know exactly how well it is working, but early indicators suggest “we are on the right track,” she said, noting that to date there has been a decrease of 28% in the number of tricyclic antidepressant prescriptions per 1,000 Medicare members per month.

CNS medications

The second area the panelists addressed was the polypharmacy use of multiple CNS-active medications in older adults (Poly-CNS).

Rainelle Gaddy, PharmD, Rx clinical programs pharmacy lead at Humana Pharmacy Solutions, , noted that the clinical rationale for this measure was the “increased risk of falls and fractures when these medications are taken concurrently.”

She pointed out that taking one or more of the CNS medications can result in a 1.5-fold increase in the risk for falls, and that risk increases to 2.5-fold if two or more drugs are taken. In addition, a high-dose of these medications can lead to a threefold increase in risk of recurrent falls.

Dr. Gaddy highlighted a number of interventions that could be implemented when the managed care organization is not integrated in the way Kaiser Permanente is.

“Pharmacists can pay a pivotal role [in helping] patients who are receiving these Poly-CNS medications because they are able to interact and talk through the actual patient picture for all their medications ... because pharmacists have always been seen as being a trusted source,” she said.

Dr. Gaddy added that health plans can take a more direct role in reaching out to patients, for example, through telephone outreach, as well as direct mail, email, and newsletters.

“We want to make sure that members have as much information as possible,” she said.

She added that it is very important to include physicians and other prescribers in this process through faxes and information included in EHRs.

Opioids and benzodiazepines

The final measure highlighted during the session was the one measuring the concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines.

Dr. Gaddy noted that taking the two concurrently is associated with a fourfold increase in risk of opioid overdose and death, compared with opioid use without a benzodiazepine.

She noted that a black box warning on the risks of concurrent use was added to both opioids and benzodiazepines in August 2016 and that resulted in a 10% decrease in the concurrent use.

“This new measure is intended to ensure that the downward trend continues. CMS has indicated as such,” Dr. Gaddy said.

Most of the intervention strategies she highlighted were similar to those for the Poly-CNS category, including the use of medication therapy management programs and targeted interventions, telephone outreach to members, and provider detailing and outreach.

“Provider detailing is really key,” Dr. Gaddy said. “On any given day, it’s so easy for physicians to see 30 patients. The great thing about the provider detailing is that you are able to give the provider a ‘packet’ of their members, you can identify and/or aid in showing them the risk assessment associated with members taking these medications, and then equip them with pocket guides and [materials so they can] streamline the medications.”

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – and managed care organizations should start preparing now for the shift.

Panelists at an Oct. 30 session at the annual meeting of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy presented strategies for addressing the three areas of polypharmacy that will be tracked in the new rating system, which will replace the current high-risk medication measurement that is being retired this year.

Anticholinergic medications

The first area presented by the panelists was polypharmacy use of multiple anticholinergic medications in older adults (Poly-ACH). The new quality measure will examine the percentage of members aged 65 years or older who are using two or more anticholinergic medications concurrently.

“We know that anticholinergic burden increases the risk of cognitive decline in particular, but it’s also associated with a higher risk of falls, an increased number of hospitalizations, and [diminished] physical function,” said Marti Groeneweg, PharmD, supervisor of clinical pharmacy services at Kaiser Permanente.

Dr. Groeneweg noted that, in addition to using multiple drugs in this class, patients can also benefit from a decrease in the dosage of their drugs, so that should also be considered in managing the medication of beneficiaries.

She highlighted a program Kaiser Permanente started in the Northwest United States to reduce the concurrent use of these drugs. The program targeted tricyclic antidepressants – nortriptyline, in particular.

The company instituted a multipronged approach that included provider detailing of the risks of using multiple drugs and how they could taper schedules, as well as providing them with other supporting resources and a list of safer, alternative drugs. It also reached out to patients to educate them about the risks of their medications and why it was important for them to taper their medications. The third part of the approach was to use the EHR to provide doctors with the best-available information at the point of prescribing. And finally, there was a pharmacist review process put in place for more complex cases.

Dr. Groeneweg emphasized that this information was incorporated into existing programs.

The intervention, which is fairly new, has not been in place long enough to know exactly how well it is working, but early indicators suggest “we are on the right track,” she said, noting that to date there has been a decrease of 28% in the number of tricyclic antidepressant prescriptions per 1,000 Medicare members per month.

CNS medications

The second area the panelists addressed was the polypharmacy use of multiple CNS-active medications in older adults (Poly-CNS).

Rainelle Gaddy, PharmD, Rx clinical programs pharmacy lead at Humana Pharmacy Solutions, , noted that the clinical rationale for this measure was the “increased risk of falls and fractures when these medications are taken concurrently.”

She pointed out that taking one or more of the CNS medications can result in a 1.5-fold increase in the risk for falls, and that risk increases to 2.5-fold if two or more drugs are taken. In addition, a high-dose of these medications can lead to a threefold increase in risk of recurrent falls.

Dr. Gaddy highlighted a number of interventions that could be implemented when the managed care organization is not integrated in the way Kaiser Permanente is.

“Pharmacists can pay a pivotal role [in helping] patients who are receiving these Poly-CNS medications because they are able to interact and talk through the actual patient picture for all their medications ... because pharmacists have always been seen as being a trusted source,” she said.

Dr. Gaddy added that health plans can take a more direct role in reaching out to patients, for example, through telephone outreach, as well as direct mail, email, and newsletters.

“We want to make sure that members have as much information as possible,” she said.

She added that it is very important to include physicians and other prescribers in this process through faxes and information included in EHRs.

Opioids and benzodiazepines

The final measure highlighted during the session was the one measuring the concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines.

Dr. Gaddy noted that taking the two concurrently is associated with a fourfold increase in risk of opioid overdose and death, compared with opioid use without a benzodiazepine.

She noted that a black box warning on the risks of concurrent use was added to both opioids and benzodiazepines in August 2016 and that resulted in a 10% decrease in the concurrent use.

“This new measure is intended to ensure that the downward trend continues. CMS has indicated as such,” Dr. Gaddy said.

Most of the intervention strategies she highlighted were similar to those for the Poly-CNS category, including the use of medication therapy management programs and targeted interventions, telephone outreach to members, and provider detailing and outreach.

“Provider detailing is really key,” Dr. Gaddy said. “On any given day, it’s so easy for physicians to see 30 patients. The great thing about the provider detailing is that you are able to give the provider a ‘packet’ of their members, you can identify and/or aid in showing them the risk assessment associated with members taking these medications, and then equip them with pocket guides and [materials so they can] streamline the medications.”

REPORTING FROM AMCP NEXUS 2019

Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index predicts long-term outcomes in PAD

PARIS – The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index proved to be an independent predictor of 5-year overall survival as well as the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events in a prospective cohort study of 1,219 patients with peripheral artery disease, Yae Matsuo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is a score calculated with a formula based upon a patient’s height, serum albumin, and the ratio between ideal and actual body weight (Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;82(4):777-83). The GNRI tool has been shown to be an accurate prognosticator for clinical outcomes in patients on hemodialysis and those with heart failure. However, it’s predictive accuracy hasn’t been evaluated in patients with PAD, according to Dr. Matsuo, a cardiologist at Kitakanto Cardiovascular Hospital in Shibukawa, Japan.

“The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index is simple to calculate – so easy – and I think it’s a better predictor than BMI,” she said.

Fifty-six percent of the PAD patients had a GNRI score greater than 98, indicative of no increased risk of malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies. Their 5-year overall survival rate was 81%, compared with 62% in patients with a score of 92-98, 40% in those with a score of 82-91, and 23% with a score of less than 82. Other independent predictors of overall survival in multivariate analysis were age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, ankle brachial index, and C-reactive protein level.

A GNRI score above 98 was also predictive of significantly lower 5-year risk of both major adverse cardiovascular events and the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events than in patients with a score of 98 or less.

The key remaining unanswered question is whether providing timely nutritional support to PAD patients with a low GNRI score will result in improved overall and limb survival and other outcomes.

Dr. Matsuo reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Matsuo Y. ESC CONGRESS 2019. Abstract P1956.

PARIS – The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index proved to be an independent predictor of 5-year overall survival as well as the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events in a prospective cohort study of 1,219 patients with peripheral artery disease, Yae Matsuo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is a score calculated with a formula based upon a patient’s height, serum albumin, and the ratio between ideal and actual body weight (Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;82(4):777-83). The GNRI tool has been shown to be an accurate prognosticator for clinical outcomes in patients on hemodialysis and those with heart failure. However, it’s predictive accuracy hasn’t been evaluated in patients with PAD, according to Dr. Matsuo, a cardiologist at Kitakanto Cardiovascular Hospital in Shibukawa, Japan.

“The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index is simple to calculate – so easy – and I think it’s a better predictor than BMI,” she said.

Fifty-six percent of the PAD patients had a GNRI score greater than 98, indicative of no increased risk of malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies. Their 5-year overall survival rate was 81%, compared with 62% in patients with a score of 92-98, 40% in those with a score of 82-91, and 23% with a score of less than 82. Other independent predictors of overall survival in multivariate analysis were age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, ankle brachial index, and C-reactive protein level.

A GNRI score above 98 was also predictive of significantly lower 5-year risk of both major adverse cardiovascular events and the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events than in patients with a score of 98 or less.

The key remaining unanswered question is whether providing timely nutritional support to PAD patients with a low GNRI score will result in improved overall and limb survival and other outcomes.

Dr. Matsuo reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Matsuo Y. ESC CONGRESS 2019. Abstract P1956.

PARIS – The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index proved to be an independent predictor of 5-year overall survival as well as the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events in a prospective cohort study of 1,219 patients with peripheral artery disease, Yae Matsuo, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is a score calculated with a formula based upon a patient’s height, serum albumin, and the ratio between ideal and actual body weight (Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;82(4):777-83). The GNRI tool has been shown to be an accurate prognosticator for clinical outcomes in patients on hemodialysis and those with heart failure. However, it’s predictive accuracy hasn’t been evaluated in patients with PAD, according to Dr. Matsuo, a cardiologist at Kitakanto Cardiovascular Hospital in Shibukawa, Japan.

“The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index is simple to calculate – so easy – and I think it’s a better predictor than BMI,” she said.

Fifty-six percent of the PAD patients had a GNRI score greater than 98, indicative of no increased risk of malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies. Their 5-year overall survival rate was 81%, compared with 62% in patients with a score of 92-98, 40% in those with a score of 82-91, and 23% with a score of less than 82. Other independent predictors of overall survival in multivariate analysis were age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, ankle brachial index, and C-reactive protein level.

A GNRI score above 98 was also predictive of significantly lower 5-year risk of both major adverse cardiovascular events and the composite of major adverse cardiovascular and limb events than in patients with a score of 98 or less.

The key remaining unanswered question is whether providing timely nutritional support to PAD patients with a low GNRI score will result in improved overall and limb survival and other outcomes.

Dr. Matsuo reported having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Matsuo Y. ESC CONGRESS 2019. Abstract P1956.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

Severe hypoglycemia, poor glycemic control fuels fracture risk in older diabetic patients

Patients with type 2 diabetes and poor glycemic control or severe hypoglycemia may be at greater risk for fracture, according to recent research from a Japanese cohort of older men and postmenopausal women.

“The impacts of severe hypoglycemia and poor glycemic control on fractures appeared to be independent,” noted Yuji Komorita, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine and clinical science, Graduate School of Medical Sciences at Kyushu University, and colleagues. “This study suggests that the glycemic target to prevent fractures may be HbA1c <75 mmol/mol, which is far higher than that used to prevent microvascular complications, and higher than that for older adults with type 2 diabetes.”

Dr. Komorita and colleagues performed a prospective analysis of fracture incidence for 2,755 men and 1,951 postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes in the Fukuoka Diabetes Registry who were mean 66 years old between April 2008 and October 2010. At the start of the study, the researchers assessed patient diabetes duration, previous fracture history, physical activity, alcohol and smoking status, whether patients were treated for diabetic retinopathy with laser photocoagulation, and their history of coronary artery disease or stroke. Patients were followed for a median 5.3 years, during which fractures were assessed through an annual self-administered questionnaire, with the results stratified by glycemic control and hypoglycemia.