User login

Children and COVID: U.S. sees almost 1 million new cases

Another record week for COVID-19 brought almost 1 million new cases to the children of the United States, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The pre-Omicron high for new cases in a week – 252,000 during the Delta surge of the late summer and early fall – has been surpassed each of the last 3 weeks and now stands at 981,000 (Jan. 7-13), according to the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report. Over the 3-week stretch from Dec. 17 to Jan. 13, weekly cases increased by 394%.

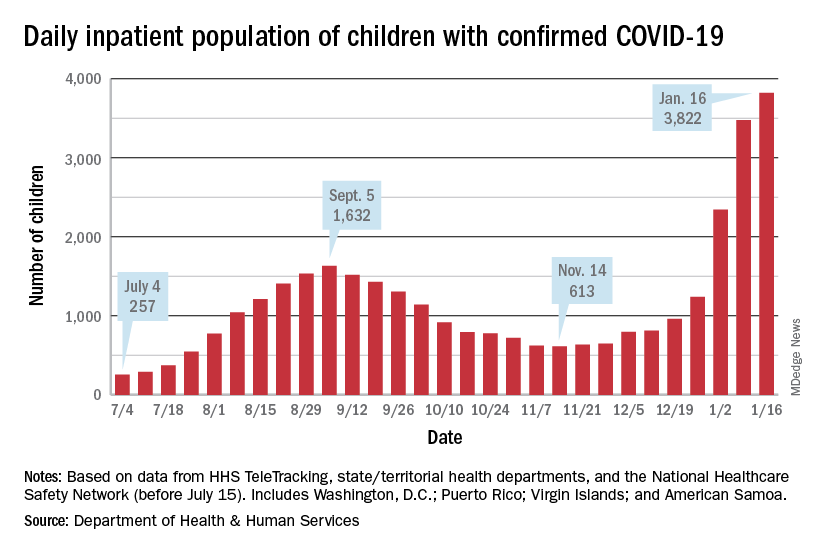

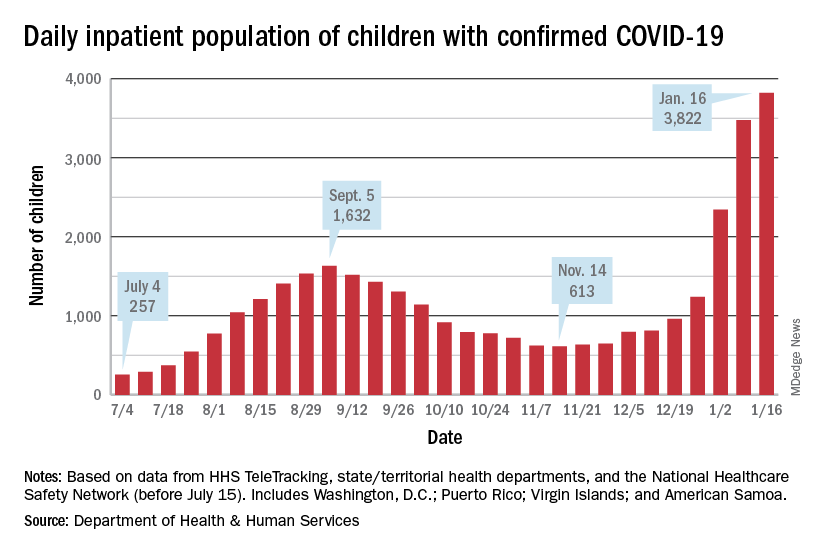

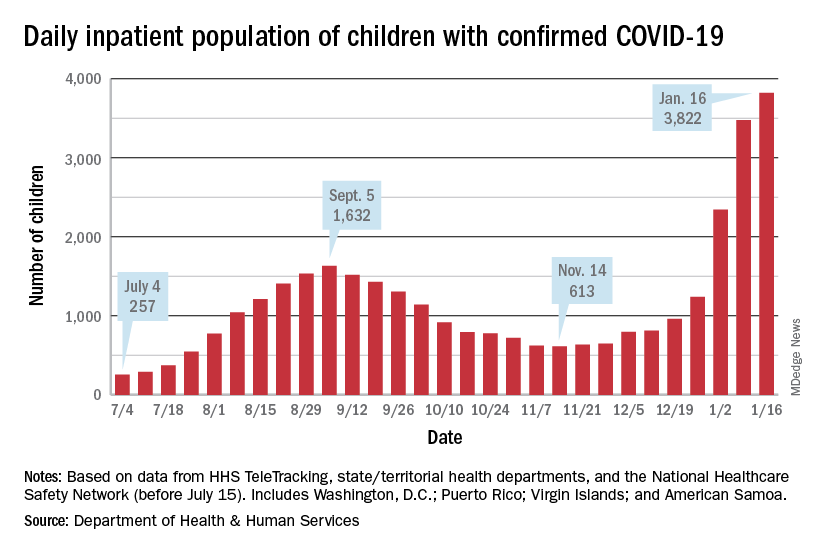

Hospitalizations also climbed to new heights, as daily admissions reached 1.23 per 100,000 children on Jan. 14, an increase of 547% since Nov. 30, when the rate was 0.19 per 100,000. Before Omicron, the highest rate for children was 0.47 per 100,000, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The inpatient population count, meanwhile, has followed suit. On Jan. 16, there were 3,822 children hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, which is 523% higher than the 613 children who were hospitalized on Nov. 14, according to the Department of Health & Human Services. In the last week, though, the population was up by just 10%.

The one thing that has not surged in the last few weeks is vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, the weekly count of those who have received at least one dose dropped by 34% over the last 5 weeks, falling from 527,000 for Dec.11-17 to 347,000 during Jan. 8-14, the CDC said on the COVID Data Tracker, which also noted that just 18.4% of this age group is fully vaccinated.

The situation was reversed in children aged 12-15, who were up by 36% over that same time, but their numbers were much smaller: 78,000 for the week of Dec. 11-17 and 106,000 for Jan. 8-14. Those aged 16-17 were up by just 4% over that 5-week span, the CDC data show.

Over the course of the entire pandemic, almost 9.5 million cases of COVID-19 in children have been reported, and children represent 17.8% of all cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York but including New York City), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Three states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas) stopped public reporting over the summer, but many states count individuals up to age 19 as children, and others (South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia) go up to age 20, the AAP and CHA noted. The CDC, by comparison, puts the number of cases for those aged 0-17 at 8.3 million, but that estimate is based on only 51 million of the nearly 67 million U.S. cases as of Jan. 18.

Another record week for COVID-19 brought almost 1 million new cases to the children of the United States, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The pre-Omicron high for new cases in a week – 252,000 during the Delta surge of the late summer and early fall – has been surpassed each of the last 3 weeks and now stands at 981,000 (Jan. 7-13), according to the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report. Over the 3-week stretch from Dec. 17 to Jan. 13, weekly cases increased by 394%.

Hospitalizations also climbed to new heights, as daily admissions reached 1.23 per 100,000 children on Jan. 14, an increase of 547% since Nov. 30, when the rate was 0.19 per 100,000. Before Omicron, the highest rate for children was 0.47 per 100,000, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The inpatient population count, meanwhile, has followed suit. On Jan. 16, there were 3,822 children hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, which is 523% higher than the 613 children who were hospitalized on Nov. 14, according to the Department of Health & Human Services. In the last week, though, the population was up by just 10%.

The one thing that has not surged in the last few weeks is vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, the weekly count of those who have received at least one dose dropped by 34% over the last 5 weeks, falling from 527,000 for Dec.11-17 to 347,000 during Jan. 8-14, the CDC said on the COVID Data Tracker, which also noted that just 18.4% of this age group is fully vaccinated.

The situation was reversed in children aged 12-15, who were up by 36% over that same time, but their numbers were much smaller: 78,000 for the week of Dec. 11-17 and 106,000 for Jan. 8-14. Those aged 16-17 were up by just 4% over that 5-week span, the CDC data show.

Over the course of the entire pandemic, almost 9.5 million cases of COVID-19 in children have been reported, and children represent 17.8% of all cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York but including New York City), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Three states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas) stopped public reporting over the summer, but many states count individuals up to age 19 as children, and others (South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia) go up to age 20, the AAP and CHA noted. The CDC, by comparison, puts the number of cases for those aged 0-17 at 8.3 million, but that estimate is based on only 51 million of the nearly 67 million U.S. cases as of Jan. 18.

Another record week for COVID-19 brought almost 1 million new cases to the children of the United States, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The pre-Omicron high for new cases in a week – 252,000 during the Delta surge of the late summer and early fall – has been surpassed each of the last 3 weeks and now stands at 981,000 (Jan. 7-13), according to the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report. Over the 3-week stretch from Dec. 17 to Jan. 13, weekly cases increased by 394%.

Hospitalizations also climbed to new heights, as daily admissions reached 1.23 per 100,000 children on Jan. 14, an increase of 547% since Nov. 30, when the rate was 0.19 per 100,000. Before Omicron, the highest rate for children was 0.47 per 100,000, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The inpatient population count, meanwhile, has followed suit. On Jan. 16, there were 3,822 children hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, which is 523% higher than the 613 children who were hospitalized on Nov. 14, according to the Department of Health & Human Services. In the last week, though, the population was up by just 10%.

The one thing that has not surged in the last few weeks is vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, the weekly count of those who have received at least one dose dropped by 34% over the last 5 weeks, falling from 527,000 for Dec.11-17 to 347,000 during Jan. 8-14, the CDC said on the COVID Data Tracker, which also noted that just 18.4% of this age group is fully vaccinated.

The situation was reversed in children aged 12-15, who were up by 36% over that same time, but their numbers were much smaller: 78,000 for the week of Dec. 11-17 and 106,000 for Jan. 8-14. Those aged 16-17 were up by just 4% over that 5-week span, the CDC data show.

Over the course of the entire pandemic, almost 9.5 million cases of COVID-19 in children have been reported, and children represent 17.8% of all cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York but including New York City), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Three states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas) stopped public reporting over the summer, but many states count individuals up to age 19 as children, and others (South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia) go up to age 20, the AAP and CHA noted. The CDC, by comparison, puts the number of cases for those aged 0-17 at 8.3 million, but that estimate is based on only 51 million of the nearly 67 million U.S. cases as of Jan. 18.

Negative home COVID test no ‘free pass’ for kids, study finds

With the country looking increasingly to rapid testing as an off-ramp from the COVID-19 pandemic, a new study shows that the performance of the tests in children falls below standards set by regulatory agencies in the United States and elsewhere for diagnostic accuracy.

Experts said the findings, from a meta-analysis by researchers in the United Kingdom and Germany, underscore that, while a positive result on a rapid test is almost certainly an indicator of infection, negative results often are unreliable and can lead to a false sense of security.

“Real-life performance of current antigen tests for professional use in pediatric populations is below the minimum performance criteria set by WHO, the United States Food and Drug Administration, or the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (U.K.),” according to Naomi Fujita-Rohwerder, PhD, a research associate at the Cologne-based German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), and her colleagues, whose study appears in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

The researchers said that the study suggests that performance of rapid testing in a pediatric population is comparable to that in adults. However, they said they could not identify any studies investigating self-testing in children, which also could affect test performance.

Egon Ozer, MD, PhD, director of the center for pathogen genomics and microbial evolution at Northwestern University in Chicago, said the finding that specificity was high but sensitivity was middling “suggests that we should be very careful about interpreting negative antigen test results in children and recognize that there is a fair amount of uncertainty in the tests in this situation.”

Researchers from IQWiG, which examines the advantages and disadvantages of medical interventions, and the University of Manchester (England), conducted the systematic review and meta-analysis, which they described as the first of its kind to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of rapid point-of-care tests for current SARS-CoV-2 infections in children.

They compiled information from 17 studies with a total 6,355 participants. They compared all antigen tests to reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The studies compared eight antigen tests from six different brands. The rapid antigen tests, available from pharmacies and online stores, are widely used for self-testing in schools and testing toddlers before kindergarten.

The pooled diagnostic sensitivity of antigen tests was 64.2% and specificity was 99.1%.

Dr. Ozer noted that the analysis “was not able to address important outstanding questions such as the likelihood of transmitting infection with a false-negative antigen test versus a true-negative antigen test or how much repeated testing can increase the sensitivity.”

“In Europe, we don’t know how most tests perform in real life,” Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder said. “And even in countries like the United States, where market access is more stringent, we don’t know whether self-testing performed by children or sample collection in toddlers by laypersons has a significant impact on the diagnostic accuracy. Also, diagnostic accuracy estimates reported in our study may not apply to the current omicron or future variants of SARS-CoV-2 or vaccinated children. Hopefully, these essential gaps in the evidence will get addressed soon.”

Dr. Ozer said one takeaway from this study is negative antigen tests should not be considered a “free pass” in children, especially if the child is symptomatic, has been recently exposed to COVID-19, or is planning to spend time with individuals with conditions that place them at high risk for complications of COVID-19 infection. “In such cases, consider getting PCR testing or at least performing a repeat antigen test 36-48 hours after the first negative,” he said.

Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder said the low diagnostic sensitivity may affect the use of the tests. The gaps in evidence her group found in their study point to research needed to support evidence-based decision-making. “In particular, evidence is needed on real-life performance of tests in schools, self-testing performed by children, and kindergarten, [particularly] sample collection in toddlers by laypersons,” she said.

However, she stressed, testing is only a single measure. “Effectively reducing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the current pandemic requires multilayered mitigation measures,” she said. “Rapid testing represents one single layer. It can have its use at the population level, even though the sensitivity of antigen tests is lower than expected. However, antigen-based rapid testing is not a magic bullet: If your kid tests negative, do not disregard other mitigation measures.”

Edward Campbell, PhD, a virologist at Loyola University of Chicago, who serves on the board of LaGrange Elementary School District 102 outside Chicago, said the findings were unsurprising.

“This study generally looks consistent with what is known for adults. These rapid antigen tests are less sensitive than other tests,” said Dr. Campbell, who also runs a testing company for private schools in the Chicago area using reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification technology. Even so, he said, “These tests are still effective at identifying people who are infectious to some degree. Never miss an opportunity to test.”

Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Campbell owns Safeguard Surveillance.

With the country looking increasingly to rapid testing as an off-ramp from the COVID-19 pandemic, a new study shows that the performance of the tests in children falls below standards set by regulatory agencies in the United States and elsewhere for diagnostic accuracy.

Experts said the findings, from a meta-analysis by researchers in the United Kingdom and Germany, underscore that, while a positive result on a rapid test is almost certainly an indicator of infection, negative results often are unreliable and can lead to a false sense of security.

“Real-life performance of current antigen tests for professional use in pediatric populations is below the minimum performance criteria set by WHO, the United States Food and Drug Administration, or the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (U.K.),” according to Naomi Fujita-Rohwerder, PhD, a research associate at the Cologne-based German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), and her colleagues, whose study appears in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

The researchers said that the study suggests that performance of rapid testing in a pediatric population is comparable to that in adults. However, they said they could not identify any studies investigating self-testing in children, which also could affect test performance.

Egon Ozer, MD, PhD, director of the center for pathogen genomics and microbial evolution at Northwestern University in Chicago, said the finding that specificity was high but sensitivity was middling “suggests that we should be very careful about interpreting negative antigen test results in children and recognize that there is a fair amount of uncertainty in the tests in this situation.”

Researchers from IQWiG, which examines the advantages and disadvantages of medical interventions, and the University of Manchester (England), conducted the systematic review and meta-analysis, which they described as the first of its kind to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of rapid point-of-care tests for current SARS-CoV-2 infections in children.

They compiled information from 17 studies with a total 6,355 participants. They compared all antigen tests to reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The studies compared eight antigen tests from six different brands. The rapid antigen tests, available from pharmacies and online stores, are widely used for self-testing in schools and testing toddlers before kindergarten.

The pooled diagnostic sensitivity of antigen tests was 64.2% and specificity was 99.1%.

Dr. Ozer noted that the analysis “was not able to address important outstanding questions such as the likelihood of transmitting infection with a false-negative antigen test versus a true-negative antigen test or how much repeated testing can increase the sensitivity.”

“In Europe, we don’t know how most tests perform in real life,” Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder said. “And even in countries like the United States, where market access is more stringent, we don’t know whether self-testing performed by children or sample collection in toddlers by laypersons has a significant impact on the diagnostic accuracy. Also, diagnostic accuracy estimates reported in our study may not apply to the current omicron or future variants of SARS-CoV-2 or vaccinated children. Hopefully, these essential gaps in the evidence will get addressed soon.”

Dr. Ozer said one takeaway from this study is negative antigen tests should not be considered a “free pass” in children, especially if the child is symptomatic, has been recently exposed to COVID-19, or is planning to spend time with individuals with conditions that place them at high risk for complications of COVID-19 infection. “In such cases, consider getting PCR testing or at least performing a repeat antigen test 36-48 hours after the first negative,” he said.

Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder said the low diagnostic sensitivity may affect the use of the tests. The gaps in evidence her group found in their study point to research needed to support evidence-based decision-making. “In particular, evidence is needed on real-life performance of tests in schools, self-testing performed by children, and kindergarten, [particularly] sample collection in toddlers by laypersons,” she said.

However, she stressed, testing is only a single measure. “Effectively reducing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the current pandemic requires multilayered mitigation measures,” she said. “Rapid testing represents one single layer. It can have its use at the population level, even though the sensitivity of antigen tests is lower than expected. However, antigen-based rapid testing is not a magic bullet: If your kid tests negative, do not disregard other mitigation measures.”

Edward Campbell, PhD, a virologist at Loyola University of Chicago, who serves on the board of LaGrange Elementary School District 102 outside Chicago, said the findings were unsurprising.

“This study generally looks consistent with what is known for adults. These rapid antigen tests are less sensitive than other tests,” said Dr. Campbell, who also runs a testing company for private schools in the Chicago area using reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification technology. Even so, he said, “These tests are still effective at identifying people who are infectious to some degree. Never miss an opportunity to test.”

Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Campbell owns Safeguard Surveillance.

With the country looking increasingly to rapid testing as an off-ramp from the COVID-19 pandemic, a new study shows that the performance of the tests in children falls below standards set by regulatory agencies in the United States and elsewhere for diagnostic accuracy.

Experts said the findings, from a meta-analysis by researchers in the United Kingdom and Germany, underscore that, while a positive result on a rapid test is almost certainly an indicator of infection, negative results often are unreliable and can lead to a false sense of security.

“Real-life performance of current antigen tests for professional use in pediatric populations is below the minimum performance criteria set by WHO, the United States Food and Drug Administration, or the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (U.K.),” according to Naomi Fujita-Rohwerder, PhD, a research associate at the Cologne-based German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), and her colleagues, whose study appears in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

The researchers said that the study suggests that performance of rapid testing in a pediatric population is comparable to that in adults. However, they said they could not identify any studies investigating self-testing in children, which also could affect test performance.

Egon Ozer, MD, PhD, director of the center for pathogen genomics and microbial evolution at Northwestern University in Chicago, said the finding that specificity was high but sensitivity was middling “suggests that we should be very careful about interpreting negative antigen test results in children and recognize that there is a fair amount of uncertainty in the tests in this situation.”

Researchers from IQWiG, which examines the advantages and disadvantages of medical interventions, and the University of Manchester (England), conducted the systematic review and meta-analysis, which they described as the first of its kind to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of rapid point-of-care tests for current SARS-CoV-2 infections in children.

They compiled information from 17 studies with a total 6,355 participants. They compared all antigen tests to reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The studies compared eight antigen tests from six different brands. The rapid antigen tests, available from pharmacies and online stores, are widely used for self-testing in schools and testing toddlers before kindergarten.

The pooled diagnostic sensitivity of antigen tests was 64.2% and specificity was 99.1%.

Dr. Ozer noted that the analysis “was not able to address important outstanding questions such as the likelihood of transmitting infection with a false-negative antigen test versus a true-negative antigen test or how much repeated testing can increase the sensitivity.”

“In Europe, we don’t know how most tests perform in real life,” Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder said. “And even in countries like the United States, where market access is more stringent, we don’t know whether self-testing performed by children or sample collection in toddlers by laypersons has a significant impact on the diagnostic accuracy. Also, diagnostic accuracy estimates reported in our study may not apply to the current omicron or future variants of SARS-CoV-2 or vaccinated children. Hopefully, these essential gaps in the evidence will get addressed soon.”

Dr. Ozer said one takeaway from this study is negative antigen tests should not be considered a “free pass” in children, especially if the child is symptomatic, has been recently exposed to COVID-19, or is planning to spend time with individuals with conditions that place them at high risk for complications of COVID-19 infection. “In such cases, consider getting PCR testing or at least performing a repeat antigen test 36-48 hours after the first negative,” he said.

Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder said the low diagnostic sensitivity may affect the use of the tests. The gaps in evidence her group found in their study point to research needed to support evidence-based decision-making. “In particular, evidence is needed on real-life performance of tests in schools, self-testing performed by children, and kindergarten, [particularly] sample collection in toddlers by laypersons,” she said.

However, she stressed, testing is only a single measure. “Effectively reducing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the current pandemic requires multilayered mitigation measures,” she said. “Rapid testing represents one single layer. It can have its use at the population level, even though the sensitivity of antigen tests is lower than expected. However, antigen-based rapid testing is not a magic bullet: If your kid tests negative, do not disregard other mitigation measures.”

Edward Campbell, PhD, a virologist at Loyola University of Chicago, who serves on the board of LaGrange Elementary School District 102 outside Chicago, said the findings were unsurprising.

“This study generally looks consistent with what is known for adults. These rapid antigen tests are less sensitive than other tests,” said Dr. Campbell, who also runs a testing company for private schools in the Chicago area using reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification technology. Even so, he said, “These tests are still effective at identifying people who are infectious to some degree. Never miss an opportunity to test.”

Dr. Fujita-Rohwerder disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Campbell owns Safeguard Surveillance.

BMJ EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE

Antibiotics used in newborns despite low risk for sepsis

Antibiotics were administered to newborns at low risk for early-onset sepsis as frequently as to newborns with EOS risk factors, based on data from approximately 7,500 infants.

EOS remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, and predicting which newborns are at risk remains a challenge for neonatal care that often drives high rates of antibiotic use, Dustin D. Flannery, DO, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and colleagues wrote.

Antibiotic exposures are associated with short- and long-term adverse effects in both preterm and term infants, which highlights the need for improved risk assessment in this population, the researchers said.

“A robust estimate of EOS risk in relation to delivery characteristics among infants of all gestational ages at birth could significantly contribute to newborn clinical management by identifying newborns unlikely to benefit from empirical antibiotic therapy,” they emphasized.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 7,540 infants born between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2014, at two high-risk perinatal units in Philadelphia. Gestational age ranged from 22 to 43 weeks. Criteria for low risk of EOS were determined via an algorithm that included cesarean delivery (with or without labor or membrane rupture), and no antepartum concerns for intra-amniotic infection or nonreassuring fetal status.

A total of 6,428 infants did not meet the low-risk criteria; another 1,121 infants met the low-risk criteria. The primary outcome of EOS was defined as growth of a pathogen in at least 1 blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid culture obtained at 72 hours or less after birth. Overall, 41 infants who did not meet the low-risk criteria developed EOS; none of the infants who met the low-risk criteria developed EOS. Secondary outcomes included initiation of empirical antibiotics at 72 hours or less after birth and the duration of antibiotic use.

Although fewer low-risk infants received antibiotics, compared with infants with EOS (80.4% vs. 91.0%, P < .001), the duration of antibiotic use was not significantly different between the groups, with an adjusted difference of 0.6 hours.

Among infants who did not meet low-risk criteria, 157 were started on antibiotics for each case of EOS, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Because no cases of EOS were identified in the low-risk group, this proportion could not be calculated but suggests that antibiotic exposure in this group was disproportionately higher for incidence of EOS.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible lack of generalizability to other centers and the use of data from a period before more refined EOS strategies, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the inability to assess the effect of lab results on antibiotic use, a lack of data on the exact indication for delivery, and potential misclassification bias.

Risk assessment tools should not be used alone, but should be used to inform clinical decision-making, the researchers emphasized. However, the results were strengthened by the inclusion of moderately preterm infants, who are rarely studied, and the clinical utility of the risk algorithm used in the study. “The implications of our study include potential adjustments to sepsis risk assessment in term infants, and confirmation and enhancement of previous studies that identify a subset of lower-risk preterm infants,” who may be spared empirical or prolonged antibiotic exposure, they concluded.

Data inform intelligent antibiotic use

“Early-onset sepsis is predominantly caused by exposure of the fetus or neonate to ascending maternal colonization or infection by gastrointestinal or genitourinary bacteria,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Scenarios where there is limited neonatal exposure to these organisms would decrease the risk of development of EOS, therefore it is not surprising that delivery characteristics of low-risk deliveries as defined by investigators – the absence of labor, absence of intra-amniotic infection, rupture of membranes at time of delivery, and cesarean delivery – would have resulted in decreased likelihood of EOS.”

Inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to the development of resistant and more virulent strains of bacteria. A growing body of literature also suggests that early antibiotic usage in newborns may affect the neonatal gut microbiome, which is important for development of the neonatal immune system. Early alterations of the microbiome may have long-term implications,” Dr. Krishna said.

“Understanding the delivery characteristics that increase the risk of EOS are crucial to optimizing the use of antibiotics and thereby minimize potential harm to newborns,” she said. “Studies such as the current study are needed develop EOS prediction tools to improve antibiotic utilization.” More research is needed not only to adequately predict EOS, but to explore how antibiotics affect the neonatal microbiome, and how clinicians can circumvent potential adverse implications with antibiotic use to improve long-term health, Dr. Krishna concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

Antibiotics were administered to newborns at low risk for early-onset sepsis as frequently as to newborns with EOS risk factors, based on data from approximately 7,500 infants.

EOS remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, and predicting which newborns are at risk remains a challenge for neonatal care that often drives high rates of antibiotic use, Dustin D. Flannery, DO, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and colleagues wrote.

Antibiotic exposures are associated with short- and long-term adverse effects in both preterm and term infants, which highlights the need for improved risk assessment in this population, the researchers said.

“A robust estimate of EOS risk in relation to delivery characteristics among infants of all gestational ages at birth could significantly contribute to newborn clinical management by identifying newborns unlikely to benefit from empirical antibiotic therapy,” they emphasized.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 7,540 infants born between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2014, at two high-risk perinatal units in Philadelphia. Gestational age ranged from 22 to 43 weeks. Criteria for low risk of EOS were determined via an algorithm that included cesarean delivery (with or without labor or membrane rupture), and no antepartum concerns for intra-amniotic infection or nonreassuring fetal status.

A total of 6,428 infants did not meet the low-risk criteria; another 1,121 infants met the low-risk criteria. The primary outcome of EOS was defined as growth of a pathogen in at least 1 blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid culture obtained at 72 hours or less after birth. Overall, 41 infants who did not meet the low-risk criteria developed EOS; none of the infants who met the low-risk criteria developed EOS. Secondary outcomes included initiation of empirical antibiotics at 72 hours or less after birth and the duration of antibiotic use.

Although fewer low-risk infants received antibiotics, compared with infants with EOS (80.4% vs. 91.0%, P < .001), the duration of antibiotic use was not significantly different between the groups, with an adjusted difference of 0.6 hours.

Among infants who did not meet low-risk criteria, 157 were started on antibiotics for each case of EOS, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Because no cases of EOS were identified in the low-risk group, this proportion could not be calculated but suggests that antibiotic exposure in this group was disproportionately higher for incidence of EOS.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible lack of generalizability to other centers and the use of data from a period before more refined EOS strategies, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the inability to assess the effect of lab results on antibiotic use, a lack of data on the exact indication for delivery, and potential misclassification bias.

Risk assessment tools should not be used alone, but should be used to inform clinical decision-making, the researchers emphasized. However, the results were strengthened by the inclusion of moderately preterm infants, who are rarely studied, and the clinical utility of the risk algorithm used in the study. “The implications of our study include potential adjustments to sepsis risk assessment in term infants, and confirmation and enhancement of previous studies that identify a subset of lower-risk preterm infants,” who may be spared empirical or prolonged antibiotic exposure, they concluded.

Data inform intelligent antibiotic use

“Early-onset sepsis is predominantly caused by exposure of the fetus or neonate to ascending maternal colonization or infection by gastrointestinal or genitourinary bacteria,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Scenarios where there is limited neonatal exposure to these organisms would decrease the risk of development of EOS, therefore it is not surprising that delivery characteristics of low-risk deliveries as defined by investigators – the absence of labor, absence of intra-amniotic infection, rupture of membranes at time of delivery, and cesarean delivery – would have resulted in decreased likelihood of EOS.”

Inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to the development of resistant and more virulent strains of bacteria. A growing body of literature also suggests that early antibiotic usage in newborns may affect the neonatal gut microbiome, which is important for development of the neonatal immune system. Early alterations of the microbiome may have long-term implications,” Dr. Krishna said.

“Understanding the delivery characteristics that increase the risk of EOS are crucial to optimizing the use of antibiotics and thereby minimize potential harm to newborns,” she said. “Studies such as the current study are needed develop EOS prediction tools to improve antibiotic utilization.” More research is needed not only to adequately predict EOS, but to explore how antibiotics affect the neonatal microbiome, and how clinicians can circumvent potential adverse implications with antibiotic use to improve long-term health, Dr. Krishna concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

Antibiotics were administered to newborns at low risk for early-onset sepsis as frequently as to newborns with EOS risk factors, based on data from approximately 7,500 infants.

EOS remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, and predicting which newborns are at risk remains a challenge for neonatal care that often drives high rates of antibiotic use, Dustin D. Flannery, DO, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and colleagues wrote.

Antibiotic exposures are associated with short- and long-term adverse effects in both preterm and term infants, which highlights the need for improved risk assessment in this population, the researchers said.

“A robust estimate of EOS risk in relation to delivery characteristics among infants of all gestational ages at birth could significantly contribute to newborn clinical management by identifying newborns unlikely to benefit from empirical antibiotic therapy,” they emphasized.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 7,540 infants born between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2014, at two high-risk perinatal units in Philadelphia. Gestational age ranged from 22 to 43 weeks. Criteria for low risk of EOS were determined via an algorithm that included cesarean delivery (with or without labor or membrane rupture), and no antepartum concerns for intra-amniotic infection or nonreassuring fetal status.

A total of 6,428 infants did not meet the low-risk criteria; another 1,121 infants met the low-risk criteria. The primary outcome of EOS was defined as growth of a pathogen in at least 1 blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid culture obtained at 72 hours or less after birth. Overall, 41 infants who did not meet the low-risk criteria developed EOS; none of the infants who met the low-risk criteria developed EOS. Secondary outcomes included initiation of empirical antibiotics at 72 hours or less after birth and the duration of antibiotic use.

Although fewer low-risk infants received antibiotics, compared with infants with EOS (80.4% vs. 91.0%, P < .001), the duration of antibiotic use was not significantly different between the groups, with an adjusted difference of 0.6 hours.

Among infants who did not meet low-risk criteria, 157 were started on antibiotics for each case of EOS, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Because no cases of EOS were identified in the low-risk group, this proportion could not be calculated but suggests that antibiotic exposure in this group was disproportionately higher for incidence of EOS.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible lack of generalizability to other centers and the use of data from a period before more refined EOS strategies, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the inability to assess the effect of lab results on antibiotic use, a lack of data on the exact indication for delivery, and potential misclassification bias.

Risk assessment tools should not be used alone, but should be used to inform clinical decision-making, the researchers emphasized. However, the results were strengthened by the inclusion of moderately preterm infants, who are rarely studied, and the clinical utility of the risk algorithm used in the study. “The implications of our study include potential adjustments to sepsis risk assessment in term infants, and confirmation and enhancement of previous studies that identify a subset of lower-risk preterm infants,” who may be spared empirical or prolonged antibiotic exposure, they concluded.

Data inform intelligent antibiotic use

“Early-onset sepsis is predominantly caused by exposure of the fetus or neonate to ascending maternal colonization or infection by gastrointestinal or genitourinary bacteria,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Scenarios where there is limited neonatal exposure to these organisms would decrease the risk of development of EOS, therefore it is not surprising that delivery characteristics of low-risk deliveries as defined by investigators – the absence of labor, absence of intra-amniotic infection, rupture of membranes at time of delivery, and cesarean delivery – would have resulted in decreased likelihood of EOS.”

Inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to the development of resistant and more virulent strains of bacteria. A growing body of literature also suggests that early antibiotic usage in newborns may affect the neonatal gut microbiome, which is important for development of the neonatal immune system. Early alterations of the microbiome may have long-term implications,” Dr. Krishna said.

“Understanding the delivery characteristics that increase the risk of EOS are crucial to optimizing the use of antibiotics and thereby minimize potential harm to newborns,” she said. “Studies such as the current study are needed develop EOS prediction tools to improve antibiotic utilization.” More research is needed not only to adequately predict EOS, but to explore how antibiotics affect the neonatal microbiome, and how clinicians can circumvent potential adverse implications with antibiotic use to improve long-term health, Dr. Krishna concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Epstein-Barr virus a likely leading cause of multiple sclerosis

This study is the first to provide compelling evidence of a causal link between EBV and MS, principal investigator Alberto Ascherio, MD, DrPH, professor of epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, and professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

The “prevailing” view has been that MS is “an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology,” said Dr. Ascherio. “Now we know MS is a complication of a viral infection.” With this knowledge, he added, “we can redirect research” to find antiviral drugs to treat the disease.

The study was published online Jan. 13 in Science.

Unique dataset

A chronic disease of the central nervous system, MS involves an inflammatory attack on the myelin sheath and the axons it insulates. The disease affects 2.8 million people worldwide.

EBV is a human herpesvirus that can cause infectious mononucleosis. After infection, it persists in latent form in B-lymphocytes.

EBV is common and infects about 95% of adults. Most individuals are already infected with the virus by age 18 or 20 years, making it difficult to study uninfected populations, said Dr. Ascherio.

However, access to a “huge” database of more than 10 million active-duty U.S. service personnel made this possible, he said.

Service members are screened for HIV at the start of their service care and biennially thereafter. The investigators used stored blood samples to determine the relation between EBV infection and MS over a 20-year period from 1993 to 2013.

Researchers examined 801 MS case patients and 1,566 matched controls without MS. Most individuals were under 20 at the time of their first blood collection. Symptom onset for those who developed MS was a median of 10 years after the first sample was obtained.

Only one of the 801 MS case patients had no serologic evidence of EBV. This individual may have been infected with the virus after the last blood collection, failed to seroconvert in response to infection, or was misdiagnosed, the investigators note.

The hazard ratio for MS between EBV seroconversion versus persistent EBV seronegative was 32.4 (95% CI, 4.3-245.3; P < .001).

An MS vaccine?

MS risk was not increased after infection with cytomegalovirus, a herpesvirus that is transmitted through saliva, as is EBV.

Researchers measured serum concentrations of neurofilament light chain (sNflL), a biomarker of neuroaxonal degeneration, in samples from EBV-negative individuals at baseline. There were no signs of neuroaxonal degeneration before EBV seroconversion in subjects who later developed MS.

This indicates that “EBV infection preceded not only symptom onset but also the time of the first detectable pathological mechanisms underlying MS,” the investigators note.

The very magnitude of increased MS risk of MS observed EBV almost completely rules out confounding by known risk factors. Smoking and vitamin D deficiency double the risk, and genetic predisposition and childhood obesity also only raise the risks of MS to a “moderate” degree, said Dr. Ascherio.

It’s not clear why only some people infected with EBV go on to develop MS, he said.

The idea that reverse causation – that immune dysregulation during the preclinical phase of MS increases susceptibility to EBV infection – is unlikely, the investigators note. For instance, EBV seroconversion occurs before elevation of sNfL levels, an early marker of preclinical MS.

Since most MS cases appear to be caused by EBV, a suitable vaccine might thwart the disease. “A vaccine could, in theory, prevent infection and prevent MS,” said Dr. Ascherio, adding that there’s ongoing work to develop such a vaccine.

Another approach is to target the virus driving MS disease progression. Developing appropriate antivirals might treat and even cure MS, said Dr. Ascherio.

‘Compelling data’

In an accompanying commentary, William H. Robinson, MD, PhD, professor, Division of Immunology and Rheumatology, department of medicine, Stanford (Calif.) University, and a colleague said the study findings “provide compelling data that implicate EBV as the trigger for the development of MS.”

The mechanism or mechanisms by which EBV leads to MS “remain elusive,” the commentary authors write.

“Possibilities include molecular mimicry, through which EBV viral protein sequences mimic human myelin proteins and other CNS proteins and thereby induce autoimmunity against myelin and CNS antigens,” they note.

As other factors, including genetic susceptibility, are important to MS, EBV infection is likely necessary but not sufficient to trigger MS, said the commentary. “Infection with EBV is the initial pathogenic step in MS, but additional fuses must be ignited for the full pathophysiology.”

The commentary authors query whether there may be “new opportunities” for therapy with vaccines or antivirals. “Now that the initial trigger for MS has been identified, perhaps MS could be eradicated.”

In a statement from the Science Media Center, an independent venture promoting views from the scientific community, two other experts offered their take on the study.

Paul Farrell, PhD, professor of tumor virology, Imperial College London, said the paper “provides very clear confirmation of a causal role for EBV in most cases of MS.”

While there’s evidence that a vaccine can prevent the EBV disease infectious mononucleosis, no vaccine candidate has yet prevented the virus from infecting and establishing long-term persistence in people, noted Dr. Farrell.

“So, at this stage it is not clear whether a vaccine of the types currently being developed would be able to prevent the long-term effects of EBV in MS,” he said.

Daniel Davis, PhD, professor of immunology, University of Manchester, United Kingdom, commented that the value of this new discovery is not an immediate medical cure or treatment but is “a major step forward” in understanding MS.

The study “sets up new research working out the precise details of how this virus can sometimes lead to an autoimmune disease,” said Dr. Davis. “There is no shortage of ideas in how this might happen in principle and hopefully the correct details will emerge soon.”

The study received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the German Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Dr. Ascherio reports no relevant financial relaitonships. Dr. Robinson is a coinventor on a patent application filed by Stanford University that includes antibodies to EBV. Dr. Farrell reports serving on an ad hoc review panel for GSK on EBV vaccines in 2019 as a one off. He has a current grant from MRC on EBV biology, including some EBV sequence variation, but the grant is not about MS. Dr. Davis reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This study is the first to provide compelling evidence of a causal link between EBV and MS, principal investigator Alberto Ascherio, MD, DrPH, professor of epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, and professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

The “prevailing” view has been that MS is “an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology,” said Dr. Ascherio. “Now we know MS is a complication of a viral infection.” With this knowledge, he added, “we can redirect research” to find antiviral drugs to treat the disease.

The study was published online Jan. 13 in Science.

Unique dataset

A chronic disease of the central nervous system, MS involves an inflammatory attack on the myelin sheath and the axons it insulates. The disease affects 2.8 million people worldwide.

EBV is a human herpesvirus that can cause infectious mononucleosis. After infection, it persists in latent form in B-lymphocytes.

EBV is common and infects about 95% of adults. Most individuals are already infected with the virus by age 18 or 20 years, making it difficult to study uninfected populations, said Dr. Ascherio.

However, access to a “huge” database of more than 10 million active-duty U.S. service personnel made this possible, he said.

Service members are screened for HIV at the start of their service care and biennially thereafter. The investigators used stored blood samples to determine the relation between EBV infection and MS over a 20-year period from 1993 to 2013.

Researchers examined 801 MS case patients and 1,566 matched controls without MS. Most individuals were under 20 at the time of their first blood collection. Symptom onset for those who developed MS was a median of 10 years after the first sample was obtained.

Only one of the 801 MS case patients had no serologic evidence of EBV. This individual may have been infected with the virus after the last blood collection, failed to seroconvert in response to infection, or was misdiagnosed, the investigators note.

The hazard ratio for MS between EBV seroconversion versus persistent EBV seronegative was 32.4 (95% CI, 4.3-245.3; P < .001).

An MS vaccine?

MS risk was not increased after infection with cytomegalovirus, a herpesvirus that is transmitted through saliva, as is EBV.

Researchers measured serum concentrations of neurofilament light chain (sNflL), a biomarker of neuroaxonal degeneration, in samples from EBV-negative individuals at baseline. There were no signs of neuroaxonal degeneration before EBV seroconversion in subjects who later developed MS.

This indicates that “EBV infection preceded not only symptom onset but also the time of the first detectable pathological mechanisms underlying MS,” the investigators note.

The very magnitude of increased MS risk of MS observed EBV almost completely rules out confounding by known risk factors. Smoking and vitamin D deficiency double the risk, and genetic predisposition and childhood obesity also only raise the risks of MS to a “moderate” degree, said Dr. Ascherio.

It’s not clear why only some people infected with EBV go on to develop MS, he said.

The idea that reverse causation – that immune dysregulation during the preclinical phase of MS increases susceptibility to EBV infection – is unlikely, the investigators note. For instance, EBV seroconversion occurs before elevation of sNfL levels, an early marker of preclinical MS.

Since most MS cases appear to be caused by EBV, a suitable vaccine might thwart the disease. “A vaccine could, in theory, prevent infection and prevent MS,” said Dr. Ascherio, adding that there’s ongoing work to develop such a vaccine.

Another approach is to target the virus driving MS disease progression. Developing appropriate antivirals might treat and even cure MS, said Dr. Ascherio.

‘Compelling data’

In an accompanying commentary, William H. Robinson, MD, PhD, professor, Division of Immunology and Rheumatology, department of medicine, Stanford (Calif.) University, and a colleague said the study findings “provide compelling data that implicate EBV as the trigger for the development of MS.”

The mechanism or mechanisms by which EBV leads to MS “remain elusive,” the commentary authors write.

“Possibilities include molecular mimicry, through which EBV viral protein sequences mimic human myelin proteins and other CNS proteins and thereby induce autoimmunity against myelin and CNS antigens,” they note.

As other factors, including genetic susceptibility, are important to MS, EBV infection is likely necessary but not sufficient to trigger MS, said the commentary. “Infection with EBV is the initial pathogenic step in MS, but additional fuses must be ignited for the full pathophysiology.”

The commentary authors query whether there may be “new opportunities” for therapy with vaccines or antivirals. “Now that the initial trigger for MS has been identified, perhaps MS could be eradicated.”

In a statement from the Science Media Center, an independent venture promoting views from the scientific community, two other experts offered their take on the study.

Paul Farrell, PhD, professor of tumor virology, Imperial College London, said the paper “provides very clear confirmation of a causal role for EBV in most cases of MS.”

While there’s evidence that a vaccine can prevent the EBV disease infectious mononucleosis, no vaccine candidate has yet prevented the virus from infecting and establishing long-term persistence in people, noted Dr. Farrell.

“So, at this stage it is not clear whether a vaccine of the types currently being developed would be able to prevent the long-term effects of EBV in MS,” he said.

Daniel Davis, PhD, professor of immunology, University of Manchester, United Kingdom, commented that the value of this new discovery is not an immediate medical cure or treatment but is “a major step forward” in understanding MS.

The study “sets up new research working out the precise details of how this virus can sometimes lead to an autoimmune disease,” said Dr. Davis. “There is no shortage of ideas in how this might happen in principle and hopefully the correct details will emerge soon.”

The study received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the German Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Dr. Ascherio reports no relevant financial relaitonships. Dr. Robinson is a coinventor on a patent application filed by Stanford University that includes antibodies to EBV. Dr. Farrell reports serving on an ad hoc review panel for GSK on EBV vaccines in 2019 as a one off. He has a current grant from MRC on EBV biology, including some EBV sequence variation, but the grant is not about MS. Dr. Davis reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This study is the first to provide compelling evidence of a causal link between EBV and MS, principal investigator Alberto Ascherio, MD, DrPH, professor of epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, and professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

The “prevailing” view has been that MS is “an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology,” said Dr. Ascherio. “Now we know MS is a complication of a viral infection.” With this knowledge, he added, “we can redirect research” to find antiviral drugs to treat the disease.

The study was published online Jan. 13 in Science.

Unique dataset

A chronic disease of the central nervous system, MS involves an inflammatory attack on the myelin sheath and the axons it insulates. The disease affects 2.8 million people worldwide.

EBV is a human herpesvirus that can cause infectious mononucleosis. After infection, it persists in latent form in B-lymphocytes.

EBV is common and infects about 95% of adults. Most individuals are already infected with the virus by age 18 or 20 years, making it difficult to study uninfected populations, said Dr. Ascherio.

However, access to a “huge” database of more than 10 million active-duty U.S. service personnel made this possible, he said.

Service members are screened for HIV at the start of their service care and biennially thereafter. The investigators used stored blood samples to determine the relation between EBV infection and MS over a 20-year period from 1993 to 2013.

Researchers examined 801 MS case patients and 1,566 matched controls without MS. Most individuals were under 20 at the time of their first blood collection. Symptom onset for those who developed MS was a median of 10 years after the first sample was obtained.

Only one of the 801 MS case patients had no serologic evidence of EBV. This individual may have been infected with the virus after the last blood collection, failed to seroconvert in response to infection, or was misdiagnosed, the investigators note.

The hazard ratio for MS between EBV seroconversion versus persistent EBV seronegative was 32.4 (95% CI, 4.3-245.3; P < .001).

An MS vaccine?

MS risk was not increased after infection with cytomegalovirus, a herpesvirus that is transmitted through saliva, as is EBV.

Researchers measured serum concentrations of neurofilament light chain (sNflL), a biomarker of neuroaxonal degeneration, in samples from EBV-negative individuals at baseline. There were no signs of neuroaxonal degeneration before EBV seroconversion in subjects who later developed MS.

This indicates that “EBV infection preceded not only symptom onset but also the time of the first detectable pathological mechanisms underlying MS,” the investigators note.

The very magnitude of increased MS risk of MS observed EBV almost completely rules out confounding by known risk factors. Smoking and vitamin D deficiency double the risk, and genetic predisposition and childhood obesity also only raise the risks of MS to a “moderate” degree, said Dr. Ascherio.

It’s not clear why only some people infected with EBV go on to develop MS, he said.

The idea that reverse causation – that immune dysregulation during the preclinical phase of MS increases susceptibility to EBV infection – is unlikely, the investigators note. For instance, EBV seroconversion occurs before elevation of sNfL levels, an early marker of preclinical MS.

Since most MS cases appear to be caused by EBV, a suitable vaccine might thwart the disease. “A vaccine could, in theory, prevent infection and prevent MS,” said Dr. Ascherio, adding that there’s ongoing work to develop such a vaccine.

Another approach is to target the virus driving MS disease progression. Developing appropriate antivirals might treat and even cure MS, said Dr. Ascherio.

‘Compelling data’

In an accompanying commentary, William H. Robinson, MD, PhD, professor, Division of Immunology and Rheumatology, department of medicine, Stanford (Calif.) University, and a colleague said the study findings “provide compelling data that implicate EBV as the trigger for the development of MS.”

The mechanism or mechanisms by which EBV leads to MS “remain elusive,” the commentary authors write.

“Possibilities include molecular mimicry, through which EBV viral protein sequences mimic human myelin proteins and other CNS proteins and thereby induce autoimmunity against myelin and CNS antigens,” they note.

As other factors, including genetic susceptibility, are important to MS, EBV infection is likely necessary but not sufficient to trigger MS, said the commentary. “Infection with EBV is the initial pathogenic step in MS, but additional fuses must be ignited for the full pathophysiology.”

The commentary authors query whether there may be “new opportunities” for therapy with vaccines or antivirals. “Now that the initial trigger for MS has been identified, perhaps MS could be eradicated.”

In a statement from the Science Media Center, an independent venture promoting views from the scientific community, two other experts offered their take on the study.

Paul Farrell, PhD, professor of tumor virology, Imperial College London, said the paper “provides very clear confirmation of a causal role for EBV in most cases of MS.”

While there’s evidence that a vaccine can prevent the EBV disease infectious mononucleosis, no vaccine candidate has yet prevented the virus from infecting and establishing long-term persistence in people, noted Dr. Farrell.

“So, at this stage it is not clear whether a vaccine of the types currently being developed would be able to prevent the long-term effects of EBV in MS,” he said.

Daniel Davis, PhD, professor of immunology, University of Manchester, United Kingdom, commented that the value of this new discovery is not an immediate medical cure or treatment but is “a major step forward” in understanding MS.

The study “sets up new research working out the precise details of how this virus can sometimes lead to an autoimmune disease,” said Dr. Davis. “There is no shortage of ideas in how this might happen in principle and hopefully the correct details will emerge soon.”

The study received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the German Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Dr. Ascherio reports no relevant financial relaitonships. Dr. Robinson is a coinventor on a patent application filed by Stanford University that includes antibodies to EBV. Dr. Farrell reports serving on an ad hoc review panel for GSK on EBV vaccines in 2019 as a one off. He has a current grant from MRC on EBV biology, including some EBV sequence variation, but the grant is not about MS. Dr. Davis reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SCIENCE

Wilderness Medical Society issues clinical guidelines for tick-borne illness

The recently published “Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Tick-Borne Illness,” from the Wilderness Medical Society, are a good compilation of treatment suggestions but are not, in fact, new recommendations, lead author Benjamin Ho, MD, of Southern Wisconsin Emergency Associates in Janesville, acknowledged in an interview.

Dr. Ho emphasized that the focus of the report was on “practitioners who practice in resource-limited settings” and are “the group’s way of solidifying a ... standard of practice” for such physicians. Dr. Ho also said that, while “a lot of the recommendations aren’t well supported, the risk-benefit ratio, we believe, supports the recommendations.”

The article first reviewed the different types of ticks and their distribution in the United States, the specific pathogen associated with each, the disease it causes, and comments about seasonal variations in biting behavior. Another table outlines the most common clinical syndromes, typical lab findings, recommended diagnostic testing, and antibiotic treatments. A third section contains images of different types of ticks and photos of ticks in various life-cycle stages and different levels of engorgement.

The authors were careful to note: “Several tick species are able to carry multiple pathogens. In one study, nearly 25% of Ixodes were coinfected with some combination of the bacteria or parasites causing Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, or babesiosis. Although TBI [tick-borne illness] diagnosis is not the focus of this [clinical practice guideline], providers should be aware of high rates of coinfection; the presence of one TBI should in many instances prompt testing for others.”

In terms of recommendations for preventing TBIs, the authors challenge the suggestion of wearing light-colored clothing. For repellents, they recommend DEET, picaridin, and permethrin. And they also give instructions for laundering clothing and removing ticks.

One recommendation is controversial: that of providing single-dose doxycycline as prophylaxis against Lyme disease. Dr. Ho stresses that this was only for “high-risk” tick bites, defined as a tick bite from an identified Ixodes vector species in which the tick was attached for at least 36 hours and that occurred in an endemic area.

The recommendation for prophylactic doxycycline originated with an article by Robert Nadelman and colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine and has been strongly challenged by ILADS (International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society) physicians, including Daniel Cameron, MD, and others.

Sam Donta, MD, a recent member of the Department of Health & Human Services Tick-borne Working Group and a member of the Infectious Disease Society of America, said in an interview: “The problem with the one-dose doxycycline is you may not begin to develop symptoms until 2 months later.” It might mask the early symptoms of Lyme. “My impression is that the doxycycline – even the single dose – might have abrogated the ability to see an immune response. The idea, though, if you’ve had a tick bite, is to do nothing and to wait for symptoms to develop. That becomes a little bit more complex. But even then, you could choose to follow the patient and see the patient in 2 weeks and then get blood testing.”

Dr. Donta added: “I think the screening test is inadequate. So you have to go directly to the Western blot. And you have to do both the IgM and IgG” and look for specific bands.

Dr. Donta emphasized that patients should be encouraged to save any ticks that were attached and that, if at all possible, ticks should be sent to a reference lab for testing before committing a patient to a course of antibiotics. There is no harm in that brief delay, he said, and most labs can identify an array of pathogens.

The Wilderness Society guidelines on TBIs provide a good overview for clinicians practicing in limited resource settings and mirror those from the IDSA.

Dr. Ho and Dr. Donta reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The recently published “Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Tick-Borne Illness,” from the Wilderness Medical Society, are a good compilation of treatment suggestions but are not, in fact, new recommendations, lead author Benjamin Ho, MD, of Southern Wisconsin Emergency Associates in Janesville, acknowledged in an interview.

Dr. Ho emphasized that the focus of the report was on “practitioners who practice in resource-limited settings” and are “the group’s way of solidifying a ... standard of practice” for such physicians. Dr. Ho also said that, while “a lot of the recommendations aren’t well supported, the risk-benefit ratio, we believe, supports the recommendations.”

The article first reviewed the different types of ticks and their distribution in the United States, the specific pathogen associated with each, the disease it causes, and comments about seasonal variations in biting behavior. Another table outlines the most common clinical syndromes, typical lab findings, recommended diagnostic testing, and antibiotic treatments. A third section contains images of different types of ticks and photos of ticks in various life-cycle stages and different levels of engorgement.

The authors were careful to note: “Several tick species are able to carry multiple pathogens. In one study, nearly 25% of Ixodes were coinfected with some combination of the bacteria or parasites causing Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, or babesiosis. Although TBI [tick-borne illness] diagnosis is not the focus of this [clinical practice guideline], providers should be aware of high rates of coinfection; the presence of one TBI should in many instances prompt testing for others.”

In terms of recommendations for preventing TBIs, the authors challenge the suggestion of wearing light-colored clothing. For repellents, they recommend DEET, picaridin, and permethrin. And they also give instructions for laundering clothing and removing ticks.

One recommendation is controversial: that of providing single-dose doxycycline as prophylaxis against Lyme disease. Dr. Ho stresses that this was only for “high-risk” tick bites, defined as a tick bite from an identified Ixodes vector species in which the tick was attached for at least 36 hours and that occurred in an endemic area.

The recommendation for prophylactic doxycycline originated with an article by Robert Nadelman and colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine and has been strongly challenged by ILADS (International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society) physicians, including Daniel Cameron, MD, and others.

Sam Donta, MD, a recent member of the Department of Health & Human Services Tick-borne Working Group and a member of the Infectious Disease Society of America, said in an interview: “The problem with the one-dose doxycycline is you may not begin to develop symptoms until 2 months later.” It might mask the early symptoms of Lyme. “My impression is that the doxycycline – even the single dose – might have abrogated the ability to see an immune response. The idea, though, if you’ve had a tick bite, is to do nothing and to wait for symptoms to develop. That becomes a little bit more complex. But even then, you could choose to follow the patient and see the patient in 2 weeks and then get blood testing.”

Dr. Donta added: “I think the screening test is inadequate. So you have to go directly to the Western blot. And you have to do both the IgM and IgG” and look for specific bands.

Dr. Donta emphasized that patients should be encouraged to save any ticks that were attached and that, if at all possible, ticks should be sent to a reference lab for testing before committing a patient to a course of antibiotics. There is no harm in that brief delay, he said, and most labs can identify an array of pathogens.

The Wilderness Society guidelines on TBIs provide a good overview for clinicians practicing in limited resource settings and mirror those from the IDSA.

Dr. Ho and Dr. Donta reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The recently published “Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Tick-Borne Illness,” from the Wilderness Medical Society, are a good compilation of treatment suggestions but are not, in fact, new recommendations, lead author Benjamin Ho, MD, of Southern Wisconsin Emergency Associates in Janesville, acknowledged in an interview.

Dr. Ho emphasized that the focus of the report was on “practitioners who practice in resource-limited settings” and are “the group’s way of solidifying a ... standard of practice” for such physicians. Dr. Ho also said that, while “a lot of the recommendations aren’t well supported, the risk-benefit ratio, we believe, supports the recommendations.”

The article first reviewed the different types of ticks and their distribution in the United States, the specific pathogen associated with each, the disease it causes, and comments about seasonal variations in biting behavior. Another table outlines the most common clinical syndromes, typical lab findings, recommended diagnostic testing, and antibiotic treatments. A third section contains images of different types of ticks and photos of ticks in various life-cycle stages and different levels of engorgement.

The authors were careful to note: “Several tick species are able to carry multiple pathogens. In one study, nearly 25% of Ixodes were coinfected with some combination of the bacteria or parasites causing Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, or babesiosis. Although TBI [tick-borne illness] diagnosis is not the focus of this [clinical practice guideline], providers should be aware of high rates of coinfection; the presence of one TBI should in many instances prompt testing for others.”

In terms of recommendations for preventing TBIs, the authors challenge the suggestion of wearing light-colored clothing. For repellents, they recommend DEET, picaridin, and permethrin. And they also give instructions for laundering clothing and removing ticks.

One recommendation is controversial: that of providing single-dose doxycycline as prophylaxis against Lyme disease. Dr. Ho stresses that this was only for “high-risk” tick bites, defined as a tick bite from an identified Ixodes vector species in which the tick was attached for at least 36 hours and that occurred in an endemic area.

The recommendation for prophylactic doxycycline originated with an article by Robert Nadelman and colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine and has been strongly challenged by ILADS (International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society) physicians, including Daniel Cameron, MD, and others.

Sam Donta, MD, a recent member of the Department of Health & Human Services Tick-borne Working Group and a member of the Infectious Disease Society of America, said in an interview: “The problem with the one-dose doxycycline is you may not begin to develop symptoms until 2 months later.” It might mask the early symptoms of Lyme. “My impression is that the doxycycline – even the single dose – might have abrogated the ability to see an immune response. The idea, though, if you’ve had a tick bite, is to do nothing and to wait for symptoms to develop. That becomes a little bit more complex. But even then, you could choose to follow the patient and see the patient in 2 weeks and then get blood testing.”

Dr. Donta added: “I think the screening test is inadequate. So you have to go directly to the Western blot. And you have to do both the IgM and IgG” and look for specific bands.

Dr. Donta emphasized that patients should be encouraged to save any ticks that were attached and that, if at all possible, ticks should be sent to a reference lab for testing before committing a patient to a course of antibiotics. There is no harm in that brief delay, he said, and most labs can identify an array of pathogens.

The Wilderness Society guidelines on TBIs provide a good overview for clinicians practicing in limited resource settings and mirror those from the IDSA.

Dr. Ho and Dr. Donta reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM WILDERNESS ENVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE

ACIP releases new dengue vaccine recommendations

The vaccine is only to be used for children aged 9-16 who live in endemic areas and who have evidence with a specific diagnostic test of prior dengue infection.

Dengue is a mosquito-borne virus found throughout the world, primarily in tropical or subtropical climates. Cases had steadily been increasing to 5.2 million in 2019, and the geographic distribution of cases is broadening with climate change and urbanization. About half of the world’s population is now at risk.

The dengue virus has four serotypes. The first infection may be mild or asymptomatic, but the second one can be life-threatening because of a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement.

The lead author of the new recommendations is Gabriela Paz-Bailey, MD, PhD, division of vector-borne diseases, dengue branch, CDC. She told this news organization that, during the second infection, when there are “low levels of antibodies from that first infection, the antibodies help the virus get inside the cells. There the virus is not killed, and that results in increased viral load, and then that can result in more severe disease and the plasma leakage” syndrome, which can lead to shock, severe bleeding, and organ failure. The death rate for severe dengue is up to 13%.

Previous infection with Zika virus, common in the same areas where dengue is endemic, can also increase the risk for symptomatic and severe dengue for subsequent infections.

In the United States, Puerto Rico is the main focus of control efforts because 95% of domestic dengue cases originate there – almost 30,000 cases between 2010 and 2020, with 11,000 cases and 4,000 hospitalizations occurring in children between the ages of 10 and 19.

Because Aedes aegypti, the primary mosquito vector transmitting dengue, is resistant to all commonly used insecticides in Puerto Rico, preventive efforts have shifted from insecticides to vaccination.

Antibody tests prevaccination

The main concern with the Sanofi’s dengue vaccine is that it could act as an asymptomatic primary dengue infection, in effect priming the body for a severe reaction from antibody-dependent enhancement with a subsequent infection. That is why it’s critical that the vaccine only be given to children with evidence of prior disease.

Dr. Paz-Bailey said: “The CDC came up with recommendations of what the performance of the test used for prevaccination screening should be. And it was 98% specificity and 75% sensitivity. ... But no test by itself was found to have a specificity of 98%, and this is why we’re recommending the two-test algorithm,” in which two different assays are run off the same blood sample, drawn at a prevaccination visit.

If the child has evidence of prior dengue, they can proceed with vaccination to protect against recurrent infection. Dengvaxia is given as a series of three shots over 6 months. Vaccine efficacy is 82% – so not everyone is protected, and additionally, that protection declines over time.

There is concern that it will be difficult to achieve compliance with such a complex regimen. Dr. Paz-Bailey said, “But I think that the trust in vaccines that is highly prevalent for [Puerto] Rico and trusting the health care system, and sort of the importance that is assigned to dengue by providers and by parents because of previous outbreaks and previous experiences is going to help us.” She added, “I think that the COVID experience has been very revealing. And what we have learned is that Puerto Rico has a very strong health care system, a very strong network of vaccine providers. ... Coverage for COVID vaccine is higher than in other parts of the U.S.”

One of the interesting things about dengue is that the first infection can range from asymptomatic to life-threatening. The second infection is generally worse because of this antibody-dependent enhancement phenomenon. Eng Eong Ooi, MD, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology, National University of Singapore, told this news organization, “After you have two infections, you seem to be protected quite well against the remaining two [serotypes]. The vaccine serves as another episode of infection in those who had prior dengue, so then any natural infections after the vaccination in the seropositive become like the outcome of a third or fourth infection.”