User login

Children and COVID: Vaccination a harder sell in the summer

The COVID-19 vaccination effort in the youngest children has begun much more slowly than the most recent rollout for older children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in early November of 2021, based on CDC data last updated on July 7.

That approval, of course, came between the Delta and Omicron surges, when awareness was higher. The low initial uptake among those under age 5, however, was not unexpected by the Biden administration. “That number in and of itself is very much in line with our expectation, and we’re eager to continue working closely with partners to build on this start,” a senior administration official told ABC News.

With approval of the vaccine occurring after the school year was over, parents’ thoughts have been focused more on vacations and less on vaccinations. “Even before these vaccines officially became available, this was going to be a different rollout; it was going to take more time,” the official explained.

Incidence measures continue on different paths

New COVID-19 cases dropped during the latest reporting week (July 1-7), returning to the downward trend that began in late May and then stopped for 1 week (June 24-30), when cases were up by 12.4%, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children also represent a smaller share of cases, probably because of underreporting. “There has been a notable decline in the portion of reported weekly COVID-19 cases that are children,” the two groups said in their weekly COVID report. Although “cases are likely increasingly underreported for all age groups, this decline indicates that children are disproportionately undercounted in reported COVID-19 cases.”

Other measures, however, have been rising slowly but steadily since the spring. New admissions of patients aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID, which were down to 0.13 per 100,000 population in early April, had climbed to 0.39 per 100,000 by July 7, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Emergency department visits continue to show the same upward trend, despite a small decline in early June. A COVID diagnosis was involved in just 0.5% of ED visits in children aged 0-11 years on March 26, but by July 6 the rate was 4.7%. Increases were not as high among older children: From 0.3% on March 26 to 2.5% on July 6 for those aged 12-15 and from 0.3% to 2.4% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC.

The COVID-19 vaccination effort in the youngest children has begun much more slowly than the most recent rollout for older children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in early November of 2021, based on CDC data last updated on July 7.

That approval, of course, came between the Delta and Omicron surges, when awareness was higher. The low initial uptake among those under age 5, however, was not unexpected by the Biden administration. “That number in and of itself is very much in line with our expectation, and we’re eager to continue working closely with partners to build on this start,” a senior administration official told ABC News.

With approval of the vaccine occurring after the school year was over, parents’ thoughts have been focused more on vacations and less on vaccinations. “Even before these vaccines officially became available, this was going to be a different rollout; it was going to take more time,” the official explained.

Incidence measures continue on different paths

New COVID-19 cases dropped during the latest reporting week (July 1-7), returning to the downward trend that began in late May and then stopped for 1 week (June 24-30), when cases were up by 12.4%, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children also represent a smaller share of cases, probably because of underreporting. “There has been a notable decline in the portion of reported weekly COVID-19 cases that are children,” the two groups said in their weekly COVID report. Although “cases are likely increasingly underreported for all age groups, this decline indicates that children are disproportionately undercounted in reported COVID-19 cases.”

Other measures, however, have been rising slowly but steadily since the spring. New admissions of patients aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID, which were down to 0.13 per 100,000 population in early April, had climbed to 0.39 per 100,000 by July 7, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Emergency department visits continue to show the same upward trend, despite a small decline in early June. A COVID diagnosis was involved in just 0.5% of ED visits in children aged 0-11 years on March 26, but by July 6 the rate was 4.7%. Increases were not as high among older children: From 0.3% on March 26 to 2.5% on July 6 for those aged 12-15 and from 0.3% to 2.4% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC.

The COVID-19 vaccination effort in the youngest children has begun much more slowly than the most recent rollout for older children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in early November of 2021, based on CDC data last updated on July 7.

That approval, of course, came between the Delta and Omicron surges, when awareness was higher. The low initial uptake among those under age 5, however, was not unexpected by the Biden administration. “That number in and of itself is very much in line with our expectation, and we’re eager to continue working closely with partners to build on this start,” a senior administration official told ABC News.

With approval of the vaccine occurring after the school year was over, parents’ thoughts have been focused more on vacations and less on vaccinations. “Even before these vaccines officially became available, this was going to be a different rollout; it was going to take more time,” the official explained.

Incidence measures continue on different paths

New COVID-19 cases dropped during the latest reporting week (July 1-7), returning to the downward trend that began in late May and then stopped for 1 week (June 24-30), when cases were up by 12.4%, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children also represent a smaller share of cases, probably because of underreporting. “There has been a notable decline in the portion of reported weekly COVID-19 cases that are children,” the two groups said in their weekly COVID report. Although “cases are likely increasingly underreported for all age groups, this decline indicates that children are disproportionately undercounted in reported COVID-19 cases.”

Other measures, however, have been rising slowly but steadily since the spring. New admissions of patients aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID, which were down to 0.13 per 100,000 population in early April, had climbed to 0.39 per 100,000 by July 7, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Emergency department visits continue to show the same upward trend, despite a small decline in early June. A COVID diagnosis was involved in just 0.5% of ED visits in children aged 0-11 years on March 26, but by July 6 the rate was 4.7%. Increases were not as high among older children: From 0.3% on March 26 to 2.5% on July 6 for those aged 12-15 and from 0.3% to 2.4% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC.

High residual liver cancer risk in HCV-cured cirrhosis

A new study confirms the very high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma faced by patients with cirrhosis who have been cured of hepatitis C, a finding the researchers hope will encourage clinicians to communicate risk information to patients and encourage regular HCC screening.

On average, the predicted probability of HCC in cirrhosis patients was 410 times greater than the equivalent probability in the general population, the study team found.

Hamish Innes, PhD, with Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, and colleagues wrote.

“Central to this is ensuring that cured cirrhosis patients understand the risk of HCC and are provided with appropriate surveillance,” they added.

“Most patients with cirrhosis do not adhere to HCC screening guidelines,” Nina Beri, MD, medical oncologist with New York University Perlmutter Cancer Center, who wasn’t involved in the study, said in an interview.

The “important” finding in this study “should be conveyed to patients, as this may help improve screening adherence rates,” Dr. Beri said.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Findings may help promote screening uptake

Dr. Innes and colleagues compared the predicted probability of HCC in 1,803 Scottish adults (mean age, 50 years; 74% male) with cirrhosis and cured hepatitis C to the background risk in the general population of Scotland.

The mean predicted 3-year probability of HCC at the time of sustained viral response (SVR), determined using the aMAP prognostic model, was 3.64% (range, 0.012%-36.12%).

This contrasts with a 3-year HCC probability in the general population ranging from less than 0.0001% to 0.25% depending on demographics.

All patients with cirrhosis – even those at lowest risk – had a higher probability of HCC than the general population, but there was considerable heterogeneity from one patient to the next.

For example, the mean 3-year predicted probability was 18 times higher in the top quintile (9.8%) versus the lowest quintile (0.5%) of risk, the researchers found.

They could not identify a patient subgroup who exhibited a similar HCC risk profile to the general population, as was their hope going into the study.

Dr. Innes and colleagues have developed an online tool that allows clinicians to frame a patient›s 3-year HCC probability against the equivalent probability in the general population.

In the future, they said the scope of the tool could be extended by incorporating general population data from countries beyond Scotland.

“Our hope is that this tool will springboard patient-clinician discussions about HCC risk, and could mitigate low screening uptake,” Dr. Innes and colleagues wrote.

Curing HCV doesn’t eliminate risk

Commenting on the study, Nancy Reau, MD, section chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said curing HCV is “very important and significantly reduces risk for complications, but it doesn’t return you to the normal population.”

Dr. Reau’s advice to cirrhosis patients: “Get screened twice a year.”

Dr. Beri said, in addition to conveying this risk to patients, “it is also important to disseminate this information to the community and to primary care practices, particularly as some patients may not currently follow in a specialized liver disease clinic.”

Also weighing in, Amit Singal, MD, chief of hepatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said this study highlights that underlying cirrhosis is “the strongest risk factor for the development of HCC.”

In contrast to other cancers, such as breast and colorectal cancer, in which high risk populations can be identified by readily available information such as age and sex, implementation of HCC screening programs requires identification of patients with cirrhosis, Dr. Singal noted.

“Underuse of HCC screening in clinical practice is often related to providers having difficulty at this step in the process and contributes to the high proportion of HCC detected at late stages,” he told this news organization.

“Availability of accurate noninvasive markers of fibrosis will hopefully help with better identification of patients with cirrhosis moving forward,” Dr. Singal said, “although we as hepatologists need to work closely with our primary care colleagues to ensure these tools are used routinely in at-risk patients, such as those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol-associated liver disease, or history of cured (post-SVR) hepatitis C infection.”

The study was supported by the Medical Research Foundation and Public Health Scotland. Dr. Innes, Dr. Beri, Dr. Reau, and Dr. Singal reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study confirms the very high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma faced by patients with cirrhosis who have been cured of hepatitis C, a finding the researchers hope will encourage clinicians to communicate risk information to patients and encourage regular HCC screening.

On average, the predicted probability of HCC in cirrhosis patients was 410 times greater than the equivalent probability in the general population, the study team found.

Hamish Innes, PhD, with Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, and colleagues wrote.

“Central to this is ensuring that cured cirrhosis patients understand the risk of HCC and are provided with appropriate surveillance,” they added.

“Most patients with cirrhosis do not adhere to HCC screening guidelines,” Nina Beri, MD, medical oncologist with New York University Perlmutter Cancer Center, who wasn’t involved in the study, said in an interview.

The “important” finding in this study “should be conveyed to patients, as this may help improve screening adherence rates,” Dr. Beri said.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Findings may help promote screening uptake

Dr. Innes and colleagues compared the predicted probability of HCC in 1,803 Scottish adults (mean age, 50 years; 74% male) with cirrhosis and cured hepatitis C to the background risk in the general population of Scotland.

The mean predicted 3-year probability of HCC at the time of sustained viral response (SVR), determined using the aMAP prognostic model, was 3.64% (range, 0.012%-36.12%).

This contrasts with a 3-year HCC probability in the general population ranging from less than 0.0001% to 0.25% depending on demographics.

All patients with cirrhosis – even those at lowest risk – had a higher probability of HCC than the general population, but there was considerable heterogeneity from one patient to the next.

For example, the mean 3-year predicted probability was 18 times higher in the top quintile (9.8%) versus the lowest quintile (0.5%) of risk, the researchers found.

They could not identify a patient subgroup who exhibited a similar HCC risk profile to the general population, as was their hope going into the study.

Dr. Innes and colleagues have developed an online tool that allows clinicians to frame a patient›s 3-year HCC probability against the equivalent probability in the general population.

In the future, they said the scope of the tool could be extended by incorporating general population data from countries beyond Scotland.

“Our hope is that this tool will springboard patient-clinician discussions about HCC risk, and could mitigate low screening uptake,” Dr. Innes and colleagues wrote.

Curing HCV doesn’t eliminate risk

Commenting on the study, Nancy Reau, MD, section chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said curing HCV is “very important and significantly reduces risk for complications, but it doesn’t return you to the normal population.”

Dr. Reau’s advice to cirrhosis patients: “Get screened twice a year.”

Dr. Beri said, in addition to conveying this risk to patients, “it is also important to disseminate this information to the community and to primary care practices, particularly as some patients may not currently follow in a specialized liver disease clinic.”

Also weighing in, Amit Singal, MD, chief of hepatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said this study highlights that underlying cirrhosis is “the strongest risk factor for the development of HCC.”

In contrast to other cancers, such as breast and colorectal cancer, in which high risk populations can be identified by readily available information such as age and sex, implementation of HCC screening programs requires identification of patients with cirrhosis, Dr. Singal noted.

“Underuse of HCC screening in clinical practice is often related to providers having difficulty at this step in the process and contributes to the high proportion of HCC detected at late stages,” he told this news organization.

“Availability of accurate noninvasive markers of fibrosis will hopefully help with better identification of patients with cirrhosis moving forward,” Dr. Singal said, “although we as hepatologists need to work closely with our primary care colleagues to ensure these tools are used routinely in at-risk patients, such as those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol-associated liver disease, or history of cured (post-SVR) hepatitis C infection.”

The study was supported by the Medical Research Foundation and Public Health Scotland. Dr. Innes, Dr. Beri, Dr. Reau, and Dr. Singal reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study confirms the very high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma faced by patients with cirrhosis who have been cured of hepatitis C, a finding the researchers hope will encourage clinicians to communicate risk information to patients and encourage regular HCC screening.

On average, the predicted probability of HCC in cirrhosis patients was 410 times greater than the equivalent probability in the general population, the study team found.

Hamish Innes, PhD, with Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, and colleagues wrote.

“Central to this is ensuring that cured cirrhosis patients understand the risk of HCC and are provided with appropriate surveillance,” they added.

“Most patients with cirrhosis do not adhere to HCC screening guidelines,” Nina Beri, MD, medical oncologist with New York University Perlmutter Cancer Center, who wasn’t involved in the study, said in an interview.

The “important” finding in this study “should be conveyed to patients, as this may help improve screening adherence rates,” Dr. Beri said.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Findings may help promote screening uptake

Dr. Innes and colleagues compared the predicted probability of HCC in 1,803 Scottish adults (mean age, 50 years; 74% male) with cirrhosis and cured hepatitis C to the background risk in the general population of Scotland.

The mean predicted 3-year probability of HCC at the time of sustained viral response (SVR), determined using the aMAP prognostic model, was 3.64% (range, 0.012%-36.12%).

This contrasts with a 3-year HCC probability in the general population ranging from less than 0.0001% to 0.25% depending on demographics.

All patients with cirrhosis – even those at lowest risk – had a higher probability of HCC than the general population, but there was considerable heterogeneity from one patient to the next.

For example, the mean 3-year predicted probability was 18 times higher in the top quintile (9.8%) versus the lowest quintile (0.5%) of risk, the researchers found.

They could not identify a patient subgroup who exhibited a similar HCC risk profile to the general population, as was their hope going into the study.

Dr. Innes and colleagues have developed an online tool that allows clinicians to frame a patient›s 3-year HCC probability against the equivalent probability in the general population.

In the future, they said the scope of the tool could be extended by incorporating general population data from countries beyond Scotland.

“Our hope is that this tool will springboard patient-clinician discussions about HCC risk, and could mitigate low screening uptake,” Dr. Innes and colleagues wrote.

Curing HCV doesn’t eliminate risk

Commenting on the study, Nancy Reau, MD, section chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said curing HCV is “very important and significantly reduces risk for complications, but it doesn’t return you to the normal population.”

Dr. Reau’s advice to cirrhosis patients: “Get screened twice a year.”

Dr. Beri said, in addition to conveying this risk to patients, “it is also important to disseminate this information to the community and to primary care practices, particularly as some patients may not currently follow in a specialized liver disease clinic.”

Also weighing in, Amit Singal, MD, chief of hepatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said this study highlights that underlying cirrhosis is “the strongest risk factor for the development of HCC.”

In contrast to other cancers, such as breast and colorectal cancer, in which high risk populations can be identified by readily available information such as age and sex, implementation of HCC screening programs requires identification of patients with cirrhosis, Dr. Singal noted.

“Underuse of HCC screening in clinical practice is often related to providers having difficulty at this step in the process and contributes to the high proportion of HCC detected at late stages,” he told this news organization.

“Availability of accurate noninvasive markers of fibrosis will hopefully help with better identification of patients with cirrhosis moving forward,” Dr. Singal said, “although we as hepatologists need to work closely with our primary care colleagues to ensure these tools are used routinely in at-risk patients, such as those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol-associated liver disease, or history of cured (post-SVR) hepatitis C infection.”

The study was supported by the Medical Research Foundation and Public Health Scotland. Dr. Innes, Dr. Beri, Dr. Reau, and Dr. Singal reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Liver disease and death rates fall after hepatitis C treatment barriers are dismantled

As obstacles to hepatitis C treatment uptake were removed, rates of hepatitis-related liver disease in marginalized groups plummeted, according to a new study in Baltimore, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

A community-based cohort study that follows current and former people who inject drugs (PWID) with hepatitis C documented drastic reductions in liver disease and death as effective oral antivirals became more readily accessible there between 2015 and 2019.

The researchers concluded that hepatitis C elimination targets are achievable. But, they warned, uptake is uneven, and more needs to be done to facilitate treatment.

“[The study] gives us a real-world perspective on what’s happening on the ground, in terms of people getting treated,” said first author Javier Cepeda, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, in an interview. “Changing policy, reducing barriers, [and] getting them access to treatment really does have this really important public health benefit.”

” said Maria Corcorran, MD, MPH. Dr. Corcorran, an acting assistant professor for the department of medicine at the University of Washington, was not involved with the study. “It’s just further evidence that we need to really be linking people to care and getting people treated and cured.”

The World Health Organization has called for the disease’s global elimination by 2030. Cure rates top 95%. But, there are so many new cases and so many barriers to detection and treatment that how to develop and roll out a public health response is the most important question in the field, wrote study co-author David L. Thomas, MD, MPH, in a review article in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“Folks who inject drugs ... do well on hep C treatment and have similar rates of sustained virologic response or cure,” said Dr. Corcorran, who runs a low-barrier clinic for people experiencing homelessness.

But, she added, “there are barriers that are still put up to treatment in terms of who can treat and what insurance is going to cover.”

A look at a vulnerable population

The authors studied adults enrolled in ALIVE (AIDS Linked to the Intravenous Experience), a cohort study that has recruited current and former PWID in the Baltimore area since 1988.

Participants visit the clinic twice a year for health-related interviews and blood testing, including HIV serology, hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody and RNA testing, and liver function tests. They are counseled about HCV testing and treatment but do not receive treatment through the study.

Beginning in 2006, researchers added liver stiffness measures (LSMs), a noninvasive measure conducted with transient elastography.

From 2006 to 2019, the authors followed 1,323 ALIVE participants with chronic HCV infection. The primary outcome was LSMs.

Less liver disease, fewer deaths

At baseline, participants’ median age was 49 years; 82% of participants were Black individuals, 71% percent were male, and two-thirds were HIV-negative.

Three percent reported receiving hepatitis C treatment in 2014, which increased to 39% in 2019.

Among 10,350 LSMs, 15% showed cirrhosis at baseline in 2006. In 2015, that rose to 19%, but by 2019, it had fallen to 8%.

By definition, 100% had detectable HCV RNA at baseline. In 2015, 91% still did. By 2019, that rate had fallen to 48%.

Undetectable HCV RNA correlated with lower log LSM in adjusted models (P < .001). It also correlated strongly with lower odds of liver cirrhosis, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.28 (95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.45; P < .001). In addition, it correlated with lower risk for all-cause mortality, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% CI, 0.38-0.77; P < .001).

Limitations include the fact that, although transient elastography is considered the most valid way to detect cirrhosis in people with hepatitis C, liver stiffness has not been validated as a measure of fibrosis among people with a sustained virologic response.

In addition, ALIVE participants are older and more likely to be African American individuals, compared with the general population of PWID in Baltimore, wrote co-author Shruti H. Mehta, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an email exchange with this news organization. That could affect generalizability.

Treatment is crucial

The first direct-acting antiviral (DAA) for hepatitis C was approved in 2011, and an oral fixed-dose combination antiviral was approved in 2014, ushering in treatments with cure rates far exceeding those with interferon-based therapy.

But until recently, Medicaid patients in Maryland seeking DAA therapy for hepatitis C required prior authorization, with initial restrictions related to disease stage, substance use, and provider type, according to Dr. Mehta.

Gradually, those restrictions were lifted, Dr. Mehta added, and all were eliminated by 2019.

Dr. Cepeda urges clinicians to treat patients infected with hepatitis C immediately.

“There are really important implications on both reducing liver disease progression and all-cause mortality,” he said.

“Hep C is just one part of a whole constellation of health care delivery [and] of treating all of the other potential problems that might need to be addressed – especially with people who inject drugs,” Dr. Cepeda added. “Getting them into care is really, really important.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cepeda and Dr. Corcorran report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mehta reports receiving payments or honoraria and travel support from Gilead Sciences, the makers of the oral hepatitis C medication ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (Harvoni), as well as equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts, or other services from Abbott, which sells hepatitis C diagnostics. Dr. Thomas reports ties to Excision Bio and to Merck DSMB.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As obstacles to hepatitis C treatment uptake were removed, rates of hepatitis-related liver disease in marginalized groups plummeted, according to a new study in Baltimore, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

A community-based cohort study that follows current and former people who inject drugs (PWID) with hepatitis C documented drastic reductions in liver disease and death as effective oral antivirals became more readily accessible there between 2015 and 2019.

The researchers concluded that hepatitis C elimination targets are achievable. But, they warned, uptake is uneven, and more needs to be done to facilitate treatment.

“[The study] gives us a real-world perspective on what’s happening on the ground, in terms of people getting treated,” said first author Javier Cepeda, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, in an interview. “Changing policy, reducing barriers, [and] getting them access to treatment really does have this really important public health benefit.”

” said Maria Corcorran, MD, MPH. Dr. Corcorran, an acting assistant professor for the department of medicine at the University of Washington, was not involved with the study. “It’s just further evidence that we need to really be linking people to care and getting people treated and cured.”

The World Health Organization has called for the disease’s global elimination by 2030. Cure rates top 95%. But, there are so many new cases and so many barriers to detection and treatment that how to develop and roll out a public health response is the most important question in the field, wrote study co-author David L. Thomas, MD, MPH, in a review article in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“Folks who inject drugs ... do well on hep C treatment and have similar rates of sustained virologic response or cure,” said Dr. Corcorran, who runs a low-barrier clinic for people experiencing homelessness.

But, she added, “there are barriers that are still put up to treatment in terms of who can treat and what insurance is going to cover.”

A look at a vulnerable population

The authors studied adults enrolled in ALIVE (AIDS Linked to the Intravenous Experience), a cohort study that has recruited current and former PWID in the Baltimore area since 1988.

Participants visit the clinic twice a year for health-related interviews and blood testing, including HIV serology, hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody and RNA testing, and liver function tests. They are counseled about HCV testing and treatment but do not receive treatment through the study.

Beginning in 2006, researchers added liver stiffness measures (LSMs), a noninvasive measure conducted with transient elastography.

From 2006 to 2019, the authors followed 1,323 ALIVE participants with chronic HCV infection. The primary outcome was LSMs.

Less liver disease, fewer deaths

At baseline, participants’ median age was 49 years; 82% of participants were Black individuals, 71% percent were male, and two-thirds were HIV-negative.

Three percent reported receiving hepatitis C treatment in 2014, which increased to 39% in 2019.

Among 10,350 LSMs, 15% showed cirrhosis at baseline in 2006. In 2015, that rose to 19%, but by 2019, it had fallen to 8%.

By definition, 100% had detectable HCV RNA at baseline. In 2015, 91% still did. By 2019, that rate had fallen to 48%.

Undetectable HCV RNA correlated with lower log LSM in adjusted models (P < .001). It also correlated strongly with lower odds of liver cirrhosis, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.28 (95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.45; P < .001). In addition, it correlated with lower risk for all-cause mortality, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% CI, 0.38-0.77; P < .001).

Limitations include the fact that, although transient elastography is considered the most valid way to detect cirrhosis in people with hepatitis C, liver stiffness has not been validated as a measure of fibrosis among people with a sustained virologic response.

In addition, ALIVE participants are older and more likely to be African American individuals, compared with the general population of PWID in Baltimore, wrote co-author Shruti H. Mehta, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an email exchange with this news organization. That could affect generalizability.

Treatment is crucial

The first direct-acting antiviral (DAA) for hepatitis C was approved in 2011, and an oral fixed-dose combination antiviral was approved in 2014, ushering in treatments with cure rates far exceeding those with interferon-based therapy.

But until recently, Medicaid patients in Maryland seeking DAA therapy for hepatitis C required prior authorization, with initial restrictions related to disease stage, substance use, and provider type, according to Dr. Mehta.

Gradually, those restrictions were lifted, Dr. Mehta added, and all were eliminated by 2019.

Dr. Cepeda urges clinicians to treat patients infected with hepatitis C immediately.

“There are really important implications on both reducing liver disease progression and all-cause mortality,” he said.

“Hep C is just one part of a whole constellation of health care delivery [and] of treating all of the other potential problems that might need to be addressed – especially with people who inject drugs,” Dr. Cepeda added. “Getting them into care is really, really important.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cepeda and Dr. Corcorran report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mehta reports receiving payments or honoraria and travel support from Gilead Sciences, the makers of the oral hepatitis C medication ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (Harvoni), as well as equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts, or other services from Abbott, which sells hepatitis C diagnostics. Dr. Thomas reports ties to Excision Bio and to Merck DSMB.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As obstacles to hepatitis C treatment uptake were removed, rates of hepatitis-related liver disease in marginalized groups plummeted, according to a new study in Baltimore, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

A community-based cohort study that follows current and former people who inject drugs (PWID) with hepatitis C documented drastic reductions in liver disease and death as effective oral antivirals became more readily accessible there between 2015 and 2019.

The researchers concluded that hepatitis C elimination targets are achievable. But, they warned, uptake is uneven, and more needs to be done to facilitate treatment.

“[The study] gives us a real-world perspective on what’s happening on the ground, in terms of people getting treated,” said first author Javier Cepeda, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, in an interview. “Changing policy, reducing barriers, [and] getting them access to treatment really does have this really important public health benefit.”

” said Maria Corcorran, MD, MPH. Dr. Corcorran, an acting assistant professor for the department of medicine at the University of Washington, was not involved with the study. “It’s just further evidence that we need to really be linking people to care and getting people treated and cured.”

The World Health Organization has called for the disease’s global elimination by 2030. Cure rates top 95%. But, there are so many new cases and so many barriers to detection and treatment that how to develop and roll out a public health response is the most important question in the field, wrote study co-author David L. Thomas, MD, MPH, in a review article in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“Folks who inject drugs ... do well on hep C treatment and have similar rates of sustained virologic response or cure,” said Dr. Corcorran, who runs a low-barrier clinic for people experiencing homelessness.

But, she added, “there are barriers that are still put up to treatment in terms of who can treat and what insurance is going to cover.”

A look at a vulnerable population

The authors studied adults enrolled in ALIVE (AIDS Linked to the Intravenous Experience), a cohort study that has recruited current and former PWID in the Baltimore area since 1988.

Participants visit the clinic twice a year for health-related interviews and blood testing, including HIV serology, hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody and RNA testing, and liver function tests. They are counseled about HCV testing and treatment but do not receive treatment through the study.

Beginning in 2006, researchers added liver stiffness measures (LSMs), a noninvasive measure conducted with transient elastography.

From 2006 to 2019, the authors followed 1,323 ALIVE participants with chronic HCV infection. The primary outcome was LSMs.

Less liver disease, fewer deaths

At baseline, participants’ median age was 49 years; 82% of participants were Black individuals, 71% percent were male, and two-thirds were HIV-negative.

Three percent reported receiving hepatitis C treatment in 2014, which increased to 39% in 2019.

Among 10,350 LSMs, 15% showed cirrhosis at baseline in 2006. In 2015, that rose to 19%, but by 2019, it had fallen to 8%.

By definition, 100% had detectable HCV RNA at baseline. In 2015, 91% still did. By 2019, that rate had fallen to 48%.

Undetectable HCV RNA correlated with lower log LSM in adjusted models (P < .001). It also correlated strongly with lower odds of liver cirrhosis, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.28 (95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.45; P < .001). In addition, it correlated with lower risk for all-cause mortality, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% CI, 0.38-0.77; P < .001).

Limitations include the fact that, although transient elastography is considered the most valid way to detect cirrhosis in people with hepatitis C, liver stiffness has not been validated as a measure of fibrosis among people with a sustained virologic response.

In addition, ALIVE participants are older and more likely to be African American individuals, compared with the general population of PWID in Baltimore, wrote co-author Shruti H. Mehta, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an email exchange with this news organization. That could affect generalizability.

Treatment is crucial

The first direct-acting antiviral (DAA) for hepatitis C was approved in 2011, and an oral fixed-dose combination antiviral was approved in 2014, ushering in treatments with cure rates far exceeding those with interferon-based therapy.

But until recently, Medicaid patients in Maryland seeking DAA therapy for hepatitis C required prior authorization, with initial restrictions related to disease stage, substance use, and provider type, according to Dr. Mehta.

Gradually, those restrictions were lifted, Dr. Mehta added, and all were eliminated by 2019.

Dr. Cepeda urges clinicians to treat patients infected with hepatitis C immediately.

“There are really important implications on both reducing liver disease progression and all-cause mortality,” he said.

“Hep C is just one part of a whole constellation of health care delivery [and] of treating all of the other potential problems that might need to be addressed – especially with people who inject drugs,” Dr. Cepeda added. “Getting them into care is really, really important.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cepeda and Dr. Corcorran report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mehta reports receiving payments or honoraria and travel support from Gilead Sciences, the makers of the oral hepatitis C medication ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (Harvoni), as well as equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts, or other services from Abbott, which sells hepatitis C diagnostics. Dr. Thomas reports ties to Excision Bio and to Merck DSMB.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Zoster vaccination does not appear to increase flare risk in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease

, according to research published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The authors of the study noted that individuals with IMIDs are at increased risk for herpes zoster and related complications, including postherpetic neuralgia, and that vaccination has been recommended for certain groups of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis, by the American College of Rheumatology and other professional organizations for individuals aged 50 and older.

The study investigators used medical claims from IBM MarketScan, which provided data on patients aged 50-64 years, and data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Medicare on patients aged 65 and older.

They defined presumed flares in three ways: hospitalization/emergency department visits for IMIDs, steroid treatment with a short-acting oral glucocorticoid, or treatment with a parenteral glucocorticoid injection. The investigators conducted a self-controlled case series (SCCS) analysis to examine any temporal link between the RZV and disease flares.

Among enrollees with IMIDs, 14.8% of the 55,654 patients in the MarketScan database and 43.2% of the 160,545 patients in the Medicare database received at least one dose of RZV during 2018-2019. The two-dose series completion within 6 months was 76.6% in the MarketScan group (age range, 50-64 years) and 85.4% among Medicare enrollees (age range, 65 years and older). In the SCCS analysis, 10% and 13% of patients developed flares in the control group as compared to 9%, and 11%-12% in the risk window following one or two doses of RZV among MarketScan and Medicare enrollees, respectively.

Based on these findings, the investigators concluded there was no statistically significant increase in flares subsequent to RZV administration for any IMID in either patients aged 50-64 years or patients aged 65 years and older following the first dose or second dose.

Nilanjana Bose, MD, a rheumatologist with Lonestar Rheumatology, Houston, Texas, who was not involved with the study, said that the research addresses a topic where there is uneasiness, namely vaccination in patients with IMIDs.

“Anytime you are vaccinating a patient with an autoimmune disease, especially one on a biologic, you always worry about the risk of flares,” said Dr. Bose. “Any time you tamper with the immune system, there is a risk of flares.”

The study serves as a clarification for the primary care setting, said Dr. Bose. “A lot of the time, the shingles vaccine is administered not by rheumatology but by primary care or through the pharmacy,” she said. “This study puts them [primary care physicians] at ease.”

Findings from the study reflect that most RZV vaccinations were administered in pharmacies.

One of the weaknesses of the study is that the investigators did not include patients younger than 50 years old, said Dr. Bose. “It would have been nice if they could have looked at younger patients,” she said. “We try to vaccinate all our [immunocompromised] adult patients, even the younger ones, because they are also at risk for shingles.”

Given that there are increasing options of medical therapies in rheumatology that are immunomodulatory, the subject of vaccination for patients is often one of discussion, added Dr. Bose.

Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine, University of California San Diego (UCSD), La Jolla, Calif., and director of the Center for Innovative Therapy in the UCSD Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology, told this news organization that a strength of the study is its large numbers of patients but noted the shortcoming of using claims data. “Claims data has inherent limitations, such as the lack of detailed granular data on the patients,” wrote Dr. Kavanaugh, who was not involved with the study. He described this investigation as “really about the first evidence that I am aware of addressing this issue.”

No funding source was listed. One author disclosed having received research grants and consulting fees received from Pfizer and GSK for unrelated work; the other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Bose and Dr. Kavanaugh had no relevant disclosures.

, according to research published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The authors of the study noted that individuals with IMIDs are at increased risk for herpes zoster and related complications, including postherpetic neuralgia, and that vaccination has been recommended for certain groups of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis, by the American College of Rheumatology and other professional organizations for individuals aged 50 and older.

The study investigators used medical claims from IBM MarketScan, which provided data on patients aged 50-64 years, and data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Medicare on patients aged 65 and older.

They defined presumed flares in three ways: hospitalization/emergency department visits for IMIDs, steroid treatment with a short-acting oral glucocorticoid, or treatment with a parenteral glucocorticoid injection. The investigators conducted a self-controlled case series (SCCS) analysis to examine any temporal link between the RZV and disease flares.

Among enrollees with IMIDs, 14.8% of the 55,654 patients in the MarketScan database and 43.2% of the 160,545 patients in the Medicare database received at least one dose of RZV during 2018-2019. The two-dose series completion within 6 months was 76.6% in the MarketScan group (age range, 50-64 years) and 85.4% among Medicare enrollees (age range, 65 years and older). In the SCCS analysis, 10% and 13% of patients developed flares in the control group as compared to 9%, and 11%-12% in the risk window following one or two doses of RZV among MarketScan and Medicare enrollees, respectively.

Based on these findings, the investigators concluded there was no statistically significant increase in flares subsequent to RZV administration for any IMID in either patients aged 50-64 years or patients aged 65 years and older following the first dose or second dose.

Nilanjana Bose, MD, a rheumatologist with Lonestar Rheumatology, Houston, Texas, who was not involved with the study, said that the research addresses a topic where there is uneasiness, namely vaccination in patients with IMIDs.

“Anytime you are vaccinating a patient with an autoimmune disease, especially one on a biologic, you always worry about the risk of flares,” said Dr. Bose. “Any time you tamper with the immune system, there is a risk of flares.”

The study serves as a clarification for the primary care setting, said Dr. Bose. “A lot of the time, the shingles vaccine is administered not by rheumatology but by primary care or through the pharmacy,” she said. “This study puts them [primary care physicians] at ease.”

Findings from the study reflect that most RZV vaccinations were administered in pharmacies.

One of the weaknesses of the study is that the investigators did not include patients younger than 50 years old, said Dr. Bose. “It would have been nice if they could have looked at younger patients,” she said. “We try to vaccinate all our [immunocompromised] adult patients, even the younger ones, because they are also at risk for shingles.”

Given that there are increasing options of medical therapies in rheumatology that are immunomodulatory, the subject of vaccination for patients is often one of discussion, added Dr. Bose.

Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine, University of California San Diego (UCSD), La Jolla, Calif., and director of the Center for Innovative Therapy in the UCSD Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology, told this news organization that a strength of the study is its large numbers of patients but noted the shortcoming of using claims data. “Claims data has inherent limitations, such as the lack of detailed granular data on the patients,” wrote Dr. Kavanaugh, who was not involved with the study. He described this investigation as “really about the first evidence that I am aware of addressing this issue.”

No funding source was listed. One author disclosed having received research grants and consulting fees received from Pfizer and GSK for unrelated work; the other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Bose and Dr. Kavanaugh had no relevant disclosures.

, according to research published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The authors of the study noted that individuals with IMIDs are at increased risk for herpes zoster and related complications, including postherpetic neuralgia, and that vaccination has been recommended for certain groups of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis, by the American College of Rheumatology and other professional organizations for individuals aged 50 and older.

The study investigators used medical claims from IBM MarketScan, which provided data on patients aged 50-64 years, and data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Medicare on patients aged 65 and older.

They defined presumed flares in three ways: hospitalization/emergency department visits for IMIDs, steroid treatment with a short-acting oral glucocorticoid, or treatment with a parenteral glucocorticoid injection. The investigators conducted a self-controlled case series (SCCS) analysis to examine any temporal link between the RZV and disease flares.

Among enrollees with IMIDs, 14.8% of the 55,654 patients in the MarketScan database and 43.2% of the 160,545 patients in the Medicare database received at least one dose of RZV during 2018-2019. The two-dose series completion within 6 months was 76.6% in the MarketScan group (age range, 50-64 years) and 85.4% among Medicare enrollees (age range, 65 years and older). In the SCCS analysis, 10% and 13% of patients developed flares in the control group as compared to 9%, and 11%-12% in the risk window following one or two doses of RZV among MarketScan and Medicare enrollees, respectively.

Based on these findings, the investigators concluded there was no statistically significant increase in flares subsequent to RZV administration for any IMID in either patients aged 50-64 years or patients aged 65 years and older following the first dose or second dose.

Nilanjana Bose, MD, a rheumatologist with Lonestar Rheumatology, Houston, Texas, who was not involved with the study, said that the research addresses a topic where there is uneasiness, namely vaccination in patients with IMIDs.

“Anytime you are vaccinating a patient with an autoimmune disease, especially one on a biologic, you always worry about the risk of flares,” said Dr. Bose. “Any time you tamper with the immune system, there is a risk of flares.”

The study serves as a clarification for the primary care setting, said Dr. Bose. “A lot of the time, the shingles vaccine is administered not by rheumatology but by primary care or through the pharmacy,” she said. “This study puts them [primary care physicians] at ease.”

Findings from the study reflect that most RZV vaccinations were administered in pharmacies.

One of the weaknesses of the study is that the investigators did not include patients younger than 50 years old, said Dr. Bose. “It would have been nice if they could have looked at younger patients,” she said. “We try to vaccinate all our [immunocompromised] adult patients, even the younger ones, because they are also at risk for shingles.”

Given that there are increasing options of medical therapies in rheumatology that are immunomodulatory, the subject of vaccination for patients is often one of discussion, added Dr. Bose.

Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine, University of California San Diego (UCSD), La Jolla, Calif., and director of the Center for Innovative Therapy in the UCSD Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology, told this news organization that a strength of the study is its large numbers of patients but noted the shortcoming of using claims data. “Claims data has inherent limitations, such as the lack of detailed granular data on the patients,” wrote Dr. Kavanaugh, who was not involved with the study. He described this investigation as “really about the first evidence that I am aware of addressing this issue.”

No funding source was listed. One author disclosed having received research grants and consulting fees received from Pfizer and GSK for unrelated work; the other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Bose and Dr. Kavanaugh had no relevant disclosures.

Erythematous Papules on the Ears

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

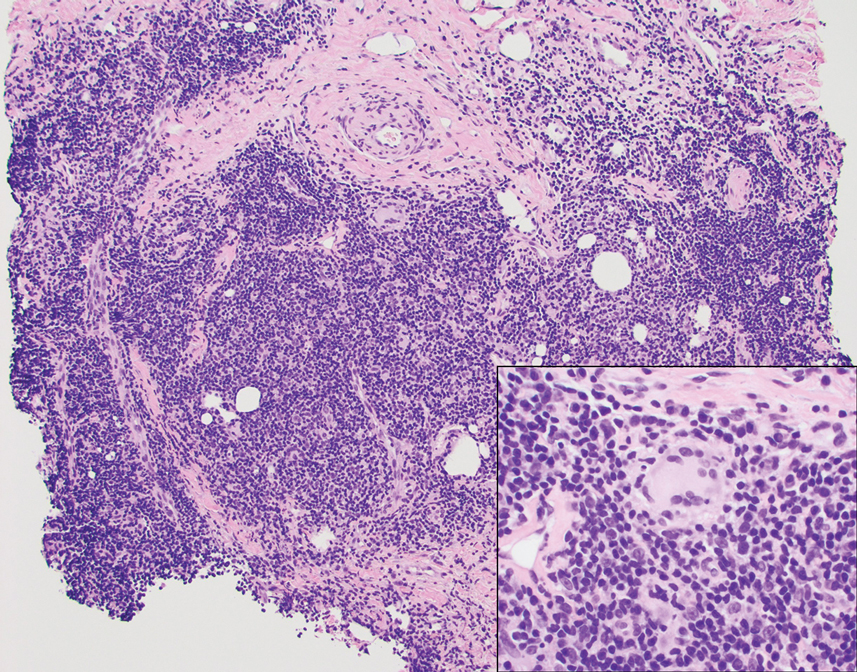

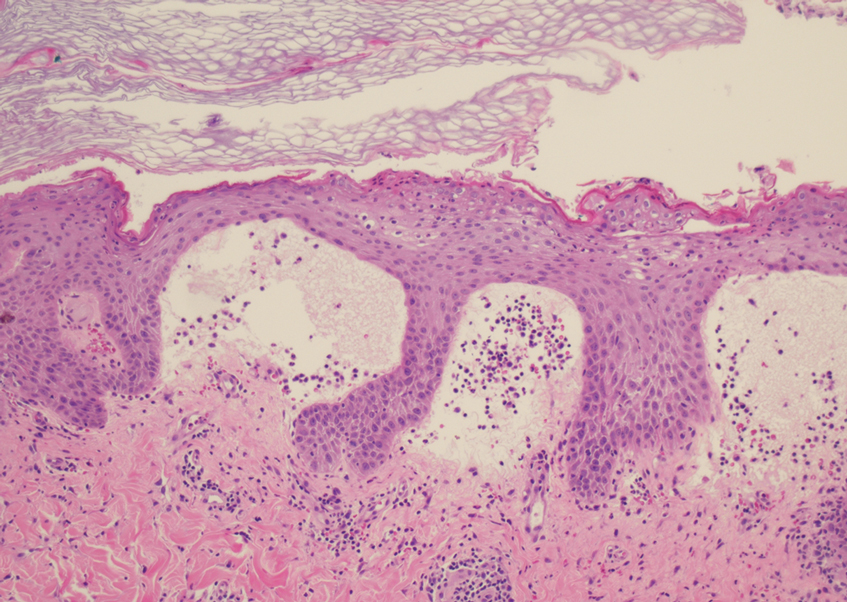

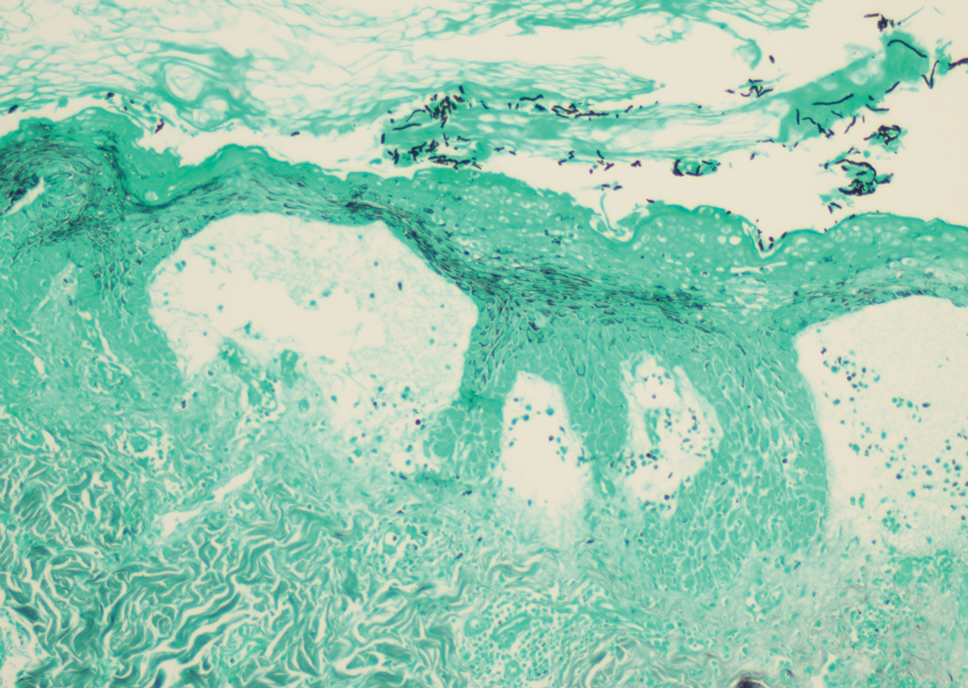

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

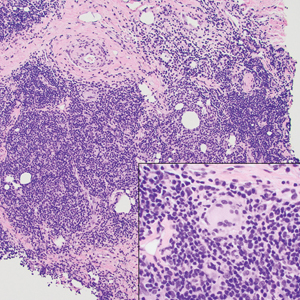

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

A 53-year-old man with a history of atopic dermatitis presented with pain and redness of the lobules of both ears of 9 months’ duration. He had no known allergies and took no medications. He lived in suburban Virginia and had not recently traveled outside of the region. Physical examination revealed tender erythematous and edematous nodules on the lobules of both ears (top). There was no evidence of arthritis or neurologic deficits. A punch biopsy was performed (bottom).

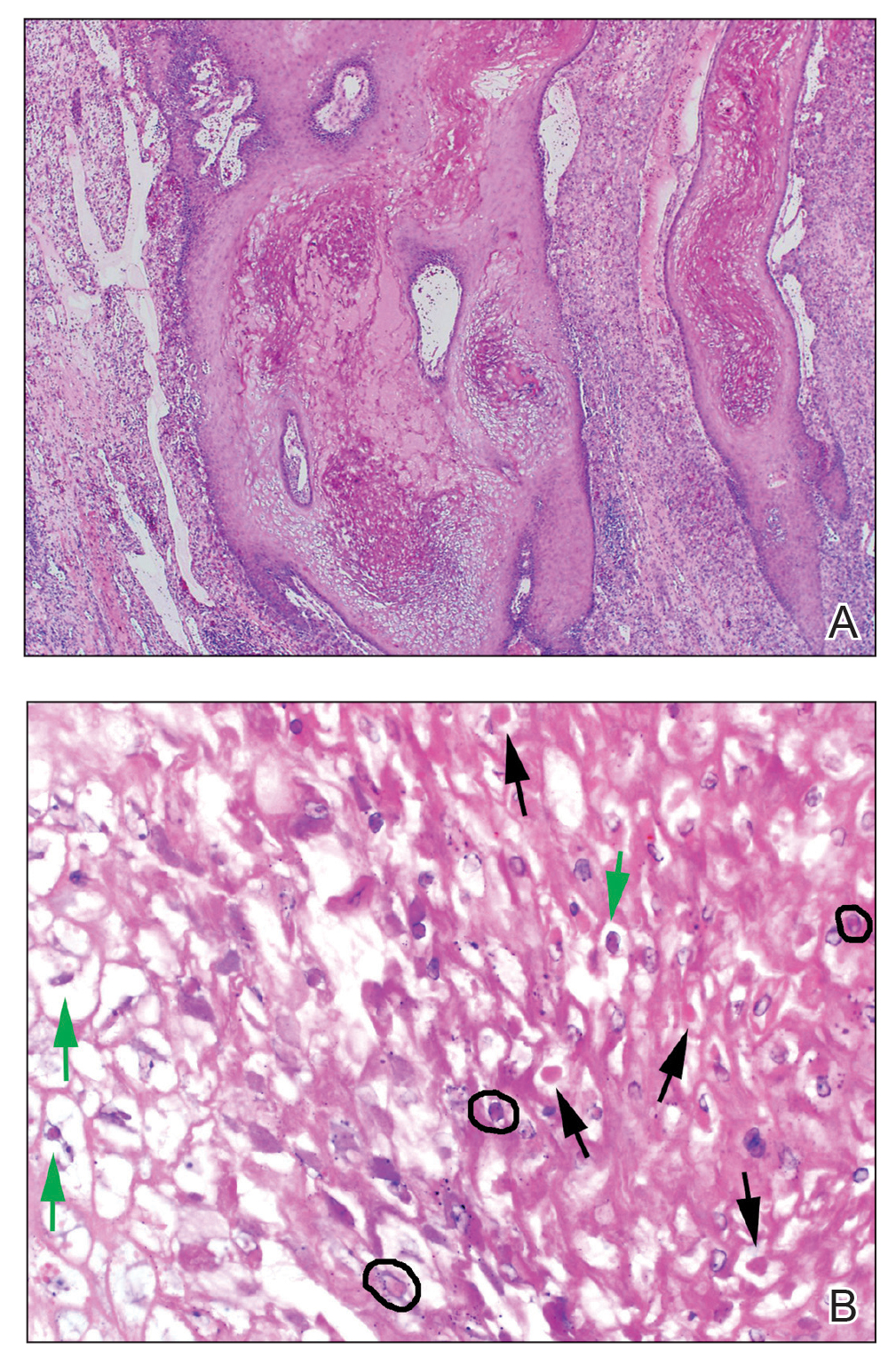

Orf Virus in Humans: Case Series and Clinical Review

A patient presenting with a hand pustule is a phenomenon encountered worldwide requiring careful history-taking. Some occupations, activities, and various religious practices (eg, Eid al-Adha, Passover, Easter) have been implicated worldwide in orf infection. In the United States, orf virus usually is spread from infected animal hosts to humans. Herein, we review the differential for a single hand pustule, which includes both infectious and noninfectious causes. Recognizing orf virus as the etiology of a cutaneous hand pustule in patients is important, as misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary invasive testing and/or treatments with suboptimal clinical outcomes.

Case Series

When conducting a search for orf virus cases at our institution (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa), 5 patient cases were identified.

Patient 1—A 27-year-old otherwise healthy woman presented to clinic with a tender red bump on the right ring finger that had been slowly growing over the course of 2 weeks and had recently started to bleed. A social history revealed that she owned several goats, which she frequently milked; 1 of the goats had a cyst on the mouth, which she popped approximately 1 to 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the lesion on the finger. She also endorsed that she owned several cattle and various other animals with which she had frequent contact. A biopsy was obtained with features consistent with orf virus.

Patient 2—A 33-year-old man presented to clinic with a lesion of concern on the left index finger. Several days prior to presentation, the patient had visited the emergency department for swelling and erythema of the same finger after cutting himself with a knife while preparing sheep meat. Radiographs were normal, and the patient was referred to dermatology. In clinic, there was a 0.5-cm fluctuant mass on the distal interphalangeal joint of the third finger. The patient declined a biopsy, and the lesion healed over 4 to 6 weeks without complication.

Patient 3—A 38-year-old man presented to clinic with 2 painless, large, round nodules on the right proximal index finger, with open friable centers noted on physical examination (Figure 1). The patient reported cutting the finger while preparing sheep meat several days prior. The nodules had been present for a few weeks and continued to grow. A punch biopsy revealed evidence of parapoxvirus infection consistent with a diagnosis of orf.

Patient 4—A 48-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a bleeding lesion on the left middle finger. Physical examination revealed an exophytic, friable, ulcerated nodule on the dorsal aspect of the left middle finger (Figure 2). Upon further questioning, the patient mentioned that he handled raw lamb meat after cutting the finger. A punch biopsy was obtained and was consistent with orf virus infection.