User login

Fungated Eroded Plaque on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

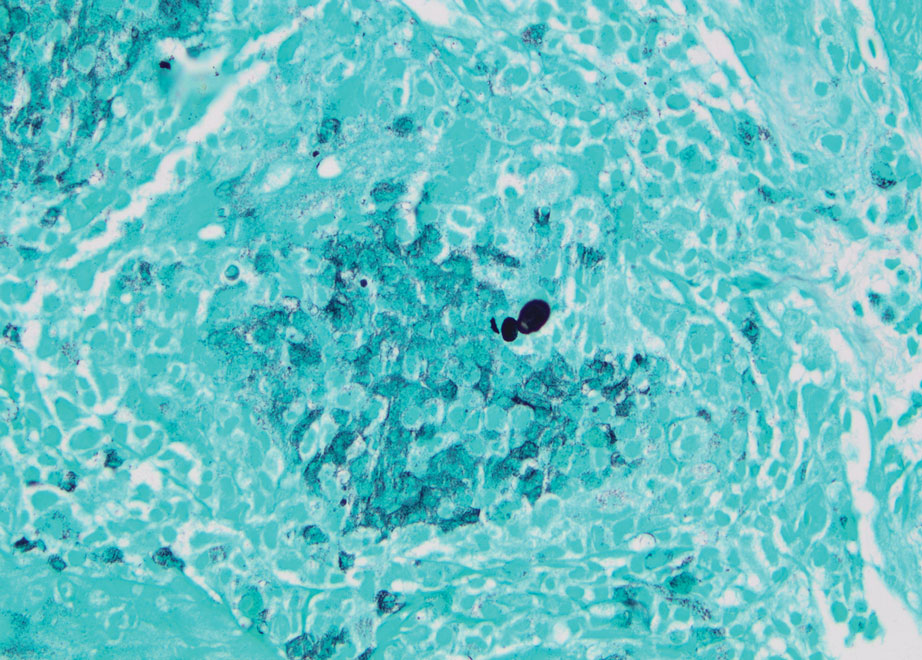

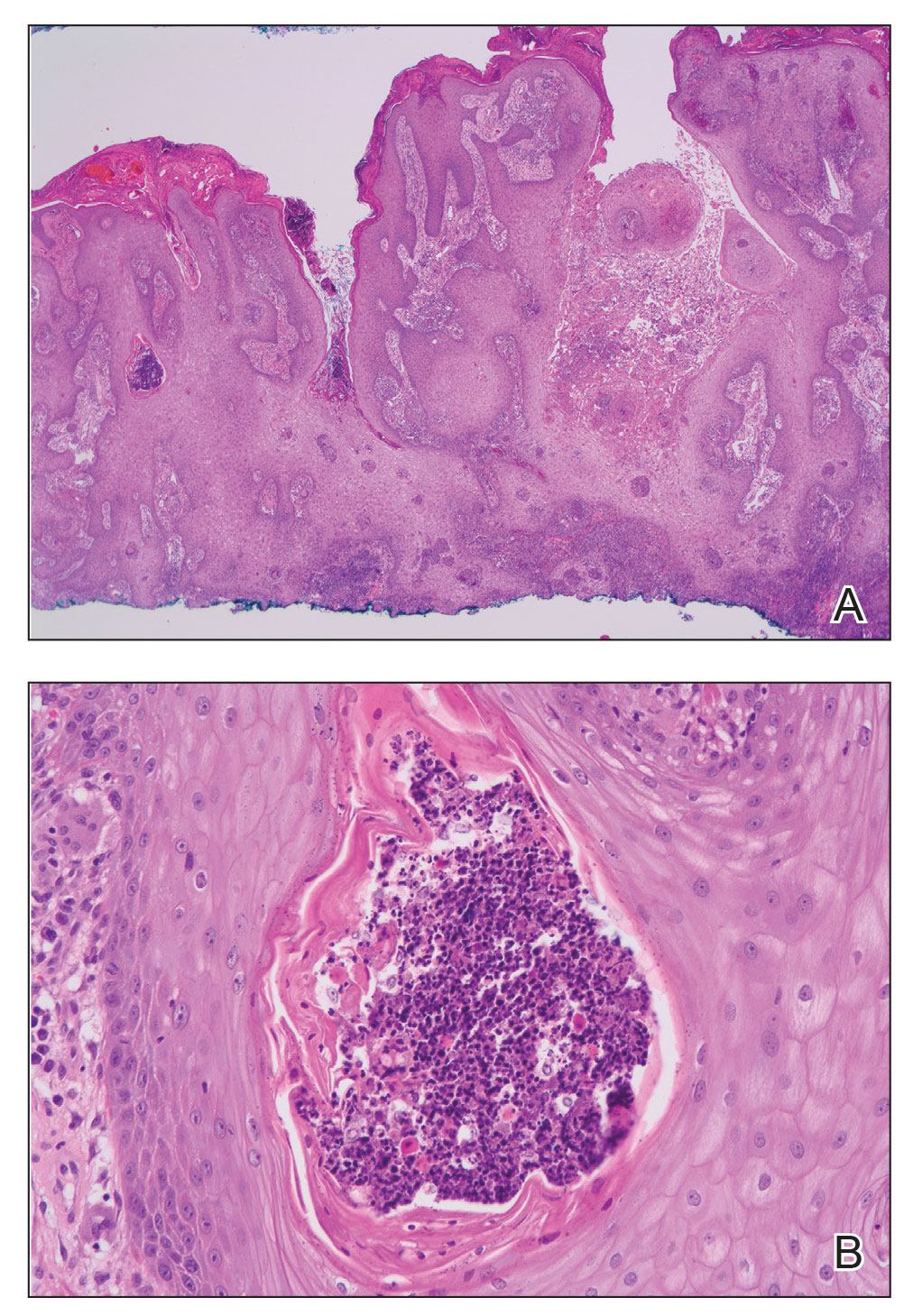

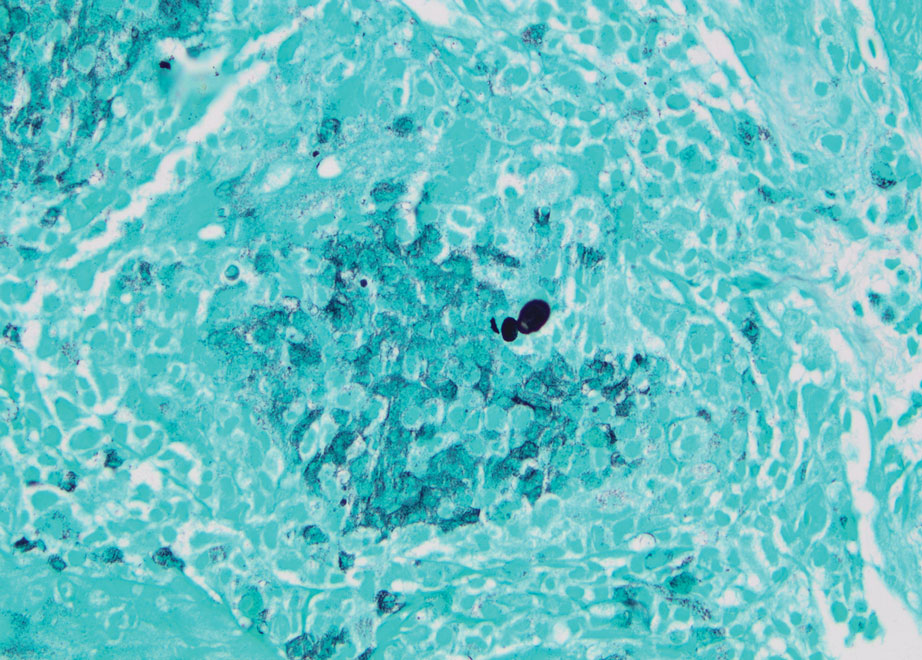

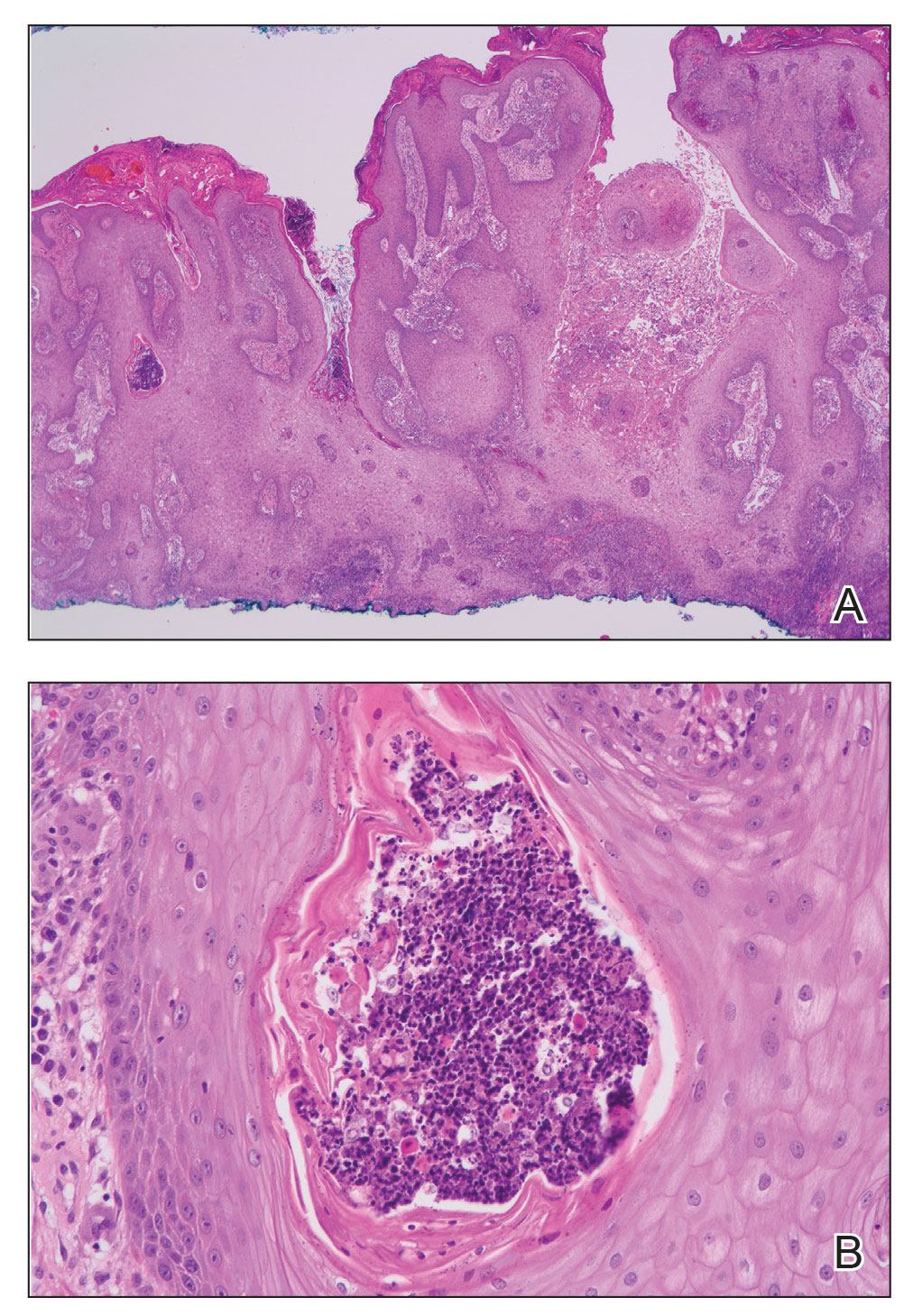

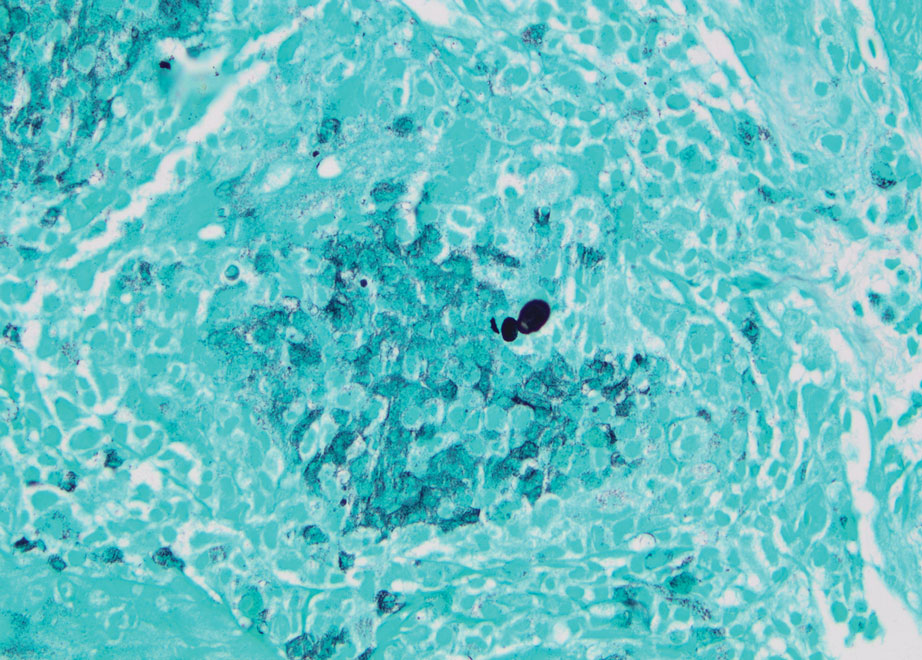

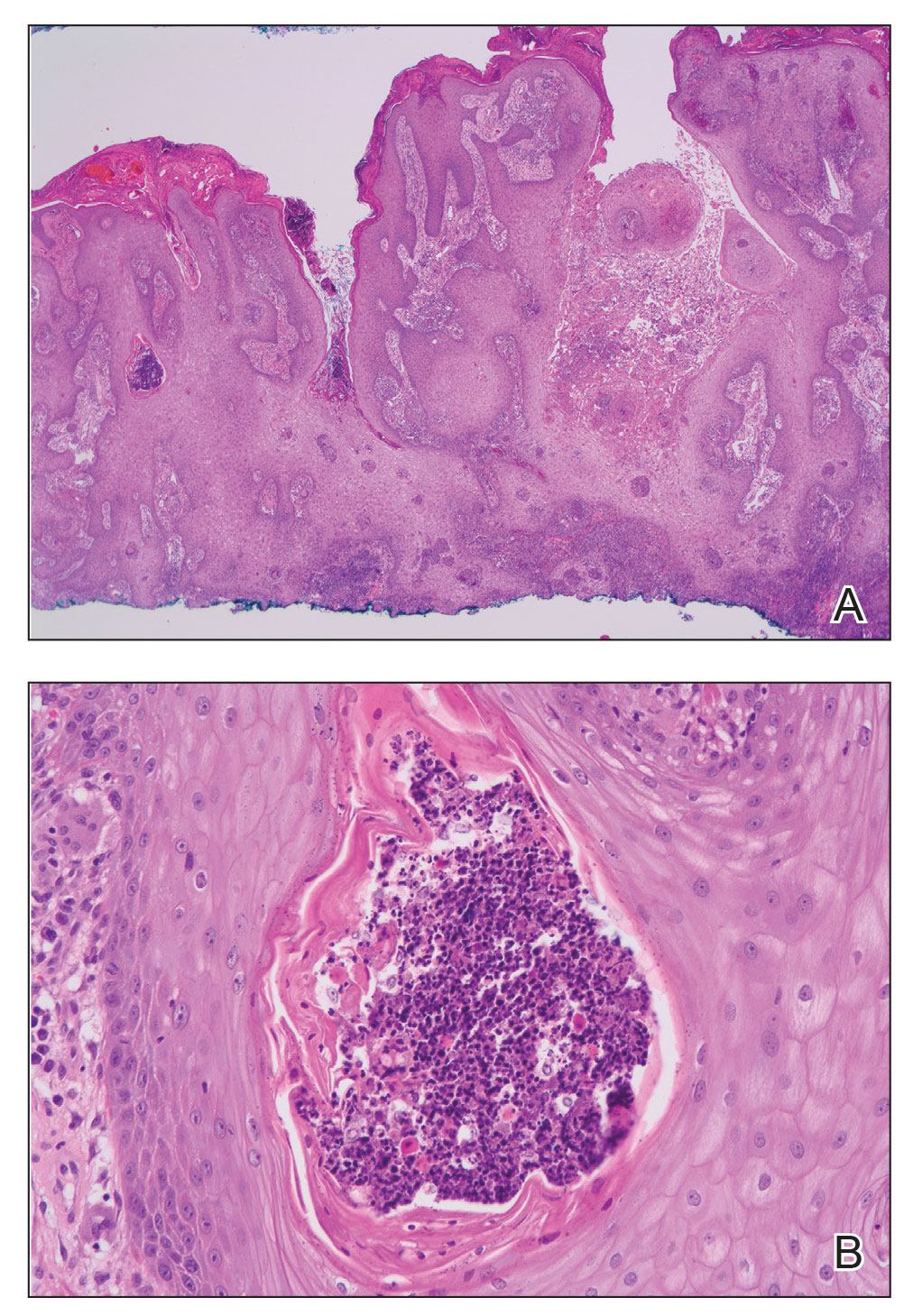

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

A 39-year-old man from Ohio presented with a tender, 10×6-cm, fungated, eroded plaque on the right medial upper arm that developed over the last 4 years. He initially noticed a firm lump under the right arm 4 years prior that was diagnosed as possible cellulitis at an outside clinic and treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The lesion then began to erode and became a chronic nonhealing wound. Approximately 1 year prior to the current presentation, the patient recalled unloading a truckload of soil around the same time the wound began to enlarge in diameter and depth. He denied any prior or current respiratory or systemic symptoms including fevers, chills, or weight loss.

How to overcome hesitancy for COVID-19 and other vaccines

The World Health Organization (WHO) named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to public health as of 2019.1 Although the COVID-19 vaccines manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, first authorized for use in November 2020 and fully approved in August 2021,2 are widely available in most countries, vaccination uptake is insufficient.3

As of June 2022, 78% of the US population had received at least 1 vaccine dose and 66.8% were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.4 High confidence in vaccines is associated with greater uptake; thus, engendering confidence in patients is a critical area of intervention for increasing uptake of COVID-19 and other vaccines.5 Despite the steady increase in vaccine acceptance observed following the release of the COVID-19 vaccine, acceptance remains suboptimal.2,6

Demographic characteristics associated with lower vaccine acceptance include younger age, female sex, lower education and/or income, and Black race or Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity (compared to white or Asian non-Hispanic).6,7 Moreover, patients who are skeptical of vaccine safety and efficacy are associated with lower intentions to vaccinate. In contrast, patients with a history of receiving influenza vaccinations and those with a greater concern about COVID-19 and their risk of infection have increased vaccine intentions.6

Numerous strategies exist to increase vaccine acceptance; however, there does not appear to be a single “best” method to overcome individual or parental vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19 or other vaccines.8,9 There are no large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating one strategy as more effective than another. In this review, we outline a variety of evidenced-based strategies to help patients overcome vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19 and other vaccines, with a focus on practical tips for primary care physicians (PCPs).

Which talking points are likely to resonate with your patients?

Intervention strategies promote vaccine acceptance by communicating personal benefit, collective benefit, or both to vaccine-hesitant patients. In a study sample of US undergraduate students, Kim and colleagues10 found that providing information about the benefits and risks of influenza vaccines resulted in significantly less vaccine intent compared to communicating information only on the benefits. Similarly, Shim and colleagues11 investigated how game theory (acting to maximize personal payoff regardless of payoff to others) and altruism affect influenza vaccination decisions. Through a survey-based study of 427 US university employees, researchers found altruistic motivation had a significant impact on the decision to vaccinate against influenza, resulting in a shift from self-interest to that of the good of the community.11

A German trial on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance by Sprengholz and colleagues12 found that communications about the benefits of vaccination, availability of financial compensation for vaccination, or a combination of both, did not increase a person’s willingness to get vaccinated. This trial, however, did not separate out individual vs collective benefit, and it was conducted prior to widespread COVID-19 vaccine availability.

In an online RCT conducted in early 2021, Freeman and colleagues13 randomized UK adults to 1 of 10 different “information conditions.” Participants read from 1 of 10 vaccine scripts that varied by the talking points they addressed. The topics that researchers drew from for these scripts included the personal or collective benefit from the COVID-19 vaccine, safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, and the seriousness of the pandemic. They found communications emphasizing personal benefit from vaccination and safety concerns were more effective in participants identified as being strongly hesitant (defined as those who said they would avoid getting the COVID-19 vaccine for as long as possible or who said they’d never get it). However, none of the information arms in this study decreased vaccine hesitancy among those who were doubtful of vaccination (defined as those who said they would delay vaccination or who didn’t know if they would get vaccinated).13

Continue to: When encountering patients who are strongly...

When encountering patients who are strongly hesitant to vaccination, an approach emphasizing concrete personal benefit may prove more effective than one stressing protection of others from illness. It is important to note, though, that findings from other countries may not be relevant to US patients due to differences in demographic factors, individual beliefs, and political climate.

It helps to explain herd immunity by providing concrete examples

Among the collective benefits of vaccination is the decreased risk of transmitting the disease to others (eg, family, friends, neighbors, colleagues), a quicker “return to normalcy,” and herd immunity.13 While individual health benefits may more strongly motivate people to get vaccinated than collective benefits, this may be due to a lack of understanding about herd immunity among the general public. The optimal method of communicating information on herd immunity is not known.14

Betsch and colleagues15 found that explaining herd immunity using interactive simulations increased vaccine intent, especially in countries that prioritize the self (rather than prioritizing the group over the individual). In addition to educating study participants about herd immunity, telling them how local vaccine coverage compared to the desired level of coverage helped to increase (influenza) vaccine intent among those who were least informed about herd immunity.16

Providing concrete examples of the collective benefits of vaccination (eg, protecting grandparents, children too young to be vaccinated, and those at increased risk for severe illness) or sharing stories about how other patients suffered from the disease in question may increase the likelihood of vaccination. One recent trial by Pfattheicher and colleagues17 found that empathy for those most vulnerable to COVID-19 and increased knowledge about herd immunity were 2 factors associated with greater vaccine intentions.

In this study, the authors induced empathy and increased COVID-19 vaccination intention by having participants read a short story about 2 close siblings who worked together in a nursing facility. In the story, participants learned that both siblings were given a diagnosis of COVID-19 at the same time but only 1 survived.17

Continue to: Try this 3-pronged approach

Try this 3-pronged approach. Consider explaining herd immunity to vaccine-hesitant patients, pairing this concept with information about local vaccine uptake, and appealing to the patient’s sense of empathy. You might share de-identified information on other patients in your practice or personal network who experienced severe illness, had long-term effects, or died from COVID-19 infection. Such concrete examples may help to increase motivation to vaccinate more than a general appeal to altruism.

Initiate the discussion by emphasizing that community immunity protects those who are vulnerable and lack immunity while providing specific empathetic examples (eg, newborns, cancer survivors) and asking patients to consider friends and family who might be at risk. Additionally, it is essential to explain that although community immunity can decrease the spread of infection, it can only be achieved when enough people are vaccinated.

Proceed with caution: Addressing conspiracy theories can backfire

Accurate information is critical to improving vaccine intentions; belief in conspiracy theories or misinformation related to COVID-19 is associated with reduced vaccine intentions and uptake.6 For example, a study by Loomba and colleagues18 showed that after exposure to misinformation, US and UK adults reported reduced intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19 once a vaccine became available.

Unfortunately, addressing myths about vaccines can sometimes backfire and unintentionally reinforce vaccine misperceptions.19,20 This is especially true for patients with the highest levels of concern or mistrust in vaccines. Nyhan and colleagues21,22 observed the backfire effect in 2 US studies looking at influenza and measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine misperceptions. Although corrective information significantly reduced belief in vaccine myths, they found individuals with the most concerns more strongly endorsed misperceptions when their beliefs were challenged.21,22

An Australian randomized study by Steffens and colleagues23 found repeating myths about childhood vaccines, followed by corrective text, to parents of children ages 0 to 5 years had no difference on parental intent to vaccinate their children compared to providing vaccine information as a statement or in a question/answer format. Furthermore, an RCT in Brazil by Carey and colleagues24 found that myth-correction messages about Zika virus failed to reduce misperceptions about the virus and actually reduced the belief in factual information about Zika—regardless of baseline beliefs in conspiracies. However, a similar experiment in the same study showed that myth-correction messages reduced false beliefs about yellow fever.

Continue to: The authors speculated...

The authors speculated that this may be because Zika is a relatively new virus when compared to yellow fever, and participants may have more pre-existing knowledge about yellow fever.24 These findings are important to keep in mind when addressing misinformation regarding COVID-19. When addressing myth perceptions with patients, consider pivoting the conversation from vaccine myths to the disease itself, focusing on the disease risk and severity of symptoms.19,20

Other studies have had positive results when addressing misinformation, including a digital RCT of older adults in the Netherlands by Yousuf and colleagues.25 In this study, participants were randomized to view 1 of 2 versions of an information video on vaccination featuring an informative discussion by celebrity scientists, government officials, and a cardiologist. Video 1 did not include debunking strategies, only information about vaccination; Video 2 provided the same information about vaccines but also described the myths surrounding vaccines and reiterated the truth to debunk the myths.

Findings demonstrated that a significantly higher number of participants in the Video 2 group overcame vaccination myths related to influenza and COVID-19.25 Notably, this study took place prior to the widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines and did not measure intent to vaccinate against COVID-19.

Taken together, strategies for correcting vaccine misinformation may vary by population as well as type of vaccine; however, placing emphasis on facts delivered by trusted sources appears to be beneficial. When addressing misinformation, PCPs should first focus on key details (not all supporting information) and clearly explain why the misinformation is false before pointing out the actual myth and providing an alternative explanation.20 When caring for patients who express strong concerns over the vaccine in question or have avid beliefs in certain myths or conspiracy theories, it’s best to pivot the conversation back to the disease rather than address the misinformation to avoid a potential backfire effect.

Utilize these effective communication techniques

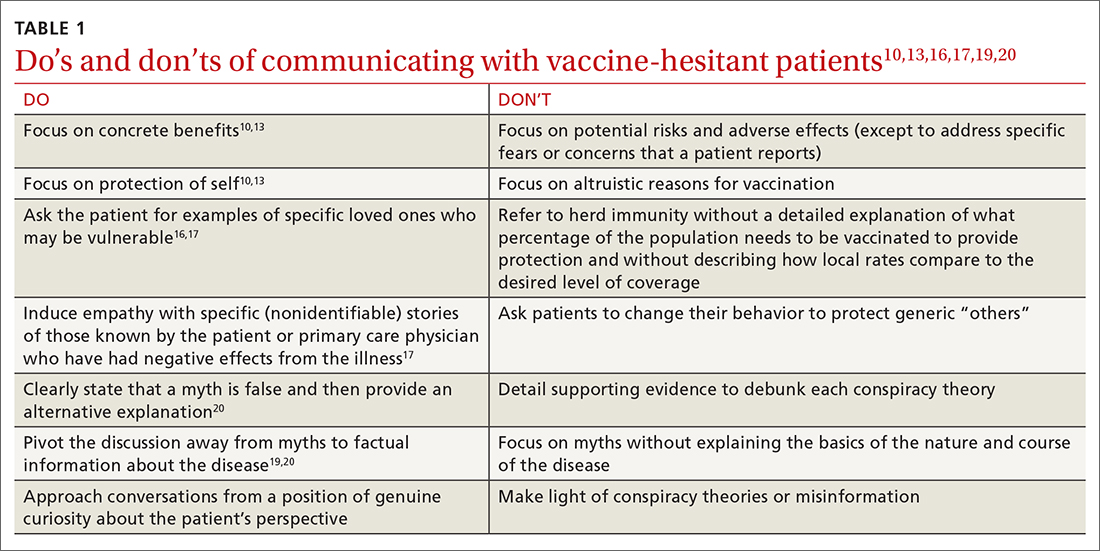

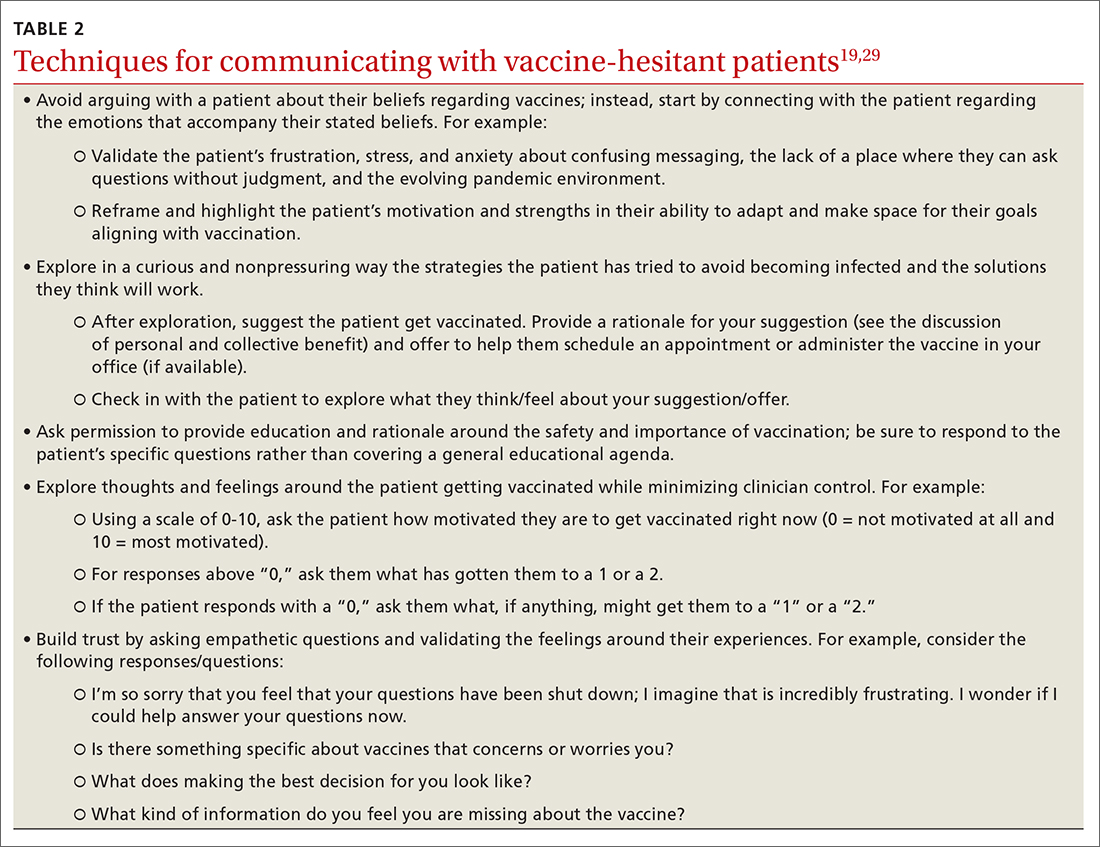

TABLE 110,13,16,17,19,20 summarizes the “do’s and don’ts” of communicating with vaccine-hesitant patients. PCPs should provide strong recommendations for vaccination, approaching it presumptively—ie, framing it as normative behavior.19,26 This approach is critical to building patient trust so that vaccine-hesitant patients feel the PCP is truly listening to them and addressing their concerns.27 Additionally, implementing motivational interviewing (MI) and self-determination theory (SDT)28 techniques when discussing vaccinations with patients can improve intentions and uptake.19,29TABLE 219,29 outlines specific techniques based on SDT and MI that PCPs may utilize to communicate with vaccine-hesitant individuals or parents.

Continue to: The takeaway

The takeaway

Strategies for increasing vaccine intentions include educating hesitant patients about the benefits and risks of vaccines, addressing misinformation, and explaining the personal and collective benefits of vaccination. These strategies appear to be more effective when delivered by a trusted source, such as a health care provider (HCP). Care should be taken when implementing vaccine-acceptance strategies to ensure that they are tailored to specific populations and vaccines.

At this stage in the COVID-19 pandemic, when several vaccines have been widely available for more than a year, we expect that the majority of patients desiring vaccination (ie, those with the greatest vaccine intent) have already received them. With the recent approval of COVID-19 vaccines for children younger than 5 years, we must now advocate for our patients to vaccinate not only themselves, but their children. Patients who remain unvaccinated may be hesitant or outright reject vaccination for a number of reasons, including fear or skepticism over the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, belief in conspiracy theories, belief that COVID-19 is not real or not severe, or mistrust of the government.6 Vaccine hesitation or rejection is also often political in nature.

Based on the studies included in this review, we have identified several strategies for reducing vaccine hesitancy, which can be used with vaccine-hesitant patients and parents. We suggest emphasizing the personal benefit of vaccination and focusing on specific disease risks. If time allows, you can also explain the collective benefit of vaccination through herd immunity, including the current levels of local vaccine uptake compared to the desired level for community immunity. Communicating the collective benefits of vaccination may be more effective when paired with a strategy intended to increase empathy and altruism, such as sharing actual stories about those who have suffered from a vaccine-preventable disease.

Addressing myths and misinformation related to COVID-19 and other vaccines, with emphasis placed on the correct information delivered by trusted sources may be beneficial for those who are uncertain but not strongly against vaccination. For those who remain staunchly hesitant against vaccination, we recommend focusing on the personal benefits of vaccination with a focus on delivering facts about the risk of the disease in question, rather than trying to refute misinformation.

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the United States is disturbingly low among health care workers, particularly nurses, technicians, and those in nonclinical roles, compared to physicians.6,30 Many of the strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy among the general population can also apply to health care personnel (eg, vaccine education, addressing misinformation, delivering information from a trusted source). Health care personnel may also be subject to vaccine mandates by their employers, which have demonstrated increases in vaccination rates for influenza.31 Given that COVID-19 vaccination recommendations made by HCPs are associated with greater vaccine intentions and uptake,6 reducing hesitancy among health care workers is a critical first step to achieving optimal implementation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole Mayo, PhD, 236 Pearl Street, Rochester, NY 14607; Nicole_Mayo@URMC.Rochester.edu

1. Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organization. Accessed June 17, 2022. www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

2. FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine. US Food and Drug Administration. August 23, 2021. Accessed June 17, 2022. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

3. Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:947-953. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8.

4. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Our world in data. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=USA

5. de Figueiredo A, Simas C, Karafillakis E, et al. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2020;396:898-908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0

6. Wang Y, Liu Y. Multilevel determinants of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid systematic review. Prev Med Rep. 2021;25:101673. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101673

7. Robinson E, Jones A, Lesser I, et al. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine. 2021;39:2024-2034. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.005

8. Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33:4191-4203. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041

9. Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, et al. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2013;31:4293-4304. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.013

10. Kim S, Pjesivac I, Jin Y. Effects of message framing on influenza vaccination: understanding the role of risk disclosure, perceived vaccine efficacy, and felt ambivalence. Health Commun. 2019;34:21-30. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1384353

11. Shim E, Chapman GB, Townsend JP, et al. The influence of altruism on influenza vaccination decisions. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9:2234-2243. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0115

12. Sprengholz P, Eitze S, Felgendreff L, et al. Money is not everything: experimental evidence that payments do not increase willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. J Med Ethics. 2021;47:547-548. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-107122

13. Freeman D, Loe BS, Yu LM, et al. Effects of different types of written vaccination information on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK (OCEANS-III): a single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e416-e427. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00096-7

14. Hakim H, Provencher T, Chambers CT, et al. Interventions to help people understand community immunity: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2019;37:235-247. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.11.016

15. Betsch C, Böhm R, Korn L, et al. On the benefits of explaining herd immunity in vaccine advocacy. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1:1-6. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0056

16. Logan J, Nederhoff D, Koch B, et al. ‘What have you HEARD about the HERD?’ Does education about local influenza vaccination coverage and herd immunity affect willingness to vaccinate? Vaccine. 2018;36:4118-4125. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.037

17. Pfattheicher S, Petersen MB, Böhm R. Information about herd immunity through vaccination and empathy promote COVID-19 vaccination intentions. Health Psychol. 2022;41:85-93. doi: 10.1037/hea0001096

18. Loomba S, de Figueiredo A, Piatek SJ, et al. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:337-348. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1

19. Limaye RJ, Opel DJ, Dempsey A, et al. Communicating with vaccine-hesitant parents: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:S24-S29. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.01.018

20. Omer SB, Amin AB, Limaye RJ. Communicating about vaccines in a fact-resistant world. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:929-930. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2219

21. Nyhan B, Reifler J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine. 2015;33:459-464. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.017

22. Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, et al. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e835-e842. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2365

23. Steffens MS, Dunn AG, Marques MD, et al. Addressing myths and vaccine hesitancy: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2021;148:e2020049304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-049304

24. Carey JM, Chi V, Flynn DJ, et al. The effects of corrective information about disease epidemics and outbreaks: evidence from Zika and yellow fever in Brazil. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaw7449. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7449

25. Yousuf H, van der Linden S, Bredius L, et al. A media intervention applying debunking versus non-debunking content to combat vaccine misinformation in elderly in the Netherlands: a digital randomised trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100881. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100881

26. Cambon L, Schwarzinger M, Alla F. Increasing acceptance of a vaccination program for coronavirus disease 2019 in France: a challenge for one of the world’s most vaccine-hesitant countries. Vaccine. 2022;40:178-182. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.023

27. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-154

28. Martela F, Hankonen N, Ryan RM, et al. Motivating voluntary compliance to behavioural restrictions: self-determination theory–based checklist of principles for COVID-19 and other emergency communications. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2021:305-347. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2020.1857082

29. Boness CL, Nelson M, Douaihy AB. Motivational interviewing strategies for addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35:420-426. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2022.02.210327

30. Salomoni MG, Di Valerio Z, Gabrielli E, et al. Hesitant or not hesitant? A systematic review on global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in different populations. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:873. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080873

31. Pitts SI, Maruthur NM, Millar KR, et al. A systematic review of mandatory influenza vaccination in healthcare personnel. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:330-340. doi:

The World Health Organization (WHO) named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to public health as of 2019.1 Although the COVID-19 vaccines manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, first authorized for use in November 2020 and fully approved in August 2021,2 are widely available in most countries, vaccination uptake is insufficient.3

As of June 2022, 78% of the US population had received at least 1 vaccine dose and 66.8% were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.4 High confidence in vaccines is associated with greater uptake; thus, engendering confidence in patients is a critical area of intervention for increasing uptake of COVID-19 and other vaccines.5 Despite the steady increase in vaccine acceptance observed following the release of the COVID-19 vaccine, acceptance remains suboptimal.2,6

Demographic characteristics associated with lower vaccine acceptance include younger age, female sex, lower education and/or income, and Black race or Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity (compared to white or Asian non-Hispanic).6,7 Moreover, patients who are skeptical of vaccine safety and efficacy are associated with lower intentions to vaccinate. In contrast, patients with a history of receiving influenza vaccinations and those with a greater concern about COVID-19 and their risk of infection have increased vaccine intentions.6

Numerous strategies exist to increase vaccine acceptance; however, there does not appear to be a single “best” method to overcome individual or parental vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19 or other vaccines.8,9 There are no large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating one strategy as more effective than another. In this review, we outline a variety of evidenced-based strategies to help patients overcome vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19 and other vaccines, with a focus on practical tips for primary care physicians (PCPs).

Which talking points are likely to resonate with your patients?

Intervention strategies promote vaccine acceptance by communicating personal benefit, collective benefit, or both to vaccine-hesitant patients. In a study sample of US undergraduate students, Kim and colleagues10 found that providing information about the benefits and risks of influenza vaccines resulted in significantly less vaccine intent compared to communicating information only on the benefits. Similarly, Shim and colleagues11 investigated how game theory (acting to maximize personal payoff regardless of payoff to others) and altruism affect influenza vaccination decisions. Through a survey-based study of 427 US university employees, researchers found altruistic motivation had a significant impact on the decision to vaccinate against influenza, resulting in a shift from self-interest to that of the good of the community.11

A German trial on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance by Sprengholz and colleagues12 found that communications about the benefits of vaccination, availability of financial compensation for vaccination, or a combination of both, did not increase a person’s willingness to get vaccinated. This trial, however, did not separate out individual vs collective benefit, and it was conducted prior to widespread COVID-19 vaccine availability.

In an online RCT conducted in early 2021, Freeman and colleagues13 randomized UK adults to 1 of 10 different “information conditions.” Participants read from 1 of 10 vaccine scripts that varied by the talking points they addressed. The topics that researchers drew from for these scripts included the personal or collective benefit from the COVID-19 vaccine, safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, and the seriousness of the pandemic. They found communications emphasizing personal benefit from vaccination and safety concerns were more effective in participants identified as being strongly hesitant (defined as those who said they would avoid getting the COVID-19 vaccine for as long as possible or who said they’d never get it). However, none of the information arms in this study decreased vaccine hesitancy among those who were doubtful of vaccination (defined as those who said they would delay vaccination or who didn’t know if they would get vaccinated).13

Continue to: When encountering patients who are strongly...

When encountering patients who are strongly hesitant to vaccination, an approach emphasizing concrete personal benefit may prove more effective than one stressing protection of others from illness. It is important to note, though, that findings from other countries may not be relevant to US patients due to differences in demographic factors, individual beliefs, and political climate.

It helps to explain herd immunity by providing concrete examples

Among the collective benefits of vaccination is the decreased risk of transmitting the disease to others (eg, family, friends, neighbors, colleagues), a quicker “return to normalcy,” and herd immunity.13 While individual health benefits may more strongly motivate people to get vaccinated than collective benefits, this may be due to a lack of understanding about herd immunity among the general public. The optimal method of communicating information on herd immunity is not known.14

Betsch and colleagues15 found that explaining herd immunity using interactive simulations increased vaccine intent, especially in countries that prioritize the self (rather than prioritizing the group over the individual). In addition to educating study participants about herd immunity, telling them how local vaccine coverage compared to the desired level of coverage helped to increase (influenza) vaccine intent among those who were least informed about herd immunity.16

Providing concrete examples of the collective benefits of vaccination (eg, protecting grandparents, children too young to be vaccinated, and those at increased risk for severe illness) or sharing stories about how other patients suffered from the disease in question may increase the likelihood of vaccination. One recent trial by Pfattheicher and colleagues17 found that empathy for those most vulnerable to COVID-19 and increased knowledge about herd immunity were 2 factors associated with greater vaccine intentions.

In this study, the authors induced empathy and increased COVID-19 vaccination intention by having participants read a short story about 2 close siblings who worked together in a nursing facility. In the story, participants learned that both siblings were given a diagnosis of COVID-19 at the same time but only 1 survived.17

Continue to: Try this 3-pronged approach

Try this 3-pronged approach. Consider explaining herd immunity to vaccine-hesitant patients, pairing this concept with information about local vaccine uptake, and appealing to the patient’s sense of empathy. You might share de-identified information on other patients in your practice or personal network who experienced severe illness, had long-term effects, or died from COVID-19 infection. Such concrete examples may help to increase motivation to vaccinate more than a general appeal to altruism.

Initiate the discussion by emphasizing that community immunity protects those who are vulnerable and lack immunity while providing specific empathetic examples (eg, newborns, cancer survivors) and asking patients to consider friends and family who might be at risk. Additionally, it is essential to explain that although community immunity can decrease the spread of infection, it can only be achieved when enough people are vaccinated.

Proceed with caution: Addressing conspiracy theories can backfire

Accurate information is critical to improving vaccine intentions; belief in conspiracy theories or misinformation related to COVID-19 is associated with reduced vaccine intentions and uptake.6 For example, a study by Loomba and colleagues18 showed that after exposure to misinformation, US and UK adults reported reduced intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19 once a vaccine became available.

Unfortunately, addressing myths about vaccines can sometimes backfire and unintentionally reinforce vaccine misperceptions.19,20 This is especially true for patients with the highest levels of concern or mistrust in vaccines. Nyhan and colleagues21,22 observed the backfire effect in 2 US studies looking at influenza and measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine misperceptions. Although corrective information significantly reduced belief in vaccine myths, they found individuals with the most concerns more strongly endorsed misperceptions when their beliefs were challenged.21,22

An Australian randomized study by Steffens and colleagues23 found repeating myths about childhood vaccines, followed by corrective text, to parents of children ages 0 to 5 years had no difference on parental intent to vaccinate their children compared to providing vaccine information as a statement or in a question/answer format. Furthermore, an RCT in Brazil by Carey and colleagues24 found that myth-correction messages about Zika virus failed to reduce misperceptions about the virus and actually reduced the belief in factual information about Zika—regardless of baseline beliefs in conspiracies. However, a similar experiment in the same study showed that myth-correction messages reduced false beliefs about yellow fever.

Continue to: The authors speculated...

The authors speculated that this may be because Zika is a relatively new virus when compared to yellow fever, and participants may have more pre-existing knowledge about yellow fever.24 These findings are important to keep in mind when addressing misinformation regarding COVID-19. When addressing myth perceptions with patients, consider pivoting the conversation from vaccine myths to the disease itself, focusing on the disease risk and severity of symptoms.19,20

Other studies have had positive results when addressing misinformation, including a digital RCT of older adults in the Netherlands by Yousuf and colleagues.25 In this study, participants were randomized to view 1 of 2 versions of an information video on vaccination featuring an informative discussion by celebrity scientists, government officials, and a cardiologist. Video 1 did not include debunking strategies, only information about vaccination; Video 2 provided the same information about vaccines but also described the myths surrounding vaccines and reiterated the truth to debunk the myths.

Findings demonstrated that a significantly higher number of participants in the Video 2 group overcame vaccination myths related to influenza and COVID-19.25 Notably, this study took place prior to the widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines and did not measure intent to vaccinate against COVID-19.

Taken together, strategies for correcting vaccine misinformation may vary by population as well as type of vaccine; however, placing emphasis on facts delivered by trusted sources appears to be beneficial. When addressing misinformation, PCPs should first focus on key details (not all supporting information) and clearly explain why the misinformation is false before pointing out the actual myth and providing an alternative explanation.20 When caring for patients who express strong concerns over the vaccine in question or have avid beliefs in certain myths or conspiracy theories, it’s best to pivot the conversation back to the disease rather than address the misinformation to avoid a potential backfire effect.

Utilize these effective communication techniques

TABLE 110,13,16,17,19,20 summarizes the “do’s and don’ts” of communicating with vaccine-hesitant patients. PCPs should provide strong recommendations for vaccination, approaching it presumptively—ie, framing it as normative behavior.19,26 This approach is critical to building patient trust so that vaccine-hesitant patients feel the PCP is truly listening to them and addressing their concerns.27 Additionally, implementing motivational interviewing (MI) and self-determination theory (SDT)28 techniques when discussing vaccinations with patients can improve intentions and uptake.19,29TABLE 219,29 outlines specific techniques based on SDT and MI that PCPs may utilize to communicate with vaccine-hesitant individuals or parents.

Continue to: The takeaway

The takeaway

Strategies for increasing vaccine intentions include educating hesitant patients about the benefits and risks of vaccines, addressing misinformation, and explaining the personal and collective benefits of vaccination. These strategies appear to be more effective when delivered by a trusted source, such as a health care provider (HCP). Care should be taken when implementing vaccine-acceptance strategies to ensure that they are tailored to specific populations and vaccines.

At this stage in the COVID-19 pandemic, when several vaccines have been widely available for more than a year, we expect that the majority of patients desiring vaccination (ie, those with the greatest vaccine intent) have already received them. With the recent approval of COVID-19 vaccines for children younger than 5 years, we must now advocate for our patients to vaccinate not only themselves, but their children. Patients who remain unvaccinated may be hesitant or outright reject vaccination for a number of reasons, including fear or skepticism over the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, belief in conspiracy theories, belief that COVID-19 is not real or not severe, or mistrust of the government.6 Vaccine hesitation or rejection is also often political in nature.

Based on the studies included in this review, we have identified several strategies for reducing vaccine hesitancy, which can be used with vaccine-hesitant patients and parents. We suggest emphasizing the personal benefit of vaccination and focusing on specific disease risks. If time allows, you can also explain the collective benefit of vaccination through herd immunity, including the current levels of local vaccine uptake compared to the desired level for community immunity. Communicating the collective benefits of vaccination may be more effective when paired with a strategy intended to increase empathy and altruism, such as sharing actual stories about those who have suffered from a vaccine-preventable disease.

Addressing myths and misinformation related to COVID-19 and other vaccines, with emphasis placed on the correct information delivered by trusted sources may be beneficial for those who are uncertain but not strongly against vaccination. For those who remain staunchly hesitant against vaccination, we recommend focusing on the personal benefits of vaccination with a focus on delivering facts about the risk of the disease in question, rather than trying to refute misinformation.

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the United States is disturbingly low among health care workers, particularly nurses, technicians, and those in nonclinical roles, compared to physicians.6,30 Many of the strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy among the general population can also apply to health care personnel (eg, vaccine education, addressing misinformation, delivering information from a trusted source). Health care personnel may also be subject to vaccine mandates by their employers, which have demonstrated increases in vaccination rates for influenza.31 Given that COVID-19 vaccination recommendations made by HCPs are associated with greater vaccine intentions and uptake,6 reducing hesitancy among health care workers is a critical first step to achieving optimal implementation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole Mayo, PhD, 236 Pearl Street, Rochester, NY 14607; Nicole_Mayo@URMC.Rochester.edu

The World Health Organization (WHO) named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to public health as of 2019.1 Although the COVID-19 vaccines manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, first authorized for use in November 2020 and fully approved in August 2021,2 are widely available in most countries, vaccination uptake is insufficient.3

As of June 2022, 78% of the US population had received at least 1 vaccine dose and 66.8% were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.4 High confidence in vaccines is associated with greater uptake; thus, engendering confidence in patients is a critical area of intervention for increasing uptake of COVID-19 and other vaccines.5 Despite the steady increase in vaccine acceptance observed following the release of the COVID-19 vaccine, acceptance remains suboptimal.2,6

Demographic characteristics associated with lower vaccine acceptance include younger age, female sex, lower education and/or income, and Black race or Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity (compared to white or Asian non-Hispanic).6,7 Moreover, patients who are skeptical of vaccine safety and efficacy are associated with lower intentions to vaccinate. In contrast, patients with a history of receiving influenza vaccinations and those with a greater concern about COVID-19 and their risk of infection have increased vaccine intentions.6

Numerous strategies exist to increase vaccine acceptance; however, there does not appear to be a single “best” method to overcome individual or parental vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19 or other vaccines.8,9 There are no large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating one strategy as more effective than another. In this review, we outline a variety of evidenced-based strategies to help patients overcome vaccine hesitancy for COVID-19 and other vaccines, with a focus on practical tips for primary care physicians (PCPs).

Which talking points are likely to resonate with your patients?

Intervention strategies promote vaccine acceptance by communicating personal benefit, collective benefit, or both to vaccine-hesitant patients. In a study sample of US undergraduate students, Kim and colleagues10 found that providing information about the benefits and risks of influenza vaccines resulted in significantly less vaccine intent compared to communicating information only on the benefits. Similarly, Shim and colleagues11 investigated how game theory (acting to maximize personal payoff regardless of payoff to others) and altruism affect influenza vaccination decisions. Through a survey-based study of 427 US university employees, researchers found altruistic motivation had a significant impact on the decision to vaccinate against influenza, resulting in a shift from self-interest to that of the good of the community.11

A German trial on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance by Sprengholz and colleagues12 found that communications about the benefits of vaccination, availability of financial compensation for vaccination, or a combination of both, did not increase a person’s willingness to get vaccinated. This trial, however, did not separate out individual vs collective benefit, and it was conducted prior to widespread COVID-19 vaccine availability.

In an online RCT conducted in early 2021, Freeman and colleagues13 randomized UK adults to 1 of 10 different “information conditions.” Participants read from 1 of 10 vaccine scripts that varied by the talking points they addressed. The topics that researchers drew from for these scripts included the personal or collective benefit from the COVID-19 vaccine, safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, and the seriousness of the pandemic. They found communications emphasizing personal benefit from vaccination and safety concerns were more effective in participants identified as being strongly hesitant (defined as those who said they would avoid getting the COVID-19 vaccine for as long as possible or who said they’d never get it). However, none of the information arms in this study decreased vaccine hesitancy among those who were doubtful of vaccination (defined as those who said they would delay vaccination or who didn’t know if they would get vaccinated).13

Continue to: When encountering patients who are strongly...

When encountering patients who are strongly hesitant to vaccination, an approach emphasizing concrete personal benefit may prove more effective than one stressing protection of others from illness. It is important to note, though, that findings from other countries may not be relevant to US patients due to differences in demographic factors, individual beliefs, and political climate.

It helps to explain herd immunity by providing concrete examples

Among the collective benefits of vaccination is the decreased risk of transmitting the disease to others (eg, family, friends, neighbors, colleagues), a quicker “return to normalcy,” and herd immunity.13 While individual health benefits may more strongly motivate people to get vaccinated than collective benefits, this may be due to a lack of understanding about herd immunity among the general public. The optimal method of communicating information on herd immunity is not known.14

Betsch and colleagues15 found that explaining herd immunity using interactive simulations increased vaccine intent, especially in countries that prioritize the self (rather than prioritizing the group over the individual). In addition to educating study participants about herd immunity, telling them how local vaccine coverage compared to the desired level of coverage helped to increase (influenza) vaccine intent among those who were least informed about herd immunity.16

Providing concrete examples of the collective benefits of vaccination (eg, protecting grandparents, children too young to be vaccinated, and those at increased risk for severe illness) or sharing stories about how other patients suffered from the disease in question may increase the likelihood of vaccination. One recent trial by Pfattheicher and colleagues17 found that empathy for those most vulnerable to COVID-19 and increased knowledge about herd immunity were 2 factors associated with greater vaccine intentions.

In this study, the authors induced empathy and increased COVID-19 vaccination intention by having participants read a short story about 2 close siblings who worked together in a nursing facility. In the story, participants learned that both siblings were given a diagnosis of COVID-19 at the same time but only 1 survived.17

Continue to: Try this 3-pronged approach

Try this 3-pronged approach. Consider explaining herd immunity to vaccine-hesitant patients, pairing this concept with information about local vaccine uptake, and appealing to the patient’s sense of empathy. You might share de-identified information on other patients in your practice or personal network who experienced severe illness, had long-term effects, or died from COVID-19 infection. Such concrete examples may help to increase motivation to vaccinate more than a general appeal to altruism.

Initiate the discussion by emphasizing that community immunity protects those who are vulnerable and lack immunity while providing specific empathetic examples (eg, newborns, cancer survivors) and asking patients to consider friends and family who might be at risk. Additionally, it is essential to explain that although community immunity can decrease the spread of infection, it can only be achieved when enough people are vaccinated.

Proceed with caution: Addressing conspiracy theories can backfire

Accurate information is critical to improving vaccine intentions; belief in conspiracy theories or misinformation related to COVID-19 is associated with reduced vaccine intentions and uptake.6 For example, a study by Loomba and colleagues18 showed that after exposure to misinformation, US and UK adults reported reduced intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19 once a vaccine became available.

Unfortunately, addressing myths about vaccines can sometimes backfire and unintentionally reinforce vaccine misperceptions.19,20 This is especially true for patients with the highest levels of concern or mistrust in vaccines. Nyhan and colleagues21,22 observed the backfire effect in 2 US studies looking at influenza and measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine misperceptions. Although corrective information significantly reduced belief in vaccine myths, they found individuals with the most concerns more strongly endorsed misperceptions when their beliefs were challenged.21,22

An Australian randomized study by Steffens and colleagues23 found repeating myths about childhood vaccines, followed by corrective text, to parents of children ages 0 to 5 years had no difference on parental intent to vaccinate their children compared to providing vaccine information as a statement or in a question/answer format. Furthermore, an RCT in Brazil by Carey and colleagues24 found that myth-correction messages about Zika virus failed to reduce misperceptions about the virus and actually reduced the belief in factual information about Zika—regardless of baseline beliefs in conspiracies. However, a similar experiment in the same study showed that myth-correction messages reduced false beliefs about yellow fever.

Continue to: The authors speculated...

The authors speculated that this may be because Zika is a relatively new virus when compared to yellow fever, and participants may have more pre-existing knowledge about yellow fever.24 These findings are important to keep in mind when addressing misinformation regarding COVID-19. When addressing myth perceptions with patients, consider pivoting the conversation from vaccine myths to the disease itself, focusing on the disease risk and severity of symptoms.19,20

Other studies have had positive results when addressing misinformation, including a digital RCT of older adults in the Netherlands by Yousuf and colleagues.25 In this study, participants were randomized to view 1 of 2 versions of an information video on vaccination featuring an informative discussion by celebrity scientists, government officials, and a cardiologist. Video 1 did not include debunking strategies, only information about vaccination; Video 2 provided the same information about vaccines but also described the myths surrounding vaccines and reiterated the truth to debunk the myths.

Findings demonstrated that a significantly higher number of participants in the Video 2 group overcame vaccination myths related to influenza and COVID-19.25 Notably, this study took place prior to the widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines and did not measure intent to vaccinate against COVID-19.

Taken together, strategies for correcting vaccine misinformation may vary by population as well as type of vaccine; however, placing emphasis on facts delivered by trusted sources appears to be beneficial. When addressing misinformation, PCPs should first focus on key details (not all supporting information) and clearly explain why the misinformation is false before pointing out the actual myth and providing an alternative explanation.20 When caring for patients who express strong concerns over the vaccine in question or have avid beliefs in certain myths or conspiracy theories, it’s best to pivot the conversation back to the disease rather than address the misinformation to avoid a potential backfire effect.

Utilize these effective communication techniques

TABLE 110,13,16,17,19,20 summarizes the “do’s and don’ts” of communicating with vaccine-hesitant patients. PCPs should provide strong recommendations for vaccination, approaching it presumptively—ie, framing it as normative behavior.19,26 This approach is critical to building patient trust so that vaccine-hesitant patients feel the PCP is truly listening to them and addressing their concerns.27 Additionally, implementing motivational interviewing (MI) and self-determination theory (SDT)28 techniques when discussing vaccinations with patients can improve intentions and uptake.19,29TABLE 219,29 outlines specific techniques based on SDT and MI that PCPs may utilize to communicate with vaccine-hesitant individuals or parents.

Continue to: The takeaway

The takeaway

Strategies for increasing vaccine intentions include educating hesitant patients about the benefits and risks of vaccines, addressing misinformation, and explaining the personal and collective benefits of vaccination. These strategies appear to be more effective when delivered by a trusted source, such as a health care provider (HCP). Care should be taken when implementing vaccine-acceptance strategies to ensure that they are tailored to specific populations and vaccines.

At this stage in the COVID-19 pandemic, when several vaccines have been widely available for more than a year, we expect that the majority of patients desiring vaccination (ie, those with the greatest vaccine intent) have already received them. With the recent approval of COVID-19 vaccines for children younger than 5 years, we must now advocate for our patients to vaccinate not only themselves, but their children. Patients who remain unvaccinated may be hesitant or outright reject vaccination for a number of reasons, including fear or skepticism over the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, belief in conspiracy theories, belief that COVID-19 is not real or not severe, or mistrust of the government.6 Vaccine hesitation or rejection is also often political in nature.

Based on the studies included in this review, we have identified several strategies for reducing vaccine hesitancy, which can be used with vaccine-hesitant patients and parents. We suggest emphasizing the personal benefit of vaccination and focusing on specific disease risks. If time allows, you can also explain the collective benefit of vaccination through herd immunity, including the current levels of local vaccine uptake compared to the desired level for community immunity. Communicating the collective benefits of vaccination may be more effective when paired with a strategy intended to increase empathy and altruism, such as sharing actual stories about those who have suffered from a vaccine-preventable disease.

Addressing myths and misinformation related to COVID-19 and other vaccines, with emphasis placed on the correct information delivered by trusted sources may be beneficial for those who are uncertain but not strongly against vaccination. For those who remain staunchly hesitant against vaccination, we recommend focusing on the personal benefits of vaccination with a focus on delivering facts about the risk of the disease in question, rather than trying to refute misinformation.

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the United States is disturbingly low among health care workers, particularly nurses, technicians, and those in nonclinical roles, compared to physicians.6,30 Many of the strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy among the general population can also apply to health care personnel (eg, vaccine education, addressing misinformation, delivering information from a trusted source). Health care personnel may also be subject to vaccine mandates by their employers, which have demonstrated increases in vaccination rates for influenza.31 Given that COVID-19 vaccination recommendations made by HCPs are associated with greater vaccine intentions and uptake,6 reducing hesitancy among health care workers is a critical first step to achieving optimal implementation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole Mayo, PhD, 236 Pearl Street, Rochester, NY 14607; Nicole_Mayo@URMC.Rochester.edu

1. Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organization. Accessed June 17, 2022. www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

2. FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine. US Food and Drug Administration. August 23, 2021. Accessed June 17, 2022. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

3. Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:947-953. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8.

4. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Our world in data. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=USA

5. de Figueiredo A, Simas C, Karafillakis E, et al. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2020;396:898-908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0

6. Wang Y, Liu Y. Multilevel determinants of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid systematic review. Prev Med Rep. 2021;25:101673. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101673

7. Robinson E, Jones A, Lesser I, et al. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine. 2021;39:2024-2034. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.005

8. Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33:4191-4203. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041

9. Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, et al. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2013;31:4293-4304. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.013

10. Kim S, Pjesivac I, Jin Y. Effects of message framing on influenza vaccination: understanding the role of risk disclosure, perceived vaccine efficacy, and felt ambivalence. Health Commun. 2019;34:21-30. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1384353

11. Shim E, Chapman GB, Townsend JP, et al. The influence of altruism on influenza vaccination decisions. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9:2234-2243. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0115

12. Sprengholz P, Eitze S, Felgendreff L, et al. Money is not everything: experimental evidence that payments do not increase willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. J Med Ethics. 2021;47:547-548. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-107122

13. Freeman D, Loe BS, Yu LM, et al. Effects of different types of written vaccination information on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK (OCEANS-III): a single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e416-e427. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00096-7

14. Hakim H, Provencher T, Chambers CT, et al. Interventions to help people understand community immunity: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2019;37:235-247. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.11.016

15. Betsch C, Böhm R, Korn L, et al. On the benefits of explaining herd immunity in vaccine advocacy. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1:1-6. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0056

16. Logan J, Nederhoff D, Koch B, et al. ‘What have you HEARD about the HERD?’ Does education about local influenza vaccination coverage and herd immunity affect willingness to vaccinate? Vaccine. 2018;36:4118-4125. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.037

17. Pfattheicher S, Petersen MB, Böhm R. Information about herd immunity through vaccination and empathy promote COVID-19 vaccination intentions. Health Psychol. 2022;41:85-93. doi: 10.1037/hea0001096

18. Loomba S, de Figueiredo A, Piatek SJ, et al. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:337-348. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1

19. Limaye RJ, Opel DJ, Dempsey A, et al. Communicating with vaccine-hesitant parents: a narrative review. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:S24-S29. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.01.018

20. Omer SB, Amin AB, Limaye RJ. Communicating about vaccines in a fact-resistant world. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:929-930. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2219

21. Nyhan B, Reifler J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine. 2015;33:459-464. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.017

22. Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, et al. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e835-e842. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2365

23. Steffens MS, Dunn AG, Marques MD, et al. Addressing myths and vaccine hesitancy: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2021;148:e2020049304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-049304

24. Carey JM, Chi V, Flynn DJ, et al. The effects of corrective information about disease epidemics and outbreaks: evidence from Zika and yellow fever in Brazil. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaw7449. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7449

25. Yousuf H, van der Linden S, Bredius L, et al. A media intervention applying debunking versus non-debunking content to combat vaccine misinformation in elderly in the Netherlands: a digital randomised trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100881. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100881

26. Cambon L, Schwarzinger M, Alla F. Increasing acceptance of a vaccination program for coronavirus disease 2019 in France: a challenge for one of the world’s most vaccine-hesitant countries. Vaccine. 2022;40:178-182. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.023

27. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-154