User login

Measles outbreaks: Protecting your patients during international travel

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

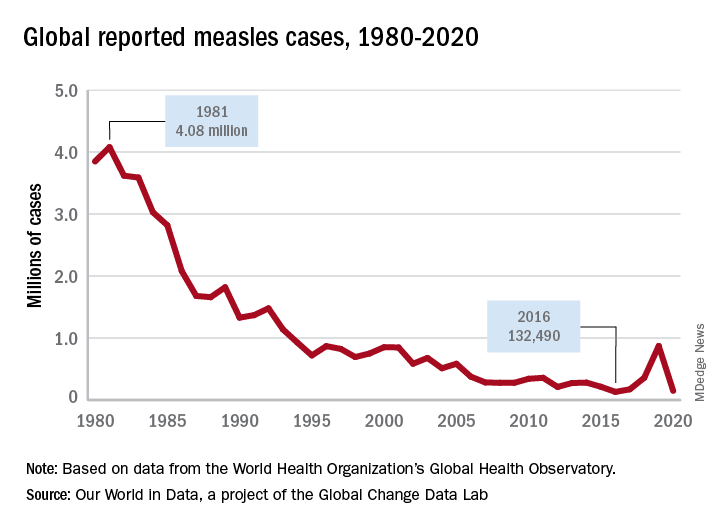

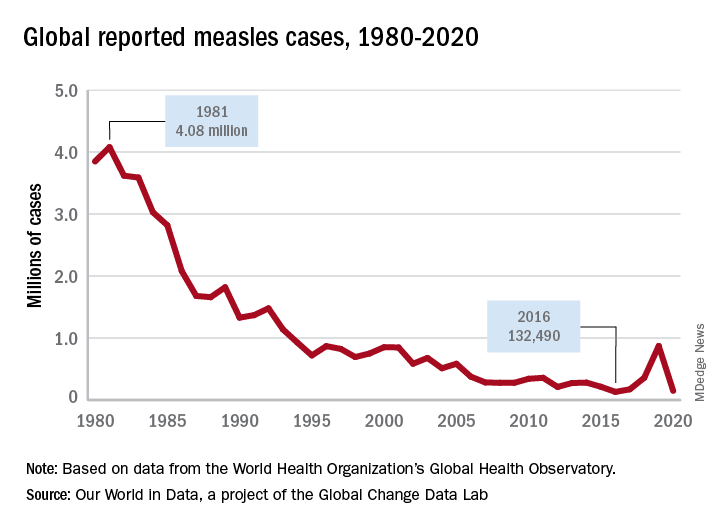

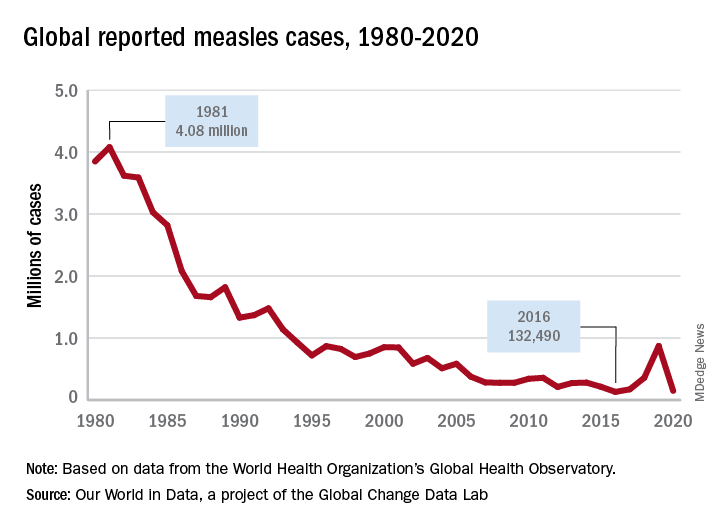

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

Severe infections often accompany severe psoriasis

of nearly 95,000 patients.

Although previous studies have shown a higher risk for comorbid conditions in people with psoriasis, compared with those without psoriasis, data on the occurrence of severe and rare infections in patients with psoriasis are limited, wrote Nikolai Loft, MD, of the department of dermatology and allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital, Gentofte, and colleagues.

Psoriasis patients are often treated with immunosuppressive therapies that may promote or aggravate infections; therefore, a better understanding of psoriasis and risk of infections is needed, they said. In a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology, Dr. Loft and his coinvestigators reviewed data on adults aged 18 years and older from the Danish National Patient Register between Jan. 1, 1997 and Dec. 31, 2018. The study population included 94,450 adults with psoriasis and 566,700 matched controls. Patients with any type of psoriasis and any degree of severity were included.

The primary outcome was the occurrence of severe infections, defined as those requiring assessment at a hospital, and rare infections, defined as HIV, TB, HBV, and HCV. The median age of the participants was 52.3 years, and slightly more than half were women.

Overall, the incidence rate of severe and rare infections among patients with any type of psoriasis was 3,104.9 per 100,000 person-years, compared with 2,381.1 for controls, with a hazard ratio, adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, alcohol-related conditions, and Charlson comorbidity index (aHR) of 1.29.

For any infections resulting in hospitalization, the incidence rate was 2,005.1 vs. 1,531.8 per 100,000 person-years for patients with any type of psoriasis and controls, respectively.

The results were similar when severe infections and rare infections were analyzed separately. The incidence rate of severe infections was 3,080.6 and 2,364.4 per 100,000 person-years for patients with any psoriasis, compared with controls; the incidence rate for rare infections was 42.9 and 31.8 for all psoriasis patients and controls, respectively.

When the data were examined by psoriasis severity, the incidence rate of severe and rare infections among patients with severe psoriasis was 3,847.7 per 100,000 person-years, compared with 2,351.9 per 100,000 person years among controls (aHR, 1.58) and also higher than in patients with mild psoriasis. The incidence rate of severe and rare infections in patients with mild psoriasis (2,979.1 per 100,000 person-years) also was higher than in controls (aHR, 1.26).

Factors that might explain the increased infection risk with severe psoriasis include the altered immune environment in these patients, the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. Also, “patients with severe psoriasis are defined by their eligibility for systemics, either conventional or biologic,” and their increased infection risk may stem from these treatments, rather than disease severity itself, they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on such confounders as weight, body mass index, and smoking status, they added. Other limitations included potential surveillance bias because of greater TB screening, and the use of prescriptions, rather than the Psoriasis Area Severity Index, to define severity. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and suggest that patients with any type of psoriasis have higher rates of any infection, severe or rare, than the general population, the researchers concluded.

Data show need for clinician vigilance

Based on the 2020 Census data, an estimated 7.55 million adults in the United States have psoriasis, David Robles, MD, said in an interview. “Patients with psoriasis have a high risk for multiple comorbid conditions including metabolic syndrome, which is characterized by obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,” said Dr. Robles, a dermatologist in private practice in Pomona, Calif., who was not involved in the study. “Although these complications were previously attributed to diet and obesity, it has become clear that the proinflammatory cytokines associated with psoriasis may be playing an important role underlying the pathologic basis of these other comorbidities.”

There is an emerging body of literature “indicating that psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of infections,” he added. Research in this area is particularly important because of the increased risk of infections associated with many biologic and immune-modulating treatments for psoriasis, Dr. Robles noted.

The study findings “indicate that, as the severity of psoriasis increases, so does the risk of severe and rare infections,” he said. “This makes it imperative for clinicians to be alert to the possibility of severe or rare infections in patients with psoriasis, especially those with severe psoriasis, so that early intervention can be initiated.”

As for additional research, “as an immunologist and dermatologist, I cannot help but think about the possible role the genetic and cytokine pathways involved in psoriasis may be playing in modulating the immune system and/or microbiome, and whether this contributes to a higher risk of infections,” Dr. Robles said. “Just as it was discovered that patients with atopic dermatitis have decreased levels of antimicrobial peptides in their skin, making them susceptible to recurrent bacterial skin infections, we may find that the genetic and immunological changes associated with psoriasis may independently contribute to infection susceptibility,” he noted. “More basic immunology and virology research may one day shed light on this observation.”

The study was supported by Novartis. Lead author Dr. Loft disclosed serving as a speaker for Eli Lilly and Janssen Cilag, other authors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Novartis, and two authors are Novartis employees. Dr. Robles had no relevant financial disclosures.

of nearly 95,000 patients.

Although previous studies have shown a higher risk for comorbid conditions in people with psoriasis, compared with those without psoriasis, data on the occurrence of severe and rare infections in patients with psoriasis are limited, wrote Nikolai Loft, MD, of the department of dermatology and allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital, Gentofte, and colleagues.

Psoriasis patients are often treated with immunosuppressive therapies that may promote or aggravate infections; therefore, a better understanding of psoriasis and risk of infections is needed, they said. In a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology, Dr. Loft and his coinvestigators reviewed data on adults aged 18 years and older from the Danish National Patient Register between Jan. 1, 1997 and Dec. 31, 2018. The study population included 94,450 adults with psoriasis and 566,700 matched controls. Patients with any type of psoriasis and any degree of severity were included.

The primary outcome was the occurrence of severe infections, defined as those requiring assessment at a hospital, and rare infections, defined as HIV, TB, HBV, and HCV. The median age of the participants was 52.3 years, and slightly more than half were women.

Overall, the incidence rate of severe and rare infections among patients with any type of psoriasis was 3,104.9 per 100,000 person-years, compared with 2,381.1 for controls, with a hazard ratio, adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, alcohol-related conditions, and Charlson comorbidity index (aHR) of 1.29.

For any infections resulting in hospitalization, the incidence rate was 2,005.1 vs. 1,531.8 per 100,000 person-years for patients with any type of psoriasis and controls, respectively.

The results were similar when severe infections and rare infections were analyzed separately. The incidence rate of severe infections was 3,080.6 and 2,364.4 per 100,000 person-years for patients with any psoriasis, compared with controls; the incidence rate for rare infections was 42.9 and 31.8 for all psoriasis patients and controls, respectively.

When the data were examined by psoriasis severity, the incidence rate of severe and rare infections among patients with severe psoriasis was 3,847.7 per 100,000 person-years, compared with 2,351.9 per 100,000 person years among controls (aHR, 1.58) and also higher than in patients with mild psoriasis. The incidence rate of severe and rare infections in patients with mild psoriasis (2,979.1 per 100,000 person-years) also was higher than in controls (aHR, 1.26).

Factors that might explain the increased infection risk with severe psoriasis include the altered immune environment in these patients, the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. Also, “patients with severe psoriasis are defined by their eligibility for systemics, either conventional or biologic,” and their increased infection risk may stem from these treatments, rather than disease severity itself, they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on such confounders as weight, body mass index, and smoking status, they added. Other limitations included potential surveillance bias because of greater TB screening, and the use of prescriptions, rather than the Psoriasis Area Severity Index, to define severity. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and suggest that patients with any type of psoriasis have higher rates of any infection, severe or rare, than the general population, the researchers concluded.

Data show need for clinician vigilance

Based on the 2020 Census data, an estimated 7.55 million adults in the United States have psoriasis, David Robles, MD, said in an interview. “Patients with psoriasis have a high risk for multiple comorbid conditions including metabolic syndrome, which is characterized by obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,” said Dr. Robles, a dermatologist in private practice in Pomona, Calif., who was not involved in the study. “Although these complications were previously attributed to diet and obesity, it has become clear that the proinflammatory cytokines associated with psoriasis may be playing an important role underlying the pathologic basis of these other comorbidities.”

There is an emerging body of literature “indicating that psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of infections,” he added. Research in this area is particularly important because of the increased risk of infections associated with many biologic and immune-modulating treatments for psoriasis, Dr. Robles noted.

The study findings “indicate that, as the severity of psoriasis increases, so does the risk of severe and rare infections,” he said. “This makes it imperative for clinicians to be alert to the possibility of severe or rare infections in patients with psoriasis, especially those with severe psoriasis, so that early intervention can be initiated.”

As for additional research, “as an immunologist and dermatologist, I cannot help but think about the possible role the genetic and cytokine pathways involved in psoriasis may be playing in modulating the immune system and/or microbiome, and whether this contributes to a higher risk of infections,” Dr. Robles said. “Just as it was discovered that patients with atopic dermatitis have decreased levels of antimicrobial peptides in their skin, making them susceptible to recurrent bacterial skin infections, we may find that the genetic and immunological changes associated with psoriasis may independently contribute to infection susceptibility,” he noted. “More basic immunology and virology research may one day shed light on this observation.”

The study was supported by Novartis. Lead author Dr. Loft disclosed serving as a speaker for Eli Lilly and Janssen Cilag, other authors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Novartis, and two authors are Novartis employees. Dr. Robles had no relevant financial disclosures.

of nearly 95,000 patients.

Although previous studies have shown a higher risk for comorbid conditions in people with psoriasis, compared with those without psoriasis, data on the occurrence of severe and rare infections in patients with psoriasis are limited, wrote Nikolai Loft, MD, of the department of dermatology and allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital, Gentofte, and colleagues.

Psoriasis patients are often treated with immunosuppressive therapies that may promote or aggravate infections; therefore, a better understanding of psoriasis and risk of infections is needed, they said. In a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology, Dr. Loft and his coinvestigators reviewed data on adults aged 18 years and older from the Danish National Patient Register between Jan. 1, 1997 and Dec. 31, 2018. The study population included 94,450 adults with psoriasis and 566,700 matched controls. Patients with any type of psoriasis and any degree of severity were included.

The primary outcome was the occurrence of severe infections, defined as those requiring assessment at a hospital, and rare infections, defined as HIV, TB, HBV, and HCV. The median age of the participants was 52.3 years, and slightly more than half were women.

Overall, the incidence rate of severe and rare infections among patients with any type of psoriasis was 3,104.9 per 100,000 person-years, compared with 2,381.1 for controls, with a hazard ratio, adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, alcohol-related conditions, and Charlson comorbidity index (aHR) of 1.29.

For any infections resulting in hospitalization, the incidence rate was 2,005.1 vs. 1,531.8 per 100,000 person-years for patients with any type of psoriasis and controls, respectively.

The results were similar when severe infections and rare infections were analyzed separately. The incidence rate of severe infections was 3,080.6 and 2,364.4 per 100,000 person-years for patients with any psoriasis, compared with controls; the incidence rate for rare infections was 42.9 and 31.8 for all psoriasis patients and controls, respectively.

When the data were examined by psoriasis severity, the incidence rate of severe and rare infections among patients with severe psoriasis was 3,847.7 per 100,000 person-years, compared with 2,351.9 per 100,000 person years among controls (aHR, 1.58) and also higher than in patients with mild psoriasis. The incidence rate of severe and rare infections in patients with mild psoriasis (2,979.1 per 100,000 person-years) also was higher than in controls (aHR, 1.26).

Factors that might explain the increased infection risk with severe psoriasis include the altered immune environment in these patients, the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. Also, “patients with severe psoriasis are defined by their eligibility for systemics, either conventional or biologic,” and their increased infection risk may stem from these treatments, rather than disease severity itself, they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on such confounders as weight, body mass index, and smoking status, they added. Other limitations included potential surveillance bias because of greater TB screening, and the use of prescriptions, rather than the Psoriasis Area Severity Index, to define severity. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and suggest that patients with any type of psoriasis have higher rates of any infection, severe or rare, than the general population, the researchers concluded.

Data show need for clinician vigilance

Based on the 2020 Census data, an estimated 7.55 million adults in the United States have psoriasis, David Robles, MD, said in an interview. “Patients with psoriasis have a high risk for multiple comorbid conditions including metabolic syndrome, which is characterized by obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,” said Dr. Robles, a dermatologist in private practice in Pomona, Calif., who was not involved in the study. “Although these complications were previously attributed to diet and obesity, it has become clear that the proinflammatory cytokines associated with psoriasis may be playing an important role underlying the pathologic basis of these other comorbidities.”

There is an emerging body of literature “indicating that psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of infections,” he added. Research in this area is particularly important because of the increased risk of infections associated with many biologic and immune-modulating treatments for psoriasis, Dr. Robles noted.

The study findings “indicate that, as the severity of psoriasis increases, so does the risk of severe and rare infections,” he said. “This makes it imperative for clinicians to be alert to the possibility of severe or rare infections in patients with psoriasis, especially those with severe psoriasis, so that early intervention can be initiated.”

As for additional research, “as an immunologist and dermatologist, I cannot help but think about the possible role the genetic and cytokine pathways involved in psoriasis may be playing in modulating the immune system and/or microbiome, and whether this contributes to a higher risk of infections,” Dr. Robles said. “Just as it was discovered that patients with atopic dermatitis have decreased levels of antimicrobial peptides in their skin, making them susceptible to recurrent bacterial skin infections, we may find that the genetic and immunological changes associated with psoriasis may independently contribute to infection susceptibility,” he noted. “More basic immunology and virology research may one day shed light on this observation.”

The study was supported by Novartis. Lead author Dr. Loft disclosed serving as a speaker for Eli Lilly and Janssen Cilag, other authors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including Novartis, and two authors are Novartis employees. Dr. Robles had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

FDA-cleared panties could reduce STI risk during oral sex

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Are physician white coats becoming obsolete? How docs dress for work now

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Trisha Pasricha, MD, a gastroenterologist and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was talking to a patient who had been hospitalized for a peptic ulcer.

Like other physicians in her institution, Dr. Pasricha was wearing scrubs instead of a white coat, out of concern that the white coat might be more prone to accumulating or transmitting COVID-19 pathogens. Her badge identified her as a physician, and she introduced herself clearly as “Dr. Pasricha.”

The patient “required an emergent procedure, which I discussed with him,” Dr. Pasricha told this news organization. “I went over what the procedure entailed, the risks and benefits, and the need for informed consent. The patient nodded and seemed to understand, but at the end of the discussion he said: ‘That all sounds fine, but I need to speak to the doctor first.’ ”

Dr. Pasricha was taken aback. She wondered: “Who did he think I was the whole time that I was reviewing medical concerns, explaining medical concepts, and describing a procedure in a way that a physician would describe it?”

She realized the reason he didn’t correctly identify her was that, clad only in scrubs, she was less easily recognizable as a physician. And to be misidentified as technicians, nurses, physician assistants, or other health care professionals, according to Dr. Pasricha.

Dr. Pasricha said she has been the recipient of this “implicit bias” not only from patients but also from members of the health care team, and added that other female colleagues have told her that they’ve had similar experiences, especially when they’re not wearing a white coat.

Changing times, changing trends

When COVID-19 began to spread, “there was an initial concern that COVID-19 was passed through surfaces, and concerns about whether white coats could carry viral particles,” according to Jordan Steinberg, MD, PhD, surgical director of the craniofacial program at Nicklaus Children’s Pediatric Specialists/Nicklaus Children’s Health System, Miami. “Hospitals didn’t want to launder the white coats as frequently as scrubs, due to cost concerns. There was also a concern raised that a necktie might dangle in patients’ faces, coming in closer contact with pathogens, so more physicians were wearing scrubs.”

Yet even before the pandemic, physician attire in hospital and outpatient settings had started to change. Dr. Steinberg, who is also a clinical associate professor at Florida International University, Miami, told this news organization that, in his previous appointment at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, he and his colleagues “had noticed in our institution, as well as other facilities, an increasing trend that moved from white coats worn over professional attire toward more casual dress among medical staff – increased wearing of casual fleece or softshell jackets with the institutional logo.”

This was especially true with trainees and the “younger generation,” who were preferring “what I would almost call ‘warm-up clothes,’ gym clothes, and less shirt-tie-white-coat attire for men or white-coats-and-business attire for women.” Dr. Steinberg thinks that some physicians prefer the fleece with the institutional logo “because it’s like wearing your favorite sports team jersey. It gives a sense of belonging.”

Todd Shaffer, MD, MBA, a family physician at University Physicians Associates, Truman Medical Centers and the Lakewood Medical Pavilion, Kansas City, Mo., has been at his institution for 30 years and has seen a similar trend. “At one point, things were very formal,” he told this news organization. But attire was already becoming less formal before the pandemic, and new changes took place during the pandemic, as physicians began wearing scrubs instead of white coats because of fears of viral contamination.

Now, there is less concern about potential viral contamination with the white coat. Yet many physicians continue to wear scrubs – especially those who interact with patients with COVID – and it has become more acceptable to do so, or to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) over ordinary clothing, but it is less common in routine clinical practice, said Dr. Shaffer, a member of the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“The world has changed since COVID. People feel more comfortable dressing more casually during professional Zoom calls, when they have the convenience of working from home,” said Dr. Shaffer, who is also a professor of family medicine at University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Dr. Shaffer himself hasn’t worn a white coat for years. “I’m more likely to wear medium casual pants. I’ve bought some nicer shirts, so I still look professional and upbeat. I don’t always tuck in my shirt, and I don’t dress as formally.” He wears PPE and a mask and/or face shield when treating patients with COVID-19. And he wears a white coat “when someone wants a photograph taken with the doctors – with the stethoscope draped around my neck.”

Traditional symbol of medicine

Because of the changing mores, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues at Johns Hopkins wondered if there might still be a role for professional attire and white coats and what patients prefer. To investigate the question, they surveyed 487 U.S. adults in the spring of 2020.

Respondents were asked where and how frequently they see health care professionals wearing white coats, scrubs, and fleece or softshell jackets. They were also shown photographs depicting models wearing various types of attire commonly seen in health care settings and were asked to rank the “health care provider’s” level of experience, professionalism, and friendliness.

The majority of participants said they had seen health care practitioners in white coats “most of the time,” in scrubs “sometimes,” and in fleece or softshell jackets “rarely.” Models in white coats were regarded by respondents as more experienced and professional, although those in softshell jackets were perceived as friendlier.

There were age as well as regional differences in the responses, Dr. Steinberg said. Older respondents were significantly more likely than their younger counterparts to perceive a model wearing a white coat over business attire as being more experienced, and – in all regions of the United States except the West coast – respondents gave lower professionalism scores to providers wearing fleece jackets with scrubs underneath.

Respondents tended to prefer surgeons wearing a white coat with scrubs underneath, while a white coat over business attire was the preferred dress code for family physicians and dermatologists.

“People tended to respond as if there was a more professional element in the white coat. The age-old symbol of the white coat still marked something important,” Dr. Steinberg said. “Our data suggest that the white coat isn’t ready to die just yet. People still see an air of authority and a traditional symbol of medicine. Nevertheless, I do think it will become less common than it used to be, especially in certain regions of the country.”

Organic, subtle changes

Christopher Petrilli, MD, assistant professor at New York University, conducted research in 2018 regarding physician attire by surveying over 4,000 patients in 10 U.S. academic hospitals. His team found that most patients continued to prefer physicians to wear formal attire under a white coat, especially older respondents.

Dr. Petrilli and colleagues have been studying the issue of physician attire since 2015. “The big issue when we did our initial study – which might not be accurate anymore – is that few hospitals actually had a uniform dress code,” said Dr. Petrilli, the medical director of clinical documentation improvement and the clinical lead of value-based medicine at NYU Langone Hospitals. “When we looked at ‘honor roll hospitals’ during our study, we cold-called these hospitals and also looked online for their dress code policies. Except for the Mayo Clinic, hospitals that had dress code policies were more generic.”

For example, the American Medical Association guidance merely states that attire should be “clean, unsoiled, and appropriate to the setting of care” and recommends weighing research findings regarding textile transmission of health care–associated infections when individual institutions determine their dress code policies. The AMA’s last policy discussion took place in 2015 and its guidance has not changed since the pandemic.

Regardless of what institutions and patients prefer, some research suggests that many physicians would prefer to stay with wearing scrubs rather than reverting to the white coat. One study of 151 hospitalists, conducted in Ireland, found that three-quarters wanted scrubs to remain standard attire, despite the fact that close to half had experienced changes in patients› perception in the absence of their white coat and “professional attire.”

Jennifer Workman, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric critical care, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in an interview that, as the pandemic has “waxed and waned, some trends have reverted to what they were prepandemic, but other physicians have stayed with wearing scrubs.”

Much depends on practice setting, said Dr. Workman, who is also the medical director of pediatric sepsis at Intermountain Care. In pediatrics, for example, many physicians prefer not to wear white coats when they are interacting with young children or adolescents.

Like Dr. Shaffer, Dr. Workman has seen changes in physicians’ attire during video meetings, where they often dress more casually, perhaps wearing sweatshirts. And in the hospital, more are continuing to wear scrubs. “But I don’t see it as people trying to consciously experiment or push boundaries,” she said. “I see it as a more organic, subtle shift.”

Dr. Petrilli thinks that, at this juncture, it’s “pretty heterogeneous as to who is going to return to formal attire and a white coat and who won’t.” Further research needs to be done into currently evolving trends. “We need a more thorough survey looking at changes. We need to ask [physician respondents]: ‘What is your current attire, and how has it changed?’ ”

Navigating the gender divide

In their study, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues found that respondents perceived a male model wearing business attire underneath any type of outerwear (white coat or fleece) to be significantly more professional than a female model wearing the same attire. Respondents also perceived males wearing scrubs to be more professional than females wearing scrubs.

Male models in white coats over business attire were also more likely to be identified as physicians, compared with female models in the same attire. Females were also more likely to be misidentified as nonphysician health care professionals.

Shikha Jain, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center in Chicago, said that Dr. Steinberg’s study confirmed experiences that she and other female physicians have had. Wearing a white coat makes it more likely that a patient will identify you as a physician, but women are less likely to be identified as physicians, regardless of what they wear.

“I think that individuals of color and especially people with intersectional identities – such as women of color – are even more frequently targeted and stereotyped. Numerous studies have shown that a person of color is less likely to be seen as an authority figure, and studies have shown that physicians of color are less likely to be identified as ‘physicians,’ compared to a Caucasian individual,” she said.

Does that mean that female physicians should revert back to prepandemic white coats rather than scrubs or more casual attire? Not necessarily, according to Dr. Jain.

“The typical dress code guidance is that physicians should dress ‘professionally,’ but what that means is a question that needs to be addressed,” Dr. Jain said. “Medicine has evolved from the days of house calls, in which one’s patient population is a very small, intimate group of people in the physician’s community. Yet now, we’ve given rebirth to the ‘house call’ when we do telemedicine with a patient in his or her home. And in the old days, doctors often had offices their homes and now, with telemedicine, patients often see the interior of their physician’s home.” As the delivery of medicine evolves, concepts of “professionalism” – what is defined as “casual” and what is defined as “formal” – is also evolving.

The more important issue, according to Dr. Jain, is to “continue the conversation” about the discrepancies between how men and women are treated in medicine. Attire is one arena in which this issue plays out, and it’s a “bigger picture” that goes beyond the white coat.

Dr. Jain has been “told by patients that a particular outfit doesn’t make me look like a doctor or that scrubs make me look younger. I don’t think my male colleagues have been subjected to these types of remarks, but my female colleagues have heard them as well.”

Even fellow health care providers have commented on Dr. Jain’s clothing. She was presenting at a major medical conference via video and was wearing a similar outfit to the one she wore for her headshot. “Thirty seconds before beginning my talk, one of the male physicians said: ‘Are you wearing the same outfit you wore for your headshot?’ I can’t imagine a man commenting that another man was wearing the same jacket or tie that he wore in the photograph. I found it odd that this was something that someone felt the need to comment on right before I was about to address a large group of people in a professional capacity.”

Addressing these systemic issues “needs to be done and amplified not only by women but also by men in medicine,” said Dr. Jain, founder and director of Women in Medicine, an organization consisting of women physicians whose goal is to “find and implement solutions to gender inequity.”

Dr. Jain said the organization offers an Inclusive Leadership Development Lab – a course specifically for men in health care leadership positions to learn how to be more equitable, inclusive leaders.

A personal decision

Dr. Pasricha hopes she “handled the patient’s misidentification graciously.” She explained to him that she would be the physician conducting the procedure. The patient was initially “a little embarrassed” that he had misidentified her, but she put him at ease and “we moved forward quickly.”

At this point, although some of her colleagues have continued to wear scrubs or have returned to wearing fleeces with hospital logos, Dr. Pasricha prefers to wear a white coat in both inpatient and outpatient settings because it reduces the likelihood of misidentification.

And white coats can be more convenient – for example, Dr. Jain likes the fact that the white coat has pockets where she can put her stethoscope and other items, while some of her professional clothes don’t always have pockets.

Dr. Jain noted that there are some institutions where everyone seems to wear white coats, not only the physician – “from the chaplain to the phlebotomist to the social worker.” In those settings, the white coat no longer distinguishes physicians from nonphysicians, and so wearing a white coat may not confer additional credibility as a physician.

Nevertheless, “if you want to wear a white coat, if you feel it gives you that added level of authority, if you feel it tells people more clearly that you’re a physician, by all means go ahead and do so,” she said. “There’s no ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy or solution. What’s more important than your clothing is your professionalism.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Trisha Pasricha, MD, a gastroenterologist and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was talking to a patient who had been hospitalized for a peptic ulcer.

Like other physicians in her institution, Dr. Pasricha was wearing scrubs instead of a white coat, out of concern that the white coat might be more prone to accumulating or transmitting COVID-19 pathogens. Her badge identified her as a physician, and she introduced herself clearly as “Dr. Pasricha.”

The patient “required an emergent procedure, which I discussed with him,” Dr. Pasricha told this news organization. “I went over what the procedure entailed, the risks and benefits, and the need for informed consent. The patient nodded and seemed to understand, but at the end of the discussion he said: ‘That all sounds fine, but I need to speak to the doctor first.’ ”

Dr. Pasricha was taken aback. She wondered: “Who did he think I was the whole time that I was reviewing medical concerns, explaining medical concepts, and describing a procedure in a way that a physician would describe it?”

She realized the reason he didn’t correctly identify her was that, clad only in scrubs, she was less easily recognizable as a physician. And to be misidentified as technicians, nurses, physician assistants, or other health care professionals, according to Dr. Pasricha.

Dr. Pasricha said she has been the recipient of this “implicit bias” not only from patients but also from members of the health care team, and added that other female colleagues have told her that they’ve had similar experiences, especially when they’re not wearing a white coat.

Changing times, changing trends

When COVID-19 began to spread, “there was an initial concern that COVID-19 was passed through surfaces, and concerns about whether white coats could carry viral particles,” according to Jordan Steinberg, MD, PhD, surgical director of the craniofacial program at Nicklaus Children’s Pediatric Specialists/Nicklaus Children’s Health System, Miami. “Hospitals didn’t want to launder the white coats as frequently as scrubs, due to cost concerns. There was also a concern raised that a necktie might dangle in patients’ faces, coming in closer contact with pathogens, so more physicians were wearing scrubs.”

Yet even before the pandemic, physician attire in hospital and outpatient settings had started to change. Dr. Steinberg, who is also a clinical associate professor at Florida International University, Miami, told this news organization that, in his previous appointment at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, he and his colleagues “had noticed in our institution, as well as other facilities, an increasing trend that moved from white coats worn over professional attire toward more casual dress among medical staff – increased wearing of casual fleece or softshell jackets with the institutional logo.”

This was especially true with trainees and the “younger generation,” who were preferring “what I would almost call ‘warm-up clothes,’ gym clothes, and less shirt-tie-white-coat attire for men or white-coats-and-business attire for women.” Dr. Steinberg thinks that some physicians prefer the fleece with the institutional logo “because it’s like wearing your favorite sports team jersey. It gives a sense of belonging.”

Todd Shaffer, MD, MBA, a family physician at University Physicians Associates, Truman Medical Centers and the Lakewood Medical Pavilion, Kansas City, Mo., has been at his institution for 30 years and has seen a similar trend. “At one point, things were very formal,” he told this news organization. But attire was already becoming less formal before the pandemic, and new changes took place during the pandemic, as physicians began wearing scrubs instead of white coats because of fears of viral contamination.

Now, there is less concern about potential viral contamination with the white coat. Yet many physicians continue to wear scrubs – especially those who interact with patients with COVID – and it has become more acceptable to do so, or to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) over ordinary clothing, but it is less common in routine clinical practice, said Dr. Shaffer, a member of the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“The world has changed since COVID. People feel more comfortable dressing more casually during professional Zoom calls, when they have the convenience of working from home,” said Dr. Shaffer, who is also a professor of family medicine at University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Dr. Shaffer himself hasn’t worn a white coat for years. “I’m more likely to wear medium casual pants. I’ve bought some nicer shirts, so I still look professional and upbeat. I don’t always tuck in my shirt, and I don’t dress as formally.” He wears PPE and a mask and/or face shield when treating patients with COVID-19. And he wears a white coat “when someone wants a photograph taken with the doctors – with the stethoscope draped around my neck.”

Traditional symbol of medicine

Because of the changing mores, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues at Johns Hopkins wondered if there might still be a role for professional attire and white coats and what patients prefer. To investigate the question, they surveyed 487 U.S. adults in the spring of 2020.

Respondents were asked where and how frequently they see health care professionals wearing white coats, scrubs, and fleece or softshell jackets. They were also shown photographs depicting models wearing various types of attire commonly seen in health care settings and were asked to rank the “health care provider’s” level of experience, professionalism, and friendliness.

The majority of participants said they had seen health care practitioners in white coats “most of the time,” in scrubs “sometimes,” and in fleece or softshell jackets “rarely.” Models in white coats were regarded by respondents as more experienced and professional, although those in softshell jackets were perceived as friendlier.

There were age as well as regional differences in the responses, Dr. Steinberg said. Older respondents were significantly more likely than their younger counterparts to perceive a model wearing a white coat over business attire as being more experienced, and – in all regions of the United States except the West coast – respondents gave lower professionalism scores to providers wearing fleece jackets with scrubs underneath.

Respondents tended to prefer surgeons wearing a white coat with scrubs underneath, while a white coat over business attire was the preferred dress code for family physicians and dermatologists.

“People tended to respond as if there was a more professional element in the white coat. The age-old symbol of the white coat still marked something important,” Dr. Steinberg said. “Our data suggest that the white coat isn’t ready to die just yet. People still see an air of authority and a traditional symbol of medicine. Nevertheless, I do think it will become less common than it used to be, especially in certain regions of the country.”

Organic, subtle changes

Christopher Petrilli, MD, assistant professor at New York University, conducted research in 2018 regarding physician attire by surveying over 4,000 patients in 10 U.S. academic hospitals. His team found that most patients continued to prefer physicians to wear formal attire under a white coat, especially older respondents.

Dr. Petrilli and colleagues have been studying the issue of physician attire since 2015. “The big issue when we did our initial study – which might not be accurate anymore – is that few hospitals actually had a uniform dress code,” said Dr. Petrilli, the medical director of clinical documentation improvement and the clinical lead of value-based medicine at NYU Langone Hospitals. “When we looked at ‘honor roll hospitals’ during our study, we cold-called these hospitals and also looked online for their dress code policies. Except for the Mayo Clinic, hospitals that had dress code policies were more generic.”

For example, the American Medical Association guidance merely states that attire should be “clean, unsoiled, and appropriate to the setting of care” and recommends weighing research findings regarding textile transmission of health care–associated infections when individual institutions determine their dress code policies. The AMA’s last policy discussion took place in 2015 and its guidance has not changed since the pandemic.

Regardless of what institutions and patients prefer, some research suggests that many physicians would prefer to stay with wearing scrubs rather than reverting to the white coat. One study of 151 hospitalists, conducted in Ireland, found that three-quarters wanted scrubs to remain standard attire, despite the fact that close to half had experienced changes in patients› perception in the absence of their white coat and “professional attire.”

Jennifer Workman, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric critical care, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in an interview that, as the pandemic has “waxed and waned, some trends have reverted to what they were prepandemic, but other physicians have stayed with wearing scrubs.”

Much depends on practice setting, said Dr. Workman, who is also the medical director of pediatric sepsis at Intermountain Care. In pediatrics, for example, many physicians prefer not to wear white coats when they are interacting with young children or adolescents.

Like Dr. Shaffer, Dr. Workman has seen changes in physicians’ attire during video meetings, where they often dress more casually, perhaps wearing sweatshirts. And in the hospital, more are continuing to wear scrubs. “But I don’t see it as people trying to consciously experiment or push boundaries,” she said. “I see it as a more organic, subtle shift.”

Dr. Petrilli thinks that, at this juncture, it’s “pretty heterogeneous as to who is going to return to formal attire and a white coat and who won’t.” Further research needs to be done into currently evolving trends. “We need a more thorough survey looking at changes. We need to ask [physician respondents]: ‘What is your current attire, and how has it changed?’ ”

Navigating the gender divide

In their study, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues found that respondents perceived a male model wearing business attire underneath any type of outerwear (white coat or fleece) to be significantly more professional than a female model wearing the same attire. Respondents also perceived males wearing scrubs to be more professional than females wearing scrubs.

Male models in white coats over business attire were also more likely to be identified as physicians, compared with female models in the same attire. Females were also more likely to be misidentified as nonphysician health care professionals.

Shikha Jain, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center in Chicago, said that Dr. Steinberg’s study confirmed experiences that she and other female physicians have had. Wearing a white coat makes it more likely that a patient will identify you as a physician, but women are less likely to be identified as physicians, regardless of what they wear.

“I think that individuals of color and especially people with intersectional identities – such as women of color – are even more frequently targeted and stereotyped. Numerous studies have shown that a person of color is less likely to be seen as an authority figure, and studies have shown that physicians of color are less likely to be identified as ‘physicians,’ compared to a Caucasian individual,” she said.

Does that mean that female physicians should revert back to prepandemic white coats rather than scrubs or more casual attire? Not necessarily, according to Dr. Jain.

“The typical dress code guidance is that physicians should dress ‘professionally,’ but what that means is a question that needs to be addressed,” Dr. Jain said. “Medicine has evolved from the days of house calls, in which one’s patient population is a very small, intimate group of people in the physician’s community. Yet now, we’ve given rebirth to the ‘house call’ when we do telemedicine with a patient in his or her home. And in the old days, doctors often had offices their homes and now, with telemedicine, patients often see the interior of their physician’s home.” As the delivery of medicine evolves, concepts of “professionalism” – what is defined as “casual” and what is defined as “formal” – is also evolving.

The more important issue, according to Dr. Jain, is to “continue the conversation” about the discrepancies between how men and women are treated in medicine. Attire is one arena in which this issue plays out, and it’s a “bigger picture” that goes beyond the white coat.

Dr. Jain has been “told by patients that a particular outfit doesn’t make me look like a doctor or that scrubs make me look younger. I don’t think my male colleagues have been subjected to these types of remarks, but my female colleagues have heard them as well.”

Even fellow health care providers have commented on Dr. Jain’s clothing. She was presenting at a major medical conference via video and was wearing a similar outfit to the one she wore for her headshot. “Thirty seconds before beginning my talk, one of the male physicians said: ‘Are you wearing the same outfit you wore for your headshot?’ I can’t imagine a man commenting that another man was wearing the same jacket or tie that he wore in the photograph. I found it odd that this was something that someone felt the need to comment on right before I was about to address a large group of people in a professional capacity.”

Addressing these systemic issues “needs to be done and amplified not only by women but also by men in medicine,” said Dr. Jain, founder and director of Women in Medicine, an organization consisting of women physicians whose goal is to “find and implement solutions to gender inequity.”

Dr. Jain said the organization offers an Inclusive Leadership Development Lab – a course specifically for men in health care leadership positions to learn how to be more equitable, inclusive leaders.

A personal decision

Dr. Pasricha hopes she “handled the patient’s misidentification graciously.” She explained to him that she would be the physician conducting the procedure. The patient was initially “a little embarrassed” that he had misidentified her, but she put him at ease and “we moved forward quickly.”

At this point, although some of her colleagues have continued to wear scrubs or have returned to wearing fleeces with hospital logos, Dr. Pasricha prefers to wear a white coat in both inpatient and outpatient settings because it reduces the likelihood of misidentification.

And white coats can be more convenient – for example, Dr. Jain likes the fact that the white coat has pockets where she can put her stethoscope and other items, while some of her professional clothes don’t always have pockets.

Dr. Jain noted that there are some institutions where everyone seems to wear white coats, not only the physician – “from the chaplain to the phlebotomist to the social worker.” In those settings, the white coat no longer distinguishes physicians from nonphysicians, and so wearing a white coat may not confer additional credibility as a physician.

Nevertheless, “if you want to wear a white coat, if you feel it gives you that added level of authority, if you feel it tells people more clearly that you’re a physician, by all means go ahead and do so,” she said. “There’s no ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy or solution. What’s more important than your clothing is your professionalism.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Trisha Pasricha, MD, a gastroenterologist and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was talking to a patient who had been hospitalized for a peptic ulcer.

Like other physicians in her institution, Dr. Pasricha was wearing scrubs instead of a white coat, out of concern that the white coat might be more prone to accumulating or transmitting COVID-19 pathogens. Her badge identified her as a physician, and she introduced herself clearly as “Dr. Pasricha.”

The patient “required an emergent procedure, which I discussed with him,” Dr. Pasricha told this news organization. “I went over what the procedure entailed, the risks and benefits, and the need for informed consent. The patient nodded and seemed to understand, but at the end of the discussion he said: ‘That all sounds fine, but I need to speak to the doctor first.’ ”

Dr. Pasricha was taken aback. She wondered: “Who did he think I was the whole time that I was reviewing medical concerns, explaining medical concepts, and describing a procedure in a way that a physician would describe it?”

She realized the reason he didn’t correctly identify her was that, clad only in scrubs, she was less easily recognizable as a physician. And to be misidentified as technicians, nurses, physician assistants, or other health care professionals, according to Dr. Pasricha.

Dr. Pasricha said she has been the recipient of this “implicit bias” not only from patients but also from members of the health care team, and added that other female colleagues have told her that they’ve had similar experiences, especially when they’re not wearing a white coat.

Changing times, changing trends