User login

For MD-IQ use only

The growing NP and PA workforce in hospital medicine

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

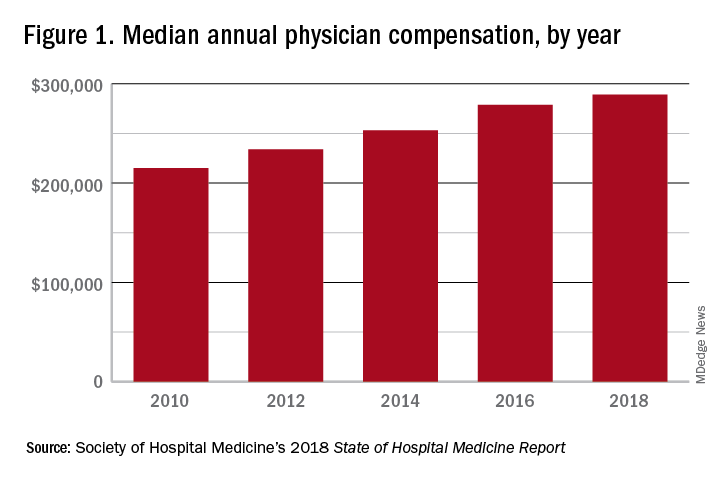

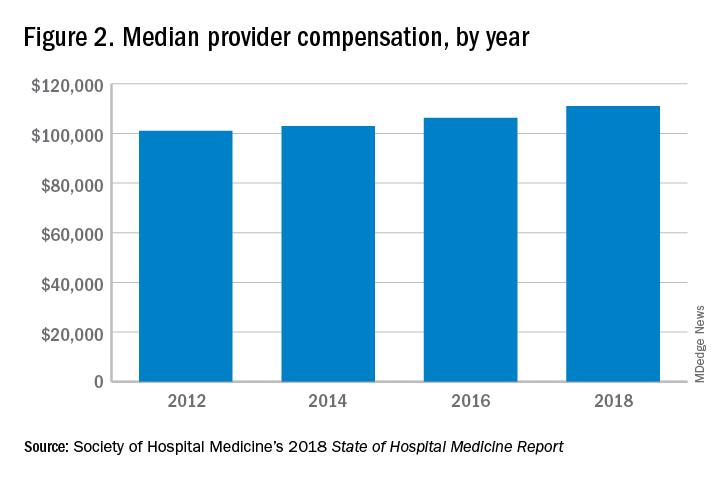

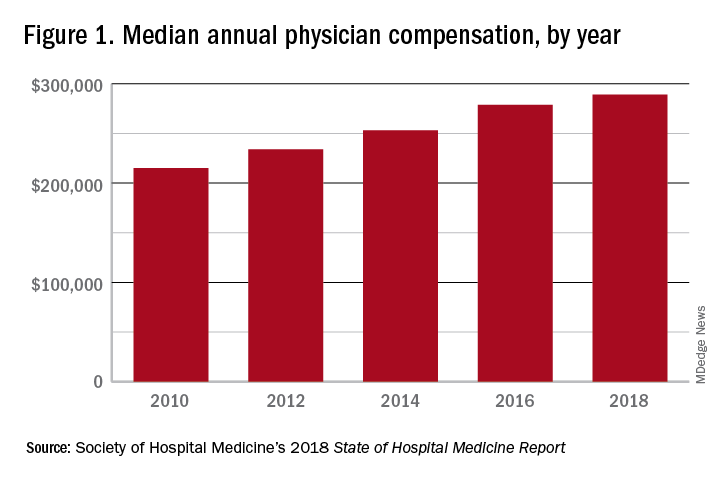

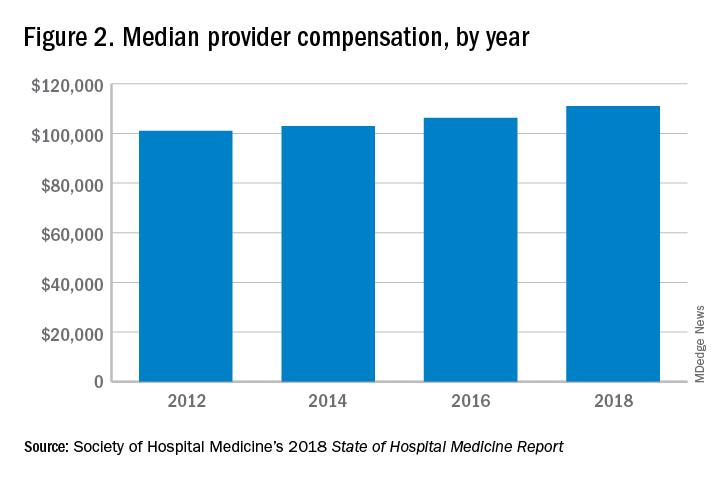

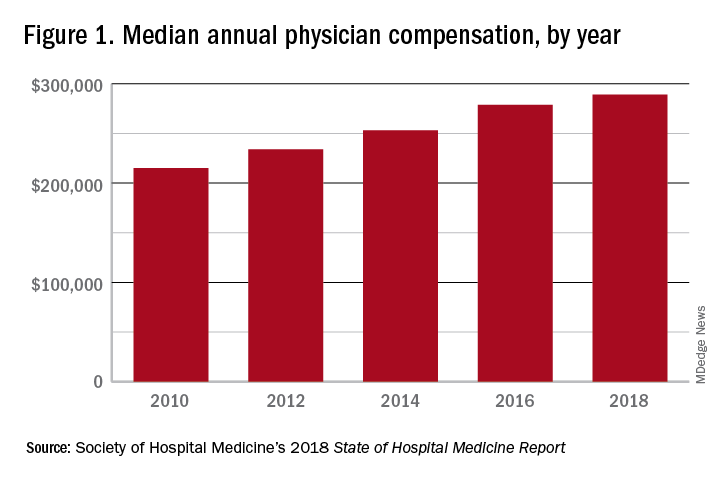

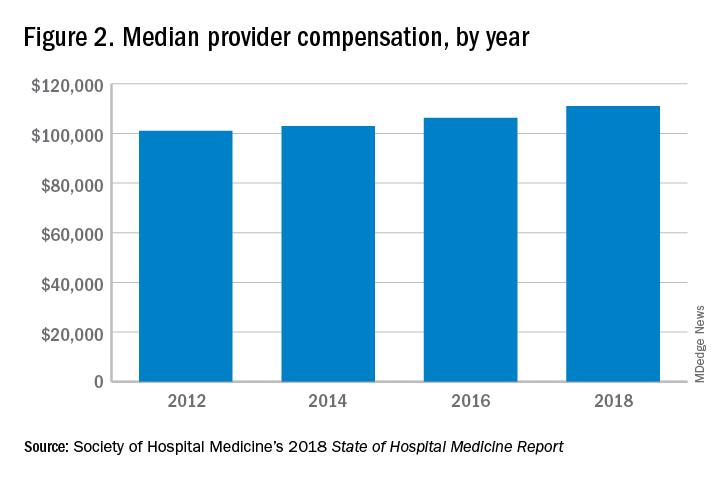

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

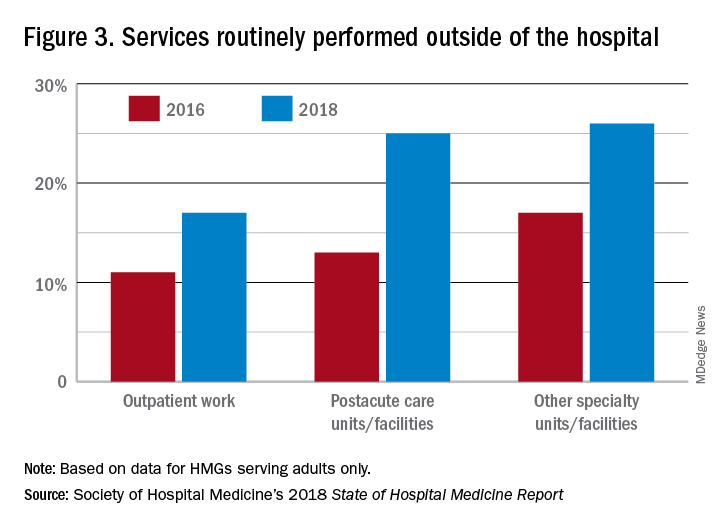

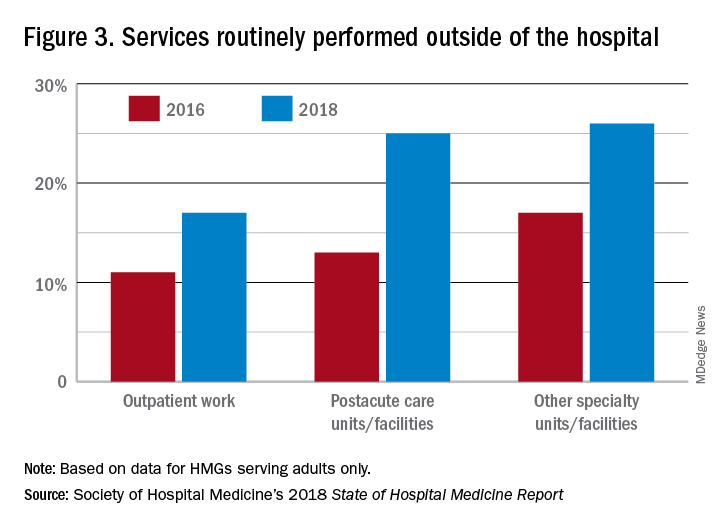

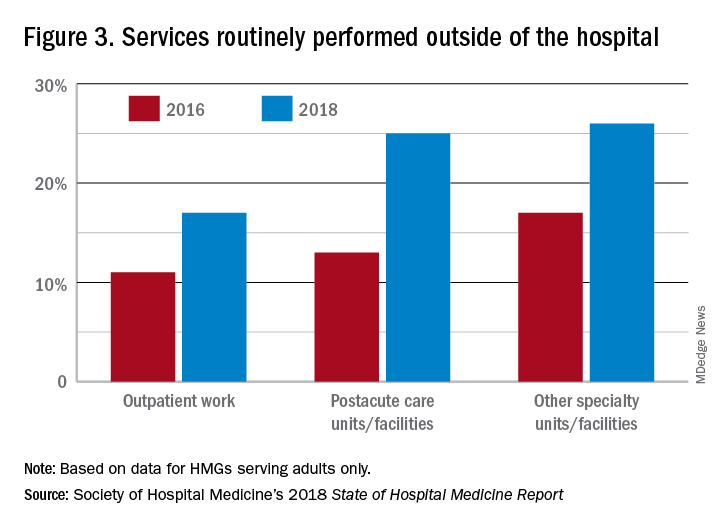

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

A cigarette in one hand and a Fitbit on the other

A cardiologist friend of mine told me a story about one of his patients. The man had recently been in to see him for an office visit. He had quite a scare needing two stents after an episode of prolonged chest pain and, during the office visit, apparently had said that he had “found religion” and was going to change his ways. He showed off the Fitbit that he had gotten and shared his excitement about using a new app to track his diet on his smart phone. His blood pressure was a little elevated, so my friend added a third antihypertensive in an effort to get his blood pressure under control. He referred the patient back to his primary care physician to address his elevated hemoglobin A1c.

My friend saw the patient again a couple of weeks later – this time at the mall. As he was driving through the parking lot, he noticed his patient sitting on a bench outside the entrance. He also noticed a cigarette in his patient’s right hand and saw the Fitbit still on his wrist. Now, it’s not that there is anything wrong with wearing a Fitbit, but …

My friend is an incredibly respectful person, and very nice. He decided not to say hello and risk embarrassing his patient, so he walked to a different door far from the bench and went inside. Nonetheless, the image bothered him. It bothered him enough to repeat the story to me 2 weeks later. It bothers me too.

The other day I was talking to a healthy young nurse with whom I work. She has been trying to get into shape, and her goal is to get to the gym 5 days a week after work. She read on a popular website that she should use a heart rate monitor to keep track of her training and that, if her heart rate is too slow, she should run faster and, if her heart rate is too fast, she should slow down. She was discouraged the other day, however, because her watch indicated that her pulse was going up to 170 while she was running hard, and she had heard that could be dangerous for her heart.

When she doesn’t push hard, though, she told me that her heart rate often plateaus at about 110, sometimes 115. She has been finding it difficult to achieve her calculated target heart rate of 120-160 beats per minute. She is frustrated and was going to skip her workout that evening. I explained to her that she should stop checking her pulse and just run – if she felt she was running too slow she could run faster.

With everything that we have learned about science and technology, the reality is that we are still people, with all our weaknesses and strengths. We often set goals with ambivalence, then rush forward hoping that a technological solution will move us in the direction we think we want to move. Unfortunately, owning a Fitbit will not make us more fit, and checking our pulse every five minutes while working out will not lead to a better exercise session. With the availability of so much technology for tracking our daily exercise, vital signs, and various other measures of health, we need to be more careful than ever to determine specifically what it is that we are trying to accomplish with the use of our technology.

When it comes to good health, it is the fundamentals that matter, and achieving the fundamentals requires being mindful and making repeated efforts to master them. For almost all adults, the most important habits to develop are still related to diet and exercise. Consuming the right diet and exercising adequately requires that the correct choices be made each and every day, all day long. Technology can help but will not do it for us. We need to be thoughtful about how we use technology and explicit about how we expect it to help. After a reasonable amount of time, we should evaluate to see if it is working for us. If it is, then we should continue to use it. If it is not, then we should stop using it or make a different change, like performing a new type of exercise.

Our goal should be to have intelligent empathic integration of technological and behavioral techniques to achieve an optimal health outcome. Putting running shoes by the bed at night is a great thing to do to encourage us to run in the morning. Choosing motivational music can help us get the energy and enthusiasm to go for that run (our favorites include the Rocky theme song and “I Didn’t Come this Far to Only Come this Far”). A visual reminder over the refrigerator can “nudge” us to make good choices as we open the door.

For those who want to learn more about how to integrate behavioral management into their advice for patients we highly recommend reading “Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard” by Chip Heath and “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness” by Richard Thaler. We have always been, and remain, excited about the promise of technology to help us accomplish our goals. That said, we told the nurse to stop checking her pulse, to put on some music, and to appreciate the leaves on the trees this autumn while she was running. As for the gentleman outside the mall, well …

We are interested in your thoughts. Please email us at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

A cardiologist friend of mine told me a story about one of his patients. The man had recently been in to see him for an office visit. He had quite a scare needing two stents after an episode of prolonged chest pain and, during the office visit, apparently had said that he had “found religion” and was going to change his ways. He showed off the Fitbit that he had gotten and shared his excitement about using a new app to track his diet on his smart phone. His blood pressure was a little elevated, so my friend added a third antihypertensive in an effort to get his blood pressure under control. He referred the patient back to his primary care physician to address his elevated hemoglobin A1c.

My friend saw the patient again a couple of weeks later – this time at the mall. As he was driving through the parking lot, he noticed his patient sitting on a bench outside the entrance. He also noticed a cigarette in his patient’s right hand and saw the Fitbit still on his wrist. Now, it’s not that there is anything wrong with wearing a Fitbit, but …

My friend is an incredibly respectful person, and very nice. He decided not to say hello and risk embarrassing his patient, so he walked to a different door far from the bench and went inside. Nonetheless, the image bothered him. It bothered him enough to repeat the story to me 2 weeks later. It bothers me too.

The other day I was talking to a healthy young nurse with whom I work. She has been trying to get into shape, and her goal is to get to the gym 5 days a week after work. She read on a popular website that she should use a heart rate monitor to keep track of her training and that, if her heart rate is too slow, she should run faster and, if her heart rate is too fast, she should slow down. She was discouraged the other day, however, because her watch indicated that her pulse was going up to 170 while she was running hard, and she had heard that could be dangerous for her heart.

When she doesn’t push hard, though, she told me that her heart rate often plateaus at about 110, sometimes 115. She has been finding it difficult to achieve her calculated target heart rate of 120-160 beats per minute. She is frustrated and was going to skip her workout that evening. I explained to her that she should stop checking her pulse and just run – if she felt she was running too slow she could run faster.

With everything that we have learned about science and technology, the reality is that we are still people, with all our weaknesses and strengths. We often set goals with ambivalence, then rush forward hoping that a technological solution will move us in the direction we think we want to move. Unfortunately, owning a Fitbit will not make us more fit, and checking our pulse every five minutes while working out will not lead to a better exercise session. With the availability of so much technology for tracking our daily exercise, vital signs, and various other measures of health, we need to be more careful than ever to determine specifically what it is that we are trying to accomplish with the use of our technology.

When it comes to good health, it is the fundamentals that matter, and achieving the fundamentals requires being mindful and making repeated efforts to master them. For almost all adults, the most important habits to develop are still related to diet and exercise. Consuming the right diet and exercising adequately requires that the correct choices be made each and every day, all day long. Technology can help but will not do it for us. We need to be thoughtful about how we use technology and explicit about how we expect it to help. After a reasonable amount of time, we should evaluate to see if it is working for us. If it is, then we should continue to use it. If it is not, then we should stop using it or make a different change, like performing a new type of exercise.

Our goal should be to have intelligent empathic integration of technological and behavioral techniques to achieve an optimal health outcome. Putting running shoes by the bed at night is a great thing to do to encourage us to run in the morning. Choosing motivational music can help us get the energy and enthusiasm to go for that run (our favorites include the Rocky theme song and “I Didn’t Come this Far to Only Come this Far”). A visual reminder over the refrigerator can “nudge” us to make good choices as we open the door.

For those who want to learn more about how to integrate behavioral management into their advice for patients we highly recommend reading “Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard” by Chip Heath and “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness” by Richard Thaler. We have always been, and remain, excited about the promise of technology to help us accomplish our goals. That said, we told the nurse to stop checking her pulse, to put on some music, and to appreciate the leaves on the trees this autumn while she was running. As for the gentleman outside the mall, well …

We are interested in your thoughts. Please email us at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

A cardiologist friend of mine told me a story about one of his patients. The man had recently been in to see him for an office visit. He had quite a scare needing two stents after an episode of prolonged chest pain and, during the office visit, apparently had said that he had “found religion” and was going to change his ways. He showed off the Fitbit that he had gotten and shared his excitement about using a new app to track his diet on his smart phone. His blood pressure was a little elevated, so my friend added a third antihypertensive in an effort to get his blood pressure under control. He referred the patient back to his primary care physician to address his elevated hemoglobin A1c.

My friend saw the patient again a couple of weeks later – this time at the mall. As he was driving through the parking lot, he noticed his patient sitting on a bench outside the entrance. He also noticed a cigarette in his patient’s right hand and saw the Fitbit still on his wrist. Now, it’s not that there is anything wrong with wearing a Fitbit, but …

My friend is an incredibly respectful person, and very nice. He decided not to say hello and risk embarrassing his patient, so he walked to a different door far from the bench and went inside. Nonetheless, the image bothered him. It bothered him enough to repeat the story to me 2 weeks later. It bothers me too.

The other day I was talking to a healthy young nurse with whom I work. She has been trying to get into shape, and her goal is to get to the gym 5 days a week after work. She read on a popular website that she should use a heart rate monitor to keep track of her training and that, if her heart rate is too slow, she should run faster and, if her heart rate is too fast, she should slow down. She was discouraged the other day, however, because her watch indicated that her pulse was going up to 170 while she was running hard, and she had heard that could be dangerous for her heart.

When she doesn’t push hard, though, she told me that her heart rate often plateaus at about 110, sometimes 115. She has been finding it difficult to achieve her calculated target heart rate of 120-160 beats per minute. She is frustrated and was going to skip her workout that evening. I explained to her that she should stop checking her pulse and just run – if she felt she was running too slow she could run faster.

With everything that we have learned about science and technology, the reality is that we are still people, with all our weaknesses and strengths. We often set goals with ambivalence, then rush forward hoping that a technological solution will move us in the direction we think we want to move. Unfortunately, owning a Fitbit will not make us more fit, and checking our pulse every five minutes while working out will not lead to a better exercise session. With the availability of so much technology for tracking our daily exercise, vital signs, and various other measures of health, we need to be more careful than ever to determine specifically what it is that we are trying to accomplish with the use of our technology.

When it comes to good health, it is the fundamentals that matter, and achieving the fundamentals requires being mindful and making repeated efforts to master them. For almost all adults, the most important habits to develop are still related to diet and exercise. Consuming the right diet and exercising adequately requires that the correct choices be made each and every day, all day long. Technology can help but will not do it for us. We need to be thoughtful about how we use technology and explicit about how we expect it to help. After a reasonable amount of time, we should evaluate to see if it is working for us. If it is, then we should continue to use it. If it is not, then we should stop using it or make a different change, like performing a new type of exercise.

Our goal should be to have intelligent empathic integration of technological and behavioral techniques to achieve an optimal health outcome. Putting running shoes by the bed at night is a great thing to do to encourage us to run in the morning. Choosing motivational music can help us get the energy and enthusiasm to go for that run (our favorites include the Rocky theme song and “I Didn’t Come this Far to Only Come this Far”). A visual reminder over the refrigerator can “nudge” us to make good choices as we open the door.

For those who want to learn more about how to integrate behavioral management into their advice for patients we highly recommend reading “Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard” by Chip Heath and “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness” by Richard Thaler. We have always been, and remain, excited about the promise of technology to help us accomplish our goals. That said, we told the nurse to stop checking her pulse, to put on some music, and to appreciate the leaves on the trees this autumn while she was running. As for the gentleman outside the mall, well …

We are interested in your thoughts. Please email us at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

GAO calls out HHS’ poor oversight of administrative costs of Medicaid work requirements

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services needs to be doing a better job overseeing the administrative costs associated with the implementation of work requirements in Medicaid, the Government Accountability Office said in a new report.

The government watchdog found two key weaknesses in CMS’s oversight of the administrative costs of the Medicaid demonstration projects related to work requirements for Medicaid.

First, the GAO report notes that no consideration of the administrative costs of the work requirements is given during the administration of the approval process.

The GAO reports that, of five states’ approvals, the estimated administrative costs range from the low end of $6.1 million for New Hampshire (with 50,000 beneficiaries subject to the work requirement) to $271.6 million for Kentucky (with 620,000 beneficiaries subject to the work requirement). Indiana, with 420,000 beneficiaries subject to work requirements, has an estimated cost of $35.1 million.

A significant portion of Kentucky’s funding was for a the development of a new information technology system to help track work requirements.

“GAO found that CMS does not require states to provide projections of administrative costs when requesting demonstration approvals,” the report states. “Thus, the cost of administering demonstrations, including those with work requirements, is not transparent to the public or included in CMS’s assessment of whether a demonstration is budget neutral – that is, that federal spending will be no higher under the demonstration than it would have been without it.”

The GAO also reported that, by not requiring cost estimates, it also fails to meet the demonstration objective of transparency, something that goes hand in hand with budget neutrality.

The second weakness identified by GAO is that current procedures “may be insufficient to ensure that costs are allowable and matched at the correct rate.” Three of the five states examined in the report had received CMS approval for federal funds for administrative costs that were either not allowable for matching or were matched at higher rates than appropriate, based on CMS guidance.

The government watchdog noted that CMS did implement “procedures that may provide additional information on demonstrations’ administrative costs. ... However, it is unclear whether these efforts will result in data that improves CMS’s oversight.”

The GAO made three recommendations in the report. First, the CMS should require states to submit public projections of administrative costs when seeking approval for demonstration projects. Second, the administrative costs should be a part of the calculation for assessing the budget neutrality of demonstration project applications. Finally, CMS should do a better job assessing the risk that federal funds are being used to cover administrative costs that are not allowable and should improve oversight procedures as needed.

The GAO report included the Department of Health & Human Services’s response to the recommendations. To the first, the agency said that “its experience suggests that demonstration administrative costs will be a relatively small portion of total costs and therefore HHS believes making information about these costs available would provide stakeholders little to no value.”

Similarly, to the second recommendation, HHS countered that the information would provide little to no value given that administrative costs represent a relatively small portion of the total demonstration costs.

To the final recommendation on the need for better risk assessment, HHS said its existing approach “is appropriate for the low level of risk that administrative expenditures represent. ... CMS officials told us that they had not assessed wither current procedures sufficiently address risks posed by administrative costs for work requirements and had no plans to do so.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services needs to be doing a better job overseeing the administrative costs associated with the implementation of work requirements in Medicaid, the Government Accountability Office said in a new report.

The government watchdog found two key weaknesses in CMS’s oversight of the administrative costs of the Medicaid demonstration projects related to work requirements for Medicaid.

First, the GAO report notes that no consideration of the administrative costs of the work requirements is given during the administration of the approval process.

The GAO reports that, of five states’ approvals, the estimated administrative costs range from the low end of $6.1 million for New Hampshire (with 50,000 beneficiaries subject to the work requirement) to $271.6 million for Kentucky (with 620,000 beneficiaries subject to the work requirement). Indiana, with 420,000 beneficiaries subject to work requirements, has an estimated cost of $35.1 million.

A significant portion of Kentucky’s funding was for a the development of a new information technology system to help track work requirements.

“GAO found that CMS does not require states to provide projections of administrative costs when requesting demonstration approvals,” the report states. “Thus, the cost of administering demonstrations, including those with work requirements, is not transparent to the public or included in CMS’s assessment of whether a demonstration is budget neutral – that is, that federal spending will be no higher under the demonstration than it would have been without it.”

The GAO also reported that, by not requiring cost estimates, it also fails to meet the demonstration objective of transparency, something that goes hand in hand with budget neutrality.

The second weakness identified by GAO is that current procedures “may be insufficient to ensure that costs are allowable and matched at the correct rate.” Three of the five states examined in the report had received CMS approval for federal funds for administrative costs that were either not allowable for matching or were matched at higher rates than appropriate, based on CMS guidance.

The government watchdog noted that CMS did implement “procedures that may provide additional information on demonstrations’ administrative costs. ... However, it is unclear whether these efforts will result in data that improves CMS’s oversight.”

The GAO made three recommendations in the report. First, the CMS should require states to submit public projections of administrative costs when seeking approval for demonstration projects. Second, the administrative costs should be a part of the calculation for assessing the budget neutrality of demonstration project applications. Finally, CMS should do a better job assessing the risk that federal funds are being used to cover administrative costs that are not allowable and should improve oversight procedures as needed.

The GAO report included the Department of Health & Human Services’s response to the recommendations. To the first, the agency said that “its experience suggests that demonstration administrative costs will be a relatively small portion of total costs and therefore HHS believes making information about these costs available would provide stakeholders little to no value.”

Similarly, to the second recommendation, HHS countered that the information would provide little to no value given that administrative costs represent a relatively small portion of the total demonstration costs.

To the final recommendation on the need for better risk assessment, HHS said its existing approach “is appropriate for the low level of risk that administrative expenditures represent. ... CMS officials told us that they had not assessed wither current procedures sufficiently address risks posed by administrative costs for work requirements and had no plans to do so.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services needs to be doing a better job overseeing the administrative costs associated with the implementation of work requirements in Medicaid, the Government Accountability Office said in a new report.

The government watchdog found two key weaknesses in CMS’s oversight of the administrative costs of the Medicaid demonstration projects related to work requirements for Medicaid.

First, the GAO report notes that no consideration of the administrative costs of the work requirements is given during the administration of the approval process.

The GAO reports that, of five states’ approvals, the estimated administrative costs range from the low end of $6.1 million for New Hampshire (with 50,000 beneficiaries subject to the work requirement) to $271.6 million for Kentucky (with 620,000 beneficiaries subject to the work requirement). Indiana, with 420,000 beneficiaries subject to work requirements, has an estimated cost of $35.1 million.

A significant portion of Kentucky’s funding was for a the development of a new information technology system to help track work requirements.

“GAO found that CMS does not require states to provide projections of administrative costs when requesting demonstration approvals,” the report states. “Thus, the cost of administering demonstrations, including those with work requirements, is not transparent to the public or included in CMS’s assessment of whether a demonstration is budget neutral – that is, that federal spending will be no higher under the demonstration than it would have been without it.”

The GAO also reported that, by not requiring cost estimates, it also fails to meet the demonstration objective of transparency, something that goes hand in hand with budget neutrality.

The second weakness identified by GAO is that current procedures “may be insufficient to ensure that costs are allowable and matched at the correct rate.” Three of the five states examined in the report had received CMS approval for federal funds for administrative costs that were either not allowable for matching or were matched at higher rates than appropriate, based on CMS guidance.

The government watchdog noted that CMS did implement “procedures that may provide additional information on demonstrations’ administrative costs. ... However, it is unclear whether these efforts will result in data that improves CMS’s oversight.”

The GAO made three recommendations in the report. First, the CMS should require states to submit public projections of administrative costs when seeking approval for demonstration projects. Second, the administrative costs should be a part of the calculation for assessing the budget neutrality of demonstration project applications. Finally, CMS should do a better job assessing the risk that federal funds are being used to cover administrative costs that are not allowable and should improve oversight procedures as needed.

The GAO report included the Department of Health & Human Services’s response to the recommendations. To the first, the agency said that “its experience suggests that demonstration administrative costs will be a relatively small portion of total costs and therefore HHS believes making information about these costs available would provide stakeholders little to no value.”

Similarly, to the second recommendation, HHS countered that the information would provide little to no value given that administrative costs represent a relatively small portion of the total demonstration costs.

To the final recommendation on the need for better risk assessment, HHS said its existing approach “is appropriate for the low level of risk that administrative expenditures represent. ... CMS officials told us that they had not assessed wither current procedures sufficiently address risks posed by administrative costs for work requirements and had no plans to do so.”

November 2019 – ICYMI

Gastroenterology

Pantoprazole to prevent gastroduodenal events in patients receiving rivaroxaban and/or aspirin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Moayyedi P et al. 2019 Aug;157(2):403-12. doi. org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.04.

How to foster academic promotion and career advancement of women in gastroenterology. Zimmermann EM. 2019 Sep;157(3):598-601. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.041.

AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome in adults (IBS-D). Smalley W et al. 2019 Sep;157(3):851-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.004.

Gluten does not induce gastrointestinal symptoms in healthy volunteers: A double-blind randomized placebo trial. Croall ID et al. 2019 Sep;157(3):881-883. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.015.

How to advance research, education, and training in the study of rare diseases. Groft SC et al. 2019 Oct;157(4):917-21. doi. org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.010.

Clip closure prevents bleeding after endoscopic resection of large colon polyps in a randomized trial. Pohl H et al. 2019 Oct;157(4):977-984.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.019.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Fibroscan for the rest of us – How to incorporate Fibroscan into management of patients with liver disease. Sozio MS. 2019 Aug;17(9):1714-7 doi. org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.02.014.

Physician practice management and private equity: Market forces drive change. Gilreath M et al. 2019 Sep;17(10):1924-8.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.001.

Migration of patients for liver transplantation and waitlist outcomes. Kwong AJ et al. 2019 Oct;17(11):2347-55.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.060.

Gastroenterology

Pantoprazole to prevent gastroduodenal events in patients receiving rivaroxaban and/or aspirin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Moayyedi P et al. 2019 Aug;157(2):403-12. doi. org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.04.

How to foster academic promotion and career advancement of women in gastroenterology. Zimmermann EM. 2019 Sep;157(3):598-601. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.041.

AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome in adults (IBS-D). Smalley W et al. 2019 Sep;157(3):851-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.004.

Gluten does not induce gastrointestinal symptoms in healthy volunteers: A double-blind randomized placebo trial. Croall ID et al. 2019 Sep;157(3):881-883. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.015.

How to advance research, education, and training in the study of rare diseases. Groft SC et al. 2019 Oct;157(4):917-21. doi. org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.010.

Clip closure prevents bleeding after endoscopic resection of large colon polyps in a randomized trial. Pohl H et al. 2019 Oct;157(4):977-984.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.019.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Fibroscan for the rest of us – How to incorporate Fibroscan into management of patients with liver disease. Sozio MS. 2019 Aug;17(9):1714-7 doi. org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.02.014.

Physician practice management and private equity: Market forces drive change. Gilreath M et al. 2019 Sep;17(10):1924-8.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.001.

Migration of patients for liver transplantation and waitlist outcomes. Kwong AJ et al. 2019 Oct;17(11):2347-55.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.060.

Gastroenterology

Pantoprazole to prevent gastroduodenal events in patients receiving rivaroxaban and/or aspirin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Moayyedi P et al. 2019 Aug;157(2):403-12. doi. org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.04.

How to foster academic promotion and career advancement of women in gastroenterology. Zimmermann EM. 2019 Sep;157(3):598-601. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.041.

AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome in adults (IBS-D). Smalley W et al. 2019 Sep;157(3):851-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.004.

Gluten does not induce gastrointestinal symptoms in healthy volunteers: A double-blind randomized placebo trial. Croall ID et al. 2019 Sep;157(3):881-883. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.015.

How to advance research, education, and training in the study of rare diseases. Groft SC et al. 2019 Oct;157(4):917-21. doi. org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.010.

Clip closure prevents bleeding after endoscopic resection of large colon polyps in a randomized trial. Pohl H et al. 2019 Oct;157(4):977-984.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.019.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Fibroscan for the rest of us – How to incorporate Fibroscan into management of patients with liver disease. Sozio MS. 2019 Aug;17(9):1714-7 doi. org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.02.014.

Physician practice management and private equity: Market forces drive change. Gilreath M et al. 2019 Sep;17(10):1924-8.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.001.

Migration of patients for liver transplantation and waitlist outcomes. Kwong AJ et al. 2019 Oct;17(11):2347-55.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.060.

Yoga life lessons

I love empty storefronts. The realtor headshot in the window is a sign of hope. What was here is no more. What is coming will be better.

I’ve waited a year for one such sign to come down and scaffolding to go up. Just one block from my condo, my curiosity has been slaked: a yoga studio! At first, disappointment; so many potentials unrealized: a coffee shop, cleaners, speakeasy! Yet, I decided to make the best of it. I bought Rainbow sandals, a Lululemon mat, and a pack of 10 classes. As it turns out, yoga can transform your life.

I didn’t realize how beautifully yoga combines physical exertion, meditation, and spirituality. It is both a model for understanding and a ritualistic training for life. Take resting pigeon for example. (Yogis reading this will forgive my imperfect explanation.) This moderately difficult pose opens your hip and stretches your glutes. Imagine doing a split but with your front knee bent and your forehead and arms resting on the floor in front of you. Done correctly, it puts a stretch deep into the hip of the forward leg. It is uncomfortable. Holding it for a minute or 2 is hard. But rather than just focusing on releasing, with each breath you find yourself deepening the stretch. Sweat streams down your arms and the discomfort builds as you hold. All you can think about is your breath. Then, it’s over. You feel freer, lighter than you were before. The deeper the discomfort, the deeper the delight that arises afterward. You are wise, yogis would say, to have chosen “the good over the pleasant.”

We have many opportunities for resting pigeon in everyday life. The patient to be added to your Monday morning clinic – which already had added patients. The Friday afternoon Mohs case that went to periosteum and still needs a flap to close. The “yet another” GI bleed patient that needs to be scoped tonight. These are all deep stretches, uncomfortable hip openings. Rather, when you must be uncomfortable, breathe and lean into it. Choosing the good sometimes means choosing suffering, but it isn’t the pain that makes it hard to bear. It is a lack of significance for that difficulty. By choosing what is good, you answer the question: “Who am I?” I am the one able and willing to endure inconvenience or disquiet to help others. This is my job, what I’m here to do. The pose, the call, the case will be over quickly. The freedom you feel after, along with the satisfaction you have served your purpose, will sustain you.

There are many poses and endless lessons from yoga. In fact, doing yoga is called “practicing.” Each time you learn and try. Each time you are imperfect and uncomfortable and reemerge sweaty and satisfied, just a little better human than you were before.

Dr. Benabio is director of health care transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

I love empty storefronts. The realtor headshot in the window is a sign of hope. What was here is no more. What is coming will be better.

I’ve waited a year for one such sign to come down and scaffolding to go up. Just one block from my condo, my curiosity has been slaked: a yoga studio! At first, disappointment; so many potentials unrealized: a coffee shop, cleaners, speakeasy! Yet, I decided to make the best of it. I bought Rainbow sandals, a Lululemon mat, and a pack of 10 classes. As it turns out, yoga can transform your life.

I didn’t realize how beautifully yoga combines physical exertion, meditation, and spirituality. It is both a model for understanding and a ritualistic training for life. Take resting pigeon for example. (Yogis reading this will forgive my imperfect explanation.) This moderately difficult pose opens your hip and stretches your glutes. Imagine doing a split but with your front knee bent and your forehead and arms resting on the floor in front of you. Done correctly, it puts a stretch deep into the hip of the forward leg. It is uncomfortable. Holding it for a minute or 2 is hard. But rather than just focusing on releasing, with each breath you find yourself deepening the stretch. Sweat streams down your arms and the discomfort builds as you hold. All you can think about is your breath. Then, it’s over. You feel freer, lighter than you were before. The deeper the discomfort, the deeper the delight that arises afterward. You are wise, yogis would say, to have chosen “the good over the pleasant.”

We have many opportunities for resting pigeon in everyday life. The patient to be added to your Monday morning clinic – which already had added patients. The Friday afternoon Mohs case that went to periosteum and still needs a flap to close. The “yet another” GI bleed patient that needs to be scoped tonight. These are all deep stretches, uncomfortable hip openings. Rather, when you must be uncomfortable, breathe and lean into it. Choosing the good sometimes means choosing suffering, but it isn’t the pain that makes it hard to bear. It is a lack of significance for that difficulty. By choosing what is good, you answer the question: “Who am I?” I am the one able and willing to endure inconvenience or disquiet to help others. This is my job, what I’m here to do. The pose, the call, the case will be over quickly. The freedom you feel after, along with the satisfaction you have served your purpose, will sustain you.

There are many poses and endless lessons from yoga. In fact, doing yoga is called “practicing.” Each time you learn and try. Each time you are imperfect and uncomfortable and reemerge sweaty and satisfied, just a little better human than you were before.

Dr. Benabio is director of health care transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

I love empty storefronts. The realtor headshot in the window is a sign of hope. What was here is no more. What is coming will be better.

I’ve waited a year for one such sign to come down and scaffolding to go up. Just one block from my condo, my curiosity has been slaked: a yoga studio! At first, disappointment; so many potentials unrealized: a coffee shop, cleaners, speakeasy! Yet, I decided to make the best of it. I bought Rainbow sandals, a Lululemon mat, and a pack of 10 classes. As it turns out, yoga can transform your life.

I didn’t realize how beautifully yoga combines physical exertion, meditation, and spirituality. It is both a model for understanding and a ritualistic training for life. Take resting pigeon for example. (Yogis reading this will forgive my imperfect explanation.) This moderately difficult pose opens your hip and stretches your glutes. Imagine doing a split but with your front knee bent and your forehead and arms resting on the floor in front of you. Done correctly, it puts a stretch deep into the hip of the forward leg. It is uncomfortable. Holding it for a minute or 2 is hard. But rather than just focusing on releasing, with each breath you find yourself deepening the stretch. Sweat streams down your arms and the discomfort builds as you hold. All you can think about is your breath. Then, it’s over. You feel freer, lighter than you were before. The deeper the discomfort, the deeper the delight that arises afterward. You are wise, yogis would say, to have chosen “the good over the pleasant.”

We have many opportunities for resting pigeon in everyday life. The patient to be added to your Monday morning clinic – which already had added patients. The Friday afternoon Mohs case that went to periosteum and still needs a flap to close. The “yet another” GI bleed patient that needs to be scoped tonight. These are all deep stretches, uncomfortable hip openings. Rather, when you must be uncomfortable, breathe and lean into it. Choosing the good sometimes means choosing suffering, but it isn’t the pain that makes it hard to bear. It is a lack of significance for that difficulty. By choosing what is good, you answer the question: “Who am I?” I am the one able and willing to endure inconvenience or disquiet to help others. This is my job, what I’m here to do. The pose, the call, the case will be over quickly. The freedom you feel after, along with the satisfaction you have served your purpose, will sustain you.

There are many poses and endless lessons from yoga. In fact, doing yoga is called “practicing.” Each time you learn and try. Each time you are imperfect and uncomfortable and reemerge sweaty and satisfied, just a little better human than you were before.

Dr. Benabio is director of health care transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Low P values shouldn’t always impress you

SAN DIEGO – Even if a P value hints at statistical significance by dipping under .05, it might not tell you anything worthwhile. Effect sizes are hugely important – as long as accompanying P values measure up. And pharmaceutical companies often keep revealing numbers under wraps unless you know what – and whom – to ask.

Those lessons come courtesy of Leslie Citrome, MD, MPH, who spoke to colleagues about study numbers at Psych Congress 2019.

Dr. Citrome, clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at New York Medical College, Valhalla, offered several tips about interpreting medical statistics as you make clinical decisions.

Don’t get hung up on the P value.

The P value helps you understand how likely it is that a difference in a study is statistically significant. In medical research, P values under .05 are considered especially desirable. They suggest that an outcome – drug A performed better than drug B, for example – didn’t happen purely by chance.

Here’s the hitch: The P value might not matter at all. “Clinicians often assume that if the P value is less than.05, the result must be important. But even a P value of less than .05 is meaningless outside of the context of how big the treatment effect is,” Dr. Citrome said. “If a clinical trial result shows us a small effect size, then who cares?”

Understand what effect sizes tell you.

Effect size measurements evaluate clinical impact and include number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH). NNT refers to the number of patients needed to treat with an intervention in order to get a positive effect in one additional patient; NNH is the reverse and examines negative effects that can range from the minor (mild dry mouth) to the devastating (death).

What’s a good size for an NNT? “I respect any NNT versus placebo of less than 10,” Dr. Citrome said. “It’s something I’ll probably consider in day-to-day practice.” Double-digit and triple-digit NNTs “are usually irrelevant unless we’re dealing with very specific outcomes that have long-term consequences.”

As for the opposite side of the picture – NNH – values higher than 10 are ideal.

He cautioned that NNT and NNH, like P values, cannot stand alone. In fact, they work together. In order to have value, NNT or NNH must be statistically significant, and P values provide this crucial insight.

Consider Dr. Citrome’s blood pressure.

As Dr. Citrome noted, research suggests that, among patients with diastolic BP from 90 to 109 mm Hg, 1 additional person will avoid death, stroke, or heart attack for every 141 people who take an antihypertensive medication, compared to those who do not, over a 5-year period. That’s a lot of people taking medication for a long time, with potential side effects, for a fairly small effect size. However, the outcomes are dire, so it is still worth it.

Then there’s Dr. Citrome himself, who has had diastolic BP in the range of 115 to 129 mm Hg. The NNT is 3. For every 3 people who take an antihypertensive vs. not over a 5-year period, 1 additional person will avoid a potentially catastrophic cardiovascular event.

“Guess who’s pretty adherent to taking his antihypertensive medication?” he asked. “I am.”

Ask for effect sizes if you don’t see them.

It’s not unusual for pharmaceutical representatives to avoid providing information about medication effect sizes. “The sales representatives as well as speakers at [Food and Drug Administration]–regulated promotional speaking events can only speak to basically what’s on the label. NNT and NNH are not currently found on product labels. But they are very relevant, and we need to know this information.”

What to do? “There is a workaround here,” he said. “Ask the sales rep to talk to a medical science liaison, who is free to come to your office and talk about all the data that they have.”

Dr. Citrome reported multiple disclosures, including various relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – Even if a P value hints at statistical significance by dipping under .05, it might not tell you anything worthwhile. Effect sizes are hugely important – as long as accompanying P values measure up. And pharmaceutical companies often keep revealing numbers under wraps unless you know what – and whom – to ask.

Those lessons come courtesy of Leslie Citrome, MD, MPH, who spoke to colleagues about study numbers at Psych Congress 2019.

Dr. Citrome, clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at New York Medical College, Valhalla, offered several tips about interpreting medical statistics as you make clinical decisions.

Don’t get hung up on the P value.

The P value helps you understand how likely it is that a difference in a study is statistically significant. In medical research, P values under .05 are considered especially desirable. They suggest that an outcome – drug A performed better than drug B, for example – didn’t happen purely by chance.

Here’s the hitch: The P value might not matter at all. “Clinicians often assume that if the P value is less than.05, the result must be important. But even a P value of less than .05 is meaningless outside of the context of how big the treatment effect is,” Dr. Citrome said. “If a clinical trial result shows us a small effect size, then who cares?”

Understand what effect sizes tell you.

Effect size measurements evaluate clinical impact and include number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH). NNT refers to the number of patients needed to treat with an intervention in order to get a positive effect in one additional patient; NNH is the reverse and examines negative effects that can range from the minor (mild dry mouth) to the devastating (death).

What’s a good size for an NNT? “I respect any NNT versus placebo of less than 10,” Dr. Citrome said. “It’s something I’ll probably consider in day-to-day practice.” Double-digit and triple-digit NNTs “are usually irrelevant unless we’re dealing with very specific outcomes that have long-term consequences.”

As for the opposite side of the picture – NNH – values higher than 10 are ideal.

He cautioned that NNT and NNH, like P values, cannot stand alone. In fact, they work together. In order to have value, NNT or NNH must be statistically significant, and P values provide this crucial insight.

Consider Dr. Citrome’s blood pressure.

As Dr. Citrome noted, research suggests that, among patients with diastolic BP from 90 to 109 mm Hg, 1 additional person will avoid death, stroke, or heart attack for every 141 people who take an antihypertensive medication, compared to those who do not, over a 5-year period. That’s a lot of people taking medication for a long time, with potential side effects, for a fairly small effect size. However, the outcomes are dire, so it is still worth it.

Then there’s Dr. Citrome himself, who has had diastolic BP in the range of 115 to 129 mm Hg. The NNT is 3. For every 3 people who take an antihypertensive vs. not over a 5-year period, 1 additional person will avoid a potentially catastrophic cardiovascular event.

“Guess who’s pretty adherent to taking his antihypertensive medication?” he asked. “I am.”

Ask for effect sizes if you don’t see them.

It’s not unusual for pharmaceutical representatives to avoid providing information about medication effect sizes. “The sales representatives as well as speakers at [Food and Drug Administration]–regulated promotional speaking events can only speak to basically what’s on the label. NNT and NNH are not currently found on product labels. But they are very relevant, and we need to know this information.”

What to do? “There is a workaround here,” he said. “Ask the sales rep to talk to a medical science liaison, who is free to come to your office and talk about all the data that they have.”

Dr. Citrome reported multiple disclosures, including various relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – Even if a P value hints at statistical significance by dipping under .05, it might not tell you anything worthwhile. Effect sizes are hugely important – as long as accompanying P values measure up. And pharmaceutical companies often keep revealing numbers under wraps unless you know what – and whom – to ask.

Those lessons come courtesy of Leslie Citrome, MD, MPH, who spoke to colleagues about study numbers at Psych Congress 2019.

Dr. Citrome, clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at New York Medical College, Valhalla, offered several tips about interpreting medical statistics as you make clinical decisions.

Don’t get hung up on the P value.

The P value helps you understand how likely it is that a difference in a study is statistically significant. In medical research, P values under .05 are considered especially desirable. They suggest that an outcome – drug A performed better than drug B, for example – didn’t happen purely by chance.

Here’s the hitch: The P value might not matter at all. “Clinicians often assume that if the P value is less than.05, the result must be important. But even a P value of less than .05 is meaningless outside of the context of how big the treatment effect is,” Dr. Citrome said. “If a clinical trial result shows us a small effect size, then who cares?”

Understand what effect sizes tell you.

Effect size measurements evaluate clinical impact and include number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH). NNT refers to the number of patients needed to treat with an intervention in order to get a positive effect in one additional patient; NNH is the reverse and examines negative effects that can range from the minor (mild dry mouth) to the devastating (death).

What’s a good size for an NNT? “I respect any NNT versus placebo of less than 10,” Dr. Citrome said. “It’s something I’ll probably consider in day-to-day practice.” Double-digit and triple-digit NNTs “are usually irrelevant unless we’re dealing with very specific outcomes that have long-term consequences.”

As for the opposite side of the picture – NNH – values higher than 10 are ideal.

He cautioned that NNT and NNH, like P values, cannot stand alone. In fact, they work together. In order to have value, NNT or NNH must be statistically significant, and P values provide this crucial insight.

Consider Dr. Citrome’s blood pressure.

As Dr. Citrome noted, research suggests that, among patients with diastolic BP from 90 to 109 mm Hg, 1 additional person will avoid death, stroke, or heart attack for every 141 people who take an antihypertensive medication, compared to those who do not, over a 5-year period. That’s a lot of people taking medication for a long time, with potential side effects, for a fairly small effect size. However, the outcomes are dire, so it is still worth it.

Then there’s Dr. Citrome himself, who has had diastolic BP in the range of 115 to 129 mm Hg. The NNT is 3. For every 3 people who take an antihypertensive vs. not over a 5-year period, 1 additional person will avoid a potentially catastrophic cardiovascular event.

“Guess who’s pretty adherent to taking his antihypertensive medication?” he asked. “I am.”

Ask for effect sizes if you don’t see them.

It’s not unusual for pharmaceutical representatives to avoid providing information about medication effect sizes. “The sales representatives as well as speakers at [Food and Drug Administration]–regulated promotional speaking events can only speak to basically what’s on the label. NNT and NNH are not currently found on product labels. But they are very relevant, and we need to know this information.”

What to do? “There is a workaround here,” he said. “Ask the sales rep to talk to a medical science liaison, who is free to come to your office and talk about all the data that they have.”

Dr. Citrome reported multiple disclosures, including various relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM PSYCH CONGRESS 2019

Policymakers must invest in health care innovation

Affordable pharma tops consumer list

In 2017, the United States spent $3.5 trillion on health care, and that number is projected to be close 20% of our GDP over the next 10 years. For consumers, prescription drugs feel like the biggest contributor.

“Although pharmaceutical spending accounts for less than 10% of health care spending, consumers bear much more of the out-of-pocket cost of the prescription drugs through copays or coinsurance at the pharmacy counter than they pay for hospital or physician costs,” said Tanisha Carino, PhD, author of a Health Affairs blog post about directions for innovation in health care. “This experience has led to rising concerns among Americans about the cost of prescription drugs.”

In fact, a December 2018 Politico-Harvard poll showed Americans from both political parties overwhelmingly agreed that taking action to lower drug prices should have been the top priority of the new Congress that took office in January of this year.

“Addressing the affordability of prescription drugs will require investing in medical research and policies that speed new products to the market that will promote competition and, hopefully, will hold down prices and offer greater choice to patients,” said Dr. Carino, who is executive director of FasterCures, a center of the Milken Institute devoted to improving the biomedical innovation ecosystem. “Policymakers have an opportunity to address the immediate concerns patients have in affording their medication.”

According to Dr. Carino, policymakers can also continue to encourage health-improving medical innovation through the following:

- Boosting investment in research and development.

- Increasing safety and coordination of health data for biomedical research.

- Incentivizing innovation in underinvested areas.

- Building the capacity of patient organizations.

Hospitalists, she added, will play a critical role in participating in the clinical research that will lead to the next generation of treatments.

Reference

1. Carino T. “To get more bang for your health-care buck, invest in innovation.” Health Affairs Blog. 2019 Jan 24. doi: 10.1377/hblog20190123.483080. Accessed Feb. 6, 2019.

Affordable pharma tops consumer list

Affordable pharma tops consumer list

In 2017, the United States spent $3.5 trillion on health care, and that number is projected to be close 20% of our GDP over the next 10 years. For consumers, prescription drugs feel like the biggest contributor.

“Although pharmaceutical spending accounts for less than 10% of health care spending, consumers bear much more of the out-of-pocket cost of the prescription drugs through copays or coinsurance at the pharmacy counter than they pay for hospital or physician costs,” said Tanisha Carino, PhD, author of a Health Affairs blog post about directions for innovation in health care. “This experience has led to rising concerns among Americans about the cost of prescription drugs.”

In fact, a December 2018 Politico-Harvard poll showed Americans from both political parties overwhelmingly agreed that taking action to lower drug prices should have been the top priority of the new Congress that took office in January of this year.

“Addressing the affordability of prescription drugs will require investing in medical research and policies that speed new products to the market that will promote competition and, hopefully, will hold down prices and offer greater choice to patients,” said Dr. Carino, who is executive director of FasterCures, a center of the Milken Institute devoted to improving the biomedical innovation ecosystem. “Policymakers have an opportunity to address the immediate concerns patients have in affording their medication.”

According to Dr. Carino, policymakers can also continue to encourage health-improving medical innovation through the following:

- Boosting investment in research and development.

- Increasing safety and coordination of health data for biomedical research.

- Incentivizing innovation in underinvested areas.

- Building the capacity of patient organizations.

Hospitalists, she added, will play a critical role in participating in the clinical research that will lead to the next generation of treatments.

Reference

1. Carino T. “To get more bang for your health-care buck, invest in innovation.” Health Affairs Blog. 2019 Jan 24. doi: 10.1377/hblog20190123.483080. Accessed Feb. 6, 2019.

In 2017, the United States spent $3.5 trillion on health care, and that number is projected to be close 20% of our GDP over the next 10 years. For consumers, prescription drugs feel like the biggest contributor.

“Although pharmaceutical spending accounts for less than 10% of health care spending, consumers bear much more of the out-of-pocket cost of the prescription drugs through copays or coinsurance at the pharmacy counter than they pay for hospital or physician costs,” said Tanisha Carino, PhD, author of a Health Affairs blog post about directions for innovation in health care. “This experience has led to rising concerns among Americans about the cost of prescription drugs.”

In fact, a December 2018 Politico-Harvard poll showed Americans from both political parties overwhelmingly agreed that taking action to lower drug prices should have been the top priority of the new Congress that took office in January of this year.

“Addressing the affordability of prescription drugs will require investing in medical research and policies that speed new products to the market that will promote competition and, hopefully, will hold down prices and offer greater choice to patients,” said Dr. Carino, who is executive director of FasterCures, a center of the Milken Institute devoted to improving the biomedical innovation ecosystem. “Policymakers have an opportunity to address the immediate concerns patients have in affording their medication.”

According to Dr. Carino, policymakers can also continue to encourage health-improving medical innovation through the following:

- Boosting investment in research and development.

- Increasing safety and coordination of health data for biomedical research.

- Incentivizing innovation in underinvested areas.

- Building the capacity of patient organizations.

Hospitalists, she added, will play a critical role in participating in the clinical research that will lead to the next generation of treatments.

Reference