User login

For MD-IQ use only

Experience With Adaptive Servo-Ventilation Among Veterans in the Post-SERVE-HF Era

Sleep apnea is a heterogeneous group of conditions that may be attributable to a wide array of underlying conditions, with varying contributions of obstructive or central sleep-disordered breathing. The spectrum from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) to central sleep apnea (CSA) includes mixed sleep apnea, treatment-emergent CSA (TECSA), and Cheyne-Stokes respiration (CSR).1 The pathophysiologic causes of CSA can be attributed to delayed cardiopulmonary circulation in heart failure, decreased brainstem ventilatory response due to stroke, blunting of central chemoreceptors in chronic opioid use, and/or stimulation of the Hering-Breuer reflex from activation of pulmonary stretch receptors after initiating positive airway pressure (PAP) for treatment of OSA.2,3 Medications are commonly implicated in many forms of sleep-disordered breathing; importantly, opioids and benzodiazepines may blunt the respiratory drive, leading to CSA, and/or impair upper airway patency, resulting in or worsening OSA.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is largely ineffective in correcting CSA or improving outcomes and is often poorly tolerated in these patients.4 Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is a form of bilevel PAP (BPAP) therapy that delivers variable adjusting pressure support, primarily to treat CSA. PAP also may relieve upper airway obstructions, thereby effectively treating any comorbid obstructive component. ASV has been well documented to improve sleep-related disorders and improve apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) in patients with CSA. However, longitudinal data have demonstrated increased mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) who were treated with ASV.5 Since the SERVE-HF trial results came to light in 2015, there has been no consensus regarding the optimal use, if any, of ASV therapy.6-8 This is partly related to the inability to fully explain the study’s major findings, which were unexpected at the time, and partly due to the absence of similar relevant mortality data in patients with CSA but without HFrEF.

TECSA may present in some patients with OSA who are new to PAP therapy. These events are frequently seen during PAP titration sleep studies, though patients can also experience significant TECSA shortly after initiating home PAP therapy. TECSA is felt to result from a combination of stimulating pulmonary stretch receptors and lowering arterial carbon dioxide below the apneic threshold. Chemoreceptors located in the medulla respond by attenuating the respiratory drive.9 Previous studies have shown most cases of mild TECSA resolve over time with CPAP treatment. However, in patients with persistent or worsening TECSA, ASV may be considered as an alternative to CPAP.

The prevalence of OSA in the veteran population is estimated to be as high as 60%, considerably higher than the general population estimation.10 Patients with more significant comorbidities may also experience a higher frequency of central events. Patients with CSA have also been shown to have a higher risk for cardiac-related hospital admissions, providing plausible justification for correcting CSA.10

In the current study, we aim to characterize the group of patients using ASV therapy in the modern era. We will assess the objective efficacy and adherence of ASV therapy in patients with primarily CSA compared with those having primarily OSA (ie, TECSA). Secondarily, we aim to identify baseline clinical and polysomnographic features that may be predictive of ASV adherence, as a surrogate for subjective benefit.11 In the wake of the SERVE-HF study, the sleep medicine community has paused prescribing ASV therapy for CSA. We hope to provide more perspective on the treatment of veterans with CSA and identify the patient groups that would benefit most from ASV therapy.

Methods

This retrospective chart review examined patients prescribed ASV therapy at the Hampton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (HVAMC) in Virginia who had therapy data between January 1, 2015, and April 30, 2020. The start date was chosen to approximate the phase-in of wireless PAP devices at HVAMC and to correspond with the release of preliminary results from the SERVE-HF trial.

Patients were initially identified through a query into commercial wireless PAP management databases and cross-referenced with HVAMC patients. Adherence and efficacy data were obtained from the most recent clinical PAP data, which allowed for the evaluation of patients who discontinued therapy for reasons other than intolerance. Clinical, demographic, and polysomnography (PSG) data were obtained from the electronic health record. One patient, identified through the database query but not found in the electronic health record, was excluded. In cases of missing PSG data, especially AHI or similar values, all attempts were made to calculate the data with other provided values. This study was determined to be exempt by the HVAMC Institutional Review Board (protocol #20-01).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were designed to compare clinical characteristics and adherence to therapy of those with primarily CSA on PSG and those with primarily OSA. Because it was not currently known how many patients would fit into each of these categories, we also planned secondary comparisons of the clinical and PSG characteristics of those patients who were adherent with therapy and those who were not. Adherence with ASV therapy was defined as device use for ≥ 4 hours for ≥ 70% of nights.

Comparisons between the means of 2 normally distributed groups were performed with an unpaired t test. Comparisons between 2 nonnormally distributed groups and groups of dates were done with the Mann-Whitney U test. The normality of a group distribution was determined using D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Two groups of dichotomous variables were compared with the Fisher exact test. P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

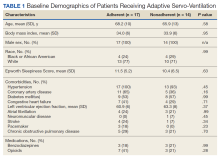

Thirty-one patients were prescribed ASV therapy and had follow-up at HVAMC since 2015. All patients were male. The mean (SD) age was 67.2 (11.4) years, mean body mass index (BMI) was 34.0 (5.9), and the mean (SD) Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score was 10.9 (5.8). Patient comorbidities included 30 (97%) with hypertension, 17 (55%) with diabetes mellitus, 16 (52%) with coronary artery disease, and 11 (35%) with congestive heart failure. Three patients had no echocardiogram or other documentation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). One of these patients had voluntarily stopped using PAP therapy, another had been erroneously started on ASV (ordered for fixed BPAP), and the third had since been retitrated to CPAP. In the 28 patients with documented LVEF, the mean (SD) LVEF was 61.8% (6.9). Ten patients (32%) had opioids documented on their medication lists and 6 (19%) had benzodiazepines.

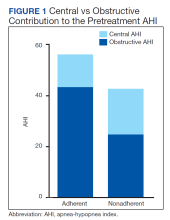

The median date of diagnostic sleep testing was January 9, 2015, and testing was completed after the release of the initial field safety notice regarding the SERVE-HF trial preliminary findings May 13, 2015, for 14 patients (45%).12 On diagnostic sleep testing, the mean (SD) AHI was 47.3 (25.6) events/h and the median (IQR) oxygen saturation (SpO2) nadir was 82% (78-84). Three patients (10%) were initially diagnosed with CSA, 19 (61%) with OSA, and 9 (29%) with both. Sixteen patients (52%) had ASV with fixed expiratory PAP (EPAP), and 15 (48%) had variable adjusting EPAP. Mean (SD) usage of ASV was 6.5 (2.6) hours and 66.0% (34.2) of nights for ≥ 4 hours. Mean (SD) titrated EPAP (set or 90th/95th percentile autotitrated) was 10.1 (3.4) cm H2O and inspiratory PAP (IPAP) (90th/95th percentile) was 17.1 (3.3) cm H2O. The median (IQR) residual AHI on ASV was 2.7 events/h (1.1-5.1), apnea index (AI) was 0.4 (0.1-1.0), and hypopnea index (HI) was 1.4 (1.0-3.2); the residual central and obstructive events were not available in most cases.

Adherence

There were no significant differences between the proportions of patients on ASV with set EPAP or the titrated EPAP and IPAP. The median (IQR) residual AHI was lower in the adherent group compared with the nonadherent group, both in absolute values (1.7 [0.9-3.2] events/h vs 4.7 [2.4-10.3] events/h, respectively [P = .004]), and as a percentage of the pretreatment AHI (3.1% [2.5-6.0] vs 10.2% [5.3-34.4], respectively; P = .002) (Figure 2).

Primarily Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea was a mixed picture of obstructive and central events in many patients. Only 3 patients had “pure” CSA. Thus, we were unable to define discrete comparison groups based on the sleep-disordered breathing phenotype. We identified 19 patients with primarily OSA (ie, initially diagnosed with OSA, OSA with TECSA, or complex sleep apnea). The mean (SD) age was 66.1 (12.8) years, BMI was 36.2 (4.7), and ESS was 11.4 (5.6). The mean (SD) baseline AHI was 46.9 (29.5), obstructive AHI was 40.5 (30.4), and central AHI was 0.4 (1.2); the median (IQR) SpO2 nadir was 81% (78%-84%). The mean (SD) titrated EPAP was 10.2 (3.5) cm H2O, and the 90th/95th percentile IPAP was 17.9 (3.5) cm H2O. The mean (SD) usage of ASV was 7.9 (5.3) hours with 11 patients (58%) meeting the minimum standard for adherence to ASV therapy.

No significant differences were seen between the adherent and nonadherent groups in clinical or demographic characteristics or date of diagnostic sleep testing (eAppendix, available online at doi:10.12788/fp.0374). In baseline sleep studies the mean (SD) HI was 32.3 (15.8) in the adherent group compared with 14.7 (8.8) in the nonadherent group (P = .049). In contrast, obstructive AHI was not significantly lower in the adherent group: 51.9 (30.9) in the adherent group compared with 22.2 (20.6) in the nonadherent group (P = .09). The median (IQR) residual AHI on ASV as a percentage of the pretreatment AHI was 3.0% (2.4%-6.5%) in the adherent group compared with 11.3% (5.4%-89.1%) in the nonadherent group, a statistically significant difference (P = .01). No other significant differences were seen between the groups.

Discussion

This study describes a real-world cohort of patients using ASV therapy and the characteristics associated with benefit from therapy. The patients that were prescribed and started ASV therapy most often had a significant degree of obstructive component to sleep-disordered breathing, whether primary OSA with TECSA or comorbid OSA and CSA. Moreover, we found that a higher obstructive AHI on the baseline PSG was associated with adherence to ASV therapy. Another important finding was that a lower residual AHI on ASV as a proportion of the baseline was associated with PAP adherence. Adherent patients had similar clinical characteristics as the nonadherent patients, including comorbidities, severity of sleep-disordered breathing, and obesity.

Though the results of the SERVE-HF trial have dampened the enthusiasm somewhat, ASV therapy has long been considered an effective and well-tolerated treatment for many types of CSA.13 In fact, treatments that can eliminate the central AHI are fairly limited.4,14 Our data suggest that ASV is also effective and tolerated in OSA with TECSA and/or comorbid CSA. Recent studies suggest that CSA resolves spontaneously in a majority of TECSA patients within 2 to 3 months of regular CPAP use.15 Other estimates suggest that persistent TESCA may be present in 2% of patients with OSA on treatment.16

Given the high and rising prevalence of OSA, many people are at risk for clinically significant TESCA. Another retrospective case series found that 72% of patients that failed treatment with CPAP or BPAP during PSG, met diagnostic criteria (at the time) for CSA; ASV was objectively beneficial in these patients.17 ASV can be an especially useful modality to treat OSA in patients with CSA that either prevents tolerance of standard therapies or causes clinical consequences, presuming the patient does not also have HFrEF.18 The long-term outcomes of treatment with ASV therapy remain a matter of debate.

The SERVE-HF trial remains among the only studies that have assessed the mortality effects of CSA treatments, with unfavorable findings. Treatment of OSA has been associated with favorable chronic health benefits, though recent studies have questioned the degree of benefit attributable to OSA treatment.19-24 Similar studies have not been done for comorbidities represented by our study cohort (ie, OSA with TECSA and/or comorbid CSA).

The lack of CSA diagnosis alone in our cohort may be partially attributable to changing practice patterns following the SERVE-HF trial, though it is not clear from these data why a higher baseline obstructive AHI was associated with adherence to ASV therapy. Our data in this regard are somewhat at odds with the preliminary results of the ADVENT-HF trial. In that study, adherence to ASV therapy in patients with predominantly OSA declined significantly more than in patients with predominantly CSA.25 Most of our patients were diagnosed with predominantly OSA, so a direct comparison with the CSA group is problematic; additionally, the primary brand and the pressure adjustments algorithm used in our study differed from the ADVENT-HF trial.

OSA and CSA may present with similar clinical symptoms, including sleep fragmentation, insomnia, and excessive daytime sleepiness; however, the degree of symptomatology, especially daytime sleepiness, and the response to treatment, may be less in CSA.2,26 Both the subjective report of symptoms (ESS) and PSG measures of sleep fragmentation were similar in our patients, again likely explained by the predominance of obstructive events.

The pathophysiology of CSA is more varied than OSA, which is probably relevant in this case. ASV was originally designed for the management of CSA with CSR, accomplishing this goal by stabilizing the periods of central apnea and hyperpnea characteristic of CSR.27 Although other forms of CSA demonstrate breathing patterns distinct from CSR, ASV has become an accepted treatment for most of these. It is plausible that the long-term subjective benefit and tolerance of ASV in CSA without CSR is less than for CSA with CSR or OSA. None of the patients in our study had CSA with CSR.

Ultimately, it may be the objective treatment effect that lends to adherence, as has been shown previously in OSA patients; our group of adherent patients showed a greater improvement in AHI, relative to baseline, than the nonadherent patients did.28 The technology behind ASV therapy can greatly reduce the frequencies of central apneas, yet this same treatment effectively splints the upper airway and even more effectively eliminates obstructive apneas and hypopneas. Variable adjusting EPAP devices would plausibly provide even more benefit in these patients, as has been shown in prior studies.29 To the contrary, our small sample of patients with TESCA showed a nonsignificant trend toward adherence with fixed EPAP ASV.

Opioid use was substantial in our population, without significant differences between the groups. CPAP therapy is ineffective in improving opioid-associated CSA. In a recent study, 20 patients on opioid therapy with CSA were treated with CPAP therapy; after several weeks, the average therapeutic use was 4 to 5 hours per night and CPAP was abandoned in favor of ASV therapy due to persistent central apnea. ASV treatment was associated with a considerable reduction in central apnea index, AHI, arousal index, and oxygen desaturations in a remarkable improvement over CPAP.30

Limitations and Future Directions

This retrospective, single-center study may have limited applicability to other populations. Adherence was used as a surrogate for subjective benefit from treatment, though benefit was not confirmed by the patients directly. Only patients seen in follow-up for documentation of the ASV download were identified for inclusion and data analysis. As a single center, we risk homogeneity in the treatment algorithms, though sleep medicine treatments are often decided at the time of the sleep studies. Studies and treatment recommendations were made at a variety of sites, including our sleep center, other US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, in the community network, and at US Department of Defense centers. Our population was homogenous in some ways; notably, 100% of our group was male, which is substantially higher than both the veteran population and the general population. Risk factors for OSA and CSA are more common in male patients, which may partially explain this anomaly. Lastly, with our small sample size, there is increased risk that the results seen occurred by chance.

There are several areas for further study. A larger multicenter study may permit these results to be generalized to the population and should include subjective measures of benefit. Patients with primarily CSA were largely absent in our group and may be the focus of future studies; data on predictors of treatment adherence in CSA are lacking. With the availability of consistent older adherence data, comparisons may be made between the efficacies of clinical practice habits, including treatment efficacy, before and after the results of the SERVE-HF trial became known.

Conclusions

In selected patients with preserved LVEF, ASV therapy appears especially effective in patients with OSA combined with CSA. Adherence to ASV treatment was associated with higher obstructive AHI during the baseline PSG and with a greater reduction in the AHI. This understanding may help guide sleep specialists in personalizing treatments for sleep-disordered breathing. Because objective efficacy appears to be important for therapy adherence, clinicians should be able to consistently determine the obstructive and central components of the residual AHI, thus taking all information into account when optimizing the treatment. Additionally, both OSA and CSA pressure requirements should be considered when developing ASV devices.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martha Harper, RRT, of Hampton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (HVAMC) for helping to identify our patients and assisting with data collection. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of HVAMC facilities.

1. Morgenthaler TI, Gay PC, Gordon N, Brown LK. Adaptive servoventilation versus noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for central, mixed, and complex sleep apnea syndromes. Sleep. 2007;30(4):468-475. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.4.468

2. Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Merchia P, Malhotra A. Central sleep apnea: pathophysiology and treatment. Chest. 2007;131(2):595-607. doi:10.1378/chest.06.2287

3. Verbraecken J. Complex sleep apnoea syndrome. Breathe. 2013;9(5):372-380. doi:10.1183/20734735.042412

4. Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2025-2033. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051001

5. Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnea in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506459

6. Imamura T, Kinugawa K. What is the optimal strategy for adaptive servo-ventilation therapy? Int Heart J. 2018;59(4):683-688. doi:10.1536/ihj.17-429

7. Javaheri S, Brown LK, Randerath W, Khayat R. SERVE-HF: more questions than answers. Chest. 2016;149(4):900-904. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.021

8. Mehra R, Gottlieb DJ. A paradigm shift in the treatment of central sleep apnea in heart failure. Chest. 2015;148(4):848-851. doi:10.1378/chest.15-1536

9. Nigam G, Riaz M, Chang E, Camacho M. Natural history of treatment-emergent central sleep apnea on positive airway pressure: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Med. 2018;13(2):86-91. doi:10.4103/atm.ATM_321_17

10. Ratz D, Wiitala W, Badr MS, Burns J, Chowdhuri S. Correlates and consequences of central sleep apnea in a national sample of US veterans. Sleep. 2018;41(9):zsy058. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsy058

11. Wolkove N, Baltzan M, Kamel H, Dabrusin R, Palayew M. Long-term compliance with continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Can Respir J. 2008;15(7):365-369. doi:10.1155/2008/534372

12. Special Safety Notice: ASV therapy for central sleep apnea patients with heart failure. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. May 15, 2015. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://aasm.org/special-safety-notice-asv-therapy-for-central-sleep-apnea-patients-with-heart-failure/

13. Philippe C, Stoïca-Herman M, Drouot X, et al. Compliance with and effectiveness of adaptive servoventilation versus continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure over a six month period. Heart. 2006;92(3):337-342. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.060038

14. Randerath W, Deleanu OC, Schiza S, Pepin J-L. Central sleep apnoea and periodic breathing in heart failure: prognostic significance and treatment options. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(153):190084. Published 2019 Oct 11. doi:10.1183/16000617.0084-2019

15. Gay PC. Complex sleep apnea: it really is a disease. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(5):403-405.

16. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders - Third Edition (ICSD-3). 3rd ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

17. Brown SE, Mosko SS, Davis JA, Pierce RA, Godfrey-Pixton TV. A retrospective case series of adaptive servoventilation for complex sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(2):187-195.

18. Aurora RN, Bista SR, Casey KR, et al. Updated Adaptive Servo-Ventilation Recommendations for the 2012 AASM Guideline: “The Treatment of Central Sleep Apnea Syndromes in Adults: Practice Parameters with an Evidence-Based Literature Review and Meta-Analyses”. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(5):757-761. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5812

19. Martínez-García MA, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Ejarque-Martínez L, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment reduces mortality in patients with ischemic stroke and obstructive sleep apnea: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):36-41. doi:10.1164/rccm.200808-1341OC

20. Martínez-García MA, Campos-Rodríguez F, Catalán-Serra P, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnea in the elderly: role of long-term continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a prospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(9):909-916. doi:10.1164/rccm.201203-0448OC

21. Neilan TG, Farhad H, Dodson JA, et al. Effect of sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac structure and recurrence of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6):e000421. Published 2013 Nov 25. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000421

22. Redline S, Adams N, Strauss ME, Roebuck T, Winters M, Rosenberg C. Improvement of mild sleep-disordered breathing with CPAP compared with conservative therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(3):858-865. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9709042

23. McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, et al. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):919-931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1606599

24. Yu J, Zhou Z, McEvoy RD, et al. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318(2):156-166. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7967

25. Perger E, Lyons OD, Inami T, et al. Predictors of 1-year compliance with adaptive servoventilation in patients with heart failure and sleep disordered breathing: preliminary data from the ADVENT-HF trial. Eur Resp J. 2019;53(2):1801626. doi:10.1183/13993003.01626-2018

26. Lyons OD, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al. Design of the effect of adaptive servo-ventilation on survival and cardiovascular hospital admissions in patients with heart failure and sleep apnoea: the ADVENT-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(4):579-587. doi:10.1002/ejhf.790

27. Teschler H, Döhring J, Wang YM, Berthon-Jones M. Adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation: a novel treatment for Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(4):614-619. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.9908114

28. Ye L, Pack AI, Maislin G, et al. Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure use during the first week of treatment. J Sleep Res. 2012;21(4):419-426. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00969.x

29. Vennelle M, White S, Riha RL, Mackay TW, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Randomized controlled trial of variable-pressure versus fixed-pressure continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment for patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS). Sleep. 2010;33(2):267-271. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.2.267

30. Javaheri S, Harris N, Howard J, Chung E. Adaptive servoventilation for treatment of opioid-associated central sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):637-643. Published 2014 Jun 15. doi:10.5664/jcsm.3788

Sleep apnea is a heterogeneous group of conditions that may be attributable to a wide array of underlying conditions, with varying contributions of obstructive or central sleep-disordered breathing. The spectrum from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) to central sleep apnea (CSA) includes mixed sleep apnea, treatment-emergent CSA (TECSA), and Cheyne-Stokes respiration (CSR).1 The pathophysiologic causes of CSA can be attributed to delayed cardiopulmonary circulation in heart failure, decreased brainstem ventilatory response due to stroke, blunting of central chemoreceptors in chronic opioid use, and/or stimulation of the Hering-Breuer reflex from activation of pulmonary stretch receptors after initiating positive airway pressure (PAP) for treatment of OSA.2,3 Medications are commonly implicated in many forms of sleep-disordered breathing; importantly, opioids and benzodiazepines may blunt the respiratory drive, leading to CSA, and/or impair upper airway patency, resulting in or worsening OSA.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is largely ineffective in correcting CSA or improving outcomes and is often poorly tolerated in these patients.4 Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is a form of bilevel PAP (BPAP) therapy that delivers variable adjusting pressure support, primarily to treat CSA. PAP also may relieve upper airway obstructions, thereby effectively treating any comorbid obstructive component. ASV has been well documented to improve sleep-related disorders and improve apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) in patients with CSA. However, longitudinal data have demonstrated increased mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) who were treated with ASV.5 Since the SERVE-HF trial results came to light in 2015, there has been no consensus regarding the optimal use, if any, of ASV therapy.6-8 This is partly related to the inability to fully explain the study’s major findings, which were unexpected at the time, and partly due to the absence of similar relevant mortality data in patients with CSA but without HFrEF.

TECSA may present in some patients with OSA who are new to PAP therapy. These events are frequently seen during PAP titration sleep studies, though patients can also experience significant TECSA shortly after initiating home PAP therapy. TECSA is felt to result from a combination of stimulating pulmonary stretch receptors and lowering arterial carbon dioxide below the apneic threshold. Chemoreceptors located in the medulla respond by attenuating the respiratory drive.9 Previous studies have shown most cases of mild TECSA resolve over time with CPAP treatment. However, in patients with persistent or worsening TECSA, ASV may be considered as an alternative to CPAP.

The prevalence of OSA in the veteran population is estimated to be as high as 60%, considerably higher than the general population estimation.10 Patients with more significant comorbidities may also experience a higher frequency of central events. Patients with CSA have also been shown to have a higher risk for cardiac-related hospital admissions, providing plausible justification for correcting CSA.10

In the current study, we aim to characterize the group of patients using ASV therapy in the modern era. We will assess the objective efficacy and adherence of ASV therapy in patients with primarily CSA compared with those having primarily OSA (ie, TECSA). Secondarily, we aim to identify baseline clinical and polysomnographic features that may be predictive of ASV adherence, as a surrogate for subjective benefit.11 In the wake of the SERVE-HF study, the sleep medicine community has paused prescribing ASV therapy for CSA. We hope to provide more perspective on the treatment of veterans with CSA and identify the patient groups that would benefit most from ASV therapy.

Methods

This retrospective chart review examined patients prescribed ASV therapy at the Hampton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (HVAMC) in Virginia who had therapy data between January 1, 2015, and April 30, 2020. The start date was chosen to approximate the phase-in of wireless PAP devices at HVAMC and to correspond with the release of preliminary results from the SERVE-HF trial.

Patients were initially identified through a query into commercial wireless PAP management databases and cross-referenced with HVAMC patients. Adherence and efficacy data were obtained from the most recent clinical PAP data, which allowed for the evaluation of patients who discontinued therapy for reasons other than intolerance. Clinical, demographic, and polysomnography (PSG) data were obtained from the electronic health record. One patient, identified through the database query but not found in the electronic health record, was excluded. In cases of missing PSG data, especially AHI or similar values, all attempts were made to calculate the data with other provided values. This study was determined to be exempt by the HVAMC Institutional Review Board (protocol #20-01).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were designed to compare clinical characteristics and adherence to therapy of those with primarily CSA on PSG and those with primarily OSA. Because it was not currently known how many patients would fit into each of these categories, we also planned secondary comparisons of the clinical and PSG characteristics of those patients who were adherent with therapy and those who were not. Adherence with ASV therapy was defined as device use for ≥ 4 hours for ≥ 70% of nights.

Comparisons between the means of 2 normally distributed groups were performed with an unpaired t test. Comparisons between 2 nonnormally distributed groups and groups of dates were done with the Mann-Whitney U test. The normality of a group distribution was determined using D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Two groups of dichotomous variables were compared with the Fisher exact test. P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Thirty-one patients were prescribed ASV therapy and had follow-up at HVAMC since 2015. All patients were male. The mean (SD) age was 67.2 (11.4) years, mean body mass index (BMI) was 34.0 (5.9), and the mean (SD) Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score was 10.9 (5.8). Patient comorbidities included 30 (97%) with hypertension, 17 (55%) with diabetes mellitus, 16 (52%) with coronary artery disease, and 11 (35%) with congestive heart failure. Three patients had no echocardiogram or other documentation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). One of these patients had voluntarily stopped using PAP therapy, another had been erroneously started on ASV (ordered for fixed BPAP), and the third had since been retitrated to CPAP. In the 28 patients with documented LVEF, the mean (SD) LVEF was 61.8% (6.9). Ten patients (32%) had opioids documented on their medication lists and 6 (19%) had benzodiazepines.

The median date of diagnostic sleep testing was January 9, 2015, and testing was completed after the release of the initial field safety notice regarding the SERVE-HF trial preliminary findings May 13, 2015, for 14 patients (45%).12 On diagnostic sleep testing, the mean (SD) AHI was 47.3 (25.6) events/h and the median (IQR) oxygen saturation (SpO2) nadir was 82% (78-84). Three patients (10%) were initially diagnosed with CSA, 19 (61%) with OSA, and 9 (29%) with both. Sixteen patients (52%) had ASV with fixed expiratory PAP (EPAP), and 15 (48%) had variable adjusting EPAP. Mean (SD) usage of ASV was 6.5 (2.6) hours and 66.0% (34.2) of nights for ≥ 4 hours. Mean (SD) titrated EPAP (set or 90th/95th percentile autotitrated) was 10.1 (3.4) cm H2O and inspiratory PAP (IPAP) (90th/95th percentile) was 17.1 (3.3) cm H2O. The median (IQR) residual AHI on ASV was 2.7 events/h (1.1-5.1), apnea index (AI) was 0.4 (0.1-1.0), and hypopnea index (HI) was 1.4 (1.0-3.2); the residual central and obstructive events were not available in most cases.

Adherence

There were no significant differences between the proportions of patients on ASV with set EPAP or the titrated EPAP and IPAP. The median (IQR) residual AHI was lower in the adherent group compared with the nonadherent group, both in absolute values (1.7 [0.9-3.2] events/h vs 4.7 [2.4-10.3] events/h, respectively [P = .004]), and as a percentage of the pretreatment AHI (3.1% [2.5-6.0] vs 10.2% [5.3-34.4], respectively; P = .002) (Figure 2).

Primarily Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea was a mixed picture of obstructive and central events in many patients. Only 3 patients had “pure” CSA. Thus, we were unable to define discrete comparison groups based on the sleep-disordered breathing phenotype. We identified 19 patients with primarily OSA (ie, initially diagnosed with OSA, OSA with TECSA, or complex sleep apnea). The mean (SD) age was 66.1 (12.8) years, BMI was 36.2 (4.7), and ESS was 11.4 (5.6). The mean (SD) baseline AHI was 46.9 (29.5), obstructive AHI was 40.5 (30.4), and central AHI was 0.4 (1.2); the median (IQR) SpO2 nadir was 81% (78%-84%). The mean (SD) titrated EPAP was 10.2 (3.5) cm H2O, and the 90th/95th percentile IPAP was 17.9 (3.5) cm H2O. The mean (SD) usage of ASV was 7.9 (5.3) hours with 11 patients (58%) meeting the minimum standard for adherence to ASV therapy.

No significant differences were seen between the adherent and nonadherent groups in clinical or demographic characteristics or date of diagnostic sleep testing (eAppendix, available online at doi:10.12788/fp.0374). In baseline sleep studies the mean (SD) HI was 32.3 (15.8) in the adherent group compared with 14.7 (8.8) in the nonadherent group (P = .049). In contrast, obstructive AHI was not significantly lower in the adherent group: 51.9 (30.9) in the adherent group compared with 22.2 (20.6) in the nonadherent group (P = .09). The median (IQR) residual AHI on ASV as a percentage of the pretreatment AHI was 3.0% (2.4%-6.5%) in the adherent group compared with 11.3% (5.4%-89.1%) in the nonadherent group, a statistically significant difference (P = .01). No other significant differences were seen between the groups.

Discussion

This study describes a real-world cohort of patients using ASV therapy and the characteristics associated with benefit from therapy. The patients that were prescribed and started ASV therapy most often had a significant degree of obstructive component to sleep-disordered breathing, whether primary OSA with TECSA or comorbid OSA and CSA. Moreover, we found that a higher obstructive AHI on the baseline PSG was associated with adherence to ASV therapy. Another important finding was that a lower residual AHI on ASV as a proportion of the baseline was associated with PAP adherence. Adherent patients had similar clinical characteristics as the nonadherent patients, including comorbidities, severity of sleep-disordered breathing, and obesity.

Though the results of the SERVE-HF trial have dampened the enthusiasm somewhat, ASV therapy has long been considered an effective and well-tolerated treatment for many types of CSA.13 In fact, treatments that can eliminate the central AHI are fairly limited.4,14 Our data suggest that ASV is also effective and tolerated in OSA with TECSA and/or comorbid CSA. Recent studies suggest that CSA resolves spontaneously in a majority of TECSA patients within 2 to 3 months of regular CPAP use.15 Other estimates suggest that persistent TESCA may be present in 2% of patients with OSA on treatment.16

Given the high and rising prevalence of OSA, many people are at risk for clinically significant TESCA. Another retrospective case series found that 72% of patients that failed treatment with CPAP or BPAP during PSG, met diagnostic criteria (at the time) for CSA; ASV was objectively beneficial in these patients.17 ASV can be an especially useful modality to treat OSA in patients with CSA that either prevents tolerance of standard therapies or causes clinical consequences, presuming the patient does not also have HFrEF.18 The long-term outcomes of treatment with ASV therapy remain a matter of debate.

The SERVE-HF trial remains among the only studies that have assessed the mortality effects of CSA treatments, with unfavorable findings. Treatment of OSA has been associated with favorable chronic health benefits, though recent studies have questioned the degree of benefit attributable to OSA treatment.19-24 Similar studies have not been done for comorbidities represented by our study cohort (ie, OSA with TECSA and/or comorbid CSA).

The lack of CSA diagnosis alone in our cohort may be partially attributable to changing practice patterns following the SERVE-HF trial, though it is not clear from these data why a higher baseline obstructive AHI was associated with adherence to ASV therapy. Our data in this regard are somewhat at odds with the preliminary results of the ADVENT-HF trial. In that study, adherence to ASV therapy in patients with predominantly OSA declined significantly more than in patients with predominantly CSA.25 Most of our patients were diagnosed with predominantly OSA, so a direct comparison with the CSA group is problematic; additionally, the primary brand and the pressure adjustments algorithm used in our study differed from the ADVENT-HF trial.

OSA and CSA may present with similar clinical symptoms, including sleep fragmentation, insomnia, and excessive daytime sleepiness; however, the degree of symptomatology, especially daytime sleepiness, and the response to treatment, may be less in CSA.2,26 Both the subjective report of symptoms (ESS) and PSG measures of sleep fragmentation were similar in our patients, again likely explained by the predominance of obstructive events.

The pathophysiology of CSA is more varied than OSA, which is probably relevant in this case. ASV was originally designed for the management of CSA with CSR, accomplishing this goal by stabilizing the periods of central apnea and hyperpnea characteristic of CSR.27 Although other forms of CSA demonstrate breathing patterns distinct from CSR, ASV has become an accepted treatment for most of these. It is plausible that the long-term subjective benefit and tolerance of ASV in CSA without CSR is less than for CSA with CSR or OSA. None of the patients in our study had CSA with CSR.

Ultimately, it may be the objective treatment effect that lends to adherence, as has been shown previously in OSA patients; our group of adherent patients showed a greater improvement in AHI, relative to baseline, than the nonadherent patients did.28 The technology behind ASV therapy can greatly reduce the frequencies of central apneas, yet this same treatment effectively splints the upper airway and even more effectively eliminates obstructive apneas and hypopneas. Variable adjusting EPAP devices would plausibly provide even more benefit in these patients, as has been shown in prior studies.29 To the contrary, our small sample of patients with TESCA showed a nonsignificant trend toward adherence with fixed EPAP ASV.

Opioid use was substantial in our population, without significant differences between the groups. CPAP therapy is ineffective in improving opioid-associated CSA. In a recent study, 20 patients on opioid therapy with CSA were treated with CPAP therapy; after several weeks, the average therapeutic use was 4 to 5 hours per night and CPAP was abandoned in favor of ASV therapy due to persistent central apnea. ASV treatment was associated with a considerable reduction in central apnea index, AHI, arousal index, and oxygen desaturations in a remarkable improvement over CPAP.30

Limitations and Future Directions

This retrospective, single-center study may have limited applicability to other populations. Adherence was used as a surrogate for subjective benefit from treatment, though benefit was not confirmed by the patients directly. Only patients seen in follow-up for documentation of the ASV download were identified for inclusion and data analysis. As a single center, we risk homogeneity in the treatment algorithms, though sleep medicine treatments are often decided at the time of the sleep studies. Studies and treatment recommendations were made at a variety of sites, including our sleep center, other US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, in the community network, and at US Department of Defense centers. Our population was homogenous in some ways; notably, 100% of our group was male, which is substantially higher than both the veteran population and the general population. Risk factors for OSA and CSA are more common in male patients, which may partially explain this anomaly. Lastly, with our small sample size, there is increased risk that the results seen occurred by chance.

There are several areas for further study. A larger multicenter study may permit these results to be generalized to the population and should include subjective measures of benefit. Patients with primarily CSA were largely absent in our group and may be the focus of future studies; data on predictors of treatment adherence in CSA are lacking. With the availability of consistent older adherence data, comparisons may be made between the efficacies of clinical practice habits, including treatment efficacy, before and after the results of the SERVE-HF trial became known.

Conclusions

In selected patients with preserved LVEF, ASV therapy appears especially effective in patients with OSA combined with CSA. Adherence to ASV treatment was associated with higher obstructive AHI during the baseline PSG and with a greater reduction in the AHI. This understanding may help guide sleep specialists in personalizing treatments for sleep-disordered breathing. Because objective efficacy appears to be important for therapy adherence, clinicians should be able to consistently determine the obstructive and central components of the residual AHI, thus taking all information into account when optimizing the treatment. Additionally, both OSA and CSA pressure requirements should be considered when developing ASV devices.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martha Harper, RRT, of Hampton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (HVAMC) for helping to identify our patients and assisting with data collection. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of HVAMC facilities.

Sleep apnea is a heterogeneous group of conditions that may be attributable to a wide array of underlying conditions, with varying contributions of obstructive or central sleep-disordered breathing. The spectrum from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) to central sleep apnea (CSA) includes mixed sleep apnea, treatment-emergent CSA (TECSA), and Cheyne-Stokes respiration (CSR).1 The pathophysiologic causes of CSA can be attributed to delayed cardiopulmonary circulation in heart failure, decreased brainstem ventilatory response due to stroke, blunting of central chemoreceptors in chronic opioid use, and/or stimulation of the Hering-Breuer reflex from activation of pulmonary stretch receptors after initiating positive airway pressure (PAP) for treatment of OSA.2,3 Medications are commonly implicated in many forms of sleep-disordered breathing; importantly, opioids and benzodiazepines may blunt the respiratory drive, leading to CSA, and/or impair upper airway patency, resulting in or worsening OSA.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is largely ineffective in correcting CSA or improving outcomes and is often poorly tolerated in these patients.4 Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is a form of bilevel PAP (BPAP) therapy that delivers variable adjusting pressure support, primarily to treat CSA. PAP also may relieve upper airway obstructions, thereby effectively treating any comorbid obstructive component. ASV has been well documented to improve sleep-related disorders and improve apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) in patients with CSA. However, longitudinal data have demonstrated increased mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) who were treated with ASV.5 Since the SERVE-HF trial results came to light in 2015, there has been no consensus regarding the optimal use, if any, of ASV therapy.6-8 This is partly related to the inability to fully explain the study’s major findings, which were unexpected at the time, and partly due to the absence of similar relevant mortality data in patients with CSA but without HFrEF.

TECSA may present in some patients with OSA who are new to PAP therapy. These events are frequently seen during PAP titration sleep studies, though patients can also experience significant TECSA shortly after initiating home PAP therapy. TECSA is felt to result from a combination of stimulating pulmonary stretch receptors and lowering arterial carbon dioxide below the apneic threshold. Chemoreceptors located in the medulla respond by attenuating the respiratory drive.9 Previous studies have shown most cases of mild TECSA resolve over time with CPAP treatment. However, in patients with persistent or worsening TECSA, ASV may be considered as an alternative to CPAP.

The prevalence of OSA in the veteran population is estimated to be as high as 60%, considerably higher than the general population estimation.10 Patients with more significant comorbidities may also experience a higher frequency of central events. Patients with CSA have also been shown to have a higher risk for cardiac-related hospital admissions, providing plausible justification for correcting CSA.10

In the current study, we aim to characterize the group of patients using ASV therapy in the modern era. We will assess the objective efficacy and adherence of ASV therapy in patients with primarily CSA compared with those having primarily OSA (ie, TECSA). Secondarily, we aim to identify baseline clinical and polysomnographic features that may be predictive of ASV adherence, as a surrogate for subjective benefit.11 In the wake of the SERVE-HF study, the sleep medicine community has paused prescribing ASV therapy for CSA. We hope to provide more perspective on the treatment of veterans with CSA and identify the patient groups that would benefit most from ASV therapy.

Methods

This retrospective chart review examined patients prescribed ASV therapy at the Hampton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (HVAMC) in Virginia who had therapy data between January 1, 2015, and April 30, 2020. The start date was chosen to approximate the phase-in of wireless PAP devices at HVAMC and to correspond with the release of preliminary results from the SERVE-HF trial.

Patients were initially identified through a query into commercial wireless PAP management databases and cross-referenced with HVAMC patients. Adherence and efficacy data were obtained from the most recent clinical PAP data, which allowed for the evaluation of patients who discontinued therapy for reasons other than intolerance. Clinical, demographic, and polysomnography (PSG) data were obtained from the electronic health record. One patient, identified through the database query but not found in the electronic health record, was excluded. In cases of missing PSG data, especially AHI or similar values, all attempts were made to calculate the data with other provided values. This study was determined to be exempt by the HVAMC Institutional Review Board (protocol #20-01).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were designed to compare clinical characteristics and adherence to therapy of those with primarily CSA on PSG and those with primarily OSA. Because it was not currently known how many patients would fit into each of these categories, we also planned secondary comparisons of the clinical and PSG characteristics of those patients who were adherent with therapy and those who were not. Adherence with ASV therapy was defined as device use for ≥ 4 hours for ≥ 70% of nights.

Comparisons between the means of 2 normally distributed groups were performed with an unpaired t test. Comparisons between 2 nonnormally distributed groups and groups of dates were done with the Mann-Whitney U test. The normality of a group distribution was determined using D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Two groups of dichotomous variables were compared with the Fisher exact test. P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Thirty-one patients were prescribed ASV therapy and had follow-up at HVAMC since 2015. All patients were male. The mean (SD) age was 67.2 (11.4) years, mean body mass index (BMI) was 34.0 (5.9), and the mean (SD) Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score was 10.9 (5.8). Patient comorbidities included 30 (97%) with hypertension, 17 (55%) with diabetes mellitus, 16 (52%) with coronary artery disease, and 11 (35%) with congestive heart failure. Three patients had no echocardiogram or other documentation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). One of these patients had voluntarily stopped using PAP therapy, another had been erroneously started on ASV (ordered for fixed BPAP), and the third had since been retitrated to CPAP. In the 28 patients with documented LVEF, the mean (SD) LVEF was 61.8% (6.9). Ten patients (32%) had opioids documented on their medication lists and 6 (19%) had benzodiazepines.

The median date of diagnostic sleep testing was January 9, 2015, and testing was completed after the release of the initial field safety notice regarding the SERVE-HF trial preliminary findings May 13, 2015, for 14 patients (45%).12 On diagnostic sleep testing, the mean (SD) AHI was 47.3 (25.6) events/h and the median (IQR) oxygen saturation (SpO2) nadir was 82% (78-84). Three patients (10%) were initially diagnosed with CSA, 19 (61%) with OSA, and 9 (29%) with both. Sixteen patients (52%) had ASV with fixed expiratory PAP (EPAP), and 15 (48%) had variable adjusting EPAP. Mean (SD) usage of ASV was 6.5 (2.6) hours and 66.0% (34.2) of nights for ≥ 4 hours. Mean (SD) titrated EPAP (set or 90th/95th percentile autotitrated) was 10.1 (3.4) cm H2O and inspiratory PAP (IPAP) (90th/95th percentile) was 17.1 (3.3) cm H2O. The median (IQR) residual AHI on ASV was 2.7 events/h (1.1-5.1), apnea index (AI) was 0.4 (0.1-1.0), and hypopnea index (HI) was 1.4 (1.0-3.2); the residual central and obstructive events were not available in most cases.

Adherence

There were no significant differences between the proportions of patients on ASV with set EPAP or the titrated EPAP and IPAP. The median (IQR) residual AHI was lower in the adherent group compared with the nonadherent group, both in absolute values (1.7 [0.9-3.2] events/h vs 4.7 [2.4-10.3] events/h, respectively [P = .004]), and as a percentage of the pretreatment AHI (3.1% [2.5-6.0] vs 10.2% [5.3-34.4], respectively; P = .002) (Figure 2).

Primarily Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea was a mixed picture of obstructive and central events in many patients. Only 3 patients had “pure” CSA. Thus, we were unable to define discrete comparison groups based on the sleep-disordered breathing phenotype. We identified 19 patients with primarily OSA (ie, initially diagnosed with OSA, OSA with TECSA, or complex sleep apnea). The mean (SD) age was 66.1 (12.8) years, BMI was 36.2 (4.7), and ESS was 11.4 (5.6). The mean (SD) baseline AHI was 46.9 (29.5), obstructive AHI was 40.5 (30.4), and central AHI was 0.4 (1.2); the median (IQR) SpO2 nadir was 81% (78%-84%). The mean (SD) titrated EPAP was 10.2 (3.5) cm H2O, and the 90th/95th percentile IPAP was 17.9 (3.5) cm H2O. The mean (SD) usage of ASV was 7.9 (5.3) hours with 11 patients (58%) meeting the minimum standard for adherence to ASV therapy.

No significant differences were seen between the adherent and nonadherent groups in clinical or demographic characteristics or date of diagnostic sleep testing (eAppendix, available online at doi:10.12788/fp.0374). In baseline sleep studies the mean (SD) HI was 32.3 (15.8) in the adherent group compared with 14.7 (8.8) in the nonadherent group (P = .049). In contrast, obstructive AHI was not significantly lower in the adherent group: 51.9 (30.9) in the adherent group compared with 22.2 (20.6) in the nonadherent group (P = .09). The median (IQR) residual AHI on ASV as a percentage of the pretreatment AHI was 3.0% (2.4%-6.5%) in the adherent group compared with 11.3% (5.4%-89.1%) in the nonadherent group, a statistically significant difference (P = .01). No other significant differences were seen between the groups.

Discussion

This study describes a real-world cohort of patients using ASV therapy and the characteristics associated with benefit from therapy. The patients that were prescribed and started ASV therapy most often had a significant degree of obstructive component to sleep-disordered breathing, whether primary OSA with TECSA or comorbid OSA and CSA. Moreover, we found that a higher obstructive AHI on the baseline PSG was associated with adherence to ASV therapy. Another important finding was that a lower residual AHI on ASV as a proportion of the baseline was associated with PAP adherence. Adherent patients had similar clinical characteristics as the nonadherent patients, including comorbidities, severity of sleep-disordered breathing, and obesity.

Though the results of the SERVE-HF trial have dampened the enthusiasm somewhat, ASV therapy has long been considered an effective and well-tolerated treatment for many types of CSA.13 In fact, treatments that can eliminate the central AHI are fairly limited.4,14 Our data suggest that ASV is also effective and tolerated in OSA with TECSA and/or comorbid CSA. Recent studies suggest that CSA resolves spontaneously in a majority of TECSA patients within 2 to 3 months of regular CPAP use.15 Other estimates suggest that persistent TESCA may be present in 2% of patients with OSA on treatment.16

Given the high and rising prevalence of OSA, many people are at risk for clinically significant TESCA. Another retrospective case series found that 72% of patients that failed treatment with CPAP or BPAP during PSG, met diagnostic criteria (at the time) for CSA; ASV was objectively beneficial in these patients.17 ASV can be an especially useful modality to treat OSA in patients with CSA that either prevents tolerance of standard therapies or causes clinical consequences, presuming the patient does not also have HFrEF.18 The long-term outcomes of treatment with ASV therapy remain a matter of debate.

The SERVE-HF trial remains among the only studies that have assessed the mortality effects of CSA treatments, with unfavorable findings. Treatment of OSA has been associated with favorable chronic health benefits, though recent studies have questioned the degree of benefit attributable to OSA treatment.19-24 Similar studies have not been done for comorbidities represented by our study cohort (ie, OSA with TECSA and/or comorbid CSA).

The lack of CSA diagnosis alone in our cohort may be partially attributable to changing practice patterns following the SERVE-HF trial, though it is not clear from these data why a higher baseline obstructive AHI was associated with adherence to ASV therapy. Our data in this regard are somewhat at odds with the preliminary results of the ADVENT-HF trial. In that study, adherence to ASV therapy in patients with predominantly OSA declined significantly more than in patients with predominantly CSA.25 Most of our patients were diagnosed with predominantly OSA, so a direct comparison with the CSA group is problematic; additionally, the primary brand and the pressure adjustments algorithm used in our study differed from the ADVENT-HF trial.

OSA and CSA may present with similar clinical symptoms, including sleep fragmentation, insomnia, and excessive daytime sleepiness; however, the degree of symptomatology, especially daytime sleepiness, and the response to treatment, may be less in CSA.2,26 Both the subjective report of symptoms (ESS) and PSG measures of sleep fragmentation were similar in our patients, again likely explained by the predominance of obstructive events.

The pathophysiology of CSA is more varied than OSA, which is probably relevant in this case. ASV was originally designed for the management of CSA with CSR, accomplishing this goal by stabilizing the periods of central apnea and hyperpnea characteristic of CSR.27 Although other forms of CSA demonstrate breathing patterns distinct from CSR, ASV has become an accepted treatment for most of these. It is plausible that the long-term subjective benefit and tolerance of ASV in CSA without CSR is less than for CSA with CSR or OSA. None of the patients in our study had CSA with CSR.

Ultimately, it may be the objective treatment effect that lends to adherence, as has been shown previously in OSA patients; our group of adherent patients showed a greater improvement in AHI, relative to baseline, than the nonadherent patients did.28 The technology behind ASV therapy can greatly reduce the frequencies of central apneas, yet this same treatment effectively splints the upper airway and even more effectively eliminates obstructive apneas and hypopneas. Variable adjusting EPAP devices would plausibly provide even more benefit in these patients, as has been shown in prior studies.29 To the contrary, our small sample of patients with TESCA showed a nonsignificant trend toward adherence with fixed EPAP ASV.

Opioid use was substantial in our population, without significant differences between the groups. CPAP therapy is ineffective in improving opioid-associated CSA. In a recent study, 20 patients on opioid therapy with CSA were treated with CPAP therapy; after several weeks, the average therapeutic use was 4 to 5 hours per night and CPAP was abandoned in favor of ASV therapy due to persistent central apnea. ASV treatment was associated with a considerable reduction in central apnea index, AHI, arousal index, and oxygen desaturations in a remarkable improvement over CPAP.30

Limitations and Future Directions

This retrospective, single-center study may have limited applicability to other populations. Adherence was used as a surrogate for subjective benefit from treatment, though benefit was not confirmed by the patients directly. Only patients seen in follow-up for documentation of the ASV download were identified for inclusion and data analysis. As a single center, we risk homogeneity in the treatment algorithms, though sleep medicine treatments are often decided at the time of the sleep studies. Studies and treatment recommendations were made at a variety of sites, including our sleep center, other US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, in the community network, and at US Department of Defense centers. Our population was homogenous in some ways; notably, 100% of our group was male, which is substantially higher than both the veteran population and the general population. Risk factors for OSA and CSA are more common in male patients, which may partially explain this anomaly. Lastly, with our small sample size, there is increased risk that the results seen occurred by chance.

There are several areas for further study. A larger multicenter study may permit these results to be generalized to the population and should include subjective measures of benefit. Patients with primarily CSA were largely absent in our group and may be the focus of future studies; data on predictors of treatment adherence in CSA are lacking. With the availability of consistent older adherence data, comparisons may be made between the efficacies of clinical practice habits, including treatment efficacy, before and after the results of the SERVE-HF trial became known.

Conclusions

In selected patients with preserved LVEF, ASV therapy appears especially effective in patients with OSA combined with CSA. Adherence to ASV treatment was associated with higher obstructive AHI during the baseline PSG and with a greater reduction in the AHI. This understanding may help guide sleep specialists in personalizing treatments for sleep-disordered breathing. Because objective efficacy appears to be important for therapy adherence, clinicians should be able to consistently determine the obstructive and central components of the residual AHI, thus taking all information into account when optimizing the treatment. Additionally, both OSA and CSA pressure requirements should be considered when developing ASV devices.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martha Harper, RRT, of Hampton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (HVAMC) for helping to identify our patients and assisting with data collection. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of HVAMC facilities.

1. Morgenthaler TI, Gay PC, Gordon N, Brown LK. Adaptive servoventilation versus noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for central, mixed, and complex sleep apnea syndromes. Sleep. 2007;30(4):468-475. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.4.468

2. Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Merchia P, Malhotra A. Central sleep apnea: pathophysiology and treatment. Chest. 2007;131(2):595-607. doi:10.1378/chest.06.2287

3. Verbraecken J. Complex sleep apnoea syndrome. Breathe. 2013;9(5):372-380. doi:10.1183/20734735.042412

4. Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2025-2033. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051001

5. Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnea in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506459

6. Imamura T, Kinugawa K. What is the optimal strategy for adaptive servo-ventilation therapy? Int Heart J. 2018;59(4):683-688. doi:10.1536/ihj.17-429

7. Javaheri S, Brown LK, Randerath W, Khayat R. SERVE-HF: more questions than answers. Chest. 2016;149(4):900-904. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.021

8. Mehra R, Gottlieb DJ. A paradigm shift in the treatment of central sleep apnea in heart failure. Chest. 2015;148(4):848-851. doi:10.1378/chest.15-1536

9. Nigam G, Riaz M, Chang E, Camacho M. Natural history of treatment-emergent central sleep apnea on positive airway pressure: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Med. 2018;13(2):86-91. doi:10.4103/atm.ATM_321_17

10. Ratz D, Wiitala W, Badr MS, Burns J, Chowdhuri S. Correlates and consequences of central sleep apnea in a national sample of US veterans. Sleep. 2018;41(9):zsy058. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsy058

11. Wolkove N, Baltzan M, Kamel H, Dabrusin R, Palayew M. Long-term compliance with continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Can Respir J. 2008;15(7):365-369. doi:10.1155/2008/534372

12. Special Safety Notice: ASV therapy for central sleep apnea patients with heart failure. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. May 15, 2015. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://aasm.org/special-safety-notice-asv-therapy-for-central-sleep-apnea-patients-with-heart-failure/

13. Philippe C, Stoïca-Herman M, Drouot X, et al. Compliance with and effectiveness of adaptive servoventilation versus continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure over a six month period. Heart. 2006;92(3):337-342. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.060038

14. Randerath W, Deleanu OC, Schiza S, Pepin J-L. Central sleep apnoea and periodic breathing in heart failure: prognostic significance and treatment options. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(153):190084. Published 2019 Oct 11. doi:10.1183/16000617.0084-2019

15. Gay PC. Complex sleep apnea: it really is a disease. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(5):403-405.

16. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders - Third Edition (ICSD-3). 3rd ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

17. Brown SE, Mosko SS, Davis JA, Pierce RA, Godfrey-Pixton TV. A retrospective case series of adaptive servoventilation for complex sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(2):187-195.

18. Aurora RN, Bista SR, Casey KR, et al. Updated Adaptive Servo-Ventilation Recommendations for the 2012 AASM Guideline: “The Treatment of Central Sleep Apnea Syndromes in Adults: Practice Parameters with an Evidence-Based Literature Review and Meta-Analyses”. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(5):757-761. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5812

19. Martínez-García MA, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Ejarque-Martínez L, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment reduces mortality in patients with ischemic stroke and obstructive sleep apnea: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):36-41. doi:10.1164/rccm.200808-1341OC

20. Martínez-García MA, Campos-Rodríguez F, Catalán-Serra P, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnea in the elderly: role of long-term continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a prospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(9):909-916. doi:10.1164/rccm.201203-0448OC

21. Neilan TG, Farhad H, Dodson JA, et al. Effect of sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac structure and recurrence of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6):e000421. Published 2013 Nov 25. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000421

22. Redline S, Adams N, Strauss ME, Roebuck T, Winters M, Rosenberg C. Improvement of mild sleep-disordered breathing with CPAP compared with conservative therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(3):858-865. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9709042

23. McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, et al. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):919-931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1606599

24. Yu J, Zhou Z, McEvoy RD, et al. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318(2):156-166. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7967

25. Perger E, Lyons OD, Inami T, et al. Predictors of 1-year compliance with adaptive servoventilation in patients with heart failure and sleep disordered breathing: preliminary data from the ADVENT-HF trial. Eur Resp J. 2019;53(2):1801626. doi:10.1183/13993003.01626-2018

26. Lyons OD, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al. Design of the effect of adaptive servo-ventilation on survival and cardiovascular hospital admissions in patients with heart failure and sleep apnoea: the ADVENT-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(4):579-587. doi:10.1002/ejhf.790

27. Teschler H, Döhring J, Wang YM, Berthon-Jones M. Adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation: a novel treatment for Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(4):614-619. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.9908114

28. Ye L, Pack AI, Maislin G, et al. Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure use during the first week of treatment. J Sleep Res. 2012;21(4):419-426. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00969.x

29. Vennelle M, White S, Riha RL, Mackay TW, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Randomized controlled trial of variable-pressure versus fixed-pressure continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment for patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS). Sleep. 2010;33(2):267-271. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.2.267

30. Javaheri S, Harris N, Howard J, Chung E. Adaptive servoventilation for treatment of opioid-associated central sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):637-643. Published 2014 Jun 15. doi:10.5664/jcsm.3788

1. Morgenthaler TI, Gay PC, Gordon N, Brown LK. Adaptive servoventilation versus noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for central, mixed, and complex sleep apnea syndromes. Sleep. 2007;30(4):468-475. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.4.468

2. Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Merchia P, Malhotra A. Central sleep apnea: pathophysiology and treatment. Chest. 2007;131(2):595-607. doi:10.1378/chest.06.2287

3. Verbraecken J. Complex sleep apnoea syndrome. Breathe. 2013;9(5):372-380. doi:10.1183/20734735.042412

4. Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2025-2033. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051001

5. Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnea in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506459

6. Imamura T, Kinugawa K. What is the optimal strategy for adaptive servo-ventilation therapy? Int Heart J. 2018;59(4):683-688. doi:10.1536/ihj.17-429

7. Javaheri S, Brown LK, Randerath W, Khayat R. SERVE-HF: more questions than answers. Chest. 2016;149(4):900-904. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.021

8. Mehra R, Gottlieb DJ. A paradigm shift in the treatment of central sleep apnea in heart failure. Chest. 2015;148(4):848-851. doi:10.1378/chest.15-1536

9. Nigam G, Riaz M, Chang E, Camacho M. Natural history of treatment-emergent central sleep apnea on positive airway pressure: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Med. 2018;13(2):86-91. doi:10.4103/atm.ATM_321_17

10. Ratz D, Wiitala W, Badr MS, Burns J, Chowdhuri S. Correlates and consequences of central sleep apnea in a national sample of US veterans. Sleep. 2018;41(9):zsy058. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsy058

11. Wolkove N, Baltzan M, Kamel H, Dabrusin R, Palayew M. Long-term compliance with continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Can Respir J. 2008;15(7):365-369. doi:10.1155/2008/534372

12. Special Safety Notice: ASV therapy for central sleep apnea patients with heart failure. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. May 15, 2015. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://aasm.org/special-safety-notice-asv-therapy-for-central-sleep-apnea-patients-with-heart-failure/

13. Philippe C, Stoïca-Herman M, Drouot X, et al. Compliance with and effectiveness of adaptive servoventilation versus continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure over a six month period. Heart. 2006;92(3):337-342. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.060038

14. Randerath W, Deleanu OC, Schiza S, Pepin J-L. Central sleep apnoea and periodic breathing in heart failure: prognostic significance and treatment options. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(153):190084. Published 2019 Oct 11. doi:10.1183/16000617.0084-2019

15. Gay PC. Complex sleep apnea: it really is a disease. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(5):403-405.

16. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders - Third Edition (ICSD-3). 3rd ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

17. Brown SE, Mosko SS, Davis JA, Pierce RA, Godfrey-Pixton TV. A retrospective case series of adaptive servoventilation for complex sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(2):187-195.

18. Aurora RN, Bista SR, Casey KR, et al. Updated Adaptive Servo-Ventilation Recommendations for the 2012 AASM Guideline: “The Treatment of Central Sleep Apnea Syndromes in Adults: Practice Parameters with an Evidence-Based Literature Review and Meta-Analyses”. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(5):757-761. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5812

19. Martínez-García MA, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Ejarque-Martínez L, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment reduces mortality in patients with ischemic stroke and obstructive sleep apnea: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):36-41. doi:10.1164/rccm.200808-1341OC

20. Martínez-García MA, Campos-Rodríguez F, Catalán-Serra P, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnea in the elderly: role of long-term continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a prospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(9):909-916. doi:10.1164/rccm.201203-0448OC

21. Neilan TG, Farhad H, Dodson JA, et al. Effect of sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac structure and recurrence of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6):e000421. Published 2013 Nov 25. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000421

22. Redline S, Adams N, Strauss ME, Roebuck T, Winters M, Rosenberg C. Improvement of mild sleep-disordered breathing with CPAP compared with conservative therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(3):858-865. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9709042

23. McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, et al. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):919-931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1606599

24. Yu J, Zhou Z, McEvoy RD, et al. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318(2):156-166. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7967

25. Perger E, Lyons OD, Inami T, et al. Predictors of 1-year compliance with adaptive servoventilation in patients with heart failure and sleep disordered breathing: preliminary data from the ADVENT-HF trial. Eur Resp J. 2019;53(2):1801626. doi:10.1183/13993003.01626-2018

26. Lyons OD, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al. Design of the effect of adaptive servo-ventilation on survival and cardiovascular hospital admissions in patients with heart failure and sleep apnoea: the ADVENT-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(4):579-587. doi:10.1002/ejhf.790

27. Teschler H, Döhring J, Wang YM, Berthon-Jones M. Adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation: a novel treatment for Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(4):614-619. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.9908114

28. Ye L, Pack AI, Maislin G, et al. Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure use during the first week of treatment. J Sleep Res. 2012;21(4):419-426. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00969.x

29. Vennelle M, White S, Riha RL, Mackay TW, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Randomized controlled trial of variable-pressure versus fixed-pressure continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment for patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS). Sleep. 2010;33(2):267-271. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.2.267

30. Javaheri S, Harris N, Howard J, Chung E. Adaptive servoventilation for treatment of opioid-associated central sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):637-643. Published 2014 Jun 15. doi:10.5664/jcsm.3788

A nod to the future of AGA

CHICAGO – It’s been 125 years since the founding of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). It’s gone from a small organization in which gastroenterology wasn’t even a known medical specialty, to an organization that grants millions of dollars in research funding each year.

He spoke with optimism about gastroenterology’s future during his presidential address on May 8 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) meeting in Chicago.

“I congratulate the AGA on its quasquicentennial, or 125th anniversary,” said Dr. Carethers, who is distinguished professor of medicine and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California, San Diego.

The AGA was founded in 1897 by Detroit-based physician Charles Aaron, MD. His passion was gastroenterology, but at that point, it wasn’t an established medical discipline. Dr. Aaron, Max Einhorn, MD, and 8 other colleagues formed the American Gastroenterological Association. Today, with nearly 16,000 members, the organization has become a driving force in improving the care of patients with gastrointestinal conditions.

Among AGA’s accomplishments since its founding: In 1940, the American Board of Internal Medicine certified gastroenterology as a subspecialty. Three years later, the first issue of Gastroenterology, the AGA’s flagship journal, was published. And, in 1971, the very first Digestive Disease Week® meeting took place.

In terms of medical advances that have been made since those early years, the list is vast: From the description of ileitis in 1932 by Burril B. Crohn, MD, in 1932 to the discovery of the hepatitis B surface antigen in 1965 and the more recent discovery of germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes as a cause of Lynch syndrome.

Dr. Carethers outlined goals for the future, including building a leadership team that is “reflective of our practice here in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said. Creating a culturally and gender diverse leadership team will only strengthen the organization and the practice of gastroenterology. The AGA’s first female president, Sarah Jordan, MD, was named in 1942, and since then, the AGA has been led by women and men from different ethnic backgrounds, including himself, who is AGA’s first president of African American heritage.

The AGA has committed to a number of diversity and equity objectives, including the AGA Equity Project, an initiative launched in 2020 whose goal is to achieve equity and eradicate disparities in digestive diseases with a focus on justice and equity, research and funding, workforce and leadership, recognition of the achievements of people of color, unconscious bias, and engagement with early career members.

“I am not only excited about the diversity and equity objectives within our specialty ... but also the innovation and things to come for our specialty,” Dr. Carethers said.

Securing funding for early-stage innovations in medicine can be difficult across medical disciplines, including gastroenterology. So, last year, the AGA, with Varia Ventures, launched the GI Opportunity Fund 1 to support early-stage GI-based companies. The goal is to raise $25 million for the initial fund. Through the AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology and the AGA Tech Summit, early-stage companies may have new funding opportunities.

And, through the AGA Research Foundation, the organization will continue to support clinical research. Last year, $2.6 million in grants were awarded to investigators.

Dr. Carethers is a board director at Avantor, a life sciences supply company.

The meeting is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

CHICAGO – It’s been 125 years since the founding of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). It’s gone from a small organization in which gastroenterology wasn’t even a known medical specialty, to an organization that grants millions of dollars in research funding each year.

He spoke with optimism about gastroenterology’s future during his presidential address on May 8 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) meeting in Chicago.