User login

For MD-IQ use only

Beware the hidden allergens in nutritional supplements

, Alison Ehrlich, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

Allergens may be hidden in a range of supplement products, from colorings in vitamin C powders to some vitamins used in hair products and other products.

“In general, our patients do not tell us what supplements they are taking,” said Dr. Ehrlich, a dermatologist who practices in Washington, D.C. Antiaging, sleep, and weight loss/weight control supplements are among the most popular, she said.

Surveys have shown that many patients do not discuss supplement use with their health care providers, in part because they believe their providers would disapprove of supplement use, and patients are not educated about supplements, she said. “This is definitely an area that we should try to learn more about,” she added.

Current regulations regarding dietary supplements stem from the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, which defined dietary supplements as distinct from meals but regulated them as a category of food, not as medications. Dietary supplements can be vitamins, minerals, herbs, and extracts, Dr. Ehrlich said.

“There is not a lot of safety wrapped around how supplements come onto the market,” she explained. “It is not the manufacturer’s responsibility to test these products and make sure they are safe. When they get pulled off the market, it is because safety reports are getting back to the FDA.”

Consequently, a detailed history of supplement use is important, as it may reveal possible allergens as the cause of previously unidentified reactions, she said.

Dr. Ehrlich shared a case involving a patient who claimed to have had a reaction to a “Prevage-like” product that was labeled as a crepe repair cream. Listed among the product’s ingredients was idebenone, a synthetic version of the popular antioxidant known as Coenzyme Q.

Be wary of vitamins

Another potential source of allergy is vitamin C supplements, which became especially popular during the pandemic as people sought additional immune system support, Dr. Ehrlich noted. “What kind of vitamin C product our patients are taking is important,” she said. For example, some vitamin C powders contain coloring agents, such as carmine. Some also contain gelatin, which may cause an allergic reaction in individuals with alpha-gal syndrome, she added.

In general, water-soluble vitamins such as vitamins B1 to B9, B12, and C are more likely to cause an immediate reaction, Dr. Ehrlich said. Fat-soluble vitamins, such as vitamins A, D, E, and K, are more likely to cause a delayed reaction of allergic contact dermatitis.

Dr. Ehrlich described some unusual reactions to vitamins that have been reported, including a systemic allergy associated with vitamin B1 (thiamine), burning mouth syndrome associated with vitamin B3 (nicotinate), contact urticaria associated with vitamin B5 (panthenol), systemic allergy and generalized ACD associated with vitamin E (tocopherol), and erythema multiforme–like ACD associated with vitamin K1.

Notably, vitamin B5 has been associated with ACD as an ingredient in hair products, moisturizers, and wound care products, as well as B-complex vitamins and fortified foods, Dr. Ehrlich said.

Herbs and spices can act as allergens as well. Turmeric is a spice that has become a popular supplement ingredient, she said. Turmeric and curcumin (found in turmeric) can be used as a dye for its yellow color as well as a flavoring but has been associated with allergic reactions. Another popular herbal supplement, ginkgo biloba, has been marketed as a product that improves memory and cognition. It is available in pill form and in herbal teas.

“It’s really important to think about what herbal products our patients are taking, and not just in pill form,” Dr. Ehrlich said. “We need to expand our thoughts on what the herbs are in.”

Consider food additives as allergens

Food additives, in the form of colorants, preservatives, or flavoring agents, can cause allergic reactions, Dr. Ehrlich noted.

The question of whether food-additive contact sensitivity has a role in the occurrence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children remains unclear, she said. However, a study published in 2020 found that 62% of children with AD had positive patch test reactions to at least one food-additive allergen, compared with 20% of children without AD. The additives responsible for the most reactions were azorubine (24.4%); formic acid (15.6%); and carmine, cochineal red, and amaranth (13.3% for each).

Common colorant culprits in allergic reactions include carmine, annatto, tartrazine, and spices (such as paprika and saffron), Dr. Ehrlich said. Carmine is used in meat to prevent photo-oxidation and to preserve a red color, and it has other uses as well, she said. Carmine has been associated with ACD, AD flares, and immediate hypersensitivity. Annatto is used in foods, including processed foods, butter, and cheese, to provide a yellow color. It is also found in some lipsticks and has been associated with urticaria and angioedema, she noted.

Food preservatives that have been associated with allergic reactions include butylated hydroxyanisole and sulfites, Dr. Ehrlich said. Sulfites are used to prevent food from turning brown, and it may be present in dried fruit, fruit juice, molasses, pickled foods, vinegar, and wine.

Reports of ACD in response to sodium metabisulfite have been increasing, she noted. Other sulfite reactions may occur with exposure to other products, such as cosmetics, body washes, and swimming pool water, she said.

Awareness of allergens in supplements is important “because the number of our patients taking supplements for different reasons is increasing” and allergens in supplements could account for flares, Dr. Ehrlich said. Clinicians should encourage patients to tell them what supplements they use. Clinicians should review the ingredients in these supplements with their patients to identify potential allergens that may be causing reactions, she advised.

Dr. Ehrlich has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, Alison Ehrlich, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

Allergens may be hidden in a range of supplement products, from colorings in vitamin C powders to some vitamins used in hair products and other products.

“In general, our patients do not tell us what supplements they are taking,” said Dr. Ehrlich, a dermatologist who practices in Washington, D.C. Antiaging, sleep, and weight loss/weight control supplements are among the most popular, she said.

Surveys have shown that many patients do not discuss supplement use with their health care providers, in part because they believe their providers would disapprove of supplement use, and patients are not educated about supplements, she said. “This is definitely an area that we should try to learn more about,” she added.

Current regulations regarding dietary supplements stem from the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, which defined dietary supplements as distinct from meals but regulated them as a category of food, not as medications. Dietary supplements can be vitamins, minerals, herbs, and extracts, Dr. Ehrlich said.

“There is not a lot of safety wrapped around how supplements come onto the market,” she explained. “It is not the manufacturer’s responsibility to test these products and make sure they are safe. When they get pulled off the market, it is because safety reports are getting back to the FDA.”

Consequently, a detailed history of supplement use is important, as it may reveal possible allergens as the cause of previously unidentified reactions, she said.

Dr. Ehrlich shared a case involving a patient who claimed to have had a reaction to a “Prevage-like” product that was labeled as a crepe repair cream. Listed among the product’s ingredients was idebenone, a synthetic version of the popular antioxidant known as Coenzyme Q.

Be wary of vitamins

Another potential source of allergy is vitamin C supplements, which became especially popular during the pandemic as people sought additional immune system support, Dr. Ehrlich noted. “What kind of vitamin C product our patients are taking is important,” she said. For example, some vitamin C powders contain coloring agents, such as carmine. Some also contain gelatin, which may cause an allergic reaction in individuals with alpha-gal syndrome, she added.

In general, water-soluble vitamins such as vitamins B1 to B9, B12, and C are more likely to cause an immediate reaction, Dr. Ehrlich said. Fat-soluble vitamins, such as vitamins A, D, E, and K, are more likely to cause a delayed reaction of allergic contact dermatitis.

Dr. Ehrlich described some unusual reactions to vitamins that have been reported, including a systemic allergy associated with vitamin B1 (thiamine), burning mouth syndrome associated with vitamin B3 (nicotinate), contact urticaria associated with vitamin B5 (panthenol), systemic allergy and generalized ACD associated with vitamin E (tocopherol), and erythema multiforme–like ACD associated with vitamin K1.

Notably, vitamin B5 has been associated with ACD as an ingredient in hair products, moisturizers, and wound care products, as well as B-complex vitamins and fortified foods, Dr. Ehrlich said.

Herbs and spices can act as allergens as well. Turmeric is a spice that has become a popular supplement ingredient, she said. Turmeric and curcumin (found in turmeric) can be used as a dye for its yellow color as well as a flavoring but has been associated with allergic reactions. Another popular herbal supplement, ginkgo biloba, has been marketed as a product that improves memory and cognition. It is available in pill form and in herbal teas.

“It’s really important to think about what herbal products our patients are taking, and not just in pill form,” Dr. Ehrlich said. “We need to expand our thoughts on what the herbs are in.”

Consider food additives as allergens

Food additives, in the form of colorants, preservatives, or flavoring agents, can cause allergic reactions, Dr. Ehrlich noted.

The question of whether food-additive contact sensitivity has a role in the occurrence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children remains unclear, she said. However, a study published in 2020 found that 62% of children with AD had positive patch test reactions to at least one food-additive allergen, compared with 20% of children without AD. The additives responsible for the most reactions were azorubine (24.4%); formic acid (15.6%); and carmine, cochineal red, and amaranth (13.3% for each).

Common colorant culprits in allergic reactions include carmine, annatto, tartrazine, and spices (such as paprika and saffron), Dr. Ehrlich said. Carmine is used in meat to prevent photo-oxidation and to preserve a red color, and it has other uses as well, she said. Carmine has been associated with ACD, AD flares, and immediate hypersensitivity. Annatto is used in foods, including processed foods, butter, and cheese, to provide a yellow color. It is also found in some lipsticks and has been associated with urticaria and angioedema, she noted.

Food preservatives that have been associated with allergic reactions include butylated hydroxyanisole and sulfites, Dr. Ehrlich said. Sulfites are used to prevent food from turning brown, and it may be present in dried fruit, fruit juice, molasses, pickled foods, vinegar, and wine.

Reports of ACD in response to sodium metabisulfite have been increasing, she noted. Other sulfite reactions may occur with exposure to other products, such as cosmetics, body washes, and swimming pool water, she said.

Awareness of allergens in supplements is important “because the number of our patients taking supplements for different reasons is increasing” and allergens in supplements could account for flares, Dr. Ehrlich said. Clinicians should encourage patients to tell them what supplements they use. Clinicians should review the ingredients in these supplements with their patients to identify potential allergens that may be causing reactions, she advised.

Dr. Ehrlich has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, Alison Ehrlich, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

Allergens may be hidden in a range of supplement products, from colorings in vitamin C powders to some vitamins used in hair products and other products.

“In general, our patients do not tell us what supplements they are taking,” said Dr. Ehrlich, a dermatologist who practices in Washington, D.C. Antiaging, sleep, and weight loss/weight control supplements are among the most popular, she said.

Surveys have shown that many patients do not discuss supplement use with their health care providers, in part because they believe their providers would disapprove of supplement use, and patients are not educated about supplements, she said. “This is definitely an area that we should try to learn more about,” she added.

Current regulations regarding dietary supplements stem from the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, which defined dietary supplements as distinct from meals but regulated them as a category of food, not as medications. Dietary supplements can be vitamins, minerals, herbs, and extracts, Dr. Ehrlich said.

“There is not a lot of safety wrapped around how supplements come onto the market,” she explained. “It is not the manufacturer’s responsibility to test these products and make sure they are safe. When they get pulled off the market, it is because safety reports are getting back to the FDA.”

Consequently, a detailed history of supplement use is important, as it may reveal possible allergens as the cause of previously unidentified reactions, she said.

Dr. Ehrlich shared a case involving a patient who claimed to have had a reaction to a “Prevage-like” product that was labeled as a crepe repair cream. Listed among the product’s ingredients was idebenone, a synthetic version of the popular antioxidant known as Coenzyme Q.

Be wary of vitamins

Another potential source of allergy is vitamin C supplements, which became especially popular during the pandemic as people sought additional immune system support, Dr. Ehrlich noted. “What kind of vitamin C product our patients are taking is important,” she said. For example, some vitamin C powders contain coloring agents, such as carmine. Some also contain gelatin, which may cause an allergic reaction in individuals with alpha-gal syndrome, she added.

In general, water-soluble vitamins such as vitamins B1 to B9, B12, and C are more likely to cause an immediate reaction, Dr. Ehrlich said. Fat-soluble vitamins, such as vitamins A, D, E, and K, are more likely to cause a delayed reaction of allergic contact dermatitis.

Dr. Ehrlich described some unusual reactions to vitamins that have been reported, including a systemic allergy associated with vitamin B1 (thiamine), burning mouth syndrome associated with vitamin B3 (nicotinate), contact urticaria associated with vitamin B5 (panthenol), systemic allergy and generalized ACD associated with vitamin E (tocopherol), and erythema multiforme–like ACD associated with vitamin K1.

Notably, vitamin B5 has been associated with ACD as an ingredient in hair products, moisturizers, and wound care products, as well as B-complex vitamins and fortified foods, Dr. Ehrlich said.

Herbs and spices can act as allergens as well. Turmeric is a spice that has become a popular supplement ingredient, she said. Turmeric and curcumin (found in turmeric) can be used as a dye for its yellow color as well as a flavoring but has been associated with allergic reactions. Another popular herbal supplement, ginkgo biloba, has been marketed as a product that improves memory and cognition. It is available in pill form and in herbal teas.

“It’s really important to think about what herbal products our patients are taking, and not just in pill form,” Dr. Ehrlich said. “We need to expand our thoughts on what the herbs are in.”

Consider food additives as allergens

Food additives, in the form of colorants, preservatives, or flavoring agents, can cause allergic reactions, Dr. Ehrlich noted.

The question of whether food-additive contact sensitivity has a role in the occurrence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children remains unclear, she said. However, a study published in 2020 found that 62% of children with AD had positive patch test reactions to at least one food-additive allergen, compared with 20% of children without AD. The additives responsible for the most reactions were azorubine (24.4%); formic acid (15.6%); and carmine, cochineal red, and amaranth (13.3% for each).

Common colorant culprits in allergic reactions include carmine, annatto, tartrazine, and spices (such as paprika and saffron), Dr. Ehrlich said. Carmine is used in meat to prevent photo-oxidation and to preserve a red color, and it has other uses as well, she said. Carmine has been associated with ACD, AD flares, and immediate hypersensitivity. Annatto is used in foods, including processed foods, butter, and cheese, to provide a yellow color. It is also found in some lipsticks and has been associated with urticaria and angioedema, she noted.

Food preservatives that have been associated with allergic reactions include butylated hydroxyanisole and sulfites, Dr. Ehrlich said. Sulfites are used to prevent food from turning brown, and it may be present in dried fruit, fruit juice, molasses, pickled foods, vinegar, and wine.

Reports of ACD in response to sodium metabisulfite have been increasing, she noted. Other sulfite reactions may occur with exposure to other products, such as cosmetics, body washes, and swimming pool water, she said.

Awareness of allergens in supplements is important “because the number of our patients taking supplements for different reasons is increasing” and allergens in supplements could account for flares, Dr. Ehrlich said. Clinicians should encourage patients to tell them what supplements they use. Clinicians should review the ingredients in these supplements with their patients to identify potential allergens that may be causing reactions, she advised.

Dr. Ehrlich has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACDS 2023

Phase 3 trial: Maribavir yields post-transplant benefits

Overall mortality in the 109 patients from these subcohorts from SOLSTICE was lower, compared with mortality reported for similar populations treated with conventional therapies used to treat relapsed or refractory (R/R) CMV, according to findings presented in April at the annual meeting of the European Society for Bone and Marrow Transplantation.

“These results, in addition to the superior efficacy in CMV clearance observed for maribavir in SOLSTICE provide supportive evidence of the potential for the long-term benefit of maribavir treatment for post-transplant CMV infection,” Ishan Hirji, of Takeda Development Center Americas, and colleagues reported during a poster session at the meeting.

A retrospective chart review of the 41 hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients and 68 solid organ transplant (SOT) patients randomized to receive maribavir showed an overall mortality rate of 15.6% at 52 weeks after initiation of treatment with the antiviral agent. Among the HSCT patients, 14 deaths occurred (34.1%), with 8 occurring during the study periods and 6 occurring during follow-up. Among the SOT patients, three deaths occurred (4.4%), all during follow-up chart review.

Causes of death included underlying disease relapse in four patients, infection other than CMV in six patients, and one case each of CMV-related factors, transplant-related factors, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and septic shock. Causes of death in the SOT patients included one case each of CMV-related factors, anemia, and renal failure.

“No patients had new graft loss or retransplantation during the chart review period,” the investigators noted.

The findings are notable as CMV infection occurs in 30%-70% of HSCT recipients and 16%-56% of SOT recipients and can lead to complications, including transplant failure and death. Reported 1-year mortality rates following standard therapies for CMV range from 31% to 50%, they explained.

Patients in the SOLSTICE trial received 8 weeks of treatment and were followed for 12 additional weeks. CMV clearance at the end of treatment was 55.7% in the maribavir treatment arm versus 23.9% in a control group of patients treated with investigator choice of therapy. As reported by this news organization, the findings formed the basis for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of maribavir in November 2021.

The current analysis included a chart review period that started 1 day after the SOLSTICE trial period and continued for 32 additional weeks.

These long-term follow-up data confirm the benefits of maribavir for the treatment of post-transplant CMV, according to the investigators, and findings from a separate study reported at the ESBMT meeting underscore the importance of the durable benefits observed with maribavir treatment.

For that retrospective study, Maria Laura Fox, of Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, and colleagues pooled de-identified data from 250 adult HSCT recipients with R/R CMV who were treated with agents other than maribavir at transplant centers in the United States or Europe. They aimed to “generate real-world evidence on the burden of CMV infection/disease in HSCT recipients who had refractory/resistant CMV or were intolerant to current treatments.”

Nearly 92% of patients received two or more therapies to treat CMV, and 92.2% discontinued treatment or had one or more therapy dose changes or discontinuation, and 42 patients failed to achieve clearance of the CMV index episode.

CMV recurred in 35.2% of patients, and graft failure occurred in 4% of patients, the investigators reported.

All-cause mortality was 56.0%, and mortality at 1 year after identification of R/R disease or treatment intolerance was 45.2%, they noted, adding that the study results “highlight the real-world complexities and high burden of CMV infection for HSCT recipients.”

“With available anti-CMV agents [excluding maribavir], a notable proportion of patients failed to achieve viremia clearance once developing RRI [resistant, refractory, or intolerant] CMV and/or experienced recurrence, and were at risk of adverse outcomes, including myelosuppression and mortality. There is a need for therapies that achieve and maintain CMV clearance with improved safety profiles,” they concluded.

Both studies were funded by Takeda Development Center Americas, the maker of Levtencity. Ms. Hirji is an employee of Takeda and reported stock ownership. Ms. Fox reported relationships with Sierra Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, and AbbVie.

Overall mortality in the 109 patients from these subcohorts from SOLSTICE was lower, compared with mortality reported for similar populations treated with conventional therapies used to treat relapsed or refractory (R/R) CMV, according to findings presented in April at the annual meeting of the European Society for Bone and Marrow Transplantation.

“These results, in addition to the superior efficacy in CMV clearance observed for maribavir in SOLSTICE provide supportive evidence of the potential for the long-term benefit of maribavir treatment for post-transplant CMV infection,” Ishan Hirji, of Takeda Development Center Americas, and colleagues reported during a poster session at the meeting.

A retrospective chart review of the 41 hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients and 68 solid organ transplant (SOT) patients randomized to receive maribavir showed an overall mortality rate of 15.6% at 52 weeks after initiation of treatment with the antiviral agent. Among the HSCT patients, 14 deaths occurred (34.1%), with 8 occurring during the study periods and 6 occurring during follow-up. Among the SOT patients, three deaths occurred (4.4%), all during follow-up chart review.

Causes of death included underlying disease relapse in four patients, infection other than CMV in six patients, and one case each of CMV-related factors, transplant-related factors, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and septic shock. Causes of death in the SOT patients included one case each of CMV-related factors, anemia, and renal failure.

“No patients had new graft loss or retransplantation during the chart review period,” the investigators noted.

The findings are notable as CMV infection occurs in 30%-70% of HSCT recipients and 16%-56% of SOT recipients and can lead to complications, including transplant failure and death. Reported 1-year mortality rates following standard therapies for CMV range from 31% to 50%, they explained.

Patients in the SOLSTICE trial received 8 weeks of treatment and were followed for 12 additional weeks. CMV clearance at the end of treatment was 55.7% in the maribavir treatment arm versus 23.9% in a control group of patients treated with investigator choice of therapy. As reported by this news organization, the findings formed the basis for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of maribavir in November 2021.

The current analysis included a chart review period that started 1 day after the SOLSTICE trial period and continued for 32 additional weeks.

These long-term follow-up data confirm the benefits of maribavir for the treatment of post-transplant CMV, according to the investigators, and findings from a separate study reported at the ESBMT meeting underscore the importance of the durable benefits observed with maribavir treatment.

For that retrospective study, Maria Laura Fox, of Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, and colleagues pooled de-identified data from 250 adult HSCT recipients with R/R CMV who were treated with agents other than maribavir at transplant centers in the United States or Europe. They aimed to “generate real-world evidence on the burden of CMV infection/disease in HSCT recipients who had refractory/resistant CMV or were intolerant to current treatments.”

Nearly 92% of patients received two or more therapies to treat CMV, and 92.2% discontinued treatment or had one or more therapy dose changes or discontinuation, and 42 patients failed to achieve clearance of the CMV index episode.

CMV recurred in 35.2% of patients, and graft failure occurred in 4% of patients, the investigators reported.

All-cause mortality was 56.0%, and mortality at 1 year after identification of R/R disease or treatment intolerance was 45.2%, they noted, adding that the study results “highlight the real-world complexities and high burden of CMV infection for HSCT recipients.”

“With available anti-CMV agents [excluding maribavir], a notable proportion of patients failed to achieve viremia clearance once developing RRI [resistant, refractory, or intolerant] CMV and/or experienced recurrence, and were at risk of adverse outcomes, including myelosuppression and mortality. There is a need for therapies that achieve and maintain CMV clearance with improved safety profiles,” they concluded.

Both studies were funded by Takeda Development Center Americas, the maker of Levtencity. Ms. Hirji is an employee of Takeda and reported stock ownership. Ms. Fox reported relationships with Sierra Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, and AbbVie.

Overall mortality in the 109 patients from these subcohorts from SOLSTICE was lower, compared with mortality reported for similar populations treated with conventional therapies used to treat relapsed or refractory (R/R) CMV, according to findings presented in April at the annual meeting of the European Society for Bone and Marrow Transplantation.

“These results, in addition to the superior efficacy in CMV clearance observed for maribavir in SOLSTICE provide supportive evidence of the potential for the long-term benefit of maribavir treatment for post-transplant CMV infection,” Ishan Hirji, of Takeda Development Center Americas, and colleagues reported during a poster session at the meeting.

A retrospective chart review of the 41 hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients and 68 solid organ transplant (SOT) patients randomized to receive maribavir showed an overall mortality rate of 15.6% at 52 weeks after initiation of treatment with the antiviral agent. Among the HSCT patients, 14 deaths occurred (34.1%), with 8 occurring during the study periods and 6 occurring during follow-up. Among the SOT patients, three deaths occurred (4.4%), all during follow-up chart review.

Causes of death included underlying disease relapse in four patients, infection other than CMV in six patients, and one case each of CMV-related factors, transplant-related factors, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and septic shock. Causes of death in the SOT patients included one case each of CMV-related factors, anemia, and renal failure.

“No patients had new graft loss or retransplantation during the chart review period,” the investigators noted.

The findings are notable as CMV infection occurs in 30%-70% of HSCT recipients and 16%-56% of SOT recipients and can lead to complications, including transplant failure and death. Reported 1-year mortality rates following standard therapies for CMV range from 31% to 50%, they explained.

Patients in the SOLSTICE trial received 8 weeks of treatment and were followed for 12 additional weeks. CMV clearance at the end of treatment was 55.7% in the maribavir treatment arm versus 23.9% in a control group of patients treated with investigator choice of therapy. As reported by this news organization, the findings formed the basis for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of maribavir in November 2021.

The current analysis included a chart review period that started 1 day after the SOLSTICE trial period and continued for 32 additional weeks.

These long-term follow-up data confirm the benefits of maribavir for the treatment of post-transplant CMV, according to the investigators, and findings from a separate study reported at the ESBMT meeting underscore the importance of the durable benefits observed with maribavir treatment.

For that retrospective study, Maria Laura Fox, of Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, and colleagues pooled de-identified data from 250 adult HSCT recipients with R/R CMV who were treated with agents other than maribavir at transplant centers in the United States or Europe. They aimed to “generate real-world evidence on the burden of CMV infection/disease in HSCT recipients who had refractory/resistant CMV or were intolerant to current treatments.”

Nearly 92% of patients received two or more therapies to treat CMV, and 92.2% discontinued treatment or had one or more therapy dose changes or discontinuation, and 42 patients failed to achieve clearance of the CMV index episode.

CMV recurred in 35.2% of patients, and graft failure occurred in 4% of patients, the investigators reported.

All-cause mortality was 56.0%, and mortality at 1 year after identification of R/R disease or treatment intolerance was 45.2%, they noted, adding that the study results “highlight the real-world complexities and high burden of CMV infection for HSCT recipients.”

“With available anti-CMV agents [excluding maribavir], a notable proportion of patients failed to achieve viremia clearance once developing RRI [resistant, refractory, or intolerant] CMV and/or experienced recurrence, and were at risk of adverse outcomes, including myelosuppression and mortality. There is a need for therapies that achieve and maintain CMV clearance with improved safety profiles,” they concluded.

Both studies were funded by Takeda Development Center Americas, the maker of Levtencity. Ms. Hirji is an employee of Takeda and reported stock ownership. Ms. Fox reported relationships with Sierra Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, and AbbVie.

FROM ESBMT 2023

Autism and bone health: What you need to know

Many years ago, at the conclusion of a talk I gave on bone health in teens with anorexia nervosa, I was approached by a colleague, Ann Neumeyer, MD, medical director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who asked about bone health in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

When I explained that there was little information about bone health in this patient population, she suggested that we learn and investigate together. Ann explained that she had observed that some of her patients with ASD had suffered fractures with minimal trauma, raising her concern about their bone health.

This was the beginning of a partnership that led us down the path of many grant submissions, some of which were funded and others that were not, to explore and investigate bone outcomes in children with ASD.

This applies to prepubertal children as well as older children and adolescents. One study showed that 28% and 33% of children with ASD 8-14 years old had very low bone density (z scores of ≤ –2) at the spine and hip, respectively, compared with 0% of typically developing controls.

Studies that have used sophisticated imaging techniques to determine bone strength have shown that it is lower at the forearm and lower leg in children with ASD versus neurotypical children.

These findings are of particular concern during the childhood and teenage years when bone is typically accrued at a rapid rate. A normal rate of bone accrual at this time of life is essential for optimal bone health in later life. While children with ASD gain bone mass at a similar rate as neurotypical controls, they start at a deficit and seem unable to “catch up.”

Further, people with ASD are more prone to certain kinds of fracture than those without the condition. For example, both children and adults with ASD have a high risk for hip fracture, while adult women with ASD have a higher risk for forearm and spine fractures. There is some protection against forearm fractures in children and adult men, probably because of markedly lower levels of physical activity, which would reduce fall risk.

Many of Ann’s patients with ASD had unusual or restricted diets, low levels of physical activity, and were on multiple medications. We have since learned that some factors that contribute to low bone density in ASD include lower levels of weight-bearing physical activity; lower muscle mass; low muscle tone; suboptimal dietary calcium and vitamin D intake; lower vitamin D levels; higher levels of the hormone cortisol, which has deleterious effects on bone; and use of medications that can lower bone density.

In order to mitigate the risk for low bone density and fractures, it is important to optimize physical activity while considering the child’s ability to safely engage in weight-bearing sports.

High-impact sports like gymnastics and jumping, or cross-impact sports like soccer, basketball, field hockey, and lacrosse, are particularly useful in this context, but many patients with ASD are not able to easily engage in typical team sports.

For such children, a prescribed amount of time spent walking, as well as weight and resistance training, could be helpful. The latter would also help increase muscle mass, a key modulator of bone health.

Other strategies include ensuring sufficient intake of calcium and vitamin D through diet and supplements. This can be a particular challenge for children with ASD on specialized diets, such as a gluten-free or dairy-free diet, which are deficient in calcium and vitamin D. Health care providers should check for intake of dairy and dairy products, as well as serum vitamin D levels, and prescribe supplements as needed.

All children should get at least 600 IUs of vitamin D and 1,000-1,300 mg of elemental calcium daily. That said, many with ASD need much higher quantities of vitamin D (1,000-4,000 IUs or more) to maintain levels in the normal range. This is particularly true for dark-skinned children and children with obesity, as well as those who have medical disorders that cause malabsorption.

Higher cortisol levels in the ASD patient population are harder to manage. Efforts to ease anxiety and depression may help reduce cortisol levels. Medications such as protein pump inhibitors and glucocorticosteroids can compromise bone health.

In addition, certain antipsychotics can cause marked elevations in prolactin which, in turn, can lower levels of estrogen and testosterone, which are very important for bone health. In such cases, the clinician should consider switching patients to a different, less detrimental medication or adjust the current medication so that patients receive the lowest possible effective dose.

Obesity is associated with increased fracture risk and with suboptimal bone accrual during childhood, so ensuring a healthy diet is important. This includes avoiding sugary beverages and reducing intake of processed food and juice.

Sometimes, particularly when a child has low bone density and a history of several low-trauma fractures, medications such as bisphosphonates should be considered to increase bone density.

Above all, as physicians who manage ASD, it is essential that we raise awareness about bone health among our colleagues, patients, and their families to help mitigate fracture risk.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is chief of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at Mass General for Children, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many years ago, at the conclusion of a talk I gave on bone health in teens with anorexia nervosa, I was approached by a colleague, Ann Neumeyer, MD, medical director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who asked about bone health in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

When I explained that there was little information about bone health in this patient population, she suggested that we learn and investigate together. Ann explained that she had observed that some of her patients with ASD had suffered fractures with minimal trauma, raising her concern about their bone health.

This was the beginning of a partnership that led us down the path of many grant submissions, some of which were funded and others that were not, to explore and investigate bone outcomes in children with ASD.

This applies to prepubertal children as well as older children and adolescents. One study showed that 28% and 33% of children with ASD 8-14 years old had very low bone density (z scores of ≤ –2) at the spine and hip, respectively, compared with 0% of typically developing controls.

Studies that have used sophisticated imaging techniques to determine bone strength have shown that it is lower at the forearm and lower leg in children with ASD versus neurotypical children.

These findings are of particular concern during the childhood and teenage years when bone is typically accrued at a rapid rate. A normal rate of bone accrual at this time of life is essential for optimal bone health in later life. While children with ASD gain bone mass at a similar rate as neurotypical controls, they start at a deficit and seem unable to “catch up.”

Further, people with ASD are more prone to certain kinds of fracture than those without the condition. For example, both children and adults with ASD have a high risk for hip fracture, while adult women with ASD have a higher risk for forearm and spine fractures. There is some protection against forearm fractures in children and adult men, probably because of markedly lower levels of physical activity, which would reduce fall risk.

Many of Ann’s patients with ASD had unusual or restricted diets, low levels of physical activity, and were on multiple medications. We have since learned that some factors that contribute to low bone density in ASD include lower levels of weight-bearing physical activity; lower muscle mass; low muscle tone; suboptimal dietary calcium and vitamin D intake; lower vitamin D levels; higher levels of the hormone cortisol, which has deleterious effects on bone; and use of medications that can lower bone density.

In order to mitigate the risk for low bone density and fractures, it is important to optimize physical activity while considering the child’s ability to safely engage in weight-bearing sports.

High-impact sports like gymnastics and jumping, or cross-impact sports like soccer, basketball, field hockey, and lacrosse, are particularly useful in this context, but many patients with ASD are not able to easily engage in typical team sports.

For such children, a prescribed amount of time spent walking, as well as weight and resistance training, could be helpful. The latter would also help increase muscle mass, a key modulator of bone health.

Other strategies include ensuring sufficient intake of calcium and vitamin D through diet and supplements. This can be a particular challenge for children with ASD on specialized diets, such as a gluten-free or dairy-free diet, which are deficient in calcium and vitamin D. Health care providers should check for intake of dairy and dairy products, as well as serum vitamin D levels, and prescribe supplements as needed.

All children should get at least 600 IUs of vitamin D and 1,000-1,300 mg of elemental calcium daily. That said, many with ASD need much higher quantities of vitamin D (1,000-4,000 IUs or more) to maintain levels in the normal range. This is particularly true for dark-skinned children and children with obesity, as well as those who have medical disorders that cause malabsorption.

Higher cortisol levels in the ASD patient population are harder to manage. Efforts to ease anxiety and depression may help reduce cortisol levels. Medications such as protein pump inhibitors and glucocorticosteroids can compromise bone health.

In addition, certain antipsychotics can cause marked elevations in prolactin which, in turn, can lower levels of estrogen and testosterone, which are very important for bone health. In such cases, the clinician should consider switching patients to a different, less detrimental medication or adjust the current medication so that patients receive the lowest possible effective dose.

Obesity is associated with increased fracture risk and with suboptimal bone accrual during childhood, so ensuring a healthy diet is important. This includes avoiding sugary beverages and reducing intake of processed food and juice.

Sometimes, particularly when a child has low bone density and a history of several low-trauma fractures, medications such as bisphosphonates should be considered to increase bone density.

Above all, as physicians who manage ASD, it is essential that we raise awareness about bone health among our colleagues, patients, and their families to help mitigate fracture risk.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is chief of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at Mass General for Children, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many years ago, at the conclusion of a talk I gave on bone health in teens with anorexia nervosa, I was approached by a colleague, Ann Neumeyer, MD, medical director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who asked about bone health in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

When I explained that there was little information about bone health in this patient population, she suggested that we learn and investigate together. Ann explained that she had observed that some of her patients with ASD had suffered fractures with minimal trauma, raising her concern about their bone health.

This was the beginning of a partnership that led us down the path of many grant submissions, some of which were funded and others that were not, to explore and investigate bone outcomes in children with ASD.

This applies to prepubertal children as well as older children and adolescents. One study showed that 28% and 33% of children with ASD 8-14 years old had very low bone density (z scores of ≤ –2) at the spine and hip, respectively, compared with 0% of typically developing controls.

Studies that have used sophisticated imaging techniques to determine bone strength have shown that it is lower at the forearm and lower leg in children with ASD versus neurotypical children.

These findings are of particular concern during the childhood and teenage years when bone is typically accrued at a rapid rate. A normal rate of bone accrual at this time of life is essential for optimal bone health in later life. While children with ASD gain bone mass at a similar rate as neurotypical controls, they start at a deficit and seem unable to “catch up.”

Further, people with ASD are more prone to certain kinds of fracture than those without the condition. For example, both children and adults with ASD have a high risk for hip fracture, while adult women with ASD have a higher risk for forearm and spine fractures. There is some protection against forearm fractures in children and adult men, probably because of markedly lower levels of physical activity, which would reduce fall risk.

Many of Ann’s patients with ASD had unusual or restricted diets, low levels of physical activity, and were on multiple medications. We have since learned that some factors that contribute to low bone density in ASD include lower levels of weight-bearing physical activity; lower muscle mass; low muscle tone; suboptimal dietary calcium and vitamin D intake; lower vitamin D levels; higher levels of the hormone cortisol, which has deleterious effects on bone; and use of medications that can lower bone density.

In order to mitigate the risk for low bone density and fractures, it is important to optimize physical activity while considering the child’s ability to safely engage in weight-bearing sports.

High-impact sports like gymnastics and jumping, or cross-impact sports like soccer, basketball, field hockey, and lacrosse, are particularly useful in this context, but many patients with ASD are not able to easily engage in typical team sports.

For such children, a prescribed amount of time spent walking, as well as weight and resistance training, could be helpful. The latter would also help increase muscle mass, a key modulator of bone health.

Other strategies include ensuring sufficient intake of calcium and vitamin D through diet and supplements. This can be a particular challenge for children with ASD on specialized diets, such as a gluten-free or dairy-free diet, which are deficient in calcium and vitamin D. Health care providers should check for intake of dairy and dairy products, as well as serum vitamin D levels, and prescribe supplements as needed.

All children should get at least 600 IUs of vitamin D and 1,000-1,300 mg of elemental calcium daily. That said, many with ASD need much higher quantities of vitamin D (1,000-4,000 IUs or more) to maintain levels in the normal range. This is particularly true for dark-skinned children and children with obesity, as well as those who have medical disorders that cause malabsorption.

Higher cortisol levels in the ASD patient population are harder to manage. Efforts to ease anxiety and depression may help reduce cortisol levels. Medications such as protein pump inhibitors and glucocorticosteroids can compromise bone health.

In addition, certain antipsychotics can cause marked elevations in prolactin which, in turn, can lower levels of estrogen and testosterone, which are very important for bone health. In such cases, the clinician should consider switching patients to a different, less detrimental medication or adjust the current medication so that patients receive the lowest possible effective dose.

Obesity is associated with increased fracture risk and with suboptimal bone accrual during childhood, so ensuring a healthy diet is important. This includes avoiding sugary beverages and reducing intake of processed food and juice.

Sometimes, particularly when a child has low bone density and a history of several low-trauma fractures, medications such as bisphosphonates should be considered to increase bone density.

Above all, as physicians who manage ASD, it is essential that we raise awareness about bone health among our colleagues, patients, and their families to help mitigate fracture risk.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is chief of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at Mass General for Children, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation during pregnancy: An alternative to antidepressant treatment?

A growing number of women ask about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy.

The last several decades have brought an increasing level of comfort with respect to antidepressant use during pregnancy, which derives from several factors.

First, it’s been well described that there’s an increased risk of relapse and morbidity associated with discontinuation of antidepressants proximate to pregnancy, particularly in women with histories of recurrent disease (JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80[5]:441-50 and JAMA. 2006;295[5]:499-507).

Second, there’s an obvious increased confidence about using antidepressants during pregnancy given the robust reproductive safety data about antidepressants with respect to both teratogenesis and risk for organ malformation. Other studies also fail to demonstrate a relationship between fetal exposure to antidepressants and risk for subsequent development of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. These latter studies have been reviewed extensively in systematic reviews of meta-analyses addressing this question.

However, there are women who, as they approach the question of antidepressant use during pregnancy, would prefer a nonpharmacologic approach to managing depression in the setting of either a planned pregnancy, or sometimes in the setting of acute onset of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Other women are more comfortable with the data in hand regarding the reproductive safety of antidepressants and continue antidepressants that have afforded emotional well-being, particularly if the road to well-being or euthymia has been a long one.

Still, we at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Women’s Mental Health along with multidisciplinary colleagues with whom we engage during our weekly Virtual Rounds community have observed a growing number of women asking about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy. They ask about these options for personal reasons, regardless of what we may know (and what we may not know) about existing pharmacologic interventions. In these scenarios, it is important to keep in mind that it is not about what we as clinicians necessarily know about these medicines per se that drives treatment, but rather about the private calculus that women and their partners apply about risk and benefit of pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy.

Nonpharmacologic treatment options

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and behavioral activation are therapies all of which have an evidence base with respect to their effectiveness for either the acute treatment of both depression (and perinatal depression specifically) or for mitigating risk for depressive relapse (MBCT). Several investigations are underway evaluating digital apps that utilize MBCT and CBT in these patient populations as well.

New treatments for which we have none or exceedingly sparse data to support use during pregnancy are neurosteroids. We are asked all the time about the use of neurosteroids such as brexanolone or zuranolone during pregnancy. Given the data on effectiveness of these agents for treatment of postpartum depression, the question about use during pregnancy is intuitive. But at this point in time, absent data, their use during pregnancy cannot be recommended.

With respect to newer nonpharmacologic approaches that have been looked at for treatment of major depressive disorder, the Food and Drug Administration has approved transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a noninvasive form of neuromodulating therapy that use magnetic pulses to stimulate specific regions of the brain that have been implicated in psychiatric illness.

While there are no safety concerns that have been noted about use of TMS, the data regarding its use during pregnancy are still relatively limited, but it has been used to treat certain neurologic conditions during pregnancy. We now have a small randomized controlled study using TMS during pregnancy and multiple small case series suggesting a signal of efficacy in women with perinatal major depressive disorder. Side effects of TMS use during pregnancy have included hypotension, which has sometimes required repositioning of subjects, particularly later in pregnancy. Unlike electroconvulsive therapy, (ECT), often used when clinicians have exhausted other treatment options, TMS has no risk of seizure associated with its use.

TMS is now entering into the clinical arena in a more robust way. In certain settings, insurance companies are reimbursing for TMS treatment more often than was the case previously, making it a more viable option for a larger number of patients. There are also several exciting newer protocols, including theta burst stimulation, a new form of TMS treatment with less of a time commitment, and which may be more cost effective. However, data on this modality of treatment remain limited.

Where TMS fits in treating depression during pregnancy

The real question we are getting asked in clinic, both in person and during virtual rounds with multidisciplinary colleagues from across the world, is where TMS might fit into the algorithm for treating of depression during pregnancy. Where is it appropriate to be thinking about TMS in pregnancy, and where should it perhaps be deferred at this moment (and where is it not appropriate)?

It is probably of limited value (and possibly of potential harm) to switch to TMS in patients who have severe recurrent major depression and who are on maintenance antidepressant, and who believe that a switch to TMS will be effective for relapse prevention; there are simply no data currently suggesting that TMS can be used as a relapse prevention tool, unlike certain other nonpharmacologic interventions.

What about managing relapse of major depressive disorder during pregnancy in a patient who had responded to an antidepressant? We have seen patients with histories of severe recurrent disease who are managed well on antidepressants during pregnancy who then have breakthrough symptoms and inquire about using TMS as an augmentation strategy. Although we don’t have clear data supporting the use of TMS as an adjunct in that setting, in those patients, one could argue that a trial of TMS may be appropriate – as opposed to introducing multiple medicines to recapture euthymia during pregnancy where the benefit is unclear and where more exposure is implied by having to do potentially multiple trials.

Other patients with new onset of depression during pregnancy who, for personal reasons, will not take an antidepressant or pursue other nonpharmacologic interventions will frequently ask about TMS. and the increased availability of TMS in the community in various centers – as opposed to previously where it was more restricted to large academic medical centers.

I think it is a time of excitement in reproductive psychiatry where we have a growing number of tools to treat perinatal depression – from medications to digital tools. These tools – either alone or in combination with medicines that we’ve been using for years – are able to afford women a greater number of choices with respect to the treatment of perinatal depression than was available even 5 years ago. That takes us closer to an ability to use interventions that truly combine patient wishes and “precision perinatal psychiatry,” where we can match effective therapies with the individual clinical presentations and wishes with which patients come to us.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

A growing number of women ask about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy.

The last several decades have brought an increasing level of comfort with respect to antidepressant use during pregnancy, which derives from several factors.

First, it’s been well described that there’s an increased risk of relapse and morbidity associated with discontinuation of antidepressants proximate to pregnancy, particularly in women with histories of recurrent disease (JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80[5]:441-50 and JAMA. 2006;295[5]:499-507).

Second, there’s an obvious increased confidence about using antidepressants during pregnancy given the robust reproductive safety data about antidepressants with respect to both teratogenesis and risk for organ malformation. Other studies also fail to demonstrate a relationship between fetal exposure to antidepressants and risk for subsequent development of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. These latter studies have been reviewed extensively in systematic reviews of meta-analyses addressing this question.

However, there are women who, as they approach the question of antidepressant use during pregnancy, would prefer a nonpharmacologic approach to managing depression in the setting of either a planned pregnancy, or sometimes in the setting of acute onset of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Other women are more comfortable with the data in hand regarding the reproductive safety of antidepressants and continue antidepressants that have afforded emotional well-being, particularly if the road to well-being or euthymia has been a long one.

Still, we at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Women’s Mental Health along with multidisciplinary colleagues with whom we engage during our weekly Virtual Rounds community have observed a growing number of women asking about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy. They ask about these options for personal reasons, regardless of what we may know (and what we may not know) about existing pharmacologic interventions. In these scenarios, it is important to keep in mind that it is not about what we as clinicians necessarily know about these medicines per se that drives treatment, but rather about the private calculus that women and their partners apply about risk and benefit of pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy.

Nonpharmacologic treatment options

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and behavioral activation are therapies all of which have an evidence base with respect to their effectiveness for either the acute treatment of both depression (and perinatal depression specifically) or for mitigating risk for depressive relapse (MBCT). Several investigations are underway evaluating digital apps that utilize MBCT and CBT in these patient populations as well.

New treatments for which we have none or exceedingly sparse data to support use during pregnancy are neurosteroids. We are asked all the time about the use of neurosteroids such as brexanolone or zuranolone during pregnancy. Given the data on effectiveness of these agents for treatment of postpartum depression, the question about use during pregnancy is intuitive. But at this point in time, absent data, their use during pregnancy cannot be recommended.

With respect to newer nonpharmacologic approaches that have been looked at for treatment of major depressive disorder, the Food and Drug Administration has approved transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a noninvasive form of neuromodulating therapy that use magnetic pulses to stimulate specific regions of the brain that have been implicated in psychiatric illness.

While there are no safety concerns that have been noted about use of TMS, the data regarding its use during pregnancy are still relatively limited, but it has been used to treat certain neurologic conditions during pregnancy. We now have a small randomized controlled study using TMS during pregnancy and multiple small case series suggesting a signal of efficacy in women with perinatal major depressive disorder. Side effects of TMS use during pregnancy have included hypotension, which has sometimes required repositioning of subjects, particularly later in pregnancy. Unlike electroconvulsive therapy, (ECT), often used when clinicians have exhausted other treatment options, TMS has no risk of seizure associated with its use.

TMS is now entering into the clinical arena in a more robust way. In certain settings, insurance companies are reimbursing for TMS treatment more often than was the case previously, making it a more viable option for a larger number of patients. There are also several exciting newer protocols, including theta burst stimulation, a new form of TMS treatment with less of a time commitment, and which may be more cost effective. However, data on this modality of treatment remain limited.

Where TMS fits in treating depression during pregnancy

The real question we are getting asked in clinic, both in person and during virtual rounds with multidisciplinary colleagues from across the world, is where TMS might fit into the algorithm for treating of depression during pregnancy. Where is it appropriate to be thinking about TMS in pregnancy, and where should it perhaps be deferred at this moment (and where is it not appropriate)?

It is probably of limited value (and possibly of potential harm) to switch to TMS in patients who have severe recurrent major depression and who are on maintenance antidepressant, and who believe that a switch to TMS will be effective for relapse prevention; there are simply no data currently suggesting that TMS can be used as a relapse prevention tool, unlike certain other nonpharmacologic interventions.

What about managing relapse of major depressive disorder during pregnancy in a patient who had responded to an antidepressant? We have seen patients with histories of severe recurrent disease who are managed well on antidepressants during pregnancy who then have breakthrough symptoms and inquire about using TMS as an augmentation strategy. Although we don’t have clear data supporting the use of TMS as an adjunct in that setting, in those patients, one could argue that a trial of TMS may be appropriate – as opposed to introducing multiple medicines to recapture euthymia during pregnancy where the benefit is unclear and where more exposure is implied by having to do potentially multiple trials.

Other patients with new onset of depression during pregnancy who, for personal reasons, will not take an antidepressant or pursue other nonpharmacologic interventions will frequently ask about TMS. and the increased availability of TMS in the community in various centers – as opposed to previously where it was more restricted to large academic medical centers.

I think it is a time of excitement in reproductive psychiatry where we have a growing number of tools to treat perinatal depression – from medications to digital tools. These tools – either alone or in combination with medicines that we’ve been using for years – are able to afford women a greater number of choices with respect to the treatment of perinatal depression than was available even 5 years ago. That takes us closer to an ability to use interventions that truly combine patient wishes and “precision perinatal psychiatry,” where we can match effective therapies with the individual clinical presentations and wishes with which patients come to us.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

A growing number of women ask about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy.

The last several decades have brought an increasing level of comfort with respect to antidepressant use during pregnancy, which derives from several factors.

First, it’s been well described that there’s an increased risk of relapse and morbidity associated with discontinuation of antidepressants proximate to pregnancy, particularly in women with histories of recurrent disease (JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80[5]:441-50 and JAMA. 2006;295[5]:499-507).

Second, there’s an obvious increased confidence about using antidepressants during pregnancy given the robust reproductive safety data about antidepressants with respect to both teratogenesis and risk for organ malformation. Other studies also fail to demonstrate a relationship between fetal exposure to antidepressants and risk for subsequent development of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. These latter studies have been reviewed extensively in systematic reviews of meta-analyses addressing this question.

However, there are women who, as they approach the question of antidepressant use during pregnancy, would prefer a nonpharmacologic approach to managing depression in the setting of either a planned pregnancy, or sometimes in the setting of acute onset of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Other women are more comfortable with the data in hand regarding the reproductive safety of antidepressants and continue antidepressants that have afforded emotional well-being, particularly if the road to well-being or euthymia has been a long one.

Still, we at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Women’s Mental Health along with multidisciplinary colleagues with whom we engage during our weekly Virtual Rounds community have observed a growing number of women asking about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy. They ask about these options for personal reasons, regardless of what we may know (and what we may not know) about existing pharmacologic interventions. In these scenarios, it is important to keep in mind that it is not about what we as clinicians necessarily know about these medicines per se that drives treatment, but rather about the private calculus that women and their partners apply about risk and benefit of pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy.

Nonpharmacologic treatment options

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and behavioral activation are therapies all of which have an evidence base with respect to their effectiveness for either the acute treatment of both depression (and perinatal depression specifically) or for mitigating risk for depressive relapse (MBCT). Several investigations are underway evaluating digital apps that utilize MBCT and CBT in these patient populations as well.

New treatments for which we have none or exceedingly sparse data to support use during pregnancy are neurosteroids. We are asked all the time about the use of neurosteroids such as brexanolone or zuranolone during pregnancy. Given the data on effectiveness of these agents for treatment of postpartum depression, the question about use during pregnancy is intuitive. But at this point in time, absent data, their use during pregnancy cannot be recommended.

With respect to newer nonpharmacologic approaches that have been looked at for treatment of major depressive disorder, the Food and Drug Administration has approved transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a noninvasive form of neuromodulating therapy that use magnetic pulses to stimulate specific regions of the brain that have been implicated in psychiatric illness.

While there are no safety concerns that have been noted about use of TMS, the data regarding its use during pregnancy are still relatively limited, but it has been used to treat certain neurologic conditions during pregnancy. We now have a small randomized controlled study using TMS during pregnancy and multiple small case series suggesting a signal of efficacy in women with perinatal major depressive disorder. Side effects of TMS use during pregnancy have included hypotension, which has sometimes required repositioning of subjects, particularly later in pregnancy. Unlike electroconvulsive therapy, (ECT), often used when clinicians have exhausted other treatment options, TMS has no risk of seizure associated with its use.

TMS is now entering into the clinical arena in a more robust way. In certain settings, insurance companies are reimbursing for TMS treatment more often than was the case previously, making it a more viable option for a larger number of patients. There are also several exciting newer protocols, including theta burst stimulation, a new form of TMS treatment with less of a time commitment, and which may be more cost effective. However, data on this modality of treatment remain limited.

Where TMS fits in treating depression during pregnancy

The real question we are getting asked in clinic, both in person and during virtual rounds with multidisciplinary colleagues from across the world, is where TMS might fit into the algorithm for treating of depression during pregnancy. Where is it appropriate to be thinking about TMS in pregnancy, and where should it perhaps be deferred at this moment (and where is it not appropriate)?

It is probably of limited value (and possibly of potential harm) to switch to TMS in patients who have severe recurrent major depression and who are on maintenance antidepressant, and who believe that a switch to TMS will be effective for relapse prevention; there are simply no data currently suggesting that TMS can be used as a relapse prevention tool, unlike certain other nonpharmacologic interventions.

What about managing relapse of major depressive disorder during pregnancy in a patient who had responded to an antidepressant? We have seen patients with histories of severe recurrent disease who are managed well on antidepressants during pregnancy who then have breakthrough symptoms and inquire about using TMS as an augmentation strategy. Although we don’t have clear data supporting the use of TMS as an adjunct in that setting, in those patients, one could argue that a trial of TMS may be appropriate – as opposed to introducing multiple medicines to recapture euthymia during pregnancy where the benefit is unclear and where more exposure is implied by having to do potentially multiple trials.

Other patients with new onset of depression during pregnancy who, for personal reasons, will not take an antidepressant or pursue other nonpharmacologic interventions will frequently ask about TMS. and the increased availability of TMS in the community in various centers – as opposed to previously where it was more restricted to large academic medical centers.

I think it is a time of excitement in reproductive psychiatry where we have a growing number of tools to treat perinatal depression – from medications to digital tools. These tools – either alone or in combination with medicines that we’ve been using for years – are able to afford women a greater number of choices with respect to the treatment of perinatal depression than was available even 5 years ago. That takes us closer to an ability to use interventions that truly combine patient wishes and “precision perinatal psychiatry,” where we can match effective therapies with the individual clinical presentations and wishes with which patients come to us.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

Medical-level empathy? Yup, ChatGPT can fake that

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

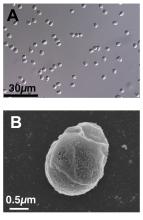

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.