User login

FDA approves first tocilizumab biosimilar

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the biosimilar tocilizumab-bavi (Tofidence), Biogen, the drug’s manufacturer, announced on Sept. 29.

It is the first tocilizumab biosimilar approved by the FDA. The reference product, Actemra (Genentech), was first approved by the agency in 2010.

“The approval of Tofidence in the U.S. marks another positive step toward helping more people with chronic autoimmune conditions gain access to leading therapies,” Ian Henshaw, global head of biosimilars at Biogen, said in a statement. “With the increasing numbers of approved biosimilars, we expect increased savings and sustainability for health care systems and an increase in physician choice and patient access to biologics.”

Biogen’s pricing for tocilizumab-bavi will be available closer to the product’s launch date, which has yet to be determined, a company spokesman said. The U.S. average monthly cost of Actemra for rheumatoid arthritis, administered intravenously, is $2,134-$4,268 depending on dosage, according to a Genentech spokesperson.

Tocilizumab-bavi is an intravenous formulation (20 mg/mL) indicated for treatment of moderately to severely active RA, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (PJIA), and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA). The medication is administered every 4 weeks in RA and PJIA and every 8 weeks in SJIA as a single intravenous drip infusion over 1 hour.

The European Commission approved its first tocilizumab biosimilar, Tyenne (Fresenius Kabi), earlier in 2023 in both subcutaneous and intravenous formulations. Biogen did not comment on whether the company is working on a subcutaneous formulation for tocilizumab-bavi.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the biosimilar tocilizumab-bavi (Tofidence), Biogen, the drug’s manufacturer, announced on Sept. 29.

It is the first tocilizumab biosimilar approved by the FDA. The reference product, Actemra (Genentech), was first approved by the agency in 2010.

“The approval of Tofidence in the U.S. marks another positive step toward helping more people with chronic autoimmune conditions gain access to leading therapies,” Ian Henshaw, global head of biosimilars at Biogen, said in a statement. “With the increasing numbers of approved biosimilars, we expect increased savings and sustainability for health care systems and an increase in physician choice and patient access to biologics.”

Biogen’s pricing for tocilizumab-bavi will be available closer to the product’s launch date, which has yet to be determined, a company spokesman said. The U.S. average monthly cost of Actemra for rheumatoid arthritis, administered intravenously, is $2,134-$4,268 depending on dosage, according to a Genentech spokesperson.

Tocilizumab-bavi is an intravenous formulation (20 mg/mL) indicated for treatment of moderately to severely active RA, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (PJIA), and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA). The medication is administered every 4 weeks in RA and PJIA and every 8 weeks in SJIA as a single intravenous drip infusion over 1 hour.

The European Commission approved its first tocilizumab biosimilar, Tyenne (Fresenius Kabi), earlier in 2023 in both subcutaneous and intravenous formulations. Biogen did not comment on whether the company is working on a subcutaneous formulation for tocilizumab-bavi.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the biosimilar tocilizumab-bavi (Tofidence), Biogen, the drug’s manufacturer, announced on Sept. 29.

It is the first tocilizumab biosimilar approved by the FDA. The reference product, Actemra (Genentech), was first approved by the agency in 2010.

“The approval of Tofidence in the U.S. marks another positive step toward helping more people with chronic autoimmune conditions gain access to leading therapies,” Ian Henshaw, global head of biosimilars at Biogen, said in a statement. “With the increasing numbers of approved biosimilars, we expect increased savings and sustainability for health care systems and an increase in physician choice and patient access to biologics.”

Biogen’s pricing for tocilizumab-bavi will be available closer to the product’s launch date, which has yet to be determined, a company spokesman said. The U.S. average monthly cost of Actemra for rheumatoid arthritis, administered intravenously, is $2,134-$4,268 depending on dosage, according to a Genentech spokesperson.

Tocilizumab-bavi is an intravenous formulation (20 mg/mL) indicated for treatment of moderately to severely active RA, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (PJIA), and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA). The medication is administered every 4 weeks in RA and PJIA and every 8 weeks in SJIA as a single intravenous drip infusion over 1 hour.

The European Commission approved its first tocilizumab biosimilar, Tyenne (Fresenius Kabi), earlier in 2023 in both subcutaneous and intravenous formulations. Biogen did not comment on whether the company is working on a subcutaneous formulation for tocilizumab-bavi.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Should people who play sports pay higher medical insurance premiums?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re anywhere near Seattle, anywhere near Florida, or anywhere where it might be not oppressively hot outside but encouraging some people who might want to go out and get a little exercise, you’ve undoubtedly seen or heard of pickleball.

This took off, I think, out of Bainbridge Island, Wash. It was meant as a gentlemanly game where people didn’t exert themselves too much. The joke is you could play it while holding a drink in one hand. It’s gotten more popular and more competitive. It’s kind of a miniature version of tennis, with a smaller court, a plastic ball, and a wooden paddle. The ball can go back and forth rapidly, but you’re always playing doubles and it doesn’t take as much energy, exertion, and, if you will, fitness as a game like singles tennis.

The upside is it’s gotten many people outdoors getting some exercise and socializing. That’s all to the good. But a recent study suggested that there are about $500 million worth of injuries coming into the health care system associated with pickleball. There have been leg sprains, broken bones, people getting hit in the eye, hamstring pulls, and many other problems. I’ve been told that many of the spectators who show up for pickleball matches are there with a cast or have some kind of a wrap on because they were injured.

Well, many people have argued in the past about what we are going to do about health care costs. Some suggest if you voluntarily incur health care damage, you ought to pay for that yourself and you ought to have a big copay.

If you decide you’re going to do cross-country skiing or downhill skiing and you injure yourself, you chose to do it, so you pay. If you’re not going to maintain your weight, you’re going to smoke, or you’re going to ride around without a helmet, that’s your choice. You ought to pay.

I think the pickleball example is really a good challenge to these views. You obviously want people to go out and get some exercise. Here, we’re talking about a population that’s a little older and oftentimes doesn’t get out there as much as doctors would like to get the exercise that’s still important that they need, and yet it does incur injuries and problems.

My suggestion would be to make the game a little safer. Let’s try to encourage people to warm up more before they get out there and jump out of the car and engage in their pickleball battles. Goggles might be important to prevent the eye injuries in a game that’s played up close. Maybe we want to make sure that people look out for one another out there. If they think they’re getting dehydrated or tired, they should say, “Let’s sit down.”

I’m not willing to put a tax or a copay on the pickleball players of America. I know they choose to do it. It’s got an upside and benefits, as many things like skiing and other behaviors that have some risk do, but I think we want to be encouraging, not discouraging, of it.

I don’t like a society where anybody who tries to do something that takes risk winds up bearing extra cost for doing that. I understand that that gets people irritated when it comes to dangerous, hyper-risky behavior like smoking and not wearing a motorcycle helmet. I think the way to engage is not to call out the sinner or to try and punish those who are trying to do things that bring them enjoyment, reward, or in some of these cases, physical fitness, but to try to make things safer and try to gradually improve and get rid of the risk side to capture the full benefit side.

I’m not sure I’ve come up with all the best ways to make pickleball safer, but I think that’s where our thinking in health care should go. My view is to get out there and play pickleball. If you do pull your hamstring, raise my insurance premium a little bit. I’ll help to pay for it. Better you get some enjoyment and some exercise.

I get the downside, but come on, folks, we ought to be, as a community, somewhat supportive of the fun and recreation that our fellow citizens engage in.

Dr. Caplan is director, division of medical ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center. He disclosed serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position); and as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re anywhere near Seattle, anywhere near Florida, or anywhere where it might be not oppressively hot outside but encouraging some people who might want to go out and get a little exercise, you’ve undoubtedly seen or heard of pickleball.

This took off, I think, out of Bainbridge Island, Wash. It was meant as a gentlemanly game where people didn’t exert themselves too much. The joke is you could play it while holding a drink in one hand. It’s gotten more popular and more competitive. It’s kind of a miniature version of tennis, with a smaller court, a plastic ball, and a wooden paddle. The ball can go back and forth rapidly, but you’re always playing doubles and it doesn’t take as much energy, exertion, and, if you will, fitness as a game like singles tennis.

The upside is it’s gotten many people outdoors getting some exercise and socializing. That’s all to the good. But a recent study suggested that there are about $500 million worth of injuries coming into the health care system associated with pickleball. There have been leg sprains, broken bones, people getting hit in the eye, hamstring pulls, and many other problems. I’ve been told that many of the spectators who show up for pickleball matches are there with a cast or have some kind of a wrap on because they were injured.

Well, many people have argued in the past about what we are going to do about health care costs. Some suggest if you voluntarily incur health care damage, you ought to pay for that yourself and you ought to have a big copay.

If you decide you’re going to do cross-country skiing or downhill skiing and you injure yourself, you chose to do it, so you pay. If you’re not going to maintain your weight, you’re going to smoke, or you’re going to ride around without a helmet, that’s your choice. You ought to pay.

I think the pickleball example is really a good challenge to these views. You obviously want people to go out and get some exercise. Here, we’re talking about a population that’s a little older and oftentimes doesn’t get out there as much as doctors would like to get the exercise that’s still important that they need, and yet it does incur injuries and problems.

My suggestion would be to make the game a little safer. Let’s try to encourage people to warm up more before they get out there and jump out of the car and engage in their pickleball battles. Goggles might be important to prevent the eye injuries in a game that’s played up close. Maybe we want to make sure that people look out for one another out there. If they think they’re getting dehydrated or tired, they should say, “Let’s sit down.”

I’m not willing to put a tax or a copay on the pickleball players of America. I know they choose to do it. It’s got an upside and benefits, as many things like skiing and other behaviors that have some risk do, but I think we want to be encouraging, not discouraging, of it.

I don’t like a society where anybody who tries to do something that takes risk winds up bearing extra cost for doing that. I understand that that gets people irritated when it comes to dangerous, hyper-risky behavior like smoking and not wearing a motorcycle helmet. I think the way to engage is not to call out the sinner or to try and punish those who are trying to do things that bring them enjoyment, reward, or in some of these cases, physical fitness, but to try to make things safer and try to gradually improve and get rid of the risk side to capture the full benefit side.

I’m not sure I’ve come up with all the best ways to make pickleball safer, but I think that’s where our thinking in health care should go. My view is to get out there and play pickleball. If you do pull your hamstring, raise my insurance premium a little bit. I’ll help to pay for it. Better you get some enjoyment and some exercise.

I get the downside, but come on, folks, we ought to be, as a community, somewhat supportive of the fun and recreation that our fellow citizens engage in.

Dr. Caplan is director, division of medical ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center. He disclosed serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position); and as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re anywhere near Seattle, anywhere near Florida, or anywhere where it might be not oppressively hot outside but encouraging some people who might want to go out and get a little exercise, you’ve undoubtedly seen or heard of pickleball.

This took off, I think, out of Bainbridge Island, Wash. It was meant as a gentlemanly game where people didn’t exert themselves too much. The joke is you could play it while holding a drink in one hand. It’s gotten more popular and more competitive. It’s kind of a miniature version of tennis, with a smaller court, a plastic ball, and a wooden paddle. The ball can go back and forth rapidly, but you’re always playing doubles and it doesn’t take as much energy, exertion, and, if you will, fitness as a game like singles tennis.

The upside is it’s gotten many people outdoors getting some exercise and socializing. That’s all to the good. But a recent study suggested that there are about $500 million worth of injuries coming into the health care system associated with pickleball. There have been leg sprains, broken bones, people getting hit in the eye, hamstring pulls, and many other problems. I’ve been told that many of the spectators who show up for pickleball matches are there with a cast or have some kind of a wrap on because they were injured.

Well, many people have argued in the past about what we are going to do about health care costs. Some suggest if you voluntarily incur health care damage, you ought to pay for that yourself and you ought to have a big copay.

If you decide you’re going to do cross-country skiing or downhill skiing and you injure yourself, you chose to do it, so you pay. If you’re not going to maintain your weight, you’re going to smoke, or you’re going to ride around without a helmet, that’s your choice. You ought to pay.

I think the pickleball example is really a good challenge to these views. You obviously want people to go out and get some exercise. Here, we’re talking about a population that’s a little older and oftentimes doesn’t get out there as much as doctors would like to get the exercise that’s still important that they need, and yet it does incur injuries and problems.

My suggestion would be to make the game a little safer. Let’s try to encourage people to warm up more before they get out there and jump out of the car and engage in their pickleball battles. Goggles might be important to prevent the eye injuries in a game that’s played up close. Maybe we want to make sure that people look out for one another out there. If they think they’re getting dehydrated or tired, they should say, “Let’s sit down.”

I’m not willing to put a tax or a copay on the pickleball players of America. I know they choose to do it. It’s got an upside and benefits, as many things like skiing and other behaviors that have some risk do, but I think we want to be encouraging, not discouraging, of it.

I don’t like a society where anybody who tries to do something that takes risk winds up bearing extra cost for doing that. I understand that that gets people irritated when it comes to dangerous, hyper-risky behavior like smoking and not wearing a motorcycle helmet. I think the way to engage is not to call out the sinner or to try and punish those who are trying to do things that bring them enjoyment, reward, or in some of these cases, physical fitness, but to try to make things safer and try to gradually improve and get rid of the risk side to capture the full benefit side.

I’m not sure I’ve come up with all the best ways to make pickleball safer, but I think that’s where our thinking in health care should go. My view is to get out there and play pickleball. If you do pull your hamstring, raise my insurance premium a little bit. I’ll help to pay for it. Better you get some enjoyment and some exercise.

I get the downside, but come on, folks, we ought to be, as a community, somewhat supportive of the fun and recreation that our fellow citizens engage in.

Dr. Caplan is director, division of medical ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center. He disclosed serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position); and as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Treating fractures in elderly patients: Beyond the broken bone

While half the fracture-prevention battle is getting people diagnosed with low bone density, nearly 80% of older Americans who suffer bone breaks are not tested or treated for osteoporosis. Fractures associated with aging and diminished bone mineral density exact an enormous toll on patients’ lives and cost the health care system billions of dollars annually according to Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. But current gaps in patient education and bone density screening are huge.

“It’s concerning that older patients at risk for fracture are often not screened to determine their risk factors contributing to osteoporosis and patients are not educated about fracture prevention,” said Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, an endocrinologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and chief of calcium and bone section, and professor of medicine, at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Furthermore, the majority of highest-risk women and men who do have fractures are not screened and they do not receive effective, [Food and Drug Administration]–approved therapies.”

Recent guidelines

Screening with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is recommended for all women at age 65 and all men at age 70. But the occasion of a fracture in an older person who has not yet met these age thresholds should prompt a bone density assessment.

“Doctors need to stress that one in two women and one in four men over age 50 will have a fracture in their remaining lifetimes,” Dr. LeBoff said. ”Primary care doctors play a critical role in ordering timely bone densitometry for both sexes.

If an older patient has been treated for a fracture, the main goal going forward is to prevent another one, for which the risk is highest in the 2 years after the incident fracture.”

According to Kendall F. Moseley, MD, clinical director of the division of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, “Elderly patients need to understand that a fracture at their age is like a heart attack of the bone,” she said, adding that just as cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure and blood lipids are silent before a stroke or infarction, the bone thinning of old age is also silent.

Endocrinologist Jennifer J. Kelly, DO, director of the metabolic bone program and an associate professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington, said a fracture in anyone over age 50 that appears not to have resulted from a traumatic blow, is a compelling reason to order a DEXA exam.

Nahid J. Rianon, MBBS/MD, DrPH, assistant professor of the division of geriatric medicine at the UTHealth McGovern Medical School, Houston, goes further: “Any fracture in someone age 50 and older warrants screening for osteoporosis. And if the fracture is nontraumatic, that is by definition a clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis regardless of normal results on bone density tests and they should be treated medically. There are aspects of bone that we still can’t measure in the clinical setting.”

If DEXA is not accessible, fracture risk over the next 10 years can be evaluated based on multiple patient characteristics and medical history using the online FRAX calculator.

Just a 3% risk of hip fracture on FRAX is considered an indication to begin medical osteoporosis treatment in the United States regardless of bone density test results, Dr. Rianon said.

Fracture management

Whether a senior suffers a traumatic fracture or an osteoporosis-related fragility fracture, older age can impede the healing process in some. Senescence may also increase systemic proinflammatory status, according to Clark and colleagues, writing in Current Osteoporosis Reports.

They called for research to develop more directed treatment options for the elderly population.

Dr. Rianon noted that healing may also be affected by a decrease in muscle mass, which plays a role in holding the bone in place. “But it is still controversial how changing metabolic factors affect bone healing in the elderly.”

However, countered Dr. Kelly, fractures in elderly patients are not necessarily less likely to mend – if osteoporosis is not present. “Many heal very well – it really depends more upon their overall health and medical history. Whether or not a person requires surgery depends more upon the extent of the fracture and if the bone is able to align and heal appropriately without surgery.”

Fracture sites

Spine. According to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons the earliest and most frequent site of fragility fractures in the elderly is the spine. Most vertebral fracture pain improves within 3 months without specific treatment. A short period of rest, limited analgesic use, and possible back bracing may help as the fractures heal on their own. But if pain is severe and persistent, vertebral augmentation with percutaneous kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty may be an option. These procedures, however, can destabilize surrounding discs because of the greater thickness of the injected cement.

Hip. The most dangerous fractures occur in the hip. These carry at least a 20% risk of death in the first postoperative year and must be treated surgically. Those in the proximal femur, the head, or the femoral neck will usually need hip replacement, but if the break is farther down, it may be repaired with cement, screws, plates, and rods.

Distal radius. Outcomes of wrist fractures may be positive without surgical intervention, according to a recent retrospective analysis from Turkey by Yalin and colleagues. In a comparison of clinical outcomes in seniors aged 70-89 and assigned to cast immobilization or various surgical treatments for distal radius fractures, no statistically significant difference was found in patient-reported disability scores and range of motion values between casting and surgery in the first postoperative year.

Other sites. Fractures in the elderly are not uncommon in the shoulder, distal radius, cubitus, proximal humerus, and humerus. These fractures are often treated without surgery, but nevertheless signal a high risk for additional fractures.

Bone-enhancing medications

Even in the absence of diagnosed low bone density or osteoporosis, anabolic agents such as the synthetic human parathyroid hormones abaloparatide (Tymlos) and teriparatide (Forteo) may be used to help in some cases with a bad healing prognosis and may also be used for people undergoing surgeries such as a spinal fusion, but there are not clinical guidelines. “We receive referrals regularly for this treatment from our orthopedics colleagues, but it is considered an off-label use,” Dr. Kelly said.

The anabolics teriparatide and romosozumab (Evenity) have proved effective in lowering fractures in high-risk older women.

Post fracture

After recovering from a fracture, elderly people are strongly advised to make lifestyle changes to boost bone health and reduce risk of further fractures, said Willy M. Valencia, MD, a geriatrician-endocrinologist at the Cleveland Clinic. Apart from active daily living, he recommends several types of formal exercise to promote bone formation; increase muscle mass, strength, and flexibility; and improve endurance, balance, and gait. The National Institute on Aging outlines suitable exercise programs for seniors.

“These exercises will help reduce the risk of falling and to avoid more fractures,” he said. “Whether a patient has been exercising before the fracture or not, they may feel some reticence or reluctance to take up exercise afterwards because they’re afraid of having another fracture, but they should understand that their fracture risk increases if they remain sedentary. They should start slowly but they can’t be sitting all day.”

Even before it’s possible to exercise at the healing fracture site, added Dr. Rianon, its advisable to work other areas of the body. “Overall mobility is important, and exercising other parts of the body can stimulate strength and help prevent falling.”

In other postsurgical measures, a bone-friendly diet rich in calcium and vitamin D, as well as supplementation with these vital nutrients, is essential to lower the risk of falling.

Fall prevention is paramount, said Dr. Valencia. While exercise can improve, gait, balance, and endurance, logistical measures may also be necessary. Seniors may have to move to a one-floor domicile with no stairs to negotiate. At the very least, they need to fall-proof their daily lives by upgrading their eyeglasses and home lighting, eliminating obstacles and loose carpets, fixing bannisters, and installing bathroom handrails. Some may need assistive devices for walking, especially outdoors in slippery conditions.

At the end of the day, the role of the primary physician in screening for bone problems before fracture and postsurgical care is key. “Risk factors for osteoporosis and fracture risk must be added to the patient’s chart,” said Dr. Rianon. Added Dr. Moseley. “No matter how busy they are, my hope is that primary care physicians will not put patients’ bone health at the bottom of the clinical agenda.”

While half the fracture-prevention battle is getting people diagnosed with low bone density, nearly 80% of older Americans who suffer bone breaks are not tested or treated for osteoporosis. Fractures associated with aging and diminished bone mineral density exact an enormous toll on patients’ lives and cost the health care system billions of dollars annually according to Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. But current gaps in patient education and bone density screening are huge.

“It’s concerning that older patients at risk for fracture are often not screened to determine their risk factors contributing to osteoporosis and patients are not educated about fracture prevention,” said Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, an endocrinologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and chief of calcium and bone section, and professor of medicine, at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Furthermore, the majority of highest-risk women and men who do have fractures are not screened and they do not receive effective, [Food and Drug Administration]–approved therapies.”

Recent guidelines

Screening with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is recommended for all women at age 65 and all men at age 70. But the occasion of a fracture in an older person who has not yet met these age thresholds should prompt a bone density assessment.

“Doctors need to stress that one in two women and one in four men over age 50 will have a fracture in their remaining lifetimes,” Dr. LeBoff said. ”Primary care doctors play a critical role in ordering timely bone densitometry for both sexes.

If an older patient has been treated for a fracture, the main goal going forward is to prevent another one, for which the risk is highest in the 2 years after the incident fracture.”

According to Kendall F. Moseley, MD, clinical director of the division of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, “Elderly patients need to understand that a fracture at their age is like a heart attack of the bone,” she said, adding that just as cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure and blood lipids are silent before a stroke or infarction, the bone thinning of old age is also silent.

Endocrinologist Jennifer J. Kelly, DO, director of the metabolic bone program and an associate professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington, said a fracture in anyone over age 50 that appears not to have resulted from a traumatic blow, is a compelling reason to order a DEXA exam.

Nahid J. Rianon, MBBS/MD, DrPH, assistant professor of the division of geriatric medicine at the UTHealth McGovern Medical School, Houston, goes further: “Any fracture in someone age 50 and older warrants screening for osteoporosis. And if the fracture is nontraumatic, that is by definition a clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis regardless of normal results on bone density tests and they should be treated medically. There are aspects of bone that we still can’t measure in the clinical setting.”

If DEXA is not accessible, fracture risk over the next 10 years can be evaluated based on multiple patient characteristics and medical history using the online FRAX calculator.

Just a 3% risk of hip fracture on FRAX is considered an indication to begin medical osteoporosis treatment in the United States regardless of bone density test results, Dr. Rianon said.

Fracture management

Whether a senior suffers a traumatic fracture or an osteoporosis-related fragility fracture, older age can impede the healing process in some. Senescence may also increase systemic proinflammatory status, according to Clark and colleagues, writing in Current Osteoporosis Reports.

They called for research to develop more directed treatment options for the elderly population.

Dr. Rianon noted that healing may also be affected by a decrease in muscle mass, which plays a role in holding the bone in place. “But it is still controversial how changing metabolic factors affect bone healing in the elderly.”

However, countered Dr. Kelly, fractures in elderly patients are not necessarily less likely to mend – if osteoporosis is not present. “Many heal very well – it really depends more upon their overall health and medical history. Whether or not a person requires surgery depends more upon the extent of the fracture and if the bone is able to align and heal appropriately without surgery.”

Fracture sites

Spine. According to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons the earliest and most frequent site of fragility fractures in the elderly is the spine. Most vertebral fracture pain improves within 3 months without specific treatment. A short period of rest, limited analgesic use, and possible back bracing may help as the fractures heal on their own. But if pain is severe and persistent, vertebral augmentation with percutaneous kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty may be an option. These procedures, however, can destabilize surrounding discs because of the greater thickness of the injected cement.

Hip. The most dangerous fractures occur in the hip. These carry at least a 20% risk of death in the first postoperative year and must be treated surgically. Those in the proximal femur, the head, or the femoral neck will usually need hip replacement, but if the break is farther down, it may be repaired with cement, screws, plates, and rods.

Distal radius. Outcomes of wrist fractures may be positive without surgical intervention, according to a recent retrospective analysis from Turkey by Yalin and colleagues. In a comparison of clinical outcomes in seniors aged 70-89 and assigned to cast immobilization or various surgical treatments for distal radius fractures, no statistically significant difference was found in patient-reported disability scores and range of motion values between casting and surgery in the first postoperative year.

Other sites. Fractures in the elderly are not uncommon in the shoulder, distal radius, cubitus, proximal humerus, and humerus. These fractures are often treated without surgery, but nevertheless signal a high risk for additional fractures.

Bone-enhancing medications

Even in the absence of diagnosed low bone density or osteoporosis, anabolic agents such as the synthetic human parathyroid hormones abaloparatide (Tymlos) and teriparatide (Forteo) may be used to help in some cases with a bad healing prognosis and may also be used for people undergoing surgeries such as a spinal fusion, but there are not clinical guidelines. “We receive referrals regularly for this treatment from our orthopedics colleagues, but it is considered an off-label use,” Dr. Kelly said.

The anabolics teriparatide and romosozumab (Evenity) have proved effective in lowering fractures in high-risk older women.

Post fracture

After recovering from a fracture, elderly people are strongly advised to make lifestyle changes to boost bone health and reduce risk of further fractures, said Willy M. Valencia, MD, a geriatrician-endocrinologist at the Cleveland Clinic. Apart from active daily living, he recommends several types of formal exercise to promote bone formation; increase muscle mass, strength, and flexibility; and improve endurance, balance, and gait. The National Institute on Aging outlines suitable exercise programs for seniors.

“These exercises will help reduce the risk of falling and to avoid more fractures,” he said. “Whether a patient has been exercising before the fracture or not, they may feel some reticence or reluctance to take up exercise afterwards because they’re afraid of having another fracture, but they should understand that their fracture risk increases if they remain sedentary. They should start slowly but they can’t be sitting all day.”

Even before it’s possible to exercise at the healing fracture site, added Dr. Rianon, its advisable to work other areas of the body. “Overall mobility is important, and exercising other parts of the body can stimulate strength and help prevent falling.”

In other postsurgical measures, a bone-friendly diet rich in calcium and vitamin D, as well as supplementation with these vital nutrients, is essential to lower the risk of falling.

Fall prevention is paramount, said Dr. Valencia. While exercise can improve, gait, balance, and endurance, logistical measures may also be necessary. Seniors may have to move to a one-floor domicile with no stairs to negotiate. At the very least, they need to fall-proof their daily lives by upgrading their eyeglasses and home lighting, eliminating obstacles and loose carpets, fixing bannisters, and installing bathroom handrails. Some may need assistive devices for walking, especially outdoors in slippery conditions.

At the end of the day, the role of the primary physician in screening for bone problems before fracture and postsurgical care is key. “Risk factors for osteoporosis and fracture risk must be added to the patient’s chart,” said Dr. Rianon. Added Dr. Moseley. “No matter how busy they are, my hope is that primary care physicians will not put patients’ bone health at the bottom of the clinical agenda.”

While half the fracture-prevention battle is getting people diagnosed with low bone density, nearly 80% of older Americans who suffer bone breaks are not tested or treated for osteoporosis. Fractures associated with aging and diminished bone mineral density exact an enormous toll on patients’ lives and cost the health care system billions of dollars annually according to Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. But current gaps in patient education and bone density screening are huge.

“It’s concerning that older patients at risk for fracture are often not screened to determine their risk factors contributing to osteoporosis and patients are not educated about fracture prevention,” said Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, an endocrinologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and chief of calcium and bone section, and professor of medicine, at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Furthermore, the majority of highest-risk women and men who do have fractures are not screened and they do not receive effective, [Food and Drug Administration]–approved therapies.”

Recent guidelines

Screening with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is recommended for all women at age 65 and all men at age 70. But the occasion of a fracture in an older person who has not yet met these age thresholds should prompt a bone density assessment.

“Doctors need to stress that one in two women and one in four men over age 50 will have a fracture in their remaining lifetimes,” Dr. LeBoff said. ”Primary care doctors play a critical role in ordering timely bone densitometry for both sexes.

If an older patient has been treated for a fracture, the main goal going forward is to prevent another one, for which the risk is highest in the 2 years after the incident fracture.”

According to Kendall F. Moseley, MD, clinical director of the division of endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, “Elderly patients need to understand that a fracture at their age is like a heart attack of the bone,” she said, adding that just as cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure and blood lipids are silent before a stroke or infarction, the bone thinning of old age is also silent.

Endocrinologist Jennifer J. Kelly, DO, director of the metabolic bone program and an associate professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington, said a fracture in anyone over age 50 that appears not to have resulted from a traumatic blow, is a compelling reason to order a DEXA exam.

Nahid J. Rianon, MBBS/MD, DrPH, assistant professor of the division of geriatric medicine at the UTHealth McGovern Medical School, Houston, goes further: “Any fracture in someone age 50 and older warrants screening for osteoporosis. And if the fracture is nontraumatic, that is by definition a clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis regardless of normal results on bone density tests and they should be treated medically. There are aspects of bone that we still can’t measure in the clinical setting.”

If DEXA is not accessible, fracture risk over the next 10 years can be evaluated based on multiple patient characteristics and medical history using the online FRAX calculator.

Just a 3% risk of hip fracture on FRAX is considered an indication to begin medical osteoporosis treatment in the United States regardless of bone density test results, Dr. Rianon said.

Fracture management

Whether a senior suffers a traumatic fracture or an osteoporosis-related fragility fracture, older age can impede the healing process in some. Senescence may also increase systemic proinflammatory status, according to Clark and colleagues, writing in Current Osteoporosis Reports.

They called for research to develop more directed treatment options for the elderly population.

Dr. Rianon noted that healing may also be affected by a decrease in muscle mass, which plays a role in holding the bone in place. “But it is still controversial how changing metabolic factors affect bone healing in the elderly.”

However, countered Dr. Kelly, fractures in elderly patients are not necessarily less likely to mend – if osteoporosis is not present. “Many heal very well – it really depends more upon their overall health and medical history. Whether or not a person requires surgery depends more upon the extent of the fracture and if the bone is able to align and heal appropriately without surgery.”

Fracture sites

Spine. According to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons the earliest and most frequent site of fragility fractures in the elderly is the spine. Most vertebral fracture pain improves within 3 months without specific treatment. A short period of rest, limited analgesic use, and possible back bracing may help as the fractures heal on their own. But if pain is severe and persistent, vertebral augmentation with percutaneous kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty may be an option. These procedures, however, can destabilize surrounding discs because of the greater thickness of the injected cement.

Hip. The most dangerous fractures occur in the hip. These carry at least a 20% risk of death in the first postoperative year and must be treated surgically. Those in the proximal femur, the head, or the femoral neck will usually need hip replacement, but if the break is farther down, it may be repaired with cement, screws, plates, and rods.

Distal radius. Outcomes of wrist fractures may be positive without surgical intervention, according to a recent retrospective analysis from Turkey by Yalin and colleagues. In a comparison of clinical outcomes in seniors aged 70-89 and assigned to cast immobilization or various surgical treatments for distal radius fractures, no statistically significant difference was found in patient-reported disability scores and range of motion values between casting and surgery in the first postoperative year.

Other sites. Fractures in the elderly are not uncommon in the shoulder, distal radius, cubitus, proximal humerus, and humerus. These fractures are often treated without surgery, but nevertheless signal a high risk for additional fractures.

Bone-enhancing medications

Even in the absence of diagnosed low bone density or osteoporosis, anabolic agents such as the synthetic human parathyroid hormones abaloparatide (Tymlos) and teriparatide (Forteo) may be used to help in some cases with a bad healing prognosis and may also be used for people undergoing surgeries such as a spinal fusion, but there are not clinical guidelines. “We receive referrals regularly for this treatment from our orthopedics colleagues, but it is considered an off-label use,” Dr. Kelly said.

The anabolics teriparatide and romosozumab (Evenity) have proved effective in lowering fractures in high-risk older women.

Post fracture

After recovering from a fracture, elderly people are strongly advised to make lifestyle changes to boost bone health and reduce risk of further fractures, said Willy M. Valencia, MD, a geriatrician-endocrinologist at the Cleveland Clinic. Apart from active daily living, he recommends several types of formal exercise to promote bone formation; increase muscle mass, strength, and flexibility; and improve endurance, balance, and gait. The National Institute on Aging outlines suitable exercise programs for seniors.

“These exercises will help reduce the risk of falling and to avoid more fractures,” he said. “Whether a patient has been exercising before the fracture or not, they may feel some reticence or reluctance to take up exercise afterwards because they’re afraid of having another fracture, but they should understand that their fracture risk increases if they remain sedentary. They should start slowly but they can’t be sitting all day.”

Even before it’s possible to exercise at the healing fracture site, added Dr. Rianon, its advisable to work other areas of the body. “Overall mobility is important, and exercising other parts of the body can stimulate strength and help prevent falling.”

In other postsurgical measures, a bone-friendly diet rich in calcium and vitamin D, as well as supplementation with these vital nutrients, is essential to lower the risk of falling.

Fall prevention is paramount, said Dr. Valencia. While exercise can improve, gait, balance, and endurance, logistical measures may also be necessary. Seniors may have to move to a one-floor domicile with no stairs to negotiate. At the very least, they need to fall-proof their daily lives by upgrading their eyeglasses and home lighting, eliminating obstacles and loose carpets, fixing bannisters, and installing bathroom handrails. Some may need assistive devices for walking, especially outdoors in slippery conditions.

At the end of the day, the role of the primary physician in screening for bone problems before fracture and postsurgical care is key. “Risk factors for osteoporosis and fracture risk must be added to the patient’s chart,” said Dr. Rianon. Added Dr. Moseley. “No matter how busy they are, my hope is that primary care physicians will not put patients’ bone health at the bottom of the clinical agenda.”

Pain mismanagement by the numbers

Despite my best efforts to cultivate acquaintances across a broader age group, my social circle still has the somewhat musty odor of septuagenarians. We try to talk about things beyond the weather and grandchildren but pain scenarios surface with unfortunate frequency. Arthritic joints ache, body parts wear out or become diseased and have to be removed or replaced. That stuff can hurt.

There are two pain-related themes that seem to crop up more frequently than you might expect. The first is the unfortunate side effects of opioid medication – most often gastric distress and vomiting, then of course there’s constipation. They seem so common that a good many of my acquaintances just plain refuse to take opioids when they have been prescribed postoperatively because of their vivid memories of the consequences or horror stories friends have told.

The second theme is the general annoyance with the damn “Please rate your pain from one to ten” request issued by every well-intentioned nurse. Do you mean the pain I am having right now, this second, or last night, or the average over the last day and a half? Or should I be comparing it with when I gave birth 70 years ago, or when I stubbed my toe getting out of the shower last week? And then what are you going to do with my guesstimated number?

It may surprise some of you that 40 years ago there wasn’t a pain scale fetish. But a few observant health care professionals realized that many of our patients were suffering because we weren’t adequately managing their pain. In postoperative situations this was slowing recovery and effecting outcomes. Like good pseudoscientists, they realized that we should first quantify the pain and the notion that no pain should go unrated came into being. Nor should pain go untreated, which is too frequently interpreted as meaning unmedicated.

For example a systematic review of 61 studies of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) published in the journal Pediatric Rheumatology found that there was positive relationship between pain and a child’s belief that pain causes harm, disability, and lack of control. Not surprisingly, stress was also associated with pain intensity.

It is a long paper and touches on numerous other associations of varying degrees of strength between parental, social, and other external factors. But, in general, they were not as consistent as those related to a child’s beliefs.

Before, or at least at the same time, we treat a patient’s pain, we should learn more about that patient – his or her concerns, beliefs, and stressors. You and I may have exactly the same hernia operation, but if you have a better understanding of why you are going to feel uncomfortable after the surgery, and understand that not every pain is the result of a complication, I suspect you are more likely to complain of less pain.

The recent JIA study doesn’t claim to suggest therapeutic methods. However, one wonders what the result would be if we could somehow alter a patient’s belief system so that he or she no longer sees pain as always harmful, nor does the patient see himself or herself as powerless to do anything about the pain. To do this experiment we must follow up our robotic request to “rate your pain” with a dialogue in which we learn more about the patient. Which means probing believes, fears, and stressors.

You can tell me this exercise would be unrealistic and time consuming. But I bet in the long run it will save time. Even if it doesn’t it is the better way to manage pain.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Despite my best efforts to cultivate acquaintances across a broader age group, my social circle still has the somewhat musty odor of septuagenarians. We try to talk about things beyond the weather and grandchildren but pain scenarios surface with unfortunate frequency. Arthritic joints ache, body parts wear out or become diseased and have to be removed or replaced. That stuff can hurt.

There are two pain-related themes that seem to crop up more frequently than you might expect. The first is the unfortunate side effects of opioid medication – most often gastric distress and vomiting, then of course there’s constipation. They seem so common that a good many of my acquaintances just plain refuse to take opioids when they have been prescribed postoperatively because of their vivid memories of the consequences or horror stories friends have told.

The second theme is the general annoyance with the damn “Please rate your pain from one to ten” request issued by every well-intentioned nurse. Do you mean the pain I am having right now, this second, or last night, or the average over the last day and a half? Or should I be comparing it with when I gave birth 70 years ago, or when I stubbed my toe getting out of the shower last week? And then what are you going to do with my guesstimated number?

It may surprise some of you that 40 years ago there wasn’t a pain scale fetish. But a few observant health care professionals realized that many of our patients were suffering because we weren’t adequately managing their pain. In postoperative situations this was slowing recovery and effecting outcomes. Like good pseudoscientists, they realized that we should first quantify the pain and the notion that no pain should go unrated came into being. Nor should pain go untreated, which is too frequently interpreted as meaning unmedicated.

For example a systematic review of 61 studies of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) published in the journal Pediatric Rheumatology found that there was positive relationship between pain and a child’s belief that pain causes harm, disability, and lack of control. Not surprisingly, stress was also associated with pain intensity.

It is a long paper and touches on numerous other associations of varying degrees of strength between parental, social, and other external factors. But, in general, they were not as consistent as those related to a child’s beliefs.

Before, or at least at the same time, we treat a patient’s pain, we should learn more about that patient – his or her concerns, beliefs, and stressors. You and I may have exactly the same hernia operation, but if you have a better understanding of why you are going to feel uncomfortable after the surgery, and understand that not every pain is the result of a complication, I suspect you are more likely to complain of less pain.

The recent JIA study doesn’t claim to suggest therapeutic methods. However, one wonders what the result would be if we could somehow alter a patient’s belief system so that he or she no longer sees pain as always harmful, nor does the patient see himself or herself as powerless to do anything about the pain. To do this experiment we must follow up our robotic request to “rate your pain” with a dialogue in which we learn more about the patient. Which means probing believes, fears, and stressors.

You can tell me this exercise would be unrealistic and time consuming. But I bet in the long run it will save time. Even if it doesn’t it is the better way to manage pain.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Despite my best efforts to cultivate acquaintances across a broader age group, my social circle still has the somewhat musty odor of septuagenarians. We try to talk about things beyond the weather and grandchildren but pain scenarios surface with unfortunate frequency. Arthritic joints ache, body parts wear out or become diseased and have to be removed or replaced. That stuff can hurt.

There are two pain-related themes that seem to crop up more frequently than you might expect. The first is the unfortunate side effects of opioid medication – most often gastric distress and vomiting, then of course there’s constipation. They seem so common that a good many of my acquaintances just plain refuse to take opioids when they have been prescribed postoperatively because of their vivid memories of the consequences or horror stories friends have told.

The second theme is the general annoyance with the damn “Please rate your pain from one to ten” request issued by every well-intentioned nurse. Do you mean the pain I am having right now, this second, or last night, or the average over the last day and a half? Or should I be comparing it with when I gave birth 70 years ago, or when I stubbed my toe getting out of the shower last week? And then what are you going to do with my guesstimated number?

It may surprise some of you that 40 years ago there wasn’t a pain scale fetish. But a few observant health care professionals realized that many of our patients were suffering because we weren’t adequately managing their pain. In postoperative situations this was slowing recovery and effecting outcomes. Like good pseudoscientists, they realized that we should first quantify the pain and the notion that no pain should go unrated came into being. Nor should pain go untreated, which is too frequently interpreted as meaning unmedicated.

For example a systematic review of 61 studies of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) published in the journal Pediatric Rheumatology found that there was positive relationship between pain and a child’s belief that pain causes harm, disability, and lack of control. Not surprisingly, stress was also associated with pain intensity.

It is a long paper and touches on numerous other associations of varying degrees of strength between parental, social, and other external factors. But, in general, they were not as consistent as those related to a child’s beliefs.

Before, or at least at the same time, we treat a patient’s pain, we should learn more about that patient – his or her concerns, beliefs, and stressors. You and I may have exactly the same hernia operation, but if you have a better understanding of why you are going to feel uncomfortable after the surgery, and understand that not every pain is the result of a complication, I suspect you are more likely to complain of less pain.

The recent JIA study doesn’t claim to suggest therapeutic methods. However, one wonders what the result would be if we could somehow alter a patient’s belief system so that he or she no longer sees pain as always harmful, nor does the patient see himself or herself as powerless to do anything about the pain. To do this experiment we must follow up our robotic request to “rate your pain” with a dialogue in which we learn more about the patient. Which means probing believes, fears, and stressors.

You can tell me this exercise would be unrealistic and time consuming. But I bet in the long run it will save time. Even if it doesn’t it is the better way to manage pain.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Knee pain and injury: When is a surgical consult needed?

Evidence supports what family physicians know to be true: Knee pain is an exceedingly common presenting problem in the primary care office. Estimates of lifetime incidence reach as high as 54%,1 and the prevalence of knee pain in the general population is increasing.2 Knee disability can result from acute or traumatic injuries as well as chronic, degenerative conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA). The decision to pursue orthopedic consultation for a particular injury or painful knee condition can be challenging. To address this, we highlight specific knee diagnoses known to cause pain, with the aim of describing which conditions likely will necessitate surgical consultation—and which won’t.

Acute or nondegenerative knee injuries and pain

Acute knee injuries range in severity from simple contusions and sprains to high-energy, traumatic injuries with resulting joint instability and potential neurovascular compromise. While conservative treatment often is successful for many simple injuries, surgical management—sometimes urgently or emergently—is needed in other cases, as will be detailed shortly.

Neurovascular injury associated with knee dislocations

Acute neurovascular injuries often require emergent surgical intervention. Although rare, tibiofemoral (knee) dislocations pose a significant challenge to the clinician in both diagnosis and management. The reported frequency of popliteal artery injury or rupture following a dislocation varies widely, with rates ranging from 5% to 64%, according to older studies; more recent data, however, suggest the rate is actually as low as 3.3%.3

Immediate immobilization and emergency department transport for monitoring, orthopedics consultation, and vascular studies or vascular surgery consultation is recommended in the case of a suspected knee dislocation. In one cross-sectional cohort study, the surgical management of knee dislocations yielded favorable outcomes in > 75% of cases.5

Tibial plateau fracture

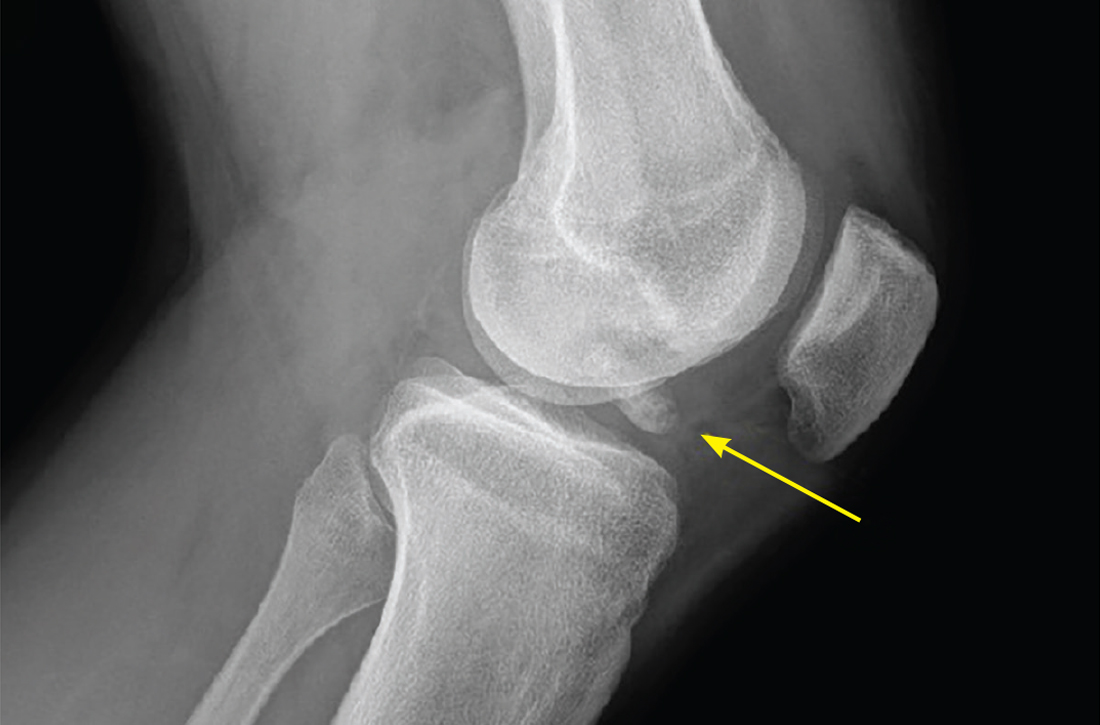

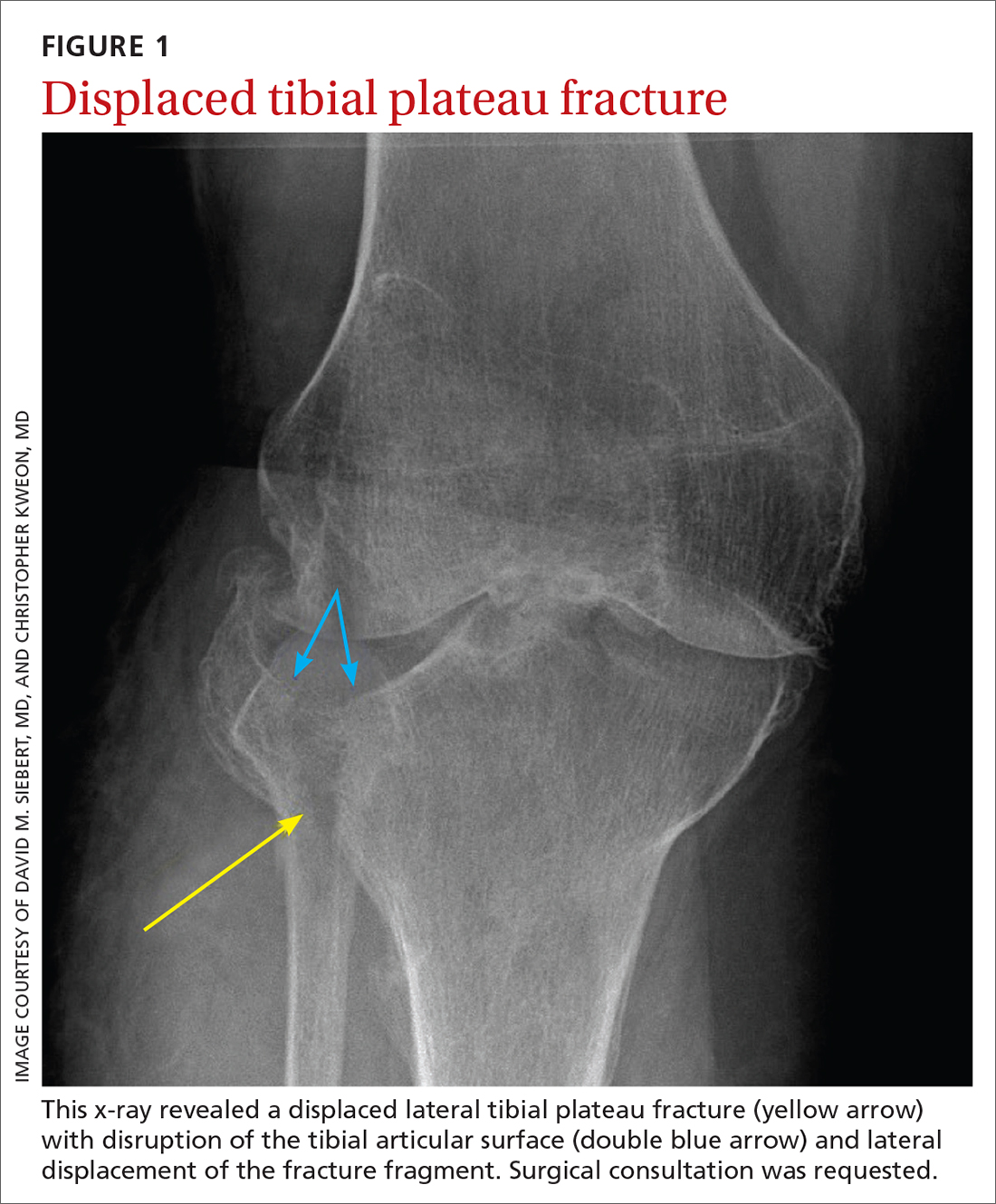

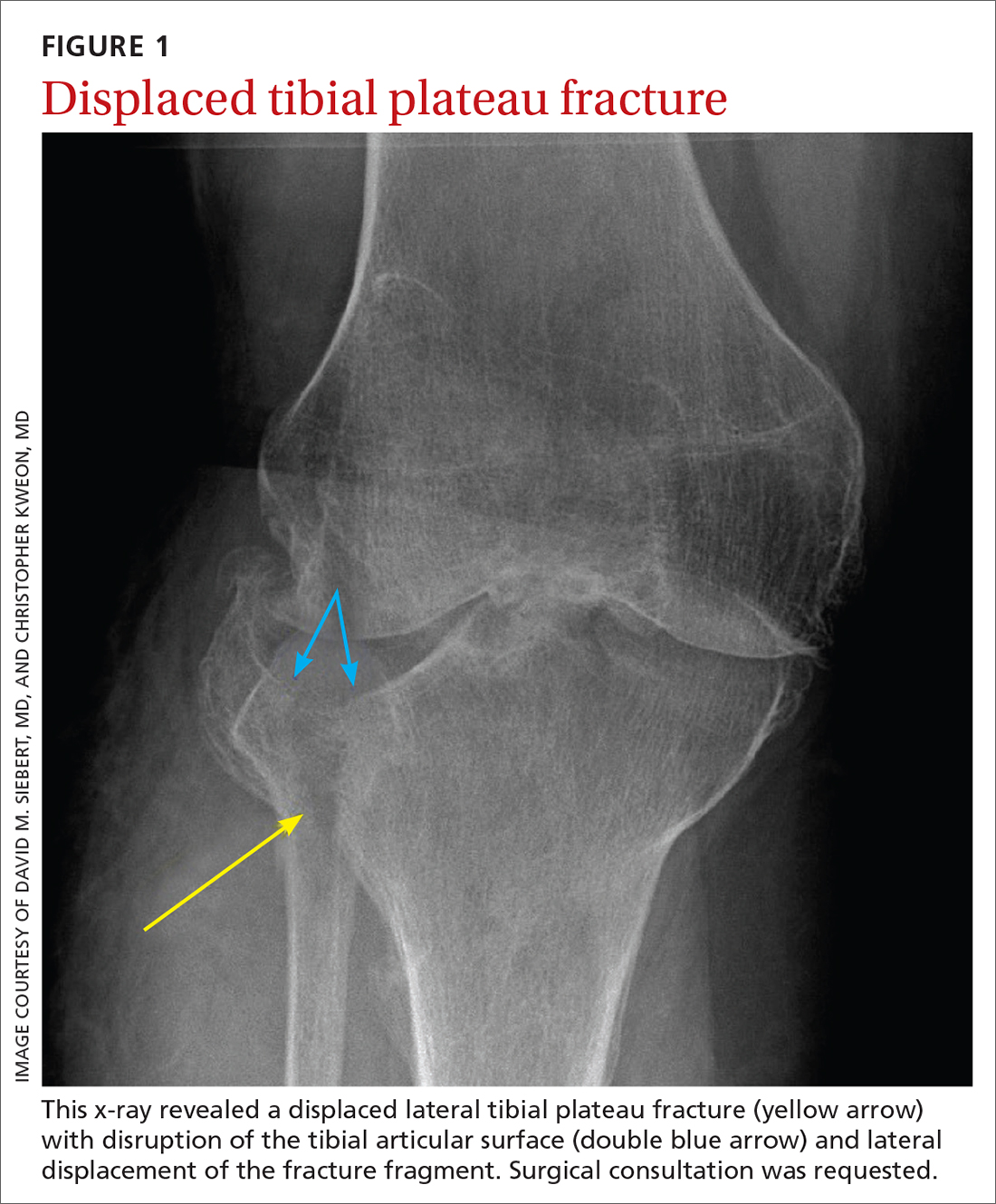

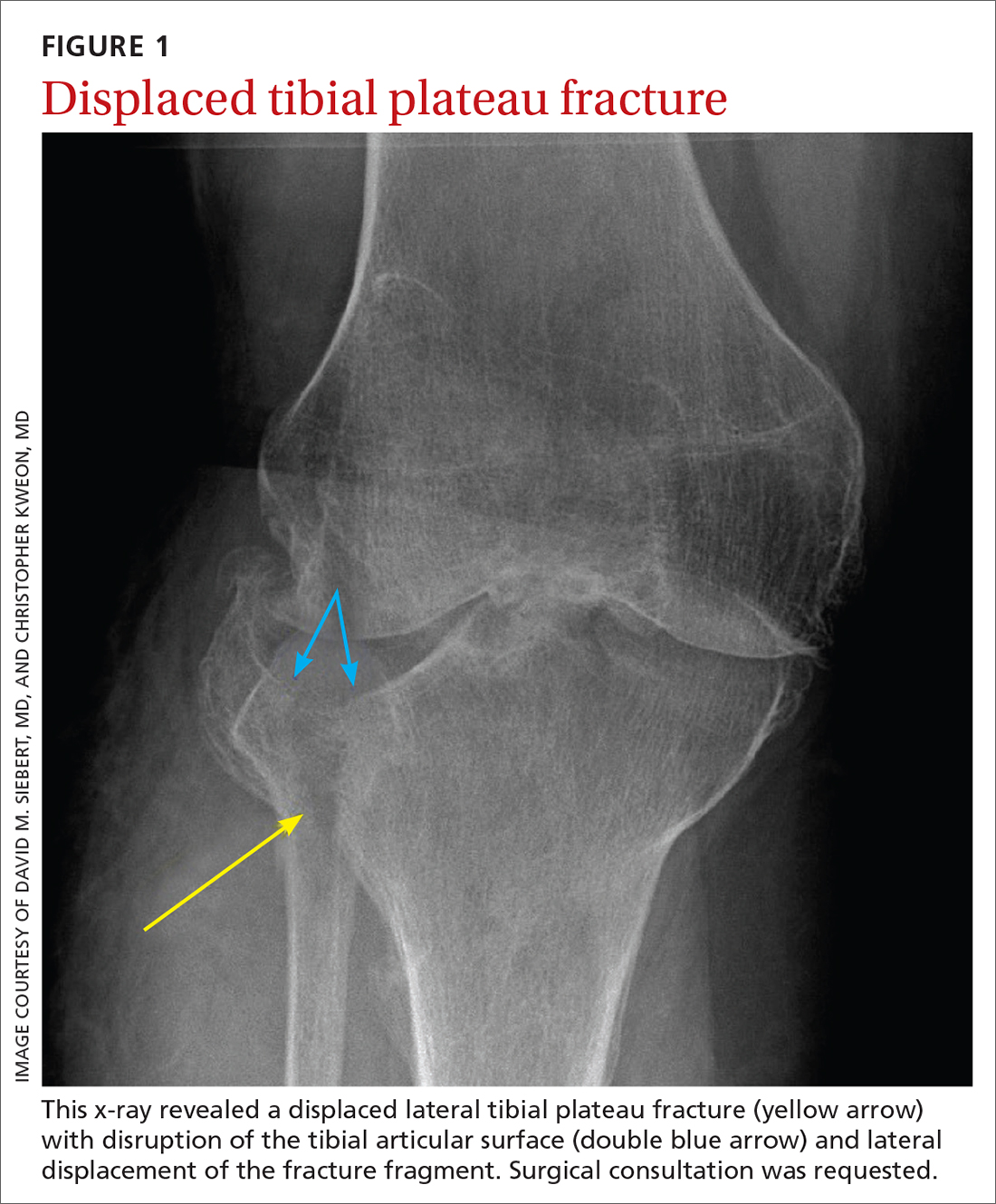

This fracture often occurs as a result of high-energy trauma, such as contact sports or motor vehicle accidents, and is characterized by a proximal tibial fracture line with extension to the articular surface. X-rays often are sufficient for initial diagnosis. Computed tomography can help rule out a fracture line when clinical suspicion is high and x-rays are nondiagnostic. As noted earlier, any suggestion of neurovascular compromise on physical exam requires an emergent orthopedic surgeon consultation for a possible displaced and unstable (or more complex) injury (FIGURE 1).6-8

Nondisplaced tibial plateau fractures without supraphysiologic ligamentous laxity on valgus or varus stress testing can be managed safely with protection and early mobilization, gradual progression of weight-bearing, and serial x-rays to ensure fracture healing and stability.

Gross joint instability identified by positive valgus or varus stress testing, positive anterior or posterior drawer testing, or patient inability to tolerate these maneuvers due to pain similarly should raise suspicion for a more significant fracture at risk for concurrent neurovascular injury. Acute compartment syndrome also is a known complication of tibial plateau fractures and similarly requires emergent operative management. Urgent surgical consultation is recommended for fractures with displaced fracture fragments, tibial articular surface step-off or depression, fractures with concurrent joint laxity, or medial plateau fractures.6-8

Continue to: Patella fractures

Patella fractures

These fractures occur as a direct blow to the front of the knee, such as falling forward onto a hard surface, or indirectly due to a sudden extreme eccentric contraction of the quadriceps muscle. Nondisplaced fractures with an intact knee extension mechanism, which is examined via a supine straight-leg raise or seated knee extension, are managed with weight-bearing as tolerated in strict immobilization in full extension for 4 to 6 weeks, with active range-of-motion and isometric quadriceps exercises beginning in 1 to 2 weeks. Serial x-rays also are obtained to ensure fracture displacement does not occur during the rehabilitation process.9

High-quality evidence guiding follow-up care and comparing outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of patella fractures is lacking, and studies comparing different surgical techniques are of lower methodological quality.10 Nevertheless, displaced or comminuted patellar fractures are referred urgently to orthopedic surgical care for fixation, as are those with concurrent loose bodies, chondral surface injuries or articular step-off, or osteochondral fractures.9 Inability to perform a straight-leg raise (ie, clinical loss of the knee extension mechanism) suggests a fracture under tension that likely also requires surgical fixation for successful recovery. Neurovascular injuries are unlikely in most patellar fractures but would require emergent surgical consultation.9

Ligamentous injury

Tibiofemoral joint laxity occurs as a result of ligamentous injury, with or without tibial plateau fracture. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) comprise the 4 main ligaments of the knee. The ACL resists anterior tibial translation and rotational forces, while the PCL resists posterior tibial translation. The MCL and LCL resist valgus and varus stress, respectively.

Ligament injuries are classified as Grades 1 to 311:

- Grade 1 sprains. The ligament is stretched, but there is no macroscopic tearing; joint stability is maintained.

- Grade 2 sprains. There are partial macroscopic ligament tears. There is joint laxity due to the partial loss of the ligament’s structural integrity.

- Grade 3 sprains. The ligament is fully avulsed or ruptured with resultant gross joint instability.

Continue to: ACL tears

ACL tears occur most commonly via a noncontact event, as when an individual plants their foot and suddenly changes direction during sport or other physical activity. Treatment hinges on patient activity levels and participation in sports. Patients who do not plan to engage in athletic movements (that require changes in direction or planting and twisting) and who otherwise maintain satisfactory joint stability during activities of daily living may elect to defer or even altogether avoid surgical reconstruction of isolated ACL tears. One pair of studies demonstrated equivalent outcomes in surgical and nonsurgical management in 121 young, nonelite athletes at 2- and 5-year follow-up, although the crossover from the nonsurgical to surgical groups was high.12,13 Athletes who regain satisfactory function and stability nonoperatively can defer surgical intervention. However, the majority of active patients and athletes will require surgical ACL reconstruction to return to pre-injury functional levels.14

PCL sprains occur as a result of sudden posteriorly directed force on the tibia, such as when the knee is hyperextended or a patient falls directly onto a flexed knee. Patients with Grade 1 and 2 isolated sprains generally will recover with conservative care, as will patients with some Grade 3 complete tears that do not fully compromise joint stability. However, high-grade PCL injuries often are comorbid with posterolateral corner or other injuries, leading to a higher likelihood of joint instability and thus the need for surgical intervention for the best chance at an optimal outcome.15

MCL sprain. Surgical management is not required in an isolated Grade 1 or 2 MCL sprain, as the hallmarks of recovery—return of joint stability, knee strength and range of motion, and pain reduction—can be achieved successfully with conservative management. Isolated Grade 3 MCL sprains are also successfully managed nonoperatively16 except in specific cases, such as a concurrent large avulsion fracture.17

LCL sprain. Similarly, isolated Grade 1 and 2 LCL sprains generally do not require surgical intervention. However, Grade 3 LCL injuries usually do, as persistent joint instability and poor functional outcomes are more common with nonsurgical management.18-20 Additionally, high-grade LCL injuries frequently manifest with comorbid meniscus injuries or sprains of the posterolateral corner of the knee, a complex anatomic structure that provides both static and dynamic tibiofemoral joint stability. Surgical repair or reconstruction of the posterolateral corner frequently is necessary for optimal functional outcomes.21

Multiligamentous sprains frequently lead to gross joint instability and necessitate orthopedic surgeon consultation to determine the best treatment plan; this should be done emergently if neurovascular compromise is suspected. A common injury combination is simultaneous ACL and MCL sprains with or without meniscus injury. In these cases, some surgeons will choose to defer ACL reconstruction until after MCL healing is achieved. This allows the patient to regain valgus stability of the joint prior to performing ACL reconstruction to regain rotational and anterior stability.20

Continue to: Patellar dislocations

Patellar dislocations represent a relatively common knee injury in young active patients, often occurring in a noncontact fashion when a valgus force is applied to an externally rotated and planted lower leg.

Major tendon rupture

Patellar tendon ruptures occur when a sudden eccentric force is applied to the knee, such as when landing from a jump with the knee flexed. Patellar tendon ruptures frequently are clinically apparent, with patients demonstrating a high-riding patella and loss of active knee extension. Quadriceps tendon ruptures often result from a similar injury mechanism in older patients, with a similar loss of active knee extension and a palpable gap superior to the patella.24

Partial tears in patients who can maintain full extension of the knee against gravity are treated nonoperatively, but early surgical repair is indicated for complete quadriceps or patellar tendon ruptures to achieve optimal outcomes.

Even with prompt treatment, return to sport is not guaranteed. According to a recent systematic review, athletes returned to play 88.9% and 89.8% of the time following patellar and quadriceps tendon repairs, respectively. However, returning to the same level of play was less common and achieved 80.8% (patellar tendon repair) and 70% (quadriceps tendon repair) of the time. Return-to-work rates were higher, at 96% for both surgical treatments.29

Locked knee and acute meniscus tears in younger patients

In some acute knee injuries, meniscus tears, loose cartilage bodies or osteochondral defects, or other internal structures can become interposed between the femoral and tibial surfaces, preventing both active and passive knee extension. Such injuries are often severely painful and functionally debilitating. While manipulation under anesthesia can acutely restore joint function,30 diagnostic and therapeutic arthroscopy often is pursued for definitive treatment.31 Compared to the gold standard of diagnostic arthroscopy, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) carries positive and negative predictive values of 85% and 77%, respectively, in identifying or ruling out the anatomic structure responsible for a locked knee. 32 As such,

Continue to: Depending on the location...

Depending on the location, size, and shape of an acute meniscus tear in younger patients, surgical repair may be an option to preserve long-term joint function. In one case series of patients younger than 20 years, 62% of meniscus repairs yielded good outcomes after a mean follow-up period of 16.8 years.33

Osteochondritis dissecans

Osteochondritis dissecans is characterized by subchondral bone osteonecrosis that most often occurs in pediatric patients, potentially causing the separation of a fragment of articular cartilage and subchondral bone into the joint space (FIGURE 2). In early stages, nonoperative treatment consisting of prolonged rest followed by physical therapy to gradually return to activity is recommended to prevent small, low-grade lesions from progressing to unstable or separated fragments. Arthroscopy, which consists of microfracture or other surgical resurfacing techniques to restore joint integrity, is pursued in more advanced cases of unstable or separated fragments.

High-quality data guiding the management of osteochondritis dissecans are lacking, and these recommendations are based on consensus guidelines.34

Septic arthritis

Septic arthritis is a medical emergency caused by the hematogenous spread of microorganisms, most often staphylococci and streptococci species. Less commonly, it arises from direct inoculation through an open wound or, rarely, iatrogenically following a joint injection procedure. Clinical signs of septic arthritis include joint pain, joint swelling, and fever. Passive range of motion of the joint is often severely painful. Synovial fluid studies consistent with septic arthritis include an elevated white blood cell count greater than 25,000/mcL with polymorphonuclear cell predominance.35 The knee accounts for more than 50% of septic arthritis cases, and surgical drainage usually is required to achieve infection source control and decrease morbidity and mortality due to destruction of articular cartilage when treatment is delayed.36

Chronic knee injuries and pain

Surgical intervention for chronic knee injuries and pain generally is considered when patients demonstrate significant functional impairment and persistent symptoms despite pursuing numerous nonsurgical treatment options. A significant portion of chronic knee pain is due to degenerative processes such as OA or meniscus injuries, or tears without a history of trauma that do not cause locking of the knee. Treatments for degenerative knee pain include supervised exercise, physical therapy, bracing, offloading with a cane or other equipment, topical or oral anti-inflammatories or analgesics, and injectable therapies such as intra-articular corticosteroids.37

Continue to: Other common causes...

Other common causes of chronic knee pain include chronic tendinopathy or biomechanical syndromes such as patellofemoral pain syndrome or iliotibial band syndrome. Surgical treatment of these conditions is pursued in select cases and only after exhausting nonoperative treatment programs, as recommended by international consensus statements,38 societal guidelines,39 and expert opinion.40 High-quality data on the effectiveness, or ineffectiveness, of surgical intervention for these conditions are lacking.

Despite being one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in the United States,41 arthroscopic partial meniscectomy treatment of degenerative meniscus tears does not lead to improved outcomes compared to nonsurgical management, according to multiple recent studies.42-45 Evidence does not support routine arthroscopic intervention for degenerative meniscus tears or OA,42 and recent guidelines recommend against it46 or to pursue it only after nonsurgical treatments have failed.37

Surgical management of degenerative knee conditions generally consists of partial or total arthroplasty and is similarly considered after failure of conservative measures. Appropriate use criteria that account for multiple clinical and patient factors are used to enhance patient selection for the procedure.47

Takeaways

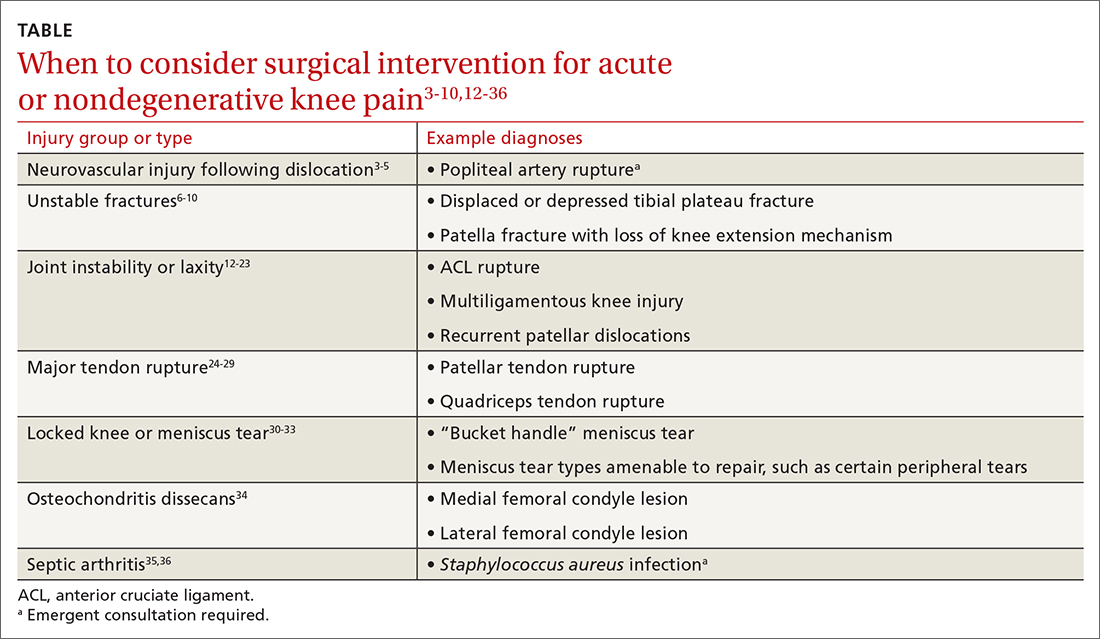

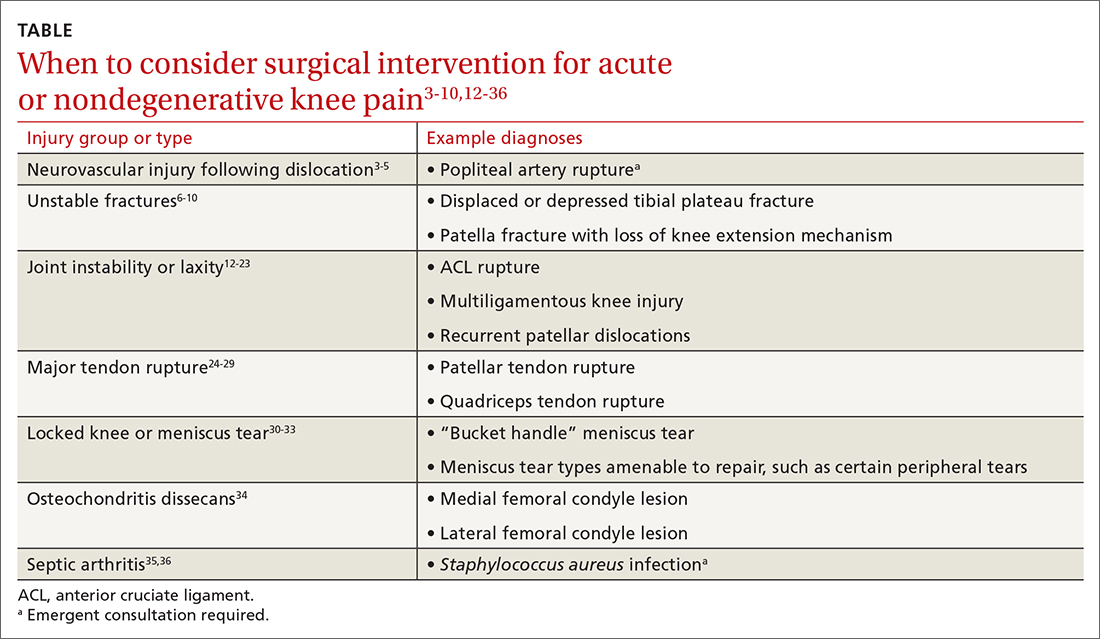

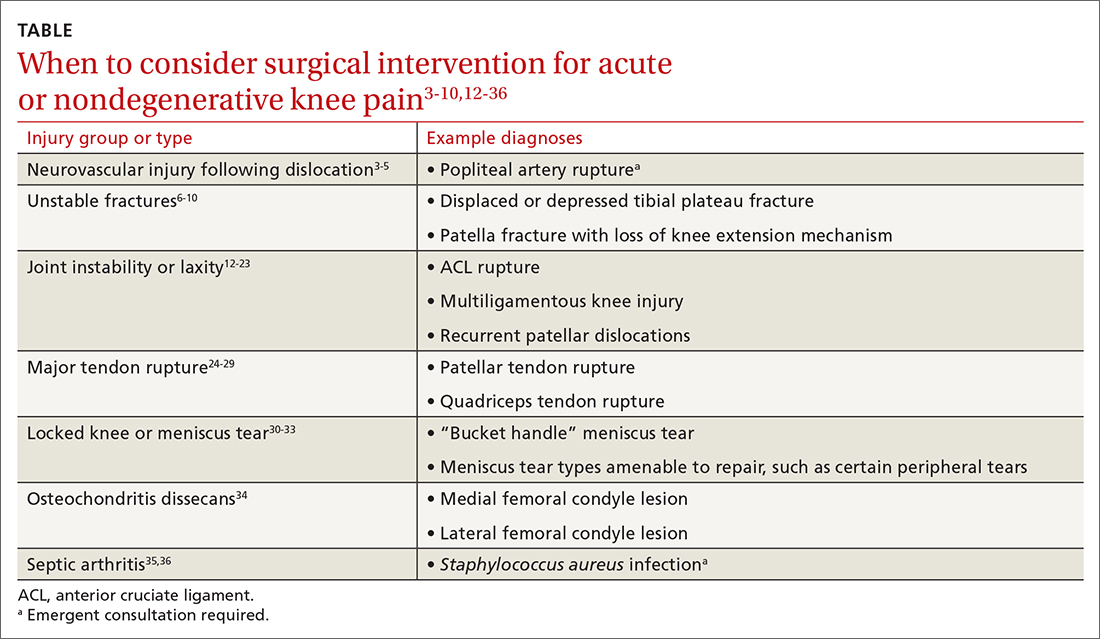

Primary care clinicians will treat patients sustaining knee injuries and see many patients with knee pain in the outpatient setting. Treatment options vary considerably depending on the underlying diagnosis and resulting functional losses. Several categories of clinical presentation, including neurovascular injury, unstable or displaced fractures, joint instability, major tendon rupture, significant mechanical symptoms such as a locked knee, certain osteochondral injuries, and septic arthritis, likely or almost always warrant surgical consultation (TABLE3-10,12-36). Occasionally, as in the case of neurovascular injury or septic arthritis, such consultation should be emergent.

CORRESPONDENCE

David M. Siebert, MD, Sports Medicine Center at Husky Stadium, 3800 Montlake Boulevard NE, Seattle, WA 98195; siebert@uw.edu

1. Baker P, Reading I, Cooper C, et al. Knee disorders in the general population and their relation to occupation. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:794-797. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.10.794

2. Nguyen UD, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, et al. Increasing prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: survey and cohort data. Ann Intern Med. 20116;155:725-732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00004

3. Natsuhara KM, Yeranosian MG, Cohen JR, et al. What is the frequency of vascular injury after knee dislocation? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2615-2620. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3566-1

4. Seroyer ST, Musahl V, Harner CD. Management of the acute knee dislocation: the Pittsburgh experience. Injury. 2008;39:710-718. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.11.022

5. Sinan SM, Elsoe R, Mikkelsen C, et al. Clinical, functional, and patient-reported outcome of traumatic knee dislocations: a retrospective cohort study of 75 patients with 6.5-year follow up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;143:2589-2597. doi: 10.1007/s00402-022-04578-z

6. Schatzker J, Kfuri M. Revisiting the management of tibial plateau fractures. Injury. 2022;53:2207-2218. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2022.04.006

7. Rudran B, Little C, Wiik A, et al. Tibial plateau fracture: anatomy, diagnosis and management. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81:1-9. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2020.0339

8. Tscherne H, Lobenhoffer P. Tibial plateau fractures: management and expected results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):87-100.

9. Melvin JS, Mehta S. Patellar fractures in adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:198-207. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201104000-00004

10. Filho JS, Lenza M, Tamaoki MJ, et al. Interventions for treating fractures of the patella in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2:CD009651. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009651.pub3

11. Palmer W, Bancroft L, Bonar F, et al. Glossary of terms for musculoskeletal radiology. Skeletal Radiol. 2020;49(suppl 1):1-33. doi: 10.1007/s00256-020-03465-1

12. Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, et al. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:331-342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797

13. Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, et al. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomized trial. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f232

14. Diermeier TA, Rothrauff BB, Engebretsen L, et al; Panther Symposium ACL Treatment Consensus Group. Treatment after anterior cruciate ligament injury: Panther Symposium ACL Treatment Consensus Group. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55:14-22. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102200

15. Bedi A, Musahl V, Cowan JB. Management of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: an evidence-based review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:277-289. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00326

16. Edson CJ. Conservative and postoperative rehabilitation of isolated and combined injuries of the medial collateral ligament. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2006;14:105-110. doi: 10.1097/01.jsa.0000212308.32076.f2

17. Vosoughi F, Dogahe RR, Nuri A, et al. Medial collateral ligament injury of the knee: a review on current concept and management. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2021;9:255-262. doi: 10.22038/abjs.2021.48458.2401

18. Kannus P. Nonoperative treatment of grade II and III sprains of the lateral ligament compartment of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:83-88. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700114

19. Krukhaug Y, Mølster A, Rodt A, et al. Lateral ligament injuries of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:21-25. doi: 10.1007/s001670050067

20. Grawe B, Schroeder AJ, Kakazu R, et al. Lateral collateral ligament injury about the knee: anatomy, evaluation, and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018 15;26:e120-127. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00028

21. Ranawat A, Baker III CL, Henry S, et al. Posterolateral corner injury of the knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:506-518.

22. Palmu S, Kallio PE, Donell ST, et al. Acute patellar dislocation in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:463-470. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00072

23. Cohen D, Le N, Zakharia A, et al. MPFL reconstruction results in lower redislocation rates and higher functional outcomes than rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022;30:3784-3795. doi: 10.1007/s00167-022-07003-5

24. Siwek CW, Rao JP. Ruptures of the extensor mechanism of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:932-937.

25. Konrath GA, Chen D, Lock T, et al. Outcomes following repair of quadriceps tendon ruptures. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:273-279. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199805000-00010

26. Rasul Jr. AT, Fischer DA. Primary repair of quadriceps tendon ruptures: results of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(289):205-207.