User login

A review of the latest USPSTF recommendations

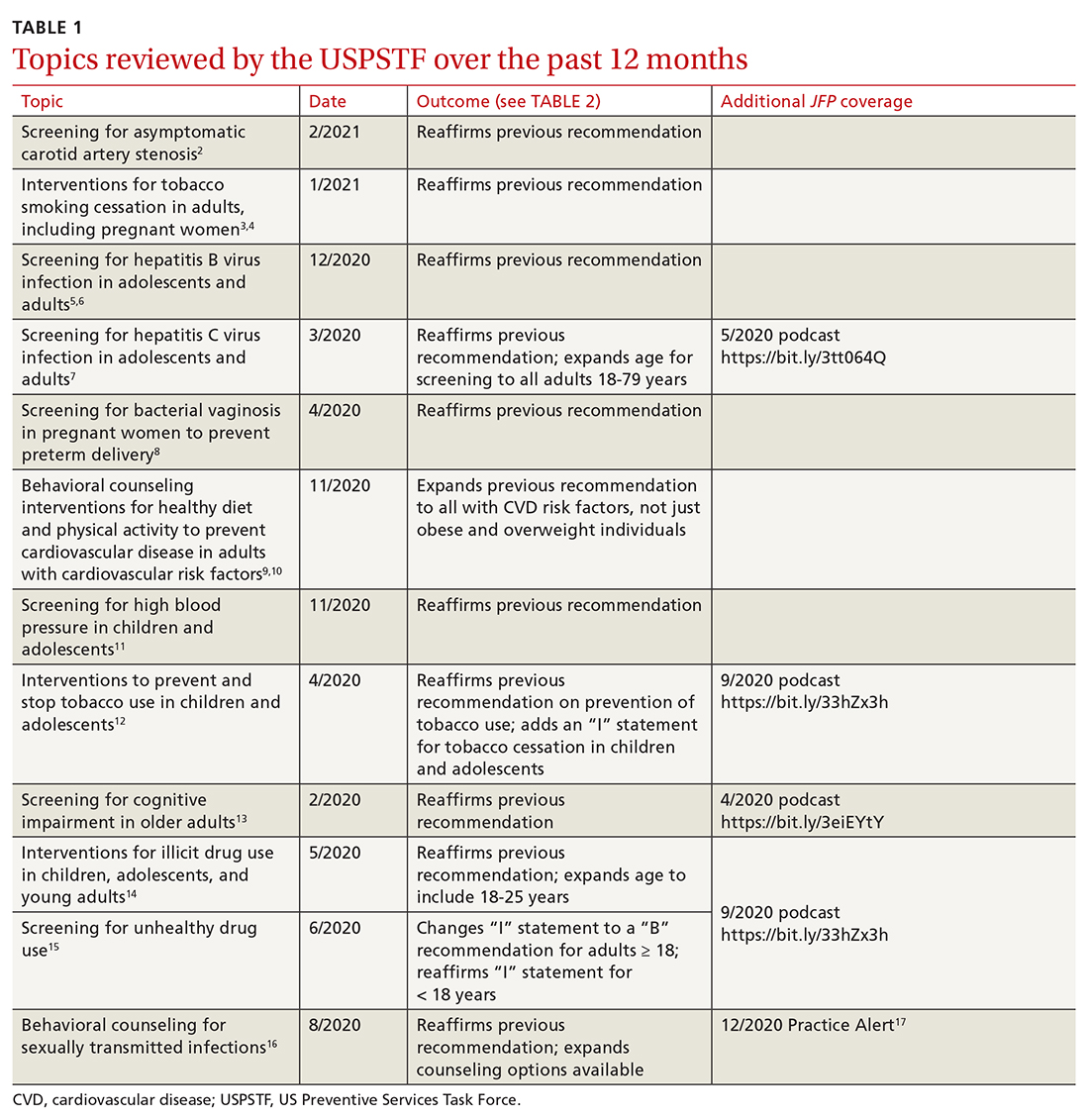

Since the last Practice Alert update on recommendations made by the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 the Task Force has completed work on 12 topics (TABLE 1).2-17 Five of these topics have been discussed in JFP audio recordings, and the links are provided in TABLE 1.

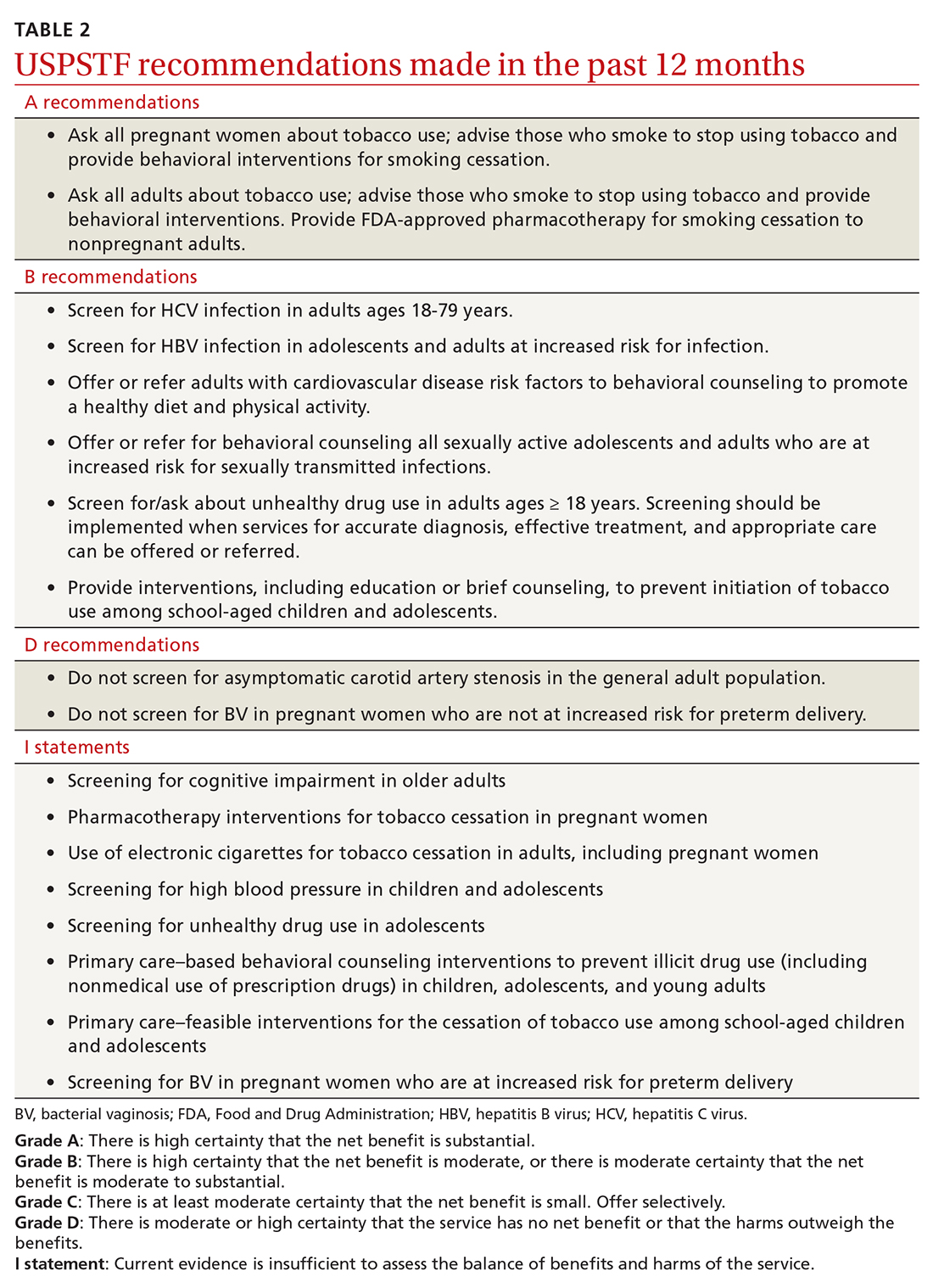

This latest Task Force endeavor resulted in 18 recommendations (TABLE 2), all of which reaffirm previous recommendations on these topics and expand the scope of 2. There were 2 “A” recommendations, 6 “B” recommendations, 2 “D” recommendations, and 8 “I” statements, indicating that there was insufficient evidence to assess effectiveness or harms. The willingness to make “I” statements when there is little or no evidence on the intervention being assessed distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline committees.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis

One of the “D” recommendations this past year reaffirms the prior recommendation against screening for carotid artery stenosis in asymptomatic adults—ie, those without a history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or neurologic signs or symptoms that might be caused by carotid artery stenosis.2 The screening tests the Task Force researched included carotid duplex ultrasonography (DUS), magnetic resonance angiography, and computed tomography angiography. The Task Force did not look at the value of auscultation for carotid bruits because it has been proven to be inaccurate and they do not consider it to be a useful screening tool.

The Task Force based its “D” recommendation on a lack of evidence for any benefit in detecting asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, and on evidence that screening can lead to harms through false-positive tests and potential complications from carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery angioplasty and stenting. In its clinical considerations, the Task Force emphasized the primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease by focusing on the following actions:

- screening for high blood pressure in adults

- encouraging tobacco smoking cessation in adults

- promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with cardiovascular risk factors

- recommending aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer

- advising statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults ages 45 to 75 years who have 1 or more risk factors (hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and those with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event of 10% or greater.

This “D” recommendation differs from recommendations made by other professional organizations, some of which recommend testing with DUS for asymptomatic patients with a carotid bruit, and others that recommend DUS screening in patients with multiple risk factors for stroke and in those with known peripheral artery disease or other cardiovascular disease.18,19

Smoking cessation in adults

Smoking tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, causing about 480,000 deaths annually.3 Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of complications including miscarriage, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and placental abruption.

The Task Force published recommendations earlier this year advising all clinicians to ask all adult patients about tobacco use; and, for those who smoke, to provide (or refer them to) smoking cessation behavioral therapy. The Task Force also recommends prescribing pharmacotherapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smoking cessation for nonpregnant adults. (There is a lack of information to assess the harms and benefits of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy during pregnancy.)

Continue to: FDA-approved medications...

FDA-approved medications for treating tobacco smoking dependence are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion hydrochloride, and varenicline.3 NRT is available in transdermal patches, lozenges, gum, inhalers, and nasal sprays.

In addition, the Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of e-cigarettes when used as a method of achieving smoking cessation: “Few randomized trials have evaluated the effectiveness of e-cigarettes to increase tobacco smoking cessation in nonpregnant adults, and no trials have evaluated e-cigarettes for tobacco smoking cessation in pregnant persons.”4

Hepatitis B infection screening

The Task Force reaffirmed a previous recommendation to screen for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection only in adults who are at high risk,5 rather than universal screening that it recommends for hepatitis C virus infection (HCV).7 (See: https://bit.ly/3tt064Q). The Task Force has a separate recommendation to screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B at the first prenatal visit.6

Those at high risk for hepatitis B who should be screened include individuals born in countries or regions of the world with a hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence ≥ 2% and individuals born in the United States who have not received HBV vaccine and whose parents were born in regions with an HBsAg prevalence ≥ 8%.5 (A table listing countries with HBsAg ≥ 8%—as well as those in lower prevalence categories—is included with the recommendation.5)

HBV screening should also be offered to other high-risk groups that have a prevalence of positive HBsAg ≥ 2%: those who have injected drugs in the past or are currently injecting drugs; men who have sex with men; individuals with HIV; and sex partners, needle-sharing contacts, and household contacts of people known to be HBsAg positive.5

Continue to: It is estimated that...

It is estimated that > 860,000 people in the United States have chronic HBV infection and that close to two-thirds of them are unaware of their infection.5 The screening test for HBV is highly accurate; sensitivity and specificity are both > 98%.5 While there is no direct evidence that screening, detecting, and treating asymptomatic HBV infection reduces morbidity and mortality, the Task Force felt that the evidence for improvement in multiple outcomes in those with HBV when treated with antiviral regimens was sufficient to support the recommendation.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

While bacterial vaginosis (BV) is associated with a two-fold risk of preterm delivery, treating BV during pregnancy does not seem to reduce this risk, indicating that some other variable is involved.8 In addition, studies that looked at screening for, and treatment of, asymptomatic BV in pregnant women at high risk for preterm delivery (defined primarily as those with a previous preterm delivery) have shown inconsistent results. There is the potential for harm in treating BV in pregnancy, chiefly involving gastrointestinal upset caused by metronidazole or clindamycin.

Given that there are no benefits—and some harms—resulting from treatment, the Task Force recommends against screening for BV in non-high-risk pregnant women. A lack of sufficient information to assess any potential benefits to screening in high-risk pregnancies led the Task Force to an “I” statement on this question.8

Behavioral counseling on healthy diet, exercise for adults with CV risks

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of death in the United States. The major risk factors for CVD, which can be modified, are high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity or overweight, and lack of physical activity.

The Task Force has previously recommended intensive behavioral interventions to improve nutrition and physical activity in those who are overweight/obese and in those with abnormal blood glucose levels,9 and has addressed smoking prevention and cessation.4 This new recommendation applies to those with other CVD risks such as high blood pressure and/or hyperlipidemia and those with an estimated 10-year CVD risk of ≥ 7.5%.10

Continue to: Behavioral interventions...

Behavioral interventions included in the Task Force analysis employed a median of 12 contacts and an estimated 6 hours of contact time over 6 to 18 months.10 Most interventions involved motivational interviewing and instruction on behavioral change methods. These interventions can be provided by primary care clinicians, as well as a wide range of other trained professionals. The Affordable Care Act dictates that all “A” and “B” recommendations must be provided by commercial health plans at no out-of-pocket expense for the patient.

Nutritional advice should include reductions in saturated fats, salt, and sugars and increases in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet are often recommended.10 Physical activity counseling should advocate for 90 to 180 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous activity.

This new recommendation, along with the previous ones pertaining to behavioral interventions for lifestyle changes, make it clear that intensive interventions are needed to achieve meaningful change. Simple advice from a clinician will have little to no effect.

Task Force reviews evidence on HTN, smoking cessation in young people

In 2020 the Task Force completed reviews of evidence relevant to screening for high blood pressure11 and

The 2 “I” statements are in disagreement with recommendations of other professional organizations. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association recommend routine screening for high blood pressure starting at age 3 years. And the AAP recommends screening teenagers for tobacco use and offering tobacco dependence treatment, referral, or both (including pharmacotherapy) when indicated. E-cigarettes are not recommended as a treatment for tobacco dependence.20

Continue to: The difference between...

The difference between the methods used by the Task Force and other guideline-producing organizations becomes apparent when it comes to recommendations pertaining to children and adolescents, for whom long-term outcome-oriented studies on prevention issues are rare. The Task Force is unwilling to make recommendations when evidence does not exist. The AAP often makes recommendations based on expert opinion consensus in such situations. One notable part of each Task Force recommendation statement is a discussion of what other organizations recommend on the same topic so that these differences can be openly described.

Better Task Force funding could expand topic coverage

It is worth revisiting 2 issues that were pointed out in last year’s USPSTF summary in this column.1 First, the Task Force methods are robust and evidence based, and recommendations therefore are rarely changed once they are made at an “A”, “B”, or “D” level. Second, Task Force resources are finite, and thus, the group is currently unable to update previous recommendations with greater frequency or to consider many new topics. In the past 2 years, the Task Force has developed recommendations on only 2 completely new topics. Hopefully, its budget can be expanded so that new topics can be added in the future.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF roundup. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:201-204.

2. USPSTF. Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

3. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. Accessed April 30, 2021. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

4. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. JAMA. 2021;325:265-279.

5. USPSTF. Screening for Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

6. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-in-pregnant-women-screening

7. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening

8. USPSTF; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krisk AH, et al. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant persons to prevent preterm delivery: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:1286-1292.

9. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:587-593.

10. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324:2069-2075.

11. USPSTF. High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

12. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

13. USPSTF. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening

14. USPSTF. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents

15. USPSTF. Unhealthy drug use: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening

16. USPSTF. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF update on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:514-517.

18. Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al; ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E76-E123.

19. Ricotta JJ, Aburahma A, Ascher E, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:e1-e31.

20. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al; Section on Tobacco Control. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017.

Since the last Practice Alert update on recommendations made by the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 the Task Force has completed work on 12 topics (TABLE 1).2-17 Five of these topics have been discussed in JFP audio recordings, and the links are provided in TABLE 1.

This latest Task Force endeavor resulted in 18 recommendations (TABLE 2), all of which reaffirm previous recommendations on these topics and expand the scope of 2. There were 2 “A” recommendations, 6 “B” recommendations, 2 “D” recommendations, and 8 “I” statements, indicating that there was insufficient evidence to assess effectiveness or harms. The willingness to make “I” statements when there is little or no evidence on the intervention being assessed distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline committees.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis

One of the “D” recommendations this past year reaffirms the prior recommendation against screening for carotid artery stenosis in asymptomatic adults—ie, those without a history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or neurologic signs or symptoms that might be caused by carotid artery stenosis.2 The screening tests the Task Force researched included carotid duplex ultrasonography (DUS), magnetic resonance angiography, and computed tomography angiography. The Task Force did not look at the value of auscultation for carotid bruits because it has been proven to be inaccurate and they do not consider it to be a useful screening tool.

The Task Force based its “D” recommendation on a lack of evidence for any benefit in detecting asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, and on evidence that screening can lead to harms through false-positive tests and potential complications from carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery angioplasty and stenting. In its clinical considerations, the Task Force emphasized the primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease by focusing on the following actions:

- screening for high blood pressure in adults

- encouraging tobacco smoking cessation in adults

- promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with cardiovascular risk factors

- recommending aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer

- advising statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults ages 45 to 75 years who have 1 or more risk factors (hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and those with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event of 10% or greater.

This “D” recommendation differs from recommendations made by other professional organizations, some of which recommend testing with DUS for asymptomatic patients with a carotid bruit, and others that recommend DUS screening in patients with multiple risk factors for stroke and in those with known peripheral artery disease or other cardiovascular disease.18,19

Smoking cessation in adults

Smoking tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, causing about 480,000 deaths annually.3 Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of complications including miscarriage, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and placental abruption.

The Task Force published recommendations earlier this year advising all clinicians to ask all adult patients about tobacco use; and, for those who smoke, to provide (or refer them to) smoking cessation behavioral therapy. The Task Force also recommends prescribing pharmacotherapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smoking cessation for nonpregnant adults. (There is a lack of information to assess the harms and benefits of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy during pregnancy.)

Continue to: FDA-approved medications...

FDA-approved medications for treating tobacco smoking dependence are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion hydrochloride, and varenicline.3 NRT is available in transdermal patches, lozenges, gum, inhalers, and nasal sprays.

In addition, the Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of e-cigarettes when used as a method of achieving smoking cessation: “Few randomized trials have evaluated the effectiveness of e-cigarettes to increase tobacco smoking cessation in nonpregnant adults, and no trials have evaluated e-cigarettes for tobacco smoking cessation in pregnant persons.”4

Hepatitis B infection screening

The Task Force reaffirmed a previous recommendation to screen for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection only in adults who are at high risk,5 rather than universal screening that it recommends for hepatitis C virus infection (HCV).7 (See: https://bit.ly/3tt064Q). The Task Force has a separate recommendation to screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B at the first prenatal visit.6

Those at high risk for hepatitis B who should be screened include individuals born in countries or regions of the world with a hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence ≥ 2% and individuals born in the United States who have not received HBV vaccine and whose parents were born in regions with an HBsAg prevalence ≥ 8%.5 (A table listing countries with HBsAg ≥ 8%—as well as those in lower prevalence categories—is included with the recommendation.5)

HBV screening should also be offered to other high-risk groups that have a prevalence of positive HBsAg ≥ 2%: those who have injected drugs in the past or are currently injecting drugs; men who have sex with men; individuals with HIV; and sex partners, needle-sharing contacts, and household contacts of people known to be HBsAg positive.5

Continue to: It is estimated that...

It is estimated that > 860,000 people in the United States have chronic HBV infection and that close to two-thirds of them are unaware of their infection.5 The screening test for HBV is highly accurate; sensitivity and specificity are both > 98%.5 While there is no direct evidence that screening, detecting, and treating asymptomatic HBV infection reduces morbidity and mortality, the Task Force felt that the evidence for improvement in multiple outcomes in those with HBV when treated with antiviral regimens was sufficient to support the recommendation.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

While bacterial vaginosis (BV) is associated with a two-fold risk of preterm delivery, treating BV during pregnancy does not seem to reduce this risk, indicating that some other variable is involved.8 In addition, studies that looked at screening for, and treatment of, asymptomatic BV in pregnant women at high risk for preterm delivery (defined primarily as those with a previous preterm delivery) have shown inconsistent results. There is the potential for harm in treating BV in pregnancy, chiefly involving gastrointestinal upset caused by metronidazole or clindamycin.

Given that there are no benefits—and some harms—resulting from treatment, the Task Force recommends against screening for BV in non-high-risk pregnant women. A lack of sufficient information to assess any potential benefits to screening in high-risk pregnancies led the Task Force to an “I” statement on this question.8

Behavioral counseling on healthy diet, exercise for adults with CV risks

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of death in the United States. The major risk factors for CVD, which can be modified, are high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity or overweight, and lack of physical activity.

The Task Force has previously recommended intensive behavioral interventions to improve nutrition and physical activity in those who are overweight/obese and in those with abnormal blood glucose levels,9 and has addressed smoking prevention and cessation.4 This new recommendation applies to those with other CVD risks such as high blood pressure and/or hyperlipidemia and those with an estimated 10-year CVD risk of ≥ 7.5%.10

Continue to: Behavioral interventions...

Behavioral interventions included in the Task Force analysis employed a median of 12 contacts and an estimated 6 hours of contact time over 6 to 18 months.10 Most interventions involved motivational interviewing and instruction on behavioral change methods. These interventions can be provided by primary care clinicians, as well as a wide range of other trained professionals. The Affordable Care Act dictates that all “A” and “B” recommendations must be provided by commercial health plans at no out-of-pocket expense for the patient.

Nutritional advice should include reductions in saturated fats, salt, and sugars and increases in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet are often recommended.10 Physical activity counseling should advocate for 90 to 180 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous activity.

This new recommendation, along with the previous ones pertaining to behavioral interventions for lifestyle changes, make it clear that intensive interventions are needed to achieve meaningful change. Simple advice from a clinician will have little to no effect.

Task Force reviews evidence on HTN, smoking cessation in young people

In 2020 the Task Force completed reviews of evidence relevant to screening for high blood pressure11 and

The 2 “I” statements are in disagreement with recommendations of other professional organizations. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association recommend routine screening for high blood pressure starting at age 3 years. And the AAP recommends screening teenagers for tobacco use and offering tobacco dependence treatment, referral, or both (including pharmacotherapy) when indicated. E-cigarettes are not recommended as a treatment for tobacco dependence.20

Continue to: The difference between...

The difference between the methods used by the Task Force and other guideline-producing organizations becomes apparent when it comes to recommendations pertaining to children and adolescents, for whom long-term outcome-oriented studies on prevention issues are rare. The Task Force is unwilling to make recommendations when evidence does not exist. The AAP often makes recommendations based on expert opinion consensus in such situations. One notable part of each Task Force recommendation statement is a discussion of what other organizations recommend on the same topic so that these differences can be openly described.

Better Task Force funding could expand topic coverage

It is worth revisiting 2 issues that were pointed out in last year’s USPSTF summary in this column.1 First, the Task Force methods are robust and evidence based, and recommendations therefore are rarely changed once they are made at an “A”, “B”, or “D” level. Second, Task Force resources are finite, and thus, the group is currently unable to update previous recommendations with greater frequency or to consider many new topics. In the past 2 years, the Task Force has developed recommendations on only 2 completely new topics. Hopefully, its budget can be expanded so that new topics can be added in the future.

Since the last Practice Alert update on recommendations made by the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 the Task Force has completed work on 12 topics (TABLE 1).2-17 Five of these topics have been discussed in JFP audio recordings, and the links are provided in TABLE 1.

This latest Task Force endeavor resulted in 18 recommendations (TABLE 2), all of which reaffirm previous recommendations on these topics and expand the scope of 2. There were 2 “A” recommendations, 6 “B” recommendations, 2 “D” recommendations, and 8 “I” statements, indicating that there was insufficient evidence to assess effectiveness or harms. The willingness to make “I” statements when there is little or no evidence on the intervention being assessed distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline committees.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis

One of the “D” recommendations this past year reaffirms the prior recommendation against screening for carotid artery stenosis in asymptomatic adults—ie, those without a history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or neurologic signs or symptoms that might be caused by carotid artery stenosis.2 The screening tests the Task Force researched included carotid duplex ultrasonography (DUS), magnetic resonance angiography, and computed tomography angiography. The Task Force did not look at the value of auscultation for carotid bruits because it has been proven to be inaccurate and they do not consider it to be a useful screening tool.

The Task Force based its “D” recommendation on a lack of evidence for any benefit in detecting asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, and on evidence that screening can lead to harms through false-positive tests and potential complications from carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery angioplasty and stenting. In its clinical considerations, the Task Force emphasized the primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease by focusing on the following actions:

- screening for high blood pressure in adults

- encouraging tobacco smoking cessation in adults

- promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with cardiovascular risk factors

- recommending aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer

- advising statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults ages 45 to 75 years who have 1 or more risk factors (hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and those with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event of 10% or greater.

This “D” recommendation differs from recommendations made by other professional organizations, some of which recommend testing with DUS for asymptomatic patients with a carotid bruit, and others that recommend DUS screening in patients with multiple risk factors for stroke and in those with known peripheral artery disease or other cardiovascular disease.18,19

Smoking cessation in adults

Smoking tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, causing about 480,000 deaths annually.3 Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of complications including miscarriage, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and placental abruption.

The Task Force published recommendations earlier this year advising all clinicians to ask all adult patients about tobacco use; and, for those who smoke, to provide (or refer them to) smoking cessation behavioral therapy. The Task Force also recommends prescribing pharmacotherapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smoking cessation for nonpregnant adults. (There is a lack of information to assess the harms and benefits of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy during pregnancy.)

Continue to: FDA-approved medications...

FDA-approved medications for treating tobacco smoking dependence are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion hydrochloride, and varenicline.3 NRT is available in transdermal patches, lozenges, gum, inhalers, and nasal sprays.

In addition, the Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of e-cigarettes when used as a method of achieving smoking cessation: “Few randomized trials have evaluated the effectiveness of e-cigarettes to increase tobacco smoking cessation in nonpregnant adults, and no trials have evaluated e-cigarettes for tobacco smoking cessation in pregnant persons.”4

Hepatitis B infection screening

The Task Force reaffirmed a previous recommendation to screen for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection only in adults who are at high risk,5 rather than universal screening that it recommends for hepatitis C virus infection (HCV).7 (See: https://bit.ly/3tt064Q). The Task Force has a separate recommendation to screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B at the first prenatal visit.6

Those at high risk for hepatitis B who should be screened include individuals born in countries or regions of the world with a hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence ≥ 2% and individuals born in the United States who have not received HBV vaccine and whose parents were born in regions with an HBsAg prevalence ≥ 8%.5 (A table listing countries with HBsAg ≥ 8%—as well as those in lower prevalence categories—is included with the recommendation.5)

HBV screening should also be offered to other high-risk groups that have a prevalence of positive HBsAg ≥ 2%: those who have injected drugs in the past or are currently injecting drugs; men who have sex with men; individuals with HIV; and sex partners, needle-sharing contacts, and household contacts of people known to be HBsAg positive.5

Continue to: It is estimated that...

It is estimated that > 860,000 people in the United States have chronic HBV infection and that close to two-thirds of them are unaware of their infection.5 The screening test for HBV is highly accurate; sensitivity and specificity are both > 98%.5 While there is no direct evidence that screening, detecting, and treating asymptomatic HBV infection reduces morbidity and mortality, the Task Force felt that the evidence for improvement in multiple outcomes in those with HBV when treated with antiviral regimens was sufficient to support the recommendation.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

While bacterial vaginosis (BV) is associated with a two-fold risk of preterm delivery, treating BV during pregnancy does not seem to reduce this risk, indicating that some other variable is involved.8 In addition, studies that looked at screening for, and treatment of, asymptomatic BV in pregnant women at high risk for preterm delivery (defined primarily as those with a previous preterm delivery) have shown inconsistent results. There is the potential for harm in treating BV in pregnancy, chiefly involving gastrointestinal upset caused by metronidazole or clindamycin.

Given that there are no benefits—and some harms—resulting from treatment, the Task Force recommends against screening for BV in non-high-risk pregnant women. A lack of sufficient information to assess any potential benefits to screening in high-risk pregnancies led the Task Force to an “I” statement on this question.8

Behavioral counseling on healthy diet, exercise for adults with CV risks

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of death in the United States. The major risk factors for CVD, which can be modified, are high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity or overweight, and lack of physical activity.

The Task Force has previously recommended intensive behavioral interventions to improve nutrition and physical activity in those who are overweight/obese and in those with abnormal blood glucose levels,9 and has addressed smoking prevention and cessation.4 This new recommendation applies to those with other CVD risks such as high blood pressure and/or hyperlipidemia and those with an estimated 10-year CVD risk of ≥ 7.5%.10

Continue to: Behavioral interventions...

Behavioral interventions included in the Task Force analysis employed a median of 12 contacts and an estimated 6 hours of contact time over 6 to 18 months.10 Most interventions involved motivational interviewing and instruction on behavioral change methods. These interventions can be provided by primary care clinicians, as well as a wide range of other trained professionals. The Affordable Care Act dictates that all “A” and “B” recommendations must be provided by commercial health plans at no out-of-pocket expense for the patient.

Nutritional advice should include reductions in saturated fats, salt, and sugars and increases in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet are often recommended.10 Physical activity counseling should advocate for 90 to 180 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous activity.

This new recommendation, along with the previous ones pertaining to behavioral interventions for lifestyle changes, make it clear that intensive interventions are needed to achieve meaningful change. Simple advice from a clinician will have little to no effect.

Task Force reviews evidence on HTN, smoking cessation in young people

In 2020 the Task Force completed reviews of evidence relevant to screening for high blood pressure11 and

The 2 “I” statements are in disagreement with recommendations of other professional organizations. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association recommend routine screening for high blood pressure starting at age 3 years. And the AAP recommends screening teenagers for tobacco use and offering tobacco dependence treatment, referral, or both (including pharmacotherapy) when indicated. E-cigarettes are not recommended as a treatment for tobacco dependence.20

Continue to: The difference between...

The difference between the methods used by the Task Force and other guideline-producing organizations becomes apparent when it comes to recommendations pertaining to children and adolescents, for whom long-term outcome-oriented studies on prevention issues are rare. The Task Force is unwilling to make recommendations when evidence does not exist. The AAP often makes recommendations based on expert opinion consensus in such situations. One notable part of each Task Force recommendation statement is a discussion of what other organizations recommend on the same topic so that these differences can be openly described.

Better Task Force funding could expand topic coverage

It is worth revisiting 2 issues that were pointed out in last year’s USPSTF summary in this column.1 First, the Task Force methods are robust and evidence based, and recommendations therefore are rarely changed once they are made at an “A”, “B”, or “D” level. Second, Task Force resources are finite, and thus, the group is currently unable to update previous recommendations with greater frequency or to consider many new topics. In the past 2 years, the Task Force has developed recommendations on only 2 completely new topics. Hopefully, its budget can be expanded so that new topics can be added in the future.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF roundup. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:201-204.

2. USPSTF. Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

3. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. Accessed April 30, 2021. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

4. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. JAMA. 2021;325:265-279.

5. USPSTF. Screening for Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

6. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-in-pregnant-women-screening

7. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening

8. USPSTF; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krisk AH, et al. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant persons to prevent preterm delivery: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:1286-1292.

9. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:587-593.

10. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324:2069-2075.

11. USPSTF. High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

12. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

13. USPSTF. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening

14. USPSTF. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents

15. USPSTF. Unhealthy drug use: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening

16. USPSTF. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF update on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:514-517.

18. Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al; ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E76-E123.

19. Ricotta JJ, Aburahma A, Ascher E, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:e1-e31.

20. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al; Section on Tobacco Control. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF roundup. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:201-204.

2. USPSTF. Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

3. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. Accessed April 30, 2021. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

4. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. JAMA. 2021;325:265-279.

5. USPSTF. Screening for Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

6. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-in-pregnant-women-screening

7. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening

8. USPSTF; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krisk AH, et al. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant persons to prevent preterm delivery: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:1286-1292.

9. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:587-593.

10. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324:2069-2075.

11. USPSTF. High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

12. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

13. USPSTF. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening

14. USPSTF. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents

15. USPSTF. Unhealthy drug use: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening

16. USPSTF. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF update on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:514-517.

18. Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al; ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E76-E123.

19. Ricotta JJ, Aburahma A, Ascher E, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:e1-e31.

20. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al; Section on Tobacco Control. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017.

Keep antibiotics unchanged in breakthrough UTIs

Changing the continuous antibiotic prophylactic agent had no significant effect on the risk of a second infection in children with breakthrough urinary tract infections (UTIs), based on data from 62 children treated at a single center.

Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP) is often used for UTI prevention in children with febrile UTIs or anomalies that predispose them to UTIs, such as vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) or bladder and bowel dysfunction, said Lane M. Shish, MPH, of the University of Washington, Bothell, and colleagues in a poster (#1245) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

CAP, once initiated, is used until a planned endpoint or a breakthrough UTI, at which point alternative treatments usually include surgical intervention or a CAP agent change, the researchers said. However, changing the CAP agent is based on consensus without evidence of benefit, they noted.

To evaluate the potential effect of switching or maintaining CAP in cases of breakthrough UTIs, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of all patients younger than 18 years on CAP for UTI prevention enrolled in a pediatric urology registry between January 2013 and August 2020.

All patients experienced a breakthrough UTI while on CAP; CAP was changed for 24 patients and left unchanged for 38 patients.

The primary outcome of second-breakthrough infections occurred in 12 of the changed CAP group and 22 of the unchanged group, with a relative risk of 0.86. The percentage of second breakthrough UTIs resistant to the current CAP was not significantly different between the changed and unchanged CAP groups (75% vs. 77%; P = 0.88).

The researchers also identified a rate ratio of 0.67 for a second breakthrough UTI in the changed CAP group, and found that approximately one-third of these patients (33.3%) developed antibiotic resistance to their initial antibiotic agent and the changed antibiotic agent.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and small sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that changing the CAP after an initial breakthrough UTI in children did not increase the risk of a second breakthrough UTI, and that CAP changing did introduce a risk of developing a second UTI with increased CAP resistance, the researchers noted. The results support leaving a child’s CAP unchanged after an initial breakthrough UTI, although additional research is needed to verify the findings, including studies involving a larger cohort with a multi-institutional prospective evaluation, they concluded.

Manage UTIs to reduce recurrence and resistance

“As we know, avoiding recurrent UTIs is important in preserving renal function in pediatric patients,” said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“Avoiding recurrent UTIs is also important to avoid the development and spread of multidrug-resistant organisms,” he said.

Dr. Joos said he was surprised by some of the study findings. “I was surprised that, over the course of this 7-year retrospective review, overall only approximately 50% of patients with a first breakthrough UTI on CAP developed a second breakthrough UTI,” he noted. “Also, the relative risk of a second UTI was not significantly affected by whether the CAP antibiotic was changed after the first infection,” he said. “It would be interesting to see whether these results hold up in a randomized, prospective study,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Changing the continuous antibiotic prophylactic agent had no significant effect on the risk of a second infection in children with breakthrough urinary tract infections (UTIs), based on data from 62 children treated at a single center.

Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP) is often used for UTI prevention in children with febrile UTIs or anomalies that predispose them to UTIs, such as vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) or bladder and bowel dysfunction, said Lane M. Shish, MPH, of the University of Washington, Bothell, and colleagues in a poster (#1245) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

CAP, once initiated, is used until a planned endpoint or a breakthrough UTI, at which point alternative treatments usually include surgical intervention or a CAP agent change, the researchers said. However, changing the CAP agent is based on consensus without evidence of benefit, they noted.

To evaluate the potential effect of switching or maintaining CAP in cases of breakthrough UTIs, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of all patients younger than 18 years on CAP for UTI prevention enrolled in a pediatric urology registry between January 2013 and August 2020.

All patients experienced a breakthrough UTI while on CAP; CAP was changed for 24 patients and left unchanged for 38 patients.

The primary outcome of second-breakthrough infections occurred in 12 of the changed CAP group and 22 of the unchanged group, with a relative risk of 0.86. The percentage of second breakthrough UTIs resistant to the current CAP was not significantly different between the changed and unchanged CAP groups (75% vs. 77%; P = 0.88).

The researchers also identified a rate ratio of 0.67 for a second breakthrough UTI in the changed CAP group, and found that approximately one-third of these patients (33.3%) developed antibiotic resistance to their initial antibiotic agent and the changed antibiotic agent.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and small sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that changing the CAP after an initial breakthrough UTI in children did not increase the risk of a second breakthrough UTI, and that CAP changing did introduce a risk of developing a second UTI with increased CAP resistance, the researchers noted. The results support leaving a child’s CAP unchanged after an initial breakthrough UTI, although additional research is needed to verify the findings, including studies involving a larger cohort with a multi-institutional prospective evaluation, they concluded.

Manage UTIs to reduce recurrence and resistance

“As we know, avoiding recurrent UTIs is important in preserving renal function in pediatric patients,” said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“Avoiding recurrent UTIs is also important to avoid the development and spread of multidrug-resistant organisms,” he said.

Dr. Joos said he was surprised by some of the study findings. “I was surprised that, over the course of this 7-year retrospective review, overall only approximately 50% of patients with a first breakthrough UTI on CAP developed a second breakthrough UTI,” he noted. “Also, the relative risk of a second UTI was not significantly affected by whether the CAP antibiotic was changed after the first infection,” he said. “It would be interesting to see whether these results hold up in a randomized, prospective study,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Changing the continuous antibiotic prophylactic agent had no significant effect on the risk of a second infection in children with breakthrough urinary tract infections (UTIs), based on data from 62 children treated at a single center.

Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP) is often used for UTI prevention in children with febrile UTIs or anomalies that predispose them to UTIs, such as vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) or bladder and bowel dysfunction, said Lane M. Shish, MPH, of the University of Washington, Bothell, and colleagues in a poster (#1245) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

CAP, once initiated, is used until a planned endpoint or a breakthrough UTI, at which point alternative treatments usually include surgical intervention or a CAP agent change, the researchers said. However, changing the CAP agent is based on consensus without evidence of benefit, they noted.

To evaluate the potential effect of switching or maintaining CAP in cases of breakthrough UTIs, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of all patients younger than 18 years on CAP for UTI prevention enrolled in a pediatric urology registry between January 2013 and August 2020.

All patients experienced a breakthrough UTI while on CAP; CAP was changed for 24 patients and left unchanged for 38 patients.

The primary outcome of second-breakthrough infections occurred in 12 of the changed CAP group and 22 of the unchanged group, with a relative risk of 0.86. The percentage of second breakthrough UTIs resistant to the current CAP was not significantly different between the changed and unchanged CAP groups (75% vs. 77%; P = 0.88).

The researchers also identified a rate ratio of 0.67 for a second breakthrough UTI in the changed CAP group, and found that approximately one-third of these patients (33.3%) developed antibiotic resistance to their initial antibiotic agent and the changed antibiotic agent.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and small sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that changing the CAP after an initial breakthrough UTI in children did not increase the risk of a second breakthrough UTI, and that CAP changing did introduce a risk of developing a second UTI with increased CAP resistance, the researchers noted. The results support leaving a child’s CAP unchanged after an initial breakthrough UTI, although additional research is needed to verify the findings, including studies involving a larger cohort with a multi-institutional prospective evaluation, they concluded.

Manage UTIs to reduce recurrence and resistance

“As we know, avoiding recurrent UTIs is important in preserving renal function in pediatric patients,” said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“Avoiding recurrent UTIs is also important to avoid the development and spread of multidrug-resistant organisms,” he said.

Dr. Joos said he was surprised by some of the study findings. “I was surprised that, over the course of this 7-year retrospective review, overall only approximately 50% of patients with a first breakthrough UTI on CAP developed a second breakthrough UTI,” he noted. “Also, the relative risk of a second UTI was not significantly affected by whether the CAP antibiotic was changed after the first infection,” he said. “It would be interesting to see whether these results hold up in a randomized, prospective study,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

FROM PAS 2021

Finerenone scores second pivotal-trial success in patients with diabetic kidney disease

Finerenone, an investigational agent from a new drug class, just scored a second pivotal trial win after showing significant benefit for slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes in the FIDELIO-DKD pivotal trial with more than 5,700 patients.

Top-line results from FIGARO-DKD showed significant benefit for the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death and nonfatal cardiovascular disease endpoints in a placebo-controlled trial with about 7,400 patients with type 2 diabetes, reported Bayer, the company developing finerenone in statement released on May 10, 2021.

Based on the FIDELIO-DKD results, finerenone is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for marketing approval as a treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. FIDELIO-DKD, in addition to the primary endpoint that focused on slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease, had a secondary endpoint that assessed the combined incidence on treatment of cardiovascular death, or nonfatal episodes of stroke, MI, or hospitalization for heart failure. Results from the study published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that finerenone was safe and effective for both endpoints.

In the current study, FIGARO-DKD, run at more than 1,000 sites in 47 countries, these endpoints flipped. The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death or nonfatal cardiovascular disease events, and the secondary outcome was prevention of DKD progression.

Other than stating the results significantly fulfilled FIGARO-DKD’s primary endpoint of reducing the incidence of combined cardiovascular disease endpoints, the release gave no further outcome details. The release noted that the enrolled patient cohort in FIGARO-DKD included more patients with earlier-stage chronic kidney disease, compared with FIDELIO-DKD.

Finerenone is a first-in-class investigational nonsteroidal, selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA). As an MRA it shares certain activities with the steroidal MRAs spironolactone and eplerenone. But the absence of a steroidal structure means that finerenone does not cause steroidal adverse effects such as gynecomastia. Results in FIDELIO-DKD showed that finerenone caused more hyperkalemia than placebo, but the level of hyperkalemia that it causes relative to spironolactone or eplerenone remains uncertain.

Finerenone, an investigational agent from a new drug class, just scored a second pivotal trial win after showing significant benefit for slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes in the FIDELIO-DKD pivotal trial with more than 5,700 patients.

Top-line results from FIGARO-DKD showed significant benefit for the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death and nonfatal cardiovascular disease endpoints in a placebo-controlled trial with about 7,400 patients with type 2 diabetes, reported Bayer, the company developing finerenone in statement released on May 10, 2021.

Based on the FIDELIO-DKD results, finerenone is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for marketing approval as a treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. FIDELIO-DKD, in addition to the primary endpoint that focused on slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease, had a secondary endpoint that assessed the combined incidence on treatment of cardiovascular death, or nonfatal episodes of stroke, MI, or hospitalization for heart failure. Results from the study published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that finerenone was safe and effective for both endpoints.

In the current study, FIGARO-DKD, run at more than 1,000 sites in 47 countries, these endpoints flipped. The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death or nonfatal cardiovascular disease events, and the secondary outcome was prevention of DKD progression.

Other than stating the results significantly fulfilled FIGARO-DKD’s primary endpoint of reducing the incidence of combined cardiovascular disease endpoints, the release gave no further outcome details. The release noted that the enrolled patient cohort in FIGARO-DKD included more patients with earlier-stage chronic kidney disease, compared with FIDELIO-DKD.

Finerenone is a first-in-class investigational nonsteroidal, selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA). As an MRA it shares certain activities with the steroidal MRAs spironolactone and eplerenone. But the absence of a steroidal structure means that finerenone does not cause steroidal adverse effects such as gynecomastia. Results in FIDELIO-DKD showed that finerenone caused more hyperkalemia than placebo, but the level of hyperkalemia that it causes relative to spironolactone or eplerenone remains uncertain.

Finerenone, an investigational agent from a new drug class, just scored a second pivotal trial win after showing significant benefit for slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes in the FIDELIO-DKD pivotal trial with more than 5,700 patients.

Top-line results from FIGARO-DKD showed significant benefit for the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death and nonfatal cardiovascular disease endpoints in a placebo-controlled trial with about 7,400 patients with type 2 diabetes, reported Bayer, the company developing finerenone in statement released on May 10, 2021.

Based on the FIDELIO-DKD results, finerenone is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for marketing approval as a treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. FIDELIO-DKD, in addition to the primary endpoint that focused on slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease, had a secondary endpoint that assessed the combined incidence on treatment of cardiovascular death, or nonfatal episodes of stroke, MI, or hospitalization for heart failure. Results from the study published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that finerenone was safe and effective for both endpoints.

In the current study, FIGARO-DKD, run at more than 1,000 sites in 47 countries, these endpoints flipped. The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death or nonfatal cardiovascular disease events, and the secondary outcome was prevention of DKD progression.

Other than stating the results significantly fulfilled FIGARO-DKD’s primary endpoint of reducing the incidence of combined cardiovascular disease endpoints, the release gave no further outcome details. The release noted that the enrolled patient cohort in FIGARO-DKD included more patients with earlier-stage chronic kidney disease, compared with FIDELIO-DKD.

Finerenone is a first-in-class investigational nonsteroidal, selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA). As an MRA it shares certain activities with the steroidal MRAs spironolactone and eplerenone. But the absence of a steroidal structure means that finerenone does not cause steroidal adverse effects such as gynecomastia. Results in FIDELIO-DKD showed that finerenone caused more hyperkalemia than placebo, but the level of hyperkalemia that it causes relative to spironolactone or eplerenone remains uncertain.

FDA approves dapagliflozin (Farxiga) for chronic kidney disease

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) to reduce the risk for kidney function decline, kidney failure, cardiovascular death, and hospitalization for heart failure in adult patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) at risk for disease progression.

“Chronic kidney disease is an important public health issue, and there is a significant unmet need for therapies that slow disease progression and improve outcomes,” said Aliza Thompson, MD, deputy director of the division of cardiology and nephrology at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Today’s approval of Farxiga for the treatment of chronic kidney disease is an important step forward in helping people living with kidney disease.”

Dapagliflozin was approved in 2014 to improve glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus, and approval was expanded in 2020 to include treatment of patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction, based on results of the DAPA-HF trial.

This new approval in chronic kidney disease was based on results of the DAPA-CKD trial that was stopped early in March 2020 because of efficacy of the treatment.

DAPA-CKD randomly assigned 4,304 patients with CKD but without diabetes to receive either dapagliflozin or placebo. The full study results, reported at the 2020 annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that, during a median of 2.4 years, treatment with dapagliflozin led to a significant 31% relative reduction, compared with placebo in the study’s primary outcome, a composite that included at least a 50% drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate, compared with baseline, end-stage kidney disease, kidney transplant, renal death, or cardiovascular death.

Dapagliflozin treatment also cut all-cause mortality by a statistically significant relative reduction of 31%, and another secondary-endpoint analysis showed a statistically significant 29% relative reduction in the rate of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization.

“Farxiga was not studied, nor is expected to be effective, in treating chronic kidney disease among patients with autosomal dominant or recessive polycystic (characterized by multiple cysts) kidney disease or among patients who require or have recently used immunosuppressive therapy to treat kidney disease,” the FDA statement noted.

Dapagliflozin should not be used by patients with a history of serious hypersensitivity reactions to this medication, or who are on dialysis, the agency added. “Serious, life-threatening cases of Fournier’s Gangrene have occurred in patients with diabetes taking Farxiga.”

Patients should consider taking a lower dose of insulin or insulin secretagogue to reduce hypoglycemic risk if they are also taking dapagliflozin. Treatment can also cause dehydration, serious urinary tract infections, genital yeast infections, and metabolic acidosis, the announcement said. “Patients should be assessed for their volume status and kidney function before starting Farxiga.”

Dapagliflozin previously received Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, and Priority Review designations for this new indication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) to reduce the risk for kidney function decline, kidney failure, cardiovascular death, and hospitalization for heart failure in adult patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) at risk for disease progression.

“Chronic kidney disease is an important public health issue, and there is a significant unmet need for therapies that slow disease progression and improve outcomes,” said Aliza Thompson, MD, deputy director of the division of cardiology and nephrology at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Today’s approval of Farxiga for the treatment of chronic kidney disease is an important step forward in helping people living with kidney disease.”

Dapagliflozin was approved in 2014 to improve glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus, and approval was expanded in 2020 to include treatment of patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction, based on results of the DAPA-HF trial.

This new approval in chronic kidney disease was based on results of the DAPA-CKD trial that was stopped early in March 2020 because of efficacy of the treatment.

DAPA-CKD randomly assigned 4,304 patients with CKD but without diabetes to receive either dapagliflozin or placebo. The full study results, reported at the 2020 annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that, during a median of 2.4 years, treatment with dapagliflozin led to a significant 31% relative reduction, compared with placebo in the study’s primary outcome, a composite that included at least a 50% drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate, compared with baseline, end-stage kidney disease, kidney transplant, renal death, or cardiovascular death.

Dapagliflozin treatment also cut all-cause mortality by a statistically significant relative reduction of 31%, and another secondary-endpoint analysis showed a statistically significant 29% relative reduction in the rate of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization.

“Farxiga was not studied, nor is expected to be effective, in treating chronic kidney disease among patients with autosomal dominant or recessive polycystic (characterized by multiple cysts) kidney disease or among patients who require or have recently used immunosuppressive therapy to treat kidney disease,” the FDA statement noted.

Dapagliflozin should not be used by patients with a history of serious hypersensitivity reactions to this medication, or who are on dialysis, the agency added. “Serious, life-threatening cases of Fournier’s Gangrene have occurred in patients with diabetes taking Farxiga.”

Patients should consider taking a lower dose of insulin or insulin secretagogue to reduce hypoglycemic risk if they are also taking dapagliflozin. Treatment can also cause dehydration, serious urinary tract infections, genital yeast infections, and metabolic acidosis, the announcement said. “Patients should be assessed for their volume status and kidney function before starting Farxiga.”

Dapagliflozin previously received Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, and Priority Review designations for this new indication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) to reduce the risk for kidney function decline, kidney failure, cardiovascular death, and hospitalization for heart failure in adult patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) at risk for disease progression.

“Chronic kidney disease is an important public health issue, and there is a significant unmet need for therapies that slow disease progression and improve outcomes,” said Aliza Thompson, MD, deputy director of the division of cardiology and nephrology at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Today’s approval of Farxiga for the treatment of chronic kidney disease is an important step forward in helping people living with kidney disease.”

Dapagliflozin was approved in 2014 to improve glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus, and approval was expanded in 2020 to include treatment of patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction, based on results of the DAPA-HF trial.

This new approval in chronic kidney disease was based on results of the DAPA-CKD trial that was stopped early in March 2020 because of efficacy of the treatment.

DAPA-CKD randomly assigned 4,304 patients with CKD but without diabetes to receive either dapagliflozin or placebo. The full study results, reported at the 2020 annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that, during a median of 2.4 years, treatment with dapagliflozin led to a significant 31% relative reduction, compared with placebo in the study’s primary outcome, a composite that included at least a 50% drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate, compared with baseline, end-stage kidney disease, kidney transplant, renal death, or cardiovascular death.

Dapagliflozin treatment also cut all-cause mortality by a statistically significant relative reduction of 31%, and another secondary-endpoint analysis showed a statistically significant 29% relative reduction in the rate of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization.

“Farxiga was not studied, nor is expected to be effective, in treating chronic kidney disease among patients with autosomal dominant or recessive polycystic (characterized by multiple cysts) kidney disease or among patients who require or have recently used immunosuppressive therapy to treat kidney disease,” the FDA statement noted.

Dapagliflozin should not be used by patients with a history of serious hypersensitivity reactions to this medication, or who are on dialysis, the agency added. “Serious, life-threatening cases of Fournier’s Gangrene have occurred in patients with diabetes taking Farxiga.”

Patients should consider taking a lower dose of insulin or insulin secretagogue to reduce hypoglycemic risk if they are also taking dapagliflozin. Treatment can also cause dehydration, serious urinary tract infections, genital yeast infections, and metabolic acidosis, the announcement said. “Patients should be assessed for their volume status and kidney function before starting Farxiga.”

Dapagliflozin previously received Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, and Priority Review designations for this new indication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pregnancy increases risk for symptomatic kidney stones

Pregnancy increases the risk for first-time symptomatic kidney stone formation which peaks close to the time of delivery but can persist even a year later, a population-based, case-controlled study suggests.

“We suspected the risk of a kidney stone event would be high during pregnancy, but we were surprised that the risk remained high for up to a year after delivery,” senior author Andrew Rule, MD, a nephrologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn, said in a statement from his institution.

“[So] while most kidney stones that form during pregnancy are detected early by painful passage, some may remain stable in the kidney undetected for a longer period before dislodging and [again] resulting in a painful passage,” he added.

The study was published online April 15, 2021, in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases by Charat Thongprayoon, MD, also of the Mayo Clinic, and colleagues.

“The results of this study indicate that prenatal counseling regarding kidney stones may be warranted, especially for women with other risk factors for kidney stones, such as obesity,” he noted.

First-time stone formers

The observational study included 945 first-time symptomatic kidney stone formers aged between 15 and 45 years who were compared with 1,890 age-matched female controls from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. The latter is a medical record linkage system for almost all medical care administered in Olmsted County in Minnesota.

Compared with nonpregnant women, the odds of a symptomatic kidney stone forming in a pregnant woman was similar in the first trimester (odds ratio, 0.92; P = .8), began to increase during the second trimester (OR, 2.00; P = .007), further increased during the third trimester (OR, 2.69; P = .001), and peaked at 0-3 months after delivery (OR, 3.53; P < .001). The risk returned to baseline by 1 year after delivery.

These associations persisted after adjustment for age and race or for diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. These results did not significantly differ by age, race, time period, or number of prior pregnancies.

The risk of a pregnant woman developing a symptomatic kidney stone was higher in women with obesity, compared with those of normal weight (P = .01).

And compared with women who had not been pregnant before, one prior pregnancy also increased the risk of having a symptomatic kidney stone by approximately 30% (OR, 1.29; P = .03), although two or more prior pregnancies did not significantly increase symptomatic kidney stone risk.

Thus, “it can be inferred that the odds of a symptomatic kidney stone peak around the time of delivery,” the authors emphasized. “The odds of a first-time symptomatic kidney stone then decreased over time and were fully attenuated and no longer statistically significant by 12 months after delivery.”

Dr. Thongprayoon said there are several physiologic reasons why pregnancy might contribute to kidney stone formation.

During pregnancy, ureteral compression and ureteral relaxation caused by elevated progesterone levels can cause urinary stasis.

Furthermore, increased urinary calcium excretion and elevated urine pH during pregnancy can promote calcium phosphate stone formation. It is noteworthy that almost all pregnant, first-time stone formers had calcium phosphate stones.

“During pregnancy, a kidney stone may contribute to serious complications,” Dr. Thongprayoon explained.

General dietary recommendations for preventing kidney stones include drinking abundant fluids and consuming a low-salt diet.

The study was supported by the Mayo Clinic O’Brien Urology Research Center and a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pregnancy increases the risk for first-time symptomatic kidney stone formation which peaks close to the time of delivery but can persist even a year later, a population-based, case-controlled study suggests.

“We suspected the risk of a kidney stone event would be high during pregnancy, but we were surprised that the risk remained high for up to a year after delivery,” senior author Andrew Rule, MD, a nephrologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn, said in a statement from his institution.