User login

Vaginal and bilateral thigh removal of a transobturator sling

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This video is brought to you by

Myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid in a patient desiring future fertility

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

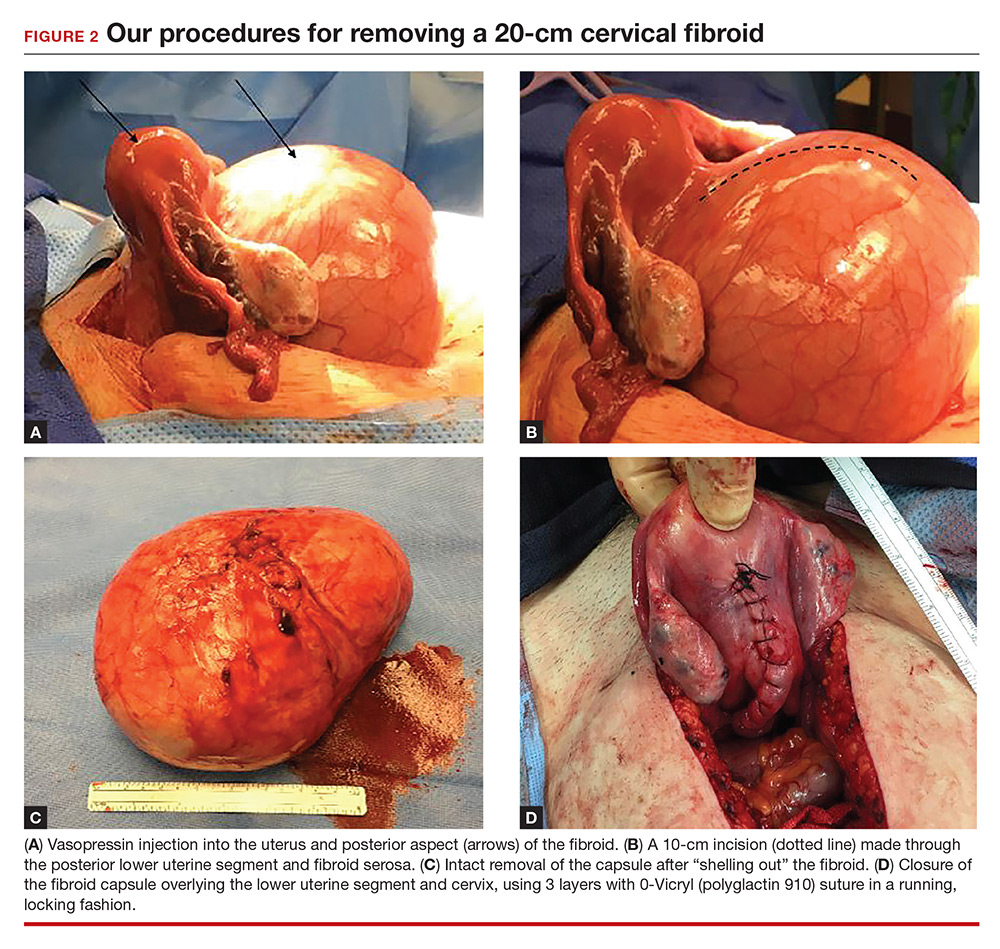

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

Laparoscopic suturing is an option

Laparoscopic suturing is an option

Dr. Lum presented a nicely produced video demonstrating various strategies aimed at facilitating total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus. Her patient’s evaluation included magnetic resonance imaging. In the video, she demonstrates a variety of interventions, including the use of a preoperative gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GNRH) agonist and immediate perioperative radial artery–uterine artery embolization. Intraoperative techniques include use of ureteral stents and securing the uterine arteries at their origins.

Clearly, TLH of a huge uterus is a technical challenge. However, I’d like to suggest that a relatively basic and important skill would greatly assist in such procedures and likely obviate the need for a GNRH agonist and/or uterine artery embolization. The vessel-sealing devices shown in the video are generally not capable of sealing such large vessels adequately, and this is what leads to the massive hemorrhaging that often occurs.

Laparoscopic suturing with extracorporeal knot tying can be used effectively to control the extremely large vessels associated with a huge uterus. The judicious placement of sutures can completely control such vessels and prevent bleeding from both proximal and distal ends when 2 sutures are placed and the vessels are transected between the stitches. Many laparoscopic surgeons have come to rely on bipolar energy or ultrasonic devices to coagulate vessels. But when dealing with huge vessels, a return to basics using laparoscopic suturing will greatly benefit the patient and the surgeon by reducing blood loss and operative time.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Dr. Lum responds

I thank Dr. Zisow for his thoughtful comments. I agree that laparoscopic suturing is an essential skill that can be utilized to suture ligate vessels. If we consider the basics of an open hysterectomy, the uterine artery is clamped first, then suture ligated. When approaching a very large vessel during TLH, I would be concerned that a simple suture around a large vessel might tear through and cause more bleeding. To mitigate this risk, the vessel can be clamped with a grasper first, similar to the approach in an open hysterectomy. However, once a vessel is compressed, a sealing device can usually work just as well as a suture. It becomes a matter of preference and cost.

During hysterectomy of a very large uterus, a big challenge is managing bleeding of the uterus itself during manipulation from above. Bleeding from the vascular sinuses of the myometrium can be brisk and obscure visualization, potentially leading to laparotomy conversion. A common misconception is that uterine artery embolization is equivalent to suturing the uterine arteries. In actuality, the goal of a uterine artery embolization is to embolize the distal branches of the uterine arteries, which can help with any potential bleeding from the uterus itself during hysterectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Laparoscopic suturing is an option

Dr. Lum presented a nicely produced video demonstrating various strategies aimed at facilitating total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus. Her patient’s evaluation included magnetic resonance imaging. In the video, she demonstrates a variety of interventions, including the use of a preoperative gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GNRH) agonist and immediate perioperative radial artery–uterine artery embolization. Intraoperative techniques include use of ureteral stents and securing the uterine arteries at their origins.

Clearly, TLH of a huge uterus is a technical challenge. However, I’d like to suggest that a relatively basic and important skill would greatly assist in such procedures and likely obviate the need for a GNRH agonist and/or uterine artery embolization. The vessel-sealing devices shown in the video are generally not capable of sealing such large vessels adequately, and this is what leads to the massive hemorrhaging that often occurs.

Laparoscopic suturing with extracorporeal knot tying can be used effectively to control the extremely large vessels associated with a huge uterus. The judicious placement of sutures can completely control such vessels and prevent bleeding from both proximal and distal ends when 2 sutures are placed and the vessels are transected between the stitches. Many laparoscopic surgeons have come to rely on bipolar energy or ultrasonic devices to coagulate vessels. But when dealing with huge vessels, a return to basics using laparoscopic suturing will greatly benefit the patient and the surgeon by reducing blood loss and operative time.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Dr. Lum responds

I thank Dr. Zisow for his thoughtful comments. I agree that laparoscopic suturing is an essential skill that can be utilized to suture ligate vessels. If we consider the basics of an open hysterectomy, the uterine artery is clamped first, then suture ligated. When approaching a very large vessel during TLH, I would be concerned that a simple suture around a large vessel might tear through and cause more bleeding. To mitigate this risk, the vessel can be clamped with a grasper first, similar to the approach in an open hysterectomy. However, once a vessel is compressed, a sealing device can usually work just as well as a suture. It becomes a matter of preference and cost.

During hysterectomy of a very large uterus, a big challenge is managing bleeding of the uterus itself during manipulation from above. Bleeding from the vascular sinuses of the myometrium can be brisk and obscure visualization, potentially leading to laparotomy conversion. A common misconception is that uterine artery embolization is equivalent to suturing the uterine arteries. In actuality, the goal of a uterine artery embolization is to embolize the distal branches of the uterine arteries, which can help with any potential bleeding from the uterus itself during hysterectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Laparoscopic suturing is an option

Dr. Lum presented a nicely produced video demonstrating various strategies aimed at facilitating total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus. Her patient’s evaluation included magnetic resonance imaging. In the video, she demonstrates a variety of interventions, including the use of a preoperative gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GNRH) agonist and immediate perioperative radial artery–uterine artery embolization. Intraoperative techniques include use of ureteral stents and securing the uterine arteries at their origins.

Clearly, TLH of a huge uterus is a technical challenge. However, I’d like to suggest that a relatively basic and important skill would greatly assist in such procedures and likely obviate the need for a GNRH agonist and/or uterine artery embolization. The vessel-sealing devices shown in the video are generally not capable of sealing such large vessels adequately, and this is what leads to the massive hemorrhaging that often occurs.

Laparoscopic suturing with extracorporeal knot tying can be used effectively to control the extremely large vessels associated with a huge uterus. The judicious placement of sutures can completely control such vessels and prevent bleeding from both proximal and distal ends when 2 sutures are placed and the vessels are transected between the stitches. Many laparoscopic surgeons have come to rely on bipolar energy or ultrasonic devices to coagulate vessels. But when dealing with huge vessels, a return to basics using laparoscopic suturing will greatly benefit the patient and the surgeon by reducing blood loss and operative time.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Dr. Lum responds

I thank Dr. Zisow for his thoughtful comments. I agree that laparoscopic suturing is an essential skill that can be utilized to suture ligate vessels. If we consider the basics of an open hysterectomy, the uterine artery is clamped first, then suture ligated. When approaching a very large vessel during TLH, I would be concerned that a simple suture around a large vessel might tear through and cause more bleeding. To mitigate this risk, the vessel can be clamped with a grasper first, similar to the approach in an open hysterectomy. However, once a vessel is compressed, a sealing device can usually work just as well as a suture. It becomes a matter of preference and cost.

During hysterectomy of a very large uterus, a big challenge is managing bleeding of the uterus itself during manipulation from above. Bleeding from the vascular sinuses of the myometrium can be brisk and obscure visualization, potentially leading to laparotomy conversion. A common misconception is that uterine artery embolization is equivalent to suturing the uterine arteries. In actuality, the goal of a uterine artery embolization is to embolize the distal branches of the uterine arteries, which can help with any potential bleeding from the uterus itself during hysterectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Admission eosinopenia predicted severe CDI outcomes

For patients with even in the absence of hypotension and tachycardia, researchers wrote in JAMA Surgery.

“In animal models, peripheral eosinopenia is a biologically plausible predictive factor for adverse outcomes, and human data from this study indicate that this frequent addition to an admission complete blood cell count is an inexpensive, widely available risk index in the treatment of C. difficile infection,” wrote Audrey S. Kulaylat, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and her associates.

In their cohort study of 2,065 patients admitted to two tertiary referral centers with C. difficile infection, undetectable eosinophil counts at hospital admission were associated with significantly increased odds of in-hospital mortality in both a training dataset (odds ratio, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-3.73; P = .03) and a validation dataset (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.33-3.83; P = .002). Undetectable eosinophil counts also were associated with elevated odds of severe disease requiring intensive care, vasopressor use, and emergency total colectomy. Besides eosinopenia, significant predictors of mortality included having more comorbidities and lower systolic blood pressure at admission. Strikingly, when patients had no initial hypotension or tachycardia, an undetectable eosinophil count was the only identifiable predictor of in-hospital death (OR, 5.76; 95% CI, 1.99-16.64). An elevated white blood cell count was not a significant predictor of mortality in this subgroup.

Dr. Kulaylat and her associates are studying the microbiome in C. difficile infection. Their work has identified a host immune reaction marked by an “exaggerated inflammasome response” and peripheral eosinopenia, they explained. Two recent murine models have produced similar results.

Admission eosinophil counts “allow for an immediate assessment of mortality risk at admission that is inexpensive and part of a differential for a standard complete blood count available at any hospital,” they concluded. They are now prospectively evaluating a prognostic score for C. difficile infection that includes eosinopenia and other easily discernible admission factors. The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kulaylat AS et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Sep 12. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3174.

For patients with even in the absence of hypotension and tachycardia, researchers wrote in JAMA Surgery.

“In animal models, peripheral eosinopenia is a biologically plausible predictive factor for adverse outcomes, and human data from this study indicate that this frequent addition to an admission complete blood cell count is an inexpensive, widely available risk index in the treatment of C. difficile infection,” wrote Audrey S. Kulaylat, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and her associates.

In their cohort study of 2,065 patients admitted to two tertiary referral centers with C. difficile infection, undetectable eosinophil counts at hospital admission were associated with significantly increased odds of in-hospital mortality in both a training dataset (odds ratio, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-3.73; P = .03) and a validation dataset (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.33-3.83; P = .002). Undetectable eosinophil counts also were associated with elevated odds of severe disease requiring intensive care, vasopressor use, and emergency total colectomy. Besides eosinopenia, significant predictors of mortality included having more comorbidities and lower systolic blood pressure at admission. Strikingly, when patients had no initial hypotension or tachycardia, an undetectable eosinophil count was the only identifiable predictor of in-hospital death (OR, 5.76; 95% CI, 1.99-16.64). An elevated white blood cell count was not a significant predictor of mortality in this subgroup.

Dr. Kulaylat and her associates are studying the microbiome in C. difficile infection. Their work has identified a host immune reaction marked by an “exaggerated inflammasome response” and peripheral eosinopenia, they explained. Two recent murine models have produced similar results.

Admission eosinophil counts “allow for an immediate assessment of mortality risk at admission that is inexpensive and part of a differential for a standard complete blood count available at any hospital,” they concluded. They are now prospectively evaluating a prognostic score for C. difficile infection that includes eosinopenia and other easily discernible admission factors. The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kulaylat AS et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Sep 12. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3174.

For patients with even in the absence of hypotension and tachycardia, researchers wrote in JAMA Surgery.

“In animal models, peripheral eosinopenia is a biologically plausible predictive factor for adverse outcomes, and human data from this study indicate that this frequent addition to an admission complete blood cell count is an inexpensive, widely available risk index in the treatment of C. difficile infection,” wrote Audrey S. Kulaylat, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and her associates.

In their cohort study of 2,065 patients admitted to two tertiary referral centers with C. difficile infection, undetectable eosinophil counts at hospital admission were associated with significantly increased odds of in-hospital mortality in both a training dataset (odds ratio, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-3.73; P = .03) and a validation dataset (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.33-3.83; P = .002). Undetectable eosinophil counts also were associated with elevated odds of severe disease requiring intensive care, vasopressor use, and emergency total colectomy. Besides eosinopenia, significant predictors of mortality included having more comorbidities and lower systolic blood pressure at admission. Strikingly, when patients had no initial hypotension or tachycardia, an undetectable eosinophil count was the only identifiable predictor of in-hospital death (OR, 5.76; 95% CI, 1.99-16.64). An elevated white blood cell count was not a significant predictor of mortality in this subgroup.

Dr. Kulaylat and her associates are studying the microbiome in C. difficile infection. Their work has identified a host immune reaction marked by an “exaggerated inflammasome response” and peripheral eosinopenia, they explained. Two recent murine models have produced similar results.

Admission eosinophil counts “allow for an immediate assessment of mortality risk at admission that is inexpensive and part of a differential for a standard complete blood count available at any hospital,” they concluded. They are now prospectively evaluating a prognostic score for C. difficile infection that includes eosinopenia and other easily discernible admission factors. The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kulaylat AS et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Sep 12. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3174.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Undetectable peripheral eosinophils predicted severe outcomes in patients admitted with Clostridium difficile infection.

Major finding: In the training and validation datasets, odds of in-hospital mortality were 2.01 (95% CI, 1.08-3.73) and 2.26 (95% CI, 1.33-3.83), respectively.

Study details: Two-hospital cohort study of 2,065 patients admitted with C. difficile infection.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kulaylat A et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Sep 12. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3174.

Five-year follow-up confirms safety of antibiotics for uncomplicated appendicitis

Longer-term outcomes of treating uncomplicated acute appendicitis with antibiotics suggest it is a feasible alternative to appendectomy.

Researchers have presented the 5-year follow-up data from the Appendicitis Acuta (APPAC) multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing appendectomy with antibiotic therapy in 530 patients.

They found that 39.1% (100) of the 257 patients randomized to antibiotic therapy – 3 days of intravenous ertapenem followed by 7 days of oral levofloxacin and metronidazole – experienced a recurrence of appendicitis within 5 years and subsequently had surgery.

However the authors noted that seven of these patients were later found not to have appendicitis, so the true success rate for antibiotic treatment was actually 63.7%.

Seventy of the patients who experienced a recurrence underwent surgery in the first year after randomization, 17 in the second year, 3 in the third year, 5 in the fourth year, and the remaining 5 patients in the fifth year, the authors wrote in an article published in JAMA.

However the overall complication rate was similar in patients who were randomized to undergo appendectomy and in those who were initially randomized to the antibiotic group but later experienced a recurrence and underwent surgery.

“No patient initially treated with antibiotics, who ultimately developed recurrent appendicitis, had any complications related to the delay in surgery,” wrote Paulina Salminen, MD, from Turku (Finland) University Hospital and coauthors. “Nearly two-thirds of all patients who initially presented with uncomplicated appendicitis were successfully treated with antibiotics alone, and those who ultimately developed recurrent disease did not experience any adverse outcomes related to the delay in appendectomy.”

Of the 100 patients randomized to antibiotics who underwent appendectomy after a recurrence, 15 were operated on when they were first hospitalized at study admission.

The authors commented that the study design allowed for surgeons to exercise their clinical judgment in choosing when to perform an appendectomy on patients in the antibiotic group, because antibiotics alone was not considered acceptable treatment for appendicitis.

“This led to some patients undergoing appendectomy who did not have appendicitis or who might have been successfully treated with antibiotics or an another course of antibiotics,” they wrote. “Future studies should investigate protocols for further imaging or antibiotic treatment for patients who develop recurrent appendicitis after they were initially treated with antibiotics.”

In the recurrence group, the majority were found to have uncomplicated appendicitis, but complicated appendicitis was seen in two patients between 2 and 5 years after the index admission.

There was a significant 17.9% higher complication rate in the appendectomy group, compared with the antibiotic group – 24.4% versus 6.5% – at 5 years and two patients in the appendectomy group had severe complications requiring reoperation.

They suggested that the higher complication rate with surgery, which was mostly attributable to infections, could be reduced by the use of laparoscopic appendectomy, which is also associated with faster recovery.

The median length of hospital stay was 3 days for both the appendectomy group and the antibiotics-only group, but patients randomized to appendectomy took a median of 22 days of sick leave, compared with 11 days for those randomized to antibiotics (P less than .001).

In the absence of standard protocol on treating appendicitis with antibiotics, the authors noted that they took a conservative approach, using broad-spectrum antibiotics and keeping patients in hospital for 3 days for observation.

“The success of antibiotic treatment for appendicitis calls into question prior beliefs that appendicitis inevitably results in serious intra-abdominal infection if appendectomy is not performed.”

The study was supported by the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation, the EVO Foundation, and Turku University. One author declared lecture fees from three pharmaceutical companies but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Salminen P et al. JAMA 2018;320:1259-65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13201.

“When the earlier results of the APPAC trial were published, showing that 73% of patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis did not require surgery at 1 year of follow-up, critics raised concerns that many more of these patients would eventually require surgery,” wrote Edward H. Livingston, MD, deputy editor of JAMA in an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2018;320:1245-46).Surgeons have since been waiting until longer-term outcomes were known. These 5-year results are supportive of the antibiotics approach. “They show no increase in major complications in patients who experienced a recurrence and underwent appendectomy after initially being randomized to antibiotic therapy. They challenge the notion that uncomplicated acute appendicitis is a surgical emergency and show that nonsurgical treatment is a reasonable option,” Dr Livingston wrote.

He declared no conflicts of interest.

“When the earlier results of the APPAC trial were published, showing that 73% of patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis did not require surgery at 1 year of follow-up, critics raised concerns that many more of these patients would eventually require surgery,” wrote Edward H. Livingston, MD, deputy editor of JAMA in an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2018;320:1245-46).Surgeons have since been waiting until longer-term outcomes were known. These 5-year results are supportive of the antibiotics approach. “They show no increase in major complications in patients who experienced a recurrence and underwent appendectomy after initially being randomized to antibiotic therapy. They challenge the notion that uncomplicated acute appendicitis is a surgical emergency and show that nonsurgical treatment is a reasonable option,” Dr Livingston wrote.

He declared no conflicts of interest.

“When the earlier results of the APPAC trial were published, showing that 73% of patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis did not require surgery at 1 year of follow-up, critics raised concerns that many more of these patients would eventually require surgery,” wrote Edward H. Livingston, MD, deputy editor of JAMA in an accompanying editorial (JAMA 2018;320:1245-46).Surgeons have since been waiting until longer-term outcomes were known. These 5-year results are supportive of the antibiotics approach. “They show no increase in major complications in patients who experienced a recurrence and underwent appendectomy after initially being randomized to antibiotic therapy. They challenge the notion that uncomplicated acute appendicitis is a surgical emergency and show that nonsurgical treatment is a reasonable option,” Dr Livingston wrote.

He declared no conflicts of interest.

Longer-term outcomes of treating uncomplicated acute appendicitis with antibiotics suggest it is a feasible alternative to appendectomy.

Researchers have presented the 5-year follow-up data from the Appendicitis Acuta (APPAC) multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing appendectomy with antibiotic therapy in 530 patients.

They found that 39.1% (100) of the 257 patients randomized to antibiotic therapy – 3 days of intravenous ertapenem followed by 7 days of oral levofloxacin and metronidazole – experienced a recurrence of appendicitis within 5 years and subsequently had surgery.

However the authors noted that seven of these patients were later found not to have appendicitis, so the true success rate for antibiotic treatment was actually 63.7%.

Seventy of the patients who experienced a recurrence underwent surgery in the first year after randomization, 17 in the second year, 3 in the third year, 5 in the fourth year, and the remaining 5 patients in the fifth year, the authors wrote in an article published in JAMA.

However the overall complication rate was similar in patients who were randomized to undergo appendectomy and in those who were initially randomized to the antibiotic group but later experienced a recurrence and underwent surgery.

“No patient initially treated with antibiotics, who ultimately developed recurrent appendicitis, had any complications related to the delay in surgery,” wrote Paulina Salminen, MD, from Turku (Finland) University Hospital and coauthors. “Nearly two-thirds of all patients who initially presented with uncomplicated appendicitis were successfully treated with antibiotics alone, and those who ultimately developed recurrent disease did not experience any adverse outcomes related to the delay in appendectomy.”

Of the 100 patients randomized to antibiotics who underwent appendectomy after a recurrence, 15 were operated on when they were first hospitalized at study admission.

The authors commented that the study design allowed for surgeons to exercise their clinical judgment in choosing when to perform an appendectomy on patients in the antibiotic group, because antibiotics alone was not considered acceptable treatment for appendicitis.

“This led to some patients undergoing appendectomy who did not have appendicitis or who might have been successfully treated with antibiotics or an another course of antibiotics,” they wrote. “Future studies should investigate protocols for further imaging or antibiotic treatment for patients who develop recurrent appendicitis after they were initially treated with antibiotics.”

In the recurrence group, the majority were found to have uncomplicated appendicitis, but complicated appendicitis was seen in two patients between 2 and 5 years after the index admission.

There was a significant 17.9% higher complication rate in the appendectomy group, compared with the antibiotic group – 24.4% versus 6.5% – at 5 years and two patients in the appendectomy group had severe complications requiring reoperation.

They suggested that the higher complication rate with surgery, which was mostly attributable to infections, could be reduced by the use of laparoscopic appendectomy, which is also associated with faster recovery.

The median length of hospital stay was 3 days for both the appendectomy group and the antibiotics-only group, but patients randomized to appendectomy took a median of 22 days of sick leave, compared with 11 days for those randomized to antibiotics (P less than .001).

In the absence of standard protocol on treating appendicitis with antibiotics, the authors noted that they took a conservative approach, using broad-spectrum antibiotics and keeping patients in hospital for 3 days for observation.

“The success of antibiotic treatment for appendicitis calls into question prior beliefs that appendicitis inevitably results in serious intra-abdominal infection if appendectomy is not performed.”

The study was supported by the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation, the EVO Foundation, and Turku University. One author declared lecture fees from three pharmaceutical companies but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Salminen P et al. JAMA 2018;320:1259-65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13201.

Longer-term outcomes of treating uncomplicated acute appendicitis with antibiotics suggest it is a feasible alternative to appendectomy.

Researchers have presented the 5-year follow-up data from the Appendicitis Acuta (APPAC) multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing appendectomy with antibiotic therapy in 530 patients.

They found that 39.1% (100) of the 257 patients randomized to antibiotic therapy – 3 days of intravenous ertapenem followed by 7 days of oral levofloxacin and metronidazole – experienced a recurrence of appendicitis within 5 years and subsequently had surgery.

However the authors noted that seven of these patients were later found not to have appendicitis, so the true success rate for antibiotic treatment was actually 63.7%.

Seventy of the patients who experienced a recurrence underwent surgery in the first year after randomization, 17 in the second year, 3 in the third year, 5 in the fourth year, and the remaining 5 patients in the fifth year, the authors wrote in an article published in JAMA.

However the overall complication rate was similar in patients who were randomized to undergo appendectomy and in those who were initially randomized to the antibiotic group but later experienced a recurrence and underwent surgery.

“No patient initially treated with antibiotics, who ultimately developed recurrent appendicitis, had any complications related to the delay in surgery,” wrote Paulina Salminen, MD, from Turku (Finland) University Hospital and coauthors. “Nearly two-thirds of all patients who initially presented with uncomplicated appendicitis were successfully treated with antibiotics alone, and those who ultimately developed recurrent disease did not experience any adverse outcomes related to the delay in appendectomy.”

Of the 100 patients randomized to antibiotics who underwent appendectomy after a recurrence, 15 were operated on when they were first hospitalized at study admission.

The authors commented that the study design allowed for surgeons to exercise their clinical judgment in choosing when to perform an appendectomy on patients in the antibiotic group, because antibiotics alone was not considered acceptable treatment for appendicitis.

“This led to some patients undergoing appendectomy who did not have appendicitis or who might have been successfully treated with antibiotics or an another course of antibiotics,” they wrote. “Future studies should investigate protocols for further imaging or antibiotic treatment for patients who develop recurrent appendicitis after they were initially treated with antibiotics.”

In the recurrence group, the majority were found to have uncomplicated appendicitis, but complicated appendicitis was seen in two patients between 2 and 5 years after the index admission.

There was a significant 17.9% higher complication rate in the appendectomy group, compared with the antibiotic group – 24.4% versus 6.5% – at 5 years and two patients in the appendectomy group had severe complications requiring reoperation.

They suggested that the higher complication rate with surgery, which was mostly attributable to infections, could be reduced by the use of laparoscopic appendectomy, which is also associated with faster recovery.

The median length of hospital stay was 3 days for both the appendectomy group and the antibiotics-only group, but patients randomized to appendectomy took a median of 22 days of sick leave, compared with 11 days for those randomized to antibiotics (P less than .001).

In the absence of standard protocol on treating appendicitis with antibiotics, the authors noted that they took a conservative approach, using broad-spectrum antibiotics and keeping patients in hospital for 3 days for observation.

“The success of antibiotic treatment for appendicitis calls into question prior beliefs that appendicitis inevitably results in serious intra-abdominal infection if appendectomy is not performed.”

The study was supported by the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation, the EVO Foundation, and Turku University. One author declared lecture fees from three pharmaceutical companies but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Salminen P et al. JAMA 2018;320:1259-65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13201.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Antibiotics could be used as an alternative to surgery for uncomplicated acute appendicitis.

Major finding: Around two-thirds of patients with acute appendicitis treated with antibiotics only did not experience a recurrence in 5 years.

Study details: Randomized controlled study in 530 patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation, the EVO Foundation, and Turku University. One author declared lecture fees from three pharmaceutical companies but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Salminen P et al. JAMA 2018;320:1259-65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13201.

Sustainability of Ambulatory Safety Event Reporting Improvement After Intervention Discontinuation

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC (Dr. C

Abstract

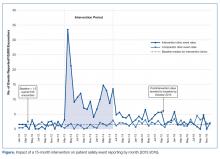

- Objective: An educational intervention stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly regular audit and feedback led to significantly increased reporting of safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting during a 15-month intervention period. We assessed whether these increased reporting rates would be sustained during the 30-month period after the intervention was discontinued.

- Methods: We reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016, and selected 6 clinics that comprised the intervention collaborative and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match) that comprised the comparator group. To test the changes in safety event reporting (SER) rates between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative, interrupted time series analysis with a control group was performed.

- Results: The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. Following discontinuation of regular auditing and feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention.

- Conclusion: It is likely that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Keywords: patient safety; safety event reporting; voluntary reporting system; risk management; ambulatory clinic.

We have previously shown that patient safety reporting rates for a 6-practice collaborative group in our non-academic community clinics increased 10-fold after we implemented an improvement initiative consisting of an initial education session followed by provision of monthly audit and written and in-person feedback [1]. The intervention was implemented for 15 months, and after discontinuation of the intervention we have continued to monitor reporting rates. Our objective was to assess whether the increased reporting rates observed in this collaborative during the intervention period would be sustained for 30 months following the intervention.

Methods

This study’s methods have been described in detail previously [1]. For this improvement initiative, we reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016. We identified 6 clinics, the intervention collaborative, in family medicine (n = 3), pediatrics (n = 2), and general surgery (n = 1), and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match), the comparator group [1]. For the intervention collaborative only, we provided an initial 1-hour educational session on safety events with a listing of all safety event types, along with a 1-page reporting form for voluntary, anonymous submission, with use of the term “safety event” rather than “ error,” to support a nonpunitive culture. After the educational session, we provided monthly audit and written and in-person feedback with peer comparison data by clinic. Monthly audit and feedback continued throughout the intervention and was discontinued postintervention. For event reporting, in our inpatient and outpatient facilities we used VIncident (Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC) for the period 2012–2015 and RL6: Risk (RL Solutions, Toronto, ON) for 2016.

The baseline period was 15 months (January 2012–March 2013), the intervention period was 15 months (April 2013–June 2014), and the postintervention period was 30 months (July 2014–December 2016). All 24 clinics were monitored for the 60-month period.

To test the changes in the rate of safety event reporting (SER) between the pre-intervention and postintervention periods and between the intervention and the postintervention periods, interrupted time series (ITS) analysis with a control group was performed using PROC AUTOREG in SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Because SER rates are reported monthly, ITS analysis was used to control for autocorrelation, nonstationary variance, seasonality, and trends [2,3].

Results

The SER rate was assessed monthly, so the number of SER rates for each group (intervention and comparator) was 15 during the pre-intervention and intervention periods, respectively, and 30 during the postintervention period. During the pre-intervention period, the intervention collaborative’s baseline median rate of safety events reported was 1.5 per 10,000 patient encounters (Figure). Also, for the intervention collaborative, the pre-intervention baseline mean (standard deviation, SD) SER rate (per 10,000 patient encounters by month) was 1.3 (1.2), the intervention mean SER rate was 12.0 (7.3), and the postintervention rate was 3.2 (1.8). Based on the ITS analysis, there was a significant change in the SER rate between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative (P = 0.01).

The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. After discontinuation of feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention (Figure). The postintervention SER rate was also significantly higher than the pre-intervention rate (P = 0.001).

For the comparator clinics, no significant change in SER rates occurred for the 3 time periods.

Discussion

In this initiative with a 5-year reporting window, we had previously shown that with education and prospective audit and feedback, we could achieve a 10-fold increase in patient SER rates among a multi-practice collaborative while the intervention was maintained [1]. Even though there was a modest but significant increase in the SER rate in the postintervention period for the 6-clinic intervention collaborative compared to baseline, the substantial gains seen during the course of the intervention were not maintained when monthly audit and feedback ceased and monitoring continued for 30 months.

Limitations of this study include possible selection bias resulting from including clinics felt likely to participate rather than identifying clinics in a random fashion. In addition, we did not attempt to determine the specific reasons for the decrease in reporting among these clinics.

The few studies of ambulatory SER do not adequately address the effect of intervention cessation, but researchers who implemented other ambulatory quality improvement efforts have reported that gains often deteriorate or revert to baseline without consistent, ongoing feedback [4]. Likewise, in hospital-based residency programs, a multifaceted approach that includes feedback can increase SER rates, but it is uncertain if the success of this approach can be maintained long-term without continuing feedback of some type [5–7].

There are likely many factors influencing SER in ambulatory clinics, many of which are also applicable in the hospital setting. These include ease of reporting, knowing what events to report, confidentiality of reporting, and the belief that reporting makes a difference in enhancing patient safety [8]. A strong culture of safety in ambulatory clinics may lead to enhanced voluntary SER [9], and a nonpunitive, team-based approach has been advocated to promote reporting and improve ambulatory safety [10]. Historically, our ambulatory medical group clinics have had a strong culture of safety and, with patient safety coaches present in all of our clinics, we have supported a nonpunitive, team-based approach to SER [11].

In our intervention, we made reporting safety events easy, reporters knew which events to report, events could be reported anonymously, and reporters were rewarded, at least with data feedback, for reporting. The only factor known to have changed was discontinuation of monthly feedback. Which factors are most important could not be determined by our work, but we strongly suspect that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Clegg HW, Cardwell T, West AM, Ferrell F. Improved safety event reporting in outpatient, nonacademic practices with an anonymous, nonpunitive approach. J Clin Outcomes Manag 2015;22:66–72.

2. Newland JG, Stach LM, De Lurgio SA, et al. Impact of a prospective-audit-with-feedback antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2012; 1:179–86.

3. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr 2013;13 (6 Suppl):S38–44.

4. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

5. Steen S, Jaeger C, Price L, Griffen D. Increasing patient safety event reporting in an emergency medicine residency. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2017;6(1).

6. Fox M, Bump G, Butler G, et al. Making residents part of the safety culture: improving error reporting and reducing harms. J Patient Saf 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Dunbar AE 3rd, Cupit M, Vath RJ, et al. An improvement approach to integrate teaching teams in the reporting of safety events. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20153807.

8. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academies. www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf Published November 1999. Accessed August 22, 2018.

9. Miller N, Bhowmik S, Ezinwa M, et al. The relationship between safety culture and voluntary event reporting in a large regional ambulatory care group. J Patient Saf 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

10. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

11. West AM, Cardwell T, Clegg HW. Improving patient safety culture through patient safety coaches in the ambulatory setting. Presented at: Institute for Healthcare Improvement Annual Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community; March 2015; Dallas, Texas.

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC (Dr. C

Abstract

- Objective: An educational intervention stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly regular audit and feedback led to significantly increased reporting of safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting during a 15-month intervention period. We assessed whether these increased reporting rates would be sustained during the 30-month period after the intervention was discontinued.

- Methods: We reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016, and selected 6 clinics that comprised the intervention collaborative and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match) that comprised the comparator group. To test the changes in safety event reporting (SER) rates between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative, interrupted time series analysis with a control group was performed.

- Results: The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. Following discontinuation of regular auditing and feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention.

- Conclusion: It is likely that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Keywords: patient safety; safety event reporting; voluntary reporting system; risk management; ambulatory clinic.

We have previously shown that patient safety reporting rates for a 6-practice collaborative group in our non-academic community clinics increased 10-fold after we implemented an improvement initiative consisting of an initial education session followed by provision of monthly audit and written and in-person feedback [1]. The intervention was implemented for 15 months, and after discontinuation of the intervention we have continued to monitor reporting rates. Our objective was to assess whether the increased reporting rates observed in this collaborative during the intervention period would be sustained for 30 months following the intervention.

Methods

This study’s methods have been described in detail previously [1]. For this improvement initiative, we reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016. We identified 6 clinics, the intervention collaborative, in family medicine (n = 3), pediatrics (n = 2), and general surgery (n = 1), and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match), the comparator group [1]. For the intervention collaborative only, we provided an initial 1-hour educational session on safety events with a listing of all safety event types, along with a 1-page reporting form for voluntary, anonymous submission, with use of the term “safety event” rather than “ error,” to support a nonpunitive culture. After the educational session, we provided monthly audit and written and in-person feedback with peer comparison data by clinic. Monthly audit and feedback continued throughout the intervention and was discontinued postintervention. For event reporting, in our inpatient and outpatient facilities we used VIncident (Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC) for the period 2012–2015 and RL6: Risk (RL Solutions, Toronto, ON) for 2016.

The baseline period was 15 months (January 2012–March 2013), the intervention period was 15 months (April 2013–June 2014), and the postintervention period was 30 months (July 2014–December 2016). All 24 clinics were monitored for the 60-month period.

To test the changes in the rate of safety event reporting (SER) between the pre-intervention and postintervention periods and between the intervention and the postintervention periods, interrupted time series (ITS) analysis with a control group was performed using PROC AUTOREG in SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Because SER rates are reported monthly, ITS analysis was used to control for autocorrelation, nonstationary variance, seasonality, and trends [2,3].

Results

The SER rate was assessed monthly, so the number of SER rates for each group (intervention and comparator) was 15 during the pre-intervention and intervention periods, respectively, and 30 during the postintervention period. During the pre-intervention period, the intervention collaborative’s baseline median rate of safety events reported was 1.5 per 10,000 patient encounters (Figure). Also, for the intervention collaborative, the pre-intervention baseline mean (standard deviation, SD) SER rate (per 10,000 patient encounters by month) was 1.3 (1.2), the intervention mean SER rate was 12.0 (7.3), and the postintervention rate was 3.2 (1.8). Based on the ITS analysis, there was a significant change in the SER rate between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative (P = 0.01).

The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. After discontinuation of feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention (Figure). The postintervention SER rate was also significantly higher than the pre-intervention rate (P = 0.001).

For the comparator clinics, no significant change in SER rates occurred for the 3 time periods.

Discussion

In this initiative with a 5-year reporting window, we had previously shown that with education and prospective audit and feedback, we could achieve a 10-fold increase in patient SER rates among a multi-practice collaborative while the intervention was maintained [1]. Even though there was a modest but significant increase in the SER rate in the postintervention period for the 6-clinic intervention collaborative compared to baseline, the substantial gains seen during the course of the intervention were not maintained when monthly audit and feedback ceased and monitoring continued for 30 months.

Limitations of this study include possible selection bias resulting from including clinics felt likely to participate rather than identifying clinics in a random fashion. In addition, we did not attempt to determine the specific reasons for the decrease in reporting among these clinics.

The few studies of ambulatory SER do not adequately address the effect of intervention cessation, but researchers who implemented other ambulatory quality improvement efforts have reported that gains often deteriorate or revert to baseline without consistent, ongoing feedback [4]. Likewise, in hospital-based residency programs, a multifaceted approach that includes feedback can increase SER rates, but it is uncertain if the success of this approach can be maintained long-term without continuing feedback of some type [5–7].

There are likely many factors influencing SER in ambulatory clinics, many of which are also applicable in the hospital setting. These include ease of reporting, knowing what events to report, confidentiality of reporting, and the belief that reporting makes a difference in enhancing patient safety [8]. A strong culture of safety in ambulatory clinics may lead to enhanced voluntary SER [9], and a nonpunitive, team-based approach has been advocated to promote reporting and improve ambulatory safety [10]. Historically, our ambulatory medical group clinics have had a strong culture of safety and, with patient safety coaches present in all of our clinics, we have supported a nonpunitive, team-based approach to SER [11].

In our intervention, we made reporting safety events easy, reporters knew which events to report, events could be reported anonymously, and reporters were rewarded, at least with data feedback, for reporting. The only factor known to have changed was discontinuation of monthly feedback. Which factors are most important could not be determined by our work, but we strongly suspect that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC (Dr. C

Abstract

- Objective: An educational intervention stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly regular audit and feedback led to significantly increased reporting of safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting during a 15-month intervention period. We assessed whether these increased reporting rates would be sustained during the 30-month period after the intervention was discontinued.

- Methods: We reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016, and selected 6 clinics that comprised the intervention collaborative and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match) that comprised the comparator group. To test the changes in safety event reporting (SER) rates between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative, interrupted time series analysis with a control group was performed.

- Results: The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. Following discontinuation of regular auditing and feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention.

- Conclusion: It is likely that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Keywords: patient safety; safety event reporting; voluntary reporting system; risk management; ambulatory clinic.

We have previously shown that patient safety reporting rates for a 6-practice collaborative group in our non-academic community clinics increased 10-fold after we implemented an improvement initiative consisting of an initial education session followed by provision of monthly audit and written and in-person feedback [1]. The intervention was implemented for 15 months, and after discontinuation of the intervention we have continued to monitor reporting rates. Our objective was to assess whether the increased reporting rates observed in this collaborative during the intervention period would be sustained for 30 months following the intervention.

Methods

This study’s methods have been described in detail previously [1]. For this improvement initiative, we reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016. We identified 6 clinics, the intervention collaborative, in family medicine (n = 3), pediatrics (n = 2), and general surgery (n = 1), and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match), the comparator group [1]. For the intervention collaborative only, we provided an initial 1-hour educational session on safety events with a listing of all safety event types, along with a 1-page reporting form for voluntary, anonymous submission, with use of the term “safety event” rather than “ error,” to support a nonpunitive culture. After the educational session, we provided monthly audit and written and in-person feedback with peer comparison data by clinic. Monthly audit and feedback continued throughout the intervention and was discontinued postintervention. For event reporting, in our inpatient and outpatient facilities we used VIncident (Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC) for the period 2012–2015 and RL6: Risk (RL Solutions, Toronto, ON) for 2016.

The baseline period was 15 months (January 2012–March 2013), the intervention period was 15 months (April 2013–June 2014), and the postintervention period was 30 months (July 2014–December 2016). All 24 clinics were monitored for the 60-month period.