User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Compounded pain creams no better than placebo creams in localized chronic pain

Specially formulated topical pain creams are no better than placebo creams for relieving localized chronic pain, according to results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Study authors led by Robert E. Brutcher, PharmD, PhD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., said their findings published Feb. 4 in Annals of Internal Medicine suggest compounded pain creams should not be routinely used for chronic pain conditions.

The researchers noted that the use of compounded topical pain creams has increased dramatically despite “weak evidence” supporting their efficacy to treat localized pain, and this is particularly the case in military personnel, where the authors said treatments without central effect may be particularly beneficial because “opioid therapy may render a service member nondeployable and medications that affect the central nervous system may have a negative effect on judgment and motor skills.”

They noted a report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office that showed Tricare’s pharmacy benefits program paid $259 million for compounded medications in the 2013 fiscal year, a figure that increased to $746 million in 2014.

“The soaring costs, coupled with sparse efficacy data prompted the Defense Health Agency to evaluate this issue,” they wrote.

The objectives of the current study were to assess the efficacy of compounded pain creams for chronic pain conditions and determine whether efficacy differed for the various pain classifications.

“We hypothesized that, compared with placebo, compounded topical pain creams would provide greater pain relief and functional improvement,” they said.

The randomized trial involved 133 patients diagnosed with neuropathic pain, 133 with nociceptive pain, and 133 with mixed pain who had attended pain clinics at Walter Reed. Patients were aged between 18 and 90 years and had localized pain in the face, back or buttocks, neck, abdomen, chest, groin, or in up to two extremities. To be included in the study, they were also required to have an average pain score of 4 or greater on a 0- to 10-point numerical rating scale during the preceding week and have symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks.

Patients in all three pain subgroups were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either a compounded pain cream or a placebo cream. The authors noted that their “pain cream formulations were selected on the basis of accepted systemic indications for neuropathic and nociceptive pain.”

The formulation given to participants with neuropathic pain (n = 68) contained 10% ketamine, 6% gabapentin, 0.2% clonidine, and 2% lidocaine. The patients with nociceptive pain (n = 66) received a cream with 10% ketoprofen, 2% baclofen, 2% cyclobenzaprine, and 2% lidocaine. Those with mixed pain (n = 68) were given a cream containing 10% ketamine, 6% gabapentin, 3% diclofenac, 2% baclofen, 2% cyclobenzaprine, and 2% lidocaine. The authors said the concentrations of individual medications were based on previous trials that evaluated topical use.

The patients, who had a mean age across the groups that ranged from 48 to 57 years, applied cream to affected areas three times per day, with the amount dispensed determined by the size of the area experiencing pain. About half of the patients were women.

The primary outcome measures were an average pain score 1 month after treatment. A positive categorical response was a reduction in pain score of 2 or more points coupled with a score above 3 on a 5-point satisfaction scale. Secondary outcomes included Short Form-36 Health Survey scores, satisfaction, and categorical response. Participants with a positive outcome were followed to 3 months.

Change in the primary outcome of average pain score at 1 month did not differ between the active cream and placebo groups for any type of pain classification. The change was only –0.1 points (95% confidence interval, –0.8 to 0.5 points) for neuropathic pain, –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.9 to 0.2 points) for nociceptive pain, and –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.9 to 0.2 points) for mixed pain.

Among all patients combined, an overall change in average pain scores of –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.6 to 0.1 points) that favored the active-ingredient cream also did not differ between the treatment and placebo groups.

“The lower 95% confidence bounds for the 1-month between-group differences were all 0.9 points or less and excluded clinically meaningful benefits with the compounded topical pain cream,” the authors wrote.

Secondary outcomes also did not differ between the two study groups for any type of pain classification or for the entire cohort.

“Although participants in both treatment and control groups had improvement in their pain throughout the study, no significant differences were observed in pain scores, functional improvement, or satisfaction in the cohort or in any subgroup,” the authors concluded.

They noted that their findings were consistent with previous studies that also showed a lack of efficacy for most topical pain creams.

While some randomized trials have suggested positive findings for capsaicin, lidocaine, and NSAIDs, the authors noted that they did not find a similar benefit in their study population.

“Administered as stand-alone agents, lidocaine and NSAIDs may alleviate pain, although the effect size is small and the number needed to treat is large,” they wrote.

“Considering the increased costs of using a non–FDA-approved and regulated compounded cream rather than a single agent, we caution against routine use of compounded creams for chronic pain,” they wrote.

They noted that their study had several limitations, including that conventional treatments had failed in some of the participants before they enrolled in the study, increasing the likelihood that subsequent therapy would not be effective.

The authors suggested that future studies should aim to establish whether targeting specific types of pain or adding other agents like dimethyl sulfoxide would result in better outcomes.

The Centers for Rehabilitation Sciences Research in the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Health Agency funded the study. Two authors reported receiving grants and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Brutcher RE et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.7326/M18-2736.

Specially formulated topical pain creams are no better than placebo creams for relieving localized chronic pain, according to results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Study authors led by Robert E. Brutcher, PharmD, PhD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., said their findings published Feb. 4 in Annals of Internal Medicine suggest compounded pain creams should not be routinely used for chronic pain conditions.

The researchers noted that the use of compounded topical pain creams has increased dramatically despite “weak evidence” supporting their efficacy to treat localized pain, and this is particularly the case in military personnel, where the authors said treatments without central effect may be particularly beneficial because “opioid therapy may render a service member nondeployable and medications that affect the central nervous system may have a negative effect on judgment and motor skills.”

They noted a report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office that showed Tricare’s pharmacy benefits program paid $259 million for compounded medications in the 2013 fiscal year, a figure that increased to $746 million in 2014.

“The soaring costs, coupled with sparse efficacy data prompted the Defense Health Agency to evaluate this issue,” they wrote.

The objectives of the current study were to assess the efficacy of compounded pain creams for chronic pain conditions and determine whether efficacy differed for the various pain classifications.

“We hypothesized that, compared with placebo, compounded topical pain creams would provide greater pain relief and functional improvement,” they said.

The randomized trial involved 133 patients diagnosed with neuropathic pain, 133 with nociceptive pain, and 133 with mixed pain who had attended pain clinics at Walter Reed. Patients were aged between 18 and 90 years and had localized pain in the face, back or buttocks, neck, abdomen, chest, groin, or in up to two extremities. To be included in the study, they were also required to have an average pain score of 4 or greater on a 0- to 10-point numerical rating scale during the preceding week and have symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks.

Patients in all three pain subgroups were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either a compounded pain cream or a placebo cream. The authors noted that their “pain cream formulations were selected on the basis of accepted systemic indications for neuropathic and nociceptive pain.”

The formulation given to participants with neuropathic pain (n = 68) contained 10% ketamine, 6% gabapentin, 0.2% clonidine, and 2% lidocaine. The patients with nociceptive pain (n = 66) received a cream with 10% ketoprofen, 2% baclofen, 2% cyclobenzaprine, and 2% lidocaine. Those with mixed pain (n = 68) were given a cream containing 10% ketamine, 6% gabapentin, 3% diclofenac, 2% baclofen, 2% cyclobenzaprine, and 2% lidocaine. The authors said the concentrations of individual medications were based on previous trials that evaluated topical use.

The patients, who had a mean age across the groups that ranged from 48 to 57 years, applied cream to affected areas three times per day, with the amount dispensed determined by the size of the area experiencing pain. About half of the patients were women.

The primary outcome measures were an average pain score 1 month after treatment. A positive categorical response was a reduction in pain score of 2 or more points coupled with a score above 3 on a 5-point satisfaction scale. Secondary outcomes included Short Form-36 Health Survey scores, satisfaction, and categorical response. Participants with a positive outcome were followed to 3 months.

Change in the primary outcome of average pain score at 1 month did not differ between the active cream and placebo groups for any type of pain classification. The change was only –0.1 points (95% confidence interval, –0.8 to 0.5 points) for neuropathic pain, –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.9 to 0.2 points) for nociceptive pain, and –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.9 to 0.2 points) for mixed pain.

Among all patients combined, an overall change in average pain scores of –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.6 to 0.1 points) that favored the active-ingredient cream also did not differ between the treatment and placebo groups.

“The lower 95% confidence bounds for the 1-month between-group differences were all 0.9 points or less and excluded clinically meaningful benefits with the compounded topical pain cream,” the authors wrote.

Secondary outcomes also did not differ between the two study groups for any type of pain classification or for the entire cohort.

“Although participants in both treatment and control groups had improvement in their pain throughout the study, no significant differences were observed in pain scores, functional improvement, or satisfaction in the cohort or in any subgroup,” the authors concluded.

They noted that their findings were consistent with previous studies that also showed a lack of efficacy for most topical pain creams.

While some randomized trials have suggested positive findings for capsaicin, lidocaine, and NSAIDs, the authors noted that they did not find a similar benefit in their study population.

“Administered as stand-alone agents, lidocaine and NSAIDs may alleviate pain, although the effect size is small and the number needed to treat is large,” they wrote.

“Considering the increased costs of using a non–FDA-approved and regulated compounded cream rather than a single agent, we caution against routine use of compounded creams for chronic pain,” they wrote.

They noted that their study had several limitations, including that conventional treatments had failed in some of the participants before they enrolled in the study, increasing the likelihood that subsequent therapy would not be effective.

The authors suggested that future studies should aim to establish whether targeting specific types of pain or adding other agents like dimethyl sulfoxide would result in better outcomes.

The Centers for Rehabilitation Sciences Research in the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Health Agency funded the study. Two authors reported receiving grants and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Brutcher RE et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.7326/M18-2736.

Specially formulated topical pain creams are no better than placebo creams for relieving localized chronic pain, according to results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Study authors led by Robert E. Brutcher, PharmD, PhD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., said their findings published Feb. 4 in Annals of Internal Medicine suggest compounded pain creams should not be routinely used for chronic pain conditions.

The researchers noted that the use of compounded topical pain creams has increased dramatically despite “weak evidence” supporting their efficacy to treat localized pain, and this is particularly the case in military personnel, where the authors said treatments without central effect may be particularly beneficial because “opioid therapy may render a service member nondeployable and medications that affect the central nervous system may have a negative effect on judgment and motor skills.”

They noted a report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office that showed Tricare’s pharmacy benefits program paid $259 million for compounded medications in the 2013 fiscal year, a figure that increased to $746 million in 2014.

“The soaring costs, coupled with sparse efficacy data prompted the Defense Health Agency to evaluate this issue,” they wrote.

The objectives of the current study were to assess the efficacy of compounded pain creams for chronic pain conditions and determine whether efficacy differed for the various pain classifications.

“We hypothesized that, compared with placebo, compounded topical pain creams would provide greater pain relief and functional improvement,” they said.

The randomized trial involved 133 patients diagnosed with neuropathic pain, 133 with nociceptive pain, and 133 with mixed pain who had attended pain clinics at Walter Reed. Patients were aged between 18 and 90 years and had localized pain in the face, back or buttocks, neck, abdomen, chest, groin, or in up to two extremities. To be included in the study, they were also required to have an average pain score of 4 or greater on a 0- to 10-point numerical rating scale during the preceding week and have symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks.

Patients in all three pain subgroups were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either a compounded pain cream or a placebo cream. The authors noted that their “pain cream formulations were selected on the basis of accepted systemic indications for neuropathic and nociceptive pain.”

The formulation given to participants with neuropathic pain (n = 68) contained 10% ketamine, 6% gabapentin, 0.2% clonidine, and 2% lidocaine. The patients with nociceptive pain (n = 66) received a cream with 10% ketoprofen, 2% baclofen, 2% cyclobenzaprine, and 2% lidocaine. Those with mixed pain (n = 68) were given a cream containing 10% ketamine, 6% gabapentin, 3% diclofenac, 2% baclofen, 2% cyclobenzaprine, and 2% lidocaine. The authors said the concentrations of individual medications were based on previous trials that evaluated topical use.

The patients, who had a mean age across the groups that ranged from 48 to 57 years, applied cream to affected areas three times per day, with the amount dispensed determined by the size of the area experiencing pain. About half of the patients were women.

The primary outcome measures were an average pain score 1 month after treatment. A positive categorical response was a reduction in pain score of 2 or more points coupled with a score above 3 on a 5-point satisfaction scale. Secondary outcomes included Short Form-36 Health Survey scores, satisfaction, and categorical response. Participants with a positive outcome were followed to 3 months.

Change in the primary outcome of average pain score at 1 month did not differ between the active cream and placebo groups for any type of pain classification. The change was only –0.1 points (95% confidence interval, –0.8 to 0.5 points) for neuropathic pain, –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.9 to 0.2 points) for nociceptive pain, and –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.9 to 0.2 points) for mixed pain.

Among all patients combined, an overall change in average pain scores of –0.3 points (95% CI, –0.6 to 0.1 points) that favored the active-ingredient cream also did not differ between the treatment and placebo groups.

“The lower 95% confidence bounds for the 1-month between-group differences were all 0.9 points or less and excluded clinically meaningful benefits with the compounded topical pain cream,” the authors wrote.

Secondary outcomes also did not differ between the two study groups for any type of pain classification or for the entire cohort.

“Although participants in both treatment and control groups had improvement in their pain throughout the study, no significant differences were observed in pain scores, functional improvement, or satisfaction in the cohort or in any subgroup,” the authors concluded.

They noted that their findings were consistent with previous studies that also showed a lack of efficacy for most topical pain creams.

While some randomized trials have suggested positive findings for capsaicin, lidocaine, and NSAIDs, the authors noted that they did not find a similar benefit in their study population.

“Administered as stand-alone agents, lidocaine and NSAIDs may alleviate pain, although the effect size is small and the number needed to treat is large,” they wrote.

“Considering the increased costs of using a non–FDA-approved and regulated compounded cream rather than a single agent, we caution against routine use of compounded creams for chronic pain,” they wrote.

They noted that their study had several limitations, including that conventional treatments had failed in some of the participants before they enrolled in the study, increasing the likelihood that subsequent therapy would not be effective.

The authors suggested that future studies should aim to establish whether targeting specific types of pain or adding other agents like dimethyl sulfoxide would result in better outcomes.

The Centers for Rehabilitation Sciences Research in the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Health Agency funded the study. Two authors reported receiving grants and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Brutcher RE et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.7326/M18-2736.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Compounded pain creams should not be routinely used to treat chronic localized pain.

Major finding: At 1 month, the researchers found no significant differences in pain scores, functional improvement, or satisfaction between study participants with localized pain who had received specifically formulated pain creams and those who had received a placebo cream.

Study details: This double-blind, randomized, controlled trial involved 399 patients with localized pain who received either a pain cream specifically compounded for their type of pain – neuropathic, nociceptive, or mixed – or a placebo cream.

Disclosures: The Centers for Rehabilitation Sciences Research in the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Health Agency funded the study. Two authors reported receiving grants and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Brutcher RE et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.7326/M18-2736.

One person’s snake oil is another’s improved bottom line

“I’d be a millionaire if I could get rid of my conscience.”

A friend of mine in obstetrics said that yesterday. We were talking about the various quackery products pushed over the Internet and in some stores. These things claim to heal anything from Parkinson’s disease to a broken heart, and are generally sold by someone without real medical training. Generally, they also include some comment about this being a cure that doctors are hiding from you.

Of course, all of this is untrue. If there were actually cure for some horrible neurologic disease, I’d be thrilled to prescribe it. I’m here to reduce suffering, not prolong it.

I get it. People want to believe there’s hope when there is none. Even if it’s just something like forgetting a broken relationship, they want to believe there’s a way to make it happen quickly and painlessly.

It would be nice if it worked that way, but it doesn’t. Worse, people in these unfortunate medical or emotional situations are often vulnerable to these sales pitches, and there’s no shortage of unscrupulous individuals willing to prey on them.

What bothers me most in these cases is when doctors, with training similar to mine, push these “remedies.” Often they’re sold in a case in the waiting room and recommended during the visit. I assume these physicians either have lost their conscience and don’t care, or over time have somehow convinced themselves that what they’re doing is right.

Having a doctor selling or endorsing such a product gives it a credibility that it usually won’t get from an average Internet huckster, even if it’s for the same thing.

I’m sure some doctors have convinced themselves that the product is harmless, and therefore falls under primum non nocere. But being harmless isn’t the same as being effective, which is what the patient wants.

Like my friend said, with the financial pressures modern physicians are under, it’s easy to look at things like this as a way to improve cash flow and the bottom line. But you can’t lose sight of the patients. They’re why we are here, and selling them a product that will do them no good isn’t right.

Hippocrates’ “Do no harm” is a key part of being a doctor, but Jiminy Cricket’s “always let your conscience be your guide” is part of being a good doctor. We should never forget that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I’d be a millionaire if I could get rid of my conscience.”

A friend of mine in obstetrics said that yesterday. We were talking about the various quackery products pushed over the Internet and in some stores. These things claim to heal anything from Parkinson’s disease to a broken heart, and are generally sold by someone without real medical training. Generally, they also include some comment about this being a cure that doctors are hiding from you.

Of course, all of this is untrue. If there were actually cure for some horrible neurologic disease, I’d be thrilled to prescribe it. I’m here to reduce suffering, not prolong it.

I get it. People want to believe there’s hope when there is none. Even if it’s just something like forgetting a broken relationship, they want to believe there’s a way to make it happen quickly and painlessly.

It would be nice if it worked that way, but it doesn’t. Worse, people in these unfortunate medical or emotional situations are often vulnerable to these sales pitches, and there’s no shortage of unscrupulous individuals willing to prey on them.

What bothers me most in these cases is when doctors, with training similar to mine, push these “remedies.” Often they’re sold in a case in the waiting room and recommended during the visit. I assume these physicians either have lost their conscience and don’t care, or over time have somehow convinced themselves that what they’re doing is right.

Having a doctor selling or endorsing such a product gives it a credibility that it usually won’t get from an average Internet huckster, even if it’s for the same thing.

I’m sure some doctors have convinced themselves that the product is harmless, and therefore falls under primum non nocere. But being harmless isn’t the same as being effective, which is what the patient wants.

Like my friend said, with the financial pressures modern physicians are under, it’s easy to look at things like this as a way to improve cash flow and the bottom line. But you can’t lose sight of the patients. They’re why we are here, and selling them a product that will do them no good isn’t right.

Hippocrates’ “Do no harm” is a key part of being a doctor, but Jiminy Cricket’s “always let your conscience be your guide” is part of being a good doctor. We should never forget that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I’d be a millionaire if I could get rid of my conscience.”

A friend of mine in obstetrics said that yesterday. We were talking about the various quackery products pushed over the Internet and in some stores. These things claim to heal anything from Parkinson’s disease to a broken heart, and are generally sold by someone without real medical training. Generally, they also include some comment about this being a cure that doctors are hiding from you.

Of course, all of this is untrue. If there were actually cure for some horrible neurologic disease, I’d be thrilled to prescribe it. I’m here to reduce suffering, not prolong it.

I get it. People want to believe there’s hope when there is none. Even if it’s just something like forgetting a broken relationship, they want to believe there’s a way to make it happen quickly and painlessly.

It would be nice if it worked that way, but it doesn’t. Worse, people in these unfortunate medical or emotional situations are often vulnerable to these sales pitches, and there’s no shortage of unscrupulous individuals willing to prey on them.

What bothers me most in these cases is when doctors, with training similar to mine, push these “remedies.” Often they’re sold in a case in the waiting room and recommended during the visit. I assume these physicians either have lost their conscience and don’t care, or over time have somehow convinced themselves that what they’re doing is right.

Having a doctor selling or endorsing such a product gives it a credibility that it usually won’t get from an average Internet huckster, even if it’s for the same thing.

I’m sure some doctors have convinced themselves that the product is harmless, and therefore falls under primum non nocere. But being harmless isn’t the same as being effective, which is what the patient wants.

Like my friend said, with the financial pressures modern physicians are under, it’s easy to look at things like this as a way to improve cash flow and the bottom line. But you can’t lose sight of the patients. They’re why we are here, and selling them a product that will do them no good isn’t right.

Hippocrates’ “Do no harm” is a key part of being a doctor, but Jiminy Cricket’s “always let your conscience be your guide” is part of being a good doctor. We should never forget that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Mild aerobic exercise speeds sports concussion recovery

Mild aerobic exercise significantly shortened recovery time from sports-related concussion in adolescent athletes, compared with a stretching program in a randomized trial of 103 participants.

Sports-related concussion (SRC) remains a major public health problem with no effective treatment, wrote John J. Leddy, MD, of the State University of New York at Buffalo, and his colleagues.

Exercise tolerance after SRC has not been well studied. However, given the demonstrated benefits of aerobic exercise training on autonomic nervous system regulation, cerebral blood flow regulation, cardiovascular physiology, and brain neuroplasticity, the researchers hypothesized that exercise at a level that does not exacerbate symptoms might facilitate recovery in concussion patients.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers randomized 103 adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years to a program of subsymptom aerobic exercise or a placebo stretching program. The participants were enrolled in the study within 10 days of an SRC, and were followed for 30 days or until recovery.

Athletes in the aerobic exercise group recovered in a median of 13 days, compared with 17 days for those in the stretching group (P = .009). Recovery was defined as “symptom resolution to normal,” based on normal physical and neurological examinations, “further confirmed by demonstration of the ability to exercise to exhaustion without exacerbation of symptoms” according to the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test, the researchers wrote.

No demographic differences or difference in previous concussions, time from injury until treatment, initial symptom severity score, initial exercise treadmill test, or physical exam were noted between the groups.

The average age of the participants was 15 years, 47% were female. The athletes performed the aerobic exercise or stretching programs approximately 20 minutes per day, and reported their daily symptoms and compliance via a website. The aerobic exercise consisted of walking or jogging on a treadmill or outdoors, or riding a stationary bike while wearing a heart rate monitor to maintain a target heart rate. The target heart rate was calculated as 80% of the heart rate at symptom exacerbation during the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test at each participant’s initial visit.

No adverse events related to the exercise intervention were reported, which supports the safety of subsymptom threshhold exercise, in the study population, Dr. Leddy and his associates noted.

The researchers also found lower rates of persistent symptoms at 1 month in the exercise group, compared with the stretching group (two participants vs. seven participants), but this difference was not statistically significant.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the unblinded design and failure to address the mechanism of action for the effects of exercise. In addition, the results are not generalizable to younger children or other demographic groups, including those with concussions from causes other than sports and adults with heart conditions, the researchers noted.

However, “the results of this study should give clinicians confidence that moderate levels of physical activity, including prescribed subsymptom threshold aerobic exercise, after the first 48 hours following SRC can safely and significantly speed recovery,” Dr. Leddy and his associates concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Leddy JJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4397.

In 2009 and 2010, the culture of sports concussion care began to shift with the publication of an initial study by Leddy et al. on the use of exercise at subsymptom levels as part of concussion rehabilitation, Sara P. D. Chrisman, MD, MPH, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Previous guidelines had emphasized total avoidance of physical activity, as well as avoidance of screen time and social activity, until patients were asymptomatic; however, “no definition was provided for the term asymptomatic, and no time limits were placed on rest, and as a result, rest often continued for weeks or months,” Dr. Chrisman said. Additional research over the past decade supported the potential value of moderate exercise, and the 2016 meeting of the Concussion in Sport Group resulted in recommendations limiting rest to 24-48 hours, which prompted further studies of exercise intervention.

The current study by Leddy et al. is a clinical trial using exercise “to treat acute concussion with a goal of reducing symptom duration,” she said. Despite the study’s limitations, including the inability to estimate how much exercise was needed to achieve the treatment outcome, “this is a landmark study that may shift the standard of care toward the use of rehabilitative exercise to decrease the duration of concussion symptoms.

“Future studies will need to explore the limits of exercise treatment for concussion,” and should address questions including the timing, intensity, and duration of exercise and whether the strategy is appropriate for other populations, such as those with mental health comorbidities, Dr. Chrisman concluded.

Dr. Chrisman is at the Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute. These comments are from her editorial accompanying the article by Leddy et al. (JAMA Pedatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5281). She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

In 2009 and 2010, the culture of sports concussion care began to shift with the publication of an initial study by Leddy et al. on the use of exercise at subsymptom levels as part of concussion rehabilitation, Sara P. D. Chrisman, MD, MPH, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Previous guidelines had emphasized total avoidance of physical activity, as well as avoidance of screen time and social activity, until patients were asymptomatic; however, “no definition was provided for the term asymptomatic, and no time limits were placed on rest, and as a result, rest often continued for weeks or months,” Dr. Chrisman said. Additional research over the past decade supported the potential value of moderate exercise, and the 2016 meeting of the Concussion in Sport Group resulted in recommendations limiting rest to 24-48 hours, which prompted further studies of exercise intervention.

The current study by Leddy et al. is a clinical trial using exercise “to treat acute concussion with a goal of reducing symptom duration,” she said. Despite the study’s limitations, including the inability to estimate how much exercise was needed to achieve the treatment outcome, “this is a landmark study that may shift the standard of care toward the use of rehabilitative exercise to decrease the duration of concussion symptoms.

“Future studies will need to explore the limits of exercise treatment for concussion,” and should address questions including the timing, intensity, and duration of exercise and whether the strategy is appropriate for other populations, such as those with mental health comorbidities, Dr. Chrisman concluded.

Dr. Chrisman is at the Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute. These comments are from her editorial accompanying the article by Leddy et al. (JAMA Pedatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5281). She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

In 2009 and 2010, the culture of sports concussion care began to shift with the publication of an initial study by Leddy et al. on the use of exercise at subsymptom levels as part of concussion rehabilitation, Sara P. D. Chrisman, MD, MPH, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Previous guidelines had emphasized total avoidance of physical activity, as well as avoidance of screen time and social activity, until patients were asymptomatic; however, “no definition was provided for the term asymptomatic, and no time limits were placed on rest, and as a result, rest often continued for weeks or months,” Dr. Chrisman said. Additional research over the past decade supported the potential value of moderate exercise, and the 2016 meeting of the Concussion in Sport Group resulted in recommendations limiting rest to 24-48 hours, which prompted further studies of exercise intervention.

The current study by Leddy et al. is a clinical trial using exercise “to treat acute concussion with a goal of reducing symptom duration,” she said. Despite the study’s limitations, including the inability to estimate how much exercise was needed to achieve the treatment outcome, “this is a landmark study that may shift the standard of care toward the use of rehabilitative exercise to decrease the duration of concussion symptoms.

“Future studies will need to explore the limits of exercise treatment for concussion,” and should address questions including the timing, intensity, and duration of exercise and whether the strategy is appropriate for other populations, such as those with mental health comorbidities, Dr. Chrisman concluded.

Dr. Chrisman is at the Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute. These comments are from her editorial accompanying the article by Leddy et al. (JAMA Pedatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5281). She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Mild aerobic exercise significantly shortened recovery time from sports-related concussion in adolescent athletes, compared with a stretching program in a randomized trial of 103 participants.

Sports-related concussion (SRC) remains a major public health problem with no effective treatment, wrote John J. Leddy, MD, of the State University of New York at Buffalo, and his colleagues.

Exercise tolerance after SRC has not been well studied. However, given the demonstrated benefits of aerobic exercise training on autonomic nervous system regulation, cerebral blood flow regulation, cardiovascular physiology, and brain neuroplasticity, the researchers hypothesized that exercise at a level that does not exacerbate symptoms might facilitate recovery in concussion patients.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers randomized 103 adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years to a program of subsymptom aerobic exercise or a placebo stretching program. The participants were enrolled in the study within 10 days of an SRC, and were followed for 30 days or until recovery.

Athletes in the aerobic exercise group recovered in a median of 13 days, compared with 17 days for those in the stretching group (P = .009). Recovery was defined as “symptom resolution to normal,” based on normal physical and neurological examinations, “further confirmed by demonstration of the ability to exercise to exhaustion without exacerbation of symptoms” according to the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test, the researchers wrote.

No demographic differences or difference in previous concussions, time from injury until treatment, initial symptom severity score, initial exercise treadmill test, or physical exam were noted between the groups.

The average age of the participants was 15 years, 47% were female. The athletes performed the aerobic exercise or stretching programs approximately 20 minutes per day, and reported their daily symptoms and compliance via a website. The aerobic exercise consisted of walking or jogging on a treadmill or outdoors, or riding a stationary bike while wearing a heart rate monitor to maintain a target heart rate. The target heart rate was calculated as 80% of the heart rate at symptom exacerbation during the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test at each participant’s initial visit.

No adverse events related to the exercise intervention were reported, which supports the safety of subsymptom threshhold exercise, in the study population, Dr. Leddy and his associates noted.

The researchers also found lower rates of persistent symptoms at 1 month in the exercise group, compared with the stretching group (two participants vs. seven participants), but this difference was not statistically significant.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the unblinded design and failure to address the mechanism of action for the effects of exercise. In addition, the results are not generalizable to younger children or other demographic groups, including those with concussions from causes other than sports and adults with heart conditions, the researchers noted.

However, “the results of this study should give clinicians confidence that moderate levels of physical activity, including prescribed subsymptom threshold aerobic exercise, after the first 48 hours following SRC can safely and significantly speed recovery,” Dr. Leddy and his associates concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Leddy JJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4397.

Mild aerobic exercise significantly shortened recovery time from sports-related concussion in adolescent athletes, compared with a stretching program in a randomized trial of 103 participants.

Sports-related concussion (SRC) remains a major public health problem with no effective treatment, wrote John J. Leddy, MD, of the State University of New York at Buffalo, and his colleagues.

Exercise tolerance after SRC has not been well studied. However, given the demonstrated benefits of aerobic exercise training on autonomic nervous system regulation, cerebral blood flow regulation, cardiovascular physiology, and brain neuroplasticity, the researchers hypothesized that exercise at a level that does not exacerbate symptoms might facilitate recovery in concussion patients.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers randomized 103 adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years to a program of subsymptom aerobic exercise or a placebo stretching program. The participants were enrolled in the study within 10 days of an SRC, and were followed for 30 days or until recovery.

Athletes in the aerobic exercise group recovered in a median of 13 days, compared with 17 days for those in the stretching group (P = .009). Recovery was defined as “symptom resolution to normal,” based on normal physical and neurological examinations, “further confirmed by demonstration of the ability to exercise to exhaustion without exacerbation of symptoms” according to the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test, the researchers wrote.

No demographic differences or difference in previous concussions, time from injury until treatment, initial symptom severity score, initial exercise treadmill test, or physical exam were noted between the groups.

The average age of the participants was 15 years, 47% were female. The athletes performed the aerobic exercise or stretching programs approximately 20 minutes per day, and reported their daily symptoms and compliance via a website. The aerobic exercise consisted of walking or jogging on a treadmill or outdoors, or riding a stationary bike while wearing a heart rate monitor to maintain a target heart rate. The target heart rate was calculated as 80% of the heart rate at symptom exacerbation during the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test at each participant’s initial visit.

No adverse events related to the exercise intervention were reported, which supports the safety of subsymptom threshhold exercise, in the study population, Dr. Leddy and his associates noted.

The researchers also found lower rates of persistent symptoms at 1 month in the exercise group, compared with the stretching group (two participants vs. seven participants), but this difference was not statistically significant.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the unblinded design and failure to address the mechanism of action for the effects of exercise. In addition, the results are not generalizable to younger children or other demographic groups, including those with concussions from causes other than sports and adults with heart conditions, the researchers noted.

However, “the results of this study should give clinicians confidence that moderate levels of physical activity, including prescribed subsymptom threshold aerobic exercise, after the first 48 hours following SRC can safely and significantly speed recovery,” Dr. Leddy and his associates concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Leddy JJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4397.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Teen athletes who performed aerobic exercise recovered from sports-related concussions in 13 days, compared with 17 days for those in a placebo-stretching group.

Study details: The data come from a randomized trial of 103 athletes aged 13-18 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Leddy JJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4397.

Winners and losers under bold Trump plan to slash drug rebate deals

Few consumers have heard of the secret, business-to-business payments that the Trump administration wants to ban in an attempt to control drug costs.

But the administration’s plan for drug rebates, announced Jan. 31, would end the pharmaceutical business as usual, shift billions in revenue and cause far-reaching, unforeseen change, say health policy authorities.

In pointed language sure to anger middlemen who benefit from the deals, administration officials proposed banning rebates paid by drug companies to ensure coverage for their products under Medicare and Medicaid plans.

“A shadowy system of kickbacks,” was how Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar described the current system in a speech on Feb. 1.

The proposal is a regulatory change applying only to Medicare plans for seniors and managed Medicaid plans for low-income people. But private insurers, who often take cues from government programs, might make a similar shift, administration officials said.

Drug rebates are essentially discounts off the list price. Outlawing them would divert $29 billion in rebates now paid to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers into “seniors’ pocketbooks at the pharmacy counter,” Azar said.

The measure already faces fierce opposition from some in the industry and is unlikely to be implemented as presented or by the proposed 2020 effective date, health policy analysts said.

In any event, it’s hardly a pure win for seniors or patients in general. Consumers are unlikely to collect the full benefit of eliminated rebates.

At the same time, the change would produce uncertain ricochets, including higher drug-plan premiums for consumers, that would produce new winners and losers across the economy.

“It is the most significant proposal that the administration has introduced so far” to try to control drug prices, said Rachel Sachs, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “But I’m struck by the uncertainty that the administration has in what the effects would be.”

Chronically ill patients who take lots of expensive medicine

The list price for many brand-name medicines has doubled or tripled in recent years. But virtually the only ones affected by the full increases are the many patients who pay cash or whose out-of-pocket payments are based on the posted price.

By banning rebates, the administration says its intention is to ensure discounts are passed all the way to the patient instead of the middlemen, the so-called pharmacy benefit managers or PBMs. That means consumers using expensive drugs might see their out-of-pocket costs go down.

If rebates were eliminated for commercial insurance, where deductibles and out-of-pocket costs are generally much higher, chronically ill patients could benefit much more.

Drug companies

Ending rebates would give the administration a drug-policy “win” that doesn’t directly threaten pharmaceutical company profits.

“We applaud the administration for taking steps to reform the rebate system” Stephen Ubl, CEO of PhRMA, the main lobby for branded drugs, said after the proposal came out.

The change might also slow the soaring list-price increases that have become a publicity nightmare for the industry. When list prices pop by 5% or 10% each year, drugmakers pay part of the proceeds to insurers and PBMs in the form of rebates to guarantee health-plan coverage.

No one is claiming that eliminating rebates would stop escalating list prices, even if all insurers adopted the practice. But some believe it would remove an important factor.

Pharmacy benefit managers

PBMs reap billions of dollars in rebate revenue in return for putting particular products on lists of covered drugs. The administration is essentially proposing to make those payments illegal, at least for Medicare and Medicaid plans.

PBMs, which claim they control costs by negotiating with drugmakers, might have to go back to their roots – processing pharmacy claims for a fee. After recent industry consolidation into a few enormous companies, on the other hand, they might have the market power to charge very high fees, replacing much of the lost rebate revenue.

PBMs “are concerned” that the move “would increase drug costs and force Medicare beneficiaries to pay higher premiums and out-of-pocket expenses,” said JC Scott, CEO of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the PBM lobby.

Insurance companies

Insurers, who often receive rebates directly, could also be hurt financially.

“From the start, the focus on rebates has been a distraction from the real issue – the problem is the price” of the drugs, said Matt Eyles, CEO of America’s Health Insurance Plans, a trade group. “We are not middlemen – we are your bargaining power, working hard to negotiate lower prices.”

Patients without chronic conditions and high drug costs

Lower out-of-pocket costs at the pharmacy counter would be financed, at least in part, by higher premiums for Medicare and Medicaid plans paid by consumers and the government. Premiums for Medicare Part D plans could rise from $3.20 to $5.64 per month, according to consultants hired by the Department of Health and Human Services.

“There is likely to be a wide variation in how much savings people see based on the drugs they take and the point-of-sale discounts that are negotiated,” said Elizabeth Carpenter, policy practice director at Avalere, a consultancy.

Consumers who don’t need expensive drugs every month could see insurance costs go up slightly without getting the benefits of lower out-of-pocket expense for purchased drugs.

Other policy changes giving health plans more negotiating power against drugmakers would keep a lid on premium increases, administration officials argue.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Few consumers have heard of the secret, business-to-business payments that the Trump administration wants to ban in an attempt to control drug costs.

But the administration’s plan for drug rebates, announced Jan. 31, would end the pharmaceutical business as usual, shift billions in revenue and cause far-reaching, unforeseen change, say health policy authorities.

In pointed language sure to anger middlemen who benefit from the deals, administration officials proposed banning rebates paid by drug companies to ensure coverage for their products under Medicare and Medicaid plans.

“A shadowy system of kickbacks,” was how Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar described the current system in a speech on Feb. 1.

The proposal is a regulatory change applying only to Medicare plans for seniors and managed Medicaid plans for low-income people. But private insurers, who often take cues from government programs, might make a similar shift, administration officials said.

Drug rebates are essentially discounts off the list price. Outlawing them would divert $29 billion in rebates now paid to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers into “seniors’ pocketbooks at the pharmacy counter,” Azar said.

The measure already faces fierce opposition from some in the industry and is unlikely to be implemented as presented or by the proposed 2020 effective date, health policy analysts said.

In any event, it’s hardly a pure win for seniors or patients in general. Consumers are unlikely to collect the full benefit of eliminated rebates.

At the same time, the change would produce uncertain ricochets, including higher drug-plan premiums for consumers, that would produce new winners and losers across the economy.

“It is the most significant proposal that the administration has introduced so far” to try to control drug prices, said Rachel Sachs, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “But I’m struck by the uncertainty that the administration has in what the effects would be.”

Chronically ill patients who take lots of expensive medicine

The list price for many brand-name medicines has doubled or tripled in recent years. But virtually the only ones affected by the full increases are the many patients who pay cash or whose out-of-pocket payments are based on the posted price.

By banning rebates, the administration says its intention is to ensure discounts are passed all the way to the patient instead of the middlemen, the so-called pharmacy benefit managers or PBMs. That means consumers using expensive drugs might see their out-of-pocket costs go down.

If rebates were eliminated for commercial insurance, where deductibles and out-of-pocket costs are generally much higher, chronically ill patients could benefit much more.

Drug companies

Ending rebates would give the administration a drug-policy “win” that doesn’t directly threaten pharmaceutical company profits.

“We applaud the administration for taking steps to reform the rebate system” Stephen Ubl, CEO of PhRMA, the main lobby for branded drugs, said after the proposal came out.

The change might also slow the soaring list-price increases that have become a publicity nightmare for the industry. When list prices pop by 5% or 10% each year, drugmakers pay part of the proceeds to insurers and PBMs in the form of rebates to guarantee health-plan coverage.

No one is claiming that eliminating rebates would stop escalating list prices, even if all insurers adopted the practice. But some believe it would remove an important factor.

Pharmacy benefit managers

PBMs reap billions of dollars in rebate revenue in return for putting particular products on lists of covered drugs. The administration is essentially proposing to make those payments illegal, at least for Medicare and Medicaid plans.

PBMs, which claim they control costs by negotiating with drugmakers, might have to go back to their roots – processing pharmacy claims for a fee. After recent industry consolidation into a few enormous companies, on the other hand, they might have the market power to charge very high fees, replacing much of the lost rebate revenue.

PBMs “are concerned” that the move “would increase drug costs and force Medicare beneficiaries to pay higher premiums and out-of-pocket expenses,” said JC Scott, CEO of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the PBM lobby.

Insurance companies

Insurers, who often receive rebates directly, could also be hurt financially.

“From the start, the focus on rebates has been a distraction from the real issue – the problem is the price” of the drugs, said Matt Eyles, CEO of America’s Health Insurance Plans, a trade group. “We are not middlemen – we are your bargaining power, working hard to negotiate lower prices.”

Patients without chronic conditions and high drug costs

Lower out-of-pocket costs at the pharmacy counter would be financed, at least in part, by higher premiums for Medicare and Medicaid plans paid by consumers and the government. Premiums for Medicare Part D plans could rise from $3.20 to $5.64 per month, according to consultants hired by the Department of Health and Human Services.

“There is likely to be a wide variation in how much savings people see based on the drugs they take and the point-of-sale discounts that are negotiated,” said Elizabeth Carpenter, policy practice director at Avalere, a consultancy.

Consumers who don’t need expensive drugs every month could see insurance costs go up slightly without getting the benefits of lower out-of-pocket expense for purchased drugs.

Other policy changes giving health plans more negotiating power against drugmakers would keep a lid on premium increases, administration officials argue.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Few consumers have heard of the secret, business-to-business payments that the Trump administration wants to ban in an attempt to control drug costs.

But the administration’s plan for drug rebates, announced Jan. 31, would end the pharmaceutical business as usual, shift billions in revenue and cause far-reaching, unforeseen change, say health policy authorities.

In pointed language sure to anger middlemen who benefit from the deals, administration officials proposed banning rebates paid by drug companies to ensure coverage for their products under Medicare and Medicaid plans.

“A shadowy system of kickbacks,” was how Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar described the current system in a speech on Feb. 1.

The proposal is a regulatory change applying only to Medicare plans for seniors and managed Medicaid plans for low-income people. But private insurers, who often take cues from government programs, might make a similar shift, administration officials said.

Drug rebates are essentially discounts off the list price. Outlawing them would divert $29 billion in rebates now paid to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers into “seniors’ pocketbooks at the pharmacy counter,” Azar said.

The measure already faces fierce opposition from some in the industry and is unlikely to be implemented as presented or by the proposed 2020 effective date, health policy analysts said.

In any event, it’s hardly a pure win for seniors or patients in general. Consumers are unlikely to collect the full benefit of eliminated rebates.

At the same time, the change would produce uncertain ricochets, including higher drug-plan premiums for consumers, that would produce new winners and losers across the economy.

“It is the most significant proposal that the administration has introduced so far” to try to control drug prices, said Rachel Sachs, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “But I’m struck by the uncertainty that the administration has in what the effects would be.”

Chronically ill patients who take lots of expensive medicine

The list price for many brand-name medicines has doubled or tripled in recent years. But virtually the only ones affected by the full increases are the many patients who pay cash or whose out-of-pocket payments are based on the posted price.

By banning rebates, the administration says its intention is to ensure discounts are passed all the way to the patient instead of the middlemen, the so-called pharmacy benefit managers or PBMs. That means consumers using expensive drugs might see their out-of-pocket costs go down.

If rebates were eliminated for commercial insurance, where deductibles and out-of-pocket costs are generally much higher, chronically ill patients could benefit much more.

Drug companies

Ending rebates would give the administration a drug-policy “win” that doesn’t directly threaten pharmaceutical company profits.

“We applaud the administration for taking steps to reform the rebate system” Stephen Ubl, CEO of PhRMA, the main lobby for branded drugs, said after the proposal came out.

The change might also slow the soaring list-price increases that have become a publicity nightmare for the industry. When list prices pop by 5% or 10% each year, drugmakers pay part of the proceeds to insurers and PBMs in the form of rebates to guarantee health-plan coverage.

No one is claiming that eliminating rebates would stop escalating list prices, even if all insurers adopted the practice. But some believe it would remove an important factor.

Pharmacy benefit managers

PBMs reap billions of dollars in rebate revenue in return for putting particular products on lists of covered drugs. The administration is essentially proposing to make those payments illegal, at least for Medicare and Medicaid plans.

PBMs, which claim they control costs by negotiating with drugmakers, might have to go back to their roots – processing pharmacy claims for a fee. After recent industry consolidation into a few enormous companies, on the other hand, they might have the market power to charge very high fees, replacing much of the lost rebate revenue.

PBMs “are concerned” that the move “would increase drug costs and force Medicare beneficiaries to pay higher premiums and out-of-pocket expenses,” said JC Scott, CEO of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the PBM lobby.

Insurance companies

Insurers, who often receive rebates directly, could also be hurt financially.

“From the start, the focus on rebates has been a distraction from the real issue – the problem is the price” of the drugs, said Matt Eyles, CEO of America’s Health Insurance Plans, a trade group. “We are not middlemen – we are your bargaining power, working hard to negotiate lower prices.”

Patients without chronic conditions and high drug costs

Lower out-of-pocket costs at the pharmacy counter would be financed, at least in part, by higher premiums for Medicare and Medicaid plans paid by consumers and the government. Premiums for Medicare Part D plans could rise from $3.20 to $5.64 per month, according to consultants hired by the Department of Health and Human Services.

“There is likely to be a wide variation in how much savings people see based on the drugs they take and the point-of-sale discounts that are negotiated,” said Elizabeth Carpenter, policy practice director at Avalere, a consultancy.

Consumers who don’t need expensive drugs every month could see insurance costs go up slightly without getting the benefits of lower out-of-pocket expense for purchased drugs.

Other policy changes giving health plans more negotiating power against drugmakers would keep a lid on premium increases, administration officials argue.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Aerobic exercise and cognitive decline

Also today, findings in seropositive arthralgia patients may help to predict rheumatoid arthritis, elevated coronary artery calcification is not linked to increased death risk in active men, and clinical benefits persist 5 years after theymectomy for myasthenia gravis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, findings in seropositive arthralgia patients may help to predict rheumatoid arthritis, elevated coronary artery calcification is not linked to increased death risk in active men, and clinical benefits persist 5 years after theymectomy for myasthenia gravis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, findings in seropositive arthralgia patients may help to predict rheumatoid arthritis, elevated coronary artery calcification is not linked to increased death risk in active men, and clinical benefits persist 5 years after theymectomy for myasthenia gravis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

CMS proposing more flexibility in Medicare Advantage, Part D

More flexibility in benefits design could be coming to Medicare Advantage and the Part D prescription drug benefit if proposals offered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

The agency issued its proposed update for both programs for the 2020 plan year, which would allow Medicare Advantage plan sponsors to offer more specialized supplemental benefits for beneficiaries with chronic illnesses.

“For the 2020 plan year and beyond, Medicare Advantage plans will have greater flexibility to offer chronically ill patients any benefit that improves or maintains their health,” Demetrios Kouzoukas, CMS principal deputy administrator for Medicare and director of the Center for Medicare, said during a Jan. 30 press teleconference. “For example, plans could provide home-delivered or special meals in a far broader set of circumstances than what is allowed today.”

He noted that it would be up to the plans to determine what kinds of supplemental benefits would be offered and added that the offering of these benefits would not require a waiver, but would be evaluated as part of the plan’s overall bid submitted to the agency.

“We recognize that Medicare beneficiaries frequently have multiple chronic conditions,” Mr. Kouzoukas said. “We are excited that these changes will allow these beneficiaries to have new options for improving their health as a result of innovative health plan benefits.”

For Medicare Part D, the agency is specifically encouraging plan sponsors “to provide lower cost sharing for opioid reversal agents such as naloxone,” he added. The proposal also offers additional flexibility for plans to offer targeted benefits and cost sharing reductions to patients with chronic pain or those undergoing addiction treatment, according to a fact sheet highlighting key proposals.

Comments on the proposals are due by March 1. CMS expects to finalize the changes by the beginning of April.

More flexibility in benefits design could be coming to Medicare Advantage and the Part D prescription drug benefit if proposals offered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

The agency issued its proposed update for both programs for the 2020 plan year, which would allow Medicare Advantage plan sponsors to offer more specialized supplemental benefits for beneficiaries with chronic illnesses.

“For the 2020 plan year and beyond, Medicare Advantage plans will have greater flexibility to offer chronically ill patients any benefit that improves or maintains their health,” Demetrios Kouzoukas, CMS principal deputy administrator for Medicare and director of the Center for Medicare, said during a Jan. 30 press teleconference. “For example, plans could provide home-delivered or special meals in a far broader set of circumstances than what is allowed today.”

He noted that it would be up to the plans to determine what kinds of supplemental benefits would be offered and added that the offering of these benefits would not require a waiver, but would be evaluated as part of the plan’s overall bid submitted to the agency.

“We recognize that Medicare beneficiaries frequently have multiple chronic conditions,” Mr. Kouzoukas said. “We are excited that these changes will allow these beneficiaries to have new options for improving their health as a result of innovative health plan benefits.”

For Medicare Part D, the agency is specifically encouraging plan sponsors “to provide lower cost sharing for opioid reversal agents such as naloxone,” he added. The proposal also offers additional flexibility for plans to offer targeted benefits and cost sharing reductions to patients with chronic pain or those undergoing addiction treatment, according to a fact sheet highlighting key proposals.

Comments on the proposals are due by March 1. CMS expects to finalize the changes by the beginning of April.

More flexibility in benefits design could be coming to Medicare Advantage and the Part D prescription drug benefit if proposals offered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

The agency issued its proposed update for both programs for the 2020 plan year, which would allow Medicare Advantage plan sponsors to offer more specialized supplemental benefits for beneficiaries with chronic illnesses.

“For the 2020 plan year and beyond, Medicare Advantage plans will have greater flexibility to offer chronically ill patients any benefit that improves or maintains their health,” Demetrios Kouzoukas, CMS principal deputy administrator for Medicare and director of the Center for Medicare, said during a Jan. 30 press teleconference. “For example, plans could provide home-delivered or special meals in a far broader set of circumstances than what is allowed today.”

He noted that it would be up to the plans to determine what kinds of supplemental benefits would be offered and added that the offering of these benefits would not require a waiver, but would be evaluated as part of the plan’s overall bid submitted to the agency.

“We recognize that Medicare beneficiaries frequently have multiple chronic conditions,” Mr. Kouzoukas said. “We are excited that these changes will allow these beneficiaries to have new options for improving their health as a result of innovative health plan benefits.”

For Medicare Part D, the agency is specifically encouraging plan sponsors “to provide lower cost sharing for opioid reversal agents such as naloxone,” he added. The proposal also offers additional flexibility for plans to offer targeted benefits and cost sharing reductions to patients with chronic pain or those undergoing addiction treatment, according to a fact sheet highlighting key proposals.

Comments on the proposals are due by March 1. CMS expects to finalize the changes by the beginning of April.

Shifting drugs from Part B to Part D could be costly to patients

A shift in Medicare drug coverage from Part B to Part D might save the government some money but could end up costing some patients in the long run.

Analysis of the 75 brand-name drugs with the highest Part B expenditures ($21.6 billion annually at 2018 prices) indicated that the government could save between $17.6 billion and $20.1 billion after rebates by switching coverage to Part D, Thomas J. Hwang of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates said.

The potential for greater overall savings, however, “was constrained by the fact that 33 (44%) of the studied brand-name drugs were in protected classes, which HHS has reported precludes meaningful price negotiation by Part D plans,” they wrote.

The proposal also could have a “material impact” on patient out-of-pocket costs, although the impact would vary based on the drug as well as patients’ insurance coverage in addition to Medicare (JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417).

For example, moving drug coverage to Part D would lower out-of-pocket costs for the majority of the 75 drugs for patients with Medigap supplemental insurance, but out-of-pocket costs could go up for almost 40% of products. Patients who would benefit most from the shift would be those who qualify for the low-income subsidy, which can eliminate coinsurance requirements.

“By contrast, for patients with Medigap insurance, out-of-pocket costs in Part D were estimated to exceed the annual premium costs for supplemental insurance [approximately 47-56 of the 75 drugs],” Mr. Hwang and his colleagues added. “Out-of-pocket costs would be increased under the proposed policy for beneficiaries with Medigap but without Part D coverage.”

The analysis was limited by the inability to predict the proposed transition’s impact on insurance premiums or drug utilization. Patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid were excluded.

SOURCE: Hwang TJ et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417.

Policy analysts need to be careful and do their due diligence to ensure all consequences of the policy options are fully understood, especially as pharmaceuticals account for greater costs in the Medicare program. Future policy analyses must, like Mr. Hwang and his associates did, account for changes to Medicare costs as well as beneficiary costs to understand the overall effects of policy changes.

Francis Crosson, MD, chairman of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, and Jon Christianson, PhD, vice chairman of MedPAC, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6146 ).

Policy analysts need to be careful and do their due diligence to ensure all consequences of the policy options are fully understood, especially as pharmaceuticals account for greater costs in the Medicare program. Future policy analyses must, like Mr. Hwang and his associates did, account for changes to Medicare costs as well as beneficiary costs to understand the overall effects of policy changes.

Francis Crosson, MD, chairman of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, and Jon Christianson, PhD, vice chairman of MedPAC, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6146 ).

Policy analysts need to be careful and do their due diligence to ensure all consequences of the policy options are fully understood, especially as pharmaceuticals account for greater costs in the Medicare program. Future policy analyses must, like Mr. Hwang and his associates did, account for changes to Medicare costs as well as beneficiary costs to understand the overall effects of policy changes.

Francis Crosson, MD, chairman of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, and Jon Christianson, PhD, vice chairman of MedPAC, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6146 ).

A shift in Medicare drug coverage from Part B to Part D might save the government some money but could end up costing some patients in the long run.

Analysis of the 75 brand-name drugs with the highest Part B expenditures ($21.6 billion annually at 2018 prices) indicated that the government could save between $17.6 billion and $20.1 billion after rebates by switching coverage to Part D, Thomas J. Hwang of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates said.

The potential for greater overall savings, however, “was constrained by the fact that 33 (44%) of the studied brand-name drugs were in protected classes, which HHS has reported precludes meaningful price negotiation by Part D plans,” they wrote.

The proposal also could have a “material impact” on patient out-of-pocket costs, although the impact would vary based on the drug as well as patients’ insurance coverage in addition to Medicare (JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417).

For example, moving drug coverage to Part D would lower out-of-pocket costs for the majority of the 75 drugs for patients with Medigap supplemental insurance, but out-of-pocket costs could go up for almost 40% of products. Patients who would benefit most from the shift would be those who qualify for the low-income subsidy, which can eliminate coinsurance requirements.

“By contrast, for patients with Medigap insurance, out-of-pocket costs in Part D were estimated to exceed the annual premium costs for supplemental insurance [approximately 47-56 of the 75 drugs],” Mr. Hwang and his colleagues added. “Out-of-pocket costs would be increased under the proposed policy for beneficiaries with Medigap but without Part D coverage.”

The analysis was limited by the inability to predict the proposed transition’s impact on insurance premiums or drug utilization. Patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid were excluded.

SOURCE: Hwang TJ et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417.

A shift in Medicare drug coverage from Part B to Part D might save the government some money but could end up costing some patients in the long run.

Analysis of the 75 brand-name drugs with the highest Part B expenditures ($21.6 billion annually at 2018 prices) indicated that the government could save between $17.6 billion and $20.1 billion after rebates by switching coverage to Part D, Thomas J. Hwang of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates said.

The potential for greater overall savings, however, “was constrained by the fact that 33 (44%) of the studied brand-name drugs were in protected classes, which HHS has reported precludes meaningful price negotiation by Part D plans,” they wrote.

The proposal also could have a “material impact” on patient out-of-pocket costs, although the impact would vary based on the drug as well as patients’ insurance coverage in addition to Medicare (JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417).

For example, moving drug coverage to Part D would lower out-of-pocket costs for the majority of the 75 drugs for patients with Medigap supplemental insurance, but out-of-pocket costs could go up for almost 40% of products. Patients who would benefit most from the shift would be those who qualify for the low-income subsidy, which can eliminate coinsurance requirements.

“By contrast, for patients with Medigap insurance, out-of-pocket costs in Part D were estimated to exceed the annual premium costs for supplemental insurance [approximately 47-56 of the 75 drugs],” Mr. Hwang and his colleagues added. “Out-of-pocket costs would be increased under the proposed policy for beneficiaries with Medigap but without Part D coverage.”

The analysis was limited by the inability to predict the proposed transition’s impact on insurance premiums or drug utilization. Patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid were excluded.

SOURCE: Hwang TJ et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Shifting drug coverage to Part D would save the government money.

Major finding: For patients with Medigap plans, costs could increase on as many as 40% of the drugs studied.

Study details: Researchers examined the 75 drugs with the highest Part B expenditures in 2016 and, using 2018 prices, estimated the effect of moving these drugs into the Part D prescription drug program.

Disclosures: No relevant conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Hwang TJ et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417.

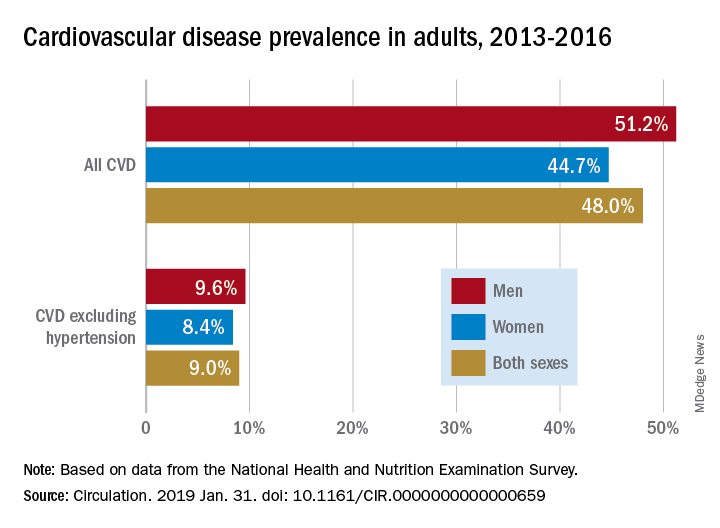

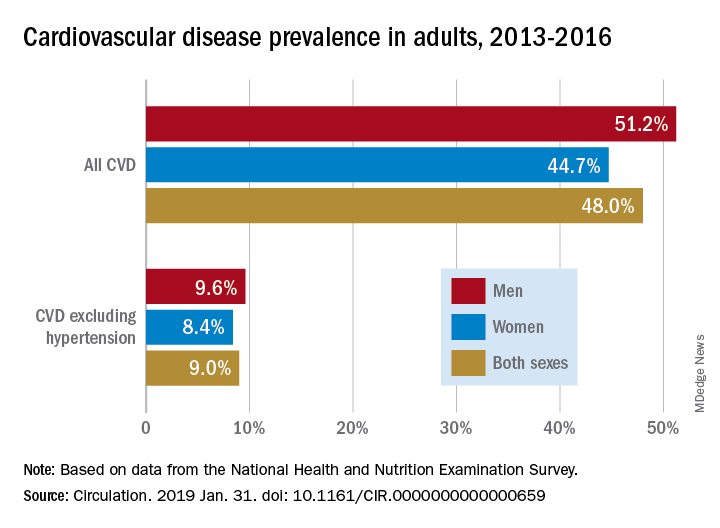

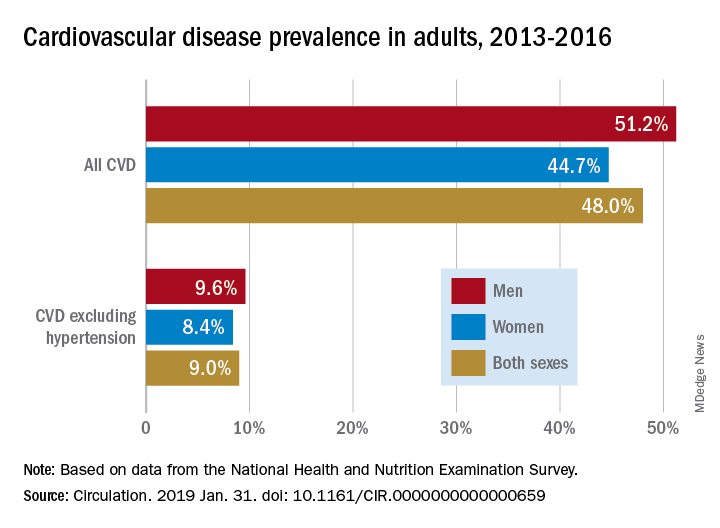

AHA report highlights CVD burden, declines in smoking, sleep importance

Almost half of U.S. adults now have some form of cardiovascular disease, according to the latest annual statistical update from the American Heart Association.