User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatology application costs increased from 2021 to 2024, largely due to expenses related to away rotations and, in some cases, a return to in-person interviews.

- Away rotations play a critical role in the dermatology match; however, they also contribute substantially to financial burden.

- The cost-saving impact of virtual interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights a meaningful opportunity for future cost reduction.

- Further interventions are needed to meaningfully reduce financial burden and promote equity.

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Pediatric alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the hair follicles characterized by nonscarring hair loss. Its incidence in children in the United States ranges from 13.6 to 33.5 per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 0.04% to 0.11%.1 Alopecia areata has important effects on quality of life, particularly in children. Hair loss at an early age can decrease participation in school, sports, and extracurricular activities2 and is associated with increased rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.3 Families also experience psychosocial stress, often comparable to other chronic pediatric illnesses.4 Thus, management requires not only medical therapy but also psychosocial support and school-based accommodations.

Systemic therapies for treatment of AA in adolescents and adults are increasingly available, including US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as baricitinib, deuruxolitinib (for adults), and ritlecitinib (for adolescents and adults); however, no systemic therapies have been approved by the FDA for children younger than 12 years. The therapeutic gap is most acute for those aged 6 to 11 years, for whom the psychosocial burden is high but treatment options are limited.3

This article highlights options and strategies for managing AA in children aged 6 to 11 years, emphasizing supportive and psychosocial care (including camouflage techniques), topical therapies, and off-label systemic approaches.

Supportive and Psychosocial Care

Treatment of AA in children extends beyond the affected child to include parents, caregivers, and even school staff (eg, teachers, principals, nurses).4 Disease-specific organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (naaf.org) and the Children’s Alopecia Project (childrensalopeciaproject.org) provide education, support groups, and advocacy resources. These organizations assist families in navigating school accommodations, including Section 504 plans that may allow children with AA to wear hats in school to mitigate stigma. Additional resources include handouts for teachers and school nurses developed by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.5

Psychological support for these patients is critical. Many children benefit from seeing a psychologist, particularly if anxiety, depression, and/or bullying is present.3 In clinics without embedded psychology services, dermatologists should maintain referral lists or encourage families to seek guidance from their pediatrician.

Camouflage techniques can help children cope with visible hair loss. Wigs and hairpieces are available free of charge through charitable organizations for patients younger than 17; however, young children often find adhesives uncomfortable, and they will not wear nonadherent wigs for long periods of time. Alternatives include soft hats, bonnets, scarves, and beanies. For partial hair loss, root concealers, scalp powders, or hair mascara can be useful. Temporary eyebrow tattoos are a good cosmetic approach, whereas microblading generally is not advised in children younger than 12 due to procedural risks including pain.

Topical Therapies

Topical agents remain the mainstay of treatment for AA in children aged 6 to 11 years. Potent class 1 or class 2 topical corticosteroids commonly are used, sometimes in combination with calcineurin inhibitors or topical minoxidil. Off-label compounded topical JAK inhibitors also have been tried in this population and may be helpful for eyebrow hair loss,6 though data on their efficacy for scalp AA are mixed.7 Intralesional corticosteroid injections, effective in adolescents and adults, generally are poorly tolerated by younger children and may cause considerable distress. Contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or anthralin can be considered, but these agents are designed to elicit irritation, which may be intolerable for young children.8 Shared decision-making with families is essential to balance efficacy, tolerability, and treatment burden.

Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapy generally is reserved for children with extensive or refractory AA. Low-dose oral minoxidil is emerging as an off-label option. One systematic review reported that low-dose oral minoxidil was well tolerated in pediatric patients with minimal adverse effects.9 Doses of 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg/d are reasonable starting points, achieved by cutting tablets or compounding oral solutions.10

In children with AA and concurrent atopic dermatitis, dupilumab may offer dual benefit. A real-world observational study demonstrated hair regrowth in pediatric patients with AA treated with dupilumab.11 Immunosuppressive options such as low-dose methotrexate or pulse corticosteroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone) also may be considered, although use of these agents requires careful monitoring due to increased risk for infection, clinically significant blood count and liver enzyme changes, and metabolic adverse effects related to long-term use of corticosteroids.

Clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in children aged 6 to 11 years are anticipated to begin in late 2025. Until then, off-label use of ritlecitinib, baricitinib, tofacitinib, or other JAK inhibitors may be considered in select cases with considerable disease burden and quality-of-life impairment following thorough discussion with the patient and their caregivers. Currently available pediatric data show few serious adverse events in children—the most common included upper respiratory infections (nasopharyngitis), acne, and headaches—but long-term risks remain unknown. Dosing challenges also exist for children who cannot swallow pills; currently ritlecitinib is available only as a capsule that cannot be opened while other JAK inhibitors are available in more accessible forms (baricitinib can be crushed and dissolved, and tofacitinib is available in liquid formulation for other pediatric indications). Insurance coverage is a major barrier, as these therapies are not FDA approved for AA in this age group.

Final Thoughts

Alopecia areata in children aged 6 to 11 years presents unique therapeutic challenges. While highly effective systemic therapies exist for older patients, younger children have limited options. For the 6-to-11 age group, management strategies should prioritize psychosocial support, topical therapy, and low-burden systemic alternatives such as low-dose oral minoxidil. Family education, school-based accommodations, and access to camouflage techniques are integral to holistic care. The commencement of pediatric clinical trials for JAK inhibitors offers hope for more robust treatment strategies in the near future. In the meantime, clinicians must engage in shared decision-making, tailoring therapy to the child’s disease severity, emotional well-being, and family priorities.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42(suppl 1):12-23. doi:10.1111/pde.15803

- Paller AS, Rangel SM, Chamlin SL, et al; Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Stigmatization and mental health impact of chronic pediatric skin disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:621-630.

- van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1054898.

- Yücesoy SN, Uzunçakmak TK, Selçukog?lu Ö, et al. Evaluation of quality of life scores and family impact scales in pediatric patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2024;63:1414-1420.

- Alopecia areata. Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://pedsderm.net/site/assets/files/18580/spd_school_handout_1_alopecia.pdf

- Liu LY, King BA. Response to tofacitinib therapy of eyebrows and eyelashes in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1778-1779.

- Bokhari L, Sinclair R. Treatment of alopecia universalis with topical Janus kinase inhibitors—a double blind, placebo, and active controlled pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1464-1470.

- Hill ND, Bunata K, Hebert AA. Treatment of alopecia areata with squaric acid dibutylester. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:300-304.

- Williams KN, Olukoga CTY, Tosti A. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of oral minoxidil in children: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1709-1727.

- Lemes LR, Melo DF, de Oliveira DS, et al. Topical and oral minoxidil for hair disorders in pediatric patients: what do we know so far? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13950.

- David E, Shokrian N, Del Duca E, et al. Dupilumab induces hair regrowth in pediatric alopecia areata: a real-world, single-center observational study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:487.

Pediatric alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the hair follicles characterized by nonscarring hair loss. Its incidence in children in the United States ranges from 13.6 to 33.5 per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 0.04% to 0.11%.1 Alopecia areata has important effects on quality of life, particularly in children. Hair loss at an early age can decrease participation in school, sports, and extracurricular activities2 and is associated with increased rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.3 Families also experience psychosocial stress, often comparable to other chronic pediatric illnesses.4 Thus, management requires not only medical therapy but also psychosocial support and school-based accommodations.

Systemic therapies for treatment of AA in adolescents and adults are increasingly available, including US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as baricitinib, deuruxolitinib (for adults), and ritlecitinib (for adolescents and adults); however, no systemic therapies have been approved by the FDA for children younger than 12 years. The therapeutic gap is most acute for those aged 6 to 11 years, for whom the psychosocial burden is high but treatment options are limited.3

This article highlights options and strategies for managing AA in children aged 6 to 11 years, emphasizing supportive and psychosocial care (including camouflage techniques), topical therapies, and off-label systemic approaches.

Supportive and Psychosocial Care

Treatment of AA in children extends beyond the affected child to include parents, caregivers, and even school staff (eg, teachers, principals, nurses).4 Disease-specific organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (naaf.org) and the Children’s Alopecia Project (childrensalopeciaproject.org) provide education, support groups, and advocacy resources. These organizations assist families in navigating school accommodations, including Section 504 plans that may allow children with AA to wear hats in school to mitigate stigma. Additional resources include handouts for teachers and school nurses developed by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.5

Psychological support for these patients is critical. Many children benefit from seeing a psychologist, particularly if anxiety, depression, and/or bullying is present.3 In clinics without embedded psychology services, dermatologists should maintain referral lists or encourage families to seek guidance from their pediatrician.

Camouflage techniques can help children cope with visible hair loss. Wigs and hairpieces are available free of charge through charitable organizations for patients younger than 17; however, young children often find adhesives uncomfortable, and they will not wear nonadherent wigs for long periods of time. Alternatives include soft hats, bonnets, scarves, and beanies. For partial hair loss, root concealers, scalp powders, or hair mascara can be useful. Temporary eyebrow tattoos are a good cosmetic approach, whereas microblading generally is not advised in children younger than 12 due to procedural risks including pain.

Topical Therapies

Topical agents remain the mainstay of treatment for AA in children aged 6 to 11 years. Potent class 1 or class 2 topical corticosteroids commonly are used, sometimes in combination with calcineurin inhibitors or topical minoxidil. Off-label compounded topical JAK inhibitors also have been tried in this population and may be helpful for eyebrow hair loss,6 though data on their efficacy for scalp AA are mixed.7 Intralesional corticosteroid injections, effective in adolescents and adults, generally are poorly tolerated by younger children and may cause considerable distress. Contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or anthralin can be considered, but these agents are designed to elicit irritation, which may be intolerable for young children.8 Shared decision-making with families is essential to balance efficacy, tolerability, and treatment burden.

Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapy generally is reserved for children with extensive or refractory AA. Low-dose oral minoxidil is emerging as an off-label option. One systematic review reported that low-dose oral minoxidil was well tolerated in pediatric patients with minimal adverse effects.9 Doses of 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg/d are reasonable starting points, achieved by cutting tablets or compounding oral solutions.10

In children with AA and concurrent atopic dermatitis, dupilumab may offer dual benefit. A real-world observational study demonstrated hair regrowth in pediatric patients with AA treated with dupilumab.11 Immunosuppressive options such as low-dose methotrexate or pulse corticosteroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone) also may be considered, although use of these agents requires careful monitoring due to increased risk for infection, clinically significant blood count and liver enzyme changes, and metabolic adverse effects related to long-term use of corticosteroids.

Clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in children aged 6 to 11 years are anticipated to begin in late 2025. Until then, off-label use of ritlecitinib, baricitinib, tofacitinib, or other JAK inhibitors may be considered in select cases with considerable disease burden and quality-of-life impairment following thorough discussion with the patient and their caregivers. Currently available pediatric data show few serious adverse events in children—the most common included upper respiratory infections (nasopharyngitis), acne, and headaches—but long-term risks remain unknown. Dosing challenges also exist for children who cannot swallow pills; currently ritlecitinib is available only as a capsule that cannot be opened while other JAK inhibitors are available in more accessible forms (baricitinib can be crushed and dissolved, and tofacitinib is available in liquid formulation for other pediatric indications). Insurance coverage is a major barrier, as these therapies are not FDA approved for AA in this age group.

Final Thoughts

Alopecia areata in children aged 6 to 11 years presents unique therapeutic challenges. While highly effective systemic therapies exist for older patients, younger children have limited options. For the 6-to-11 age group, management strategies should prioritize psychosocial support, topical therapy, and low-burden systemic alternatives such as low-dose oral minoxidil. Family education, school-based accommodations, and access to camouflage techniques are integral to holistic care. The commencement of pediatric clinical trials for JAK inhibitors offers hope for more robust treatment strategies in the near future. In the meantime, clinicians must engage in shared decision-making, tailoring therapy to the child’s disease severity, emotional well-being, and family priorities.

Pediatric alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the hair follicles characterized by nonscarring hair loss. Its incidence in children in the United States ranges from 13.6 to 33.5 per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 0.04% to 0.11%.1 Alopecia areata has important effects on quality of life, particularly in children. Hair loss at an early age can decrease participation in school, sports, and extracurricular activities2 and is associated with increased rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.3 Families also experience psychosocial stress, often comparable to other chronic pediatric illnesses.4 Thus, management requires not only medical therapy but also psychosocial support and school-based accommodations.

Systemic therapies for treatment of AA in adolescents and adults are increasingly available, including US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as baricitinib, deuruxolitinib (for adults), and ritlecitinib (for adolescents and adults); however, no systemic therapies have been approved by the FDA for children younger than 12 years. The therapeutic gap is most acute for those aged 6 to 11 years, for whom the psychosocial burden is high but treatment options are limited.3

This article highlights options and strategies for managing AA in children aged 6 to 11 years, emphasizing supportive and psychosocial care (including camouflage techniques), topical therapies, and off-label systemic approaches.

Supportive and Psychosocial Care

Treatment of AA in children extends beyond the affected child to include parents, caregivers, and even school staff (eg, teachers, principals, nurses).4 Disease-specific organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (naaf.org) and the Children’s Alopecia Project (childrensalopeciaproject.org) provide education, support groups, and advocacy resources. These organizations assist families in navigating school accommodations, including Section 504 plans that may allow children with AA to wear hats in school to mitigate stigma. Additional resources include handouts for teachers and school nurses developed by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.5

Psychological support for these patients is critical. Many children benefit from seeing a psychologist, particularly if anxiety, depression, and/or bullying is present.3 In clinics without embedded psychology services, dermatologists should maintain referral lists or encourage families to seek guidance from their pediatrician.

Camouflage techniques can help children cope with visible hair loss. Wigs and hairpieces are available free of charge through charitable organizations for patients younger than 17; however, young children often find adhesives uncomfortable, and they will not wear nonadherent wigs for long periods of time. Alternatives include soft hats, bonnets, scarves, and beanies. For partial hair loss, root concealers, scalp powders, or hair mascara can be useful. Temporary eyebrow tattoos are a good cosmetic approach, whereas microblading generally is not advised in children younger than 12 due to procedural risks including pain.

Topical Therapies

Topical agents remain the mainstay of treatment for AA in children aged 6 to 11 years. Potent class 1 or class 2 topical corticosteroids commonly are used, sometimes in combination with calcineurin inhibitors or topical minoxidil. Off-label compounded topical JAK inhibitors also have been tried in this population and may be helpful for eyebrow hair loss,6 though data on their efficacy for scalp AA are mixed.7 Intralesional corticosteroid injections, effective in adolescents and adults, generally are poorly tolerated by younger children and may cause considerable distress. Contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or anthralin can be considered, but these agents are designed to elicit irritation, which may be intolerable for young children.8 Shared decision-making with families is essential to balance efficacy, tolerability, and treatment burden.

Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapy generally is reserved for children with extensive or refractory AA. Low-dose oral minoxidil is emerging as an off-label option. One systematic review reported that low-dose oral minoxidil was well tolerated in pediatric patients with minimal adverse effects.9 Doses of 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg/d are reasonable starting points, achieved by cutting tablets or compounding oral solutions.10

In children with AA and concurrent atopic dermatitis, dupilumab may offer dual benefit. A real-world observational study demonstrated hair regrowth in pediatric patients with AA treated with dupilumab.11 Immunosuppressive options such as low-dose methotrexate or pulse corticosteroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone) also may be considered, although use of these agents requires careful monitoring due to increased risk for infection, clinically significant blood count and liver enzyme changes, and metabolic adverse effects related to long-term use of corticosteroids.

Clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in children aged 6 to 11 years are anticipated to begin in late 2025. Until then, off-label use of ritlecitinib, baricitinib, tofacitinib, or other JAK inhibitors may be considered in select cases with considerable disease burden and quality-of-life impairment following thorough discussion with the patient and their caregivers. Currently available pediatric data show few serious adverse events in children—the most common included upper respiratory infections (nasopharyngitis), acne, and headaches—but long-term risks remain unknown. Dosing challenges also exist for children who cannot swallow pills; currently ritlecitinib is available only as a capsule that cannot be opened while other JAK inhibitors are available in more accessible forms (baricitinib can be crushed and dissolved, and tofacitinib is available in liquid formulation for other pediatric indications). Insurance coverage is a major barrier, as these therapies are not FDA approved for AA in this age group.

Final Thoughts

Alopecia areata in children aged 6 to 11 years presents unique therapeutic challenges. While highly effective systemic therapies exist for older patients, younger children have limited options. For the 6-to-11 age group, management strategies should prioritize psychosocial support, topical therapy, and low-burden systemic alternatives such as low-dose oral minoxidil. Family education, school-based accommodations, and access to camouflage techniques are integral to holistic care. The commencement of pediatric clinical trials for JAK inhibitors offers hope for more robust treatment strategies in the near future. In the meantime, clinicians must engage in shared decision-making, tailoring therapy to the child’s disease severity, emotional well-being, and family priorities.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42(suppl 1):12-23. doi:10.1111/pde.15803

- Paller AS, Rangel SM, Chamlin SL, et al; Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Stigmatization and mental health impact of chronic pediatric skin disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:621-630.

- van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1054898.

- Yücesoy SN, Uzunçakmak TK, Selçukog?lu Ö, et al. Evaluation of quality of life scores and family impact scales in pediatric patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2024;63:1414-1420.

- Alopecia areata. Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://pedsderm.net/site/assets/files/18580/spd_school_handout_1_alopecia.pdf

- Liu LY, King BA. Response to tofacitinib therapy of eyebrows and eyelashes in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1778-1779.

- Bokhari L, Sinclair R. Treatment of alopecia universalis with topical Janus kinase inhibitors—a double blind, placebo, and active controlled pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1464-1470.

- Hill ND, Bunata K, Hebert AA. Treatment of alopecia areata with squaric acid dibutylester. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:300-304.

- Williams KN, Olukoga CTY, Tosti A. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of oral minoxidil in children: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1709-1727.

- Lemes LR, Melo DF, de Oliveira DS, et al. Topical and oral minoxidil for hair disorders in pediatric patients: what do we know so far? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13950.

- David E, Shokrian N, Del Duca E, et al. Dupilumab induces hair regrowth in pediatric alopecia areata: a real-world, single-center observational study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:487.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42(suppl 1):12-23. doi:10.1111/pde.15803

- Paller AS, Rangel SM, Chamlin SL, et al; Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Stigmatization and mental health impact of chronic pediatric skin disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:621-630.

- van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1054898.

- Yücesoy SN, Uzunçakmak TK, Selçukog?lu Ö, et al. Evaluation of quality of life scores and family impact scales in pediatric patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2024;63:1414-1420.

- Alopecia areata. Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://pedsderm.net/site/assets/files/18580/spd_school_handout_1_alopecia.pdf

- Liu LY, King BA. Response to tofacitinib therapy of eyebrows and eyelashes in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1778-1779.

- Bokhari L, Sinclair R. Treatment of alopecia universalis with topical Janus kinase inhibitors—a double blind, placebo, and active controlled pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1464-1470.

- Hill ND, Bunata K, Hebert AA. Treatment of alopecia areata with squaric acid dibutylester. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:300-304.

- Williams KN, Olukoga CTY, Tosti A. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of oral minoxidil in children: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1709-1727.

- Lemes LR, Melo DF, de Oliveira DS, et al. Topical and oral minoxidil for hair disorders in pediatric patients: what do we know so far? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13950.

- David E, Shokrian N, Del Duca E, et al. Dupilumab induces hair regrowth in pediatric alopecia areata: a real-world, single-center observational study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:487.

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Solitary Yellow Papule on the Upper Back in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

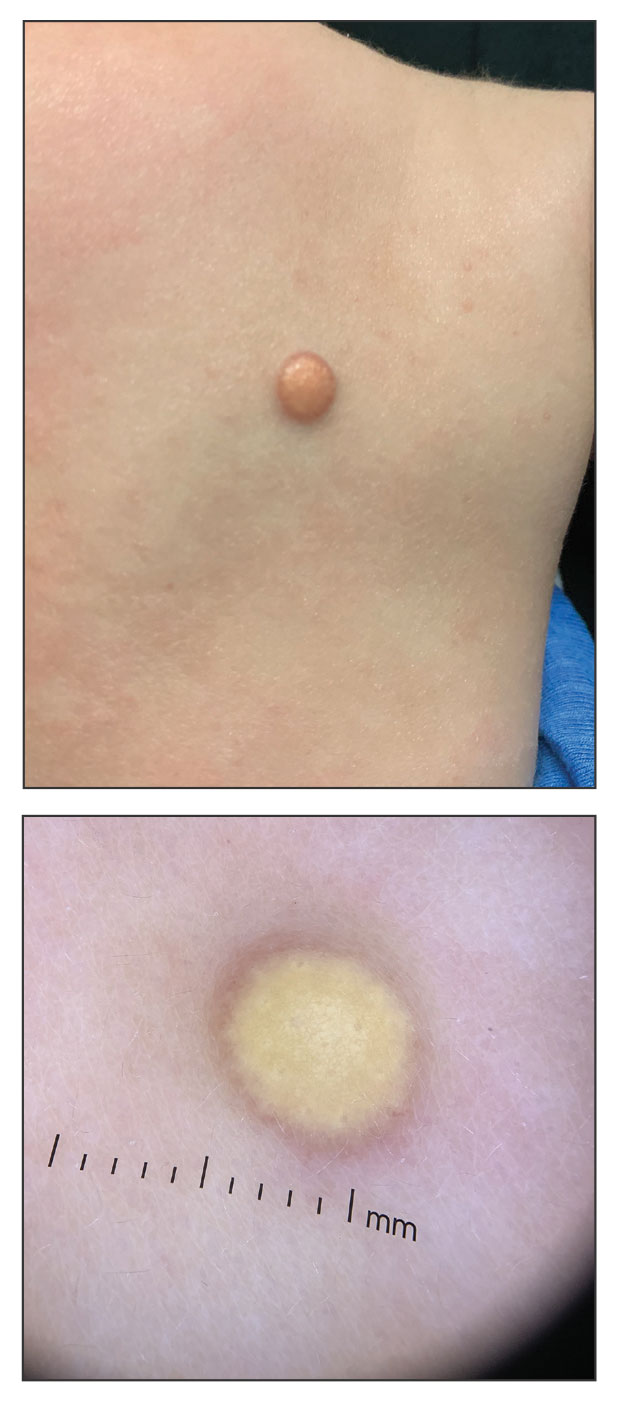

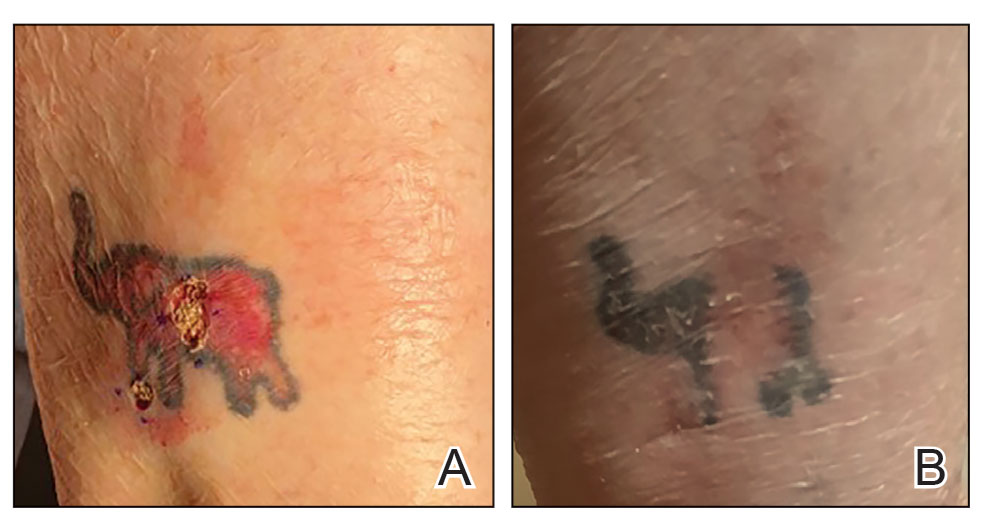

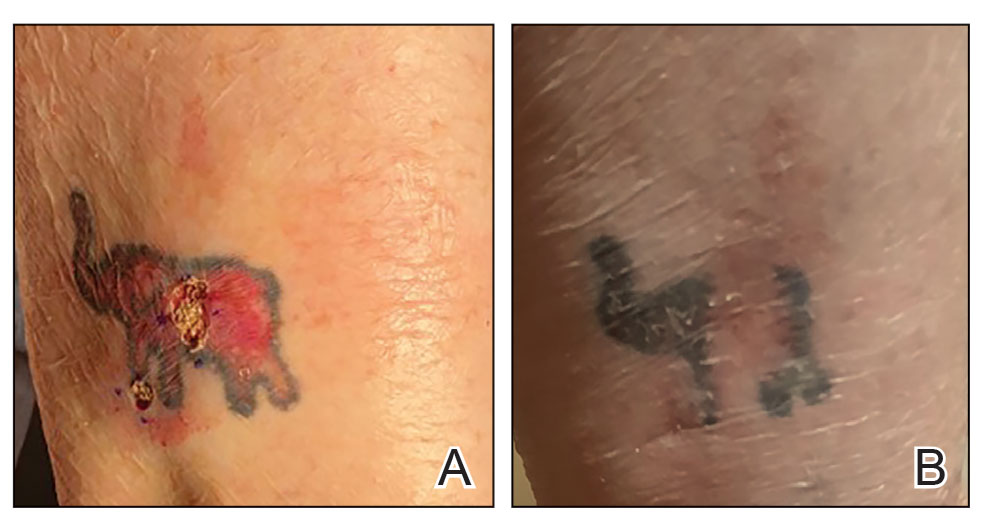

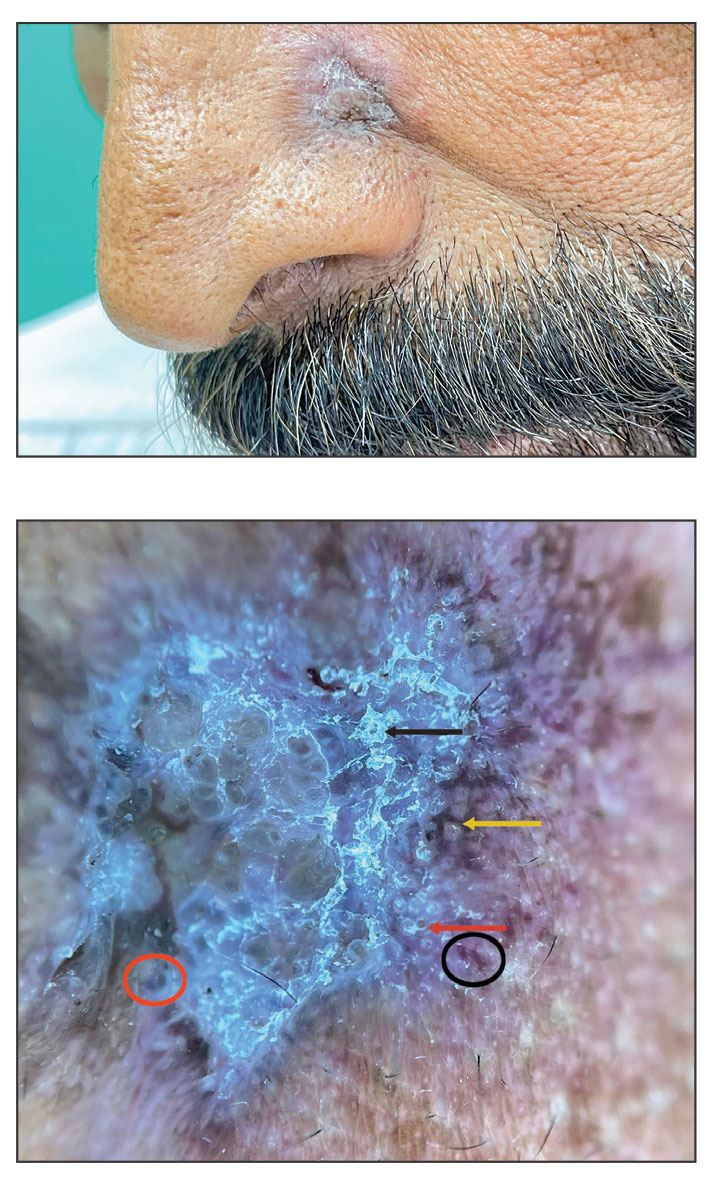

Given the patient’s age, clinical features of the lesion, and characteristic setting-sun pattern on dermoscopy, a diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was made. The patient showed no other signs of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or systemic disease and was managed conservatively with observation and routine follow-up. Minimal growth of the lesion was noted at 1-year follow-up, and he was meeting all age-appropriate developmental milestones and showed no other symptoms consistent with NF1.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is the most common childhood non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis. While it typically manifests as an isolated condition, JXG also can be associated with NF1 as well as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.1-3 Neurofibromatosis type 1 is a multisystem disorder with variable clinical manifestations that commonly is associated with skin findings such as café au lait macules, intertriginous freckling, and neurofibromas, in addition to JXG.2,3 Diagnosis of JXG should prompt noninvasive evaluation for further signs and symptoms of NF1, including thorough patient and family history and physical examination to identify other characteristic cutaneous findings, and can include consideration of slit lamp eye examination and radiography for identification of osseous findings.

The pathogenesis of JXG is not fully known, though there is evidence that it may be associated with a mutation in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.1 The majority of cases appear in the first year of life.4 Clinically, JXG can manifest with extracutaneous lesions, including on the eyes and lungs.5-7 Juvenile xanthogranuloma can be noninvasively diagnosed with dermoscopy. As seen in our patient, dermoscopic findings include a red-yellow or yellow-orange background with an erythematous border, typically described as a setting-sun pattern.4,8 Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis; however, given the usually benign course, this often is unnecessary. Most pediatric patients with cutaneous manifestations have a self-limited course with regression over several months to years. Generally, no treatment is required for cutaneous manifestations alone; however, lesions can be removed for aesthetic concerns. For those with systemic involvement, a range of other treatments have been used, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, systemic corticosteroids, and cyclosporine.6,7

The differential diagnosis for JXG includes Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, Fabry disease, solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, and tuberous sclerosis complex. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is an autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the growth of adnexal neoplasms, including trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. These lesions usually manifest on the face but can include other areas such as the trunk.9 Fabry disease is an X-linked recessive lysosomal storage disorder with cutaneous manifestations such as angiokeratoma corporis diffusum and hypohidrosis. Patients also may present with systemic symptoms including hypertension and renal and cardiovascular disease.10 Mastocytosis encompasses several clinical disorders defined by mast cell hyperplasia and accumulation in various organ systems, and solitary cutaneous mastocytoma is the most common manifestation in children.11,12 Cutaneous mastocytoma can manifest as a single red-brown or yellow papule, usually located on the arms or legs.13 Solitary cutaneous mastocytomas in pediatric patients typically are diagnosed based on clinical appearance and the formation of a wheal upon firm palpation (Darier sign).11-13 Our patient did not demonstrate the Darier sign, and the lesion was asymptomatic. Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder with neurologic and skin findings that occur early in the disease course and include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, and café-au-lait macules.14

- Durham BH, Lopez Rodrigo E, Picarsic J, et al. Activating mutations in CSF1R and additional receptor tyrosine kinases in histiocytic neoplasms. Nat Med. 2019;25:1839-1842.

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1998.

- Miraglia E, Laghi A, Moramarco A, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in neurofibromatosis type 1. Prevalence and possible correlation with lymphoproliferative diseases: experience of a single center and review of the literature. Clin Ther. 2022;173:353-355.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Newman B, Hu W, Nigro K, et al. Aggressive histiocytic disorders that can involve the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:302-316.

- Freyer DR, Kennedy R, Bostrom BC, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: forms of systemic disease and their clinical implications. J Pediatr. 1996;129:227-237.

- Murphy JT, Soeken T, Megison S, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: diverse presentations of noncutaneous disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.2014;36:641-645.

- Xu J, Ma L. Dermoscopic patterns in juvenile xanthogranuloma based on the histological classification. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;7:618946.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bokhari SRA, Zulfiqar H, Hariz A. Fabry disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Update July 4, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435996/

- Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

- Klaiber N, Kumar S, Irani AM. Mastocytosis in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17:80.

- Sławin´ ska M, Kaszuba A, Lange M, et al. Dermoscopic features of different forms of cutaneous mastocytosis: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4649.

- Teng JM, Cowen EW, Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. Dermatologic and dental aspects of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Statements. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1095-1101.

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Given the patient’s age, clinical features of the lesion, and characteristic setting-sun pattern on dermoscopy, a diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was made. The patient showed no other signs of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or systemic disease and was managed conservatively with observation and routine follow-up. Minimal growth of the lesion was noted at 1-year follow-up, and he was meeting all age-appropriate developmental milestones and showed no other symptoms consistent with NF1.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is the most common childhood non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis. While it typically manifests as an isolated condition, JXG also can be associated with NF1 as well as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.1-3 Neurofibromatosis type 1 is a multisystem disorder with variable clinical manifestations that commonly is associated with skin findings such as café au lait macules, intertriginous freckling, and neurofibromas, in addition to JXG.2,3 Diagnosis of JXG should prompt noninvasive evaluation for further signs and symptoms of NF1, including thorough patient and family history and physical examination to identify other characteristic cutaneous findings, and can include consideration of slit lamp eye examination and radiography for identification of osseous findings.

The pathogenesis of JXG is not fully known, though there is evidence that it may be associated with a mutation in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.1 The majority of cases appear in the first year of life.4 Clinically, JXG can manifest with extracutaneous lesions, including on the eyes and lungs.5-7 Juvenile xanthogranuloma can be noninvasively diagnosed with dermoscopy. As seen in our patient, dermoscopic findings include a red-yellow or yellow-orange background with an erythematous border, typically described as a setting-sun pattern.4,8 Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis; however, given the usually benign course, this often is unnecessary. Most pediatric patients with cutaneous manifestations have a self-limited course with regression over several months to years. Generally, no treatment is required for cutaneous manifestations alone; however, lesions can be removed for aesthetic concerns. For those with systemic involvement, a range of other treatments have been used, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, systemic corticosteroids, and cyclosporine.6,7

The differential diagnosis for JXG includes Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, Fabry disease, solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, and tuberous sclerosis complex. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is an autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the growth of adnexal neoplasms, including trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. These lesions usually manifest on the face but can include other areas such as the trunk.9 Fabry disease is an X-linked recessive lysosomal storage disorder with cutaneous manifestations such as angiokeratoma corporis diffusum and hypohidrosis. Patients also may present with systemic symptoms including hypertension and renal and cardiovascular disease.10 Mastocytosis encompasses several clinical disorders defined by mast cell hyperplasia and accumulation in various organ systems, and solitary cutaneous mastocytoma is the most common manifestation in children.11,12 Cutaneous mastocytoma can manifest as a single red-brown or yellow papule, usually located on the arms or legs.13 Solitary cutaneous mastocytomas in pediatric patients typically are diagnosed based on clinical appearance and the formation of a wheal upon firm palpation (Darier sign).11-13 Our patient did not demonstrate the Darier sign, and the lesion was asymptomatic. Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder with neurologic and skin findings that occur early in the disease course and include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, and café-au-lait macules.14

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Given the patient’s age, clinical features of the lesion, and characteristic setting-sun pattern on dermoscopy, a diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was made. The patient showed no other signs of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or systemic disease and was managed conservatively with observation and routine follow-up. Minimal growth of the lesion was noted at 1-year follow-up, and he was meeting all age-appropriate developmental milestones and showed no other symptoms consistent with NF1.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is the most common childhood non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis. While it typically manifests as an isolated condition, JXG also can be associated with NF1 as well as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.1-3 Neurofibromatosis type 1 is a multisystem disorder with variable clinical manifestations that commonly is associated with skin findings such as café au lait macules, intertriginous freckling, and neurofibromas, in addition to JXG.2,3 Diagnosis of JXG should prompt noninvasive evaluation for further signs and symptoms of NF1, including thorough patient and family history and physical examination to identify other characteristic cutaneous findings, and can include consideration of slit lamp eye examination and radiography for identification of osseous findings.

The pathogenesis of JXG is not fully known, though there is evidence that it may be associated with a mutation in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.1 The majority of cases appear in the first year of life.4 Clinically, JXG can manifest with extracutaneous lesions, including on the eyes and lungs.5-7 Juvenile xanthogranuloma can be noninvasively diagnosed with dermoscopy. As seen in our patient, dermoscopic findings include a red-yellow or yellow-orange background with an erythematous border, typically described as a setting-sun pattern.4,8 Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis; however, given the usually benign course, this often is unnecessary. Most pediatric patients with cutaneous manifestations have a self-limited course with regression over several months to years. Generally, no treatment is required for cutaneous manifestations alone; however, lesions can be removed for aesthetic concerns. For those with systemic involvement, a range of other treatments have been used, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, systemic corticosteroids, and cyclosporine.6,7

The differential diagnosis for JXG includes Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, Fabry disease, solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, and tuberous sclerosis complex. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is an autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the growth of adnexal neoplasms, including trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. These lesions usually manifest on the face but can include other areas such as the trunk.9 Fabry disease is an X-linked recessive lysosomal storage disorder with cutaneous manifestations such as angiokeratoma corporis diffusum and hypohidrosis. Patients also may present with systemic symptoms including hypertension and renal and cardiovascular disease.10 Mastocytosis encompasses several clinical disorders defined by mast cell hyperplasia and accumulation in various organ systems, and solitary cutaneous mastocytoma is the most common manifestation in children.11,12 Cutaneous mastocytoma can manifest as a single red-brown or yellow papule, usually located on the arms or legs.13 Solitary cutaneous mastocytomas in pediatric patients typically are diagnosed based on clinical appearance and the formation of a wheal upon firm palpation (Darier sign).11-13 Our patient did not demonstrate the Darier sign, and the lesion was asymptomatic. Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder with neurologic and skin findings that occur early in the disease course and include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, and café-au-lait macules.14

- Durham BH, Lopez Rodrigo E, Picarsic J, et al. Activating mutations in CSF1R and additional receptor tyrosine kinases in histiocytic neoplasms. Nat Med. 2019;25:1839-1842.

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1998.

- Miraglia E, Laghi A, Moramarco A, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in neurofibromatosis type 1. Prevalence and possible correlation with lymphoproliferative diseases: experience of a single center and review of the literature. Clin Ther. 2022;173:353-355.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Newman B, Hu W, Nigro K, et al. Aggressive histiocytic disorders that can involve the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:302-316.

- Freyer DR, Kennedy R, Bostrom BC, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: forms of systemic disease and their clinical implications. J Pediatr. 1996;129:227-237.

- Murphy JT, Soeken T, Megison S, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: diverse presentations of noncutaneous disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.2014;36:641-645.

- Xu J, Ma L. Dermoscopic patterns in juvenile xanthogranuloma based on the histological classification. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;7:618946.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bokhari SRA, Zulfiqar H, Hariz A. Fabry disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Update July 4, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435996/

- Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

- Klaiber N, Kumar S, Irani AM. Mastocytosis in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17:80.

- Sławin´ ska M, Kaszuba A, Lange M, et al. Dermoscopic features of different forms of cutaneous mastocytosis: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4649.

- Teng JM, Cowen EW, Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. Dermatologic and dental aspects of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Statements. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1095-1101.

- Durham BH, Lopez Rodrigo E, Picarsic J, et al. Activating mutations in CSF1R and additional receptor tyrosine kinases in histiocytic neoplasms. Nat Med. 2019;25:1839-1842.

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1998.

- Miraglia E, Laghi A, Moramarco A, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in neurofibromatosis type 1. Prevalence and possible correlation with lymphoproliferative diseases: experience of a single center and review of the literature. Clin Ther. 2022;173:353-355.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Newman B, Hu W, Nigro K, et al. Aggressive histiocytic disorders that can involve the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:302-316.

- Freyer DR, Kennedy R, Bostrom BC, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: forms of systemic disease and their clinical implications. J Pediatr. 1996;129:227-237.

- Murphy JT, Soeken T, Megison S, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: diverse presentations of noncutaneous disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.2014;36:641-645.

- Xu J, Ma L. Dermoscopic patterns in juvenile xanthogranuloma based on the histological classification. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;7:618946.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bokhari SRA, Zulfiqar H, Hariz A. Fabry disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Update July 4, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435996/

- Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

- Klaiber N, Kumar S, Irani AM. Mastocytosis in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17:80.

- Sławin´ ska M, Kaszuba A, Lange M, et al. Dermoscopic features of different forms of cutaneous mastocytosis: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4649.

- Teng JM, Cowen EW, Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. Dermatologic and dental aspects of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Statements. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1095-1101.

A 6-month-old male infant with a history of cradle cap and an infantile hemangioma on the left shoulder presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a slow-growing yellow papule on the upper back of 3 months’ duration. The lesion initially was noted 2 months prior to the current presentation by the patient’s pediatrician, who recommended follow-up with dermatology after an unsuccessful attempt at incision and drainage. Physical examination revealed a 7-mm, yellow, dome-shaped papule with a red collarette on the right upper back. No axillary freckling, ocular findings, or other skin findings were found. The patient was born at term with no complications, and his mother reported that he was otherwise healthy. There were no developmental concerns or known allergies, and his family history was negative for any similar lesions. Dermoscopic examination of the lesion revealed a well-circumscribed, circular, yellow-orange papule with an erythematous border and setting-sun appearance.

Reticulated Hyperpigmentation on the Knee and Thigh

Reticulated Hyperpigmentation on the Knee and Thigh

The patient was diagnosed with erythema ab igne based on characteristic skin findings on physical examination along with a convincing history of chronic localized heat exposure. Erythema ab igne manifests as a persistent reticulated, erythematous, or hyperpigmented rash at sites of chronic heat exposure.1 Commonplace items that emit heat such as electric heaters, car heaters, heating pads, hot water bottles, and, in our case, laptops also emit infrared radiation, which can lead to changes in the skin with long-term exposure.2 Because exposure to these sources often is limited to one area of the body, erythema ab igne usually manifests locally, as exemplified in this case. Chronic heat exposure and infrared radiation from these sources are thought to induce hyperthermia below the threshold for a thermal burn, and the cutaneous findings correspond with the dermal venous plexus.3

Diagnosis of erythema ab igne primarily is made clinically based on characteristic skin findings and exposure history. Relevant history may include occupations with prolonged heat exposure, such as baking, silversmithing, or foundry work. Heat exposure also may result from cultural practices such as cupping with moxibustion.4 Additionally, repeated use of heating pads or hot water bottles for pain relief by patients diagnosed with chronic pain or an underlying illness may contribute to development of erythema ab igne.1,4

Biopsy was not needed for diagnosis of this patient, but if the presentation is equivocal and history of potential exposures is unclear, a biopsy may be taken. A hematoxylin and eosin stain would reveal dilation of small vascular channels in the superficial dermis, contributing to the classic reticulated appearance. Biopsy findings also would reveal either an interface dermatitis or pigment incontinence containing melanin-laden macrophages correlating to either the erythema or hyperpigmentation, respectively.4

The prognosis for erythema ab igne is excellent, especially if diagnosed early. Treatment involves removal of the inciting heat source.1 The discoloration may resolve within a few months to years or may persist. If the hyperpigmentation is persistent, patients may consider laser treatments or lightening agents such as topical hydroquinone or topical tretinoin.4 However, if undiagnosed, patients may be at risk for development of a cutaneous malignancy, such as squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,4 Malignant transformation has been reported to occur decades after the initial skin eruption, although the risk is rare5; however, due to this risk, patients with erythema ab igne should be followed regularly and screened for new lesions in the affected areas.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

- Kesty K, Feldman SR. Erythema ab igne: evolving technology, evolving presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030.

- Harview CL, Krenitsky A. Erythema ab igne: a clinical review. Cutis. 2023;111:E33-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0771

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018