User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Botanical Briefs: Primula obconica Dermatitis

Etiology

Calcareous soils of central and southwest China are home to Primula obconica1 (also known as German primrose and Libre Magenta).2 Primula obconica was introduced to Europe in the 1880s, where it became a popular ornamental and decorative household plant (Figure).3 It also is a frequent resident of greenhouses.

Primula obconica is a member of the family Primulaceae, which comprises semi-evergreen perennials. The genus name Primula is derived from Latin meaning “first”; obconica refers to the conelike shape of the plant’s vivid, cerise-red flowers.

Allergens From P obconica

The allergens primin (2-methoxy-6-pentyl-1,4-benzoquinone) and miconidin (2-methoxy-6-pentyl-1, 4-dihydroxybenzene) have been isolated from P obconica stems, leaves, and flowers. Allergies to P obconica are much more commonly detected in Europe than in the United States because the plant is part of standard allergen screening in dermatology clinics in Europe.4 In a British patch test study of 234 patients with hand dermatitis, 34 displayed immediate or delayed sensitization to P obconica allergens.5 However, in another study, researchers who surveyed the incidence of P obconica allergic contact dermatitis (CD) in the United Kingdom found a notable decline in the number of primin-positive patch tests from 1995 to 2000, which likely was attributable to a decrease in the number of plant retailers who stocked P obconica and the availability of primin-free varieties from 50% of suppliers.3 Furthermore, a study in the United States of 567 consecutive patch tests that included primin as part of standard screening found only 1 positive reaction, suggesting that routine patch testing for P obconica in the United States would have a low yield unless the patient has a relevant history.4

Cutaneous Presentation

Clinical features of P obconica–induced dermatitis include fingertip dermatitis, as well as facial, hand, and forearm dermatitis.6 Patients typically present with lichenification and fissuring of the fingertips; fingertip vesicular dermatitis; or linear erythematous streaks, vesicles, and bullae on the forearms, hands, and face. Vesicles and bullae can be hemorrhagic in patients with pompholyxlike lesions.7

Some patients have been reported to present with facial angioedema; the clinical diagnosis of CD can be challenging when facial edema is more prominent than eczema.6 Furthermore, in a reported case of P obconica CD, the patient’s vesicular hand dermatitis became pustular and spread to the face.8

Allergy Testing

Patch testing is performed with synthetic primin to detect allergens of P obconica in patients who are sensitive to them, which can be useful because Primula dermatitis can have variable presentations and cases can be missed if patch testing is not performed.9 Diagnostic mimics—herpes simplex, pompholyx, seborrheic dermatitis, and scabies—should be considered before patch testing.7

Prevention and Treatment

Preventive Measures—Ideally, once CD occurs in response to P obconica, handling of and other exposure to the plant should be halted; thus, prevention becomes the mainstay of treatment. Alternatively, when exposure is a necessary occupational hazard, nitrile gloves should be worn; allergenicity can be decreased by overwatering or introducing more primin-free varieties.3,10

Cultivating the plant outdoors during the winter in milder climates can potentially decrease sensitivity because allergen production is lowest during cold months and highest during summer.11 Because P obconica is commonly grown indoors, allergenicity can persist year-round.

Pharmacotherapy—Drawing on experience treating CD caused by other plants, acute and chronic P obconica CD are primarily treated with a topical steroid or, if the face or genitals are affected, with a steroid-sparing agent, such as tacrolimus.12 A cool compress of water, saline, or Burow solution (aluminum acetate in water) can help decrease acute inflammation, especially in the setting of vesiculation.13

Mild CD also can be treated with a barrier cream and lipid-rich moisturizer. Their effectiveness likely is due to increased hydration and aiding impaired skin-barrier repair.14

Some success in treating chronic CD also has been reported with psoralen plus UVA and UVB light therapy, which function as local immunosuppressants, thus decreasing inflammation.15

Final Thoughts

Contact dermatitis caused by P obconica is common in Europe but less common in the United States and therefore often is underrecognized. Avoiding contact with the plant should be strongly recommended to allergic persons. Primula obconica allergic CD can be treated with a topical steroid.

- Nan P, Shi S, Peng S, et al. Genetic diversity in Primula obconica (Primulaceae) from Central and South‐west China as revealed by ISSR markers. Ann Bot. 2003;91:329-333. doi:10.1093/AOB/MCG018

- Primula obconica “Libre Magenta” (Ob). The Royal Horticultural Society. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/131697/i-primula-obconica-i-libre-magenta-(ob)/details

- Connolly M, McCune J, Dauncey E, et al. Primula obconica—is contact allergy on the decline? Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:167-171. doi:10.1111/J.0105-1873.2004.00427.X

- Mowad C. Routine testing for Primula obconica: is it useful in the United States? Am J Contact Dermat. 1998;9:231-233.

- Agrup C, Fregert S, Rorsman H. Sensitization by routine patch testing with ether extract of Primula obconica. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:897-898. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1969.TB15970.X

- Lleonart Bellfill R, Casas Ramisa R, Nevot Falcó S. Primula dermatitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 1999;27:29-31.

- Thomson KF, Charles-Holmes R, Beck MH. Primula dermatitis mimicking herpes simplex. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:185-186. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0536.1997.TB00200.X

- Tabar AI, Quirce S, García BE, et al. Primula dermatitis: versatility in its clinical presentation and the advantages of patch tests with synthetic primin. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;30:47-48. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0536.1994.tb00734.X

- Apted JH. Primula obconica sensitivity and testing with primin. Australas J Dermatol. 1988;29:161-162. doi:10.1111/J.1440-0960.1988.TB00390.X

- Aplin CG, Lovell CR. Contact dermatitis due to hardy Primula species and their cultivars. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:23-29. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2001.440105.X

- Christensen LP, Larsen E. Direct emission of the allergen primin from intact Primula obconica plants. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:149-153. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2000.042003149.X

- Esser PR, Mueller S, Martin SF. Plant allergen-induced contact dermatitis. Planta Med. 2019;85:528-534. doi:10.1055/A-0873-1494

- Levin CY, Maibach HI. Do cool water or physiologic saline compresses enhance resolution of experimentally-induced irritant contact dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:146-150. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2001.045003146.X

- M, Lindberg M. The influence of a single application of different moisturizers on the skin capacitance. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:79-82.

- Levin CY, Maibach HI. Irritant contact dermatitis: is there an immunologic component? Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:183-189. doi:10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00171-0

Etiology

Calcareous soils of central and southwest China are home to Primula obconica1 (also known as German primrose and Libre Magenta).2 Primula obconica was introduced to Europe in the 1880s, where it became a popular ornamental and decorative household plant (Figure).3 It also is a frequent resident of greenhouses.

Primula obconica is a member of the family Primulaceae, which comprises semi-evergreen perennials. The genus name Primula is derived from Latin meaning “first”; obconica refers to the conelike shape of the plant’s vivid, cerise-red flowers.

Allergens From P obconica

The allergens primin (2-methoxy-6-pentyl-1,4-benzoquinone) and miconidin (2-methoxy-6-pentyl-1, 4-dihydroxybenzene) have been isolated from P obconica stems, leaves, and flowers. Allergies to P obconica are much more commonly detected in Europe than in the United States because the plant is part of standard allergen screening in dermatology clinics in Europe.4 In a British patch test study of 234 patients with hand dermatitis, 34 displayed immediate or delayed sensitization to P obconica allergens.5 However, in another study, researchers who surveyed the incidence of P obconica allergic contact dermatitis (CD) in the United Kingdom found a notable decline in the number of primin-positive patch tests from 1995 to 2000, which likely was attributable to a decrease in the number of plant retailers who stocked P obconica and the availability of primin-free varieties from 50% of suppliers.3 Furthermore, a study in the United States of 567 consecutive patch tests that included primin as part of standard screening found only 1 positive reaction, suggesting that routine patch testing for P obconica in the United States would have a low yield unless the patient has a relevant history.4

Cutaneous Presentation

Clinical features of P obconica–induced dermatitis include fingertip dermatitis, as well as facial, hand, and forearm dermatitis.6 Patients typically present with lichenification and fissuring of the fingertips; fingertip vesicular dermatitis; or linear erythematous streaks, vesicles, and bullae on the forearms, hands, and face. Vesicles and bullae can be hemorrhagic in patients with pompholyxlike lesions.7

Some patients have been reported to present with facial angioedema; the clinical diagnosis of CD can be challenging when facial edema is more prominent than eczema.6 Furthermore, in a reported case of P obconica CD, the patient’s vesicular hand dermatitis became pustular and spread to the face.8

Allergy Testing

Patch testing is performed with synthetic primin to detect allergens of P obconica in patients who are sensitive to them, which can be useful because Primula dermatitis can have variable presentations and cases can be missed if patch testing is not performed.9 Diagnostic mimics—herpes simplex, pompholyx, seborrheic dermatitis, and scabies—should be considered before patch testing.7

Prevention and Treatment

Preventive Measures—Ideally, once CD occurs in response to P obconica, handling of and other exposure to the plant should be halted; thus, prevention becomes the mainstay of treatment. Alternatively, when exposure is a necessary occupational hazard, nitrile gloves should be worn; allergenicity can be decreased by overwatering or introducing more primin-free varieties.3,10

Cultivating the plant outdoors during the winter in milder climates can potentially decrease sensitivity because allergen production is lowest during cold months and highest during summer.11 Because P obconica is commonly grown indoors, allergenicity can persist year-round.

Pharmacotherapy—Drawing on experience treating CD caused by other plants, acute and chronic P obconica CD are primarily treated with a topical steroid or, if the face or genitals are affected, with a steroid-sparing agent, such as tacrolimus.12 A cool compress of water, saline, or Burow solution (aluminum acetate in water) can help decrease acute inflammation, especially in the setting of vesiculation.13

Mild CD also can be treated with a barrier cream and lipid-rich moisturizer. Their effectiveness likely is due to increased hydration and aiding impaired skin-barrier repair.14

Some success in treating chronic CD also has been reported with psoralen plus UVA and UVB light therapy, which function as local immunosuppressants, thus decreasing inflammation.15

Final Thoughts

Contact dermatitis caused by P obconica is common in Europe but less common in the United States and therefore often is underrecognized. Avoiding contact with the plant should be strongly recommended to allergic persons. Primula obconica allergic CD can be treated with a topical steroid.

Etiology

Calcareous soils of central and southwest China are home to Primula obconica1 (also known as German primrose and Libre Magenta).2 Primula obconica was introduced to Europe in the 1880s, where it became a popular ornamental and decorative household plant (Figure).3 It also is a frequent resident of greenhouses.

Primula obconica is a member of the family Primulaceae, which comprises semi-evergreen perennials. The genus name Primula is derived from Latin meaning “first”; obconica refers to the conelike shape of the plant’s vivid, cerise-red flowers.

Allergens From P obconica

The allergens primin (2-methoxy-6-pentyl-1,4-benzoquinone) and miconidin (2-methoxy-6-pentyl-1, 4-dihydroxybenzene) have been isolated from P obconica stems, leaves, and flowers. Allergies to P obconica are much more commonly detected in Europe than in the United States because the plant is part of standard allergen screening in dermatology clinics in Europe.4 In a British patch test study of 234 patients with hand dermatitis, 34 displayed immediate or delayed sensitization to P obconica allergens.5 However, in another study, researchers who surveyed the incidence of P obconica allergic contact dermatitis (CD) in the United Kingdom found a notable decline in the number of primin-positive patch tests from 1995 to 2000, which likely was attributable to a decrease in the number of plant retailers who stocked P obconica and the availability of primin-free varieties from 50% of suppliers.3 Furthermore, a study in the United States of 567 consecutive patch tests that included primin as part of standard screening found only 1 positive reaction, suggesting that routine patch testing for P obconica in the United States would have a low yield unless the patient has a relevant history.4

Cutaneous Presentation

Clinical features of P obconica–induced dermatitis include fingertip dermatitis, as well as facial, hand, and forearm dermatitis.6 Patients typically present with lichenification and fissuring of the fingertips; fingertip vesicular dermatitis; or linear erythematous streaks, vesicles, and bullae on the forearms, hands, and face. Vesicles and bullae can be hemorrhagic in patients with pompholyxlike lesions.7

Some patients have been reported to present with facial angioedema; the clinical diagnosis of CD can be challenging when facial edema is more prominent than eczema.6 Furthermore, in a reported case of P obconica CD, the patient’s vesicular hand dermatitis became pustular and spread to the face.8

Allergy Testing

Patch testing is performed with synthetic primin to detect allergens of P obconica in patients who are sensitive to them, which can be useful because Primula dermatitis can have variable presentations and cases can be missed if patch testing is not performed.9 Diagnostic mimics—herpes simplex, pompholyx, seborrheic dermatitis, and scabies—should be considered before patch testing.7

Prevention and Treatment

Preventive Measures—Ideally, once CD occurs in response to P obconica, handling of and other exposure to the plant should be halted; thus, prevention becomes the mainstay of treatment. Alternatively, when exposure is a necessary occupational hazard, nitrile gloves should be worn; allergenicity can be decreased by overwatering or introducing more primin-free varieties.3,10

Cultivating the plant outdoors during the winter in milder climates can potentially decrease sensitivity because allergen production is lowest during cold months and highest during summer.11 Because P obconica is commonly grown indoors, allergenicity can persist year-round.

Pharmacotherapy—Drawing on experience treating CD caused by other plants, acute and chronic P obconica CD are primarily treated with a topical steroid or, if the face or genitals are affected, with a steroid-sparing agent, such as tacrolimus.12 A cool compress of water, saline, or Burow solution (aluminum acetate in water) can help decrease acute inflammation, especially in the setting of vesiculation.13

Mild CD also can be treated with a barrier cream and lipid-rich moisturizer. Their effectiveness likely is due to increased hydration and aiding impaired skin-barrier repair.14

Some success in treating chronic CD also has been reported with psoralen plus UVA and UVB light therapy, which function as local immunosuppressants, thus decreasing inflammation.15

Final Thoughts

Contact dermatitis caused by P obconica is common in Europe but less common in the United States and therefore often is underrecognized. Avoiding contact with the plant should be strongly recommended to allergic persons. Primula obconica allergic CD can be treated with a topical steroid.

- Nan P, Shi S, Peng S, et al. Genetic diversity in Primula obconica (Primulaceae) from Central and South‐west China as revealed by ISSR markers. Ann Bot. 2003;91:329-333. doi:10.1093/AOB/MCG018

- Primula obconica “Libre Magenta” (Ob). The Royal Horticultural Society. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/131697/i-primula-obconica-i-libre-magenta-(ob)/details

- Connolly M, McCune J, Dauncey E, et al. Primula obconica—is contact allergy on the decline? Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:167-171. doi:10.1111/J.0105-1873.2004.00427.X

- Mowad C. Routine testing for Primula obconica: is it useful in the United States? Am J Contact Dermat. 1998;9:231-233.

- Agrup C, Fregert S, Rorsman H. Sensitization by routine patch testing with ether extract of Primula obconica. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:897-898. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1969.TB15970.X

- Lleonart Bellfill R, Casas Ramisa R, Nevot Falcó S. Primula dermatitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 1999;27:29-31.

- Thomson KF, Charles-Holmes R, Beck MH. Primula dermatitis mimicking herpes simplex. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:185-186. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0536.1997.TB00200.X

- Tabar AI, Quirce S, García BE, et al. Primula dermatitis: versatility in its clinical presentation and the advantages of patch tests with synthetic primin. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;30:47-48. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0536.1994.tb00734.X

- Apted JH. Primula obconica sensitivity and testing with primin. Australas J Dermatol. 1988;29:161-162. doi:10.1111/J.1440-0960.1988.TB00390.X

- Aplin CG, Lovell CR. Contact dermatitis due to hardy Primula species and their cultivars. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:23-29. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2001.440105.X

- Christensen LP, Larsen E. Direct emission of the allergen primin from intact Primula obconica plants. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:149-153. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2000.042003149.X

- Esser PR, Mueller S, Martin SF. Plant allergen-induced contact dermatitis. Planta Med. 2019;85:528-534. doi:10.1055/A-0873-1494

- Levin CY, Maibach HI. Do cool water or physiologic saline compresses enhance resolution of experimentally-induced irritant contact dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:146-150. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2001.045003146.X

- M, Lindberg M. The influence of a single application of different moisturizers on the skin capacitance. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:79-82.

- Levin CY, Maibach HI. Irritant contact dermatitis: is there an immunologic component? Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:183-189. doi:10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00171-0

- Nan P, Shi S, Peng S, et al. Genetic diversity in Primula obconica (Primulaceae) from Central and South‐west China as revealed by ISSR markers. Ann Bot. 2003;91:329-333. doi:10.1093/AOB/MCG018

- Primula obconica “Libre Magenta” (Ob). The Royal Horticultural Society. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/131697/i-primula-obconica-i-libre-magenta-(ob)/details

- Connolly M, McCune J, Dauncey E, et al. Primula obconica—is contact allergy on the decline? Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:167-171. doi:10.1111/J.0105-1873.2004.00427.X

- Mowad C. Routine testing for Primula obconica: is it useful in the United States? Am J Contact Dermat. 1998;9:231-233.

- Agrup C, Fregert S, Rorsman H. Sensitization by routine patch testing with ether extract of Primula obconica. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:897-898. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1969.TB15970.X

- Lleonart Bellfill R, Casas Ramisa R, Nevot Falcó S. Primula dermatitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 1999;27:29-31.

- Thomson KF, Charles-Holmes R, Beck MH. Primula dermatitis mimicking herpes simplex. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:185-186. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0536.1997.TB00200.X

- Tabar AI, Quirce S, García BE, et al. Primula dermatitis: versatility in its clinical presentation and the advantages of patch tests with synthetic primin. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;30:47-48. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0536.1994.tb00734.X

- Apted JH. Primula obconica sensitivity and testing with primin. Australas J Dermatol. 1988;29:161-162. doi:10.1111/J.1440-0960.1988.TB00390.X

- Aplin CG, Lovell CR. Contact dermatitis due to hardy Primula species and their cultivars. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:23-29. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2001.440105.X

- Christensen LP, Larsen E. Direct emission of the allergen primin from intact Primula obconica plants. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:149-153. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2000.042003149.X

- Esser PR, Mueller S, Martin SF. Plant allergen-induced contact dermatitis. Planta Med. 2019;85:528-534. doi:10.1055/A-0873-1494

- Levin CY, Maibach HI. Do cool water or physiologic saline compresses enhance resolution of experimentally-induced irritant contact dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:146-150. doi:10.1034/J.1600-0536.2001.045003146.X

- M, Lindberg M. The influence of a single application of different moisturizers on the skin capacitance. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:79-82.

- Levin CY, Maibach HI. Irritant contact dermatitis: is there an immunologic component? Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:183-189. doi:10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00171-0

Practice Points

- Primula obconica is a household plant that can cause contact dermatitis (CD). Spent blossoms must be pinched off to keep the plant blooming, resulting in fingertip dermatitis.

- In the United States, P obconica is not a component of routine patch testing; therefore, it might be missed as the cause of an allergic reaction.

- Primin and miconidin are the principal allergens known to be responsible for causing P obconica dermatitis.

- Treatment of this condition is similar to the usual treatment of plant-induced CD: avoiding exposure to the plant and applying a topical steroid.

How to Advise Medical Students Interested in Dermatology: A Survey of Academic Dermatology Mentors

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

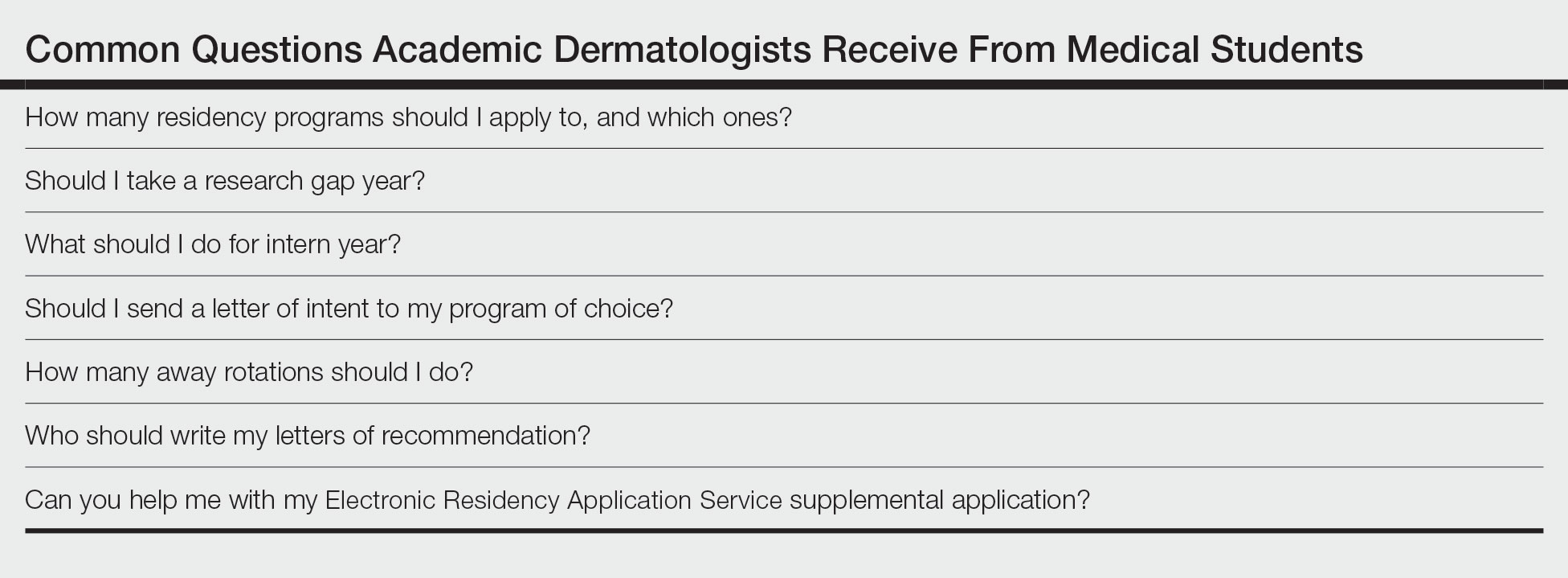

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

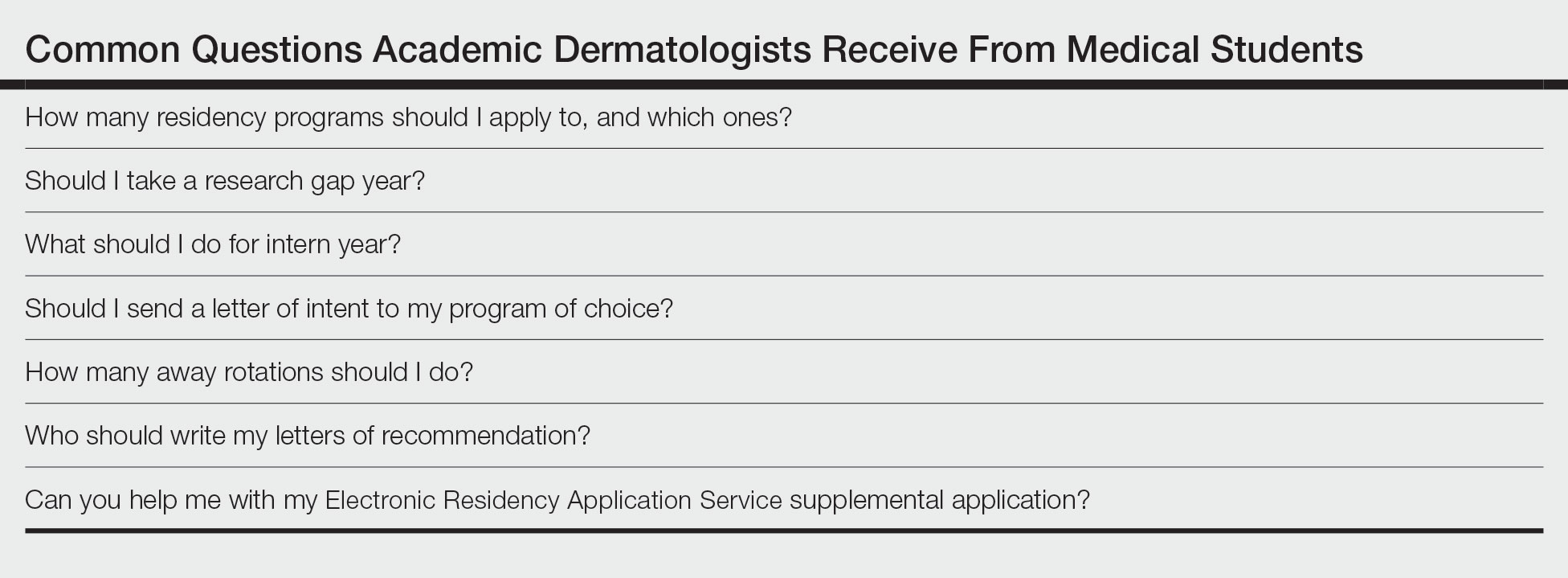

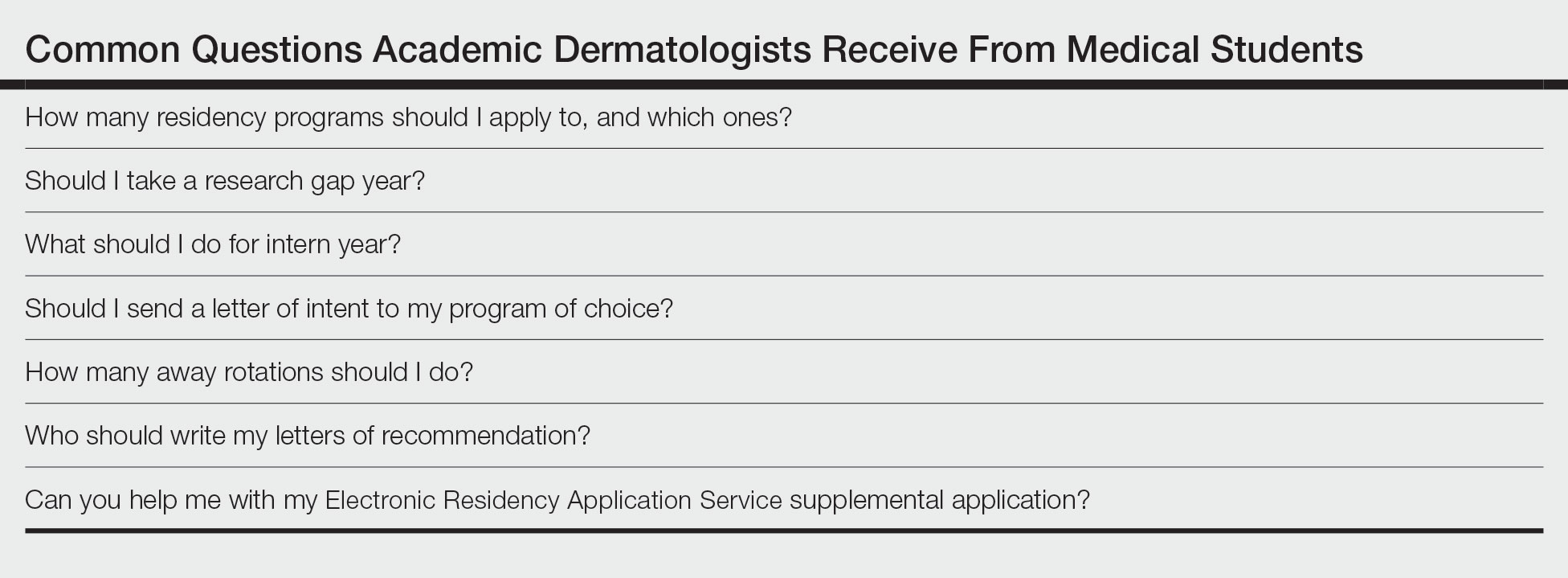

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

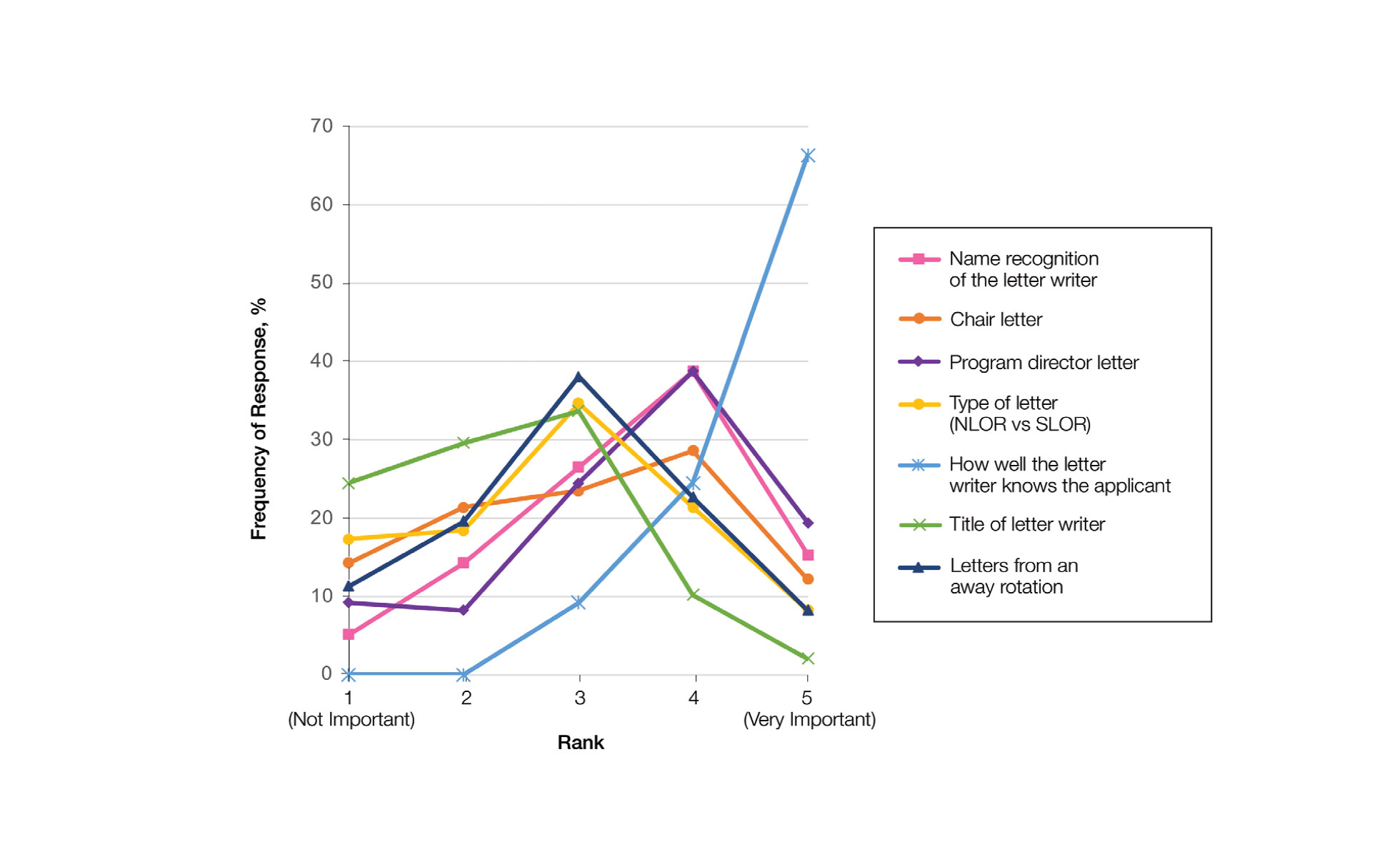

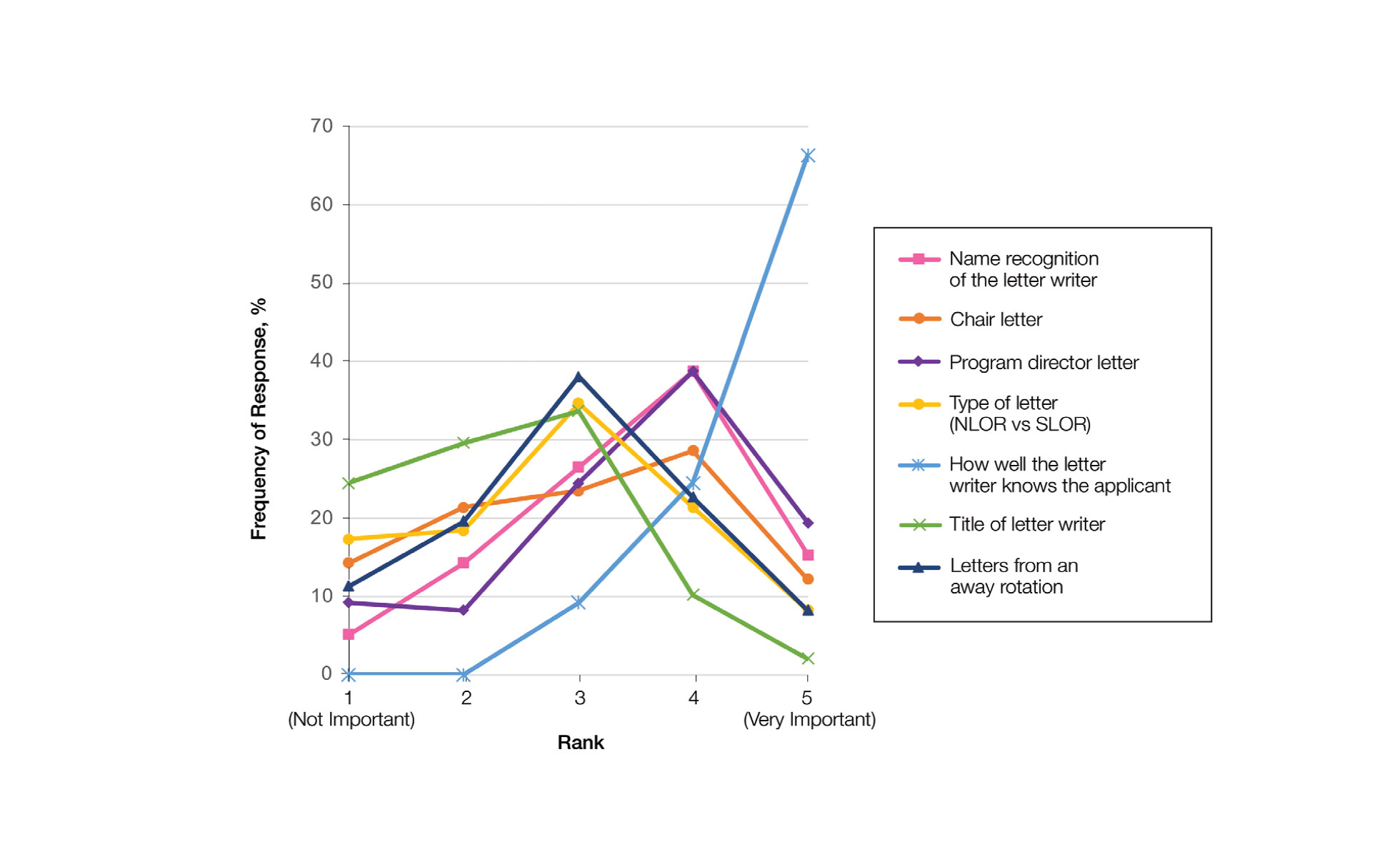

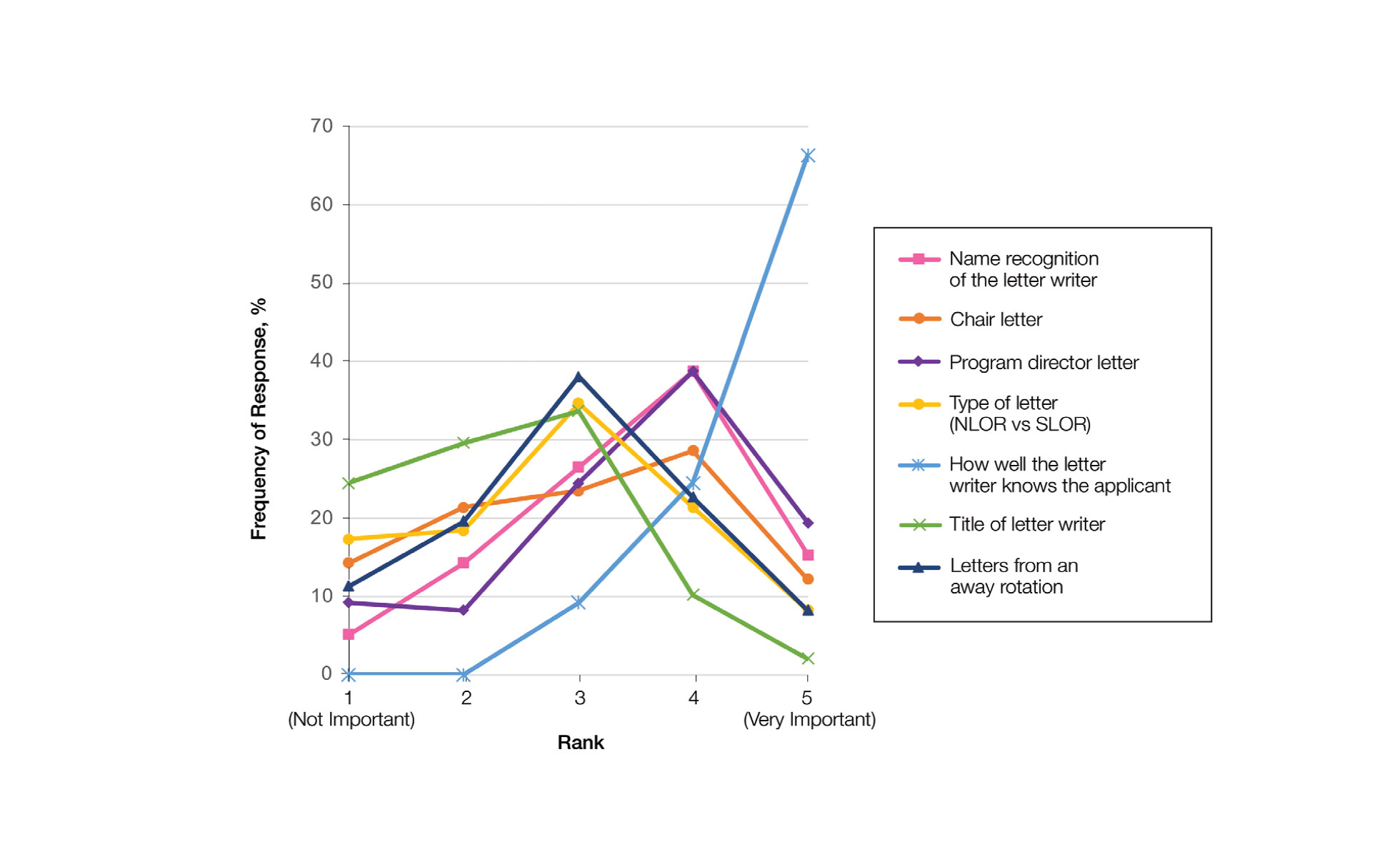

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in medicine. In 2022, there were 851 applicants (613 doctor of medicine seniors, 85 doctor of osteopathic medicine seniors) for 492 postgraduate year (PGY) 2 positions.1 During the 2022 application season, the average matched dermatology candidate had 7.2 research experiences; 20.9 abstracts, presentations, or publications; 11 volunteer experiences; and a US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Knowledge score of 257.1 With hopes of matching into such a competitive field, students often seek advice from academic dermatology mentors. Such advice may substantially differ based on each mentor and may or may not be evidence based.

We sought to analyze the range of advice given to medical students applying to dermatology residency programs via a survey to members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) with the intent to help applicants and mentors understand how letters of intent, letters of recommendation (LORs), and Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) supplemental applications are used by dermatology programs nationwide.

Methods

The study was reviewed by The Ohio State University institutional review board and was deemed exempt. A branching-logic survey with common questions from medical students while applying to dermatology residency programs (Table) was sent to all members of APD through the email listserve. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) to ensure data security.

The survey was distributed from August 28, 2022, to September 12, 2022. A total of 101 surveys were returned from 646 listserve members (15.6%). Given the branching-logic questions, differing numbers of responses were collected for each question. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze and report the results.

Results

Residency Program Number—Members of the APD were asked if they recommend students apply to a certain number of programs, and if so, how many programs. Of members who responded, 62.2% (61/98) either always (22.4% [22/98]) or sometimes (40.2% [39/97]) suggested students apply to a certain number of programs. When mentors made a recommendation, 54.1% (33/61) recommended applying to 59 or fewer programs, with only 9.8% (6/61) recommending students apply to 80 or more programs.

Gap Year—We queried mentors about their recommendations for a research gap year and asked which applicants should pursue this extra year. Our survey found that 74.5% of mentors (73/98) almost always (4.1% [4/98]) or sometimes (70.4% [69/98]) recommended a research gap year, most commonly for those applicants with a strong research interest (71.8% [51/71]). Other reasons mentors recommended a dedicated research year during medical school included low USMLE Step scores (50.7% [36/71]), low grades (45.1% [32/71]), little research (46.5% [33/71]), and no home program (43.7% [31/71]).

Internship Choices—Our survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (63.3% [62/98]) of mentors did not give applicants a recommendation on type of internship (PGY-1). If a recommendation was given, academic dermatologists more commonly recommended an internal medicine preliminary year (29.6% [29/98]) over a transitional year (7.1% [7/98]).

Communication of Interest Via a Letter of Intent—We asked mentors if they recommended applicants send a letter of intent and conversely if receiving a letter of intent impacted their rank list. Nearly half (48.5% [47/97]) of mentors indicated they did not recommend sending a letter of intent, with only 15.5% (15/97) of mentors regularly recommending this practice. Additionally, 75.8% of mentors indicated that a letter of intent never (42.1% [40/95]) or rarely (33.7% [32/95]) impacted their rank list.

Rotation Choices—We queried mentors if they recommended students complete away rotations, and if so, how many rotations did they recommend. We found that 85.9% (85/99) of mentors recommended students complete an away rotation; 63.1% (53/84) of them recommended performing 2 away rotations, and 14.3% (12/84) of respondents recommended students complete 3 away rotations. More than a quarter of mentors (27.1% [23/85]) indicated their home medical schools limited the number of away rotations a medical student could complete in any 1 specialty, and 42.4% (36/85) of respondents were unsure if such a limitation existed.

Letters of Recommendation—Our survey asked respondents to rank various factors on a 5-point scale (1=not important; 5=very important) when deciding who should write the students’ LORs. Mentors indicated that the most important factor for letter-writer selection was how well the letter writer knows the applicant, with 90.8% (89/98) of mentors rating the importance of this quality as a 4 or 5 (Figure). More than half of respondents rated the name recognition of the letter writer and program director letter as a 4 or 5 in importance (54.1% [53/98] and 58.2% [57/98], respectively). Type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), title of letter writer, letters from an away rotation, and chair letter scored lower, with fewer than half of mentors rating these as a 4 or 5 in importance.

Supplemental Application—When asked about the 2022 application cycle, respondents of our survey reported that the supplemental application was overall more important in deciding which applicants to interview vs which to rank highly. Prior experiences were important (ranked 4 or 5) for 58.8% (57/97) of respondents in choosing applicants to interview, and 49.4% (48/97) of respondents thought prior experiences were important for ranking. Similarly, 34.0% (33/97) of mentors indicated geographic preference was important (ranked 4 or 5) for interview compared with only 23.8% (23/97) for ranking. Finally, 57.7% (56/97) of our survey respondents denoted that program signals were important or very important in choosing which applicants to interview, while 32.0% (31/97) indicated that program signals were important in ranking applicants.

Comment

Residency Programs: Which Ones, and How Many?—The number of applications for dermatology residency programs has increased 33.9% from 2010 to 2019.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges Apply Smart data from 2013 to 2017 indicate that dermatology applicants arrive at a point of diminishing return between 37 and 62 applications, with variation within that range based on USMLE Step 1 score,3 and our data support this with nearly two-thirds of dermatology advisors recommending students apply within this range. Despite this data, dermatology residency applicants applied to more programs over the last decade (64.8 vs 77.0),2 likely to maximize their chance of matching.

Research Gap Years During Medical School—Prior research has shown that nearly half of faculty indicated that a research year during medical school can distinguish similar applicants, and close to 25% of applicants completed a research gap year.4,5 However, available data indicate that taking a research gap year has no effect on match rate or number of interview invites but does correlate with match rates at the highest ranked dermatology residency programs.6-8

Our data indicate that the most commonly recommended reason for a research gap year was an applicants’ strong interest in research. However, nearly half of dermatology mentors recommended research years during medical school for reasons other than an interest in research. As research gap years increase in popularity, future research is needed to confirm the consequence of this additional year and which applicants, if any, will benefit from such a year.

Preferences for Intern Year—Prior research suggests that dermatology residency program directors favor PGY-1 preliminary medicine internships because of the rigor of training.9,10 Our data continue to show a preference for internal medicine preliminary years over transitional years. However, given nearly two-thirds of dermatology mentors do not give applicants any recommendations on PGY-1 year, this preference may be fading.

Letters of Intent Not Recommended—Research in 2022 found that 78.8% of dermatology applicants sent a letter of intent communicating a plan to rank that program number 1, with nearly 13% sending such a letter to more than 1 program.11 With nearly half of mentors in our survey actively discouraging this process and more than 75% of mentors not utilizing this letter, the APD issued a brief statement on the 2022-2023 application cycle stating, “Post-interview communication of preference—including ‘letters of intent’ and thank you letters—should not be sent to programs. These types of communication are typically not used by residency programs in decision-making and lead to downstream pressures on applicants.”12

Away Rotations—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data demonstrated that nearly one-third of dermatology applicants (29%) matched at their home institution, and nearly one-fifth (18%) matched where they completed an away rotation.13 In-person away rotations were eliminated in 2020 and restricted to 1 away rotation in 2021. Restrictions regarding away rotations were removed in 2022. Our data indicate that dermatology mentors strongly supported an away rotation, with more than half of them recommending at least 2 away rotations.

Further research is needed to determine the effect numerous away rotations have on minimizing students’ exposure to other specialties outside their chosen field. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine the impact away rotations have on economically disadvantaged students, students without home programs, and students with families. In an effort to standardize the number of away rotations, the APD issued a statement for the 2023-2024 application cycle indicating that dermatology applicants should limit away rotations to 2 in-person electives. Students without a home dermatology program could consider completing up to 3 electives.14

Who Should Write LORs?—Research in 2014 demonstrated that LORs were very important in determining applicants to interview, with a strong preference for LORs from academic dermatologists and colleagues.15 Our data strongly indicated applicants should predominantly ask for letters from writers who know them well. The majority of mentors did not give value to the rank of the letter writer (eg, assistant professor, associate professor, professor), type of letter, chair letters, or letters from an away rotation. These data may help alleviate stress many students feel as they search for letter writers.

How is the Supplemental Application Used?—In 2022, the ERAS supplemental application was introduced, which allowed applicants to detail 5 meaningful experiences, describe impactful life challenges, and indicate preferences for geographic region. Dermatology residency applicants also were able to choose 3 residency programs to signal interest in that program. Our data found that the supplemental application was utilized predominantly to select applicants to interview, which is in line with the Association of American Medical Colleges’ and APD guidelines indicating that this tool is solely meant to assist with application review.16 Further research and data will hopefully inform approaches to best utilize the ERAS supplemental application data.

Limitations—Our data were limited by response rate and sample size, as only academic dermatologists belonging to the APD were queried. Additionally, we did not track personal information of the mentors, so more than 1 mentor may have responded from a single institution, making it possible that our data may not be broadly applicable to all institutions.

Conclusion

Although there is no algorithmic method of advising medical students who are interested in dermatology, our survey data help to describe the range of advice currently given to students, which can improve and guide future recommendations. Additionally, some of our data demonstrate a discrepancy between mentor advice and current medical student practice for the number of applications and use of a letter of intent. We hope our data will assist academic dermatology mentors in the provision of advice to mentees as well as inform organizations seeking to create standards and official recommendations regarding aspects of the application process.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. May 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

- Secrest AM, Coman GC, Swink JM, et al. Limiting residency applications to dermatology benefits nearly everyone. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:30-32.

- Apply smart for residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency

- Shamloul N, Grandhi R, Hossler E. Perceived importance of dermatology research fellowships. Presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group; October 3, 2020.

- Runge M, Jairath NK, Renati S, et al. Pursuit of a research year or dual degree by dermatology residency applicants: a cross-sectional study. Cutis. 2022;109:E12-E13.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the Match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt4604h1w4.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2021;34:59-62.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:595-601.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Residency Program Directors Section. Updated Information Regarding the 2022-2023 Application Cycle. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20statement%20on%202022-2023%20application%20cycle_updated%20Oct.pdf

- Narang J, Morgan F, Eversman A, et al. Trends in geographic and home program preferences in the dermatology residency match: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:645-647.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section. Recommendations Regarding Away Electives. Updated December 14, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- Kaffenberger BH, Kaffenberger JA, Zirwas MJ. Academic dermatologists’ views on the value of residency letters of recommendation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:395-396.

- Supplemental ERAS Application: Guide for Residency Program. Association of American Medical Colleges; June 2022.

Practice Points

- Dermatology mentors recommend students apply to 60 or fewer programs, with only a small percentage of faculty routinely recommending students apply to more than 80 programs.

- Dermatology mentors strongly recommend that students should not send a letter of intent to programs, as it rarely is used in the ranking process.

- Dermatology mentors encourage students to ask for letters of recommendation from writers who know them the best, irrespective of the letter writer’s rank or title. The type of letter (standardized vs nonstandardized), chair letter, or letters from an away rotation do not hold as much importance.

Inequity, Bias, Racism, and Physician Burnout: Staying Connected to Purpose and Identity as an Antidote

“Where are you really from?”

When I tell patients I am from Casper, Wyoming—wh ere I have lived the majority of my life—it’smet with disbelief. The subtext: YOU can’t be from THERE.

I didn’t used to think much of comments like this, but as I have continued to hear them, I find myself feeling tired—tired of explaining myself, tired of being treated differently than my colleagues, and tired of justifying myself. My experiences as a woman of color sadly are not uncommon in medicine.

Sara Martinez-Garcia, BA

Racial bias and racism are steeped in the culture of medicine—from the medical school admissions process1,2 to the medical training itself.3 More than half of medical students who identify as underrepresented in medicine (UIM) experience microaggressions.4 Experiencing racism and sexism in the learning environment can lead to burnout, and microaggressions promote feelings of self-doubt and isolation. Medical students who experience microaggressions are more likely to report feelings of burnout and impaired learning.4 These experiences can leave one feeling as if “You do not belong” and “You are unworthy of being in this position.”

Addressing physician burnout already is complex, and addressing burnout caused by inequity, bias, and racism is even more so. In an ideal world, we would eliminate inequity, bias, and racism in medicine through institutional and individual actions. There has been movement to do so. For example, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which oversees standards for US resident and fellow training, launched ACGME Equity Matters (https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/ACGME-Equity-Matters/), an initiative aimed to improve diversity, equity, and antiracism practices within graduate medical eduation. However, we know that education alone isn’t enough to fix this monumental problem. Traditional diversity training as we have known it has never been demonstrated to contribute to lasting changes in behavior; it takes much more extensive and complex interventions to meaningfully reduce bias.5 In the meantime, we need action. As a medical community, we need to be better about not turning the other way when we see these things happening in our classrooms and in our hospitals. As individuals, we must self-reflect on the role that we each play in contributing to or combatting injustices and seek out bystander training to empower us to speak out against acts of bias such as sexism or racism. Whether it is supporting a fellow colleague or speaking out against an inappropriate interaction, we can all do our part. A very brief list of actions and resources to support our UIM students and colleagues are listed in the Table; those interested in more in-depth resources are encouraged to explore the Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit (https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/cfas/diversity-inclusion-toolkit/resources).

We can’t change the culture of medicine quickly or even in our lifetime. In the meantime, those who are UIM will continue to experience these events that erode our well-being. They will continue to need support. Discussing mental health has long been stigmatized, and physicians are no exception. Many physicians are hesitant to discuss mental health issues out of fear of judgement and perceived or even real repercussions on their careers.10 However, times are changing and evolving with the current generation of medical students. It’s no secret that medicine is stressful. Most medical schools provide free counseling services, which lowers the barrier for discussions of mental health from the beginning. Making talk about mental health just as normal as talking about other aspects of health takes away the fear that “something is wrong with me” if someone seeks out counseling and mental health services. Faculty should actively check in and maintain open lines of communication, which can be invaluable for UIM students and their training experience. Creating an environment where trainees can be real and honest about the struggles they face in and out of the classroom can make everyone feel like they are not alone.

Addressing burnout in medicine is going to require an all-hands-on-deck approach. At an institutional level, there is a lot of room for improvement—improving systems for physicians so they are able to operate at their highest level (eg, addressing the burdens of prior authorizations and the electronic medical record), setting reasonable expectations around productivity, and creating work structures that respect work-life balance.11 But what can we do for ourselves? We believe that one of the most important ways to protect ourselves from burnout is to remember why. As a medical student, there is enormous pressure—pressure to learn an enormous volume of information, pass examinations, get involved in extracurricular activities, make connections, and seek research opportunities, while also cooking healthy food, grocery shopping, maintaining relationships with loved ones, and generally taking care of oneself. At times it can feel as if our lives outside of medical school are not important enough or valuable enough to make time for, but the pieces of our identity outside of medicine are what shape us into who we are today and are the roots of our purpose in medicine. Sometimes you can feel the most motivated, valued, and supported when you make time to have dinner with friends, call a family member, or simply spend time alone in the outdoors. Who you are and how you got to this point in your life are your identity. Reminding yourself of that can help when experiencing microaggressions or when that voice tries to tell you that you are not worthy. As you progress further in your career, maintaining that relationship with who you are outside of medicine can be your armor against burnout.

- Capers Q IV, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365-369.

- Lucey CR, Saguil A. The consequences of structural racism on MCAT scores and medical school admissions: the past is prologue. Acad Med. 2020;95:351-356.

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, South EC, Ray V. Medical schools as racialized organizations: a primer. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1143-1144.

- Chisholm LP, Jackson KR, Davidson HA, et al. Evaluation of racial microaggressions experienced during medical school training and the effect on medical student education and burnout: a validation study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:310-314.

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? the challenge for industry and academia. Anthropology Now. 2018;10:48-55.

- Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:57-60.

- Hackworth JM, Kotagal M, Bignall ONR, et al. Microaggressions: privileged observers’ duty to act and what they can do [published online December 1, 2021]. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052758.

- Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, et al. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41:1112-1117.

- Scott K. Just Work: How to Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Build a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity. St. Martin’s Press; 2021.

- Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161-3166.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

“Where are you really from?”

When I tell patients I am from Casper, Wyoming—wh ere I have lived the majority of my life—it’smet with disbelief. The subtext: YOU can’t be from THERE.

I didn’t used to think much of comments like this, but as I have continued to hear them, I find myself feeling tired—tired of explaining myself, tired of being treated differently than my colleagues, and tired of justifying myself. My experiences as a woman of color sadly are not uncommon in medicine.

Sara Martinez-Garcia, BA