User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Expelled from high school, Alister Martin became a Harvard doc

It’s not often that a high school brawl with gang members sets you down a path to becoming a Harvard-trained doctor. But that’s exactly how Alister Martin’s life unfolded.

In retrospect, he should have seen the whole thing coming. That night at the party, his best friend was attacked by a gang member from a nearby high school. Martin was not in a gang but he jumped into the fray to defend his friend.

“I wanted to save the day, but that’s not what happened,” he says. “There were just too many of them.”

When his mother rushed to the hospital, he was so bruised and bloody that she couldn’t recognize him at first. Ever since he was a baby, she had done her best to shield him from the neighborhood where gang violence was a regular disruption. But it hadn’t worked.

“My high school had a zero-tolerance policy for gang violence,” Martin says, “so even though I wasn’t in a gang, I was kicked out.”

Now expelled from high school, his mother wanted him out of town, fearing gang retaliation, or that Martin might seek vengeance on the boy who had brutally beaten him. So, the biology teacher and single mom who worked numerous jobs to keep them afloat, came up with a plan to get him far away from any temptations.

Martin had loved tennis since middle school, when his 8th-grade math teacher, Billie Weise, also a tennis pro, got him a job as a court sweeper at an upscale tennis club nearby. He knew nothing then about tennis but would come to fall in love with the sport. To get her son out of town, Martin’s mother took out loans for $30,000 and sent him to a Florida tennis training camp.

After 6 months of training, Martin, who earned a GED degree while attending the camp, was offered a scholarship to play tennis at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. The transition to college was tough, however. He was nervous and felt out of place. “I could have died that first day. It became so obvious how poorly my high school education had prepared me for this.”

But the unease he felt was also motivating in a way. Worried about failure, “he locked himself in a room with another student and they studied day and night,” recalls Kamal Khan, director of the office for diversity and academic success at Rutgers. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

And Martin displayed other attributes that would draw others to him – and later prove important in his career as a doctor. His ability to display empathy and interact with students and teachers separated him from his peers, Mr. Khan says. “There’re a lot of really smart students out there,” he says, “but not many who understand people like Martin.”

After graduating, he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He’d wanted to be a doctor since he was 10 years old after his mom was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. He remembers overhearing a conversation she was having with a family friend about where he would go if she died.

“That’s when I knew it was serious,” he says.

Doctors saved her life, and it’s something he’ll never forget. But it wasn’t until his time at Rutgers that he finally had the confidence to think he could succeed in medical school.

Martin went on to attend Harvard Medical School and Harvard Kennedy School of Government as well as serving as chief resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He was also a fellow at the White House in the Office of the Vice President and today, he’s an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston..

He is most at home in the emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he works as an emergency medical specialist. For him, the ER is the first line of defense for meeting the community’s health needs. Growing up in Neptune, the ER “was where poor folks got their care,” he says. His mom worked two jobs and when she got off work at 8 p.m. there was no pediatrician open. “When I was sick as a kid we always went to the emergency room,” he says.

While at Harvard, he also pursued a degree from the Kennedy School of Government, because of the huge role he feels that politics play in our health care system and especially in bringing care to impoverished communities. And since then he’s taken numerous steps to bridge the gap.

Addiction, for example, became an important issue for Martin, ever since a patient he encountered in his first week as an internist. She was a mom of two who had recently gotten surgery because she broke her ankle falling down the stairs at her child’s daycare, he says. Prescribed oxycodone, she feared she was becoming addicted and needed help. But at the time, there was nothing the ER could do.

“I remember that look in her eyes when we had to turn her away,” he says.

Martin has worked to change protocol at his hospital and others throughout the nation so they can be better set up to treat opioid addiction. He’s the founder of GetWaivered, an organization that trains doctors throughout the country to use evidence-based medicine to manage opioid addiction. In the U.S. doctors need what’s called a DEA X waiver to be able to prescribe buprenorphine to opioid-addicted patients. That means that currently only about 1% of all emergency room doctors nationwide have the waiver and without it, it’s impossible to help patients when they need it the most.

Shuhan He, MD, an internist with Martin at Massachusetts General Hospital who also works on the GetWaivered program, says Martin has a particular trait that helps him be successful.

“He’s a doer and when he sees a problem, he’s gonna try and fix it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not often that a high school brawl with gang members sets you down a path to becoming a Harvard-trained doctor. But that’s exactly how Alister Martin’s life unfolded.

In retrospect, he should have seen the whole thing coming. That night at the party, his best friend was attacked by a gang member from a nearby high school. Martin was not in a gang but he jumped into the fray to defend his friend.

“I wanted to save the day, but that’s not what happened,” he says. “There were just too many of them.”

When his mother rushed to the hospital, he was so bruised and bloody that she couldn’t recognize him at first. Ever since he was a baby, she had done her best to shield him from the neighborhood where gang violence was a regular disruption. But it hadn’t worked.

“My high school had a zero-tolerance policy for gang violence,” Martin says, “so even though I wasn’t in a gang, I was kicked out.”

Now expelled from high school, his mother wanted him out of town, fearing gang retaliation, or that Martin might seek vengeance on the boy who had brutally beaten him. So, the biology teacher and single mom who worked numerous jobs to keep them afloat, came up with a plan to get him far away from any temptations.

Martin had loved tennis since middle school, when his 8th-grade math teacher, Billie Weise, also a tennis pro, got him a job as a court sweeper at an upscale tennis club nearby. He knew nothing then about tennis but would come to fall in love with the sport. To get her son out of town, Martin’s mother took out loans for $30,000 and sent him to a Florida tennis training camp.

After 6 months of training, Martin, who earned a GED degree while attending the camp, was offered a scholarship to play tennis at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. The transition to college was tough, however. He was nervous and felt out of place. “I could have died that first day. It became so obvious how poorly my high school education had prepared me for this.”

But the unease he felt was also motivating in a way. Worried about failure, “he locked himself in a room with another student and they studied day and night,” recalls Kamal Khan, director of the office for diversity and academic success at Rutgers. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

And Martin displayed other attributes that would draw others to him – and later prove important in his career as a doctor. His ability to display empathy and interact with students and teachers separated him from his peers, Mr. Khan says. “There’re a lot of really smart students out there,” he says, “but not many who understand people like Martin.”

After graduating, he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He’d wanted to be a doctor since he was 10 years old after his mom was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. He remembers overhearing a conversation she was having with a family friend about where he would go if she died.

“That’s when I knew it was serious,” he says.

Doctors saved her life, and it’s something he’ll never forget. But it wasn’t until his time at Rutgers that he finally had the confidence to think he could succeed in medical school.

Martin went on to attend Harvard Medical School and Harvard Kennedy School of Government as well as serving as chief resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He was also a fellow at the White House in the Office of the Vice President and today, he’s an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston..

He is most at home in the emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he works as an emergency medical specialist. For him, the ER is the first line of defense for meeting the community’s health needs. Growing up in Neptune, the ER “was where poor folks got their care,” he says. His mom worked two jobs and when she got off work at 8 p.m. there was no pediatrician open. “When I was sick as a kid we always went to the emergency room,” he says.

While at Harvard, he also pursued a degree from the Kennedy School of Government, because of the huge role he feels that politics play in our health care system and especially in bringing care to impoverished communities. And since then he’s taken numerous steps to bridge the gap.

Addiction, for example, became an important issue for Martin, ever since a patient he encountered in his first week as an internist. She was a mom of two who had recently gotten surgery because she broke her ankle falling down the stairs at her child’s daycare, he says. Prescribed oxycodone, she feared she was becoming addicted and needed help. But at the time, there was nothing the ER could do.

“I remember that look in her eyes when we had to turn her away,” he says.

Martin has worked to change protocol at his hospital and others throughout the nation so they can be better set up to treat opioid addiction. He’s the founder of GetWaivered, an organization that trains doctors throughout the country to use evidence-based medicine to manage opioid addiction. In the U.S. doctors need what’s called a DEA X waiver to be able to prescribe buprenorphine to opioid-addicted patients. That means that currently only about 1% of all emergency room doctors nationwide have the waiver and without it, it’s impossible to help patients when they need it the most.

Shuhan He, MD, an internist with Martin at Massachusetts General Hospital who also works on the GetWaivered program, says Martin has a particular trait that helps him be successful.

“He’s a doer and when he sees a problem, he’s gonna try and fix it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not often that a high school brawl with gang members sets you down a path to becoming a Harvard-trained doctor. But that’s exactly how Alister Martin’s life unfolded.

In retrospect, he should have seen the whole thing coming. That night at the party, his best friend was attacked by a gang member from a nearby high school. Martin was not in a gang but he jumped into the fray to defend his friend.

“I wanted to save the day, but that’s not what happened,” he says. “There were just too many of them.”

When his mother rushed to the hospital, he was so bruised and bloody that she couldn’t recognize him at first. Ever since he was a baby, she had done her best to shield him from the neighborhood where gang violence was a regular disruption. But it hadn’t worked.

“My high school had a zero-tolerance policy for gang violence,” Martin says, “so even though I wasn’t in a gang, I was kicked out.”

Now expelled from high school, his mother wanted him out of town, fearing gang retaliation, or that Martin might seek vengeance on the boy who had brutally beaten him. So, the biology teacher and single mom who worked numerous jobs to keep them afloat, came up with a plan to get him far away from any temptations.

Martin had loved tennis since middle school, when his 8th-grade math teacher, Billie Weise, also a tennis pro, got him a job as a court sweeper at an upscale tennis club nearby. He knew nothing then about tennis but would come to fall in love with the sport. To get her son out of town, Martin’s mother took out loans for $30,000 and sent him to a Florida tennis training camp.

After 6 months of training, Martin, who earned a GED degree while attending the camp, was offered a scholarship to play tennis at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. The transition to college was tough, however. He was nervous and felt out of place. “I could have died that first day. It became so obvious how poorly my high school education had prepared me for this.”

But the unease he felt was also motivating in a way. Worried about failure, “he locked himself in a room with another student and they studied day and night,” recalls Kamal Khan, director of the office for diversity and academic success at Rutgers. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

And Martin displayed other attributes that would draw others to him – and later prove important in his career as a doctor. His ability to display empathy and interact with students and teachers separated him from his peers, Mr. Khan says. “There’re a lot of really smart students out there,” he says, “but not many who understand people like Martin.”

After graduating, he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He’d wanted to be a doctor since he was 10 years old after his mom was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. He remembers overhearing a conversation she was having with a family friend about where he would go if she died.

“That’s when I knew it was serious,” he says.

Doctors saved her life, and it’s something he’ll never forget. But it wasn’t until his time at Rutgers that he finally had the confidence to think he could succeed in medical school.

Martin went on to attend Harvard Medical School and Harvard Kennedy School of Government as well as serving as chief resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He was also a fellow at the White House in the Office of the Vice President and today, he’s an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston..

He is most at home in the emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he works as an emergency medical specialist. For him, the ER is the first line of defense for meeting the community’s health needs. Growing up in Neptune, the ER “was where poor folks got their care,” he says. His mom worked two jobs and when she got off work at 8 p.m. there was no pediatrician open. “When I was sick as a kid we always went to the emergency room,” he says.

While at Harvard, he also pursued a degree from the Kennedy School of Government, because of the huge role he feels that politics play in our health care system and especially in bringing care to impoverished communities. And since then he’s taken numerous steps to bridge the gap.

Addiction, for example, became an important issue for Martin, ever since a patient he encountered in his first week as an internist. She was a mom of two who had recently gotten surgery because she broke her ankle falling down the stairs at her child’s daycare, he says. Prescribed oxycodone, she feared she was becoming addicted and needed help. But at the time, there was nothing the ER could do.

“I remember that look in her eyes when we had to turn her away,” he says.

Martin has worked to change protocol at his hospital and others throughout the nation so they can be better set up to treat opioid addiction. He’s the founder of GetWaivered, an organization that trains doctors throughout the country to use evidence-based medicine to manage opioid addiction. In the U.S. doctors need what’s called a DEA X waiver to be able to prescribe buprenorphine to opioid-addicted patients. That means that currently only about 1% of all emergency room doctors nationwide have the waiver and without it, it’s impossible to help patients when they need it the most.

Shuhan He, MD, an internist with Martin at Massachusetts General Hospital who also works on the GetWaivered program, says Martin has a particular trait that helps him be successful.

“He’s a doer and when he sees a problem, he’s gonna try and fix it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Joint effort: CBD not just innocent bystander in weed

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

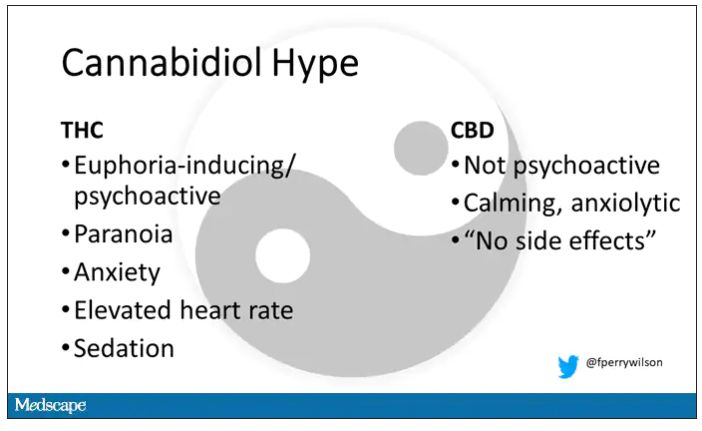

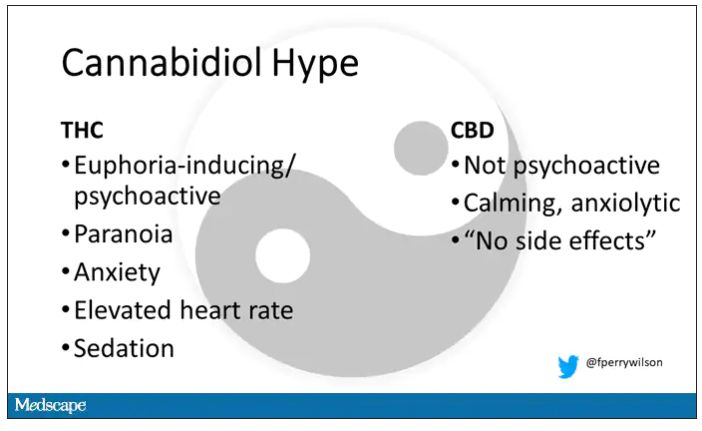

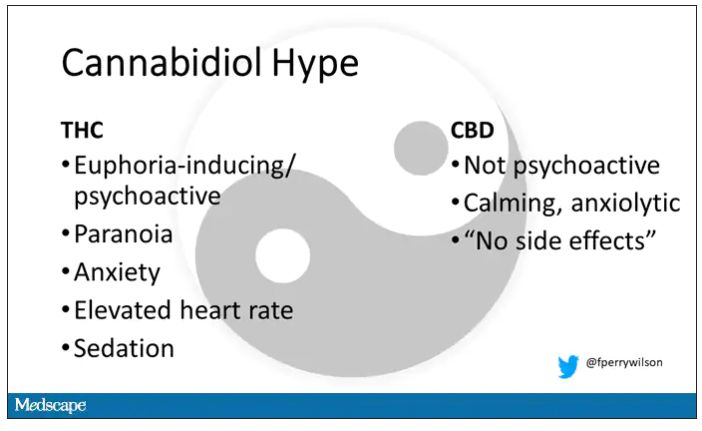

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

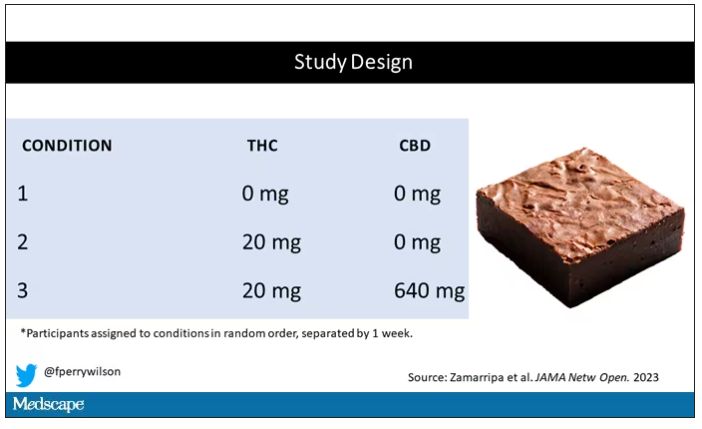

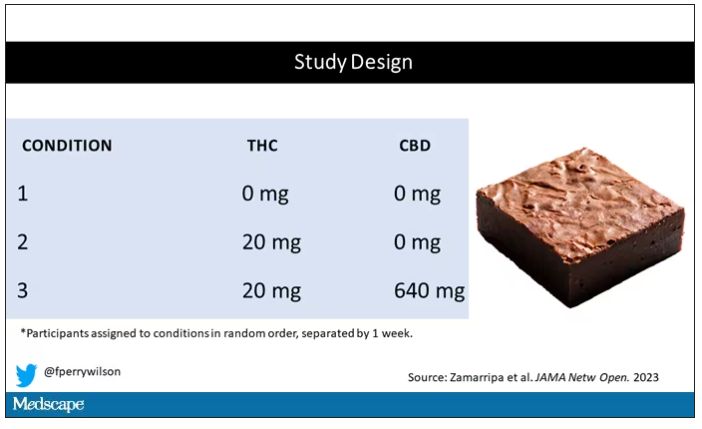

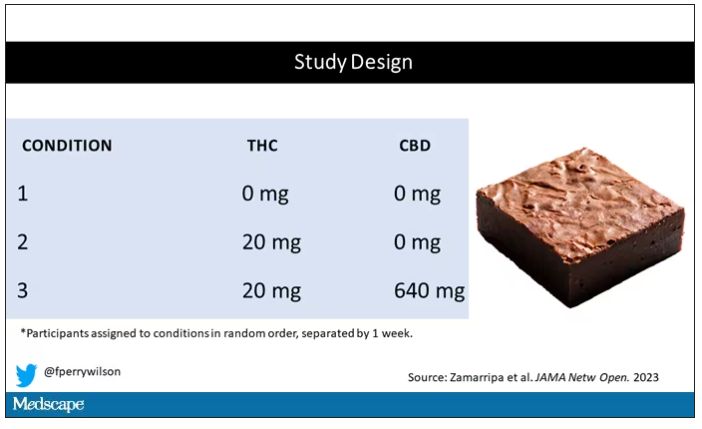

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

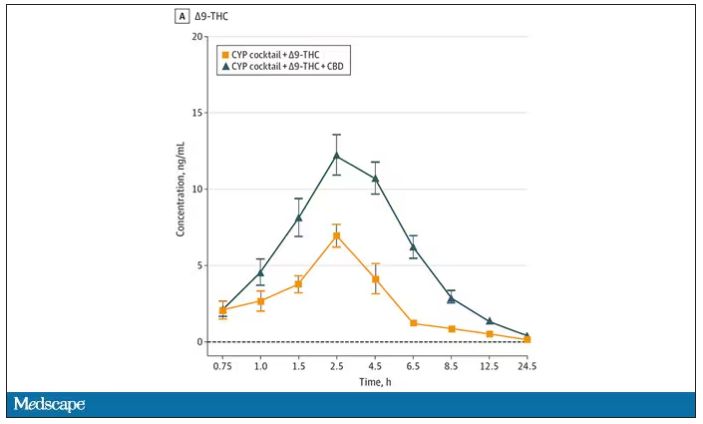

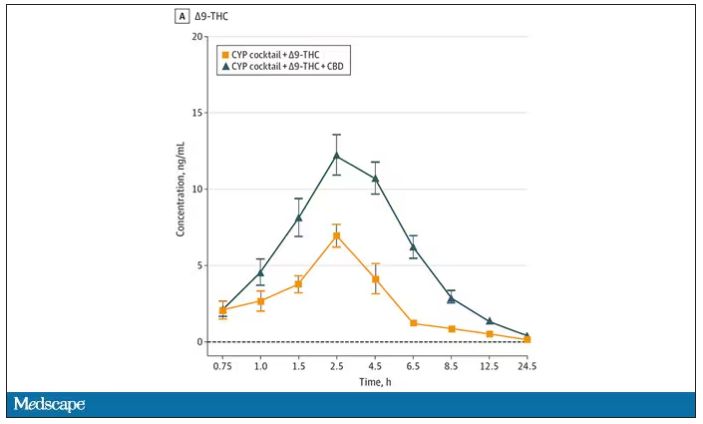

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

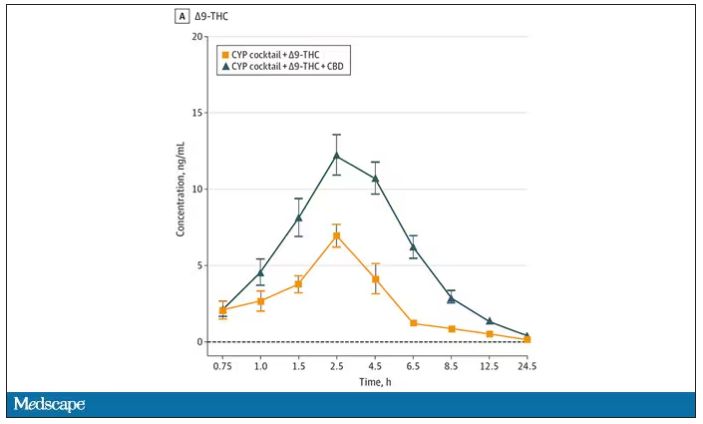

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

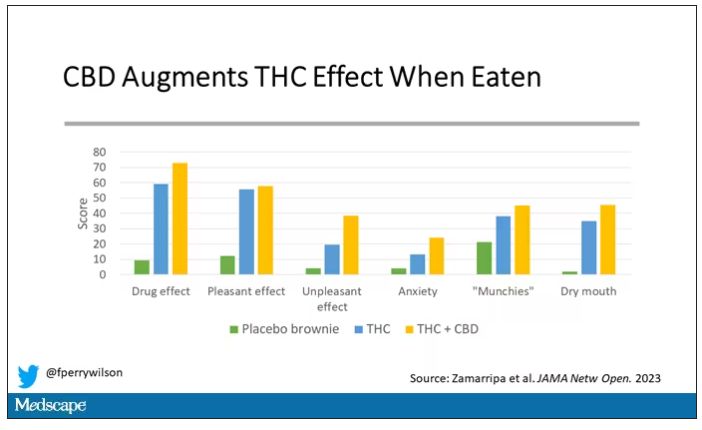

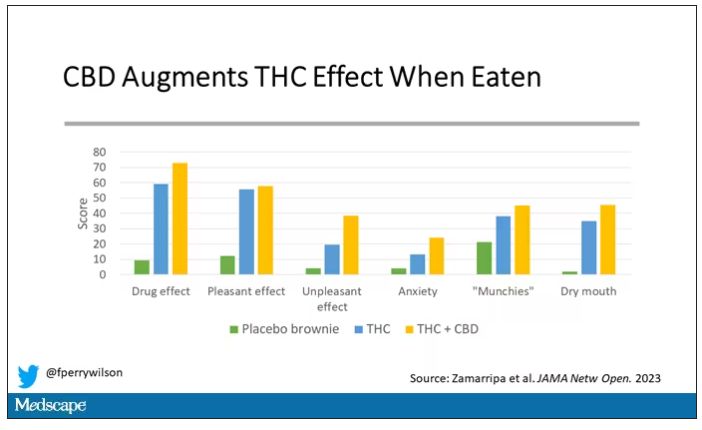

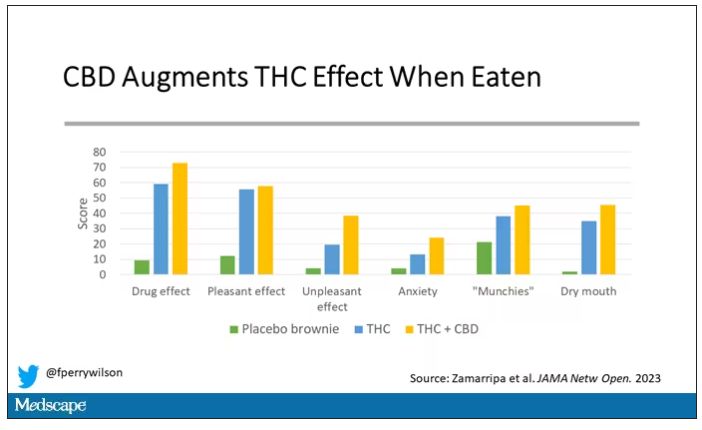

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

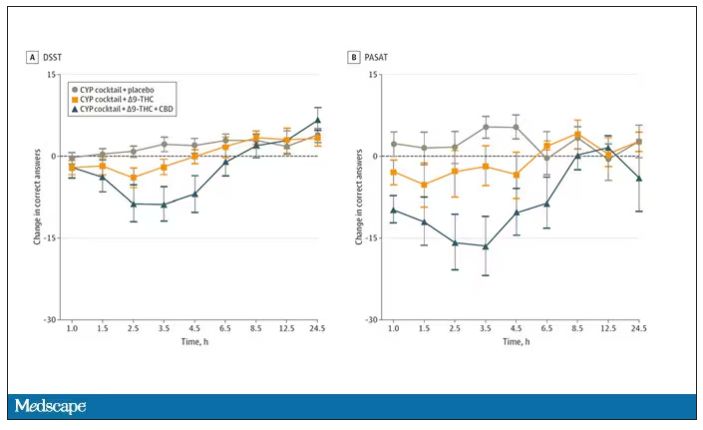

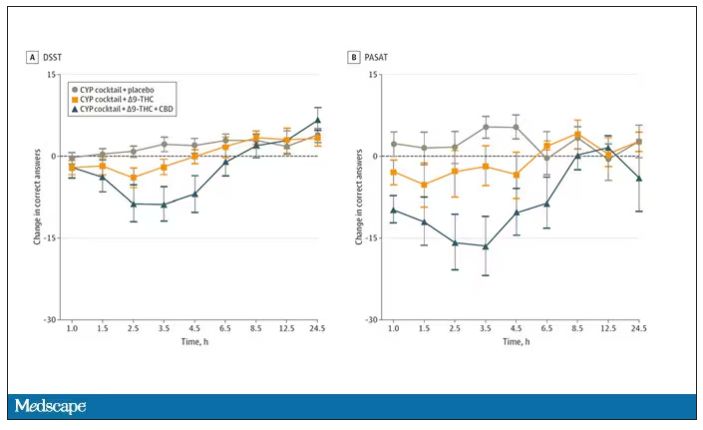

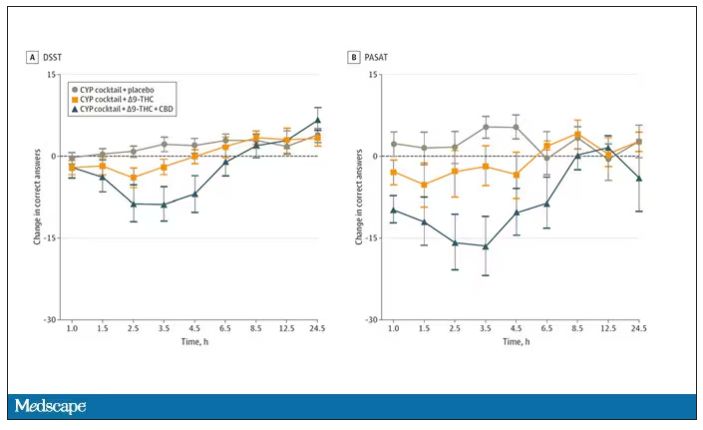

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

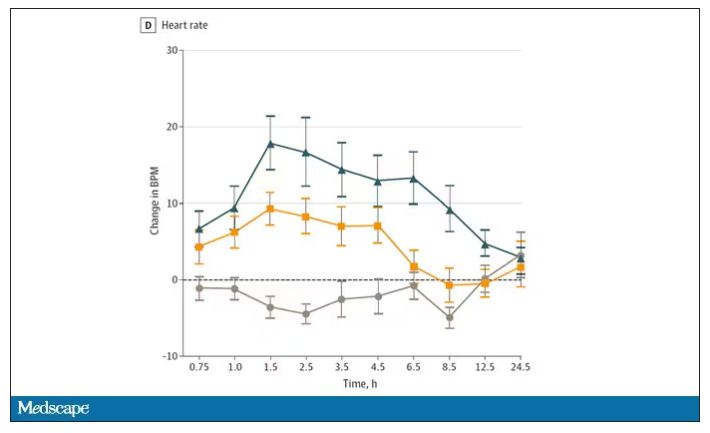

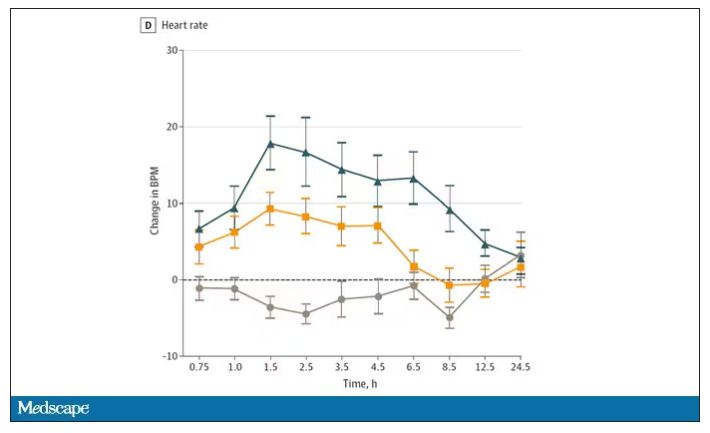

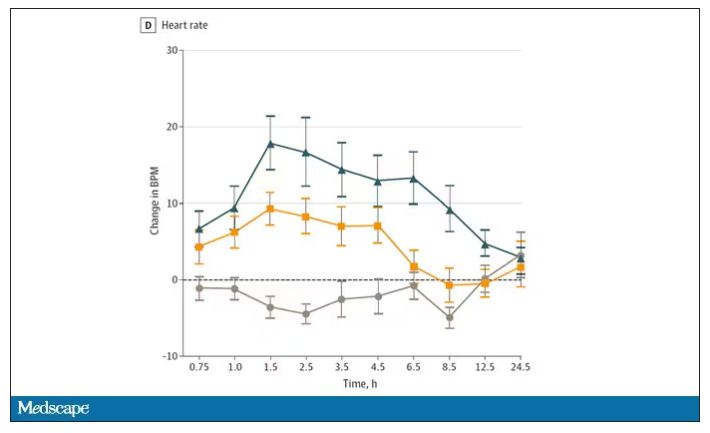

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors are disappearing from emergency departments as hospitals look to cut costs

She didn’t know much about miscarriage, but this seemed like one.

In the emergency department, she was examined then sent home, she said. She went back when her cramping became excruciating. Then home again. It ultimately took three trips to the ED on 3 consecutive days, generating three separate bills, before she saw a doctor who looked at her blood work and confirmed her fears.

“At the time I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I need to see a doctor,’ ” Ms. Valle recalled. “But when you think about it, it’s like, ‘Well, dang – why didn’t I see a doctor?’ ” It’s unclear whether the repeat visits were due to delays in seeing a physician, but the experience worried her. And she’s still paying the bills.

The hospital declined to discuss Ms. Valle’s care, citing patient privacy. But 17 months before her 3-day ordeal, Tennova had outsourced its emergency departments to American Physician Partners, a medical staffing company owned by private equity investors. APP employs fewer doctors in its EDs as one of its cost-saving initiatives to increase earnings, according to a confidential company document obtained by KHN and NPR.

This staffing strategy has permeated hospitals, and particularly emergency departments, that seek to reduce their top expense: physician labor. While diagnosing and treating patients was once their domain, doctors are increasingly being replaced by nurse practitioners and physician assistants, collectively known as “midlevel practitioners,” who can perform many of the same duties and generate much of the same revenue for less than half of the pay.

“APP has numerous cost saving initiatives underway as part of the Company’s continual focus on cost optimization,” the document says, including a “shift of staffing” between doctors and midlevel practitioners.

In a statement to KHN, American Physician Partners said this strategy is a way to ensure all EDs remain fully staffed, calling it a “blended model” that allows doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants “to provide care to their fullest potential.”

Critics of this strategy say the quest to save money results in treatment meted out by someone with far less training than a physician, leaving patients vulnerable to misdiagnoses, higher medical bills, and inadequate care. And these fears are bolstered by evidence that suggests dropping doctors from EDs may not be good for patients.

A working paper, published in October by the National Bureau of Economic Research, analyzed roughly 1.1 million visits to 44 EDs throughout the Veterans Health Administration, where nurse practitioners can treat patients without oversight from doctors.

Researchers found that treatment by a nurse practitioner resulted on average in a 7% increase in cost of care and an 11% increase in length of stay, extending patients’ time in the ED by minutes for minor visits and hours for longer ones. These gaps widened among patients with more severe diagnoses, the study said, but could be somewhat mitigated by nurse practitioners with more experience.

The study also found that ED patients treated by a nurse practitioner were 20% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital for a preventable reason within 30 days, although the overall risk of readmission remained very small.

Yiqun Chen, PhD, who is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago and coauthored the study, said these findings are not an indictment of nurse practitioners in the ED. Instead, she said, she hopes the study will guide how to best deploy nurse practitioners: in treatment of simpler patients or circumstances when no doctor is available.

“It’s not just a simple question of if we can substitute physicians with nurse practitioners or not,” Dr. Chen said. “It depends on how we use them. If we just use them as independent providers, especially ... for relatively complicated patients, it doesn’t seem to be a very good use.”

Dr. Chen’s research echoes smaller studies, like one from The Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute that found nonphysician practitioners in EDs were associated with a 5.3% increase in imaging, which could unnecessarily increase bills for patients. Separately, a study at the Hattiesburg Clinic in Mississippi found that midlevel practitioners in primary care – not in the emergency department – increased the out-of-pocket costs to patients while also leading to worse performance on 9 of 10 quality-of-care metrics, including cancer screenings and vaccination rates.

But definitive evidence remains elusive that replacing ER doctors with nonphysicians has a negative impact on patients, said Cameron Gettel, MD, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Private equity investment and the use of midlevel practitioners rose in lockstep in the ED, Dr. Gettel said, and in the absence of game-changing research, the pattern will likely continue.

“Worse patient outcomes haven’t really been shown across the board,” he said. “And I think until that is shown, then they will continue to play an increasing role.”

For private equity, dropping ED docs is a “simple equation”

Private equity companies pool money from wealthy investors to buy their way into various industries, often slashing spending and seeking to flip businesses in 3 to 7 years. While this business model is a proven moneymaker on Wall Street, it raises concerns in health care, where critics worry the pressure to turn big profits will influence life-or-death decisions that were once left solely to medical professionals.

Nearly $1 trillion in private equity funds have gone into almost 8,000 health care transactions over the past decade, according to industry tracker PitchBook, including buying into medical staffing companies that many hospitals hire to manage their emergency departments.

Two firms dominate the ED staffing industry: TeamHealth, bought by private equity firm Blackstone in 2016, and Envision Healthcare, bought by KKR in 2018. Trying to undercut these staffing giants is American Physician Partners, a rapidly expanding company that runs EDs in at least 17 states and is 50% owned by private equity firm BBH Capital Partners.

These staffing companies have been among the most aggressive in replacing doctors to cut costs, said Robert McNamara, MD, a founder of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and chair of emergency medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“It’s a relatively simple equation,” Dr. McNamara said. “Their No. 1 expense is the board-certified emergency physician. So they are going to want to keep that expense as low as possible.”

Not everyone sees the trend of private equity in ED staffing in a negative light. Jennifer Orozco, president of the American Academy of Physician Associates, which represents physician assistants, said even if the change – to use more nonphysician providers – is driven by the staffing firms’ desire to make more money, patients are still well served by a team approach that includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

“Though I see that shift, it’s not about profits at the end of the day,” Ms. Orozco said. “It’s about the patient.”

The “shift” is nearly invisible to patients because hospitals rarely promote branding from their ED staffing firms and there is little public documentation of private equity investments.

Arthur Smolensky, MD, a Tennessee emergency medicine specialist attempting to measure private equity’s intrusion into EDs, said his review of hospital job postings and employment contracts in 14 major metropolitan areas found that 43% of ED patients were seen in EDs staffed by companies with nonphysician owners, nearly all of whom are private equity investors.

Dr. Smolensky hopes to publish his full study, expanding to 55 metro areas, later this year. But this research will merely quantify what many doctors already know: The ED has changed. Demoralized by an increased focus on profit, and wary of a looming surplus of emergency medicine residents because there are fewer jobs to fill, many experienced doctors are leaving the ED on their own, he said.

“Most of us didn’t go into medicine to supervise an army of people that are not as well trained as we are,” Dr. Smolensky said. “We want to take care of patients.”

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER”

Joshua Allen, a nurse practitioner at a small Kentucky hospital, snaked a rubber hose through a rack of pork ribs to practice inserting a chest tube to fix a collapsed lung.

It was 2020, and American Physician Partners was restructuring the ED where Mr. Allen worked, reducing shifts from two doctors to one. Once Mr. Allen had placed 10 tubes under a doctor’s supervision, he would be allowed to do it on his own.

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER,” he said. “If we do have a major trauma and multiple victims come in, there’s only one doctor there. ... We need to be prepared.”

Mr. Allen is one of many midlevel practitioners finding work in emergency departments. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are among the fastest-growing occupations in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally, they have master’s degrees and receive several years of specialized schooling but have significantly less training than doctors. Many are permitted to diagnose patients and prescribe medication with little or no supervision from a doctor, although limitations vary by state.

The Neiman Institute found that the share of ED visits in which a midlevel practitioner was the main clinician increased by more than 172% between 2005 and 2020. Another study, in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, reported that if trends continue there may be equal numbers of midlevel practitioners and doctors in EDs by 2030.

There is little mystery as to why. Federal data shows emergency medicine doctors are paid about $310,000 a year on average, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants earn less than $120,000. Generally, hospitals can bill for care by a midlevel practitioner at 85% the rate of a doctor while paying them less than half as much.

Private equity can make millions in the gap.

For example, Envision once encouraged EDs to employ “the least expensive resource” and treat up to 35% of patients with midlevel practitioners, according to a 2017 PowerPoint presentation. The presentation drew scorn on social media and disappeared from Envision’s website.

Envision declined a request for a phone interview. In a written statement to KHN, spokesperson Aliese Polk said the company does not direct its physician leaders on how to care for patients and called the presentation a “concept guide” that does not represent current views.

American Physician Partners touted roughly the same staffing strategy in 2021 in response to the No Surprises Act, which threatened the company’s profits by outlawing surprise medical bills. In its confidential pitch to lenders, the company estimated it could cut almost $6 million by shifting more staffing from physicians to midlevel practitioners.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

She didn’t know much about miscarriage, but this seemed like one.

In the emergency department, she was examined then sent home, she said. She went back when her cramping became excruciating. Then home again. It ultimately took three trips to the ED on 3 consecutive days, generating three separate bills, before she saw a doctor who looked at her blood work and confirmed her fears.

“At the time I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I need to see a doctor,’ ” Ms. Valle recalled. “But when you think about it, it’s like, ‘Well, dang – why didn’t I see a doctor?’ ” It’s unclear whether the repeat visits were due to delays in seeing a physician, but the experience worried her. And she’s still paying the bills.

The hospital declined to discuss Ms. Valle’s care, citing patient privacy. But 17 months before her 3-day ordeal, Tennova had outsourced its emergency departments to American Physician Partners, a medical staffing company owned by private equity investors. APP employs fewer doctors in its EDs as one of its cost-saving initiatives to increase earnings, according to a confidential company document obtained by KHN and NPR.

This staffing strategy has permeated hospitals, and particularly emergency departments, that seek to reduce their top expense: physician labor. While diagnosing and treating patients was once their domain, doctors are increasingly being replaced by nurse practitioners and physician assistants, collectively known as “midlevel practitioners,” who can perform many of the same duties and generate much of the same revenue for less than half of the pay.

“APP has numerous cost saving initiatives underway as part of the Company’s continual focus on cost optimization,” the document says, including a “shift of staffing” between doctors and midlevel practitioners.

In a statement to KHN, American Physician Partners said this strategy is a way to ensure all EDs remain fully staffed, calling it a “blended model” that allows doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants “to provide care to their fullest potential.”

Critics of this strategy say the quest to save money results in treatment meted out by someone with far less training than a physician, leaving patients vulnerable to misdiagnoses, higher medical bills, and inadequate care. And these fears are bolstered by evidence that suggests dropping doctors from EDs may not be good for patients.

A working paper, published in October by the National Bureau of Economic Research, analyzed roughly 1.1 million visits to 44 EDs throughout the Veterans Health Administration, where nurse practitioners can treat patients without oversight from doctors.

Researchers found that treatment by a nurse practitioner resulted on average in a 7% increase in cost of care and an 11% increase in length of stay, extending patients’ time in the ED by minutes for minor visits and hours for longer ones. These gaps widened among patients with more severe diagnoses, the study said, but could be somewhat mitigated by nurse practitioners with more experience.

The study also found that ED patients treated by a nurse practitioner were 20% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital for a preventable reason within 30 days, although the overall risk of readmission remained very small.

Yiqun Chen, PhD, who is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago and coauthored the study, said these findings are not an indictment of nurse practitioners in the ED. Instead, she said, she hopes the study will guide how to best deploy nurse practitioners: in treatment of simpler patients or circumstances when no doctor is available.

“It’s not just a simple question of if we can substitute physicians with nurse practitioners or not,” Dr. Chen said. “It depends on how we use them. If we just use them as independent providers, especially ... for relatively complicated patients, it doesn’t seem to be a very good use.”

Dr. Chen’s research echoes smaller studies, like one from The Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute that found nonphysician practitioners in EDs were associated with a 5.3% increase in imaging, which could unnecessarily increase bills for patients. Separately, a study at the Hattiesburg Clinic in Mississippi found that midlevel practitioners in primary care – not in the emergency department – increased the out-of-pocket costs to patients while also leading to worse performance on 9 of 10 quality-of-care metrics, including cancer screenings and vaccination rates.

But definitive evidence remains elusive that replacing ER doctors with nonphysicians has a negative impact on patients, said Cameron Gettel, MD, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Private equity investment and the use of midlevel practitioners rose in lockstep in the ED, Dr. Gettel said, and in the absence of game-changing research, the pattern will likely continue.

“Worse patient outcomes haven’t really been shown across the board,” he said. “And I think until that is shown, then they will continue to play an increasing role.”

For private equity, dropping ED docs is a “simple equation”

Private equity companies pool money from wealthy investors to buy their way into various industries, often slashing spending and seeking to flip businesses in 3 to 7 years. While this business model is a proven moneymaker on Wall Street, it raises concerns in health care, where critics worry the pressure to turn big profits will influence life-or-death decisions that were once left solely to medical professionals.

Nearly $1 trillion in private equity funds have gone into almost 8,000 health care transactions over the past decade, according to industry tracker PitchBook, including buying into medical staffing companies that many hospitals hire to manage their emergency departments.

Two firms dominate the ED staffing industry: TeamHealth, bought by private equity firm Blackstone in 2016, and Envision Healthcare, bought by KKR in 2018. Trying to undercut these staffing giants is American Physician Partners, a rapidly expanding company that runs EDs in at least 17 states and is 50% owned by private equity firm BBH Capital Partners.

These staffing companies have been among the most aggressive in replacing doctors to cut costs, said Robert McNamara, MD, a founder of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and chair of emergency medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“It’s a relatively simple equation,” Dr. McNamara said. “Their No. 1 expense is the board-certified emergency physician. So they are going to want to keep that expense as low as possible.”

Not everyone sees the trend of private equity in ED staffing in a negative light. Jennifer Orozco, president of the American Academy of Physician Associates, which represents physician assistants, said even if the change – to use more nonphysician providers – is driven by the staffing firms’ desire to make more money, patients are still well served by a team approach that includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

“Though I see that shift, it’s not about profits at the end of the day,” Ms. Orozco said. “It’s about the patient.”

The “shift” is nearly invisible to patients because hospitals rarely promote branding from their ED staffing firms and there is little public documentation of private equity investments.

Arthur Smolensky, MD, a Tennessee emergency medicine specialist attempting to measure private equity’s intrusion into EDs, said his review of hospital job postings and employment contracts in 14 major metropolitan areas found that 43% of ED patients were seen in EDs staffed by companies with nonphysician owners, nearly all of whom are private equity investors.

Dr. Smolensky hopes to publish his full study, expanding to 55 metro areas, later this year. But this research will merely quantify what many doctors already know: The ED has changed. Demoralized by an increased focus on profit, and wary of a looming surplus of emergency medicine residents because there are fewer jobs to fill, many experienced doctors are leaving the ED on their own, he said.

“Most of us didn’t go into medicine to supervise an army of people that are not as well trained as we are,” Dr. Smolensky said. “We want to take care of patients.”

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER”

Joshua Allen, a nurse practitioner at a small Kentucky hospital, snaked a rubber hose through a rack of pork ribs to practice inserting a chest tube to fix a collapsed lung.

It was 2020, and American Physician Partners was restructuring the ED where Mr. Allen worked, reducing shifts from two doctors to one. Once Mr. Allen had placed 10 tubes under a doctor’s supervision, he would be allowed to do it on his own.

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER,” he said. “If we do have a major trauma and multiple victims come in, there’s only one doctor there. ... We need to be prepared.”

Mr. Allen is one of many midlevel practitioners finding work in emergency departments. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are among the fastest-growing occupations in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally, they have master’s degrees and receive several years of specialized schooling but have significantly less training than doctors. Many are permitted to diagnose patients and prescribe medication with little or no supervision from a doctor, although limitations vary by state.

The Neiman Institute found that the share of ED visits in which a midlevel practitioner was the main clinician increased by more than 172% between 2005 and 2020. Another study, in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, reported that if trends continue there may be equal numbers of midlevel practitioners and doctors in EDs by 2030.

There is little mystery as to why. Federal data shows emergency medicine doctors are paid about $310,000 a year on average, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants earn less than $120,000. Generally, hospitals can bill for care by a midlevel practitioner at 85% the rate of a doctor while paying them less than half as much.

Private equity can make millions in the gap.

For example, Envision once encouraged EDs to employ “the least expensive resource” and treat up to 35% of patients with midlevel practitioners, according to a 2017 PowerPoint presentation. The presentation drew scorn on social media and disappeared from Envision’s website.

Envision declined a request for a phone interview. In a written statement to KHN, spokesperson Aliese Polk said the company does not direct its physician leaders on how to care for patients and called the presentation a “concept guide” that does not represent current views.

American Physician Partners touted roughly the same staffing strategy in 2021 in response to the No Surprises Act, which threatened the company’s profits by outlawing surprise medical bills. In its confidential pitch to lenders, the company estimated it could cut almost $6 million by shifting more staffing from physicians to midlevel practitioners.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

She didn’t know much about miscarriage, but this seemed like one.

In the emergency department, she was examined then sent home, she said. She went back when her cramping became excruciating. Then home again. It ultimately took three trips to the ED on 3 consecutive days, generating three separate bills, before she saw a doctor who looked at her blood work and confirmed her fears.

“At the time I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I need to see a doctor,’ ” Ms. Valle recalled. “But when you think about it, it’s like, ‘Well, dang – why didn’t I see a doctor?’ ” It’s unclear whether the repeat visits were due to delays in seeing a physician, but the experience worried her. And she’s still paying the bills.

The hospital declined to discuss Ms. Valle’s care, citing patient privacy. But 17 months before her 3-day ordeal, Tennova had outsourced its emergency departments to American Physician Partners, a medical staffing company owned by private equity investors. APP employs fewer doctors in its EDs as one of its cost-saving initiatives to increase earnings, according to a confidential company document obtained by KHN and NPR.

This staffing strategy has permeated hospitals, and particularly emergency departments, that seek to reduce their top expense: physician labor. While diagnosing and treating patients was once their domain, doctors are increasingly being replaced by nurse practitioners and physician assistants, collectively known as “midlevel practitioners,” who can perform many of the same duties and generate much of the same revenue for less than half of the pay.

“APP has numerous cost saving initiatives underway as part of the Company’s continual focus on cost optimization,” the document says, including a “shift of staffing” between doctors and midlevel practitioners.

In a statement to KHN, American Physician Partners said this strategy is a way to ensure all EDs remain fully staffed, calling it a “blended model” that allows doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants “to provide care to their fullest potential.”

Critics of this strategy say the quest to save money results in treatment meted out by someone with far less training than a physician, leaving patients vulnerable to misdiagnoses, higher medical bills, and inadequate care. And these fears are bolstered by evidence that suggests dropping doctors from EDs may not be good for patients.

A working paper, published in October by the National Bureau of Economic Research, analyzed roughly 1.1 million visits to 44 EDs throughout the Veterans Health Administration, where nurse practitioners can treat patients without oversight from doctors.

Researchers found that treatment by a nurse practitioner resulted on average in a 7% increase in cost of care and an 11% increase in length of stay, extending patients’ time in the ED by minutes for minor visits and hours for longer ones. These gaps widened among patients with more severe diagnoses, the study said, but could be somewhat mitigated by nurse practitioners with more experience.

The study also found that ED patients treated by a nurse practitioner were 20% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital for a preventable reason within 30 days, although the overall risk of readmission remained very small.

Yiqun Chen, PhD, who is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago and coauthored the study, said these findings are not an indictment of nurse practitioners in the ED. Instead, she said, she hopes the study will guide how to best deploy nurse practitioners: in treatment of simpler patients or circumstances when no doctor is available.

“It’s not just a simple question of if we can substitute physicians with nurse practitioners or not,” Dr. Chen said. “It depends on how we use them. If we just use them as independent providers, especially ... for relatively complicated patients, it doesn’t seem to be a very good use.”

Dr. Chen’s research echoes smaller studies, like one from The Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute that found nonphysician practitioners in EDs were associated with a 5.3% increase in imaging, which could unnecessarily increase bills for patients. Separately, a study at the Hattiesburg Clinic in Mississippi found that midlevel practitioners in primary care – not in the emergency department – increased the out-of-pocket costs to patients while also leading to worse performance on 9 of 10 quality-of-care metrics, including cancer screenings and vaccination rates.

But definitive evidence remains elusive that replacing ER doctors with nonphysicians has a negative impact on patients, said Cameron Gettel, MD, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Private equity investment and the use of midlevel practitioners rose in lockstep in the ED, Dr. Gettel said, and in the absence of game-changing research, the pattern will likely continue.

“Worse patient outcomes haven’t really been shown across the board,” he said. “And I think until that is shown, then they will continue to play an increasing role.”

For private equity, dropping ED docs is a “simple equation”

Private equity companies pool money from wealthy investors to buy their way into various industries, often slashing spending and seeking to flip businesses in 3 to 7 years. While this business model is a proven moneymaker on Wall Street, it raises concerns in health care, where critics worry the pressure to turn big profits will influence life-or-death decisions that were once left solely to medical professionals.

Nearly $1 trillion in private equity funds have gone into almost 8,000 health care transactions over the past decade, according to industry tracker PitchBook, including buying into medical staffing companies that many hospitals hire to manage their emergency departments.

Two firms dominate the ED staffing industry: TeamHealth, bought by private equity firm Blackstone in 2016, and Envision Healthcare, bought by KKR in 2018. Trying to undercut these staffing giants is American Physician Partners, a rapidly expanding company that runs EDs in at least 17 states and is 50% owned by private equity firm BBH Capital Partners.

These staffing companies have been among the most aggressive in replacing doctors to cut costs, said Robert McNamara, MD, a founder of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and chair of emergency medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“It’s a relatively simple equation,” Dr. McNamara said. “Their No. 1 expense is the board-certified emergency physician. So they are going to want to keep that expense as low as possible.”

Not everyone sees the trend of private equity in ED staffing in a negative light. Jennifer Orozco, president of the American Academy of Physician Associates, which represents physician assistants, said even if the change – to use more nonphysician providers – is driven by the staffing firms’ desire to make more money, patients are still well served by a team approach that includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

“Though I see that shift, it’s not about profits at the end of the day,” Ms. Orozco said. “It’s about the patient.”

The “shift” is nearly invisible to patients because hospitals rarely promote branding from their ED staffing firms and there is little public documentation of private equity investments.

Arthur Smolensky, MD, a Tennessee emergency medicine specialist attempting to measure private equity’s intrusion into EDs, said his review of hospital job postings and employment contracts in 14 major metropolitan areas found that 43% of ED patients were seen in EDs staffed by companies with nonphysician owners, nearly all of whom are private equity investors.

Dr. Smolensky hopes to publish his full study, expanding to 55 metro areas, later this year. But this research will merely quantify what many doctors already know: The ED has changed. Demoralized by an increased focus on profit, and wary of a looming surplus of emergency medicine residents because there are fewer jobs to fill, many experienced doctors are leaving the ED on their own, he said.

“Most of us didn’t go into medicine to supervise an army of people that are not as well trained as we are,” Dr. Smolensky said. “We want to take care of patients.”

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER”

Joshua Allen, a nurse practitioner at a small Kentucky hospital, snaked a rubber hose through a rack of pork ribs to practice inserting a chest tube to fix a collapsed lung.

It was 2020, and American Physician Partners was restructuring the ED where Mr. Allen worked, reducing shifts from two doctors to one. Once Mr. Allen had placed 10 tubes under a doctor’s supervision, he would be allowed to do it on his own.

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER,” he said. “If we do have a major trauma and multiple victims come in, there’s only one doctor there. ... We need to be prepared.”

Mr. Allen is one of many midlevel practitioners finding work in emergency departments. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are among the fastest-growing occupations in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally, they have master’s degrees and receive several years of specialized schooling but have significantly less training than doctors. Many are permitted to diagnose patients and prescribe medication with little or no supervision from a doctor, although limitations vary by state.

The Neiman Institute found that the share of ED visits in which a midlevel practitioner was the main clinician increased by more than 172% between 2005 and 2020. Another study, in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, reported that if trends continue there may be equal numbers of midlevel practitioners and doctors in EDs by 2030.

There is little mystery as to why. Federal data shows emergency medicine doctors are paid about $310,000 a year on average, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants earn less than $120,000. Generally, hospitals can bill for care by a midlevel practitioner at 85% the rate of a doctor while paying them less than half as much.

Private equity can make millions in the gap.

For example, Envision once encouraged EDs to employ “the least expensive resource” and treat up to 35% of patients with midlevel practitioners, according to a 2017 PowerPoint presentation. The presentation drew scorn on social media and disappeared from Envision’s website.

Envision declined a request for a phone interview. In a written statement to KHN, spokesperson Aliese Polk said the company does not direct its physician leaders on how to care for patients and called the presentation a “concept guide” that does not represent current views.

American Physician Partners touted roughly the same staffing strategy in 2021 in response to the No Surprises Act, which threatened the company’s profits by outlawing surprise medical bills. In its confidential pitch to lenders, the company estimated it could cut almost $6 million by shifting more staffing from physicians to midlevel practitioners.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Thrombectomy benefits stroke with large core volumes: SELECT2 trial results

in a major international trial, which is expected to lead to a change in clinical practice and the way in which systems of stroke care are organized.

The results of the SELECT2 trial, which was conducted in sites in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, showed that endovascular thrombectomy plus medical care resulted in better clinical outcomes than medical care alone in patients with a large ischemic core who presented within 24 hours after the time they were last known to be well.

The results of the SELECT2 trial were presented at the International Stroke Conference by Amrou Sarraj, MD. Dr. Sarraj is professor of neurology at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center–Case Western Reserve University in Ohio. The study was also simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

A similar trial conducted in China, the ANGEL-ASPECT trial, was also presented at the same ISC session and showed very similar results.

These two trials add to another Japanese study reported last year, the RESCUE-JAPAN LIMIT trial, also showing benefit of thrombectomy in patients with large core strokes.

Dr. Sarraj concluded that the results of these three trials together “unequivocally demonstrate the benefit of endovascular thrombectomy in patients with large ischemic core.”

A clear benefit

Approximately 20% of large-vessel occlusion strokes have a large core, but these patients have not been considered candidates for endovascular thrombectomy because of concerns about potential reperfusion injury in necrotic brain tissue, resulting in an increased risk of hemorrhage, edema, disability, and death.

This has resulted in uncertainty about how to manage these patients with a core infarct, Dr. Sarraj noted at the conference presented by the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association.

The SELECT2 trial involved patients with stroke as a result of occlusion of the internal carotid artery or the first segment of the middle cerebral artery. Patients had a large ischemic core volume, defined as an ASPECTS (Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score) of 3-5, or a core volume of at least 50 mL on imaging. They were randomly assigned to endovascular thrombectomy plus medical care or to medical care alone.

The trial was aiming to enroll 560 patients but was stopped early for efficacy after 178 patients had been assigned to the thrombectomy group and 174 to the medical-care group.

The primary outcome – the generalized odds ratio for a shift in the distribution of modified Rankin scale scores toward better outcomes in favor of thrombectomy was 1.51 (P < .001).

“This translates into a 60% probability of achieving a better functional outcome in patients receiving thrombectomy, with a number needed to treat of five. That means five patients need to be treated with thrombectomy for one to achieve a better functional outcome,” Dr. Sarraj stated.

The secondary outcome of functional independence at 90 days (a score on the modified Rankin scale of 0-2) occurred in 20% of the patients in the thrombectomy group and 7% in the medical-care group (relative risk, 2.97), with a number needed to treat of seven.

Independent ambulation (a score on the modified Rankin Scale of 0-3) at 90 days occurred in 37.9% of the patients in the thrombectomy group and in 18.7% of the patients in the medical-care group (relative risk, 2.06), with a number needed to treat of five.

Mortality was similar in the two groups.

The results for other secondary outcomes were generally in the same direction as those of the primary analysis, with the possible exception of early neurologic improvement, the authors reported.

The incidence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was low in both trial groups, occurring in one patient in the thrombectomy group and two in the medical care group.

The investigators pointed out that previous studies have reported rates of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in patients with large ischemic core lesions that are higher than those in this trial. “Therefore, the low percentage of patients with symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage observed in both trial groups was unexpected.”

Approximately 20% of the patients in the thrombectomy group had complications associated with the procedure. In the thrombectomy group, arterial access-site complications occurred in 5 patients, dissection in 10, cerebral vessel perforation in 7, and transient vasospasm in 11.

Early neurologic worsening, defined as an increase of 4 or more points on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), occurred in 24.7% in the thrombectomy group and in 15.5% in the medical-care group (relative risk, 1.59).

In a post-hoc analysis, “from which no conclusions can be drawn,” the authors reported, early neurologic worsening was associated with worse functional outcomes at 90 days, and patients who had neurologic worsening had larger ischemic core lesions at baseline (median volume, 107 mL) versus 77 mL among patients without neurologic worsening.

They noted that a potential cause of deterioration in some of these patients was brain edema associated with reperfusion. However, they emphasize that overall, endovascular thrombectomy was associated with better outcomes than medical care alone.

“Two-thirds of patients had core infarct sizes more than 70 mL, and one-third of patients had core infarct sizes of more than 100 mL, but even in patients with large and very large core volumes, thrombectomy was superior to medical care alone,” Dr. Sarraj said.

This will ‘change practice’

In a comment, ISC 2023 chair Tudor Jovin, MD, Cooper Neurological Institute, Cherry Hill, N.J., said: “This trial shows that even patients with a large core infarct who we would not have treated with thrombectomy in the past, actually do benefit from this procedure. And the surprise is that the benefit is nearly to the same extent as that in patients with smaller core infarcts. That is going to change practice.”

Dr. Jovin said that these results should not only change the selection of patients for thrombectomy, but they should also change systems of care. “Because the systems of care now are based around excluding these patients with large infarcts. We won’t need to do that in future.”

He elaborated: “I think imaging has held us back to be honest. We can exclude hemorrhage with a plain CT scan. Then after this, the biggest piece of information we need from imaging is the size of the infarct. We were concerned that we might hurt the patient if the infarct was large. Outside hospitals had to do advanced imaging before deciding whether to transfer patients for thrombectomy. These are all sources of delays.

“I am very pleased to see these results, and I hope to see a much more simplified triage of patients that will be more liberal to patients with the large infarcts,” he added.

Also commenting, Joseph Broderick, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Neuroscience Institute at the University of Cincinnati, said the results were “robust and important.”

He said the results of the SELECT2 trial, along with the other two similar trials, “will change practice and extend endovascular therapy to more patients with severe strokes.”

But Dr. Broderick believes imaging will still be necessary to exclude patients with ASPECTS scores of 0-2, who were not included in these trials. “These are patients who have very large areas of clear hypodensity on the baseline image (brain already dying or dead). These patients do not benefit from reperfusion with lytic drugs or endovascular therapy,” he noted.

‘Welcome news’

In an editorial accompanying the print publication of the two new studies, Pierre Fayad, MD, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, points out that all three trials of thrombectomy in patients with large core infarct strokes “showed remarkably similar results” despite differences in design, patient selection, thrombolytic treatment and dose, geographic location, and imaging criteria.

“Together, the trials provide reassuring information from more than a thousand patients with large ischemic strokes in different medical systems that will probably lead to changes in patterns of care delivery.”

Dr. Fayad said it is reasonable to suggest that endovascular thrombectomy be offered to patients with large strokes if they arrive in a timely fashion at a center that is capable of performing the procedure, and if the patients have an ASPECTS value of 3-5 or an ischemic core volume of 50 mL or greater.

Higher rates of good outcomes may be anticipated if this treatment is performed, despite increased risks of symptomatic hemorrhage, edema, neurologic worsening, and hemicraniectomy, he noted.

“Patients and families should be made aware of the limitations of treatment and the anticipated residual neurologic deficits resulting from the large infarction. The improved chance of independent walking and the ability to perform other daily activities in patients with the most severe strokes is welcome news for patients and for the field of stroke treatment,” he concluded.

The SELECT2 trial was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Stryker Neurovascular to University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and the University of Texas McGovern Medical School.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in a major international trial, which is expected to lead to a change in clinical practice and the way in which systems of stroke care are organized.

The results of the SELECT2 trial, which was conducted in sites in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, showed that endovascular thrombectomy plus medical care resulted in better clinical outcomes than medical care alone in patients with a large ischemic core who presented within 24 hours after the time they were last known to be well.

The results of the SELECT2 trial were presented at the International Stroke Conference by Amrou Sarraj, MD. Dr. Sarraj is professor of neurology at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center–Case Western Reserve University in Ohio. The study was also simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

A similar trial conducted in China, the ANGEL-ASPECT trial, was also presented at the same ISC session and showed very similar results.

These two trials add to another Japanese study reported last year, the RESCUE-JAPAN LIMIT trial, also showing benefit of thrombectomy in patients with large core strokes.

Dr. Sarraj concluded that the results of these three trials together “unequivocally demonstrate the benefit of endovascular thrombectomy in patients with large ischemic core.”

A clear benefit

Approximately 20% of large-vessel occlusion strokes have a large core, but these patients have not been considered candidates for endovascular thrombectomy because of concerns about potential reperfusion injury in necrotic brain tissue, resulting in an increased risk of hemorrhage, edema, disability, and death.

This has resulted in uncertainty about how to manage these patients with a core infarct, Dr. Sarraj noted at the conference presented by the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association.

The SELECT2 trial involved patients with stroke as a result of occlusion of the internal carotid artery or the first segment of the middle cerebral artery. Patients had a large ischemic core volume, defined as an ASPECTS (Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score) of 3-5, or a core volume of at least 50 mL on imaging. They were randomly assigned to endovascular thrombectomy plus medical care or to medical care alone.

The trial was aiming to enroll 560 patients but was stopped early for efficacy after 178 patients had been assigned to the thrombectomy group and 174 to the medical-care group.

The primary outcome – the generalized odds ratio for a shift in the distribution of modified Rankin scale scores toward better outcomes in favor of thrombectomy was 1.51 (P < .001).

“This translates into a 60% probability of achieving a better functional outcome in patients receiving thrombectomy, with a number needed to treat of five. That means five patients need to be treated with thrombectomy for one to achieve a better functional outcome,” Dr. Sarraj stated.

The secondary outcome of functional independence at 90 days (a score on the modified Rankin scale of 0-2) occurred in 20% of the patients in the thrombectomy group and 7% in the medical-care group (relative risk, 2.97), with a number needed to treat of seven.

Independent ambulation (a score on the modified Rankin Scale of 0-3) at 90 days occurred in 37.9% of the patients in the thrombectomy group and in 18.7% of the patients in the medical-care group (relative risk, 2.06), with a number needed to treat of five.

Mortality was similar in the two groups.

The results for other secondary outcomes were generally in the same direction as those of the primary analysis, with the possible exception of early neurologic improvement, the authors reported.

The incidence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was low in both trial groups, occurring in one patient in the thrombectomy group and two in the medical care group.

The investigators pointed out that previous studies have reported rates of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in patients with large ischemic core lesions that are higher than those in this trial. “Therefore, the low percentage of patients with symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage observed in both trial groups was unexpected.”