User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

FDA OKs new drug for Fabry disease

Fabry disease is a rare inherited X-linked lysosomal disorder caused by a deficiency of the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (GLA), which leads to the buildup of globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) in blood vessels, kidneys, the heart, nerves, and other organs, increasing the risk for kidney failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and other problems.

Elfabrio delivers a functional version of GLA. It’s given by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks.

Evidence for safety, tolerability, and efficacy of Elfabrio stems from a comprehensive clinical program in more than 140 patients with up to 7.5 years of follow up treatment.

It has been studied in both ERT-naïve and ERT-experienced patients. In one head-to-head trial, Elfabrio was non-inferior in safety and efficacy to agalsidase beta (Fabrazyme, Sanofi Genzyme), the companies said in a press statement announcing approval.

“The totality of clinical data suggests that Elfabrio has the potential to be a long-lasting therapy,” Dror Bashan, president and CEO of Protalix, said in the statement.

Patients treated with Elfabrio have experienced hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis. In clinical trials, 20 (14%) patients treated with Elfabrio experienced hypersensitivity reactions; 4 patients (3%) experienced anaphylaxis reactions that occurred within 5-40 minutes of the start of the initial infusion.

Before administering Elfabrio, pretreatment with antihistamines, antipyretics, and/or corticosteroids should be considered, the label advises.

Patients and caregivers should be informed of the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions and infusion-associated reactions and instructed to seek medical care immediately if such symptoms occur.

A case of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with immune depositions in the kidney was reported during clinical trials. Monitoring serum creatinine and urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio is advised. If glomerulonephritis is suspected, treatment should be stopped until a diagnostic evaluation can be conducted.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fabry disease is a rare inherited X-linked lysosomal disorder caused by a deficiency of the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (GLA), which leads to the buildup of globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) in blood vessels, kidneys, the heart, nerves, and other organs, increasing the risk for kidney failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and other problems.

Elfabrio delivers a functional version of GLA. It’s given by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks.

Evidence for safety, tolerability, and efficacy of Elfabrio stems from a comprehensive clinical program in more than 140 patients with up to 7.5 years of follow up treatment.

It has been studied in both ERT-naïve and ERT-experienced patients. In one head-to-head trial, Elfabrio was non-inferior in safety and efficacy to agalsidase beta (Fabrazyme, Sanofi Genzyme), the companies said in a press statement announcing approval.

“The totality of clinical data suggests that Elfabrio has the potential to be a long-lasting therapy,” Dror Bashan, president and CEO of Protalix, said in the statement.

Patients treated with Elfabrio have experienced hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis. In clinical trials, 20 (14%) patients treated with Elfabrio experienced hypersensitivity reactions; 4 patients (3%) experienced anaphylaxis reactions that occurred within 5-40 minutes of the start of the initial infusion.

Before administering Elfabrio, pretreatment with antihistamines, antipyretics, and/or corticosteroids should be considered, the label advises.

Patients and caregivers should be informed of the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions and infusion-associated reactions and instructed to seek medical care immediately if such symptoms occur.

A case of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with immune depositions in the kidney was reported during clinical trials. Monitoring serum creatinine and urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio is advised. If glomerulonephritis is suspected, treatment should be stopped until a diagnostic evaluation can be conducted.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fabry disease is a rare inherited X-linked lysosomal disorder caused by a deficiency of the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (GLA), which leads to the buildup of globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) in blood vessels, kidneys, the heart, nerves, and other organs, increasing the risk for kidney failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and other problems.

Elfabrio delivers a functional version of GLA. It’s given by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks.

Evidence for safety, tolerability, and efficacy of Elfabrio stems from a comprehensive clinical program in more than 140 patients with up to 7.5 years of follow up treatment.

It has been studied in both ERT-naïve and ERT-experienced patients. In one head-to-head trial, Elfabrio was non-inferior in safety and efficacy to agalsidase beta (Fabrazyme, Sanofi Genzyme), the companies said in a press statement announcing approval.

“The totality of clinical data suggests that Elfabrio has the potential to be a long-lasting therapy,” Dror Bashan, president and CEO of Protalix, said in the statement.

Patients treated with Elfabrio have experienced hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis. In clinical trials, 20 (14%) patients treated with Elfabrio experienced hypersensitivity reactions; 4 patients (3%) experienced anaphylaxis reactions that occurred within 5-40 minutes of the start of the initial infusion.

Before administering Elfabrio, pretreatment with antihistamines, antipyretics, and/or corticosteroids should be considered, the label advises.

Patients and caregivers should be informed of the signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions and infusion-associated reactions and instructed to seek medical care immediately if such symptoms occur.

A case of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with immune depositions in the kidney was reported during clinical trials. Monitoring serum creatinine and urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio is advised. If glomerulonephritis is suspected, treatment should be stopped until a diagnostic evaluation can be conducted.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves first drug to treat Alzheimer’s agitation

(AD), making it the first FDA-approved drug for this indication.

“Agitation is one of the most common and challenging aspects of care among patients with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease,” Tiffany Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

Agitation can include symptoms that range from pacing or restlessness to verbal and physical aggression. “These symptoms are leading causes of assisted living or nursing home placement and have been associated with accelerated disease progression,” Dr. Farchione said.

Brexpiprazole was approved by the FDA in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for adults with major depressive disorder and for adults with schizophrenia.

Approval of the supplemental application for brexpiprazole for agitation associated with AD dementia was based on results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.

In both studies, patients who received 2 mg or 3 mg of brexpiprazole showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in agitation symptoms, as shown by total Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) score, compared with patients who received placebo.

The recommended starting dosage for the treatment of agitation associated with AD dementia is 0.5 mg once daily on days 1-7; it was increased to 1 mg once daily on days 8-14 and then to the recommended target dose of 2 mg once daily.

The dosage can be increased to the maximum recommended daily dosage of 3 mg once daily after at least 14 days, depending on clinical response and tolerability.

The most common side effects of brexpiprazole in patients with agitation associated with AD dementia include headache, dizziness, urinary tract infection, nasopharyngitis, and sleep disturbances.

The drug includes a boxed warning for medications in this class that elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.

The supplemental application for brexpiprazole for agitation had fast-track designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(AD), making it the first FDA-approved drug for this indication.

“Agitation is one of the most common and challenging aspects of care among patients with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease,” Tiffany Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

Agitation can include symptoms that range from pacing or restlessness to verbal and physical aggression. “These symptoms are leading causes of assisted living or nursing home placement and have been associated with accelerated disease progression,” Dr. Farchione said.

Brexpiprazole was approved by the FDA in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for adults with major depressive disorder and for adults with schizophrenia.

Approval of the supplemental application for brexpiprazole for agitation associated with AD dementia was based on results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.

In both studies, patients who received 2 mg or 3 mg of brexpiprazole showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in agitation symptoms, as shown by total Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) score, compared with patients who received placebo.

The recommended starting dosage for the treatment of agitation associated with AD dementia is 0.5 mg once daily on days 1-7; it was increased to 1 mg once daily on days 8-14 and then to the recommended target dose of 2 mg once daily.

The dosage can be increased to the maximum recommended daily dosage of 3 mg once daily after at least 14 days, depending on clinical response and tolerability.

The most common side effects of brexpiprazole in patients with agitation associated with AD dementia include headache, dizziness, urinary tract infection, nasopharyngitis, and sleep disturbances.

The drug includes a boxed warning for medications in this class that elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.

The supplemental application for brexpiprazole for agitation had fast-track designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(AD), making it the first FDA-approved drug for this indication.

“Agitation is one of the most common and challenging aspects of care among patients with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease,” Tiffany Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release.

Agitation can include symptoms that range from pacing or restlessness to verbal and physical aggression. “These symptoms are leading causes of assisted living or nursing home placement and have been associated with accelerated disease progression,” Dr. Farchione said.

Brexpiprazole was approved by the FDA in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for adults with major depressive disorder and for adults with schizophrenia.

Approval of the supplemental application for brexpiprazole for agitation associated with AD dementia was based on results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.

In both studies, patients who received 2 mg or 3 mg of brexpiprazole showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in agitation symptoms, as shown by total Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) score, compared with patients who received placebo.

The recommended starting dosage for the treatment of agitation associated with AD dementia is 0.5 mg once daily on days 1-7; it was increased to 1 mg once daily on days 8-14 and then to the recommended target dose of 2 mg once daily.

The dosage can be increased to the maximum recommended daily dosage of 3 mg once daily after at least 14 days, depending on clinical response and tolerability.

The most common side effects of brexpiprazole in patients with agitation associated with AD dementia include headache, dizziness, urinary tract infection, nasopharyngitis, and sleep disturbances.

The drug includes a boxed warning for medications in this class that elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.

The supplemental application for brexpiprazole for agitation had fast-track designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical students gain momentum in effort to ban legacy admissions

, which they say offer preferential treatment to applicants based on their association with donors or alumni.

While an estimated 25% of public colleges and universities still use legacy admissions, a growing list of top medical schools have moved away from the practice over the last decade, including Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Tufts University, Medford, Mass.

Legacy admissions contradict schools’ more inclusive policies, Senila Yasmin, MPH, a second-year medical student at Tufts University, said in an interview. While Tufts maintains legacy admissions for its undergraduate applicants, the medical school stopped the practice in 2021, said Ms. Yasmin, a member of a student group that lobbied against the school’s legacy preferences.

Describing herself as a low-income, first-generation Muslim-Pakistani American, Ms. Yasmin wants to use her experience at Tufts to improve accessibility for students like herself.

As a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) Medical Student Section, she coauthored a resolution stating that legacy admissions go against the AMA’s strategic plan to advance racial justice and health equity. The Student Section passed the resolution in November, and in June, the AMA House of Delegates will vote on whether to adopt the policy.

Along with a Supreme Court decision that could strike down race-conscious college admissions, an AMA policy could convince medical schools to rethink legacy admissions and how to maintain diverse student bodies. In June, the court is expected to issue a decision in the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit against Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, which alleges that considering race in holistic admissions constitutes racial discrimination and violates the Equal Protection Clause.

Opponents of legacy admissions, like Ms. Yasmin, say it penalizes students from racial minorities and lower socioeconomic backgrounds, hampering a fair and equitable admissions process that attracts diverse medical school admissions.

Diversity of medical applicants

Diversity in medical schools continued to increase last year with more Black, Hispanic, and female students applying and enrolling, according to a recent report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). However, universities often include nonacademic criteria in their admission assessments to improve educational access for underrepresented minorities.

Medical schools carefully consider each applicant’s background “to yield a diverse class of students,” Geoffrey Young, PhD, AAMC’s senior director of transforming the health care workforce, told this news organization.

Some schools, such as Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, perform a thorough review of candidates while offering admissions practices designed specifically for legacy applicants. The schools assert that legacy designation doesn’t factor into the student’s likelihood of acceptance.

The arrangement may show that schools want to commit to equity and fairness but have trouble moving away from entrenched traditions, two professors from Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pa., who sit on separate medical admissions subcommittees, wrote last year in Bioethics Today.

Legislation may hasten legacies’ end

In December, Ms. Yasmin and a group of Massachusetts Medical Society student-members presented another resolution to the state medical society, which adopted it.

The society’s new policy opposes the use of legacy status in medical school admissions and supports mechanisms to eliminate its inclusion from the application process, Theodore Calianos II, MD, FACS, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, said in an interview.

“Legacy preferences limit racial and socioeconomic diversity on campuses, so we asked, ‘What can we do so that everyone has equal access to medical education?’ It is exciting to see the students and young physicians – the future of medicine – become involved in policymaking.”

Proposed laws may also hasten the end of legacy admissions. Last year, the U.S. Senate began considering a bill prohibiting colleges receiving federal financial aid from giving preferential treatment to students based on their relations to donors or alumni. However, the bill allows the Department of Education to make exceptions for institutions serving historically underrepresented groups.

The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly also are reviewing bills that ban legacy and early admissions policies at public and private universities. Connecticut announced similar legislation last year. Massachusetts legislators are considering two bills: one that would ban the practice at the state’s public universities and another that would require all schools using legacy status to pay a “public service fee” equal to a percentage of its endowment. Colleges with endowment assets exceeding $2 billion must pay at least $2 million, according to the bill’s text.

At schools like Harvard, whose endowment surpasses $50 billion, the option to pay the penalty will make the law moot, Michael Walls, DO, MPH, president of the American Medical Student Association (AMSA), said in an interview. “Smaller schools wouldn’t be able to afford the fine and are less likely to be doing [legacy admissions] anyway,” he said. “The schools that want to continue doing it could just pay the fine.”

Dr. Walls said AMSA supports race-conscious admissions processes and anything that increases fairness for medical school applicants. “Whatever [fair] means is up for interpretation, but it would be great to eliminate legacy admissions,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, which they say offer preferential treatment to applicants based on their association with donors or alumni.

While an estimated 25% of public colleges and universities still use legacy admissions, a growing list of top medical schools have moved away from the practice over the last decade, including Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Tufts University, Medford, Mass.

Legacy admissions contradict schools’ more inclusive policies, Senila Yasmin, MPH, a second-year medical student at Tufts University, said in an interview. While Tufts maintains legacy admissions for its undergraduate applicants, the medical school stopped the practice in 2021, said Ms. Yasmin, a member of a student group that lobbied against the school’s legacy preferences.

Describing herself as a low-income, first-generation Muslim-Pakistani American, Ms. Yasmin wants to use her experience at Tufts to improve accessibility for students like herself.

As a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) Medical Student Section, she coauthored a resolution stating that legacy admissions go against the AMA’s strategic plan to advance racial justice and health equity. The Student Section passed the resolution in November, and in June, the AMA House of Delegates will vote on whether to adopt the policy.

Along with a Supreme Court decision that could strike down race-conscious college admissions, an AMA policy could convince medical schools to rethink legacy admissions and how to maintain diverse student bodies. In June, the court is expected to issue a decision in the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit against Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, which alleges that considering race in holistic admissions constitutes racial discrimination and violates the Equal Protection Clause.

Opponents of legacy admissions, like Ms. Yasmin, say it penalizes students from racial minorities and lower socioeconomic backgrounds, hampering a fair and equitable admissions process that attracts diverse medical school admissions.

Diversity of medical applicants

Diversity in medical schools continued to increase last year with more Black, Hispanic, and female students applying and enrolling, according to a recent report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). However, universities often include nonacademic criteria in their admission assessments to improve educational access for underrepresented minorities.

Medical schools carefully consider each applicant’s background “to yield a diverse class of students,” Geoffrey Young, PhD, AAMC’s senior director of transforming the health care workforce, told this news organization.

Some schools, such as Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, perform a thorough review of candidates while offering admissions practices designed specifically for legacy applicants. The schools assert that legacy designation doesn’t factor into the student’s likelihood of acceptance.

The arrangement may show that schools want to commit to equity and fairness but have trouble moving away from entrenched traditions, two professors from Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pa., who sit on separate medical admissions subcommittees, wrote last year in Bioethics Today.

Legislation may hasten legacies’ end

In December, Ms. Yasmin and a group of Massachusetts Medical Society student-members presented another resolution to the state medical society, which adopted it.

The society’s new policy opposes the use of legacy status in medical school admissions and supports mechanisms to eliminate its inclusion from the application process, Theodore Calianos II, MD, FACS, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, said in an interview.

“Legacy preferences limit racial and socioeconomic diversity on campuses, so we asked, ‘What can we do so that everyone has equal access to medical education?’ It is exciting to see the students and young physicians – the future of medicine – become involved in policymaking.”

Proposed laws may also hasten the end of legacy admissions. Last year, the U.S. Senate began considering a bill prohibiting colleges receiving federal financial aid from giving preferential treatment to students based on their relations to donors or alumni. However, the bill allows the Department of Education to make exceptions for institutions serving historically underrepresented groups.

The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly also are reviewing bills that ban legacy and early admissions policies at public and private universities. Connecticut announced similar legislation last year. Massachusetts legislators are considering two bills: one that would ban the practice at the state’s public universities and another that would require all schools using legacy status to pay a “public service fee” equal to a percentage of its endowment. Colleges with endowment assets exceeding $2 billion must pay at least $2 million, according to the bill’s text.

At schools like Harvard, whose endowment surpasses $50 billion, the option to pay the penalty will make the law moot, Michael Walls, DO, MPH, president of the American Medical Student Association (AMSA), said in an interview. “Smaller schools wouldn’t be able to afford the fine and are less likely to be doing [legacy admissions] anyway,” he said. “The schools that want to continue doing it could just pay the fine.”

Dr. Walls said AMSA supports race-conscious admissions processes and anything that increases fairness for medical school applicants. “Whatever [fair] means is up for interpretation, but it would be great to eliminate legacy admissions,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, which they say offer preferential treatment to applicants based on their association with donors or alumni.

While an estimated 25% of public colleges and universities still use legacy admissions, a growing list of top medical schools have moved away from the practice over the last decade, including Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Tufts University, Medford, Mass.

Legacy admissions contradict schools’ more inclusive policies, Senila Yasmin, MPH, a second-year medical student at Tufts University, said in an interview. While Tufts maintains legacy admissions for its undergraduate applicants, the medical school stopped the practice in 2021, said Ms. Yasmin, a member of a student group that lobbied against the school’s legacy preferences.

Describing herself as a low-income, first-generation Muslim-Pakistani American, Ms. Yasmin wants to use her experience at Tufts to improve accessibility for students like herself.

As a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) Medical Student Section, she coauthored a resolution stating that legacy admissions go against the AMA’s strategic plan to advance racial justice and health equity. The Student Section passed the resolution in November, and in June, the AMA House of Delegates will vote on whether to adopt the policy.

Along with a Supreme Court decision that could strike down race-conscious college admissions, an AMA policy could convince medical schools to rethink legacy admissions and how to maintain diverse student bodies. In June, the court is expected to issue a decision in the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit against Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, which alleges that considering race in holistic admissions constitutes racial discrimination and violates the Equal Protection Clause.

Opponents of legacy admissions, like Ms. Yasmin, say it penalizes students from racial minorities and lower socioeconomic backgrounds, hampering a fair and equitable admissions process that attracts diverse medical school admissions.

Diversity of medical applicants

Diversity in medical schools continued to increase last year with more Black, Hispanic, and female students applying and enrolling, according to a recent report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). However, universities often include nonacademic criteria in their admission assessments to improve educational access for underrepresented minorities.

Medical schools carefully consider each applicant’s background “to yield a diverse class of students,” Geoffrey Young, PhD, AAMC’s senior director of transforming the health care workforce, told this news organization.

Some schools, such as Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, perform a thorough review of candidates while offering admissions practices designed specifically for legacy applicants. The schools assert that legacy designation doesn’t factor into the student’s likelihood of acceptance.

The arrangement may show that schools want to commit to equity and fairness but have trouble moving away from entrenched traditions, two professors from Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pa., who sit on separate medical admissions subcommittees, wrote last year in Bioethics Today.

Legislation may hasten legacies’ end

In December, Ms. Yasmin and a group of Massachusetts Medical Society student-members presented another resolution to the state medical society, which adopted it.

The society’s new policy opposes the use of legacy status in medical school admissions and supports mechanisms to eliminate its inclusion from the application process, Theodore Calianos II, MD, FACS, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, said in an interview.

“Legacy preferences limit racial and socioeconomic diversity on campuses, so we asked, ‘What can we do so that everyone has equal access to medical education?’ It is exciting to see the students and young physicians – the future of medicine – become involved in policymaking.”

Proposed laws may also hasten the end of legacy admissions. Last year, the U.S. Senate began considering a bill prohibiting colleges receiving federal financial aid from giving preferential treatment to students based on their relations to donors or alumni. However, the bill allows the Department of Education to make exceptions for institutions serving historically underrepresented groups.

The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly also are reviewing bills that ban legacy and early admissions policies at public and private universities. Connecticut announced similar legislation last year. Massachusetts legislators are considering two bills: one that would ban the practice at the state’s public universities and another that would require all schools using legacy status to pay a “public service fee” equal to a percentage of its endowment. Colleges with endowment assets exceeding $2 billion must pay at least $2 million, according to the bill’s text.

At schools like Harvard, whose endowment surpasses $50 billion, the option to pay the penalty will make the law moot, Michael Walls, DO, MPH, president of the American Medical Student Association (AMSA), said in an interview. “Smaller schools wouldn’t be able to afford the fine and are less likely to be doing [legacy admissions] anyway,” he said. “The schools that want to continue doing it could just pay the fine.”

Dr. Walls said AMSA supports race-conscious admissions processes and anything that increases fairness for medical school applicants. “Whatever [fair] means is up for interpretation, but it would be great to eliminate legacy admissions,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Five ways docs may qualify for discounts on medical malpractice premiums

Getting a better deal might simply mean taking advantage of incentives and discounts your insurer may already offer. These include claims-free, new-to-practice, and working part-time discounts.

However, if you decide to shop around, keep in mind that discounts are just one factor that can affect your premium price – insurers look at your specialty, location, and claims history.

One of the most common ways physicians can earn discounts is by participating in risk management programs. With this type of program, physicians evaluate elements of their practice and documentation practices and identify areas that might leave them at risk for a lawsuit. While they save money, physician risk management programs also are designed to reduce malpractice claims, which ultimately minimizes the potential for bigger financial losses, insurance experts say.

“It’s a win-win situation when liability insurers and physicians work together to minimize risk, and it’s a win for patients,” said Gary Price, MD, president of The Physicians Foundation.

Doctors in private practice or employed by small hospitals that are not self-insured can qualify for these discounts, said David Zetter, president of Zetter HealthCare Management Consultants.

“I do a lot of work with medical malpractice companies trying to find clients policies. All the carriers are transparent about what physicians have to do to lower their premiums. Physicians can receive the discounts if they follow through and meet the insurer’s requirements,” said Mr. Zetter.

State insurance departments regulate medical malpractice insurance, including the premium credits insurers offer. Most states cap discounts at 25%, but some go as high as 70%, according to The Doctors Company, a national physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.

Insurers typically offer doctors several ways to earn discounts. The size of the discount also can depend on whether a doctor is new to a practice, remains claims free, or takes risk management courses.

In addition to the premium discount, some online risk management classes and webinars are eligible for CME credits.

“The credits can add up and they can be used for recertification or relicensure,” said Susan Boisvert, senior patient safety risk manager at The Doctors Company.

Here are five ways you may qualify for discounts with your insurer.

1. Make use of discounts available to new doctors

Doctors can earn hefty discounts on their premiums when they are no longer interns or residents and start practicing medicine. The Doctors Company usually gives a 50% discount on member premiums the first year they’re in practice and a 25% discount credit in their second year. The discounts end after that.

Other insurance carriers offer similar discounts to doctors starting to practice medicine. The deepest one is offered in the first year (at least 50%) and a smaller one (20%-25%) the second year, according to medical malpractice brokers.

“The new-to-practice discount is based solely on when the physician left their formal training to begin their practice for the first time; it is not based on claim-free history,” explained Mr. Zetter.

This is a very common discount used by different insurer carriers, said Dr. Price. “New physicians don’t have the same amount of risk of a lawsuit when they’re starting out. It’s unlikely they will have a claim and most liability actions have a 2-year time limit from the date of injury to be filed.”

2. Take advantage of being claims free

If you’ve been claims free for at least a few years, you may be eligible for a large discount.

“Doctors without claims are a better risk. Once a doctor has one claim, they’re likely to have a second, which the research shows,” said Mr. Zetter.

The most common credit The Doctors Company offers is 3 years of being claim free – this earns doctors up to 25%, he said. Mr. Zetter explained that the criteria and size of The Doctors Company credit may depend on the state where physicians practice.

“We allowed insurance carriers that we acquired to continue with their own claim-free discount program such as Florida’s First Professionals Insurance Company we acquired in 2011,” he said.

Doctors with other medical malpractice insurers may also be eligible for a credit up to 25%. In some instances, they may have to be claims free for 5 or 10 years, say insurance experts.

It pays to shop around before purchasing insurance.

3. If you work part time, make sure your premium reflects that

Physicians who see patients part time can receive up to a 75% discount on their medical liability insurance premiums.

The discounts are based on the hours the physician works per week. The fewer hours worked, the larger the discount. This type of discount does not vary by specialty.

According to The Doctors Company, working 10 hours or less per week may entitle doctors to a 75% discount; working 11-20 hours per week may entitle them to a 50% discount, and working 21-30 hours per week may entitle them to a 25% discount. If you are in this situation, it pays to ask your insurer if there is a discount available to you.

4. Look into your professional medical society insurance company

“I would look at your state medical association [or] state specialty society and talk to your colleagues to learn what premiums they’re paying and about any discounts they’re getting,” advised Mr. Zetter.

Some state medical societies have formed their own liability companies and offer lower premiums to their members because “they’re organized and managed by doctors, which makes their premiums more competitive,” Dr. Price said.

Other state medical societies endorse specific insurance carriers and offer their members a 5% discount for enrolling with them.

5. Enroll in a risk management program

Most insurers offer online educational activities designed to improve patient safety and reduce the risk of a lawsuit. Physicians may be eligible for both premium discounts and CME credits.

Medical Liability Mutual Insurance Company, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, operates in New York and offers physicians a premium discount of up to 5%, CME credit, and maintenance of certification credit for successfully completing its risk management program every other year.

ProAssurance members nationwide can earn 5% in premium discounts if they complete a 2-hour video series called “Back to Basics: Loss Prevention and Navigating Everyday Risks: Using Data to Drive Change.”

They can earn one credit for completing each webinar on topics such as “Medication Management: Minimizing Errors and Improving Safety” and “Opioid Prescribing: Keeping Patients Safe.”

MagMutual offers its insured physicians 1 CME credit for completing their specialty’s risk assessment and courses, which may be applied toward their premium discounts.

The Doctors Company offers its members a 5% premium discount if they complete 4 CME credits. One of its most popular courses is “How To Get Rid of a Difficult Patient.”

“Busy residents like the shorter case studies worth one-quarter credit that they can complete in 15 minutes,” said Ms. Boisvert.

“This is a good bargain from the physician’s standpoint and the fact that risk management education is offered online makes it a lot easier than going to a seminar in person,” said Dr. Price.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Getting a better deal might simply mean taking advantage of incentives and discounts your insurer may already offer. These include claims-free, new-to-practice, and working part-time discounts.

However, if you decide to shop around, keep in mind that discounts are just one factor that can affect your premium price – insurers look at your specialty, location, and claims history.

One of the most common ways physicians can earn discounts is by participating in risk management programs. With this type of program, physicians evaluate elements of their practice and documentation practices and identify areas that might leave them at risk for a lawsuit. While they save money, physician risk management programs also are designed to reduce malpractice claims, which ultimately minimizes the potential for bigger financial losses, insurance experts say.

“It’s a win-win situation when liability insurers and physicians work together to minimize risk, and it’s a win for patients,” said Gary Price, MD, president of The Physicians Foundation.

Doctors in private practice or employed by small hospitals that are not self-insured can qualify for these discounts, said David Zetter, president of Zetter HealthCare Management Consultants.

“I do a lot of work with medical malpractice companies trying to find clients policies. All the carriers are transparent about what physicians have to do to lower their premiums. Physicians can receive the discounts if they follow through and meet the insurer’s requirements,” said Mr. Zetter.

State insurance departments regulate medical malpractice insurance, including the premium credits insurers offer. Most states cap discounts at 25%, but some go as high as 70%, according to The Doctors Company, a national physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.

Insurers typically offer doctors several ways to earn discounts. The size of the discount also can depend on whether a doctor is new to a practice, remains claims free, or takes risk management courses.

In addition to the premium discount, some online risk management classes and webinars are eligible for CME credits.

“The credits can add up and they can be used for recertification or relicensure,” said Susan Boisvert, senior patient safety risk manager at The Doctors Company.

Here are five ways you may qualify for discounts with your insurer.

1. Make use of discounts available to new doctors

Doctors can earn hefty discounts on their premiums when they are no longer interns or residents and start practicing medicine. The Doctors Company usually gives a 50% discount on member premiums the first year they’re in practice and a 25% discount credit in their second year. The discounts end after that.

Other insurance carriers offer similar discounts to doctors starting to practice medicine. The deepest one is offered in the first year (at least 50%) and a smaller one (20%-25%) the second year, according to medical malpractice brokers.

“The new-to-practice discount is based solely on when the physician left their formal training to begin their practice for the first time; it is not based on claim-free history,” explained Mr. Zetter.

This is a very common discount used by different insurer carriers, said Dr. Price. “New physicians don’t have the same amount of risk of a lawsuit when they’re starting out. It’s unlikely they will have a claim and most liability actions have a 2-year time limit from the date of injury to be filed.”

2. Take advantage of being claims free

If you’ve been claims free for at least a few years, you may be eligible for a large discount.

“Doctors without claims are a better risk. Once a doctor has one claim, they’re likely to have a second, which the research shows,” said Mr. Zetter.

The most common credit The Doctors Company offers is 3 years of being claim free – this earns doctors up to 25%, he said. Mr. Zetter explained that the criteria and size of The Doctors Company credit may depend on the state where physicians practice.

“We allowed insurance carriers that we acquired to continue with their own claim-free discount program such as Florida’s First Professionals Insurance Company we acquired in 2011,” he said.

Doctors with other medical malpractice insurers may also be eligible for a credit up to 25%. In some instances, they may have to be claims free for 5 or 10 years, say insurance experts.

It pays to shop around before purchasing insurance.

3. If you work part time, make sure your premium reflects that

Physicians who see patients part time can receive up to a 75% discount on their medical liability insurance premiums.

The discounts are based on the hours the physician works per week. The fewer hours worked, the larger the discount. This type of discount does not vary by specialty.

According to The Doctors Company, working 10 hours or less per week may entitle doctors to a 75% discount; working 11-20 hours per week may entitle them to a 50% discount, and working 21-30 hours per week may entitle them to a 25% discount. If you are in this situation, it pays to ask your insurer if there is a discount available to you.

4. Look into your professional medical society insurance company

“I would look at your state medical association [or] state specialty society and talk to your colleagues to learn what premiums they’re paying and about any discounts they’re getting,” advised Mr. Zetter.

Some state medical societies have formed their own liability companies and offer lower premiums to their members because “they’re organized and managed by doctors, which makes their premiums more competitive,” Dr. Price said.

Other state medical societies endorse specific insurance carriers and offer their members a 5% discount for enrolling with them.

5. Enroll in a risk management program

Most insurers offer online educational activities designed to improve patient safety and reduce the risk of a lawsuit. Physicians may be eligible for both premium discounts and CME credits.

Medical Liability Mutual Insurance Company, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, operates in New York and offers physicians a premium discount of up to 5%, CME credit, and maintenance of certification credit for successfully completing its risk management program every other year.

ProAssurance members nationwide can earn 5% in premium discounts if they complete a 2-hour video series called “Back to Basics: Loss Prevention and Navigating Everyday Risks: Using Data to Drive Change.”

They can earn one credit for completing each webinar on topics such as “Medication Management: Minimizing Errors and Improving Safety” and “Opioid Prescribing: Keeping Patients Safe.”

MagMutual offers its insured physicians 1 CME credit for completing their specialty’s risk assessment and courses, which may be applied toward their premium discounts.

The Doctors Company offers its members a 5% premium discount if they complete 4 CME credits. One of its most popular courses is “How To Get Rid of a Difficult Patient.”

“Busy residents like the shorter case studies worth one-quarter credit that they can complete in 15 minutes,” said Ms. Boisvert.

“This is a good bargain from the physician’s standpoint and the fact that risk management education is offered online makes it a lot easier than going to a seminar in person,” said Dr. Price.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Getting a better deal might simply mean taking advantage of incentives and discounts your insurer may already offer. These include claims-free, new-to-practice, and working part-time discounts.

However, if you decide to shop around, keep in mind that discounts are just one factor that can affect your premium price – insurers look at your specialty, location, and claims history.

One of the most common ways physicians can earn discounts is by participating in risk management programs. With this type of program, physicians evaluate elements of their practice and documentation practices and identify areas that might leave them at risk for a lawsuit. While they save money, physician risk management programs also are designed to reduce malpractice claims, which ultimately minimizes the potential for bigger financial losses, insurance experts say.

“It’s a win-win situation when liability insurers and physicians work together to minimize risk, and it’s a win for patients,” said Gary Price, MD, president of The Physicians Foundation.

Doctors in private practice or employed by small hospitals that are not self-insured can qualify for these discounts, said David Zetter, president of Zetter HealthCare Management Consultants.

“I do a lot of work with medical malpractice companies trying to find clients policies. All the carriers are transparent about what physicians have to do to lower their premiums. Physicians can receive the discounts if they follow through and meet the insurer’s requirements,” said Mr. Zetter.

State insurance departments regulate medical malpractice insurance, including the premium credits insurers offer. Most states cap discounts at 25%, but some go as high as 70%, according to The Doctors Company, a national physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.

Insurers typically offer doctors several ways to earn discounts. The size of the discount also can depend on whether a doctor is new to a practice, remains claims free, or takes risk management courses.

In addition to the premium discount, some online risk management classes and webinars are eligible for CME credits.

“The credits can add up and they can be used for recertification or relicensure,” said Susan Boisvert, senior patient safety risk manager at The Doctors Company.

Here are five ways you may qualify for discounts with your insurer.

1. Make use of discounts available to new doctors

Doctors can earn hefty discounts on their premiums when they are no longer interns or residents and start practicing medicine. The Doctors Company usually gives a 50% discount on member premiums the first year they’re in practice and a 25% discount credit in their second year. The discounts end after that.

Other insurance carriers offer similar discounts to doctors starting to practice medicine. The deepest one is offered in the first year (at least 50%) and a smaller one (20%-25%) the second year, according to medical malpractice brokers.

“The new-to-practice discount is based solely on when the physician left their formal training to begin their practice for the first time; it is not based on claim-free history,” explained Mr. Zetter.

This is a very common discount used by different insurer carriers, said Dr. Price. “New physicians don’t have the same amount of risk of a lawsuit when they’re starting out. It’s unlikely they will have a claim and most liability actions have a 2-year time limit from the date of injury to be filed.”

2. Take advantage of being claims free

If you’ve been claims free for at least a few years, you may be eligible for a large discount.

“Doctors without claims are a better risk. Once a doctor has one claim, they’re likely to have a second, which the research shows,” said Mr. Zetter.

The most common credit The Doctors Company offers is 3 years of being claim free – this earns doctors up to 25%, he said. Mr. Zetter explained that the criteria and size of The Doctors Company credit may depend on the state where physicians practice.

“We allowed insurance carriers that we acquired to continue with their own claim-free discount program such as Florida’s First Professionals Insurance Company we acquired in 2011,” he said.

Doctors with other medical malpractice insurers may also be eligible for a credit up to 25%. In some instances, they may have to be claims free for 5 or 10 years, say insurance experts.

It pays to shop around before purchasing insurance.

3. If you work part time, make sure your premium reflects that

Physicians who see patients part time can receive up to a 75% discount on their medical liability insurance premiums.

The discounts are based on the hours the physician works per week. The fewer hours worked, the larger the discount. This type of discount does not vary by specialty.

According to The Doctors Company, working 10 hours or less per week may entitle doctors to a 75% discount; working 11-20 hours per week may entitle them to a 50% discount, and working 21-30 hours per week may entitle them to a 25% discount. If you are in this situation, it pays to ask your insurer if there is a discount available to you.

4. Look into your professional medical society insurance company

“I would look at your state medical association [or] state specialty society and talk to your colleagues to learn what premiums they’re paying and about any discounts they’re getting,” advised Mr. Zetter.

Some state medical societies have formed their own liability companies and offer lower premiums to their members because “they’re organized and managed by doctors, which makes their premiums more competitive,” Dr. Price said.

Other state medical societies endorse specific insurance carriers and offer their members a 5% discount for enrolling with them.

5. Enroll in a risk management program

Most insurers offer online educational activities designed to improve patient safety and reduce the risk of a lawsuit. Physicians may be eligible for both premium discounts and CME credits.

Medical Liability Mutual Insurance Company, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, operates in New York and offers physicians a premium discount of up to 5%, CME credit, and maintenance of certification credit for successfully completing its risk management program every other year.

ProAssurance members nationwide can earn 5% in premium discounts if they complete a 2-hour video series called “Back to Basics: Loss Prevention and Navigating Everyday Risks: Using Data to Drive Change.”

They can earn one credit for completing each webinar on topics such as “Medication Management: Minimizing Errors and Improving Safety” and “Opioid Prescribing: Keeping Patients Safe.”

MagMutual offers its insured physicians 1 CME credit for completing their specialty’s risk assessment and courses, which may be applied toward their premium discounts.

The Doctors Company offers its members a 5% premium discount if they complete 4 CME credits. One of its most popular courses is “How To Get Rid of a Difficult Patient.”

“Busy residents like the shorter case studies worth one-quarter credit that they can complete in 15 minutes,” said Ms. Boisvert.

“This is a good bargain from the physician’s standpoint and the fact that risk management education is offered online makes it a lot easier than going to a seminar in person,” said Dr. Price.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Boys may carry the weight, or overweight, of adults’ infertility

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

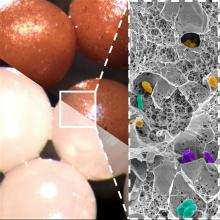

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Part-time physician: Is it a viable career choice?

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.

Pediatricians led the part-time pack in 2002, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics study. At the time, 15% of pediatricians reported their hours as part time. However, the numbers may have increased over the years. For example, a 2021 study by the department of pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, and Boston University found that almost 30% of graduating pediatricians sought part-time work at the end of their training.

At PS&D, Ms. Knoup said she has noticed a trend toward part-timers among primary care, behavioral health, and outpatient specialties such as endocrinology. “We’re also seeing it with the inpatient side in roles that are more shift based like hospitalists, radiologists, and critical care and ER doctors.”

Another trend Ms. Knoup has noticed is with early-career doctors. “They have a different mindset,” she said. “Younger generations are acutely aware of burnout. They may have experienced it in residency or during the pandemic. They’ve had a taste of that and don’t want to go down that road again, so they’re seeking part-time roles. It’s an intentional choice.”

Tracey O’Connell, MD, a radiologist, always knew that she wanted to work part time. “I had a baby as a resident, and I was pregnant with my second child as a fellow,” she said. “I was already feeling overwhelmed with medical training and having a family.”

Dr. O’Connell worked in private practice for 16 years on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with no nights or weekends.

“I still found it completely overwhelming,” she said. “Even though I had more days not working than working, I felt like the demands of medical life had advanced faster than human beings could adapt, and I still feel that way.”

Today she runs a part-time teleradiology practice from home but spends more time on her second career as a life coach. “Most of my clients are physicians looking for more fulfillment and sustainable ways of practicing medicine while maintaining their own identity as human beings, not just the all-consuming identity of ‘doctor,’ ” she said.

On the other end of the career spectrum is Lois Goodman, MD, an ob.gyn. in her late 70s. After 42 years in a group practice, she started her solo practice at 72, seeing patients 3 days per week. “I’m just happy to be working. That’s a tremendous payoff for me. I need to keep working for my mental health.”

How does part-time work affect physician shortages and care delivery?

Reducing clinical effort is one of the strategies physicians use to scale down overload. Still, it’s not viable as a long-term solution, said Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and a nationally regarded researcher on physician burnout.

“If all the physicians in a community went from working 100% FTE clinical to 50% FTE clinical, then the people in that community would have half the access to care that they had,” said Dr. Sinsky. “There’s less capacity in the system to care for patients.”

Some could argue, then, that part-time physician work may contribute to physician shortage predictions. An Association of American Medical Colleges report estimates there will be a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.

But physicians working part-time express a contrasting point of view. “I don’t believe that part-time workers are responsible for the health care shortage but rather, a great solution,” said Dr. O’Connell. “Because in order to continue working for a long time rather than quitting when the demands exceed human capacity, working part time is a great compromise to offer a life of more sustainable well-being and longevity as a physician, and still live a wholehearted life.”

Pros and cons of being a part-time physician

Pros

Less burnout: The American Medical Association has tracked burnout rates for 22 years. By the end of 2021, nearly 63% of physicians reported burnout symptoms, compared with 38% the year before. Going part time appears to reduce burnout, suggests a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Better work-life balance: Rachel Miller, MD, an ob.gyn., worked 60-70 hours weekly for 9 years. In 2022, she went to work as an OB hospitalist for a health care system that welcomes part-time clinicians. Since then, she has achieved a better work-life balance, putting in 26-28 hours a week. Dr. Miller now spends more time with her kids and in her additional role as an executive coach to leaders in the medical field.

More focus: “When I’m at work, I’m 100% mentally in and focused,” said Dr. Miller. “My interactions with patients are different because I’m not burned out. My demeanor and my willingness to connect are stronger.”

Better health: Mehmet Cilingiroglu, MD, with CardioSolution, traded full-time work for part time when health issues and a kidney transplant sidelined his 30-year career in 2018. “Despite my significant health issues, I’ve been able to continue working at a pace that suits me rather than having to retire,” he said. “Part-time physicians can still enjoy patient care, research, innovation, education, and training while balancing that with other areas of life.”

Errin Weisman, a DO who gave up full-time work in 2016, said cutting back makes her feel healthier, happier, and more energized. “Part-time work helps me to bring my A game each day I work and deliver the best care.” She’s also a life coach encouraging other physicians to find balance in their professional and personal lives.

Cons

Cut in pay: Obviously, the No. 1 con is you’ll make less working part time, so adjusting to a salary decrease can be a huge issue, especially if you don’t have other sources of income. Physicians paying off student loans, those caring for children or elderly parents, or those in their prime earning years needing to save for retirement may not be able to go part time.

Diminished career: The chance for promotions or being well known in your field can be diminished, as well as a loss of proficiency if you’re only performing surgery or procedures part time. In some specialties, working part time and not keeping up with (or being able to practice) newer technology developments can harm your career or reputation in the long run.

Missing out: While working part time has many benefits, physicians also experience a wide range of drawbacks. Dr. Goodman, for example, said she misses delivering babies and doing surgeries. Dr. Miller said she gave up some aspects of her specialty, like performing hysterectomies, participating in complex cases, and no longer having an office like she did as a full-time ob.gyn.

Loss of fellowship: Dr. O’Connell said she missed the camaraderie and sense of belonging when she scaled back her hours. “I felt like a fish out of water, that my values didn’t align with the group’s values,” she said. This led to self-doubt, frustrated colleagues, and a reduction in benefits.

Lost esteem: Dr. O’Connell also felt she was expected to work overtime without additional pay and was no longer eligible for bonuses. “I was treated as a team player when I was needed, but not when it came to perks and benefits and insider privilege,” she said. There may be a loss of esteem among colleagues and supervisors.

Overcoming stigma: Because part-time physician work is still not prevalent among colleagues, some may resist the idea, have less respect for it, perceive it as not being serious about your career as a physician, or associate it with being lazy or entitled.

Summing it up

Every physician must weigh the value and drawbacks of part-time work, but the more physicians who go this route, the more part-time medicine gains traction and the more physicians can learn about its values versus its drawbacks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.