User login

Sterile Water Bottles Deemed Unnecessary for Endoscopy

Like diners saving on drinks,

“No direct evidence supports the recommendation and widespread use of sterile water during gastrointestinal endosco-py procedures,” lead author Deepak Agrawal, MD, chief of gastroenterology & hepatology at the Dell Medical School, University Texas at Austin, and colleagues, wrote in Gastro Hep Advances. “Guidelines recommending sterile water during endoscopy are based on limited evidence and mostly expert opinions.”

After reviewing the literature back to 1975, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues considered the use of sterile water in endoscopy via three frameworks: medical evidence and guidelines, environmental and broader health effects, and financial costs.

Only 2 studies – both from the 1990s – directly compared sterile and tap water use in endoscopy. Neither showed an increased risk of infection from tap water. In fact, some cultures from allegedly sterile water bottles grew pathogenic bacteria, while no patient complications were reported in either study.

“The recommendations for sterile water contradict observations in other medical care scenarios, for example, for the irrigation of open wounds,” Dr. Agrawal and colleagues noted. “Similarly, there is no benefit in using sterile water for enteral feeds in immunosuppressed patients, and tap water enemas are routinely acceptable for colon cleansing before sigmoidoscopies in all patients, irrespective of immune status.”

Current guidelines, including the 2021 US multisociety guideline on reprocessing flexible GI endoscopes and accessories, recommend sterile water for procedures involving mucosal penetration but acknowledge low-quality supporting evidence. These recommendations are based on outdated studies, some unrelated to GI endoscopy, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues pointed out, and rely heavily on cross-referenced opinion statements rather than clinical data.

They went on to suggest a concerning possibility: all those plastic bottles may actually cause more health problems than prevent them. The review estimates that the production and transportation of sterile water bottles contributes over 6,000 metric tons of emissions per year from US endoscopy units alone. What’s more, as discarded bottles break down, they release greenhouse gases and microplastics, the latter of which have been linked to cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and endocrine disruption.

Dr. Agrawal and colleagues also underscored the financial toxicity of sterile water bottles. Considering a 1-liter bottle of sterile water costs $3-10, an endoscopy unit performing 30 procedures per day spends approximately $1,000-3,000 per month on bottled water alone. Scaled nationally, the routine use of sterile water costs tens of millions of dollars each year, not counting indirect expenses associated with stocking and waste disposal.

Considering the dubious clinical upside against the apparent environmental and financial downsides, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues urged endoscopy units to rethink routine sterile water use.

They proposed a pragmatic model: start the day with a new sterile or reusable bottle, refill with tap water for subsequent cases, and recycle the bottle at day’s end. Institutions should ensure their tap water meets safety standards, they added, such as those outlined in the Joint Commission’s 2022 R3 Report on standards for water management.

Dr. Agrawal and colleagues also called on GI societies to revise existing guidance to reflect today’s clinical and environmental realities. Until strong evidence supports the need for sterile water, they wrote, the smarter, safer, and more sustainable option may be simply turning on the tap.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Guardant, Exact Sciences, Freenome, and others.

In an editorial accompanying the study and comments to GI & Hepatology News, Dr. Seth A. Gross of NYU Langone Health urged gastroenterologists to reconsider the use of sterile water in endoscopy.

While the rationale for bottled water has centered on infection prevention, Gross argued that the evidence does not hold up, noting that this practice contradicts modern values around sustainability and evidence-based care.

The two relevant clinical studies comparing sterile versus tap water in endoscopy are almost 30 years old, he said, and neither detected an increased risk of infection with tap water, leading both to conclude that tap water is “safe and practical” for routine endoscopy.

Gross also pointed out the inconsistency of sterile water use in medical practice, noting that tap water is acceptable in procedures with higher infection risk than endoscopy.

“Lastly,” he added, “most people drink tap water and not sterile water on a daily basis without outbreaks of gastroenteritis from bacterial infections.”

Gross’s comments went beyond the data to emphasize the obvious but overlooked environmental impacts of sterile water bottles. He suggested several challenging suggestions to make medicine more ecofriendly, like reducing travel to conferences, increasing the availability of telehealth, and choosing reusable devices over disposables.

But “what’s hiding in plain sight,” he said, “is our use of sterile water.”

While acknowledging that some patients, like those who are immunocompromised, might still warrant sterile water, Gross supported the review’s recommendation to use tap water instead. He called on GI societies and regulatory bodies to re-examine current policy and pursue updated guidance.

“Sometimes going back to the basics,” he concluded, “could be the most innovative strategy with tremendous impact.”

Seth A. Gross, MD, AGAF, is clinical chief in the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology at NYU Langone Health, and professor at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, both in New York City. He reported no conflicts of interest.

In an editorial accompanying the study and comments to GI & Hepatology News, Dr. Seth A. Gross of NYU Langone Health urged gastroenterologists to reconsider the use of sterile water in endoscopy.

While the rationale for bottled water has centered on infection prevention, Gross argued that the evidence does not hold up, noting that this practice contradicts modern values around sustainability and evidence-based care.

The two relevant clinical studies comparing sterile versus tap water in endoscopy are almost 30 years old, he said, and neither detected an increased risk of infection with tap water, leading both to conclude that tap water is “safe and practical” for routine endoscopy.

Gross also pointed out the inconsistency of sterile water use in medical practice, noting that tap water is acceptable in procedures with higher infection risk than endoscopy.

“Lastly,” he added, “most people drink tap water and not sterile water on a daily basis without outbreaks of gastroenteritis from bacterial infections.”

Gross’s comments went beyond the data to emphasize the obvious but overlooked environmental impacts of sterile water bottles. He suggested several challenging suggestions to make medicine more ecofriendly, like reducing travel to conferences, increasing the availability of telehealth, and choosing reusable devices over disposables.

But “what’s hiding in plain sight,” he said, “is our use of sterile water.”

While acknowledging that some patients, like those who are immunocompromised, might still warrant sterile water, Gross supported the review’s recommendation to use tap water instead. He called on GI societies and regulatory bodies to re-examine current policy and pursue updated guidance.

“Sometimes going back to the basics,” he concluded, “could be the most innovative strategy with tremendous impact.”

Seth A. Gross, MD, AGAF, is clinical chief in the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology at NYU Langone Health, and professor at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, both in New York City. He reported no conflicts of interest.

In an editorial accompanying the study and comments to GI & Hepatology News, Dr. Seth A. Gross of NYU Langone Health urged gastroenterologists to reconsider the use of sterile water in endoscopy.

While the rationale for bottled water has centered on infection prevention, Gross argued that the evidence does not hold up, noting that this practice contradicts modern values around sustainability and evidence-based care.

The two relevant clinical studies comparing sterile versus tap water in endoscopy are almost 30 years old, he said, and neither detected an increased risk of infection with tap water, leading both to conclude that tap water is “safe and practical” for routine endoscopy.

Gross also pointed out the inconsistency of sterile water use in medical practice, noting that tap water is acceptable in procedures with higher infection risk than endoscopy.

“Lastly,” he added, “most people drink tap water and not sterile water on a daily basis without outbreaks of gastroenteritis from bacterial infections.”

Gross’s comments went beyond the data to emphasize the obvious but overlooked environmental impacts of sterile water bottles. He suggested several challenging suggestions to make medicine more ecofriendly, like reducing travel to conferences, increasing the availability of telehealth, and choosing reusable devices over disposables.

But “what’s hiding in plain sight,” he said, “is our use of sterile water.”

While acknowledging that some patients, like those who are immunocompromised, might still warrant sterile water, Gross supported the review’s recommendation to use tap water instead. He called on GI societies and regulatory bodies to re-examine current policy and pursue updated guidance.

“Sometimes going back to the basics,” he concluded, “could be the most innovative strategy with tremendous impact.”

Seth A. Gross, MD, AGAF, is clinical chief in the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology at NYU Langone Health, and professor at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, both in New York City. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Like diners saving on drinks,

“No direct evidence supports the recommendation and widespread use of sterile water during gastrointestinal endosco-py procedures,” lead author Deepak Agrawal, MD, chief of gastroenterology & hepatology at the Dell Medical School, University Texas at Austin, and colleagues, wrote in Gastro Hep Advances. “Guidelines recommending sterile water during endoscopy are based on limited evidence and mostly expert opinions.”

After reviewing the literature back to 1975, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues considered the use of sterile water in endoscopy via three frameworks: medical evidence and guidelines, environmental and broader health effects, and financial costs.

Only 2 studies – both from the 1990s – directly compared sterile and tap water use in endoscopy. Neither showed an increased risk of infection from tap water. In fact, some cultures from allegedly sterile water bottles grew pathogenic bacteria, while no patient complications were reported in either study.

“The recommendations for sterile water contradict observations in other medical care scenarios, for example, for the irrigation of open wounds,” Dr. Agrawal and colleagues noted. “Similarly, there is no benefit in using sterile water for enteral feeds in immunosuppressed patients, and tap water enemas are routinely acceptable for colon cleansing before sigmoidoscopies in all patients, irrespective of immune status.”

Current guidelines, including the 2021 US multisociety guideline on reprocessing flexible GI endoscopes and accessories, recommend sterile water for procedures involving mucosal penetration but acknowledge low-quality supporting evidence. These recommendations are based on outdated studies, some unrelated to GI endoscopy, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues pointed out, and rely heavily on cross-referenced opinion statements rather than clinical data.

They went on to suggest a concerning possibility: all those plastic bottles may actually cause more health problems than prevent them. The review estimates that the production and transportation of sterile water bottles contributes over 6,000 metric tons of emissions per year from US endoscopy units alone. What’s more, as discarded bottles break down, they release greenhouse gases and microplastics, the latter of which have been linked to cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and endocrine disruption.

Dr. Agrawal and colleagues also underscored the financial toxicity of sterile water bottles. Considering a 1-liter bottle of sterile water costs $3-10, an endoscopy unit performing 30 procedures per day spends approximately $1,000-3,000 per month on bottled water alone. Scaled nationally, the routine use of sterile water costs tens of millions of dollars each year, not counting indirect expenses associated with stocking and waste disposal.

Considering the dubious clinical upside against the apparent environmental and financial downsides, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues urged endoscopy units to rethink routine sterile water use.

They proposed a pragmatic model: start the day with a new sterile or reusable bottle, refill with tap water for subsequent cases, and recycle the bottle at day’s end. Institutions should ensure their tap water meets safety standards, they added, such as those outlined in the Joint Commission’s 2022 R3 Report on standards for water management.

Dr. Agrawal and colleagues also called on GI societies to revise existing guidance to reflect today’s clinical and environmental realities. Until strong evidence supports the need for sterile water, they wrote, the smarter, safer, and more sustainable option may be simply turning on the tap.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Guardant, Exact Sciences, Freenome, and others.

Like diners saving on drinks,

“No direct evidence supports the recommendation and widespread use of sterile water during gastrointestinal endosco-py procedures,” lead author Deepak Agrawal, MD, chief of gastroenterology & hepatology at the Dell Medical School, University Texas at Austin, and colleagues, wrote in Gastro Hep Advances. “Guidelines recommending sterile water during endoscopy are based on limited evidence and mostly expert opinions.”

After reviewing the literature back to 1975, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues considered the use of sterile water in endoscopy via three frameworks: medical evidence and guidelines, environmental and broader health effects, and financial costs.

Only 2 studies – both from the 1990s – directly compared sterile and tap water use in endoscopy. Neither showed an increased risk of infection from tap water. In fact, some cultures from allegedly sterile water bottles grew pathogenic bacteria, while no patient complications were reported in either study.

“The recommendations for sterile water contradict observations in other medical care scenarios, for example, for the irrigation of open wounds,” Dr. Agrawal and colleagues noted. “Similarly, there is no benefit in using sterile water for enteral feeds in immunosuppressed patients, and tap water enemas are routinely acceptable for colon cleansing before sigmoidoscopies in all patients, irrespective of immune status.”

Current guidelines, including the 2021 US multisociety guideline on reprocessing flexible GI endoscopes and accessories, recommend sterile water for procedures involving mucosal penetration but acknowledge low-quality supporting evidence. These recommendations are based on outdated studies, some unrelated to GI endoscopy, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues pointed out, and rely heavily on cross-referenced opinion statements rather than clinical data.

They went on to suggest a concerning possibility: all those plastic bottles may actually cause more health problems than prevent them. The review estimates that the production and transportation of sterile water bottles contributes over 6,000 metric tons of emissions per year from US endoscopy units alone. What’s more, as discarded bottles break down, they release greenhouse gases and microplastics, the latter of which have been linked to cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and endocrine disruption.

Dr. Agrawal and colleagues also underscored the financial toxicity of sterile water bottles. Considering a 1-liter bottle of sterile water costs $3-10, an endoscopy unit performing 30 procedures per day spends approximately $1,000-3,000 per month on bottled water alone. Scaled nationally, the routine use of sterile water costs tens of millions of dollars each year, not counting indirect expenses associated with stocking and waste disposal.

Considering the dubious clinical upside against the apparent environmental and financial downsides, Dr. Agrawal and colleagues urged endoscopy units to rethink routine sterile water use.

They proposed a pragmatic model: start the day with a new sterile or reusable bottle, refill with tap water for subsequent cases, and recycle the bottle at day’s end. Institutions should ensure their tap water meets safety standards, they added, such as those outlined in the Joint Commission’s 2022 R3 Report on standards for water management.

Dr. Agrawal and colleagues also called on GI societies to revise existing guidance to reflect today’s clinical and environmental realities. Until strong evidence supports the need for sterile water, they wrote, the smarter, safer, and more sustainable option may be simply turning on the tap.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Guardant, Exact Sciences, Freenome, and others.

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Cirrhosis Mortality Prediction Boosted by Machine Learning

“This highly inclusive, representative, and globally derived model has been externally validated,” Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia, told GI & Hepatology News. “This gives us a crystal ball. It helps hospital teams, transplant centers, gastroenterology and intensive care unit services triage and prioritize patients more effectively.”

The study supporting the model, which Bajaj said “could be used at this stage,” was published online in Gastroenterology. The model is available for downloading at https://silveys.shinyapps.io/app_cleared/.

CLEARED Cohort Analyzed

Wide variations across the world regarding available resources, outpatient services, reasons for admission, and etiologies of cirrhosis can influence patient outcomes, according to Bajaj and colleagues. Therefore, they sought to use ML approaches to improve prognostication for all countries.

They analyzed admission-day data from the prospective Chronic Liver Disease Evolution And Registry for Events and Decompensation (CLEARED) consortium, which includes inpatients with cirrhosis enrolled from six continents. The analysis compared ML approaches with logistical regression to predict inpatient mortality.

The researchers performed internal validation (75/25 split) and subdivision using World-Bank income status: low/low-middle (L-LMIC), upper middle (UMIC), and high (HIC). They determined that the ML model with the best area-under-the-curve (AUC) would be externally validated in a US-Veteran cirrhosis inpatient population.

The CLEARED cohort included 7239 cirrhosis inpatients (mean age, 56 years; 64% men; median MELD-Na, 25) from 115 centers globally; 22.5% of centers belonged to LMICs, 41% to UMICs, and 34% to HICs.

A total of 808 patients (11.1%) died in the hospital.

Random-Forest analysis showed the best AUC (0.815) with high calibration. This was significantly better than parametric logistic regression (AUC, 0.774) and LASSO (AUC, 0.787) models.

Random-Forest also was better than logistic regression regardless of country income-level: HIC (AUC,0.806), UMIC (AUC, 0.867), and L-LMICs (AUC, 0.768).

Of the top 15 important variables selected from Random-Forest, admission for acute kidney injury, hepatic encephalopathy, high MELD-Na/white blood count, and not being in high income country were variables most predictive of mortality.

In contrast, higher albumin, hemoglobin, diuretic use on admission, viral etiology, and being in a high-income country were most protective.

The Random-Forest model was validated in 28,670 veterans (mean age, 67 years; 96% men; median MELD-Na,15), with an inpatient mortality of 4% (1158 patients).

The final Random-Forest model, using 48 of the 67 original covariates, attained a strong AUC of 0.859. A refit version using only the top 15 variables achieved a comparable AUC of 0.851.

Clinical Relevance

“Cirrhosis and resultant organ failures remain a dynamic and multidisciplinary problem,” Bajaj noted. “Machine learning techniques are one part of multi-faceted management strategy that is required in this population.”

If patients fall into the high-risk category, he said, “careful consultation with patients, families, and clinical teams is needed before providing information, including where this model was derived from. The results of these discussions could be instructive regarding decisions for transfer, more aggressive monitoring/ICU transfer, palliative care or transplant assessments.”

Meena B. Bansal, MD, system chief, Division of Liver Diseases, Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, called the tool “very promising.” However, she told GI & Hepatology News, “it was validated on a VA [Veterans Affairs] cohort, which is a bit different than the cohort of patients seen at Mount Sinai. Therefore, validation in more academic tertiary care medical centers with high volume liver transplant would be helpful.”

Furthermore, said Bansal, who was not involved in the study, “they excluded those that receiving a liver transplant, and while only a small number, this is an important limitation.”

Nevertheless, she added, “Artificial intelligence has great potential in predictive risk models and will likely be a tool that assists for risk stratification, clinical management, and hopefully improved clinical outcomes.”

This study was partly supported by a VA Merit review to Bajaj and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were reported by any author.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“This highly inclusive, representative, and globally derived model has been externally validated,” Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia, told GI & Hepatology News. “This gives us a crystal ball. It helps hospital teams, transplant centers, gastroenterology and intensive care unit services triage and prioritize patients more effectively.”

The study supporting the model, which Bajaj said “could be used at this stage,” was published online in Gastroenterology. The model is available for downloading at https://silveys.shinyapps.io/app_cleared/.

CLEARED Cohort Analyzed

Wide variations across the world regarding available resources, outpatient services, reasons for admission, and etiologies of cirrhosis can influence patient outcomes, according to Bajaj and colleagues. Therefore, they sought to use ML approaches to improve prognostication for all countries.

They analyzed admission-day data from the prospective Chronic Liver Disease Evolution And Registry for Events and Decompensation (CLEARED) consortium, which includes inpatients with cirrhosis enrolled from six continents. The analysis compared ML approaches with logistical regression to predict inpatient mortality.

The researchers performed internal validation (75/25 split) and subdivision using World-Bank income status: low/low-middle (L-LMIC), upper middle (UMIC), and high (HIC). They determined that the ML model with the best area-under-the-curve (AUC) would be externally validated in a US-Veteran cirrhosis inpatient population.

The CLEARED cohort included 7239 cirrhosis inpatients (mean age, 56 years; 64% men; median MELD-Na, 25) from 115 centers globally; 22.5% of centers belonged to LMICs, 41% to UMICs, and 34% to HICs.

A total of 808 patients (11.1%) died in the hospital.

Random-Forest analysis showed the best AUC (0.815) with high calibration. This was significantly better than parametric logistic regression (AUC, 0.774) and LASSO (AUC, 0.787) models.

Random-Forest also was better than logistic regression regardless of country income-level: HIC (AUC,0.806), UMIC (AUC, 0.867), and L-LMICs (AUC, 0.768).

Of the top 15 important variables selected from Random-Forest, admission for acute kidney injury, hepatic encephalopathy, high MELD-Na/white blood count, and not being in high income country were variables most predictive of mortality.

In contrast, higher albumin, hemoglobin, diuretic use on admission, viral etiology, and being in a high-income country were most protective.

The Random-Forest model was validated in 28,670 veterans (mean age, 67 years; 96% men; median MELD-Na,15), with an inpatient mortality of 4% (1158 patients).

The final Random-Forest model, using 48 of the 67 original covariates, attained a strong AUC of 0.859. A refit version using only the top 15 variables achieved a comparable AUC of 0.851.

Clinical Relevance

“Cirrhosis and resultant organ failures remain a dynamic and multidisciplinary problem,” Bajaj noted. “Machine learning techniques are one part of multi-faceted management strategy that is required in this population.”

If patients fall into the high-risk category, he said, “careful consultation with patients, families, and clinical teams is needed before providing information, including where this model was derived from. The results of these discussions could be instructive regarding decisions for transfer, more aggressive monitoring/ICU transfer, palliative care or transplant assessments.”

Meena B. Bansal, MD, system chief, Division of Liver Diseases, Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, called the tool “very promising.” However, she told GI & Hepatology News, “it was validated on a VA [Veterans Affairs] cohort, which is a bit different than the cohort of patients seen at Mount Sinai. Therefore, validation in more academic tertiary care medical centers with high volume liver transplant would be helpful.”

Furthermore, said Bansal, who was not involved in the study, “they excluded those that receiving a liver transplant, and while only a small number, this is an important limitation.”

Nevertheless, she added, “Artificial intelligence has great potential in predictive risk models and will likely be a tool that assists for risk stratification, clinical management, and hopefully improved clinical outcomes.”

This study was partly supported by a VA Merit review to Bajaj and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were reported by any author.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“This highly inclusive, representative, and globally derived model has been externally validated,” Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia, told GI & Hepatology News. “This gives us a crystal ball. It helps hospital teams, transplant centers, gastroenterology and intensive care unit services triage and prioritize patients more effectively.”

The study supporting the model, which Bajaj said “could be used at this stage,” was published online in Gastroenterology. The model is available for downloading at https://silveys.shinyapps.io/app_cleared/.

CLEARED Cohort Analyzed

Wide variations across the world regarding available resources, outpatient services, reasons for admission, and etiologies of cirrhosis can influence patient outcomes, according to Bajaj and colleagues. Therefore, they sought to use ML approaches to improve prognostication for all countries.

They analyzed admission-day data from the prospective Chronic Liver Disease Evolution And Registry for Events and Decompensation (CLEARED) consortium, which includes inpatients with cirrhosis enrolled from six continents. The analysis compared ML approaches with logistical regression to predict inpatient mortality.

The researchers performed internal validation (75/25 split) and subdivision using World-Bank income status: low/low-middle (L-LMIC), upper middle (UMIC), and high (HIC). They determined that the ML model with the best area-under-the-curve (AUC) would be externally validated in a US-Veteran cirrhosis inpatient population.

The CLEARED cohort included 7239 cirrhosis inpatients (mean age, 56 years; 64% men; median MELD-Na, 25) from 115 centers globally; 22.5% of centers belonged to LMICs, 41% to UMICs, and 34% to HICs.

A total of 808 patients (11.1%) died in the hospital.

Random-Forest analysis showed the best AUC (0.815) with high calibration. This was significantly better than parametric logistic regression (AUC, 0.774) and LASSO (AUC, 0.787) models.

Random-Forest also was better than logistic regression regardless of country income-level: HIC (AUC,0.806), UMIC (AUC, 0.867), and L-LMICs (AUC, 0.768).

Of the top 15 important variables selected from Random-Forest, admission for acute kidney injury, hepatic encephalopathy, high MELD-Na/white blood count, and not being in high income country were variables most predictive of mortality.

In contrast, higher albumin, hemoglobin, diuretic use on admission, viral etiology, and being in a high-income country were most protective.

The Random-Forest model was validated in 28,670 veterans (mean age, 67 years; 96% men; median MELD-Na,15), with an inpatient mortality of 4% (1158 patients).

The final Random-Forest model, using 48 of the 67 original covariates, attained a strong AUC of 0.859. A refit version using only the top 15 variables achieved a comparable AUC of 0.851.

Clinical Relevance

“Cirrhosis and resultant organ failures remain a dynamic and multidisciplinary problem,” Bajaj noted. “Machine learning techniques are one part of multi-faceted management strategy that is required in this population.”

If patients fall into the high-risk category, he said, “careful consultation with patients, families, and clinical teams is needed before providing information, including where this model was derived from. The results of these discussions could be instructive regarding decisions for transfer, more aggressive monitoring/ICU transfer, palliative care or transplant assessments.”

Meena B. Bansal, MD, system chief, Division of Liver Diseases, Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, called the tool “very promising.” However, she told GI & Hepatology News, “it was validated on a VA [Veterans Affairs] cohort, which is a bit different than the cohort of patients seen at Mount Sinai. Therefore, validation in more academic tertiary care medical centers with high volume liver transplant would be helpful.”

Furthermore, said Bansal, who was not involved in the study, “they excluded those that receiving a liver transplant, and while only a small number, this is an important limitation.”

Nevertheless, she added, “Artificial intelligence has great potential in predictive risk models and will likely be a tool that assists for risk stratification, clinical management, and hopefully improved clinical outcomes.”

This study was partly supported by a VA Merit review to Bajaj and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were reported by any author.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Colonoscopy Costs Rise When Private Equity Acquires GI Practices, but Quality Does Not

Price increases ranged from about 5% to about 7%.

In view of the growing trend to such acquisitions, policy makers should monitor the impact of PE investment in medical practices, according to researchers led by health economist Daniel R. Arnold, PhD, of the Department of Health Services, Policy & Practice in the School of Public Health at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. “In a previous study of ours, gastroenterology stood out as a particularly attractive specialty to private equity,” Arnold told GI & Hepatology News.

Published in JAMA Health Forum, the economic evaluation of more than 1.1 million patients and 1.3 million colonoscopies concluded that PE acquisitions of GI sites are difficult to justify.

The Study

This difference-in-differences event study and economic evaluation analyzed data from US GI practices acquired by PE firms from 2015 to 2021. Commercial insurance claims covering more than 50 million enrollees were used to calculate price, spending, utilization, and quality measures from 2012 to 2021, with all data analyzed from April to September 2024.

The main outcomes were price, spending per physician, number of colonoscopies per physician, number of unique patients per physician, and quality, as defined by polyp detection, incomplete colonoscopies, and four adverse event measures: cardiovascular, serious and nonserious GI events, and any other adverse events.

The mean age of patients was 47.1 years, and 47.8% were men. The sample included 718, 851 colonoscopies conducted by 1494 physicians in 590, 900 patients across 1240 PE-acquired practice sites and 637, 990 control colonoscopies conducted by 2550 physicians in 527,380 patients across 2657 independent practice sites.

Among the findings:

- Colonoscopy prices at PE-acquired sites increased by 4.5% (95% CI, 2.5-6.6; P < .001) vs independent practices. That increase was much lower than that reported by Singh and colleagues for .

- The estimated price increase was 6.7% (95% CI, 4.2-9.3; P < .001) when only colonoscopies at PE practices with market shares above the 75th percentile (24.4%) in 2021 were considered. Both increases were in line with other research, Arnold said.

- Colonoscopy spending per physician increased by 16.0% (95% CI, 8.4%-24.0%; P < .001), while the number of colonoscopies and the number of unique patients per physician increased by 12.1% (95% CI, 5.3-19.4; P < .001) and 11.3% (95% CI, 4.4%-18.5%; P < .001), respectively. These measures, however, were already increasing before PE acquisition.

- No statistically significant associations were detected for the six quality measures analyzed.

Could such cost-raising acquisitions potentially be blocked by concerned regulators?

“No. Generally the purchases are at prices below what would require notification to federal authorities,” Arnold said. “The Department of Justice/Federal Trade Commission hinted at being willing to look at serial acquisitions in their 2023 Merger Guidelines, but until that happens, these will likely continue to fly under the radar.”

Still, as evidence of PE-associated poorer quality outcomes as well as clinician burnout continues to emerge, Arnold added, “I would advise physicians who get buyout offers from PE to educate themselves on what could happen to patients and staff if they choose to sell.”

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the study, health economist Atul Gupta, PhD, an assistant professor of healthcare management in the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, called it an “excellent addition to the developing literature examining the effects of private equity ownership of healthcare providers.” Very few studies have examined the effects on prices and quality for the same set of deals and providers. “This is important because we want to be able to do an apples-to-apples comparison of the effects on both outcomes before judging PE ownership,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

In an accompanying editorial , primary care physician Jane M. Zhu, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon, and not involved in the commercial-insurance-based study, said one interpretation of the findings may be that PE acquisition focuses on reducing inefficiencies, improving access by expanding practice capacity, and increasing throughput. “Another interpretation may be that PE acquisition is focused on the strategic exploitation of market and pricing power. The latter may have less of an impact on clinical measures like quality of care, but potentially, both strategies could be at play.”

Since this analysis focused on the commercial population, understanding how patient demographics may change after PE acquisition is a future avenue for exploration. “For instance, a potential explanation for both the price and utilization shifts might be if payer mix shifted toward more commercially insured patients at the expense of Medicaid or Medicare patients,” she wrote.

Zhu added that the impact of PE on prices and spending, by now replicated across different settings and specialties, is far clearer than the effect of PE on access and quality. “The analysis by Arnold et al is a welcome addition to the literature, generating important questions for future study and transparent monitoring as investor-owners become increasingly influential in healthcare.”

Going forward, said Gupta, an open question is whether the harmful effects of PE ownership of practices are differentially worse than those of other corporate entities such as insurers and hospital systems.

“There are reasons to believe that PE could be worse in theory. For example, their short-term investment horizon may force them to take measures that others will not as well as avoid investing into capital improvements that have a long-run payoff,” he said. “Their uniquely high dependence on debt and unbundling of real estate can severely hurt financial solvency of providers.” But high-quality evidence is lacking to compare the effects from these two distinct forms of corporatization.

The trend away from individual private practice is a reality, Arnold said. “The administrative burden on solo docs is becoming too much and physicians just seem to want to treat patients and not deal with it. So the options at this point really become selling to a hospital system or private equity.”

This study was funded by a grant from the philanthropic foundation Arnold Ventures (no family relation to Daniel Arnold).

Arnold reported receiving grants from Arnold Ventures during the conduct of the study. Gupta had no competing interests to declare. Zhu reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality during the submitted work and from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, and American Psychological Association, as well as personal fees from Cambia outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Price increases ranged from about 5% to about 7%.

In view of the growing trend to such acquisitions, policy makers should monitor the impact of PE investment in medical practices, according to researchers led by health economist Daniel R. Arnold, PhD, of the Department of Health Services, Policy & Practice in the School of Public Health at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. “In a previous study of ours, gastroenterology stood out as a particularly attractive specialty to private equity,” Arnold told GI & Hepatology News.

Published in JAMA Health Forum, the economic evaluation of more than 1.1 million patients and 1.3 million colonoscopies concluded that PE acquisitions of GI sites are difficult to justify.

The Study

This difference-in-differences event study and economic evaluation analyzed data from US GI practices acquired by PE firms from 2015 to 2021. Commercial insurance claims covering more than 50 million enrollees were used to calculate price, spending, utilization, and quality measures from 2012 to 2021, with all data analyzed from April to September 2024.

The main outcomes were price, spending per physician, number of colonoscopies per physician, number of unique patients per physician, and quality, as defined by polyp detection, incomplete colonoscopies, and four adverse event measures: cardiovascular, serious and nonserious GI events, and any other adverse events.

The mean age of patients was 47.1 years, and 47.8% were men. The sample included 718, 851 colonoscopies conducted by 1494 physicians in 590, 900 patients across 1240 PE-acquired practice sites and 637, 990 control colonoscopies conducted by 2550 physicians in 527,380 patients across 2657 independent practice sites.

Among the findings:

- Colonoscopy prices at PE-acquired sites increased by 4.5% (95% CI, 2.5-6.6; P < .001) vs independent practices. That increase was much lower than that reported by Singh and colleagues for .

- The estimated price increase was 6.7% (95% CI, 4.2-9.3; P < .001) when only colonoscopies at PE practices with market shares above the 75th percentile (24.4%) in 2021 were considered. Both increases were in line with other research, Arnold said.

- Colonoscopy spending per physician increased by 16.0% (95% CI, 8.4%-24.0%; P < .001), while the number of colonoscopies and the number of unique patients per physician increased by 12.1% (95% CI, 5.3-19.4; P < .001) and 11.3% (95% CI, 4.4%-18.5%; P < .001), respectively. These measures, however, were already increasing before PE acquisition.

- No statistically significant associations were detected for the six quality measures analyzed.

Could such cost-raising acquisitions potentially be blocked by concerned regulators?

“No. Generally the purchases are at prices below what would require notification to federal authorities,” Arnold said. “The Department of Justice/Federal Trade Commission hinted at being willing to look at serial acquisitions in their 2023 Merger Guidelines, but until that happens, these will likely continue to fly under the radar.”

Still, as evidence of PE-associated poorer quality outcomes as well as clinician burnout continues to emerge, Arnold added, “I would advise physicians who get buyout offers from PE to educate themselves on what could happen to patients and staff if they choose to sell.”

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the study, health economist Atul Gupta, PhD, an assistant professor of healthcare management in the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, called it an “excellent addition to the developing literature examining the effects of private equity ownership of healthcare providers.” Very few studies have examined the effects on prices and quality for the same set of deals and providers. “This is important because we want to be able to do an apples-to-apples comparison of the effects on both outcomes before judging PE ownership,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

In an accompanying editorial , primary care physician Jane M. Zhu, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon, and not involved in the commercial-insurance-based study, said one interpretation of the findings may be that PE acquisition focuses on reducing inefficiencies, improving access by expanding practice capacity, and increasing throughput. “Another interpretation may be that PE acquisition is focused on the strategic exploitation of market and pricing power. The latter may have less of an impact on clinical measures like quality of care, but potentially, both strategies could be at play.”

Since this analysis focused on the commercial population, understanding how patient demographics may change after PE acquisition is a future avenue for exploration. “For instance, a potential explanation for both the price and utilization shifts might be if payer mix shifted toward more commercially insured patients at the expense of Medicaid or Medicare patients,” she wrote.

Zhu added that the impact of PE on prices and spending, by now replicated across different settings and specialties, is far clearer than the effect of PE on access and quality. “The analysis by Arnold et al is a welcome addition to the literature, generating important questions for future study and transparent monitoring as investor-owners become increasingly influential in healthcare.”

Going forward, said Gupta, an open question is whether the harmful effects of PE ownership of practices are differentially worse than those of other corporate entities such as insurers and hospital systems.

“There are reasons to believe that PE could be worse in theory. For example, their short-term investment horizon may force them to take measures that others will not as well as avoid investing into capital improvements that have a long-run payoff,” he said. “Their uniquely high dependence on debt and unbundling of real estate can severely hurt financial solvency of providers.” But high-quality evidence is lacking to compare the effects from these two distinct forms of corporatization.

The trend away from individual private practice is a reality, Arnold said. “The administrative burden on solo docs is becoming too much and physicians just seem to want to treat patients and not deal with it. So the options at this point really become selling to a hospital system or private equity.”

This study was funded by a grant from the philanthropic foundation Arnold Ventures (no family relation to Daniel Arnold).

Arnold reported receiving grants from Arnold Ventures during the conduct of the study. Gupta had no competing interests to declare. Zhu reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality during the submitted work and from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, and American Psychological Association, as well as personal fees from Cambia outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Price increases ranged from about 5% to about 7%.

In view of the growing trend to such acquisitions, policy makers should monitor the impact of PE investment in medical practices, according to researchers led by health economist Daniel R. Arnold, PhD, of the Department of Health Services, Policy & Practice in the School of Public Health at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. “In a previous study of ours, gastroenterology stood out as a particularly attractive specialty to private equity,” Arnold told GI & Hepatology News.

Published in JAMA Health Forum, the economic evaluation of more than 1.1 million patients and 1.3 million colonoscopies concluded that PE acquisitions of GI sites are difficult to justify.

The Study

This difference-in-differences event study and economic evaluation analyzed data from US GI practices acquired by PE firms from 2015 to 2021. Commercial insurance claims covering more than 50 million enrollees were used to calculate price, spending, utilization, and quality measures from 2012 to 2021, with all data analyzed from April to September 2024.

The main outcomes were price, spending per physician, number of colonoscopies per physician, number of unique patients per physician, and quality, as defined by polyp detection, incomplete colonoscopies, and four adverse event measures: cardiovascular, serious and nonserious GI events, and any other adverse events.

The mean age of patients was 47.1 years, and 47.8% were men. The sample included 718, 851 colonoscopies conducted by 1494 physicians in 590, 900 patients across 1240 PE-acquired practice sites and 637, 990 control colonoscopies conducted by 2550 physicians in 527,380 patients across 2657 independent practice sites.

Among the findings:

- Colonoscopy prices at PE-acquired sites increased by 4.5% (95% CI, 2.5-6.6; P < .001) vs independent practices. That increase was much lower than that reported by Singh and colleagues for .

- The estimated price increase was 6.7% (95% CI, 4.2-9.3; P < .001) when only colonoscopies at PE practices with market shares above the 75th percentile (24.4%) in 2021 were considered. Both increases were in line with other research, Arnold said.

- Colonoscopy spending per physician increased by 16.0% (95% CI, 8.4%-24.0%; P < .001), while the number of colonoscopies and the number of unique patients per physician increased by 12.1% (95% CI, 5.3-19.4; P < .001) and 11.3% (95% CI, 4.4%-18.5%; P < .001), respectively. These measures, however, were already increasing before PE acquisition.

- No statistically significant associations were detected for the six quality measures analyzed.

Could such cost-raising acquisitions potentially be blocked by concerned regulators?

“No. Generally the purchases are at prices below what would require notification to federal authorities,” Arnold said. “The Department of Justice/Federal Trade Commission hinted at being willing to look at serial acquisitions in their 2023 Merger Guidelines, but until that happens, these will likely continue to fly under the radar.”

Still, as evidence of PE-associated poorer quality outcomes as well as clinician burnout continues to emerge, Arnold added, “I would advise physicians who get buyout offers from PE to educate themselves on what could happen to patients and staff if they choose to sell.”

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the study, health economist Atul Gupta, PhD, an assistant professor of healthcare management in the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, called it an “excellent addition to the developing literature examining the effects of private equity ownership of healthcare providers.” Very few studies have examined the effects on prices and quality for the same set of deals and providers. “This is important because we want to be able to do an apples-to-apples comparison of the effects on both outcomes before judging PE ownership,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

In an accompanying editorial , primary care physician Jane M. Zhu, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon, and not involved in the commercial-insurance-based study, said one interpretation of the findings may be that PE acquisition focuses on reducing inefficiencies, improving access by expanding practice capacity, and increasing throughput. “Another interpretation may be that PE acquisition is focused on the strategic exploitation of market and pricing power. The latter may have less of an impact on clinical measures like quality of care, but potentially, both strategies could be at play.”

Since this analysis focused on the commercial population, understanding how patient demographics may change after PE acquisition is a future avenue for exploration. “For instance, a potential explanation for both the price and utilization shifts might be if payer mix shifted toward more commercially insured patients at the expense of Medicaid or Medicare patients,” she wrote.

Zhu added that the impact of PE on prices and spending, by now replicated across different settings and specialties, is far clearer than the effect of PE on access and quality. “The analysis by Arnold et al is a welcome addition to the literature, generating important questions for future study and transparent monitoring as investor-owners become increasingly influential in healthcare.”

Going forward, said Gupta, an open question is whether the harmful effects of PE ownership of practices are differentially worse than those of other corporate entities such as insurers and hospital systems.

“There are reasons to believe that PE could be worse in theory. For example, their short-term investment horizon may force them to take measures that others will not as well as avoid investing into capital improvements that have a long-run payoff,” he said. “Their uniquely high dependence on debt and unbundling of real estate can severely hurt financial solvency of providers.” But high-quality evidence is lacking to compare the effects from these two distinct forms of corporatization.

The trend away from individual private practice is a reality, Arnold said. “The administrative burden on solo docs is becoming too much and physicians just seem to want to treat patients and not deal with it. So the options at this point really become selling to a hospital system or private equity.”

This study was funded by a grant from the philanthropic foundation Arnold Ventures (no family relation to Daniel Arnold).

Arnold reported receiving grants from Arnold Ventures during the conduct of the study. Gupta had no competing interests to declare. Zhu reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality during the submitted work and from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, and American Psychological Association, as well as personal fees from Cambia outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Less Invasive Sponge Test Stratifies Risk in Patients With Barrett’s Esophagus

The biomarker risk panel collected by the panesophageal Cytosponge-on-a-string in more than 900 UK patients helped identify those at highest risk for dysplasia or cancer and needing endoscopy. It was found safe for following low-risk patients who did not need endoscopy.

Endoscopic surveillance is the clinical standard for BE, but its effectiveness is inconsistent, wrote Rebecca C. Fitzgerald, MD, AGAF, professor in the Early Cancer Institute at the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England, and colleagues in The Lancet.

“It is often performed by nonspecialists, and recent trials show that around 10% of cases of dysplasia and cancer are missed, which means some patients re-present within a year of their surveillance procedure with a symptomatic cancer that should have been diagnosed earlier,” Fitzgerald told GI & Hepatology News.

Moreover, repeated endoscopy monitoring is stressful. “A simple nonendoscopic capsule sponge test done nearer to home is less scary and could be less operator-dependent. By reducing the burden of endoscopy in patients at very low risk we can focus more on the patients at higher risk,” she said.

In 2022, her research group had reported that the capsule sponge test, coupled with a centralized lab test for p53 and atypia, can risk-stratify patients into low-, moderate-, and high-risk groups. “In the current study, we wanted to check this risk stratification capsule sponge test in the real world. Our main aim was to see if we could conform the 2022 results with the hypothesis that the low-risk patients — more than 50% of patients in surveillance — would have a risk of high-grade dysplasia or cancer that was sufficiently low — that is, less than from 3% — and could therefore have follow-up with the capsule sponge without requiring endoscopy.”

The investigators hypothesized that the 15% at high risk would have a significant chance of dysplasia warranting endoscopy in a specialist center.

“Our results showed that in the low-risk group the risk of high-grade dysplasia or cancer was 0.4%, suggesting these patients could be offered follow-up with the capsule sponge test,” Fitzgerald said.

The high-risk group with a double biomarker positive (p53 and atypia) had an 85% risk for dysplasia or cancer. “We call this a tier 1 or ultra-high risk, and this suggests these cases merit a specialist endoscopy in a center that could treat the dysplasia/cancer,” she said.

Study Details

Adult participants (n = 910) were recruited from August 2020 to December 2024 in two multicenter, prospective, pragmatic implementation studies from 13 hospitals. Patients with nondysplastic BE on last endoscopy had a capsule sponge test.

Patient risk was assigned as low (clinical and capsule sponge biomarkers negative), moderate (negative for capsule sponge biomarkers, positive clinical biomarkers: age, sex, and segment length), or high risk (p53 abnormality, glandular atypia regardless of clinical biomarkers, or both). The primary outcome was a diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia or cancer necessitating treatment, according to the risk group.

In the cohort, 138 (15%) were classified as having high risk, 283 (31%) had moderate risk, and 489 (54%) had low risk.

The positive predictive value for any dysplasia or worse in the high-risk group was 37.7% (95% CI, 29.7-46.4). Patients with both atypia and aberrant p53 had the highest risk for high-grade dysplasia or cancer with a relative risk of 135.8 (95% CI, 32.7-564.0) vs the low-risk group.

The prevalence of high-grade dysplasia or cancer in the low-risk group was, as mentioned, just 0.4% (95% CI, 0.1-1.6), while the negative predictive value for any dysplasia or cancer was 97.8% (95% CI, 95.9-98.8). Applying a machine learning algorithm reduced the proportion needing p53 pathology review to 32% without missing any positive cases.

Offering a US perspective on the study, Nicholas J. Shaheen, MD, MPH, AGAF, professor of medicine and director of the NC Translational & Clinical Sciences Institute at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill, called the findings “very provocative.”

“We have known for some time that nonendoscopic techniques could be used to screen for Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer, allowing us to screen larger groups of patients in a more cost-effective manner compared to traditional upper endoscopy,” he told GI & Hepatology News. “This study suggests that, in addition to case-finding for Barrett’s [esophagus], a nonendoscopic sponge-based technique can also help us stratify risk, finding cases that either already harbor cancer or are at high risk to do so.”

Shaheen said these cases deserve immediate attention since they are most likely to benefit from timely endoscopic intervention. “The study also suggests that a nonendoscopic result could someday be used to decide subsequent follow-up, with low-risk patients undergoing further nonendoscopic surveillance, while higher-risk patients would move on to endoscopy. Such a paradigm could unburden our endoscopy units from low-risk patients unlikely to benefit from endoscopy as well as increase the numbers of patients who are able to be screened.”

Fitzgerald added, “The GI community is realizing that we need a better approach to managing patients with Barrett’s [esophagus]. In the UK this evidence is being considered by our guideline committee, and it would influence the upcoming guidelines in 2025 with a requirement to continue to audit the results. Outside of the UK we hope this will pave the way for nonendoscopic approaches to Barrett’s [esophagus] surveillance.”

One ongoing goal is to optimize the biomarkers, Fitzgerald said. “For patients with longer segments we would like to add additional genomic biomarkers to refine the risk predictions,” she said. “We need a more operator-independent, consistent method for monitoring Barrett’s [esophagus]. This large real-world study is highly encouraging for a more personalized and patient-friendly approach to Barrett’s [esophagus] surveillance.”

This study was funded by Innovate UK, Cancer Research UK, National Health Service England Cancer Alliance. Cytosponge technology is licensed by the Medical Research Council to Medtronic. Fitzgerald declared holding patents related to this test. Fitzgerald reported being a shareholder in Cyted Health.

Shaheen reported receiving research funding from Lucid Diagnostics and Cyted Health, both of which are manufacturers of nonendoscopic screening devices for BE.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The biomarker risk panel collected by the panesophageal Cytosponge-on-a-string in more than 900 UK patients helped identify those at highest risk for dysplasia or cancer and needing endoscopy. It was found safe for following low-risk patients who did not need endoscopy.

Endoscopic surveillance is the clinical standard for BE, but its effectiveness is inconsistent, wrote Rebecca C. Fitzgerald, MD, AGAF, professor in the Early Cancer Institute at the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England, and colleagues in The Lancet.

“It is often performed by nonspecialists, and recent trials show that around 10% of cases of dysplasia and cancer are missed, which means some patients re-present within a year of their surveillance procedure with a symptomatic cancer that should have been diagnosed earlier,” Fitzgerald told GI & Hepatology News.

Moreover, repeated endoscopy monitoring is stressful. “A simple nonendoscopic capsule sponge test done nearer to home is less scary and could be less operator-dependent. By reducing the burden of endoscopy in patients at very low risk we can focus more on the patients at higher risk,” she said.

In 2022, her research group had reported that the capsule sponge test, coupled with a centralized lab test for p53 and atypia, can risk-stratify patients into low-, moderate-, and high-risk groups. “In the current study, we wanted to check this risk stratification capsule sponge test in the real world. Our main aim was to see if we could conform the 2022 results with the hypothesis that the low-risk patients — more than 50% of patients in surveillance — would have a risk of high-grade dysplasia or cancer that was sufficiently low — that is, less than from 3% — and could therefore have follow-up with the capsule sponge without requiring endoscopy.”

The investigators hypothesized that the 15% at high risk would have a significant chance of dysplasia warranting endoscopy in a specialist center.

“Our results showed that in the low-risk group the risk of high-grade dysplasia or cancer was 0.4%, suggesting these patients could be offered follow-up with the capsule sponge test,” Fitzgerald said.

The high-risk group with a double biomarker positive (p53 and atypia) had an 85% risk for dysplasia or cancer. “We call this a tier 1 or ultra-high risk, and this suggests these cases merit a specialist endoscopy in a center that could treat the dysplasia/cancer,” she said.

Study Details

Adult participants (n = 910) were recruited from August 2020 to December 2024 in two multicenter, prospective, pragmatic implementation studies from 13 hospitals. Patients with nondysplastic BE on last endoscopy had a capsule sponge test.

Patient risk was assigned as low (clinical and capsule sponge biomarkers negative), moderate (negative for capsule sponge biomarkers, positive clinical biomarkers: age, sex, and segment length), or high risk (p53 abnormality, glandular atypia regardless of clinical biomarkers, or both). The primary outcome was a diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia or cancer necessitating treatment, according to the risk group.

In the cohort, 138 (15%) were classified as having high risk, 283 (31%) had moderate risk, and 489 (54%) had low risk.

The positive predictive value for any dysplasia or worse in the high-risk group was 37.7% (95% CI, 29.7-46.4). Patients with both atypia and aberrant p53 had the highest risk for high-grade dysplasia or cancer with a relative risk of 135.8 (95% CI, 32.7-564.0) vs the low-risk group.

The prevalence of high-grade dysplasia or cancer in the low-risk group was, as mentioned, just 0.4% (95% CI, 0.1-1.6), while the negative predictive value for any dysplasia or cancer was 97.8% (95% CI, 95.9-98.8). Applying a machine learning algorithm reduced the proportion needing p53 pathology review to 32% without missing any positive cases.

Offering a US perspective on the study, Nicholas J. Shaheen, MD, MPH, AGAF, professor of medicine and director of the NC Translational & Clinical Sciences Institute at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill, called the findings “very provocative.”

“We have known for some time that nonendoscopic techniques could be used to screen for Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer, allowing us to screen larger groups of patients in a more cost-effective manner compared to traditional upper endoscopy,” he told GI & Hepatology News. “This study suggests that, in addition to case-finding for Barrett’s [esophagus], a nonendoscopic sponge-based technique can also help us stratify risk, finding cases that either already harbor cancer or are at high risk to do so.”

Shaheen said these cases deserve immediate attention since they are most likely to benefit from timely endoscopic intervention. “The study also suggests that a nonendoscopic result could someday be used to decide subsequent follow-up, with low-risk patients undergoing further nonendoscopic surveillance, while higher-risk patients would move on to endoscopy. Such a paradigm could unburden our endoscopy units from low-risk patients unlikely to benefit from endoscopy as well as increase the numbers of patients who are able to be screened.”

Fitzgerald added, “The GI community is realizing that we need a better approach to managing patients with Barrett’s [esophagus]. In the UK this evidence is being considered by our guideline committee, and it would influence the upcoming guidelines in 2025 with a requirement to continue to audit the results. Outside of the UK we hope this will pave the way for nonendoscopic approaches to Barrett’s [esophagus] surveillance.”

One ongoing goal is to optimize the biomarkers, Fitzgerald said. “For patients with longer segments we would like to add additional genomic biomarkers to refine the risk predictions,” she said. “We need a more operator-independent, consistent method for monitoring Barrett’s [esophagus]. This large real-world study is highly encouraging for a more personalized and patient-friendly approach to Barrett’s [esophagus] surveillance.”

This study was funded by Innovate UK, Cancer Research UK, National Health Service England Cancer Alliance. Cytosponge technology is licensed by the Medical Research Council to Medtronic. Fitzgerald declared holding patents related to this test. Fitzgerald reported being a shareholder in Cyted Health.

Shaheen reported receiving research funding from Lucid Diagnostics and Cyted Health, both of which are manufacturers of nonendoscopic screening devices for BE.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The biomarker risk panel collected by the panesophageal Cytosponge-on-a-string in more than 900 UK patients helped identify those at highest risk for dysplasia or cancer and needing endoscopy. It was found safe for following low-risk patients who did not need endoscopy.

Endoscopic surveillance is the clinical standard for BE, but its effectiveness is inconsistent, wrote Rebecca C. Fitzgerald, MD, AGAF, professor in the Early Cancer Institute at the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England, and colleagues in The Lancet.

“It is often performed by nonspecialists, and recent trials show that around 10% of cases of dysplasia and cancer are missed, which means some patients re-present within a year of their surveillance procedure with a symptomatic cancer that should have been diagnosed earlier,” Fitzgerald told GI & Hepatology News.

Moreover, repeated endoscopy monitoring is stressful. “A simple nonendoscopic capsule sponge test done nearer to home is less scary and could be less operator-dependent. By reducing the burden of endoscopy in patients at very low risk we can focus more on the patients at higher risk,” she said.

In 2022, her research group had reported that the capsule sponge test, coupled with a centralized lab test for p53 and atypia, can risk-stratify patients into low-, moderate-, and high-risk groups. “In the current study, we wanted to check this risk stratification capsule sponge test in the real world. Our main aim was to see if we could conform the 2022 results with the hypothesis that the low-risk patients — more than 50% of patients in surveillance — would have a risk of high-grade dysplasia or cancer that was sufficiently low — that is, less than from 3% — and could therefore have follow-up with the capsule sponge without requiring endoscopy.”

The investigators hypothesized that the 15% at high risk would have a significant chance of dysplasia warranting endoscopy in a specialist center.

“Our results showed that in the low-risk group the risk of high-grade dysplasia or cancer was 0.4%, suggesting these patients could be offered follow-up with the capsule sponge test,” Fitzgerald said.

The high-risk group with a double biomarker positive (p53 and atypia) had an 85% risk for dysplasia or cancer. “We call this a tier 1 or ultra-high risk, and this suggests these cases merit a specialist endoscopy in a center that could treat the dysplasia/cancer,” she said.

Study Details

Adult participants (n = 910) were recruited from August 2020 to December 2024 in two multicenter, prospective, pragmatic implementation studies from 13 hospitals. Patients with nondysplastic BE on last endoscopy had a capsule sponge test.

Patient risk was assigned as low (clinical and capsule sponge biomarkers negative), moderate (negative for capsule sponge biomarkers, positive clinical biomarkers: age, sex, and segment length), or high risk (p53 abnormality, glandular atypia regardless of clinical biomarkers, or both). The primary outcome was a diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia or cancer necessitating treatment, according to the risk group.

In the cohort, 138 (15%) were classified as having high risk, 283 (31%) had moderate risk, and 489 (54%) had low risk.

The positive predictive value for any dysplasia or worse in the high-risk group was 37.7% (95% CI, 29.7-46.4). Patients with both atypia and aberrant p53 had the highest risk for high-grade dysplasia or cancer with a relative risk of 135.8 (95% CI, 32.7-564.0) vs the low-risk group.

The prevalence of high-grade dysplasia or cancer in the low-risk group was, as mentioned, just 0.4% (95% CI, 0.1-1.6), while the negative predictive value for any dysplasia or cancer was 97.8% (95% CI, 95.9-98.8). Applying a machine learning algorithm reduced the proportion needing p53 pathology review to 32% without missing any positive cases.

Offering a US perspective on the study, Nicholas J. Shaheen, MD, MPH, AGAF, professor of medicine and director of the NC Translational & Clinical Sciences Institute at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill, called the findings “very provocative.”

“We have known for some time that nonendoscopic techniques could be used to screen for Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer, allowing us to screen larger groups of patients in a more cost-effective manner compared to traditional upper endoscopy,” he told GI & Hepatology News. “This study suggests that, in addition to case-finding for Barrett’s [esophagus], a nonendoscopic sponge-based technique can also help us stratify risk, finding cases that either already harbor cancer or are at high risk to do so.”

Shaheen said these cases deserve immediate attention since they are most likely to benefit from timely endoscopic intervention. “The study also suggests that a nonendoscopic result could someday be used to decide subsequent follow-up, with low-risk patients undergoing further nonendoscopic surveillance, while higher-risk patients would move on to endoscopy. Such a paradigm could unburden our endoscopy units from low-risk patients unlikely to benefit from endoscopy as well as increase the numbers of patients who are able to be screened.”

Fitzgerald added, “The GI community is realizing that we need a better approach to managing patients with Barrett’s [esophagus]. In the UK this evidence is being considered by our guideline committee, and it would influence the upcoming guidelines in 2025 with a requirement to continue to audit the results. Outside of the UK we hope this will pave the way for nonendoscopic approaches to Barrett’s [esophagus] surveillance.”

One ongoing goal is to optimize the biomarkers, Fitzgerald said. “For patients with longer segments we would like to add additional genomic biomarkers to refine the risk predictions,” she said. “We need a more operator-independent, consistent method for monitoring Barrett’s [esophagus]. This large real-world study is highly encouraging for a more personalized and patient-friendly approach to Barrett’s [esophagus] surveillance.”

This study was funded by Innovate UK, Cancer Research UK, National Health Service England Cancer Alliance. Cytosponge technology is licensed by the Medical Research Council to Medtronic. Fitzgerald declared holding patents related to this test. Fitzgerald reported being a shareholder in Cyted Health.

Shaheen reported receiving research funding from Lucid Diagnostics and Cyted Health, both of which are manufacturers of nonendoscopic screening devices for BE.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

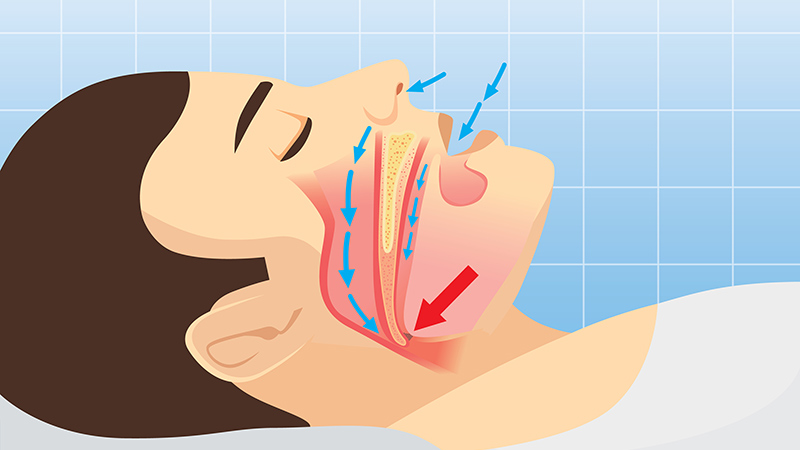

Sleep Changes in IBD Could Signal Inflammation, Flareups

, an observational study suggested.

Sleep data from 101 study participants over a mean duration of about 228 days revealed that altered sleep architecture was only apparent when inflammation was present — symptoms alone did not impact sleep cycles or signal inflammation.

“We thought symptoms might have an impact on sleep, but interestingly, our data showed that measurable changes like reduced rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and increased light sleep only occurred during periods of active inflammation,” Robert Hirten, MD, associate professor of Medicine (Gastroenterology), and Artificial Intelligence and Human Health, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, told GI & Hepatology News.

“It was also interesting to see distinct patterns in sleep metrics begin to shift over the 45 days before a flare, suggesting the potential for sleep to serve as an early indicator of disease activity,” he added.

“Sleep is often overlooked in the management of IBD, but it may provide valuable insights into a patient’s underlying disease state,” he said. “While sleep monitoring isn’t yet a standard part of IBD care, this study highlights its potential as a noninvasive window into disease activity, and a promising area for future clinical integration.”

The study was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Less REM Sleep, More Light Sleep

Researchers assessed the impact of inflammation and symptoms on sleep architecture in IBD by analyzing data from 101 individuals who answered daily disease activity surveys and wore a wearable device.

The mean age of participants was 41 years and 65.3% were women. Sixty-three participants (62.4%) had Crohn’s disease (CD) and 38 (37.6%) had ulcerative colitis (UC).

Almost 40 (39.6%) participants used an Apple Watch; 50 (49.5%) used a Fitbit; and 11 (10.9%) used an Oura ring. Sleep architecture, sleep efficiency, and total hours asleep were collected from the devices. Participants were encouraged to wear their devices for at least 4 days per week and 8 hours per day and were not required to wear them at night. Participants provided data by linking their devices to ehive, Mount Sinai’s custom app.

Daily clinical disease activity was assessed using the UC or CD Patient Reported Outcome-2 survey. Participants were asked to answer at least four daily surveys each week.

Associations between sleep metrics and periods of symptomatic and inflammatory flares, and combinations of symptomatic and inflammatory activity, were compared to periods of symptomatic and inflammatory remission.

Furthermore, researchers explored the rate of change in sleep metrics for 45 days before and after inflammatory and symptomatic flares.

Participants contributed a mean duration of 228.16 nights of wearable data. During active inflammation, they spent a lower percentage of sleep time in REM (20% vs 21.59%) and a greater percentage of sleep time in light sleep (62.23% vs 59.95%) than during inflammatory remission. No differences were observed in the mean percentage of time in deep sleep, sleep efficiency, or total time asleep.

During symptomatic flares, there were no differences in the percentage of sleep time in REM sleep, deep sleep, light sleep, or sleep efficiency compared with periods of inflammatory remission. However, participants slept less overall during symptomatic flares compared with during symptomatic remission.

Compared with during asymptomatic and uninflamed periods, during asymptomatic but inflamed periods, participants spent a lower percentage of time in REM sleep, and more time in light sleep; however, there were no differences in sleep efficiency or total time asleep.

Similarly, participants had more light sleep and less REM sleep during symptomatic and inflammatory flares than during asymptomatic and uninflamed periods — but there were no differences in the percentage of time spent in deep sleep, in sleep efficiency, and the total time asleep.

Symptomatic flares alone, without inflammation, did not impact sleep metrics, the researchers concluded. However, periods with active inflammation were associated with a significantly smaller percentage of sleep time in REM sleep and a greater percentage of sleep time in light sleep.

The team also performed longitudinal mapping of sleep patterns before, during, and after disease exacerbations by analyzing sleep data for 6 weeks before and 6 weeks after flare episodes.

They found that sleep disturbances significantly worsen leading up to inflammatory flares and improve afterward, suggesting that sleep changes may signal upcoming increased disease activity. Evaluating the intersection of inflammatory and symptomatic flares, altered sleep architecture was only evident when inflammation was present.

“These findings raise important questions about whether intervening on sleep can actually impact inflammation or disease trajectory in IBD,” Hirten said. “Next steps include studying whether targeted sleep interventions can improve both sleep and IBD outcomes.”

While this research is still in the early stages, he said, “it suggests that sleep may have a relationship with inflammatory activity in IBD. For patients, it reinforces the value of paying attention to sleep changes.”

The findings also show the potential of wearable devices to guide more personalized monitoring, he added. “More work is needed before sleep metrics can be used routinely in clinical decision-making.”

Validates the Use of Wearables

Commenting on the study for GI & Hepatology News, Michael Mintz, MD, a gastroenterologist at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian in New York City, observed, “Gastrointestinal symptoms often do not correlate with objective disease activity in IBD, creating a diagnostic challenge for gastroenterologists. Burdensome, expensive, and/or invasive testing, such as colonoscopies, stool tests, or imaging, are frequently required to monitor disease activity.”