User login

Dry cough and dyspnea

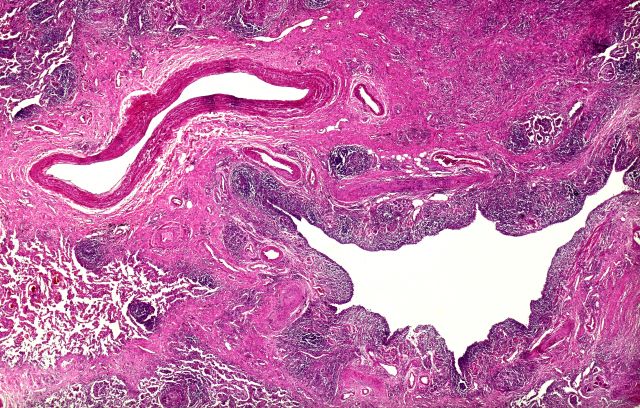

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 58-year-old man with a 20-year–pack history of smoking initially presented with a persistent dry cough and dyspnea. Clubbing was noted on physical examination and breath sounds in the right upper lung were weak. Other than hypertension, which the patient manages with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, medical history is unremarkable. The patient notes that this medication has always made him cough, but dyspnea has only developed over the past 6 weeks. Respiratory symptoms prompted a chest radiograph which revealed a mass in the upper lobe of the right lung. Transbronchial lung biopsy of the right lung reveals components of adenocarcinoma; the specimen is otherwise squamous.

Drugging the undruggable

including 68% of pancreatic tumors and 20% of all non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLC).

We now have a treatment – sotorasib – for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC that is driven by a KRAS mutation (G12C). And, now, there is a second treatment – adagrasib – under study, which, according to a presentation recently made at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, looks promising.

Ras is a membrane-bound regulatory protein (G protein) belonging to the family of guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). Ras functions as a guanosine diphosphate/triphosphate binary switch by cycling between the active GTP-bound and the inactive GDP-bound states in response to extracellular stimuli. The KRAS (G12C) mutation affects the active form of KRAS and results in abnormally high concentrations of GTP-bound KRAS leading to hyperactivation of downstream oncogenic pathways and uncontrolled cell growth, specifically of ERK and MEK signaling pathways.

At the ASCO annual meeting in June, Spira and colleagues reported the results of cohort A of the KRYSTAL-1 study evaluating adagrasib as second-line therapy patients with advanced solid tumors harboring a KRAS (G12C) mutation. Like sotorasib, adagrasib is a KRAS (G12C) inhibitor that irreversibly and selectively binds KRAS (G12C), locking it in its inactive state. In this study, patients had to have failed first-line chemotherapy and immunotherapy with 43% of lung cancer patients responding. The 12-month overall survival (OS) was 51%, median overall survival was 12.6 and median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.5 months. Twenty-five patients with KRAS (G12C)–mutant NSCLC and active, untreated central nervous system metastases received adagrasib in a phase 1b cohort. The intracranial overall response rate was 31.6% and median intracranial PFS was 4.2 months. Systemic ORR was 35.0% (7/20), the disease control rate was 80.0% (16/20) and median duration of response was 9.6 months. Based on these data, a phase 3 trial evaluating adagrasib monotherapy versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with KRAS (G12C) mutant NSCLC is ongoing.

The Food and Drug Administration approval of sotorasib in 2021 was, in part, based on the results of a single-arm, phase 2, second-line study of patients who had previously received platinum-based chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy. An ORR rate of 37.1% was reported with a median PFS of 6.8 months and median OS of 12.5 months leading to the FDA approval. Responses were observed across the range of baseline PD-L1 expression levels: 48% of PD-L1 negative, 39% with PD-L1 between 1%-49%, and 22% of patients with a PD-L1 of greater than 50% having a response.

The major toxicities observed in these studies were gastrointestinal (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting) and hepatic (elevated liver enzymes). About 97% of patients on adagrasib experienced any treatment-related adverse events, and 43% experienced a grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event leading to dose reduction in 52% of patients, a dose interruption in 61% of patients, and a 7% discontinuation rate. About 70% of patients treated with sotorasib had a treatment-related adverse event of any grade, and 21% reported grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events.

A subgroup in the KRYSTAL-1 trial reported an intracranial ORR of 32% in patients with active, untreated CNS metastases. Median overall survival has not yet reached concordance between systemic and intracranial disease control was 88%. In addition, preliminary data from two patients with untreated CNS metastases from a phase 1b cohort found cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of adagrasib with a mean ratio of unbound brain-to-plasma concentration of 0.47, which is comparable or exceeds values for known CNS-penetrant tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Unfortunately, KRAS (G12C) is not the only KRAS mutation out there. There are a myriad of others, such as G12V and G12D. Hopefully, we will be seeing more drugs aimed at this set of important mutations. Another question, of course, is when and if these drugs will move to the first-line setting.

Dr. Schiller is a medical oncologist and founding member of Oncologists United for Climate and Health. She is a former board member of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and a current board member of the Lung Cancer Research Foundation.

including 68% of pancreatic tumors and 20% of all non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLC).

We now have a treatment – sotorasib – for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC that is driven by a KRAS mutation (G12C). And, now, there is a second treatment – adagrasib – under study, which, according to a presentation recently made at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, looks promising.

Ras is a membrane-bound regulatory protein (G protein) belonging to the family of guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). Ras functions as a guanosine diphosphate/triphosphate binary switch by cycling between the active GTP-bound and the inactive GDP-bound states in response to extracellular stimuli. The KRAS (G12C) mutation affects the active form of KRAS and results in abnormally high concentrations of GTP-bound KRAS leading to hyperactivation of downstream oncogenic pathways and uncontrolled cell growth, specifically of ERK and MEK signaling pathways.

At the ASCO annual meeting in June, Spira and colleagues reported the results of cohort A of the KRYSTAL-1 study evaluating adagrasib as second-line therapy patients with advanced solid tumors harboring a KRAS (G12C) mutation. Like sotorasib, adagrasib is a KRAS (G12C) inhibitor that irreversibly and selectively binds KRAS (G12C), locking it in its inactive state. In this study, patients had to have failed first-line chemotherapy and immunotherapy with 43% of lung cancer patients responding. The 12-month overall survival (OS) was 51%, median overall survival was 12.6 and median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.5 months. Twenty-five patients with KRAS (G12C)–mutant NSCLC and active, untreated central nervous system metastases received adagrasib in a phase 1b cohort. The intracranial overall response rate was 31.6% and median intracranial PFS was 4.2 months. Systemic ORR was 35.0% (7/20), the disease control rate was 80.0% (16/20) and median duration of response was 9.6 months. Based on these data, a phase 3 trial evaluating adagrasib monotherapy versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with KRAS (G12C) mutant NSCLC is ongoing.

The Food and Drug Administration approval of sotorasib in 2021 was, in part, based on the results of a single-arm, phase 2, second-line study of patients who had previously received platinum-based chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy. An ORR rate of 37.1% was reported with a median PFS of 6.8 months and median OS of 12.5 months leading to the FDA approval. Responses were observed across the range of baseline PD-L1 expression levels: 48% of PD-L1 negative, 39% with PD-L1 between 1%-49%, and 22% of patients with a PD-L1 of greater than 50% having a response.

The major toxicities observed in these studies were gastrointestinal (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting) and hepatic (elevated liver enzymes). About 97% of patients on adagrasib experienced any treatment-related adverse events, and 43% experienced a grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event leading to dose reduction in 52% of patients, a dose interruption in 61% of patients, and a 7% discontinuation rate. About 70% of patients treated with sotorasib had a treatment-related adverse event of any grade, and 21% reported grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events.

A subgroup in the KRYSTAL-1 trial reported an intracranial ORR of 32% in patients with active, untreated CNS metastases. Median overall survival has not yet reached concordance between systemic and intracranial disease control was 88%. In addition, preliminary data from two patients with untreated CNS metastases from a phase 1b cohort found cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of adagrasib with a mean ratio of unbound brain-to-plasma concentration of 0.47, which is comparable or exceeds values for known CNS-penetrant tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Unfortunately, KRAS (G12C) is not the only KRAS mutation out there. There are a myriad of others, such as G12V and G12D. Hopefully, we will be seeing more drugs aimed at this set of important mutations. Another question, of course, is when and if these drugs will move to the first-line setting.

Dr. Schiller is a medical oncologist and founding member of Oncologists United for Climate and Health. She is a former board member of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and a current board member of the Lung Cancer Research Foundation.

including 68% of pancreatic tumors and 20% of all non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLC).

We now have a treatment – sotorasib – for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC that is driven by a KRAS mutation (G12C). And, now, there is a second treatment – adagrasib – under study, which, according to a presentation recently made at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, looks promising.

Ras is a membrane-bound regulatory protein (G protein) belonging to the family of guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). Ras functions as a guanosine diphosphate/triphosphate binary switch by cycling between the active GTP-bound and the inactive GDP-bound states in response to extracellular stimuli. The KRAS (G12C) mutation affects the active form of KRAS and results in abnormally high concentrations of GTP-bound KRAS leading to hyperactivation of downstream oncogenic pathways and uncontrolled cell growth, specifically of ERK and MEK signaling pathways.

At the ASCO annual meeting in June, Spira and colleagues reported the results of cohort A of the KRYSTAL-1 study evaluating adagrasib as second-line therapy patients with advanced solid tumors harboring a KRAS (G12C) mutation. Like sotorasib, adagrasib is a KRAS (G12C) inhibitor that irreversibly and selectively binds KRAS (G12C), locking it in its inactive state. In this study, patients had to have failed first-line chemotherapy and immunotherapy with 43% of lung cancer patients responding. The 12-month overall survival (OS) was 51%, median overall survival was 12.6 and median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.5 months. Twenty-five patients with KRAS (G12C)–mutant NSCLC and active, untreated central nervous system metastases received adagrasib in a phase 1b cohort. The intracranial overall response rate was 31.6% and median intracranial PFS was 4.2 months. Systemic ORR was 35.0% (7/20), the disease control rate was 80.0% (16/20) and median duration of response was 9.6 months. Based on these data, a phase 3 trial evaluating adagrasib monotherapy versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with KRAS (G12C) mutant NSCLC is ongoing.

The Food and Drug Administration approval of sotorasib in 2021 was, in part, based on the results of a single-arm, phase 2, second-line study of patients who had previously received platinum-based chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy. An ORR rate of 37.1% was reported with a median PFS of 6.8 months and median OS of 12.5 months leading to the FDA approval. Responses were observed across the range of baseline PD-L1 expression levels: 48% of PD-L1 negative, 39% with PD-L1 between 1%-49%, and 22% of patients with a PD-L1 of greater than 50% having a response.

The major toxicities observed in these studies were gastrointestinal (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting) and hepatic (elevated liver enzymes). About 97% of patients on adagrasib experienced any treatment-related adverse events, and 43% experienced a grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event leading to dose reduction in 52% of patients, a dose interruption in 61% of patients, and a 7% discontinuation rate. About 70% of patients treated with sotorasib had a treatment-related adverse event of any grade, and 21% reported grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events.

A subgroup in the KRYSTAL-1 trial reported an intracranial ORR of 32% in patients with active, untreated CNS metastases. Median overall survival has not yet reached concordance between systemic and intracranial disease control was 88%. In addition, preliminary data from two patients with untreated CNS metastases from a phase 1b cohort found cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of adagrasib with a mean ratio of unbound brain-to-plasma concentration of 0.47, which is comparable or exceeds values for known CNS-penetrant tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Unfortunately, KRAS (G12C) is not the only KRAS mutation out there. There are a myriad of others, such as G12V and G12D. Hopefully, we will be seeing more drugs aimed at this set of important mutations. Another question, of course, is when and if these drugs will move to the first-line setting.

Dr. Schiller is a medical oncologist and founding member of Oncologists United for Climate and Health. She is a former board member of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and a current board member of the Lung Cancer Research Foundation.

Aggression toward health care providers common during pandemic

After an aggressive event or abuse occurred, 56% of providers considered changing their care tasks, and more than a third considered quitting their profession.

“Aggression of any sort against health care providers is not a new social phenomenon, and it has existed as far as medicine and health care is reported in literature. However, the phenomenon of aggression against health care providers during the pandemic grew worse,” senior study author Adrian Baranchuk, MD, a professor of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., told this news organization.

The study was published online in Current Problems in Cardiology

Survey snapshot

Dr. Baranchuk and colleagues, with the support of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology, developed a survey to characterize the frequency and types of abuse that frontline health professionals faced. They invited health care professionals from Latin America who had provided care since March 2020 to participate.

Between January and February 2022, 3,544 participants from 19 countries took the survey. Among them, 70.8% were physicians, 16% were nurses, and 13.2% were other health team members, such as administrative staff and technicians. About 58.5% were women, and 74.7% provided direct care to patients with COVID-19.

Overall, 54.8% of respondents reported acts of aggression. Of this group, 95.6% reported verbal abuse, 11.1% reported physical abuse, and 19.9% reported other types of abuse, including microaggressions.

About 13% of respondents reported experiencing some form of aggression daily, 26.4% experienced abuse weekly, and 38.8% reported violence a few times per month. Typically, the incidents involved patients’ relatives or both the patients and their relatives.

Nearly half of those who reported abuse experienced psychosomatic symptoms after the event, and 12% sought psychological care.

Administrative staff were 3.5 times more likely to experience abuse than other health care workers. Doctors and nurses were about twice as likely to experience abuse.

In addition, women, younger staff, and those who worked directly with COVID-19 patients were more likely to report abuse.

‘Shocking results’

Dr. Baranchuk, a native of Argentina, said people initially celebrated doctors and nurses for keeping communities safe. In several countries across Latin America, for instance, people lit candles, applauded at certain hours, and posted support on social media. As pandemic-related policies changed, however, health care providers faced unrest as people grew tired of wearing masks, maintaining social distance, and obeying restrictions at public spaces such as clubs and restaurants.

“This fatigue toward the social changes grew, but people didn’t have a specific target, and slowly and gradually, health care providers became the target of frustration and hate,” said Dr. Baranchuk. “In areas of the world where legislation is more flexible and less strict in charging individuals with poor or unacceptable behavior toward members of the health care team, aggression and microaggression became more frequent.”

“The results we obtained were more shocking than we expected,” Sebastián García-Zamora, MD, the lead study author and head of the coronary care unit at the Delta Clinic, Buenos Aires, said in an interview.

Dr. García-Zamora, also the coordinator of the International Society of Electrocardiology Young Community, noted the particularly high numbers of reports among young health care workers and women.

“Unfortunately, young women seem to be the most vulnerable staff to suffering violence, regardless of the work they perform in the health system,” he said. “Notably, less than one in four health team members that suffered workplace violence pursued legal action based on the events.”

The research team is now conducting additional analyses on the different types of aggression based on gender, region, and task performed by the health care team. They’re trying to understand who is most vulnerable to physical attacks, as well as the consequences.

“The most important thing to highlight is that this problem exists, it is more frequent than we think, and we can only solve it if we all get involved in it,” Dr. García-Zamora said.

‘Complete systematic failure’

Health care workers in certain communities faced more aggression as well. In a CMAJ Open study published in November 2021, Asian Canadian and Asian American health care workers experienced discrimination, racial microaggressions, threats of violence, and violent acts during the pandemic. Women and frontline workers with direct patient contact were more likely to face verbal and physical abuse.

“This highlights that we need to continue the fight against misogyny, racism, and health care worker discrimination,” lead study author Zhida Shang, a medical student at McGill University, Montreal, told this news organization.

“As we are managing to live with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to study our successes and shortcomings. I sincerely believe that during the pandemic, the treatment of various racialized communities, including Asian Americans and Asian Canadians, was a complete systematic failure,” he said. “It is crucial to continue to examine, reflect, and learn from these lessons so that there will be equitable outcomes during the next public health emergency.”

The study was conducted without funding support. Dr. Baranchuk, Dr. García-Zamora, and Ms. Shang report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After an aggressive event or abuse occurred, 56% of providers considered changing their care tasks, and more than a third considered quitting their profession.

“Aggression of any sort against health care providers is not a new social phenomenon, and it has existed as far as medicine and health care is reported in literature. However, the phenomenon of aggression against health care providers during the pandemic grew worse,” senior study author Adrian Baranchuk, MD, a professor of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., told this news organization.

The study was published online in Current Problems in Cardiology

Survey snapshot

Dr. Baranchuk and colleagues, with the support of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology, developed a survey to characterize the frequency and types of abuse that frontline health professionals faced. They invited health care professionals from Latin America who had provided care since March 2020 to participate.

Between January and February 2022, 3,544 participants from 19 countries took the survey. Among them, 70.8% were physicians, 16% were nurses, and 13.2% were other health team members, such as administrative staff and technicians. About 58.5% were women, and 74.7% provided direct care to patients with COVID-19.

Overall, 54.8% of respondents reported acts of aggression. Of this group, 95.6% reported verbal abuse, 11.1% reported physical abuse, and 19.9% reported other types of abuse, including microaggressions.

About 13% of respondents reported experiencing some form of aggression daily, 26.4% experienced abuse weekly, and 38.8% reported violence a few times per month. Typically, the incidents involved patients’ relatives or both the patients and their relatives.

Nearly half of those who reported abuse experienced psychosomatic symptoms after the event, and 12% sought psychological care.

Administrative staff were 3.5 times more likely to experience abuse than other health care workers. Doctors and nurses were about twice as likely to experience abuse.

In addition, women, younger staff, and those who worked directly with COVID-19 patients were more likely to report abuse.

‘Shocking results’

Dr. Baranchuk, a native of Argentina, said people initially celebrated doctors and nurses for keeping communities safe. In several countries across Latin America, for instance, people lit candles, applauded at certain hours, and posted support on social media. As pandemic-related policies changed, however, health care providers faced unrest as people grew tired of wearing masks, maintaining social distance, and obeying restrictions at public spaces such as clubs and restaurants.

“This fatigue toward the social changes grew, but people didn’t have a specific target, and slowly and gradually, health care providers became the target of frustration and hate,” said Dr. Baranchuk. “In areas of the world where legislation is more flexible and less strict in charging individuals with poor or unacceptable behavior toward members of the health care team, aggression and microaggression became more frequent.”

“The results we obtained were more shocking than we expected,” Sebastián García-Zamora, MD, the lead study author and head of the coronary care unit at the Delta Clinic, Buenos Aires, said in an interview.

Dr. García-Zamora, also the coordinator of the International Society of Electrocardiology Young Community, noted the particularly high numbers of reports among young health care workers and women.

“Unfortunately, young women seem to be the most vulnerable staff to suffering violence, regardless of the work they perform in the health system,” he said. “Notably, less than one in four health team members that suffered workplace violence pursued legal action based on the events.”

The research team is now conducting additional analyses on the different types of aggression based on gender, region, and task performed by the health care team. They’re trying to understand who is most vulnerable to physical attacks, as well as the consequences.

“The most important thing to highlight is that this problem exists, it is more frequent than we think, and we can only solve it if we all get involved in it,” Dr. García-Zamora said.

‘Complete systematic failure’

Health care workers in certain communities faced more aggression as well. In a CMAJ Open study published in November 2021, Asian Canadian and Asian American health care workers experienced discrimination, racial microaggressions, threats of violence, and violent acts during the pandemic. Women and frontline workers with direct patient contact were more likely to face verbal and physical abuse.

“This highlights that we need to continue the fight against misogyny, racism, and health care worker discrimination,” lead study author Zhida Shang, a medical student at McGill University, Montreal, told this news organization.

“As we are managing to live with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to study our successes and shortcomings. I sincerely believe that during the pandemic, the treatment of various racialized communities, including Asian Americans and Asian Canadians, was a complete systematic failure,” he said. “It is crucial to continue to examine, reflect, and learn from these lessons so that there will be equitable outcomes during the next public health emergency.”

The study was conducted without funding support. Dr. Baranchuk, Dr. García-Zamora, and Ms. Shang report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After an aggressive event or abuse occurred, 56% of providers considered changing their care tasks, and more than a third considered quitting their profession.

“Aggression of any sort against health care providers is not a new social phenomenon, and it has existed as far as medicine and health care is reported in literature. However, the phenomenon of aggression against health care providers during the pandemic grew worse,” senior study author Adrian Baranchuk, MD, a professor of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., told this news organization.

The study was published online in Current Problems in Cardiology

Survey snapshot

Dr. Baranchuk and colleagues, with the support of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology, developed a survey to characterize the frequency and types of abuse that frontline health professionals faced. They invited health care professionals from Latin America who had provided care since March 2020 to participate.

Between January and February 2022, 3,544 participants from 19 countries took the survey. Among them, 70.8% were physicians, 16% were nurses, and 13.2% were other health team members, such as administrative staff and technicians. About 58.5% were women, and 74.7% provided direct care to patients with COVID-19.

Overall, 54.8% of respondents reported acts of aggression. Of this group, 95.6% reported verbal abuse, 11.1% reported physical abuse, and 19.9% reported other types of abuse, including microaggressions.

About 13% of respondents reported experiencing some form of aggression daily, 26.4% experienced abuse weekly, and 38.8% reported violence a few times per month. Typically, the incidents involved patients’ relatives or both the patients and their relatives.

Nearly half of those who reported abuse experienced psychosomatic symptoms after the event, and 12% sought psychological care.

Administrative staff were 3.5 times more likely to experience abuse than other health care workers. Doctors and nurses were about twice as likely to experience abuse.

In addition, women, younger staff, and those who worked directly with COVID-19 patients were more likely to report abuse.

‘Shocking results’

Dr. Baranchuk, a native of Argentina, said people initially celebrated doctors and nurses for keeping communities safe. In several countries across Latin America, for instance, people lit candles, applauded at certain hours, and posted support on social media. As pandemic-related policies changed, however, health care providers faced unrest as people grew tired of wearing masks, maintaining social distance, and obeying restrictions at public spaces such as clubs and restaurants.

“This fatigue toward the social changes grew, but people didn’t have a specific target, and slowly and gradually, health care providers became the target of frustration and hate,” said Dr. Baranchuk. “In areas of the world where legislation is more flexible and less strict in charging individuals with poor or unacceptable behavior toward members of the health care team, aggression and microaggression became more frequent.”

“The results we obtained were more shocking than we expected,” Sebastián García-Zamora, MD, the lead study author and head of the coronary care unit at the Delta Clinic, Buenos Aires, said in an interview.

Dr. García-Zamora, also the coordinator of the International Society of Electrocardiology Young Community, noted the particularly high numbers of reports among young health care workers and women.

“Unfortunately, young women seem to be the most vulnerable staff to suffering violence, regardless of the work they perform in the health system,” he said. “Notably, less than one in four health team members that suffered workplace violence pursued legal action based on the events.”

The research team is now conducting additional analyses on the different types of aggression based on gender, region, and task performed by the health care team. They’re trying to understand who is most vulnerable to physical attacks, as well as the consequences.

“The most important thing to highlight is that this problem exists, it is more frequent than we think, and we can only solve it if we all get involved in it,” Dr. García-Zamora said.

‘Complete systematic failure’

Health care workers in certain communities faced more aggression as well. In a CMAJ Open study published in November 2021, Asian Canadian and Asian American health care workers experienced discrimination, racial microaggressions, threats of violence, and violent acts during the pandemic. Women and frontline workers with direct patient contact were more likely to face verbal and physical abuse.

“This highlights that we need to continue the fight against misogyny, racism, and health care worker discrimination,” lead study author Zhida Shang, a medical student at McGill University, Montreal, told this news organization.

“As we are managing to live with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to study our successes and shortcomings. I sincerely believe that during the pandemic, the treatment of various racialized communities, including Asian Americans and Asian Canadians, was a complete systematic failure,” he said. “It is crucial to continue to examine, reflect, and learn from these lessons so that there will be equitable outcomes during the next public health emergency.”

The study was conducted without funding support. Dr. Baranchuk, Dr. García-Zamora, and Ms. Shang report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Inflation and health care: The prognosis for doctors

Rampant inflation doesn’t just mean a spike in everyday expenses like gas and groceries. It’s also bound to have a significant impact on the cost of health care – and on your practice. A recent report from McKinsey & Company predicts that the current inflationary spiral will force health care providers to charge higher reimbursement rates, and those costs inevitably will be passed along to both employers and consumers. Bottom line: Your patients will likely have to pay more out of pocket.

How, precisely, will inflation affect your practice, and what’s the best way to minimize the damage?

Step 1: Maintain operational standards

“Based on the conversations we’ve had with our physician clients that own practices, we see the potential for cost inflation to outrun revenue inflation over the next year,” said Michael Ashley Schulman, CFA, partner and chief investment officer at Running Point Capital, El Segundo, Calif. “Staff wages, as well as office equipment and medical supply costs, are increasing faster than insurance and Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement amounts.” Even so, topflight employees are essential to keep your practice running smoothly. Prioritize excellent nursing. Instead of adding a new hire, compensate your best nurse as well as possible. The same goes for an efficient office manager: On that front, too, you should go the extra mile, even if it means trimming expenses elsewhere.

Step 2: Plan ahead for insurance challenges

Many insurers, including Medicare, set health care costs a year in advance, based on projected growth. This means insurance payouts will stay largely the same for the time being. “Almost all physicians employed by large groups won’t see costs due to inflation rise until next year,” said Mark V. Pauly, PhD, Bendheim Professor in the department of health care management at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “For self-employed physicians, there will also be a cushion.”

“The big issue with inflation is that more patients will likely be underinsured,” said Tiffany Johnson, MBA, CFP, co-CEO and financial advisor at Piece of Wealth Planning in Atlanta. “With more out-of-pocket costs ... these patients may not seek out medical treatment or go to see a specialist if they do not believe it is necessary.” A new study from Johns Hopkins found that patients under financial pressure often delay or forgo medical treatment because of food insecurity. Compassionate care is the solution: Direct these patients to financial aid and other resources they may qualify for. That way, they can continue to receive the care they need from you, and your need to pass on costs may be lower.

Step 3: Rely on your affiliated health care organization

These are tough times when it comes to expansion. “Since we are in an environment where inflation and interest rates are both high, it will be much harder for physicians to have the capital to invest in new technology to grow or advance their practice,” Ms. Johnson said. With that in mind, keep the lines of communication between you and your affiliated hospital/health care organization more open than ever. Combining practices with another doctor is one way to increase revenue; you might ask if any affiliated doctors are seeking to team up. It’s also vital to attend meetings and pay close attention to budget cuts your organization may be making. And don’t be shy about asking your administrator for profit-boosting recommendations.

Step 4: Revisit vendor relationships

Find out if your vendors will continue to supply you with the goods you need at reasonable rates, and switch now if they won’t. Be proactive. “Test new medical suppliers,” Mr. Schulman advised. “Reread equipment leasing contracts to check if the interest rates have increased. See if buyout, prepay, or refinancing options are more economical. Also, investigate [bringing down] your rental expense by reducing square footage or moving to a lower-cost location.” In light of ongoing supply chain issues, it’s wise to consider alternative products. But stay focused on quality – you don’t want to be stuck with cheap, possibly defective equipment. Spend where it’s essential and cut the fat somewhere else.

Step 5: Don’t waste your assets

Analyze your budget in minute detail. “Now is the time to review your current inventory and overhead costs,” Ms. Johnson said. “Many physicians let their office staff handle the restocking of inventory and office supplies. While this can be efficient for their practice, it also leaves room for unnecessary business expenses.” Take a cold, hard look at your supply closet – what’s in there that you can live without? Don’t reorder it. Then seek out any revenue stream you may be overlooking. “It’s important to review billing to make sure all the services are reimbursable,” Ms. Johnson added. Small mistakes can yield dividends if you find them.

Step 6: Be poised to pivot

Get creative. “To minimize a profit decline, use video consulting – it’s more efficient and less equipment intensive,” Mr. Schulman said. “Look at how remote work and flexible hours can maximize the work your practice accomplishes while cutting office costs.”

Ms. Johnson suggests adding concierge services, noting that “concierge doctors offer personalized care and direct access for an up-front fee.” With this approach, you may see fewer patients, but your payout paperwork will decrease, and that up-front fee can be profitable. Another outside-the-box idea: Start making house calls. A Scripps study found that home health visits requested via app can result in patient care delivered by a doctor and medical assistant in less than 2 hours. House calls can be an effective and profitable solution when it comes to providing nonemergency care and preventive treatment to patients who aren’t mobile, not to mention patients who just appreciate the convenience.

Step 7: Maintain transparency

Any economic changes your practice will implement must be communicated to your staff and patients clearly and directly. Keep everyone in the loop and be ready to answer questions immediately. Show those you work with and care for that, regardless of the economy, it’s they who matter to you most. That simple reassurance will prove invaluable.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rampant inflation doesn’t just mean a spike in everyday expenses like gas and groceries. It’s also bound to have a significant impact on the cost of health care – and on your practice. A recent report from McKinsey & Company predicts that the current inflationary spiral will force health care providers to charge higher reimbursement rates, and those costs inevitably will be passed along to both employers and consumers. Bottom line: Your patients will likely have to pay more out of pocket.

How, precisely, will inflation affect your practice, and what’s the best way to minimize the damage?

Step 1: Maintain operational standards

“Based on the conversations we’ve had with our physician clients that own practices, we see the potential for cost inflation to outrun revenue inflation over the next year,” said Michael Ashley Schulman, CFA, partner and chief investment officer at Running Point Capital, El Segundo, Calif. “Staff wages, as well as office equipment and medical supply costs, are increasing faster than insurance and Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement amounts.” Even so, topflight employees are essential to keep your practice running smoothly. Prioritize excellent nursing. Instead of adding a new hire, compensate your best nurse as well as possible. The same goes for an efficient office manager: On that front, too, you should go the extra mile, even if it means trimming expenses elsewhere.

Step 2: Plan ahead for insurance challenges

Many insurers, including Medicare, set health care costs a year in advance, based on projected growth. This means insurance payouts will stay largely the same for the time being. “Almost all physicians employed by large groups won’t see costs due to inflation rise until next year,” said Mark V. Pauly, PhD, Bendheim Professor in the department of health care management at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “For self-employed physicians, there will also be a cushion.”

“The big issue with inflation is that more patients will likely be underinsured,” said Tiffany Johnson, MBA, CFP, co-CEO and financial advisor at Piece of Wealth Planning in Atlanta. “With more out-of-pocket costs ... these patients may not seek out medical treatment or go to see a specialist if they do not believe it is necessary.” A new study from Johns Hopkins found that patients under financial pressure often delay or forgo medical treatment because of food insecurity. Compassionate care is the solution: Direct these patients to financial aid and other resources they may qualify for. That way, they can continue to receive the care they need from you, and your need to pass on costs may be lower.

Step 3: Rely on your affiliated health care organization

These are tough times when it comes to expansion. “Since we are in an environment where inflation and interest rates are both high, it will be much harder for physicians to have the capital to invest in new technology to grow or advance their practice,” Ms. Johnson said. With that in mind, keep the lines of communication between you and your affiliated hospital/health care organization more open than ever. Combining practices with another doctor is one way to increase revenue; you might ask if any affiliated doctors are seeking to team up. It’s also vital to attend meetings and pay close attention to budget cuts your organization may be making. And don’t be shy about asking your administrator for profit-boosting recommendations.

Step 4: Revisit vendor relationships

Find out if your vendors will continue to supply you with the goods you need at reasonable rates, and switch now if they won’t. Be proactive. “Test new medical suppliers,” Mr. Schulman advised. “Reread equipment leasing contracts to check if the interest rates have increased. See if buyout, prepay, or refinancing options are more economical. Also, investigate [bringing down] your rental expense by reducing square footage or moving to a lower-cost location.” In light of ongoing supply chain issues, it’s wise to consider alternative products. But stay focused on quality – you don’t want to be stuck with cheap, possibly defective equipment. Spend where it’s essential and cut the fat somewhere else.

Step 5: Don’t waste your assets

Analyze your budget in minute detail. “Now is the time to review your current inventory and overhead costs,” Ms. Johnson said. “Many physicians let their office staff handle the restocking of inventory and office supplies. While this can be efficient for their practice, it also leaves room for unnecessary business expenses.” Take a cold, hard look at your supply closet – what’s in there that you can live without? Don’t reorder it. Then seek out any revenue stream you may be overlooking. “It’s important to review billing to make sure all the services are reimbursable,” Ms. Johnson added. Small mistakes can yield dividends if you find them.

Step 6: Be poised to pivot

Get creative. “To minimize a profit decline, use video consulting – it’s more efficient and less equipment intensive,” Mr. Schulman said. “Look at how remote work and flexible hours can maximize the work your practice accomplishes while cutting office costs.”

Ms. Johnson suggests adding concierge services, noting that “concierge doctors offer personalized care and direct access for an up-front fee.” With this approach, you may see fewer patients, but your payout paperwork will decrease, and that up-front fee can be profitable. Another outside-the-box idea: Start making house calls. A Scripps study found that home health visits requested via app can result in patient care delivered by a doctor and medical assistant in less than 2 hours. House calls can be an effective and profitable solution when it comes to providing nonemergency care and preventive treatment to patients who aren’t mobile, not to mention patients who just appreciate the convenience.

Step 7: Maintain transparency

Any economic changes your practice will implement must be communicated to your staff and patients clearly and directly. Keep everyone in the loop and be ready to answer questions immediately. Show those you work with and care for that, regardless of the economy, it’s they who matter to you most. That simple reassurance will prove invaluable.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rampant inflation doesn’t just mean a spike in everyday expenses like gas and groceries. It’s also bound to have a significant impact on the cost of health care – and on your practice. A recent report from McKinsey & Company predicts that the current inflationary spiral will force health care providers to charge higher reimbursement rates, and those costs inevitably will be passed along to both employers and consumers. Bottom line: Your patients will likely have to pay more out of pocket.

How, precisely, will inflation affect your practice, and what’s the best way to minimize the damage?

Step 1: Maintain operational standards

“Based on the conversations we’ve had with our physician clients that own practices, we see the potential for cost inflation to outrun revenue inflation over the next year,” said Michael Ashley Schulman, CFA, partner and chief investment officer at Running Point Capital, El Segundo, Calif. “Staff wages, as well as office equipment and medical supply costs, are increasing faster than insurance and Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement amounts.” Even so, topflight employees are essential to keep your practice running smoothly. Prioritize excellent nursing. Instead of adding a new hire, compensate your best nurse as well as possible. The same goes for an efficient office manager: On that front, too, you should go the extra mile, even if it means trimming expenses elsewhere.

Step 2: Plan ahead for insurance challenges

Many insurers, including Medicare, set health care costs a year in advance, based on projected growth. This means insurance payouts will stay largely the same for the time being. “Almost all physicians employed by large groups won’t see costs due to inflation rise until next year,” said Mark V. Pauly, PhD, Bendheim Professor in the department of health care management at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “For self-employed physicians, there will also be a cushion.”

“The big issue with inflation is that more patients will likely be underinsured,” said Tiffany Johnson, MBA, CFP, co-CEO and financial advisor at Piece of Wealth Planning in Atlanta. “With more out-of-pocket costs ... these patients may not seek out medical treatment or go to see a specialist if they do not believe it is necessary.” A new study from Johns Hopkins found that patients under financial pressure often delay or forgo medical treatment because of food insecurity. Compassionate care is the solution: Direct these patients to financial aid and other resources they may qualify for. That way, they can continue to receive the care they need from you, and your need to pass on costs may be lower.

Step 3: Rely on your affiliated health care organization

These are tough times when it comes to expansion. “Since we are in an environment where inflation and interest rates are both high, it will be much harder for physicians to have the capital to invest in new technology to grow or advance their practice,” Ms. Johnson said. With that in mind, keep the lines of communication between you and your affiliated hospital/health care organization more open than ever. Combining practices with another doctor is one way to increase revenue; you might ask if any affiliated doctors are seeking to team up. It’s also vital to attend meetings and pay close attention to budget cuts your organization may be making. And don’t be shy about asking your administrator for profit-boosting recommendations.

Step 4: Revisit vendor relationships

Find out if your vendors will continue to supply you with the goods you need at reasonable rates, and switch now if they won’t. Be proactive. “Test new medical suppliers,” Mr. Schulman advised. “Reread equipment leasing contracts to check if the interest rates have increased. See if buyout, prepay, or refinancing options are more economical. Also, investigate [bringing down] your rental expense by reducing square footage or moving to a lower-cost location.” In light of ongoing supply chain issues, it’s wise to consider alternative products. But stay focused on quality – you don’t want to be stuck with cheap, possibly defective equipment. Spend where it’s essential and cut the fat somewhere else.

Step 5: Don’t waste your assets

Analyze your budget in minute detail. “Now is the time to review your current inventory and overhead costs,” Ms. Johnson said. “Many physicians let their office staff handle the restocking of inventory and office supplies. While this can be efficient for their practice, it also leaves room for unnecessary business expenses.” Take a cold, hard look at your supply closet – what’s in there that you can live without? Don’t reorder it. Then seek out any revenue stream you may be overlooking. “It’s important to review billing to make sure all the services are reimbursable,” Ms. Johnson added. Small mistakes can yield dividends if you find them.

Step 6: Be poised to pivot

Get creative. “To minimize a profit decline, use video consulting – it’s more efficient and less equipment intensive,” Mr. Schulman said. “Look at how remote work and flexible hours can maximize the work your practice accomplishes while cutting office costs.”

Ms. Johnson suggests adding concierge services, noting that “concierge doctors offer personalized care and direct access for an up-front fee.” With this approach, you may see fewer patients, but your payout paperwork will decrease, and that up-front fee can be profitable. Another outside-the-box idea: Start making house calls. A Scripps study found that home health visits requested via app can result in patient care delivered by a doctor and medical assistant in less than 2 hours. House calls can be an effective and profitable solution when it comes to providing nonemergency care and preventive treatment to patients who aren’t mobile, not to mention patients who just appreciate the convenience.

Step 7: Maintain transparency

Any economic changes your practice will implement must be communicated to your staff and patients clearly and directly. Keep everyone in the loop and be ready to answer questions immediately. Show those you work with and care for that, regardless of the economy, it’s they who matter to you most. That simple reassurance will prove invaluable.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Do behavioral interventions improve nighttime sleep in children < 1 year old?

Most interventions resulted in at least modest improvements in sleep

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 279 newborn infants and their mothers evaluated developmentally appropriate sleep interventions.1 Mothers were given guidance on bedtime sleep routines, including starting the routine 30 to 45 minutes before bedtime, choosing age-appropriate calming bedtime activities, not using feeding as the last step before bedtime, and offering the child choices with their routine. Mothers were also given guidance on sleep location and behaviors, including recommendations on the best bedtime (between 7 and 8

These interventions were compared to a control group that received instructions on crib safety, sudden infant death syndrome prevention, and other sleep safety recommendations. Infant nocturnal sleep duration was determined by maternal report using the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire (BISQ). After 40 weeks, infants in the intervention group demonstrated longer sleep duration than did those in the control group (624.6 ± 67.6 minutes vs 602.9 ± 76.1 minutes; P = .01).1

An RCT of 82 infants (ages 2-4 months) and their mothers evaluated the effect of behavioral sleep interventions on maternal and infant sleep.2 Parents were offered either a 90-minute class and take-home booklet about behavioral sleep interventions or a 30-minute training on general infant safety with an accompanying pamphlet.

The behavioral interventions booklet included instructions on differentiating day and night routines for baby, avoiding digital devices and television in the evenings, playing more active games in the morning, dimming lights and reducing house noises in the afternoon, and having a consistent nighttime routine with consistent bedtime and sleep space. Participants completed an infant sleep diary prior to the intervention and repeated the sleep diary 8 weeks after the intervention. The infants whose mothers received the education on behavioral sleep interventions demonstrated an increase in nighttime sleep duration when compared to the control group (7.4 to 8.8 hours vs 7.3 to 7.5 hours; ANCOVA P < .001).

An RCT of 235 families with infants ages 6 to 8 months evaluated the effect of 45 minutes of nurse-provided education regarding normal infant sleep, effects of inadequate sleep, setting limits around infant sleep, importance of daytime routines, and negative sleep associations combined with a booklet and weekly phone follow-ups.3 This intervention was compared to routine infant education. At age 6 weeks, infants were monitored for 48 hours with actigraphy and the mothers completed a sleep diary to correlate activities. There was no difference in average nightly waking (2 nightly wakes; risk difference = –0.2%; 95% CI, –1.32 to 0.91).

An RCT of 268 families with infants (ages 2-3 weeks) evaluated the effect of 45 minutes of nurse-provided education on behavioral sleep interventions including the cyclical nature of infant sleep, environmental factors that influence sleep, and parent-independent sleep cues (eg, leaving a settling infant alone for 5 minutes before responding) combined with written information.4 This was compared to infants receiving standard care without parental sleep intervention education. Participants recorded sleep diaries for 7 days when their infant reached age 6 weeks and again at age 12 weeks. At both 6 weeks and 12 weeks, there was a significant increase in infant nocturnal sleep time in the intervention group vs the control group (mean difference [MD] at 6 weeks = 0.5 hours; 95% CI, 0.32 to 0.69 vs MD at 12 weeks = 0.64 hours; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.89).

A nonrandomized controlled trial with 84 mothers and infants (ages 0-6 months) evaluated the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention involving brief focused negotiation by pediatricians, motivational counseling by a health educator, and group parenting workshops, compared to mother–infant pairs receiving standard care.5 Parents completed the BISQ at 0 and 6 months to assess nocturnal sleep duration. At 6 months, the intervention group had a significantly higher increase in infant nocturnal sleep duration compared to the control group (mean increase = 1.9 vs 1.3 hours; P = .05).

In a prospective cohort study involving 79 infants (ages 3-24 months) with parent- or pediatrician-reported day and night sleep problems, parents were given education on the promotion of nighttime sleep by gradually reducing contact with the infant over several nights and only leaving the room after the infant fell asleep or allowing the child to self-soothe for 1-3 minutes.6 The intervention was performed over 3 weeks, with in-person follow-up performed on Day 15 and phone follow-up on Days 8 and 21. Infants in this study demonstrated an increase in the average hours of total night sleep from 10.2 to 10.5 hours (P < .001).

Editor’s takeaway

Providing behavioral recommendations to parents about infant sleep routines improves sleep duration. This increased sleep duration, and the supporting evidence, is modest, but the low cost and risk of these interventions make them worthwhile.

1. Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman-Frasca S, et al. INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention and infant sleep. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160762. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0762

2. Rouzafzoon M, Farnam F, Khakbazan Z. The effects of infant behavioural sleep interventions on maternal sleep and mood, and infant sleep: a randomised controlled trial. J Sleep Res. 2021;30:e13344. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13344

3. Hall WA, Hutton E, Brant RF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an intervention for infants’ behavioral sleep problems. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:181. doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0492-7

4. Symon BG, Marley JE, Martin AJ, et al. Effect of a consultation teaching behaviour modification on sleep performance in infants: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2005;182:215-218. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06669.x

5. Taveras EM, Blackburn K, Gillman MW, et al. First steps for mommy and me: a pilot intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors of postpartum mothers and their infants. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1217-1227. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0696-2

6. Skuladottir A, Thome M, Ramel A. Improving day and night sleep problems in infants by changing day time sleep rhythm: a single group before and after study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:843-850. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.12.004

Most interventions resulted in at least modest improvements in sleep

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 279 newborn infants and their mothers evaluated developmentally appropriate sleep interventions.1 Mothers were given guidance on bedtime sleep routines, including starting the routine 30 to 45 minutes before bedtime, choosing age-appropriate calming bedtime activities, not using feeding as the last step before bedtime, and offering the child choices with their routine. Mothers were also given guidance on sleep location and behaviors, including recommendations on the best bedtime (between 7 and 8

These interventions were compared to a control group that received instructions on crib safety, sudden infant death syndrome prevention, and other sleep safety recommendations. Infant nocturnal sleep duration was determined by maternal report using the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire (BISQ). After 40 weeks, infants in the intervention group demonstrated longer sleep duration than did those in the control group (624.6 ± 67.6 minutes vs 602.9 ± 76.1 minutes; P = .01).1

An RCT of 82 infants (ages 2-4 months) and their mothers evaluated the effect of behavioral sleep interventions on maternal and infant sleep.2 Parents were offered either a 90-minute class and take-home booklet about behavioral sleep interventions or a 30-minute training on general infant safety with an accompanying pamphlet.

The behavioral interventions booklet included instructions on differentiating day and night routines for baby, avoiding digital devices and television in the evenings, playing more active games in the morning, dimming lights and reducing house noises in the afternoon, and having a consistent nighttime routine with consistent bedtime and sleep space. Participants completed an infant sleep diary prior to the intervention and repeated the sleep diary 8 weeks after the intervention. The infants whose mothers received the education on behavioral sleep interventions demonstrated an increase in nighttime sleep duration when compared to the control group (7.4 to 8.8 hours vs 7.3 to 7.5 hours; ANCOVA P < .001).

An RCT of 235 families with infants ages 6 to 8 months evaluated the effect of 45 minutes of nurse-provided education regarding normal infant sleep, effects of inadequate sleep, setting limits around infant sleep, importance of daytime routines, and negative sleep associations combined with a booklet and weekly phone follow-ups.3 This intervention was compared to routine infant education. At age 6 weeks, infants were monitored for 48 hours with actigraphy and the mothers completed a sleep diary to correlate activities. There was no difference in average nightly waking (2 nightly wakes; risk difference = –0.2%; 95% CI, –1.32 to 0.91).

An RCT of 268 families with infants (ages 2-3 weeks) evaluated the effect of 45 minutes of nurse-provided education on behavioral sleep interventions including the cyclical nature of infant sleep, environmental factors that influence sleep, and parent-independent sleep cues (eg, leaving a settling infant alone for 5 minutes before responding) combined with written information.4 This was compared to infants receiving standard care without parental sleep intervention education. Participants recorded sleep diaries for 7 days when their infant reached age 6 weeks and again at age 12 weeks. At both 6 weeks and 12 weeks, there was a significant increase in infant nocturnal sleep time in the intervention group vs the control group (mean difference [MD] at 6 weeks = 0.5 hours; 95% CI, 0.32 to 0.69 vs MD at 12 weeks = 0.64 hours; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.89).

A nonrandomized controlled trial with 84 mothers and infants (ages 0-6 months) evaluated the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention involving brief focused negotiation by pediatricians, motivational counseling by a health educator, and group parenting workshops, compared to mother–infant pairs receiving standard care.5 Parents completed the BISQ at 0 and 6 months to assess nocturnal sleep duration. At 6 months, the intervention group had a significantly higher increase in infant nocturnal sleep duration compared to the control group (mean increase = 1.9 vs 1.3 hours; P = .05).

In a prospective cohort study involving 79 infants (ages 3-24 months) with parent- or pediatrician-reported day and night sleep problems, parents were given education on the promotion of nighttime sleep by gradually reducing contact with the infant over several nights and only leaving the room after the infant fell asleep or allowing the child to self-soothe for 1-3 minutes.6 The intervention was performed over 3 weeks, with in-person follow-up performed on Day 15 and phone follow-up on Days 8 and 21. Infants in this study demonstrated an increase in the average hours of total night sleep from 10.2 to 10.5 hours (P < .001).

Editor’s takeaway

Providing behavioral recommendations to parents about infant sleep routines improves sleep duration. This increased sleep duration, and the supporting evidence, is modest, but the low cost and risk of these interventions make them worthwhile.

Most interventions resulted in at least modest improvements in sleep

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 279 newborn infants and their mothers evaluated developmentally appropriate sleep interventions.1 Mothers were given guidance on bedtime sleep routines, including starting the routine 30 to 45 minutes before bedtime, choosing age-appropriate calming bedtime activities, not using feeding as the last step before bedtime, and offering the child choices with their routine. Mothers were also given guidance on sleep location and behaviors, including recommendations on the best bedtime (between 7 and 8

These interventions were compared to a control group that received instructions on crib safety, sudden infant death syndrome prevention, and other sleep safety recommendations. Infant nocturnal sleep duration was determined by maternal report using the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire (BISQ). After 40 weeks, infants in the intervention group demonstrated longer sleep duration than did those in the control group (624.6 ± 67.6 minutes vs 602.9 ± 76.1 minutes; P = .01).1

An RCT of 82 infants (ages 2-4 months) and their mothers evaluated the effect of behavioral sleep interventions on maternal and infant sleep.2 Parents were offered either a 90-minute class and take-home booklet about behavioral sleep interventions or a 30-minute training on general infant safety with an accompanying pamphlet.

The behavioral interventions booklet included instructions on differentiating day and night routines for baby, avoiding digital devices and television in the evenings, playing more active games in the morning, dimming lights and reducing house noises in the afternoon, and having a consistent nighttime routine with consistent bedtime and sleep space. Participants completed an infant sleep diary prior to the intervention and repeated the sleep diary 8 weeks after the intervention. The infants whose mothers received the education on behavioral sleep interventions demonstrated an increase in nighttime sleep duration when compared to the control group (7.4 to 8.8 hours vs 7.3 to 7.5 hours; ANCOVA P < .001).

An RCT of 235 families with infants ages 6 to 8 months evaluated the effect of 45 minutes of nurse-provided education regarding normal infant sleep, effects of inadequate sleep, setting limits around infant sleep, importance of daytime routines, and negative sleep associations combined with a booklet and weekly phone follow-ups.3 This intervention was compared to routine infant education. At age 6 weeks, infants were monitored for 48 hours with actigraphy and the mothers completed a sleep diary to correlate activities. There was no difference in average nightly waking (2 nightly wakes; risk difference = –0.2%; 95% CI, –1.32 to 0.91).

An RCT of 268 families with infants (ages 2-3 weeks) evaluated the effect of 45 minutes of nurse-provided education on behavioral sleep interventions including the cyclical nature of infant sleep, environmental factors that influence sleep, and parent-independent sleep cues (eg, leaving a settling infant alone for 5 minutes before responding) combined with written information.4 This was compared to infants receiving standard care without parental sleep intervention education. Participants recorded sleep diaries for 7 days when their infant reached age 6 weeks and again at age 12 weeks. At both 6 weeks and 12 weeks, there was a significant increase in infant nocturnal sleep time in the intervention group vs the control group (mean difference [MD] at 6 weeks = 0.5 hours; 95% CI, 0.32 to 0.69 vs MD at 12 weeks = 0.64 hours; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.89).

A nonrandomized controlled trial with 84 mothers and infants (ages 0-6 months) evaluated the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention involving brief focused negotiation by pediatricians, motivational counseling by a health educator, and group parenting workshops, compared to mother–infant pairs receiving standard care.5 Parents completed the BISQ at 0 and 6 months to assess nocturnal sleep duration. At 6 months, the intervention group had a significantly higher increase in infant nocturnal sleep duration compared to the control group (mean increase = 1.9 vs 1.3 hours; P = .05).

In a prospective cohort study involving 79 infants (ages 3-24 months) with parent- or pediatrician-reported day and night sleep problems, parents were given education on the promotion of nighttime sleep by gradually reducing contact with the infant over several nights and only leaving the room after the infant fell asleep or allowing the child to self-soothe for 1-3 minutes.6 The intervention was performed over 3 weeks, with in-person follow-up performed on Day 15 and phone follow-up on Days 8 and 21. Infants in this study demonstrated an increase in the average hours of total night sleep from 10.2 to 10.5 hours (P < .001).

Editor’s takeaway

Providing behavioral recommendations to parents about infant sleep routines improves sleep duration. This increased sleep duration, and the supporting evidence, is modest, but the low cost and risk of these interventions make them worthwhile.

1. Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman-Frasca S, et al. INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention and infant sleep. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160762. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0762

2. Rouzafzoon M, Farnam F, Khakbazan Z. The effects of infant behavioural sleep interventions on maternal sleep and mood, and infant sleep: a randomised controlled trial. J Sleep Res. 2021;30:e13344. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13344

3. Hall WA, Hutton E, Brant RF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an intervention for infants’ behavioral sleep problems. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:181. doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0492-7

4. Symon BG, Marley JE, Martin AJ, et al. Effect of a consultation teaching behaviour modification on sleep performance in infants: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2005;182:215-218. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06669.x

5. Taveras EM, Blackburn K, Gillman MW, et al. First steps for mommy and me: a pilot intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors of postpartum mothers and their infants. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1217-1227. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0696-2

6. Skuladottir A, Thome M, Ramel A. Improving day and night sleep problems in infants by changing day time sleep rhythm: a single group before and after study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:843-850. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.12.004

1. Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman-Frasca S, et al. INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention and infant sleep. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160762. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0762

2. Rouzafzoon M, Farnam F, Khakbazan Z. The effects of infant behavioural sleep interventions on maternal sleep and mood, and infant sleep: a randomised controlled trial. J Sleep Res. 2021;30:e13344. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13344

3. Hall WA, Hutton E, Brant RF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an intervention for infants’ behavioral sleep problems. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:181. doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0492-7

4. Symon BG, Marley JE, Martin AJ, et al. Effect of a consultation teaching behaviour modification on sleep performance in infants: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2005;182:215-218. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06669.x

5. Taveras EM, Blackburn K, Gillman MW, et al. First steps for mommy and me: a pilot intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors of postpartum mothers and their infants. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1217-1227. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0696-2

6. Skuladottir A, Thome M, Ramel A. Improving day and night sleep problems in infants by changing day time sleep rhythm: a single group before and after study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:843-850. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.12.004

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

YES. Infants respond to behavioral interventions, although objective data are limited. Behavioral interventions include establishing regular daytime and sleep routines for the infant, reducing environmental noises or distractions, and allowing for self-soothing at bedtime (strength of recommendation: B, based on multiple randomized and nonrandomized studies).

Are antipsychotics effective adjunctive Tx for patients with moderate-to-severe depression?

Evidence summary

Depression symptoms improved with any of 4 antipsychotics

A 2021 systematic review of 16 RCTs (N = 3649) assessed data from trials that used an atypical antipsychotic—either aripiprazole, quetiapine, olanzapine, or risperidone—as augmentation therapy to an antidepressant vs placebo.1 Study participants included adults ages 18 to 65 who experienced an episode of depression and did not respond adequately to at least 1 optimally dosed antidepressant. In most studies, treatment-resistant depression (TRD) was defined as the failure of at least 1 major class of antidepressants. Trial lengths ranged from 4 to 12 weeks.

Six RCTs evaluated the effectiveness of augmentation with aripiprazole (2-20 mg/d) in patients with unipolar depression, with 5 trials demonstrating greater improvement in clinical symptoms with aripiprazole compared to placebo. Augmentation with quetiapine (150-300 mg/d) was evaluated in 5 trials, with all trials showing improvement in depression symptoms; however, in 1 trial the difference in remission rates was not significant, and in another trial significant improvement was seen only at a quetia-pine dose of 300 mg/d. Two trials examining olanzapine found that patients receiving fluoxetine plus olanzapine augmentation demonstrated greater improvement in depression symptoms than did those receiving either agent alone. Three trials examined augmentation with risperidone (0.5-3 mg/d); in all 3, risperidone demonstrated significant improvement in depression symptoms and remission rates compared to placebo.1

This systematic review was limited by small sample size and heterogeneity of antipsychotic dosages in the RCTs included, as well as the lack of a standardized and globally accepted definition of TRD.

Augmentation reduced symptom severity, but dropout rates were high