User login

Psoriatic Alopecia in a Patient With Crohn Disease: An Uncommon Manifestation of Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced psoriasis is a known paradoxical adverse effect of this family of medications, which includes infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and certolizumab. In the pediatric population, these therapies recently gained approval for nondermatologic conditions—meaning that this phenomenon is encountered more frequently.1 In a systematic review of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis, severe scalp involvement was associated with alopecia in 7.5% of cases.2 Onset of scalp psoriasis with alopecia in patients being treated with a TNF-α inhibitor should lead to consideration of this condition.

Psoriatic alopecia is an uncommon presentation of psoriasis. Although well described, alopecia as a clinical manifestation of scalp psoriasis is not a well-known concept among clinicians and has never been widely accepted. Adding to the diagnostic challenge is that psoriatic alopecia secondary to TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis rarely has been reported in adults or children.3-5 Including our case, our review of the literature yielded 7 pediatric cases (≤18 years) of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia.6,7 A primary literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms psoriatic alopecia, psoriasiform alopecia, TNF-α inhibitors, infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and certolizumab.

We present the case of a pediatric patient with psoriatic alopecia secondary to treatment with adalimumab for Crohn disease (CD). We also provide a review of reported cases of psoriatic alopecia induced by a TNF-α inhibitor in the literature.

Case Report

A 12-year-old girl presented to our dermatology clinic with erythematous scaly plaques on the trunk, scalp, arms, and legs of 2 months’ duration. The lesions involved approximately 15% of the body surface area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for CD diagnosed 4 years prior to presentation of the skin lesions. She had been treated for the past 2 years with adalimumab 40 mg once every 2 weeks and azathioprine 100 mg once daily. Because her CD was poorly controlled, the dosage of adalimumab was increased to 40 mg once weekly 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Our diagnosis was TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis secondary to treatment with adalimumab.

The patient was treated with mometasone lotion 0.1% for the scalp lesions and triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body lesions. Because of the extent of the psoriasis, we recommended changing adalimumab to ustekinumab, which is approved for CD in adults but is off label in children.

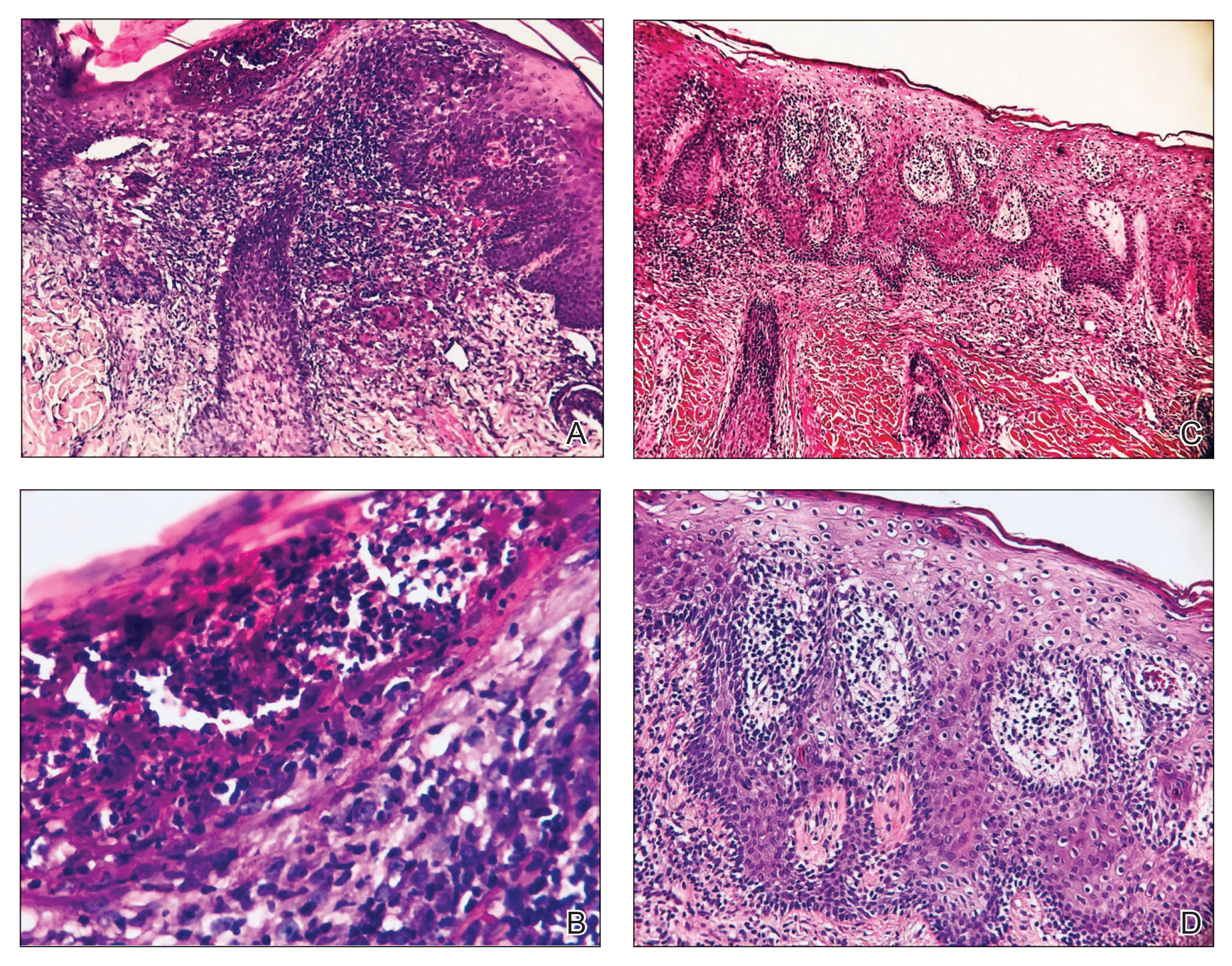

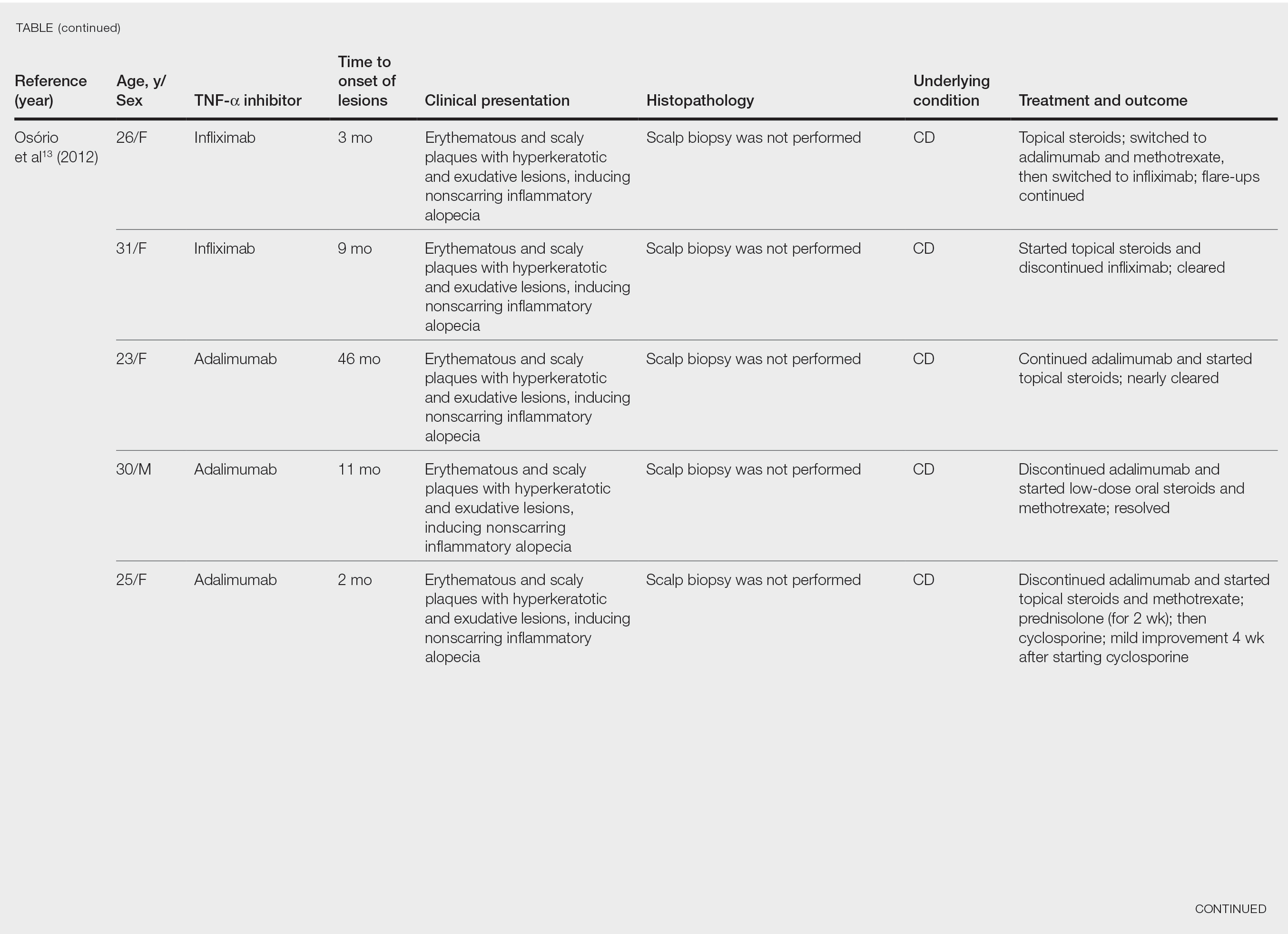

At 1-month follow-up, after receiving the induction dose of ustekinumab, the patient presented with partial improvement of the skin lesions but had developed a large, alopecic, erythematous plaque with thick yellowish scales on the scalp (Figure 1). She also had a positive hair pull test. The presumptive initial diagnosis of the alopecic scalp lesion was tinea capitis, for which multiple potassium hydroxide preparations of scales were performed, all yielding negative results. In addition, histopathologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed (Figures 2A and 2B). Sterile tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli were obtained and showed no growth. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal structures.

A second biopsy showed a psoriasiform pattern, parakeratosis, and hypogranulosis, highly suggestive of psoriasis (Figure 2C and 2D). Based on those findings, a diagnosis of psoriatic alopecia was made. The mometasone was switched to clobetasol lotion 0.05%. The patient continued treatment with ustekinumab. At 6-month follow-up, her CD was well controlled and she showed hair regrowth in previously alopecic areas (Figure 3).

Comment

Psoriatic alopecia induced by a TNF-α inhibitor was first reported in 2007 in a 30-year-old woman with ankylosing spondylitis who was being treated with adalimumab.8 She had erythematous, scaly, alopecic plaques on the scalp and palmoplantar pustulosis. Findings on skin biopsy were compatible with psoriasis. The patient’s severe scalp psoriasis failed to respond to topical steroid treatment and adalimumab cessation. The extensive hair loss responded to cyclosporine 3 mg/kg daily.8

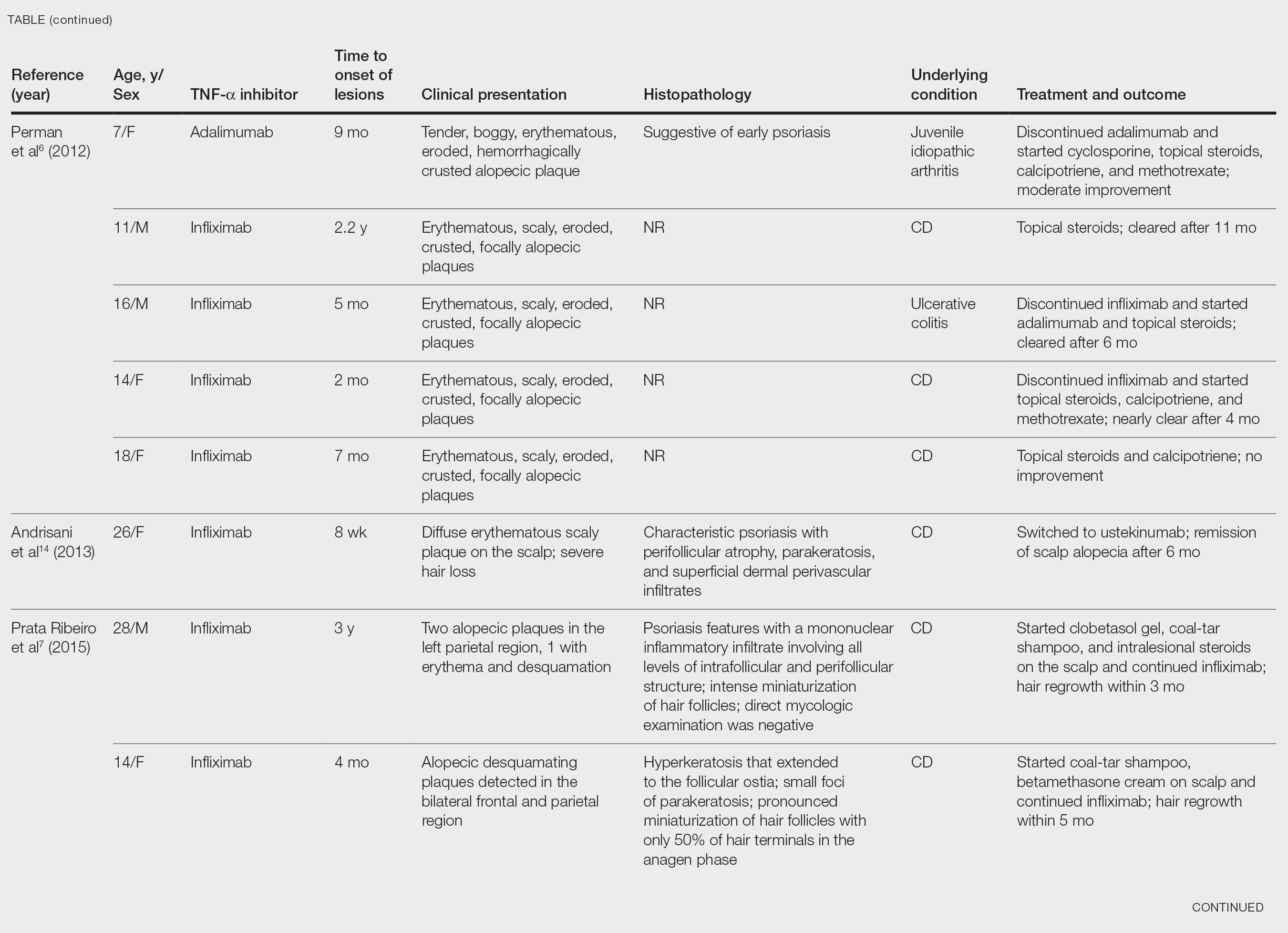

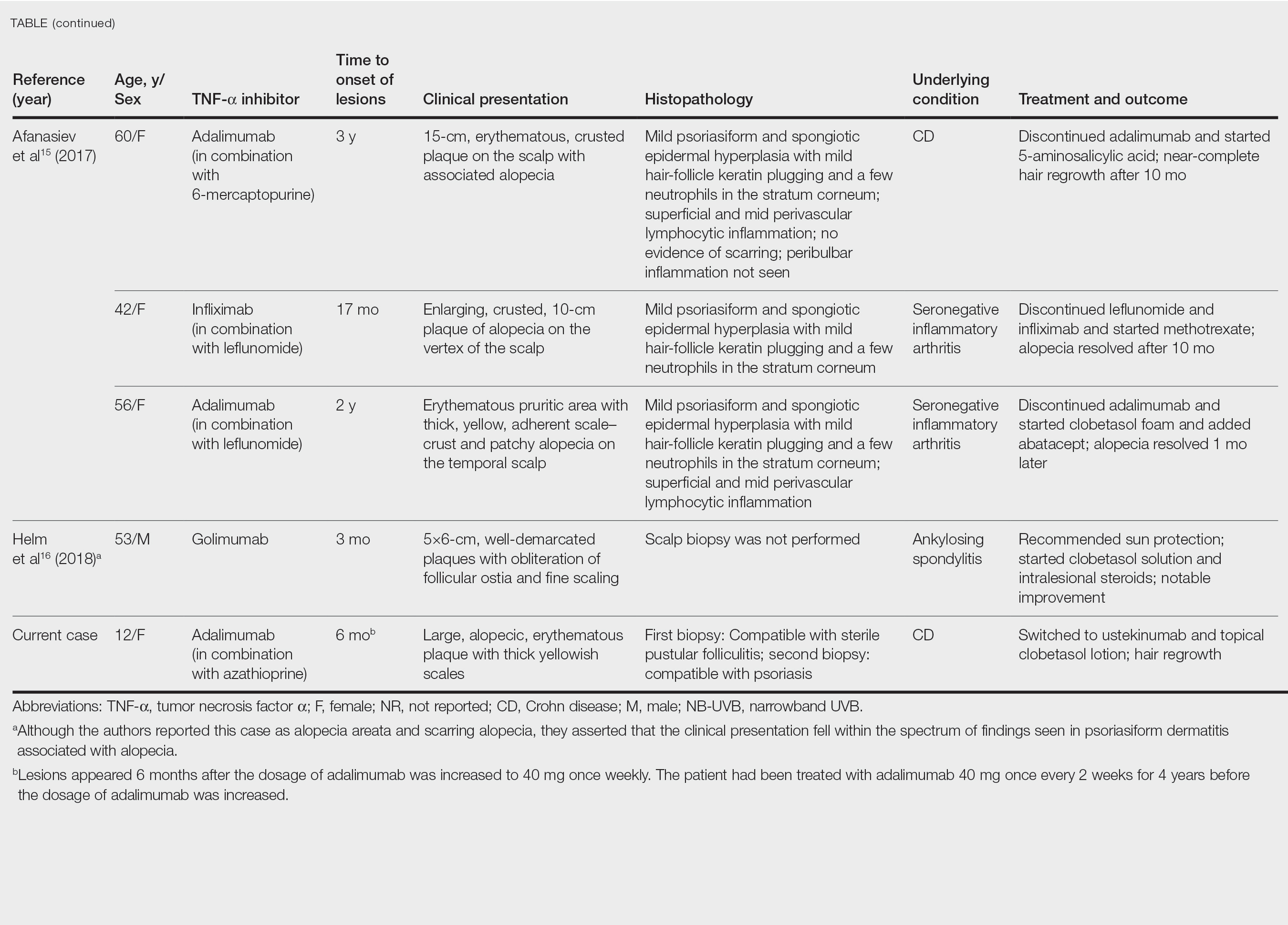

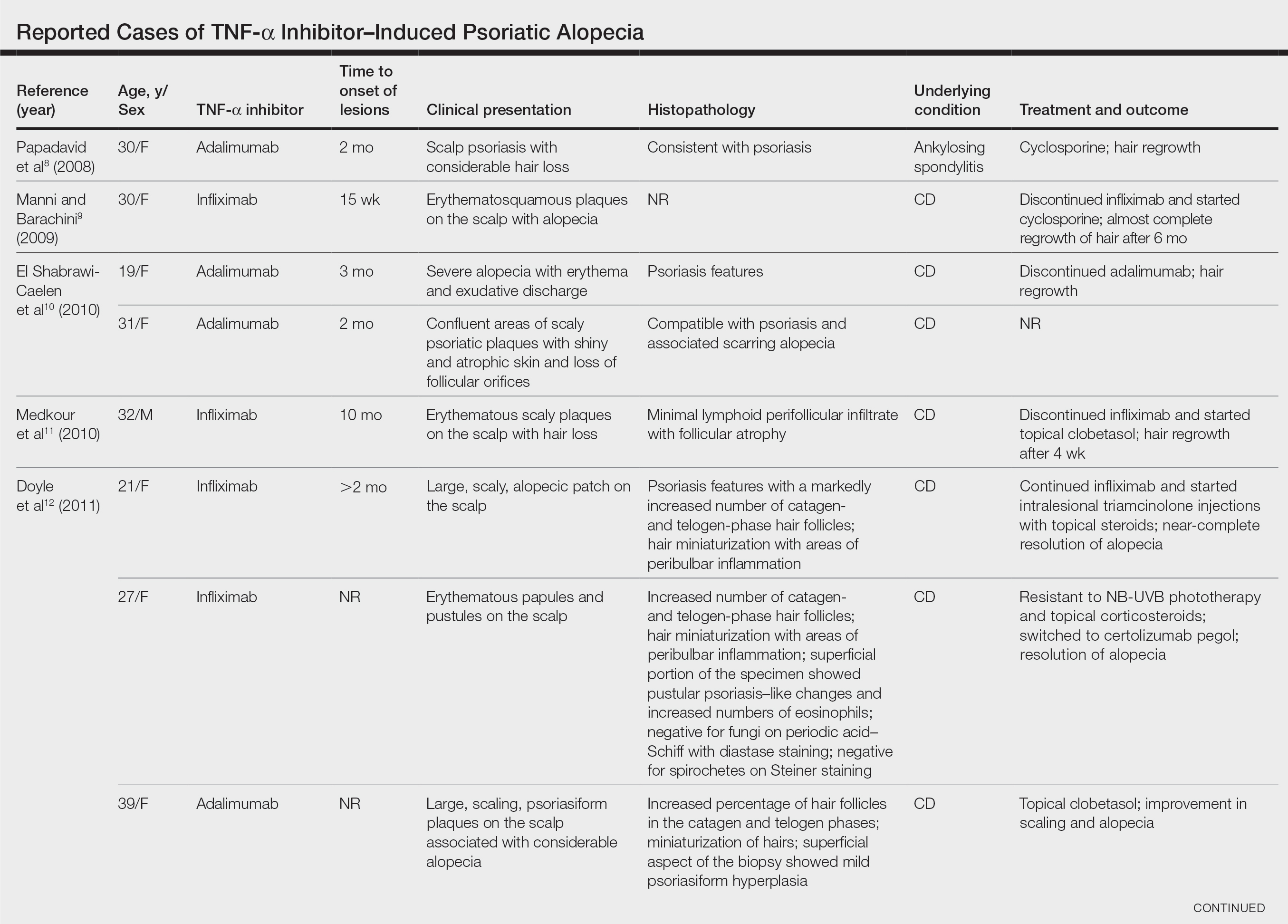

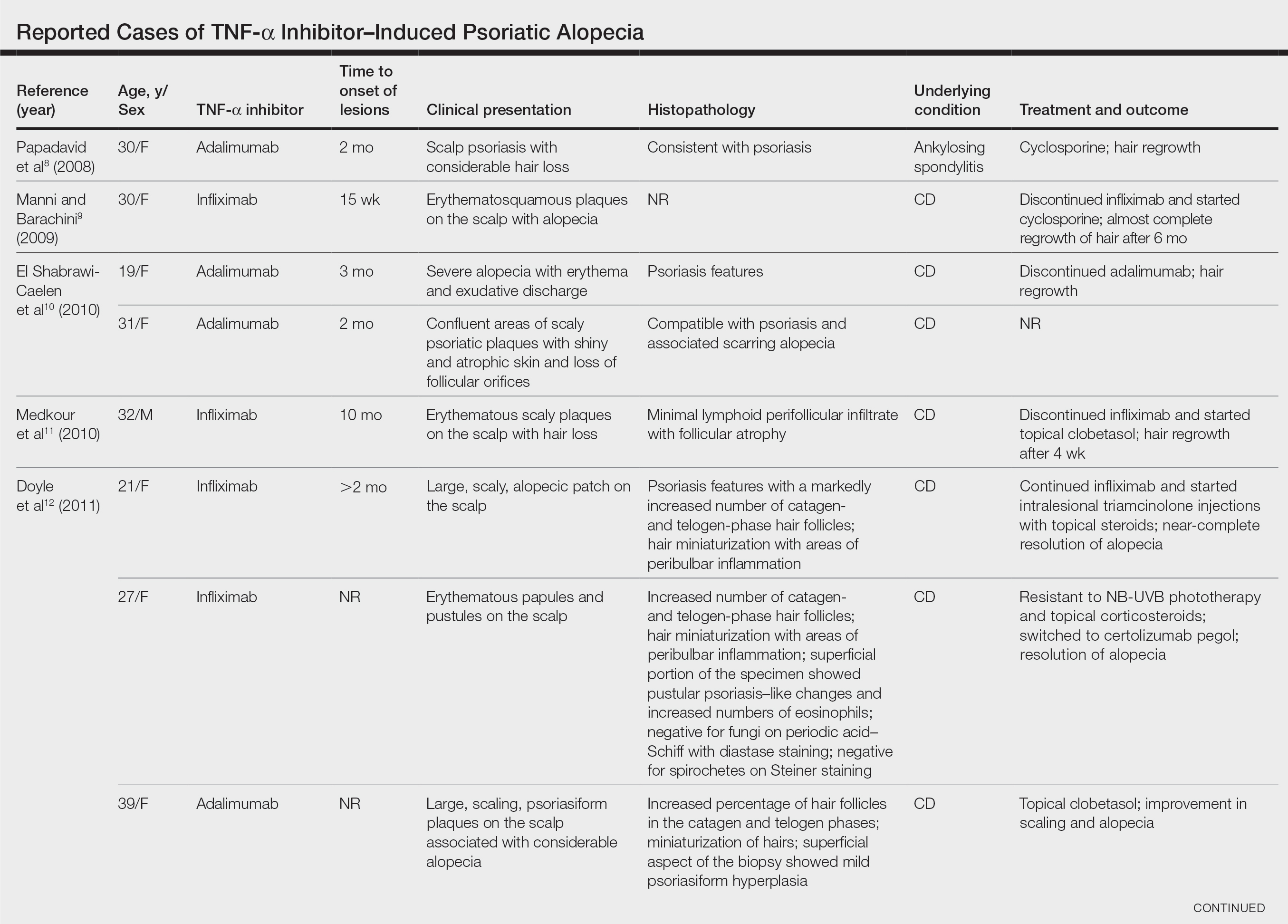

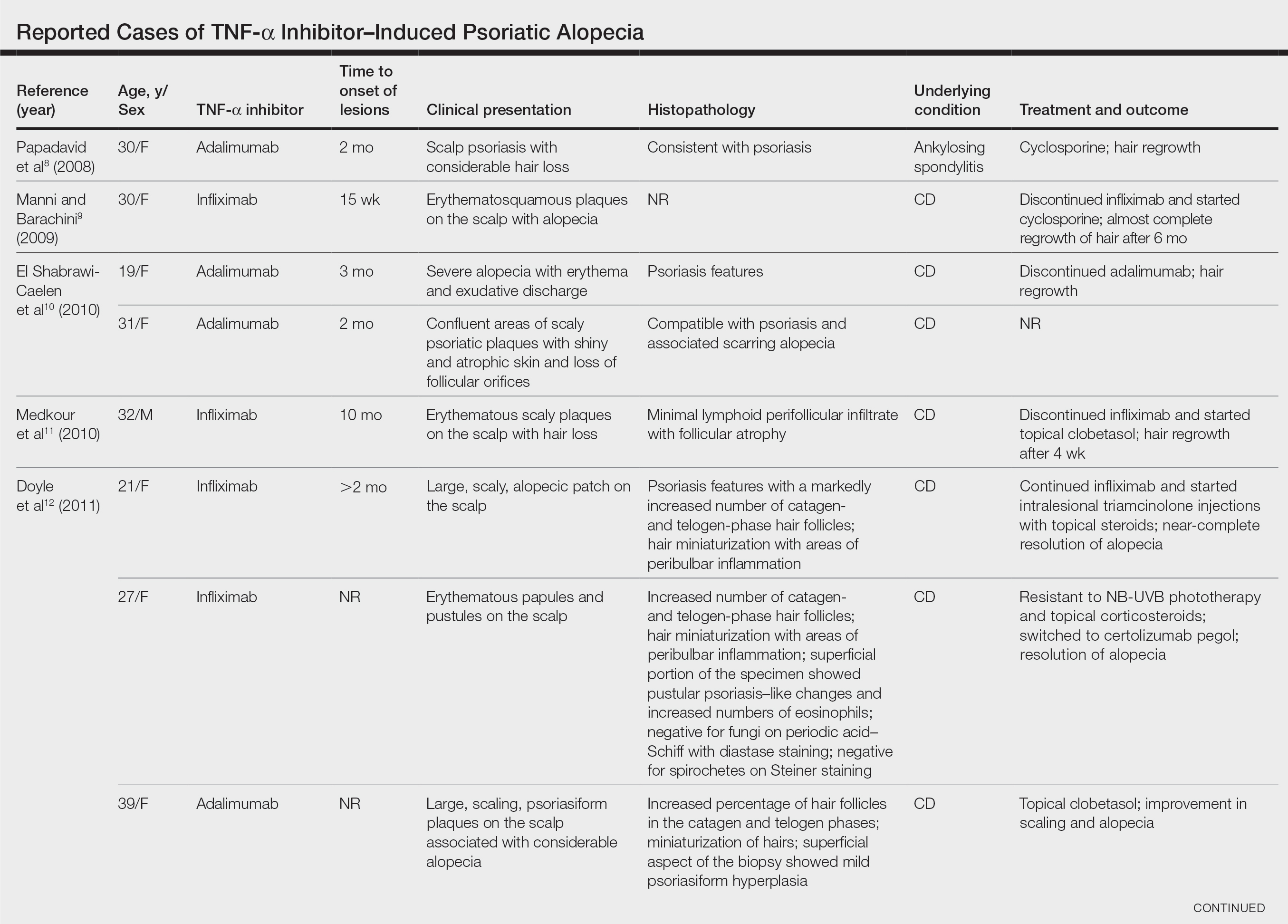

After conducting an extensive literature review, we found 26 cases of TNF-α–induced psoriatic alopecia, including the current case (Table).6-16 The mean age at diagnosis was 27.8 years (SD, 13.6 years; range, 7–60 years). The female-to-male ratio was 3.3:1. The most common underlying condition for which TNF-α inhibitors were prescribed was CD (77% [20/26]). Psoriatic alopecia most commonly was reported secondary to treatment with infliximab (54% [14/26]), followed by adalimumab (42% [11/26]). Golimumab was the causative drug in 1 (4%) case. We did not find reports of etanercept or certolizumab having induced this manifestation. The onset of the scalp lesions occurred 2 to 46 months after starting treatment with the causative medication.

Laga et al17 reported that TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis can have a variety of histopathologic findings, including typical findings of various stages of psoriasis, a lichenoid pattern mimicking remnants of lichen planus, and sterile pustular folliculitis. Our patient’s 2 scalp biopsies demonstrated results consistent with findings reported by Laga et al.17 In the first biopsy, findings were consistent with a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with negative sterile cultures and negative periodic acid–Schiff stain (sterile folliculitis), with crust and areas of parakeratosis. The second biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and an absent granular layer, all typical features of psoriasis (Figure 2).

Including the current case, our review of the literature yielded 7 pediatric (ie, 0–18 years of age) cases of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. Of the 6 previously reported pediatric cases, 5 occurred after administration of infliximab.6,7

Similar to our case, TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia was reported in a 7-year-old girl who was treated with adalimumab for juvenile idiopathic arthritis.6 Nine months after starting treatment, that patient presented with a tender, erythematous, eroded, and crusted alopecic plaque along with scaly plaques on the scalp. Adalimumab was discontinued, and cyclosporine and topical steroids were started. Cyclosporine was then discontinued due to partial resolution of the psoriasis; the patient was started on abatacept, with persistence of the psoriasis and alopecia. The patient was then started on oral methotrexate 12.5 mg once weekly with moderate improvement and mild to moderate exacerbations.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis may occur as a result of a cytokine imbalance. A TNF-α blockade leads to upregulation of interferon α (IFN-α) and TNF-α production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), usually in genetically susceptible people.6,7,9-15 The IFN-α induces maturation of myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) responsible for increasing proinflammatory cytokines that contribute to psoriasis.11 Generation of TNF-α by pDCs leads to mature or activated dendritic cells derived from pDCs through autocrine TNF-α production and paracrine IFN-α production from immature mDCs.9 Once pDCs mature, they are incapable of producing IFN-α; TNF-α then inhibits IFN-α production by inducing pDC maturation.11 Overproduction of IFN-α during TNF-α inhibition induces expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 on T cells, which recruits T cells to the dermis. The T cells then produce TNF-α, causing psoriatic skin lesions.10,11,13,14

Although TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia is uncommon, the condition should be considered in female patients with underlying proinflammatory disease—CD in particular. Perman et al6 reported 5 cases of psoriatic alopecia in which 3 patients initially were treated with griseofulvin because of suspected tinea capitis.

Conditions with similar clinical findings should be ruled out before making a diagnosis of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. Although clinicopathologic correlation is essential for making the diagnosis, it is possible that the histologic findings will not be specific for psoriasis.17 It is important to be aware of this condition in patients being treated with a TNF-α inhibitor as early as 2 months to 4 years or longer after starting treatment.

Previously reported cases have demonstrated various treatment options that yielded improvement or resolution of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. These include either continuation or discontinuation of the TNF-α inhibitor combined with topical or intralesional steroids, methotrexate, or cyclosporine. Another option is to switch the TNF-α inhibitor to another biologic. Outcomes vary from patient to patient, making the physician’s clinical judgment crucial in deciding which treatment route to take. Our patient showed notable improvement when she was switched from adalimumab to ustekinumab as well as the combination of ustekinumab and clobetasol lotion 0.05%.

Conclusion

We recommend an individualized approach that provides patients with the safest and least invasive treatment option for TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. In most reported cases, the problem resolved with treatment, thereby classifying this form of alopecia as noncicatricial alopecia.

- Horneff G, Seyger MMB, Arikan D, et al. Safety of adalimumab in pediatric patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr. 2018;201:166-175.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.042

- Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

- George SMC, Taylor MR, Farrant PBJ. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721. doi:10.1111/ced.12715

- Shuster S. Psoriatic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:73-77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb05103.x

- Silva CY, Brown KL, Kurban AK, et al. Psoriatic alopecia—fact or fiction? a clinicohistopathologic reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:611-619. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.100574

- Perman MJ, Lovell DJ, Denson LA, et al. Five cases of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced psoriasis presenting with severe scalp involvement in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:454-459. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01521.x

- Prata Ribeiro LB, Gonçalves Rego JC, Duque Estrada B, et al. Alopecia secondary to anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:232–235. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153084

- Papadavid E, Gazi S, Dalamaga M, et al. Palmoplantar and scalp psoriasis occurring during anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy: a case series of four patients and guidelines for management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:380-382. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02335.x

- Manni E, Barachini P. Psoriasis induced by infliximab in a patient suffering from Crohn’s disease. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22:841-844. doi:10.1177/039463200902200331

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, La Placa M, Vincenzi C, et al. Adalimumab-induced psoriasis of the scalp with diffuse alopecia: a severe potentially irreversible cutaneous side effect of TNF-alpha blockers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:182-183. doi:10.1002/ibd.20954

- Medkour F, Babai S, Chanteloup E, et al. Development of diffuse psoriasis with alopecia during treatment of Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:140-141. doi:10.1016/j.gcb.2009.10.021

- Doyle LA, Sperling LC, Baksh S, et al. Psoriatic alopecia/alopecia areata-like reactions secondary to anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy: a novel cause of noncicatricial alopecia. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:161-166. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181ef7403

- Osório F, Magro F, Lisboa C, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha induced psoriasiform eruptions with severe scalp involvement and alopecia: report of five cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:163-167. doi:10.1159/000342503

- Andrisani G, Marzo M, Celleno L, et al. Development of psoriasis scalp with alopecia during treatment of Crohn’s disease with infliximab and rapid response to both diseases to ustekinumab. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2831-2836.

- Afanasiev OK, Zhang CZ, Ruhoy SM. TNF-inhibitor associated psoriatic alopecia: diagnostic utility of sebaceous lobule atrophy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:563-569. doi:10.1111/cup.12932

- Helm MM, Haddad S. Alopecia areata and scarring alopecia presenting during golimumab therapy for ankylosing spondylitis. N Am J Med Sci. 2018;11:22-24. doi:10.7156/najms.2018.110122

- Laga AC, Vleugels RA, Qureshi AA, et al. Histopathologic spectrum of psoriasiform skin reactions associated with tumor necrosis factor-a inhibitor therapy. a study of 16 biopsies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:568-573. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3ff7

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced psoriasis is a known paradoxical adverse effect of this family of medications, which includes infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and certolizumab. In the pediatric population, these therapies recently gained approval for nondermatologic conditions—meaning that this phenomenon is encountered more frequently.1 In a systematic review of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis, severe scalp involvement was associated with alopecia in 7.5% of cases.2 Onset of scalp psoriasis with alopecia in patients being treated with a TNF-α inhibitor should lead to consideration of this condition.

Psoriatic alopecia is an uncommon presentation of psoriasis. Although well described, alopecia as a clinical manifestation of scalp psoriasis is not a well-known concept among clinicians and has never been widely accepted. Adding to the diagnostic challenge is that psoriatic alopecia secondary to TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis rarely has been reported in adults or children.3-5 Including our case, our review of the literature yielded 7 pediatric cases (≤18 years) of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia.6,7 A primary literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms psoriatic alopecia, psoriasiform alopecia, TNF-α inhibitors, infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and certolizumab.

We present the case of a pediatric patient with psoriatic alopecia secondary to treatment with adalimumab for Crohn disease (CD). We also provide a review of reported cases of psoriatic alopecia induced by a TNF-α inhibitor in the literature.

Case Report

A 12-year-old girl presented to our dermatology clinic with erythematous scaly plaques on the trunk, scalp, arms, and legs of 2 months’ duration. The lesions involved approximately 15% of the body surface area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for CD diagnosed 4 years prior to presentation of the skin lesions. She had been treated for the past 2 years with adalimumab 40 mg once every 2 weeks and azathioprine 100 mg once daily. Because her CD was poorly controlled, the dosage of adalimumab was increased to 40 mg once weekly 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Our diagnosis was TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis secondary to treatment with adalimumab.

The patient was treated with mometasone lotion 0.1% for the scalp lesions and triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body lesions. Because of the extent of the psoriasis, we recommended changing adalimumab to ustekinumab, which is approved for CD in adults but is off label in children.

At 1-month follow-up, after receiving the induction dose of ustekinumab, the patient presented with partial improvement of the skin lesions but had developed a large, alopecic, erythematous plaque with thick yellowish scales on the scalp (Figure 1). She also had a positive hair pull test. The presumptive initial diagnosis of the alopecic scalp lesion was tinea capitis, for which multiple potassium hydroxide preparations of scales were performed, all yielding negative results. In addition, histopathologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed (Figures 2A and 2B). Sterile tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli were obtained and showed no growth. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal structures.

A second biopsy showed a psoriasiform pattern, parakeratosis, and hypogranulosis, highly suggestive of psoriasis (Figure 2C and 2D). Based on those findings, a diagnosis of psoriatic alopecia was made. The mometasone was switched to clobetasol lotion 0.05%. The patient continued treatment with ustekinumab. At 6-month follow-up, her CD was well controlled and she showed hair regrowth in previously alopecic areas (Figure 3).

Comment

Psoriatic alopecia induced by a TNF-α inhibitor was first reported in 2007 in a 30-year-old woman with ankylosing spondylitis who was being treated with adalimumab.8 She had erythematous, scaly, alopecic plaques on the scalp and palmoplantar pustulosis. Findings on skin biopsy were compatible with psoriasis. The patient’s severe scalp psoriasis failed to respond to topical steroid treatment and adalimumab cessation. The extensive hair loss responded to cyclosporine 3 mg/kg daily.8

After conducting an extensive literature review, we found 26 cases of TNF-α–induced psoriatic alopecia, including the current case (Table).6-16 The mean age at diagnosis was 27.8 years (SD, 13.6 years; range, 7–60 years). The female-to-male ratio was 3.3:1. The most common underlying condition for which TNF-α inhibitors were prescribed was CD (77% [20/26]). Psoriatic alopecia most commonly was reported secondary to treatment with infliximab (54% [14/26]), followed by adalimumab (42% [11/26]). Golimumab was the causative drug in 1 (4%) case. We did not find reports of etanercept or certolizumab having induced this manifestation. The onset of the scalp lesions occurred 2 to 46 months after starting treatment with the causative medication.

Laga et al17 reported that TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis can have a variety of histopathologic findings, including typical findings of various stages of psoriasis, a lichenoid pattern mimicking remnants of lichen planus, and sterile pustular folliculitis. Our patient’s 2 scalp biopsies demonstrated results consistent with findings reported by Laga et al.17 In the first biopsy, findings were consistent with a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with negative sterile cultures and negative periodic acid–Schiff stain (sterile folliculitis), with crust and areas of parakeratosis. The second biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and an absent granular layer, all typical features of psoriasis (Figure 2).

Including the current case, our review of the literature yielded 7 pediatric (ie, 0–18 years of age) cases of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. Of the 6 previously reported pediatric cases, 5 occurred after administration of infliximab.6,7

Similar to our case, TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia was reported in a 7-year-old girl who was treated with adalimumab for juvenile idiopathic arthritis.6 Nine months after starting treatment, that patient presented with a tender, erythematous, eroded, and crusted alopecic plaque along with scaly plaques on the scalp. Adalimumab was discontinued, and cyclosporine and topical steroids were started. Cyclosporine was then discontinued due to partial resolution of the psoriasis; the patient was started on abatacept, with persistence of the psoriasis and alopecia. The patient was then started on oral methotrexate 12.5 mg once weekly with moderate improvement and mild to moderate exacerbations.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis may occur as a result of a cytokine imbalance. A TNF-α blockade leads to upregulation of interferon α (IFN-α) and TNF-α production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), usually in genetically susceptible people.6,7,9-15 The IFN-α induces maturation of myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) responsible for increasing proinflammatory cytokines that contribute to psoriasis.11 Generation of TNF-α by pDCs leads to mature or activated dendritic cells derived from pDCs through autocrine TNF-α production and paracrine IFN-α production from immature mDCs.9 Once pDCs mature, they are incapable of producing IFN-α; TNF-α then inhibits IFN-α production by inducing pDC maturation.11 Overproduction of IFN-α during TNF-α inhibition induces expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 on T cells, which recruits T cells to the dermis. The T cells then produce TNF-α, causing psoriatic skin lesions.10,11,13,14

Although TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia is uncommon, the condition should be considered in female patients with underlying proinflammatory disease—CD in particular. Perman et al6 reported 5 cases of psoriatic alopecia in which 3 patients initially were treated with griseofulvin because of suspected tinea capitis.

Conditions with similar clinical findings should be ruled out before making a diagnosis of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. Although clinicopathologic correlation is essential for making the diagnosis, it is possible that the histologic findings will not be specific for psoriasis.17 It is important to be aware of this condition in patients being treated with a TNF-α inhibitor as early as 2 months to 4 years or longer after starting treatment.

Previously reported cases have demonstrated various treatment options that yielded improvement or resolution of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. These include either continuation or discontinuation of the TNF-α inhibitor combined with topical or intralesional steroids, methotrexate, or cyclosporine. Another option is to switch the TNF-α inhibitor to another biologic. Outcomes vary from patient to patient, making the physician’s clinical judgment crucial in deciding which treatment route to take. Our patient showed notable improvement when she was switched from adalimumab to ustekinumab as well as the combination of ustekinumab and clobetasol lotion 0.05%.

Conclusion

We recommend an individualized approach that provides patients with the safest and least invasive treatment option for TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. In most reported cases, the problem resolved with treatment, thereby classifying this form of alopecia as noncicatricial alopecia.

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced psoriasis is a known paradoxical adverse effect of this family of medications, which includes infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and certolizumab. In the pediatric population, these therapies recently gained approval for nondermatologic conditions—meaning that this phenomenon is encountered more frequently.1 In a systematic review of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis, severe scalp involvement was associated with alopecia in 7.5% of cases.2 Onset of scalp psoriasis with alopecia in patients being treated with a TNF-α inhibitor should lead to consideration of this condition.

Psoriatic alopecia is an uncommon presentation of psoriasis. Although well described, alopecia as a clinical manifestation of scalp psoriasis is not a well-known concept among clinicians and has never been widely accepted. Adding to the diagnostic challenge is that psoriatic alopecia secondary to TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis rarely has been reported in adults or children.3-5 Including our case, our review of the literature yielded 7 pediatric cases (≤18 years) of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia.6,7 A primary literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms psoriatic alopecia, psoriasiform alopecia, TNF-α inhibitors, infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and certolizumab.

We present the case of a pediatric patient with psoriatic alopecia secondary to treatment with adalimumab for Crohn disease (CD). We also provide a review of reported cases of psoriatic alopecia induced by a TNF-α inhibitor in the literature.

Case Report

A 12-year-old girl presented to our dermatology clinic with erythematous scaly plaques on the trunk, scalp, arms, and legs of 2 months’ duration. The lesions involved approximately 15% of the body surface area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for CD diagnosed 4 years prior to presentation of the skin lesions. She had been treated for the past 2 years with adalimumab 40 mg once every 2 weeks and azathioprine 100 mg once daily. Because her CD was poorly controlled, the dosage of adalimumab was increased to 40 mg once weekly 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Our diagnosis was TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis secondary to treatment with adalimumab.

The patient was treated with mometasone lotion 0.1% for the scalp lesions and triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body lesions. Because of the extent of the psoriasis, we recommended changing adalimumab to ustekinumab, which is approved for CD in adults but is off label in children.

At 1-month follow-up, after receiving the induction dose of ustekinumab, the patient presented with partial improvement of the skin lesions but had developed a large, alopecic, erythematous plaque with thick yellowish scales on the scalp (Figure 1). She also had a positive hair pull test. The presumptive initial diagnosis of the alopecic scalp lesion was tinea capitis, for which multiple potassium hydroxide preparations of scales were performed, all yielding negative results. In addition, histopathologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed (Figures 2A and 2B). Sterile tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli were obtained and showed no growth. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal structures.

A second biopsy showed a psoriasiform pattern, parakeratosis, and hypogranulosis, highly suggestive of psoriasis (Figure 2C and 2D). Based on those findings, a diagnosis of psoriatic alopecia was made. The mometasone was switched to clobetasol lotion 0.05%. The patient continued treatment with ustekinumab. At 6-month follow-up, her CD was well controlled and she showed hair regrowth in previously alopecic areas (Figure 3).

Comment

Psoriatic alopecia induced by a TNF-α inhibitor was first reported in 2007 in a 30-year-old woman with ankylosing spondylitis who was being treated with adalimumab.8 She had erythematous, scaly, alopecic plaques on the scalp and palmoplantar pustulosis. Findings on skin biopsy were compatible with psoriasis. The patient’s severe scalp psoriasis failed to respond to topical steroid treatment and adalimumab cessation. The extensive hair loss responded to cyclosporine 3 mg/kg daily.8

After conducting an extensive literature review, we found 26 cases of TNF-α–induced psoriatic alopecia, including the current case (Table).6-16 The mean age at diagnosis was 27.8 years (SD, 13.6 years; range, 7–60 years). The female-to-male ratio was 3.3:1. The most common underlying condition for which TNF-α inhibitors were prescribed was CD (77% [20/26]). Psoriatic alopecia most commonly was reported secondary to treatment with infliximab (54% [14/26]), followed by adalimumab (42% [11/26]). Golimumab was the causative drug in 1 (4%) case. We did not find reports of etanercept or certolizumab having induced this manifestation. The onset of the scalp lesions occurred 2 to 46 months after starting treatment with the causative medication.

Laga et al17 reported that TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis can have a variety of histopathologic findings, including typical findings of various stages of psoriasis, a lichenoid pattern mimicking remnants of lichen planus, and sterile pustular folliculitis. Our patient’s 2 scalp biopsies demonstrated results consistent with findings reported by Laga et al.17 In the first biopsy, findings were consistent with a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with negative sterile cultures and negative periodic acid–Schiff stain (sterile folliculitis), with crust and areas of parakeratosis. The second biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and an absent granular layer, all typical features of psoriasis (Figure 2).

Including the current case, our review of the literature yielded 7 pediatric (ie, 0–18 years of age) cases of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. Of the 6 previously reported pediatric cases, 5 occurred after administration of infliximab.6,7

Similar to our case, TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia was reported in a 7-year-old girl who was treated with adalimumab for juvenile idiopathic arthritis.6 Nine months after starting treatment, that patient presented with a tender, erythematous, eroded, and crusted alopecic plaque along with scaly plaques on the scalp. Adalimumab was discontinued, and cyclosporine and topical steroids were started. Cyclosporine was then discontinued due to partial resolution of the psoriasis; the patient was started on abatacept, with persistence of the psoriasis and alopecia. The patient was then started on oral methotrexate 12.5 mg once weekly with moderate improvement and mild to moderate exacerbations.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis may occur as a result of a cytokine imbalance. A TNF-α blockade leads to upregulation of interferon α (IFN-α) and TNF-α production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), usually in genetically susceptible people.6,7,9-15 The IFN-α induces maturation of myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) responsible for increasing proinflammatory cytokines that contribute to psoriasis.11 Generation of TNF-α by pDCs leads to mature or activated dendritic cells derived from pDCs through autocrine TNF-α production and paracrine IFN-α production from immature mDCs.9 Once pDCs mature, they are incapable of producing IFN-α; TNF-α then inhibits IFN-α production by inducing pDC maturation.11 Overproduction of IFN-α during TNF-α inhibition induces expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 on T cells, which recruits T cells to the dermis. The T cells then produce TNF-α, causing psoriatic skin lesions.10,11,13,14

Although TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia is uncommon, the condition should be considered in female patients with underlying proinflammatory disease—CD in particular. Perman et al6 reported 5 cases of psoriatic alopecia in which 3 patients initially were treated with griseofulvin because of suspected tinea capitis.

Conditions with similar clinical findings should be ruled out before making a diagnosis of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. Although clinicopathologic correlation is essential for making the diagnosis, it is possible that the histologic findings will not be specific for psoriasis.17 It is important to be aware of this condition in patients being treated with a TNF-α inhibitor as early as 2 months to 4 years or longer after starting treatment.

Previously reported cases have demonstrated various treatment options that yielded improvement or resolution of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. These include either continuation or discontinuation of the TNF-α inhibitor combined with topical or intralesional steroids, methotrexate, or cyclosporine. Another option is to switch the TNF-α inhibitor to another biologic. Outcomes vary from patient to patient, making the physician’s clinical judgment crucial in deciding which treatment route to take. Our patient showed notable improvement when she was switched from adalimumab to ustekinumab as well as the combination of ustekinumab and clobetasol lotion 0.05%.

Conclusion

We recommend an individualized approach that provides patients with the safest and least invasive treatment option for TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. In most reported cases, the problem resolved with treatment, thereby classifying this form of alopecia as noncicatricial alopecia.

- Horneff G, Seyger MMB, Arikan D, et al. Safety of adalimumab in pediatric patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr. 2018;201:166-175.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.042

- Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

- George SMC, Taylor MR, Farrant PBJ. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721. doi:10.1111/ced.12715

- Shuster S. Psoriatic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:73-77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb05103.x

- Silva CY, Brown KL, Kurban AK, et al. Psoriatic alopecia—fact or fiction? a clinicohistopathologic reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:611-619. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.100574

- Perman MJ, Lovell DJ, Denson LA, et al. Five cases of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced psoriasis presenting with severe scalp involvement in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:454-459. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01521.x

- Prata Ribeiro LB, Gonçalves Rego JC, Duque Estrada B, et al. Alopecia secondary to anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:232–235. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153084

- Papadavid E, Gazi S, Dalamaga M, et al. Palmoplantar and scalp psoriasis occurring during anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy: a case series of four patients and guidelines for management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:380-382. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02335.x

- Manni E, Barachini P. Psoriasis induced by infliximab in a patient suffering from Crohn’s disease. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22:841-844. doi:10.1177/039463200902200331

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, La Placa M, Vincenzi C, et al. Adalimumab-induced psoriasis of the scalp with diffuse alopecia: a severe potentially irreversible cutaneous side effect of TNF-alpha blockers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:182-183. doi:10.1002/ibd.20954

- Medkour F, Babai S, Chanteloup E, et al. Development of diffuse psoriasis with alopecia during treatment of Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:140-141. doi:10.1016/j.gcb.2009.10.021

- Doyle LA, Sperling LC, Baksh S, et al. Psoriatic alopecia/alopecia areata-like reactions secondary to anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy: a novel cause of noncicatricial alopecia. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:161-166. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181ef7403

- Osório F, Magro F, Lisboa C, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha induced psoriasiform eruptions with severe scalp involvement and alopecia: report of five cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:163-167. doi:10.1159/000342503

- Andrisani G, Marzo M, Celleno L, et al. Development of psoriasis scalp with alopecia during treatment of Crohn’s disease with infliximab and rapid response to both diseases to ustekinumab. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2831-2836.

- Afanasiev OK, Zhang CZ, Ruhoy SM. TNF-inhibitor associated psoriatic alopecia: diagnostic utility of sebaceous lobule atrophy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:563-569. doi:10.1111/cup.12932

- Helm MM, Haddad S. Alopecia areata and scarring alopecia presenting during golimumab therapy for ankylosing spondylitis. N Am J Med Sci. 2018;11:22-24. doi:10.7156/najms.2018.110122

- Laga AC, Vleugels RA, Qureshi AA, et al. Histopathologic spectrum of psoriasiform skin reactions associated with tumor necrosis factor-a inhibitor therapy. a study of 16 biopsies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:568-573. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3ff7

- Horneff G, Seyger MMB, Arikan D, et al. Safety of adalimumab in pediatric patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr. 2018;201:166-175.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.042

- Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

- George SMC, Taylor MR, Farrant PBJ. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721. doi:10.1111/ced.12715

- Shuster S. Psoriatic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:73-77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb05103.x

- Silva CY, Brown KL, Kurban AK, et al. Psoriatic alopecia—fact or fiction? a clinicohistopathologic reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:611-619. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.100574

- Perman MJ, Lovell DJ, Denson LA, et al. Five cases of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced psoriasis presenting with severe scalp involvement in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:454-459. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01521.x

- Prata Ribeiro LB, Gonçalves Rego JC, Duque Estrada B, et al. Alopecia secondary to anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:232–235. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153084

- Papadavid E, Gazi S, Dalamaga M, et al. Palmoplantar and scalp psoriasis occurring during anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy: a case series of four patients and guidelines for management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:380-382. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02335.x

- Manni E, Barachini P. Psoriasis induced by infliximab in a patient suffering from Crohn’s disease. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22:841-844. doi:10.1177/039463200902200331

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, La Placa M, Vincenzi C, et al. Adalimumab-induced psoriasis of the scalp with diffuse alopecia: a severe potentially irreversible cutaneous side effect of TNF-alpha blockers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:182-183. doi:10.1002/ibd.20954

- Medkour F, Babai S, Chanteloup E, et al. Development of diffuse psoriasis with alopecia during treatment of Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:140-141. doi:10.1016/j.gcb.2009.10.021

- Doyle LA, Sperling LC, Baksh S, et al. Psoriatic alopecia/alopecia areata-like reactions secondary to anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy: a novel cause of noncicatricial alopecia. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:161-166. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181ef7403

- Osório F, Magro F, Lisboa C, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha induced psoriasiform eruptions with severe scalp involvement and alopecia: report of five cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:163-167. doi:10.1159/000342503

- Andrisani G, Marzo M, Celleno L, et al. Development of psoriasis scalp with alopecia during treatment of Crohn’s disease with infliximab and rapid response to both diseases to ustekinumab. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2831-2836.

- Afanasiev OK, Zhang CZ, Ruhoy SM. TNF-inhibitor associated psoriatic alopecia: diagnostic utility of sebaceous lobule atrophy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:563-569. doi:10.1111/cup.12932

- Helm MM, Haddad S. Alopecia areata and scarring alopecia presenting during golimumab therapy for ankylosing spondylitis. N Am J Med Sci. 2018;11:22-24. doi:10.7156/najms.2018.110122

- Laga AC, Vleugels RA, Qureshi AA, et al. Histopathologic spectrum of psoriasiform skin reactions associated with tumor necrosis factor-a inhibitor therapy. a study of 16 biopsies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:568-573. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3ff7

Practice Points

- Psoriatic alopecia is a rare nonscarring alopecia that can present as a complication of treatment with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.

- This finding commonly is seen in females undergoing treatment with infliximab or adalimumab, usually for Crohn disease.

- Histopathologic findings can show a psoriasiform-pattern, neutrophil-rich, inflammatory infiltrate involving hair follicles or a lichenoid pattern.

Among asymptomatic, 2% may harbor 90% of community’s viral load: Study

About 2% of asymptomatic college students carried 90% of COVID-19 viral load levels on a Colorado campus last year, new research reveals. Furthermore, the viral loads in these students were as elevated as those seen in hospitalized patients.

“College campuses were one of the few places where people without any symptoms or suspicions of exposure were being screened for the virus. This allowed us to make some powerful comparisons between symptomatic vs healthy carriers of the virus,” senior study author Sara Sawyer, PhD, professor of virology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said in an interview.

“It turns out, walking around a college campus can be as dangerous as walking through a COVID ward in the hospital, in that you will experience these viral ‘super carriers’ equally in both settings,” she said.

“This is an important study in advancing our understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 is distributed in the population,” Thomas Giordano, MD, MPH, professor and section chief of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

The study “adds to the evidence that viral load is not too tightly correlated with symptoms.” In fact, Dr. Giordano added, “this study suggests viral load is not at all correlated with symptoms.”

Viral load may not be correlated with transmissibility either, said Raphael Viscidi, MD, when asked to comment. “This is not a transmissibility study. They did not show that viral load is the factor related to transmission.”

“It’s true that 2% of the population they studied carried 90% of the virus, but it does not establish any biological importance to that 2%,” added Dr. Viscidi, professor of pediatrics and oncology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore,.

The 2% could just be the upper tail end of a normal bell-shaped distribution curve, Dr. Viscidi said, or there could be something biologically unique about that group. But the study does not make that distinction, he said.

The study was published online May 10, 2021, in PNAS, the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

A similar picture in hospitalized patients

Out of more than 72,500 saliva samples taken during COVID-19 screening at the University of Colorado Boulder between Aug. 27 and Dec. 11, 2020, 1,405 were positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The investigators also compared viral loads from students with those of hospitalized patients based on published data. They found the distribution of viral loads between these groups “indistinguishable.”

“Strikingly, these datasets demonstrate dramatic differences in viral levels between individuals, with a very small minority of the infected individuals harboring the vast majority of the infectious virions,” the researchers wrote. The comparison “really represents two extremes: One group is mostly hospitalized, while the other group represents a mostly young and healthy (but infected) college population.”

“It would be interesting to adjust public health recommendations based on a person’s viral load,” Dr. Giordano said. “One could speculate that a person with a very high viral load could be isolated longer or more thoroughly, while someone with a very low viral load could be minimally isolated.

“This is speculation, and more data are needed to test this concept,” he added. Also, quantitative viral load testing would need to be standardized before it could be used to guide such decision-making

Preceding the COVID-19 vaccine era

It should be noted that the research was conducted in fall 2020, before access to COVID-19 immunization.

“The study was performed prior to vaccine availability in a cohort of young people. It adds further data to support prior observations that the majority of infections are spread by a much smaller group of individuals,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview.

“Now that vaccines are available, I think it is very likely that a repeat study of this type would show diminished transmission from vaccinated people who were infected yet asymptomatic,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not affiliated with the research.

Mechanism still a mystery

“This finding has been in the literature in piecemeal fashion since the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Sawyer said. “I just think we were the first to realize the bigger implications of these plots of viral load that we have all been seeing over and over again.”

How a minority of people walk around asymptomatic with a majority of virus remains unanswered. Are there special people who can harbor these extremely high viral loads? Or do many infected individuals experience a short period of time when they carry such elevated levels?

The highest observed viral load in the current study was more than 6 trillion virions per mL. “It is remarkable to consider that this individual was on campus and reported no symptoms at our testing site,” the researchers wrote.

In contrast, the lowest viral load detected was 8 virions per mL.

Although more research is needed, the investigators noted that “a strong implication is that these individuals who are viral ‘super carriers’ may also be ‘superspreaders.’ ”

Some of the study authors have financial ties to companies that offer commercial SARS-CoV-2 testing, including Darwin Biosciences, TUMI Genomics, Faze Medicines, and Arpeggio Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 2% of asymptomatic college students carried 90% of COVID-19 viral load levels on a Colorado campus last year, new research reveals. Furthermore, the viral loads in these students were as elevated as those seen in hospitalized patients.

“College campuses were one of the few places where people without any symptoms or suspicions of exposure were being screened for the virus. This allowed us to make some powerful comparisons between symptomatic vs healthy carriers of the virus,” senior study author Sara Sawyer, PhD, professor of virology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said in an interview.

“It turns out, walking around a college campus can be as dangerous as walking through a COVID ward in the hospital, in that you will experience these viral ‘super carriers’ equally in both settings,” she said.

“This is an important study in advancing our understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 is distributed in the population,” Thomas Giordano, MD, MPH, professor and section chief of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

The study “adds to the evidence that viral load is not too tightly correlated with symptoms.” In fact, Dr. Giordano added, “this study suggests viral load is not at all correlated with symptoms.”

Viral load may not be correlated with transmissibility either, said Raphael Viscidi, MD, when asked to comment. “This is not a transmissibility study. They did not show that viral load is the factor related to transmission.”

“It’s true that 2% of the population they studied carried 90% of the virus, but it does not establish any biological importance to that 2%,” added Dr. Viscidi, professor of pediatrics and oncology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore,.

The 2% could just be the upper tail end of a normal bell-shaped distribution curve, Dr. Viscidi said, or there could be something biologically unique about that group. But the study does not make that distinction, he said.

The study was published online May 10, 2021, in PNAS, the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

A similar picture in hospitalized patients

Out of more than 72,500 saliva samples taken during COVID-19 screening at the University of Colorado Boulder between Aug. 27 and Dec. 11, 2020, 1,405 were positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The investigators also compared viral loads from students with those of hospitalized patients based on published data. They found the distribution of viral loads between these groups “indistinguishable.”

“Strikingly, these datasets demonstrate dramatic differences in viral levels between individuals, with a very small minority of the infected individuals harboring the vast majority of the infectious virions,” the researchers wrote. The comparison “really represents two extremes: One group is mostly hospitalized, while the other group represents a mostly young and healthy (but infected) college population.”

“It would be interesting to adjust public health recommendations based on a person’s viral load,” Dr. Giordano said. “One could speculate that a person with a very high viral load could be isolated longer or more thoroughly, while someone with a very low viral load could be minimally isolated.

“This is speculation, and more data are needed to test this concept,” he added. Also, quantitative viral load testing would need to be standardized before it could be used to guide such decision-making

Preceding the COVID-19 vaccine era

It should be noted that the research was conducted in fall 2020, before access to COVID-19 immunization.

“The study was performed prior to vaccine availability in a cohort of young people. It adds further data to support prior observations that the majority of infections are spread by a much smaller group of individuals,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview.

“Now that vaccines are available, I think it is very likely that a repeat study of this type would show diminished transmission from vaccinated people who were infected yet asymptomatic,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not affiliated with the research.

Mechanism still a mystery

“This finding has been in the literature in piecemeal fashion since the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Sawyer said. “I just think we were the first to realize the bigger implications of these plots of viral load that we have all been seeing over and over again.”

How a minority of people walk around asymptomatic with a majority of virus remains unanswered. Are there special people who can harbor these extremely high viral loads? Or do many infected individuals experience a short period of time when they carry such elevated levels?

The highest observed viral load in the current study was more than 6 trillion virions per mL. “It is remarkable to consider that this individual was on campus and reported no symptoms at our testing site,” the researchers wrote.

In contrast, the lowest viral load detected was 8 virions per mL.

Although more research is needed, the investigators noted that “a strong implication is that these individuals who are viral ‘super carriers’ may also be ‘superspreaders.’ ”

Some of the study authors have financial ties to companies that offer commercial SARS-CoV-2 testing, including Darwin Biosciences, TUMI Genomics, Faze Medicines, and Arpeggio Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 2% of asymptomatic college students carried 90% of COVID-19 viral load levels on a Colorado campus last year, new research reveals. Furthermore, the viral loads in these students were as elevated as those seen in hospitalized patients.

“College campuses were one of the few places where people without any symptoms or suspicions of exposure were being screened for the virus. This allowed us to make some powerful comparisons between symptomatic vs healthy carriers of the virus,” senior study author Sara Sawyer, PhD, professor of virology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said in an interview.

“It turns out, walking around a college campus can be as dangerous as walking through a COVID ward in the hospital, in that you will experience these viral ‘super carriers’ equally in both settings,” she said.

“This is an important study in advancing our understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 is distributed in the population,” Thomas Giordano, MD, MPH, professor and section chief of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

The study “adds to the evidence that viral load is not too tightly correlated with symptoms.” In fact, Dr. Giordano added, “this study suggests viral load is not at all correlated with symptoms.”

Viral load may not be correlated with transmissibility either, said Raphael Viscidi, MD, when asked to comment. “This is not a transmissibility study. They did not show that viral load is the factor related to transmission.”

“It’s true that 2% of the population they studied carried 90% of the virus, but it does not establish any biological importance to that 2%,” added Dr. Viscidi, professor of pediatrics and oncology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore,.

The 2% could just be the upper tail end of a normal bell-shaped distribution curve, Dr. Viscidi said, or there could be something biologically unique about that group. But the study does not make that distinction, he said.

The study was published online May 10, 2021, in PNAS, the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

A similar picture in hospitalized patients

Out of more than 72,500 saliva samples taken during COVID-19 screening at the University of Colorado Boulder between Aug. 27 and Dec. 11, 2020, 1,405 were positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The investigators also compared viral loads from students with those of hospitalized patients based on published data. They found the distribution of viral loads between these groups “indistinguishable.”

“Strikingly, these datasets demonstrate dramatic differences in viral levels between individuals, with a very small minority of the infected individuals harboring the vast majority of the infectious virions,” the researchers wrote. The comparison “really represents two extremes: One group is mostly hospitalized, while the other group represents a mostly young and healthy (but infected) college population.”

“It would be interesting to adjust public health recommendations based on a person’s viral load,” Dr. Giordano said. “One could speculate that a person with a very high viral load could be isolated longer or more thoroughly, while someone with a very low viral load could be minimally isolated.

“This is speculation, and more data are needed to test this concept,” he added. Also, quantitative viral load testing would need to be standardized before it could be used to guide such decision-making

Preceding the COVID-19 vaccine era

It should be noted that the research was conducted in fall 2020, before access to COVID-19 immunization.

“The study was performed prior to vaccine availability in a cohort of young people. It adds further data to support prior observations that the majority of infections are spread by a much smaller group of individuals,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview.

“Now that vaccines are available, I think it is very likely that a repeat study of this type would show diminished transmission from vaccinated people who were infected yet asymptomatic,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not affiliated with the research.

Mechanism still a mystery

“This finding has been in the literature in piecemeal fashion since the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Sawyer said. “I just think we were the first to realize the bigger implications of these plots of viral load that we have all been seeing over and over again.”

How a minority of people walk around asymptomatic with a majority of virus remains unanswered. Are there special people who can harbor these extremely high viral loads? Or do many infected individuals experience a short period of time when they carry such elevated levels?

The highest observed viral load in the current study was more than 6 trillion virions per mL. “It is remarkable to consider that this individual was on campus and reported no symptoms at our testing site,” the researchers wrote.

In contrast, the lowest viral load detected was 8 virions per mL.

Although more research is needed, the investigators noted that “a strong implication is that these individuals who are viral ‘super carriers’ may also be ‘superspreaders.’ ”

Some of the study authors have financial ties to companies that offer commercial SARS-CoV-2 testing, including Darwin Biosciences, TUMI Genomics, Faze Medicines, and Arpeggio Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Online patient reviews and HIPAA

In 2013, a California hospital paid $275,000 to settle claims that it violated the HIPAA privacy rule when it disclosed a patient’s health information in response to a negative online review. More recently, a Texas dental practice paid a substantial fine to the Department of Health & Human Services, which enforces HIPAA, after it responded to unfavorable Yelp reviews with patient names and details of their health conditions, treatment plans, and cost information. In addition to the fine, the practice agreed to 2 years of monitoring by HHS for compliance with HIPAA rules.

Most physicians have had the unpleasant experience of finding a negative online review from a disgruntled patient or family member. Some are justified, many are not; either way, your first impulse will often be to post a response – but that is almost always a bad idea. “Social media is not the place for providers to discuss a patient’s care,” an HHS official said in a statement issued about the dental practice case in 2016. “Doctors and dentists must think carefully about patient privacy before responding to online reviews.”

Any information that could be used to identify a patient is a HIPAA breach. This is true even if the patient has already disclosed information, because doing so does not nullify their HIPAA rights, and HIPAA provides no exceptions for responses. Even acknowledging that the reviewer was in fact your patient could, in some cases, be considered a violation.

Responding to good reviews can get you in trouble too, for the same reasons. In 2016, a physical therapy practice paid a $25,000 fine after it posted patient testimonials, “including full names and full-face photographic images to its website without obtaining valid, HIPAA-compliant authorizations.”

And by the way, most malpractice policies specifically exclude disciplinary fines and settlements from coverage.

All of that said,

- Ignore them. This is your best choice most of the time. Most negative reviews have minimal impact and simply do not deserve a response; responding may pour fuel on the fire. Besides, an occasional negative review actually lends credibility to a reviewing site and to the positive reviews posted on that site. Polls show that readers are suspicious of sites that contain only rave reviews. They assume such reviews have been “whitewashed” – or just fabricated.

- Solicit more reviews to that site. The more you can obtain, the less impact any complaints will have, since you know the overwhelming majority of your patients are happy with your care and will post a positive review if asked. Solicit them on your website, on social media, or in your email reminders. To be clear, you must encourage reviews from all patients, whether they have had a positive experience or not. If you invite only the satisfied ones, you are “filtering,” which can be perceived as false or deceptive advertising. (Google calls it “review-gating,” and according to their guidelines, if they catch you doing it they will remove all of your reviews.)

- Respond politely. In those rare cases where you feel you must respond, do so without acknowledging that the individual was a patient, or disclosing any information that may be linked to the patient. For example, you can say that you provide excellent and appropriate care, or describe your general policies. Be polite, professional, and sensitive to the patient’s position. Readers tend to respect and sympathize with a doctor who responds in a professional, respectful manner and does not trash the complainant in retaliation.

- Take the discussion offline. Sometimes the person posting the review is just frustrated and wants to be heard. In those cases, consider contacting the patient and offering to discuss their concerns privately. If you cannot resolve your differences, try to get the patient’s written permission to post a response to their review. If they refuse, you can explain that, thereby capturing the moral high ground.

If the review contains false or defamatory content, that’s a different situation entirely; you will probably need to consult your attorney.

Regardless of how you handle negative reviews, be sure to learn from them. Your critics, as the song goes, are not always evil – and not always wrong. Complaints give you a chance to review your office policies and procedures and your own conduct, identify weaknesses, and make changes as necessary. At the very least, the exercise will help you to avoid similar complaints in the future. Don’t let valuable opportunities like that pass you by.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In 2013, a California hospital paid $275,000 to settle claims that it violated the HIPAA privacy rule when it disclosed a patient’s health information in response to a negative online review. More recently, a Texas dental practice paid a substantial fine to the Department of Health & Human Services, which enforces HIPAA, after it responded to unfavorable Yelp reviews with patient names and details of their health conditions, treatment plans, and cost information. In addition to the fine, the practice agreed to 2 years of monitoring by HHS for compliance with HIPAA rules.

Most physicians have had the unpleasant experience of finding a negative online review from a disgruntled patient or family member. Some are justified, many are not; either way, your first impulse will often be to post a response – but that is almost always a bad idea. “Social media is not the place for providers to discuss a patient’s care,” an HHS official said in a statement issued about the dental practice case in 2016. “Doctors and dentists must think carefully about patient privacy before responding to online reviews.”

Any information that could be used to identify a patient is a HIPAA breach. This is true even if the patient has already disclosed information, because doing so does not nullify their HIPAA rights, and HIPAA provides no exceptions for responses. Even acknowledging that the reviewer was in fact your patient could, in some cases, be considered a violation.

Responding to good reviews can get you in trouble too, for the same reasons. In 2016, a physical therapy practice paid a $25,000 fine after it posted patient testimonials, “including full names and full-face photographic images to its website without obtaining valid, HIPAA-compliant authorizations.”

And by the way, most malpractice policies specifically exclude disciplinary fines and settlements from coverage.

All of that said,

- Ignore them. This is your best choice most of the time. Most negative reviews have minimal impact and simply do not deserve a response; responding may pour fuel on the fire. Besides, an occasional negative review actually lends credibility to a reviewing site and to the positive reviews posted on that site. Polls show that readers are suspicious of sites that contain only rave reviews. They assume such reviews have been “whitewashed” – or just fabricated.

- Solicit more reviews to that site. The more you can obtain, the less impact any complaints will have, since you know the overwhelming majority of your patients are happy with your care and will post a positive review if asked. Solicit them on your website, on social media, or in your email reminders. To be clear, you must encourage reviews from all patients, whether they have had a positive experience or not. If you invite only the satisfied ones, you are “filtering,” which can be perceived as false or deceptive advertising. (Google calls it “review-gating,” and according to their guidelines, if they catch you doing it they will remove all of your reviews.)

- Respond politely. In those rare cases where you feel you must respond, do so without acknowledging that the individual was a patient, or disclosing any information that may be linked to the patient. For example, you can say that you provide excellent and appropriate care, or describe your general policies. Be polite, professional, and sensitive to the patient’s position. Readers tend to respect and sympathize with a doctor who responds in a professional, respectful manner and does not trash the complainant in retaliation.

- Take the discussion offline. Sometimes the person posting the review is just frustrated and wants to be heard. In those cases, consider contacting the patient and offering to discuss their concerns privately. If you cannot resolve your differences, try to get the patient’s written permission to post a response to their review. If they refuse, you can explain that, thereby capturing the moral high ground.

If the review contains false or defamatory content, that’s a different situation entirely; you will probably need to consult your attorney.

Regardless of how you handle negative reviews, be sure to learn from them. Your critics, as the song goes, are not always evil – and not always wrong. Complaints give you a chance to review your office policies and procedures and your own conduct, identify weaknesses, and make changes as necessary. At the very least, the exercise will help you to avoid similar complaints in the future. Don’t let valuable opportunities like that pass you by.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In 2013, a California hospital paid $275,000 to settle claims that it violated the HIPAA privacy rule when it disclosed a patient’s health information in response to a negative online review. More recently, a Texas dental practice paid a substantial fine to the Department of Health & Human Services, which enforces HIPAA, after it responded to unfavorable Yelp reviews with patient names and details of their health conditions, treatment plans, and cost information. In addition to the fine, the practice agreed to 2 years of monitoring by HHS for compliance with HIPAA rules.

Most physicians have had the unpleasant experience of finding a negative online review from a disgruntled patient or family member. Some are justified, many are not; either way, your first impulse will often be to post a response – but that is almost always a bad idea. “Social media is not the place for providers to discuss a patient’s care,” an HHS official said in a statement issued about the dental practice case in 2016. “Doctors and dentists must think carefully about patient privacy before responding to online reviews.”

Any information that could be used to identify a patient is a HIPAA breach. This is true even if the patient has already disclosed information, because doing so does not nullify their HIPAA rights, and HIPAA provides no exceptions for responses. Even acknowledging that the reviewer was in fact your patient could, in some cases, be considered a violation.

Responding to good reviews can get you in trouble too, for the same reasons. In 2016, a physical therapy practice paid a $25,000 fine after it posted patient testimonials, “including full names and full-face photographic images to its website without obtaining valid, HIPAA-compliant authorizations.”

And by the way, most malpractice policies specifically exclude disciplinary fines and settlements from coverage.

All of that said,

- Ignore them. This is your best choice most of the time. Most negative reviews have minimal impact and simply do not deserve a response; responding may pour fuel on the fire. Besides, an occasional negative review actually lends credibility to a reviewing site and to the positive reviews posted on that site. Polls show that readers are suspicious of sites that contain only rave reviews. They assume such reviews have been “whitewashed” – or just fabricated.

- Solicit more reviews to that site. The more you can obtain, the less impact any complaints will have, since you know the overwhelming majority of your patients are happy with your care and will post a positive review if asked. Solicit them on your website, on social media, or in your email reminders. To be clear, you must encourage reviews from all patients, whether they have had a positive experience or not. If you invite only the satisfied ones, you are “filtering,” which can be perceived as false or deceptive advertising. (Google calls it “review-gating,” and according to their guidelines, if they catch you doing it they will remove all of your reviews.)

- Respond politely. In those rare cases where you feel you must respond, do so without acknowledging that the individual was a patient, or disclosing any information that may be linked to the patient. For example, you can say that you provide excellent and appropriate care, or describe your general policies. Be polite, professional, and sensitive to the patient’s position. Readers tend to respect and sympathize with a doctor who responds in a professional, respectful manner and does not trash the complainant in retaliation.

- Take the discussion offline. Sometimes the person posting the review is just frustrated and wants to be heard. In those cases, consider contacting the patient and offering to discuss their concerns privately. If you cannot resolve your differences, try to get the patient’s written permission to post a response to their review. If they refuse, you can explain that, thereby capturing the moral high ground.

If the review contains false or defamatory content, that’s a different situation entirely; you will probably need to consult your attorney.

Regardless of how you handle negative reviews, be sure to learn from them. Your critics, as the song goes, are not always evil – and not always wrong. Complaints give you a chance to review your office policies and procedures and your own conduct, identify weaknesses, and make changes as necessary. At the very least, the exercise will help you to avoid similar complaints in the future. Don’t let valuable opportunities like that pass you by.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Fremanezumab effective in patients with difficult-to-treat migraine

Key clinical point: Quarterly and monthly dose regimens of fremanezumab effectively reduced the average monthly migraine days (MMD) vs. placebo in patients with difficult-to-treat migraine irrespective of country and continents.

Major finding: Reduction in MMD over 12 weeks was significantly higher with fremanezumab dose regimens vs. placebo in 3 top-recruiting countries including Czech Republic (least squares mean difference [LSMD]: quarterly, −1.9; monthly, −3.0), the United States (LSMD: quarterly, −3.7; monthly, −4.2), and Finland (LSMD: quarterly, −3.0; monthly, −3.9; P less than or equal to .01 for all).

Study details: Data come from an exploratory analysis of phase 3b FOCUS study including 838 patients with episodic or chronic migraine who had an inadequate response to 2-4 migraine preventive medication classes and were randomly allocated to either quarterly fremanezumab, monthly fremanezumab, or matched placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals. Some of the authors reported receiving research grants and/or personal compensation from multiple sources, including Teva Pharmaceuticals. Some of the authors declared being current/former employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Spierings ELH et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Apr 16. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01232-8.

Key clinical point: Quarterly and monthly dose regimens of fremanezumab effectively reduced the average monthly migraine days (MMD) vs. placebo in patients with difficult-to-treat migraine irrespective of country and continents.

Major finding: Reduction in MMD over 12 weeks was significantly higher with fremanezumab dose regimens vs. placebo in 3 top-recruiting countries including Czech Republic (least squares mean difference [LSMD]: quarterly, −1.9; monthly, −3.0), the United States (LSMD: quarterly, −3.7; monthly, −4.2), and Finland (LSMD: quarterly, −3.0; monthly, −3.9; P less than or equal to .01 for all).

Study details: Data come from an exploratory analysis of phase 3b FOCUS study including 838 patients with episodic or chronic migraine who had an inadequate response to 2-4 migraine preventive medication classes and were randomly allocated to either quarterly fremanezumab, monthly fremanezumab, or matched placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals. Some of the authors reported receiving research grants and/or personal compensation from multiple sources, including Teva Pharmaceuticals. Some of the authors declared being current/former employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Spierings ELH et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Apr 16. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01232-8.

Key clinical point: Quarterly and monthly dose regimens of fremanezumab effectively reduced the average monthly migraine days (MMD) vs. placebo in patients with difficult-to-treat migraine irrespective of country and continents.

Major finding: Reduction in MMD over 12 weeks was significantly higher with fremanezumab dose regimens vs. placebo in 3 top-recruiting countries including Czech Republic (least squares mean difference [LSMD]: quarterly, −1.9; monthly, −3.0), the United States (LSMD: quarterly, −3.7; monthly, −4.2), and Finland (LSMD: quarterly, −3.0; monthly, −3.9; P less than or equal to .01 for all).

Study details: Data come from an exploratory analysis of phase 3b FOCUS study including 838 patients with episodic or chronic migraine who had an inadequate response to 2-4 migraine preventive medication classes and were randomly allocated to either quarterly fremanezumab, monthly fremanezumab, or matched placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals. Some of the authors reported receiving research grants and/or personal compensation from multiple sources, including Teva Pharmaceuticals. Some of the authors declared being current/former employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Spierings ELH et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Apr 16. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01232-8.

Real-world evidence supports benefits of erenumab for chronic migraine

Key clinical point: In a predominantly refractory chronic migraine population, the initiation of erenumab reduced the frequency of monthly headache and migraine days and shortened the duration of headache/migraine attack.

Major finding: After erenumab initiation, mean headache/migraine days per month and mean headache/migraine duration per attack decreased by a mean of 5.6 days and 5.1 hours, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective chart review of 1,034 patients with chronic migraine who were treated with erenumab for at least 3 consecutive months at 5 major headache centers in the U.S.A.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Amgen Inc (Thousand Oaks, CA). Some of the authors declared being employees of Analysis Group and Amgen Inc. Z Ahmed and A Blumenfeld served as consultants and on the advisory board for Amgen Inc. The other authors had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Faust E et al. Neurol Ther. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00245-4.

Key clinical point: In a predominantly refractory chronic migraine population, the initiation of erenumab reduced the frequency of monthly headache and migraine days and shortened the duration of headache/migraine attack.

Major finding: After erenumab initiation, mean headache/migraine days per month and mean headache/migraine duration per attack decreased by a mean of 5.6 days and 5.1 hours, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective chart review of 1,034 patients with chronic migraine who were treated with erenumab for at least 3 consecutive months at 5 major headache centers in the U.S.A.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Amgen Inc (Thousand Oaks, CA). Some of the authors declared being employees of Analysis Group and Amgen Inc. Z Ahmed and A Blumenfeld served as consultants and on the advisory board for Amgen Inc. The other authors had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Faust E et al. Neurol Ther. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00245-4.

Key clinical point: In a predominantly refractory chronic migraine population, the initiation of erenumab reduced the frequency of monthly headache and migraine days and shortened the duration of headache/migraine attack.

Major finding: After erenumab initiation, mean headache/migraine days per month and mean headache/migraine duration per attack decreased by a mean of 5.6 days and 5.1 hours, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective chart review of 1,034 patients with chronic migraine who were treated with erenumab for at least 3 consecutive months at 5 major headache centers in the U.S.A.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Amgen Inc (Thousand Oaks, CA). Some of the authors declared being employees of Analysis Group and Amgen Inc. Z Ahmed and A Blumenfeld served as consultants and on the advisory board for Amgen Inc. The other authors had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Faust E et al. Neurol Ther. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00245-4.

Migraine: Lasmiditan more effective when initiated at mild pain intensity

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan showed relatively better efficacy outcomes in migraine attacks when initiated at mild vs. moderate or severe pain.

Major finding: In GLADIATOR, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with lasmiditan (200 mg) at mild vs. moderate or severe pain achieved 2-hour pain freedom (PF; both P less than .001) and 24-hour sustained PF (SPF; P less than .05). In SAMURAI and SPARTAN, numerically higher proportion of patients treated with lasmiditan (200 mg) at mild vs. moderate or severe pain achieved 2-hour PF (45.5% vs. 37.6% or 29.4%) and 24-hour SPF (31.8% vs. 22.7% or 15.0%).

Study details: Findings are from pooled analysis of phase 3 studies SAMURAI, SPARTAN, and GLADIATOR.