User login

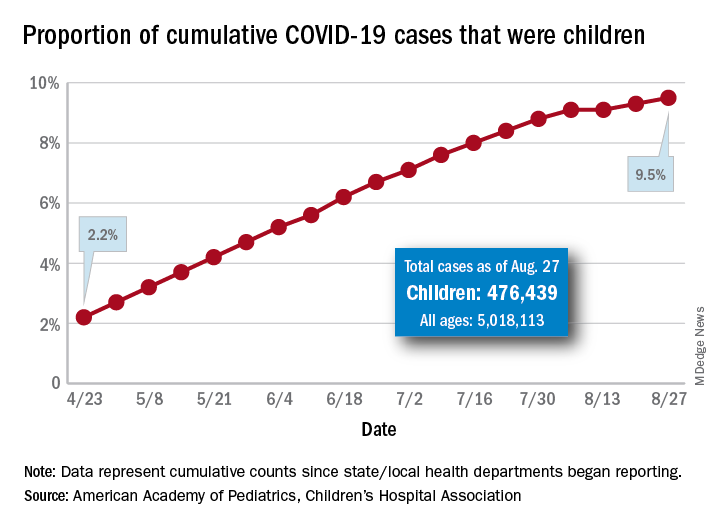

Latest report adds almost 44,000 child COVID-19 cases in 1 week

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

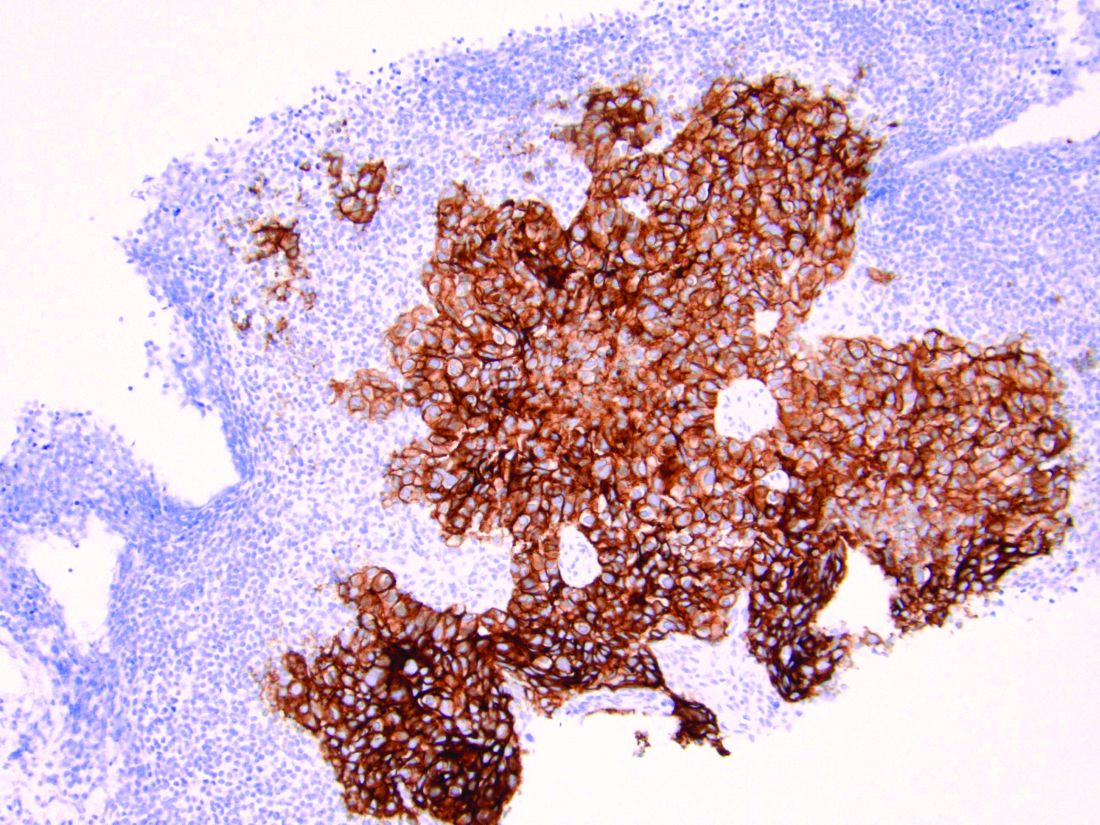

The new cases bring the cumulative number of infected children to over 476,000, and that figure represents 9.5% of the over 5 million COVID-19 cases reported among all ages, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report. The cumulative number of children covers 49 states (New York is not reporting age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

From lowest to highest, the states occupying opposite ends of the cumulative proportion spectrum are New Jersey at 3.4% – New York City was lower with a 3.2% figure but is not a state – and Wyoming at 18.3%, the report showed.

Children represent more than 15% of all reported COVID-19 cases in five other states: Tennessee (17.1%), North Dakota (16.0%), Alaska (15.9%), New Mexico (15.7%), and Minnesota (15.1%). The states just above New Jersey are Florida (5.8%), Connecticut (5.9%), and Massachusetts (6.7%). Texas has a rate of 5.6% but has reported age for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Children make up a much lower share of COVID-19 hospitalizations – 1.7% of the cumulative number for all ages – although that figure has been slowly rising over the course of the pandemic: it was 1.2% on July 9 and 0.9% on May 8. Arizona (4.1%) is the highest of the 22 states reporting age for hospitalizations and Hawaii (0.6%) is the lowest, based on the AAP/CHA data.

Mortality figures for children continue to be even lower. Nationwide, 0.07% of all COVID-19 deaths occurred in children, and 19 of the 43 states reporting age distributions have had no deaths yet. Pediatric deaths totaled 101 as of Aug. 27, the two groups reported.

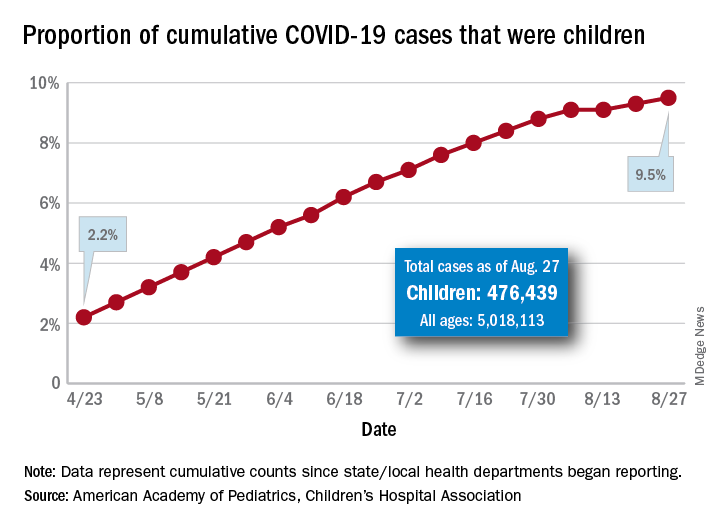

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The new cases bring the cumulative number of infected children to over 476,000, and that figure represents 9.5% of the over 5 million COVID-19 cases reported among all ages, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report. The cumulative number of children covers 49 states (New York is not reporting age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

From lowest to highest, the states occupying opposite ends of the cumulative proportion spectrum are New Jersey at 3.4% – New York City was lower with a 3.2% figure but is not a state – and Wyoming at 18.3%, the report showed.

Children represent more than 15% of all reported COVID-19 cases in five other states: Tennessee (17.1%), North Dakota (16.0%), Alaska (15.9%), New Mexico (15.7%), and Minnesota (15.1%). The states just above New Jersey are Florida (5.8%), Connecticut (5.9%), and Massachusetts (6.7%). Texas has a rate of 5.6% but has reported age for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Children make up a much lower share of COVID-19 hospitalizations – 1.7% of the cumulative number for all ages – although that figure has been slowly rising over the course of the pandemic: it was 1.2% on July 9 and 0.9% on May 8. Arizona (4.1%) is the highest of the 22 states reporting age for hospitalizations and Hawaii (0.6%) is the lowest, based on the AAP/CHA data.

Mortality figures for children continue to be even lower. Nationwide, 0.07% of all COVID-19 deaths occurred in children, and 19 of the 43 states reporting age distributions have had no deaths yet. Pediatric deaths totaled 101 as of Aug. 27, the two groups reported.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The new cases bring the cumulative number of infected children to over 476,000, and that figure represents 9.5% of the over 5 million COVID-19 cases reported among all ages, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report. The cumulative number of children covers 49 states (New York is not reporting age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

From lowest to highest, the states occupying opposite ends of the cumulative proportion spectrum are New Jersey at 3.4% – New York City was lower with a 3.2% figure but is not a state – and Wyoming at 18.3%, the report showed.

Children represent more than 15% of all reported COVID-19 cases in five other states: Tennessee (17.1%), North Dakota (16.0%), Alaska (15.9%), New Mexico (15.7%), and Minnesota (15.1%). The states just above New Jersey are Florida (5.8%), Connecticut (5.9%), and Massachusetts (6.7%). Texas has a rate of 5.6% but has reported age for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Children make up a much lower share of COVID-19 hospitalizations – 1.7% of the cumulative number for all ages – although that figure has been slowly rising over the course of the pandemic: it was 1.2% on July 9 and 0.9% on May 8. Arizona (4.1%) is the highest of the 22 states reporting age for hospitalizations and Hawaii (0.6%) is the lowest, based on the AAP/CHA data.

Mortality figures for children continue to be even lower. Nationwide, 0.07% of all COVID-19 deaths occurred in children, and 19 of the 43 states reporting age distributions have had no deaths yet. Pediatric deaths totaled 101 as of Aug. 27, the two groups reported.

First randomized trial reassures on ACEIs, ARBs in COVID-19

The first randomized study to compare continuing versus stopping ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients with COVID-19 has shown no difference in key outcomes between the two approaches.

The BRACE CORONA trial – conducted in patients had been taking an ACE inhibitor or an ARB on a long-term basis and who were subsequently hospitalized with COVID-19 – showed no difference in the primary endpoint of number of days alive and out of hospital among those whose medication was suspended for 30 days and those who continued undergoing treatment with these agents.

“Because these data indicate that there is no clinical benefit from routinely interrupting these medications in hospitalized patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, they should generally be continued for those with an indication,” principal investigator Renato Lopes, MD, of Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., concluded.

The BRACE CORONA trial was presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 on Sept. 1.

Dr. Lopes explained that there are two conflicting hypotheses about the role of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in COVID-19.

One hypothesis suggests that use of these drugs could be harmful by increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors (which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells), thus potentially enhancing viral binding and viral entry. The other suggests that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be protective by reducing production of angiotensin II and enhancing the generation of angiotensin 1-7, which attenuates inflammation and fibrosis and therefore could attenuate lung injury.

The BRACE CORONA trial was an academic-led randomized study that tested two strategies: temporarily stopping the ACE inhibitor/ARB for 30 days or continuing these drugs for patients who had been taking these medications on a long-term basis and were hospitalized with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

The primary outcome was the number of days alive and out of hospital at 30 days. Patients who were using more than three antihypertensive drugs or sacubitril/valsartan or who were hemodynamically unstable at presentation were excluded from the study.

The trial enrolled 659 patients from 29 sites in Brazil. The mean age of patients was 56 years, 40% were women, and 52% were obese. ACE inhibitors were being taken by 15% of the trial participants; ARBs were being taken by 85%. The median duration of ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment was 5 years.

Patients were a median of 6 days from COVID-19 symptom onset. For 30% of the patients, oxygen saturation was below 94% at entry. In terms of COVID-19 symptoms, 57% were classified as mild, and 43% as moderate.

Those with severe COVID-19 symptoms who needed intubation or vasoactive drugs were excluded. Antihypertensive therapy would generally be discontinued in these patients anyway, Dr. Lopes said.

Results showed that the average number of days alive and out of hospital was 21.9 days for patients who stopped taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 22.9 days for patients who continued taking these medications. The average difference between groups was –1.1 days.

The average ratio of days alive and out of hospital between the suspending and continuing groups was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90-1.01; P = .09).

The proportion of patients alive and out of hospital by the end of 30 days in the suspending ACE inhibitor/ARB group was 91.8% versus 95% in the continuing group.

A similar 30-day mortality rate was seen for patients who continued and those who suspended ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy, at 2.8% and 2.7%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.97). The median number of days that patients were alive and out of hospital was 25 in both groups.

Dr. Lopes said that there was no difference between the two groups with regard to many other secondary outcomes. These included COVID-19 disease progression (need for intubation, ventilation, need for vasoactive drugs, or imaging results) and cardiovascular endpoints (MI, stroke, thromboembolic events, worsening heart failure, myocarditis, or hypertensive crisis).

“Our results endorse with reliable and more definitive data what most medical and cardiovascular societies are recommending – that patients do not stop ACE inhibitor or ARB medication. This has been based on observational data so far, but BRACE CORONA now provides randomized data to support this recommendation,” Dr. Lopes concluded.

Dr. Lopes noted that several subgroups had been prespecified for analysis. Factors included age, obesity, difference between ACE inhibitors/ARBs, difference in oxygen saturation at presentation, time since COVID-19 symptom onset, degree of lung involvement on CT, and symptom severity on presentation.

“We saw very consistent effects of our main findings across all these subgroups, and we plan to report more details of these in the near future,” he said.

Protective for older patients?

The discussant of the study at the ESC Hotline session, Gianfranco Parati, MD, University of Milan-Bicocca and San Luca Hospital, Milan, congratulated Lopes and his team for conducting this important trial at such a difficult time.

He pointed out that patients in the BRACE CORONA trial were quite young (average age, 56 years) and that observational data so far suggest that ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a stronger protective effect in older COVID-19 patients.

He also noted that the percentage of patients alive and out of hospital at 30 days was higher for the patients who continued on treatment in this study (95% vs. 91.8%), which suggested an advantage in maintaining the medication.

Dr. Lopes replied that one-quarter of the population in the BRACE CORONA trial was older than 65 years, which he said was a “reasonable number.”

“Subgroup analysis by age did not show a significant interaction, but the effect of continuing treatment does seem to be more favorable in older patients and also in those who were sicker and had more comorbidities,” he added.

Dr. Parati also suggested that it would have been difficult to discern differences between ACE inhibitors and ARBs in the BRACE CORONA trial, because so few patents were taking ACE inhibitors; the follow-up period of 30 days was relatively short, inasmuch as these drugs may have long-term effects; and it would have been difficult to show differences in the main outcomes used in the study – mortality and time out of hospital – in these patients with mild to moderate disease.

Franz H. Messerli, MD, and Christoph Gräni, MD, University of Bern (Switzerland), said in a joint statement: “The BRACE CORONA trial provides answers to what we know from retrospective studies: if you have already COVID, don’t stop renin-angiotensin system blocker medication.”

But they added that the study does not answer the question about the risk/benefit of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with regard to possible enhanced viral entry through the ACE2 receptor. “What about all those on these drugs who are not infected with COVID? Do they need to stop them? We simply don’t know yet,” they said.

Dr. Messerli and Dr. Gräni added that they would like to see a study that compared patients before SARS-CoV-2 infection who were without hypertension, patients with hypertension who were taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and patients with hypertension taking other antihypertensive drugs.

The BRACE CORONA trial was sponsored by D’Or Institute for Research and Education and the Brazilian Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Lopes has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The first randomized study to compare continuing versus stopping ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients with COVID-19 has shown no difference in key outcomes between the two approaches.

The BRACE CORONA trial – conducted in patients had been taking an ACE inhibitor or an ARB on a long-term basis and who were subsequently hospitalized with COVID-19 – showed no difference in the primary endpoint of number of days alive and out of hospital among those whose medication was suspended for 30 days and those who continued undergoing treatment with these agents.

“Because these data indicate that there is no clinical benefit from routinely interrupting these medications in hospitalized patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, they should generally be continued for those with an indication,” principal investigator Renato Lopes, MD, of Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., concluded.

The BRACE CORONA trial was presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 on Sept. 1.

Dr. Lopes explained that there are two conflicting hypotheses about the role of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in COVID-19.

One hypothesis suggests that use of these drugs could be harmful by increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors (which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells), thus potentially enhancing viral binding and viral entry. The other suggests that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be protective by reducing production of angiotensin II and enhancing the generation of angiotensin 1-7, which attenuates inflammation and fibrosis and therefore could attenuate lung injury.

The BRACE CORONA trial was an academic-led randomized study that tested two strategies: temporarily stopping the ACE inhibitor/ARB for 30 days or continuing these drugs for patients who had been taking these medications on a long-term basis and were hospitalized with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

The primary outcome was the number of days alive and out of hospital at 30 days. Patients who were using more than three antihypertensive drugs or sacubitril/valsartan or who were hemodynamically unstable at presentation were excluded from the study.

The trial enrolled 659 patients from 29 sites in Brazil. The mean age of patients was 56 years, 40% were women, and 52% were obese. ACE inhibitors were being taken by 15% of the trial participants; ARBs were being taken by 85%. The median duration of ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment was 5 years.

Patients were a median of 6 days from COVID-19 symptom onset. For 30% of the patients, oxygen saturation was below 94% at entry. In terms of COVID-19 symptoms, 57% were classified as mild, and 43% as moderate.

Those with severe COVID-19 symptoms who needed intubation or vasoactive drugs were excluded. Antihypertensive therapy would generally be discontinued in these patients anyway, Dr. Lopes said.

Results showed that the average number of days alive and out of hospital was 21.9 days for patients who stopped taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 22.9 days for patients who continued taking these medications. The average difference between groups was –1.1 days.

The average ratio of days alive and out of hospital between the suspending and continuing groups was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90-1.01; P = .09).

The proportion of patients alive and out of hospital by the end of 30 days in the suspending ACE inhibitor/ARB group was 91.8% versus 95% in the continuing group.

A similar 30-day mortality rate was seen for patients who continued and those who suspended ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy, at 2.8% and 2.7%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.97). The median number of days that patients were alive and out of hospital was 25 in both groups.

Dr. Lopes said that there was no difference between the two groups with regard to many other secondary outcomes. These included COVID-19 disease progression (need for intubation, ventilation, need for vasoactive drugs, or imaging results) and cardiovascular endpoints (MI, stroke, thromboembolic events, worsening heart failure, myocarditis, or hypertensive crisis).

“Our results endorse with reliable and more definitive data what most medical and cardiovascular societies are recommending – that patients do not stop ACE inhibitor or ARB medication. This has been based on observational data so far, but BRACE CORONA now provides randomized data to support this recommendation,” Dr. Lopes concluded.

Dr. Lopes noted that several subgroups had been prespecified for analysis. Factors included age, obesity, difference between ACE inhibitors/ARBs, difference in oxygen saturation at presentation, time since COVID-19 symptom onset, degree of lung involvement on CT, and symptom severity on presentation.

“We saw very consistent effects of our main findings across all these subgroups, and we plan to report more details of these in the near future,” he said.

Protective for older patients?

The discussant of the study at the ESC Hotline session, Gianfranco Parati, MD, University of Milan-Bicocca and San Luca Hospital, Milan, congratulated Lopes and his team for conducting this important trial at such a difficult time.

He pointed out that patients in the BRACE CORONA trial were quite young (average age, 56 years) and that observational data so far suggest that ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a stronger protective effect in older COVID-19 patients.

He also noted that the percentage of patients alive and out of hospital at 30 days was higher for the patients who continued on treatment in this study (95% vs. 91.8%), which suggested an advantage in maintaining the medication.

Dr. Lopes replied that one-quarter of the population in the BRACE CORONA trial was older than 65 years, which he said was a “reasonable number.”

“Subgroup analysis by age did not show a significant interaction, but the effect of continuing treatment does seem to be more favorable in older patients and also in those who were sicker and had more comorbidities,” he added.

Dr. Parati also suggested that it would have been difficult to discern differences between ACE inhibitors and ARBs in the BRACE CORONA trial, because so few patents were taking ACE inhibitors; the follow-up period of 30 days was relatively short, inasmuch as these drugs may have long-term effects; and it would have been difficult to show differences in the main outcomes used in the study – mortality and time out of hospital – in these patients with mild to moderate disease.

Franz H. Messerli, MD, and Christoph Gräni, MD, University of Bern (Switzerland), said in a joint statement: “The BRACE CORONA trial provides answers to what we know from retrospective studies: if you have already COVID, don’t stop renin-angiotensin system blocker medication.”

But they added that the study does not answer the question about the risk/benefit of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with regard to possible enhanced viral entry through the ACE2 receptor. “What about all those on these drugs who are not infected with COVID? Do they need to stop them? We simply don’t know yet,” they said.

Dr. Messerli and Dr. Gräni added that they would like to see a study that compared patients before SARS-CoV-2 infection who were without hypertension, patients with hypertension who were taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and patients with hypertension taking other antihypertensive drugs.

The BRACE CORONA trial was sponsored by D’Or Institute for Research and Education and the Brazilian Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Lopes has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The first randomized study to compare continuing versus stopping ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients with COVID-19 has shown no difference in key outcomes between the two approaches.

The BRACE CORONA trial – conducted in patients had been taking an ACE inhibitor or an ARB on a long-term basis and who were subsequently hospitalized with COVID-19 – showed no difference in the primary endpoint of number of days alive and out of hospital among those whose medication was suspended for 30 days and those who continued undergoing treatment with these agents.

“Because these data indicate that there is no clinical benefit from routinely interrupting these medications in hospitalized patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, they should generally be continued for those with an indication,” principal investigator Renato Lopes, MD, of Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., concluded.

The BRACE CORONA trial was presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 on Sept. 1.

Dr. Lopes explained that there are two conflicting hypotheses about the role of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in COVID-19.

One hypothesis suggests that use of these drugs could be harmful by increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors (which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells), thus potentially enhancing viral binding and viral entry. The other suggests that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be protective by reducing production of angiotensin II and enhancing the generation of angiotensin 1-7, which attenuates inflammation and fibrosis and therefore could attenuate lung injury.

The BRACE CORONA trial was an academic-led randomized study that tested two strategies: temporarily stopping the ACE inhibitor/ARB for 30 days or continuing these drugs for patients who had been taking these medications on a long-term basis and were hospitalized with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

The primary outcome was the number of days alive and out of hospital at 30 days. Patients who were using more than three antihypertensive drugs or sacubitril/valsartan or who were hemodynamically unstable at presentation were excluded from the study.

The trial enrolled 659 patients from 29 sites in Brazil. The mean age of patients was 56 years, 40% were women, and 52% were obese. ACE inhibitors were being taken by 15% of the trial participants; ARBs were being taken by 85%. The median duration of ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment was 5 years.

Patients were a median of 6 days from COVID-19 symptom onset. For 30% of the patients, oxygen saturation was below 94% at entry. In terms of COVID-19 symptoms, 57% were classified as mild, and 43% as moderate.

Those with severe COVID-19 symptoms who needed intubation or vasoactive drugs were excluded. Antihypertensive therapy would generally be discontinued in these patients anyway, Dr. Lopes said.

Results showed that the average number of days alive and out of hospital was 21.9 days for patients who stopped taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 22.9 days for patients who continued taking these medications. The average difference between groups was –1.1 days.

The average ratio of days alive and out of hospital between the suspending and continuing groups was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90-1.01; P = .09).

The proportion of patients alive and out of hospital by the end of 30 days in the suspending ACE inhibitor/ARB group was 91.8% versus 95% in the continuing group.

A similar 30-day mortality rate was seen for patients who continued and those who suspended ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy, at 2.8% and 2.7%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.97). The median number of days that patients were alive and out of hospital was 25 in both groups.

Dr. Lopes said that there was no difference between the two groups with regard to many other secondary outcomes. These included COVID-19 disease progression (need for intubation, ventilation, need for vasoactive drugs, or imaging results) and cardiovascular endpoints (MI, stroke, thromboembolic events, worsening heart failure, myocarditis, or hypertensive crisis).

“Our results endorse with reliable and more definitive data what most medical and cardiovascular societies are recommending – that patients do not stop ACE inhibitor or ARB medication. This has been based on observational data so far, but BRACE CORONA now provides randomized data to support this recommendation,” Dr. Lopes concluded.

Dr. Lopes noted that several subgroups had been prespecified for analysis. Factors included age, obesity, difference between ACE inhibitors/ARBs, difference in oxygen saturation at presentation, time since COVID-19 symptom onset, degree of lung involvement on CT, and symptom severity on presentation.

“We saw very consistent effects of our main findings across all these subgroups, and we plan to report more details of these in the near future,” he said.

Protective for older patients?

The discussant of the study at the ESC Hotline session, Gianfranco Parati, MD, University of Milan-Bicocca and San Luca Hospital, Milan, congratulated Lopes and his team for conducting this important trial at such a difficult time.

He pointed out that patients in the BRACE CORONA trial were quite young (average age, 56 years) and that observational data so far suggest that ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a stronger protective effect in older COVID-19 patients.

He also noted that the percentage of patients alive and out of hospital at 30 days was higher for the patients who continued on treatment in this study (95% vs. 91.8%), which suggested an advantage in maintaining the medication.

Dr. Lopes replied that one-quarter of the population in the BRACE CORONA trial was older than 65 years, which he said was a “reasonable number.”

“Subgroup analysis by age did not show a significant interaction, but the effect of continuing treatment does seem to be more favorable in older patients and also in those who were sicker and had more comorbidities,” he added.

Dr. Parati also suggested that it would have been difficult to discern differences between ACE inhibitors and ARBs in the BRACE CORONA trial, because so few patents were taking ACE inhibitors; the follow-up period of 30 days was relatively short, inasmuch as these drugs may have long-term effects; and it would have been difficult to show differences in the main outcomes used in the study – mortality and time out of hospital – in these patients with mild to moderate disease.

Franz H. Messerli, MD, and Christoph Gräni, MD, University of Bern (Switzerland), said in a joint statement: “The BRACE CORONA trial provides answers to what we know from retrospective studies: if you have already COVID, don’t stop renin-angiotensin system blocker medication.”

But they added that the study does not answer the question about the risk/benefit of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with regard to possible enhanced viral entry through the ACE2 receptor. “What about all those on these drugs who are not infected with COVID? Do they need to stop them? We simply don’t know yet,” they said.

Dr. Messerli and Dr. Gräni added that they would like to see a study that compared patients before SARS-CoV-2 infection who were without hypertension, patients with hypertension who were taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and patients with hypertension taking other antihypertensive drugs.

The BRACE CORONA trial was sponsored by D’Or Institute for Research and Education and the Brazilian Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Lopes has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19: In-hospital mortality data miss bigger picture of racial inequality

A recent study that reported no association between race and in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19 failed to capture broader health care inequities, according to a leading expert.

During an AGA FORWARD Program webinar, Darrell Gray II, MD, deputy director of the Center for Cancer Health Equity at Ohio State University in Columbus, noted that the study by Baligh R. Yehia, MD, and colleagues had several important limitations: specifically, a lack of data from before or after hospitalization, flawed neighborhood deprivation indices, and poorly characterized comorbidities.

While Dr. Yehia and colleagues described these limitations in their publication, Dr. Gray suggested that future studies evaluating race and health outcomes need to be “deliberate and intentional with collecting data.”

According to Dr. Gray, statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the APM Research Lab paint a more accurate picture of health care inequities. The CDC, for instance, reports that people who are Black are nearly five times as likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19, and approximately twice as likely to die from the disease, compared with those who are White. The APM Research Lab reports an even more striking relative mortality rate for Black Americans – almost four times higher than that of White Americans.

“People of color have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, whether it be by cases, hospitalizations, or deaths,” Dr. Gray said. “We have to think about why that is, and what has led to this.”

Dr. Gray emphasized that poorer outcomes among people of color are “not necessarily biological.”

“It’s the environment and social constructs that contribute to why there’s a disproportionate burden of chronic disease and why there’s a disproportionate burden of COVID-19,” he said.

According to Dr. Gray, disparate health care outcomes can be traced back to social determinants of health, which he and his colleagues highlighted in a June comment published in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

“Although much attention has focused on the high burden of chronic disease among [people of color], which predisposes them to poor outcomes if they acquire COVID-19, there is less recognition of the nonmedical health-related social needs and social determinants of health that represent the root causes of such health disparities,” they wrote.

Social determinants of health include an array of population factors, including economic stability, social and community context, neighborhood and environment, education, and access to health care.

For each, Dr. Gray encouraged comprehensive and nuanced assessment.

“Is there access to health care?” Dr. Gray asked. “Not just access in the sense of having insurance – certainly that’s a benefit – but if someone has insurance, can they get to where the health center is? Or is that something they might have to catch three buses and a cab to get to?”

Dr. Gray said that such obstacles are not outside the scope of the medical community.

“This is not beyond our responsibility ... to address social determinants of health,” Dr. Gray said.

When asked by a webinar attendee how the medical community can tackle racism, Dr. Gray offered several practical steps to move forward.

First, he suggested that clinicians and researchers listen to affected patient populations.

“Many of us, including clinicians, have been privileged to have their blinders on, if you will, to issues of racism that have been affecting our patients for a long time,” he said.

Second, Dr. Gray encouraged those who have learned to teach others.

“You need to start teaching your peers, your colleagues, your family, and friends about how racism affects patient outcomes.”

Third, he recommended that clinicians incorporate these lessons into routine practice, whether in a private or an academic setting.

“Are there ways in which you can refer patients to address social determinants of health? Are you capturing that information in your check-in materials?” Dr. Gray asked. “If you’re an investigator, when you’re doing research – whether it’s health disparities research or other – are you looking at your research through a health equity lens? Are you asking questions about social determinants of health?”

Finally, Dr. Gray called for stronger community engagement during design and conduction of clinical trials.

“People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care,” he said. “And they won’t know how much you care unless you’re visible, and unless you’re there, and these are sustainable relationships.”

The FORWARD program is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

A recent study that reported no association between race and in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19 failed to capture broader health care inequities, according to a leading expert.

During an AGA FORWARD Program webinar, Darrell Gray II, MD, deputy director of the Center for Cancer Health Equity at Ohio State University in Columbus, noted that the study by Baligh R. Yehia, MD, and colleagues had several important limitations: specifically, a lack of data from before or after hospitalization, flawed neighborhood deprivation indices, and poorly characterized comorbidities.

While Dr. Yehia and colleagues described these limitations in their publication, Dr. Gray suggested that future studies evaluating race and health outcomes need to be “deliberate and intentional with collecting data.”

According to Dr. Gray, statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the APM Research Lab paint a more accurate picture of health care inequities. The CDC, for instance, reports that people who are Black are nearly five times as likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19, and approximately twice as likely to die from the disease, compared with those who are White. The APM Research Lab reports an even more striking relative mortality rate for Black Americans – almost four times higher than that of White Americans.

“People of color have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, whether it be by cases, hospitalizations, or deaths,” Dr. Gray said. “We have to think about why that is, and what has led to this.”

Dr. Gray emphasized that poorer outcomes among people of color are “not necessarily biological.”

“It’s the environment and social constructs that contribute to why there’s a disproportionate burden of chronic disease and why there’s a disproportionate burden of COVID-19,” he said.

According to Dr. Gray, disparate health care outcomes can be traced back to social determinants of health, which he and his colleagues highlighted in a June comment published in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

“Although much attention has focused on the high burden of chronic disease among [people of color], which predisposes them to poor outcomes if they acquire COVID-19, there is less recognition of the nonmedical health-related social needs and social determinants of health that represent the root causes of such health disparities,” they wrote.

Social determinants of health include an array of population factors, including economic stability, social and community context, neighborhood and environment, education, and access to health care.

For each, Dr. Gray encouraged comprehensive and nuanced assessment.

“Is there access to health care?” Dr. Gray asked. “Not just access in the sense of having insurance – certainly that’s a benefit – but if someone has insurance, can they get to where the health center is? Or is that something they might have to catch three buses and a cab to get to?”

Dr. Gray said that such obstacles are not outside the scope of the medical community.

“This is not beyond our responsibility ... to address social determinants of health,” Dr. Gray said.

When asked by a webinar attendee how the medical community can tackle racism, Dr. Gray offered several practical steps to move forward.

First, he suggested that clinicians and researchers listen to affected patient populations.

“Many of us, including clinicians, have been privileged to have their blinders on, if you will, to issues of racism that have been affecting our patients for a long time,” he said.

Second, Dr. Gray encouraged those who have learned to teach others.

“You need to start teaching your peers, your colleagues, your family, and friends about how racism affects patient outcomes.”

Third, he recommended that clinicians incorporate these lessons into routine practice, whether in a private or an academic setting.

“Are there ways in which you can refer patients to address social determinants of health? Are you capturing that information in your check-in materials?” Dr. Gray asked. “If you’re an investigator, when you’re doing research – whether it’s health disparities research or other – are you looking at your research through a health equity lens? Are you asking questions about social determinants of health?”

Finally, Dr. Gray called for stronger community engagement during design and conduction of clinical trials.

“People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care,” he said. “And they won’t know how much you care unless you’re visible, and unless you’re there, and these are sustainable relationships.”

The FORWARD program is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

A recent study that reported no association between race and in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19 failed to capture broader health care inequities, according to a leading expert.

During an AGA FORWARD Program webinar, Darrell Gray II, MD, deputy director of the Center for Cancer Health Equity at Ohio State University in Columbus, noted that the study by Baligh R. Yehia, MD, and colleagues had several important limitations: specifically, a lack of data from before or after hospitalization, flawed neighborhood deprivation indices, and poorly characterized comorbidities.

While Dr. Yehia and colleagues described these limitations in their publication, Dr. Gray suggested that future studies evaluating race and health outcomes need to be “deliberate and intentional with collecting data.”

According to Dr. Gray, statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the APM Research Lab paint a more accurate picture of health care inequities. The CDC, for instance, reports that people who are Black are nearly five times as likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19, and approximately twice as likely to die from the disease, compared with those who are White. The APM Research Lab reports an even more striking relative mortality rate for Black Americans – almost four times higher than that of White Americans.

“People of color have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, whether it be by cases, hospitalizations, or deaths,” Dr. Gray said. “We have to think about why that is, and what has led to this.”

Dr. Gray emphasized that poorer outcomes among people of color are “not necessarily biological.”

“It’s the environment and social constructs that contribute to why there’s a disproportionate burden of chronic disease and why there’s a disproportionate burden of COVID-19,” he said.

According to Dr. Gray, disparate health care outcomes can be traced back to social determinants of health, which he and his colleagues highlighted in a June comment published in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

“Although much attention has focused on the high burden of chronic disease among [people of color], which predisposes them to poor outcomes if they acquire COVID-19, there is less recognition of the nonmedical health-related social needs and social determinants of health that represent the root causes of such health disparities,” they wrote.

Social determinants of health include an array of population factors, including economic stability, social and community context, neighborhood and environment, education, and access to health care.

For each, Dr. Gray encouraged comprehensive and nuanced assessment.

“Is there access to health care?” Dr. Gray asked. “Not just access in the sense of having insurance – certainly that’s a benefit – but if someone has insurance, can they get to where the health center is? Or is that something they might have to catch three buses and a cab to get to?”

Dr. Gray said that such obstacles are not outside the scope of the medical community.

“This is not beyond our responsibility ... to address social determinants of health,” Dr. Gray said.

When asked by a webinar attendee how the medical community can tackle racism, Dr. Gray offered several practical steps to move forward.

First, he suggested that clinicians and researchers listen to affected patient populations.

“Many of us, including clinicians, have been privileged to have their blinders on, if you will, to issues of racism that have been affecting our patients for a long time,” he said.

Second, Dr. Gray encouraged those who have learned to teach others.

“You need to start teaching your peers, your colleagues, your family, and friends about how racism affects patient outcomes.”

Third, he recommended that clinicians incorporate these lessons into routine practice, whether in a private or an academic setting.

“Are there ways in which you can refer patients to address social determinants of health? Are you capturing that information in your check-in materials?” Dr. Gray asked. “If you’re an investigator, when you’re doing research – whether it’s health disparities research or other – are you looking at your research through a health equity lens? Are you asking questions about social determinants of health?”

Finally, Dr. Gray called for stronger community engagement during design and conduction of clinical trials.

“People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care,” he said. “And they won’t know how much you care unless you’re visible, and unless you’re there, and these are sustainable relationships.”

The FORWARD program is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

FROM THE AGA FORWARD PROGRAM

Molecular developments in treatment of UPSC

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is an infrequent but deadly form of endometrial cancer comprising 10% of cases but contributing 40% of deaths from the disease. Recurrence rates are high for this disease. Five-year survival is 55% for all patients and only 70% for stage I disease.1 Patterns of recurrence tend to be distant (extrapelvic and extraabdominal) as frequently as they are localized to the pelvis, and metastases and recurrences are unrelated to the extent of uterine disease (such as myometrial invasion). It is for these reasons that the recommended course of adjuvant therapy for this disease is systemic therapy (typically six doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy) with consideration for radiation to the vagina or pelvis to consolidate pelvic and vaginal control.2 This differs from early-stage high/intermediate–risk endometrioid adenocarcinomas, for which adjuvant chemotherapy has not been found to be helpful.

Because of the lower incidence of UPSC, it frequently has been studied alongside endometrioid cell types in clinical trials which explore novel adjuvant therapies. However, UPSC is biologically distinct from endometrioid endometrial cancers, which likely results in inferior clinical responses to conventional interventions. Fortunately we are beginning to better understand UPSC at a molecular level, and advancements are being made in the targeted therapies for these patients that are unique, compared with those applied to other cancer subtypes.

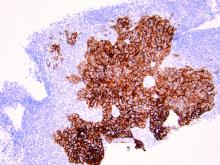

As discussed above, UPSC is a particularly aggressive form of uterine cancer. Histologically it is characterized by a precursor lesion of endometrial glandular dysplasia progressing to endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIC). Histologically it presents with a highly atypical slit-like glandular configuration, which appears similar to serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube and ovary. Molecularly these tumors commonly manifest mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), which are both genes associated with oncogenic potential.1 While most UPSC tumors have loss of expression in hormone receptors such as estrogen and progesterone, 25%-30% of cases overexpress the tyrosine kinase receptor human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).3-5 This has proven to provide an exciting target for therapeutic interventions.

A target for therapeutic intervention

HER2 is a transmembrane receptor which, when activated, signals complex downstream pathways responsible for cellular proliferation, dedifferentiation, and metastasis. In a recent multi-institutional analysis of early-stage UPSC, HER2 overexpression was identified among 25% of cases.4 Approximately 30% of cases of advanced disease manifest overexpression of this biomarker.5 HER2 overexpression (HER2-positive status) is significantly associated with higher rates of recurrence and mortality, even among patients treated with conventional therapies.3 Thus HER2-positive status is obviously an indicator of particularly aggressive disease.

Fortunately this particular biomarker is one for which we have established and developing therapeutics. The humanized monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, has been highly effective in improving survival for HER2-positive breast cancer.6 More recently, it was studied in a phase 2 trial with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent HER2-positive UPSC.5 This trial showed that the addition of this targeted therapy to conventional chemotherapy improved recurrence-free survival from 8 months to 12 months, and improved overall survival from 24.4 months to 29.6 months.5

One discovery leads to another treatment

This discovery led to the approval of trastuzumab to be used in addition to chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent disease.2 The most significant effects appear to be among those who have not received prior therapies, with a doubling of progression-free survival among these patients, and a more modest response among patients treated for recurrent, mostly pretreated disease.

Work currently is underway to explore an array of antibody or small-molecule blockades of HER2 in addition to vaccines against the protein or treatment with conjugate compounds in which an antibody to HER2 is paired with a cytotoxic drug able to be internalized into HER2-expressing cells.7 This represents a form of personalized medicine referred to as biomarker-driven targeted therapy, in which therapies are prescribed based on the expression of specific molecular markers (such as HER2 expression) typically in combination with other clinical markers such as surgical staging results, race, age, etc. These approaches can be very effective strategies in rare tumor subtypes with distinct molecular and clinical behaviors.

As previously mentioned, the targeting of HER2 overexpression with trastuzumab has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancers where even patients with early-stage disease receive a multimodal therapy approach including antibody, chemotherapy, surgical, and often radiation treatments.6 We are moving towards a similar multimodal comprehensive treatment strategy for UPSC. If it is as successful as it is in breast cancer, it will be long overdue, and desperately necessary given the poor prognosis of this disease for all stages because of the inadequacies of current treatments strategies.

Routine testing of UPSC for HER2 expression is now a part of routine molecular substaging of uterine cancers in the same way we have embraced testing for microsatellite instability and hormone-receptor status. While a diagnosis of HER2 overexpression in UPSC portends a poor prognosis, patients can be reassured that treatment strategies exist that can target this malignant mechanism in advanced disease and more are under further development for early-stage disease.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328334d8a3.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Uterine Neoplasms (version 2.2020).

3. Cancer 2005 Oct 1. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21308.

4. Gynecol Oncol 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.07.016.

5. J Clin Oncol 2018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5966.

6. N Engl J Med 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383.

7. Discov Med. 2016 Apr;21(116):293-303.

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is an infrequent but deadly form of endometrial cancer comprising 10% of cases but contributing 40% of deaths from the disease. Recurrence rates are high for this disease. Five-year survival is 55% for all patients and only 70% for stage I disease.1 Patterns of recurrence tend to be distant (extrapelvic and extraabdominal) as frequently as they are localized to the pelvis, and metastases and recurrences are unrelated to the extent of uterine disease (such as myometrial invasion). It is for these reasons that the recommended course of adjuvant therapy for this disease is systemic therapy (typically six doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy) with consideration for radiation to the vagina or pelvis to consolidate pelvic and vaginal control.2 This differs from early-stage high/intermediate–risk endometrioid adenocarcinomas, for which adjuvant chemotherapy has not been found to be helpful.

Because of the lower incidence of UPSC, it frequently has been studied alongside endometrioid cell types in clinical trials which explore novel adjuvant therapies. However, UPSC is biologically distinct from endometrioid endometrial cancers, which likely results in inferior clinical responses to conventional interventions. Fortunately we are beginning to better understand UPSC at a molecular level, and advancements are being made in the targeted therapies for these patients that are unique, compared with those applied to other cancer subtypes.

As discussed above, UPSC is a particularly aggressive form of uterine cancer. Histologically it is characterized by a precursor lesion of endometrial glandular dysplasia progressing to endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIC). Histologically it presents with a highly atypical slit-like glandular configuration, which appears similar to serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube and ovary. Molecularly these tumors commonly manifest mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), which are both genes associated with oncogenic potential.1 While most UPSC tumors have loss of expression in hormone receptors such as estrogen and progesterone, 25%-30% of cases overexpress the tyrosine kinase receptor human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).3-5 This has proven to provide an exciting target for therapeutic interventions.

A target for therapeutic intervention

HER2 is a transmembrane receptor which, when activated, signals complex downstream pathways responsible for cellular proliferation, dedifferentiation, and metastasis. In a recent multi-institutional analysis of early-stage UPSC, HER2 overexpression was identified among 25% of cases.4 Approximately 30% of cases of advanced disease manifest overexpression of this biomarker.5 HER2 overexpression (HER2-positive status) is significantly associated with higher rates of recurrence and mortality, even among patients treated with conventional therapies.3 Thus HER2-positive status is obviously an indicator of particularly aggressive disease.

Fortunately this particular biomarker is one for which we have established and developing therapeutics. The humanized monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, has been highly effective in improving survival for HER2-positive breast cancer.6 More recently, it was studied in a phase 2 trial with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent HER2-positive UPSC.5 This trial showed that the addition of this targeted therapy to conventional chemotherapy improved recurrence-free survival from 8 months to 12 months, and improved overall survival from 24.4 months to 29.6 months.5

One discovery leads to another treatment

This discovery led to the approval of trastuzumab to be used in addition to chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent disease.2 The most significant effects appear to be among those who have not received prior therapies, with a doubling of progression-free survival among these patients, and a more modest response among patients treated for recurrent, mostly pretreated disease.

Work currently is underway to explore an array of antibody or small-molecule blockades of HER2 in addition to vaccines against the protein or treatment with conjugate compounds in which an antibody to HER2 is paired with a cytotoxic drug able to be internalized into HER2-expressing cells.7 This represents a form of personalized medicine referred to as biomarker-driven targeted therapy, in which therapies are prescribed based on the expression of specific molecular markers (such as HER2 expression) typically in combination with other clinical markers such as surgical staging results, race, age, etc. These approaches can be very effective strategies in rare tumor subtypes with distinct molecular and clinical behaviors.

As previously mentioned, the targeting of HER2 overexpression with trastuzumab has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancers where even patients with early-stage disease receive a multimodal therapy approach including antibody, chemotherapy, surgical, and often radiation treatments.6 We are moving towards a similar multimodal comprehensive treatment strategy for UPSC. If it is as successful as it is in breast cancer, it will be long overdue, and desperately necessary given the poor prognosis of this disease for all stages because of the inadequacies of current treatments strategies.

Routine testing of UPSC for HER2 expression is now a part of routine molecular substaging of uterine cancers in the same way we have embraced testing for microsatellite instability and hormone-receptor status. While a diagnosis of HER2 overexpression in UPSC portends a poor prognosis, patients can be reassured that treatment strategies exist that can target this malignant mechanism in advanced disease and more are under further development for early-stage disease.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328334d8a3.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Uterine Neoplasms (version 2.2020).

3. Cancer 2005 Oct 1. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21308.

4. Gynecol Oncol 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.07.016.

5. J Clin Oncol 2018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5966.

6. N Engl J Med 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383.

7. Discov Med. 2016 Apr;21(116):293-303.

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is an infrequent but deadly form of endometrial cancer comprising 10% of cases but contributing 40% of deaths from the disease. Recurrence rates are high for this disease. Five-year survival is 55% for all patients and only 70% for stage I disease.1 Patterns of recurrence tend to be distant (extrapelvic and extraabdominal) as frequently as they are localized to the pelvis, and metastases and recurrences are unrelated to the extent of uterine disease (such as myometrial invasion). It is for these reasons that the recommended course of adjuvant therapy for this disease is systemic therapy (typically six doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy) with consideration for radiation to the vagina or pelvis to consolidate pelvic and vaginal control.2 This differs from early-stage high/intermediate–risk endometrioid adenocarcinomas, for which adjuvant chemotherapy has not been found to be helpful.

Because of the lower incidence of UPSC, it frequently has been studied alongside endometrioid cell types in clinical trials which explore novel adjuvant therapies. However, UPSC is biologically distinct from endometrioid endometrial cancers, which likely results in inferior clinical responses to conventional interventions. Fortunately we are beginning to better understand UPSC at a molecular level, and advancements are being made in the targeted therapies for these patients that are unique, compared with those applied to other cancer subtypes.

As discussed above, UPSC is a particularly aggressive form of uterine cancer. Histologically it is characterized by a precursor lesion of endometrial glandular dysplasia progressing to endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIC). Histologically it presents with a highly atypical slit-like glandular configuration, which appears similar to serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube and ovary. Molecularly these tumors commonly manifest mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), which are both genes associated with oncogenic potential.1 While most UPSC tumors have loss of expression in hormone receptors such as estrogen and progesterone, 25%-30% of cases overexpress the tyrosine kinase receptor human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).3-5 This has proven to provide an exciting target for therapeutic interventions.

A target for therapeutic intervention

HER2 is a transmembrane receptor which, when activated, signals complex downstream pathways responsible for cellular proliferation, dedifferentiation, and metastasis. In a recent multi-institutional analysis of early-stage UPSC, HER2 overexpression was identified among 25% of cases.4 Approximately 30% of cases of advanced disease manifest overexpression of this biomarker.5 HER2 overexpression (HER2-positive status) is significantly associated with higher rates of recurrence and mortality, even among patients treated with conventional therapies.3 Thus HER2-positive status is obviously an indicator of particularly aggressive disease.

Fortunately this particular biomarker is one for which we have established and developing therapeutics. The humanized monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, has been highly effective in improving survival for HER2-positive breast cancer.6 More recently, it was studied in a phase 2 trial with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent HER2-positive UPSC.5 This trial showed that the addition of this targeted therapy to conventional chemotherapy improved recurrence-free survival from 8 months to 12 months, and improved overall survival from 24.4 months to 29.6 months.5

One discovery leads to another treatment

This discovery led to the approval of trastuzumab to be used in addition to chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent disease.2 The most significant effects appear to be among those who have not received prior therapies, with a doubling of progression-free survival among these patients, and a more modest response among patients treated for recurrent, mostly pretreated disease.

Work currently is underway to explore an array of antibody or small-molecule blockades of HER2 in addition to vaccines against the protein or treatment with conjugate compounds in which an antibody to HER2 is paired with a cytotoxic drug able to be internalized into HER2-expressing cells.7 This represents a form of personalized medicine referred to as biomarker-driven targeted therapy, in which therapies are prescribed based on the expression of specific molecular markers (such as HER2 expression) typically in combination with other clinical markers such as surgical staging results, race, age, etc. These approaches can be very effective strategies in rare tumor subtypes with distinct molecular and clinical behaviors.

As previously mentioned, the targeting of HER2 overexpression with trastuzumab has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancers where even patients with early-stage disease receive a multimodal therapy approach including antibody, chemotherapy, surgical, and often radiation treatments.6 We are moving towards a similar multimodal comprehensive treatment strategy for UPSC. If it is as successful as it is in breast cancer, it will be long overdue, and desperately necessary given the poor prognosis of this disease for all stages because of the inadequacies of current treatments strategies.

Routine testing of UPSC for HER2 expression is now a part of routine molecular substaging of uterine cancers in the same way we have embraced testing for microsatellite instability and hormone-receptor status. While a diagnosis of HER2 overexpression in UPSC portends a poor prognosis, patients can be reassured that treatment strategies exist that can target this malignant mechanism in advanced disease and more are under further development for early-stage disease.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328334d8a3.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Uterine Neoplasms (version 2.2020).

3. Cancer 2005 Oct 1. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21308.

4. Gynecol Oncol 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.07.016.

5. J Clin Oncol 2018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5966.

6. N Engl J Med 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383.

7. Discov Med. 2016 Apr;21(116):293-303.

Three malpractice risks of video visits

During a telemedicine visit with his physician, a 62-year-old obese patient with an ankle injury reported new swelling of his leg. Three weeks had passed since the man visited an emergency department, where he underwent surgery and had a cast applied to the wound. The physician, during the telemedicine visit, advised the patient to elevate his leg and see an orthopedist within 24 hours. A Doppler ultrasound was ordered for 12:30 p.m. that same day.

The patient never made it to the appointment. He became unresponsive and went into full arrest hours later. His death fueled a lawsuit by his family that claimed failure to diagnose and treat deep venous thrombosis. The family contended the providers involved should have referred the patient to care immediately during the video visit.

The case, which comes from the claims database of national medical liability insurer The Doctors Company, illustrates the legal risks that can stem from video visits with patients, says Richard Cahill, JD, vice president and associate general counsel for The Doctors Company.

“By evaluating the patient remotely, the physician failed to appreciate the often subtle nuances of the clinical presentation, which undoubtedly could have been more accurately assessed in the office setting, and would probably have led to more urgent evaluation and intervention, thereby likely preventing the unfortunate and otherwise avoidable result,” said Mr. Cahill.

According to a Harris poll, 42% of Americans reported using video visits during the pandemic, a trend that is likely to continue as practices reopen and virtual care becomes the norm. But as physicians conduct more video visits, so grows their risk for lawsuits associated with the technology.

“We probably will see more malpractice suits filed the more telehealth is used,” said Mei Wa Kwong, JD, executive director of the Center for Connected Health Policy. “It’s a numbers game. The more it’s used, the higher likelihood that lawsuits occur.”

Three problems in not being able to touch the patient

1. The primary challenge with video visits “is the inability to directly observe and lay hands on the patient,” says Jonathan Einbinder, MD, assistant vice president of analytics for CRICO, a medical liability insurer based in Boston.

said Dr. Einbinder, a practicing internist.

Such incomplete pictures can lead to diagnostic errors and the potential for lawsuits, as demonstrated by a recent CRICO analysis. Of 106 telemedicine-related claims from 2014 to 2018, 66% were diagnosis related, according to the analysis of claims from CRICO’s national database. Twelve percent of the telemedicine-related claims were associated with surgical treatment, 11% were related to medical treatment, and 5% were associated with medication issues. A smaller number of claims resulted from patient monitoring, ob.gyn. care, and safety and security.

Another analysis by The Doctors Company similarly determined that diagnostic errors are the most common allegation in telemedicine-related claims. In the study of 28 telemedicine-related claims from The Doctors’ database, 71% were diagnosis related, 11% were associated with mismanagement of treatment, and 7% were related to improper management of a surgical patient. Other allegations included improper performance of treatment or procedure and improper performance of surgery.

“Because a ‘typical’ exam can’t be done, there is the potential to miss things,” said David L. Feldman, MD, chief medical officer for The Doctors Company Group. “A subtlety, perhaps a lump that can’t be seen but only felt, and only by an experienced examiner, for example, may be missed.”

2. Documentation dangers also loom, said William Sullivan, DO, JD, an emergency physician and an attorney who specializes in health care. The legal risk lies in documenting a video visit in the same way the doctor would document an in-person visit, he explained.

“Investigation into a potential lawsuit begins when there is some type of bad outcome related to medical care,” Dr. Sullivan explained. “To determine whether the lawsuit has merit, patients/attorneys review the medical records to retrospectively determine the potential cause of the bad outcome. If the documentation reflects an examination that could not have been performed, a lawyer might be more likely to pursue a case, and it would be more difficult to defend the care provided.”

Dr. Sullivan provided this example: During a video visit, a patient complains of acute onset weakness. The physician documents that the patient’s heart has a “regular rate and rhythm,” and “muscle strength is equal bilaterally.” The following day, the patient’s weakness continues, and the patient goes to the emergency department where he is diagnosed with stroke. An EKG in the ED shows that the patient is in atrial fibrillation.

“The telehealth provider would have a difficult time explaining how it was determined that the patient had normal muscle strength and a normal heart rhythm over a video visit the day before,” Dr. Sullivan said. “A lawyer in a subsequent malpractice case would present the provider as careless and would argue that if the provider had only sent the patient to the emergency department after the telehealth visit instead of documenting exam findings that couldn’t have been performed, the patient could have been successfully treated for the stroke.”

3. Poorly executed informed consent can also give rise to a lawsuit. This includes informed consent regarding the use of telehealth as the accepted modality for the visit rather than traditional on-site evaluations, as well as preprocedure informed consent.

“Inadequate and/or poorly documented informed consent can result in a claim for medical battery,” Mr. Cahill said.

A medical battery allegation refers to the alleged treatment or touching of a patient’s body without that person’s consent. As the AMA Journal of Ethics explains, a patient’s consent must be given, either expressly or implicitly, before a physician may legally “interfere” with the physical body of the patient.

Ideally, the informed consent process is undertaken during a first in-person visit, before virtual visits begin, Dr. Feldman said.

“There is a lot that a patient has to understand when a visit is done virtually, which is part of the informed consent process,” Dr. Feldman said. “The pandemic has forced some physicians to do their first visit virtually, and this makes the process of informing patients more onerous. It is not a simple matter of converting an in-person office practice to a remote office practice. The work flows are different, so there are definitely legal concerns as it relates to privacy and cybersecurity to name a few.”

Waivers may be weak protection

Since the pandemic started, a number of states have enacted emergency malpractice protections to shield health professionals from lawsuits. Some protections, such as those in Massachusetts, offer immunity to health professionals who provide general care to patients during the COVID-19 emergency, in addition to treatment of COVID-19 patients. Other protections, like those in Connecticut, apply specifically to care provided in support of the state’s pandemic response.

Whether that immunity applies both to in-person visits and video visits during the pandemic is not certain, said J. Richard Moore, JD, a medical liability defense attorney based in Indianapolis. Indiana’s immunity statute for example, does not make a specific provision for telehealth, he said.

“My best prediction is that if considered by the courts, the immunity would be applied to telehealth services, so long as they are being provided ‘in response to the emergency,’ which is the scope of the immunity,” he said. “I would not consider telehealth physicians to be either more or less protected than in-person providers.”

Regulatory scrutiny for telehealth providers has also been relaxed in response to COVID-19, but experts warn not to rely on the temporary shields for ultimate protection.

In March, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) eased enforcement actions for noncompliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act requirements in connection with the good faith provision of telehealth during the COVID-19 health crisis. Under the notice, health providers can use popular applications such as Apple FaceTime, Facebook Messenger, Zoom, or Google Hangouts, to offer telehealth care without risk that OCR will impose fines or penalties for HIPAA violations.

But once the current health care emergency is mitigated, the waivers will likely be withdrawn, and enforcement actions will probably resume, Mr. Cahill said.

“It is recommended that, to avoid potential problems going forward, practitioners use due diligence and undertake best efforts to obey existing privacy and security requirements, including the use of technology that satisfies compliance regulations, despite the waiver by OCR,” he said.

In addition, a majority of states have relaxed state-specific rules for practicing telehealth and loosened licensure requirements during the pandemic. At least 47 states have issued waivers to alter in-state licensure requirements for telemedicine in response to COVID-19, according to the Federation of State Medical Boards. Most of the waivers allow physicians licensed in other states to provide care in states where they do not hold licenses, and some enable doctors to treat patients without first having had an in-person evaluation.

But at least for now, these are temporary changes, reminds Amy Lerman, JD, a health care attorney based in Washington, who specializes in telehealth and corporate compliance. Given the current pandemic environment, a significant concern is that physicians new to the telemedicine space are reacting only to the most recent rules established in the context of the pandemic, Ms. Lerman said.

“As previously noted, the recent developments are temporary in nature – states and various federal agencies have been pretty clear in setting this temporal boundary,” she said. “It is not advisable for providers to build telepractice models around temporary sets of rules.

“Furthermore, the recent developments are not necessarily comprehensive relative to all of the state-specific and other requirements that telemedicine providers are otherwise expected to follow, so relying only on the most recent guidance may cause providers to create telepractice models that have key gaps with respect to regulatory compliance.”

How you can avoid a lawsuit

As businesses reopen and practices resume treatments, physicians should weigh the choice between in-person care and video visits very carefully, said Joseph Kvedar, MD, president of the American Telemedicine Association and a dermatology professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We have to be very thoughtful about quality in this current phase, where we are doing what I call a hybrid model,” he said. “Some services are offered by telehealth and some require patients to come into the doctor’s office. We have to be very thoughtful about what types of care we determine to be appropriate for telehealth, and that has to be based on clinical quality. And if it is, it should follow that we’ll have low incidence of liability claims.”

Data should be at the center of that conclusion, Dr. Kvedar advises.

“Think about what data is needed to make a therapeutic or diagnostic decision,” he said. “If a health care provider can gather the information needed without touching the patient, then the provider is probably on safe, solid ground making that decision via a telehealth interaction. If the patient can come into the doctor’s office, and the provider deems it necessary to see the patient in person and touch the patient in order to make that clinical decision, then the patient should come in.”

An important step to preventing liability is also having strong telehealth systems and protocols in place and the necessary support to carry them out, said Dr. Einbinder of medical liability insurer CRICO.

For example, Dr. Einbinder, who practices in a 12-doctor internal medicine group, said when he finishes a virtual visit, he enters any orders into the electronic health record. Some of the orders will result in notifications to Dr. Einbinder if they are not executed, such as a referral appointment or a procedure that was not completed.

“I also can forward my orders to a front desk pool that is responsible for making sure things get done,” he said. “And, in our hospital system, we have good case management for complex patients and population management for a variety of chronic conditions. These represent additional safety nets.”

Another liability safeguard is sending patients a “visit summary” after each virtual visit, Dr. Sullivan said. This could be in the form of an email or a text that includes a brief template including items such as diagnosis, recommendations, follow-up, and a reminder to contact the doctor or go to the emergency department if symptoms worsen or new problems develop.

“Patients tend to remember about half of what physicians tell them and half of the information patients do remember is incorrect,” he said. “Consider a few sentences in an e-mail or text message as a substitute for the after-visit instructions from an office visit to enhance patient understanding. There are several inexpensive programs/services that allow text messages to be sent from a computer using a separate dedicated phone number and pretty much every patient has a cell phone to receive the instructions.”

Dr. Sullivan suggests having a documentation template specifically for telehealth visits. He also recommends the inclusion an “informed refusal of care” in the record when necessary. Dr. Sullivan’s wife, a family physician, has encountered several patients who fear contracting COVID-19 and who have refused her recommendations for in-person visits, he said. In such cases, he said it’s a good idea to document that the patient decided to forgo the recommendations given.

“If a patient suffers a bad outcome because of a failure to seek an in-person exam, a short note in the patient’s chart would help to establish that the lack of a follow-up physical exam was the patient’s informed decision, not due to some alleged negligence of the medical provider,” he said.

Concerning informed consent, Dr. Feldman says at a minimum physicians should discuss the following with patients:

- Names and credentials of staff participating.

- The right to stop or refuse treatment by telemedicine.

- Technology that will be used.

- Privacy and security risks.

- Technology-specific risks and permission to bill.

- Alternative care in case of an emergency or technology malfunction.

- Any state-specific requirements.

“Physicians can ensure they have a strong informed consent process during video visits by taking the time to cover these points at the beginning of the first visit, and being sure the patient understands and agrees to these,” Dr. Sullivan explained. “Ideally, this conversation can be recorded for future reference if necessary or at a minimum documented in the medical record.”

Consider these extra precautions

Mr. Cahill advises that practitioners be especially mindful of their “web-side manner” and the setting in which they are communicating with virtual patients to promote confidentiality, professionalism, and uninterrupted interactions.

“Use of a headset in a quiet home office is advisable,” he said. “Physicians must also be cognizant of their physical appearance and the background behind them when the visit includes both audio and visual capability. For ‘face-to-face’ telehealth encounters, it is recommended that a white lab jacket be worn as the appropriate attire; coat and tie are unnecessary.”

Some patients may need to be reminded of the need for confidentiality during a video visit, Mr. Moore added. Physicians are typically in a position to ensure confidentiality, but some patients may not understand how to protect their privacy on their end.