User login

High ‘forever chemicals’ in blood linked to earlier menopause

In a national sample of U.S. women in their mid-40s to mid-50s, those with high serum levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were likely to enter menopause 2 years earlier than those with low levels of these chemicals.

That is, the median age of natural menopause was 52.8 years versus 50.8 years in women with high versus low serum levels of these chemicals in an analysis of data from more than 1,100 women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Multi-Pollutant Study, which excluded women with premature menopause (before age 40) or early menopause (before age 45).

“This study suggests that select PFAS serum concentrations are associated with earlier natural menopause, a risk factor for adverse health outcomes in later life,” Ning Ding, PhD, MPH, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues concluded in their article, published online June 3 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Even menopause a few years earlier than usual could have a significant impact on cardiovascular and bone health, quality of life, and overall health in general among women,” senior author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, from the same institution, added in a statement.

PFAS don’t break down in the body, build up with time

PFAS have been widely used in many consumer and industrial products such as nonstick cookware, stain-repellent carpets, waterproof rain gear, microwave popcorn bags, and firefighting foam, the authors explained.

These have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they do not degrade. Household water for an estimated 110 million Americans (one in three) may be contaminated with these chemicals, according to an Endocrine Society press release.

“PFAS are everywhere. Once they enter the body, they don’t break down and [they] build up over time,” said Dr. Ding. “Because of their persistence in humans and potentially detrimental effects on ovarian function, it is important to raise awareness of this issue and reduce exposure to these chemicals.”

Environmental exposure and accelerated ovarian aging

Earlier menopause has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and earlier cardiovascular and overall mortality, and environmental exposure may accelerate ovarian aging, the authors wrote.

PFAS, especially the most studied types – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) – are plausible endocrine-disrupting chemicals, but findings so far have been inconsistent.

A study of people in Ohio exposed to contaminated water found that women with earlier natural menopause had higher serum PFOA and PFOS levels (J Clin Endocriniol Metab. 2011;96:1747-53).

But in research based on National Health and Nutrition Survey Examination data, higher PFOA, PFOS, or perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) levels were not linked to earlier menopause, although higher levels of perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) were (Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:145-50).

There may have been reverse causation, where postmenopausal women had higher PFAS levels because they were not excreting these chemicals in menstrual blood.

In a third study, PFOA exposure was not linked with age at menopause onset, but this was based on recall from 10 years earlier (Environ Res. 2016;146:323-30).

The current analysis examined data from 1,120 premenopausal women who were aged 45-56 years from 1999 to 2000.

The women were seen at five sites (Boston; Detroit; Los Angeles; Oakland, Calif.; and Pittsburgh) and were ethnically diverse (577 white, 235 black, 142 Chinese, and 166 Japanese).

Baseline serum PFAS levels were measured using high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The women were followed up to 2017 and incident menopause (12 consecutive months with no menstruation) was determined from annual interviews.

Of the 1,120 women and 5,466 person-years of follow-up, 578 women had a known date of natural incident menopause and were included in the analysis. The remaining 542 women were excluded mainly because their date of final menstruation was unknown because of hormone therapy (451) or they had a hysterectomy, or did not enter menopause during the study.

Compared with women in the lowest tertile of PFOS levels, women in the highest tertile had a significant 26%-27% greater risk of incident menopause – after adjusting for age, body mass index, and prior hormone use, race/ethnicity, study site, education, physical activity, smoking status, and parity.

Higher PFOA and PFNA levels but not higher PFHxS levels were also associated with increased risk.

Compared with women with a low overall PFAS level, those with a high level had a 63% increased risk of incident menopause (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.45), equivalent to having menopause a median of 2 years earlier.

Although production and use of some types of PFAS in the United States are declining, Dr. Ding and colleagues wrote, exposure continues, along with associated potential hazards to human reproductive health.

“Due to PFAS widespread use and environmental persistence, their potential adverse effects remain a public health concern,” they concluded.

SWAN was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health & Human Services through the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the SWAN repository. The current article was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a national sample of U.S. women in their mid-40s to mid-50s, those with high serum levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were likely to enter menopause 2 years earlier than those with low levels of these chemicals.

That is, the median age of natural menopause was 52.8 years versus 50.8 years in women with high versus low serum levels of these chemicals in an analysis of data from more than 1,100 women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Multi-Pollutant Study, which excluded women with premature menopause (before age 40) or early menopause (before age 45).

“This study suggests that select PFAS serum concentrations are associated with earlier natural menopause, a risk factor for adverse health outcomes in later life,” Ning Ding, PhD, MPH, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues concluded in their article, published online June 3 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Even menopause a few years earlier than usual could have a significant impact on cardiovascular and bone health, quality of life, and overall health in general among women,” senior author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, from the same institution, added in a statement.

PFAS don’t break down in the body, build up with time

PFAS have been widely used in many consumer and industrial products such as nonstick cookware, stain-repellent carpets, waterproof rain gear, microwave popcorn bags, and firefighting foam, the authors explained.

These have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they do not degrade. Household water for an estimated 110 million Americans (one in three) may be contaminated with these chemicals, according to an Endocrine Society press release.

“PFAS are everywhere. Once they enter the body, they don’t break down and [they] build up over time,” said Dr. Ding. “Because of their persistence in humans and potentially detrimental effects on ovarian function, it is important to raise awareness of this issue and reduce exposure to these chemicals.”

Environmental exposure and accelerated ovarian aging

Earlier menopause has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and earlier cardiovascular and overall mortality, and environmental exposure may accelerate ovarian aging, the authors wrote.

PFAS, especially the most studied types – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) – are plausible endocrine-disrupting chemicals, but findings so far have been inconsistent.

A study of people in Ohio exposed to contaminated water found that women with earlier natural menopause had higher serum PFOA and PFOS levels (J Clin Endocriniol Metab. 2011;96:1747-53).

But in research based on National Health and Nutrition Survey Examination data, higher PFOA, PFOS, or perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) levels were not linked to earlier menopause, although higher levels of perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) were (Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:145-50).

There may have been reverse causation, where postmenopausal women had higher PFAS levels because they were not excreting these chemicals in menstrual blood.

In a third study, PFOA exposure was not linked with age at menopause onset, but this was based on recall from 10 years earlier (Environ Res. 2016;146:323-30).

The current analysis examined data from 1,120 premenopausal women who were aged 45-56 years from 1999 to 2000.

The women were seen at five sites (Boston; Detroit; Los Angeles; Oakland, Calif.; and Pittsburgh) and were ethnically diverse (577 white, 235 black, 142 Chinese, and 166 Japanese).

Baseline serum PFAS levels were measured using high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The women were followed up to 2017 and incident menopause (12 consecutive months with no menstruation) was determined from annual interviews.

Of the 1,120 women and 5,466 person-years of follow-up, 578 women had a known date of natural incident menopause and were included in the analysis. The remaining 542 women were excluded mainly because their date of final menstruation was unknown because of hormone therapy (451) or they had a hysterectomy, or did not enter menopause during the study.

Compared with women in the lowest tertile of PFOS levels, women in the highest tertile had a significant 26%-27% greater risk of incident menopause – after adjusting for age, body mass index, and prior hormone use, race/ethnicity, study site, education, physical activity, smoking status, and parity.

Higher PFOA and PFNA levels but not higher PFHxS levels were also associated with increased risk.

Compared with women with a low overall PFAS level, those with a high level had a 63% increased risk of incident menopause (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.45), equivalent to having menopause a median of 2 years earlier.

Although production and use of some types of PFAS in the United States are declining, Dr. Ding and colleagues wrote, exposure continues, along with associated potential hazards to human reproductive health.

“Due to PFAS widespread use and environmental persistence, their potential adverse effects remain a public health concern,” they concluded.

SWAN was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health & Human Services through the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the SWAN repository. The current article was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a national sample of U.S. women in their mid-40s to mid-50s, those with high serum levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were likely to enter menopause 2 years earlier than those with low levels of these chemicals.

That is, the median age of natural menopause was 52.8 years versus 50.8 years in women with high versus low serum levels of these chemicals in an analysis of data from more than 1,100 women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Multi-Pollutant Study, which excluded women with premature menopause (before age 40) or early menopause (before age 45).

“This study suggests that select PFAS serum concentrations are associated with earlier natural menopause, a risk factor for adverse health outcomes in later life,” Ning Ding, PhD, MPH, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues concluded in their article, published online June 3 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Even menopause a few years earlier than usual could have a significant impact on cardiovascular and bone health, quality of life, and overall health in general among women,” senior author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, from the same institution, added in a statement.

PFAS don’t break down in the body, build up with time

PFAS have been widely used in many consumer and industrial products such as nonstick cookware, stain-repellent carpets, waterproof rain gear, microwave popcorn bags, and firefighting foam, the authors explained.

These have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they do not degrade. Household water for an estimated 110 million Americans (one in three) may be contaminated with these chemicals, according to an Endocrine Society press release.

“PFAS are everywhere. Once they enter the body, they don’t break down and [they] build up over time,” said Dr. Ding. “Because of their persistence in humans and potentially detrimental effects on ovarian function, it is important to raise awareness of this issue and reduce exposure to these chemicals.”

Environmental exposure and accelerated ovarian aging

Earlier menopause has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and earlier cardiovascular and overall mortality, and environmental exposure may accelerate ovarian aging, the authors wrote.

PFAS, especially the most studied types – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) – are plausible endocrine-disrupting chemicals, but findings so far have been inconsistent.

A study of people in Ohio exposed to contaminated water found that women with earlier natural menopause had higher serum PFOA and PFOS levels (J Clin Endocriniol Metab. 2011;96:1747-53).

But in research based on National Health and Nutrition Survey Examination data, higher PFOA, PFOS, or perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) levels were not linked to earlier menopause, although higher levels of perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) were (Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:145-50).

There may have been reverse causation, where postmenopausal women had higher PFAS levels because they were not excreting these chemicals in menstrual blood.

In a third study, PFOA exposure was not linked with age at menopause onset, but this was based on recall from 10 years earlier (Environ Res. 2016;146:323-30).

The current analysis examined data from 1,120 premenopausal women who were aged 45-56 years from 1999 to 2000.

The women were seen at five sites (Boston; Detroit; Los Angeles; Oakland, Calif.; and Pittsburgh) and were ethnically diverse (577 white, 235 black, 142 Chinese, and 166 Japanese).

Baseline serum PFAS levels were measured using high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The women were followed up to 2017 and incident menopause (12 consecutive months with no menstruation) was determined from annual interviews.

Of the 1,120 women and 5,466 person-years of follow-up, 578 women had a known date of natural incident menopause and were included in the analysis. The remaining 542 women were excluded mainly because their date of final menstruation was unknown because of hormone therapy (451) or they had a hysterectomy, or did not enter menopause during the study.

Compared with women in the lowest tertile of PFOS levels, women in the highest tertile had a significant 26%-27% greater risk of incident menopause – after adjusting for age, body mass index, and prior hormone use, race/ethnicity, study site, education, physical activity, smoking status, and parity.

Higher PFOA and PFNA levels but not higher PFHxS levels were also associated with increased risk.

Compared with women with a low overall PFAS level, those with a high level had a 63% increased risk of incident menopause (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.45), equivalent to having menopause a median of 2 years earlier.

Although production and use of some types of PFAS in the United States are declining, Dr. Ding and colleagues wrote, exposure continues, along with associated potential hazards to human reproductive health.

“Due to PFAS widespread use and environmental persistence, their potential adverse effects remain a public health concern,” they concluded.

SWAN was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health & Human Services through the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the SWAN repository. The current article was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Erectile dysfunction: How to help patients & partners

THE CASE

Eric M,* a 36-year-old new patient, visits a primary care clinic for a check-up accompanied by his wife. A thorough history and physical exam reveal no concerns. He is active and a nonsmoker, drinks only socially, takes no medications, and reports no concerning symptoms. At the end of the visit, though, he says he has been experiencing erectile dysfunction for the past 6 months. What began as intermittent difficulty maintaining erections now “happens a lot.” He is distressed and says, “It just came out of the blue.” The patient’s wife then says she believes men cannot achieve erections if they are having an affair. When the chagrined patient simply asks for “those pills,” his wife says in a raised voice, “He’s a liar!”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Some family physicians may feel ill-equipped to talk about sexual and relational problems and lack the skills to effectively counsel on these matters.1 Despite the fact that more than 70% of adult patients want to discuss sexual topics with their family physician, sexual problems are documented in as few as 2% of patient notes.2 One of the most commonly noted sexual health concerns is erectile dysfunction (ED), estimated to occur in 35% of men ages 40 to 70.3 Many ED cases have psychological antecedents including stress, depression, performance anxiety, pornography addiction, and relationship concerns.4,5

Assessing ED. The inability to achieve or maintain an erection needed for satisfactory sexual activity is typically diagnosed through symptom self-report and with thorough history taking and physical examination.6 However, more objective scales can be used. In particular, the International Index of Erectile Function, a 15-question scale, is useful for both diagnosis and treatment monitoring (www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/iief.pdf).7 Common contributors to ED can be vascular (eg, hypertension), neurologic (eg, multiple sclerosis), psychological (noted earlier), or hormonal (eg, thyroid imbalances).6 In this article, we focus on the relationship context in which ED exists. A review of medical evaluation and management can be found elsewhere.8

Key relational questions

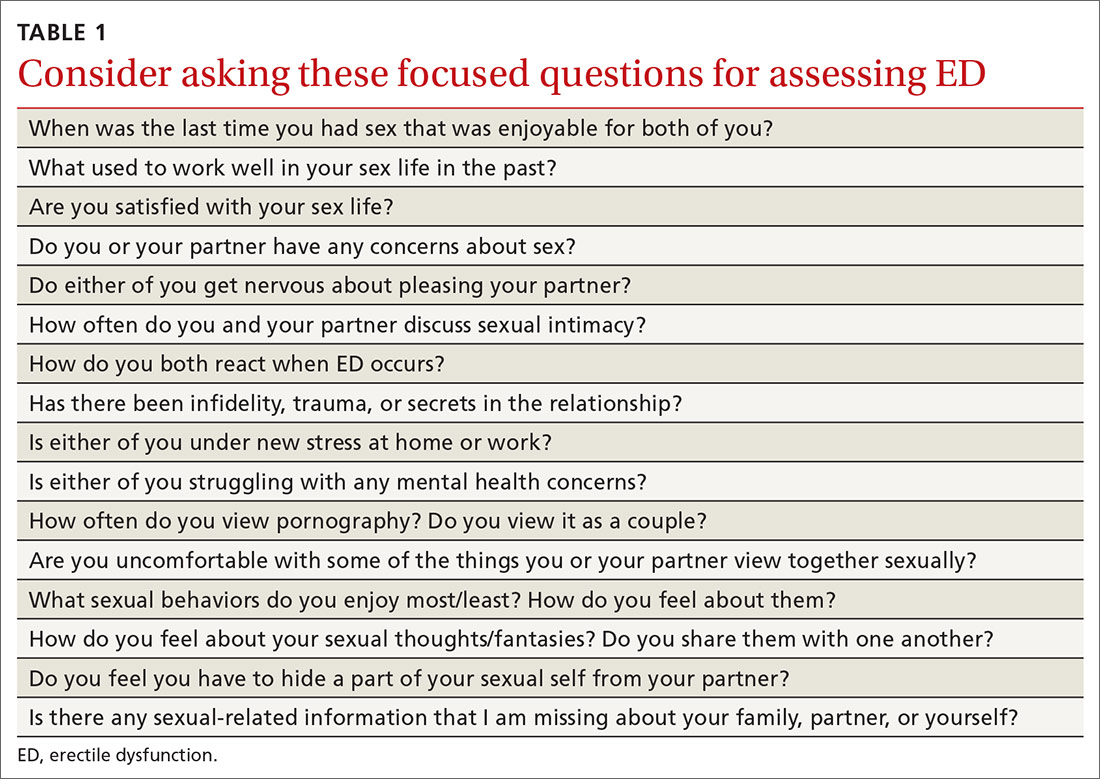

Identify norms that are specific to the couple. Patients from a variety of cultures prefer that their clinicians initiate the conversation about ED.11,12 We specifically recommend that clinicians, using relationally focused questions, inquire about sexual norms and desires that may be situated in culture, family of origin, or gender (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Treating ED within a relationship

Treating ED within a relationship

Once a couple’s sexual relationship has been fully assessed, you may confidently develop a treatment plan for managing sexual dysfunction relationally as well as medically, an approach to ED advised by the American Urological Association.13 We propose that primary care treatment for ED involve collaboration between the physician, the patient/couple (if the patient is partnered), and, as needed, a behavioral health specialist.

The physician’s role ...

Managing ED relationally is important on many fronts. If, for instance, a type-5 phosphodiesterase (PDE-5) inhibitor is needed, both the patient and partner should learn about best practices for optimizing success, such as avoiding excessive alcohol intake or high-fat meals immediately before and after taking a PDE-5.14

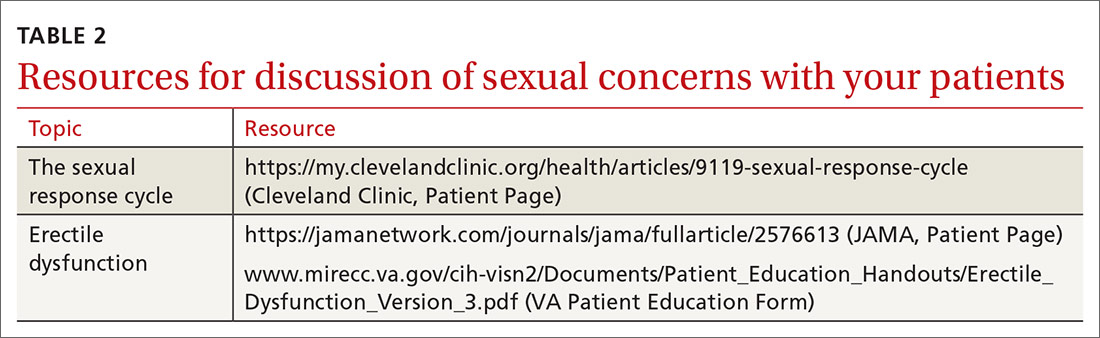

Sex ed. Regardless of the couple’s age, be prepared to offer high-quality sexual education. Either partner may have faulty knowledge (or even a lack of knowledge) of basic sexual functioning. Physicians have an opportunity to explain healthy erectile functioning, the sexual response cycle, and ways in which PDE-5 medications work (and do not work). (For a list of resources to facilitate these discussions, see TABLE 2.)

Avoid avoidance. Physicians can intervene on patterns of shame that may surround ED simply by discussing sexual functioning openly and honestly. ED often persists due to avoidance—ie, anxiety about sexual performance can lead couples to avoid sex, which perpetuates more anxiety and avoidance. Normalizing typical sexual functioning, encouraging couples to “avoid avoidance,” and providing referrals as needed are core elements of relational intervention for ED.

Setting the tone. Family physicians are not routinely trained in couples therapy. However, you can employ communication skills that allow each partner to be heard by using empathic/reflective listening, de-escalation, and reframing. Asking “What effect are the sexual concerns having on both of you?” and “What were the circumstances of the last sexual encounter that were pleasing to both of you?” can help promote intimacy and mutual satisfaction.

Continue to: The behavioral specialist's role

The behavioral specialist’s role

Behavioral health specialists may treat ED using methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy or evidence-based couple interventions.4 Cognitive methods for the treatment of ED include examination of maladaptive thoughts around pressure to perform and achieving sexual pleasure. Behavioral methods for treatment of ED are typically aimed at the de-coupling of anxiety and sexual activity. These treatments can include relaxation and desensitization, specifically sensate focus therapy.15

Sensate focus therapy involves a specific set of prescriptive rules for sexual activity, initially restricting touch to non-demand pleasurable touch (eg, holding hands) that allows couples to connect in a low-anxiety context focused on relaxation and connection. As couples are able to control anxiety while engaging in these activities, they engage in increasingly more intimate activities. Additionally, behavioral health specialists trained in couples therapy are vital to helping increase communication regarding sexual activity, sexual scripts, and the relationship in general.4

Identifying a treatment team

In coordinating couples care in the treatment of ED, enlist the help of a therapist who has specific knowledge and skills in the treatment of sexual disorders. While the number of qualified or certified sex therapists is limited, referring providers can visit the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists Web site (www.aasect.org) for possible referral sources. Another option is the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy Web site (www.aamft.org) under “Find a therapist.” Lastly, the Society for Sex Therapy and Research (www.sstarnet.org) is another professional association that provides information and local referral sources. For patients and partners located in rural areas where access is limited, telehealth options may need to be explored.

THE CASE

Mr. M and his wife were seen for a follow-up appointment by his primary care provider, who ruled out any additional causes of ED (eg, hormonal, vascular), discussed with both the patient and his wife basic sexual health and sexual functioning, dispelled several commonly held myths (ie, individuals cannot obtain an erection because of infidelity or lying), validated sexual concerns as a significant health issue, and prescribed a PDE-5 inhibitor.

Mr. M and his wife were referred to a behavioral health specialist in the clinic who had expertise in couples therapy. At several subsequent visits, the patient and his wife worked on improving the quality and quantity of communication regarding their sexual goals, mutual de-escalation of anxiety, increased emotional intimacy, and sensate focus techniques.

Continue to: As the result of the interventions...

As the result of these interventions, both the patient and his wife were able to engage in sex with less anxiety, and the patient increasingly was able to achieve more satisfactory erections without the use of the PDE-5 inhibitor. At the conclusion of therapy, the patient and his wife reported an increase in sexual satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Buck, PhD, Family Health Center, John Peter Smith Health Network, 1500 S. Main Street, Fort Worth, TX 76104; kbuck@jpshealth.org.

1. Macdowall W, Parker R, Nanchahal K, et al. ‘Talking of Sex’: developing and piloting a sexual health communication tool for use in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:332-337.

2. Sadovsky R. Asking the questions and offering solutions: the ongoing dialogue between the primary care physician and the patient with erectile dysfunction. Rev Urol. 2003;5(suppl 7):S35-S48.

3. Boston University School of Medicine. Sexual Medicine. Epidemiology of ED. 2019. www.bumc.bu.edu/sexualmedicine/physicianinformation/epidemiology-of-ed/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

4. Weeks GR, Gambescia N, Hertlein KM, eds. A Clinician’s Guide to Systemic Sex Therapy. 2nd ed. London, England: Routledge; 2016.

5. Colson MH, Cuzin A, Faix A, et al. Current epidemiology of erectile dysfunction, an update. Sexologies. 2018;27:e7-e13.

6. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94820-94827.

7. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319-326.

8. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:820-827.

9. Dean J, Rubio-Aurioles E, McCabe M, et al. Integrating partners into erectile dysfunction treatment: improving the sexual experience for the couple. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:127-133.

10. Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. Lancet. 2013; 381:153-165.

11. Lo WH, Fu SN, Wong SN, et al. Prevalence, correlates, attitude and treatment seeking of erectile dysfunction among type 2 diabetic Chinese men attending primary care outpatient clinics. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:755-760.

12. Zweifler J, Padilla A, Schafer S. Barriers to recognition of erectile dysfunction among diabetic Mexican-American men. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:259-263.

13. American Urological Society. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline (2018). www.auanet.org/guidelines/erectile-dysfunction-(ed)-guideline. Accessed May 27, 2020.

14. Huang S, Lie J. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the management of erectile dysfunction. P T. 2013;38;414-419.

15. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little Brown; 1970.

THE CASE

Eric M,* a 36-year-old new patient, visits a primary care clinic for a check-up accompanied by his wife. A thorough history and physical exam reveal no concerns. He is active and a nonsmoker, drinks only socially, takes no medications, and reports no concerning symptoms. At the end of the visit, though, he says he has been experiencing erectile dysfunction for the past 6 months. What began as intermittent difficulty maintaining erections now “happens a lot.” He is distressed and says, “It just came out of the blue.” The patient’s wife then says she believes men cannot achieve erections if they are having an affair. When the chagrined patient simply asks for “those pills,” his wife says in a raised voice, “He’s a liar!”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Some family physicians may feel ill-equipped to talk about sexual and relational problems and lack the skills to effectively counsel on these matters.1 Despite the fact that more than 70% of adult patients want to discuss sexual topics with their family physician, sexual problems are documented in as few as 2% of patient notes.2 One of the most commonly noted sexual health concerns is erectile dysfunction (ED), estimated to occur in 35% of men ages 40 to 70.3 Many ED cases have psychological antecedents including stress, depression, performance anxiety, pornography addiction, and relationship concerns.4,5

Assessing ED. The inability to achieve or maintain an erection needed for satisfactory sexual activity is typically diagnosed through symptom self-report and with thorough history taking and physical examination.6 However, more objective scales can be used. In particular, the International Index of Erectile Function, a 15-question scale, is useful for both diagnosis and treatment monitoring (www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/iief.pdf).7 Common contributors to ED can be vascular (eg, hypertension), neurologic (eg, multiple sclerosis), psychological (noted earlier), or hormonal (eg, thyroid imbalances).6 In this article, we focus on the relationship context in which ED exists. A review of medical evaluation and management can be found elsewhere.8

Key relational questions

Identify norms that are specific to the couple. Patients from a variety of cultures prefer that their clinicians initiate the conversation about ED.11,12 We specifically recommend that clinicians, using relationally focused questions, inquire about sexual norms and desires that may be situated in culture, family of origin, or gender (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Treating ED within a relationship

Treating ED within a relationship

Once a couple’s sexual relationship has been fully assessed, you may confidently develop a treatment plan for managing sexual dysfunction relationally as well as medically, an approach to ED advised by the American Urological Association.13 We propose that primary care treatment for ED involve collaboration between the physician, the patient/couple (if the patient is partnered), and, as needed, a behavioral health specialist.

The physician’s role ...

Managing ED relationally is important on many fronts. If, for instance, a type-5 phosphodiesterase (PDE-5) inhibitor is needed, both the patient and partner should learn about best practices for optimizing success, such as avoiding excessive alcohol intake or high-fat meals immediately before and after taking a PDE-5.14

Sex ed. Regardless of the couple’s age, be prepared to offer high-quality sexual education. Either partner may have faulty knowledge (or even a lack of knowledge) of basic sexual functioning. Physicians have an opportunity to explain healthy erectile functioning, the sexual response cycle, and ways in which PDE-5 medications work (and do not work). (For a list of resources to facilitate these discussions, see TABLE 2.)

Avoid avoidance. Physicians can intervene on patterns of shame that may surround ED simply by discussing sexual functioning openly and honestly. ED often persists due to avoidance—ie, anxiety about sexual performance can lead couples to avoid sex, which perpetuates more anxiety and avoidance. Normalizing typical sexual functioning, encouraging couples to “avoid avoidance,” and providing referrals as needed are core elements of relational intervention for ED.

Setting the tone. Family physicians are not routinely trained in couples therapy. However, you can employ communication skills that allow each partner to be heard by using empathic/reflective listening, de-escalation, and reframing. Asking “What effect are the sexual concerns having on both of you?” and “What were the circumstances of the last sexual encounter that were pleasing to both of you?” can help promote intimacy and mutual satisfaction.

Continue to: The behavioral specialist's role

The behavioral specialist’s role

Behavioral health specialists may treat ED using methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy or evidence-based couple interventions.4 Cognitive methods for the treatment of ED include examination of maladaptive thoughts around pressure to perform and achieving sexual pleasure. Behavioral methods for treatment of ED are typically aimed at the de-coupling of anxiety and sexual activity. These treatments can include relaxation and desensitization, specifically sensate focus therapy.15

Sensate focus therapy involves a specific set of prescriptive rules for sexual activity, initially restricting touch to non-demand pleasurable touch (eg, holding hands) that allows couples to connect in a low-anxiety context focused on relaxation and connection. As couples are able to control anxiety while engaging in these activities, they engage in increasingly more intimate activities. Additionally, behavioral health specialists trained in couples therapy are vital to helping increase communication regarding sexual activity, sexual scripts, and the relationship in general.4

Identifying a treatment team

In coordinating couples care in the treatment of ED, enlist the help of a therapist who has specific knowledge and skills in the treatment of sexual disorders. While the number of qualified or certified sex therapists is limited, referring providers can visit the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists Web site (www.aasect.org) for possible referral sources. Another option is the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy Web site (www.aamft.org) under “Find a therapist.” Lastly, the Society for Sex Therapy and Research (www.sstarnet.org) is another professional association that provides information and local referral sources. For patients and partners located in rural areas where access is limited, telehealth options may need to be explored.

THE CASE

Mr. M and his wife were seen for a follow-up appointment by his primary care provider, who ruled out any additional causes of ED (eg, hormonal, vascular), discussed with both the patient and his wife basic sexual health and sexual functioning, dispelled several commonly held myths (ie, individuals cannot obtain an erection because of infidelity or lying), validated sexual concerns as a significant health issue, and prescribed a PDE-5 inhibitor.

Mr. M and his wife were referred to a behavioral health specialist in the clinic who had expertise in couples therapy. At several subsequent visits, the patient and his wife worked on improving the quality and quantity of communication regarding their sexual goals, mutual de-escalation of anxiety, increased emotional intimacy, and sensate focus techniques.

Continue to: As the result of the interventions...

As the result of these interventions, both the patient and his wife were able to engage in sex with less anxiety, and the patient increasingly was able to achieve more satisfactory erections without the use of the PDE-5 inhibitor. At the conclusion of therapy, the patient and his wife reported an increase in sexual satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Buck, PhD, Family Health Center, John Peter Smith Health Network, 1500 S. Main Street, Fort Worth, TX 76104; kbuck@jpshealth.org.

THE CASE

Eric M,* a 36-year-old new patient, visits a primary care clinic for a check-up accompanied by his wife. A thorough history and physical exam reveal no concerns. He is active and a nonsmoker, drinks only socially, takes no medications, and reports no concerning symptoms. At the end of the visit, though, he says he has been experiencing erectile dysfunction for the past 6 months. What began as intermittent difficulty maintaining erections now “happens a lot.” He is distressed and says, “It just came out of the blue.” The patient’s wife then says she believes men cannot achieve erections if they are having an affair. When the chagrined patient simply asks for “those pills,” his wife says in a raised voice, “He’s a liar!”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Some family physicians may feel ill-equipped to talk about sexual and relational problems and lack the skills to effectively counsel on these matters.1 Despite the fact that more than 70% of adult patients want to discuss sexual topics with their family physician, sexual problems are documented in as few as 2% of patient notes.2 One of the most commonly noted sexual health concerns is erectile dysfunction (ED), estimated to occur in 35% of men ages 40 to 70.3 Many ED cases have psychological antecedents including stress, depression, performance anxiety, pornography addiction, and relationship concerns.4,5

Assessing ED. The inability to achieve or maintain an erection needed for satisfactory sexual activity is typically diagnosed through symptom self-report and with thorough history taking and physical examination.6 However, more objective scales can be used. In particular, the International Index of Erectile Function, a 15-question scale, is useful for both diagnosis and treatment monitoring (www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/iief.pdf).7 Common contributors to ED can be vascular (eg, hypertension), neurologic (eg, multiple sclerosis), psychological (noted earlier), or hormonal (eg, thyroid imbalances).6 In this article, we focus on the relationship context in which ED exists. A review of medical evaluation and management can be found elsewhere.8

Key relational questions

Identify norms that are specific to the couple. Patients from a variety of cultures prefer that their clinicians initiate the conversation about ED.11,12 We specifically recommend that clinicians, using relationally focused questions, inquire about sexual norms and desires that may be situated in culture, family of origin, or gender (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Treating ED within a relationship

Treating ED within a relationship

Once a couple’s sexual relationship has been fully assessed, you may confidently develop a treatment plan for managing sexual dysfunction relationally as well as medically, an approach to ED advised by the American Urological Association.13 We propose that primary care treatment for ED involve collaboration between the physician, the patient/couple (if the patient is partnered), and, as needed, a behavioral health specialist.

The physician’s role ...

Managing ED relationally is important on many fronts. If, for instance, a type-5 phosphodiesterase (PDE-5) inhibitor is needed, both the patient and partner should learn about best practices for optimizing success, such as avoiding excessive alcohol intake or high-fat meals immediately before and after taking a PDE-5.14

Sex ed. Regardless of the couple’s age, be prepared to offer high-quality sexual education. Either partner may have faulty knowledge (or even a lack of knowledge) of basic sexual functioning. Physicians have an opportunity to explain healthy erectile functioning, the sexual response cycle, and ways in which PDE-5 medications work (and do not work). (For a list of resources to facilitate these discussions, see TABLE 2.)

Avoid avoidance. Physicians can intervene on patterns of shame that may surround ED simply by discussing sexual functioning openly and honestly. ED often persists due to avoidance—ie, anxiety about sexual performance can lead couples to avoid sex, which perpetuates more anxiety and avoidance. Normalizing typical sexual functioning, encouraging couples to “avoid avoidance,” and providing referrals as needed are core elements of relational intervention for ED.

Setting the tone. Family physicians are not routinely trained in couples therapy. However, you can employ communication skills that allow each partner to be heard by using empathic/reflective listening, de-escalation, and reframing. Asking “What effect are the sexual concerns having on both of you?” and “What were the circumstances of the last sexual encounter that were pleasing to both of you?” can help promote intimacy and mutual satisfaction.

Continue to: The behavioral specialist's role

The behavioral specialist’s role

Behavioral health specialists may treat ED using methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy or evidence-based couple interventions.4 Cognitive methods for the treatment of ED include examination of maladaptive thoughts around pressure to perform and achieving sexual pleasure. Behavioral methods for treatment of ED are typically aimed at the de-coupling of anxiety and sexual activity. These treatments can include relaxation and desensitization, specifically sensate focus therapy.15

Sensate focus therapy involves a specific set of prescriptive rules for sexual activity, initially restricting touch to non-demand pleasurable touch (eg, holding hands) that allows couples to connect in a low-anxiety context focused on relaxation and connection. As couples are able to control anxiety while engaging in these activities, they engage in increasingly more intimate activities. Additionally, behavioral health specialists trained in couples therapy are vital to helping increase communication regarding sexual activity, sexual scripts, and the relationship in general.4

Identifying a treatment team

In coordinating couples care in the treatment of ED, enlist the help of a therapist who has specific knowledge and skills in the treatment of sexual disorders. While the number of qualified or certified sex therapists is limited, referring providers can visit the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists Web site (www.aasect.org) for possible referral sources. Another option is the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy Web site (www.aamft.org) under “Find a therapist.” Lastly, the Society for Sex Therapy and Research (www.sstarnet.org) is another professional association that provides information and local referral sources. For patients and partners located in rural areas where access is limited, telehealth options may need to be explored.

THE CASE

Mr. M and his wife were seen for a follow-up appointment by his primary care provider, who ruled out any additional causes of ED (eg, hormonal, vascular), discussed with both the patient and his wife basic sexual health and sexual functioning, dispelled several commonly held myths (ie, individuals cannot obtain an erection because of infidelity or lying), validated sexual concerns as a significant health issue, and prescribed a PDE-5 inhibitor.

Mr. M and his wife were referred to a behavioral health specialist in the clinic who had expertise in couples therapy. At several subsequent visits, the patient and his wife worked on improving the quality and quantity of communication regarding their sexual goals, mutual de-escalation of anxiety, increased emotional intimacy, and sensate focus techniques.

Continue to: As the result of the interventions...

As the result of these interventions, both the patient and his wife were able to engage in sex with less anxiety, and the patient increasingly was able to achieve more satisfactory erections without the use of the PDE-5 inhibitor. At the conclusion of therapy, the patient and his wife reported an increase in sexual satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Buck, PhD, Family Health Center, John Peter Smith Health Network, 1500 S. Main Street, Fort Worth, TX 76104; kbuck@jpshealth.org.

1. Macdowall W, Parker R, Nanchahal K, et al. ‘Talking of Sex’: developing and piloting a sexual health communication tool for use in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:332-337.

2. Sadovsky R. Asking the questions and offering solutions: the ongoing dialogue between the primary care physician and the patient with erectile dysfunction. Rev Urol. 2003;5(suppl 7):S35-S48.

3. Boston University School of Medicine. Sexual Medicine. Epidemiology of ED. 2019. www.bumc.bu.edu/sexualmedicine/physicianinformation/epidemiology-of-ed/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

4. Weeks GR, Gambescia N, Hertlein KM, eds. A Clinician’s Guide to Systemic Sex Therapy. 2nd ed. London, England: Routledge; 2016.

5. Colson MH, Cuzin A, Faix A, et al. Current epidemiology of erectile dysfunction, an update. Sexologies. 2018;27:e7-e13.

6. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94820-94827.

7. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319-326.

8. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:820-827.

9. Dean J, Rubio-Aurioles E, McCabe M, et al. Integrating partners into erectile dysfunction treatment: improving the sexual experience for the couple. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:127-133.

10. Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. Lancet. 2013; 381:153-165.

11. Lo WH, Fu SN, Wong SN, et al. Prevalence, correlates, attitude and treatment seeking of erectile dysfunction among type 2 diabetic Chinese men attending primary care outpatient clinics. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:755-760.

12. Zweifler J, Padilla A, Schafer S. Barriers to recognition of erectile dysfunction among diabetic Mexican-American men. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:259-263.

13. American Urological Society. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline (2018). www.auanet.org/guidelines/erectile-dysfunction-(ed)-guideline. Accessed May 27, 2020.

14. Huang S, Lie J. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the management of erectile dysfunction. P T. 2013;38;414-419.

15. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little Brown; 1970.

1. Macdowall W, Parker R, Nanchahal K, et al. ‘Talking of Sex’: developing and piloting a sexual health communication tool for use in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:332-337.

2. Sadovsky R. Asking the questions and offering solutions: the ongoing dialogue between the primary care physician and the patient with erectile dysfunction. Rev Urol. 2003;5(suppl 7):S35-S48.

3. Boston University School of Medicine. Sexual Medicine. Epidemiology of ED. 2019. www.bumc.bu.edu/sexualmedicine/physicianinformation/epidemiology-of-ed/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

4. Weeks GR, Gambescia N, Hertlein KM, eds. A Clinician’s Guide to Systemic Sex Therapy. 2nd ed. London, England: Routledge; 2016.

5. Colson MH, Cuzin A, Faix A, et al. Current epidemiology of erectile dysfunction, an update. Sexologies. 2018;27:e7-e13.

6. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94820-94827.

7. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319-326.

8. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:820-827.

9. Dean J, Rubio-Aurioles E, McCabe M, et al. Integrating partners into erectile dysfunction treatment: improving the sexual experience for the couple. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:127-133.

10. Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. Lancet. 2013; 381:153-165.

11. Lo WH, Fu SN, Wong SN, et al. Prevalence, correlates, attitude and treatment seeking of erectile dysfunction among type 2 diabetic Chinese men attending primary care outpatient clinics. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:755-760.

12. Zweifler J, Padilla A, Schafer S. Barriers to recognition of erectile dysfunction among diabetic Mexican-American men. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:259-263.

13. American Urological Society. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline (2018). www.auanet.org/guidelines/erectile-dysfunction-(ed)-guideline. Accessed May 27, 2020.

14. Huang S, Lie J. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the management of erectile dysfunction. P T. 2013;38;414-419.

15. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little Brown; 1970.

Biologics may carry melanoma risk for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

The in a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Dermatology.

The studies included in the analysis, however, had limitations, including a lack of those comparing biologic and conventional systemic therapy in psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to Shamarke Esse, MRes, of the division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences at the University of Manchester (England) and colleagues. “We advocate for more large, well-designed studies of this issue to be performed to help improve certainty” regarding this association, they wrote.

Previous studies that have found an increased risk of melanoma in patients on biologics for psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and IBD have “typically used the general population as the comparator,” they noted. There is a large amount of evidence that has established short-term efficacy and safety of biologics, compared with conventional systemic treatments, but concerns about longer-term cancer risk associated with biologics remains a concern. Moreover, they added, “melanoma is a highly immunogenic skin cancer and therefore of concern to patients treated with TNFIs [tumor necrosis factor inhibitors] because melanoma risk increases with suppression of the immune system and TNF-alpha plays an important role in the immune surveillance of tumors.12,13

In their review, the researchers identified seven cohort studies from MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases published between January 1995 and February 2019 that evaluated melanoma risk in about 34,000 patients receiving biologics and 135,370 patients who had never been treated with biologics, and were receiving conventional systemic therapy for psoriasis, RA, or IBD. Of these, four studies were in patients with RA, two studies were in patients with IBD, and a single study was in patients with psoriasis. Six studies examined patients taking TNF inhibitors, but only one of six studies had information on specific TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) in patients with RA. One study evaluated abatacept and rituximab in RA patients.

The researchers analyzed the pooled relative risk across all studies. Compared with patients who received conventional systemic therapy, there was a nonsignificant association with risk of melanoma in patients with psoriasis (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.61-4.09), RA (pooled relative risk, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.83-1.74), and IBD (pRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.60-2.40).

Among RA patients who received TNF inhibitors only, there was a slightly elevated nonsignificant risk of melanoma (pRR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.81-1.43). Patients receiving rituximab had a pRR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.38-1.39), and patients taking abatacept had a pRR of 1.43 (95% CI, 0.66-3.09), compared with RA patients receiving conventional systemic therapy. When excluding two major studies in the RA subgroup of patients in a sensitivity analysis, pooled risk estimates varied from 0.91 (95% CI, 0.69-1.18) to 1.95 (95% CI, 1.16- 3.30). There were no significant between-study heterogeneity or publication bias among the IBD and RA studies.

Mr. Esse and colleagues acknowledged the small number of IBD and psoriasis studies in the meta-analysis, which could affect pooled risk estimates. “Any future update of our study through the inclusion of newly published studies may produce significantly different pooled risk estimates than those reported in our meta-analysis,” they said. In addition, the use of health insurance databases, lack of risk factors for melanoma, and inconsistent information about treatment duration for patients receiving conventional systemic therapy were also limitations.

“Prospective cohort studies using an active comparator, new-user study design providing detailed information on treatment history, concomitant treatments, biologic and conventional systemic treatment duration, recreational and treatment-related UV exposure, skin color, and date of melanoma diagnosis are required to help improve certainty. These studies would also need to account for key risk factors and the latency period of melanoma,” the researchers said.

Mr. Esse disclosed being funded by a PhD studentship from the Psoriasis Association. One author disclosed receiving personal fees from Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, and Novartis outside the study; another disclosed receiving grants and personal fees from those and several other pharmaceutical companies during the study, and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies outside of the submitted work; the fourth author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Esse S et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 20;e201300.

The in a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Dermatology.

The studies included in the analysis, however, had limitations, including a lack of those comparing biologic and conventional systemic therapy in psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to Shamarke Esse, MRes, of the division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences at the University of Manchester (England) and colleagues. “We advocate for more large, well-designed studies of this issue to be performed to help improve certainty” regarding this association, they wrote.

Previous studies that have found an increased risk of melanoma in patients on biologics for psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and IBD have “typically used the general population as the comparator,” they noted. There is a large amount of evidence that has established short-term efficacy and safety of biologics, compared with conventional systemic treatments, but concerns about longer-term cancer risk associated with biologics remains a concern. Moreover, they added, “melanoma is a highly immunogenic skin cancer and therefore of concern to patients treated with TNFIs [tumor necrosis factor inhibitors] because melanoma risk increases with suppression of the immune system and TNF-alpha plays an important role in the immune surveillance of tumors.12,13

In their review, the researchers identified seven cohort studies from MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases published between January 1995 and February 2019 that evaluated melanoma risk in about 34,000 patients receiving biologics and 135,370 patients who had never been treated with biologics, and were receiving conventional systemic therapy for psoriasis, RA, or IBD. Of these, four studies were in patients with RA, two studies were in patients with IBD, and a single study was in patients with psoriasis. Six studies examined patients taking TNF inhibitors, but only one of six studies had information on specific TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) in patients with RA. One study evaluated abatacept and rituximab in RA patients.

The researchers analyzed the pooled relative risk across all studies. Compared with patients who received conventional systemic therapy, there was a nonsignificant association with risk of melanoma in patients with psoriasis (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.61-4.09), RA (pooled relative risk, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.83-1.74), and IBD (pRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.60-2.40).

Among RA patients who received TNF inhibitors only, there was a slightly elevated nonsignificant risk of melanoma (pRR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.81-1.43). Patients receiving rituximab had a pRR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.38-1.39), and patients taking abatacept had a pRR of 1.43 (95% CI, 0.66-3.09), compared with RA patients receiving conventional systemic therapy. When excluding two major studies in the RA subgroup of patients in a sensitivity analysis, pooled risk estimates varied from 0.91 (95% CI, 0.69-1.18) to 1.95 (95% CI, 1.16- 3.30). There were no significant between-study heterogeneity or publication bias among the IBD and RA studies.

Mr. Esse and colleagues acknowledged the small number of IBD and psoriasis studies in the meta-analysis, which could affect pooled risk estimates. “Any future update of our study through the inclusion of newly published studies may produce significantly different pooled risk estimates than those reported in our meta-analysis,” they said. In addition, the use of health insurance databases, lack of risk factors for melanoma, and inconsistent information about treatment duration for patients receiving conventional systemic therapy were also limitations.

“Prospective cohort studies using an active comparator, new-user study design providing detailed information on treatment history, concomitant treatments, biologic and conventional systemic treatment duration, recreational and treatment-related UV exposure, skin color, and date of melanoma diagnosis are required to help improve certainty. These studies would also need to account for key risk factors and the latency period of melanoma,” the researchers said.

Mr. Esse disclosed being funded by a PhD studentship from the Psoriasis Association. One author disclosed receiving personal fees from Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, and Novartis outside the study; another disclosed receiving grants and personal fees from those and several other pharmaceutical companies during the study, and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies outside of the submitted work; the fourth author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Esse S et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 20;e201300.

The in a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Dermatology.

The studies included in the analysis, however, had limitations, including a lack of those comparing biologic and conventional systemic therapy in psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to Shamarke Esse, MRes, of the division of musculoskeletal and dermatological sciences at the University of Manchester (England) and colleagues. “We advocate for more large, well-designed studies of this issue to be performed to help improve certainty” regarding this association, they wrote.

Previous studies that have found an increased risk of melanoma in patients on biologics for psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and IBD have “typically used the general population as the comparator,” they noted. There is a large amount of evidence that has established short-term efficacy and safety of biologics, compared with conventional systemic treatments, but concerns about longer-term cancer risk associated with biologics remains a concern. Moreover, they added, “melanoma is a highly immunogenic skin cancer and therefore of concern to patients treated with TNFIs [tumor necrosis factor inhibitors] because melanoma risk increases with suppression of the immune system and TNF-alpha plays an important role in the immune surveillance of tumors.12,13

In their review, the researchers identified seven cohort studies from MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases published between January 1995 and February 2019 that evaluated melanoma risk in about 34,000 patients receiving biologics and 135,370 patients who had never been treated with biologics, and were receiving conventional systemic therapy for psoriasis, RA, or IBD. Of these, four studies were in patients with RA, two studies were in patients with IBD, and a single study was in patients with psoriasis. Six studies examined patients taking TNF inhibitors, but only one of six studies had information on specific TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) in patients with RA. One study evaluated abatacept and rituximab in RA patients.

The researchers analyzed the pooled relative risk across all studies. Compared with patients who received conventional systemic therapy, there was a nonsignificant association with risk of melanoma in patients with psoriasis (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.61-4.09), RA (pooled relative risk, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.83-1.74), and IBD (pRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.60-2.40).

Among RA patients who received TNF inhibitors only, there was a slightly elevated nonsignificant risk of melanoma (pRR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.81-1.43). Patients receiving rituximab had a pRR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.38-1.39), and patients taking abatacept had a pRR of 1.43 (95% CI, 0.66-3.09), compared with RA patients receiving conventional systemic therapy. When excluding two major studies in the RA subgroup of patients in a sensitivity analysis, pooled risk estimates varied from 0.91 (95% CI, 0.69-1.18) to 1.95 (95% CI, 1.16- 3.30). There were no significant between-study heterogeneity or publication bias among the IBD and RA studies.

Mr. Esse and colleagues acknowledged the small number of IBD and psoriasis studies in the meta-analysis, which could affect pooled risk estimates. “Any future update of our study through the inclusion of newly published studies may produce significantly different pooled risk estimates than those reported in our meta-analysis,” they said. In addition, the use of health insurance databases, lack of risk factors for melanoma, and inconsistent information about treatment duration for patients receiving conventional systemic therapy were also limitations.

“Prospective cohort studies using an active comparator, new-user study design providing detailed information on treatment history, concomitant treatments, biologic and conventional systemic treatment duration, recreational and treatment-related UV exposure, skin color, and date of melanoma diagnosis are required to help improve certainty. These studies would also need to account for key risk factors and the latency period of melanoma,” the researchers said.

Mr. Esse disclosed being funded by a PhD studentship from the Psoriasis Association. One author disclosed receiving personal fees from Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, and Novartis outside the study; another disclosed receiving grants and personal fees from those and several other pharmaceutical companies during the study, and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies outside of the submitted work; the fourth author had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Esse S et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 20;e201300.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Acute rhinosinusitis: When to prescribe an antibiotic

An estimated 30 million cases of acute rhinosinusitis (ARS) occur every year in the United States.1 More than 80% of people with ARS are prescribed antibiotics in North America, accounting for 15% to 20% of all antibiotic prescriptions in the adult outpatient setting.2,3 Many of these prescriptions are unnecessary, as the most common cause of ARS is a virus.4,5 Evidence consistently shows that symptoms of ARS will resolve spontaneously in most patients and that only those patients with severe or prolonged symptoms require consideration of antibiotic therapy.1,2,4,6 Nearly half of all patients will improve within 1 week and two-thirds of patients will improve within 2 weeks without the use of antibiotics.7 In children, only about 6% to 7% presenting with upper respiratory symptoms meet the criteria for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS),8 which we’ll detail in a bit. For most patients, treatment should consist of symptom management.5

But what about the minority who require antibiotic therapy? This article reviews how to evaluate patients with ARS, identify those who require antibiotics, and prescribe the most appropriate antibiotic treatment regimens.

Diagnosis: Distinguishing viral from bacterial disease

ARS is defined as the sudden onset of purulent nasal discharge plus either nasal blockage or facial pressure/pain lasting < 4 weeks.3,9 Additional signs and symptoms may include postnasal drip, a reduced sense of smell, sinus tenderness to palpation, and maxillary toothaches.10,11

ARS may be viral or bacterial in etiology, with the most common bacterial organisms being Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.1,3,5 The most common viral causes are influenza, parainfluenza, and rhinovirus. Approximately 90% to 98% of cases of ARS are viral6,11; only about 0.5% to 2% of viral rhinosinusitis episodes are complicated by bacterial infection.1,10-12

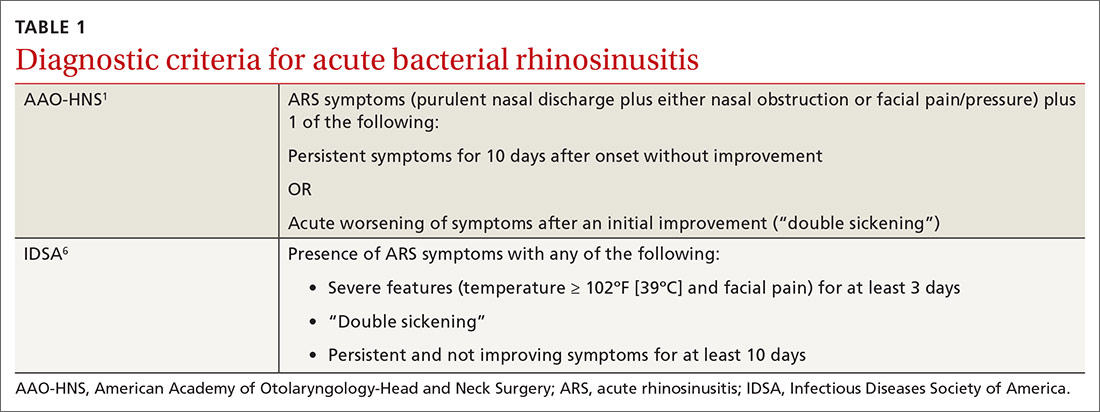

Diagnose ABRS when symptoms of ARS fail to improve after 10 days or symptoms of ARS worsen within 10 days after initial improvement (“double sickening”).1,11 Symptoms that are significantly associated with ABRS are unilateral sinus pain and reported maxillary pain. The presence of facial or dental pain correlates with ABRS but does not identify the specific sinus involved.1

There isn’t good correlation between patients saying they have sinusitis and actually having it.13 A 2019 meta-analysis by Ebell et al14 reported that based on limited data, the overall clinical impression, fetid odor on the breath, and pain in the teeth are the best individual clinical predictors of ABRS.

As recommended by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), a diagnosis of ABRS is also reasonable in patients who present with severe symptoms at the onset.6 Although there is no consensus about what constitutes “severe symptoms,” they are often described as a temperature ≥ 102°F (39°C) plus 3 to 4 days of purulent nasal drainage.1,4,6

Continue to: Additional symptoms of ABRS may include...

Additional symptoms of ABRS may include cough, fatigue, decreased or lack of sense of smell (hyposmia or anosmia), and ear pressure.10 Another sign of “double sickening” is the development of a fever after several days of symptoms.1,9,15 Viral sinusitis typically lasts 5 to 7 days with a peak at days 2 to 3.1,15 If symptoms continue for 10 days, there is a 60% chance of bacterial sinusitis, although some viral rhinosinusitis symptoms persist for > 14 days.1,5 Beyond 4 to 12 weeks, sinusitis is classified as subacute or chronic.3

Physical exam findings and the limited roles of imaging and labs

Common physical exam findings associated with the diagnosis of ABRS include altered speech indicating nasal obstruction; edema or erythema of the skin indicating congested capillaries; tenderness to palpation over the cheeks or upper teeth; odorous breath; and purulent drainage from the nose or in the posterior pharynx.

In a study by Hansen et al13 (N = 174), the only sign that showed significant association with ABRS (diagnosed by sinus aspiration or lavage) was unilateral tenderness of the maxillary sinuses. The presence of purulent drainage in the nose or posterior pharynx also has significant diagnostic value, as it predicts the presence of bacteria on antral aspiration.1 Purulent discharge in the pharynx is associated with a higher likelihood of benefit from antibiotic therapy compared to placebo (number needed to treat [NNT] = 8).16 However, colored nasal discharge indicates the presence of neutrophils—not bacteria—and does not predict the likelihood of bacterial sinus infection.14,17 Therefore, the history and physical exam should focus on location of pain (sinus and/or teeth), duration of symptoms, presence of fever, change in symptom severity, attempted home therapies, sinus tenderness on exam, breath odor, and purulent drainage seen in the nasal cavity or posterior pharynx.13,14

Radiographic imaging has no role in the diagnosis or treatment of uncomplicated ABRS because viral and bacterial etiologies have similar radiographic appearances. Additionally, employing radiologic imaging would increase health care costs by at least 4-fold.5,6,8,17 The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) clinical practice guidelines recommend against radiographic imaging for patients who meet the diagnostic criteria for ABRS unless concern exists for a complication or an alternate diagnosis is suspected.1 Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the sinuses may be warranted in patients with severe headaches, facial swelling, cranial nerve palsies, or bulging of the eye (proptosis), all of which indicate a potential complication of ABRS.1

Laboratory evaluations. ABRS is a clinical diagnosis; therefore, routine lab work, such as a white blood cell count, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), are not indicated unless an alternate diagnosis is suspected.1,5,13,18,19

Continue to: In one study...

In one study, CRP > 10 mg/L and ESR > 10 mm/h were the strongest individual predictors of purulent antral puncture aspirate or positive bacterial culture of aspirate, which is considered diagnostic for ABRS. 20 However, CRP and ESR by themselves are not adequate to diagnose ABRS.20 This study developed a clinical decision rule that used symptoms, signs, and laboratory values to rate the likelihood of ABRS as being either low, moderate, or high. However, this clinical decision rule has not been prospectively validated.

Thus, CRP and ESR elevations can support the diagnosis of ABRS, but the low sensitivity of these tests precludes their use as a screening tool for ABRS.14,18 Studies by Ebell19 and Huang21 have shown some benefit to dipstick assay of nasal secretions for the diagnosis of ABRS, but this method is not validated or widely used.19,21

Treatment: From managing symptoms to prescribing antibiotics

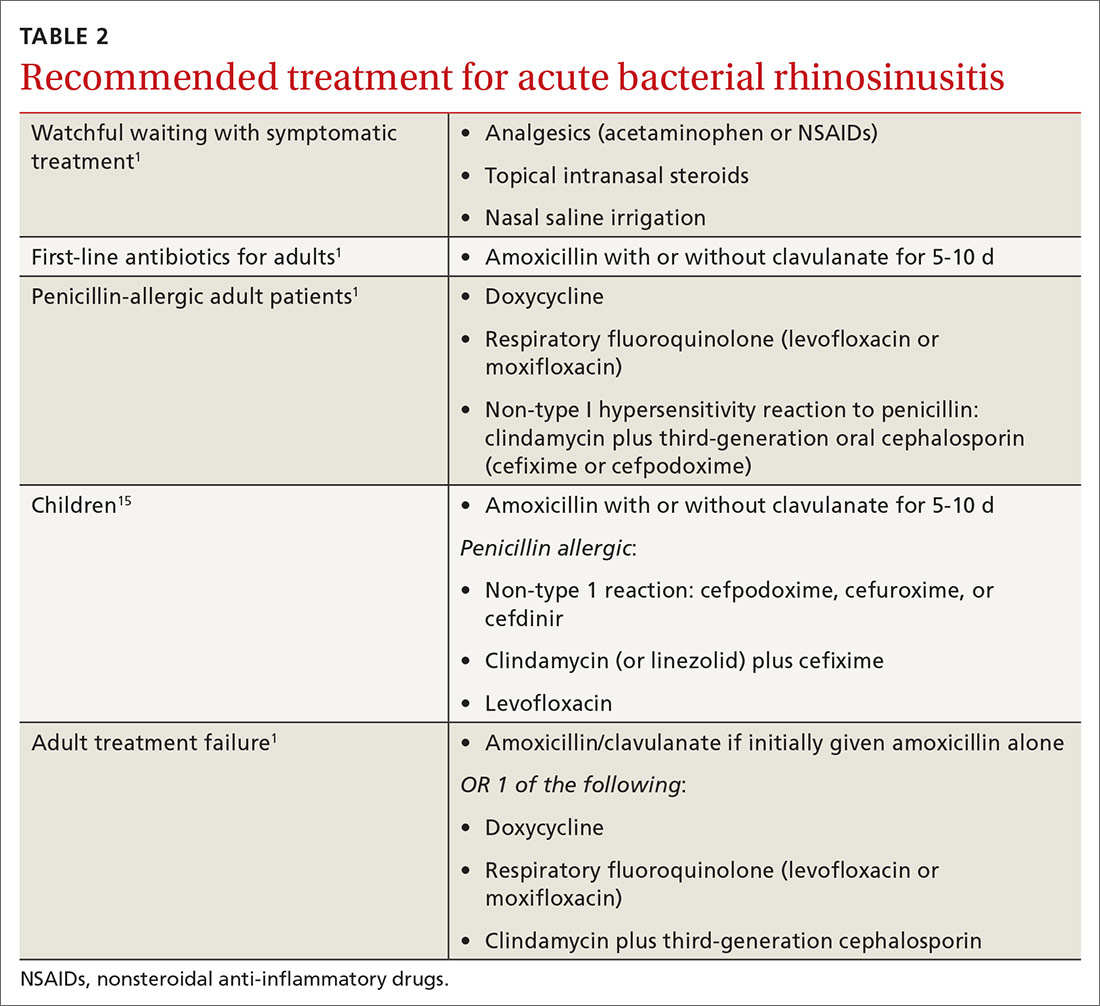

Overprescribing antibiotics for ARS is a prominent health care issue. In fact, 5 of 9 placebo-controlled studies showed that most people improve within 2 weeks regardless of antibiotic use (N = 1058).3 Therefore, weigh the decision to treat ABRS with antibiotics against the risk for potential adverse reactions and within the context of antibiotic stewardship.2,9,12,22-24 Consider antibiotics only if patients meet the diagnostic criteria for ABRS (TABLE 11,6) or, occasionally, for patients with severe symptoms upon presentation, such as a temperature ≥ 102°F (39°C) plus purulent nasal discharge for 3 to 4 days.1 The most commonly reported adverse effects of antibiotics are gastrointestinal in nature and include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.2,9

Symptomatic management for both ARS and ABRS is recommended as first-line therapy; it should be offered to patients before making a diagnosis of ABRS.1,5,9,25 Consider using analgesics, topical intranasal steroids, and/or nasal saline irrigation to alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life.1,5,25 Interventions with questionable or unproven efficacy include the use of antihistamines, systemic steroids, decongestants, and mucolytics, but they may be considered on an individual basis.1 A systematic review found that topical nasal steroids relieved facial pain and nasal congestion in patients with rhinitis and acute sinusitis (NNT = 14).1,26

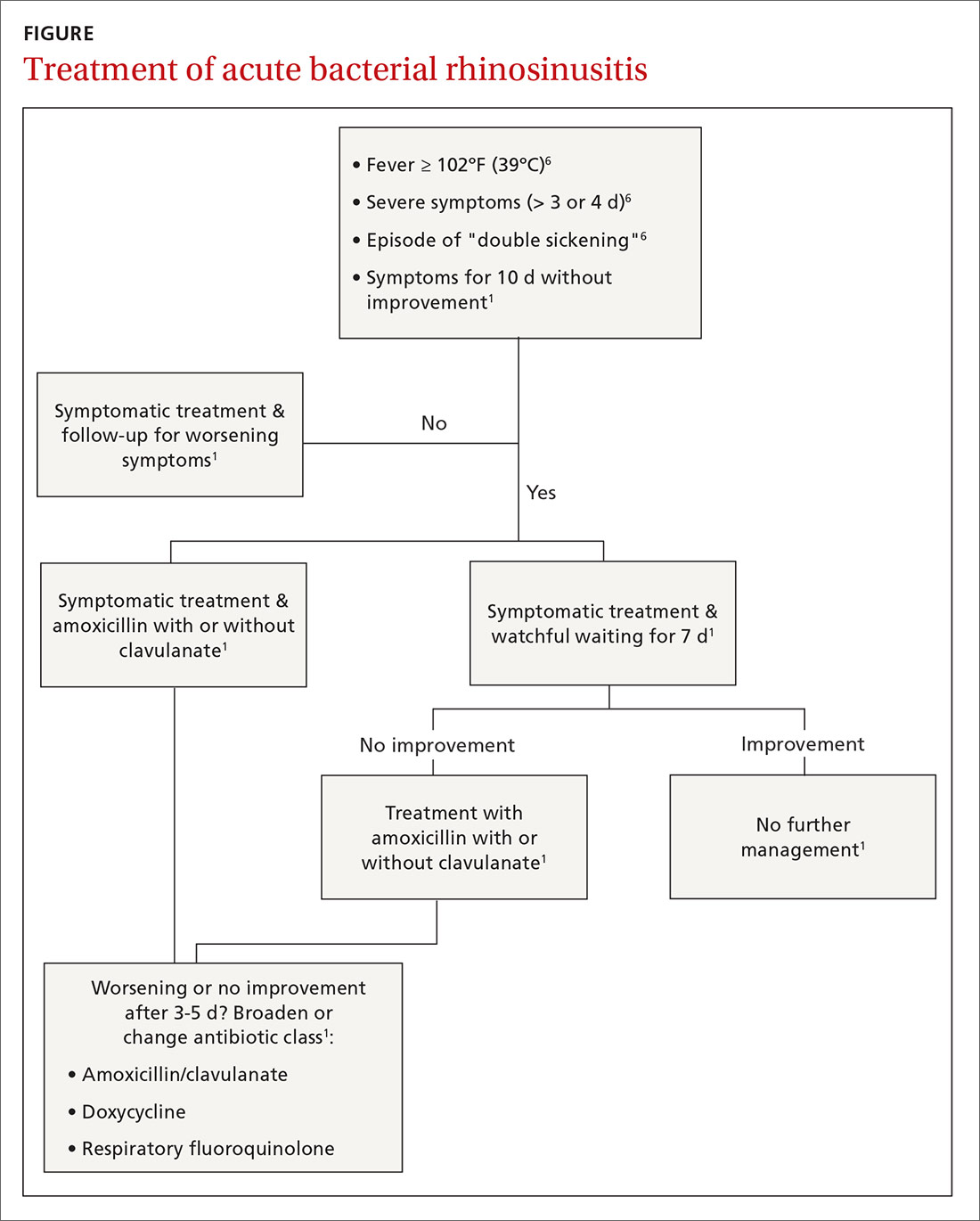

Even after diagnosing ABRS, clinicians should offer watchful waiting and symptomatic therapies as long as patients have adequate access to follow-up (TABLE 2,1,15FIGURE1,6). Antibiotic therapy can then be initiated if symptoms do not improve after an additional 7 days of watchful waiting or if symptoms worsen at any time. It is reasonable to give patients a prescription to keep on hand to be used if symptoms worsen, with instructions to notify the provider if antibiotics are started.1

Continue to: Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotic therapy. The rationale for treating ABRS with antibiotics is to expedite recovery and prevent complications such as periorbital or orbital cellulitis, meningitis, frontal osteomyelitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and other serious illness.27 Antibiotic treatment is associated with a shorter duration of symptoms (NNT = 19) but an increased risk of adverse events (NNH = 8).7,19

Amoxicillin with or without clavulanate for 5 to 10 days is first-line antibiotic therapy for most adults with ABRS.1,3,5,8,9,11 Per AAO-HNS, the “justification for amoxicillin as first-line treatment relates to its safety, efficacy, low cost, and narrow microbiologic spectrum.”1 Amoxicillin may be dosed 500 mg tid for 5 to 10 days. Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) is recommended for patients with comorbid conditions or with increased risk of bacterial resistance. Dosing for amoxicillin/clavulanate is 500/125 mg tid or 875/125 mg bid for 5 to 10 days. Duration of therapy should be determined by the severity of symptoms.5

For penicillin-allergic patients, doxycycline or a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) is considered first-line treatment.1,6 Doxycycline is preferred because of its narrower spectrum and fewer adverse effects than the fluoroquinolones. Fluoroquinolones should be reserved for patients who fail first-line treatment and are penicillin allergic.1 Because of the high rates of resistance among S pneumoniae and H influenzae, macrolides, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), and cephalosporins are not recommended as first-line therapy.1,5

How antibiotic options compare. A Cochrane review of 54 studies comparing different antibiotics showed no antibiotic was superior.3 Of the 54 studies, 6 studies (N = 1887) were pooled to compare cephalosporins to amoxicillin/clavulanate at 7 to 15 days. The findings indicated a statistically significant difference for amoxicillin/clavulanate with a relative risk (RR) of 1.37 (confidence interval [CI], 1.04-1.8).3 However, none of these 6 studies were graded as having a low risk of bias; therefore, confidence in this finding was deemed limited due to the quality of included studies. The failure rate for cephalosporins was 12% vs 8% for amoxicillin/clavulanate.3

Treatment failure is considered when a patient has not improved by Day 7 after ABRS diagnosis (with or without medication) or when symptoms worsen at any time. If watchful waiting was chosen and a safety net prescription was provided, the antibiotics should be filled and started. If no antibiotic was prescribed at the time watchful waiting commenced, the patient should return for further evaluation and be started on antibiotics. If antibiotics were prescribed initially for severe symptoms, a change in antibiotic therapy is indicated, and a broader-spectrum antibiotic should be chosen. If amoxicillin was prescribed, the patient should be switched to amoxicillin/clavulanate, doxycycline, a respiratory fluoroquinolone, or a combination of clindamycin plus a third-generation cephalosporin.1

Continue to: Diagnosis and management of pediatric patients

Diagnosis and management of pediatric patients

Diagnosis of ABRS in children is defined as an acute upper respiratory infection (URI) accompanied by persistent nasal discharge, daytime cough for ≥ 10 days without improvement, an episode of “double sickening,” or severe onset with a temperature ≥ 102°F and purulent nasal discharge for 3 days.15

Initial presentations of viral URIs and ABRS are almost identical; thus, persistence of symptoms is key to diagnosis.6 Nasal discharge tends to appear several days after initial symptoms manifest for viral infections including influenza. In children < 5 years of age, the most common complication involves the orbit.15 Orbital complications generally manifest with eye pain and/or periorbital swelling and may be accompanied by proptosis or decreased functioning of extraocular musculature. The differential diagnosis for orbital complications includes cavernous sinus thrombosis, orbital cellulitis/abscess, subperiosteal abscess, and inflammatory edema.27,28 Intracranial complications are also possible with severe ABRS.12

Radiology studies are not recommended for the initial diagnosis of ABRS in children, as again, imaging does not differentiate between viral and bacterial etiologies. However, in children with complications such as orbital or cerebral involvement, a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the paranasal sinuses is indicated.15

Antibiotic therapy is indicated in children with a diagnosis of severe ABRS or in cases of “double sickening.” Clinicians may consider watchful waiting for 3 additional days before initiating antibiotics in patients meeting criteria for ABRS.Amoxicillin with or without clavulanate is the antibiotic of choice.15

For penicillin-allergic children without a history of anaphylactoid reaction, treatment with cefpodoxime, cefdinir, or cefuroxime is appropriate. For children with a history of anaphylaxis, treatment with a combination of clindamycin (or linezolid) and cefixime is indicated. Alternatively, a fluoroquinolone such as levofloxacin may be used, but adverse effects and emerging resistance limit its use.15

Continue to: Specialist referral

Specialist referral

Referral to Otolaryngology is indicated for patients with > 3 episodes of clinically diagnosed bacterial sinusitis in 1 year, evidence of fungal disease (which is outside the scope of this article), immunocompromised status, or a persistent temperature ≥ 102°F despite antibiotic therapy. Also consider otolaryngology referral for patients with a history of sinus surgery.2,5,6

CORRESPONDENCE

Pamela R. Hughes, Family Medicine Residency Clinic, Mike O’Callaghan Military Medical Center, 4700 Las Vegas Boulevard North, Nellis AFB, NV 89191; pamela.r.hughes4.mil@mail.mil.

1. Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(2 suppl):S1-S39.

2. Fokkens WJ, Hoffmans R, Thomas M. Avoid prescribing antibiotics in acute rhinosinusitis. BMJ. 2014;349:g5703.

3. Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Rautakorpi UM, Borisenko OV, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD000243.

4. Burgstaller, JM, Steurer J, Holzmann D, et al. Antibiotic efficacy in patients with a moderate probability of acute rhinosinusitis: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1067-1077.

5. Aring AM, Chan MM. Current concepts in adult acute rhinosinusitis. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:97-105.

6. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e72-e112.