User login

FDA approves label extension for dapagliflozin

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a label extension for Farxiga (dapagliflozin) and Xigduo XR (extended-release dapagliflozin and metformin HCl) for use in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment, lowering the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) threshold to 45 mL/min per 1.73 m2 from the current60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The update is based on results from DERIVE, a phase 3 study in patients with inadequately controlled diabetes and an eGFR of 45-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2 who received either dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo during a 24-week period. After that time, patients who received dapagliflozin had significant reductions in glycosylated hemoglobin, compared with placebo. The safety profile was similar to that in other studies with dapagliflozin.

The most common adverse events associated with Farxiga are female genital mycotic infections, nasopharyngitis, and urinary tract infections. For Xigduo XR, the most common adverse events are female genital mycotic infection, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, diarrhea, and headache.

“The DERIVE study, which further confirmed the well-established efficacy and safety profile for Farxiga and Xigduo XR, has resulted in important label changes for patients with type 2 diabetes that enable a broader population with impaired renal function to potentially benefit from these important treatment options,” Jim McDermott, PhD, vice president, U.S. medical affairs, diabetes, at AstraZeneca, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the AstraZeneca website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a label extension for Farxiga (dapagliflozin) and Xigduo XR (extended-release dapagliflozin and metformin HCl) for use in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment, lowering the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) threshold to 45 mL/min per 1.73 m2 from the current60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The update is based on results from DERIVE, a phase 3 study in patients with inadequately controlled diabetes and an eGFR of 45-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2 who received either dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo during a 24-week period. After that time, patients who received dapagliflozin had significant reductions in glycosylated hemoglobin, compared with placebo. The safety profile was similar to that in other studies with dapagliflozin.

The most common adverse events associated with Farxiga are female genital mycotic infections, nasopharyngitis, and urinary tract infections. For Xigduo XR, the most common adverse events are female genital mycotic infection, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, diarrhea, and headache.

“The DERIVE study, which further confirmed the well-established efficacy and safety profile for Farxiga and Xigduo XR, has resulted in important label changes for patients with type 2 diabetes that enable a broader population with impaired renal function to potentially benefit from these important treatment options,” Jim McDermott, PhD, vice president, U.S. medical affairs, diabetes, at AstraZeneca, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the AstraZeneca website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a label extension for Farxiga (dapagliflozin) and Xigduo XR (extended-release dapagliflozin and metformin HCl) for use in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment, lowering the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) threshold to 45 mL/min per 1.73 m2 from the current60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The update is based on results from DERIVE, a phase 3 study in patients with inadequately controlled diabetes and an eGFR of 45-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2 who received either dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo during a 24-week period. After that time, patients who received dapagliflozin had significant reductions in glycosylated hemoglobin, compared with placebo. The safety profile was similar to that in other studies with dapagliflozin.

The most common adverse events associated with Farxiga are female genital mycotic infections, nasopharyngitis, and urinary tract infections. For Xigduo XR, the most common adverse events are female genital mycotic infection, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, diarrhea, and headache.

“The DERIVE study, which further confirmed the well-established efficacy and safety profile for Farxiga and Xigduo XR, has resulted in important label changes for patients with type 2 diabetes that enable a broader population with impaired renal function to potentially benefit from these important treatment options,” Jim McDermott, PhD, vice president, U.S. medical affairs, diabetes, at AstraZeneca, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the AstraZeneca website.

Growing spot on nose

The FP was concerned that this could be melanoma.

He used his dermatoscope and saw suspicious patterns that included polygonal lines and circle-within-circle patterns. He informed the patient about his concerns for melanoma and discussed the need for a biopsy. After obtaining informed consent, the FP injected the patient’s nose with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. (See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). The FP used a Dermablade to perform a broad shave biopsy, which revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma in situ (also known as lentigo maligna). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy”)

During the follow-up visit, the FP presented the patient with 2 options for treatment: topical imiquimod for 3 months or Mohs surgery. The FP recommended Mohs surgery because the data for topical imiquimod in the treatment of lentigo maligna indicate that it is less effective on the nose than other areas of the face. The patient agreed to surgery, and the FP sent the referral and the photo of the original lesion to the Mohs surgeon. The outcome was good, and the need for ongoing sun safety and regular skin surveillance was explained to the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was concerned that this could be melanoma.

He used his dermatoscope and saw suspicious patterns that included polygonal lines and circle-within-circle patterns. He informed the patient about his concerns for melanoma and discussed the need for a biopsy. After obtaining informed consent, the FP injected the patient’s nose with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. (See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). The FP used a Dermablade to perform a broad shave biopsy, which revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma in situ (also known as lentigo maligna). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy”)

During the follow-up visit, the FP presented the patient with 2 options for treatment: topical imiquimod for 3 months or Mohs surgery. The FP recommended Mohs surgery because the data for topical imiquimod in the treatment of lentigo maligna indicate that it is less effective on the nose than other areas of the face. The patient agreed to surgery, and the FP sent the referral and the photo of the original lesion to the Mohs surgeon. The outcome was good, and the need for ongoing sun safety and regular skin surveillance was explained to the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was concerned that this could be melanoma.

He used his dermatoscope and saw suspicious patterns that included polygonal lines and circle-within-circle patterns. He informed the patient about his concerns for melanoma and discussed the need for a biopsy. After obtaining informed consent, the FP injected the patient’s nose with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine for anesthesia and to prevent bleeding. Remember, it is safe to use injectable epinephrine along with lidocaine when doing surgery on the nose. (See “Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths”). The FP used a Dermablade to perform a broad shave biopsy, which revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma in situ (also known as lentigo maligna). (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy”)

During the follow-up visit, the FP presented the patient with 2 options for treatment: topical imiquimod for 3 months or Mohs surgery. The FP recommended Mohs surgery because the data for topical imiquimod in the treatment of lentigo maligna indicate that it is less effective on the nose than other areas of the face. The patient agreed to surgery, and the FP sent the referral and the photo of the original lesion to the Mohs surgeon. The outcome was good, and the need for ongoing sun safety and regular skin surveillance was explained to the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Will having fewer primary care physicians shorten Americans’ lifespans?

Opportunities are being missed for advance care planning for elderly ICU patients. Insulin-treated diabetes in pregnancy carries a strong preterm risk. And U.S. measles cases are up to 159 for the year.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Opportunities are being missed for advance care planning for elderly ICU patients. Insulin-treated diabetes in pregnancy carries a strong preterm risk. And U.S. measles cases are up to 159 for the year.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Opportunities are being missed for advance care planning for elderly ICU patients. Insulin-treated diabetes in pregnancy carries a strong preterm risk. And U.S. measles cases are up to 159 for the year.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

KATHERINE trial and breast cancer

In this episode, Charles E. Geyer, MD, of Virginia Commonweath University joins guest host Jame Abraham, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic to discuss the KATHERINE trial and its impact on the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer.

And Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD, talks about whether it’s better for physicians to be vague about prognosis. Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University and is also a columnist for Hematology News. More from Dr. Yurkiewicz here.

Subscribe to Blood & Cancer here:

Apple PodcastsGoogle Podcasts

In this episode, Charles E. Geyer, MD, of Virginia Commonweath University joins guest host Jame Abraham, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic to discuss the KATHERINE trial and its impact on the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer.

And Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD, talks about whether it’s better for physicians to be vague about prognosis. Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University and is also a columnist for Hematology News. More from Dr. Yurkiewicz here.

Subscribe to Blood & Cancer here:

Apple PodcastsGoogle Podcasts

In this episode, Charles E. Geyer, MD, of Virginia Commonweath University joins guest host Jame Abraham, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic to discuss the KATHERINE trial and its impact on the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer.

And Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD, talks about whether it’s better for physicians to be vague about prognosis. Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University and is also a columnist for Hematology News. More from Dr. Yurkiewicz here.

Subscribe to Blood & Cancer here:

Apple PodcastsGoogle Podcasts

Over 20 Years, Pain Is on the Rise

Pain is becoming a fact of life for more and more people, and they are turning to opioids to treat it, according to a survey sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Researchers looked at nearly 2 decades-worth of cumulative data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). They found that since 1997/1998, pain prevalence in US adults rose by 25%.

In 1997/1998, about 33% of American adults had at ≤ 1 painful health condition. In 2013/2014, that proportion was 41%. For about 68 million people, moderate-to-severe pain was interfering with normal work activities. And those people were turning more often to strong opioids—eg, fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone—for help. Use of opioids to manage pain more than doubled in just 10 years: from 4.1 million (11.5%) in 2001/2002 to 10.5 million (24.3%) in 2013/2014.

People with severe pain-related interference also were more likely to have had > 4 opioid prescriptions and to have visited a doctor’s office > 6 times for pain compared with those with minimal pain-related interference.

Opioid use peaked between 2005 and 2012, but since 2012, opioid use has slightly declined. The researchers say this ties to a reduction in use of weak opioids and in the number of patients reporting only 1 opioid prescription.

The survey also found some small downward shifts in health care visits. Ambulatory office visits plateaued between 2001/2002 and 2007/2008 and decreased through 2013/2014. The researchers also found small but statistically significant drops in pain-related emergency department visits and overnight hospital stays.

The researchers say their findings suggest more education about the risk/benefit ratio of opioids “appears warranted.”

Pain is becoming a fact of life for more and more people, and they are turning to opioids to treat it, according to a survey sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Researchers looked at nearly 2 decades-worth of cumulative data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). They found that since 1997/1998, pain prevalence in US adults rose by 25%.

In 1997/1998, about 33% of American adults had at ≤ 1 painful health condition. In 2013/2014, that proportion was 41%. For about 68 million people, moderate-to-severe pain was interfering with normal work activities. And those people were turning more often to strong opioids—eg, fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone—for help. Use of opioids to manage pain more than doubled in just 10 years: from 4.1 million (11.5%) in 2001/2002 to 10.5 million (24.3%) in 2013/2014.

People with severe pain-related interference also were more likely to have had > 4 opioid prescriptions and to have visited a doctor’s office > 6 times for pain compared with those with minimal pain-related interference.

Opioid use peaked between 2005 and 2012, but since 2012, opioid use has slightly declined. The researchers say this ties to a reduction in use of weak opioids and in the number of patients reporting only 1 opioid prescription.

The survey also found some small downward shifts in health care visits. Ambulatory office visits plateaued between 2001/2002 and 2007/2008 and decreased through 2013/2014. The researchers also found small but statistically significant drops in pain-related emergency department visits and overnight hospital stays.

The researchers say their findings suggest more education about the risk/benefit ratio of opioids “appears warranted.”

Pain is becoming a fact of life for more and more people, and they are turning to opioids to treat it, according to a survey sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Researchers looked at nearly 2 decades-worth of cumulative data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). They found that since 1997/1998, pain prevalence in US adults rose by 25%.

In 1997/1998, about 33% of American adults had at ≤ 1 painful health condition. In 2013/2014, that proportion was 41%. For about 68 million people, moderate-to-severe pain was interfering with normal work activities. And those people were turning more often to strong opioids—eg, fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone—for help. Use of opioids to manage pain more than doubled in just 10 years: from 4.1 million (11.5%) in 2001/2002 to 10.5 million (24.3%) in 2013/2014.

People with severe pain-related interference also were more likely to have had > 4 opioid prescriptions and to have visited a doctor’s office > 6 times for pain compared with those with minimal pain-related interference.

Opioid use peaked between 2005 and 2012, but since 2012, opioid use has slightly declined. The researchers say this ties to a reduction in use of weak opioids and in the number of patients reporting only 1 opioid prescription.

The survey also found some small downward shifts in health care visits. Ambulatory office visits plateaued between 2001/2002 and 2007/2008 and decreased through 2013/2014. The researchers also found small but statistically significant drops in pain-related emergency department visits and overnight hospital stays.

The researchers say their findings suggest more education about the risk/benefit ratio of opioids “appears warranted.”

ICU admissions raise chronic condition risk

SAN DIEGO – The research showed rising likelihood of conditions such as depression, diabetes, and heart disease.

By merging two existing databases, the researchers were able to capture a more comprehensive picture of post-ICU patients. “We were able to include almost the entire country,” Ilse van Beusekom, a PhD candidate in health sciences at the University of Amsterdam and data manager at the National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) foundation, said in an interview.

Ms. van Beusekom presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in Critical Care Medicine.

The work compared 56,760 ICU survivors from 81 facilities across the Netherlands to 75,232 age-, sex-, and socioeconomic status–matched controls. The mean age was 65 years and 60% of the population was male. “The types of chronic conditions are the same, only the prevalences are different,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

The researchers compared chronic conditions in the year before ICU admission and the year after, based on data pulled from the NICE national quality database, which includes data describing the first 24 hours of ICU admission, and the Vektis insurance claims database, which includes information on medical treatment. Before ICU admission, 45% of the ICU population was free of chronic conditions, as were 62% of controls. One chronic condition was present in 36% of ICU patients, versus 29% of controls, and two or more conditions were present in 19% versus 9% of controls.

The ICU population was more likely to have high cholesterol (16% vs. 14%), heart disease (14% vs. 6%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8% vs. 3%), type II diabetes (8% vs. 6%), type I diabetes (6% vs. 3%), and depression (6% vs. 4%).

The ICU population also was at greater risk of developing one or more new chronic conditions during the year following their stay. The risk was three- to fourfold higher throughout age ranges.

The study suggests the need for greater follow-up after an ICU admission in order to help patients cope with lingering problems. Ms. van Beusekom noted that there are follow-up programs in the Netherlands for several patient groups, but none for ICU survivors. One possibility would be to have the patient return to the ICU 3 months or so after release to discuss their diagnosis, treatment, and any lingering concerns. “A lot of people don’t know that their complaints are linked with the ICU visit,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

Timothy G. Buchman, MD, professor of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta, who moderated the session, wondered why the ICU seems to be an inflection point for developing new chronic conditions. Could it simply be because patients are sicker to begin with and have reached an inflection point of their illness, or could the treatments in ICU be contributing to or exposing those conditions? Ms. van Beusekom believed it was likely a combination of factors, and she referred to data she had not presented showing that even control patients who had been to the hospital (though not the ICU) during the study period were at lower risk of new chronic conditions than ICU patients.

Ms. van Beusekom’s group plans to investigate ICU-related variables that might be associated with risk of chronic conditions.

The study was not funded. Ms. van Beusekom had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: van Beusekom I et al. CCC48, Abstract Crit Care Med. 2019;47:324-30.

SAN DIEGO – The research showed rising likelihood of conditions such as depression, diabetes, and heart disease.

By merging two existing databases, the researchers were able to capture a more comprehensive picture of post-ICU patients. “We were able to include almost the entire country,” Ilse van Beusekom, a PhD candidate in health sciences at the University of Amsterdam and data manager at the National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) foundation, said in an interview.

Ms. van Beusekom presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in Critical Care Medicine.

The work compared 56,760 ICU survivors from 81 facilities across the Netherlands to 75,232 age-, sex-, and socioeconomic status–matched controls. The mean age was 65 years and 60% of the population was male. “The types of chronic conditions are the same, only the prevalences are different,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

The researchers compared chronic conditions in the year before ICU admission and the year after, based on data pulled from the NICE national quality database, which includes data describing the first 24 hours of ICU admission, and the Vektis insurance claims database, which includes information on medical treatment. Before ICU admission, 45% of the ICU population was free of chronic conditions, as were 62% of controls. One chronic condition was present in 36% of ICU patients, versus 29% of controls, and two or more conditions were present in 19% versus 9% of controls.

The ICU population was more likely to have high cholesterol (16% vs. 14%), heart disease (14% vs. 6%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8% vs. 3%), type II diabetes (8% vs. 6%), type I diabetes (6% vs. 3%), and depression (6% vs. 4%).

The ICU population also was at greater risk of developing one or more new chronic conditions during the year following their stay. The risk was three- to fourfold higher throughout age ranges.

The study suggests the need for greater follow-up after an ICU admission in order to help patients cope with lingering problems. Ms. van Beusekom noted that there are follow-up programs in the Netherlands for several patient groups, but none for ICU survivors. One possibility would be to have the patient return to the ICU 3 months or so after release to discuss their diagnosis, treatment, and any lingering concerns. “A lot of people don’t know that their complaints are linked with the ICU visit,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

Timothy G. Buchman, MD, professor of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta, who moderated the session, wondered why the ICU seems to be an inflection point for developing new chronic conditions. Could it simply be because patients are sicker to begin with and have reached an inflection point of their illness, or could the treatments in ICU be contributing to or exposing those conditions? Ms. van Beusekom believed it was likely a combination of factors, and she referred to data she had not presented showing that even control patients who had been to the hospital (though not the ICU) during the study period were at lower risk of new chronic conditions than ICU patients.

Ms. van Beusekom’s group plans to investigate ICU-related variables that might be associated with risk of chronic conditions.

The study was not funded. Ms. van Beusekom had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: van Beusekom I et al. CCC48, Abstract Crit Care Med. 2019;47:324-30.

SAN DIEGO – The research showed rising likelihood of conditions such as depression, diabetes, and heart disease.

By merging two existing databases, the researchers were able to capture a more comprehensive picture of post-ICU patients. “We were able to include almost the entire country,” Ilse van Beusekom, a PhD candidate in health sciences at the University of Amsterdam and data manager at the National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) foundation, said in an interview.

Ms. van Beusekom presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in Critical Care Medicine.

The work compared 56,760 ICU survivors from 81 facilities across the Netherlands to 75,232 age-, sex-, and socioeconomic status–matched controls. The mean age was 65 years and 60% of the population was male. “The types of chronic conditions are the same, only the prevalences are different,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

The researchers compared chronic conditions in the year before ICU admission and the year after, based on data pulled from the NICE national quality database, which includes data describing the first 24 hours of ICU admission, and the Vektis insurance claims database, which includes information on medical treatment. Before ICU admission, 45% of the ICU population was free of chronic conditions, as were 62% of controls. One chronic condition was present in 36% of ICU patients, versus 29% of controls, and two or more conditions were present in 19% versus 9% of controls.

The ICU population was more likely to have high cholesterol (16% vs. 14%), heart disease (14% vs. 6%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8% vs. 3%), type II diabetes (8% vs. 6%), type I diabetes (6% vs. 3%), and depression (6% vs. 4%).

The ICU population also was at greater risk of developing one or more new chronic conditions during the year following their stay. The risk was three- to fourfold higher throughout age ranges.

The study suggests the need for greater follow-up after an ICU admission in order to help patients cope with lingering problems. Ms. van Beusekom noted that there are follow-up programs in the Netherlands for several patient groups, but none for ICU survivors. One possibility would be to have the patient return to the ICU 3 months or so after release to discuss their diagnosis, treatment, and any lingering concerns. “A lot of people don’t know that their complaints are linked with the ICU visit,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

Timothy G. Buchman, MD, professor of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta, who moderated the session, wondered why the ICU seems to be an inflection point for developing new chronic conditions. Could it simply be because patients are sicker to begin with and have reached an inflection point of their illness, or could the treatments in ICU be contributing to or exposing those conditions? Ms. van Beusekom believed it was likely a combination of factors, and she referred to data she had not presented showing that even control patients who had been to the hospital (though not the ICU) during the study period were at lower risk of new chronic conditions than ICU patients.

Ms. van Beusekom’s group plans to investigate ICU-related variables that might be associated with risk of chronic conditions.

The study was not funded. Ms. van Beusekom had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: van Beusekom I et al. CCC48, Abstract Crit Care Med. 2019;47:324-30.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

Commentary: Should AVFs be ligated after kidney transplant?

Hemodynamic complications of arteriovenous (AV) access are uncommon but can be potentially life threatening. Fistulas and grafts can cause a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and secondary increase in cardiac output in patients who may already have myocardial dysfunction secondary to their end-stage renal disease.1 This increased cardiac output is usually insignificant but in rare cases can result in clinically significant cardiac failure. Patients with high-output fistulas with volume flow greater than 2 L/min may be at increased risk of heart failure but volume flow less than 2 L/min does not preclude this complication.2

In patients with AV access–related heart failure, optimal medical management and reduction of fistula flow or ligation of the dialysis access should be considered. If continued hemodialysis is necessary, loss of a functioning dialysis access is problematic and difficult management decisions must be made. Following successful renal transplantation, ligation of vascular access in the presence of symptomatic heart failure may represent a straightforward decision. Nonetheless, there is no clear consensus of how to manage patent fistulas or grafts in patients following renal transplantation in the absence of significant cardiac symptoms with particular concern to the important issues of transplant survival and long-term cardiac prognosis. Yaffe and Greenstein3 recommend preservation of almost all fistulas after transplantation in the absence of significant complications such as venous hypertension, pseudoaneurysm, significant high-output cardiac failure or hand ischemia. They recommend taking into account the 10-year adjusted renal transplantation graft survival rates and the relative paucity of donors, recognizing the possibility that the patient may have to return to dialysis at some point in the future. They also reference the lack of information regarding the beneficial impact of fistula ligation on cardiac morphology and function as a rationale for access preservation.

A recent presentation at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions by Michael B. Stokes, MD,4 from the department of cardiology at Royal Adelaide Hospital in Australia, suggests that cardiovascular disease is responsible for 40% of deaths among kidney transplant recipients and that left ventricular (LV) mass is strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality.

He states that, although there is no guideline consensus on the management of an AV fistula following successful renal transplantation, the fistula continues to contribute adversely to cardiac remodeling and function. The lack of previous randomized controlled trials in this area led Dr. Stokes and his colleagues to randomly assign 64 patients at least 1 year following successful kidney transplantation with stable renal function and a functioning AV fistula to either fistula ligation or no intervention. All patients underwent cardiac MRI at baseline and 6 months.

The primary endpoint of decrease in LV mass at 6 months was significant in the ligation group but not in the control group. The ligation group also had significant decrease in LV end diastolic volume, LV end systolic volume, and multiple other parameters. In addition, NT-proBNP levels and left atrial volume were significantly reduced in the ligation group when compared with the control group. Complications in the ligation group included six patients with thrombosis of their fistula vein and two infections, all of which resolved with outpatient anti-inflammatory or antimicrobial therapy.

Dr. Stokes believes that control patients in his study face “persisting and substantial deleterious cardiac remodeling” and that “further investigation would clarify the impact of AV fistula ligation on clinical outcomes following kidney transplantation.”

I believe this is important information and represents the first randomized controlled data regarding the long-term adverse cardiac effects of a patent fistula after renal transplantation. Unfortunately, information regarding baseline fistula volume flow is not provided in this abstract. As discussed earlier, patients with high-flow fistulas may be at increased risk of heart failure and hemodynamic data can be critical in establishing an algorithm for managing these challenging patients.

Ligation of a functioning and asymptomatic access in a patient with a successful renal transplant should be recommended only after informed discussion with the patient weighing the ongoing potential negative effects on cardiac function of continued access patency versus the potential need for future hemodialysis. Dr. Stokes presents interesting data that must be considered in this controversy. I believe that, in the absence of a universally applicable algorithm, the clinical decision to recommend AV fistula ligation after successful kidney transplantation should be individualized and based on ongoing assessment of cardiac and renal function and fistula complications and hemodynamics.

References

1. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1913-23.

2. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:282-7.

3. J Vasc Access 2012;13:405-8.

4. Stokes MB, et al. LBS.05 – Late Breaking Clinical Trial: Hot News in HF. Presented at American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. 2018 Nov 10-12. Chicago.

Larry A. Scher, MD, is a vascular surgeon at the Montefiore Greene Medical Arts Pavilion, New York, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

Hemodynamic complications of arteriovenous (AV) access are uncommon but can be potentially life threatening. Fistulas and grafts can cause a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and secondary increase in cardiac output in patients who may already have myocardial dysfunction secondary to their end-stage renal disease.1 This increased cardiac output is usually insignificant but in rare cases can result in clinically significant cardiac failure. Patients with high-output fistulas with volume flow greater than 2 L/min may be at increased risk of heart failure but volume flow less than 2 L/min does not preclude this complication.2

In patients with AV access–related heart failure, optimal medical management and reduction of fistula flow or ligation of the dialysis access should be considered. If continued hemodialysis is necessary, loss of a functioning dialysis access is problematic and difficult management decisions must be made. Following successful renal transplantation, ligation of vascular access in the presence of symptomatic heart failure may represent a straightforward decision. Nonetheless, there is no clear consensus of how to manage patent fistulas or grafts in patients following renal transplantation in the absence of significant cardiac symptoms with particular concern to the important issues of transplant survival and long-term cardiac prognosis. Yaffe and Greenstein3 recommend preservation of almost all fistulas after transplantation in the absence of significant complications such as venous hypertension, pseudoaneurysm, significant high-output cardiac failure or hand ischemia. They recommend taking into account the 10-year adjusted renal transplantation graft survival rates and the relative paucity of donors, recognizing the possibility that the patient may have to return to dialysis at some point in the future. They also reference the lack of information regarding the beneficial impact of fistula ligation on cardiac morphology and function as a rationale for access preservation.

A recent presentation at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions by Michael B. Stokes, MD,4 from the department of cardiology at Royal Adelaide Hospital in Australia, suggests that cardiovascular disease is responsible for 40% of deaths among kidney transplant recipients and that left ventricular (LV) mass is strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality.

He states that, although there is no guideline consensus on the management of an AV fistula following successful renal transplantation, the fistula continues to contribute adversely to cardiac remodeling and function. The lack of previous randomized controlled trials in this area led Dr. Stokes and his colleagues to randomly assign 64 patients at least 1 year following successful kidney transplantation with stable renal function and a functioning AV fistula to either fistula ligation or no intervention. All patients underwent cardiac MRI at baseline and 6 months.

The primary endpoint of decrease in LV mass at 6 months was significant in the ligation group but not in the control group. The ligation group also had significant decrease in LV end diastolic volume, LV end systolic volume, and multiple other parameters. In addition, NT-proBNP levels and left atrial volume were significantly reduced in the ligation group when compared with the control group. Complications in the ligation group included six patients with thrombosis of their fistula vein and two infections, all of which resolved with outpatient anti-inflammatory or antimicrobial therapy.

Dr. Stokes believes that control patients in his study face “persisting and substantial deleterious cardiac remodeling” and that “further investigation would clarify the impact of AV fistula ligation on clinical outcomes following kidney transplantation.”

I believe this is important information and represents the first randomized controlled data regarding the long-term adverse cardiac effects of a patent fistula after renal transplantation. Unfortunately, information regarding baseline fistula volume flow is not provided in this abstract. As discussed earlier, patients with high-flow fistulas may be at increased risk of heart failure and hemodynamic data can be critical in establishing an algorithm for managing these challenging patients.

Ligation of a functioning and asymptomatic access in a patient with a successful renal transplant should be recommended only after informed discussion with the patient weighing the ongoing potential negative effects on cardiac function of continued access patency versus the potential need for future hemodialysis. Dr. Stokes presents interesting data that must be considered in this controversy. I believe that, in the absence of a universally applicable algorithm, the clinical decision to recommend AV fistula ligation after successful kidney transplantation should be individualized and based on ongoing assessment of cardiac and renal function and fistula complications and hemodynamics.

References

1. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1913-23.

2. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:282-7.

3. J Vasc Access 2012;13:405-8.

4. Stokes MB, et al. LBS.05 – Late Breaking Clinical Trial: Hot News in HF. Presented at American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. 2018 Nov 10-12. Chicago.

Larry A. Scher, MD, is a vascular surgeon at the Montefiore Greene Medical Arts Pavilion, New York, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

Hemodynamic complications of arteriovenous (AV) access are uncommon but can be potentially life threatening. Fistulas and grafts can cause a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and secondary increase in cardiac output in patients who may already have myocardial dysfunction secondary to their end-stage renal disease.1 This increased cardiac output is usually insignificant but in rare cases can result in clinically significant cardiac failure. Patients with high-output fistulas with volume flow greater than 2 L/min may be at increased risk of heart failure but volume flow less than 2 L/min does not preclude this complication.2

In patients with AV access–related heart failure, optimal medical management and reduction of fistula flow or ligation of the dialysis access should be considered. If continued hemodialysis is necessary, loss of a functioning dialysis access is problematic and difficult management decisions must be made. Following successful renal transplantation, ligation of vascular access in the presence of symptomatic heart failure may represent a straightforward decision. Nonetheless, there is no clear consensus of how to manage patent fistulas or grafts in patients following renal transplantation in the absence of significant cardiac symptoms with particular concern to the important issues of transplant survival and long-term cardiac prognosis. Yaffe and Greenstein3 recommend preservation of almost all fistulas after transplantation in the absence of significant complications such as venous hypertension, pseudoaneurysm, significant high-output cardiac failure or hand ischemia. They recommend taking into account the 10-year adjusted renal transplantation graft survival rates and the relative paucity of donors, recognizing the possibility that the patient may have to return to dialysis at some point in the future. They also reference the lack of information regarding the beneficial impact of fistula ligation on cardiac morphology and function as a rationale for access preservation.

A recent presentation at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions by Michael B. Stokes, MD,4 from the department of cardiology at Royal Adelaide Hospital in Australia, suggests that cardiovascular disease is responsible for 40% of deaths among kidney transplant recipients and that left ventricular (LV) mass is strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality.

He states that, although there is no guideline consensus on the management of an AV fistula following successful renal transplantation, the fistula continues to contribute adversely to cardiac remodeling and function. The lack of previous randomized controlled trials in this area led Dr. Stokes and his colleagues to randomly assign 64 patients at least 1 year following successful kidney transplantation with stable renal function and a functioning AV fistula to either fistula ligation or no intervention. All patients underwent cardiac MRI at baseline and 6 months.

The primary endpoint of decrease in LV mass at 6 months was significant in the ligation group but not in the control group. The ligation group also had significant decrease in LV end diastolic volume, LV end systolic volume, and multiple other parameters. In addition, NT-proBNP levels and left atrial volume were significantly reduced in the ligation group when compared with the control group. Complications in the ligation group included six patients with thrombosis of their fistula vein and two infections, all of which resolved with outpatient anti-inflammatory or antimicrobial therapy.

Dr. Stokes believes that control patients in his study face “persisting and substantial deleterious cardiac remodeling” and that “further investigation would clarify the impact of AV fistula ligation on clinical outcomes following kidney transplantation.”

I believe this is important information and represents the first randomized controlled data regarding the long-term adverse cardiac effects of a patent fistula after renal transplantation. Unfortunately, information regarding baseline fistula volume flow is not provided in this abstract. As discussed earlier, patients with high-flow fistulas may be at increased risk of heart failure and hemodynamic data can be critical in establishing an algorithm for managing these challenging patients.

Ligation of a functioning and asymptomatic access in a patient with a successful renal transplant should be recommended only after informed discussion with the patient weighing the ongoing potential negative effects on cardiac function of continued access patency versus the potential need for future hemodialysis. Dr. Stokes presents interesting data that must be considered in this controversy. I believe that, in the absence of a universally applicable algorithm, the clinical decision to recommend AV fistula ligation after successful kidney transplantation should be individualized and based on ongoing assessment of cardiac and renal function and fistula complications and hemodynamics.

References

1. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1913-23.

2. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:282-7.

3. J Vasc Access 2012;13:405-8.

4. Stokes MB, et al. LBS.05 – Late Breaking Clinical Trial: Hot News in HF. Presented at American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. 2018 Nov 10-12. Chicago.

Larry A. Scher, MD, is a vascular surgeon at the Montefiore Greene Medical Arts Pavilion, New York, and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

No survival benefit from systematic lymphadenectomy in ovarian cancer

Lymphadenectomy in women with advanced ovarian cancer and normal lymph nodes does not appear to improve overall or progression-free survival, according to a randomized trial of 647 women with newly-diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer who were undergoing macroscopically complete resection.

The women were randomized during the resection to either undergo systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy or no lymphadenectomy. The study excluded women with obvious node involvement.

The median overall survival rates were similar between the two groups; 65.5 months in the lymphadenectomy group and 69.2 months in the no-lymphadenectomy group (HR 1.06, P = .65). There was also no significant difference between the two groups in median progression-free survival, which was 25.5 months in both.

While overall quality of life was similar between the two groups, there were some significant points of difference. Patients who underwent lymphadenectomy experienced significantly longer surgical times, and greater median blood loss, which in turn led to a higher rate of blood transfusions and higher rate of postoperative admission to intensive care.

The 60-day mortality rates were also significantly higher among the lymphadenectomy group – 3.1% vs. 0.9% (P = .049) – as was the rate of repeat laparotomies for complications (12.4% vs. 6.5%, P = .01), mainly due to bowel leakage or fistula.

While systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is often used in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, there is limited evidence in its favor from randomized clinical trials, wrote Philipp Harter, MD, of the department of gynecology and gynecologic oncology at Kliniken Essen-Mitte, Germany, and his coauthors. The report is in the New England Journal of Medicine

“In this trial, patients with advanced ovarian cancer who underwent macroscopically complete resection did not benefit from systematic lymphadenectomy,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, lymphadenectomy resulted in treatment burden and harm to patients.”

The research group also tried to account for the level of surgical experience in each of the 52 centers involved in the study, and found no difference in treatment outcomes between high-recruiting centers and low-recruiting centers. All the centers also had to demonstrate their proficiency with the lymphadenectomy procedure before participating in the study.

“Accordingly, the quality of surgery and the numbers of resected lymph nodes were higher than in previous gynecologic oncologic clinical trials analyzing this issue,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Austrian Science Fund. Six authors declared a range of fees and support from the pharmaceutical industry.

SOURCE: Harter P et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 27 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808424.

Pelvic and aortic lymph nodes can often contain microscopic ovarian cancer metastases even when they appear normal, so there has been some debate as to whether these should be systematically removed during primary surgery to eliminate this potential sanctuary for cancer cells.

While a number of previous studies have suggested a survival benefit, there were concerns about potential confounders that may have influenced those findings. This study avoids many of the criticisms leveled at previous trials; for example, by ensuring surgical center quality, by excluding women with obvious node involvement, and by conducting the lymphadenectomy only after complete macroscopic resection.

The findings are consistent with the notion that the most frequent cause of ovarian cancer-related illness and death is the inability to control intra-abdominal disease.

Dr. Eric L. Eisenhauer is from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and Dr. Dennis S. Chi is from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. These comments are adapted from their accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1900044). Both authors declared financial and other support, including advisory board positions, from private industry.

Pelvic and aortic lymph nodes can often contain microscopic ovarian cancer metastases even when they appear normal, so there has been some debate as to whether these should be systematically removed during primary surgery to eliminate this potential sanctuary for cancer cells.

While a number of previous studies have suggested a survival benefit, there were concerns about potential confounders that may have influenced those findings. This study avoids many of the criticisms leveled at previous trials; for example, by ensuring surgical center quality, by excluding women with obvious node involvement, and by conducting the lymphadenectomy only after complete macroscopic resection.

The findings are consistent with the notion that the most frequent cause of ovarian cancer-related illness and death is the inability to control intra-abdominal disease.

Dr. Eric L. Eisenhauer is from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and Dr. Dennis S. Chi is from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. These comments are adapted from their accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1900044). Both authors declared financial and other support, including advisory board positions, from private industry.

Pelvic and aortic lymph nodes can often contain microscopic ovarian cancer metastases even when they appear normal, so there has been some debate as to whether these should be systematically removed during primary surgery to eliminate this potential sanctuary for cancer cells.

While a number of previous studies have suggested a survival benefit, there were concerns about potential confounders that may have influenced those findings. This study avoids many of the criticisms leveled at previous trials; for example, by ensuring surgical center quality, by excluding women with obvious node involvement, and by conducting the lymphadenectomy only after complete macroscopic resection.

The findings are consistent with the notion that the most frequent cause of ovarian cancer-related illness and death is the inability to control intra-abdominal disease.

Dr. Eric L. Eisenhauer is from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and Dr. Dennis S. Chi is from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. These comments are adapted from their accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1900044). Both authors declared financial and other support, including advisory board positions, from private industry.

Lymphadenectomy in women with advanced ovarian cancer and normal lymph nodes does not appear to improve overall or progression-free survival, according to a randomized trial of 647 women with newly-diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer who were undergoing macroscopically complete resection.

The women were randomized during the resection to either undergo systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy or no lymphadenectomy. The study excluded women with obvious node involvement.

The median overall survival rates were similar between the two groups; 65.5 months in the lymphadenectomy group and 69.2 months in the no-lymphadenectomy group (HR 1.06, P = .65). There was also no significant difference between the two groups in median progression-free survival, which was 25.5 months in both.

While overall quality of life was similar between the two groups, there were some significant points of difference. Patients who underwent lymphadenectomy experienced significantly longer surgical times, and greater median blood loss, which in turn led to a higher rate of blood transfusions and higher rate of postoperative admission to intensive care.

The 60-day mortality rates were also significantly higher among the lymphadenectomy group – 3.1% vs. 0.9% (P = .049) – as was the rate of repeat laparotomies for complications (12.4% vs. 6.5%, P = .01), mainly due to bowel leakage or fistula.

While systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is often used in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, there is limited evidence in its favor from randomized clinical trials, wrote Philipp Harter, MD, of the department of gynecology and gynecologic oncology at Kliniken Essen-Mitte, Germany, and his coauthors. The report is in the New England Journal of Medicine

“In this trial, patients with advanced ovarian cancer who underwent macroscopically complete resection did not benefit from systematic lymphadenectomy,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, lymphadenectomy resulted in treatment burden and harm to patients.”

The research group also tried to account for the level of surgical experience in each of the 52 centers involved in the study, and found no difference in treatment outcomes between high-recruiting centers and low-recruiting centers. All the centers also had to demonstrate their proficiency with the lymphadenectomy procedure before participating in the study.

“Accordingly, the quality of surgery and the numbers of resected lymph nodes were higher than in previous gynecologic oncologic clinical trials analyzing this issue,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Austrian Science Fund. Six authors declared a range of fees and support from the pharmaceutical industry.

SOURCE: Harter P et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 27 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808424.

Lymphadenectomy in women with advanced ovarian cancer and normal lymph nodes does not appear to improve overall or progression-free survival, according to a randomized trial of 647 women with newly-diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer who were undergoing macroscopically complete resection.

The women were randomized during the resection to either undergo systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy or no lymphadenectomy. The study excluded women with obvious node involvement.

The median overall survival rates were similar between the two groups; 65.5 months in the lymphadenectomy group and 69.2 months in the no-lymphadenectomy group (HR 1.06, P = .65). There was also no significant difference between the two groups in median progression-free survival, which was 25.5 months in both.

While overall quality of life was similar between the two groups, there were some significant points of difference. Patients who underwent lymphadenectomy experienced significantly longer surgical times, and greater median blood loss, which in turn led to a higher rate of blood transfusions and higher rate of postoperative admission to intensive care.

The 60-day mortality rates were also significantly higher among the lymphadenectomy group – 3.1% vs. 0.9% (P = .049) – as was the rate of repeat laparotomies for complications (12.4% vs. 6.5%, P = .01), mainly due to bowel leakage or fistula.

While systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is often used in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, there is limited evidence in its favor from randomized clinical trials, wrote Philipp Harter, MD, of the department of gynecology and gynecologic oncology at Kliniken Essen-Mitte, Germany, and his coauthors. The report is in the New England Journal of Medicine

“In this trial, patients with advanced ovarian cancer who underwent macroscopically complete resection did not benefit from systematic lymphadenectomy,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, lymphadenectomy resulted in treatment burden and harm to patients.”

The research group also tried to account for the level of surgical experience in each of the 52 centers involved in the study, and found no difference in treatment outcomes between high-recruiting centers and low-recruiting centers. All the centers also had to demonstrate their proficiency with the lymphadenectomy procedure before participating in the study.

“Accordingly, the quality of surgery and the numbers of resected lymph nodes were higher than in previous gynecologic oncologic clinical trials analyzing this issue,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Austrian Science Fund. Six authors declared a range of fees and support from the pharmaceutical industry.

SOURCE: Harter P et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 27 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808424.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: No survival benefits are associated with systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in advanced ovarian cancer.

Major finding: Median overall and progression-free survival did not improve after systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in advanced ovarian cancer.

Study details: Randomized controlled trial of 647 women with newly-diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Austrian Science Fund. Six authors declared a range of fees and support from the pharmaceutical industry.

Source: Harter P et al. N Eng J Med. 2019 Feb 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808424.

Stroke thrombolysis looks safe 31+ days after prior stroke

HONOLULU – , based on a review of more than 40,000 U.S. stroke patients.

Current U.S. stroke management guidelines say that thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; alteplase; Activase) is contraindicated for index stroke patients who had a prior stroke within the previous 3 months (Stroke. 2018 Mar;49[3]:e46-99). But analysis of 293 U.S. patients who received thrombolytic treatment for an index acute ischemic stroke despite having had a recent, prior stroke showed no increased risk for adverse outcomes when the prior stroke occurred more than 30 days before, Shreyansh Shah, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“The risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage [ICH] after thrombolysis was highest among those with a history of prior ischemic stroke within the past 14 days,” said Dr. Shah, a neurologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

“Even after many adjustments we still saw a high risk of symptomatic ICH within the first 2 weeks, suggesting that these patients are at especially high risk” from treatment with tissue plasminogen activator for the index stroke. These findings “are very important because I don’t see a randomized trial happening to test the hypothesis,” Dr. Shah said in an interview.

He also suggested that prior treatment with tPA was not an important factor, just the occurrence of a recent, prior ischemic stoke that left blood vessels in the affected brain region “friable and at high risk for hemorrhage,” he said.

His study used data from 40,396 patients with an acute ischemic stroke who presented at and received treatment with tPA at any of 1,522 hospitals that participated in the Get With the Guidelines-Stroke program during 2009-2015. The analysis focused on 30,655 of these patients with no prior stroke history who served as the controls, and 293 who had a prior ischemic stroke within the preceding 90 days. These 293 patients further broke into 43 who received thrombolysis within 14 days of their prior stroke, 47 who had the treatment 15-30 days after their prior stroke, and 203 who underwent thrombolysis 31-90 days after their prior stroke. Patients ages’ in both the no-stroke history and recent-stroke subgroups each averaged 80 years.

A comparison between all 293 patients who had a prior stroke within 90 days and the controls showed no statistically significant difference in the rate of symptomatic ICH: 5% among those with no stroke history and 8% in those with a recent stroke. There was also no significant difference in the rate of in-hospital mortality, occurring in 9% of those without a prior stroke, compared with 13% of those with a recent prior stroke. But the patients with no stroke history fared better by other measures, with a significantly lower rate of in-hospital death or discharge to a hospice, and also a significantly higher rate of 0-1 scores on the modified Rankin Scale, compared with patients with a history of prior stroke.

A more granular analysis of the timing of the prior stroke showed that most of risk from thrombolysis clustered in patients with a very recent prior stroke. The 43 patients with a prior stroke within the preceding 14 days had a symptomatic ICH rate of 16% after thrombolysis, 3.7-fold higher than the control patients in an adjusted analysis. Once the patients with a prior stroke within the past 14 days were pulled out, the remaining patients with prior strokes 15-30 days before as well as those with a prior stroke 31-90 days previously had symptomatic ICH rates that were not significantly different from the controls, Dr. Shah reported.

The results also showed an increased rate of in-hospital mortality or discharge to a hospice clustered in patients treated either within 14 days or during 15-30 days after a prior stroke. In both subgroups, the rate of this outcome was about triple the control rate. In the subgroup treated with thrombolysis 31-90 days after a prior stroke, the rate of in-hospital mortality or discharge to a hospice was about the same as the controls.

“It appears that some patients could benefit from tPA; there is a potential safety signal. It allows for some discretion when using thrombolytic treatment” in patients with a recent, prior stroke, Dr. Shah suggested. “This is by far the largest analysis ever reported” for thrombolytic treatment of patients following a recent, prior stroke, noted Ying Xian, MD, PhD, a Duke neurologist and study coauthor.

But Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, another coauthor, cautioned against immediately applying this finding to practice. “The findings of Dr. Shah’s study suggest that selected patients with prior stroke within a 14- to 90-day window may be considered for tPA treatment. However, further study is warranted given the relatively small number of patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Dr. Shah and Dr. Xian had no disclosures. Dr. Fonarow had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Shah S et al. Stroke. 2019 Feb;50(Suppl_1): Abstract 35.

HONOLULU – , based on a review of more than 40,000 U.S. stroke patients.

Current U.S. stroke management guidelines say that thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; alteplase; Activase) is contraindicated for index stroke patients who had a prior stroke within the previous 3 months (Stroke. 2018 Mar;49[3]:e46-99). But analysis of 293 U.S. patients who received thrombolytic treatment for an index acute ischemic stroke despite having had a recent, prior stroke showed no increased risk for adverse outcomes when the prior stroke occurred more than 30 days before, Shreyansh Shah, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“The risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage [ICH] after thrombolysis was highest among those with a history of prior ischemic stroke within the past 14 days,” said Dr. Shah, a neurologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

“Even after many adjustments we still saw a high risk of symptomatic ICH within the first 2 weeks, suggesting that these patients are at especially high risk” from treatment with tissue plasminogen activator for the index stroke. These findings “are very important because I don’t see a randomized trial happening to test the hypothesis,” Dr. Shah said in an interview.

He also suggested that prior treatment with tPA was not an important factor, just the occurrence of a recent, prior ischemic stoke that left blood vessels in the affected brain region “friable and at high risk for hemorrhage,” he said.

His study used data from 40,396 patients with an acute ischemic stroke who presented at and received treatment with tPA at any of 1,522 hospitals that participated in the Get With the Guidelines-Stroke program during 2009-2015. The analysis focused on 30,655 of these patients with no prior stroke history who served as the controls, and 293 who had a prior ischemic stroke within the preceding 90 days. These 293 patients further broke into 43 who received thrombolysis within 14 days of their prior stroke, 47 who had the treatment 15-30 days after their prior stroke, and 203 who underwent thrombolysis 31-90 days after their prior stroke. Patients ages’ in both the no-stroke history and recent-stroke subgroups each averaged 80 years.

A comparison between all 293 patients who had a prior stroke within 90 days and the controls showed no statistically significant difference in the rate of symptomatic ICH: 5% among those with no stroke history and 8% in those with a recent stroke. There was also no significant difference in the rate of in-hospital mortality, occurring in 9% of those without a prior stroke, compared with 13% of those with a recent prior stroke. But the patients with no stroke history fared better by other measures, with a significantly lower rate of in-hospital death or discharge to a hospice, and also a significantly higher rate of 0-1 scores on the modified Rankin Scale, compared with patients with a history of prior stroke.

A more granular analysis of the timing of the prior stroke showed that most of risk from thrombolysis clustered in patients with a very recent prior stroke. The 43 patients with a prior stroke within the preceding 14 days had a symptomatic ICH rate of 16% after thrombolysis, 3.7-fold higher than the control patients in an adjusted analysis. Once the patients with a prior stroke within the past 14 days were pulled out, the remaining patients with prior strokes 15-30 days before as well as those with a prior stroke 31-90 days previously had symptomatic ICH rates that were not significantly different from the controls, Dr. Shah reported.

The results also showed an increased rate of in-hospital mortality or discharge to a hospice clustered in patients treated either within 14 days or during 15-30 days after a prior stroke. In both subgroups, the rate of this outcome was about triple the control rate. In the subgroup treated with thrombolysis 31-90 days after a prior stroke, the rate of in-hospital mortality or discharge to a hospice was about the same as the controls.

“It appears that some patients could benefit from tPA; there is a potential safety signal. It allows for some discretion when using thrombolytic treatment” in patients with a recent, prior stroke, Dr. Shah suggested. “This is by far the largest analysis ever reported” for thrombolytic treatment of patients following a recent, prior stroke, noted Ying Xian, MD, PhD, a Duke neurologist and study coauthor.

But Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, another coauthor, cautioned against immediately applying this finding to practice. “The findings of Dr. Shah’s study suggest that selected patients with prior stroke within a 14- to 90-day window may be considered for tPA treatment. However, further study is warranted given the relatively small number of patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Dr. Shah and Dr. Xian had no disclosures. Dr. Fonarow had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Shah S et al. Stroke. 2019 Feb;50(Suppl_1): Abstract 35.

HONOLULU – , based on a review of more than 40,000 U.S. stroke patients.

Current U.S. stroke management guidelines say that thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; alteplase; Activase) is contraindicated for index stroke patients who had a prior stroke within the previous 3 months (Stroke. 2018 Mar;49[3]:e46-99). But analysis of 293 U.S. patients who received thrombolytic treatment for an index acute ischemic stroke despite having had a recent, prior stroke showed no increased risk for adverse outcomes when the prior stroke occurred more than 30 days before, Shreyansh Shah, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“The risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage [ICH] after thrombolysis was highest among those with a history of prior ischemic stroke within the past 14 days,” said Dr. Shah, a neurologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

“Even after many adjustments we still saw a high risk of symptomatic ICH within the first 2 weeks, suggesting that these patients are at especially high risk” from treatment with tissue plasminogen activator for the index stroke. These findings “are very important because I don’t see a randomized trial happening to test the hypothesis,” Dr. Shah said in an interview.

He also suggested that prior treatment with tPA was not an important factor, just the occurrence of a recent, prior ischemic stoke that left blood vessels in the affected brain region “friable and at high risk for hemorrhage,” he said.

His study used data from 40,396 patients with an acute ischemic stroke who presented at and received treatment with tPA at any of 1,522 hospitals that participated in the Get With the Guidelines-Stroke program during 2009-2015. The analysis focused on 30,655 of these patients with no prior stroke history who served as the controls, and 293 who had a prior ischemic stroke within the preceding 90 days. These 293 patients further broke into 43 who received thrombolysis within 14 days of their prior stroke, 47 who had the treatment 15-30 days after their prior stroke, and 203 who underwent thrombolysis 31-90 days after their prior stroke. Patients ages’ in both the no-stroke history and recent-stroke subgroups each averaged 80 years.

A comparison between all 293 patients who had a prior stroke within 90 days and the controls showed no statistically significant difference in the rate of symptomatic ICH: 5% among those with no stroke history and 8% in those with a recent stroke. There was also no significant difference in the rate of in-hospital mortality, occurring in 9% of those without a prior stroke, compared with 13% of those with a recent prior stroke. But the patients with no stroke history fared better by other measures, with a significantly lower rate of in-hospital death or discharge to a hospice, and also a significantly higher rate of 0-1 scores on the modified Rankin Scale, compared with patients with a history of prior stroke.

A more granular analysis of the timing of the prior stroke showed that most of risk from thrombolysis clustered in patients with a very recent prior stroke. The 43 patients with a prior stroke within the preceding 14 days had a symptomatic ICH rate of 16% after thrombolysis, 3.7-fold higher than the control patients in an adjusted analysis. Once the patients with a prior stroke within the past 14 days were pulled out, the remaining patients with prior strokes 15-30 days before as well as those with a prior stroke 31-90 days previously had symptomatic ICH rates that were not significantly different from the controls, Dr. Shah reported.

The results also showed an increased rate of in-hospital mortality or discharge to a hospice clustered in patients treated either within 14 days or during 15-30 days after a prior stroke. In both subgroups, the rate of this outcome was about triple the control rate. In the subgroup treated with thrombolysis 31-90 days after a prior stroke, the rate of in-hospital mortality or discharge to a hospice was about the same as the controls.

“It appears that some patients could benefit from tPA; there is a potential safety signal. It allows for some discretion when using thrombolytic treatment” in patients with a recent, prior stroke, Dr. Shah suggested. “This is by far the largest analysis ever reported” for thrombolytic treatment of patients following a recent, prior stroke, noted Ying Xian, MD, PhD, a Duke neurologist and study coauthor.

But Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, another coauthor, cautioned against immediately applying this finding to practice. “The findings of Dr. Shah’s study suggest that selected patients with prior stroke within a 14- to 90-day window may be considered for tPA treatment. However, further study is warranted given the relatively small number of patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Dr. Shah and Dr. Xian had no disclosures. Dr. Fonarow had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Shah S et al. Stroke. 2019 Feb;50(Suppl_1): Abstract 35.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2019

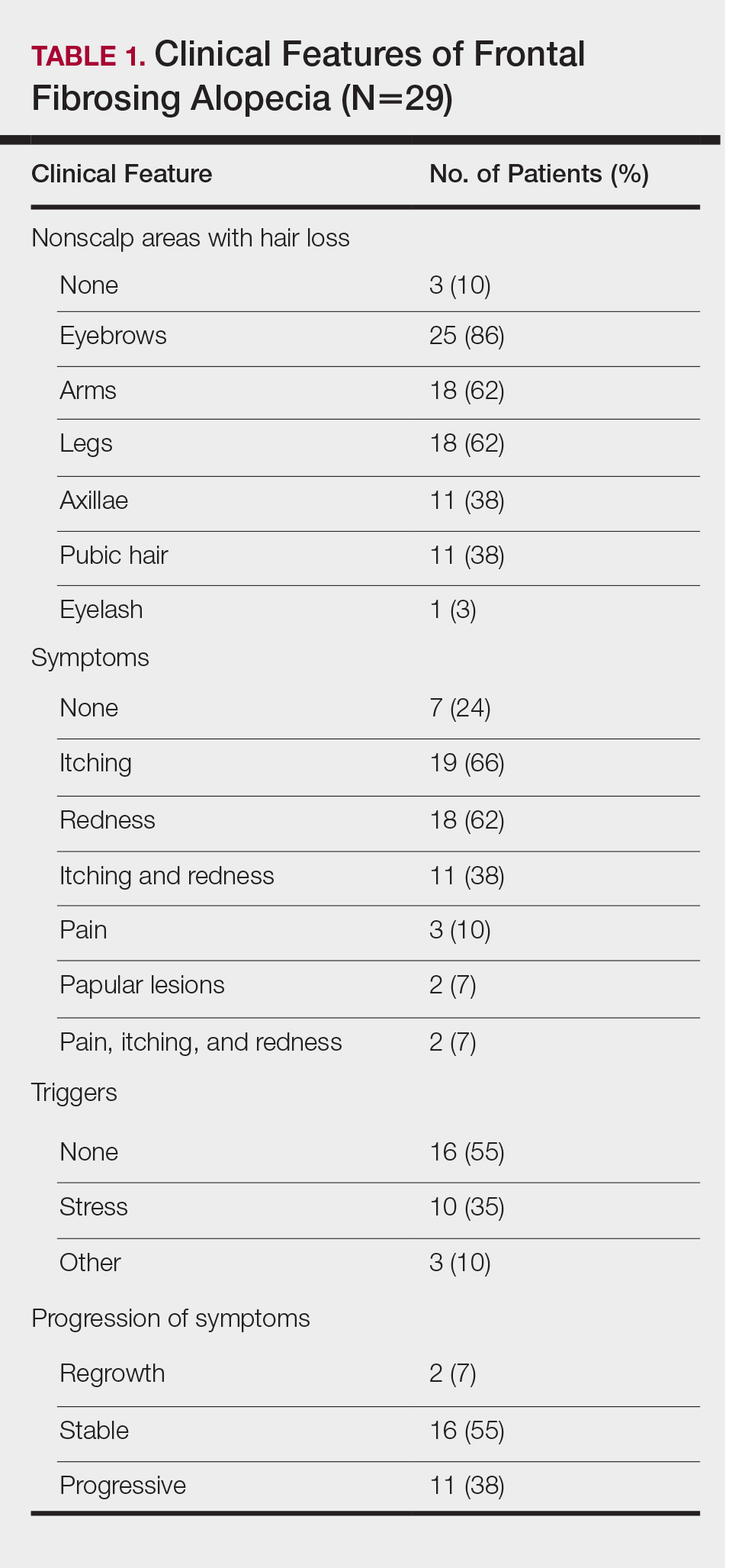

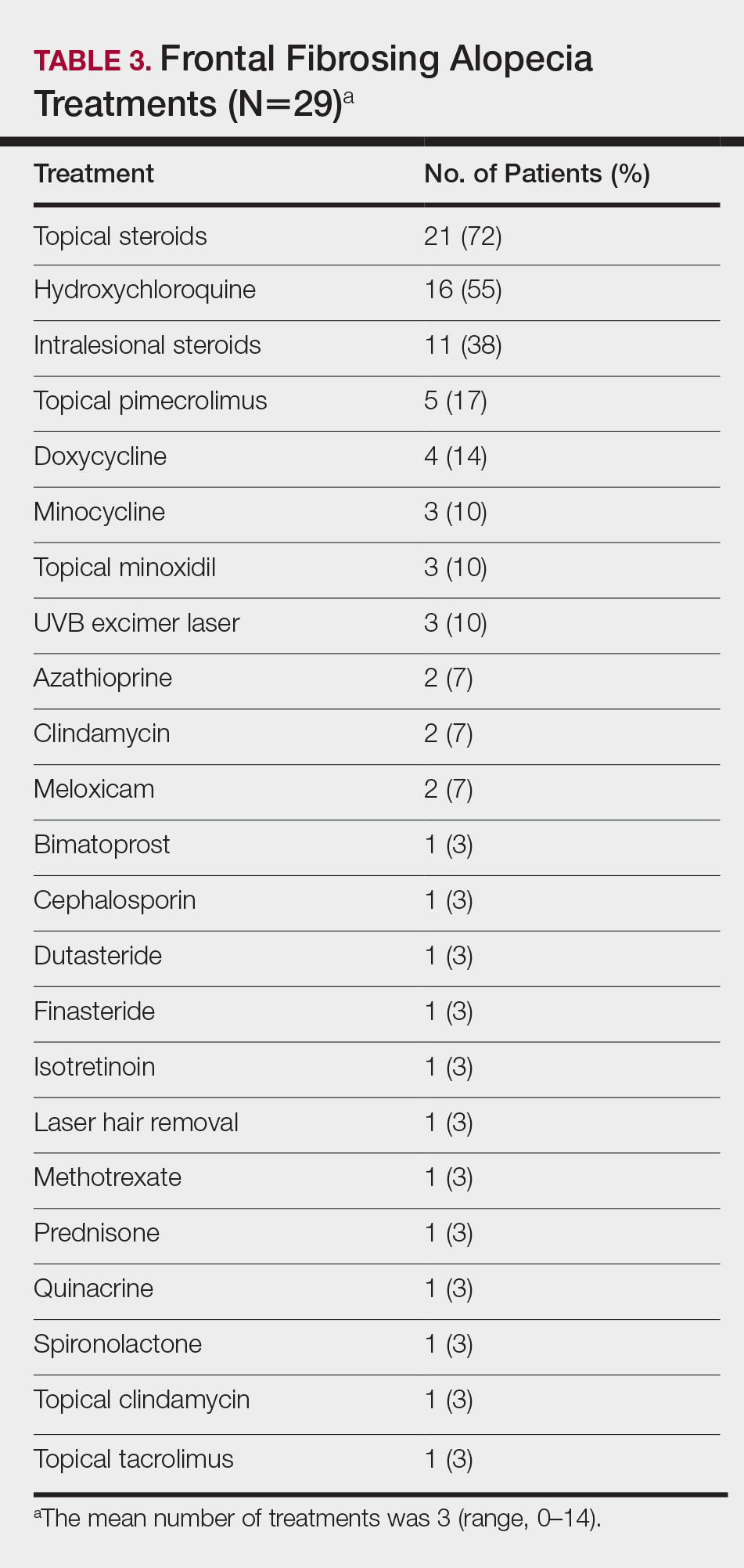

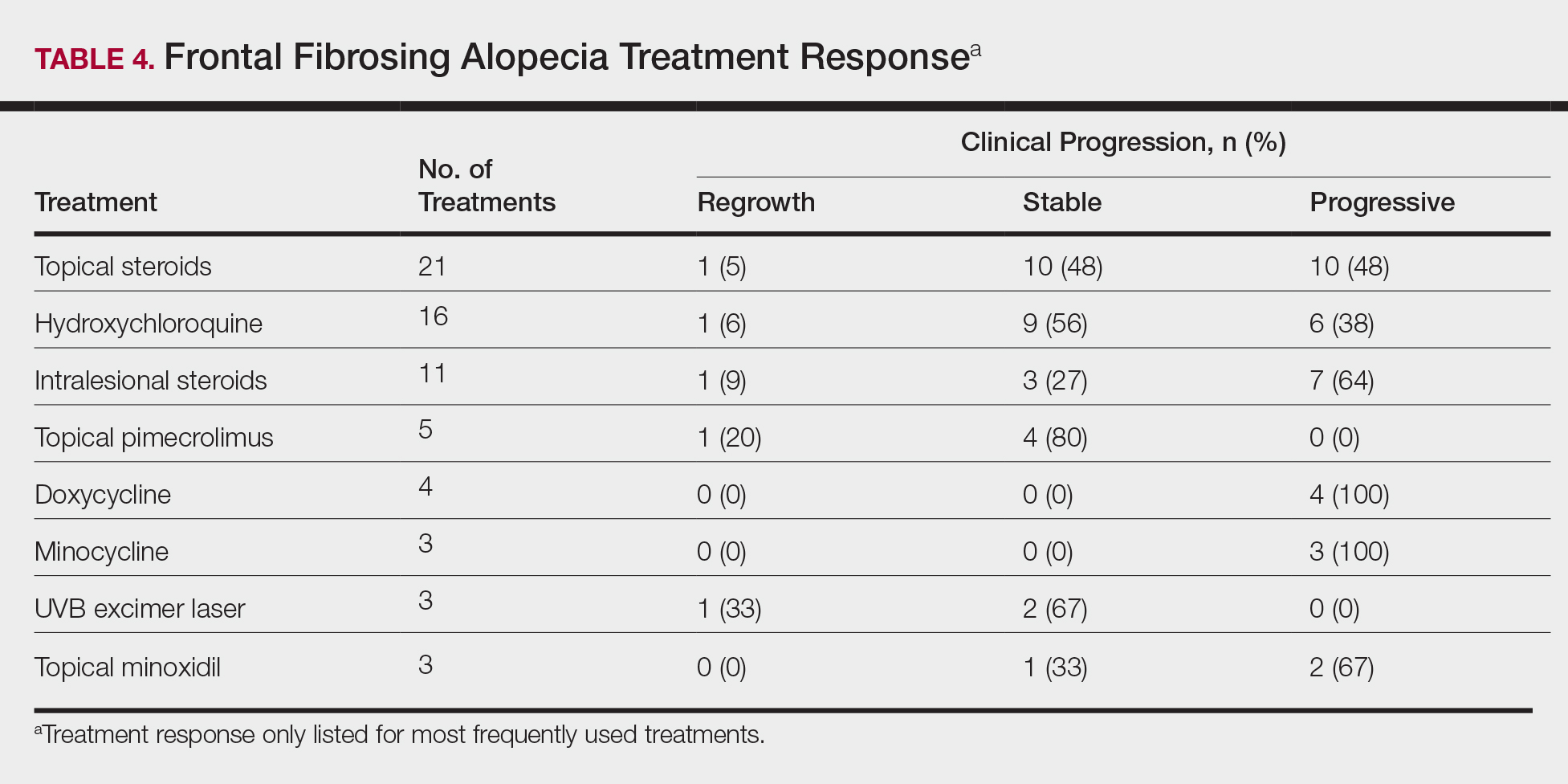

Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Demographics: A Survey of 29 Patients

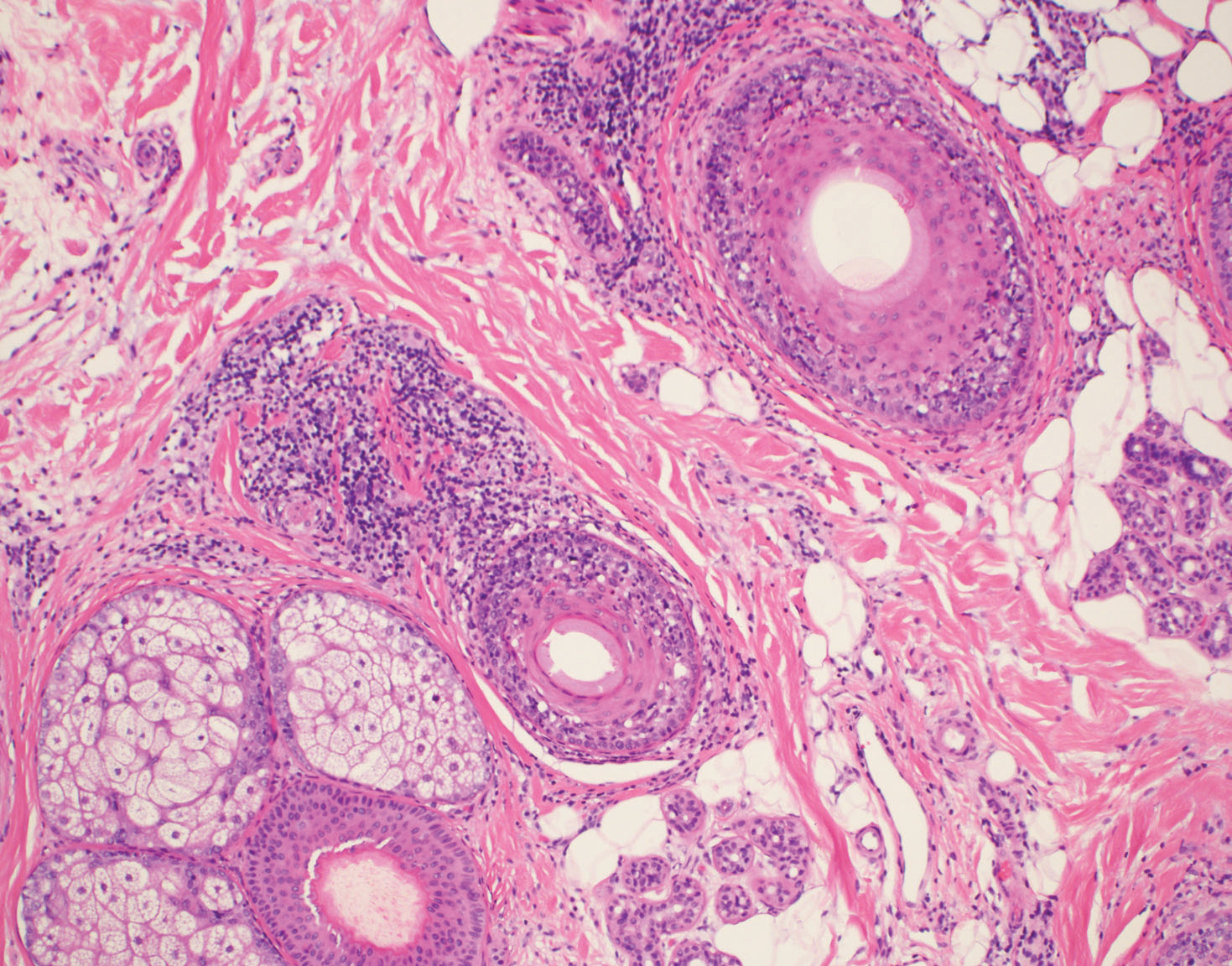

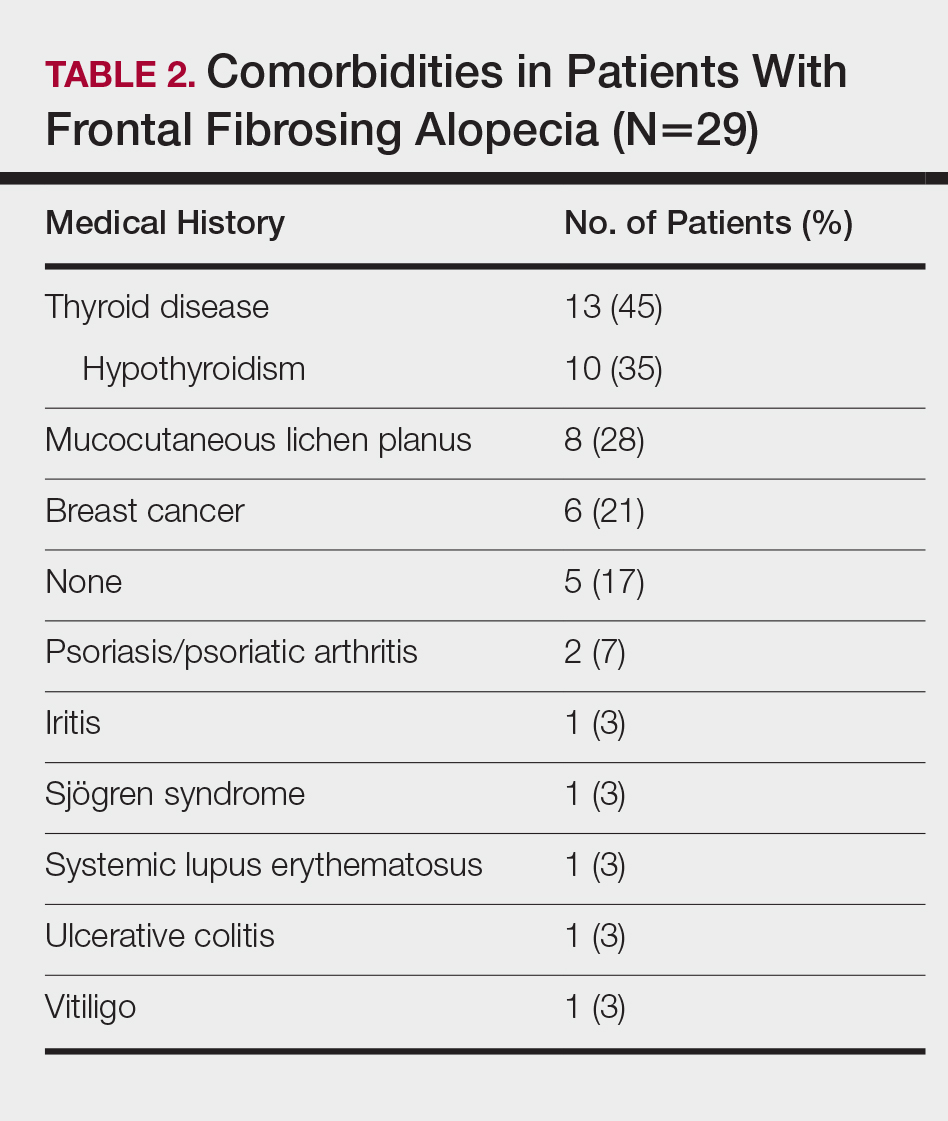

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a form of lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that presents as frontotemporal hairline recession, typically in postmenopausal women.1 The condition is considered to be a variant of lichen planopilaris (LPP) due to its similar histologic appearance.2 Loss of eyebrow1-11 and body5-11 hair also is commonly present in FFA, and histologic findings are identical to those for hair loss on the scalp,8,9 suggesting that FFA may be a form of generalized alopecia.

The pathogenesis of FFA is unknown, but several etiologies have been postulated. Some suggest that as a variant of LPP, FFA is a hair-specific autoimmune disorder characterized by a T cell–mediated immune reaction against epithelial hair follicle stem cells, leading to fibrosis and depletion of hair regeneration potential.12 In support of this theory, FFA has been associated with other autoimmune diseases including hypothyroidism,6,8,13-16 mucocutaneous lichen planus,8,15,17 vitiligo,15,18 Sjögren syndrome,19 and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus.15,20 Another hypothesis suggests that the proandrogenic state in postmenopausal women may be related to the disease process.1 This hypothesis is supported by the reported success of antiandrogen therapy with 5α-reductase inhibitors (5α-RIs) in stabilizing FFA.3-5,7 Finally, genetic16,21 and environmental factors related to smoking and socioeconomic status5 also have been postulated to be risk factors for FFA. A variety of treatments have shown varying success, including topical and intralesional corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, immunomodulators, antibiotics, and 5α-RIs.1,3-6,8,15,17,22 However, FFA is considered to be relatively difficult to treat and commonly progresses regardless of treatment before spontaneously stabilizing.2-4,6,8,10

Since its discovery in 1994,1 FFA has become increasingly prevalent, comprising 17% of new referrals for hair loss in one study (N=57).6 Although growing recognition of the condition likely plays a role in its increasing presentation, other unidentified factors may contribute to its expanding incidence. In this report, we describe the demographics, clinical features, and disease progression of 29 cases of FFA treated within our division using a series of surveys and chart reviews.

Methods

Upon receiving approval for the project from the institutional review board, we identified 29 patients who met the criteria for diagnosis of FFA through a chart review of all patients being treated for hair loss by clinics within the Washington University Division of Dermatology (St. Louis, Missouri). Diagnostic criteria for FFA included scarring alopecia in the frontotemporal distribution with associated perifollicular erythema or papules and, if performed, a scalp biopsy of the involved area of alopecia showing lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia, compatible with LPP. The diagnosis was confirmed by biopsy in 18 patients (62%), while the remainder of the diagnoses were made clinically. Most biopsy specimens were diagnosed by board-certified dermatopathologists at Washington University, with the remainder diagnosed by outside pathologists if the patient was initially diagnosed at another institution.

Patients meeting criteria for FFA were mailed a study consent form, as well as a 2-page survey to assess demographics, clinical features of hair loss, medical histories, social and family histories, and treatments utilized. After receiving consent from patients, survey results were collected and summarized. If there was any need for clarification of answers, follow-up questions were conducted via email prior to any data analysis that was performed.

For analysis of treatment response, patients were asked what treatments they had utilized and about the progression of their hair loss. Patients reporting stabilization of hair loss or hair regrowth were classified as treatment responsive. Patients who underwent multiple treatments were included in the analyses for each of those treatments. Physician records for treatment response were not correlated with patient responses due to inconsistent documentation, care received outside of our medical system, and prolonged or loss to follow-up. Physician-reported data were only used to identify qualifying patients and their biopsy results, as described above.

Results

Patient Demographic