User login

Ultrasound Monitoring of IBD May Prompt Faster Treatment Change

, according to a small retrospective analysis.

“Current disease monitoring tools have significant limitations,” said Noa Krugliak Cleveland, MD, director of the intestinal ultrasound program at the University of Chicago. “Intestinal ultrasound is an innovative technology that enables point-of-care assessment.”

Dr. Cleveland presented the findings at the October 2023 American College of Gastroenterology’s annual scientific meeting in Vancouver, Canada.

The analysis was based on 30 patients with IBD in an ongoing real-world prospective study of upadacitinib (Rinvoq, Abbvie) who were not in clinical remission at week 8. For 11 patients, routine clinical care included IUS; the other 19 patients were monitored using a conventional approach.

In the study, both groups were almost evenly split in terms of diagnosis. In the IUS group, four patients had Crohn’s disease and five had ulcerative colitis. In the conventional management group, six had Crohn’s disease and five had ulcerative colitis.

The primary endpoint was time to treatment change.

For the secondary endpoint, the researchers defined clinical remission as a Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index ≤ 2, or Harvey-Bradshaw Index ≤ 4, and by IUS as bowel wall thickness ≤ 3 mm in the colon or terminal ileum and no hyperemia by color Doppler signal.

The average time to treatment change in the IUS group was 1.1 days, compared with 16.6 days for the conventional management group, Dr. Cleveland reported.

The average time to clinical remission was 26.8 days for the IUS group, compared with 55.3 days for the conventional management group.

The delays in treatment change in the conventional management group were attributed to awaiting test results and endoscopy procedures, as well as communications among clinical team members.

Strength of this research project included its prospective data collection and the experienced sonographers who participated, Dr. Cleveland and colleagues said. Limitations included retrospective analysis, a small number of patients on a single therapy, and the potential for bias in patient selection. Studies of other therapies and a prospective trial are underway.

During the presentation, Dr. Cleveland commented about what kinds of treatment changes were made for patients in the study. They commonly involved extending the induction time, and, in some cases, patients were switched to another treatment, she said.

In an interview, Michael Dolinger, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, said more research needs to be done to show whether IUS will improve outcomes.

“They’re showing that they make more changes sooner,” he said. “Does that actually affect and improve outcomes? That’s the big question.”

Dr. Dolinger said the concept for using IUS is that it helps physicians catch disease flares earlier and respond faster with changes to the treatment plan, thus preventing the buildup of chronic bowel damage.

“That’s the concept, but that concept is actually not so proven in reality” yet, he said. “But I do believe that they’re on the right path.”

In Dr. Dolinger’s view, adding ultrasound provides a more patient-centric approach to care of people with IBD. With more traditional approaches, patients often are waiting for results of tests done outside of the visit, such as MRI.

“With ultrasound, I am walking them through the results as it’s happening in real time during the clinic visit,” Dr. Dolinger said. ”I am showing them on the screen, allowing them to ask questions. They’re telling me about their symptoms, as I’m putting the probe on where it may hurt, as I’m showing them inflammation or healing. And that changes the whole conversation.”

The study received support from the Mutchnik Family Foundation. Dr. Cleveland reported financial relationships with Bristol Myers Squibb, Neurologica, and Takeda. Her coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple drug and device makers. Dr. Dolinger said he is a consultant for Samsung’s Neurologica Corp., which makes ultrasound equipment.

, according to a small retrospective analysis.

“Current disease monitoring tools have significant limitations,” said Noa Krugliak Cleveland, MD, director of the intestinal ultrasound program at the University of Chicago. “Intestinal ultrasound is an innovative technology that enables point-of-care assessment.”

Dr. Cleveland presented the findings at the October 2023 American College of Gastroenterology’s annual scientific meeting in Vancouver, Canada.

The analysis was based on 30 patients with IBD in an ongoing real-world prospective study of upadacitinib (Rinvoq, Abbvie) who were not in clinical remission at week 8. For 11 patients, routine clinical care included IUS; the other 19 patients were monitored using a conventional approach.

In the study, both groups were almost evenly split in terms of diagnosis. In the IUS group, four patients had Crohn’s disease and five had ulcerative colitis. In the conventional management group, six had Crohn’s disease and five had ulcerative colitis.

The primary endpoint was time to treatment change.

For the secondary endpoint, the researchers defined clinical remission as a Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index ≤ 2, or Harvey-Bradshaw Index ≤ 4, and by IUS as bowel wall thickness ≤ 3 mm in the colon or terminal ileum and no hyperemia by color Doppler signal.

The average time to treatment change in the IUS group was 1.1 days, compared with 16.6 days for the conventional management group, Dr. Cleveland reported.

The average time to clinical remission was 26.8 days for the IUS group, compared with 55.3 days for the conventional management group.

The delays in treatment change in the conventional management group were attributed to awaiting test results and endoscopy procedures, as well as communications among clinical team members.

Strength of this research project included its prospective data collection and the experienced sonographers who participated, Dr. Cleveland and colleagues said. Limitations included retrospective analysis, a small number of patients on a single therapy, and the potential for bias in patient selection. Studies of other therapies and a prospective trial are underway.

During the presentation, Dr. Cleveland commented about what kinds of treatment changes were made for patients in the study. They commonly involved extending the induction time, and, in some cases, patients were switched to another treatment, she said.

In an interview, Michael Dolinger, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, said more research needs to be done to show whether IUS will improve outcomes.

“They’re showing that they make more changes sooner,” he said. “Does that actually affect and improve outcomes? That’s the big question.”

Dr. Dolinger said the concept for using IUS is that it helps physicians catch disease flares earlier and respond faster with changes to the treatment plan, thus preventing the buildup of chronic bowel damage.

“That’s the concept, but that concept is actually not so proven in reality” yet, he said. “But I do believe that they’re on the right path.”

In Dr. Dolinger’s view, adding ultrasound provides a more patient-centric approach to care of people with IBD. With more traditional approaches, patients often are waiting for results of tests done outside of the visit, such as MRI.

“With ultrasound, I am walking them through the results as it’s happening in real time during the clinic visit,” Dr. Dolinger said. ”I am showing them on the screen, allowing them to ask questions. They’re telling me about their symptoms, as I’m putting the probe on where it may hurt, as I’m showing them inflammation or healing. And that changes the whole conversation.”

The study received support from the Mutchnik Family Foundation. Dr. Cleveland reported financial relationships with Bristol Myers Squibb, Neurologica, and Takeda. Her coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple drug and device makers. Dr. Dolinger said he is a consultant for Samsung’s Neurologica Corp., which makes ultrasound equipment.

, according to a small retrospective analysis.

“Current disease monitoring tools have significant limitations,” said Noa Krugliak Cleveland, MD, director of the intestinal ultrasound program at the University of Chicago. “Intestinal ultrasound is an innovative technology that enables point-of-care assessment.”

Dr. Cleveland presented the findings at the October 2023 American College of Gastroenterology’s annual scientific meeting in Vancouver, Canada.

The analysis was based on 30 patients with IBD in an ongoing real-world prospective study of upadacitinib (Rinvoq, Abbvie) who were not in clinical remission at week 8. For 11 patients, routine clinical care included IUS; the other 19 patients were monitored using a conventional approach.

In the study, both groups were almost evenly split in terms of diagnosis. In the IUS group, four patients had Crohn’s disease and five had ulcerative colitis. In the conventional management group, six had Crohn’s disease and five had ulcerative colitis.

The primary endpoint was time to treatment change.

For the secondary endpoint, the researchers defined clinical remission as a Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index ≤ 2, or Harvey-Bradshaw Index ≤ 4, and by IUS as bowel wall thickness ≤ 3 mm in the colon or terminal ileum and no hyperemia by color Doppler signal.

The average time to treatment change in the IUS group was 1.1 days, compared with 16.6 days for the conventional management group, Dr. Cleveland reported.

The average time to clinical remission was 26.8 days for the IUS group, compared with 55.3 days for the conventional management group.

The delays in treatment change in the conventional management group were attributed to awaiting test results and endoscopy procedures, as well as communications among clinical team members.

Strength of this research project included its prospective data collection and the experienced sonographers who participated, Dr. Cleveland and colleagues said. Limitations included retrospective analysis, a small number of patients on a single therapy, and the potential for bias in patient selection. Studies of other therapies and a prospective trial are underway.

During the presentation, Dr. Cleveland commented about what kinds of treatment changes were made for patients in the study. They commonly involved extending the induction time, and, in some cases, patients were switched to another treatment, she said.

In an interview, Michael Dolinger, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, said more research needs to be done to show whether IUS will improve outcomes.

“They’re showing that they make more changes sooner,” he said. “Does that actually affect and improve outcomes? That’s the big question.”

Dr. Dolinger said the concept for using IUS is that it helps physicians catch disease flares earlier and respond faster with changes to the treatment plan, thus preventing the buildup of chronic bowel damage.

“That’s the concept, but that concept is actually not so proven in reality” yet, he said. “But I do believe that they’re on the right path.”

In Dr. Dolinger’s view, adding ultrasound provides a more patient-centric approach to care of people with IBD. With more traditional approaches, patients often are waiting for results of tests done outside of the visit, such as MRI.

“With ultrasound, I am walking them through the results as it’s happening in real time during the clinic visit,” Dr. Dolinger said. ”I am showing them on the screen, allowing them to ask questions. They’re telling me about their symptoms, as I’m putting the probe on where it may hurt, as I’m showing them inflammation or healing. And that changes the whole conversation.”

The study received support from the Mutchnik Family Foundation. Dr. Cleveland reported financial relationships with Bristol Myers Squibb, Neurologica, and Takeda. Her coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple drug and device makers. Dr. Dolinger said he is a consultant for Samsung’s Neurologica Corp., which makes ultrasound equipment.

FROM ACG 2023

Association Between LDL-C and Androgenetic Alopecia Among Female Patients in a Specialty Alopecia Clinic

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss (FPHL), or androgenetic alopecia (AGA), is the most common form of alopecia worldwide and is characterized by a reduction of hair follicles spent in the anagen phase of growth as well as progressive terminal hair loss.1 It is caused by an excessive response to androgens and leads to the characteristic distribution of hair loss in both sexes. Studies have shown a notable association between AGA and markers of metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity in age- and sex-matched controls.2,3 However, research describing the relationship between AGA severity and these markers is scarce.

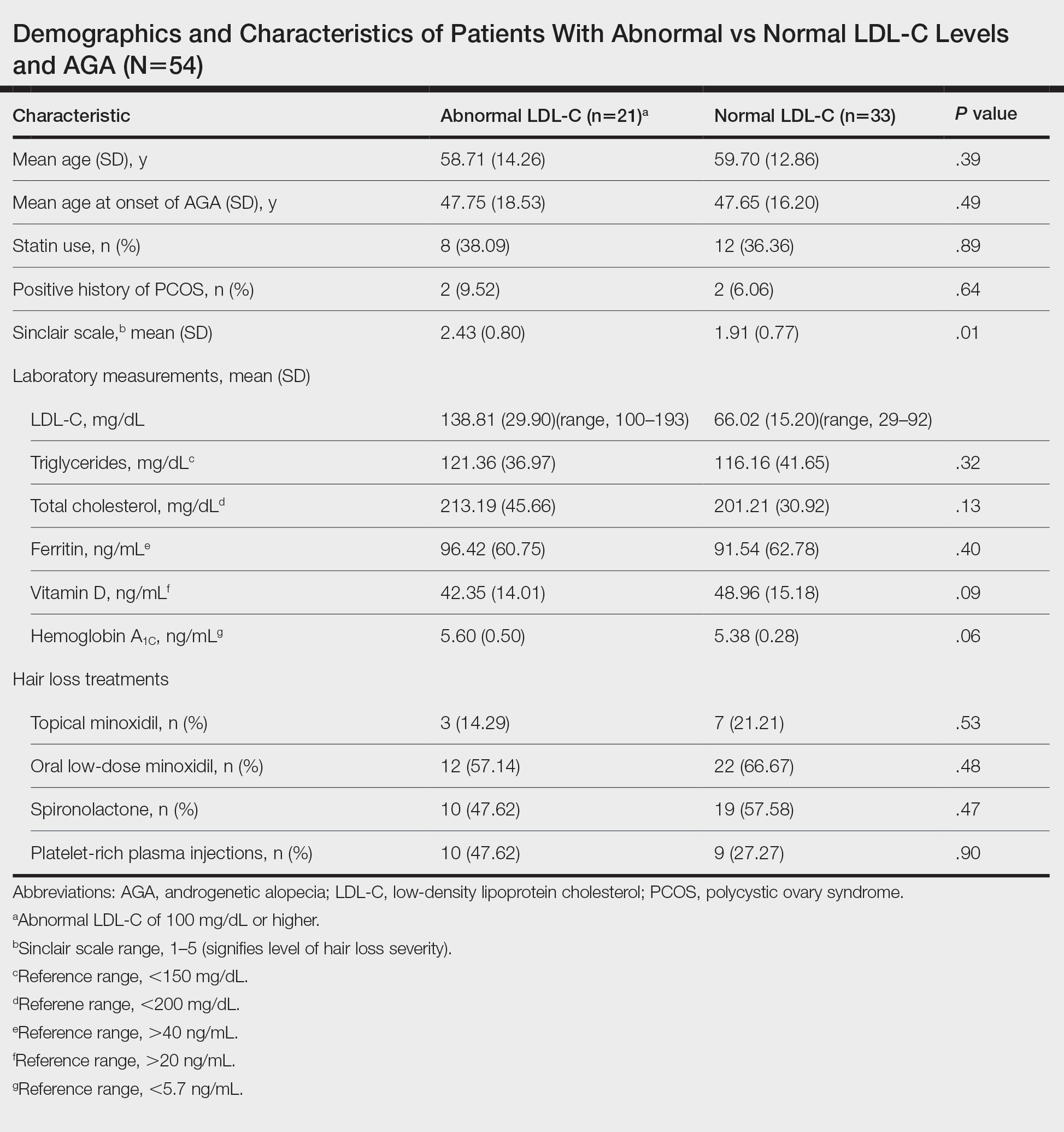

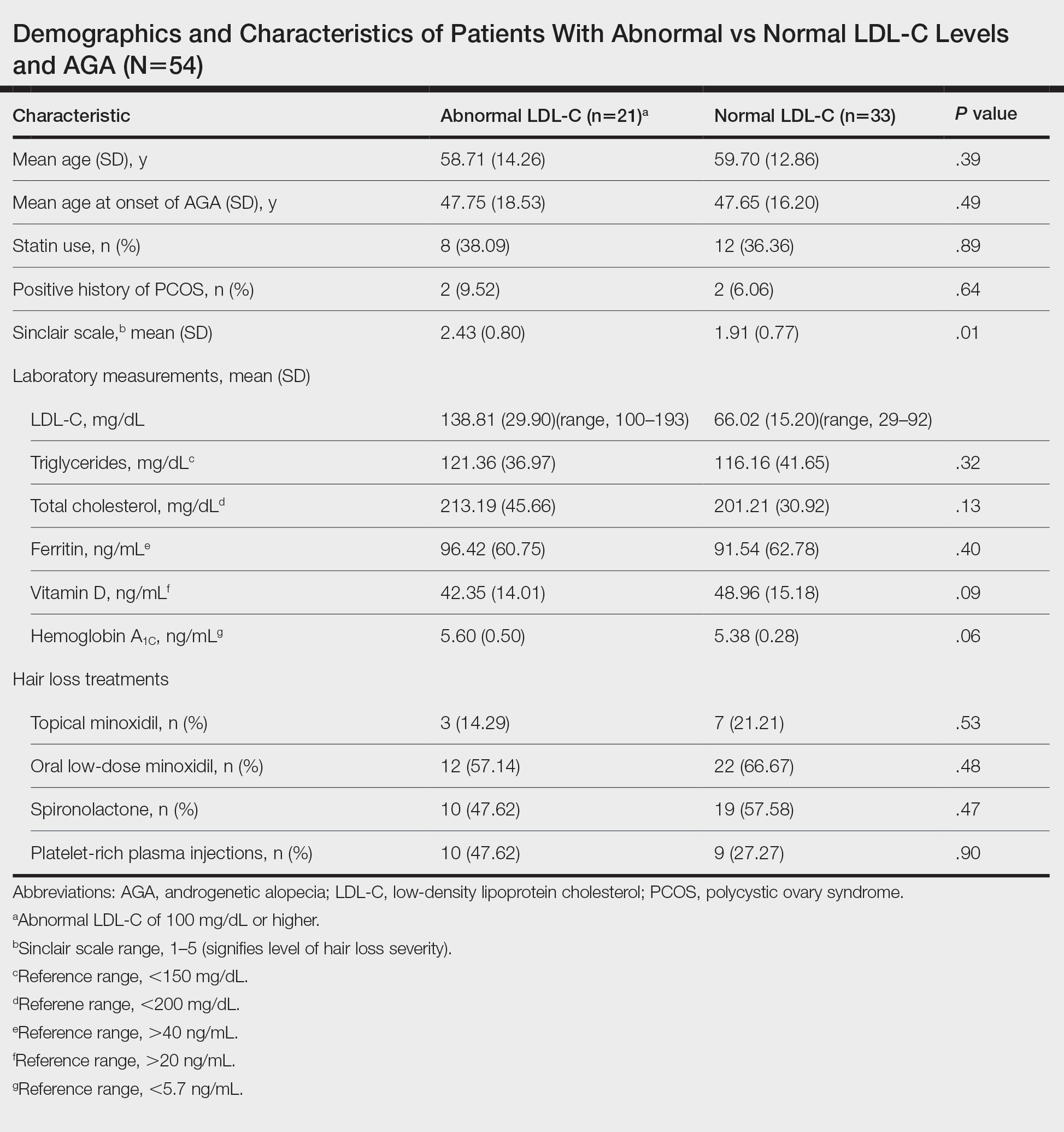

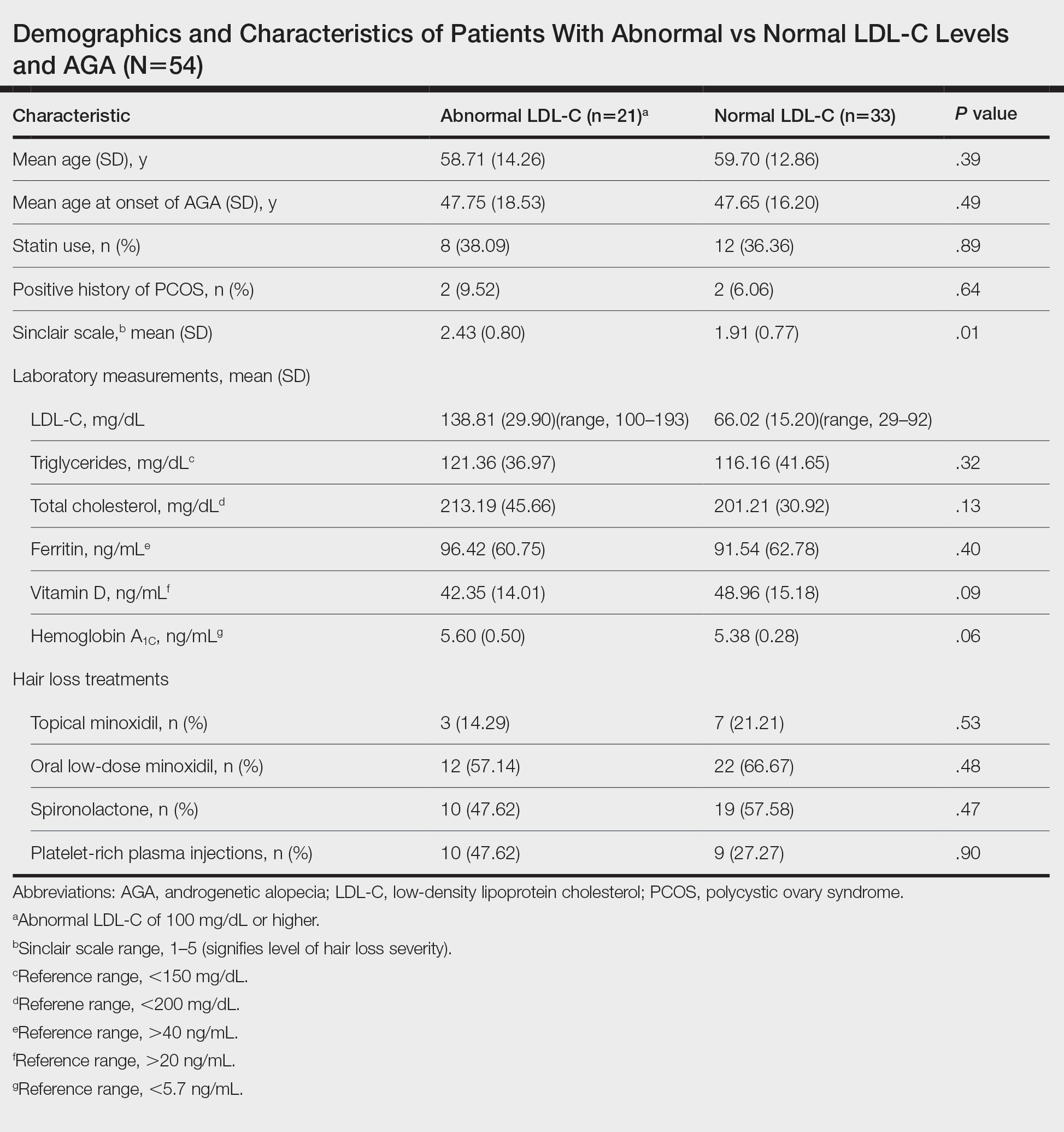

To understand the relationship between FPHL severity and abnormal cholesterol levels, we performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with FPHL at a specialty alopecia clinic from June 2022 to December 2022. Patient age and age at onset of FPHL were collected. The severity of FPHL was measured using the Sinclair scale (score range, 1–5) and unidentifiable patient photographs. Laboratory values were collected; abnormal cholesterol was defined by the American Heart Association as having a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level of 100 mg/dL or higher.4 Finally, data on medication use were noted to understand patient treatment status (Table).

We identified 54 female patients with FPHL with an average age of 59 years (range, 34–80 years). Thirty-three females (61.11%) had a normal LDL-C level and 21 (38.89%) had an abnormal level. The mean (SD) LDL-C level was 66.02 (15.20) mg/dL (range, 29–92 mg/dL) in the group with normal levels and 138.81 (29.90) mg/dL (range, 100–193 mg/dL) in the group with abnormal levels. Patients with abnormal LDL-C had significantly higher Sinclair scale scores compared to those with normal levels (2.43 vs 1.91; P=.01). There were no significant differences in patient age (58.71 vs 59.70 years; P=.39), age at onset of AGA (47.75 vs 47.65 years; P=.49), history of polycystic ovary syndrome (9.52% vs 6.06%; P=.64), or statin use (38.09% vs 36.36%; P=.89) between patients with abnormal and normal LDL-C levels, respectively. There also were no significant differences in ferritin (96.42 vs 91.54 ng/mL; P=.40), vitamin D (42.35 vs 48.96 ng/mL; P=.09), or hemoglobin A1c levels (5.60 ng/mL vs 5.38 ng/mL; P=.06)—variables that could have confounded this relationship. Triglycerides were within reference range in both groups (121.36 vs 116.16 mg/dL; P=.32), while total cholesterol was mildly elevated in both groups but not significantly different (213.19 vs 201.21 mg/dL; P=.13). Use of hair loss treatments such as topical minoxidil (14.29% vs 21.21%; P=.53), oral low-dose minoxidil (57.14% vs 66.67%; P=.48), oral spironolactone (47.62% vs 57.58%; P=.47), and platelet-rich plasma injections (47.62% vs 27.27%; P=.90) were not significantly different across both groups.

The data suggest a significant (P<.05) association between abnormal LDL-C and hair loss severity in FPHL patients. Our study was limited by its small sample size and lack of causality; however, it coincides with and reiterates the findings established in the literature. The mechanism of the association between hyperlipidemia and AGA is not well understood but is thought to stem from the homology between cholesterol and androgens. Increased cholesterol release from dermal adipocytes and subsequent absorption into hair follicle cell populations may increase hair follicle steroidogenesis, thereby accelerating the anagen-catagen transition and inducing AGA. Alternatively, impaired cholesterol homeostasis may disrupt normal hair follicle cycling by interrupting signaling pathways in follicle proliferation and differentiation.5 Adequate control and monitoring of LDL-C levels may be important, particularly in patients with more severe FPHL.

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:E9860. doi:10.5812/ijem.9860

- El Sayed MH, Abdallah MA, Aly DG, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with female pattern hair loss in women: a case-control study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1131-1137. doi:10.1111/ijd.13303

- Kim MW, Shin IS, Yoon HS, et al. Lipid profile in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:942-951. doi:10.1111/jdv.14000

- Birtcher KK, Ballantyne CM. Cardiology patient page. measurement of cholesterol: a patient perspective. Circulation. 2004;110:E296-E297. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000141564.89465.4E

- Palmer MA, Blakeborough L, Harries M, et al. Cholesterol homeostasis: links to hair follicle biology and hair disorders. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:299-311. doi:10.1111/exd.13993

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss (FPHL), or androgenetic alopecia (AGA), is the most common form of alopecia worldwide and is characterized by a reduction of hair follicles spent in the anagen phase of growth as well as progressive terminal hair loss.1 It is caused by an excessive response to androgens and leads to the characteristic distribution of hair loss in both sexes. Studies have shown a notable association between AGA and markers of metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity in age- and sex-matched controls.2,3 However, research describing the relationship between AGA severity and these markers is scarce.

To understand the relationship between FPHL severity and abnormal cholesterol levels, we performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with FPHL at a specialty alopecia clinic from June 2022 to December 2022. Patient age and age at onset of FPHL were collected. The severity of FPHL was measured using the Sinclair scale (score range, 1–5) and unidentifiable patient photographs. Laboratory values were collected; abnormal cholesterol was defined by the American Heart Association as having a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level of 100 mg/dL or higher.4 Finally, data on medication use were noted to understand patient treatment status (Table).

We identified 54 female patients with FPHL with an average age of 59 years (range, 34–80 years). Thirty-three females (61.11%) had a normal LDL-C level and 21 (38.89%) had an abnormal level. The mean (SD) LDL-C level was 66.02 (15.20) mg/dL (range, 29–92 mg/dL) in the group with normal levels and 138.81 (29.90) mg/dL (range, 100–193 mg/dL) in the group with abnormal levels. Patients with abnormal LDL-C had significantly higher Sinclair scale scores compared to those with normal levels (2.43 vs 1.91; P=.01). There were no significant differences in patient age (58.71 vs 59.70 years; P=.39), age at onset of AGA (47.75 vs 47.65 years; P=.49), history of polycystic ovary syndrome (9.52% vs 6.06%; P=.64), or statin use (38.09% vs 36.36%; P=.89) between patients with abnormal and normal LDL-C levels, respectively. There also were no significant differences in ferritin (96.42 vs 91.54 ng/mL; P=.40), vitamin D (42.35 vs 48.96 ng/mL; P=.09), or hemoglobin A1c levels (5.60 ng/mL vs 5.38 ng/mL; P=.06)—variables that could have confounded this relationship. Triglycerides were within reference range in both groups (121.36 vs 116.16 mg/dL; P=.32), while total cholesterol was mildly elevated in both groups but not significantly different (213.19 vs 201.21 mg/dL; P=.13). Use of hair loss treatments such as topical minoxidil (14.29% vs 21.21%; P=.53), oral low-dose minoxidil (57.14% vs 66.67%; P=.48), oral spironolactone (47.62% vs 57.58%; P=.47), and platelet-rich plasma injections (47.62% vs 27.27%; P=.90) were not significantly different across both groups.

The data suggest a significant (P<.05) association between abnormal LDL-C and hair loss severity in FPHL patients. Our study was limited by its small sample size and lack of causality; however, it coincides with and reiterates the findings established in the literature. The mechanism of the association between hyperlipidemia and AGA is not well understood but is thought to stem from the homology between cholesterol and androgens. Increased cholesterol release from dermal adipocytes and subsequent absorption into hair follicle cell populations may increase hair follicle steroidogenesis, thereby accelerating the anagen-catagen transition and inducing AGA. Alternatively, impaired cholesterol homeostasis may disrupt normal hair follicle cycling by interrupting signaling pathways in follicle proliferation and differentiation.5 Adequate control and monitoring of LDL-C levels may be important, particularly in patients with more severe FPHL.

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss (FPHL), or androgenetic alopecia (AGA), is the most common form of alopecia worldwide and is characterized by a reduction of hair follicles spent in the anagen phase of growth as well as progressive terminal hair loss.1 It is caused by an excessive response to androgens and leads to the characteristic distribution of hair loss in both sexes. Studies have shown a notable association between AGA and markers of metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity in age- and sex-matched controls.2,3 However, research describing the relationship between AGA severity and these markers is scarce.

To understand the relationship between FPHL severity and abnormal cholesterol levels, we performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with FPHL at a specialty alopecia clinic from June 2022 to December 2022. Patient age and age at onset of FPHL were collected. The severity of FPHL was measured using the Sinclair scale (score range, 1–5) and unidentifiable patient photographs. Laboratory values were collected; abnormal cholesterol was defined by the American Heart Association as having a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level of 100 mg/dL or higher.4 Finally, data on medication use were noted to understand patient treatment status (Table).

We identified 54 female patients with FPHL with an average age of 59 years (range, 34–80 years). Thirty-three females (61.11%) had a normal LDL-C level and 21 (38.89%) had an abnormal level. The mean (SD) LDL-C level was 66.02 (15.20) mg/dL (range, 29–92 mg/dL) in the group with normal levels and 138.81 (29.90) mg/dL (range, 100–193 mg/dL) in the group with abnormal levels. Patients with abnormal LDL-C had significantly higher Sinclair scale scores compared to those with normal levels (2.43 vs 1.91; P=.01). There were no significant differences in patient age (58.71 vs 59.70 years; P=.39), age at onset of AGA (47.75 vs 47.65 years; P=.49), history of polycystic ovary syndrome (9.52% vs 6.06%; P=.64), or statin use (38.09% vs 36.36%; P=.89) between patients with abnormal and normal LDL-C levels, respectively. There also were no significant differences in ferritin (96.42 vs 91.54 ng/mL; P=.40), vitamin D (42.35 vs 48.96 ng/mL; P=.09), or hemoglobin A1c levels (5.60 ng/mL vs 5.38 ng/mL; P=.06)—variables that could have confounded this relationship. Triglycerides were within reference range in both groups (121.36 vs 116.16 mg/dL; P=.32), while total cholesterol was mildly elevated in both groups but not significantly different (213.19 vs 201.21 mg/dL; P=.13). Use of hair loss treatments such as topical minoxidil (14.29% vs 21.21%; P=.53), oral low-dose minoxidil (57.14% vs 66.67%; P=.48), oral spironolactone (47.62% vs 57.58%; P=.47), and platelet-rich plasma injections (47.62% vs 27.27%; P=.90) were not significantly different across both groups.

The data suggest a significant (P<.05) association between abnormal LDL-C and hair loss severity in FPHL patients. Our study was limited by its small sample size and lack of causality; however, it coincides with and reiterates the findings established in the literature. The mechanism of the association between hyperlipidemia and AGA is not well understood but is thought to stem from the homology between cholesterol and androgens. Increased cholesterol release from dermal adipocytes and subsequent absorption into hair follicle cell populations may increase hair follicle steroidogenesis, thereby accelerating the anagen-catagen transition and inducing AGA. Alternatively, impaired cholesterol homeostasis may disrupt normal hair follicle cycling by interrupting signaling pathways in follicle proliferation and differentiation.5 Adequate control and monitoring of LDL-C levels may be important, particularly in patients with more severe FPHL.

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:E9860. doi:10.5812/ijem.9860

- El Sayed MH, Abdallah MA, Aly DG, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with female pattern hair loss in women: a case-control study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1131-1137. doi:10.1111/ijd.13303

- Kim MW, Shin IS, Yoon HS, et al. Lipid profile in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:942-951. doi:10.1111/jdv.14000

- Birtcher KK, Ballantyne CM. Cardiology patient page. measurement of cholesterol: a patient perspective. Circulation. 2004;110:E296-E297. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000141564.89465.4E

- Palmer MA, Blakeborough L, Harries M, et al. Cholesterol homeostasis: links to hair follicle biology and hair disorders. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:299-311. doi:10.1111/exd.13993

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:E9860. doi:10.5812/ijem.9860

- El Sayed MH, Abdallah MA, Aly DG, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with female pattern hair loss in women: a case-control study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1131-1137. doi:10.1111/ijd.13303

- Kim MW, Shin IS, Yoon HS, et al. Lipid profile in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:942-951. doi:10.1111/jdv.14000

- Birtcher KK, Ballantyne CM. Cardiology patient page. measurement of cholesterol: a patient perspective. Circulation. 2004;110:E296-E297. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000141564.89465.4E

- Palmer MA, Blakeborough L, Harries M, et al. Cholesterol homeostasis: links to hair follicle biology and hair disorders. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:299-311. doi:10.1111/exd.13993

Practice Points

- Associations have been shown between hair loss and markers of bad health such as insulin resistance and high cholesterol. Research has not yet shown the relationship between hair loss severity and these markers, particularly cholesterol.

Acne and Pregnancy: A Clinical Review and Practice Pearls

Acne vulgaris, or acne, is a highly common inflammatory skin disorder affecting up to 85% of the population, and it constitutes the most commonly presenting chief concern in routine dermatology practice.1 Older teenagers and young adults are most often affected by acne.2 Although acne generally is more common in males, adult-onset acne occurs more frequently in women.2,3 Black and Hispanic women are at higher risk for acne compared to those of Asian, White, or Continental Indian descent.4 As such, acne is a common concern in all women of childbearing age.

Concerns for maternal and fetal safety are important therapeutic considerations, especially because hormonal and physiologic changes in pregnancy can lead to onset of inflammatory acne lesions, particularly during the second and third trimesters.5 Female patients younger than 25 years; with a higher body mass index, prior irregular menstruation, or polycystic ovary syndrome; or those experiencing their first pregnancy are thought to be more commonly affected.5-7 In fact, acne affects up to 43% of pregnant women, and lesions typically extend beyond the face to involve the trunk.6,8-10 Importantly, one-third of women with a history of acne experience symptom relapse after disease-free periods, while two-thirds of those with ongoing disease experience symptom deterioration during pregnancy.10 Although acne is not a life-threatening condition, it has a well-documented, detrimental impact on social, emotional, and psychological well-being, namely self-perception, social interactions, quality-of-life scores, depression, and anxiety.11

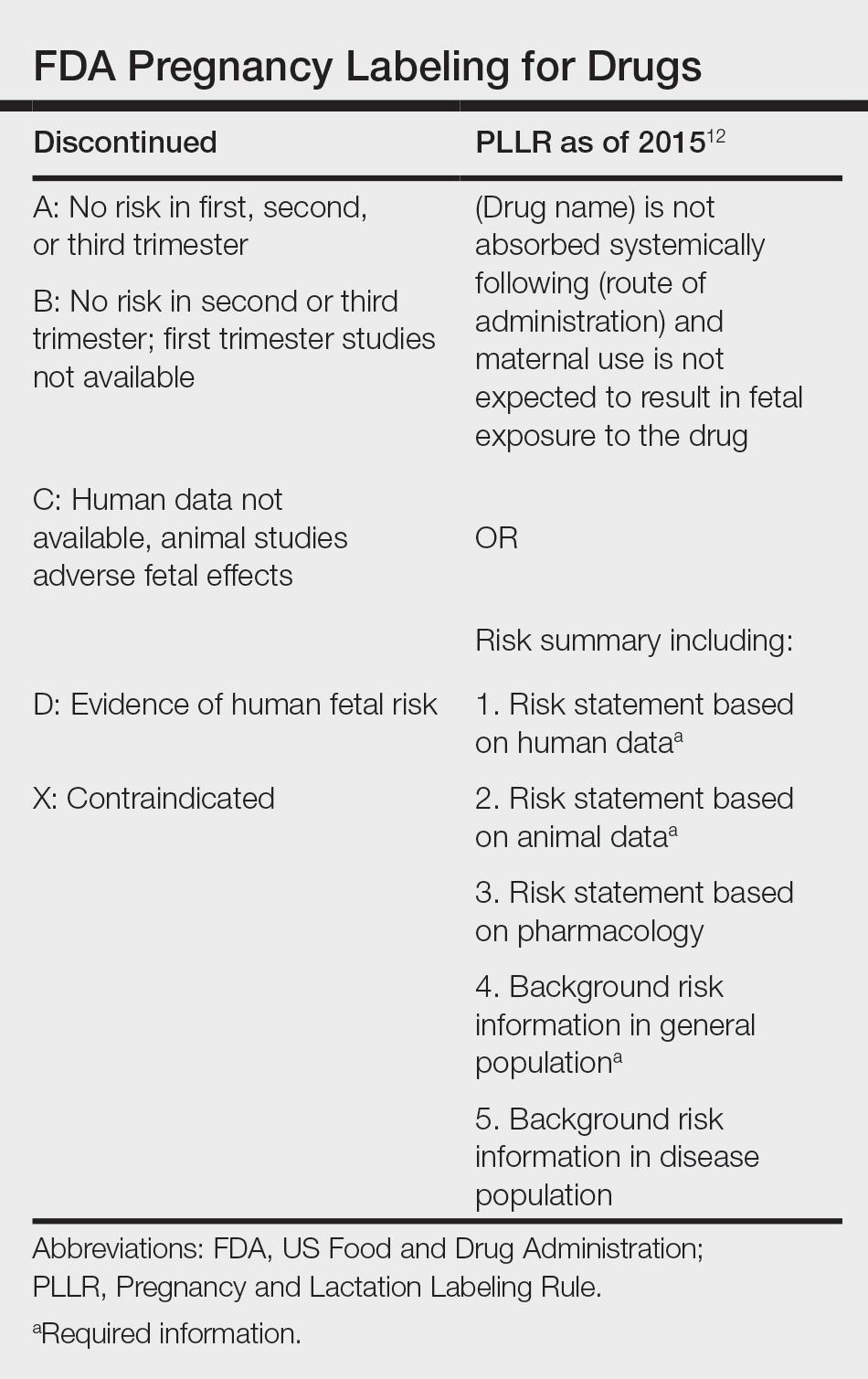

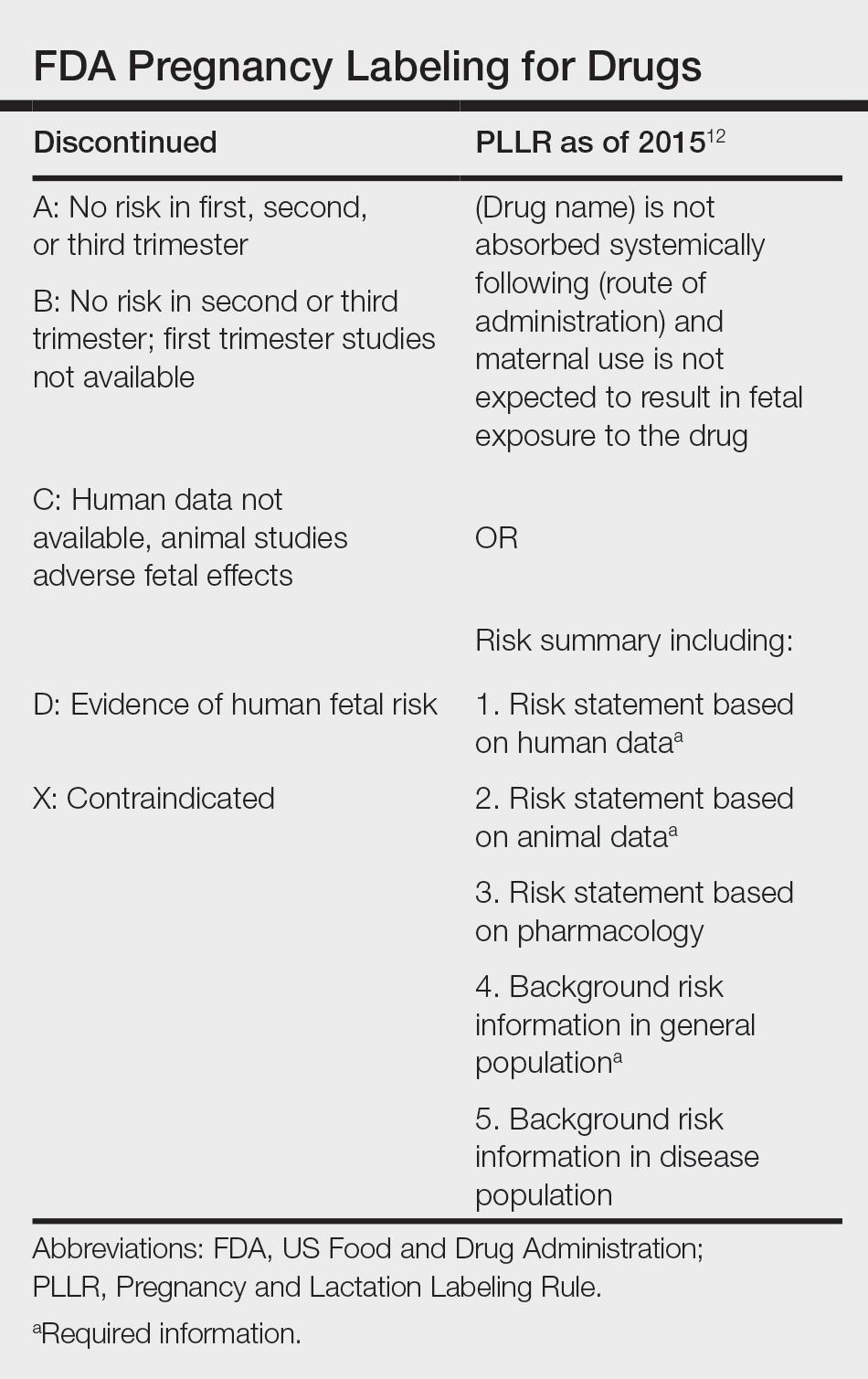

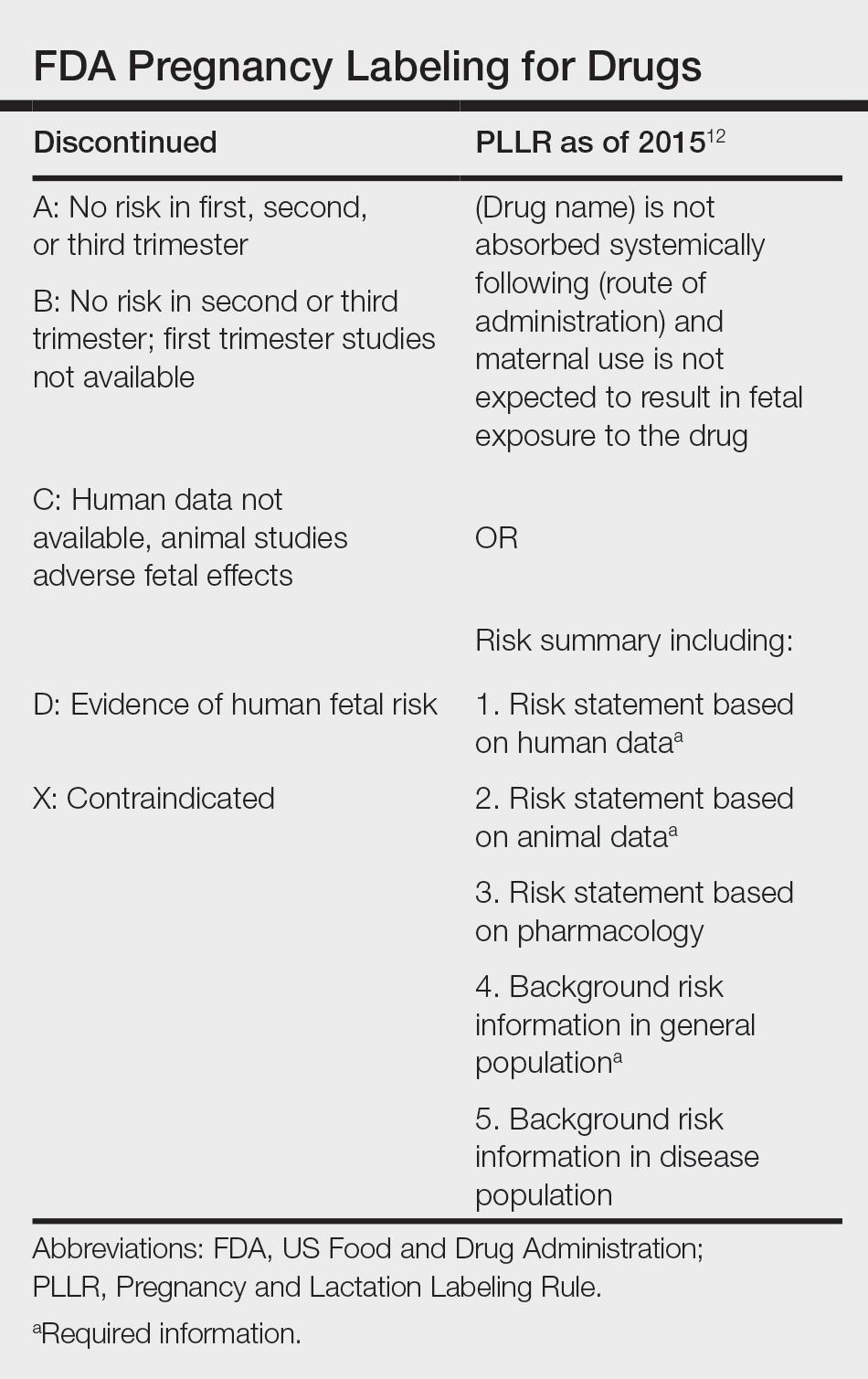

Therefore, safe and effective treatment of pregnant women is of paramount importance. Because pregnant women are not included in clinical trials, there is a paucity of medication safety data, further augmented by inefficient access to available information. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy safety categories were updated in 2015, letting go of the traditional A, B, C, D, and X categories.12 The Table reviews the current pregnancy classification system. In this narrative review, we summarize the most recent available data and recommendations on the safety and efficacy of acne treatment during pregnancy.

Topical Treatments for Acne

Benzoyl Peroxide—Benzoyl peroxide commonly is used as first-line therapy alone or in combination with other agents for the treatment of mild to moderate acne.13 It is safe for use during pregnancy.14 Although the medication is systemically absorbed, it undergoes complete metabolism to benzoic acid, a commonly used food additive.15,16 Benzoic acid has low bioavailability, as it gets rapidly metabolized by the kidneys; therefore, benzoyl peroxide is unlikely to reach clinically significant levels in the maternal circulation and consequently the fetal circulation. Additionally, it has a low risk for causing congenital malformations.17

Salicylic Acid—For mild to moderate acne, salicylic acid is a second-line agent that likely is safe for use by pregnant women at low concentrations and over limited body surface areas.14,18,19 There is minimal systemic absorption of the drug.20 Additionally, aspirin, which is broken down in the body into salicylic acid, is used in low doses for the treatment of pre-eclampsia during pregnancy.21

Dapsone—The use of dapsone gel 5% as a second-line agent has shown efficacy for mild to moderate acne.22 The oral formulation, commonly used for malaria and leprosy prophylaxis, has failed to show associated fetal toxicity or congenital anomalies.23,24 It also has been used as a first-line treatment for dermatitis herpetiformis in pregnancy.25 Although the medication likely is safe, it is better to minimize its use during the third trimester to reduce the theoretical risk for hyperbilirubinemia in the neonate.17,26-29

Azelaic Acid—Azelaic acid effectively targets noninflammatory and inflammatory acne and generally is well tolerated, harboring a good safety profile.30 Topical 20% azelaic acid has localized antibacterial and comedolytic effects and is safe for use during pregnancy.31,32

Glycolic Acid—Limited data exist on the safety of glycolic acid during pregnancy. In vitro studies have shown up to 27% systemic absorption depending on pH, concentration, and duration of application.33 Animal reproductive studies involving rats have shown fetal multisystem malformations and developmental abnormalities with oral administration of glycolic acid at doses far exceeding those used in humans.34 Although no human reproductive studies exist, topical glycolic acid is unlikely to reach the developing fetus in notable amounts, and the medication is likely safe for use.17,35

Clindamycin—Topical clindamycin phosphate is an effective and well-tolerated agent for the treatment of mild to moderate acne.36 Its systemic absorption is minimal, and it is considered safe for use during all trimesters of pregnancy.14,17,26,27,35,37

Erythromycin—Topical erythromycin is another commonly prescribed topical antibiotic used to target mild to moderate acne. However, its use recently has been associated with a decrease in efficacy secondary to the rise of antibacterial resistance in the community.38-40 Nevertheless, it remains a safe treatment for use during all trimesters of pregnancy.14,17,26,27,35,37

Topical Retinoids—Vitamin A derivatives (also known as retinoids) are the mainstay for the treatment of mild to moderate acne. Limited data exist regarding pregnancy outcomes after in utero exposure.41 A rare case report suggested topical tretinoin has been associated with fetal otocerebral anomalies.42 For tazarotene, teratogenic effects were seen in animal reproductive studies at doses exceeding maximum recommended human doses.41,43 However, a large meta-analysis failed to find a clear risk for increased congenital malformations, spontaneous abortions, stillbirth, elective termination of pregnancy, low birthweight, or prematurity following first-trimester exposure to topical retinoids.44 As the level of exposure that could lead to teratogenicity in humans is unknown, avoidance of both tretinoin and tazarotene is recommended in pregnant women.41,45 Nevertheless, women inadvertently exposed should be reassured.44

Conversely, adapalene has been associated with 1 case of anophthalmia and agenesis of the optic chiasma in a fetus following exposure until 13 weeks’ gestation.46 However, a large, open-label trial prior to the patient transitioning from adapalene to over-the-counter treatment showed that the drug harbors a large and reassuring margin of safety and no risk for teratogenicity in a maximal usage trial and Pregnancy Safety Review.47 Therefore, adapalene gel 0.1% is a safe and effective medication for the treatment of acne in a nonprescription environment and does not pose harm to the fetus.

Clascoterone—Clascoterone is a novel topical antiandrogenic drug approved for the treatment of hormonal and inflammatory moderate to severe acne.48-51 Human reproductive data are limited to 1 case of pregnancy that occurred during phase 3 trial investigations, and no adverse outcomes were reported.51 Minimal systemic absorption follows topical use.52 Nonetheless, dose-independent malformations were reported in animal reproductive studies.53 As such, it remains better to avoid the use of clascoterone during pregnancy pending further safety data.

Minocycline Foam—Minocycline foam 4% is approved to treat inflammatory lesions of nonnodular moderate to severe acne in patients 9 years and older.54 Systemic absorption is minimal, and the drug has limited bioavailability with minimal systemic accumulation in the patient’s serum.55 Given this information, it is unlikely that topical minocycline will reach notable levels in the fetal serum or harbor teratogenic effects, as seen with the oral formulation.56 However, it may be best to avoid its use during the second and third trimesters given the potential risk for tooth discoloration in the fetus.57,58

Systemic Treatments for Acne

Isotretinoin—Isotretinoin is the most effective treatment for moderate to severe acne with a well-documented potential for long-term clearance.59 Its use during pregnancy is absolutely contraindicated, as the medication is a well-known teratogen. Associated congenital malformations include numerous craniofacial defects, cardiovascular and neurologic malformations, or thymic disorders that are estimated to affect 20% to 35% of infants exposed in utero.60 Furthermore, strict contraception use during treatment is mandated for patients who can become pregnant. It is recommended to wait at least 1 month and 1 menstrual cycle after medication discontinuation before attempting to conceive.17 Pregnancy termination is recommended if conception occurs during treatment with isotretinoin.

Spironolactone—Spironolactone is an androgen-receptor antagonist commonly prescribed off label for mild to severe acne in females.61,62 Spironolactone promotes the feminization of male fetuses and should be avoided in pregnancy.63

Doxycycline/Minocycline—Tetracyclines are the most commonly prescribed oral antibiotics for moderate to severe acne.64 Although highly effective at treating acne, tetracyclines generally should be avoided in pregnancy. First-trimester use of doxycycline is not absolutely contraindicated but should be reserved for severe illness and not employed for the treatment of acne. However, accidental exposure to doxycycline has not been associated with congenital malformations.65 Nevertheless, after the 15th week of gestation, permanent tooth discoloration and bone growth inhibition in the fetus are serious and well-documented risks.14,17 Additional adverse events following in utero exposure include infantile inguinal hernia, hypospadias, and limb hypoplasia.63

Sarecycline—Sarecycline is a novel tetracycline-class antibiotic for the treatment of moderate to severe inflammatory acne. It has a narrower spectrum of activity compared to its counterparts within its class, which translates to an improved safety profile, namely when it comes to gastrointestinal tract microbiome disruption and potentially decreased likelihood of developing bacterial resistance.66 Data on human reproductive studies are limited, but it is advisable to avoid sarecycline in pregnancy, as it may cause adverse developmental effects in the fetus, such as reduced bone growth, in addition to the well-known tetracycline-associated risk for permanent discoloration of the teeth if used during the second and third trimesters.67,68

Erythromycin—Oral erythromycin targets moderate to severe inflammatory acne and is considered safe for use during pregnancy.69,70 There has been 1 study reporting an increased risk for atrial and ventricular septal defects (1.8%) and pyloric stenosis (0.2%), but these risks are still uncertain, and erythromycin is considered compatible with pregnancy.71 However, erythromycin estolate formulations should be avoided given the associated 10% to 15% risk for reversible cholestatic liver injury.72 Erythromycin base or erythromycin ethylsuccinate formulations should be favored.

Systemic Steroids—Prednisone is indicated for severe acne with scarring and should only be used during pregnancy after clearance from the patient’s obstetrician. Doses of 0.5 mg/kg or less should be prescribed in combination with systemic antibiotics as well as agents for bone and gastrointestinal tract prophylaxis.29

Zinc—The exact mechanism by which zinc exerts its effects to improve acne remains largely obscure. It has been found effective against inflammatory lesions of mild to moderate acne.73 Generally recommended dosages range from 30 to 200 mg/d but may be associated with gastrointestinal tract disturbances. Dosages of 75 mg/d have shown no harm to the fetus.74 When taking this supplement, patients should not exceed the recommended doses given the risk for hypocupremia associated with high-dose zinc supplementation.

Light-Based Therapies

Phototherapy—Narrowband UVB phototherapy is effective for the treatment of mild to moderate acne.75 It has been proven to be a safe treatment option during pregnancy, but its use has been associated with decreased folic acid levels.76-79 Therefore, in addition to attaining baseline folic acid serum levels, supplementation with folic acid prior to treatment, as per routine prenatal guidelines, should be sought.80

AviClear—The AviClear (Cutera) laser is the first device cleared by the FDA for mild to severe acne in March 2022.81 The FDA clearance for the Accure (Accure Acne Inc) laser, also targeting mild to severe acne, followed soon after (November 2022). Both lasers harbor a wavelength of 1726 nm and target sebaceous glands with electrothermolysis.82,83 Further research and long-term safety data are required before using them in pregnancy.

Other Therapies

Cosmetic Peels—Glycolic acid peels induce epidermolysis and desquamation.84 Although data on use during pregnancy are limited, these peels have limited dermal penetration and are considered safe for use in pregnancy.33,85,86 Similarly, keratolytic lactic acid peels harbor limited dermal penetration and can be safely used in pregnant women.87-89 Salicylic acid peels also work through epidermolysis and desquamation84; however, they tend to penetrate deeper into the skin, reaching down to the basal layer, if large areas are treated or when applied under occlusion.86,90 Although their use is not contraindicated in pregnancy, they should be limited to small areas of coverage.91

Intralesional Triamcinolone—Acne cysts and inflammatory papules can be treated with intralesional triamcinolone injections to relieve acute symptoms such as pain.92 Low doses at concentrations of 2.5 mg/mL are considered compatible with pregnancy when indicated.29

Approaching the Patient Clinical Encounter

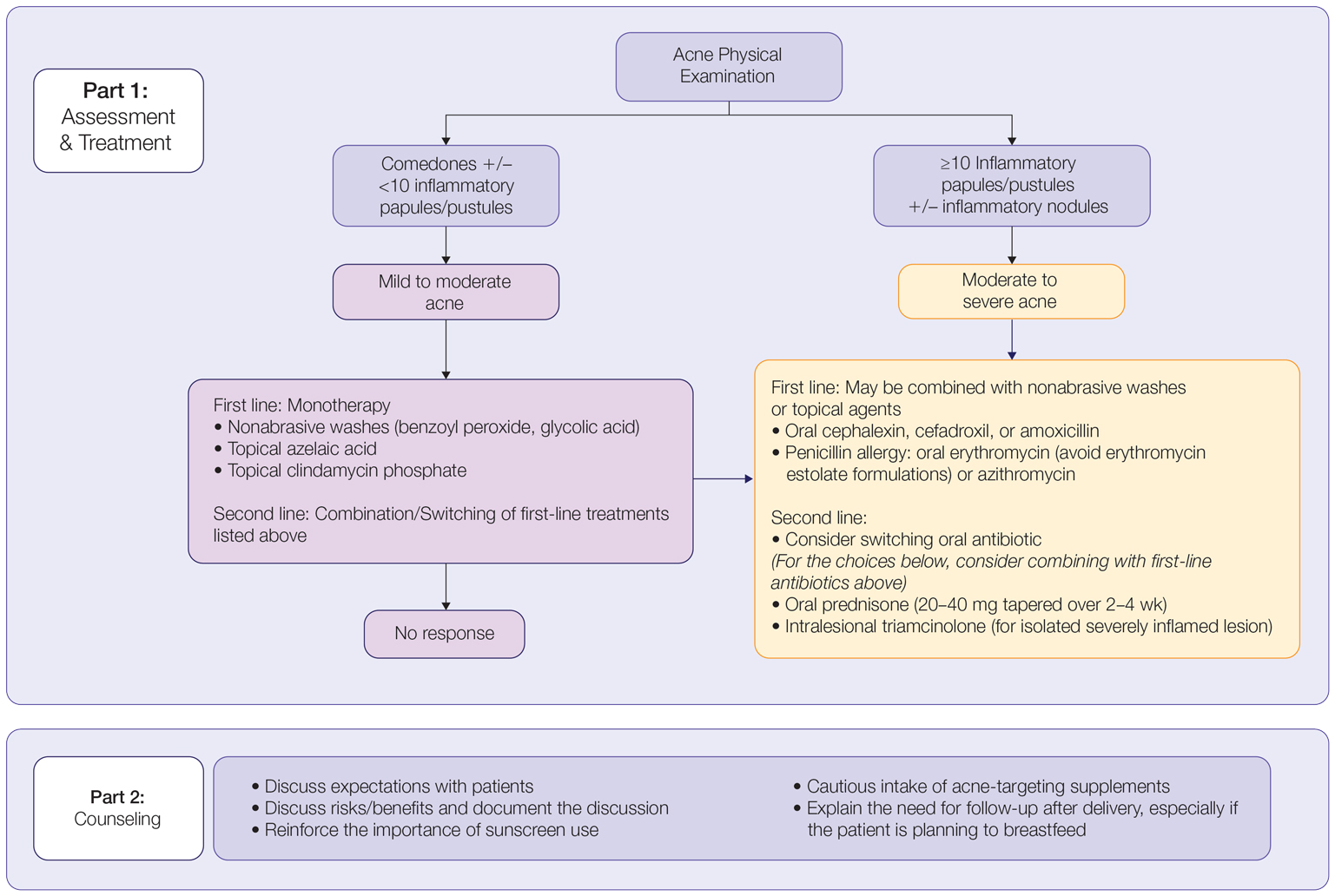

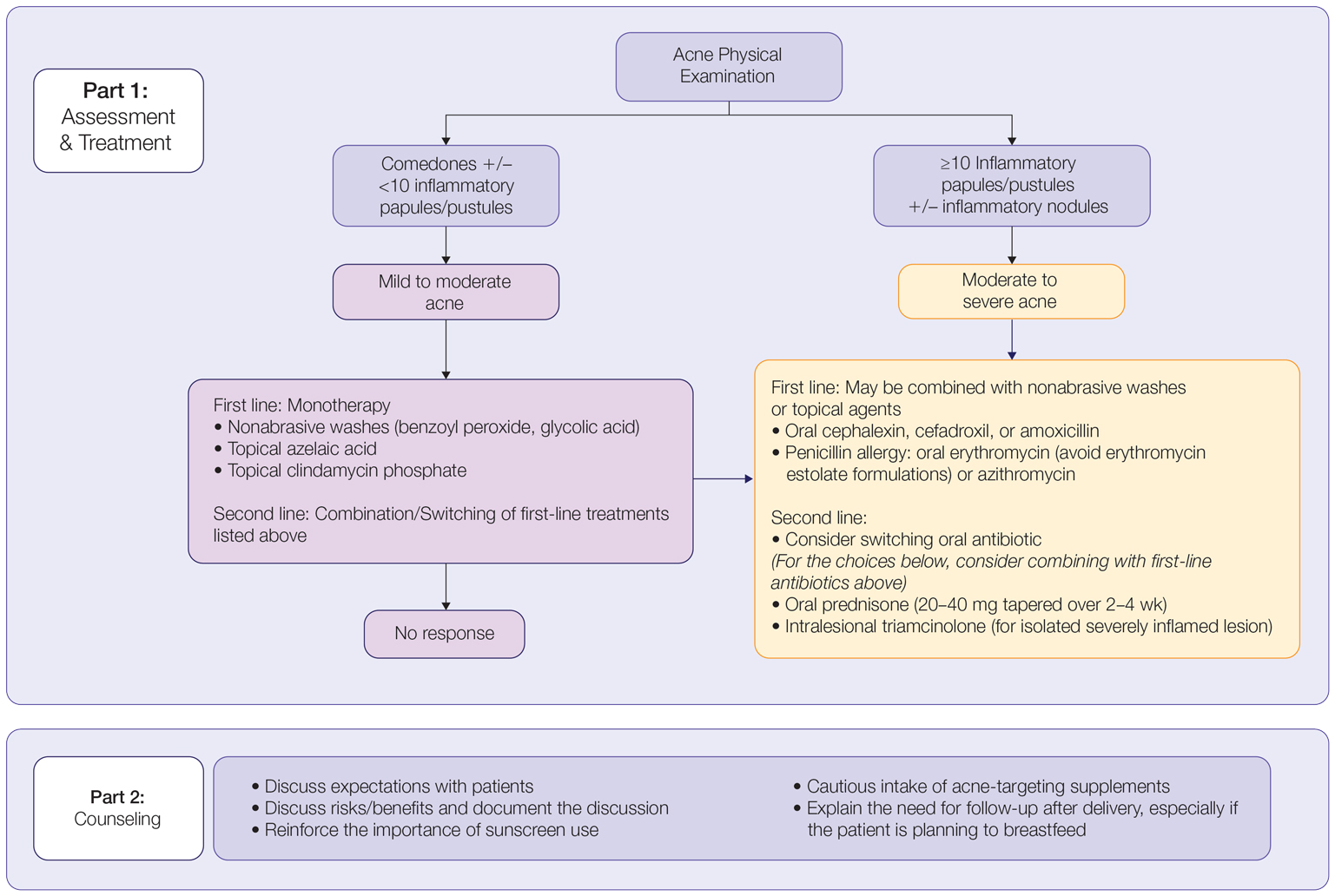

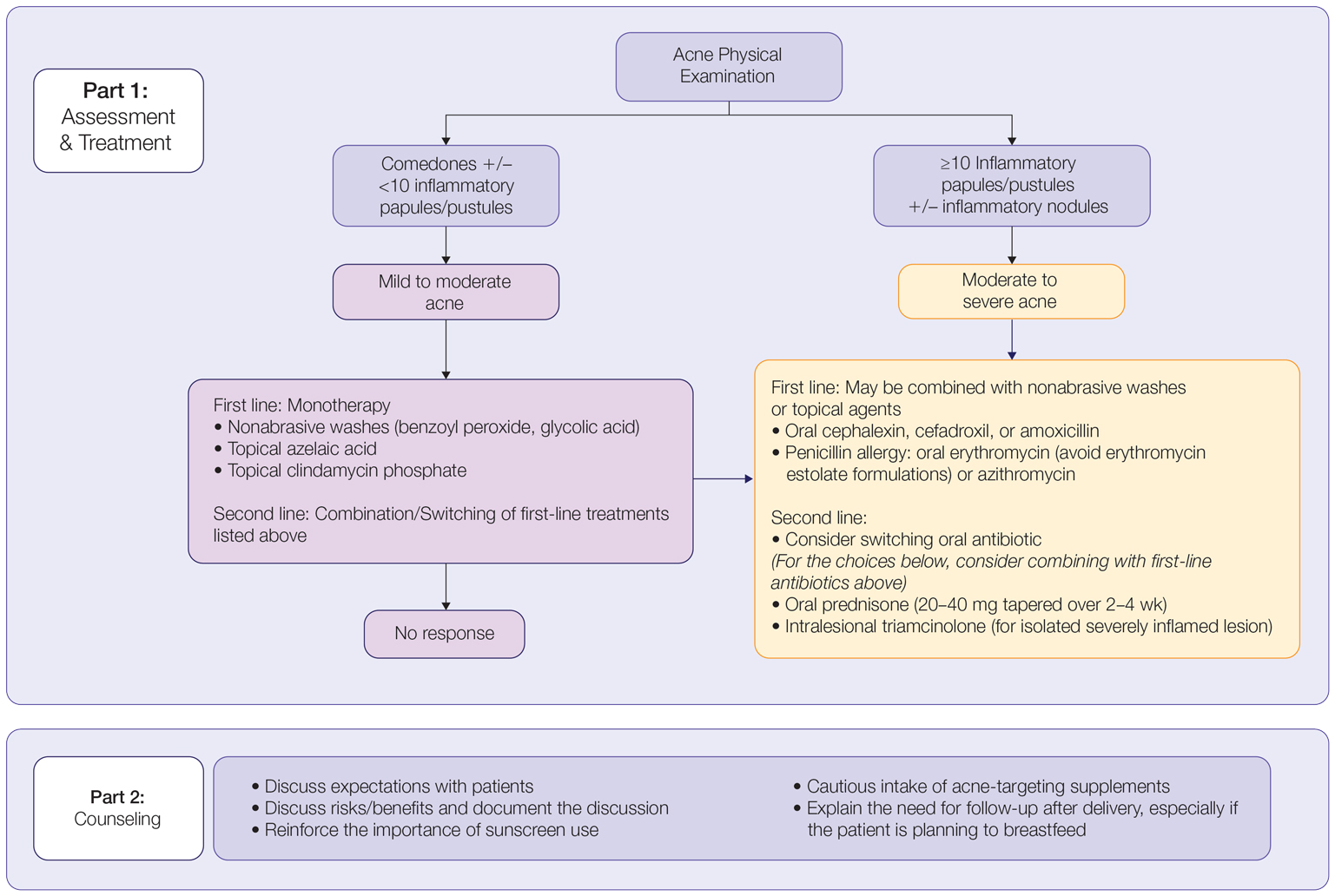

In patients seeking treatment prior to conception, a few recommendations can be made to minimize the risk for acne recurrence or flares during pregnancy. For instance, because data show an association between increased acne severity in those with a higher body mass index and in pregnancy, weight loss may be recommended prior to pregnancy to help mitigate symptoms after conception.7 The Figure summarizes our recommendations for approaching and treating acne in pregnancy.

In all patients, grading the severity of the patient’s acne as mild, moderate, or severe is the first step. The presence of scarring is an additional consideration during the physical examination and should be documented. A careful discussion of treatment expectations and prognosis should be the focus before treatment initiation. Meticulous documentation of the physical examination and discussion with the patient should be prioritized.

To minimize toxicity and risks to the developing fetus, monotherapy is favored. Topical therapy should be considered first line. Safe regimens include mild nonabrasive washes, such as those containing benzoyl peroxide or glycolic acid, or topical azelaic acid or clindamycin phosphate for mild to moderate acne. More severe cases warrant the consideration of systemic medications as second line, as more severe acne is better treated with oral antibiotics such as the macrolides erythromycin or clindamycin or systemic corticosteroids when concern exists for severe scarring. The additional use of physical sunscreen also is recommended.

An important topic to address during the clinical encounter is cautious intake of oral supplements for acne during pregnancy, as they may contain harmful and teratogenic ingredients. A recent search focusing on acne supplements available online between March and May 2020 uncovered 49 different supplements, 26 (53%) of which contained vitamin A.93 Importantly, 3 (6%) of these 49 supplements were likely teratogenic, 4 (8%) contained vitamin A doses exceeding the recommended daily nutritional intake level, and 15 (31%) harbored an unknown teratogenic risk. Furthermore, among the 6 (12%) supplements with vitamin A levels exceeding 10,000 IU, 2 lacked any mention of pregnancy warning, including the supplement with the highest vitamin A dose found in this study.93 Because dietary supplements are not subject to the same stringent regulations by the FDA as drugs, inadvertent use by unaware patients ought to be prevented by careful counseling and education.

Finally, patients should be counseled to seek care following delivery for potentially updated medication management of acne, especially if they are breastfeeding. Co-management with a pediatrician may be indicated during lactation, particularly when newborns are born preterm or with other health conditions that may warrant additional caution with the use of certain agents.

- Bhate K, Williams H. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:474-485.

- Heng AHS, Chew FT. Systematic review of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5754.

- Fisk WA, Lev-Tov HA, Sivamani RK. Epidemiology and management of acne in adult women. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:29-39.

- Perkins A, Cheng C, Hillebrand G, et al. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1054-1060.

- Yang CC, Huang YT, Yu CH, et al. Inflammatory facial acne during uncomplicated pregnancy and post‐partum in adult women: a preliminary hospital‐based prospective observational study of 35 cases from Taiwan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1787-1789.

- Dréno B, Blouin E, Moyse D, et al. Acne in pregnant women: a French survey. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:82-83.

- Kutlu Ö, Karadag˘ AS, Ünal E, et al. Acne in pregnancy: a prospective multicenter, cross‐sectional study of 295 patients in Turkey. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1098-1105.

- Hoefel IDR, Weber MB, Manzoni APD, et al. Striae gravidarum, acne, facial spots, and hair disorders: risk factors in a study with 1284 puerperal patients. J Pregnancy. 2020;2020:8036109.

- Ayanlowo OO, Otrofanowei E, Shorunmu TO, et al. Pregnancy dermatoses: a study of patients attending the antenatal clinic at two tertiary care centers in south west Nigeria. PAMJ Clin Med. 2020;3.

- Bechstein S, Ochsendorf F. Acne and rosacea in pregnancy. Hautarzt. 2017;68:111-119.

- Habeshian KA, Cohen BA. Current issues in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Pediatrics. 2020;145(suppl 2):S225-S230.

- Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products; requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling (21 CFR 201). Fed Regist. 2014;79:72064-72103.

- Sagransky M, Yentzer BA, Feldman SR. Benzoyl peroxide: a review of its current use in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:2555-2562.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part I. Pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:401.e1-401.e14; quiz 415.

- Wolverton SE. Systemic corticosteroids. Comprehensive Dermatol Drug Ther. 2012;3:143-168.

- Kirtschig G, Schaefer C. Dermatological medications and local therapeutics. In: Schaefer C, Peters P, Miller RK, eds. Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation. 3rd edition. Elsevier; 2015:467-492.

- Pugashetti R, Shinkai K. Treatment of acne vulgaris in pregnant patients. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:302-311.

- Touitou E, Godin B, Shumilov M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of clindamycin phosphate and salicylic acid gel in the treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:629-631.

- Schaefer C, Peters PW, Miller RK, eds. Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation: Treatment Options and Risk Assessment. 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2014.

- Birmingham B, Greene D, Rhodes C. Systemic absorption of topical salicylic acid. Int J Dermatol. 1979;18:228-231.

- Trivedi NA. A meta-analysis of low-dose aspirin for prevention of preeclampsia. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:91-95.

- Lucky AW, Maloney JM, Roberts J, et al. Dapsone gel 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris: safety and efficacy of long-term (1 year) treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:981-987.

- Nosten F, McGready R, d’Alessandro U, et al. Antimalarial drugs in pregnancy: a review. Curr Drug Saf. 2006;1:1-15.

- Brabin BJ, Eggelte TA, Parise M, et al. Dapsone therapy for malaria during pregnancy: maternal and fetal outcomes. Drug Saf. 2004;27:633-648.

- Tuffanelli DL. Successful pregnancy in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis treated with low-dose dapsone. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:876.

- Meredith FM, Ormerod AD. The management of acne vulgaris in pregnancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:351-358.

- Kong Y, Tey H. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779-787.

- Leachman SA, Reed BR. The use of dermatologic drugs in pregnancy and lactation. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24:167-197.

- Ly S, Kamal K, Manjaly P, et al. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation: a narrative review. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13:115-130.

- Webster G. Combination azelaic acid therapy for acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:S47-S50.

- Archer CB, Cohen SN, Baron SE. Guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(suppl 1):1-6.

- Graupe K, Cunliffe W, Gollnick H, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical azelaic acid (20 percent cream): an overview of results from European clinical trials and experimental reports. Cutis. 1996;57(1 suppl):20-35.

- Bozzo P, Chua-Gocheco A, Einarson A. Safety of skin care products during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:665-667.

- Munley SM, Kennedy GL, Hurtt ME. Developmental toxicity study of glycolic acid in rats. Drug Chem Toxicol. 1999;22:569-582.

- Chien AL, Qi J, Rainer B, et al. Treatment of acne in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:254-262.

- Stuart B, Maund E, Wilcox C, et al. Topical preparations for the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate acne vulgaris: systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:512-525.

- van Hoogdalem EJ, Baven TL, Spiegel‐Melsen I, et al. Transdermal absorption of clindamycin and tretinoin from topically applied anti‐acne formulations in man. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1998;19:563-569.

- Austin BA, Fleischer AB Jr. The extinction of topical erythromycin therapy for acne vulgaris and concern for the future of topical clindamycin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:145-148.

- Eady EA, Cove J, Holland K, et al. Erythromycin resistant propionibacteria in antibiotic treated acne patients: association with therapeutic failure. Br J. Dermatol. 1989;121:51-57.

- Alkhawaja E, Hammadi S, Abdelmalek M, et al. Antibiotic resistant Cutibacterium acnes among acne patients in Jordan: a cross sectional study. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:1-9.

- Han G, Wu JJ, Del Rosso JQ. Use of topical tazarotene for the treatment of acne vulgaris in pregnancy: a literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:E59-E65.

- Selcen D, Seidman S, Nigro MA. Otocerebral anomalies associated with topical tretinoin use. Brain Dev. 2000;22:218-220.

- Moretz D. Drug Class Update with New Drug Evaluations: Topical Products for Inflammatory Skin Conditions. Oregon State University Drug Use & Research Management Program; December 2022. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.orpdl.org/durm/meetings/meetingdocs/2022_12_01/archives/2022_12_01_Inflammatory_Skin_Dz_ClassUpdate.pdf

- Kaplan YC, Ozsarfati J, Etwel F, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following first‐trimester exposure to topical retinoids: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1132-1141.

- Menter A. Pharmacokinetics and safety of tazarotene. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 3):S31-S35.

- Autret E, Berjot M, Jonville-Béra A-P, et al. Anophthalmia and agenesis of optic chiasma associated with adapalene gel in early pregnancy. Lancet. 1997;350:339.

- Weiss J, Mallavalli S, Meckfessel M, et al. Safe use of adapalene 0.1% gel in a non-prescription environment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:1330-1335.

- Alessandro Mazzetti M. A phase 2b, randomized, double-blind vehicle controlled, dose escalation study evaluating clascoterone 0.1%, 0.5%, and 1% topical cream in subjects with facial acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:570-575.

- Eichenfield L, Hebert A, Gold LS, et al. Open-label, long-term extension study to evaluate the safety of clascoterone (CB-03-01) cream, 1% twice daily, in patients with acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:477-485.

- Trifu V, Tiplica GS, Naumescu E, et al. Cortexolone 17α‐propionate 1% cream, a new potent antiandrogen for topical treatment of acne vulgaris. a pilot randomized, double‐blind comparative study vs. placebo and tretinoin 0.05% cream. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:177-183.

- Hebert A, Thiboutot D, Gold LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical clascoterone cream, 1%, for treatment in patients with facial acne: two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:621-630.

- Alkhodaidi ST, Al Hawsawi KA, Alkhudaidi IT, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical clascoterone cream for treatment of acne vulgaris: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized placebo‐controlled trials. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14609.

- Clasoterone. Package insert. Cassiopea Inc; 2020.

- Paik J. Topical minocycline foam 4%: a review in acne vulgaris. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:449-456.

- Jones TM, Ellman H. Pharmacokinetic comparison of once-daily topical minocycline foam 4% vs oral minocycline for moderate-to-severe acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1022-1028.

- Minocycline hydrochloride extended-release tablets. Package insert. JG Pharma; July 2020. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.jgpharmainc.com/assets/pdf/minocycline-hydrochloride.pdf

- Dinnendahl V, Fricke U (eds). Arzneistoff-Profile: Basisinformation über arzneiliche Wirkstoffe. Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag; 2010.

- Martins AM, Marto JM, Johnson JL, et al. A review of systemic minocycline side effects and topical minocycline as a safer alternative for treating acne and rosacea. Antibiotics. 2021;10:757.

- Landis MN. Optimizing isotretinoin treatment of acne: update on current recommendations for monitoring, dosing, safety, adverse effects, compliance, and outcomes. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:411-419.

- Draghici C-C, Miulescu R-G, Petca R-C, et al. Teratogenic effect of isotretinoin in both fertile females and males. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21:1-5.

- Barker RA, Wilcox C, Layton AM. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: an update of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:303-305.

- Han JJ, Faletsky A, Barbieri JS, et al. New acne therapies and updates on use of spironolactone and isotretinoin: a narrative review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:79-91.

- Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Patel DJ, Bhatia N. Oral antibiotics for acne. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:193-204.

- Jick H, Holmes LB, Hunter JR, et al. First-trimester drug use and congenital disorders. JAMA. 1981;246:343-346.

- Valente Duarte de Sousa IC. An overview of sarecycline for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2021;22:145-154.

- Hussar DA, Chahine EB. Omadacycline tosylate, sarecycline hydrochloride, rifamycin sodium, and moxidectin. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2019;59:756-760.

- Haidari W, Bruinsma R, Cardenas-de la Garza JA, et al. Sarecycline review. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:164-170.

- Feldman S, Careccia RE, Barham KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:2123-2130.

- Gammon WR, Meyer C, Lantis S, et al. Comparative efficacy of oral erythromycin versus oral tetracycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:183-186.

- Källén BA, Olausson PO, Danielsson BR. Is erythromycin therapy teratogenic in humans? Reprod Toxicol. 2005;20:209-214.

- McCormack WM, George H, Donner A, et al. Hepatotoxicity of erythromycin estolate during pregnancy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;12:630-635.

- Cervantes J, Eber AE, Perper M, et al. The role of zinc in the treatment of acne: a review of the literature. Dermatolog Ther. 2018;31:e12576.

- Dréno B, Blouin E. Acne, pregnant women and zinc salts: a literature review [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;135:27-33.

- Eid MM, Saleh MS, Allam NM, et al. Narrow band ultraviolet B versus red light-emitting diodes in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris: a randomized controlled trial. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2021;39:418-424.

- Zeichner JA. Narrowband UV-B phototherapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:537-539.

- El-Saie LT, Rabie AR, Kamel MI, et al. Effect of narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy on serum folic acid levels in patients with psoriasis. Lasers Med Sci. 2011;26:481-485.

- Park KK, Murase JE. Narrowband UV-B phototherapy during pregnancy and folic acid depletion. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:132-133.

- Jablonski NG. A possible link between neural tube defects and ultraviolet light exposure. Med Hypotheses. 1999;52:581-582.

- Zhang M, Goyert G, Lim HW. Folate and phototherapy: what should we inform our patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:958-964.

- AviClear. Cutera website. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.cutera.com/solutions/aviclear/

- Wu X, Yang Y, Wang Y, et al. Treatment of refractory acne using selective sebaceous gland electro-thermolysis combined with non-thermal plasma. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2021;23:188-194.

- Ahn GR, Kim JM, Park SJ, et al. Selective sebaceous gland electrothermolysis using a single microneedle radiofrequency device for acne patients: a prospective randomized controlled study. Lasers Surg Med. 2020;52:396-401.

- Fabbrocini G, De Padova MP, Tosti A. Chemical peels: what’s new and what isn’t new but still works well. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25:329-336.

- Andersen FA. Final report on the safety assessment of glycolic acid, ammonium, calcium, potassium, and sodium glycolates, methyl, ethyl, propyl, and butyl glycolates, and lactic acid, ammonium, calcium, potassium, sodium, and TEA-lactates, methyl, ethyl, isopropyl, and butyl lactates, and lauryl, myristyl, and cetyl lactates. Int J Toxicol. 1998;17(1_suppl):1-241.

- Lee KC, Korgavkar K, Dufresne RG Jr, et al. Safety of cosmetic dermatologic procedures during pregnancy. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1573-1586.

- James AH, Brancazio LR, Price T. Aspirin and reproductive outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:49-57.

- Zhou W-S, Xu L, Xie S-H, et al. Decreased birth weight in relation to maternal urinary trichloroacetic acid levels. Sci Total Environ. 2012;416:105-110.

- Schwartz DB, Greenberg MD, Daoud Y, et al. Genital condylomas in pregnancy: use of trichloroacetic acid and laser therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:1407-1416.

- Starkman SJ, Mangat DS. Chemical peel (deep, medium, light). Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2020;28:45-57.

- Trivedi M, Kroumpouzos G, Murase J. A review of the safety of cosmetic procedures during pregnancy and lactation. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:6-10.

- Gallagher T, Taliercio M, Nia JK, et al. Dermatologist use of intralesional triamcinolone in the treatment of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:41-43.

- Zamil DH, Burns EK, Perez-Sanchez A, et al. Risk of birth defects from vitamin A “acne supplements” sold online. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:e2021075.

Acne vulgaris, or acne, is a highly common inflammatory skin disorder affecting up to 85% of the population, and it constitutes the most commonly presenting chief concern in routine dermatology practice.1 Older teenagers and young adults are most often affected by acne.2 Although acne generally is more common in males, adult-onset acne occurs more frequently in women.2,3 Black and Hispanic women are at higher risk for acne compared to those of Asian, White, or Continental Indian descent.4 As such, acne is a common concern in all women of childbearing age.

Concerns for maternal and fetal safety are important therapeutic considerations, especially because hormonal and physiologic changes in pregnancy can lead to onset of inflammatory acne lesions, particularly during the second and third trimesters.5 Female patients younger than 25 years; with a higher body mass index, prior irregular menstruation, or polycystic ovary syndrome; or those experiencing their first pregnancy are thought to be more commonly affected.5-7 In fact, acne affects up to 43% of pregnant women, and lesions typically extend beyond the face to involve the trunk.6,8-10 Importantly, one-third of women with a history of acne experience symptom relapse after disease-free periods, while two-thirds of those with ongoing disease experience symptom deterioration during pregnancy.10 Although acne is not a life-threatening condition, it has a well-documented, detrimental impact on social, emotional, and psychological well-being, namely self-perception, social interactions, quality-of-life scores, depression, and anxiety.11

Therefore, safe and effective treatment of pregnant women is of paramount importance. Because pregnant women are not included in clinical trials, there is a paucity of medication safety data, further augmented by inefficient access to available information. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy safety categories were updated in 2015, letting go of the traditional A, B, C, D, and X categories.12 The Table reviews the current pregnancy classification system. In this narrative review, we summarize the most recent available data and recommendations on the safety and efficacy of acne treatment during pregnancy.

Topical Treatments for Acne

Benzoyl Peroxide—Benzoyl peroxide commonly is used as first-line therapy alone or in combination with other agents for the treatment of mild to moderate acne.13 It is safe for use during pregnancy.14 Although the medication is systemically absorbed, it undergoes complete metabolism to benzoic acid, a commonly used food additive.15,16 Benzoic acid has low bioavailability, as it gets rapidly metabolized by the kidneys; therefore, benzoyl peroxide is unlikely to reach clinically significant levels in the maternal circulation and consequently the fetal circulation. Additionally, it has a low risk for causing congenital malformations.17

Salicylic Acid—For mild to moderate acne, salicylic acid is a second-line agent that likely is safe for use by pregnant women at low concentrations and over limited body surface areas.14,18,19 There is minimal systemic absorption of the drug.20 Additionally, aspirin, which is broken down in the body into salicylic acid, is used in low doses for the treatment of pre-eclampsia during pregnancy.21

Dapsone—The use of dapsone gel 5% as a second-line agent has shown efficacy for mild to moderate acne.22 The oral formulation, commonly used for malaria and leprosy prophylaxis, has failed to show associated fetal toxicity or congenital anomalies.23,24 It also has been used as a first-line treatment for dermatitis herpetiformis in pregnancy.25 Although the medication likely is safe, it is better to minimize its use during the third trimester to reduce the theoretical risk for hyperbilirubinemia in the neonate.17,26-29

Azelaic Acid—Azelaic acid effectively targets noninflammatory and inflammatory acne and generally is well tolerated, harboring a good safety profile.30 Topical 20% azelaic acid has localized antibacterial and comedolytic effects and is safe for use during pregnancy.31,32

Glycolic Acid—Limited data exist on the safety of glycolic acid during pregnancy. In vitro studies have shown up to 27% systemic absorption depending on pH, concentration, and duration of application.33 Animal reproductive studies involving rats have shown fetal multisystem malformations and developmental abnormalities with oral administration of glycolic acid at doses far exceeding those used in humans.34 Although no human reproductive studies exist, topical glycolic acid is unlikely to reach the developing fetus in notable amounts, and the medication is likely safe for use.17,35

Clindamycin—Topical clindamycin phosphate is an effective and well-tolerated agent for the treatment of mild to moderate acne.36 Its systemic absorption is minimal, and it is considered safe for use during all trimesters of pregnancy.14,17,26,27,35,37

Erythromycin—Topical erythromycin is another commonly prescribed topical antibiotic used to target mild to moderate acne. However, its use recently has been associated with a decrease in efficacy secondary to the rise of antibacterial resistance in the community.38-40 Nevertheless, it remains a safe treatment for use during all trimesters of pregnancy.14,17,26,27,35,37

Topical Retinoids—Vitamin A derivatives (also known as retinoids) are the mainstay for the treatment of mild to moderate acne. Limited data exist regarding pregnancy outcomes after in utero exposure.41 A rare case report suggested topical tretinoin has been associated with fetal otocerebral anomalies.42 For tazarotene, teratogenic effects were seen in animal reproductive studies at doses exceeding maximum recommended human doses.41,43 However, a large meta-analysis failed to find a clear risk for increased congenital malformations, spontaneous abortions, stillbirth, elective termination of pregnancy, low birthweight, or prematurity following first-trimester exposure to topical retinoids.44 As the level of exposure that could lead to teratogenicity in humans is unknown, avoidance of both tretinoin and tazarotene is recommended in pregnant women.41,45 Nevertheless, women inadvertently exposed should be reassured.44

Conversely, adapalene has been associated with 1 case of anophthalmia and agenesis of the optic chiasma in a fetus following exposure until 13 weeks’ gestation.46 However, a large, open-label trial prior to the patient transitioning from adapalene to over-the-counter treatment showed that the drug harbors a large and reassuring margin of safety and no risk for teratogenicity in a maximal usage trial and Pregnancy Safety Review.47 Therefore, adapalene gel 0.1% is a safe and effective medication for the treatment of acne in a nonprescription environment and does not pose harm to the fetus.

Clascoterone—Clascoterone is a novel topical antiandrogenic drug approved for the treatment of hormonal and inflammatory moderate to severe acne.48-51 Human reproductive data are limited to 1 case of pregnancy that occurred during phase 3 trial investigations, and no adverse outcomes were reported.51 Minimal systemic absorption follows topical use.52 Nonetheless, dose-independent malformations were reported in animal reproductive studies.53 As such, it remains better to avoid the use of clascoterone during pregnancy pending further safety data.

Minocycline Foam—Minocycline foam 4% is approved to treat inflammatory lesions of nonnodular moderate to severe acne in patients 9 years and older.54 Systemic absorption is minimal, and the drug has limited bioavailability with minimal systemic accumulation in the patient’s serum.55 Given this information, it is unlikely that topical minocycline will reach notable levels in the fetal serum or harbor teratogenic effects, as seen with the oral formulation.56 However, it may be best to avoid its use during the second and third trimesters given the potential risk for tooth discoloration in the fetus.57,58

Systemic Treatments for Acne

Isotretinoin—Isotretinoin is the most effective treatment for moderate to severe acne with a well-documented potential for long-term clearance.59 Its use during pregnancy is absolutely contraindicated, as the medication is a well-known teratogen. Associated congenital malformations include numerous craniofacial defects, cardiovascular and neurologic malformations, or thymic disorders that are estimated to affect 20% to 35% of infants exposed in utero.60 Furthermore, strict contraception use during treatment is mandated for patients who can become pregnant. It is recommended to wait at least 1 month and 1 menstrual cycle after medication discontinuation before attempting to conceive.17 Pregnancy termination is recommended if conception occurs during treatment with isotretinoin.

Spironolactone—Spironolactone is an androgen-receptor antagonist commonly prescribed off label for mild to severe acne in females.61,62 Spironolactone promotes the feminization of male fetuses and should be avoided in pregnancy.63

Doxycycline/Minocycline—Tetracyclines are the most commonly prescribed oral antibiotics for moderate to severe acne.64 Although highly effective at treating acne, tetracyclines generally should be avoided in pregnancy. First-trimester use of doxycycline is not absolutely contraindicated but should be reserved for severe illness and not employed for the treatment of acne. However, accidental exposure to doxycycline has not been associated with congenital malformations.65 Nevertheless, after the 15th week of gestation, permanent tooth discoloration and bone growth inhibition in the fetus are serious and well-documented risks.14,17 Additional adverse events following in utero exposure include infantile inguinal hernia, hypospadias, and limb hypoplasia.63

Sarecycline—Sarecycline is a novel tetracycline-class antibiotic for the treatment of moderate to severe inflammatory acne. It has a narrower spectrum of activity compared to its counterparts within its class, which translates to an improved safety profile, namely when it comes to gastrointestinal tract microbiome disruption and potentially decreased likelihood of developing bacterial resistance.66 Data on human reproductive studies are limited, but it is advisable to avoid sarecycline in pregnancy, as it may cause adverse developmental effects in the fetus, such as reduced bone growth, in addition to the well-known tetracycline-associated risk for permanent discoloration of the teeth if used during the second and third trimesters.67,68

Erythromycin—Oral erythromycin targets moderate to severe inflammatory acne and is considered safe for use during pregnancy.69,70 There has been 1 study reporting an increased risk for atrial and ventricular septal defects (1.8%) and pyloric stenosis (0.2%), but these risks are still uncertain, and erythromycin is considered compatible with pregnancy.71 However, erythromycin estolate formulations should be avoided given the associated 10% to 15% risk for reversible cholestatic liver injury.72 Erythromycin base or erythromycin ethylsuccinate formulations should be favored.

Systemic Steroids—Prednisone is indicated for severe acne with scarring and should only be used during pregnancy after clearance from the patient’s obstetrician. Doses of 0.5 mg/kg or less should be prescribed in combination with systemic antibiotics as well as agents for bone and gastrointestinal tract prophylaxis.29

Zinc—The exact mechanism by which zinc exerts its effects to improve acne remains largely obscure. It has been found effective against inflammatory lesions of mild to moderate acne.73 Generally recommended dosages range from 30 to 200 mg/d but may be associated with gastrointestinal tract disturbances. Dosages of 75 mg/d have shown no harm to the fetus.74 When taking this supplement, patients should not exceed the recommended doses given the risk for hypocupremia associated with high-dose zinc supplementation.

Light-Based Therapies

Phototherapy—Narrowband UVB phototherapy is effective for the treatment of mild to moderate acne.75 It has been proven to be a safe treatment option during pregnancy, but its use has been associated with decreased folic acid levels.76-79 Therefore, in addition to attaining baseline folic acid serum levels, supplementation with folic acid prior to treatment, as per routine prenatal guidelines, should be sought.80

AviClear—The AviClear (Cutera) laser is the first device cleared by the FDA for mild to severe acne in March 2022.81 The FDA clearance for the Accure (Accure Acne Inc) laser, also targeting mild to severe acne, followed soon after (November 2022). Both lasers harbor a wavelength of 1726 nm and target sebaceous glands with electrothermolysis.82,83 Further research and long-term safety data are required before using them in pregnancy.

Other Therapies

Cosmetic Peels—Glycolic acid peels induce epidermolysis and desquamation.84 Although data on use during pregnancy are limited, these peels have limited dermal penetration and are considered safe for use in pregnancy.33,85,86 Similarly, keratolytic lactic acid peels harbor limited dermal penetration and can be safely used in pregnant women.87-89 Salicylic acid peels also work through epidermolysis and desquamation84; however, they tend to penetrate deeper into the skin, reaching down to the basal layer, if large areas are treated or when applied under occlusion.86,90 Although their use is not contraindicated in pregnancy, they should be limited to small areas of coverage.91

Intralesional Triamcinolone—Acne cysts and inflammatory papules can be treated with intralesional triamcinolone injections to relieve acute symptoms such as pain.92 Low doses at concentrations of 2.5 mg/mL are considered compatible with pregnancy when indicated.29

Approaching the Patient Clinical Encounter

In patients seeking treatment prior to conception, a few recommendations can be made to minimize the risk for acne recurrence or flares during pregnancy. For instance, because data show an association between increased acne severity in those with a higher body mass index and in pregnancy, weight loss may be recommended prior to pregnancy to help mitigate symptoms after conception.7 The Figure summarizes our recommendations for approaching and treating acne in pregnancy.

In all patients, grading the severity of the patient’s acne as mild, moderate, or severe is the first step. The presence of scarring is an additional consideration during the physical examination and should be documented. A careful discussion of treatment expectations and prognosis should be the focus before treatment initiation. Meticulous documentation of the physical examination and discussion with the patient should be prioritized.

To minimize toxicity and risks to the developing fetus, monotherapy is favored. Topical therapy should be considered first line. Safe regimens include mild nonabrasive washes, such as those containing benzoyl peroxide or glycolic acid, or topical azelaic acid or clindamycin phosphate for mild to moderate acne. More severe cases warrant the consideration of systemic medications as second line, as more severe acne is better treated with oral antibiotics such as the macrolides erythromycin or clindamycin or systemic corticosteroids when concern exists for severe scarring. The additional use of physical sunscreen also is recommended.

An important topic to address during the clinical encounter is cautious intake of oral supplements for acne during pregnancy, as they may contain harmful and teratogenic ingredients. A recent search focusing on acne supplements available online between March and May 2020 uncovered 49 different supplements, 26 (53%) of which contained vitamin A.93 Importantly, 3 (6%) of these 49 supplements were likely teratogenic, 4 (8%) contained vitamin A doses exceeding the recommended daily nutritional intake level, and 15 (31%) harbored an unknown teratogenic risk. Furthermore, among the 6 (12%) supplements with vitamin A levels exceeding 10,000 IU, 2 lacked any mention of pregnancy warning, including the supplement with the highest vitamin A dose found in this study.93 Because dietary supplements are not subject to the same stringent regulations by the FDA as drugs, inadvertent use by unaware patients ought to be prevented by careful counseling and education.

Finally, patients should be counseled to seek care following delivery for potentially updated medication management of acne, especially if they are breastfeeding. Co-management with a pediatrician may be indicated during lactation, particularly when newborns are born preterm or with other health conditions that may warrant additional caution with the use of certain agents.

Acne vulgaris, or acne, is a highly common inflammatory skin disorder affecting up to 85% of the population, and it constitutes the most commonly presenting chief concern in routine dermatology practice.1 Older teenagers and young adults are most often affected by acne.2 Although acne generally is more common in males, adult-onset acne occurs more frequently in women.2,3 Black and Hispanic women are at higher risk for acne compared to those of Asian, White, or Continental Indian descent.4 As such, acne is a common concern in all women of childbearing age.

Concerns for maternal and fetal safety are important therapeutic considerations, especially because hormonal and physiologic changes in pregnancy can lead to onset of inflammatory acne lesions, particularly during the second and third trimesters.5 Female patients younger than 25 years; with a higher body mass index, prior irregular menstruation, or polycystic ovary syndrome; or those experiencing their first pregnancy are thought to be more commonly affected.5-7 In fact, acne affects up to 43% of pregnant women, and lesions typically extend beyond the face to involve the trunk.6,8-10 Importantly, one-third of women with a history of acne experience symptom relapse after disease-free periods, while two-thirds of those with ongoing disease experience symptom deterioration during pregnancy.10 Although acne is not a life-threatening condition, it has a well-documented, detrimental impact on social, emotional, and psychological well-being, namely self-perception, social interactions, quality-of-life scores, depression, and anxiety.11

Therefore, safe and effective treatment of pregnant women is of paramount importance. Because pregnant women are not included in clinical trials, there is a paucity of medication safety data, further augmented by inefficient access to available information. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy safety categories were updated in 2015, letting go of the traditional A, B, C, D, and X categories.12 The Table reviews the current pregnancy classification system. In this narrative review, we summarize the most recent available data and recommendations on the safety and efficacy of acne treatment during pregnancy.

Topical Treatments for Acne

Benzoyl Peroxide—Benzoyl peroxide commonly is used as first-line therapy alone or in combination with other agents for the treatment of mild to moderate acne.13 It is safe for use during pregnancy.14 Although the medication is systemically absorbed, it undergoes complete metabolism to benzoic acid, a commonly used food additive.15,16 Benzoic acid has low bioavailability, as it gets rapidly metabolized by the kidneys; therefore, benzoyl peroxide is unlikely to reach clinically significant levels in the maternal circulation and consequently the fetal circulation. Additionally, it has a low risk for causing congenital malformations.17

Salicylic Acid—For mild to moderate acne, salicylic acid is a second-line agent that likely is safe for use by pregnant women at low concentrations and over limited body surface areas.14,18,19 There is minimal systemic absorption of the drug.20 Additionally, aspirin, which is broken down in the body into salicylic acid, is used in low doses for the treatment of pre-eclampsia during pregnancy.21