User login

Shelf Life for Opioid Overdose Drug Naloxone Extended

At the request of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Emergent BioSolutions has extended the shelf life of the rapid opioid overdose reversal agent, naloxone (4 mg) nasal spray (Narcan), from 3 to 4 years.

Naloxone is “an important tool” in addressing opioid overdoses, and this extension supports the FDA’s “efforts to ensure more OTC naloxone products remain available to the public,” Marta Sokolowska, PhD, with the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

Naloxone nasal spray was first approved by the FDA in 2015 as a prescription drug. Last spring, the agency approved the drug for over-the-counter use.

“The shelf life of products that were produced and distributed prior to this announcement is not affected and remains unchanged. Prescribers, patients, and caregivers are advised to continue to abide by the expiration date printed on each product’s packaging and within the product’s labeling,” the FDA advised.

“FDA’s request for this shelf-life extension is a testament to the agency’s continuing progress toward implementing the FDA Overdose Prevention Framework, which provides our vision to undertake impactful, creative actions to encourage harm reduction and innovation in reducing controlled substance-related overdoses and deaths,” the agency said.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from 1999 to 2021, nearly 645,000 people died from an overdose involving any opioid, including prescription and illicit opioids.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

At the request of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Emergent BioSolutions has extended the shelf life of the rapid opioid overdose reversal agent, naloxone (4 mg) nasal spray (Narcan), from 3 to 4 years.

Naloxone is “an important tool” in addressing opioid overdoses, and this extension supports the FDA’s “efforts to ensure more OTC naloxone products remain available to the public,” Marta Sokolowska, PhD, with the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

Naloxone nasal spray was first approved by the FDA in 2015 as a prescription drug. Last spring, the agency approved the drug for over-the-counter use.

“The shelf life of products that were produced and distributed prior to this announcement is not affected and remains unchanged. Prescribers, patients, and caregivers are advised to continue to abide by the expiration date printed on each product’s packaging and within the product’s labeling,” the FDA advised.

“FDA’s request for this shelf-life extension is a testament to the agency’s continuing progress toward implementing the FDA Overdose Prevention Framework, which provides our vision to undertake impactful, creative actions to encourage harm reduction and innovation in reducing controlled substance-related overdoses and deaths,” the agency said.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from 1999 to 2021, nearly 645,000 people died from an overdose involving any opioid, including prescription and illicit opioids.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

At the request of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Emergent BioSolutions has extended the shelf life of the rapid opioid overdose reversal agent, naloxone (4 mg) nasal spray (Narcan), from 3 to 4 years.

Naloxone is “an important tool” in addressing opioid overdoses, and this extension supports the FDA’s “efforts to ensure more OTC naloxone products remain available to the public,” Marta Sokolowska, PhD, with the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

Naloxone nasal spray was first approved by the FDA in 2015 as a prescription drug. Last spring, the agency approved the drug for over-the-counter use.

“The shelf life of products that were produced and distributed prior to this announcement is not affected and remains unchanged. Prescribers, patients, and caregivers are advised to continue to abide by the expiration date printed on each product’s packaging and within the product’s labeling,” the FDA advised.

“FDA’s request for this shelf-life extension is a testament to the agency’s continuing progress toward implementing the FDA Overdose Prevention Framework, which provides our vision to undertake impactful, creative actions to encourage harm reduction and innovation in reducing controlled substance-related overdoses and deaths,” the agency said.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from 1999 to 2021, nearly 645,000 people died from an overdose involving any opioid, including prescription and illicit opioids.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Even Intentional Weight Loss Linked With Cancer

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As anyone who has been through medical training will tell you, some little scenes just stick with you. I had been seeing a patient in our resident clinic in West Philly for a couple of years. She was in her mid-60s with diabetes and hypertension and a distant smoking history. She was overweight and had been trying to improve her diet and lose weight since I started seeing her. One day she came in and was delighted to report that she had finally started shedding some pounds — about 15 in the past 2 months.

I enthusiastically told my preceptor that my careful dietary counseling had finally done the job. She looked through the chart for a moment and asked, “Is she up to date on her cancer screening?” A workup revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. The patient did well, actually, but the story stuck with me.

The textbooks call it “unintentional weight loss,” often in big, scary letters, and every doctor will go just a bit pale if a patient tells them that, despite efforts not to, they are losing weight. But true unintentional weight loss is not that common. After all, most of us are at least half-heartedly trying to lose weight all the time. Should doctors be worried when we are successful?

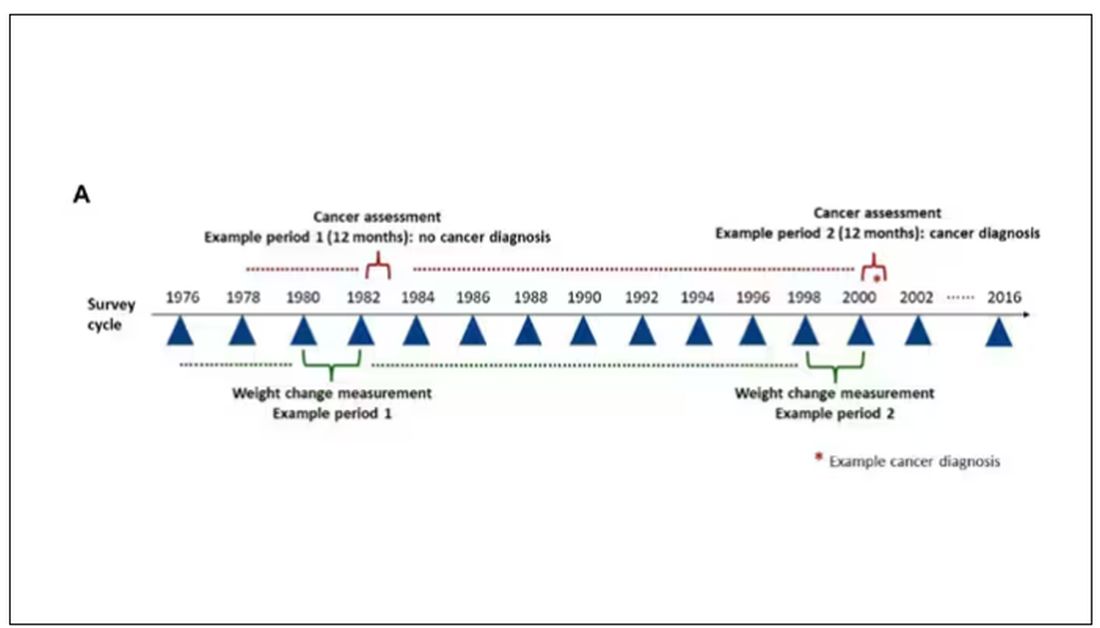

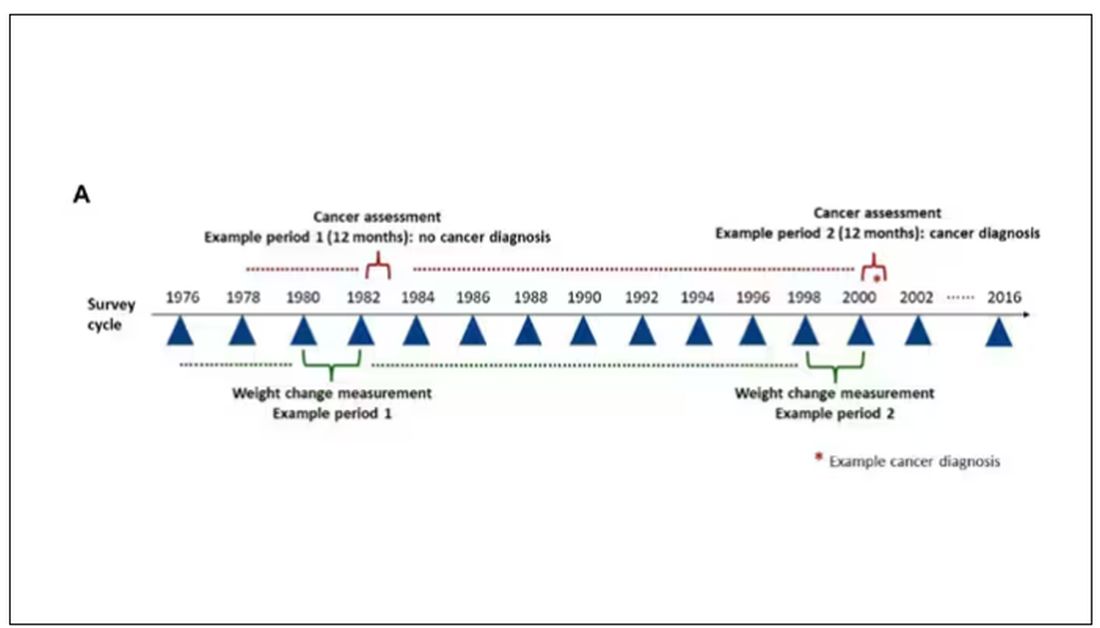

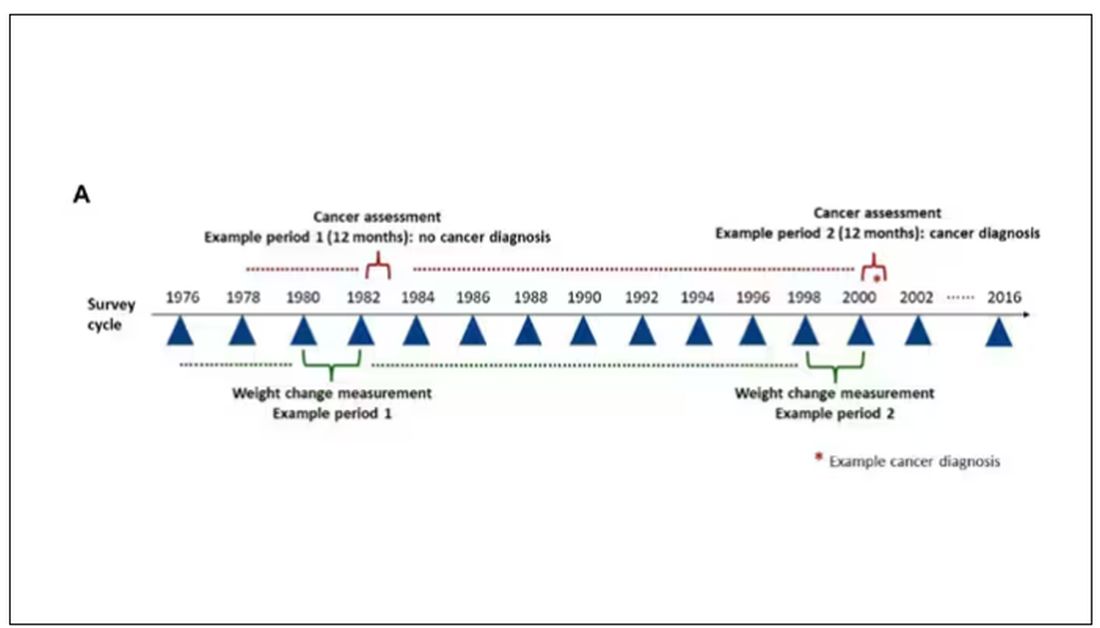

A new study suggests that perhaps they should. We’re talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, which combined participants from two long-running observational cohorts: 120,000 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, and 50,000 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. (These cohorts started in the 1970s and 1980s, so we’ll give them a pass on the gender-specific study designs.)

The rationale of enrolling healthcare providers in these cohort studies is that they would be reliable witnesses of their own health status. If a nurse or doctor says they have pancreatic cancer, it’s likely that they truly have pancreatic cancer. Detailed health surveys were distributed to the participants every other year, and the average follow-up was more than a decade.

Participants recorded their weight — as an aside, a nested study found that self-reported rate was extremely well correlated with professionally measured weight — and whether they had received a cancer diagnosis since the last survey.

This allowed researchers to look at the phenomenon described above. Would weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer? And, more interestingly, would intentional weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer.

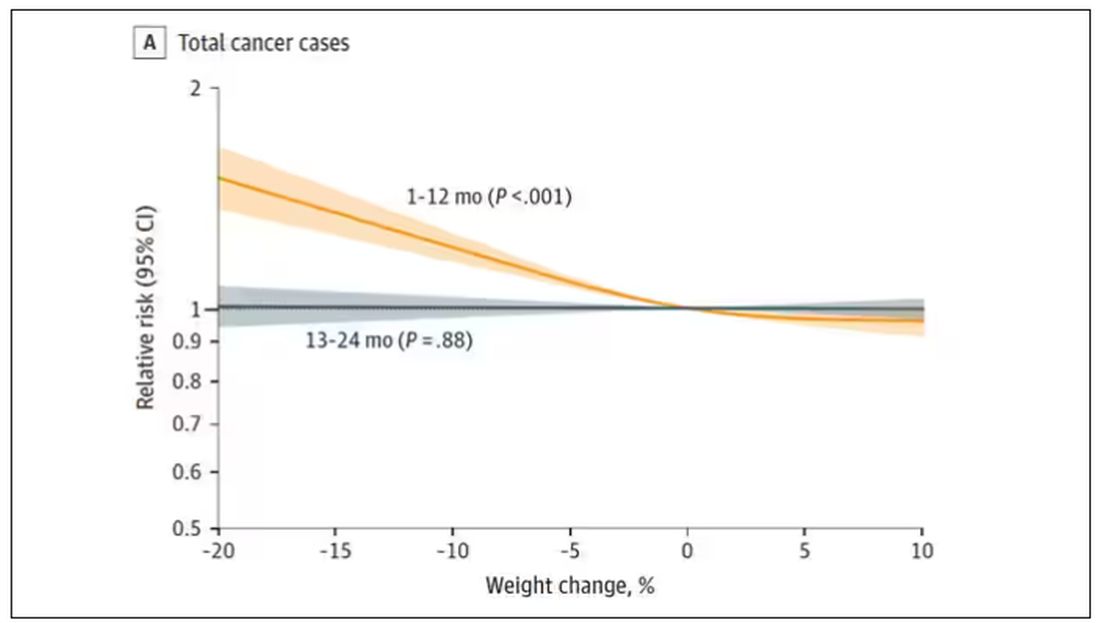

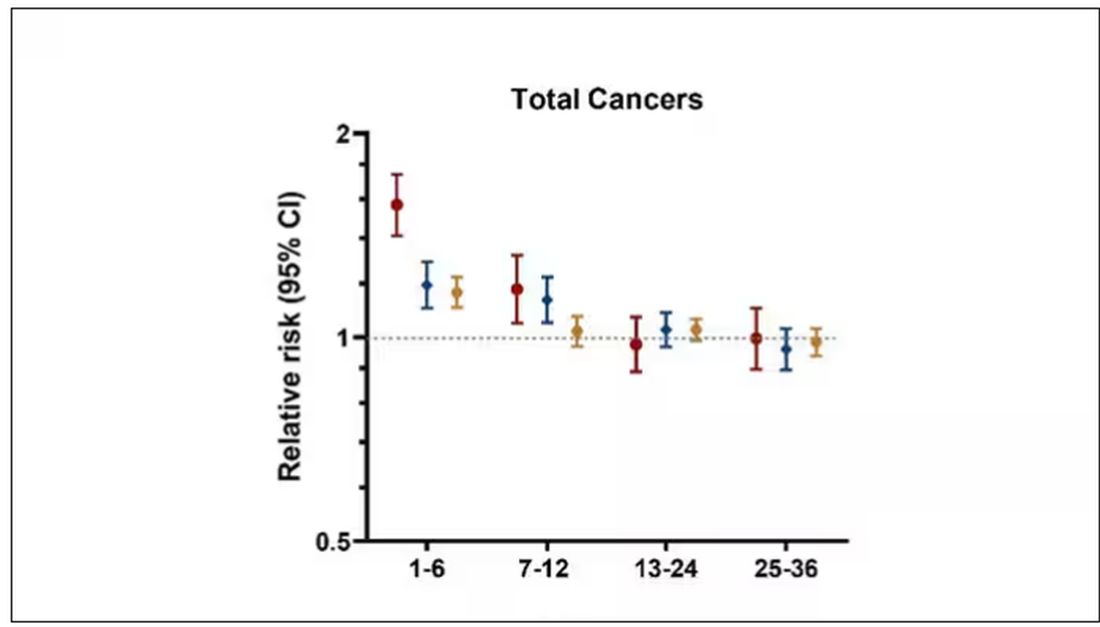

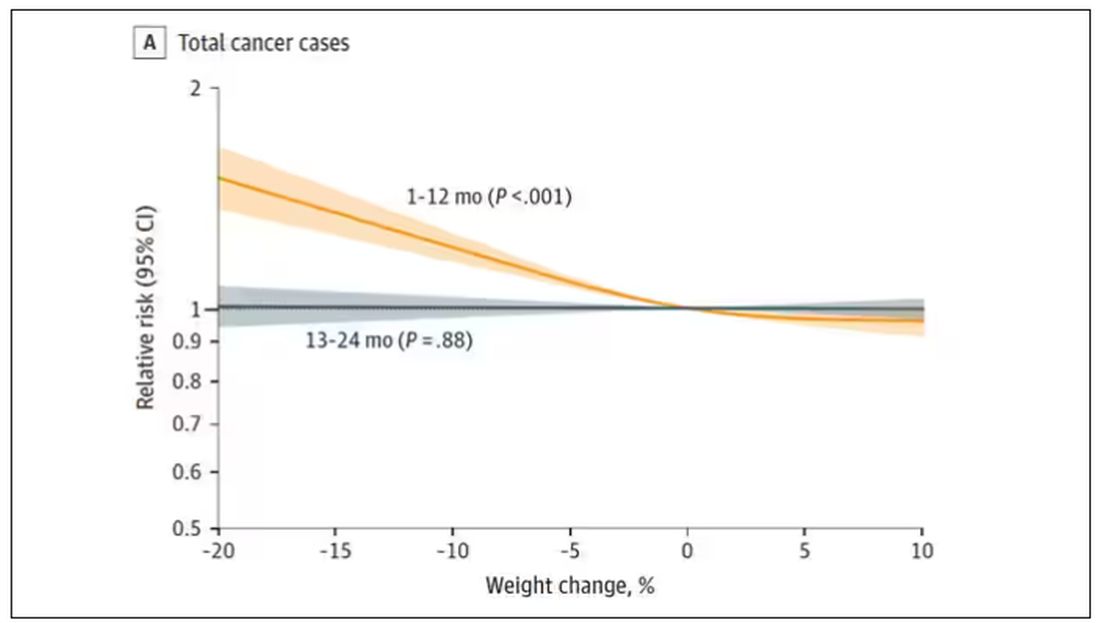

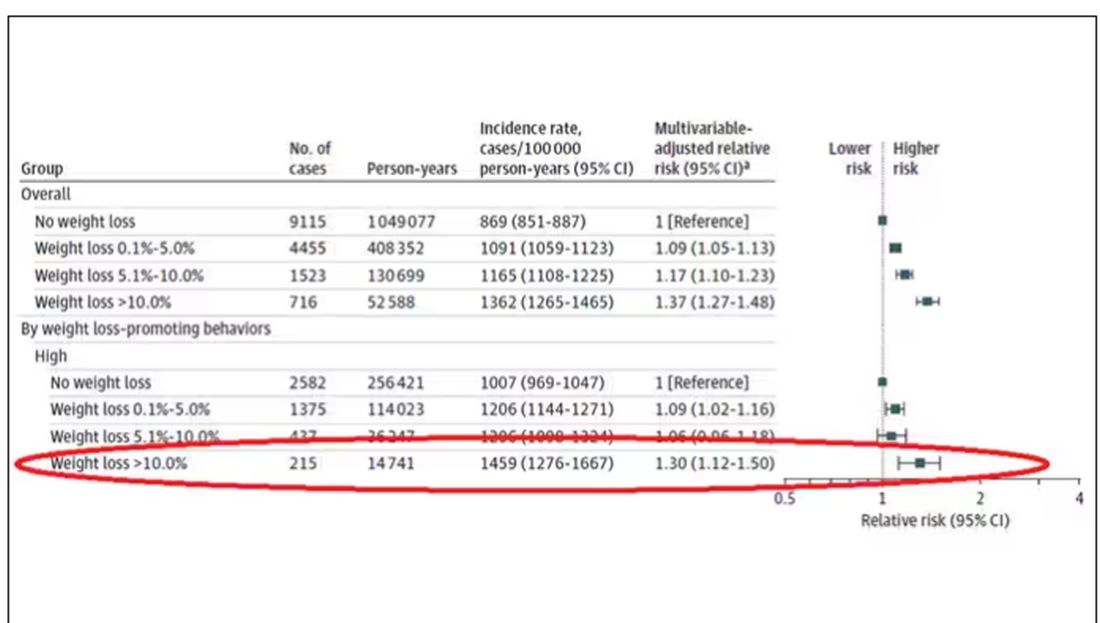

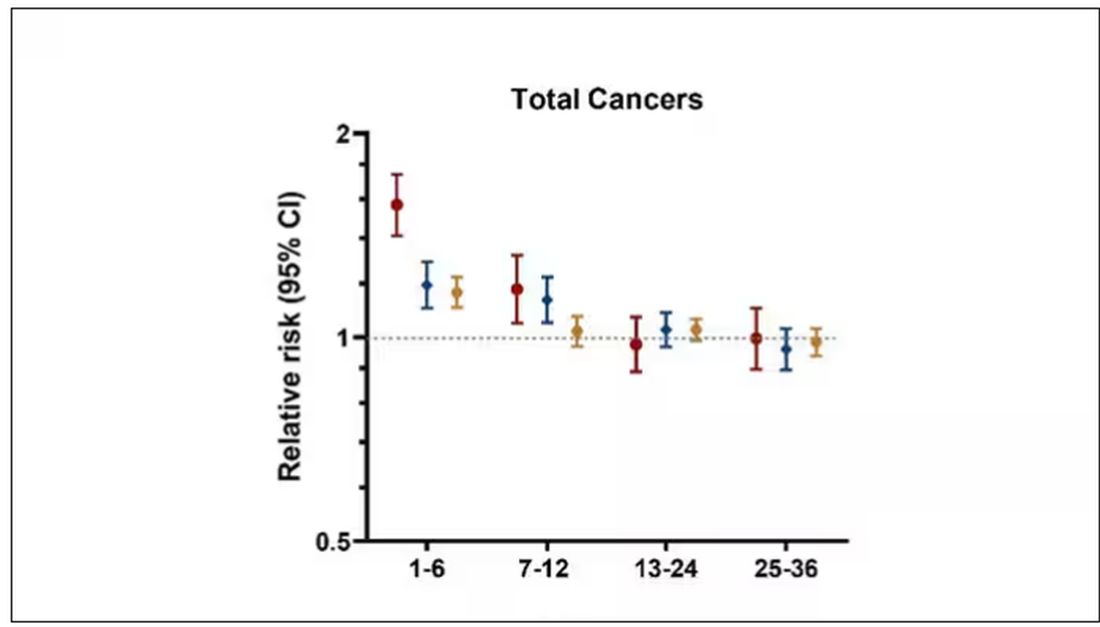

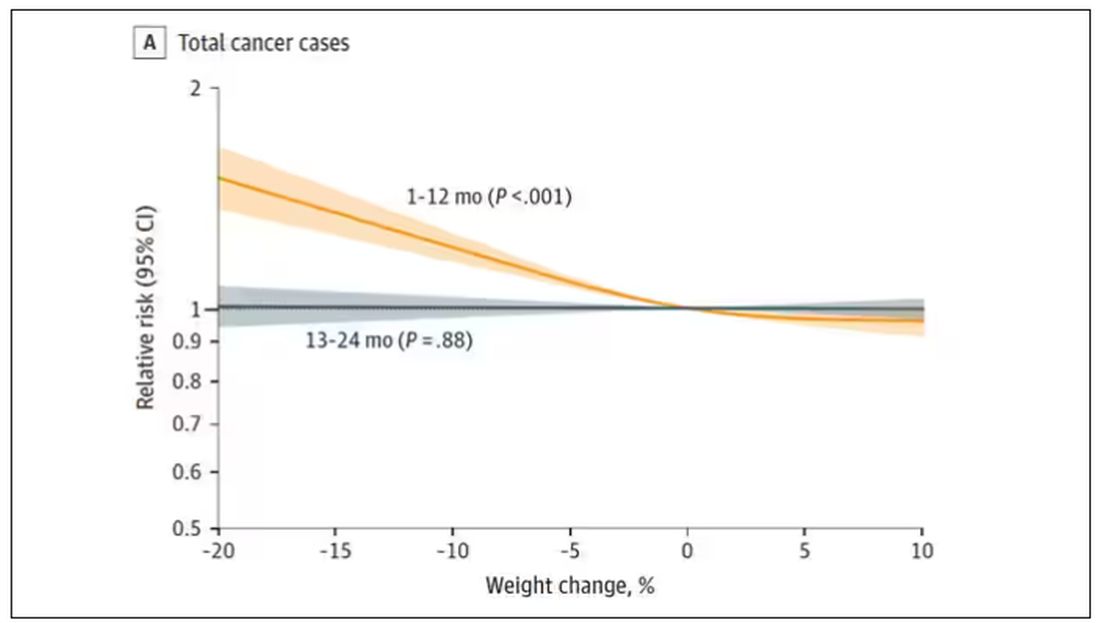

I don’t think it will surprise you to hear that individuals in the highest category of weight loss, those who lost more than 10% of their body weight over a 2-year period, had a larger risk of being diagnosed with cancer in the next year. That’s the yellow line in this graph. In fact, they had about a 40% higher risk than those who did not lose weight.

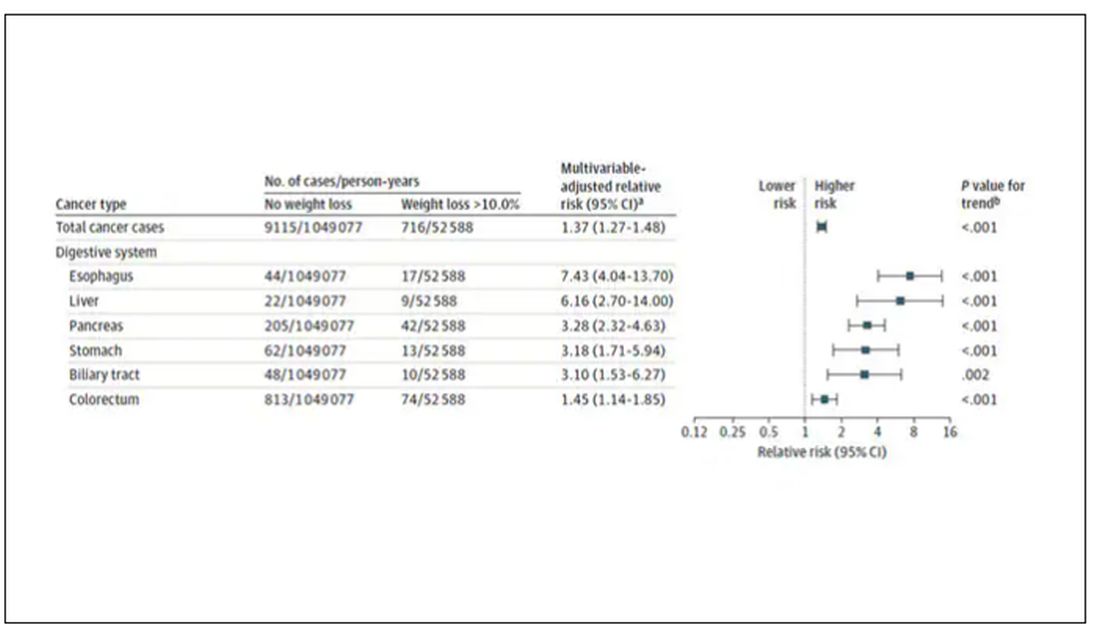

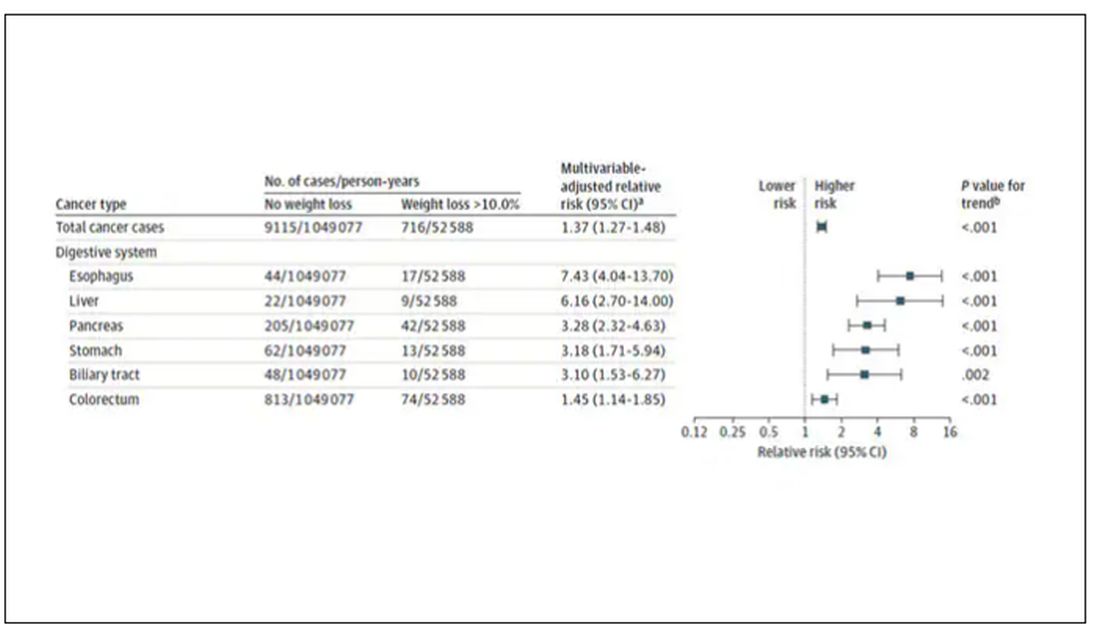

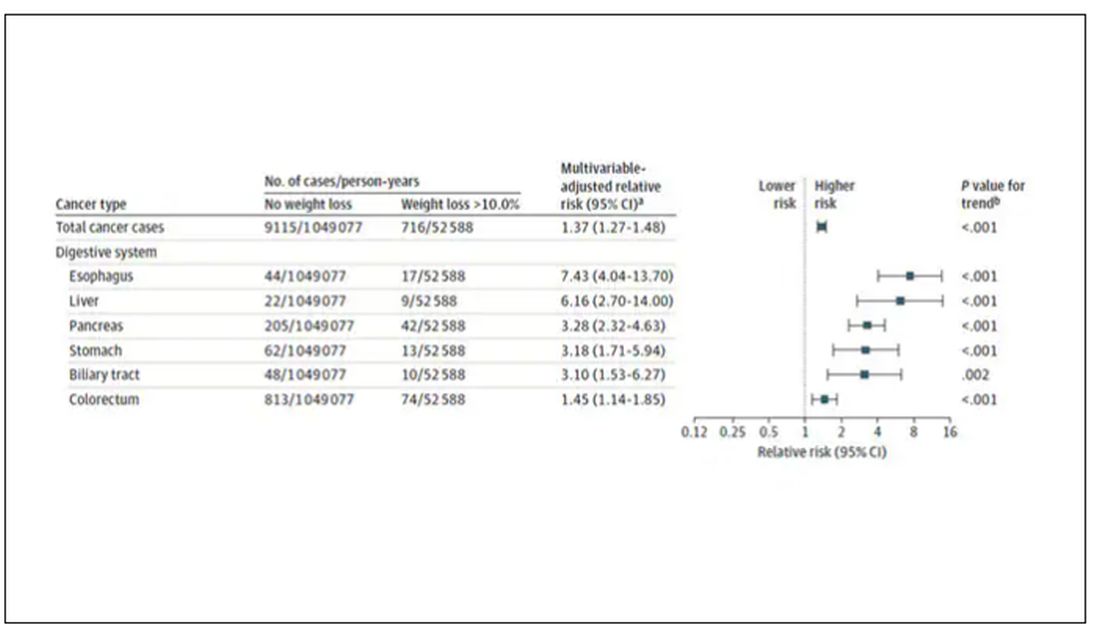

Increased risk was found across multiple cancer types, though cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, not surprisingly, were most strongly associated with antecedent weight loss.

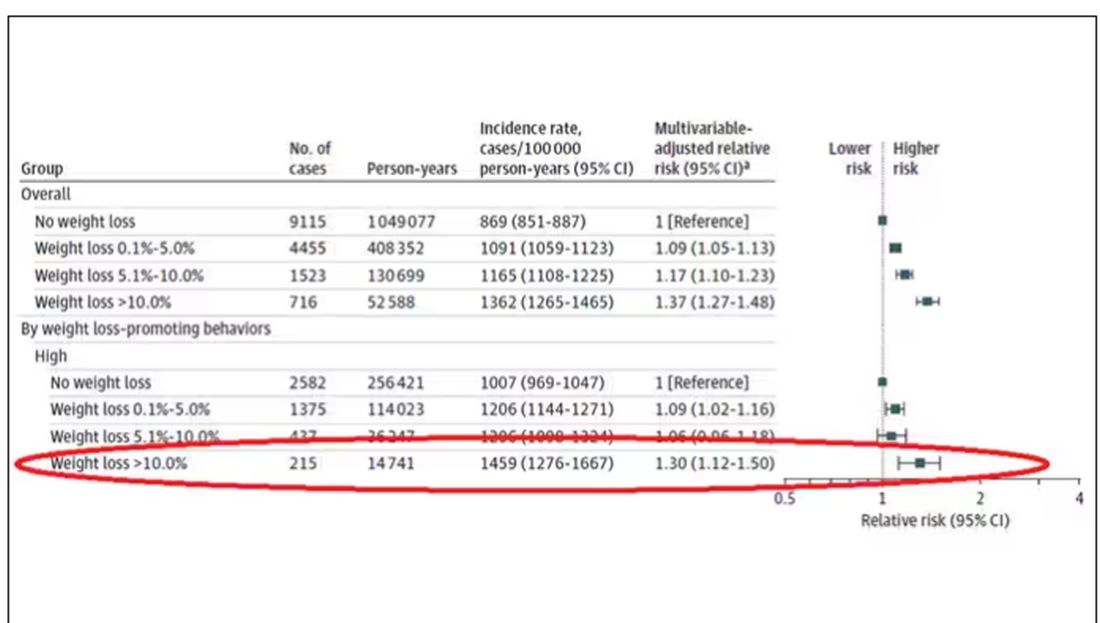

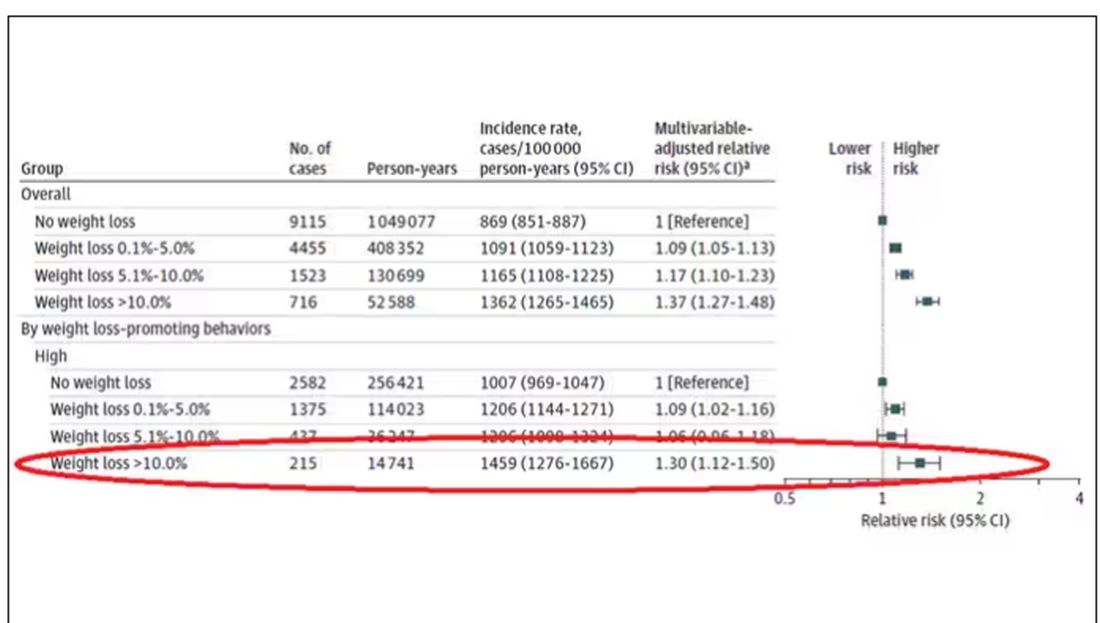

What about intentionality of weight loss? Unfortunately, the surveys did not ask participants whether they were trying to lose weight. Rather, the surveys asked about exercise and dietary habits. The researchers leveraged these responses to create three categories of participants: those who seemed to be trying to lose weight (defined as people who had increased their exercise and dietary quality); those who didn’t seem to be trying to lose weight (they changed neither exercise nor dietary behaviors); and a middle group, which changed one or the other of these behaviors but not both.

Let’s look at those who really seemed to be trying to lose weight. Over 2 years, they got more exercise and improved their diet.

If they succeeded in losing 10% or more of their body weight, they still had a higher risk for cancer than those who had not lost weight — about 30% higher, which is not that different from the 40% increased risk when you include those folks who weren’t changing their lifestyle.

This is why this study is important. The classic teaching is that unintentional weight loss is a bad thing and needs a workup. That’s fine. But we live in a world where perhaps the majority of people are, at any given time, trying to lose weight.

We need to be careful here. I am not by any means trying to say that people who have successfully lost weight have cancer. Both of the following statements can be true:

Significant weight loss, whether intentional or not, is associated with a higher risk for cancer.

Most people with significant weight loss will not have cancer.

Both of these can be true because cancer is, fortunately, rare. Of people who lose weight, the vast majority will lose weight because they are engaging in healthier behaviors. A small number may lose weight because something else is wrong. It’s just hard to tell the two apart.

Out of the nearly 200,000 people in this study, only around 16,000 developed cancer during follow-up. Again, although the chance of having cancer is slightly higher if someone has experienced weight loss, the chance is still very low.

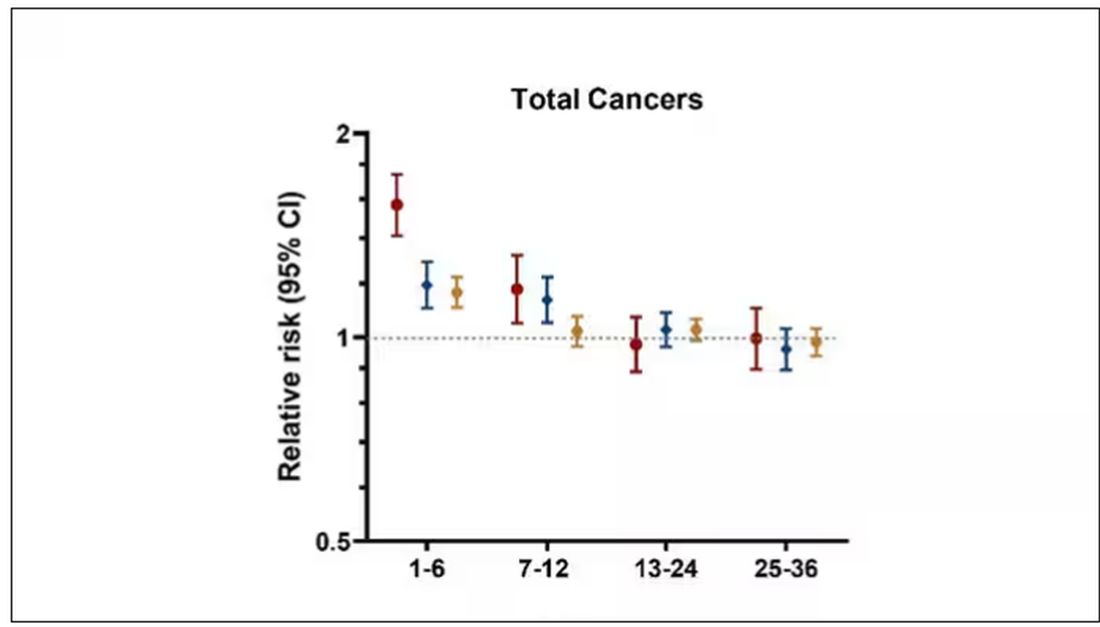

We also need to avoid suggesting that weight loss causes cancer. Some people lose weight because of an existing, as of yet undiagnosed cancer and its metabolic effects. This is borne out if you look at the risk of being diagnosed with cancer as you move further away from the interval of weight loss.

The further you get from the year of that 10% weight loss, the less likely you are to be diagnosed with cancer. Most of these cancers are diagnosed within a year of losing weight. In other words, if you’re reading this and getting worried that you lost weight 10 years ago, you’re probably out of the woods. That was, most likely, just you getting healthier.

Last thing: We have methods for weight loss now that are way more effective than diet or exercise. I’m looking at you, Ozempic. But aside from the weight loss wonder drugs, we have surgery and other interventions. This study did not capture any of that data. Ozempic wasn’t even on the market during this study, so we can’t say anything about the relationship between weight loss and cancer among people using nonlifestyle mechanisms to lose weight.

It’s a complicated system. But the clinically actionable point here is to notice if patients have lost weight. If they’ve lost it without trying, further workup is reasonable. If they’ve lost it but were trying to lose it, tell them “good job.” And consider a workup anyway.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As anyone who has been through medical training will tell you, some little scenes just stick with you. I had been seeing a patient in our resident clinic in West Philly for a couple of years. She was in her mid-60s with diabetes and hypertension and a distant smoking history. She was overweight and had been trying to improve her diet and lose weight since I started seeing her. One day she came in and was delighted to report that she had finally started shedding some pounds — about 15 in the past 2 months.

I enthusiastically told my preceptor that my careful dietary counseling had finally done the job. She looked through the chart for a moment and asked, “Is she up to date on her cancer screening?” A workup revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. The patient did well, actually, but the story stuck with me.

The textbooks call it “unintentional weight loss,” often in big, scary letters, and every doctor will go just a bit pale if a patient tells them that, despite efforts not to, they are losing weight. But true unintentional weight loss is not that common. After all, most of us are at least half-heartedly trying to lose weight all the time. Should doctors be worried when we are successful?

A new study suggests that perhaps they should. We’re talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, which combined participants from two long-running observational cohorts: 120,000 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, and 50,000 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. (These cohorts started in the 1970s and 1980s, so we’ll give them a pass on the gender-specific study designs.)

The rationale of enrolling healthcare providers in these cohort studies is that they would be reliable witnesses of their own health status. If a nurse or doctor says they have pancreatic cancer, it’s likely that they truly have pancreatic cancer. Detailed health surveys were distributed to the participants every other year, and the average follow-up was more than a decade.

Participants recorded their weight — as an aside, a nested study found that self-reported rate was extremely well correlated with professionally measured weight — and whether they had received a cancer diagnosis since the last survey.

This allowed researchers to look at the phenomenon described above. Would weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer? And, more interestingly, would intentional weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer.

I don’t think it will surprise you to hear that individuals in the highest category of weight loss, those who lost more than 10% of their body weight over a 2-year period, had a larger risk of being diagnosed with cancer in the next year. That’s the yellow line in this graph. In fact, they had about a 40% higher risk than those who did not lose weight.

Increased risk was found across multiple cancer types, though cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, not surprisingly, were most strongly associated with antecedent weight loss.

What about intentionality of weight loss? Unfortunately, the surveys did not ask participants whether they were trying to lose weight. Rather, the surveys asked about exercise and dietary habits. The researchers leveraged these responses to create three categories of participants: those who seemed to be trying to lose weight (defined as people who had increased their exercise and dietary quality); those who didn’t seem to be trying to lose weight (they changed neither exercise nor dietary behaviors); and a middle group, which changed one or the other of these behaviors but not both.

Let’s look at those who really seemed to be trying to lose weight. Over 2 years, they got more exercise and improved their diet.

If they succeeded in losing 10% or more of their body weight, they still had a higher risk for cancer than those who had not lost weight — about 30% higher, which is not that different from the 40% increased risk when you include those folks who weren’t changing their lifestyle.

This is why this study is important. The classic teaching is that unintentional weight loss is a bad thing and needs a workup. That’s fine. But we live in a world where perhaps the majority of people are, at any given time, trying to lose weight.

We need to be careful here. I am not by any means trying to say that people who have successfully lost weight have cancer. Both of the following statements can be true:

Significant weight loss, whether intentional or not, is associated with a higher risk for cancer.

Most people with significant weight loss will not have cancer.

Both of these can be true because cancer is, fortunately, rare. Of people who lose weight, the vast majority will lose weight because they are engaging in healthier behaviors. A small number may lose weight because something else is wrong. It’s just hard to tell the two apart.

Out of the nearly 200,000 people in this study, only around 16,000 developed cancer during follow-up. Again, although the chance of having cancer is slightly higher if someone has experienced weight loss, the chance is still very low.

We also need to avoid suggesting that weight loss causes cancer. Some people lose weight because of an existing, as of yet undiagnosed cancer and its metabolic effects. This is borne out if you look at the risk of being diagnosed with cancer as you move further away from the interval of weight loss.

The further you get from the year of that 10% weight loss, the less likely you are to be diagnosed with cancer. Most of these cancers are diagnosed within a year of losing weight. In other words, if you’re reading this and getting worried that you lost weight 10 years ago, you’re probably out of the woods. That was, most likely, just you getting healthier.

Last thing: We have methods for weight loss now that are way more effective than diet or exercise. I’m looking at you, Ozempic. But aside from the weight loss wonder drugs, we have surgery and other interventions. This study did not capture any of that data. Ozempic wasn’t even on the market during this study, so we can’t say anything about the relationship between weight loss and cancer among people using nonlifestyle mechanisms to lose weight.

It’s a complicated system. But the clinically actionable point here is to notice if patients have lost weight. If they’ve lost it without trying, further workup is reasonable. If they’ve lost it but were trying to lose it, tell them “good job.” And consider a workup anyway.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As anyone who has been through medical training will tell you, some little scenes just stick with you. I had been seeing a patient in our resident clinic in West Philly for a couple of years. She was in her mid-60s with diabetes and hypertension and a distant smoking history. She was overweight and had been trying to improve her diet and lose weight since I started seeing her. One day she came in and was delighted to report that she had finally started shedding some pounds — about 15 in the past 2 months.

I enthusiastically told my preceptor that my careful dietary counseling had finally done the job. She looked through the chart for a moment and asked, “Is she up to date on her cancer screening?” A workup revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. The patient did well, actually, but the story stuck with me.

The textbooks call it “unintentional weight loss,” often in big, scary letters, and every doctor will go just a bit pale if a patient tells them that, despite efforts not to, they are losing weight. But true unintentional weight loss is not that common. After all, most of us are at least half-heartedly trying to lose weight all the time. Should doctors be worried when we are successful?

A new study suggests that perhaps they should. We’re talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, which combined participants from two long-running observational cohorts: 120,000 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, and 50,000 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. (These cohorts started in the 1970s and 1980s, so we’ll give them a pass on the gender-specific study designs.)

The rationale of enrolling healthcare providers in these cohort studies is that they would be reliable witnesses of their own health status. If a nurse or doctor says they have pancreatic cancer, it’s likely that they truly have pancreatic cancer. Detailed health surveys were distributed to the participants every other year, and the average follow-up was more than a decade.

Participants recorded their weight — as an aside, a nested study found that self-reported rate was extremely well correlated with professionally measured weight — and whether they had received a cancer diagnosis since the last survey.

This allowed researchers to look at the phenomenon described above. Would weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer? And, more interestingly, would intentional weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer.

I don’t think it will surprise you to hear that individuals in the highest category of weight loss, those who lost more than 10% of their body weight over a 2-year period, had a larger risk of being diagnosed with cancer in the next year. That’s the yellow line in this graph. In fact, they had about a 40% higher risk than those who did not lose weight.

Increased risk was found across multiple cancer types, though cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, not surprisingly, were most strongly associated with antecedent weight loss.

What about intentionality of weight loss? Unfortunately, the surveys did not ask participants whether they were trying to lose weight. Rather, the surveys asked about exercise and dietary habits. The researchers leveraged these responses to create three categories of participants: those who seemed to be trying to lose weight (defined as people who had increased their exercise and dietary quality); those who didn’t seem to be trying to lose weight (they changed neither exercise nor dietary behaviors); and a middle group, which changed one or the other of these behaviors but not both.

Let’s look at those who really seemed to be trying to lose weight. Over 2 years, they got more exercise and improved their diet.

If they succeeded in losing 10% or more of their body weight, they still had a higher risk for cancer than those who had not lost weight — about 30% higher, which is not that different from the 40% increased risk when you include those folks who weren’t changing their lifestyle.

This is why this study is important. The classic teaching is that unintentional weight loss is a bad thing and needs a workup. That’s fine. But we live in a world where perhaps the majority of people are, at any given time, trying to lose weight.

We need to be careful here. I am not by any means trying to say that people who have successfully lost weight have cancer. Both of the following statements can be true:

Significant weight loss, whether intentional or not, is associated with a higher risk for cancer.

Most people with significant weight loss will not have cancer.

Both of these can be true because cancer is, fortunately, rare. Of people who lose weight, the vast majority will lose weight because they are engaging in healthier behaviors. A small number may lose weight because something else is wrong. It’s just hard to tell the two apart.

Out of the nearly 200,000 people in this study, only around 16,000 developed cancer during follow-up. Again, although the chance of having cancer is slightly higher if someone has experienced weight loss, the chance is still very low.

We also need to avoid suggesting that weight loss causes cancer. Some people lose weight because of an existing, as of yet undiagnosed cancer and its metabolic effects. This is borne out if you look at the risk of being diagnosed with cancer as you move further away from the interval of weight loss.

The further you get from the year of that 10% weight loss, the less likely you are to be diagnosed with cancer. Most of these cancers are diagnosed within a year of losing weight. In other words, if you’re reading this and getting worried that you lost weight 10 years ago, you’re probably out of the woods. That was, most likely, just you getting healthier.

Last thing: We have methods for weight loss now that are way more effective than diet or exercise. I’m looking at you, Ozempic. But aside from the weight loss wonder drugs, we have surgery and other interventions. This study did not capture any of that data. Ozempic wasn’t even on the market during this study, so we can’t say anything about the relationship between weight loss and cancer among people using nonlifestyle mechanisms to lose weight.

It’s a complicated system. But the clinically actionable point here is to notice if patients have lost weight. If they’ve lost it without trying, further workup is reasonable. If they’ve lost it but were trying to lose it, tell them “good job.” And consider a workup anyway.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

More Cardiologists Failing the Boards: Why and How to Fix?

Recent evidence suggests that more cardiologists are failing to pass their boards. , experts said.

Among the 1061 candidates who took their first American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) cardiovascular (CV) disease exam in 2022, about 80 fellows failed who might have passed had they trained in 2016-2019, according to Anis John Kadado, MD, University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate Campus, Springfield, Massachusetts, and colleagues, writing in a viewpoint article published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“The purpose of board examinations is to test the knowledge, core concepts, and fundamental principles of trainees as they deliver patient care,” said Dr. Kadado. “The decline in CV board pass rates reflects a potential gap in training, which may translate to suboptimal patient care.”

Why the Downturn?

Reasons for the increased failures are likely multifactorial, Dr. Kadado said. While some blame the ABIM, the exam has remained about the same over the past 6 years, so the test itself seems unlikely to explain the decline.

The main culprit, according to the viewpoint authors, is “the educational fallout from the disruptions caused by changes made in response to the COVID pandemic.” Changes that Dr. Kadado and colleagues said put the current class of graduating fellows at “high risk” of failing their boards in the fall.

The typical cardiology fellowship is 3 years or more for subspecialty training. Candidates who took the ABIM exam in 2021 had 18 months of training that overlapped with the pandemic response, and those who took the exam in 2022 had about 30 months of training disrupted by COVID. However, fellows who first took the exam in 2023 had essentially 36 months of training affected by COVID, potentially reducing their odds of passing.

“It is hard, if not impossible, to understand the driving forces for this recent decrease in performance on the initial ABIM certification examination, nor is it possible to forecast if there will be an end to this slide,” Jeffrey T. Kuvin, MD, chair of cardiology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York, and colleagues wrote in response to the viewpoint article.

The authors acknowledged that COVID disrupted graduate medical training and that the long-term effects of the disruption are now emerging. However, they also pinpoint other potential issues affecting fellows, including information/technology overload, a focus on patient volume over education, lack of attention to core concepts, and, as Dr. Kadado and colleagues noted, high burnout rates among fellows and knowledge gaps due to easy access to electronic resources rather than reading and studying to retain information.

COVID disruptions included limits on in-person learning, clinic exposure, research opportunities, and conference travel, according to the authors. From a 2020 viewpoint, Dr. Kuvin also noted the loss of bedside teaching and on-site grand rounds.

Furthermore, with deferrals of elective cardiac, endovascular, and structural catheterization procedures during the pandemic, elective cases normally done by fellows were postponed or canceled.

Restoring Education, Board Passing Rates

“Having recently passed the ABIM cardiovascular board exam myself, my take-home message at this point is for current fellows-in-training to remain organized, track training milestones, and foresee any training shortcomings,” Dr. Kadado said. Adding that fellows, graduates and leadership should “identify deficiencies and work on overcoming them.”

The viewpoint authors suggested strategies that fellowship leadership can use. These include:

- Regularly assessing faculty emotional well-being and burnout to ensure that they are engaged in meaningful teaching activities

- Emphasizing in-person learning, meaningful participation in conferences, and faculty oversight

- Encouraging fellows to pursue “self-directed learning” during off-hours

- Developing and implementing checklists, competency-based models, curricula, and rotations to ensure that training milestones are being met

- Returning to in-person imaging interpretation for imaging modalities such as echocardiography, cardiac CT, and cardiac MRI

- Ensuring that fellows take the American College of Cardiology in-training examination

- Providing practice question banks so that fellows can assess their knowledge gaps

“This might also be an opportune time to assess the assessment,” Dr. Kuvin and colleagues noted. “There are likely alternative or additional approaches that could provide a more comprehensive, modern tool to gauge clinical competence in a supportive manner.”

They suggested that these tools could include assessment by simulation for interventional cardiology and electrophysiology, oral case reviews, objective structured clinical exams, and evaluations of nonclinical competencies such as professionalism and health equity.

Implications for the New Cardiology Board

While the ABIM cardiology board exam days may be numbered, board certification via some type of exam process is not going away.

The American College of Cardiology and four other US CV societies — the American Heart Association, the Heart Failure Society of America, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions — formally announced in September that they have joined forces to propose a new professional certification board called the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine (ABCVM). The application to the ABMS for a separate cardiology board is still ongoing and will take time.

An initial certification exam would still be required after fellowship training, but the maintenance of certification process would be completely restructured.

Preparing for the new board will likely be “largely the same” as for the ABIM board, Dr. Kadado said. “This includes access to practice question banks, faculty oversight, strong clinical exposure and practice, regular didactic sessions, and self-directed learning.”

“Passing the board exam is just one step in our ongoing journey as a cardiologist,” he added. “Our field is rapidly evolving, and continuous learning and adaptation are part of the very essence of being a healthcare professional.”

Dr. Kadado had no relevant relationships to disclose. Dr. Kuvin is an ACC trustee and has been heading up the working group to develop the ABCVM.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Recent evidence suggests that more cardiologists are failing to pass their boards. , experts said.

Among the 1061 candidates who took their first American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) cardiovascular (CV) disease exam in 2022, about 80 fellows failed who might have passed had they trained in 2016-2019, according to Anis John Kadado, MD, University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate Campus, Springfield, Massachusetts, and colleagues, writing in a viewpoint article published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“The purpose of board examinations is to test the knowledge, core concepts, and fundamental principles of trainees as they deliver patient care,” said Dr. Kadado. “The decline in CV board pass rates reflects a potential gap in training, which may translate to suboptimal patient care.”

Why the Downturn?

Reasons for the increased failures are likely multifactorial, Dr. Kadado said. While some blame the ABIM, the exam has remained about the same over the past 6 years, so the test itself seems unlikely to explain the decline.

The main culprit, according to the viewpoint authors, is “the educational fallout from the disruptions caused by changes made in response to the COVID pandemic.” Changes that Dr. Kadado and colleagues said put the current class of graduating fellows at “high risk” of failing their boards in the fall.

The typical cardiology fellowship is 3 years or more for subspecialty training. Candidates who took the ABIM exam in 2021 had 18 months of training that overlapped with the pandemic response, and those who took the exam in 2022 had about 30 months of training disrupted by COVID. However, fellows who first took the exam in 2023 had essentially 36 months of training affected by COVID, potentially reducing their odds of passing.

“It is hard, if not impossible, to understand the driving forces for this recent decrease in performance on the initial ABIM certification examination, nor is it possible to forecast if there will be an end to this slide,” Jeffrey T. Kuvin, MD, chair of cardiology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York, and colleagues wrote in response to the viewpoint article.

The authors acknowledged that COVID disrupted graduate medical training and that the long-term effects of the disruption are now emerging. However, they also pinpoint other potential issues affecting fellows, including information/technology overload, a focus on patient volume over education, lack of attention to core concepts, and, as Dr. Kadado and colleagues noted, high burnout rates among fellows and knowledge gaps due to easy access to electronic resources rather than reading and studying to retain information.

COVID disruptions included limits on in-person learning, clinic exposure, research opportunities, and conference travel, according to the authors. From a 2020 viewpoint, Dr. Kuvin also noted the loss of bedside teaching and on-site grand rounds.

Furthermore, with deferrals of elective cardiac, endovascular, and structural catheterization procedures during the pandemic, elective cases normally done by fellows were postponed or canceled.

Restoring Education, Board Passing Rates

“Having recently passed the ABIM cardiovascular board exam myself, my take-home message at this point is for current fellows-in-training to remain organized, track training milestones, and foresee any training shortcomings,” Dr. Kadado said. Adding that fellows, graduates and leadership should “identify deficiencies and work on overcoming them.”

The viewpoint authors suggested strategies that fellowship leadership can use. These include:

- Regularly assessing faculty emotional well-being and burnout to ensure that they are engaged in meaningful teaching activities

- Emphasizing in-person learning, meaningful participation in conferences, and faculty oversight

- Encouraging fellows to pursue “self-directed learning” during off-hours

- Developing and implementing checklists, competency-based models, curricula, and rotations to ensure that training milestones are being met

- Returning to in-person imaging interpretation for imaging modalities such as echocardiography, cardiac CT, and cardiac MRI

- Ensuring that fellows take the American College of Cardiology in-training examination

- Providing practice question banks so that fellows can assess their knowledge gaps

“This might also be an opportune time to assess the assessment,” Dr. Kuvin and colleagues noted. “There are likely alternative or additional approaches that could provide a more comprehensive, modern tool to gauge clinical competence in a supportive manner.”

They suggested that these tools could include assessment by simulation for interventional cardiology and electrophysiology, oral case reviews, objective structured clinical exams, and evaluations of nonclinical competencies such as professionalism and health equity.

Implications for the New Cardiology Board

While the ABIM cardiology board exam days may be numbered, board certification via some type of exam process is not going away.

The American College of Cardiology and four other US CV societies — the American Heart Association, the Heart Failure Society of America, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions — formally announced in September that they have joined forces to propose a new professional certification board called the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine (ABCVM). The application to the ABMS for a separate cardiology board is still ongoing and will take time.

An initial certification exam would still be required after fellowship training, but the maintenance of certification process would be completely restructured.

Preparing for the new board will likely be “largely the same” as for the ABIM board, Dr. Kadado said. “This includes access to practice question banks, faculty oversight, strong clinical exposure and practice, regular didactic sessions, and self-directed learning.”

“Passing the board exam is just one step in our ongoing journey as a cardiologist,” he added. “Our field is rapidly evolving, and continuous learning and adaptation are part of the very essence of being a healthcare professional.”

Dr. Kadado had no relevant relationships to disclose. Dr. Kuvin is an ACC trustee and has been heading up the working group to develop the ABCVM.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Recent evidence suggests that more cardiologists are failing to pass their boards. , experts said.

Among the 1061 candidates who took their first American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) cardiovascular (CV) disease exam in 2022, about 80 fellows failed who might have passed had they trained in 2016-2019, according to Anis John Kadado, MD, University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate Campus, Springfield, Massachusetts, and colleagues, writing in a viewpoint article published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“The purpose of board examinations is to test the knowledge, core concepts, and fundamental principles of trainees as they deliver patient care,” said Dr. Kadado. “The decline in CV board pass rates reflects a potential gap in training, which may translate to suboptimal patient care.”

Why the Downturn?

Reasons for the increased failures are likely multifactorial, Dr. Kadado said. While some blame the ABIM, the exam has remained about the same over the past 6 years, so the test itself seems unlikely to explain the decline.

The main culprit, according to the viewpoint authors, is “the educational fallout from the disruptions caused by changes made in response to the COVID pandemic.” Changes that Dr. Kadado and colleagues said put the current class of graduating fellows at “high risk” of failing their boards in the fall.

The typical cardiology fellowship is 3 years or more for subspecialty training. Candidates who took the ABIM exam in 2021 had 18 months of training that overlapped with the pandemic response, and those who took the exam in 2022 had about 30 months of training disrupted by COVID. However, fellows who first took the exam in 2023 had essentially 36 months of training affected by COVID, potentially reducing their odds of passing.

“It is hard, if not impossible, to understand the driving forces for this recent decrease in performance on the initial ABIM certification examination, nor is it possible to forecast if there will be an end to this slide,” Jeffrey T. Kuvin, MD, chair of cardiology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York, and colleagues wrote in response to the viewpoint article.

The authors acknowledged that COVID disrupted graduate medical training and that the long-term effects of the disruption are now emerging. However, they also pinpoint other potential issues affecting fellows, including information/technology overload, a focus on patient volume over education, lack of attention to core concepts, and, as Dr. Kadado and colleagues noted, high burnout rates among fellows and knowledge gaps due to easy access to electronic resources rather than reading and studying to retain information.

COVID disruptions included limits on in-person learning, clinic exposure, research opportunities, and conference travel, according to the authors. From a 2020 viewpoint, Dr. Kuvin also noted the loss of bedside teaching and on-site grand rounds.

Furthermore, with deferrals of elective cardiac, endovascular, and structural catheterization procedures during the pandemic, elective cases normally done by fellows were postponed or canceled.

Restoring Education, Board Passing Rates

“Having recently passed the ABIM cardiovascular board exam myself, my take-home message at this point is for current fellows-in-training to remain organized, track training milestones, and foresee any training shortcomings,” Dr. Kadado said. Adding that fellows, graduates and leadership should “identify deficiencies and work on overcoming them.”

The viewpoint authors suggested strategies that fellowship leadership can use. These include:

- Regularly assessing faculty emotional well-being and burnout to ensure that they are engaged in meaningful teaching activities

- Emphasizing in-person learning, meaningful participation in conferences, and faculty oversight

- Encouraging fellows to pursue “self-directed learning” during off-hours

- Developing and implementing checklists, competency-based models, curricula, and rotations to ensure that training milestones are being met

- Returning to in-person imaging interpretation for imaging modalities such as echocardiography, cardiac CT, and cardiac MRI

- Ensuring that fellows take the American College of Cardiology in-training examination

- Providing practice question banks so that fellows can assess their knowledge gaps

“This might also be an opportune time to assess the assessment,” Dr. Kuvin and colleagues noted. “There are likely alternative or additional approaches that could provide a more comprehensive, modern tool to gauge clinical competence in a supportive manner.”

They suggested that these tools could include assessment by simulation for interventional cardiology and electrophysiology, oral case reviews, objective structured clinical exams, and evaluations of nonclinical competencies such as professionalism and health equity.

Implications for the New Cardiology Board

While the ABIM cardiology board exam days may be numbered, board certification via some type of exam process is not going away.

The American College of Cardiology and four other US CV societies — the American Heart Association, the Heart Failure Society of America, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions — formally announced in September that they have joined forces to propose a new professional certification board called the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine (ABCVM). The application to the ABMS for a separate cardiology board is still ongoing and will take time.

An initial certification exam would still be required after fellowship training, but the maintenance of certification process would be completely restructured.

Preparing for the new board will likely be “largely the same” as for the ABIM board, Dr. Kadado said. “This includes access to practice question banks, faculty oversight, strong clinical exposure and practice, regular didactic sessions, and self-directed learning.”

“Passing the board exam is just one step in our ongoing journey as a cardiologist,” he added. “Our field is rapidly evolving, and continuous learning and adaptation are part of the very essence of being a healthcare professional.”

Dr. Kadado had no relevant relationships to disclose. Dr. Kuvin is an ACC trustee and has been heading up the working group to develop the ABCVM.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Maternal Vegan Diet May Be Tied To Lower Birth Weight

Mothers on vegan diets during pregnancy may give birth to infants with lower mean birth weights than those of omnivorous mothers and may also have a greater risk of preeclampsia, a prospective study of Danish pregnant women suggests.

According to researchers led by Signe Hedegaard, MD, of the department of obstetrics and Gynecology at Rigshospitalet, Juliane Marie Center, University of Copenhagen, low protein intake may lie behind the observed association with birth weight. The report was published in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

While vegan-identifying mothers were very few in number, the authors conceded, their babies were more likely to weigh less on average than those of omnivorous mothers — 3441 g vs 3601 g — despite a mean gestation 5 days longer.

Prevalence rates of low birth weight (< 2500 g) in the two groups were 11.1% and 2.5%, respectively, and the prevalence of preeclampsia was 11.1% vs 2.6%. The mean birth weight of infants in the maternal vegan group was about 240 g lower than infants born to omnivorous mothers.

“The lower birth weight of around 240 g among vegans compared with omnivorous mothers in our study strengthens our observation that vegans may be at higher risk of giving birth to low-birth-weight infants. The observed effect size on birth weight is comparable to what is observed among daily smokers relative to nonsmokers in this cohort,“ Dr. Hedegaard and colleagues wrote. “Furthermore, the on-average 5-day longer gestation observed among vegans in our study would be indicative of reduced fetal growth rate rather than lower birth weight due to shorter gestation.”

These findings emerged from data on 66,738 pregnancies in the Danish National Birth Cohort, 1996-2002. A food frequency questionnaire characterized pregnant subjects as fish/poultry-vegetarians, lacto/ovo-vegetarians, vegans, or omnivores, based on their self-reporting in gestational week 30.

A total of 98.7% (n = 65,872) of participants were defined as omnivorous, while 1.0% (n = 666), 0.3% (n = 183), and 0.03% (n = 18) identified as fish/poultry vegetarians, lacto/ovo-vegetarians, or vegans, respectively.

Those following plant-based diets of all types were slightly older, more often parous, and less likely to smoke. This plant dietary group also had a somewhat lower prevalence of overweight and obesity (prepregnancy body mass index > 25 [kg/m2]) and a higher prevalence of underweight (prepregnancy BMI < 18.5).

Total energy intake was modestly lower from plant-based diets, for a mean difference of 0.3-0.7 MJ (72-167 kcal) per day.

As for total protein intake, this was substantially lower for lacto/ovo-vegetarians and vegans: 13.3% and 10.4% of energy, respectively, compared with 15.4% in omnivores.

Dietary intake of micronutrients was also considerably lower among vegans, but after factoring in intake from dietary supplements, no major differences emerged.

Mean birth weight, birth length, length of gestation, and rate of low birth weight (< 2500 g) were similar among omnivorous, fish/poultry-, and lacto/ovo-vegetarians. The prevalence of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and cesarean section was similar across groups, but the prevalence of anemia was higher among fish/poultry- and lacto/ovo-vegetarians than omnivorous participants.

As for preeclampsia, previous research in larger numbers of vegans found no indication of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. Some studies, however, have suggested a link between preeclampsia and low intake of protein, calcium, or vitamin D, but the evidence is inconclusive, and the mechanism is unclear.

The observed associations, however, do not translate to causality, the authors cautioned. “Future studies should put more emphasis on characterizing the diet among those adhering to vegan diets and other forms of plant-based diets during pregnancy,” they wrote. “That would allow for stronger assumptions on possible causality between any association observed with birth or pregnancy outcomes in such studies and strengthen the basis for dietary recommendations.”

This study was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research. The Danish National Birth Cohort Study is supported by the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Danish Heart Association, Danish Medical Research Council, Sygekassernes Helsefond, the Innovation Fund Denmark, and the Danish National Research Foundation. The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare.

Mothers on vegan diets during pregnancy may give birth to infants with lower mean birth weights than those of omnivorous mothers and may also have a greater risk of preeclampsia, a prospective study of Danish pregnant women suggests.

According to researchers led by Signe Hedegaard, MD, of the department of obstetrics and Gynecology at Rigshospitalet, Juliane Marie Center, University of Copenhagen, low protein intake may lie behind the observed association with birth weight. The report was published in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

While vegan-identifying mothers were very few in number, the authors conceded, their babies were more likely to weigh less on average than those of omnivorous mothers — 3441 g vs 3601 g — despite a mean gestation 5 days longer.

Prevalence rates of low birth weight (< 2500 g) in the two groups were 11.1% and 2.5%, respectively, and the prevalence of preeclampsia was 11.1% vs 2.6%. The mean birth weight of infants in the maternal vegan group was about 240 g lower than infants born to omnivorous mothers.

“The lower birth weight of around 240 g among vegans compared with omnivorous mothers in our study strengthens our observation that vegans may be at higher risk of giving birth to low-birth-weight infants. The observed effect size on birth weight is comparable to what is observed among daily smokers relative to nonsmokers in this cohort,“ Dr. Hedegaard and colleagues wrote. “Furthermore, the on-average 5-day longer gestation observed among vegans in our study would be indicative of reduced fetal growth rate rather than lower birth weight due to shorter gestation.”

These findings emerged from data on 66,738 pregnancies in the Danish National Birth Cohort, 1996-2002. A food frequency questionnaire characterized pregnant subjects as fish/poultry-vegetarians, lacto/ovo-vegetarians, vegans, or omnivores, based on their self-reporting in gestational week 30.

A total of 98.7% (n = 65,872) of participants were defined as omnivorous, while 1.0% (n = 666), 0.3% (n = 183), and 0.03% (n = 18) identified as fish/poultry vegetarians, lacto/ovo-vegetarians, or vegans, respectively.

Those following plant-based diets of all types were slightly older, more often parous, and less likely to smoke. This plant dietary group also had a somewhat lower prevalence of overweight and obesity (prepregnancy body mass index > 25 [kg/m2]) and a higher prevalence of underweight (prepregnancy BMI < 18.5).

Total energy intake was modestly lower from plant-based diets, for a mean difference of 0.3-0.7 MJ (72-167 kcal) per day.

As for total protein intake, this was substantially lower for lacto/ovo-vegetarians and vegans: 13.3% and 10.4% of energy, respectively, compared with 15.4% in omnivores.

Dietary intake of micronutrients was also considerably lower among vegans, but after factoring in intake from dietary supplements, no major differences emerged.

Mean birth weight, birth length, length of gestation, and rate of low birth weight (< 2500 g) were similar among omnivorous, fish/poultry-, and lacto/ovo-vegetarians. The prevalence of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and cesarean section was similar across groups, but the prevalence of anemia was higher among fish/poultry- and lacto/ovo-vegetarians than omnivorous participants.

As for preeclampsia, previous research in larger numbers of vegans found no indication of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. Some studies, however, have suggested a link between preeclampsia and low intake of protein, calcium, or vitamin D, but the evidence is inconclusive, and the mechanism is unclear.

The observed associations, however, do not translate to causality, the authors cautioned. “Future studies should put more emphasis on characterizing the diet among those adhering to vegan diets and other forms of plant-based diets during pregnancy,” they wrote. “That would allow for stronger assumptions on possible causality between any association observed with birth or pregnancy outcomes in such studies and strengthen the basis for dietary recommendations.”

This study was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research. The Danish National Birth Cohort Study is supported by the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Danish Heart Association, Danish Medical Research Council, Sygekassernes Helsefond, the Innovation Fund Denmark, and the Danish National Research Foundation. The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare.

Mothers on vegan diets during pregnancy may give birth to infants with lower mean birth weights than those of omnivorous mothers and may also have a greater risk of preeclampsia, a prospective study of Danish pregnant women suggests.

According to researchers led by Signe Hedegaard, MD, of the department of obstetrics and Gynecology at Rigshospitalet, Juliane Marie Center, University of Copenhagen, low protein intake may lie behind the observed association with birth weight. The report was published in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

While vegan-identifying mothers were very few in number, the authors conceded, their babies were more likely to weigh less on average than those of omnivorous mothers — 3441 g vs 3601 g — despite a mean gestation 5 days longer.

Prevalence rates of low birth weight (< 2500 g) in the two groups were 11.1% and 2.5%, respectively, and the prevalence of preeclampsia was 11.1% vs 2.6%. The mean birth weight of infants in the maternal vegan group was about 240 g lower than infants born to omnivorous mothers.

“The lower birth weight of around 240 g among vegans compared with omnivorous mothers in our study strengthens our observation that vegans may be at higher risk of giving birth to low-birth-weight infants. The observed effect size on birth weight is comparable to what is observed among daily smokers relative to nonsmokers in this cohort,“ Dr. Hedegaard and colleagues wrote. “Furthermore, the on-average 5-day longer gestation observed among vegans in our study would be indicative of reduced fetal growth rate rather than lower birth weight due to shorter gestation.”

These findings emerged from data on 66,738 pregnancies in the Danish National Birth Cohort, 1996-2002. A food frequency questionnaire characterized pregnant subjects as fish/poultry-vegetarians, lacto/ovo-vegetarians, vegans, or omnivores, based on their self-reporting in gestational week 30.

A total of 98.7% (n = 65,872) of participants were defined as omnivorous, while 1.0% (n = 666), 0.3% (n = 183), and 0.03% (n = 18) identified as fish/poultry vegetarians, lacto/ovo-vegetarians, or vegans, respectively.

Those following plant-based diets of all types were slightly older, more often parous, and less likely to smoke. This plant dietary group also had a somewhat lower prevalence of overweight and obesity (prepregnancy body mass index > 25 [kg/m2]) and a higher prevalence of underweight (prepregnancy BMI < 18.5).

Total energy intake was modestly lower from plant-based diets, for a mean difference of 0.3-0.7 MJ (72-167 kcal) per day.

As for total protein intake, this was substantially lower for lacto/ovo-vegetarians and vegans: 13.3% and 10.4% of energy, respectively, compared with 15.4% in omnivores.

Dietary intake of micronutrients was also considerably lower among vegans, but after factoring in intake from dietary supplements, no major differences emerged.

Mean birth weight, birth length, length of gestation, and rate of low birth weight (< 2500 g) were similar among omnivorous, fish/poultry-, and lacto/ovo-vegetarians. The prevalence of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and cesarean section was similar across groups, but the prevalence of anemia was higher among fish/poultry- and lacto/ovo-vegetarians than omnivorous participants.

As for preeclampsia, previous research in larger numbers of vegans found no indication of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. Some studies, however, have suggested a link between preeclampsia and low intake of protein, calcium, or vitamin D, but the evidence is inconclusive, and the mechanism is unclear.

The observed associations, however, do not translate to causality, the authors cautioned. “Future studies should put more emphasis on characterizing the diet among those adhering to vegan diets and other forms of plant-based diets during pregnancy,” they wrote. “That would allow for stronger assumptions on possible causality between any association observed with birth or pregnancy outcomes in such studies and strengthen the basis for dietary recommendations.”

This study was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research. The Danish National Birth Cohort Study is supported by the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Danish Heart Association, Danish Medical Research Council, Sygekassernes Helsefond, the Innovation Fund Denmark, and the Danish National Research Foundation. The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare.

FROM ACTA OBSTETRICIA ET GYNECOLOGICA SCANDINAVICA

Magnetic System May Improve Kidney Stone Removal

Kidney stones afflict approximately one in nine individuals, causing intense pain and serious infections. With over 1.3 million emergency room visits and healthcare expenditures exceeding $5 billion annually in the United States, they pose a significant health burden. Small, hard-to-extract fragments are often left behind, risking natural elimination. While technologies like focused ultrasound, fragment adhesion with biopolymers, and negative pressure aspiration have been explored, they face limitations, especially with standard ureteroscope channel sizes.

Magnetizing Renal Calculus Fragments

A published study introduced the Magnetic System for Total Nephrolith Extraction, a system designed to enhance the efficiency of renal calculus fragment removal. In this system, the stones are coated with a magnetic hydrogel and retrieved using a magnetic guidewire compatible with standard ureteroscopes.

In vitro, laser-obtained renal calculus fragments were separated by size and coated with either ferumoxytol alone or combined with chitosan (Hydrogel CF). Treated fragments were then subjected to a magnetic wire for fragment removal assessment. Additional tests included scanning electron microscopy and cell culture with human urothelial cells to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the magnetic hydrogel components. The hydrogel and its components underwent safety and efficacy evaluations in in vitro studies, human tissue samples, and murine models to assess their impact on urothelium and antibacterial properties.

Safe Fragment Removal

The Hydrogel CF, composed of ferumoxytol and chitosan, demonstrated 100% effectiveness in eliminating all tested fragments, even those measuring up to 4 mm, across various stone compositions. Particle tracing simulations indicated that small-sized stones (1 and 3 mm) could be captured several millimeters away. Scanning electron microscopy confirmed the binding of ferumoxytol and Hydrogel CF to the surface of calcium oxalate stones.

The components of Hydrogel CF did not induce significant cytotoxicity on human urothelial cells, even after a 4-hour exposure. Moreover, live mouse studies showed that Hydrogel CF caused less bladder urothelium exfoliation compared with chitosan, and the urothelium returned to normal within 12 hours. In addition, these components exhibited antibacterial properties, inhibiting the growth of uropathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis, comparable to that of ciprofloxacin.

The ability to eliminate lithiasic fragments, the absence of significant urothelial toxicity, and antibacterial activity suggest that the use of magnetic hydrogel could be integrated into laser treatments for renal stones through ureteroscopy without immediate complications. The antibacterial properties could offer potential postoperative benefits while reducing procedural time. Further animal studies are underway to assess the safety of Hydrogel CF before proceeding to human clinical trials.

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Kidney stones afflict approximately one in nine individuals, causing intense pain and serious infections. With over 1.3 million emergency room visits and healthcare expenditures exceeding $5 billion annually in the United States, they pose a significant health burden. Small, hard-to-extract fragments are often left behind, risking natural elimination. While technologies like focused ultrasound, fragment adhesion with biopolymers, and negative pressure aspiration have been explored, they face limitations, especially with standard ureteroscope channel sizes.

Magnetizing Renal Calculus Fragments

A published study introduced the Magnetic System for Total Nephrolith Extraction, a system designed to enhance the efficiency of renal calculus fragment removal. In this system, the stones are coated with a magnetic hydrogel and retrieved using a magnetic guidewire compatible with standard ureteroscopes.

In vitro, laser-obtained renal calculus fragments were separated by size and coated with either ferumoxytol alone or combined with chitosan (Hydrogel CF). Treated fragments were then subjected to a magnetic wire for fragment removal assessment. Additional tests included scanning electron microscopy and cell culture with human urothelial cells to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the magnetic hydrogel components. The hydrogel and its components underwent safety and efficacy evaluations in in vitro studies, human tissue samples, and murine models to assess their impact on urothelium and antibacterial properties.

Safe Fragment Removal

The Hydrogel CF, composed of ferumoxytol and chitosan, demonstrated 100% effectiveness in eliminating all tested fragments, even those measuring up to 4 mm, across various stone compositions. Particle tracing simulations indicated that small-sized stones (1 and 3 mm) could be captured several millimeters away. Scanning electron microscopy confirmed the binding of ferumoxytol and Hydrogel CF to the surface of calcium oxalate stones.

The components of Hydrogel CF did not induce significant cytotoxicity on human urothelial cells, even after a 4-hour exposure. Moreover, live mouse studies showed that Hydrogel CF caused less bladder urothelium exfoliation compared with chitosan, and the urothelium returned to normal within 12 hours. In addition, these components exhibited antibacterial properties, inhibiting the growth of uropathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis, comparable to that of ciprofloxacin.

The ability to eliminate lithiasic fragments, the absence of significant urothelial toxicity, and antibacterial activity suggest that the use of magnetic hydrogel could be integrated into laser treatments for renal stones through ureteroscopy without immediate complications. The antibacterial properties could offer potential postoperative benefits while reducing procedural time. Further animal studies are underway to assess the safety of Hydrogel CF before proceeding to human clinical trials.

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Kidney stones afflict approximately one in nine individuals, causing intense pain and serious infections. With over 1.3 million emergency room visits and healthcare expenditures exceeding $5 billion annually in the United States, they pose a significant health burden. Small, hard-to-extract fragments are often left behind, risking natural elimination. While technologies like focused ultrasound, fragment adhesion with biopolymers, and negative pressure aspiration have been explored, they face limitations, especially with standard ureteroscope channel sizes.

Magnetizing Renal Calculus Fragments

A published study introduced the Magnetic System for Total Nephrolith Extraction, a system designed to enhance the efficiency of renal calculus fragment removal. In this system, the stones are coated with a magnetic hydrogel and retrieved using a magnetic guidewire compatible with standard ureteroscopes.

In vitro, laser-obtained renal calculus fragments were separated by size and coated with either ferumoxytol alone or combined with chitosan (Hydrogel CF). Treated fragments were then subjected to a magnetic wire for fragment removal assessment. Additional tests included scanning electron microscopy and cell culture with human urothelial cells to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the magnetic hydrogel components. The hydrogel and its components underwent safety and efficacy evaluations in in vitro studies, human tissue samples, and murine models to assess their impact on urothelium and antibacterial properties.

Safe Fragment Removal

The Hydrogel CF, composed of ferumoxytol and chitosan, demonstrated 100% effectiveness in eliminating all tested fragments, even those measuring up to 4 mm, across various stone compositions. Particle tracing simulations indicated that small-sized stones (1 and 3 mm) could be captured several millimeters away. Scanning electron microscopy confirmed the binding of ferumoxytol and Hydrogel CF to the surface of calcium oxalate stones.

The components of Hydrogel CF did not induce significant cytotoxicity on human urothelial cells, even after a 4-hour exposure. Moreover, live mouse studies showed that Hydrogel CF caused less bladder urothelium exfoliation compared with chitosan, and the urothelium returned to normal within 12 hours. In addition, these components exhibited antibacterial properties, inhibiting the growth of uropathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis, comparable to that of ciprofloxacin.

The ability to eliminate lithiasic fragments, the absence of significant urothelial toxicity, and antibacterial activity suggest that the use of magnetic hydrogel could be integrated into laser treatments for renal stones through ureteroscopy without immediate complications. The antibacterial properties could offer potential postoperative benefits while reducing procedural time. Further animal studies are underway to assess the safety of Hydrogel CF before proceeding to human clinical trials.

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Will New Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines Save More Lives?

When the American Cancer Society recently unveiled changes to its lung cancer screening guidance, the aim was to remove barriers to screening and catch more cancers in high-risk people earlier.

Although the lung cancer death rate has declined significantly over the past few decades, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.

Detecting lung cancer early is key to improving survival. Still, lung cancer screening rates are poor. In 2021, the American Lung Association estimated that 14 million US adults qualified for lung cancer screening, but only 5.8% received it.

Smokers or former smokers without symptoms may forgo regular screening and only receive their screening scan after symptoms emerge, explained Janani S. Reisenauer, MD, Division Chair of Thoracic Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. But by the time symptoms develop, the cancer is typically more advanced, and treatment options become more limited.

The goal of the new American Cancer Society guidelines, published in early November 2023 in CA: A Cancer Journal for Physicians, is to identify lung cancers at earlier stages when they are easier to treat.

Almost 5 million more high-risk people will now qualify for regular lung cancer screening, the guideline authors estimated.

But will expanding screening help reduce deaths from lung cancer? And perhaps just as important, will the guidelines move the needle on the “disappointingly low” lung cancer screening rates up to this point?

“I definitely think it’s a step in the right direction,” said Lecia V. Sequist, MD, MPH, clinical researcher and lung cancer medical oncologist, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston, Massachusetts.

The new guidelines lowered the age for annual lung cancer screening among asymptomatic former or current smokers from 55-74 years to 50-80 years. The update also now considers a high-risk person anyone with a 20-pack-year history, down from a 30-pack-year history, and removes the requirement that former smokers must have quit within 15 years to be eligible for screening.

As people age, their risk for lung cancer increases, so it makes sense to screen all former smokers regardless of when they quit, explained Kim Lori Sandler, MD, from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, and cochair of the American College of Radiology’s Lung Cancer Screening Steering Committee.

“There’s really nothing magical or drastic that happens at the 15-year mark,” Dr. Sequist agreed. For “someone who quit 14 years ago versus 16 years ago, it is essentially the same risk, and so scientifically it doesn’t really make sense to impose an artificial cut-off where no change in risk exists.”

The latest evidence reviewed in the new guidelines shows that expanding the guidelines would identify more early-stage cancers and potentially save lives. The authors modeled the benefits and harms of lung cancer screening using several scenarios.

Moving the start age from 55 to 50 years would lead to a 15% reduction in lung cancer mortality in men aged 50-54 years, the model suggested.

Removing the 15-year timeline for quitting smoking also would also improve outcomes. Compared with scenarios that included the 15-year quit timeline for former smokers, those that removed the limit would result in a 37.3% increase in screening exams, a 21% increase in would avert lung cancer deaths, and offer a 19% increase in life-years gained per 100,000 population.

Overall, the evidence indicates that, “if fully implemented, these recommendations have a high likelihood of significantly reducing death and suffering from lung cancer in the United States,” the guideline authors wrote.

But screening more people also comes with risks, such as more false-positive findings, which could lead to extra scans, invasive tests for tissue sampling, or even procedures for benign disease, Dr. Sandler explained. The latter “is what we really need to avoid.”

Even so, Dr. Sandler believes the current guidelines show that the benefit of screening “is great enough that it’s worth including these additional individuals.”

Guidelines Are Not Enough

But will expanding the screening criteria prompt more eligible individuals to receive their CT scans?

Simply expanding the eligibility criteria, by itself, likely won’t measurably improve screening uptake, said Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, of Stony Brook Cancer Center, Stony Brook, New York.

Healthcare and insurance access along with patient demand may present the most significant barriers to improving screening uptake.

The “issue is not the guideline as much as it’s the healthcare system,” said Otis W. Brawley, MD, professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Access to screening at hospitals with limited CT scanners and staff could present one major issue.

When Dr. Brawley worked at a large inner-city safety net hospital in Atlanta, patients with lung cancer frequently had to wait over a week to use one of the four CT scanners, he recalled. Adding to these delays, we didn’t have enough people to read the screens or enough people to do the diagnostics for those who had abnormalities, said Dr. Brawley.

To increase lung cancer screening in this context would increase the wait time for patients who do have cancer, he said.

Insurance coverage could present a roadblock for some as well. While the 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations largely align with the new ones from the American Cancer Society, there’s one key difference: The USPSTF still requires former smokers to have quit within 15 years to be eligible for annual screening.

Because the USPSTF recommendations dictate insurance coverage, some former smokers — those who quit more than 15 years ago — may not qualify for coverage and would have to pay out-of-pocket for screening.

Dr. Sequist, however, had a more optimistic outlook about screening uptake.

The American Cancer Society guidelines should remove some of the stigma surrounding lung cancer screening. Most people, when asked a lot of questions about their tobacco use and history, tend to downplay it because there’s shame associated with smoking, Dr. Sequist said. The new guidelines limit the information needed to determine eligibility.

Dr. Sequist also noted that the updated American Cancer Society guideline would improve screening rates because it simplifies the eligibility criteria and makes it easier for physicians to determine who qualifies.

The issue, however, is that some of these individuals — those who quit over 15 years ago — may not have their scan covered by insurance, which could preclude lower-income individuals from getting screened.

The American Cancer Society guidelines” do not necessarily translate into a change in policy,” which is “dictated by the USPSTF and payors such as Medicare,” explained Peter Mazzone, MD, MPH, director of the Lung Cancer Program and Lung Cancer Screening Program for the Respiratory Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

On the patient side, Dr. Brawley noted, “we don’t yet have a large demand” for screening.

Many current and former smokers may put off lung cancer screening or not seek it out. Some may be unaware of their eligibility, while others may fear the outcome of a scan. Even among eligible individuals who do receive an initial scan, most — more than 75% — do not return for their next scan a year later, research showed.

Enhancing patient education and launching strong marketing campaigns would be a key element to encourage more people to get their annual screening and reduce the stigma associated with lung cancer as a smoker’s disease.

“Primary care physicians are integral in ensuring all eligible patients receive appropriate screening for lung cancer,” said Steven P. Furr, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a family physician in Jackson, Alabama. “It is imperative that family physicians encourage screening in at-risk patients and counsel them on the importance of continued screening, as well as smoking cessation, if needed.”

Two authors of the new guidelines reported financial relationships with Seno Medical Instruments, the Genentech Foundation, Crispr Therapeutics, BEAM Therapeutics, Intellia Therapeutics, Editas Medicine, Freenome, and Guardant Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

When the American Cancer Society recently unveiled changes to its lung cancer screening guidance, the aim was to remove barriers to screening and catch more cancers in high-risk people earlier.

Although the lung cancer death rate has declined significantly over the past few decades, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.

Detecting lung cancer early is key to improving survival. Still, lung cancer screening rates are poor. In 2021, the American Lung Association estimated that 14 million US adults qualified for lung cancer screening, but only 5.8% received it.

Smokers or former smokers without symptoms may forgo regular screening and only receive their screening scan after symptoms emerge, explained Janani S. Reisenauer, MD, Division Chair of Thoracic Surgery at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. But by the time symptoms develop, the cancer is typically more advanced, and treatment options become more limited.

The goal of the new American Cancer Society guidelines, published in early November 2023 in CA: A Cancer Journal for Physicians, is to identify lung cancers at earlier stages when they are easier to treat.

Almost 5 million more high-risk people will now qualify for regular lung cancer screening, the guideline authors estimated.

But will expanding screening help reduce deaths from lung cancer? And perhaps just as important, will the guidelines move the needle on the “disappointingly low” lung cancer screening rates up to this point?

“I definitely think it’s a step in the right direction,” said Lecia V. Sequist, MD, MPH, clinical researcher and lung cancer medical oncologist, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston, Massachusetts.

The new guidelines lowered the age for annual lung cancer screening among asymptomatic former or current smokers from 55-74 years to 50-80 years. The update also now considers a high-risk person anyone with a 20-pack-year history, down from a 30-pack-year history, and removes the requirement that former smokers must have quit within 15 years to be eligible for screening.

As people age, their risk for lung cancer increases, so it makes sense to screen all former smokers regardless of when they quit, explained Kim Lori Sandler, MD, from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, and cochair of the American College of Radiology’s Lung Cancer Screening Steering Committee.