User login

Aquatic Antagonists: Lionfish (Pterois volitans)

The lionfish (Pterois volitans) is a member of the Scorpaenidae family of venomous fish.1-3 Lionfish are an invasive species originally from the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Red Sea that now are widely found throughout tropical and temperate oceans in both hemispheres. They are a popular aquarium fish and were inadvertently introduced in the Atlantic Ocean in South Florida during the late 1980s to early 1990s.2,4 Since then, lionfish have spread into reef systems throughout the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico in rapidly growing numbers, and they are now fo und all along the southeastern coast of the United States.5

Characteristics

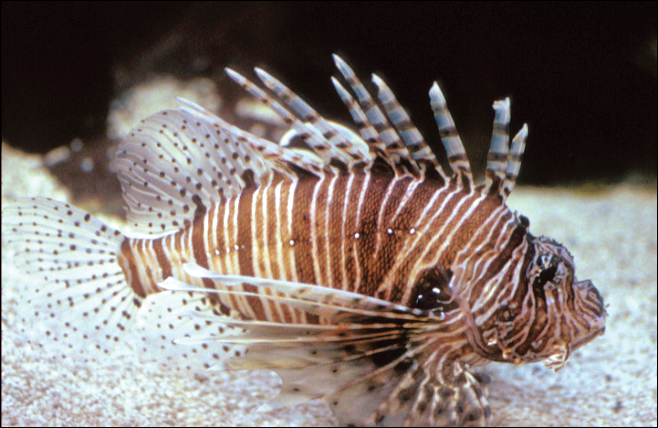

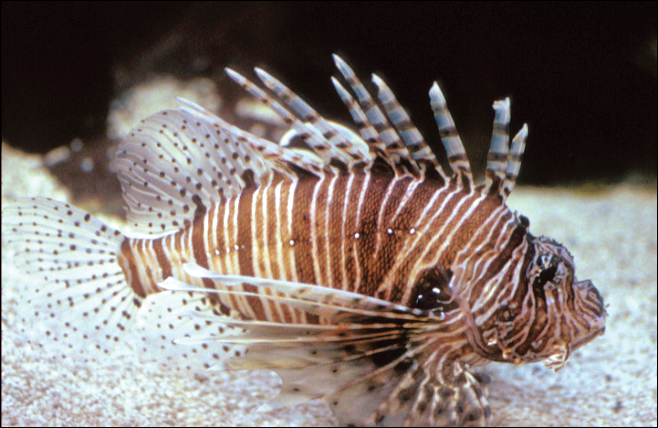

Lionfish are brightly colored with red or maroon and white stripes, tentacles above the eyes and mouth, fan-shaped pectoral fins, and spines that deliver an especially painful venomous sting that often results in edema (Figure 1). They have 12 dorsal spines, 2 pelvic spines, and 3 anal spines.

Symptoms of Envenomation

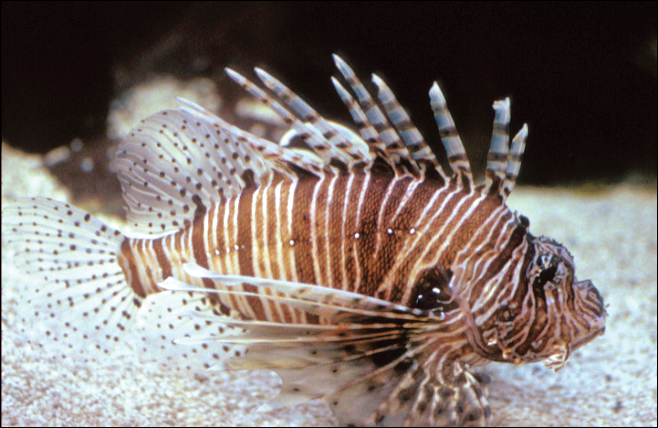

As lionfish continue to spread to popular areas of the southeast Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, the chances of human contact with lionfish have increased. Lionfish stings are now the second most common marine envenomation injury after those caused by stingrays.4 Lionfish stings usually occur on the hands, fingers, or forearms during handling of the fish in ocean waters or in maintenance of aquariums. The mechanism of the venom apparatus is similar for all venomous fish. The spines have surrounding integumentary sheaths containing venom that rupture and inject venom when they penetrate the skin.6 The venom is a heat-labile neuromuscular toxin that causes edema (Figure 2), plasma extravasation, and thrombotic skin lesions.7

Wounds are classified into 3 categories: grade I consists of local erythema/ecchymosis, grade II involves vesicle or blister formation, and grade III denotes wounds that develop local necrosis.8 The sting causes immediate and severe throbbing pain, often described as excruciating or rated 10/10 on a basic pain scale, typically radiating up the affected limb. Puncture sites may bleed and often have associated redness and swelling. Pain may last up to 24 hours. Occasionally, foreign material may be left in the wound requiring removal. There also is a chance of secondary infection at the wound site, and severe envenomation can lead to local tissue necrosis.8 Systemic effects can occur in some cases, including nausea, vomiting, sweating, headache, dizziness, disorientation, palpitations, and even syncope.9 However, to our knowledge there are no documented cases of human death from a lionfish sting. Anaphylactic reactions are possible and require immediate treatment.6

A study conducted in the French West Indies evaluated 117 patients with lionfish envenomation and found that victims experienced severe pain and local edema (100%), paresthesia (90%), abdominal cramps (62%), extensive edema (53%), tachycardia (34%), skin rash (32%), gastrointestinal tract symptoms (28%), syncope (27%), transient weakness (24%), hypertension (21%), hypotension (18%), and hyperthermia (9%).9 Complications included local infection (18%) such as skin abscess (5%), skin necrosis (3%), and septic arthritis (2%). Twenty-two percent of patients were hospitalized and 8% required surgery. Local infectious complications were more frequent in those with multiple stings (19%). The study concluded that lionfish now represent a major health threat in the West Indies.9 As lionfish numbers have grown, health care providers are seeing increasing numbers of envenomation cases in areas of the coastal southeastern United States and Caribbean associated with considerable morbidity. Providers in nonendemic areas also may see envenomation injuries due to the lionfish popularity in home aquariums.9

Management

Individuals with lionfish stings should immerse the affected area in hot but not scalding water. Those with more serious injuries should seek medical attention. Home remedies that are generally contraindicated include application of topical papain or meat tenderizer.10 Data on ice packs are mixed, but because the toxin is heat labile, the most effective initial step in treatment is immersion of the affected area in water (temperature, 40°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes.6 The hot water inactivates the heat-labile toxin, leading to near-complete symptomatic relief in 80% of cases and moderate relief in an additional 14%. Immersion time more than 90 minutes considerably increases the risk for burns. Children should always be monitored to prevent burns. If a patient has received a nerve block for analgesia, the wound should not be immersed in hot water to avoid burns to the skin. The wound should be meticulously cleaned with saline irrigation, and radiography or ultrasonography should be performed as deemed necessary to look for any retained foreign bodies.8 Patients may require parenteral or oral analgesia as well as careful follow-up to ensure proper healing.9 Systemic symptoms require supportive care. Venomous fish wounds typically are small and superficial. Empiric antibiotic therapy is not advised for superficial wounds but may be required for clinically infected wounds.8 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given as appropriate to all affected patients. It has been noted that blister fluid contains high concentrations of lionfish venom, and when present, it increases the likelihood of converting the injury from a grade II to grade III wound with tissue necrosis; therefore, blisters should be drained or excised to decrease the chances of subsequent tissue necrosis.11,12 If secondary infection such as cellulitis develops, antibiotics should be chosen to cover likely pathogens including common skin flora such as staphylococci and marine organisms such as Vibrio species. Wounds showing signs of infection should be cultured, with antibiotics adjusted according to sensitivities.5 Deeper wounds should be left open (unsutured) with a proper dressing to heal. Any wounds that involve vascular or joint structures require specialty management. Wounds involving joints may on occasion require surgical exploration and debridement.

Public Health Concerns

In an attempt to slow the growth of their population, human consumption of the fish has been encouraged. The lionfish toxin is inactivated by cooking, and the fish is considered a delicacy; however, a study in the Virgin Islands found that in areas with endemic ciguatera poisoning, 12% of lionfish carried amounts of the toxin above the level considered safe for consumption. This toxin is not inactivated by cooking or freezing and can lead to ciguatera fish poisoning for which there is no antidote and can be associated with prolonged neurotoxicity.13

Conclusion

As lionfish numbers continue to increase, physicians across multiple specialties and regions may see an increase in envenomation injuries. It is important that physicians are aware of how to recognize and treat lionfish stings, as prompt and comprehensive treatment provides benefit to the patient.

- Pterois volitans. Integrated Taxonomic Information System website. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=166883#null. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Morris JA Jr, Whitfield PE. Biology, Ecology, Control and Management of the Invasive Indopacific Lionfish: An Updated Integrated Assessment. Beaufort, NC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2009. http://aquaticcommons.org/2847/1/NCCOS_TM_99.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Pterois volitans/miles. US Geological Survey website. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=963. Revised April 18, 2018. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Diaz JH. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans) pose public health threats [published online August 15, 2015]. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167:166-171.

- Diaz JH. Marine Scorpaenidae envenomation in travelers: epidemiology, management, and prevention. J Travel Med. 2015;22:251-258.

- Hobday D, Chadha P, Din AH, et al. Denaturing the lionfish. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic20.

- Sáenz A, Ortiz N, Lomonte B, et al. Comparison of biochemical and cytotoxic activities of extracts obtained from dorsal spines and caudal fin of adult and juvenile non-native Caribbean lionfish (Pterois volitans/miles). Toxicon. 2017;137:158-167.

- Schult RF, Acquisto NM, Stair CK, et al. A case of lionfish envenomation presenting to an inland emergency department [published online August 13, 2017]. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2017;2017:5893563.

- Resiere D, Cerland L, De Haro L, et al. Envenomation by the invasive Pterois volitans species (lionfish) in the French West Indies—a two-year prospective study in Martinique. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54:313-318.

- Auerbach PS. Envenomation by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerback PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:1740-1741.

- Auerbach PS, McKinney HE, Rees RE, et al. Analysis of vesicle fluid following the sting of the lionfish, Pterois volitans. Toxicon. 1987;25:1350-1353.

- Patel MR, Wells S. Lionfish envenomation of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18:523-525.

- Robertson A, Garcia AC, Quintana HA, et al. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans): a potential human health threat for Ciguatera fish poisoning in tropical waters. Marine Drugs. 2014;12:88-97.

The lionfish (Pterois volitans) is a member of the Scorpaenidae family of venomous fish.1-3 Lionfish are an invasive species originally from the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Red Sea that now are widely found throughout tropical and temperate oceans in both hemispheres. They are a popular aquarium fish and were inadvertently introduced in the Atlantic Ocean in South Florida during the late 1980s to early 1990s.2,4 Since then, lionfish have spread into reef systems throughout the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico in rapidly growing numbers, and they are now fo und all along the southeastern coast of the United States.5

Characteristics

Lionfish are brightly colored with red or maroon and white stripes, tentacles above the eyes and mouth, fan-shaped pectoral fins, and spines that deliver an especially painful venomous sting that often results in edema (Figure 1). They have 12 dorsal spines, 2 pelvic spines, and 3 anal spines.

Symptoms of Envenomation

As lionfish continue to spread to popular areas of the southeast Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, the chances of human contact with lionfish have increased. Lionfish stings are now the second most common marine envenomation injury after those caused by stingrays.4 Lionfish stings usually occur on the hands, fingers, or forearms during handling of the fish in ocean waters or in maintenance of aquariums. The mechanism of the venom apparatus is similar for all venomous fish. The spines have surrounding integumentary sheaths containing venom that rupture and inject venom when they penetrate the skin.6 The venom is a heat-labile neuromuscular toxin that causes edema (Figure 2), plasma extravasation, and thrombotic skin lesions.7

Wounds are classified into 3 categories: grade I consists of local erythema/ecchymosis, grade II involves vesicle or blister formation, and grade III denotes wounds that develop local necrosis.8 The sting causes immediate and severe throbbing pain, often described as excruciating or rated 10/10 on a basic pain scale, typically radiating up the affected limb. Puncture sites may bleed and often have associated redness and swelling. Pain may last up to 24 hours. Occasionally, foreign material may be left in the wound requiring removal. There also is a chance of secondary infection at the wound site, and severe envenomation can lead to local tissue necrosis.8 Systemic effects can occur in some cases, including nausea, vomiting, sweating, headache, dizziness, disorientation, palpitations, and even syncope.9 However, to our knowledge there are no documented cases of human death from a lionfish sting. Anaphylactic reactions are possible and require immediate treatment.6

A study conducted in the French West Indies evaluated 117 patients with lionfish envenomation and found that victims experienced severe pain and local edema (100%), paresthesia (90%), abdominal cramps (62%), extensive edema (53%), tachycardia (34%), skin rash (32%), gastrointestinal tract symptoms (28%), syncope (27%), transient weakness (24%), hypertension (21%), hypotension (18%), and hyperthermia (9%).9 Complications included local infection (18%) such as skin abscess (5%), skin necrosis (3%), and septic arthritis (2%). Twenty-two percent of patients were hospitalized and 8% required surgery. Local infectious complications were more frequent in those with multiple stings (19%). The study concluded that lionfish now represent a major health threat in the West Indies.9 As lionfish numbers have grown, health care providers are seeing increasing numbers of envenomation cases in areas of the coastal southeastern United States and Caribbean associated with considerable morbidity. Providers in nonendemic areas also may see envenomation injuries due to the lionfish popularity in home aquariums.9

Management

Individuals with lionfish stings should immerse the affected area in hot but not scalding water. Those with more serious injuries should seek medical attention. Home remedies that are generally contraindicated include application of topical papain or meat tenderizer.10 Data on ice packs are mixed, but because the toxin is heat labile, the most effective initial step in treatment is immersion of the affected area in water (temperature, 40°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes.6 The hot water inactivates the heat-labile toxin, leading to near-complete symptomatic relief in 80% of cases and moderate relief in an additional 14%. Immersion time more than 90 minutes considerably increases the risk for burns. Children should always be monitored to prevent burns. If a patient has received a nerve block for analgesia, the wound should not be immersed in hot water to avoid burns to the skin. The wound should be meticulously cleaned with saline irrigation, and radiography or ultrasonography should be performed as deemed necessary to look for any retained foreign bodies.8 Patients may require parenteral or oral analgesia as well as careful follow-up to ensure proper healing.9 Systemic symptoms require supportive care. Venomous fish wounds typically are small and superficial. Empiric antibiotic therapy is not advised for superficial wounds but may be required for clinically infected wounds.8 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given as appropriate to all affected patients. It has been noted that blister fluid contains high concentrations of lionfish venom, and when present, it increases the likelihood of converting the injury from a grade II to grade III wound with tissue necrosis; therefore, blisters should be drained or excised to decrease the chances of subsequent tissue necrosis.11,12 If secondary infection such as cellulitis develops, antibiotics should be chosen to cover likely pathogens including common skin flora such as staphylococci and marine organisms such as Vibrio species. Wounds showing signs of infection should be cultured, with antibiotics adjusted according to sensitivities.5 Deeper wounds should be left open (unsutured) with a proper dressing to heal. Any wounds that involve vascular or joint structures require specialty management. Wounds involving joints may on occasion require surgical exploration and debridement.

Public Health Concerns

In an attempt to slow the growth of their population, human consumption of the fish has been encouraged. The lionfish toxin is inactivated by cooking, and the fish is considered a delicacy; however, a study in the Virgin Islands found that in areas with endemic ciguatera poisoning, 12% of lionfish carried amounts of the toxin above the level considered safe for consumption. This toxin is not inactivated by cooking or freezing and can lead to ciguatera fish poisoning for which there is no antidote and can be associated with prolonged neurotoxicity.13

Conclusion

As lionfish numbers continue to increase, physicians across multiple specialties and regions may see an increase in envenomation injuries. It is important that physicians are aware of how to recognize and treat lionfish stings, as prompt and comprehensive treatment provides benefit to the patient.

The lionfish (Pterois volitans) is a member of the Scorpaenidae family of venomous fish.1-3 Lionfish are an invasive species originally from the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Red Sea that now are widely found throughout tropical and temperate oceans in both hemispheres. They are a popular aquarium fish and were inadvertently introduced in the Atlantic Ocean in South Florida during the late 1980s to early 1990s.2,4 Since then, lionfish have spread into reef systems throughout the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico in rapidly growing numbers, and they are now fo und all along the southeastern coast of the United States.5

Characteristics

Lionfish are brightly colored with red or maroon and white stripes, tentacles above the eyes and mouth, fan-shaped pectoral fins, and spines that deliver an especially painful venomous sting that often results in edema (Figure 1). They have 12 dorsal spines, 2 pelvic spines, and 3 anal spines.

Symptoms of Envenomation

As lionfish continue to spread to popular areas of the southeast Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, the chances of human contact with lionfish have increased. Lionfish stings are now the second most common marine envenomation injury after those caused by stingrays.4 Lionfish stings usually occur on the hands, fingers, or forearms during handling of the fish in ocean waters or in maintenance of aquariums. The mechanism of the venom apparatus is similar for all venomous fish. The spines have surrounding integumentary sheaths containing venom that rupture and inject venom when they penetrate the skin.6 The venom is a heat-labile neuromuscular toxin that causes edema (Figure 2), plasma extravasation, and thrombotic skin lesions.7

Wounds are classified into 3 categories: grade I consists of local erythema/ecchymosis, grade II involves vesicle or blister formation, and grade III denotes wounds that develop local necrosis.8 The sting causes immediate and severe throbbing pain, often described as excruciating or rated 10/10 on a basic pain scale, typically radiating up the affected limb. Puncture sites may bleed and often have associated redness and swelling. Pain may last up to 24 hours. Occasionally, foreign material may be left in the wound requiring removal. There also is a chance of secondary infection at the wound site, and severe envenomation can lead to local tissue necrosis.8 Systemic effects can occur in some cases, including nausea, vomiting, sweating, headache, dizziness, disorientation, palpitations, and even syncope.9 However, to our knowledge there are no documented cases of human death from a lionfish sting. Anaphylactic reactions are possible and require immediate treatment.6

A study conducted in the French West Indies evaluated 117 patients with lionfish envenomation and found that victims experienced severe pain and local edema (100%), paresthesia (90%), abdominal cramps (62%), extensive edema (53%), tachycardia (34%), skin rash (32%), gastrointestinal tract symptoms (28%), syncope (27%), transient weakness (24%), hypertension (21%), hypotension (18%), and hyperthermia (9%).9 Complications included local infection (18%) such as skin abscess (5%), skin necrosis (3%), and septic arthritis (2%). Twenty-two percent of patients were hospitalized and 8% required surgery. Local infectious complications were more frequent in those with multiple stings (19%). The study concluded that lionfish now represent a major health threat in the West Indies.9 As lionfish numbers have grown, health care providers are seeing increasing numbers of envenomation cases in areas of the coastal southeastern United States and Caribbean associated with considerable morbidity. Providers in nonendemic areas also may see envenomation injuries due to the lionfish popularity in home aquariums.9

Management

Individuals with lionfish stings should immerse the affected area in hot but not scalding water. Those with more serious injuries should seek medical attention. Home remedies that are generally contraindicated include application of topical papain or meat tenderizer.10 Data on ice packs are mixed, but because the toxin is heat labile, the most effective initial step in treatment is immersion of the affected area in water (temperature, 40°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes.6 The hot water inactivates the heat-labile toxin, leading to near-complete symptomatic relief in 80% of cases and moderate relief in an additional 14%. Immersion time more than 90 minutes considerably increases the risk for burns. Children should always be monitored to prevent burns. If a patient has received a nerve block for analgesia, the wound should not be immersed in hot water to avoid burns to the skin. The wound should be meticulously cleaned with saline irrigation, and radiography or ultrasonography should be performed as deemed necessary to look for any retained foreign bodies.8 Patients may require parenteral or oral analgesia as well as careful follow-up to ensure proper healing.9 Systemic symptoms require supportive care. Venomous fish wounds typically are small and superficial. Empiric antibiotic therapy is not advised for superficial wounds but may be required for clinically infected wounds.8 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given as appropriate to all affected patients. It has been noted that blister fluid contains high concentrations of lionfish venom, and when present, it increases the likelihood of converting the injury from a grade II to grade III wound with tissue necrosis; therefore, blisters should be drained or excised to decrease the chances of subsequent tissue necrosis.11,12 If secondary infection such as cellulitis develops, antibiotics should be chosen to cover likely pathogens including common skin flora such as staphylococci and marine organisms such as Vibrio species. Wounds showing signs of infection should be cultured, with antibiotics adjusted according to sensitivities.5 Deeper wounds should be left open (unsutured) with a proper dressing to heal. Any wounds that involve vascular or joint structures require specialty management. Wounds involving joints may on occasion require surgical exploration and debridement.

Public Health Concerns

In an attempt to slow the growth of their population, human consumption of the fish has been encouraged. The lionfish toxin is inactivated by cooking, and the fish is considered a delicacy; however, a study in the Virgin Islands found that in areas with endemic ciguatera poisoning, 12% of lionfish carried amounts of the toxin above the level considered safe for consumption. This toxin is not inactivated by cooking or freezing and can lead to ciguatera fish poisoning for which there is no antidote and can be associated with prolonged neurotoxicity.13

Conclusion

As lionfish numbers continue to increase, physicians across multiple specialties and regions may see an increase in envenomation injuries. It is important that physicians are aware of how to recognize and treat lionfish stings, as prompt and comprehensive treatment provides benefit to the patient.

- Pterois volitans. Integrated Taxonomic Information System website. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=166883#null. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Morris JA Jr, Whitfield PE. Biology, Ecology, Control and Management of the Invasive Indopacific Lionfish: An Updated Integrated Assessment. Beaufort, NC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2009. http://aquaticcommons.org/2847/1/NCCOS_TM_99.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Pterois volitans/miles. US Geological Survey website. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=963. Revised April 18, 2018. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Diaz JH. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans) pose public health threats [published online August 15, 2015]. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167:166-171.

- Diaz JH. Marine Scorpaenidae envenomation in travelers: epidemiology, management, and prevention. J Travel Med. 2015;22:251-258.

- Hobday D, Chadha P, Din AH, et al. Denaturing the lionfish. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic20.

- Sáenz A, Ortiz N, Lomonte B, et al. Comparison of biochemical and cytotoxic activities of extracts obtained from dorsal spines and caudal fin of adult and juvenile non-native Caribbean lionfish (Pterois volitans/miles). Toxicon. 2017;137:158-167.

- Schult RF, Acquisto NM, Stair CK, et al. A case of lionfish envenomation presenting to an inland emergency department [published online August 13, 2017]. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2017;2017:5893563.

- Resiere D, Cerland L, De Haro L, et al. Envenomation by the invasive Pterois volitans species (lionfish) in the French West Indies—a two-year prospective study in Martinique. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54:313-318.

- Auerbach PS. Envenomation by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerback PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:1740-1741.

- Auerbach PS, McKinney HE, Rees RE, et al. Analysis of vesicle fluid following the sting of the lionfish, Pterois volitans. Toxicon. 1987;25:1350-1353.

- Patel MR, Wells S. Lionfish envenomation of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18:523-525.

- Robertson A, Garcia AC, Quintana HA, et al. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans): a potential human health threat for Ciguatera fish poisoning in tropical waters. Marine Drugs. 2014;12:88-97.

- Pterois volitans. Integrated Taxonomic Information System website. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=166883#null. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Morris JA Jr, Whitfield PE. Biology, Ecology, Control and Management of the Invasive Indopacific Lionfish: An Updated Integrated Assessment. Beaufort, NC: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2009. http://aquaticcommons.org/2847/1/NCCOS_TM_99.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Pterois volitans/miles. US Geological Survey website. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=963. Revised April 18, 2018. Accessed September 6, 2018.

- Diaz JH. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans) pose public health threats [published online August 15, 2015]. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167:166-171.

- Diaz JH. Marine Scorpaenidae envenomation in travelers: epidemiology, management, and prevention. J Travel Med. 2015;22:251-258.

- Hobday D, Chadha P, Din AH, et al. Denaturing the lionfish. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic20.

- Sáenz A, Ortiz N, Lomonte B, et al. Comparison of biochemical and cytotoxic activities of extracts obtained from dorsal spines and caudal fin of adult and juvenile non-native Caribbean lionfish (Pterois volitans/miles). Toxicon. 2017;137:158-167.

- Schult RF, Acquisto NM, Stair CK, et al. A case of lionfish envenomation presenting to an inland emergency department [published online August 13, 2017]. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2017;2017:5893563.

- Resiere D, Cerland L, De Haro L, et al. Envenomation by the invasive Pterois volitans species (lionfish) in the French West Indies—a two-year prospective study in Martinique. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54:313-318.

- Auerbach PS. Envenomation by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerback PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:1740-1741.

- Auerbach PS, McKinney HE, Rees RE, et al. Analysis of vesicle fluid following the sting of the lionfish, Pterois volitans. Toxicon. 1987;25:1350-1353.

- Patel MR, Wells S. Lionfish envenomation of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18:523-525.

- Robertson A, Garcia AC, Quintana HA, et al. Invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans): a potential human health threat for Ciguatera fish poisoning in tropical waters. Marine Drugs. 2014;12:88-97.

Practice Points

- Lionfish are now found all along the southeastern coast of the United States. Physicians may see an increase in envenomation injuries.

- Treat lionfish envenomation with immediate immersion in warm water (temperature, 40°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes to deactivate heat-labile toxin.

- Infected wounds should be treated with antibiotics for common skin flora and marine organisms such as Vibrio species.

Investing in the Future of Inpatient Dermatology: The Evolution and Impact of Specialized Dermatologic Consultation in Hospitalized Patients

The practice of inpatient dermatology has a rich history rooted in specialized hospital wards that housed patients with chronic dermatoses. Because systemic agents were limited, the care of these patients required skilled nursing and a distinctive knowledge of the application of numerous topical agents, including washes, baths, powders, lotions, and pastes1; however, with the evolving nature of health care in the last half a century, such dermatologic inpatient units are now rare, with only 2 units remaining in the United States, specifically at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and at the University of Miami.2

Although the shift away from a primary dermatologic admitting service is likely multifactorial, what is more sobering is that the majority of inpatients with dermatologic disorders are cared for by nondermatologists.2 Although the dynamics for such a diminished presence are due to various personal and professional concerns, the essential outcome for patients hospitalized with a cutaneous concern—whether directly related to their hospitalization or iatrogenic in nature—is the potential for suboptimal care.3

Fortunately, the practice of inpatient dermatology currently is undergoing a renaissance. With this renewed interest in hospital-based dermatology, there is a growing body of evidence that demonstrates how the dermatology hospitalist has become a vital member of the inpatient team, adding value to the care of patients across all specialties.

To explore the impact of consultative dermatology services, there has been a push by members of the Society for Dermatology Hospitalists to elucidate the contributions of dermatologists in the inpatient setting, which has been accomplished primarily by defining and characterizing the types of patients that dermatology hospitalists care for and, more recently, by demonstrating the improved outcomes that result from expert consultation.

Breadth of Inpatient Dermatologic Consultations

With the adaptation of dermatology consultation services, the scope of practice has shifted from the skilled management of chronic dermatoses to one with an emphasis on the identification of various acute dermatologic diseases. Although the extent of such acute disease states in the inpatient setting is vast, it is interesting to note that the majority of consultations are for common conditions, namely cutaneous infections, venous stasis dermatitis, contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and cutaneous drug eruptions (Table).4,5

Moreover, for the services that obtain dermatologic consultation, the majority of requests originate from internal medicine and hematology/oncology.4,5 Although internal medicine often is the largest-represented specialty in the hospital and provides a proportional amount of dermatology consultations, hematology/oncology patients represent a distinct cohort who are prone to unique mucocutaneous dermatoses related to underlying malignancies, immunosuppression, and cancer-specific therapies (eg, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, stem cell transplantation). Within this subset of patients, cutaneous infections and drug eruptions constitute the majority of cases, while graft-versus-host disease and neutrophilic dermatoses account for a smaller percentage of dermatologic disease in this population. Given the complex and uncommon nature of these dermatoses, timely intervention by a dermatologist can have a considerable impact on morbidity and mortality associated with such disease states.6,7

Among pediatric patients, dermatology consultation patterns mimic those seen among adult patients, with common conditions such as atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis representing the majority of consultations.8-11 Vascular lesions further represent a unique source of consultation among pediatric patients. Although they often are considered an outpatient concern, one group found that the majority of inpatient consultations for vascular lesions led to early identification of a syndromic association and/or complication (eg, ulceration).10 Identifying these cases in the hospital provides early opportunities for intervention and multidisciplinary care.

Adding Value to the Care of Hospitalized Patients

Following other inpatient models, hospitalist dermatology has begun to demonstrate feasibility, advances in quality improvement, and most importantly improved health care outcomes. In an effort to better characterize the enhancement of such health care delivery, recent literature around the impact of inpatient dermatology consultation has centered on improving key objective hospital-based quality measures, namely diagnosis and management as well as hospital length of stay (LOS) and readmission rates.5,12-18

When identifying cutaneous disease, recent evidence points to the increased diagnostic accuracy by way of dermatology consultation. Specifically, diagnoses were changed 30% to 70% of the time when consultations were provided.6,12-15 Interestingly, misdiagnosis regularly centered on common diagnoses, specifically cellulitis, stasis dermatitis, and hypersensitivity reactions.6,12-16 In a multi-institutional retrospective study that examined the national incidence of cellulitis misdiagnosis, the authors found that when a dermatology consultation for presumed cellulitis was called, approximately 75% (N=55) of cases represented mimickers of cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous fungal infections. Moreover, in more than 38% (N=21) of such cellulitis consultations, patients often had more than one ongoing disease process, further speaking to the diagnostic accuracy obtained from expert consultation.16 The result of such misdiagnosis is not trivial, as unnecessary hospital admission or inappropriate treatment due to misdiagnosis of cutaneous disease often leads to avoidable complications and preventable health care spending. In a cross-sectional analysis of patients diagnosed with presumed lower extremity cellulitis (N=259), approximately 30% were misdiagnosed. In these cases, more than 90% of patients received unnecessary antibiotics, with approximately 30% of them experiencing a complication or avoidable utilization of health care related to their misdiagnosis.17

Along with the profound impact on diagnostic accuracy, management and treatment are almost universally affected after dermatology consultation.5,12-14 Such findings bear importance on optimizing hospital LOS as well as readmission rates. For hospital LOS, a recent study demonstrated reductions in LOS by 2.64 days as well as 1-year cutaneous disease-specific readmissions for patients who received dermatologic consultation for their inflammatory skin disease.18 Similarly, in a recent prospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with presumed lower extremity cellulitis, hospital LOS decreased by 2 days following a diagnosis of pseudocellulitis via timely dermatologic consultation. Across the United States, such reductions in LOS associated with unnecessary hospitalization due to pseudocellulitis can result in annual health care savings of $100 to $200 million.13 As such, early dermatologic intervention plays a vital role in diagnostic accuracy, appropriate treatment implementation, expedited discharge, and the overall economics of health care delivery and utilization, thereby supporting the utility of clinical decision support through expert consultation.

Conclusion

There is a clear and distinct value that results in having specialized inpatient dermatology services. Such expert consultation enhances quality of care and reduces health care costs. Although the implementation and success of inpatient dermatology services has primarily been observed at large hospitals/tertiary care centers, there is incredible potential to further our impact through engagement in our community hospitals. With that said, all practicing dermatologists should feel empowered to employ their expert skillset in their own communities, as such access to care and specialty support is desperately needed and can remarkably impact health care outcomes. Moreover, in addition to the direct impact on health care delivery and economics, the intangible benefits of an inpatient dermatology presence are innumerable, as opportunities to promote quality research and improve trainee education also demonstrate our value. These facets together provide a positive perspective on the potential contribution that our field can have on shaping the outlook of hospital medicine. As such, in addition to enjoying the current renaissance of inpatient dermatology, it is imperative that dermatologists build on this momentum and invest in the future of consultative dermatology.

- Albert MR, Mackool BT. A dermatology ward at the beginning of the 20th century. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 1):113-123.

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558.

- Helms AE, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Hospital consultations: time to address an unmet need? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:308-311.

- Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience of a year of adult hospital dermatology consultations. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1150-1156.

- Galimberti F, Guren L, Fernandez AP, et al. Dermatology consultations significantly contribute quality to care of hospitalized patients: a prospective study of dermatology inpatient consults at a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E547-E551.

- Tracey EH, Forrestel A, Rosenbach M, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:835-836.

- Phillips GS, Freites-Martinez A, Hsu M, et al. Inflammatory dermatoses, infections, and drug eruptions are the most common skin conditions in hospitalized cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1102-1109.

- Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Pediatric hospital dermatology: experience with inpatient and consult services at the Mayo Clinic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:433-437.

- Afsar FS. Analysis of pediatric dermatology inpatient consultations in a pediatric teaching hospital. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115:E377-E384.

- McMahon P, Goddard D, Frieden IJ. Pediatric dermatology inpatient consultations: a retrospective study of 427 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:926-931.

- Peñate Y, Borrego L, Hernández N, et al. Pediatric dermatology consultations: a retrospective analysis of inpatient consultations referred to the dermatology service. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:115-118.

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482.

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543.

- Falanga V, Schachner LA, Rae V, et al. Dermatologic consultations in the hospital setting. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1022-1025.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis [published online November 2, 2016]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3816.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528.

The practice of inpatient dermatology has a rich history rooted in specialized hospital wards that housed patients with chronic dermatoses. Because systemic agents were limited, the care of these patients required skilled nursing and a distinctive knowledge of the application of numerous topical agents, including washes, baths, powders, lotions, and pastes1; however, with the evolving nature of health care in the last half a century, such dermatologic inpatient units are now rare, with only 2 units remaining in the United States, specifically at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and at the University of Miami.2

Although the shift away from a primary dermatologic admitting service is likely multifactorial, what is more sobering is that the majority of inpatients with dermatologic disorders are cared for by nondermatologists.2 Although the dynamics for such a diminished presence are due to various personal and professional concerns, the essential outcome for patients hospitalized with a cutaneous concern—whether directly related to their hospitalization or iatrogenic in nature—is the potential for suboptimal care.3

Fortunately, the practice of inpatient dermatology currently is undergoing a renaissance. With this renewed interest in hospital-based dermatology, there is a growing body of evidence that demonstrates how the dermatology hospitalist has become a vital member of the inpatient team, adding value to the care of patients across all specialties.

To explore the impact of consultative dermatology services, there has been a push by members of the Society for Dermatology Hospitalists to elucidate the contributions of dermatologists in the inpatient setting, which has been accomplished primarily by defining and characterizing the types of patients that dermatology hospitalists care for and, more recently, by demonstrating the improved outcomes that result from expert consultation.

Breadth of Inpatient Dermatologic Consultations

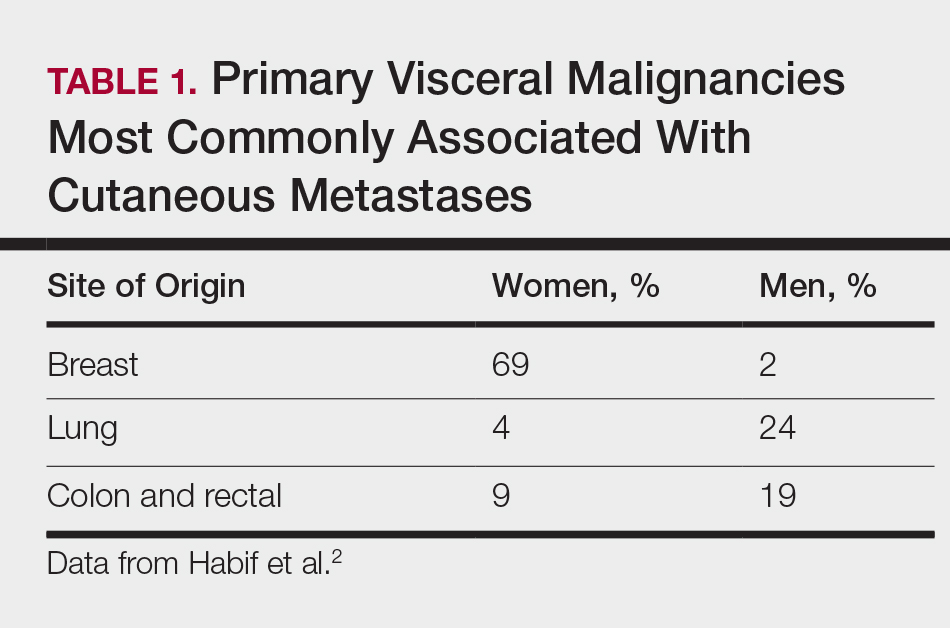

With the adaptation of dermatology consultation services, the scope of practice has shifted from the skilled management of chronic dermatoses to one with an emphasis on the identification of various acute dermatologic diseases. Although the extent of such acute disease states in the inpatient setting is vast, it is interesting to note that the majority of consultations are for common conditions, namely cutaneous infections, venous stasis dermatitis, contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and cutaneous drug eruptions (Table).4,5

Moreover, for the services that obtain dermatologic consultation, the majority of requests originate from internal medicine and hematology/oncology.4,5 Although internal medicine often is the largest-represented specialty in the hospital and provides a proportional amount of dermatology consultations, hematology/oncology patients represent a distinct cohort who are prone to unique mucocutaneous dermatoses related to underlying malignancies, immunosuppression, and cancer-specific therapies (eg, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, stem cell transplantation). Within this subset of patients, cutaneous infections and drug eruptions constitute the majority of cases, while graft-versus-host disease and neutrophilic dermatoses account for a smaller percentage of dermatologic disease in this population. Given the complex and uncommon nature of these dermatoses, timely intervention by a dermatologist can have a considerable impact on morbidity and mortality associated with such disease states.6,7

Among pediatric patients, dermatology consultation patterns mimic those seen among adult patients, with common conditions such as atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis representing the majority of consultations.8-11 Vascular lesions further represent a unique source of consultation among pediatric patients. Although they often are considered an outpatient concern, one group found that the majority of inpatient consultations for vascular lesions led to early identification of a syndromic association and/or complication (eg, ulceration).10 Identifying these cases in the hospital provides early opportunities for intervention and multidisciplinary care.

Adding Value to the Care of Hospitalized Patients

Following other inpatient models, hospitalist dermatology has begun to demonstrate feasibility, advances in quality improvement, and most importantly improved health care outcomes. In an effort to better characterize the enhancement of such health care delivery, recent literature around the impact of inpatient dermatology consultation has centered on improving key objective hospital-based quality measures, namely diagnosis and management as well as hospital length of stay (LOS) and readmission rates.5,12-18

When identifying cutaneous disease, recent evidence points to the increased diagnostic accuracy by way of dermatology consultation. Specifically, diagnoses were changed 30% to 70% of the time when consultations were provided.6,12-15 Interestingly, misdiagnosis regularly centered on common diagnoses, specifically cellulitis, stasis dermatitis, and hypersensitivity reactions.6,12-16 In a multi-institutional retrospective study that examined the national incidence of cellulitis misdiagnosis, the authors found that when a dermatology consultation for presumed cellulitis was called, approximately 75% (N=55) of cases represented mimickers of cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous fungal infections. Moreover, in more than 38% (N=21) of such cellulitis consultations, patients often had more than one ongoing disease process, further speaking to the diagnostic accuracy obtained from expert consultation.16 The result of such misdiagnosis is not trivial, as unnecessary hospital admission or inappropriate treatment due to misdiagnosis of cutaneous disease often leads to avoidable complications and preventable health care spending. In a cross-sectional analysis of patients diagnosed with presumed lower extremity cellulitis (N=259), approximately 30% were misdiagnosed. In these cases, more than 90% of patients received unnecessary antibiotics, with approximately 30% of them experiencing a complication or avoidable utilization of health care related to their misdiagnosis.17

Along with the profound impact on diagnostic accuracy, management and treatment are almost universally affected after dermatology consultation.5,12-14 Such findings bear importance on optimizing hospital LOS as well as readmission rates. For hospital LOS, a recent study demonstrated reductions in LOS by 2.64 days as well as 1-year cutaneous disease-specific readmissions for patients who received dermatologic consultation for their inflammatory skin disease.18 Similarly, in a recent prospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with presumed lower extremity cellulitis, hospital LOS decreased by 2 days following a diagnosis of pseudocellulitis via timely dermatologic consultation. Across the United States, such reductions in LOS associated with unnecessary hospitalization due to pseudocellulitis can result in annual health care savings of $100 to $200 million.13 As such, early dermatologic intervention plays a vital role in diagnostic accuracy, appropriate treatment implementation, expedited discharge, and the overall economics of health care delivery and utilization, thereby supporting the utility of clinical decision support through expert consultation.

Conclusion

There is a clear and distinct value that results in having specialized inpatient dermatology services. Such expert consultation enhances quality of care and reduces health care costs. Although the implementation and success of inpatient dermatology services has primarily been observed at large hospitals/tertiary care centers, there is incredible potential to further our impact through engagement in our community hospitals. With that said, all practicing dermatologists should feel empowered to employ their expert skillset in their own communities, as such access to care and specialty support is desperately needed and can remarkably impact health care outcomes. Moreover, in addition to the direct impact on health care delivery and economics, the intangible benefits of an inpatient dermatology presence are innumerable, as opportunities to promote quality research and improve trainee education also demonstrate our value. These facets together provide a positive perspective on the potential contribution that our field can have on shaping the outlook of hospital medicine. As such, in addition to enjoying the current renaissance of inpatient dermatology, it is imperative that dermatologists build on this momentum and invest in the future of consultative dermatology.

The practice of inpatient dermatology has a rich history rooted in specialized hospital wards that housed patients with chronic dermatoses. Because systemic agents were limited, the care of these patients required skilled nursing and a distinctive knowledge of the application of numerous topical agents, including washes, baths, powders, lotions, and pastes1; however, with the evolving nature of health care in the last half a century, such dermatologic inpatient units are now rare, with only 2 units remaining in the United States, specifically at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and at the University of Miami.2

Although the shift away from a primary dermatologic admitting service is likely multifactorial, what is more sobering is that the majority of inpatients with dermatologic disorders are cared for by nondermatologists.2 Although the dynamics for such a diminished presence are due to various personal and professional concerns, the essential outcome for patients hospitalized with a cutaneous concern—whether directly related to their hospitalization or iatrogenic in nature—is the potential for suboptimal care.3

Fortunately, the practice of inpatient dermatology currently is undergoing a renaissance. With this renewed interest in hospital-based dermatology, there is a growing body of evidence that demonstrates how the dermatology hospitalist has become a vital member of the inpatient team, adding value to the care of patients across all specialties.

To explore the impact of consultative dermatology services, there has been a push by members of the Society for Dermatology Hospitalists to elucidate the contributions of dermatologists in the inpatient setting, which has been accomplished primarily by defining and characterizing the types of patients that dermatology hospitalists care for and, more recently, by demonstrating the improved outcomes that result from expert consultation.

Breadth of Inpatient Dermatologic Consultations

With the adaptation of dermatology consultation services, the scope of practice has shifted from the skilled management of chronic dermatoses to one with an emphasis on the identification of various acute dermatologic diseases. Although the extent of such acute disease states in the inpatient setting is vast, it is interesting to note that the majority of consultations are for common conditions, namely cutaneous infections, venous stasis dermatitis, contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and cutaneous drug eruptions (Table).4,5

Moreover, for the services that obtain dermatologic consultation, the majority of requests originate from internal medicine and hematology/oncology.4,5 Although internal medicine often is the largest-represented specialty in the hospital and provides a proportional amount of dermatology consultations, hematology/oncology patients represent a distinct cohort who are prone to unique mucocutaneous dermatoses related to underlying malignancies, immunosuppression, and cancer-specific therapies (eg, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, stem cell transplantation). Within this subset of patients, cutaneous infections and drug eruptions constitute the majority of cases, while graft-versus-host disease and neutrophilic dermatoses account for a smaller percentage of dermatologic disease in this population. Given the complex and uncommon nature of these dermatoses, timely intervention by a dermatologist can have a considerable impact on morbidity and mortality associated with such disease states.6,7

Among pediatric patients, dermatology consultation patterns mimic those seen among adult patients, with common conditions such as atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis representing the majority of consultations.8-11 Vascular lesions further represent a unique source of consultation among pediatric patients. Although they often are considered an outpatient concern, one group found that the majority of inpatient consultations for vascular lesions led to early identification of a syndromic association and/or complication (eg, ulceration).10 Identifying these cases in the hospital provides early opportunities for intervention and multidisciplinary care.

Adding Value to the Care of Hospitalized Patients

Following other inpatient models, hospitalist dermatology has begun to demonstrate feasibility, advances in quality improvement, and most importantly improved health care outcomes. In an effort to better characterize the enhancement of such health care delivery, recent literature around the impact of inpatient dermatology consultation has centered on improving key objective hospital-based quality measures, namely diagnosis and management as well as hospital length of stay (LOS) and readmission rates.5,12-18

When identifying cutaneous disease, recent evidence points to the increased diagnostic accuracy by way of dermatology consultation. Specifically, diagnoses were changed 30% to 70% of the time when consultations were provided.6,12-15 Interestingly, misdiagnosis regularly centered on common diagnoses, specifically cellulitis, stasis dermatitis, and hypersensitivity reactions.6,12-16 In a multi-institutional retrospective study that examined the national incidence of cellulitis misdiagnosis, the authors found that when a dermatology consultation for presumed cellulitis was called, approximately 75% (N=55) of cases represented mimickers of cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous fungal infections. Moreover, in more than 38% (N=21) of such cellulitis consultations, patients often had more than one ongoing disease process, further speaking to the diagnostic accuracy obtained from expert consultation.16 The result of such misdiagnosis is not trivial, as unnecessary hospital admission or inappropriate treatment due to misdiagnosis of cutaneous disease often leads to avoidable complications and preventable health care spending. In a cross-sectional analysis of patients diagnosed with presumed lower extremity cellulitis (N=259), approximately 30% were misdiagnosed. In these cases, more than 90% of patients received unnecessary antibiotics, with approximately 30% of them experiencing a complication or avoidable utilization of health care related to their misdiagnosis.17

Along with the profound impact on diagnostic accuracy, management and treatment are almost universally affected after dermatology consultation.5,12-14 Such findings bear importance on optimizing hospital LOS as well as readmission rates. For hospital LOS, a recent study demonstrated reductions in LOS by 2.64 days as well as 1-year cutaneous disease-specific readmissions for patients who received dermatologic consultation for their inflammatory skin disease.18 Similarly, in a recent prospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with presumed lower extremity cellulitis, hospital LOS decreased by 2 days following a diagnosis of pseudocellulitis via timely dermatologic consultation. Across the United States, such reductions in LOS associated with unnecessary hospitalization due to pseudocellulitis can result in annual health care savings of $100 to $200 million.13 As such, early dermatologic intervention plays a vital role in diagnostic accuracy, appropriate treatment implementation, expedited discharge, and the overall economics of health care delivery and utilization, thereby supporting the utility of clinical decision support through expert consultation.

Conclusion

There is a clear and distinct value that results in having specialized inpatient dermatology services. Such expert consultation enhances quality of care and reduces health care costs. Although the implementation and success of inpatient dermatology services has primarily been observed at large hospitals/tertiary care centers, there is incredible potential to further our impact through engagement in our community hospitals. With that said, all practicing dermatologists should feel empowered to employ their expert skillset in their own communities, as such access to care and specialty support is desperately needed and can remarkably impact health care outcomes. Moreover, in addition to the direct impact on health care delivery and economics, the intangible benefits of an inpatient dermatology presence are innumerable, as opportunities to promote quality research and improve trainee education also demonstrate our value. These facets together provide a positive perspective on the potential contribution that our field can have on shaping the outlook of hospital medicine. As such, in addition to enjoying the current renaissance of inpatient dermatology, it is imperative that dermatologists build on this momentum and invest in the future of consultative dermatology.

- Albert MR, Mackool BT. A dermatology ward at the beginning of the 20th century. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 1):113-123.

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558.

- Helms AE, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Hospital consultations: time to address an unmet need? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:308-311.

- Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience of a year of adult hospital dermatology consultations. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1150-1156.

- Galimberti F, Guren L, Fernandez AP, et al. Dermatology consultations significantly contribute quality to care of hospitalized patients: a prospective study of dermatology inpatient consults at a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E547-E551.

- Tracey EH, Forrestel A, Rosenbach M, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:835-836.

- Phillips GS, Freites-Martinez A, Hsu M, et al. Inflammatory dermatoses, infections, and drug eruptions are the most common skin conditions in hospitalized cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1102-1109.

- Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Pediatric hospital dermatology: experience with inpatient and consult services at the Mayo Clinic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:433-437.

- Afsar FS. Analysis of pediatric dermatology inpatient consultations in a pediatric teaching hospital. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115:E377-E384.

- McMahon P, Goddard D, Frieden IJ. Pediatric dermatology inpatient consultations: a retrospective study of 427 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:926-931.

- Peñate Y, Borrego L, Hernández N, et al. Pediatric dermatology consultations: a retrospective analysis of inpatient consultations referred to the dermatology service. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:115-118.

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482.

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543.

- Falanga V, Schachner LA, Rae V, et al. Dermatologic consultations in the hospital setting. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1022-1025.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis [published online November 2, 2016]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3816.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528.

- Albert MR, Mackool BT. A dermatology ward at the beginning of the 20th century. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 1):113-123.

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558.

- Helms AE, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Hospital consultations: time to address an unmet need? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:308-311.

- Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience of a year of adult hospital dermatology consultations. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1150-1156.

- Galimberti F, Guren L, Fernandez AP, et al. Dermatology consultations significantly contribute quality to care of hospitalized patients: a prospective study of dermatology inpatient consults at a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E547-E551.

- Tracey EH, Forrestel A, Rosenbach M, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:835-836.

- Phillips GS, Freites-Martinez A, Hsu M, et al. Inflammatory dermatoses, infections, and drug eruptions are the most common skin conditions in hospitalized cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1102-1109.

- Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Pediatric hospital dermatology: experience with inpatient and consult services at the Mayo Clinic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:433-437.

- Afsar FS. Analysis of pediatric dermatology inpatient consultations in a pediatric teaching hospital. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115:E377-E384.

- McMahon P, Goddard D, Frieden IJ. Pediatric dermatology inpatient consultations: a retrospective study of 427 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:926-931.

- Peñate Y, Borrego L, Hernández N, et al. Pediatric dermatology consultations: a retrospective analysis of inpatient consultations referred to the dermatology service. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:115-118.

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482.

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543.

- Falanga V, Schachner LA, Rae V, et al. Dermatologic consultations in the hospital setting. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1022-1025.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis [published online November 2, 2016]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3816.

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:523-528.

Practice Points

- Dermatology inpatient consultation enhances quality of care and reduces health care costs.

- Dermatology input in the inpatient setting leads to a diagnosis change in up to 70% of consultations.

- The majority of dermatologic misdiagnoses by nondermatologists involves common dermatoses such as cellulitis, stasis dermatitis, and hypersensitivity reactions.

Neurologic disease eventually affects half of women and one-third of men

Around one-half of women and one-third of men will develop dementia, stroke, or parkinsonism during their lifetime, based on results from the population-based Rotterdam study published in the Oct. 1 online edition of the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

The study involved 12,102 individuals (57.7% women) who were aged 45 years or older and free from neurologic disease at baseline who were followed for 26 years.

Silvan Licher, MD, and colleagues from the University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands) found that a 45-year-old woman had a 48.2% overall remaining lifetime risk of developing dementia, stroke, or parkinsonism, while a 45-year-old man had a 36.3% lifetime risk.

“There are currently no disease-modifying drugs available for dementia and most causes of parkinsonism, and prevention of stroke is hampered by suboptimal adherence to effective preventive strategies or unmet guideline thresholds,” the authors wrote. “Yet, a delay in onset of these common neurologic diseases by merely a few years could reduce the population burden of these diseases substantially.”

Women aged 45 years had a significantly higher lifetime risk than men of developing dementia (31.4% vs. 18.6% respectively) and stroke (21.6% vs. 19.3%), but the risk of parkinsonism was similar between the sexes.

Women also had a significantly greater lifetime risk of developing more than one neurologic disease, compared with men (4% vs. 3.1%, P less than .001), largely because of the overlap between dementia and stroke.

At age 45 women had the greatest risk of dementia, but as men and women aged, their remaining lifetime risk of dementia increased relative to other neurologic diseases. After age 85 years, 66.6% of first diagnoses in women and 55.6% in men were dementia.

By comparison, first manifestation of stroke was the greatest threat to men aged 45. Men were also at a significantly higher risk for stroke at a younger age – before age 75 years – than were women (8.4% vs. 5.8%).

In the case of parkinsonism, the lifetime risk peaked earlier than it did for dementia and stroke, and was relatively low after the age of 85 years, with no significant differences in risk between men and women.

The authors also considered what effect a delay in disease onset and occurrence might have on remaining lifetime risk for neurologic disease. They found that a 1, 2, or 3-year delay in the onset of all neurologic disease was associated with a 20% reduction in lifetime risk in individuals aged 45 years or older, and a greater than 50% reduction in risk in the very oldest.

A 3-year delay in the onset of dementia reduced the lifetime risk by 15% for both men and women aged 45 years and granted a 30% reduction in risk to those aged 45 years or older.

The Rotterdam study is supported by Erasmus MC and Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly, The Netherlands Genomics Initiative, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission and the Municipality of Rotterdam, the Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Ageing, and the Dutch Heart Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Licher S et al. JNNP. 2018 Oct 1. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318650.

Around one-half of women and one-third of men will develop dementia, stroke, or parkinsonism during their lifetime, based on results from the population-based Rotterdam study published in the Oct. 1 online edition of the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

The study involved 12,102 individuals (57.7% women) who were aged 45 years or older and free from neurologic disease at baseline who were followed for 26 years.

Silvan Licher, MD, and colleagues from the University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands) found that a 45-year-old woman had a 48.2% overall remaining lifetime risk of developing dementia, stroke, or parkinsonism, while a 45-year-old man had a 36.3% lifetime risk.

“There are currently no disease-modifying drugs available for dementia and most causes of parkinsonism, and prevention of stroke is hampered by suboptimal adherence to effective preventive strategies or unmet guideline thresholds,” the authors wrote. “Yet, a delay in onset of these common neurologic diseases by merely a few years could reduce the population burden of these diseases substantially.”

Women aged 45 years had a significantly higher lifetime risk than men of developing dementia (31.4% vs. 18.6% respectively) and stroke (21.6% vs. 19.3%), but the risk of parkinsonism was similar between the sexes.

Women also had a significantly greater lifetime risk of developing more than one neurologic disease, compared with men (4% vs. 3.1%, P less than .001), largely because of the overlap between dementia and stroke.

At age 45 women had the greatest risk of dementia, but as men and women aged, their remaining lifetime risk of dementia increased relative to other neurologic diseases. After age 85 years, 66.6% of first diagnoses in women and 55.6% in men were dementia.

By comparison, first manifestation of stroke was the greatest threat to men aged 45. Men were also at a significantly higher risk for stroke at a younger age – before age 75 years – than were women (8.4% vs. 5.8%).

In the case of parkinsonism, the lifetime risk peaked earlier than it did for dementia and stroke, and was relatively low after the age of 85 years, with no significant differences in risk between men and women.

The authors also considered what effect a delay in disease onset and occurrence might have on remaining lifetime risk for neurologic disease. They found that a 1, 2, or 3-year delay in the onset of all neurologic disease was associated with a 20% reduction in lifetime risk in individuals aged 45 years or older, and a greater than 50% reduction in risk in the very oldest.

A 3-year delay in the onset of dementia reduced the lifetime risk by 15% for both men and women aged 45 years and granted a 30% reduction in risk to those aged 45 years or older.

The Rotterdam study is supported by Erasmus MC and Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly, The Netherlands Genomics Initiative, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission and the Municipality of Rotterdam, the Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Ageing, and the Dutch Heart Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Licher S et al. JNNP. 2018 Oct 1. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318650.

Around one-half of women and one-third of men will develop dementia, stroke, or parkinsonism during their lifetime, based on results from the population-based Rotterdam study published in the Oct. 1 online edition of the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

The study involved 12,102 individuals (57.7% women) who were aged 45 years or older and free from neurologic disease at baseline who were followed for 26 years.

Silvan Licher, MD, and colleagues from the University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands) found that a 45-year-old woman had a 48.2% overall remaining lifetime risk of developing dementia, stroke, or parkinsonism, while a 45-year-old man had a 36.3% lifetime risk.

“There are currently no disease-modifying drugs available for dementia and most causes of parkinsonism, and prevention of stroke is hampered by suboptimal adherence to effective preventive strategies or unmet guideline thresholds,” the authors wrote. “Yet, a delay in onset of these common neurologic diseases by merely a few years could reduce the population burden of these diseases substantially.”

Women aged 45 years had a significantly higher lifetime risk than men of developing dementia (31.4% vs. 18.6% respectively) and stroke (21.6% vs. 19.3%), but the risk of parkinsonism was similar between the sexes.

Women also had a significantly greater lifetime risk of developing more than one neurologic disease, compared with men (4% vs. 3.1%, P less than .001), largely because of the overlap between dementia and stroke.

At age 45 women had the greatest risk of dementia, but as men and women aged, their remaining lifetime risk of dementia increased relative to other neurologic diseases. After age 85 years, 66.6% of first diagnoses in women and 55.6% in men were dementia.

By comparison, first manifestation of stroke was the greatest threat to men aged 45. Men were also at a significantly higher risk for stroke at a younger age – before age 75 years – than were women (8.4% vs. 5.8%).

In the case of parkinsonism, the lifetime risk peaked earlier than it did for dementia and stroke, and was relatively low after the age of 85 years, with no significant differences in risk between men and women.

The authors also considered what effect a delay in disease onset and occurrence might have on remaining lifetime risk for neurologic disease. They found that a 1, 2, or 3-year delay in the onset of all neurologic disease was associated with a 20% reduction in lifetime risk in individuals aged 45 years or older, and a greater than 50% reduction in risk in the very oldest.

A 3-year delay in the onset of dementia reduced the lifetime risk by 15% for both men and women aged 45 years and granted a 30% reduction in risk to those aged 45 years or older.

The Rotterdam study is supported by Erasmus MC and Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly, The Netherlands Genomics Initiative, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission and the Municipality of Rotterdam, the Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Ageing, and the Dutch Heart Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Licher S et al. JNNP. 2018 Oct 1. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318650.

FROM JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY, NEUROSURGERY & PSYCHIATRY

Major finding: A 45-year-old woman has a 48.2% lifetime risk of stroke, dementia, or parkinsonism, while a man has a 36.3% lifetime risk.

Study details: Population-based cohort study in 12,102 individuals.

Disclosures: The Rotterdam study is supported by Erasmus MC and Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly, The Netherlands Genomics Initiative, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission and the Municipality of Rotterdam, the Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Ageing, and the Dutch Heart Foundation. No financial conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Licher S et al. JNNP. 2018 Oct 1. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318650.

We need to reassess our primitive understanding of the venous system

If one includes the entire spectrum of venous disease, it is a more common pathology than peripheral arterial disease. The financial impact of venous disease is substantial. Why, then, has it taken so long to generate enthusiasm for venous disease of the femorocaval and subclaviocaval segments? For years, the endovascular management of venous disease used technology and techniques borrowed from the arterial space; although results were encouraging, it is clear that they varied widely and continue to do so. Management of these vascular beds is very reminiscent of the barrage of devices we have thrown at the superficial femoral artery.

In peripheral arterial disease, there have been much education and research focused on understanding atherosclerosis and its interaction with arterial devices. However, the paucity of investigation and enlightenment in the venous domain is evident when a literature search is performed. Certainly there are data from Comerota et al. showing an increased amount of collagen in the walls of chronically diseased veins. While this is a reasonable start, it is not sufficient data on which to build an entire treatment paradigm. Just like peripheral arterial disease, venous pathology presents in a continuum. Without an in-depth appreciation of the variability of those presentations, it is difficult to envision targeted therapies.

Although vendors have recently engaged in the development of venous-specific devices, it is in great part grounded in expert opinion rather than in hard data. The Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee has made it known that we need more evidence on the efficacy of all venous procedures. Peter Gloviczki, MD, a vascular surgeon at Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn., put it succinctly in an issue of Venous News: “We need to focus on venous research and never forget that whoever owns research owns the disease. We must continue innovation and collaboration, with other venous specialties and with industry.” Truth be told, there doesn’t seem to be much fascination with comprehension of the disease, but there appears to be an enormous drive from a variety of specialties to do procedures.

In July 2015, Gerard O’Sullivan, MD, wrote of a multidisciplinary group in Europe established to develop some standardization in venous stenting guidelines. He describes a “need for consistent guidelines for preoperative imaging, follow-up, anticoagulation duration and type, stent diameter, length into the inferior vena cava and lower end in relation to the internal iliac vein/external iliac vein.” I concur, that this would be utopic. I have not come across such guidelines to date.