User login

Treating Digestive Disease Across the Lifespan

Pediatric gastroenterologists are a vital, yet often overlooked segment of the GI workforce and an important part of AGA’s diverse membership. Per the American Board of Pediatrics, 2,232 pediatricians have been board certified in pediatric gastroenterology since formal certification was first offered in 1990, and AGA Institute Council’s Pediatric Gastroenterology and Developmental Biology Section has nearly 1,900 members.

According to a recently published study in the journal Pediatrics, the pediatric GI workforce is expected to double by 2040, growing at a rate faster than that of most other pediatric subspecialties. This is largely due to the increased scope and complexity of the field driven by scientific advances and the increasing prevalence of digestive and liver diseases in children, including inflammatory bowel and other diseases.

In this month’s Member Spotlight, we highlight Dr. Yoyo Zhang, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Stanford Children’s Health specializing in intestinal and liver transplantation. Her passion for her profession and for improving the lives of her patients shines brightly, and her interview provides fascinating insights into the complexities and rewards of the rapidly expanding field of pediatric gastroenterology.

Also in our November issue, we update you on the FDA’s recent approval of the “next-gen” Cologuard test and query a panel of primary care and GI experts on their thoughts regarding the role that newly FDA-approved (but not yet guideline-recommended) Guardant blood-based CRC screening test should play in CRC screening moving forward.

In our Perspectives feature, we offer expert insights on how to appropriately screen patients for certain rare malignancies. Is it worthwhile screening for pancreatic cancer, and if so, how should it be done? Likewise, diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma is challenging; how best should one evaluate for this in higher-risk populations?

We hope you enjoy all the content in our November issue – as always, thanks for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Pediatric gastroenterologists are a vital, yet often overlooked segment of the GI workforce and an important part of AGA’s diverse membership. Per the American Board of Pediatrics, 2,232 pediatricians have been board certified in pediatric gastroenterology since formal certification was first offered in 1990, and AGA Institute Council’s Pediatric Gastroenterology and Developmental Biology Section has nearly 1,900 members.

According to a recently published study in the journal Pediatrics, the pediatric GI workforce is expected to double by 2040, growing at a rate faster than that of most other pediatric subspecialties. This is largely due to the increased scope and complexity of the field driven by scientific advances and the increasing prevalence of digestive and liver diseases in children, including inflammatory bowel and other diseases.

In this month’s Member Spotlight, we highlight Dr. Yoyo Zhang, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Stanford Children’s Health specializing in intestinal and liver transplantation. Her passion for her profession and for improving the lives of her patients shines brightly, and her interview provides fascinating insights into the complexities and rewards of the rapidly expanding field of pediatric gastroenterology.

Also in our November issue, we update you on the FDA’s recent approval of the “next-gen” Cologuard test and query a panel of primary care and GI experts on their thoughts regarding the role that newly FDA-approved (but not yet guideline-recommended) Guardant blood-based CRC screening test should play in CRC screening moving forward.

In our Perspectives feature, we offer expert insights on how to appropriately screen patients for certain rare malignancies. Is it worthwhile screening for pancreatic cancer, and if so, how should it be done? Likewise, diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma is challenging; how best should one evaluate for this in higher-risk populations?

We hope you enjoy all the content in our November issue – as always, thanks for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Pediatric gastroenterologists are a vital, yet often overlooked segment of the GI workforce and an important part of AGA’s diverse membership. Per the American Board of Pediatrics, 2,232 pediatricians have been board certified in pediatric gastroenterology since formal certification was first offered in 1990, and AGA Institute Council’s Pediatric Gastroenterology and Developmental Biology Section has nearly 1,900 members.

According to a recently published study in the journal Pediatrics, the pediatric GI workforce is expected to double by 2040, growing at a rate faster than that of most other pediatric subspecialties. This is largely due to the increased scope and complexity of the field driven by scientific advances and the increasing prevalence of digestive and liver diseases in children, including inflammatory bowel and other diseases.

In this month’s Member Spotlight, we highlight Dr. Yoyo Zhang, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Stanford Children’s Health specializing in intestinal and liver transplantation. Her passion for her profession and for improving the lives of her patients shines brightly, and her interview provides fascinating insights into the complexities and rewards of the rapidly expanding field of pediatric gastroenterology.

Also in our November issue, we update you on the FDA’s recent approval of the “next-gen” Cologuard test and query a panel of primary care and GI experts on their thoughts regarding the role that newly FDA-approved (but not yet guideline-recommended) Guardant blood-based CRC screening test should play in CRC screening moving forward.

In our Perspectives feature, we offer expert insights on how to appropriately screen patients for certain rare malignancies. Is it worthwhile screening for pancreatic cancer, and if so, how should it be done? Likewise, diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma is challenging; how best should one evaluate for this in higher-risk populations?

We hope you enjoy all the content in our November issue – as always, thanks for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Screening Options for Rare Malignancies

Dear colleagues,

As gastroenterologists and endoscopists, we spend significant time preventing and diagnosing GI malignancies.

For instance, is it worthwhile screening for pancreatic cancer, and, if so, how should this be done? Likewise, diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma is challenging; how best should one evaluate for this in higher risk populations, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis? And what about the costs, financial and otherwise, associated with screening?

In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. Darshan Kothari and Dr. Daniel Bernstein discuss their approach to pancreatic cancer screening, including who is eligible, the preferred screening modalities, and the barriers to screening. In the accompanying perspective, Dr. Aparna Goel and Dr. Judah Kupferman focus on cholangiocarcinoma screening, identifying high-risk populations and discussing some of the concerns with screening, necessitating shared decision-making.

We welcome your thoughts on this issue. Share with us on X at @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, and chief of endoscopy at West Haven VA Medical Center, both in Connecticut. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

An Approach to Pancreatic Cancer Screening

BY DANIEL A. BERNSTEIN, MD, AND DARSHAN KOTHARI, MD

Pancreatic cancer carries a dismal prognosis, now accounting for the third-most cancer-related mortality in the United States. A small proportion of patients are diagnosed at a local stage of disease, with over half found to have metastatic disease at presentation. Given the low overall incidence and lifetime risk in the general population, population-based screening is not justified.

About 10% of cases of pancreas cancer are associated with germ-line mutations and/or with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. Several academic societies and expert committees now recommend regular screening for pancreatic cancer in patients who are considered high-risk individuals, as they carry a fivefold relative risk for pancreatic cancer. Moreover, studies suggest that screening has the potential to identify early-stage resectable disease and decrease mortality in this patient population.

Patients who benefit from pancreatic cancer screening are those who carry an increased lifetime risk (in excess of 5%) of pancreatic cancer. High-risk individuals include those with germ-line mutations and/or those with a family history of pancreatic cancer in first-degree relatives. Consensus guidelines by the International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Consortium and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy provide medical centers with detailed recommendations on who and when to start screening.

High-risk individuals fall into three categories:

- Patients with high-risk germline mutations including: familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome (CDKN2A), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndromes (BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11), and hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1 and SPINK1)

- Patients with low- to moderate-risk germ-line mutations with at least one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer: Lynch Syndrome (particularly MLH1 mutation), ataxia-telangiectasia (ATM), or Li-Fraumeni syndrome (p53)

- Patients with one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer who in turn has one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer (eg, a patient’s mother and maternal aunt or a patient’s father and patient’s sister)

Consistent with established guidelines, we recommend screening for high-risk patients beginning at age 50, or 10 years before the youngest age at which pancreas cancer was diagnosed in an affected relative. Screening is recommended earlier in patients with particularly high risk: at age 40 for patients with CDKN2A and STKI11 mutations and age 40 for patients with PRSS1 mutation or 20 years after the first attack of acute pancreatitis. For patients with a strong family history of pancreas cancer, we recommend comprehensive evaluation by a certified genetic counselor at a high-volume cancer center.

In practice, patients at our institution who are identified as high risk based on the above criteria are referred for an initial consultation at our pancreas center. In most cases, this should occur no sooner than 5 years prior to the recommended starting age for screening. All patients who are identified as high risk should be screened annually for diabetes given the growing evidence base supporting an association between new-onset diabetes and pancreatic cancer.

After an initial visit and discussion of the risks and benefits of screening, most screening protocols start with a baseline endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance abdomen with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP), which will be repeated annually or sooner as the clinical condition warrants. A sooner-interval EUS should be considered for patients already undergoing screening who are newly found to have diabetes.

At our institution, we start with an in-person clinic evaluation followed by EUS. Thereafter, patients undergo MRI/MRCP (synchronized with a same-day clinic visit) alternating with EUS every 6 months to ensure patients are seen twice a year, though there is no specific data to support this approach. Non-diabetics also undergo yearly diabetes screening which will trigger an EUS if patients become diabetic.

We engage in shared decision-making with our high-risk individuals undergoing pancreatic cancer screening and at each visit we review their concurrent medical conditions and suitability to continue screening. We consider discontinuing screening after age 75, at the onset of any life-limiting illness, or after a discussion of risks and benefits if comorbidities lead to a substantial deterioration in a patient’s overall health status.

While a growing body of evidence exists to support the application of pancreatic cancer screening in high-risk individuals, this preventive service remains underutilized. Recent analysis of the screening cohort at our institution showed a demographically homogeneous group of mostly highly educated, high-income White females. These findings are consistent with the patient cohorts described in other pancreatic cancer screening programs and represent only a fraction of people who would qualify for pancreatic cancer screening.

A survey of patients undergoing screening at our institution identified cost, travel, and time associated with pancreatic cancer screening to be frequent challenges to participation. Further studies are needed to fully explore the barriers and psychological burden of pancreas cancer screening in high-risk individuals, and to identify ways to enrich the cohort of patients undergoing screening. This may involve novel methods to identify family members of patients with a new diagnosis of pancreas cancer and increasing health literacy around pancreatic cancer screening among patients and providers.

Pancreatic cancer screening has the potential to identify early-stage disease in patients who are at high risk because of germ-line mutations and/or family history. We recommend that patients engage in pancreatic cancer screening at high-volume centers with well-supported oncology, genetics, and research infrastructure.

Dr. Bernstein is a gastroenterology fellow at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Kothari is an associate professor of medicine in gastroenterology and hepatology at Duke University School of Medicine.

Screening for Cholangiocarcinoma

BY JUDAH KUPFERMAN, MD, AND APARNA GOEL, MD

Cholangiocarcinoma is a rare but aggressive cancer of the bile ducts that poses many diagnostic challenges. Approximately 3% of gastrointestinal cancers are attributed to cholangiocarcinoma, and while the annual incidence of disease in the United States is about 1.26 per 100,000 people, the incidence of intrahepatic disease has been rising considerably.1,2 Screening for cholangiocarcinoma is reserved for high-risk individuals — such as those with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC), and biliary tract disorders such as choledochal cysts or Caroli’s disease. The goal is to balance the benefits of early diagnosis with the costs and risks associated with screening, particularly given the limitations of available tools like MRI with cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which has a sensitivity of 70%-85%. In general, we recommend annual cholangiocarcinoma screening for high-risk individuals with MRI and MRCP as well as with cancer antigen (CA) 19-9. .

Screening in Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

The lifetime risk of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with PSC is 10%-15% with an annual risk of 0.5%-1.5%. In our experience, this is often the most feared complication for PSC patients, even more so than the risk of liver transplantation. We recommend annual MRI with MRCP in addition to CA 19-9 for patients with PSC in the first decade of their diagnosis, as most cancers are diagnosed during this period. If a patient’s imaging has remained stable for over a decade and there is minimal hepatic fibrosis, we discuss the option of reducing screening frequency to every 2 years to minimize costs and exposure to MRI contrast risks.

If MRI reveals a concerning new large duct stricture, we will evaluate this with an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), as differentiating benign and malignant strictures is quite challenging with MRI. We generally recommend ERCP with brush cytology and fluorescence in situ hybridization to improve diagnostic yield. Depending on imaging findings and location of the new large duct stricture, we may consider cholangioscopy during ERCP for direct visualization of the bile duct and directed tissue biopsies. Unfortunately, even in young, asymptomatic patients who undergo regular screening, cholangiocarcinoma is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Screening in Patients with Secondary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Patients with SSC may develop cholangiocarcinoma because of chronic inflammatory and fibrotic processes, such as IgG4-associated cholangiopathy, sarcoidosis, ischemic cholangiopathy, cystic fibrosis, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, severe sepsis (as recently seen from SARS-CoV-2), surgical complications, or other etiologies. When the condition is reversible, such as with IgG4-associated cholangiopathy, cancer screening may not be necessary. However, when irreversible damage occurs, the cancer risk increases, though it varies by disease type and severity. In most cases, we recommend routine screening for cholangiocarcinoma with MRI and CA 19-9 in this population.

Screening in Patients with Biliary Tract Disorders

Biliary tract disorders such as choledochal cysts and Caroli’s disease also harbor an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Choledochal cysts are congenital cystic dilations of the bile duct that have a 10%-30% lifetime risk of malignant transformation to cholangiocarcinoma. Surgical intervention to remove the cyst is often recommended because of this high risk. However, some patients may be unable or unwilling to undergo this surgery or they may have residual cysts. We recommend ongoing screening with MRI and CA 19-9 for these patients. Similarly, Caroli’s disease is a congenital disease associated with intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct cysts and associated with a 5%-15% lifetime risk of cholangiocarcinoma. MRI with MRCP and CA 19-9 should be performed routinely for patients with Caroli’s disease and syndrome.

Risks and Challenges in Cholangiocarcinoma Screening

While MRI with MRCP is the gold standard for cholangiocarcinoma screening, its limitations must be carefully considered. One growing concern is the potential for gadolinium retention in the brain, bones, or skin following repeated MRI scans. Though the long-term effects of gadolinium retention are not fully understood, we factor this into screening decisions, particularly for younger patients who may undergo decades of regular imaging.

MRI is not always feasible for certain patients, including those with metal implants, on hemodialysis, or with severe allergic reactions. In such cases, CT or ultrasound may serve as alternatives, though with lower sensitivity for detecting cholangiocarcinoma. Additionally, claustrophobia during MRI can be addressed with sedation, but this underscores the importance of shared decision-making.

From our perspective, cholangiocarcinoma screening in high-risk patients is crucial but not without challenges. Our current screening methods, while essential, are far from perfect, often missing early cancers or leading to unnecessary interventions. Because of these limitations, the window for treatment of localized disease can easily be missed. In our practice, we tailor screening strategies to each patient’s specific needs, weighing the potential benefits against the risks, costs, and the inherent uncertainty of early detection tools. We believe it is essential to involve patients in this decision-making process to provide a balanced, individualized approach that considers both clinical evidence and the personal preferences of each person.

Dr. Kupferman is a gastroenterology fellow at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. Dr. Goel is a transplant hepatologist and a clinical associate professor in gastroenterology & hepatology at Stanford.

References

1. Vithayathil M and Khan SA. J Hepatol. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.07.022.

2. Patel N and Benipal B. Cureus. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3962.

Dear colleagues,

As gastroenterologists and endoscopists, we spend significant time preventing and diagnosing GI malignancies.

For instance, is it worthwhile screening for pancreatic cancer, and, if so, how should this be done? Likewise, diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma is challenging; how best should one evaluate for this in higher risk populations, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis? And what about the costs, financial and otherwise, associated with screening?

In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. Darshan Kothari and Dr. Daniel Bernstein discuss their approach to pancreatic cancer screening, including who is eligible, the preferred screening modalities, and the barriers to screening. In the accompanying perspective, Dr. Aparna Goel and Dr. Judah Kupferman focus on cholangiocarcinoma screening, identifying high-risk populations and discussing some of the concerns with screening, necessitating shared decision-making.

We welcome your thoughts on this issue. Share with us on X at @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, and chief of endoscopy at West Haven VA Medical Center, both in Connecticut. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

An Approach to Pancreatic Cancer Screening

BY DANIEL A. BERNSTEIN, MD, AND DARSHAN KOTHARI, MD

Pancreatic cancer carries a dismal prognosis, now accounting for the third-most cancer-related mortality in the United States. A small proportion of patients are diagnosed at a local stage of disease, with over half found to have metastatic disease at presentation. Given the low overall incidence and lifetime risk in the general population, population-based screening is not justified.

About 10% of cases of pancreas cancer are associated with germ-line mutations and/or with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. Several academic societies and expert committees now recommend regular screening for pancreatic cancer in patients who are considered high-risk individuals, as they carry a fivefold relative risk for pancreatic cancer. Moreover, studies suggest that screening has the potential to identify early-stage resectable disease and decrease mortality in this patient population.

Patients who benefit from pancreatic cancer screening are those who carry an increased lifetime risk (in excess of 5%) of pancreatic cancer. High-risk individuals include those with germ-line mutations and/or those with a family history of pancreatic cancer in first-degree relatives. Consensus guidelines by the International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Consortium and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy provide medical centers with detailed recommendations on who and when to start screening.

High-risk individuals fall into three categories:

- Patients with high-risk germline mutations including: familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome (CDKN2A), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndromes (BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11), and hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1 and SPINK1)

- Patients with low- to moderate-risk germ-line mutations with at least one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer: Lynch Syndrome (particularly MLH1 mutation), ataxia-telangiectasia (ATM), or Li-Fraumeni syndrome (p53)

- Patients with one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer who in turn has one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer (eg, a patient’s mother and maternal aunt or a patient’s father and patient’s sister)

Consistent with established guidelines, we recommend screening for high-risk patients beginning at age 50, or 10 years before the youngest age at which pancreas cancer was diagnosed in an affected relative. Screening is recommended earlier in patients with particularly high risk: at age 40 for patients with CDKN2A and STKI11 mutations and age 40 for patients with PRSS1 mutation or 20 years after the first attack of acute pancreatitis. For patients with a strong family history of pancreas cancer, we recommend comprehensive evaluation by a certified genetic counselor at a high-volume cancer center.

In practice, patients at our institution who are identified as high risk based on the above criteria are referred for an initial consultation at our pancreas center. In most cases, this should occur no sooner than 5 years prior to the recommended starting age for screening. All patients who are identified as high risk should be screened annually for diabetes given the growing evidence base supporting an association between new-onset diabetes and pancreatic cancer.

After an initial visit and discussion of the risks and benefits of screening, most screening protocols start with a baseline endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance abdomen with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP), which will be repeated annually or sooner as the clinical condition warrants. A sooner-interval EUS should be considered for patients already undergoing screening who are newly found to have diabetes.

At our institution, we start with an in-person clinic evaluation followed by EUS. Thereafter, patients undergo MRI/MRCP (synchronized with a same-day clinic visit) alternating with EUS every 6 months to ensure patients are seen twice a year, though there is no specific data to support this approach. Non-diabetics also undergo yearly diabetes screening which will trigger an EUS if patients become diabetic.

We engage in shared decision-making with our high-risk individuals undergoing pancreatic cancer screening and at each visit we review their concurrent medical conditions and suitability to continue screening. We consider discontinuing screening after age 75, at the onset of any life-limiting illness, or after a discussion of risks and benefits if comorbidities lead to a substantial deterioration in a patient’s overall health status.

While a growing body of evidence exists to support the application of pancreatic cancer screening in high-risk individuals, this preventive service remains underutilized. Recent analysis of the screening cohort at our institution showed a demographically homogeneous group of mostly highly educated, high-income White females. These findings are consistent with the patient cohorts described in other pancreatic cancer screening programs and represent only a fraction of people who would qualify for pancreatic cancer screening.

A survey of patients undergoing screening at our institution identified cost, travel, and time associated with pancreatic cancer screening to be frequent challenges to participation. Further studies are needed to fully explore the barriers and psychological burden of pancreas cancer screening in high-risk individuals, and to identify ways to enrich the cohort of patients undergoing screening. This may involve novel methods to identify family members of patients with a new diagnosis of pancreas cancer and increasing health literacy around pancreatic cancer screening among patients and providers.

Pancreatic cancer screening has the potential to identify early-stage disease in patients who are at high risk because of germ-line mutations and/or family history. We recommend that patients engage in pancreatic cancer screening at high-volume centers with well-supported oncology, genetics, and research infrastructure.

Dr. Bernstein is a gastroenterology fellow at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Kothari is an associate professor of medicine in gastroenterology and hepatology at Duke University School of Medicine.

Screening for Cholangiocarcinoma

BY JUDAH KUPFERMAN, MD, AND APARNA GOEL, MD

Cholangiocarcinoma is a rare but aggressive cancer of the bile ducts that poses many diagnostic challenges. Approximately 3% of gastrointestinal cancers are attributed to cholangiocarcinoma, and while the annual incidence of disease in the United States is about 1.26 per 100,000 people, the incidence of intrahepatic disease has been rising considerably.1,2 Screening for cholangiocarcinoma is reserved for high-risk individuals — such as those with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC), and biliary tract disorders such as choledochal cysts or Caroli’s disease. The goal is to balance the benefits of early diagnosis with the costs and risks associated with screening, particularly given the limitations of available tools like MRI with cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which has a sensitivity of 70%-85%. In general, we recommend annual cholangiocarcinoma screening for high-risk individuals with MRI and MRCP as well as with cancer antigen (CA) 19-9. .

Screening in Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

The lifetime risk of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with PSC is 10%-15% with an annual risk of 0.5%-1.5%. In our experience, this is often the most feared complication for PSC patients, even more so than the risk of liver transplantation. We recommend annual MRI with MRCP in addition to CA 19-9 for patients with PSC in the first decade of their diagnosis, as most cancers are diagnosed during this period. If a patient’s imaging has remained stable for over a decade and there is minimal hepatic fibrosis, we discuss the option of reducing screening frequency to every 2 years to minimize costs and exposure to MRI contrast risks.

If MRI reveals a concerning new large duct stricture, we will evaluate this with an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), as differentiating benign and malignant strictures is quite challenging with MRI. We generally recommend ERCP with brush cytology and fluorescence in situ hybridization to improve diagnostic yield. Depending on imaging findings and location of the new large duct stricture, we may consider cholangioscopy during ERCP for direct visualization of the bile duct and directed tissue biopsies. Unfortunately, even in young, asymptomatic patients who undergo regular screening, cholangiocarcinoma is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Screening in Patients with Secondary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Patients with SSC may develop cholangiocarcinoma because of chronic inflammatory and fibrotic processes, such as IgG4-associated cholangiopathy, sarcoidosis, ischemic cholangiopathy, cystic fibrosis, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, severe sepsis (as recently seen from SARS-CoV-2), surgical complications, or other etiologies. When the condition is reversible, such as with IgG4-associated cholangiopathy, cancer screening may not be necessary. However, when irreversible damage occurs, the cancer risk increases, though it varies by disease type and severity. In most cases, we recommend routine screening for cholangiocarcinoma with MRI and CA 19-9 in this population.

Screening in Patients with Biliary Tract Disorders

Biliary tract disorders such as choledochal cysts and Caroli’s disease also harbor an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Choledochal cysts are congenital cystic dilations of the bile duct that have a 10%-30% lifetime risk of malignant transformation to cholangiocarcinoma. Surgical intervention to remove the cyst is often recommended because of this high risk. However, some patients may be unable or unwilling to undergo this surgery or they may have residual cysts. We recommend ongoing screening with MRI and CA 19-9 for these patients. Similarly, Caroli’s disease is a congenital disease associated with intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct cysts and associated with a 5%-15% lifetime risk of cholangiocarcinoma. MRI with MRCP and CA 19-9 should be performed routinely for patients with Caroli’s disease and syndrome.

Risks and Challenges in Cholangiocarcinoma Screening

While MRI with MRCP is the gold standard for cholangiocarcinoma screening, its limitations must be carefully considered. One growing concern is the potential for gadolinium retention in the brain, bones, or skin following repeated MRI scans. Though the long-term effects of gadolinium retention are not fully understood, we factor this into screening decisions, particularly for younger patients who may undergo decades of regular imaging.

MRI is not always feasible for certain patients, including those with metal implants, on hemodialysis, or with severe allergic reactions. In such cases, CT or ultrasound may serve as alternatives, though with lower sensitivity for detecting cholangiocarcinoma. Additionally, claustrophobia during MRI can be addressed with sedation, but this underscores the importance of shared decision-making.

From our perspective, cholangiocarcinoma screening in high-risk patients is crucial but not without challenges. Our current screening methods, while essential, are far from perfect, often missing early cancers or leading to unnecessary interventions. Because of these limitations, the window for treatment of localized disease can easily be missed. In our practice, we tailor screening strategies to each patient’s specific needs, weighing the potential benefits against the risks, costs, and the inherent uncertainty of early detection tools. We believe it is essential to involve patients in this decision-making process to provide a balanced, individualized approach that considers both clinical evidence and the personal preferences of each person.

Dr. Kupferman is a gastroenterology fellow at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. Dr. Goel is a transplant hepatologist and a clinical associate professor in gastroenterology & hepatology at Stanford.

References

1. Vithayathil M and Khan SA. J Hepatol. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.07.022.

2. Patel N and Benipal B. Cureus. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3962.

Dear colleagues,

As gastroenterologists and endoscopists, we spend significant time preventing and diagnosing GI malignancies.

For instance, is it worthwhile screening for pancreatic cancer, and, if so, how should this be done? Likewise, diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma is challenging; how best should one evaluate for this in higher risk populations, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis? And what about the costs, financial and otherwise, associated with screening?

In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. Darshan Kothari and Dr. Daniel Bernstein discuss their approach to pancreatic cancer screening, including who is eligible, the preferred screening modalities, and the barriers to screening. In the accompanying perspective, Dr. Aparna Goel and Dr. Judah Kupferman focus on cholangiocarcinoma screening, identifying high-risk populations and discussing some of the concerns with screening, necessitating shared decision-making.

We welcome your thoughts on this issue. Share with us on X at @AGA_GIHN.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, and chief of endoscopy at West Haven VA Medical Center, both in Connecticut. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

An Approach to Pancreatic Cancer Screening

BY DANIEL A. BERNSTEIN, MD, AND DARSHAN KOTHARI, MD

Pancreatic cancer carries a dismal prognosis, now accounting for the third-most cancer-related mortality in the United States. A small proportion of patients are diagnosed at a local stage of disease, with over half found to have metastatic disease at presentation. Given the low overall incidence and lifetime risk in the general population, population-based screening is not justified.

About 10% of cases of pancreas cancer are associated with germ-line mutations and/or with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. Several academic societies and expert committees now recommend regular screening for pancreatic cancer in patients who are considered high-risk individuals, as they carry a fivefold relative risk for pancreatic cancer. Moreover, studies suggest that screening has the potential to identify early-stage resectable disease and decrease mortality in this patient population.

Patients who benefit from pancreatic cancer screening are those who carry an increased lifetime risk (in excess of 5%) of pancreatic cancer. High-risk individuals include those with germ-line mutations and/or those with a family history of pancreatic cancer in first-degree relatives. Consensus guidelines by the International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Consortium and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy provide medical centers with detailed recommendations on who and when to start screening.

High-risk individuals fall into three categories:

- Patients with high-risk germline mutations including: familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome (CDKN2A), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndromes (BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11), and hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1 and SPINK1)

- Patients with low- to moderate-risk germ-line mutations with at least one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer: Lynch Syndrome (particularly MLH1 mutation), ataxia-telangiectasia (ATM), or Li-Fraumeni syndrome (p53)

- Patients with one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer who in turn has one first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer (eg, a patient’s mother and maternal aunt or a patient’s father and patient’s sister)

Consistent with established guidelines, we recommend screening for high-risk patients beginning at age 50, or 10 years before the youngest age at which pancreas cancer was diagnosed in an affected relative. Screening is recommended earlier in patients with particularly high risk: at age 40 for patients with CDKN2A and STKI11 mutations and age 40 for patients with PRSS1 mutation or 20 years after the first attack of acute pancreatitis. For patients with a strong family history of pancreas cancer, we recommend comprehensive evaluation by a certified genetic counselor at a high-volume cancer center.

In practice, patients at our institution who are identified as high risk based on the above criteria are referred for an initial consultation at our pancreas center. In most cases, this should occur no sooner than 5 years prior to the recommended starting age for screening. All patients who are identified as high risk should be screened annually for diabetes given the growing evidence base supporting an association between new-onset diabetes and pancreatic cancer.

After an initial visit and discussion of the risks and benefits of screening, most screening protocols start with a baseline endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance abdomen with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP), which will be repeated annually or sooner as the clinical condition warrants. A sooner-interval EUS should be considered for patients already undergoing screening who are newly found to have diabetes.

At our institution, we start with an in-person clinic evaluation followed by EUS. Thereafter, patients undergo MRI/MRCP (synchronized with a same-day clinic visit) alternating with EUS every 6 months to ensure patients are seen twice a year, though there is no specific data to support this approach. Non-diabetics also undergo yearly diabetes screening which will trigger an EUS if patients become diabetic.

We engage in shared decision-making with our high-risk individuals undergoing pancreatic cancer screening and at each visit we review their concurrent medical conditions and suitability to continue screening. We consider discontinuing screening after age 75, at the onset of any life-limiting illness, or after a discussion of risks and benefits if comorbidities lead to a substantial deterioration in a patient’s overall health status.

While a growing body of evidence exists to support the application of pancreatic cancer screening in high-risk individuals, this preventive service remains underutilized. Recent analysis of the screening cohort at our institution showed a demographically homogeneous group of mostly highly educated, high-income White females. These findings are consistent with the patient cohorts described in other pancreatic cancer screening programs and represent only a fraction of people who would qualify for pancreatic cancer screening.

A survey of patients undergoing screening at our institution identified cost, travel, and time associated with pancreatic cancer screening to be frequent challenges to participation. Further studies are needed to fully explore the barriers and psychological burden of pancreas cancer screening in high-risk individuals, and to identify ways to enrich the cohort of patients undergoing screening. This may involve novel methods to identify family members of patients with a new diagnosis of pancreas cancer and increasing health literacy around pancreatic cancer screening among patients and providers.

Pancreatic cancer screening has the potential to identify early-stage disease in patients who are at high risk because of germ-line mutations and/or family history. We recommend that patients engage in pancreatic cancer screening at high-volume centers with well-supported oncology, genetics, and research infrastructure.

Dr. Bernstein is a gastroenterology fellow at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Kothari is an associate professor of medicine in gastroenterology and hepatology at Duke University School of Medicine.

Screening for Cholangiocarcinoma

BY JUDAH KUPFERMAN, MD, AND APARNA GOEL, MD

Cholangiocarcinoma is a rare but aggressive cancer of the bile ducts that poses many diagnostic challenges. Approximately 3% of gastrointestinal cancers are attributed to cholangiocarcinoma, and while the annual incidence of disease in the United States is about 1.26 per 100,000 people, the incidence of intrahepatic disease has been rising considerably.1,2 Screening for cholangiocarcinoma is reserved for high-risk individuals — such as those with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC), and biliary tract disorders such as choledochal cysts or Caroli’s disease. The goal is to balance the benefits of early diagnosis with the costs and risks associated with screening, particularly given the limitations of available tools like MRI with cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which has a sensitivity of 70%-85%. In general, we recommend annual cholangiocarcinoma screening for high-risk individuals with MRI and MRCP as well as with cancer antigen (CA) 19-9. .

Screening in Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

The lifetime risk of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with PSC is 10%-15% with an annual risk of 0.5%-1.5%. In our experience, this is often the most feared complication for PSC patients, even more so than the risk of liver transplantation. We recommend annual MRI with MRCP in addition to CA 19-9 for patients with PSC in the first decade of their diagnosis, as most cancers are diagnosed during this period. If a patient’s imaging has remained stable for over a decade and there is minimal hepatic fibrosis, we discuss the option of reducing screening frequency to every 2 years to minimize costs and exposure to MRI contrast risks.

If MRI reveals a concerning new large duct stricture, we will evaluate this with an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), as differentiating benign and malignant strictures is quite challenging with MRI. We generally recommend ERCP with brush cytology and fluorescence in situ hybridization to improve diagnostic yield. Depending on imaging findings and location of the new large duct stricture, we may consider cholangioscopy during ERCP for direct visualization of the bile duct and directed tissue biopsies. Unfortunately, even in young, asymptomatic patients who undergo regular screening, cholangiocarcinoma is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Screening in Patients with Secondary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Patients with SSC may develop cholangiocarcinoma because of chronic inflammatory and fibrotic processes, such as IgG4-associated cholangiopathy, sarcoidosis, ischemic cholangiopathy, cystic fibrosis, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, severe sepsis (as recently seen from SARS-CoV-2), surgical complications, or other etiologies. When the condition is reversible, such as with IgG4-associated cholangiopathy, cancer screening may not be necessary. However, when irreversible damage occurs, the cancer risk increases, though it varies by disease type and severity. In most cases, we recommend routine screening for cholangiocarcinoma with MRI and CA 19-9 in this population.

Screening in Patients with Biliary Tract Disorders

Biliary tract disorders such as choledochal cysts and Caroli’s disease also harbor an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Choledochal cysts are congenital cystic dilations of the bile duct that have a 10%-30% lifetime risk of malignant transformation to cholangiocarcinoma. Surgical intervention to remove the cyst is often recommended because of this high risk. However, some patients may be unable or unwilling to undergo this surgery or they may have residual cysts. We recommend ongoing screening with MRI and CA 19-9 for these patients. Similarly, Caroli’s disease is a congenital disease associated with intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct cysts and associated with a 5%-15% lifetime risk of cholangiocarcinoma. MRI with MRCP and CA 19-9 should be performed routinely for patients with Caroli’s disease and syndrome.

Risks and Challenges in Cholangiocarcinoma Screening

While MRI with MRCP is the gold standard for cholangiocarcinoma screening, its limitations must be carefully considered. One growing concern is the potential for gadolinium retention in the brain, bones, or skin following repeated MRI scans. Though the long-term effects of gadolinium retention are not fully understood, we factor this into screening decisions, particularly for younger patients who may undergo decades of regular imaging.

MRI is not always feasible for certain patients, including those with metal implants, on hemodialysis, or with severe allergic reactions. In such cases, CT or ultrasound may serve as alternatives, though with lower sensitivity for detecting cholangiocarcinoma. Additionally, claustrophobia during MRI can be addressed with sedation, but this underscores the importance of shared decision-making.

From our perspective, cholangiocarcinoma screening in high-risk patients is crucial but not without challenges. Our current screening methods, while essential, are far from perfect, often missing early cancers or leading to unnecessary interventions. Because of these limitations, the window for treatment of localized disease can easily be missed. In our practice, we tailor screening strategies to each patient’s specific needs, weighing the potential benefits against the risks, costs, and the inherent uncertainty of early detection tools. We believe it is essential to involve patients in this decision-making process to provide a balanced, individualized approach that considers both clinical evidence and the personal preferences of each person.

Dr. Kupferman is a gastroenterology fellow at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. Dr. Goel is a transplant hepatologist and a clinical associate professor in gastroenterology & hepatology at Stanford.

References

1. Vithayathil M and Khan SA. J Hepatol. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.07.022.

2. Patel N and Benipal B. Cureus. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3962.

Medical, Endoscopic, and Surgical Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a frequently encountered condition, and rising annually.1 A recent meta-analysis suggests nearly 14% (1.03 billion) of the population are affected worldwide. Differences may range by region from 12% in Latin America to 20% in North America, and by country from 4% in China to 23% in Turkey.1 In the United States, 21% of the population are afflicted with weekly GERD symptoms.2 Novel medical therapies and endoscopic options provide clinicians with opportunities to help patients with GERD.3

Diagnosis

Definition

GERD was originally defined by the Montreal consensus as a condition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications.4 Heartburn and regurgitation are common symptoms of GERD, with a sensitivity of 30%-76% and specificity of 62%-96% for erosive esophagitis (EE), which occurs when the reflux of stomach content causes esophageal mucosal breaks.5 The presence of characteristic mucosal injury observed during an upper endoscopy or abnormal esophageal acid exposure on ambulatory reflux monitoring are objective evidence of GERD. A trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) may function as a diagnostic test for patients exhibiting the typical symptoms of GERD without any alarm symptoms.3,6

Endoscopic Evaluation and Confirmation

The 2022 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) clinical practice update recommends diagnostic endoscopy, after PPIs are stopped for 2-4 weeks, in patients whose GERD symptoms do not respond adequately to an empiric trial of a PPI.3 Those with GERD and alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, bleeding, and vomiting should undergo endoscopy as soon as possible. Endoscopic findings of EE (Los Angeles Grade B or more severe) and long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (> 3-cm segment with intestinal metaplasia on biopsy) are diagnostic of GERD.3

Reflux Monitoring

With ambulatory reflux monitoring (pH or impedance-pH), esophageal acid exposure (or neutral refluxate in impedance testing) can be measured to confirm GERD diagnosis and to correlate symptoms with reflux episodes. Patients with atypical GERD symptoms or patients with a confirmed diagnosis of GERD whose symptoms have not improved sufficiently with twice-daily PPI therapy should have esophageal impedance-pH monitoring while on PPIs.6,7

Esophageal Manometry

High-resolution esophageal manometry can be used to assess motility abnormalities associated with GERD.

Although no manometric abnormality is unique to GERD, weak lower esophageal sphincter (LES) resting pressure and ineffective esophageal motility frequently coexist with severe GERD.6

Manometry is particularly useful in patients considering surgical or endoscopic anti-reflux procedures to evaluate for achalasia,3 an important contraindication to surgery.

Medical Management

Management of GERD requires a multidisciplinary and personalized approach based on symptom presentation, body mass index, endoscopic findings (e.g., presence of EE, Barrett’s esophagus, hiatal hernia), and physiological abnormalities (e.g., gastroparesis or ineffective motility).3

Lifestyle Modifications

Recommended lifestyle modifications include weight loss for patients with obesity, stress reduction, tobacco and alcohol cessation, elevating the head of the bed, staying upright during and after meals, avoidance of food intake < 3 hours before bedtime, and cessation of foods that potentially aggravate reflux symptoms such as coffee, chocolate, carbonated beverages, spicy foods, acidic foods, and foods with high fat content.6,8

Medications

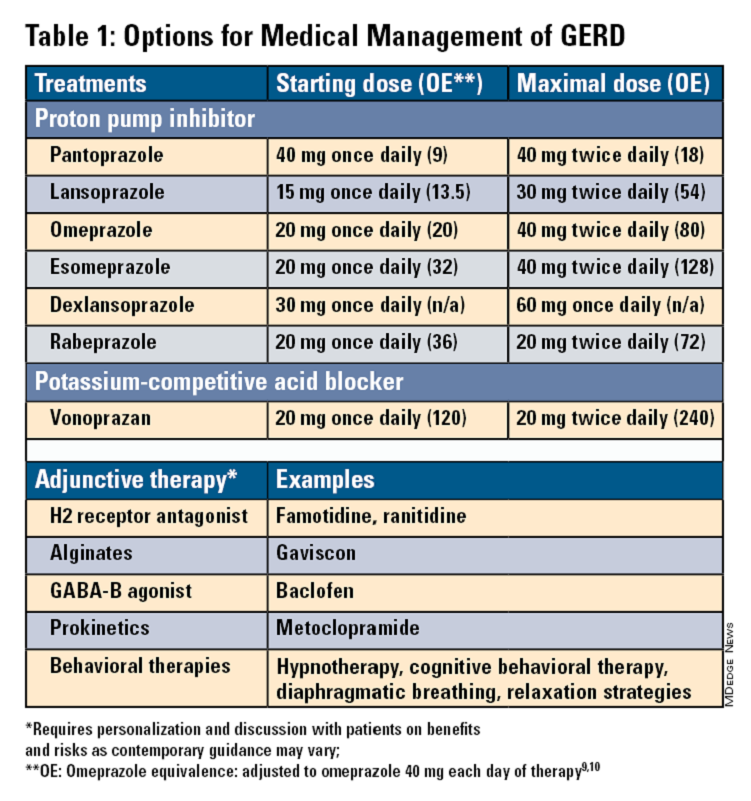

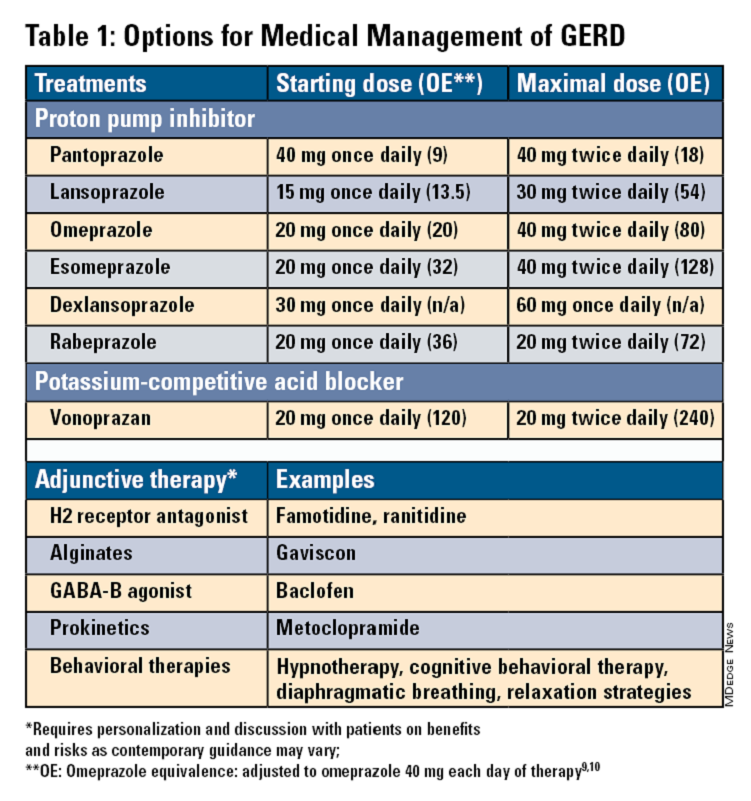

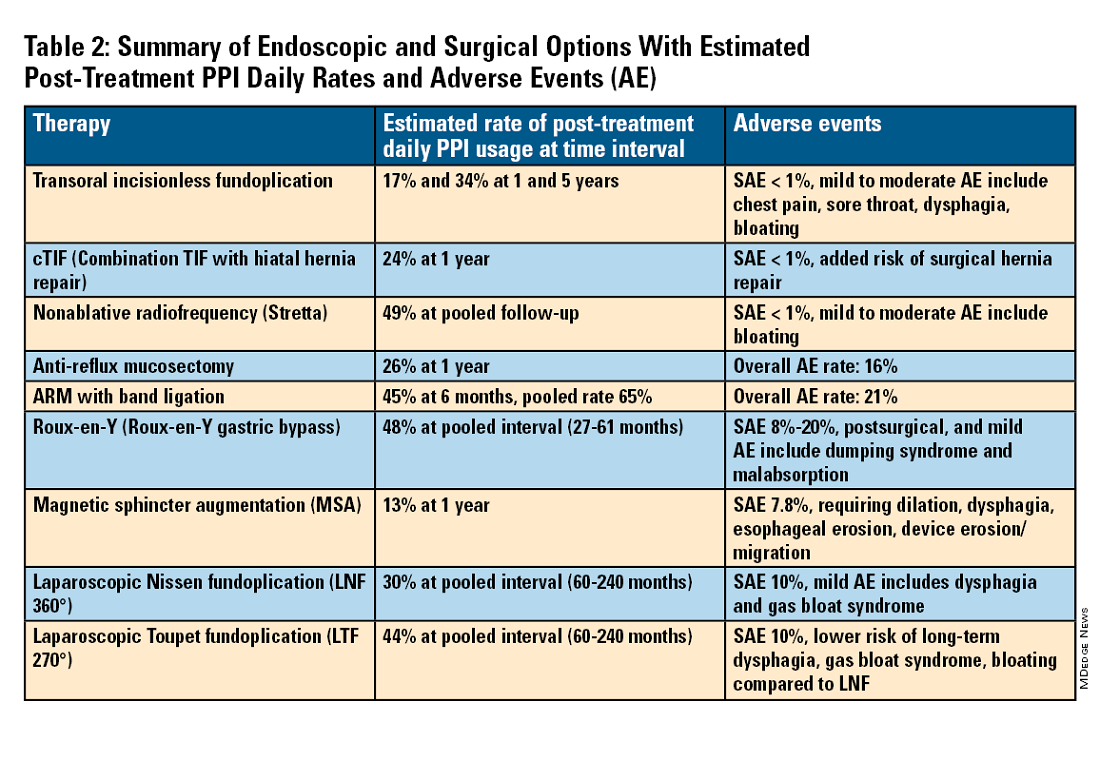

Pharmacologic therapy for GERD includes medications that primarily aim to neutralize or reduce gastric acid -- we summarize options in Table 1.3,8

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Most guidelines suggest a trial of 4-8 weeks of once-daily enteric-coated PPI before meals in patients with typical GERD symptoms and no alarm symptoms. Escalation to double-dose PPI may be considered in the case of persistent symptoms. The relative potencies of standard-dose pantoprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole are presented in Table 1.9 When a PPI switch is needed, rabeprazole may be considered as it is a PPI that does not rely on CYP2C19 for primary metabolism.9

Acid suppression should be weaned down to the lowest effective dose or converted to H2RAs or other antacids once symptoms are sufficiently controlled unless patients have EE, Barrett’s esophagus, or peptic stricture.3 Patients with severe GERD may require long-term PPI therapy or an invasive anti-reflux procedure.

Recent studies have shown that potassium-competitive acid blockers (PCAB) like vonoprazan may offer more effective gastric acid inhibition. While not included in the latest clinical practice update, vonoprazan is thought to be superior to lansoprazole for those with LA Grade C/D esophagitis for both symptom relief and healing at 2 weeks.10

Adjunctive Therapies

Alginates can function as a physical barrier to even neutral reflux and may be helpful for patients with postprandial or nighttime symptoms as well as those with hiatal hernia.3 H2RAs can also help mitigate nighttime symptoms.3 Baclofen is a gamma-aminobutyric acid–B agonist which inhibits transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TLESR) and may be effective for patients with belching.3 Prokinetics may be helpful for GERD with concomitant gastroparesis.3 Sucralfate is a mucosal protective agent, but there is a lack of data supporting its efficacy in GERD treatment. Consider referral to a behavioral therapist for supplemental therapies, hypnotherapy, cognitive-behavior therapy, diaphragmatic breathing, and relaxation strategies for functional heartburn or reflux-associated esophageal hypervigilance or reflux hypersensitivity.3

When to Refer to Higher Level of Care

For patients who do not wish to remain on longer-term pharmacologic therapy or would benefit from anatomic repair, clinicians should have a discussion of risks and benefits prior to consideration of referral for anti-reflux procedures.3,6,8 We advise this conversation should include review of patient health status, postsurgical side effects such as increased flatus, bloating and dysphagia as well as the potential need to still resume PPI post operation.8

Endoscopic Management

Patient Selection And Evaluation

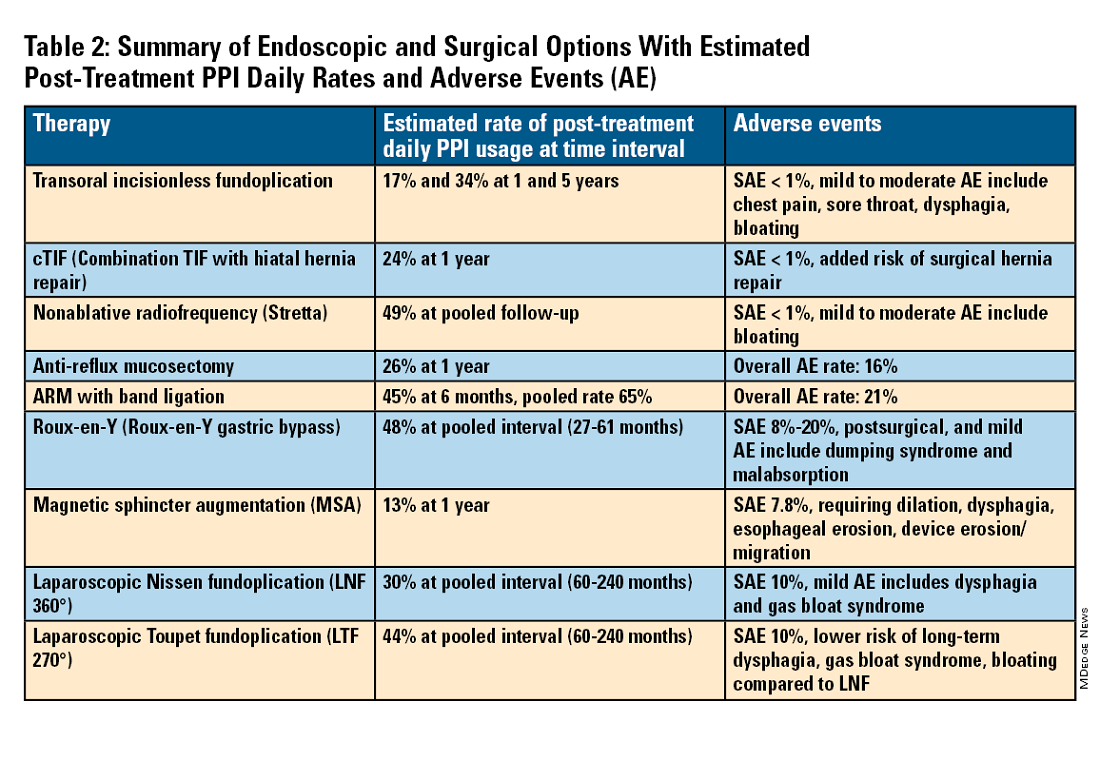

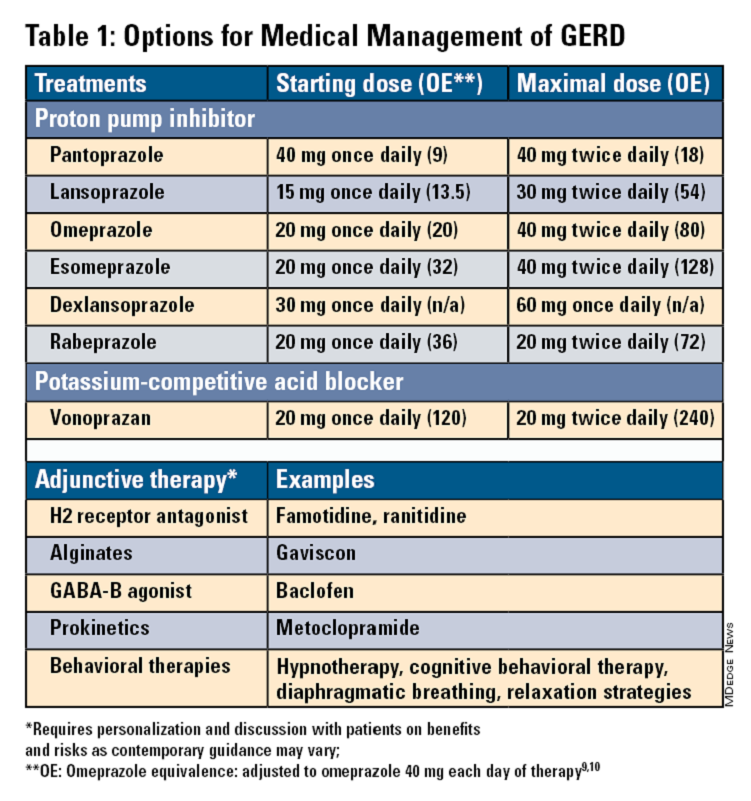

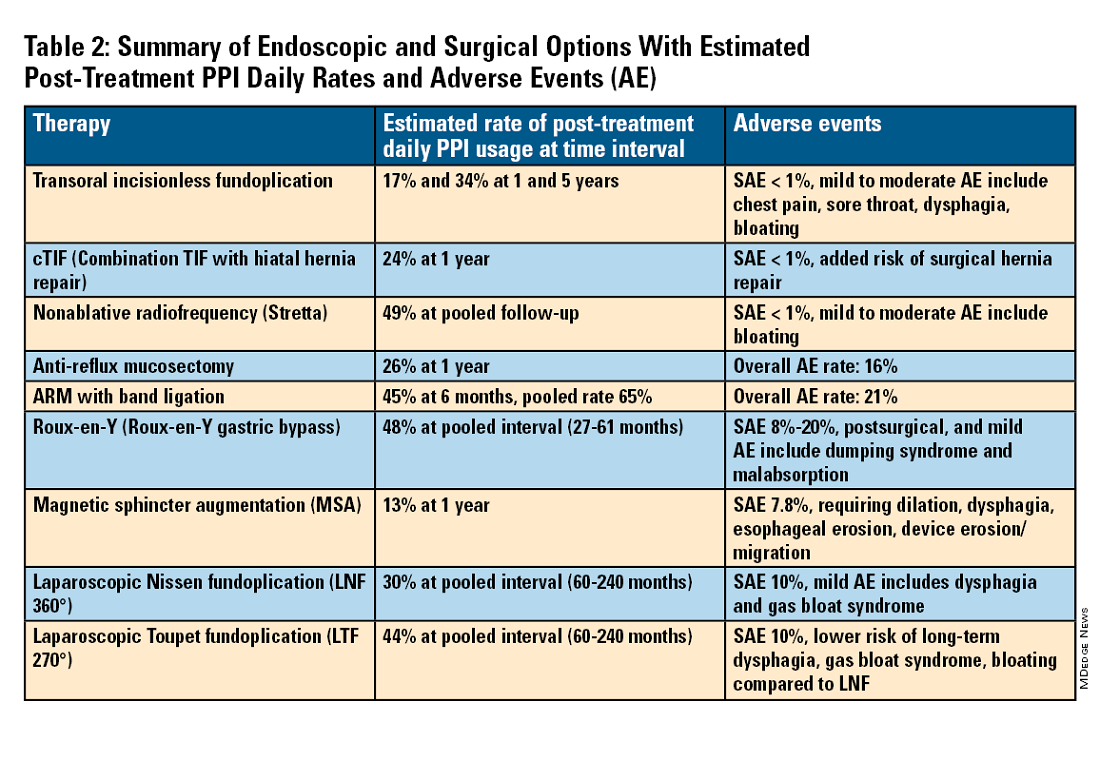

For the groups indicated for a higher level of care, we agree with AGA recommendations, multi-society guidelines, and expert review,3,7,11,12 and highlight potential options in Table 2. Step-up options should be based on patient characteristics and reviewed carefully with patients. Endoscopic therapies are less invasive than surgery and may be considered for those who do not require anatomic repair of hiatal hernia, do not want surgery, or are not suitable for surgery.

The pathophysiology of GERD is from a loss of the anti-reflux barrier of the esophageal gastric junction (EGJ) at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) leading to unintended retrograde movement of gastric contents.6 Anatomically, the LES is composed of muscles of the distal esophagus and sling fibers of the proximal stomach, the “external valve” from the diaphragmatic crura, and the “internal valve” from the gastroesophageal flap valve (GEFV). GERD occurs from mechanical failure of the LES. First, there may be disproportional dilation of the diaphragmatic crura as categorized by Hill Grade of the GEFV as seen by a retroflexed view of EGJ after 30-45 seconds of insufflation.13 Second, there may be a migration of the LES away from the diaphragmatic crura as in the case of a hiatal hernia. Provocative maneuvers may reveal a sliding hernia by gentle retraction of the endoscope while under retroflexed view.13 Third, there may be more frequent TLESR associated with GERD.12

The aim of most interventions is to restore competency of the LES by reconstruction of the GEFV via suture or staple-based approximation of tissue.11,12 Intraluminal therapy may only target the GEFV at the internal valve. Therefore, most endoscopic interventions are limited to patients with intact diaphragmatic crura (ie, small to no hiatal hernia and GEFV Hill Grade 1 to 2). Contraindications for endoscopic therapy are moderate to severe reflux (ie, LA Grade C/ D), hiatus hernia 2 cm or larger, strictures, or long-segment Barrett’s esophagus.

Utility, Safety, and Outcomes of TIF

Historically, endoscopic therapy targeting endoscopic fundoplication started with EndoLuminal gastro-gastric fundoplication (ELF, 2005) which was a proof of concept of safe manipulation and suture for gastro-gastric plication to below the Z-line. Transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) 1.0 was suggested in 2007 for clinical application by proposing a longitudinal oriented esophago-gastric plication 1 cm above the Z-line.

In 2009, TIF2.0 was proposed as a rotational 270° wrap of the cardia and fundus to a full-thickness esophago-gastric fundoplication around 2-4 cm of the distal esophagus. Like a surgical fundoplication, this reinforces sling fibers, increases the Angle of His and improves the cardiac notch. TIF 2.0 is indicated for those with small (< 2 cm) or no hiatal hernia and a GEFV Hill Grade 1 or 2. The present iteration of TIF2.0 uses EsophyX-Z (EndoGastric Solutions; Redmond, Washington) which features dual fastener deployment and a simplified firing mechanism. Plication is secured via nonresorbable polypropylene T-fasteners with strength equivalence of 3-0 sutures.

Compared with the original, TIF2.0 represents a decrease of severe adverse events from 2%-2.5% to 0.4%-1%.11,14 Based on longitudinal TEMPO data, patient satisfaction ranges between 70% and 90% and rates of patients reverting to daily PPI use are 17% and 34% at 1 and 5 years. A 5% reintervention rate was noted to be comparable with surgical reoperation for fundoplication.15 One retrospective evaluation of patients with failed TIF followed by successful cTIF noted that in all failures there was a documented underestimation of a much larger crura defect at time of index procedure.16 Chest pain is common post procedure and patients and collaborating providers should be counseled on the expected course. In our practice, we admit patients for at least 1 postprocedure day and consider scheduling symptom control medications for those with significant pain.

TIF2.0 for Special Populations

Indications for TIF2.0 continue to evolve. In 2017, concomitant TIF2.0 with hiatal hernia repair (cTIF or HH-TIF) for hernia > 2 cm was accepted for expanded use. In one study, cTIF has been shown to have similar outcomes for postprocedural PPI use, dysphagia, wrap disruption, and hiatal hernia recurrence, compared with hiatal hernia repair paired with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with possibly shorter postadmission stay, serious adverse events, and bloating.17 A cTIF may be performed in a single general anesthetic session typically with a surgical hiatal hernia repair followed by TIF2.0.

Other Endoscopic Procedures

Several other endoscopic interventions have been proposed for GERD management. The following procedures are under continuous study and should be considered only by those with expertise.

Stretta

The Stretta device (Restech; Houston, Texas) was approved in 2000 for use of a radiofrequency (RF) generator and catheter applied to the squamocolumnar junction under irrigation. Ideal candidates for this nonablative procedure may include patients with confirmed GERD, low-grade EE, without Barrett’s esophagus, small hiatal hernia, and a competent LES with pressure > 5 mmHg. Meta-analysis has yielded conflicting results in terms of its efficacy, compared with TIF2.0, and recent multi-society guidance suggests fundoplication over Stretta.7

ARM, MASE, and RAP

Anti-reflux mucosectomy (ARM) has been proposed based on the observation that patients undergoing mucosectomy for neoplasms in the cardia had improvement of reflux symptoms.11,12 Systematic review has suggested a clinical response of 80% of either PPI discontinuation or reduction, but 17% of adverse events include development of strictures. Iterations of ARM continue to be studied including ARM with band ligation (L-ARM) and endoscopic submucosal dissection for GERD (ESD-G).12

Experts have proposed incorporating endoscopic suturing of the EGJ to modulate the LES. Mucosal ablation and suturing of the EG junction (MASE) has been proposed by first priming tissue via argon plasma coagulation (APC) prior to endoscopic overstitch of two to three interrupted sutures below the EGJ to narrow and elongate the EGJ. The resection and plication (RAP) procedure performs a mucosal resection prior to full-thickness plication of the LES and cardia.11,12 Expert opinion has suggested that RAP may be used in patients with altered anatomy whereas MASE may be used when resection is not possible (eg, prior scarring, resection or ablation).12

Surgical Management

We agree with a recent multi-society guideline recommending that an interdisciplinary consultation with surgery for indicated patients with refractory GERD and underlying hiatal hernia, or who do not want lifelong medical therapy.

Fundoplication creates a surgical wrap to reinforce the LES and may be performed laparoscopically. Contraindications include body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2 and significantly impaired dysmotility. Fundoplication of 180°, 270°, and 360° may achieve comparable outcomes, but a laparoscopic toupet fundoplication (LTF 270°) may have fewer postsurgical issues of dysphagia and bloating. Advantages for both anterior and posterior partial fundoplications have been demonstrated by network meta-analysis. Therefore, a multi-society guideline for GERD suggests partial over complete fundoplication.7 Compared with posterior techniques, anterior fundoplication (Watson fundoplication) led to more recurrent reflux symptoms but less dysphagia and other side effects.19

Magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) is a surgical option that strengthens the LES with magnets to improve sphincter competence. In addition to listed contraindications of fundoplication, patients with an allergy to nickel and/or titanium are also contraindicated to receive MSA.7 MSA has been suggested to be equivalent to LNF although there may be less gas bloat and greater ability to belch on follow up.20

Surgical Options for Special Populations

Patients with medically refractory GERD and a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 may benefit from either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or fundoplication, however sleeve gastrectomy is not advised.7 In patients with BMI > 50 kg/m2, RYGB may provide an optimal choice. We agree with consultation with a bariatric surgeon when reviewing these situations.

Conclusion

Patients with GERD are commonly encountered worldwide. Empiric PPI are effective mainstays for medical treatment of GERD. Novel PCABs (e.g., vonoprazan) may present new options for GERD with LA Grade C/D esophagitis EE and merit more study. In refractory cases or for patients who do not want long term medical therapy, step-up therapy may be considered via endoscopic or surgical interventions. Patient anatomy and comorbidities should be considered by the clinician to inform treatment options. Surgery may have the most durable outcomes for those requiring step-up therapy. Improvements in technique, devices and patient selection have allowed TIF2.0 to grow as a viable offering with excellent 5-year outcomes for indicated patients.

Dr. Chang, Dr. Tintara, and Dr. Phan are based in the Division of Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Richter JE andRubenstein JH. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.045.

2. El-Serag HB et al. Gut. 2014 Jun. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269.

3. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 May. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.01.025.

4. Vakil N et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Aug. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x.

5. Numans ME et al. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Apr. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00011.

6. Kahrilas PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2008 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.045.

7. Slater BJ et al. Surg Endosc. 2023 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09817-3.

8. Gyawali CP et al. Gut. 2018 Jul. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314722.

9. Graham DY and Tansel A. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.033.

10. Graham DY and Dore MP. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.018.

11. Haseeb M and Thompson CC. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000968.

12. Kolb JM and Chang KJ. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2023 Jul. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000944.

13. Nguyen NT et al. Foregut. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1177/26345161221126961.

14. Mazzoleni G et al. Endosc Int Open. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1055/a-1322-2209.

15. Trad KS et al. Surg Innov. 2018 Apr. doi: 10.1177/1553350618755214.

16. Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(21)02953-X.

17. Jaruvongvanich VK et al. Endosc Int Open. 2023 Jan. doi: 10.1055/a-1972-9190.

18. Lee Y et al. Surg Endosc. 2023 Jul. doi: 10.1007/s00464-023-10151-5.

19. Andreou A et al. Surg Endosc. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-07208-9.

20. Guidozzi N et al. Dis Esophagus. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz031.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a frequently encountered condition, and rising annually.1 A recent meta-analysis suggests nearly 14% (1.03 billion) of the population are affected worldwide. Differences may range by region from 12% in Latin America to 20% in North America, and by country from 4% in China to 23% in Turkey.1 In the United States, 21% of the population are afflicted with weekly GERD symptoms.2 Novel medical therapies and endoscopic options provide clinicians with opportunities to help patients with GERD.3

Diagnosis

Definition

GERD was originally defined by the Montreal consensus as a condition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications.4 Heartburn and regurgitation are common symptoms of GERD, with a sensitivity of 30%-76% and specificity of 62%-96% for erosive esophagitis (EE), which occurs when the reflux of stomach content causes esophageal mucosal breaks.5 The presence of characteristic mucosal injury observed during an upper endoscopy or abnormal esophageal acid exposure on ambulatory reflux monitoring are objective evidence of GERD. A trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) may function as a diagnostic test for patients exhibiting the typical symptoms of GERD without any alarm symptoms.3,6

Endoscopic Evaluation and Confirmation

The 2022 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) clinical practice update recommends diagnostic endoscopy, after PPIs are stopped for 2-4 weeks, in patients whose GERD symptoms do not respond adequately to an empiric trial of a PPI.3 Those with GERD and alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, bleeding, and vomiting should undergo endoscopy as soon as possible. Endoscopic findings of EE (Los Angeles Grade B or more severe) and long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (> 3-cm segment with intestinal metaplasia on biopsy) are diagnostic of GERD.3

Reflux Monitoring

With ambulatory reflux monitoring (pH or impedance-pH), esophageal acid exposure (or neutral refluxate in impedance testing) can be measured to confirm GERD diagnosis and to correlate symptoms with reflux episodes. Patients with atypical GERD symptoms or patients with a confirmed diagnosis of GERD whose symptoms have not improved sufficiently with twice-daily PPI therapy should have esophageal impedance-pH monitoring while on PPIs.6,7

Esophageal Manometry

High-resolution esophageal manometry can be used to assess motility abnormalities associated with GERD.

Although no manometric abnormality is unique to GERD, weak lower esophageal sphincter (LES) resting pressure and ineffective esophageal motility frequently coexist with severe GERD.6

Manometry is particularly useful in patients considering surgical or endoscopic anti-reflux procedures to evaluate for achalasia,3 an important contraindication to surgery.

Medical Management

Management of GERD requires a multidisciplinary and personalized approach based on symptom presentation, body mass index, endoscopic findings (e.g., presence of EE, Barrett’s esophagus, hiatal hernia), and physiological abnormalities (e.g., gastroparesis or ineffective motility).3

Lifestyle Modifications

Recommended lifestyle modifications include weight loss for patients with obesity, stress reduction, tobacco and alcohol cessation, elevating the head of the bed, staying upright during and after meals, avoidance of food intake < 3 hours before bedtime, and cessation of foods that potentially aggravate reflux symptoms such as coffee, chocolate, carbonated beverages, spicy foods, acidic foods, and foods with high fat content.6,8

Medications

Pharmacologic therapy for GERD includes medications that primarily aim to neutralize or reduce gastric acid -- we summarize options in Table 1.3,8

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Most guidelines suggest a trial of 4-8 weeks of once-daily enteric-coated PPI before meals in patients with typical GERD symptoms and no alarm symptoms. Escalation to double-dose PPI may be considered in the case of persistent symptoms. The relative potencies of standard-dose pantoprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole are presented in Table 1.9 When a PPI switch is needed, rabeprazole may be considered as it is a PPI that does not rely on CYP2C19 for primary metabolism.9

Acid suppression should be weaned down to the lowest effective dose or converted to H2RAs or other antacids once symptoms are sufficiently controlled unless patients have EE, Barrett’s esophagus, or peptic stricture.3 Patients with severe GERD may require long-term PPI therapy or an invasive anti-reflux procedure.

Recent studies have shown that potassium-competitive acid blockers (PCAB) like vonoprazan may offer more effective gastric acid inhibition. While not included in the latest clinical practice update, vonoprazan is thought to be superior to lansoprazole for those with LA Grade C/D esophagitis for both symptom relief and healing at 2 weeks.10

Adjunctive Therapies

Alginates can function as a physical barrier to even neutral reflux and may be helpful for patients with postprandial or nighttime symptoms as well as those with hiatal hernia.3 H2RAs can also help mitigate nighttime symptoms.3 Baclofen is a gamma-aminobutyric acid–B agonist which inhibits transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TLESR) and may be effective for patients with belching.3 Prokinetics may be helpful for GERD with concomitant gastroparesis.3 Sucralfate is a mucosal protective agent, but there is a lack of data supporting its efficacy in GERD treatment. Consider referral to a behavioral therapist for supplemental therapies, hypnotherapy, cognitive-behavior therapy, diaphragmatic breathing, and relaxation strategies for functional heartburn or reflux-associated esophageal hypervigilance or reflux hypersensitivity.3

When to Refer to Higher Level of Care

For patients who do not wish to remain on longer-term pharmacologic therapy or would benefit from anatomic repair, clinicians should have a discussion of risks and benefits prior to consideration of referral for anti-reflux procedures.3,6,8 We advise this conversation should include review of patient health status, postsurgical side effects such as increased flatus, bloating and dysphagia as well as the potential need to still resume PPI post operation.8

Endoscopic Management

Patient Selection And Evaluation

For the groups indicated for a higher level of care, we agree with AGA recommendations, multi-society guidelines, and expert review,3,7,11,12 and highlight potential options in Table 2. Step-up options should be based on patient characteristics and reviewed carefully with patients. Endoscopic therapies are less invasive than surgery and may be considered for those who do not require anatomic repair of hiatal hernia, do not want surgery, or are not suitable for surgery.

The pathophysiology of GERD is from a loss of the anti-reflux barrier of the esophageal gastric junction (EGJ) at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) leading to unintended retrograde movement of gastric contents.6 Anatomically, the LES is composed of muscles of the distal esophagus and sling fibers of the proximal stomach, the “external valve” from the diaphragmatic crura, and the “internal valve” from the gastroesophageal flap valve (GEFV). GERD occurs from mechanical failure of the LES. First, there may be disproportional dilation of the diaphragmatic crura as categorized by Hill Grade of the GEFV as seen by a retroflexed view of EGJ after 30-45 seconds of insufflation.13 Second, there may be a migration of the LES away from the diaphragmatic crura as in the case of a hiatal hernia. Provocative maneuvers may reveal a sliding hernia by gentle retraction of the endoscope while under retroflexed view.13 Third, there may be more frequent TLESR associated with GERD.12

The aim of most interventions is to restore competency of the LES by reconstruction of the GEFV via suture or staple-based approximation of tissue.11,12 Intraluminal therapy may only target the GEFV at the internal valve. Therefore, most endoscopic interventions are limited to patients with intact diaphragmatic crura (ie, small to no hiatal hernia and GEFV Hill Grade 1 to 2). Contraindications for endoscopic therapy are moderate to severe reflux (ie, LA Grade C/ D), hiatus hernia 2 cm or larger, strictures, or long-segment Barrett’s esophagus.

Utility, Safety, and Outcomes of TIF

Historically, endoscopic therapy targeting endoscopic fundoplication started with EndoLuminal gastro-gastric fundoplication (ELF, 2005) which was a proof of concept of safe manipulation and suture for gastro-gastric plication to below the Z-line. Transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) 1.0 was suggested in 2007 for clinical application by proposing a longitudinal oriented esophago-gastric plication 1 cm above the Z-line.

In 2009, TIF2.0 was proposed as a rotational 270° wrap of the cardia and fundus to a full-thickness esophago-gastric fundoplication around 2-4 cm of the distal esophagus. Like a surgical fundoplication, this reinforces sling fibers, increases the Angle of His and improves the cardiac notch. TIF 2.0 is indicated for those with small (< 2 cm) or no hiatal hernia and a GEFV Hill Grade 1 or 2. The present iteration of TIF2.0 uses EsophyX-Z (EndoGastric Solutions; Redmond, Washington) which features dual fastener deployment and a simplified firing mechanism. Plication is secured via nonresorbable polypropylene T-fasteners with strength equivalence of 3-0 sutures.

Compared with the original, TIF2.0 represents a decrease of severe adverse events from 2%-2.5% to 0.4%-1%.11,14 Based on longitudinal TEMPO data, patient satisfaction ranges between 70% and 90% and rates of patients reverting to daily PPI use are 17% and 34% at 1 and 5 years. A 5% reintervention rate was noted to be comparable with surgical reoperation for fundoplication.15 One retrospective evaluation of patients with failed TIF followed by successful cTIF noted that in all failures there was a documented underestimation of a much larger crura defect at time of index procedure.16 Chest pain is common post procedure and patients and collaborating providers should be counseled on the expected course. In our practice, we admit patients for at least 1 postprocedure day and consider scheduling symptom control medications for those with significant pain.

TIF2.0 for Special Populations

Indications for TIF2.0 continue to evolve. In 2017, concomitant TIF2.0 with hiatal hernia repair (cTIF or HH-TIF) for hernia > 2 cm was accepted for expanded use. In one study, cTIF has been shown to have similar outcomes for postprocedural PPI use, dysphagia, wrap disruption, and hiatal hernia recurrence, compared with hiatal hernia repair paired with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with possibly shorter postadmission stay, serious adverse events, and bloating.17 A cTIF may be performed in a single general anesthetic session typically with a surgical hiatal hernia repair followed by TIF2.0.

Other Endoscopic Procedures

Several other endoscopic interventions have been proposed for GERD management. The following procedures are under continuous study and should be considered only by those with expertise.

Stretta

The Stretta device (Restech; Houston, Texas) was approved in 2000 for use of a radiofrequency (RF) generator and catheter applied to the squamocolumnar junction under irrigation. Ideal candidates for this nonablative procedure may include patients with confirmed GERD, low-grade EE, without Barrett’s esophagus, small hiatal hernia, and a competent LES with pressure > 5 mmHg. Meta-analysis has yielded conflicting results in terms of its efficacy, compared with TIF2.0, and recent multi-society guidance suggests fundoplication over Stretta.7

ARM, MASE, and RAP

Anti-reflux mucosectomy (ARM) has been proposed based on the observation that patients undergoing mucosectomy for neoplasms in the cardia had improvement of reflux symptoms.11,12 Systematic review has suggested a clinical response of 80% of either PPI discontinuation or reduction, but 17% of adverse events include development of strictures. Iterations of ARM continue to be studied including ARM with band ligation (L-ARM) and endoscopic submucosal dissection for GERD (ESD-G).12

Experts have proposed incorporating endoscopic suturing of the EGJ to modulate the LES. Mucosal ablation and suturing of the EG junction (MASE) has been proposed by first priming tissue via argon plasma coagulation (APC) prior to endoscopic overstitch of two to three interrupted sutures below the EGJ to narrow and elongate the EGJ. The resection and plication (RAP) procedure performs a mucosal resection prior to full-thickness plication of the LES and cardia.11,12 Expert opinion has suggested that RAP may be used in patients with altered anatomy whereas MASE may be used when resection is not possible (eg, prior scarring, resection or ablation).12

Surgical Management

We agree with a recent multi-society guideline recommending that an interdisciplinary consultation with surgery for indicated patients with refractory GERD and underlying hiatal hernia, or who do not want lifelong medical therapy.