User login

Bioengineered liver models screen drugs and study liver injury

resulting in stabilized liver functions for several weeks in vitro. Studies have focused on using these models to investigate cell responses to drugs and other stimuli (for example, viruses and cell differentiation cues) to predict clinical outcomes. Gregory H. Underhill, PhD, from the department of bioengineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Salman R. Khetani, PhD, from the department of bioengineering at the University of Illinois in Chicago presented a comprehensive review of the these advances in bioengineered liver models in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.11.012).

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a leading cause of drug attrition in the United States, with some marketed drugs causing cell necrosis, hepatitis, cholestasis, fibrosis, or a mixture of injury types. Although the Food and Drug Administration requires preclinical drug testing in animal models, differences in species-specific drug metabolism pathways and human genetics may result in inadequate identification of potential for human DILI. Some bioengineered liver models for in vitro studies are based on tissue engineering using high-throughput microarrays, protein micropatterning, microfluidics, specialized plates, biomaterial scaffolds, and bioprinting.

High-throughput cell microarrays enable systematic analysis of a large number of drugs or compounds at a relatively low cost. Several culture platforms have been developed using multiple sources of liver cells, including cancerous and immortalized cell lines. These platforms show enhanced capabilities to evaluate combinatorial effects of multiple signals with independent control of biochemical and biomechanical cues. For instance, a microchip platform for transducing 3-D liver cell cultures with genes for drug metabolism enzymes featuring 532 reaction vessels (micropillars and corresponding microwells) was able to provide information about certain enzyme combinations that led to drug toxicity in cells. The high-throughput cell microarrays are, however, primarily dependent on imaging-based readouts and have a limited ability to investigate cell responses to gradients of microenvironmental signals.

Liver development, physiology, and pathophysiology are dependent on homotypic and heterotypic interactions between parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells (NPCs). Cocultures with both liver- and nonliver-derived NPC types, in vitro, can induce liver functions transiently and have proven useful for investigating host responses to sepsis, mutagenesis, xenobiotic metabolism and toxicity, response to oxidative stress, lipid metabolism, and induction of the acute-phase response. Micropatterned cocultures (MPCCs) are designed to allow the use of different NPC types without significantly altering hepatocyte homotypic interactions. Cell-cell interactions can be precisely controlled to allow for stable functions for up to 4-6 weeks, whereas more randomly distributed cocultures have limited stability. Unlike randomly distributed cocultures, MPCCs can be infected with HBV, HCV, and malaria. Potential limitations of MPCCs include the requirement for specialized equipment and devices for patterning collagen for hepatocyte attachment.

Randomly distributed spheroids or organoids enable 3-D establishment of homotypic cell-cell interactions surrounded by an extracellular matrix. The spheroids can be further cocultured with NPCs that facilitate heterotypic cell-cell interactions and allow the evaluation of outcomes resulting from drugs and other stimuli. Hepatic spheroids maintain major liver functions for several weeks and have proven to be compatible with multiple applications within the drug development pipeline.

These spheroids showed greater sensitivity in identifying known hepatotoxic drugs than did short-term primary human hepatocyte (PHH) monolayers. PHHs secreted liver proteins, such as albumin, transferrin, and fibrinogen, and showed cytochrome-P450 activities for 77-90 days when cultured on a nylon scaffold containing a mixture of liver NPCs and PHHs.

Nanopillar plates can be used to create induced pluripotent stem cell–derived human hepatocyte-like cell (iHep) spheroids; although these spheroids showed some potential for initial drug toxicity screening, they had lower overall sensitivity than conventional PHH monolayers, which suggests that further maturation of iHeps is likely required.

Potential limitations of randomly distributed spheroids include necrosis of cells in the center of larger spheroids and the requirement for expensive confocal microscopy for high-content imaging of entire spheroid cultures. To overcome the limitation of disorganized cell type interactions over time within the randomly distributed spheroids/organoids, bioprinted human liver organoids are designed to allow precise control of cell placement.

Yet another bioengineered liver model is based on perfusion systems or bioreactors that enable dynamic fluid flow for nutrient and waste exchange. These so called liver-on-a-chip devices contain hepatocyte aggregates adhered to collagen-coated microchannel walls; these are then perfused at optimal flow rates both to meet the oxygen demands of the hepatocytes and deliver low shear stress to the cells that’s similar to what would be the case in vivo. Layered architectures can be created with single-chamber or multichamber, microfluidic device designs that can sustain cell functionality for 2-4 weeks.

Some of the limitations of perfusion systems include the potential binding of drugs to tubing and materials used, large dead volume requiring higher quantities of novel compounds for the treatment of cell cultures, low throughput, and washing away of built-up beneficial molecules with perfusion.

The ongoing development of more sophisticated engineering tools for manipulating cells in culture will lead to continued advances in bioengineered livers that will show improving sensitivity for the prediction of clinically relevant drug and disease outcomes.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants. The author Dr. Khetani disclosed a conflict of interest with Ascendance Biotechnology, which has licensed the micropatterned coculture and related systems from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and Colorado State University, Fort Collins, for commercial distribution. Dr. Underhill disclosed no conflicts.

SOURCE: Underhill GH and Khetani SR. Cell Molec Gastro Hepatol. 2017. doi: org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.11.012.

Thirty to 50 new drugs are approved in the United States annually, which costs approximately $2.5 billion/drug in drug development costs. Nine out of 10 drugs never make it to market, and of those that do, adverse events affect their longevity. Hepatotoxicity is the most frequent adverse drug reaction, and drug-induced liver injury, which can lead to acute liver failure, occurs in a subset of affected patients. Understanding a drug’s risk of hepatotoxicity before patients start using it can not only save lives but also conceivably reduce the costs incurred by pharmaceutical companies, which are passed on to consumers.

However, just as we have seen with the limitations of the in vitro systems, bioartificial livers are unlikely to be successful unless they integrate the liver’s complex functions of protein synthesis, immune surveillance, energy homeostasis, and nutrient sensing. The future is bright, though, as biomedical scientists and bioengineers continue to push the envelope by advancing both in vitro and bioartificial technologies.

Rotonya Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She receives research support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

Thirty to 50 new drugs are approved in the United States annually, which costs approximately $2.5 billion/drug in drug development costs. Nine out of 10 drugs never make it to market, and of those that do, adverse events affect their longevity. Hepatotoxicity is the most frequent adverse drug reaction, and drug-induced liver injury, which can lead to acute liver failure, occurs in a subset of affected patients. Understanding a drug’s risk of hepatotoxicity before patients start using it can not only save lives but also conceivably reduce the costs incurred by pharmaceutical companies, which are passed on to consumers.

However, just as we have seen with the limitations of the in vitro systems, bioartificial livers are unlikely to be successful unless they integrate the liver’s complex functions of protein synthesis, immune surveillance, energy homeostasis, and nutrient sensing. The future is bright, though, as biomedical scientists and bioengineers continue to push the envelope by advancing both in vitro and bioartificial technologies.

Rotonya Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She receives research support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

Thirty to 50 new drugs are approved in the United States annually, which costs approximately $2.5 billion/drug in drug development costs. Nine out of 10 drugs never make it to market, and of those that do, adverse events affect their longevity. Hepatotoxicity is the most frequent adverse drug reaction, and drug-induced liver injury, which can lead to acute liver failure, occurs in a subset of affected patients. Understanding a drug’s risk of hepatotoxicity before patients start using it can not only save lives but also conceivably reduce the costs incurred by pharmaceutical companies, which are passed on to consumers.

However, just as we have seen with the limitations of the in vitro systems, bioartificial livers are unlikely to be successful unless they integrate the liver’s complex functions of protein synthesis, immune surveillance, energy homeostasis, and nutrient sensing. The future is bright, though, as biomedical scientists and bioengineers continue to push the envelope by advancing both in vitro and bioartificial technologies.

Rotonya Carr, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She receives research support from Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

resulting in stabilized liver functions for several weeks in vitro. Studies have focused on using these models to investigate cell responses to drugs and other stimuli (for example, viruses and cell differentiation cues) to predict clinical outcomes. Gregory H. Underhill, PhD, from the department of bioengineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Salman R. Khetani, PhD, from the department of bioengineering at the University of Illinois in Chicago presented a comprehensive review of the these advances in bioengineered liver models in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.11.012).

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a leading cause of drug attrition in the United States, with some marketed drugs causing cell necrosis, hepatitis, cholestasis, fibrosis, or a mixture of injury types. Although the Food and Drug Administration requires preclinical drug testing in animal models, differences in species-specific drug metabolism pathways and human genetics may result in inadequate identification of potential for human DILI. Some bioengineered liver models for in vitro studies are based on tissue engineering using high-throughput microarrays, protein micropatterning, microfluidics, specialized plates, biomaterial scaffolds, and bioprinting.

High-throughput cell microarrays enable systematic analysis of a large number of drugs or compounds at a relatively low cost. Several culture platforms have been developed using multiple sources of liver cells, including cancerous and immortalized cell lines. These platforms show enhanced capabilities to evaluate combinatorial effects of multiple signals with independent control of biochemical and biomechanical cues. For instance, a microchip platform for transducing 3-D liver cell cultures with genes for drug metabolism enzymes featuring 532 reaction vessels (micropillars and corresponding microwells) was able to provide information about certain enzyme combinations that led to drug toxicity in cells. The high-throughput cell microarrays are, however, primarily dependent on imaging-based readouts and have a limited ability to investigate cell responses to gradients of microenvironmental signals.

Liver development, physiology, and pathophysiology are dependent on homotypic and heterotypic interactions between parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells (NPCs). Cocultures with both liver- and nonliver-derived NPC types, in vitro, can induce liver functions transiently and have proven useful for investigating host responses to sepsis, mutagenesis, xenobiotic metabolism and toxicity, response to oxidative stress, lipid metabolism, and induction of the acute-phase response. Micropatterned cocultures (MPCCs) are designed to allow the use of different NPC types without significantly altering hepatocyte homotypic interactions. Cell-cell interactions can be precisely controlled to allow for stable functions for up to 4-6 weeks, whereas more randomly distributed cocultures have limited stability. Unlike randomly distributed cocultures, MPCCs can be infected with HBV, HCV, and malaria. Potential limitations of MPCCs include the requirement for specialized equipment and devices for patterning collagen for hepatocyte attachment.

Randomly distributed spheroids or organoids enable 3-D establishment of homotypic cell-cell interactions surrounded by an extracellular matrix. The spheroids can be further cocultured with NPCs that facilitate heterotypic cell-cell interactions and allow the evaluation of outcomes resulting from drugs and other stimuli. Hepatic spheroids maintain major liver functions for several weeks and have proven to be compatible with multiple applications within the drug development pipeline.

These spheroids showed greater sensitivity in identifying known hepatotoxic drugs than did short-term primary human hepatocyte (PHH) monolayers. PHHs secreted liver proteins, such as albumin, transferrin, and fibrinogen, and showed cytochrome-P450 activities for 77-90 days when cultured on a nylon scaffold containing a mixture of liver NPCs and PHHs.

Nanopillar plates can be used to create induced pluripotent stem cell–derived human hepatocyte-like cell (iHep) spheroids; although these spheroids showed some potential for initial drug toxicity screening, they had lower overall sensitivity than conventional PHH monolayers, which suggests that further maturation of iHeps is likely required.

Potential limitations of randomly distributed spheroids include necrosis of cells in the center of larger spheroids and the requirement for expensive confocal microscopy for high-content imaging of entire spheroid cultures. To overcome the limitation of disorganized cell type interactions over time within the randomly distributed spheroids/organoids, bioprinted human liver organoids are designed to allow precise control of cell placement.

Yet another bioengineered liver model is based on perfusion systems or bioreactors that enable dynamic fluid flow for nutrient and waste exchange. These so called liver-on-a-chip devices contain hepatocyte aggregates adhered to collagen-coated microchannel walls; these are then perfused at optimal flow rates both to meet the oxygen demands of the hepatocytes and deliver low shear stress to the cells that’s similar to what would be the case in vivo. Layered architectures can be created with single-chamber or multichamber, microfluidic device designs that can sustain cell functionality for 2-4 weeks.

Some of the limitations of perfusion systems include the potential binding of drugs to tubing and materials used, large dead volume requiring higher quantities of novel compounds for the treatment of cell cultures, low throughput, and washing away of built-up beneficial molecules with perfusion.

The ongoing development of more sophisticated engineering tools for manipulating cells in culture will lead to continued advances in bioengineered livers that will show improving sensitivity for the prediction of clinically relevant drug and disease outcomes.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants. The author Dr. Khetani disclosed a conflict of interest with Ascendance Biotechnology, which has licensed the micropatterned coculture and related systems from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and Colorado State University, Fort Collins, for commercial distribution. Dr. Underhill disclosed no conflicts.

SOURCE: Underhill GH and Khetani SR. Cell Molec Gastro Hepatol. 2017. doi: org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.11.012.

resulting in stabilized liver functions for several weeks in vitro. Studies have focused on using these models to investigate cell responses to drugs and other stimuli (for example, viruses and cell differentiation cues) to predict clinical outcomes. Gregory H. Underhill, PhD, from the department of bioengineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Salman R. Khetani, PhD, from the department of bioengineering at the University of Illinois in Chicago presented a comprehensive review of the these advances in bioengineered liver models in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.11.012).

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a leading cause of drug attrition in the United States, with some marketed drugs causing cell necrosis, hepatitis, cholestasis, fibrosis, or a mixture of injury types. Although the Food and Drug Administration requires preclinical drug testing in animal models, differences in species-specific drug metabolism pathways and human genetics may result in inadequate identification of potential for human DILI. Some bioengineered liver models for in vitro studies are based on tissue engineering using high-throughput microarrays, protein micropatterning, microfluidics, specialized plates, biomaterial scaffolds, and bioprinting.

High-throughput cell microarrays enable systematic analysis of a large number of drugs or compounds at a relatively low cost. Several culture platforms have been developed using multiple sources of liver cells, including cancerous and immortalized cell lines. These platforms show enhanced capabilities to evaluate combinatorial effects of multiple signals with independent control of biochemical and biomechanical cues. For instance, a microchip platform for transducing 3-D liver cell cultures with genes for drug metabolism enzymes featuring 532 reaction vessels (micropillars and corresponding microwells) was able to provide information about certain enzyme combinations that led to drug toxicity in cells. The high-throughput cell microarrays are, however, primarily dependent on imaging-based readouts and have a limited ability to investigate cell responses to gradients of microenvironmental signals.

Liver development, physiology, and pathophysiology are dependent on homotypic and heterotypic interactions between parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells (NPCs). Cocultures with both liver- and nonliver-derived NPC types, in vitro, can induce liver functions transiently and have proven useful for investigating host responses to sepsis, mutagenesis, xenobiotic metabolism and toxicity, response to oxidative stress, lipid metabolism, and induction of the acute-phase response. Micropatterned cocultures (MPCCs) are designed to allow the use of different NPC types without significantly altering hepatocyte homotypic interactions. Cell-cell interactions can be precisely controlled to allow for stable functions for up to 4-6 weeks, whereas more randomly distributed cocultures have limited stability. Unlike randomly distributed cocultures, MPCCs can be infected with HBV, HCV, and malaria. Potential limitations of MPCCs include the requirement for specialized equipment and devices for patterning collagen for hepatocyte attachment.

Randomly distributed spheroids or organoids enable 3-D establishment of homotypic cell-cell interactions surrounded by an extracellular matrix. The spheroids can be further cocultured with NPCs that facilitate heterotypic cell-cell interactions and allow the evaluation of outcomes resulting from drugs and other stimuli. Hepatic spheroids maintain major liver functions for several weeks and have proven to be compatible with multiple applications within the drug development pipeline.

These spheroids showed greater sensitivity in identifying known hepatotoxic drugs than did short-term primary human hepatocyte (PHH) monolayers. PHHs secreted liver proteins, such as albumin, transferrin, and fibrinogen, and showed cytochrome-P450 activities for 77-90 days when cultured on a nylon scaffold containing a mixture of liver NPCs and PHHs.

Nanopillar plates can be used to create induced pluripotent stem cell–derived human hepatocyte-like cell (iHep) spheroids; although these spheroids showed some potential for initial drug toxicity screening, they had lower overall sensitivity than conventional PHH monolayers, which suggests that further maturation of iHeps is likely required.

Potential limitations of randomly distributed spheroids include necrosis of cells in the center of larger spheroids and the requirement for expensive confocal microscopy for high-content imaging of entire spheroid cultures. To overcome the limitation of disorganized cell type interactions over time within the randomly distributed spheroids/organoids, bioprinted human liver organoids are designed to allow precise control of cell placement.

Yet another bioengineered liver model is based on perfusion systems or bioreactors that enable dynamic fluid flow for nutrient and waste exchange. These so called liver-on-a-chip devices contain hepatocyte aggregates adhered to collagen-coated microchannel walls; these are then perfused at optimal flow rates both to meet the oxygen demands of the hepatocytes and deliver low shear stress to the cells that’s similar to what would be the case in vivo. Layered architectures can be created with single-chamber or multichamber, microfluidic device designs that can sustain cell functionality for 2-4 weeks.

Some of the limitations of perfusion systems include the potential binding of drugs to tubing and materials used, large dead volume requiring higher quantities of novel compounds for the treatment of cell cultures, low throughput, and washing away of built-up beneficial molecules with perfusion.

The ongoing development of more sophisticated engineering tools for manipulating cells in culture will lead to continued advances in bioengineered livers that will show improving sensitivity for the prediction of clinically relevant drug and disease outcomes.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants. The author Dr. Khetani disclosed a conflict of interest with Ascendance Biotechnology, which has licensed the micropatterned coculture and related systems from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and Colorado State University, Fort Collins, for commercial distribution. Dr. Underhill disclosed no conflicts.

SOURCE: Underhill GH and Khetani SR. Cell Molec Gastro Hepatol. 2017. doi: org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.11.012.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Possible increased breast cancer risk found in women with schizophrenia

A meta-analysis has found an increased risk of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia, but its authors noted significant diversity of results across the included studies.

In the meta-analysis, Chuanjun Zhuo, MD, PhD, and Patrick Todd Triplett, MD, presented the results of 12 cohort studies involving 125,760 women that showed the risk of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia, compared with the general population.

They found that women with schizophrenia had a 31% higher standardized incidence ratio of breast cancer (95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.50; P less than .001). However, significant heterogeneity was found between studies, with the prediction interval ranging from 0.81 to 2.10. The report was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

“Accordingly, it is possible that a future study will show a decreased breast cancer risk in women with schizophrenia compared with the general population,” said Dr. Zhuo of Tianjin Medical University, China, and Dr. Triplett, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

As it turns out, one of the subgroup analyses showed that the association between schizophrenia and breast cancer was significant only in studies that excluded women who were diagnosed with breast cancer before they were diagnosed with schizophrenia (standardized incidence ratio, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.20-1.51; P less than .001).

The same was seen in studies where there were more than 100 cases of breast cancer (SIR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.18-1.46; P less than .001), while the association was not significant in studies with fewer than 100 cases.

The authors said their findings contradict a hypothesis that schizophrenia might be protective against cancer.

“These results, together with our recent meta-analysis results showing no association with lung cancer risk but a reduced hepatic cancer risk in schizophrenia, indicated that the association between schizophrenia and cancer risk may be complicated and depend on the cancer site,” wrote Dr. Zhuo and Dr. Triplett.

In terms of possible mechanisms underlying the increased risk of breast cancer seen in this study, the authors suggested that people with schizophrenia could experience other clinical conditions such as obesity that might increase their risk of breast cancer.

“As breast cancer may be a hormone-dependent cancer, a significant positive association between plasma prolactin levels and the risk of breast cancer has been observed; in addition, increased prolactin levels have been documented in women with schizophrenia, particularly for those receiving certain antipsychotics,” they wrote.

While the incidence of cancer in people with schizophrenia might not necessarily differ from that of the general population, the authors said studies have found that people with schizophrenia have higher cancer mortality. Because “breast cancer prevention and treatment options are less optimal in women with schizophrenia, our results highlight that women with schizophrenia deserve focused care for breast cancer screening and treatment,” they wrote.

The Tianjin Health Bureau Foundation and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin, China, supported the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Zhuo C et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4748.

A meta-analysis has found an increased risk of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia, but its authors noted significant diversity of results across the included studies.

In the meta-analysis, Chuanjun Zhuo, MD, PhD, and Patrick Todd Triplett, MD, presented the results of 12 cohort studies involving 125,760 women that showed the risk of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia, compared with the general population.

They found that women with schizophrenia had a 31% higher standardized incidence ratio of breast cancer (95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.50; P less than .001). However, significant heterogeneity was found between studies, with the prediction interval ranging from 0.81 to 2.10. The report was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

“Accordingly, it is possible that a future study will show a decreased breast cancer risk in women with schizophrenia compared with the general population,” said Dr. Zhuo of Tianjin Medical University, China, and Dr. Triplett, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

As it turns out, one of the subgroup analyses showed that the association between schizophrenia and breast cancer was significant only in studies that excluded women who were diagnosed with breast cancer before they were diagnosed with schizophrenia (standardized incidence ratio, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.20-1.51; P less than .001).

The same was seen in studies where there were more than 100 cases of breast cancer (SIR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.18-1.46; P less than .001), while the association was not significant in studies with fewer than 100 cases.

The authors said their findings contradict a hypothesis that schizophrenia might be protective against cancer.

“These results, together with our recent meta-analysis results showing no association with lung cancer risk but a reduced hepatic cancer risk in schizophrenia, indicated that the association between schizophrenia and cancer risk may be complicated and depend on the cancer site,” wrote Dr. Zhuo and Dr. Triplett.

In terms of possible mechanisms underlying the increased risk of breast cancer seen in this study, the authors suggested that people with schizophrenia could experience other clinical conditions such as obesity that might increase their risk of breast cancer.

“As breast cancer may be a hormone-dependent cancer, a significant positive association between plasma prolactin levels and the risk of breast cancer has been observed; in addition, increased prolactin levels have been documented in women with schizophrenia, particularly for those receiving certain antipsychotics,” they wrote.

While the incidence of cancer in people with schizophrenia might not necessarily differ from that of the general population, the authors said studies have found that people with schizophrenia have higher cancer mortality. Because “breast cancer prevention and treatment options are less optimal in women with schizophrenia, our results highlight that women with schizophrenia deserve focused care for breast cancer screening and treatment,” they wrote.

The Tianjin Health Bureau Foundation and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin, China, supported the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Zhuo C et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4748.

A meta-analysis has found an increased risk of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia, but its authors noted significant diversity of results across the included studies.

In the meta-analysis, Chuanjun Zhuo, MD, PhD, and Patrick Todd Triplett, MD, presented the results of 12 cohort studies involving 125,760 women that showed the risk of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia, compared with the general population.

They found that women with schizophrenia had a 31% higher standardized incidence ratio of breast cancer (95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.50; P less than .001). However, significant heterogeneity was found between studies, with the prediction interval ranging from 0.81 to 2.10. The report was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

“Accordingly, it is possible that a future study will show a decreased breast cancer risk in women with schizophrenia compared with the general population,” said Dr. Zhuo of Tianjin Medical University, China, and Dr. Triplett, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

As it turns out, one of the subgroup analyses showed that the association between schizophrenia and breast cancer was significant only in studies that excluded women who were diagnosed with breast cancer before they were diagnosed with schizophrenia (standardized incidence ratio, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.20-1.51; P less than .001).

The same was seen in studies where there were more than 100 cases of breast cancer (SIR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.18-1.46; P less than .001), while the association was not significant in studies with fewer than 100 cases.

The authors said their findings contradict a hypothesis that schizophrenia might be protective against cancer.

“These results, together with our recent meta-analysis results showing no association with lung cancer risk but a reduced hepatic cancer risk in schizophrenia, indicated that the association between schizophrenia and cancer risk may be complicated and depend on the cancer site,” wrote Dr. Zhuo and Dr. Triplett.

In terms of possible mechanisms underlying the increased risk of breast cancer seen in this study, the authors suggested that people with schizophrenia could experience other clinical conditions such as obesity that might increase their risk of breast cancer.

“As breast cancer may be a hormone-dependent cancer, a significant positive association between plasma prolactin levels and the risk of breast cancer has been observed; in addition, increased prolactin levels have been documented in women with schizophrenia, particularly for those receiving certain antipsychotics,” they wrote.

While the incidence of cancer in people with schizophrenia might not necessarily differ from that of the general population, the authors said studies have found that people with schizophrenia have higher cancer mortality. Because “breast cancer prevention and treatment options are less optimal in women with schizophrenia, our results highlight that women with schizophrenia deserve focused care for breast cancer screening and treatment,” they wrote.

The Tianjin Health Bureau Foundation and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin, China, supported the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Zhuo C et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4748.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: Women diagnosed with schizophrenia should receive intensive screening and treatment for breast cancer.

Major finding: Women with schizophrenia showed a 31% higher standardized incidence ratio of breast cancer than that of the general population.

Data source: Meta-analysis of 12 cohort studies involving 125,760 women.

Disclosures: The Tianjin Health Bureau Foundation and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin, China, supported the work. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Zhuo C et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4748.

Innovation as a key to patient outcomes

For about 10 years, the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, has brought together physician innovators, entrepreneurs, and industry representatives to facilitate innovation in gastroenterology practice, and this year is no exception.

Attendees will get a “comprehensive, almost immersive experience to understand what’s hot in gastroenterology and innovation in 2018, where the gaps are, and where we need future innovators to be successful to improve patient outcomes,” said Srinadh (Sri) Komanduri, MD, the medical director of the GI laboratory and director of interventional endoscopy at Northwestern University in Chicago, as well as one of the meeting’s organizers.

The meeting is designed to aid entrepreneurs, as well as physician innovators, who have ideas how to improve the field of gastroenterology but have found it daunting to take their ideas and commercialize them, added meeting organizer V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, the director of endoscopy for the University of California, Los Angeles, Health System. Dr. Muthusamy and Dr. Komanduri serve as cochairs of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology executive committee.

“Innovation is key to evolving and thriving in any field, and we’re trying to foster that in gastroenterology,” Dr. Muthusamy said. “There are many good ideas in GI that probably never see the light of day simply because of real and perceived barriers to successful innovation. We’re trying to demystify and simplify that process.”

New this year will be a Wednesday preconference entrepreneur and innovator package session, in which innovators can meet one-on-one with experts – including intellectual property attorneys, physician innovators, venture capitalists, and payers – for personalized advice on how to move their products forward. An evening dinner reception for summit sponsors will feature a talk by Kevin Volpp, MD, PhD, founding director of the Center for Health Incentives and Behavior Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, about the psychology of purchasing and how economic decisions are made in health care.

Also new for 2018 is a Thursday afternoon session on the evolving role of digital health in GI diseases. “We’ll look at where medicine is headed in terms of artificial intelligence, patient-driven mobile applications, and everything becoming digitally balanced,” said Dr. Komanduri, who will moderate the session. “We need to understand the space and how to utilize it on a more global aspect when it comes to innovation because there is a need for further education.”

The main summit will kick off Thursday with an address by Vadim Backman, PhD, the Walter Dill Scott Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern University, about nanotechnology and how it applies to gastroenterology. “We have a lot of entrepreneurs wondering what’s the next thing,” Dr. Muthusamy said. “I think Vadim is going to open up some new horizons and get us thinking about things that we haven’t traditionally thought of.”

The morning will focus on avoiding critical mistakes in startups and on medical device development, including lessons learned about developing a product and practical approaches to getting funded. Sessions scheduled for after lunch will highlight how to achieve physician adoption, including how to obtain a CPT code and physician barriers to incorporating new technology.

Friday’s sessions are unofficially titled “the next generation of endoscopy,” Dr. Muthusamy said. The day will begin with a look at bariatric endoscopy and surgical techniques and at the challenges and unmet needs of bariatric procedures, as well as organ-sparing resection techniques. Following the Shark Tank presentations, in which small companies can present their ideas to an expert panel, and lunch, the afternoon program will feature discussions on the reprocessing of duodenoscopes and quality in endoscopy.

“Our goal is not just to have these sessions be an interesting 90 minutes but to inspire a group of people with passion and interest in these areas to guide the field over the next 5-10 years in terms of where our energies should be focused, what’s needed, and what trials should be done so we can achieve the best results the quickest to achieve adoption of novel technologies,” Dr. Muthusamy said.

Dr. Komanduri is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Cook Medical, Olympus and Medtronic. Dr. Muthusamy disclosed financial relationships with CapsoVision, Boston Scientific and Medtronic.

For about 10 years, the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, has brought together physician innovators, entrepreneurs, and industry representatives to facilitate innovation in gastroenterology practice, and this year is no exception.

Attendees will get a “comprehensive, almost immersive experience to understand what’s hot in gastroenterology and innovation in 2018, where the gaps are, and where we need future innovators to be successful to improve patient outcomes,” said Srinadh (Sri) Komanduri, MD, the medical director of the GI laboratory and director of interventional endoscopy at Northwestern University in Chicago, as well as one of the meeting’s organizers.

The meeting is designed to aid entrepreneurs, as well as physician innovators, who have ideas how to improve the field of gastroenterology but have found it daunting to take their ideas and commercialize them, added meeting organizer V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, the director of endoscopy for the University of California, Los Angeles, Health System. Dr. Muthusamy and Dr. Komanduri serve as cochairs of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology executive committee.

“Innovation is key to evolving and thriving in any field, and we’re trying to foster that in gastroenterology,” Dr. Muthusamy said. “There are many good ideas in GI that probably never see the light of day simply because of real and perceived barriers to successful innovation. We’re trying to demystify and simplify that process.”

New this year will be a Wednesday preconference entrepreneur and innovator package session, in which innovators can meet one-on-one with experts – including intellectual property attorneys, physician innovators, venture capitalists, and payers – for personalized advice on how to move their products forward. An evening dinner reception for summit sponsors will feature a talk by Kevin Volpp, MD, PhD, founding director of the Center for Health Incentives and Behavior Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, about the psychology of purchasing and how economic decisions are made in health care.

Also new for 2018 is a Thursday afternoon session on the evolving role of digital health in GI diseases. “We’ll look at where medicine is headed in terms of artificial intelligence, patient-driven mobile applications, and everything becoming digitally balanced,” said Dr. Komanduri, who will moderate the session. “We need to understand the space and how to utilize it on a more global aspect when it comes to innovation because there is a need for further education.”

The main summit will kick off Thursday with an address by Vadim Backman, PhD, the Walter Dill Scott Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern University, about nanotechnology and how it applies to gastroenterology. “We have a lot of entrepreneurs wondering what’s the next thing,” Dr. Muthusamy said. “I think Vadim is going to open up some new horizons and get us thinking about things that we haven’t traditionally thought of.”

The morning will focus on avoiding critical mistakes in startups and on medical device development, including lessons learned about developing a product and practical approaches to getting funded. Sessions scheduled for after lunch will highlight how to achieve physician adoption, including how to obtain a CPT code and physician barriers to incorporating new technology.

Friday’s sessions are unofficially titled “the next generation of endoscopy,” Dr. Muthusamy said. The day will begin with a look at bariatric endoscopy and surgical techniques and at the challenges and unmet needs of bariatric procedures, as well as organ-sparing resection techniques. Following the Shark Tank presentations, in which small companies can present their ideas to an expert panel, and lunch, the afternoon program will feature discussions on the reprocessing of duodenoscopes and quality in endoscopy.

“Our goal is not just to have these sessions be an interesting 90 minutes but to inspire a group of people with passion and interest in these areas to guide the field over the next 5-10 years in terms of where our energies should be focused, what’s needed, and what trials should be done so we can achieve the best results the quickest to achieve adoption of novel technologies,” Dr. Muthusamy said.

Dr. Komanduri is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Cook Medical, Olympus and Medtronic. Dr. Muthusamy disclosed financial relationships with CapsoVision, Boston Scientific and Medtronic.

For about 10 years, the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, has brought together physician innovators, entrepreneurs, and industry representatives to facilitate innovation in gastroenterology practice, and this year is no exception.

Attendees will get a “comprehensive, almost immersive experience to understand what’s hot in gastroenterology and innovation in 2018, where the gaps are, and where we need future innovators to be successful to improve patient outcomes,” said Srinadh (Sri) Komanduri, MD, the medical director of the GI laboratory and director of interventional endoscopy at Northwestern University in Chicago, as well as one of the meeting’s organizers.

The meeting is designed to aid entrepreneurs, as well as physician innovators, who have ideas how to improve the field of gastroenterology but have found it daunting to take their ideas and commercialize them, added meeting organizer V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, the director of endoscopy for the University of California, Los Angeles, Health System. Dr. Muthusamy and Dr. Komanduri serve as cochairs of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology executive committee.

“Innovation is key to evolving and thriving in any field, and we’re trying to foster that in gastroenterology,” Dr. Muthusamy said. “There are many good ideas in GI that probably never see the light of day simply because of real and perceived barriers to successful innovation. We’re trying to demystify and simplify that process.”

New this year will be a Wednesday preconference entrepreneur and innovator package session, in which innovators can meet one-on-one with experts – including intellectual property attorneys, physician innovators, venture capitalists, and payers – for personalized advice on how to move their products forward. An evening dinner reception for summit sponsors will feature a talk by Kevin Volpp, MD, PhD, founding director of the Center for Health Incentives and Behavior Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, about the psychology of purchasing and how economic decisions are made in health care.

Also new for 2018 is a Thursday afternoon session on the evolving role of digital health in GI diseases. “We’ll look at where medicine is headed in terms of artificial intelligence, patient-driven mobile applications, and everything becoming digitally balanced,” said Dr. Komanduri, who will moderate the session. “We need to understand the space and how to utilize it on a more global aspect when it comes to innovation because there is a need for further education.”

The main summit will kick off Thursday with an address by Vadim Backman, PhD, the Walter Dill Scott Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern University, about nanotechnology and how it applies to gastroenterology. “We have a lot of entrepreneurs wondering what’s the next thing,” Dr. Muthusamy said. “I think Vadim is going to open up some new horizons and get us thinking about things that we haven’t traditionally thought of.”

The morning will focus on avoiding critical mistakes in startups and on medical device development, including lessons learned about developing a product and practical approaches to getting funded. Sessions scheduled for after lunch will highlight how to achieve physician adoption, including how to obtain a CPT code and physician barriers to incorporating new technology.

Friday’s sessions are unofficially titled “the next generation of endoscopy,” Dr. Muthusamy said. The day will begin with a look at bariatric endoscopy and surgical techniques and at the challenges and unmet needs of bariatric procedures, as well as organ-sparing resection techniques. Following the Shark Tank presentations, in which small companies can present their ideas to an expert panel, and lunch, the afternoon program will feature discussions on the reprocessing of duodenoscopes and quality in endoscopy.

“Our goal is not just to have these sessions be an interesting 90 minutes but to inspire a group of people with passion and interest in these areas to guide the field over the next 5-10 years in terms of where our energies should be focused, what’s needed, and what trials should be done so we can achieve the best results the quickest to achieve adoption of novel technologies,” Dr. Muthusamy said.

Dr. Komanduri is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Cook Medical, Olympus and Medtronic. Dr. Muthusamy disclosed financial relationships with CapsoVision, Boston Scientific and Medtronic.

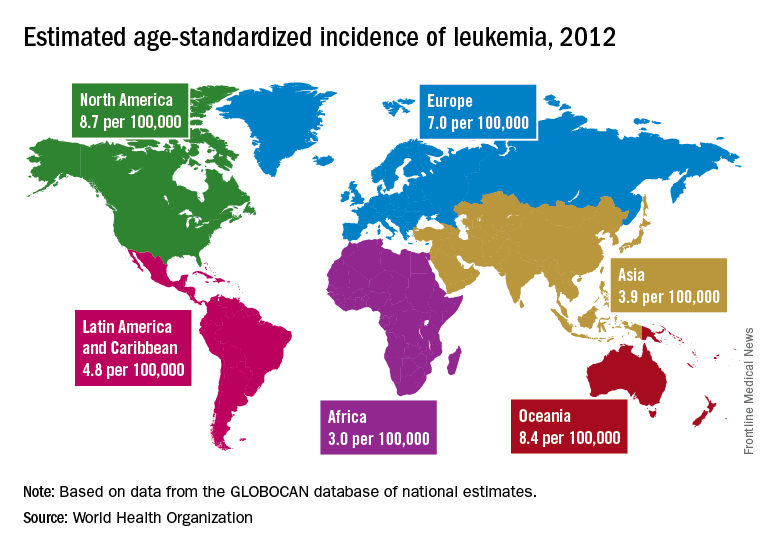

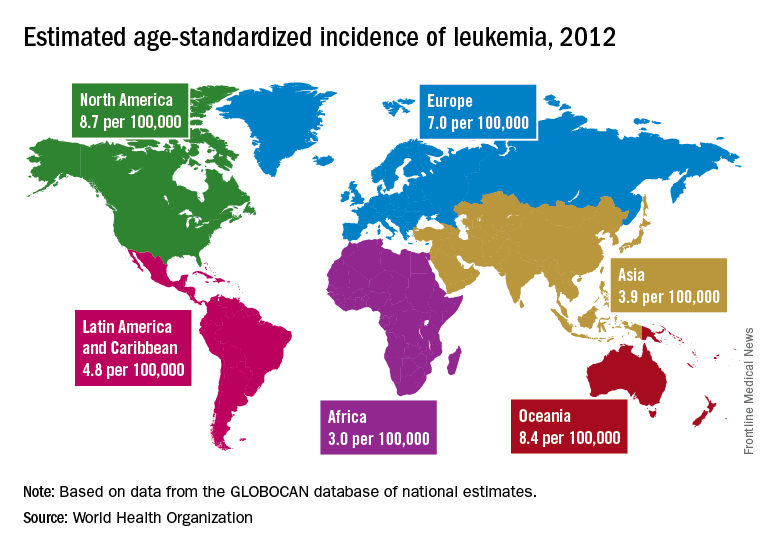

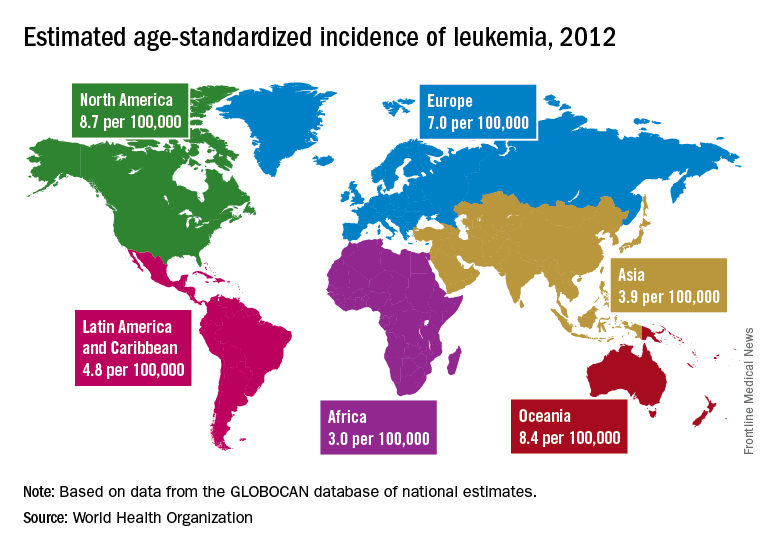

A global snapshot of leukemia incidence

, according to an analysis of World Health Organization cancer databases.

Incidence also is generally higher in males, with a global male to female ratio of 1.4. For men, the highest regional leukemia rate – estimated at 11.3 per 100,000 population for 2012 – was found in Australia and New Zealand, with northern America (the United States and Canada) next at 10.5 per 100,000. Australia/New Zealand and northern America had the highest rate for women at 7.2 per 100,000, followed by western Europe and northern Europe at 6.0 per 100,000, reported Adalberto Miranda-Filho, PhD, of the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and his associates.

The lowest regional rates for women were found in western Africa (1.2 per 100,000), middle Africa (1.8), and Micronesia/Polynesia (2.1). For men, leukemia incidence was lowest in western Africa (1.4 per 100,000), middle Africa (2.6), and south-central Asia (3.4), according to data from the WHO’s GLOBOCAN database. The report was published in The Lancet Haematology.

Estimates for leukemia subtypes in 2003-2007 – calculated for 54 countries, not regions – also showed a great deal of variation. For acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Ecuador had the highest rates for both males (2.8 per 100,000) and females (3.3), with high rates seen in Costa Rica, Columbia, and Cyprus. Rates in the United States were near the top: 2.1 for males and 1.6 for females. Rates were lowest for men in Jamaica (0.4) and Serbia (0.6) and for women in India (0.5) and Serbia and Cuba (0.6), Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

Incidence rates for acute myeloid leukemia were highest in Australia for men (2.8 per 100,000) and Austria for women (2.2), with the United States near the top for both men (2.6) and women (1.9). The lowest rates occurred in Cuba and Egypt for men (0.9 per 100,000) and Cuba for women (0.4), data from the WHO’s Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume X show.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia incidence was highest for men in Canada (4.5 per 100,000), Ireland and Lithuania (4.4), and Slovakia (4.3). The incidence was highest for women in Lithuania (2.5), Canada (2.3), and Slovakia and Denmark (2.1). Incidence in the United States was 3.5 for men and 1.8 for women. At the other end of the scale, the lowest rates for both men and women were in Japan and Malaysia (0.1), the investigators’ analysis showed.

Chronic myeloid leukemia rates were the lowest of the subtypes, and Tunisia was the lowest for men at 0.4 per 100,000 and tied for lowest with Serbia, Slovenia, and Puerto Rico for women at 0.3. Incidence was highest for men in Australia at 1.8 per 100,000 and highest for women in Uruguay at 1.1. Rates in the United States were 1.3 for men and 0.8 for women, Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

“The higher incidence of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in parts of South America, as well as of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in populations across North America and Oceania, alongside a lower incidence in Asia, might be important markers for further epidemiological study, and a means to better understand the underlying factors to support future cancer prevention strategies,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Miranda-Filho A et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e14-24.

, according to an analysis of World Health Organization cancer databases.

Incidence also is generally higher in males, with a global male to female ratio of 1.4. For men, the highest regional leukemia rate – estimated at 11.3 per 100,000 population for 2012 – was found in Australia and New Zealand, with northern America (the United States and Canada) next at 10.5 per 100,000. Australia/New Zealand and northern America had the highest rate for women at 7.2 per 100,000, followed by western Europe and northern Europe at 6.0 per 100,000, reported Adalberto Miranda-Filho, PhD, of the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and his associates.

The lowest regional rates for women were found in western Africa (1.2 per 100,000), middle Africa (1.8), and Micronesia/Polynesia (2.1). For men, leukemia incidence was lowest in western Africa (1.4 per 100,000), middle Africa (2.6), and south-central Asia (3.4), according to data from the WHO’s GLOBOCAN database. The report was published in The Lancet Haematology.

Estimates for leukemia subtypes in 2003-2007 – calculated for 54 countries, not regions – also showed a great deal of variation. For acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Ecuador had the highest rates for both males (2.8 per 100,000) and females (3.3), with high rates seen in Costa Rica, Columbia, and Cyprus. Rates in the United States were near the top: 2.1 for males and 1.6 for females. Rates were lowest for men in Jamaica (0.4) and Serbia (0.6) and for women in India (0.5) and Serbia and Cuba (0.6), Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

Incidence rates for acute myeloid leukemia were highest in Australia for men (2.8 per 100,000) and Austria for women (2.2), with the United States near the top for both men (2.6) and women (1.9). The lowest rates occurred in Cuba and Egypt for men (0.9 per 100,000) and Cuba for women (0.4), data from the WHO’s Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume X show.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia incidence was highest for men in Canada (4.5 per 100,000), Ireland and Lithuania (4.4), and Slovakia (4.3). The incidence was highest for women in Lithuania (2.5), Canada (2.3), and Slovakia and Denmark (2.1). Incidence in the United States was 3.5 for men and 1.8 for women. At the other end of the scale, the lowest rates for both men and women were in Japan and Malaysia (0.1), the investigators’ analysis showed.

Chronic myeloid leukemia rates were the lowest of the subtypes, and Tunisia was the lowest for men at 0.4 per 100,000 and tied for lowest with Serbia, Slovenia, and Puerto Rico for women at 0.3. Incidence was highest for men in Australia at 1.8 per 100,000 and highest for women in Uruguay at 1.1. Rates in the United States were 1.3 for men and 0.8 for women, Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

“The higher incidence of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in parts of South America, as well as of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in populations across North America and Oceania, alongside a lower incidence in Asia, might be important markers for further epidemiological study, and a means to better understand the underlying factors to support future cancer prevention strategies,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Miranda-Filho A et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e14-24.

, according to an analysis of World Health Organization cancer databases.

Incidence also is generally higher in males, with a global male to female ratio of 1.4. For men, the highest regional leukemia rate – estimated at 11.3 per 100,000 population for 2012 – was found in Australia and New Zealand, with northern America (the United States and Canada) next at 10.5 per 100,000. Australia/New Zealand and northern America had the highest rate for women at 7.2 per 100,000, followed by western Europe and northern Europe at 6.0 per 100,000, reported Adalberto Miranda-Filho, PhD, of the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and his associates.

The lowest regional rates for women were found in western Africa (1.2 per 100,000), middle Africa (1.8), and Micronesia/Polynesia (2.1). For men, leukemia incidence was lowest in western Africa (1.4 per 100,000), middle Africa (2.6), and south-central Asia (3.4), according to data from the WHO’s GLOBOCAN database. The report was published in The Lancet Haematology.

Estimates for leukemia subtypes in 2003-2007 – calculated for 54 countries, not regions – also showed a great deal of variation. For acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Ecuador had the highest rates for both males (2.8 per 100,000) and females (3.3), with high rates seen in Costa Rica, Columbia, and Cyprus. Rates in the United States were near the top: 2.1 for males and 1.6 for females. Rates were lowest for men in Jamaica (0.4) and Serbia (0.6) and for women in India (0.5) and Serbia and Cuba (0.6), Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

Incidence rates for acute myeloid leukemia were highest in Australia for men (2.8 per 100,000) and Austria for women (2.2), with the United States near the top for both men (2.6) and women (1.9). The lowest rates occurred in Cuba and Egypt for men (0.9 per 100,000) and Cuba for women (0.4), data from the WHO’s Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume X show.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia incidence was highest for men in Canada (4.5 per 100,000), Ireland and Lithuania (4.4), and Slovakia (4.3). The incidence was highest for women in Lithuania (2.5), Canada (2.3), and Slovakia and Denmark (2.1). Incidence in the United States was 3.5 for men and 1.8 for women. At the other end of the scale, the lowest rates for both men and women were in Japan and Malaysia (0.1), the investigators’ analysis showed.

Chronic myeloid leukemia rates were the lowest of the subtypes, and Tunisia was the lowest for men at 0.4 per 100,000 and tied for lowest with Serbia, Slovenia, and Puerto Rico for women at 0.3. Incidence was highest for men in Australia at 1.8 per 100,000 and highest for women in Uruguay at 1.1. Rates in the United States were 1.3 for men and 0.8 for women, Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

“The higher incidence of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in parts of South America, as well as of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in populations across North America and Oceania, alongside a lower incidence in Asia, might be important markers for further epidemiological study, and a means to better understand the underlying factors to support future cancer prevention strategies,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Miranda-Filho A et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e14-24.

FROM THE LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Dolutegravir-based regimen effective in HIV/TB coinfected

BOSTON – In antiretroviral therapy–naive patients with HIV and tuberculosis coinfection, a combination of dolutegravir-based ART and rifampin-based TB therapy was associated with good efficacy and immunological responses through at least 24 weeks, investigators reported.

Dolutegravir-based ART appeared to be comparable to efavirenz-based therapy at viral suppression with a similar safety profile, although the trial was not powered for head-to-head comparison, said Kelly Dooley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“We know that rifampin reduces concentrations of dolutegravir substantially, but that drug interaction can be mitigated by increasing the dose of dolutegravir to twice daily. That information was from a healthy volunteer trial, so we thought it would be important to test HIV/TB cotreatment among patients who have both infections,” she said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Dr. Dooley and her colleagues looked at dolutegravir or efavirenz plus rifampin-based TB therapy in the INSPIRING trial.

The ongoing study is a phase 3b, noncomparative, randomized, open-label trial in ART-naive adults with HIV-1 and drug-sensitive TB infections.

In a briefing following her presentation of the data in an oral session, Dr. Dooley explained that the reason for the parallel but noncomparative arms in the trial was that it was primarily designed to see how dolutegravir works in HIV/TB coinfected patients. Enrollment of 113 patients from 37 sites in seven countries took about 2 years, and it would have required significantly more time to enroll the more than 500 patients necessary for an adequately powered comparison trial.

The trial was conducted in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Russia, South Africa, and Thailand. Dr. Dooley presented results from a 24-week interim analysis.

Participants who were on rifampin-based TB therapy for up to 8 weeks were randomized on a 3:2 basis to receive either dolutegravir 50 mg twice daily during and for 2 weeks post-TB therapy, followed by 50 mg once daily (69 patients), or efavirenz 600 mg daily plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors of the investigator’s choice for 52 weeks.

At 24 weeks, the percentage of patients deemed to have virologic success, defined as HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/mL, was 81% in the dolutegravir arm and 89% in the efavirenz arm. The respective rates of virologic nonresponse were 10% and 7%. No virologic data were available because of treatment discontinuations or missing information for 9% and 5% of patients, respectively.

The difference in response rates between the arms was due to non–treatment associated withdrawals among patients on dolutegravir, Dr. Dooley said.

Virologic withdrawals for confirmed plasma HIV-1 RNA of 400 copies/mL or more at or after week 24 for two consecutive tests occurred in one patient on dolutegravir and in none on efavirenz. There were no treatment-emergent resistance-associated mutations to any anti-HIV drugs in the dolutegravir group (data not available for the efavirenz group).

Two patients, both in the efavirenz arm, discontinued therapy because of adverse events. TB-associated rates of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) occurred in 4% of patients in each treatment arm. No patients discontinued therapy because of IRIS or liver-related adverse events.

“We think that this study provides evidence that dolutegravir is effective and well tolerated in adults with HIV/TB coinfection who are receiving rifampin-based tuberculosis therapy, and we hope that this will increase the number of options for TB/HIV coinfected patients for whom there are relatively few treatment possibilities,” she concluded.

Dr. Dooley reported research support via her university from ViiV Healthcare, which funded the study.

SOURCE: Dooley K et al. Abstract 33.

BOSTON – In antiretroviral therapy–naive patients with HIV and tuberculosis coinfection, a combination of dolutegravir-based ART and rifampin-based TB therapy was associated with good efficacy and immunological responses through at least 24 weeks, investigators reported.

Dolutegravir-based ART appeared to be comparable to efavirenz-based therapy at viral suppression with a similar safety profile, although the trial was not powered for head-to-head comparison, said Kelly Dooley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“We know that rifampin reduces concentrations of dolutegravir substantially, but that drug interaction can be mitigated by increasing the dose of dolutegravir to twice daily. That information was from a healthy volunteer trial, so we thought it would be important to test HIV/TB cotreatment among patients who have both infections,” she said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Dr. Dooley and her colleagues looked at dolutegravir or efavirenz plus rifampin-based TB therapy in the INSPIRING trial.

The ongoing study is a phase 3b, noncomparative, randomized, open-label trial in ART-naive adults with HIV-1 and drug-sensitive TB infections.

In a briefing following her presentation of the data in an oral session, Dr. Dooley explained that the reason for the parallel but noncomparative arms in the trial was that it was primarily designed to see how dolutegravir works in HIV/TB coinfected patients. Enrollment of 113 patients from 37 sites in seven countries took about 2 years, and it would have required significantly more time to enroll the more than 500 patients necessary for an adequately powered comparison trial.

The trial was conducted in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Russia, South Africa, and Thailand. Dr. Dooley presented results from a 24-week interim analysis.

Participants who were on rifampin-based TB therapy for up to 8 weeks were randomized on a 3:2 basis to receive either dolutegravir 50 mg twice daily during and for 2 weeks post-TB therapy, followed by 50 mg once daily (69 patients), or efavirenz 600 mg daily plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors of the investigator’s choice for 52 weeks.

At 24 weeks, the percentage of patients deemed to have virologic success, defined as HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/mL, was 81% in the dolutegravir arm and 89% in the efavirenz arm. The respective rates of virologic nonresponse were 10% and 7%. No virologic data were available because of treatment discontinuations or missing information for 9% and 5% of patients, respectively.

The difference in response rates between the arms was due to non–treatment associated withdrawals among patients on dolutegravir, Dr. Dooley said.

Virologic withdrawals for confirmed plasma HIV-1 RNA of 400 copies/mL or more at or after week 24 for two consecutive tests occurred in one patient on dolutegravir and in none on efavirenz. There were no treatment-emergent resistance-associated mutations to any anti-HIV drugs in the dolutegravir group (data not available for the efavirenz group).

Two patients, both in the efavirenz arm, discontinued therapy because of adverse events. TB-associated rates of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) occurred in 4% of patients in each treatment arm. No patients discontinued therapy because of IRIS or liver-related adverse events.

“We think that this study provides evidence that dolutegravir is effective and well tolerated in adults with HIV/TB coinfection who are receiving rifampin-based tuberculosis therapy, and we hope that this will increase the number of options for TB/HIV coinfected patients for whom there are relatively few treatment possibilities,” she concluded.

Dr. Dooley reported research support via her university from ViiV Healthcare, which funded the study.

SOURCE: Dooley K et al. Abstract 33.

BOSTON – In antiretroviral therapy–naive patients with HIV and tuberculosis coinfection, a combination of dolutegravir-based ART and rifampin-based TB therapy was associated with good efficacy and immunological responses through at least 24 weeks, investigators reported.

Dolutegravir-based ART appeared to be comparable to efavirenz-based therapy at viral suppression with a similar safety profile, although the trial was not powered for head-to-head comparison, said Kelly Dooley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“We know that rifampin reduces concentrations of dolutegravir substantially, but that drug interaction can be mitigated by increasing the dose of dolutegravir to twice daily. That information was from a healthy volunteer trial, so we thought it would be important to test HIV/TB cotreatment among patients who have both infections,” she said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Dr. Dooley and her colleagues looked at dolutegravir or efavirenz plus rifampin-based TB therapy in the INSPIRING trial.

The ongoing study is a phase 3b, noncomparative, randomized, open-label trial in ART-naive adults with HIV-1 and drug-sensitive TB infections.

In a briefing following her presentation of the data in an oral session, Dr. Dooley explained that the reason for the parallel but noncomparative arms in the trial was that it was primarily designed to see how dolutegravir works in HIV/TB coinfected patients. Enrollment of 113 patients from 37 sites in seven countries took about 2 years, and it would have required significantly more time to enroll the more than 500 patients necessary for an adequately powered comparison trial.

The trial was conducted in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Russia, South Africa, and Thailand. Dr. Dooley presented results from a 24-week interim analysis.

Participants who were on rifampin-based TB therapy for up to 8 weeks were randomized on a 3:2 basis to receive either dolutegravir 50 mg twice daily during and for 2 weeks post-TB therapy, followed by 50 mg once daily (69 patients), or efavirenz 600 mg daily plus two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors of the investigator’s choice for 52 weeks.

At 24 weeks, the percentage of patients deemed to have virologic success, defined as HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/mL, was 81% in the dolutegravir arm and 89% in the efavirenz arm. The respective rates of virologic nonresponse were 10% and 7%. No virologic data were available because of treatment discontinuations or missing information for 9% and 5% of patients, respectively.

The difference in response rates between the arms was due to non–treatment associated withdrawals among patients on dolutegravir, Dr. Dooley said.

Virologic withdrawals for confirmed plasma HIV-1 RNA of 400 copies/mL or more at or after week 24 for two consecutive tests occurred in one patient on dolutegravir and in none on efavirenz. There were no treatment-emergent resistance-associated mutations to any anti-HIV drugs in the dolutegravir group (data not available for the efavirenz group).

Two patients, both in the efavirenz arm, discontinued therapy because of adverse events. TB-associated rates of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) occurred in 4% of patients in each treatment arm. No patients discontinued therapy because of IRIS or liver-related adverse events.

“We think that this study provides evidence that dolutegravir is effective and well tolerated in adults with HIV/TB coinfection who are receiving rifampin-based tuberculosis therapy, and we hope that this will increase the number of options for TB/HIV coinfected patients for whom there are relatively few treatment possibilities,” she concluded.

Dr. Dooley reported research support via her university from ViiV Healthcare, which funded the study.

SOURCE: Dooley K et al. Abstract 33.

REPORTING FROM CROI

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The virologic response rate at 24 weeks with dolutegravir was 81%.

Data source: Randomized noncomparative trial of 113 patients with HIV/TB coinfections in seven countries.

Disclosures: Dr. Dooley reported research support via her university from ViiV Healthcare, which funded the study.

Source: Dooley K et al. Abstract 33.

Levodopa Monotherapy May Be Adequate After DBS for Parkinson’s Disease

LAS VEGAS—For pharmacotherapy following deep brain stimulation (DBS), many patients can be adequately treated with levodopa alone, but only a small group can be managed with dopamine agonists alone, according to a study presented at the 21st Annual Meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. The data address a question about which there has been little objective guidance.

Based on the findings, efforts to reduce anti-Parkinson’s disease medications following DBS should be directed toward dopamine agonists first, according to Alfonso Fasano, MD, PhD, Codirector of the Surgical Program at the Movement Disorder Center of Toronto Western Hospital in Ontario. The data nevertheless provide the option for individualized therapy, he added. For example, for patients with good outcome after DBS and no significant history of impulse-

In the randomized controlled trial, 36 patients were assigned to receive monotherapy with a dopamine agonist or levodopa following subthalamic nucleus (STN) DBS. All patients were on both medications before surgery. The investigators did not identify any between-group differences in variables predicted to affect symptom control. Yet the proportion of patients that were able to stay on monotherapy at three months was different between the study arms.

“Perhaps the main result of this study was that we found it difficult to keep patients on dopamine-agonist monotherapy, even after a successful DBS procedure,” said Dr. Fasano.

At three months after surgery, the proportion of patients remaining on monotherapy was 81% in the levodopa group and 32% in the dopamine-agonist group. At that point in the follow-up, all other patients in the two groups were on both treatments. At six months, fewer patients were taking their assigned drug as a monotherapy. The proportion in the levodopa arm had decreased to 63%, and the proportion in the dopamine-agonist arm had decreased to 13%.

More of the failures in the dopamine-agonist arm, relative to the levodopa arm, resulted from inadequate control of motor symptoms. Failure in the levodopa arm more commonly occurred following mood and sleep disturbances. But the investigators observed failures for both reasons in both study arms.

DBS permits a reduction in anti-Parkinson’s disease medications, but dose reductions should be undertaken slowly, because mood disturbances have been reported after abrupt discontinuation of dopamine agonists, according to Dr. Fasano. Specific strategies for reducing anti-Parkinson’s disease medications following DBS have not been based on evidence, however.

Overall, the results of the randomized study “are in keeping with a common-sense” approach, Dr. Fasano said. While the results emphasize the limited proportion of patients who can remain on dopamine agonists alone following DBS, they also suggest that most patients receiving levodopa will require low doses of both therapies.

With these results and observations, “maybe we are getting closer to a guideline of what to do with respect to medication after surgery,” Dr. Fasano said.

—Ted Bosworth

Suggested Reading

Fasano A, Appel-Cresswell S, Jog M, et al. Medical management of Parkinson’s disease after initiation of deep brain stimulation. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(5):626-634.

LAS VEGAS—For pharmacotherapy following deep brain stimulation (DBS), many patients can be adequately treated with levodopa alone, but only a small group can be managed with dopamine agonists alone, according to a study presented at the 21st Annual Meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. The data address a question about which there has been little objective guidance.

Based on the findings, efforts to reduce anti-Parkinson’s disease medications following DBS should be directed toward dopamine agonists first, according to Alfonso Fasano, MD, PhD, Codirector of the Surgical Program at the Movement Disorder Center of Toronto Western Hospital in Ontario. The data nevertheless provide the option for individualized therapy, he added. For example, for patients with good outcome after DBS and no significant history of impulse-

In the randomized controlled trial, 36 patients were assigned to receive monotherapy with a dopamine agonist or levodopa following subthalamic nucleus (STN) DBS. All patients were on both medications before surgery. The investigators did not identify any between-group differences in variables predicted to affect symptom control. Yet the proportion of patients that were able to stay on monotherapy at three months was different between the study arms.

“Perhaps the main result of this study was that we found it difficult to keep patients on dopamine-agonist monotherapy, even after a successful DBS procedure,” said Dr. Fasano.

At three months after surgery, the proportion of patients remaining on monotherapy was 81% in the levodopa group and 32% in the dopamine-agonist group. At that point in the follow-up, all other patients in the two groups were on both treatments. At six months, fewer patients were taking their assigned drug as a monotherapy. The proportion in the levodopa arm had decreased to 63%, and the proportion in the dopamine-agonist arm had decreased to 13%.

More of the failures in the dopamine-agonist arm, relative to the levodopa arm, resulted from inadequate control of motor symptoms. Failure in the levodopa arm more commonly occurred following mood and sleep disturbances. But the investigators observed failures for both reasons in both study arms.

DBS permits a reduction in anti-Parkinson’s disease medications, but dose reductions should be undertaken slowly, because mood disturbances have been reported after abrupt discontinuation of dopamine agonists, according to Dr. Fasano. Specific strategies for reducing anti-Parkinson’s disease medications following DBS have not been based on evidence, however.

Overall, the results of the randomized study “are in keeping with a common-sense” approach, Dr. Fasano said. While the results emphasize the limited proportion of patients who can remain on dopamine agonists alone following DBS, they also suggest that most patients receiving levodopa will require low doses of both therapies.

With these results and observations, “maybe we are getting closer to a guideline of what to do with respect to medication after surgery,” Dr. Fasano said.

—Ted Bosworth

Suggested Reading

Fasano A, Appel-Cresswell S, Jog M, et al. Medical management of Parkinson’s disease after initiation of deep brain stimulation. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(5):626-634.

LAS VEGAS—For pharmacotherapy following deep brain stimulation (DBS), many patients can be adequately treated with levodopa alone, but only a small group can be managed with dopamine agonists alone, according to a study presented at the 21st Annual Meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. The data address a question about which there has been little objective guidance.

Based on the findings, efforts to reduce anti-Parkinson’s disease medications following DBS should be directed toward dopamine agonists first, according to Alfonso Fasano, MD, PhD, Codirector of the Surgical Program at the Movement Disorder Center of Toronto Western Hospital in Ontario. The data nevertheless provide the option for individualized therapy, he added. For example, for patients with good outcome after DBS and no significant history of impulse-

In the randomized controlled trial, 36 patients were assigned to receive monotherapy with a dopamine agonist or levodopa following subthalamic nucleus (STN) DBS. All patients were on both medications before surgery. The investigators did not identify any between-group differences in variables predicted to affect symptom control. Yet the proportion of patients that were able to stay on monotherapy at three months was different between the study arms.

“Perhaps the main result of this study was that we found it difficult to keep patients on dopamine-agonist monotherapy, even after a successful DBS procedure,” said Dr. Fasano.

At three months after surgery, the proportion of patients remaining on monotherapy was 81% in the levodopa group and 32% in the dopamine-agonist group. At that point in the follow-up, all other patients in the two groups were on both treatments. At six months, fewer patients were taking their assigned drug as a monotherapy. The proportion in the levodopa arm had decreased to 63%, and the proportion in the dopamine-agonist arm had decreased to 13%.

More of the failures in the dopamine-agonist arm, relative to the levodopa arm, resulted from inadequate control of motor symptoms. Failure in the levodopa arm more commonly occurred following mood and sleep disturbances. But the investigators observed failures for both reasons in both study arms.

DBS permits a reduction in anti-Parkinson’s disease medications, but dose reductions should be undertaken slowly, because mood disturbances have been reported after abrupt discontinuation of dopamine agonists, according to Dr. Fasano. Specific strategies for reducing anti-Parkinson’s disease medications following DBS have not been based on evidence, however.