User login

Disc Degeneration in Chronic Low Back Pain: Can Stem Cells Help?

TOPLINE:

Allogeneic bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells (BM-MSCs) are safe but do not show efficacy in treating intervertebral disc degeneration (IDD) in patients with chronic low back pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- The RESPINE trial assessed the efficacy and safety of a single intradiscal injection of allogeneic BM-MSCs in the treatment of chronic low back pain caused by single-level IDD.

- Overall, 114 patients (mean age, 40.9 years; 35% women) with IDD-associated chronic low back pain that was persistent for 3 months or more despite conventional medical therapy and without previous surgery, were recruited across four European countries from April 2018 to April 2021 and randomly assigned to receive either intradiscal injections of allogeneic BM-MSCs (n = 58) or sham injections (n = 56).

- The first co-primary endpoint was the rate of response to BM-MSC injections at 12 months after treatment, defined as improvement of at least 20% or 20 mm in the Visual Analog Scale for pain or improvement of at least 20% in the Oswestry Disability Index for functional status.

- The secondary co-primary endpoint was structural efficacy, based on disc fluid content measured by quantitative T2 MRI between baseline and month 12.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 12 months post-intervention, 74% of patients in the BM-MSC group were classified as responders compared with 68.8% in the placebo group. However, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant.

- The probability of being a responder was higher in the BM-MSC group than in the sham group; however, the findings did not reach statistical significance.

- The average change in disc fluid content, indicative of disc regeneration, from baseline to 12 months was 37.9% in the BM-MSC group and 41.7% in the placebo group, with no significant difference between the groups.

- The incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events was not significantly different between the treatment groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“BM-MSC represents a promising opportunity for the biological treatment of IDD, but only high-quality randomized controlled trials, comparing it to standard care, can determine whether it is a truly effective alternative to spine fusion or disc replacement,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yves-Marie Pers, MD, PhD, Clinical Immunology and Osteoarticular Diseases Therapeutic Unit, CHRU Lapeyronie, Montpellier, France. It was published online on October 11, 2024, in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

MRI results were collected from only 55 patients across both trial arms, which may have affected the statistical power of the findings. Although patients were monitored for up to 24 months, the long-term efficacy and safety of BM-MSC therapy for IDD may not have been fully captured. Selection bias could not be excluded because of the difficulty in accurately identifying patients with chronic low back pain caused by single-level IDD.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Allogeneic bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells (BM-MSCs) are safe but do not show efficacy in treating intervertebral disc degeneration (IDD) in patients with chronic low back pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- The RESPINE trial assessed the efficacy and safety of a single intradiscal injection of allogeneic BM-MSCs in the treatment of chronic low back pain caused by single-level IDD.

- Overall, 114 patients (mean age, 40.9 years; 35% women) with IDD-associated chronic low back pain that was persistent for 3 months or more despite conventional medical therapy and without previous surgery, were recruited across four European countries from April 2018 to April 2021 and randomly assigned to receive either intradiscal injections of allogeneic BM-MSCs (n = 58) or sham injections (n = 56).

- The first co-primary endpoint was the rate of response to BM-MSC injections at 12 months after treatment, defined as improvement of at least 20% or 20 mm in the Visual Analog Scale for pain or improvement of at least 20% in the Oswestry Disability Index for functional status.

- The secondary co-primary endpoint was structural efficacy, based on disc fluid content measured by quantitative T2 MRI between baseline and month 12.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 12 months post-intervention, 74% of patients in the BM-MSC group were classified as responders compared with 68.8% in the placebo group. However, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant.

- The probability of being a responder was higher in the BM-MSC group than in the sham group; however, the findings did not reach statistical significance.

- The average change in disc fluid content, indicative of disc regeneration, from baseline to 12 months was 37.9% in the BM-MSC group and 41.7% in the placebo group, with no significant difference between the groups.

- The incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events was not significantly different between the treatment groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“BM-MSC represents a promising opportunity for the biological treatment of IDD, but only high-quality randomized controlled trials, comparing it to standard care, can determine whether it is a truly effective alternative to spine fusion or disc replacement,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yves-Marie Pers, MD, PhD, Clinical Immunology and Osteoarticular Diseases Therapeutic Unit, CHRU Lapeyronie, Montpellier, France. It was published online on October 11, 2024, in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

MRI results were collected from only 55 patients across both trial arms, which may have affected the statistical power of the findings. Although patients were monitored for up to 24 months, the long-term efficacy and safety of BM-MSC therapy for IDD may not have been fully captured. Selection bias could not be excluded because of the difficulty in accurately identifying patients with chronic low back pain caused by single-level IDD.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Allogeneic bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells (BM-MSCs) are safe but do not show efficacy in treating intervertebral disc degeneration (IDD) in patients with chronic low back pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- The RESPINE trial assessed the efficacy and safety of a single intradiscal injection of allogeneic BM-MSCs in the treatment of chronic low back pain caused by single-level IDD.

- Overall, 114 patients (mean age, 40.9 years; 35% women) with IDD-associated chronic low back pain that was persistent for 3 months or more despite conventional medical therapy and without previous surgery, were recruited across four European countries from April 2018 to April 2021 and randomly assigned to receive either intradiscal injections of allogeneic BM-MSCs (n = 58) or sham injections (n = 56).

- The first co-primary endpoint was the rate of response to BM-MSC injections at 12 months after treatment, defined as improvement of at least 20% or 20 mm in the Visual Analog Scale for pain or improvement of at least 20% in the Oswestry Disability Index for functional status.

- The secondary co-primary endpoint was structural efficacy, based on disc fluid content measured by quantitative T2 MRI between baseline and month 12.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 12 months post-intervention, 74% of patients in the BM-MSC group were classified as responders compared with 68.8% in the placebo group. However, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant.

- The probability of being a responder was higher in the BM-MSC group than in the sham group; however, the findings did not reach statistical significance.

- The average change in disc fluid content, indicative of disc regeneration, from baseline to 12 months was 37.9% in the BM-MSC group and 41.7% in the placebo group, with no significant difference between the groups.

- The incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events was not significantly different between the treatment groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“BM-MSC represents a promising opportunity for the biological treatment of IDD, but only high-quality randomized controlled trials, comparing it to standard care, can determine whether it is a truly effective alternative to spine fusion or disc replacement,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yves-Marie Pers, MD, PhD, Clinical Immunology and Osteoarticular Diseases Therapeutic Unit, CHRU Lapeyronie, Montpellier, France. It was published online on October 11, 2024, in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

MRI results were collected from only 55 patients across both trial arms, which may have affected the statistical power of the findings. Although patients were monitored for up to 24 months, the long-term efficacy and safety of BM-MSC therapy for IDD may not have been fully captured. Selection bias could not be excluded because of the difficulty in accurately identifying patients with chronic low back pain caused by single-level IDD.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Duloxetine Bottles Recalled by FDA Because of Potential Carcinogen

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced a voluntary manufacturer-initiated recall of more than 7000 bottles of duloxetine delayed-release capsules due to unacceptable levels of a potential carcinogen.

Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor used to treat major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

The recall is due to the detection of the nitrosamine impurity, N-nitroso duloxetine, above the proposed interim limit.

Nitrosamines are common in water and foods, and exposure to some levels of the chemical is common. Exposure to nitrosamine impurities above acceptable levels and over long periods may increase cancer risk, the FDA reported.

“If drugs contain levels of nitrosamines above the acceptable daily intake limits, FDA recommends these drugs be recalled by the manufacturer as appropriate,” the agency noted on its website.

The recall was initiated by Breckenridge Pharmaceutical and covers 7107 bottles of 500-count, 20 mg duloxetine delayed-release capsules. The drug is manufactured by Towa Pharmaceutical Europe and distributed nationwide by BPI.

The affected bottles are from lot number 220128 with an expiration date of 12/2024 and NDC of 51991-746-05.

The recall was initiated on October 10 and is ongoing.

“Healthcare professionals can educate patients about alternative treatment options to medications with potential nitrosamine impurities if available and clinically appropriate,” the FDA advises. “If a medication has been recalled, pharmacists may be able to dispense the same medication from a manufacturing lot that has not been recalled. Prescribers may also determine whether there is an alternative treatment option for patients.”

The FDA has labeled this a “class II” recall, which the agency defines as “a situation in which use of or exposure to a violative product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences or where the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote.”

Nitrosamine impurities have prompted a number of drug recalls in recent years, including oral anticoagulants, metformin, and skeletal muscle relaxants.

The impurities may be found in drugs for a number of reasons, the agency reported. The source may be from a drug’s manufacturing process, chemical structure, or the conditions under which it is stored or packaged.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced a voluntary manufacturer-initiated recall of more than 7000 bottles of duloxetine delayed-release capsules due to unacceptable levels of a potential carcinogen.

Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor used to treat major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

The recall is due to the detection of the nitrosamine impurity, N-nitroso duloxetine, above the proposed interim limit.

Nitrosamines are common in water and foods, and exposure to some levels of the chemical is common. Exposure to nitrosamine impurities above acceptable levels and over long periods may increase cancer risk, the FDA reported.

“If drugs contain levels of nitrosamines above the acceptable daily intake limits, FDA recommends these drugs be recalled by the manufacturer as appropriate,” the agency noted on its website.

The recall was initiated by Breckenridge Pharmaceutical and covers 7107 bottles of 500-count, 20 mg duloxetine delayed-release capsules. The drug is manufactured by Towa Pharmaceutical Europe and distributed nationwide by BPI.

The affected bottles are from lot number 220128 with an expiration date of 12/2024 and NDC of 51991-746-05.

The recall was initiated on October 10 and is ongoing.

“Healthcare professionals can educate patients about alternative treatment options to medications with potential nitrosamine impurities if available and clinically appropriate,” the FDA advises. “If a medication has been recalled, pharmacists may be able to dispense the same medication from a manufacturing lot that has not been recalled. Prescribers may also determine whether there is an alternative treatment option for patients.”

The FDA has labeled this a “class II” recall, which the agency defines as “a situation in which use of or exposure to a violative product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences or where the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote.”

Nitrosamine impurities have prompted a number of drug recalls in recent years, including oral anticoagulants, metformin, and skeletal muscle relaxants.

The impurities may be found in drugs for a number of reasons, the agency reported. The source may be from a drug’s manufacturing process, chemical structure, or the conditions under which it is stored or packaged.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced a voluntary manufacturer-initiated recall of more than 7000 bottles of duloxetine delayed-release capsules due to unacceptable levels of a potential carcinogen.

Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor used to treat major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

The recall is due to the detection of the nitrosamine impurity, N-nitroso duloxetine, above the proposed interim limit.

Nitrosamines are common in water and foods, and exposure to some levels of the chemical is common. Exposure to nitrosamine impurities above acceptable levels and over long periods may increase cancer risk, the FDA reported.

“If drugs contain levels of nitrosamines above the acceptable daily intake limits, FDA recommends these drugs be recalled by the manufacturer as appropriate,” the agency noted on its website.

The recall was initiated by Breckenridge Pharmaceutical and covers 7107 bottles of 500-count, 20 mg duloxetine delayed-release capsules. The drug is manufactured by Towa Pharmaceutical Europe and distributed nationwide by BPI.

The affected bottles are from lot number 220128 with an expiration date of 12/2024 and NDC of 51991-746-05.

The recall was initiated on October 10 and is ongoing.

“Healthcare professionals can educate patients about alternative treatment options to medications with potential nitrosamine impurities if available and clinically appropriate,” the FDA advises. “If a medication has been recalled, pharmacists may be able to dispense the same medication from a manufacturing lot that has not been recalled. Prescribers may also determine whether there is an alternative treatment option for patients.”

The FDA has labeled this a “class II” recall, which the agency defines as “a situation in which use of or exposure to a violative product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences or where the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote.”

Nitrosamine impurities have prompted a number of drug recalls in recent years, including oral anticoagulants, metformin, and skeletal muscle relaxants.

The impurities may be found in drugs for a number of reasons, the agency reported. The source may be from a drug’s manufacturing process, chemical structure, or the conditions under which it is stored or packaged.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Mepivacaine Reduces Pain During IUD Placement in Nulliparous Women

TOPLINE:

Mepivacaine instillation significantly reduced pain during intrauterine device (IUD) placement in nulliparous women. More than 90% of women in the intervention group reported tolerable pain compared with 80% of those in the placebo group.

METHODOLOGY:

- A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in 12 centers in Sweden, which involved 151 nulliparous women aged 18-31 years.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive either 10 mL of 20 mg/mL mepivacaine or 10 mL of 0.9 mg/mL sodium chloride (placebo) through a hydrosonography catheter 2 minutes before IUD placement.

- Pain scores were measured using a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) at baseline, after instillation, during IUD placement, and 10 minutes post placement.

- The primary outcome was the difference in VAS pain scores during IUD placement between the intervention and placebo groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Mepivacaine instillation resulted in a statistically significant reduction in mean VAS pain scores during IUD placement, with a mean difference of 13.3 mm (95% CI, 5.75-20.87; P < .001).

- After adjusting for provider impact, the mean VAS pain score difference remained significant at 12.2 mm (95% CI, 4.85-19.62; P < .001).

- A higher proportion of women in the mepivacaine group reported tolerable pain during IUD placement (93.3%) than the placebo group (80.3%; P = .021).

- No serious adverse effects were associated with mepivacaine instillation, and there were no cases of uterine perforation in either group.

IN PRACTICE:

“We argue that the pain reduction in our study is clinically important as a greater proportion of women in our intervention group, compared to the placebo group, reported tolerable pain during placement and to a higher extent rated the placement as easier than expected and expressed a willingness to choose IUD as contraception again,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Niklas Envall, PhD; Karin Elgemark, MD; and Helena Kopp Kallner, MD, PhD, at the Department of Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden. It was published online in American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study’s limitations included the exclusive focus on one type of IUD (LNG-IUS 52 mg, 4.4 mm), which may limit generalizability to other IUD types. Additionally, only experienced providers participated, which may not reflect settings with less experienced providers. Factors such as anticipated pain and patient anxiety were not systematically assessed, potentially influencing pain perception.

DISCLOSURES:

Envall received personal fees from Bayer for educational activities and honorarium from Medsphere Corp USA for expert opinions on long-acting reversible contraception. Kallner received honoraria for consultancy work and lectures from multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Actavis, Bayer, and others. The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mepivacaine instillation significantly reduced pain during intrauterine device (IUD) placement in nulliparous women. More than 90% of women in the intervention group reported tolerable pain compared with 80% of those in the placebo group.

METHODOLOGY:

- A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in 12 centers in Sweden, which involved 151 nulliparous women aged 18-31 years.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive either 10 mL of 20 mg/mL mepivacaine or 10 mL of 0.9 mg/mL sodium chloride (placebo) through a hydrosonography catheter 2 minutes before IUD placement.

- Pain scores were measured using a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) at baseline, after instillation, during IUD placement, and 10 minutes post placement.

- The primary outcome was the difference in VAS pain scores during IUD placement between the intervention and placebo groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Mepivacaine instillation resulted in a statistically significant reduction in mean VAS pain scores during IUD placement, with a mean difference of 13.3 mm (95% CI, 5.75-20.87; P < .001).

- After adjusting for provider impact, the mean VAS pain score difference remained significant at 12.2 mm (95% CI, 4.85-19.62; P < .001).

- A higher proportion of women in the mepivacaine group reported tolerable pain during IUD placement (93.3%) than the placebo group (80.3%; P = .021).

- No serious adverse effects were associated with mepivacaine instillation, and there were no cases of uterine perforation in either group.

IN PRACTICE:

“We argue that the pain reduction in our study is clinically important as a greater proportion of women in our intervention group, compared to the placebo group, reported tolerable pain during placement and to a higher extent rated the placement as easier than expected and expressed a willingness to choose IUD as contraception again,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Niklas Envall, PhD; Karin Elgemark, MD; and Helena Kopp Kallner, MD, PhD, at the Department of Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden. It was published online in American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study’s limitations included the exclusive focus on one type of IUD (LNG-IUS 52 mg, 4.4 mm), which may limit generalizability to other IUD types. Additionally, only experienced providers participated, which may not reflect settings with less experienced providers. Factors such as anticipated pain and patient anxiety were not systematically assessed, potentially influencing pain perception.

DISCLOSURES:

Envall received personal fees from Bayer for educational activities and honorarium from Medsphere Corp USA for expert opinions on long-acting reversible contraception. Kallner received honoraria for consultancy work and lectures from multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Actavis, Bayer, and others. The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mepivacaine instillation significantly reduced pain during intrauterine device (IUD) placement in nulliparous women. More than 90% of women in the intervention group reported tolerable pain compared with 80% of those in the placebo group.

METHODOLOGY:

- A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in 12 centers in Sweden, which involved 151 nulliparous women aged 18-31 years.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive either 10 mL of 20 mg/mL mepivacaine or 10 mL of 0.9 mg/mL sodium chloride (placebo) through a hydrosonography catheter 2 minutes before IUD placement.

- Pain scores were measured using a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) at baseline, after instillation, during IUD placement, and 10 minutes post placement.

- The primary outcome was the difference in VAS pain scores during IUD placement between the intervention and placebo groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Mepivacaine instillation resulted in a statistically significant reduction in mean VAS pain scores during IUD placement, with a mean difference of 13.3 mm (95% CI, 5.75-20.87; P < .001).

- After adjusting for provider impact, the mean VAS pain score difference remained significant at 12.2 mm (95% CI, 4.85-19.62; P < .001).

- A higher proportion of women in the mepivacaine group reported tolerable pain during IUD placement (93.3%) than the placebo group (80.3%; P = .021).

- No serious adverse effects were associated with mepivacaine instillation, and there were no cases of uterine perforation in either group.

IN PRACTICE:

“We argue that the pain reduction in our study is clinically important as a greater proportion of women in our intervention group, compared to the placebo group, reported tolerable pain during placement and to a higher extent rated the placement as easier than expected and expressed a willingness to choose IUD as contraception again,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Niklas Envall, PhD; Karin Elgemark, MD; and Helena Kopp Kallner, MD, PhD, at the Department of Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden. It was published online in American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study’s limitations included the exclusive focus on one type of IUD (LNG-IUS 52 mg, 4.4 mm), which may limit generalizability to other IUD types. Additionally, only experienced providers participated, which may not reflect settings with less experienced providers. Factors such as anticipated pain and patient anxiety were not systematically assessed, potentially influencing pain perception.

DISCLOSURES:

Envall received personal fees from Bayer for educational activities and honorarium from Medsphere Corp USA for expert opinions on long-acting reversible contraception. Kallner received honoraria for consultancy work and lectures from multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Actavis, Bayer, and others. The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

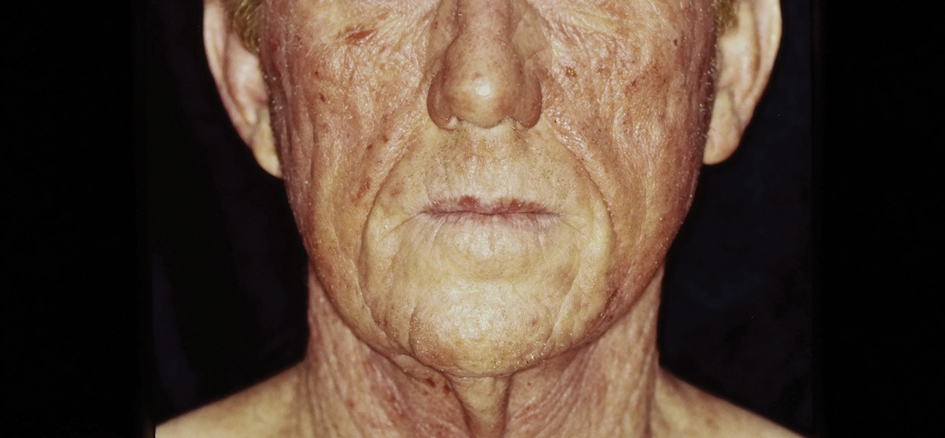

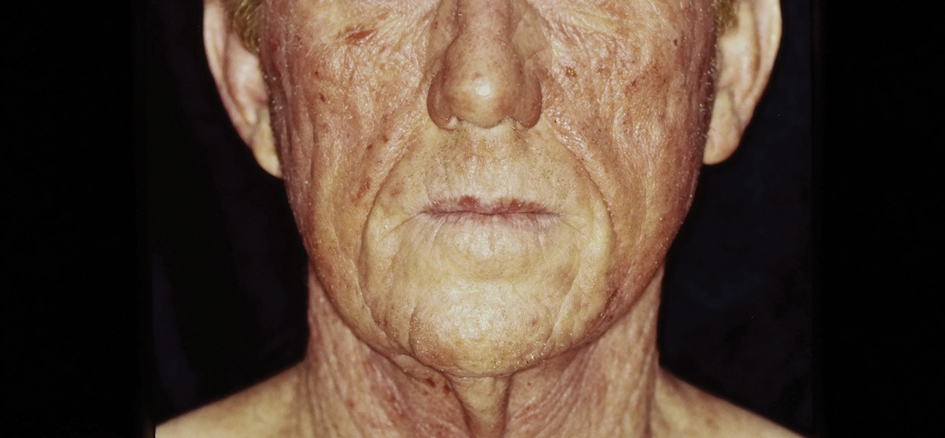

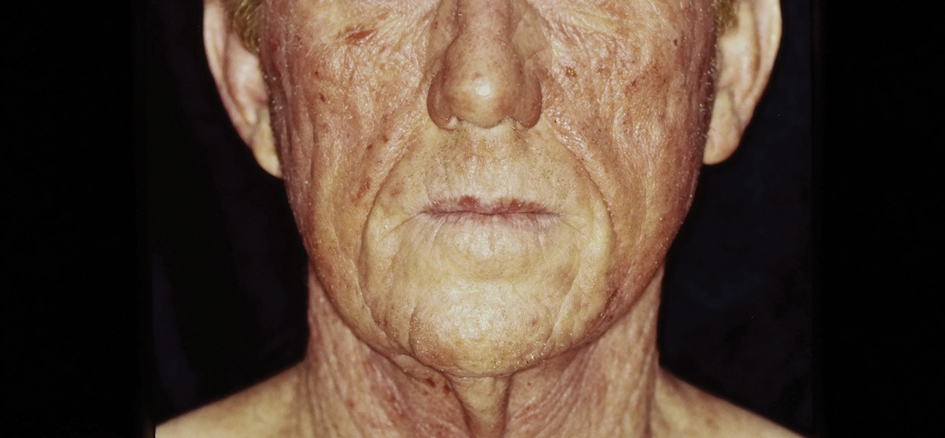

Study Finds Elevated Skin Cancer Risk Among US Veterans

of recent national data.

“US veterans are known to have increased risk of cancers and cancer morbidity compared to the general US population,” one of the study authors, Sepideh Ashrafzadeh, MD, a third-year dermatology resident at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, told this news organization following the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where the results were presented. “There have been several studies that have shown that US veterans have an increased prevalence of melanoma compared to nonveterans,” she said, noting, however, that no study has investigated the prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), which include basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, compared with the general population.

To address this knowledge gap, the researchers performed a national cross-sectional study of adults aged 18 years or older from the 2019-2023 National Health Interview Surveys to examine the prevalence of melanoma and NMSCs among veterans compared with the general US population. They aggregated and tabulated the data by veteran status, defined as having served at any point in the US armed forces, reserves, or national guard, and by demographic and socioeconomic status variables. Next, they performed multivariate logistic regression for skin cancer risk adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, urbanicity, and disability status.

The study population consisted of 14,301 veterans and 209,936 nonveterans. Compared with nonveterans, veterans were more likely to have been diagnosed with skin cancer at some point in their lives (7% vs 2.4%; P < .001); had a higher mean age of skin cancer diagnosis (61.1 vs 55.8 years; P < .001); were more likely to have been diagnosed with melanoma (2.8% vs 0.9%; P < .001), and were more likely to have been diagnosed with NMSC (4.4% vs 1.6%; P < .001).

The researchers found that older age, White race, non-Hispanic ethnicity, and veteran status were all associated with higher odds of developing NMSCs, even after adjusting for relevant covariates. Specifically, veterans had 1.23 higher odds of developing NMSC than the general population, while two factors were protective for developing NMSCs: Living in a rural setting (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.78) and receiving supplemental security income or disability income (aOR, 0.69).

In another part of the study, the researchers evaluated demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with developing melanoma among veterans. These included the following: Male (aOR, 1.16), older age (50-64 years: aOR, 6.82; 65-74 years: aOR, 12.55; and 75 years or older: aOR, 16.16), White race (aOR, 9.24), and non-Hispanic ethnicity (aOR, 7.15).

“Veterans may have occupational risks such as sun and chemical exposure, as well as behavioral habits for sun protection, that may contribute to their elevated risk of melanoma and NMSCs,” Ashrafzadeh said. “Therefore, US veterans would benefit from targeted and regular skin cancer screenings, sun protective preventative resources such as hats and sunscreen, and access to medical and surgical care for diagnosis and treatment of skin cancers.”

Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, who was asked to comment on the findings, said that a key strength of the study is that it drew from a nationally representative sample. “A limitation is that skin cancer was self-reported rather than based on documented medical histories,” Ko said. “The study confirms that skin cancer risk is higher in older individuals (> 75 as compared to < 50) and in individuals of self-reported white race and non-Hispanic ethnicity,” she added.

Neither the researchers nor Ko reported having relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

of recent national data.

“US veterans are known to have increased risk of cancers and cancer morbidity compared to the general US population,” one of the study authors, Sepideh Ashrafzadeh, MD, a third-year dermatology resident at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, told this news organization following the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where the results were presented. “There have been several studies that have shown that US veterans have an increased prevalence of melanoma compared to nonveterans,” she said, noting, however, that no study has investigated the prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), which include basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, compared with the general population.

To address this knowledge gap, the researchers performed a national cross-sectional study of adults aged 18 years or older from the 2019-2023 National Health Interview Surveys to examine the prevalence of melanoma and NMSCs among veterans compared with the general US population. They aggregated and tabulated the data by veteran status, defined as having served at any point in the US armed forces, reserves, or national guard, and by demographic and socioeconomic status variables. Next, they performed multivariate logistic regression for skin cancer risk adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, urbanicity, and disability status.

The study population consisted of 14,301 veterans and 209,936 nonveterans. Compared with nonveterans, veterans were more likely to have been diagnosed with skin cancer at some point in their lives (7% vs 2.4%; P < .001); had a higher mean age of skin cancer diagnosis (61.1 vs 55.8 years; P < .001); were more likely to have been diagnosed with melanoma (2.8% vs 0.9%; P < .001), and were more likely to have been diagnosed with NMSC (4.4% vs 1.6%; P < .001).

The researchers found that older age, White race, non-Hispanic ethnicity, and veteran status were all associated with higher odds of developing NMSCs, even after adjusting for relevant covariates. Specifically, veterans had 1.23 higher odds of developing NMSC than the general population, while two factors were protective for developing NMSCs: Living in a rural setting (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.78) and receiving supplemental security income or disability income (aOR, 0.69).

In another part of the study, the researchers evaluated demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with developing melanoma among veterans. These included the following: Male (aOR, 1.16), older age (50-64 years: aOR, 6.82; 65-74 years: aOR, 12.55; and 75 years or older: aOR, 16.16), White race (aOR, 9.24), and non-Hispanic ethnicity (aOR, 7.15).

“Veterans may have occupational risks such as sun and chemical exposure, as well as behavioral habits for sun protection, that may contribute to their elevated risk of melanoma and NMSCs,” Ashrafzadeh said. “Therefore, US veterans would benefit from targeted and regular skin cancer screenings, sun protective preventative resources such as hats and sunscreen, and access to medical and surgical care for diagnosis and treatment of skin cancers.”

Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, who was asked to comment on the findings, said that a key strength of the study is that it drew from a nationally representative sample. “A limitation is that skin cancer was self-reported rather than based on documented medical histories,” Ko said. “The study confirms that skin cancer risk is higher in older individuals (> 75 as compared to < 50) and in individuals of self-reported white race and non-Hispanic ethnicity,” she added.

Neither the researchers nor Ko reported having relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

of recent national data.

“US veterans are known to have increased risk of cancers and cancer morbidity compared to the general US population,” one of the study authors, Sepideh Ashrafzadeh, MD, a third-year dermatology resident at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, told this news organization following the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where the results were presented. “There have been several studies that have shown that US veterans have an increased prevalence of melanoma compared to nonveterans,” she said, noting, however, that no study has investigated the prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), which include basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, compared with the general population.

To address this knowledge gap, the researchers performed a national cross-sectional study of adults aged 18 years or older from the 2019-2023 National Health Interview Surveys to examine the prevalence of melanoma and NMSCs among veterans compared with the general US population. They aggregated and tabulated the data by veteran status, defined as having served at any point in the US armed forces, reserves, or national guard, and by demographic and socioeconomic status variables. Next, they performed multivariate logistic regression for skin cancer risk adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, urbanicity, and disability status.

The study population consisted of 14,301 veterans and 209,936 nonveterans. Compared with nonveterans, veterans were more likely to have been diagnosed with skin cancer at some point in their lives (7% vs 2.4%; P < .001); had a higher mean age of skin cancer diagnosis (61.1 vs 55.8 years; P < .001); were more likely to have been diagnosed with melanoma (2.8% vs 0.9%; P < .001), and were more likely to have been diagnosed with NMSC (4.4% vs 1.6%; P < .001).

The researchers found that older age, White race, non-Hispanic ethnicity, and veteran status were all associated with higher odds of developing NMSCs, even after adjusting for relevant covariates. Specifically, veterans had 1.23 higher odds of developing NMSC than the general population, while two factors were protective for developing NMSCs: Living in a rural setting (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.78) and receiving supplemental security income or disability income (aOR, 0.69).

In another part of the study, the researchers evaluated demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with developing melanoma among veterans. These included the following: Male (aOR, 1.16), older age (50-64 years: aOR, 6.82; 65-74 years: aOR, 12.55; and 75 years or older: aOR, 16.16), White race (aOR, 9.24), and non-Hispanic ethnicity (aOR, 7.15).

“Veterans may have occupational risks such as sun and chemical exposure, as well as behavioral habits for sun protection, that may contribute to their elevated risk of melanoma and NMSCs,” Ashrafzadeh said. “Therefore, US veterans would benefit from targeted and regular skin cancer screenings, sun protective preventative resources such as hats and sunscreen, and access to medical and surgical care for diagnosis and treatment of skin cancers.”

Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, who was asked to comment on the findings, said that a key strength of the study is that it drew from a nationally representative sample. “A limitation is that skin cancer was self-reported rather than based on documented medical histories,” Ko said. “The study confirms that skin cancer risk is higher in older individuals (> 75 as compared to < 50) and in individuals of self-reported white race and non-Hispanic ethnicity,” she added.

Neither the researchers nor Ko reported having relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASDS 2024

‘Small Increase’ in Breast Cancer With Levonorgestrel IUD?

TOPLINE:

The use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is associated with an increased risk for breast cancer. An analysis by Danish researchers found 14 extra cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women using this type of an intrauterine device (IUD) vs women not using hormonal contraceptives.

METHODOLOGY:

- The investigators used nationwide registries in Denmark to identify all women aged 15-49 years who were first-time initiators of any LNG-IUS between 2000 and 2019.

- They matched 78,595 new users of LNG-IUS 1:1 with women with the same birth year who were not taking hormonal contraceptives.

- Participants were followed through 2022 or until a diagnosis of breast cancer or another malignancy, pregnancy, the initiation of postmenopausal hormone therapy, emigration, or death.

- The investigators used a Cox proportional hazards model to examine the association between the continuous use of LNG-IUS and breast cancer. Their analysis adjusted for variables such as the duration of previous hormonal contraception, fertility drugs, parity, age at first delivery, polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, and education.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with the nonuse of hormonal contraceptives, the continuous use of LNG-IUS was associated with a hazard ratio for breast cancer of 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.5).

- The use of a levonorgestrel IUD for 5 years or less was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.3 (95% CI, 1.1-1.5). With 5-10 years of use, the hazard ratio was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.1-1.7). And with 10-15 years of use, the hazard ratio was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.2-2.6). A test for trend was not significant, however, and “risk did not increase with duration of use,” the study authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Women should be aware that most types of hormonal contraceptive are associated with a small increased risk of breast cancer. This study adds another type of hormonal contraceptive to that list,” Amy Berrington de Gonzalez, DPhil, professor of clinical cancer epidemiology at The Institute of Cancer Research in London, England, said in comments on the research. “That has to be considered with the many benefits from hormonal contraceptives.”

Behaviors such as smoking could have differed between the groups in the study, and it has not been established that LNG-IUS use directly causes an increased risk for breast cancer, said Channa Jayasena, PhD, an endocrinologist at Imperial College London.

“Smoking, alcohol and obesity are much more important risk factors for breast cancer than contraceptive medications,” he said. “My advice for women is that breast cancer risk caused by LNG-IUS is not established but warrants a closer look.”

SOURCE:

Lina Steinrud Mørch, MSc, PhD, with the Danish Cancer Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark, was the corresponding author of the study. The researchers published their findings in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Unmeasured confounding was possible, and the lack of a significant dose-response relationship “could indicate low statistical precision or no causal association,” the researchers noted.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Sundhedsdonationer.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is associated with an increased risk for breast cancer. An analysis by Danish researchers found 14 extra cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women using this type of an intrauterine device (IUD) vs women not using hormonal contraceptives.

METHODOLOGY:

- The investigators used nationwide registries in Denmark to identify all women aged 15-49 years who were first-time initiators of any LNG-IUS between 2000 and 2019.

- They matched 78,595 new users of LNG-IUS 1:1 with women with the same birth year who were not taking hormonal contraceptives.

- Participants were followed through 2022 or until a diagnosis of breast cancer or another malignancy, pregnancy, the initiation of postmenopausal hormone therapy, emigration, or death.

- The investigators used a Cox proportional hazards model to examine the association between the continuous use of LNG-IUS and breast cancer. Their analysis adjusted for variables such as the duration of previous hormonal contraception, fertility drugs, parity, age at first delivery, polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, and education.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with the nonuse of hormonal contraceptives, the continuous use of LNG-IUS was associated with a hazard ratio for breast cancer of 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.5).

- The use of a levonorgestrel IUD for 5 years or less was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.3 (95% CI, 1.1-1.5). With 5-10 years of use, the hazard ratio was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.1-1.7). And with 10-15 years of use, the hazard ratio was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.2-2.6). A test for trend was not significant, however, and “risk did not increase with duration of use,” the study authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Women should be aware that most types of hormonal contraceptive are associated with a small increased risk of breast cancer. This study adds another type of hormonal contraceptive to that list,” Amy Berrington de Gonzalez, DPhil, professor of clinical cancer epidemiology at The Institute of Cancer Research in London, England, said in comments on the research. “That has to be considered with the many benefits from hormonal contraceptives.”

Behaviors such as smoking could have differed between the groups in the study, and it has not been established that LNG-IUS use directly causes an increased risk for breast cancer, said Channa Jayasena, PhD, an endocrinologist at Imperial College London.

“Smoking, alcohol and obesity are much more important risk factors for breast cancer than contraceptive medications,” he said. “My advice for women is that breast cancer risk caused by LNG-IUS is not established but warrants a closer look.”

SOURCE:

Lina Steinrud Mørch, MSc, PhD, with the Danish Cancer Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark, was the corresponding author of the study. The researchers published their findings in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Unmeasured confounding was possible, and the lack of a significant dose-response relationship “could indicate low statistical precision or no causal association,” the researchers noted.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Sundhedsdonationer.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is associated with an increased risk for breast cancer. An analysis by Danish researchers found 14 extra cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women using this type of an intrauterine device (IUD) vs women not using hormonal contraceptives.

METHODOLOGY:

- The investigators used nationwide registries in Denmark to identify all women aged 15-49 years who were first-time initiators of any LNG-IUS between 2000 and 2019.

- They matched 78,595 new users of LNG-IUS 1:1 with women with the same birth year who were not taking hormonal contraceptives.

- Participants were followed through 2022 or until a diagnosis of breast cancer or another malignancy, pregnancy, the initiation of postmenopausal hormone therapy, emigration, or death.

- The investigators used a Cox proportional hazards model to examine the association between the continuous use of LNG-IUS and breast cancer. Their analysis adjusted for variables such as the duration of previous hormonal contraception, fertility drugs, parity, age at first delivery, polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, and education.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with the nonuse of hormonal contraceptives, the continuous use of LNG-IUS was associated with a hazard ratio for breast cancer of 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.5).

- The use of a levonorgestrel IUD for 5 years or less was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.3 (95% CI, 1.1-1.5). With 5-10 years of use, the hazard ratio was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.1-1.7). And with 10-15 years of use, the hazard ratio was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.2-2.6). A test for trend was not significant, however, and “risk did not increase with duration of use,” the study authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Women should be aware that most types of hormonal contraceptive are associated with a small increased risk of breast cancer. This study adds another type of hormonal contraceptive to that list,” Amy Berrington de Gonzalez, DPhil, professor of clinical cancer epidemiology at The Institute of Cancer Research in London, England, said in comments on the research. “That has to be considered with the many benefits from hormonal contraceptives.”

Behaviors such as smoking could have differed between the groups in the study, and it has not been established that LNG-IUS use directly causes an increased risk for breast cancer, said Channa Jayasena, PhD, an endocrinologist at Imperial College London.

“Smoking, alcohol and obesity are much more important risk factors for breast cancer than contraceptive medications,” he said. “My advice for women is that breast cancer risk caused by LNG-IUS is not established but warrants a closer look.”

SOURCE:

Lina Steinrud Mørch, MSc, PhD, with the Danish Cancer Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark, was the corresponding author of the study. The researchers published their findings in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Unmeasured confounding was possible, and the lack of a significant dose-response relationship “could indicate low statistical precision or no causal association,” the researchers noted.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Sundhedsdonationer.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer’s Other Toll: Long-Term Financial Fallout for Survivors

Overall, patients with cancer tend to face higher rates of debt collection, medical collections, and bankruptcies, as well as lower credit scores, according to two new studies presented at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2024.

“These are the first studies to provide numerical evidence of financial toxicity among cancer survivors,” Benjamin C. James, MD, with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts, who worked on both studies, said in a statement. “Previous data on this topic largely relies on subjective survey reviews.”

In one study, researchers used the Massachusetts Cancer Registry to identify 99,175 patients diagnosed with cancer between 2010 and 2019 and matched them with 188,875 control individuals without cancer. Researchers then assessed financial toxicity using Experian credit bureau data for participants.

Overall, patients with cancer faced a range of financial challenges that often lasted years following their diagnosis.

Patients were nearly five times more likely to experience bankruptcy and had average credit scores nearly 80 points lower than control individuals without cancer. The drop in credit scores was more pronounced for survivors of bladder, liver, lung, and colorectal cancer (CRC) and persisted for up to 9.5 years.

For certain cancer types, in particular, “we are looking years after a diagnosis, and we see that the credit score goes down and it never comes back up,” James said.

The other study, which used a sample of 7227 patients with CRC from Massachusetts, identified several factors that correlated with lower credit scores.

Compared with patients who only had surgery, peers who underwent radiation only experienced a 62-point drop in their credit score after their diagnosis, while those who had chemotherapy alone had just over a 14-point drop in their credit score. Among patients who had combination treatments, those who underwent both surgery and radiation experienced a nearly 16-point drop in their credit score and those who had surgery and chemoradiation actually experienced a 2.59 bump, compared with those who had surgery alone.

Financial toxicity was worse for patients younger than 62 years, those identifying as Black or Hispanic individuals, unmarried individuals, those with an annual income below $52,000, and those living in deprived areas.

The studies add to findings from the 2015 North American Thyroid Cancer Survivorship Study, which reported that 50% of thyroid cancer survivors encountered financial toxicity because of their diagnosis.

James said the persistent financial strain of cancer care, even in a state like Massachusetts, which mandates universal healthcare, underscores the need for “broader policy changes and reforms, including reconsidering debt collection practices.”

“Financial security should be a priority in cancer care,” he added.

The studies had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant conflict of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall, patients with cancer tend to face higher rates of debt collection, medical collections, and bankruptcies, as well as lower credit scores, according to two new studies presented at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2024.

“These are the first studies to provide numerical evidence of financial toxicity among cancer survivors,” Benjamin C. James, MD, with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts, who worked on both studies, said in a statement. “Previous data on this topic largely relies on subjective survey reviews.”

In one study, researchers used the Massachusetts Cancer Registry to identify 99,175 patients diagnosed with cancer between 2010 and 2019 and matched them with 188,875 control individuals without cancer. Researchers then assessed financial toxicity using Experian credit bureau data for participants.

Overall, patients with cancer faced a range of financial challenges that often lasted years following their diagnosis.

Patients were nearly five times more likely to experience bankruptcy and had average credit scores nearly 80 points lower than control individuals without cancer. The drop in credit scores was more pronounced for survivors of bladder, liver, lung, and colorectal cancer (CRC) and persisted for up to 9.5 years.

For certain cancer types, in particular, “we are looking years after a diagnosis, and we see that the credit score goes down and it never comes back up,” James said.

The other study, which used a sample of 7227 patients with CRC from Massachusetts, identified several factors that correlated with lower credit scores.

Compared with patients who only had surgery, peers who underwent radiation only experienced a 62-point drop in their credit score after their diagnosis, while those who had chemotherapy alone had just over a 14-point drop in their credit score. Among patients who had combination treatments, those who underwent both surgery and radiation experienced a nearly 16-point drop in their credit score and those who had surgery and chemoradiation actually experienced a 2.59 bump, compared with those who had surgery alone.

Financial toxicity was worse for patients younger than 62 years, those identifying as Black or Hispanic individuals, unmarried individuals, those with an annual income below $52,000, and those living in deprived areas.

The studies add to findings from the 2015 North American Thyroid Cancer Survivorship Study, which reported that 50% of thyroid cancer survivors encountered financial toxicity because of their diagnosis.

James said the persistent financial strain of cancer care, even in a state like Massachusetts, which mandates universal healthcare, underscores the need for “broader policy changes and reforms, including reconsidering debt collection practices.”

“Financial security should be a priority in cancer care,” he added.

The studies had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant conflict of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall, patients with cancer tend to face higher rates of debt collection, medical collections, and bankruptcies, as well as lower credit scores, according to two new studies presented at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2024.

“These are the first studies to provide numerical evidence of financial toxicity among cancer survivors,” Benjamin C. James, MD, with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts, who worked on both studies, said in a statement. “Previous data on this topic largely relies on subjective survey reviews.”

In one study, researchers used the Massachusetts Cancer Registry to identify 99,175 patients diagnosed with cancer between 2010 and 2019 and matched them with 188,875 control individuals without cancer. Researchers then assessed financial toxicity using Experian credit bureau data for participants.

Overall, patients with cancer faced a range of financial challenges that often lasted years following their diagnosis.

Patients were nearly five times more likely to experience bankruptcy and had average credit scores nearly 80 points lower than control individuals without cancer. The drop in credit scores was more pronounced for survivors of bladder, liver, lung, and colorectal cancer (CRC) and persisted for up to 9.5 years.

For certain cancer types, in particular, “we are looking years after a diagnosis, and we see that the credit score goes down and it never comes back up,” James said.

The other study, which used a sample of 7227 patients with CRC from Massachusetts, identified several factors that correlated with lower credit scores.

Compared with patients who only had surgery, peers who underwent radiation only experienced a 62-point drop in their credit score after their diagnosis, while those who had chemotherapy alone had just over a 14-point drop in their credit score. Among patients who had combination treatments, those who underwent both surgery and radiation experienced a nearly 16-point drop in their credit score and those who had surgery and chemoradiation actually experienced a 2.59 bump, compared with those who had surgery alone.

Financial toxicity was worse for patients younger than 62 years, those identifying as Black or Hispanic individuals, unmarried individuals, those with an annual income below $52,000, and those living in deprived areas.

The studies add to findings from the 2015 North American Thyroid Cancer Survivorship Study, which reported that 50% of thyroid cancer survivors encountered financial toxicity because of their diagnosis.

James said the persistent financial strain of cancer care, even in a state like Massachusetts, which mandates universal healthcare, underscores the need for “broader policy changes and reforms, including reconsidering debt collection practices.”

“Financial security should be a priority in cancer care,” he added.

The studies had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant conflict of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACSCS 2024

Mortality Rates From Early-Onset CRC Have Risen Considerably Over Last 2 Decades

PHILADELPHIA — according to a new analysis of the two largest US mortality databases.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center of Health Statistics (NCHS) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) databases provide yet more evidence of the increasing prevalence of EO-CRC, which is defined as a diagnosis of CRC in patients younger than age 50 years.

Furthermore, the researchers reported that increased mortality occurred across all patients included in the study (aged 20-54) regardless of tumor stage at diagnosis.

These findings “prompt tailoring further efforts toward raising awareness of colorectal cancer symptoms and keeping a low clinical suspicion in younger patients presenting with anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding, or change in bowel habits,” Yazan Abboud, MD, internal medicine PGY-3, assistant chief resident, and chair of resident research at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said in an interview.

Abboud presented the findings at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Analyzing NCHS and SEER

Rising rates of EO-CRC had prompted US medical societies to recommend reducing the screening age to 45 years. The US Preventive Services Task Force officially lowered it to this age in 2021. This shift is supported by real-world evidence, which shows that earlier screening leads to a significantly reduced risk for colorectal cancer. However, because colorectal cancer cases are decreasing overall in older adults, there is considerable interest in discovering why young adults are experiencing a paradoxical uptick in EO-CRC, and what impact this is having on associated mortality.

Abboud and colleagues collected age-adjusted mortality rates for EO-CRC between 2000 and 2022 from the NCHS database. In addition, stage-specific incidence-based mortality rates between 2004-2020 were obtained from the SEER 22 database. The NCHS database covers approximately 100% of the US population, whereas the SEER 22 database, which is included within the NCHS, covers 42%.

The researchers divided patients into two cohorts based on age (20-44 years and 45-54 years) and tumor stage at diagnosis (early stage and late stage), and compared the annual percentage change (APC) and the average APC between the two groups. They also assessed trends for the entire cohort of patients aged 20-54 years.

In the NCHS database, there were 147,026 deaths in total across all ages studied resulting from EO-CRC, of which 27% (39,746) occurred in those 20-44 years of age. Although associated mortality rates decreased between 2000-2005 in all ages studied (APC, –1.56), they increased from 2005-2022 (APC, 0.87).

In the cohort aged 45-54 years, mortality decreased between 2000-2005 and increased thereafter, whereas in the cohort aged 20-44 years mortality increased steadily for the entire follow-up duration of 2000 to 2022 (APC, 0.93). A comparison of the age cohorts confirmed that those aged 20-44 years had a greater increase in mortality (average APC, 0.85; P < .001).

In the SEER 22 database, there were 4652 deaths in those with early-stage tumors across all age groups studied (average APC, 12.17). Mortality increased in patients aged 45-54 years (average APC, 11.52) with early-stage tumors, but there were insufficient numbers in those aged 20-44 years to determine this outcome.

There were 42,120 deaths in those with late-stage tumors across all age groups (average APC, 10.05) in the SEER 22 database. And increased mortality was observed in those with late-stage tumors in both age cohorts: 45-54 years (average APC, 9.58) and 20-44 years (average APC, 11.06).

“When evaluating the SEER database and stratifying the tumors by stage at diagnosis, we demonstrated increasing mortality of early-onset colorectal cancer in both early- and late-stage tumors on average over the study period,” Abboud said.

Identifying At-Risk Patients

In a comment, David A. Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia School of Medicine in Norfolk, said the findings speak to the need for evidence-based means of identifying younger individuals at a higher risk of EO-CRC.

“I suspect many of younger patients with CRC had their cancer detected when it was more advanced due to delayed presentation and diagnostic testing,” said Johnson, who was not involved in the study.

But it would be interesting to evaluate if the cancers in the cohort aged 20-44 years were more aggressive biologically or if these patients were dismissive of early signs or symptoms, he said.

Younger patients may dismiss “alarm” features that indicate CRC testing, said Johnson. “In particular, overt bleeding and iron deficiency need a focused evaluation in these younger cohorts.”

“Future research is needed to investigate the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in younger patients with early-stage colorectal cancer and evaluate patients’ outcomes,” Abboud added.

The study had no specific funding. Abboud reported no relevant financial relationships. Johnson reported serving as an adviser to ISOTHRIVE. He is also on the Medscape Gastroenterology editorial board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PHILADELPHIA — according to a new analysis of the two largest US mortality databases.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center of Health Statistics (NCHS) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) databases provide yet more evidence of the increasing prevalence of EO-CRC, which is defined as a diagnosis of CRC in patients younger than age 50 years.

Furthermore, the researchers reported that increased mortality occurred across all patients included in the study (aged 20-54) regardless of tumor stage at diagnosis.

These findings “prompt tailoring further efforts toward raising awareness of colorectal cancer symptoms and keeping a low clinical suspicion in younger patients presenting with anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding, or change in bowel habits,” Yazan Abboud, MD, internal medicine PGY-3, assistant chief resident, and chair of resident research at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said in an interview.

Abboud presented the findings at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Analyzing NCHS and SEER

Rising rates of EO-CRC had prompted US medical societies to recommend reducing the screening age to 45 years. The US Preventive Services Task Force officially lowered it to this age in 2021. This shift is supported by real-world evidence, which shows that earlier screening leads to a significantly reduced risk for colorectal cancer. However, because colorectal cancer cases are decreasing overall in older adults, there is considerable interest in discovering why young adults are experiencing a paradoxical uptick in EO-CRC, and what impact this is having on associated mortality.

Abboud and colleagues collected age-adjusted mortality rates for EO-CRC between 2000 and 2022 from the NCHS database. In addition, stage-specific incidence-based mortality rates between 2004-2020 were obtained from the SEER 22 database. The NCHS database covers approximately 100% of the US population, whereas the SEER 22 database, which is included within the NCHS, covers 42%.

The researchers divided patients into two cohorts based on age (20-44 years and 45-54 years) and tumor stage at diagnosis (early stage and late stage), and compared the annual percentage change (APC) and the average APC between the two groups. They also assessed trends for the entire cohort of patients aged 20-54 years.

In the NCHS database, there were 147,026 deaths in total across all ages studied resulting from EO-CRC, of which 27% (39,746) occurred in those 20-44 years of age. Although associated mortality rates decreased between 2000-2005 in all ages studied (APC, –1.56), they increased from 2005-2022 (APC, 0.87).

In the cohort aged 45-54 years, mortality decreased between 2000-2005 and increased thereafter, whereas in the cohort aged 20-44 years mortality increased steadily for the entire follow-up duration of 2000 to 2022 (APC, 0.93). A comparison of the age cohorts confirmed that those aged 20-44 years had a greater increase in mortality (average APC, 0.85; P < .001).

In the SEER 22 database, there were 4652 deaths in those with early-stage tumors across all age groups studied (average APC, 12.17). Mortality increased in patients aged 45-54 years (average APC, 11.52) with early-stage tumors, but there were insufficient numbers in those aged 20-44 years to determine this outcome.

There were 42,120 deaths in those with late-stage tumors across all age groups (average APC, 10.05) in the SEER 22 database. And increased mortality was observed in those with late-stage tumors in both age cohorts: 45-54 years (average APC, 9.58) and 20-44 years (average APC, 11.06).

“When evaluating the SEER database and stratifying the tumors by stage at diagnosis, we demonstrated increasing mortality of early-onset colorectal cancer in both early- and late-stage tumors on average over the study period,” Abboud said.

Identifying At-Risk Patients

In a comment, David A. Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia School of Medicine in Norfolk, said the findings speak to the need for evidence-based means of identifying younger individuals at a higher risk of EO-CRC.

“I suspect many of younger patients with CRC had their cancer detected when it was more advanced due to delayed presentation and diagnostic testing,” said Johnson, who was not involved in the study.

But it would be interesting to evaluate if the cancers in the cohort aged 20-44 years were more aggressive biologically or if these patients were dismissive of early signs or symptoms, he said.

Younger patients may dismiss “alarm” features that indicate CRC testing, said Johnson. “In particular, overt bleeding and iron deficiency need a focused evaluation in these younger cohorts.”

“Future research is needed to investigate the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in younger patients with early-stage colorectal cancer and evaluate patients’ outcomes,” Abboud added.

The study had no specific funding. Abboud reported no relevant financial relationships. Johnson reported serving as an adviser to ISOTHRIVE. He is also on the Medscape Gastroenterology editorial board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PHILADELPHIA — according to a new analysis of the two largest US mortality databases.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center of Health Statistics (NCHS) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) databases provide yet more evidence of the increasing prevalence of EO-CRC, which is defined as a diagnosis of CRC in patients younger than age 50 years.

Furthermore, the researchers reported that increased mortality occurred across all patients included in the study (aged 20-54) regardless of tumor stage at diagnosis.

These findings “prompt tailoring further efforts toward raising awareness of colorectal cancer symptoms and keeping a low clinical suspicion in younger patients presenting with anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding, or change in bowel habits,” Yazan Abboud, MD, internal medicine PGY-3, assistant chief resident, and chair of resident research at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said in an interview.

Abboud presented the findings at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Analyzing NCHS and SEER

Rising rates of EO-CRC had prompted US medical societies to recommend reducing the screening age to 45 years. The US Preventive Services Task Force officially lowered it to this age in 2021. This shift is supported by real-world evidence, which shows that earlier screening leads to a significantly reduced risk for colorectal cancer. However, because colorectal cancer cases are decreasing overall in older adults, there is considerable interest in discovering why young adults are experiencing a paradoxical uptick in EO-CRC, and what impact this is having on associated mortality.

Abboud and colleagues collected age-adjusted mortality rates for EO-CRC between 2000 and 2022 from the NCHS database. In addition, stage-specific incidence-based mortality rates between 2004-2020 were obtained from the SEER 22 database. The NCHS database covers approximately 100% of the US population, whereas the SEER 22 database, which is included within the NCHS, covers 42%.

The researchers divided patients into two cohorts based on age (20-44 years and 45-54 years) and tumor stage at diagnosis (early stage and late stage), and compared the annual percentage change (APC) and the average APC between the two groups. They also assessed trends for the entire cohort of patients aged 20-54 years.

In the NCHS database, there were 147,026 deaths in total across all ages studied resulting from EO-CRC, of which 27% (39,746) occurred in those 20-44 years of age. Although associated mortality rates decreased between 2000-2005 in all ages studied (APC, –1.56), they increased from 2005-2022 (APC, 0.87).

In the cohort aged 45-54 years, mortality decreased between 2000-2005 and increased thereafter, whereas in the cohort aged 20-44 years mortality increased steadily for the entire follow-up duration of 2000 to 2022 (APC, 0.93). A comparison of the age cohorts confirmed that those aged 20-44 years had a greater increase in mortality (average APC, 0.85; P < .001).

In the SEER 22 database, there were 4652 deaths in those with early-stage tumors across all age groups studied (average APC, 12.17). Mortality increased in patients aged 45-54 years (average APC, 11.52) with early-stage tumors, but there were insufficient numbers in those aged 20-44 years to determine this outcome.

There were 42,120 deaths in those with late-stage tumors across all age groups (average APC, 10.05) in the SEER 22 database. And increased mortality was observed in those with late-stage tumors in both age cohorts: 45-54 years (average APC, 9.58) and 20-44 years (average APC, 11.06).

“When evaluating the SEER database and stratifying the tumors by stage at diagnosis, we demonstrated increasing mortality of early-onset colorectal cancer in both early- and late-stage tumors on average over the study period,” Abboud said.

Identifying At-Risk Patients

In a comment, David A. Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia School of Medicine in Norfolk, said the findings speak to the need for evidence-based means of identifying younger individuals at a higher risk of EO-CRC.

“I suspect many of younger patients with CRC had their cancer detected when it was more advanced due to delayed presentation and diagnostic testing,” said Johnson, who was not involved in the study.

But it would be interesting to evaluate if the cancers in the cohort aged 20-44 years were more aggressive biologically or if these patients were dismissive of early signs or symptoms, he said.

Younger patients may dismiss “alarm” features that indicate CRC testing, said Johnson. “In particular, overt bleeding and iron deficiency need a focused evaluation in these younger cohorts.”

“Future research is needed to investigate the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in younger patients with early-stage colorectal cancer and evaluate patients’ outcomes,” Abboud added.

The study had no specific funding. Abboud reported no relevant financial relationships. Johnson reported serving as an adviser to ISOTHRIVE. He is also on the Medscape Gastroenterology editorial board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACG 2024

Asteraceae Dermatitis: Everyday Plants With Allergenic Potential

The Asteraceae (formerly Compositae) family of plants is derived from the ancient Greek word aster, meaning “star,” referring to the starlike arrangement of flower petals around a central disc known as a capitulum. What initially appears as a single flower is actually a composite of several smaller flowers, hence the former name Compositae.1 Well-known members of the Asteraceae family include ornamental annuals (eg, sunflowers, marigolds, cosmos), herbaceous perennials (eg, chrysanthemums, dandelions), vegetables (eg, lettuce, chicory, artichokes), herbs (eg, chamomile, tarragon), and weeds (eg, ragweed, horseweed, capeweed)(Figure 1).2

There are more than 25,000 species of Asteraceae plants that thrive in a wide range of climates worldwide. Cases of Asteraceae-induced skin reactions have been reported in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.3 Members of the Asteraceae family are ubiquitous in gardens, along roadsides, and in the wilderness. Occupational exposure commonly affects gardeners, florists, farmers, and forestry workers through either direct contact with plants or via airborne pollen. Furthermore, plants of the Asteraceae family are used in various products, including pediculicides (eg, insect repellents), cosmetics (eg, eye creams, body washes), and food products (eg, cooking oils, sweetening agents, coffee substitutes, herbal teas).4-6 These plants have substantial allergic potential, resulting in numerous cutaneous reactions.

Allergic Potential

Asteraceae plants can elicit both immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs); for instance, exposure to ragweed pollen may cause an IgE-mediated type 1 HSR manifesting as allergic rhinitis or a type IV HSR manifesting as airborne allergic contact dermatitis.7,8 The main contact allergens present in Asteraceae plants are sesquiterpene lactones, which are found in the leaves, stems, flowers, and pollen.9-11 Sesquiterpene lactones consist of an α-methyl group attached to a lactone ring combined with a sesquiterpene.12 Patch testing can be used to diagnose Asteraceae allergy; however, the results are not consistently reliable because there is no perfect screening allergen. Patch test preparations commonly used to detect Asteraceae allergy include Compositae mix (consisting of Anthemis nobilis extract, Chamomilla recutita extract, Achillea millefolium extract, Tanacetum vulgare extract, Arnica montana extract, and parthenolide) and sesquiterpene lactone mix (consisting of alantolactone, dehydrocostus lactone, and costunolide). In North America, the prevalence of positive patch tests to Compositae mix and sesquiterpene lactone mix is approximately 2% and 0.5%, respectively.13 When patch testing is performed, both Compositae mix and sesquiterpene lactone mix should be utilized to minimize the risk of missing Asteraceae allergy, as sesquiterpene lactone mix alone does not detect all Compositae-sensitized patients. Additionally, it may be necessary to test supplemental Asteraceae allergens, including preparations from specific plants to which the patient has been exposed. Exposure to Asteraceae-containing cosmetic products may lead to dermatitis, though this is highly dependent on the particular plant species involved. For instance, the prevalence of sensitization is high in arnica (tincture) and elecampane but low with more commonly used species such as German chamomile.14

Cutaneous Manifestations