User login

Bone-bashing effects of air pollution becoming clearer

We have long recognized that our environment has a significant impact on our general health. Air pollution is known to contribute to respiratory conditions, poor cardiovascular outcomes, and certain kinds of cancer.

It’s increasingly important to identify factors that might contribute to suboptimal bone density and associated fracture risk in the population as a whole, and particularly in older adults. Aging is associated with a higher risk for osteoporosis and fractures, with their attendant morbidity, but individuals differ in their extent of bone loss and risk for fractures.

Known factors affecting bone health include genetics, age, sex, nutrition, physical activity, and hormonal factors. Certain medications, diseases, and lifestyle choices – such as smoking and alcohol intake – can also have deleterious effects on bone.

More recently, researchers have started examining the impact of air pollution on bone health.

As we know, the degree of pollution varies greatly from one region to another and can potentially significantly affect life in many parts of the world. In fact, the World Health Organization indicates that 99% of the world’s population breathes air exceeding the WHO guideline limits for pollutants.

Air pollutants include particulate matter (PM) as well as gases, such as nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, ammonia, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone, and certain volatile organic compounds. Particulate pollutants include a variety of substances produced from mostly human activities (such as vehicle emissions, biofuel combustion, mining, agriculture, and manufacturing, and also forest fires). They are classified not by their composition, but by their size (for example, PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 indicate PM with a diameter < 1.0, 2.5, and 10 microns, respectively). The finer the particle, the more likely it is to cross into the systemic circulation from the respiratory tract, with the potential to induce oxidative, inflammatory, and other changes in the body.

Many studies report that air pollution is a risk factor for osteoporosis. Some have found associations of lower bone density, osteoporosis, and fracture risk with higher concentrations of PM1.0, PM2.5, or PM10, even after controlling for other factors that could affect bone health. Some researchers have reported that although they didn’t find a significant association between PM and bone health, they did find an association between distance from the freeway and bone health – thus, exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and black carbon from vehicle emissions needs to be studied as a contributor to fracture risk.

Importantly, a prospective, observational study from the Women’s Health Initiative (which included more than 9,000 ethnically diverse women from three sites in the United States) reported a significant negative impact of PM10, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide over 1, 3, and 5 years on bone density at multiple sites, and particularly at the lumbar spine, in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses after controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors. This study reported that nitrogen dioxide exposure may be a key determinant of bone density at the lumbar spine and in the whole body. Similarly, other studies have reported associations between atmospheric nitrogen dioxide or sulfur dioxide and risk for osteoporotic fractures.

Why the impact on bones?

The potential negative impact of pollution on bone has been attributed to many factors. PM induces systemic inflammation and an increase in cytokines that stimulate bone cells (osteoclasts) that cause bone loss. Other pollutants (gases and metal compounds) can cause oxidative damage to bone cells, whereas others act as endocrine disrupters and affect the functioning of these cells.

Pollution might also affect the synthesis and metabolism of vitamin D, which is necessary for absorption of calcium from the gut. High rates of pollution can reduce the amount of ultraviolet radiation reaching the earth which is important because certain wavelengths of ultraviolet radiation are necessary for vitamin D synthesis in our skin. Reduced vitamin D synthesis in skin can lead to poorly mineralized bone unless there is sufficient intake of vitamin D in diet or as supplements. Also, the conversion of vitamin D to its active form happens in the kidneys, and PM can be harmful to renal function. PM is also believed to cause increased breakdown of vitamin D into its inactive form.

Conversely, some studies have reported no association between pollution and bone density or osteoporosis risk, and two meta-analyses indicated that the association between the two is inconsistent. Some factors explaining variances in results include the number of individuals included in the study (larger studies are generally considered to be more reproducible), the fact that most studies are cross-sectional and not prospective, many do not control for other factors that might be deleterious to bone, and prediction models for the extent of PM or other exposure may not be completely accurate.

However, another recent meta-analysis reported an increased risk for lower total-body bone density and hip fracture after exposure to air pollution, particularly PM2.5 and nitrogen dioxide, but not to PM10, nitric oxide, or ozone. More studies are needed to confirm, or refute, the association between air pollution and impaired bone health. But accumulating evidence suggests that air pollution very likely has a deleterious effect on bone.

When feasible, it’s important to avoid living or working in areas with poor air quality and high pollution rates. However, this isn’t always possible based on one’s occupation, geography, circumstances, or economic status. Therefore, attention to a cleaner environment is critical at both the individual and the macro level.

As an example of the latter, the city of London extended its ultralow emission zone (ULEZ) farther out of the city in October 2021, and a further expansion is planned to include all of the city’s boroughs in August 2023.

We can do our bit by driving less and walking, biking, or using public transportation more often. We can also turn off the car engine when it’s not running, maintain our vehicles, switch to electric or hand-powered yard equipment, and not burn household garbage and limit backyard fires. We can also switch from gas to solar energy or wind, use efficient appliances and heating, and avoid unnecessary energy use. And we can choose sustainable products when possible.

For optimal bone health, we should remind patients to eat a healthy diet with the requisite amount of protein, calcium, and vitamin D. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may be necessary for people whose intake of dairy and dairy products is low. Other important strategies to optimize bone health include engaging in healthy physical activity; avoiding smoking or excessive alcohol intake; and treating underlying gastrointestinal, endocrine, or other conditions that can reduce bone density.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is the chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology, Mass General for Children; the associate director of the Harvard Catalyst Translation and Clinical Research Center; and the director of the Pediatric Endocrine-Sports Endocrine-Neuroendocrine Lab, Mass General Hospital, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We have long recognized that our environment has a significant impact on our general health. Air pollution is known to contribute to respiratory conditions, poor cardiovascular outcomes, and certain kinds of cancer.

It’s increasingly important to identify factors that might contribute to suboptimal bone density and associated fracture risk in the population as a whole, and particularly in older adults. Aging is associated with a higher risk for osteoporosis and fractures, with their attendant morbidity, but individuals differ in their extent of bone loss and risk for fractures.

Known factors affecting bone health include genetics, age, sex, nutrition, physical activity, and hormonal factors. Certain medications, diseases, and lifestyle choices – such as smoking and alcohol intake – can also have deleterious effects on bone.

More recently, researchers have started examining the impact of air pollution on bone health.

As we know, the degree of pollution varies greatly from one region to another and can potentially significantly affect life in many parts of the world. In fact, the World Health Organization indicates that 99% of the world’s population breathes air exceeding the WHO guideline limits for pollutants.

Air pollutants include particulate matter (PM) as well as gases, such as nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, ammonia, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone, and certain volatile organic compounds. Particulate pollutants include a variety of substances produced from mostly human activities (such as vehicle emissions, biofuel combustion, mining, agriculture, and manufacturing, and also forest fires). They are classified not by their composition, but by their size (for example, PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 indicate PM with a diameter < 1.0, 2.5, and 10 microns, respectively). The finer the particle, the more likely it is to cross into the systemic circulation from the respiratory tract, with the potential to induce oxidative, inflammatory, and other changes in the body.

Many studies report that air pollution is a risk factor for osteoporosis. Some have found associations of lower bone density, osteoporosis, and fracture risk with higher concentrations of PM1.0, PM2.5, or PM10, even after controlling for other factors that could affect bone health. Some researchers have reported that although they didn’t find a significant association between PM and bone health, they did find an association between distance from the freeway and bone health – thus, exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and black carbon from vehicle emissions needs to be studied as a contributor to fracture risk.

Importantly, a prospective, observational study from the Women’s Health Initiative (which included more than 9,000 ethnically diverse women from three sites in the United States) reported a significant negative impact of PM10, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide over 1, 3, and 5 years on bone density at multiple sites, and particularly at the lumbar spine, in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses after controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors. This study reported that nitrogen dioxide exposure may be a key determinant of bone density at the lumbar spine and in the whole body. Similarly, other studies have reported associations between atmospheric nitrogen dioxide or sulfur dioxide and risk for osteoporotic fractures.

Why the impact on bones?

The potential negative impact of pollution on bone has been attributed to many factors. PM induces systemic inflammation and an increase in cytokines that stimulate bone cells (osteoclasts) that cause bone loss. Other pollutants (gases and metal compounds) can cause oxidative damage to bone cells, whereas others act as endocrine disrupters and affect the functioning of these cells.

Pollution might also affect the synthesis and metabolism of vitamin D, which is necessary for absorption of calcium from the gut. High rates of pollution can reduce the amount of ultraviolet radiation reaching the earth which is important because certain wavelengths of ultraviolet radiation are necessary for vitamin D synthesis in our skin. Reduced vitamin D synthesis in skin can lead to poorly mineralized bone unless there is sufficient intake of vitamin D in diet or as supplements. Also, the conversion of vitamin D to its active form happens in the kidneys, and PM can be harmful to renal function. PM is also believed to cause increased breakdown of vitamin D into its inactive form.

Conversely, some studies have reported no association between pollution and bone density or osteoporosis risk, and two meta-analyses indicated that the association between the two is inconsistent. Some factors explaining variances in results include the number of individuals included in the study (larger studies are generally considered to be more reproducible), the fact that most studies are cross-sectional and not prospective, many do not control for other factors that might be deleterious to bone, and prediction models for the extent of PM or other exposure may not be completely accurate.

However, another recent meta-analysis reported an increased risk for lower total-body bone density and hip fracture after exposure to air pollution, particularly PM2.5 and nitrogen dioxide, but not to PM10, nitric oxide, or ozone. More studies are needed to confirm, or refute, the association between air pollution and impaired bone health. But accumulating evidence suggests that air pollution very likely has a deleterious effect on bone.

When feasible, it’s important to avoid living or working in areas with poor air quality and high pollution rates. However, this isn’t always possible based on one’s occupation, geography, circumstances, or economic status. Therefore, attention to a cleaner environment is critical at both the individual and the macro level.

As an example of the latter, the city of London extended its ultralow emission zone (ULEZ) farther out of the city in October 2021, and a further expansion is planned to include all of the city’s boroughs in August 2023.

We can do our bit by driving less and walking, biking, or using public transportation more often. We can also turn off the car engine when it’s not running, maintain our vehicles, switch to electric or hand-powered yard equipment, and not burn household garbage and limit backyard fires. We can also switch from gas to solar energy or wind, use efficient appliances and heating, and avoid unnecessary energy use. And we can choose sustainable products when possible.

For optimal bone health, we should remind patients to eat a healthy diet with the requisite amount of protein, calcium, and vitamin D. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may be necessary for people whose intake of dairy and dairy products is low. Other important strategies to optimize bone health include engaging in healthy physical activity; avoiding smoking or excessive alcohol intake; and treating underlying gastrointestinal, endocrine, or other conditions that can reduce bone density.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is the chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology, Mass General for Children; the associate director of the Harvard Catalyst Translation and Clinical Research Center; and the director of the Pediatric Endocrine-Sports Endocrine-Neuroendocrine Lab, Mass General Hospital, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We have long recognized that our environment has a significant impact on our general health. Air pollution is known to contribute to respiratory conditions, poor cardiovascular outcomes, and certain kinds of cancer.

It’s increasingly important to identify factors that might contribute to suboptimal bone density and associated fracture risk in the population as a whole, and particularly in older adults. Aging is associated with a higher risk for osteoporosis and fractures, with their attendant morbidity, but individuals differ in their extent of bone loss and risk for fractures.

Known factors affecting bone health include genetics, age, sex, nutrition, physical activity, and hormonal factors. Certain medications, diseases, and lifestyle choices – such as smoking and alcohol intake – can also have deleterious effects on bone.

More recently, researchers have started examining the impact of air pollution on bone health.

As we know, the degree of pollution varies greatly from one region to another and can potentially significantly affect life in many parts of the world. In fact, the World Health Organization indicates that 99% of the world’s population breathes air exceeding the WHO guideline limits for pollutants.

Air pollutants include particulate matter (PM) as well as gases, such as nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, ammonia, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone, and certain volatile organic compounds. Particulate pollutants include a variety of substances produced from mostly human activities (such as vehicle emissions, biofuel combustion, mining, agriculture, and manufacturing, and also forest fires). They are classified not by their composition, but by their size (for example, PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 indicate PM with a diameter < 1.0, 2.5, and 10 microns, respectively). The finer the particle, the more likely it is to cross into the systemic circulation from the respiratory tract, with the potential to induce oxidative, inflammatory, and other changes in the body.

Many studies report that air pollution is a risk factor for osteoporosis. Some have found associations of lower bone density, osteoporosis, and fracture risk with higher concentrations of PM1.0, PM2.5, or PM10, even after controlling for other factors that could affect bone health. Some researchers have reported that although they didn’t find a significant association between PM and bone health, they did find an association between distance from the freeway and bone health – thus, exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and black carbon from vehicle emissions needs to be studied as a contributor to fracture risk.

Importantly, a prospective, observational study from the Women’s Health Initiative (which included more than 9,000 ethnically diverse women from three sites in the United States) reported a significant negative impact of PM10, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide over 1, 3, and 5 years on bone density at multiple sites, and particularly at the lumbar spine, in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses after controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors. This study reported that nitrogen dioxide exposure may be a key determinant of bone density at the lumbar spine and in the whole body. Similarly, other studies have reported associations between atmospheric nitrogen dioxide or sulfur dioxide and risk for osteoporotic fractures.

Why the impact on bones?

The potential negative impact of pollution on bone has been attributed to many factors. PM induces systemic inflammation and an increase in cytokines that stimulate bone cells (osteoclasts) that cause bone loss. Other pollutants (gases and metal compounds) can cause oxidative damage to bone cells, whereas others act as endocrine disrupters and affect the functioning of these cells.

Pollution might also affect the synthesis and metabolism of vitamin D, which is necessary for absorption of calcium from the gut. High rates of pollution can reduce the amount of ultraviolet radiation reaching the earth which is important because certain wavelengths of ultraviolet radiation are necessary for vitamin D synthesis in our skin. Reduced vitamin D synthesis in skin can lead to poorly mineralized bone unless there is sufficient intake of vitamin D in diet or as supplements. Also, the conversion of vitamin D to its active form happens in the kidneys, and PM can be harmful to renal function. PM is also believed to cause increased breakdown of vitamin D into its inactive form.

Conversely, some studies have reported no association between pollution and bone density or osteoporosis risk, and two meta-analyses indicated that the association between the two is inconsistent. Some factors explaining variances in results include the number of individuals included in the study (larger studies are generally considered to be more reproducible), the fact that most studies are cross-sectional and not prospective, many do not control for other factors that might be deleterious to bone, and prediction models for the extent of PM or other exposure may not be completely accurate.

However, another recent meta-analysis reported an increased risk for lower total-body bone density and hip fracture after exposure to air pollution, particularly PM2.5 and nitrogen dioxide, but not to PM10, nitric oxide, or ozone. More studies are needed to confirm, or refute, the association between air pollution and impaired bone health. But accumulating evidence suggests that air pollution very likely has a deleterious effect on bone.

When feasible, it’s important to avoid living or working in areas with poor air quality and high pollution rates. However, this isn’t always possible based on one’s occupation, geography, circumstances, or economic status. Therefore, attention to a cleaner environment is critical at both the individual and the macro level.

As an example of the latter, the city of London extended its ultralow emission zone (ULEZ) farther out of the city in October 2021, and a further expansion is planned to include all of the city’s boroughs in August 2023.

We can do our bit by driving less and walking, biking, or using public transportation more often. We can also turn off the car engine when it’s not running, maintain our vehicles, switch to electric or hand-powered yard equipment, and not burn household garbage and limit backyard fires. We can also switch from gas to solar energy or wind, use efficient appliances and heating, and avoid unnecessary energy use. And we can choose sustainable products when possible.

For optimal bone health, we should remind patients to eat a healthy diet with the requisite amount of protein, calcium, and vitamin D. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may be necessary for people whose intake of dairy and dairy products is low. Other important strategies to optimize bone health include engaging in healthy physical activity; avoiding smoking or excessive alcohol intake; and treating underlying gastrointestinal, endocrine, or other conditions that can reduce bone density.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is the chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology, Mass General for Children; the associate director of the Harvard Catalyst Translation and Clinical Research Center; and the director of the Pediatric Endocrine-Sports Endocrine-Neuroendocrine Lab, Mass General Hospital, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

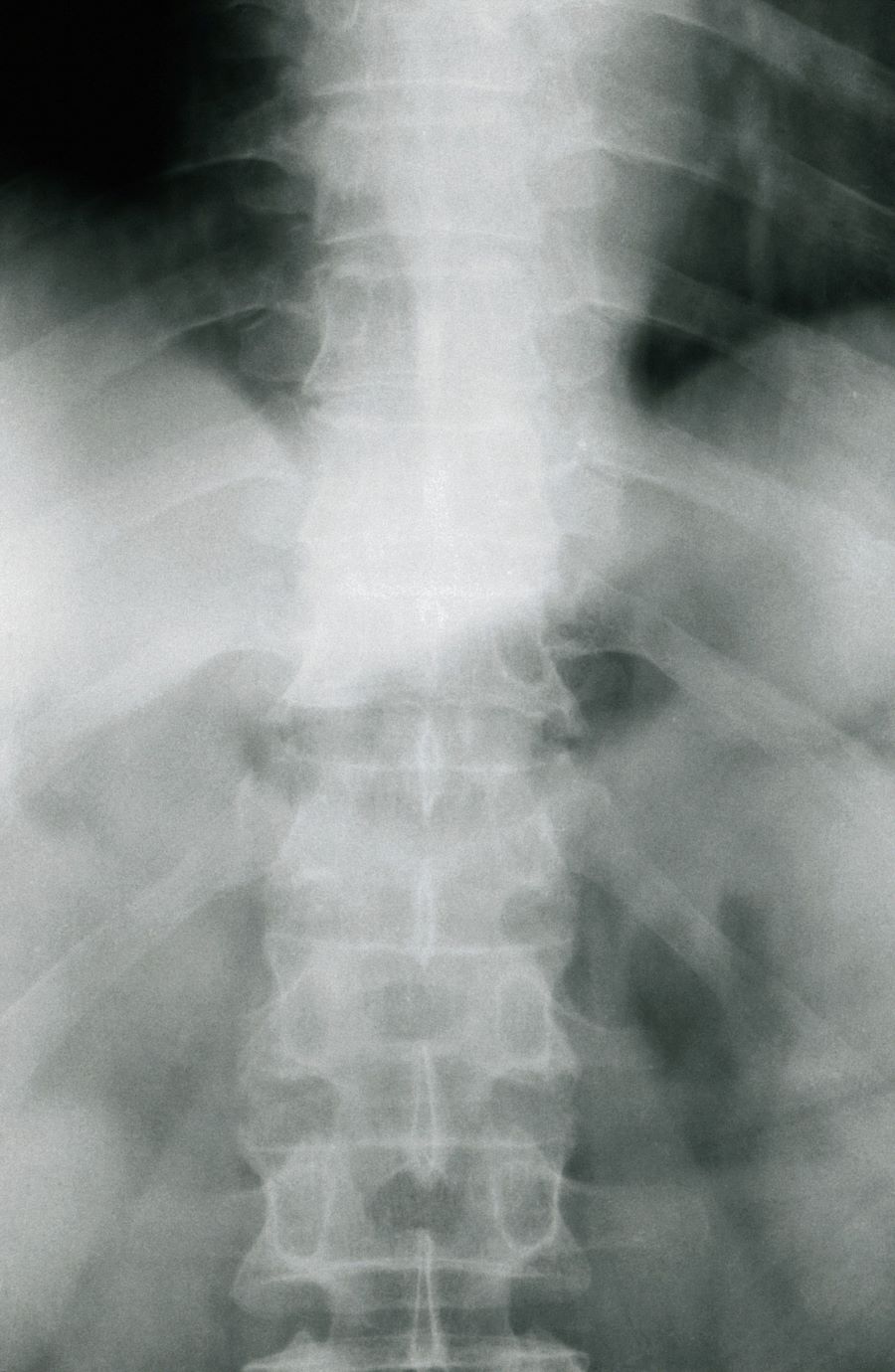

Moderate to severe back pain

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of axial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Psoriasis is a complex, chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease that is associated with significant morbidity, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality. Approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States have psoriasis; worldwide, approximately 2%-3% of the population is affected. Patients with psoriasis frequently have comorbidities; PsA, an inflammatory, seronegative musculoskeletal disease, is among the most common. It is estimated that 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis develop PsA.

PsA is a heterogeneous disease. Patients may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Men and women are equally affected by PsA, which typically develops when patients are age 30-50 years. Like psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

PsA is a potentially erosive disease. Structural damage and functional impairment occurs within 2 years of initial assessment in approximately 50% of patients; as the disease progresses, patients may experience irreversible joint damage and disability. Axial involvement occurs in 25%-70% of patients with PsA; exclusive axial involvement is uncommon, occurring in 5% of patients. Common symptoms of axial PsA include inflammatory back pain (eg, pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest, morning stiffness lasting longer than 30 minutes). Some patients with axial involvement may be asymptomatic. If untreated, cervical spinal mobility and lateral flexion significantly decline within 5 years in patients with axial PsA. In addition, sacroiliitis worsens over time; 37% and 52% of patients develop grade 2 or higher sacroiliitis within 5 and 10 years, respectively. This highlights the importance of early identification and treatment of patients with axial PsA.

The diagnosis of axial PsA is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosis). PsA can be differentiated from ankylosing spondylitis by the asymmetric and frequently unilateral presentation of sacroiliitis and syndesmophytes, which frequently presents as nonmarginal, bulky, asymmetric, and discontinuous skipping vertebral levels.

Plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI are all useful tools for evaluating patients with PsA. MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography is for detecting early joint inflammation and damage as well as axial changes, including sacroiliitis; however, they are not required for a diagnosis of PsA.

The treatment of axial PsA is based on international guidelines developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society–European League Against Rheumatism. Treatment focuses on minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; enhancing functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Medications for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; however, long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or if erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity is observed, guidelines recommend initiation of a TNF inhibitor. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective.

If symptoms of axial PsA are not controlled by NSAIDs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are recommended. However, interleukin 17A inhibitors may be used in preference to TNF inhibitors in patients with significant skin involvement. In the United States, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, and infliximab are recommended over etanercept for patients with axial SpA in the presence of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or recurrent uveitis (although there is no evidence for golimumab) because etanercept has contradictory results for uveitis and has not been shown to have efficacy in IBD.

If patients fail to respond to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic is recommended by US guidelines. A Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered for patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors.

Nonpharmacologic therapies (ie, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of axial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Psoriasis is a complex, chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease that is associated with significant morbidity, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality. Approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States have psoriasis; worldwide, approximately 2%-3% of the population is affected. Patients with psoriasis frequently have comorbidities; PsA, an inflammatory, seronegative musculoskeletal disease, is among the most common. It is estimated that 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis develop PsA.

PsA is a heterogeneous disease. Patients may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Men and women are equally affected by PsA, which typically develops when patients are age 30-50 years. Like psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

PsA is a potentially erosive disease. Structural damage and functional impairment occurs within 2 years of initial assessment in approximately 50% of patients; as the disease progresses, patients may experience irreversible joint damage and disability. Axial involvement occurs in 25%-70% of patients with PsA; exclusive axial involvement is uncommon, occurring in 5% of patients. Common symptoms of axial PsA include inflammatory back pain (eg, pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest, morning stiffness lasting longer than 30 minutes). Some patients with axial involvement may be asymptomatic. If untreated, cervical spinal mobility and lateral flexion significantly decline within 5 years in patients with axial PsA. In addition, sacroiliitis worsens over time; 37% and 52% of patients develop grade 2 or higher sacroiliitis within 5 and 10 years, respectively. This highlights the importance of early identification and treatment of patients with axial PsA.

The diagnosis of axial PsA is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosis). PsA can be differentiated from ankylosing spondylitis by the asymmetric and frequently unilateral presentation of sacroiliitis and syndesmophytes, which frequently presents as nonmarginal, bulky, asymmetric, and discontinuous skipping vertebral levels.

Plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI are all useful tools for evaluating patients with PsA. MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography is for detecting early joint inflammation and damage as well as axial changes, including sacroiliitis; however, they are not required for a diagnosis of PsA.

The treatment of axial PsA is based on international guidelines developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society–European League Against Rheumatism. Treatment focuses on minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; enhancing functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Medications for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; however, long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or if erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity is observed, guidelines recommend initiation of a TNF inhibitor. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective.

If symptoms of axial PsA are not controlled by NSAIDs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are recommended. However, interleukin 17A inhibitors may be used in preference to TNF inhibitors in patients with significant skin involvement. In the United States, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, and infliximab are recommended over etanercept for patients with axial SpA in the presence of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or recurrent uveitis (although there is no evidence for golimumab) because etanercept has contradictory results for uveitis and has not been shown to have efficacy in IBD.

If patients fail to respond to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic is recommended by US guidelines. A Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered for patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors.

Nonpharmacologic therapies (ie, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of axial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Psoriasis is a complex, chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease that is associated with significant morbidity, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality. Approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States have psoriasis; worldwide, approximately 2%-3% of the population is affected. Patients with psoriasis frequently have comorbidities; PsA, an inflammatory, seronegative musculoskeletal disease, is among the most common. It is estimated that 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis develop PsA.

PsA is a heterogeneous disease. Patients may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Men and women are equally affected by PsA, which typically develops when patients are age 30-50 years. Like psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

PsA is a potentially erosive disease. Structural damage and functional impairment occurs within 2 years of initial assessment in approximately 50% of patients; as the disease progresses, patients may experience irreversible joint damage and disability. Axial involvement occurs in 25%-70% of patients with PsA; exclusive axial involvement is uncommon, occurring in 5% of patients. Common symptoms of axial PsA include inflammatory back pain (eg, pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest, morning stiffness lasting longer than 30 minutes). Some patients with axial involvement may be asymptomatic. If untreated, cervical spinal mobility and lateral flexion significantly decline within 5 years in patients with axial PsA. In addition, sacroiliitis worsens over time; 37% and 52% of patients develop grade 2 or higher sacroiliitis within 5 and 10 years, respectively. This highlights the importance of early identification and treatment of patients with axial PsA.

The diagnosis of axial PsA is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosis). PsA can be differentiated from ankylosing spondylitis by the asymmetric and frequently unilateral presentation of sacroiliitis and syndesmophytes, which frequently presents as nonmarginal, bulky, asymmetric, and discontinuous skipping vertebral levels.

Plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI are all useful tools for evaluating patients with PsA. MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography is for detecting early joint inflammation and damage as well as axial changes, including sacroiliitis; however, they are not required for a diagnosis of PsA.

The treatment of axial PsA is based on international guidelines developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society–European League Against Rheumatism. Treatment focuses on minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; enhancing functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Medications for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; however, long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or if erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity is observed, guidelines recommend initiation of a TNF inhibitor. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective.

If symptoms of axial PsA are not controlled by NSAIDs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are recommended. However, interleukin 17A inhibitors may be used in preference to TNF inhibitors in patients with significant skin involvement. In the United States, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, and infliximab are recommended over etanercept for patients with axial SpA in the presence of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or recurrent uveitis (although there is no evidence for golimumab) because etanercept has contradictory results for uveitis and has not been shown to have efficacy in IBD.

If patients fail to respond to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic is recommended by US guidelines. A Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered for patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors.

Nonpharmacologic therapies (ie, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 38-year-old nonsmoking woman presents with complaints of moderate to severe back pain of approximately 6 months' duration. She also reports morning back/neck stiffness that lasts for approximately 45 minutes and pain/stiffness in her wrists and fingers. The patient states that her back pain improves with exercise (walking and stretching) and worsens in the evening and during long periods of rest. On occasion, she is awakened during the early morning hours because of her back pain. The patient has a 15-year history of moderate to severe psoriasis and a history of irritable bowel disease (IBD). Current medications include cyclosporine 3 mg/d, topical roflumilast 0.3%/d, and loperamide 3 mg as needed. The patient is 5 ft 5 in and weighs 183 lb (BMI of 30.4).

Physical examination reveals psoriatic plaques on the hands, elbows, and knees and nail dystrophy (onycholysis and pitting). Vital signs are within normal ranges. Pertinent laboratory findings include white blood count of 12,000 mcL (> 50% polymorphonuclear leukocytes), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 19 mm/h, and c-reactive protein of 3 mg/dL. Rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, and anti-citrullinated protein antibody antibody were negative.

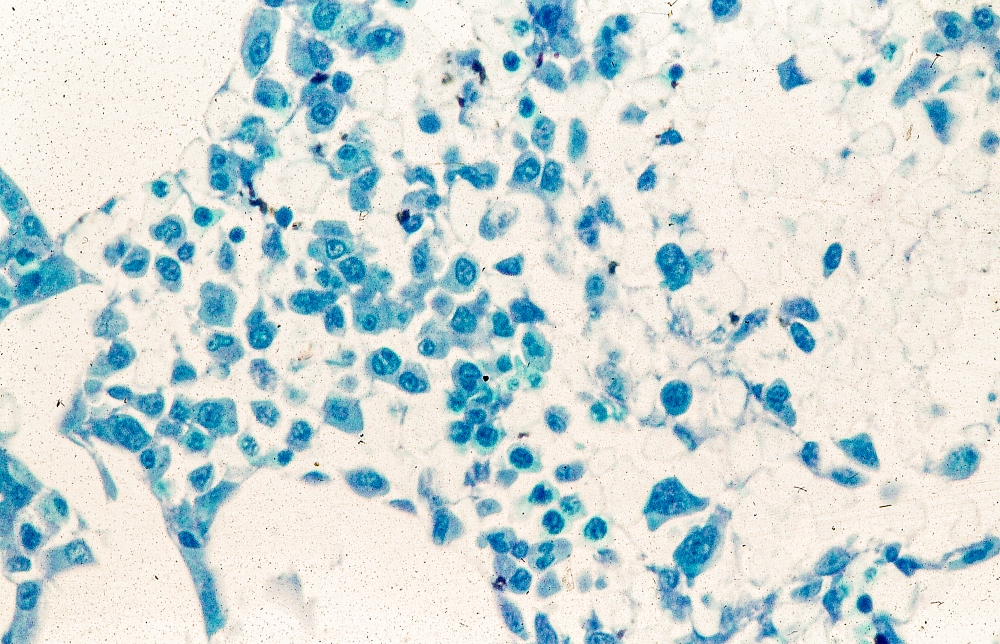

AI predicts endometrial cancer recurrence

Endometrial cancer is the most frequently occurring uterine cancer. Early-stage patients have about a 95% 5-year survival, but distant recurrence is associated with very poor survival, according to Sarah Fremond, MSc, an author of the research (Abstract 5695), which she presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“Most patients with endometrial cancer have a good prognosis and would not require any adjuvant treatment, but there is a proportion that will develop distant recurrence. For those you want to recommend adjuvant chemotherapy, because currently in the adjuvant setting, that’s the only treatment that is known to lower the risk of distant recurrence. But that also causes morbidity. Therefore, our clinical question was how to accurately identify patients at low and high risk of distant recurrence to reduce under- and overtreatment,” said Ms. Fremond, a PhD candidate at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

Pathologists can attempt such predictions, but Ms. Fremond noted that there are challenges. “There is a lot of variability between pathologists, and we don’t even use the entire visual information present in the H&E [hematoxylin and eosin] tumor slide. When it comes to molecular testing, it is hampered by cost, turnaround time, and sometimes interpretation. It’s quite complex to combine those data to specifically target risk of distant recurrence for patients with endometrial cancer.”

In her presentation, Ms. Fremond described how she and her colleagues used digitized histopathological slides in their research. She and her coauthors developed the AI model as part of a collaboration that included the AIRMEC Consortium, Leiden University Medical Center, the TransPORTEC Consortium, and the University of Zürich.

The researchers used long-term follow-up data from 1,408 patients drawn from three clinical cohorts and participants in the PORTEC-1, PORTEC-2, and PORTEC-3 studies, which tested radiotherapy and adjuvant therapy outcomes in endometrial cancer. Patients who had received prior adjuvant chemotherapy were excluded. In the model development phase, the system analyzed a single representative histopathological slide image from each patient and compared it with the known time to distant recurrence to identify patterns.

Once the system had been trained, the researchers applied it to a novel group of 353 patients. It ranked 89 patients as having a low risk of recurrence, 175 at intermediate risk, and 89 at high risk of recurrence. The system performed well: 3.37% of low-risk patients experienced a distant recurrence, as did 15.43% of the intermediate-risk group and 36% of the high-risk group.

The researchers also employed an external validation group with 152 patients and three slides per patient, with a 2.8-year follow-up. The model performed with a C index of 0.805 (±0.0136) when a random slide was selected for each patient, and the median predicted risk score per patient was associated with differences in distant recurrence-free survival between the three risk groups with a C index of 0.816 (P < .0001).

Questions about research and their answers

Session moderator Kristin Swanson, PhD, asked if the AI could be used with the pathology slide’s visible features to learn more about the underlying biology and pathophysiology of tumors.

“Overlying the HECTOR on to the tissue seems like a logical opportunity to go and then explore the biology and what’s attributed as a high-risk region,” said Dr. Swanson, who is director of the Mathematical NeuroOncology Lab and codirector of the Precision NeuroTherapeutics Innovation Program at Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix.

Ms. Fremond agreed that the AI has the potential to be used that way.”

During the Q&A, an audience member asked how likely the model is to perform in populations that differ significantly from the populations used in her study.

Ms. Fremond responded that the populations used to develop and test the models were in or close to the Netherlands, and little information was available regarding patient ethnicity. “There is a possibility that perhaps we would have a different performance on a population that includes more minorities. That needs to be checked,” said Ms. Fremond.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature.

Ms. Fremond and Dr. Swanson have no relevant financial disclosures.

Endometrial cancer is the most frequently occurring uterine cancer. Early-stage patients have about a 95% 5-year survival, but distant recurrence is associated with very poor survival, according to Sarah Fremond, MSc, an author of the research (Abstract 5695), which she presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“Most patients with endometrial cancer have a good prognosis and would not require any adjuvant treatment, but there is a proportion that will develop distant recurrence. For those you want to recommend adjuvant chemotherapy, because currently in the adjuvant setting, that’s the only treatment that is known to lower the risk of distant recurrence. But that also causes morbidity. Therefore, our clinical question was how to accurately identify patients at low and high risk of distant recurrence to reduce under- and overtreatment,” said Ms. Fremond, a PhD candidate at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

Pathologists can attempt such predictions, but Ms. Fremond noted that there are challenges. “There is a lot of variability between pathologists, and we don’t even use the entire visual information present in the H&E [hematoxylin and eosin] tumor slide. When it comes to molecular testing, it is hampered by cost, turnaround time, and sometimes interpretation. It’s quite complex to combine those data to specifically target risk of distant recurrence for patients with endometrial cancer.”

In her presentation, Ms. Fremond described how she and her colleagues used digitized histopathological slides in their research. She and her coauthors developed the AI model as part of a collaboration that included the AIRMEC Consortium, Leiden University Medical Center, the TransPORTEC Consortium, and the University of Zürich.

The researchers used long-term follow-up data from 1,408 patients drawn from three clinical cohorts and participants in the PORTEC-1, PORTEC-2, and PORTEC-3 studies, which tested radiotherapy and adjuvant therapy outcomes in endometrial cancer. Patients who had received prior adjuvant chemotherapy were excluded. In the model development phase, the system analyzed a single representative histopathological slide image from each patient and compared it with the known time to distant recurrence to identify patterns.

Once the system had been trained, the researchers applied it to a novel group of 353 patients. It ranked 89 patients as having a low risk of recurrence, 175 at intermediate risk, and 89 at high risk of recurrence. The system performed well: 3.37% of low-risk patients experienced a distant recurrence, as did 15.43% of the intermediate-risk group and 36% of the high-risk group.

The researchers also employed an external validation group with 152 patients and three slides per patient, with a 2.8-year follow-up. The model performed with a C index of 0.805 (±0.0136) when a random slide was selected for each patient, and the median predicted risk score per patient was associated with differences in distant recurrence-free survival between the three risk groups with a C index of 0.816 (P < .0001).

Questions about research and their answers

Session moderator Kristin Swanson, PhD, asked if the AI could be used with the pathology slide’s visible features to learn more about the underlying biology and pathophysiology of tumors.

“Overlying the HECTOR on to the tissue seems like a logical opportunity to go and then explore the biology and what’s attributed as a high-risk region,” said Dr. Swanson, who is director of the Mathematical NeuroOncology Lab and codirector of the Precision NeuroTherapeutics Innovation Program at Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix.

Ms. Fremond agreed that the AI has the potential to be used that way.”

During the Q&A, an audience member asked how likely the model is to perform in populations that differ significantly from the populations used in her study.

Ms. Fremond responded that the populations used to develop and test the models were in or close to the Netherlands, and little information was available regarding patient ethnicity. “There is a possibility that perhaps we would have a different performance on a population that includes more minorities. That needs to be checked,” said Ms. Fremond.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature.

Ms. Fremond and Dr. Swanson have no relevant financial disclosures.

Endometrial cancer is the most frequently occurring uterine cancer. Early-stage patients have about a 95% 5-year survival, but distant recurrence is associated with very poor survival, according to Sarah Fremond, MSc, an author of the research (Abstract 5695), which she presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“Most patients with endometrial cancer have a good prognosis and would not require any adjuvant treatment, but there is a proportion that will develop distant recurrence. For those you want to recommend adjuvant chemotherapy, because currently in the adjuvant setting, that’s the only treatment that is known to lower the risk of distant recurrence. But that also causes morbidity. Therefore, our clinical question was how to accurately identify patients at low and high risk of distant recurrence to reduce under- and overtreatment,” said Ms. Fremond, a PhD candidate at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

Pathologists can attempt such predictions, but Ms. Fremond noted that there are challenges. “There is a lot of variability between pathologists, and we don’t even use the entire visual information present in the H&E [hematoxylin and eosin] tumor slide. When it comes to molecular testing, it is hampered by cost, turnaround time, and sometimes interpretation. It’s quite complex to combine those data to specifically target risk of distant recurrence for patients with endometrial cancer.”

In her presentation, Ms. Fremond described how she and her colleagues used digitized histopathological slides in their research. She and her coauthors developed the AI model as part of a collaboration that included the AIRMEC Consortium, Leiden University Medical Center, the TransPORTEC Consortium, and the University of Zürich.

The researchers used long-term follow-up data from 1,408 patients drawn from three clinical cohorts and participants in the PORTEC-1, PORTEC-2, and PORTEC-3 studies, which tested radiotherapy and adjuvant therapy outcomes in endometrial cancer. Patients who had received prior adjuvant chemotherapy were excluded. In the model development phase, the system analyzed a single representative histopathological slide image from each patient and compared it with the known time to distant recurrence to identify patterns.

Once the system had been trained, the researchers applied it to a novel group of 353 patients. It ranked 89 patients as having a low risk of recurrence, 175 at intermediate risk, and 89 at high risk of recurrence. The system performed well: 3.37% of low-risk patients experienced a distant recurrence, as did 15.43% of the intermediate-risk group and 36% of the high-risk group.

The researchers also employed an external validation group with 152 patients and three slides per patient, with a 2.8-year follow-up. The model performed with a C index of 0.805 (±0.0136) when a random slide was selected for each patient, and the median predicted risk score per patient was associated with differences in distant recurrence-free survival between the three risk groups with a C index of 0.816 (P < .0001).

Questions about research and their answers

Session moderator Kristin Swanson, PhD, asked if the AI could be used with the pathology slide’s visible features to learn more about the underlying biology and pathophysiology of tumors.

“Overlying the HECTOR on to the tissue seems like a logical opportunity to go and then explore the biology and what’s attributed as a high-risk region,” said Dr. Swanson, who is director of the Mathematical NeuroOncology Lab and codirector of the Precision NeuroTherapeutics Innovation Program at Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix.

Ms. Fremond agreed that the AI has the potential to be used that way.”

During the Q&A, an audience member asked how likely the model is to perform in populations that differ significantly from the populations used in her study.

Ms. Fremond responded that the populations used to develop and test the models were in or close to the Netherlands, and little information was available regarding patient ethnicity. “There is a possibility that perhaps we would have a different performance on a population that includes more minorities. That needs to be checked,” said Ms. Fremond.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature.

Ms. Fremond and Dr. Swanson have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AACR 2023

CDC backs FDA’s call for second COVID booster for those at high risk

This backs the Food and Drug Administration’s authorization April 18 of the additional shot.

“Following FDA regulatory action, CDC has taken steps to simplify COVID-19 vaccine recommendations and allow more flexibility for people at higher risk who want the option of added protection from additional COVID-19 vaccine doses,” the CDC said in a statement.

The agency is following the recommendations made by its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). While there was no vote, the group reaffirmed its commitment to boosters overall, proposing that all Americans over age 6 who have not had a bivalent mRNA COVID-19 booster vaccine go ahead and get one.

But most others who’ve already had the bivalent shot – which targets the original COVID strain and the two Omicron variants BA.4 and BA.5 – should wait until the fall to get whatever updated vaccine is available.

The panel did carve out exceptions for people over age 65 and those who are immunocompromised because they are at higher risk for severe COVID-19 complications, Evelyn Twentyman, MD, MPH, the lead official in the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Policy Unit, said during the meeting.

People over 65 can now choose to get a second bivalent mRNA booster shot as long as it has been at least 4 months since the last one, she said, and people who are immunocompromised also should have the flexibility to receive one or more additional bivalent boosters at least 2 months after an initial dose.

Regardless of whether someone is unvaccinated, and regardless of how many single-strain COVID vaccines an individual has previously received, they should get a mRNA bivalent shot, Dr. Twentyman said.

If an individual has already received a bivalent mRNA booster – made by either Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna – “your vaccination is complete,” she said. “No doses indicated at this time, come back and see us in autumn of 2023.”

The CDC is trying to encourage more people to get the updated COVID shot, as just 17% of Americans of any age have received a bivalent booster and only 43% of those age 65 and over.

The CDC followed the FDA’s lead in its statement, phasing out the original single-strain COVID vaccine, saying it will no longer be recommended for use in the United States.

‘Unnecessary drama’ over children’s recs

The CDC panel mostly followed the FDA’s guidance on who should get a booster, but many ACIP members expressed consternation and confusion about what was being recommended for children.

For children aged 6 months to 4 years, the CDC will offer tables to help physicians determine how many bivalent doses to give, depending on the child’s vaccination history.

All children those ages should get at least two vaccine doses, one of which is bivalent, Dr. Twentyman said. For children in that age group who have already received a monovalent series and a bivalent dose, “their vaccination is complete,” she said.

For 5-year-olds, the recommendations will be similar if they received a Pfizer monovalent series, but the shot regimen will have to be customized if they had previously received a Moderna shot, because of differences in the dosages.

ACIP member Sarah S. Long, MD, professor of pediatrics, Drexel University, Philadelphia, said that it was unclear why a set age couldn’t be established for COVID-19 vaccination as it had been for other immunizations.

“We picked 60 months for most immunizations in children,” Dr. Long said. “Immunologically there is not a difference between a 4-, a 5- and a 6-year-old.

“There isn’t a reason to have all this unnecessary drama around those ages,” she said, adding that having the different ages would make it harder for pediatricians to appropriately stock vaccines.

Dr. Twentyman said that the CDC would be providing more detailed guidance on its COVID-19 website soon and would be holding a call with health care professionals to discuss the updated recommendations on May 11.

New vaccine by fall

CDC and ACIP members both said they hoped to have an even simpler vaccine schedule by the fall, when it is anticipated that the FDA may have authorized a new, updated bivalent vaccine that targets other COVID variants.

“We all recognize this is a work in progress,” said ACIP Chair Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, acknowledging that there is continued confusion over COVID-19 vaccination.

“The goal really is to try to simplify things over time to be able to help communicate with our provider community, and our patients and families what vaccine is right for them, when do they need it, and how often should they get it,” said Dr. Lee, professor of pediatrics, Stanford (Calif.) University.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com .

This backs the Food and Drug Administration’s authorization April 18 of the additional shot.

“Following FDA regulatory action, CDC has taken steps to simplify COVID-19 vaccine recommendations and allow more flexibility for people at higher risk who want the option of added protection from additional COVID-19 vaccine doses,” the CDC said in a statement.

The agency is following the recommendations made by its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). While there was no vote, the group reaffirmed its commitment to boosters overall, proposing that all Americans over age 6 who have not had a bivalent mRNA COVID-19 booster vaccine go ahead and get one.

But most others who’ve already had the bivalent shot – which targets the original COVID strain and the two Omicron variants BA.4 and BA.5 – should wait until the fall to get whatever updated vaccine is available.

The panel did carve out exceptions for people over age 65 and those who are immunocompromised because they are at higher risk for severe COVID-19 complications, Evelyn Twentyman, MD, MPH, the lead official in the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Policy Unit, said during the meeting.

People over 65 can now choose to get a second bivalent mRNA booster shot as long as it has been at least 4 months since the last one, she said, and people who are immunocompromised also should have the flexibility to receive one or more additional bivalent boosters at least 2 months after an initial dose.

Regardless of whether someone is unvaccinated, and regardless of how many single-strain COVID vaccines an individual has previously received, they should get a mRNA bivalent shot, Dr. Twentyman said.

If an individual has already received a bivalent mRNA booster – made by either Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna – “your vaccination is complete,” she said. “No doses indicated at this time, come back and see us in autumn of 2023.”

The CDC is trying to encourage more people to get the updated COVID shot, as just 17% of Americans of any age have received a bivalent booster and only 43% of those age 65 and over.

The CDC followed the FDA’s lead in its statement, phasing out the original single-strain COVID vaccine, saying it will no longer be recommended for use in the United States.

‘Unnecessary drama’ over children’s recs

The CDC panel mostly followed the FDA’s guidance on who should get a booster, but many ACIP members expressed consternation and confusion about what was being recommended for children.

For children aged 6 months to 4 years, the CDC will offer tables to help physicians determine how many bivalent doses to give, depending on the child’s vaccination history.

All children those ages should get at least two vaccine doses, one of which is bivalent, Dr. Twentyman said. For children in that age group who have already received a monovalent series and a bivalent dose, “their vaccination is complete,” she said.

For 5-year-olds, the recommendations will be similar if they received a Pfizer monovalent series, but the shot regimen will have to be customized if they had previously received a Moderna shot, because of differences in the dosages.

ACIP member Sarah S. Long, MD, professor of pediatrics, Drexel University, Philadelphia, said that it was unclear why a set age couldn’t be established for COVID-19 vaccination as it had been for other immunizations.

“We picked 60 months for most immunizations in children,” Dr. Long said. “Immunologically there is not a difference between a 4-, a 5- and a 6-year-old.

“There isn’t a reason to have all this unnecessary drama around those ages,” she said, adding that having the different ages would make it harder for pediatricians to appropriately stock vaccines.

Dr. Twentyman said that the CDC would be providing more detailed guidance on its COVID-19 website soon and would be holding a call with health care professionals to discuss the updated recommendations on May 11.

New vaccine by fall

CDC and ACIP members both said they hoped to have an even simpler vaccine schedule by the fall, when it is anticipated that the FDA may have authorized a new, updated bivalent vaccine that targets other COVID variants.

“We all recognize this is a work in progress,” said ACIP Chair Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, acknowledging that there is continued confusion over COVID-19 vaccination.

“The goal really is to try to simplify things over time to be able to help communicate with our provider community, and our patients and families what vaccine is right for them, when do they need it, and how often should they get it,” said Dr. Lee, professor of pediatrics, Stanford (Calif.) University.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com .

This backs the Food and Drug Administration’s authorization April 18 of the additional shot.

“Following FDA regulatory action, CDC has taken steps to simplify COVID-19 vaccine recommendations and allow more flexibility for people at higher risk who want the option of added protection from additional COVID-19 vaccine doses,” the CDC said in a statement.

The agency is following the recommendations made by its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). While there was no vote, the group reaffirmed its commitment to boosters overall, proposing that all Americans over age 6 who have not had a bivalent mRNA COVID-19 booster vaccine go ahead and get one.

But most others who’ve already had the bivalent shot – which targets the original COVID strain and the two Omicron variants BA.4 and BA.5 – should wait until the fall to get whatever updated vaccine is available.

The panel did carve out exceptions for people over age 65 and those who are immunocompromised because they are at higher risk for severe COVID-19 complications, Evelyn Twentyman, MD, MPH, the lead official in the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Policy Unit, said during the meeting.

People over 65 can now choose to get a second bivalent mRNA booster shot as long as it has been at least 4 months since the last one, she said, and people who are immunocompromised also should have the flexibility to receive one or more additional bivalent boosters at least 2 months after an initial dose.

Regardless of whether someone is unvaccinated, and regardless of how many single-strain COVID vaccines an individual has previously received, they should get a mRNA bivalent shot, Dr. Twentyman said.

If an individual has already received a bivalent mRNA booster – made by either Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna – “your vaccination is complete,” she said. “No doses indicated at this time, come back and see us in autumn of 2023.”

The CDC is trying to encourage more people to get the updated COVID shot, as just 17% of Americans of any age have received a bivalent booster and only 43% of those age 65 and over.

The CDC followed the FDA’s lead in its statement, phasing out the original single-strain COVID vaccine, saying it will no longer be recommended for use in the United States.

‘Unnecessary drama’ over children’s recs

The CDC panel mostly followed the FDA’s guidance on who should get a booster, but many ACIP members expressed consternation and confusion about what was being recommended for children.

For children aged 6 months to 4 years, the CDC will offer tables to help physicians determine how many bivalent doses to give, depending on the child’s vaccination history.

All children those ages should get at least two vaccine doses, one of which is bivalent, Dr. Twentyman said. For children in that age group who have already received a monovalent series and a bivalent dose, “their vaccination is complete,” she said.

For 5-year-olds, the recommendations will be similar if they received a Pfizer monovalent series, but the shot regimen will have to be customized if they had previously received a Moderna shot, because of differences in the dosages.

ACIP member Sarah S. Long, MD, professor of pediatrics, Drexel University, Philadelphia, said that it was unclear why a set age couldn’t be established for COVID-19 vaccination as it had been for other immunizations.

“We picked 60 months for most immunizations in children,” Dr. Long said. “Immunologically there is not a difference between a 4-, a 5- and a 6-year-old.

“There isn’t a reason to have all this unnecessary drama around those ages,” she said, adding that having the different ages would make it harder for pediatricians to appropriately stock vaccines.

Dr. Twentyman said that the CDC would be providing more detailed guidance on its COVID-19 website soon and would be holding a call with health care professionals to discuss the updated recommendations on May 11.

New vaccine by fall

CDC and ACIP members both said they hoped to have an even simpler vaccine schedule by the fall, when it is anticipated that the FDA may have authorized a new, updated bivalent vaccine that targets other COVID variants.

“We all recognize this is a work in progress,” said ACIP Chair Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, acknowledging that there is continued confusion over COVID-19 vaccination.

“The goal really is to try to simplify things over time to be able to help communicate with our provider community, and our patients and families what vaccine is right for them, when do they need it, and how often should they get it,” said Dr. Lee, professor of pediatrics, Stanford (Calif.) University.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com .

Weight gain and excessive fatigue

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Cushing syndrome (CS).

CS is a rare endocrine disease caused by prolonged exposure to high circulating cortisol levels. Exogenous hypercortisolism is the most common cause of CS. It is largely iatrogenic and results from the prolonged use of glucocorticoids. Less frequently, endogenous CS may occur as the result of excessive production of cortisol by adrenal glands. Endogenous CS can be ACTH-dependent or ACTH-independent. ACTH-dependent CS results from ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas (Cushing disease) and ectopic ACTH secretion by neoplasms, whereas adrenal hyperplasia, adenoma, and carcinoma are the primary causes of ACTH-independent CS.

The annual incidence and prevalence of CS are unknown; the reported incidence of newly diagnosed cases has ranged from 1.2 to 2.4 per million people per year. Women are affected more often than are men, with a peak of incidence in the third to fourth decade of life. CS is associated with various metabolic, psychiatric, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular comorbidities. Untreated, it is associated with increased mortality, typically as the result of cardiovascular and infectious complications; however, even in appropriately treated patients, mortality is elevated.

The chronic elevations of glucocorticoid concentrations in CS result in its characteristic phenotype, which includes weight gain, moon-shaped face, buffalo hump, muscle weakness, increased bruising, skin atrophy, red abdominal striae, menstrual irregularities, hirsutism, and acne. It is also associated with numerous comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and osteoporosis. Patients often experience mental health complications, such as depression, emotional lability, and cognitive dysfunction.

Given the rarity of CS and the fact that these symptoms overlap with other conditions, delayed diagnosis is common. The current obesity epidemic also poses diagnostic challenges because true CS can be difficult to differentiate from metabolic syndrome. The duration of hypercortisolism appears to be the most significant factor associated with the degree of morbidity and preterm mortality in CS; thus, an accurate diagnosis as early as possible is important.

Screening and diagnostic tests for CS evaluate cortisol secretion. Available options include late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC), impaired glucocorticoid feedback with overnight 1-mg DST or low-dose 2-day dexamethasone test (LDDT) and increased bioavailable cortisol with 24-hour UFC.

A 2021 consensus statement by Fleseriu and colleagues provides recommendations for the diagnosis of CS. If CS is suspected: begin with UFC, LNSC, or both; DST is an option if LNSC not feasible. If CS because of adrenal tumor is suspected: begin with DST because LNSC has lower specificity in these patients. To confirm CS, any of these tests can be used.

An individualized approach is recommended for the treatment of CS. The optimal approach for iatrogenic CS is to slowly taper exogenous steroids. Chronic exposure to steroids can suppress adrenal functioning; as such, recovery may take several months. Surgical resection is the first-line option for hypercortisolism because of Cushing disease, adrenal tumor, or ectopic tumor. Patients should be closely monitored after surgery to evaluate for possible recurrence. Radiotherapy may be recommended after failed transsphenoidal surgery or in Cushing disease with mass effect or invasion of surrounding structures. Medical therapy, such as pasireotide, cabergoline, and mifepristone, are also sometimes used. In addition, the treatment of comorbidities, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, psychiatric issues, and electrolyte disorders, is critical.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Cushing syndrome (CS).

CS is a rare endocrine disease caused by prolonged exposure to high circulating cortisol levels. Exogenous hypercortisolism is the most common cause of CS. It is largely iatrogenic and results from the prolonged use of glucocorticoids. Less frequently, endogenous CS may occur as the result of excessive production of cortisol by adrenal glands. Endogenous CS can be ACTH-dependent or ACTH-independent. ACTH-dependent CS results from ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas (Cushing disease) and ectopic ACTH secretion by neoplasms, whereas adrenal hyperplasia, adenoma, and carcinoma are the primary causes of ACTH-independent CS.

The annual incidence and prevalence of CS are unknown; the reported incidence of newly diagnosed cases has ranged from 1.2 to 2.4 per million people per year. Women are affected more often than are men, with a peak of incidence in the third to fourth decade of life. CS is associated with various metabolic, psychiatric, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular comorbidities. Untreated, it is associated with increased mortality, typically as the result of cardiovascular and infectious complications; however, even in appropriately treated patients, mortality is elevated.

The chronic elevations of glucocorticoid concentrations in CS result in its characteristic phenotype, which includes weight gain, moon-shaped face, buffalo hump, muscle weakness, increased bruising, skin atrophy, red abdominal striae, menstrual irregularities, hirsutism, and acne. It is also associated with numerous comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and osteoporosis. Patients often experience mental health complications, such as depression, emotional lability, and cognitive dysfunction.

Given the rarity of CS and the fact that these symptoms overlap with other conditions, delayed diagnosis is common. The current obesity epidemic also poses diagnostic challenges because true CS can be difficult to differentiate from metabolic syndrome. The duration of hypercortisolism appears to be the most significant factor associated with the degree of morbidity and preterm mortality in CS; thus, an accurate diagnosis as early as possible is important.

Screening and diagnostic tests for CS evaluate cortisol secretion. Available options include late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC), impaired glucocorticoid feedback with overnight 1-mg DST or low-dose 2-day dexamethasone test (LDDT) and increased bioavailable cortisol with 24-hour UFC.

A 2021 consensus statement by Fleseriu and colleagues provides recommendations for the diagnosis of CS. If CS is suspected: begin with UFC, LNSC, or both; DST is an option if LNSC not feasible. If CS because of adrenal tumor is suspected: begin with DST because LNSC has lower specificity in these patients. To confirm CS, any of these tests can be used.

An individualized approach is recommended for the treatment of CS. The optimal approach for iatrogenic CS is to slowly taper exogenous steroids. Chronic exposure to steroids can suppress adrenal functioning; as such, recovery may take several months. Surgical resection is the first-line option for hypercortisolism because of Cushing disease, adrenal tumor, or ectopic tumor. Patients should be closely monitored after surgery to evaluate for possible recurrence. Radiotherapy may be recommended after failed transsphenoidal surgery or in Cushing disease with mass effect or invasion of surrounding structures. Medical therapy, such as pasireotide, cabergoline, and mifepristone, are also sometimes used. In addition, the treatment of comorbidities, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, psychiatric issues, and electrolyte disorders, is critical.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Cushing syndrome (CS).

CS is a rare endocrine disease caused by prolonged exposure to high circulating cortisol levels. Exogenous hypercortisolism is the most common cause of CS. It is largely iatrogenic and results from the prolonged use of glucocorticoids. Less frequently, endogenous CS may occur as the result of excessive production of cortisol by adrenal glands. Endogenous CS can be ACTH-dependent or ACTH-independent. ACTH-dependent CS results from ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas (Cushing disease) and ectopic ACTH secretion by neoplasms, whereas adrenal hyperplasia, adenoma, and carcinoma are the primary causes of ACTH-independent CS.

The annual incidence and prevalence of CS are unknown; the reported incidence of newly diagnosed cases has ranged from 1.2 to 2.4 per million people per year. Women are affected more often than are men, with a peak of incidence in the third to fourth decade of life. CS is associated with various metabolic, psychiatric, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular comorbidities. Untreated, it is associated with increased mortality, typically as the result of cardiovascular and infectious complications; however, even in appropriately treated patients, mortality is elevated.

The chronic elevations of glucocorticoid concentrations in CS result in its characteristic phenotype, which includes weight gain, moon-shaped face, buffalo hump, muscle weakness, increased bruising, skin atrophy, red abdominal striae, menstrual irregularities, hirsutism, and acne. It is also associated with numerous comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and osteoporosis. Patients often experience mental health complications, such as depression, emotional lability, and cognitive dysfunction.

Given the rarity of CS and the fact that these symptoms overlap with other conditions, delayed diagnosis is common. The current obesity epidemic also poses diagnostic challenges because true CS can be difficult to differentiate from metabolic syndrome. The duration of hypercortisolism appears to be the most significant factor associated with the degree of morbidity and preterm mortality in CS; thus, an accurate diagnosis as early as possible is important.

Screening and diagnostic tests for CS evaluate cortisol secretion. Available options include late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC), impaired glucocorticoid feedback with overnight 1-mg DST or low-dose 2-day dexamethasone test (LDDT) and increased bioavailable cortisol with 24-hour UFC.