User login

Physician compensation continues to climb amid postpandemic change

In addition, gender-based pay disparity among primary care physicians shrank, and the number of physicians who declined to take new Medicare patients rose.

The annual report is based on a survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties who answered questions about their income, workload, challenges, and level of satisfaction.

Average compensation across specialties rose to $352,000 – up nearly 17% from the 2018 average of $299,000. Fallout from the COVID-19 public health emergency continued to affect both physician compensation and job satisfaction, including Medicare reimbursements and staffing shortages due to burnout or retirement.

“Many physicians reevaluated what drove them to be a physician,” says Marc Adam, a recruiter at MASC Medical, a Florida physician recruiting firm.

Adam cites telehealth as an example. “An overwhelming majority of physicians prefer telehealth because of the convenience, but some really did not want to do it long term. They miss the patient interaction.”

The report also revealed that the gender-based pay gap in primary physicians fell, with men earning 19% more – down from 25% more in recent years. Among specialists, the gender gap was 27% on average, down from 31% last year. One reason may be an increase in compensation transparency, which Mr. Adam says should be the norm.

Income increases will likely continue, owing in large part to the growing disparity between physician supply and demand.

The projected physician shortage is expected to grow to 124,000 by 2034, according to the American Association of Medical Colleges. Federal lawmakers are considering passing the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2023, which would add 14,000 Medicare-funded residency positions to help alleviate shortages.

Patient needs, Medicare rules continue to shift

Specialties with the biggest increases in compensation include oncology, anesthesiology, gastroenterology, radiology, critical care, and urology. Many procedure-related specialties saw more volume post pandemic.

Some respondents identified Medicare cuts and low reimbursement rates as a factor in tamping down compensation hikes. The number of physicians who expect to continue to take new Medicare patients is 65%, down from 71% 5 years ago.

For example, Medicare reimbursements for telehealth are expected to scale down in May, when the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, which expanded telehealth services for Medicare patients, winds down.

“Telehealth will still exist,” says Mr. Adam, “but certain requirements will shape it going forward.”

Medicare isn’t viewed negatively across the board, however. Florida is among the top-earning states for physicians – along with Indiana, Connecticut, and Missouri. One reason is Florida’s unique health care environment, explains Mr. Adam, whose Florida-based firm places physicians nationwide.

“Florida is very progressive in terms of health care. For one thing, we have a large aging population and a large Medicare population.” Several growing organizations that focus on quality-based care are based in Florida, including ChenMed and Cano Health. Add to that the fact that owners of Florida’s health care organizations don’t have to be physicians, he explains, and the stage is set for experimentation.

“Being able to segment tasks frees up physicians to be more focused on medicine and provide better care while other people focus on the business and innovation.”

If Florida’s high compensation ranking continues, it may help employers there fulfill a growing need. The state is among those expected to experience the largest physician shortages in 2030, along with California, Texas, Arizona, and Georgia.

Side gigs up, satisfaction (slightly) down

In general, physicians aren’t fazed by these challenges. Many reported taking side gigs, some for additional income. Even so, 73% say they would still choose medicine, and more than 90% of physicians in 10 specialties would choose their specialty again. Still, burnout and stressors have led some to stop practicing altogether.

More and more organizations are hiring “travel physicians,” Mr. Adam says, and more physicians are choosing to take contract work (“locum tenens”) and practice in many different regions. Contract physicians typically help meet patient demand or provide coverage during the hiring process as well as while staff are on vacation or maternity leave.

Says Mr. Adam, “There’s no security, but there’s higher income and more flexibility.”

According to CHG Healthcare, locum tenens staffing is rising – approximately 7% of U.S. physicians (around 50,000) filled assignments in 2022, up 88% from 2015. In 2022, 56% of locum tenens employers reported a reduction in staff burnout, up from 30% in 2020.

The report indicates that more than half of physicians are satisfied with their income, down slightly from 55% 5 years ago (prepandemic). Physicians in some of the lower-paying specialties are among those most satisfied with their income. It’s not very surprising to Mr. Adam: “Higher earners generally suffer the most from burnout.

“They’re overworked, they have the largest number of patients, and they’re performing in high-stress situations doing challenging procedures on a daily basis – and they probably have worse work-life balance.” These physicians know going in that they need to be paid more to deal with such burdens. “That’s the feedback I get when I speak to high earners,” says Mr. Adam.

“The experienced ones are very clear about their [compensation] expectations.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, gender-based pay disparity among primary care physicians shrank, and the number of physicians who declined to take new Medicare patients rose.

The annual report is based on a survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties who answered questions about their income, workload, challenges, and level of satisfaction.

Average compensation across specialties rose to $352,000 – up nearly 17% from the 2018 average of $299,000. Fallout from the COVID-19 public health emergency continued to affect both physician compensation and job satisfaction, including Medicare reimbursements and staffing shortages due to burnout or retirement.

“Many physicians reevaluated what drove them to be a physician,” says Marc Adam, a recruiter at MASC Medical, a Florida physician recruiting firm.

Adam cites telehealth as an example. “An overwhelming majority of physicians prefer telehealth because of the convenience, but some really did not want to do it long term. They miss the patient interaction.”

The report also revealed that the gender-based pay gap in primary physicians fell, with men earning 19% more – down from 25% more in recent years. Among specialists, the gender gap was 27% on average, down from 31% last year. One reason may be an increase in compensation transparency, which Mr. Adam says should be the norm.

Income increases will likely continue, owing in large part to the growing disparity between physician supply and demand.

The projected physician shortage is expected to grow to 124,000 by 2034, according to the American Association of Medical Colleges. Federal lawmakers are considering passing the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2023, which would add 14,000 Medicare-funded residency positions to help alleviate shortages.

Patient needs, Medicare rules continue to shift

Specialties with the biggest increases in compensation include oncology, anesthesiology, gastroenterology, radiology, critical care, and urology. Many procedure-related specialties saw more volume post pandemic.

Some respondents identified Medicare cuts and low reimbursement rates as a factor in tamping down compensation hikes. The number of physicians who expect to continue to take new Medicare patients is 65%, down from 71% 5 years ago.

For example, Medicare reimbursements for telehealth are expected to scale down in May, when the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, which expanded telehealth services for Medicare patients, winds down.

“Telehealth will still exist,” says Mr. Adam, “but certain requirements will shape it going forward.”

Medicare isn’t viewed negatively across the board, however. Florida is among the top-earning states for physicians – along with Indiana, Connecticut, and Missouri. One reason is Florida’s unique health care environment, explains Mr. Adam, whose Florida-based firm places physicians nationwide.

“Florida is very progressive in terms of health care. For one thing, we have a large aging population and a large Medicare population.” Several growing organizations that focus on quality-based care are based in Florida, including ChenMed and Cano Health. Add to that the fact that owners of Florida’s health care organizations don’t have to be physicians, he explains, and the stage is set for experimentation.

“Being able to segment tasks frees up physicians to be more focused on medicine and provide better care while other people focus on the business and innovation.”

If Florida’s high compensation ranking continues, it may help employers there fulfill a growing need. The state is among those expected to experience the largest physician shortages in 2030, along with California, Texas, Arizona, and Georgia.

Side gigs up, satisfaction (slightly) down

In general, physicians aren’t fazed by these challenges. Many reported taking side gigs, some for additional income. Even so, 73% say they would still choose medicine, and more than 90% of physicians in 10 specialties would choose their specialty again. Still, burnout and stressors have led some to stop practicing altogether.

More and more organizations are hiring “travel physicians,” Mr. Adam says, and more physicians are choosing to take contract work (“locum tenens”) and practice in many different regions. Contract physicians typically help meet patient demand or provide coverage during the hiring process as well as while staff are on vacation or maternity leave.

Says Mr. Adam, “There’s no security, but there’s higher income and more flexibility.”

According to CHG Healthcare, locum tenens staffing is rising – approximately 7% of U.S. physicians (around 50,000) filled assignments in 2022, up 88% from 2015. In 2022, 56% of locum tenens employers reported a reduction in staff burnout, up from 30% in 2020.

The report indicates that more than half of physicians are satisfied with their income, down slightly from 55% 5 years ago (prepandemic). Physicians in some of the lower-paying specialties are among those most satisfied with their income. It’s not very surprising to Mr. Adam: “Higher earners generally suffer the most from burnout.

“They’re overworked, they have the largest number of patients, and they’re performing in high-stress situations doing challenging procedures on a daily basis – and they probably have worse work-life balance.” These physicians know going in that they need to be paid more to deal with such burdens. “That’s the feedback I get when I speak to high earners,” says Mr. Adam.

“The experienced ones are very clear about their [compensation] expectations.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, gender-based pay disparity among primary care physicians shrank, and the number of physicians who declined to take new Medicare patients rose.

The annual report is based on a survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties who answered questions about their income, workload, challenges, and level of satisfaction.

Average compensation across specialties rose to $352,000 – up nearly 17% from the 2018 average of $299,000. Fallout from the COVID-19 public health emergency continued to affect both physician compensation and job satisfaction, including Medicare reimbursements and staffing shortages due to burnout or retirement.

“Many physicians reevaluated what drove them to be a physician,” says Marc Adam, a recruiter at MASC Medical, a Florida physician recruiting firm.

Adam cites telehealth as an example. “An overwhelming majority of physicians prefer telehealth because of the convenience, but some really did not want to do it long term. They miss the patient interaction.”

The report also revealed that the gender-based pay gap in primary physicians fell, with men earning 19% more – down from 25% more in recent years. Among specialists, the gender gap was 27% on average, down from 31% last year. One reason may be an increase in compensation transparency, which Mr. Adam says should be the norm.

Income increases will likely continue, owing in large part to the growing disparity between physician supply and demand.

The projected physician shortage is expected to grow to 124,000 by 2034, according to the American Association of Medical Colleges. Federal lawmakers are considering passing the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2023, which would add 14,000 Medicare-funded residency positions to help alleviate shortages.

Patient needs, Medicare rules continue to shift

Specialties with the biggest increases in compensation include oncology, anesthesiology, gastroenterology, radiology, critical care, and urology. Many procedure-related specialties saw more volume post pandemic.

Some respondents identified Medicare cuts and low reimbursement rates as a factor in tamping down compensation hikes. The number of physicians who expect to continue to take new Medicare patients is 65%, down from 71% 5 years ago.

For example, Medicare reimbursements for telehealth are expected to scale down in May, when the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, which expanded telehealth services for Medicare patients, winds down.

“Telehealth will still exist,” says Mr. Adam, “but certain requirements will shape it going forward.”

Medicare isn’t viewed negatively across the board, however. Florida is among the top-earning states for physicians – along with Indiana, Connecticut, and Missouri. One reason is Florida’s unique health care environment, explains Mr. Adam, whose Florida-based firm places physicians nationwide.

“Florida is very progressive in terms of health care. For one thing, we have a large aging population and a large Medicare population.” Several growing organizations that focus on quality-based care are based in Florida, including ChenMed and Cano Health. Add to that the fact that owners of Florida’s health care organizations don’t have to be physicians, he explains, and the stage is set for experimentation.

“Being able to segment tasks frees up physicians to be more focused on medicine and provide better care while other people focus on the business and innovation.”

If Florida’s high compensation ranking continues, it may help employers there fulfill a growing need. The state is among those expected to experience the largest physician shortages in 2030, along with California, Texas, Arizona, and Georgia.

Side gigs up, satisfaction (slightly) down

In general, physicians aren’t fazed by these challenges. Many reported taking side gigs, some for additional income. Even so, 73% say they would still choose medicine, and more than 90% of physicians in 10 specialties would choose their specialty again. Still, burnout and stressors have led some to stop practicing altogether.

More and more organizations are hiring “travel physicians,” Mr. Adam says, and more physicians are choosing to take contract work (“locum tenens”) and practice in many different regions. Contract physicians typically help meet patient demand or provide coverage during the hiring process as well as while staff are on vacation or maternity leave.

Says Mr. Adam, “There’s no security, but there’s higher income and more flexibility.”

According to CHG Healthcare, locum tenens staffing is rising – approximately 7% of U.S. physicians (around 50,000) filled assignments in 2022, up 88% from 2015. In 2022, 56% of locum tenens employers reported a reduction in staff burnout, up from 30% in 2020.

The report indicates that more than half of physicians are satisfied with their income, down slightly from 55% 5 years ago (prepandemic). Physicians in some of the lower-paying specialties are among those most satisfied with their income. It’s not very surprising to Mr. Adam: “Higher earners generally suffer the most from burnout.

“They’re overworked, they have the largest number of patients, and they’re performing in high-stress situations doing challenging procedures on a daily basis – and they probably have worse work-life balance.” These physicians know going in that they need to be paid more to deal with such burdens. “That’s the feedback I get when I speak to high earners,” says Mr. Adam.

“The experienced ones are very clear about their [compensation] expectations.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Deoxycholic Acid for Dercum Disease: Repurposing a Cosmetic Agent to Treat a Rare Disease

Dercum disease (or adiposis dolorosa) is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by multiple painful lipomas localized throughout the body.1,2 It typically presents in adults aged 35 to 50 years and is at least 5 times more common in women.3 It often is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, fatigue and weakness.1 There currently are no approved treatments for Dercum disease, only therapies tried with little to no efficacy for symptom management, including analgesics, excision, liposuction,1 lymphatic drainage,4 hypobaric pressure,5 and frequency rhythmic electrical modulation systems.6 For patients who continually develop widespread lesions, surgical excision is not feasible, which poses a therapeutic challenge. Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a bile acid that is approved to treat submental fat, disrupts the integrity of cell membranes, induces adipocyte lysis, and solubilizes fat when injected subcutaneously.7 We used DCA to mitigate pain and reduce lipoma size in patients with Dercum disease, which demonstrated lipoma reduction via ultrasonography in 3 patients.

Case Reports

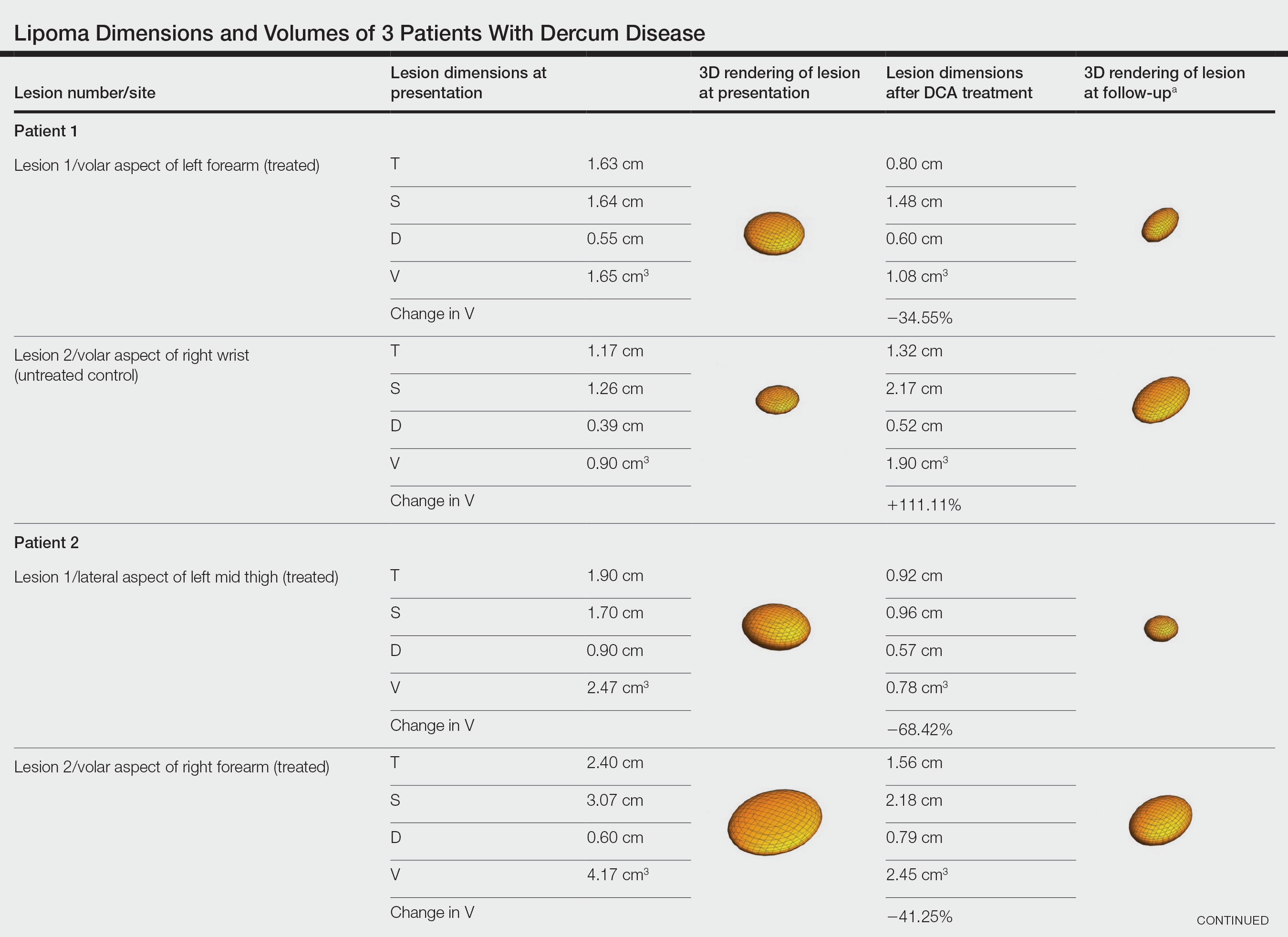

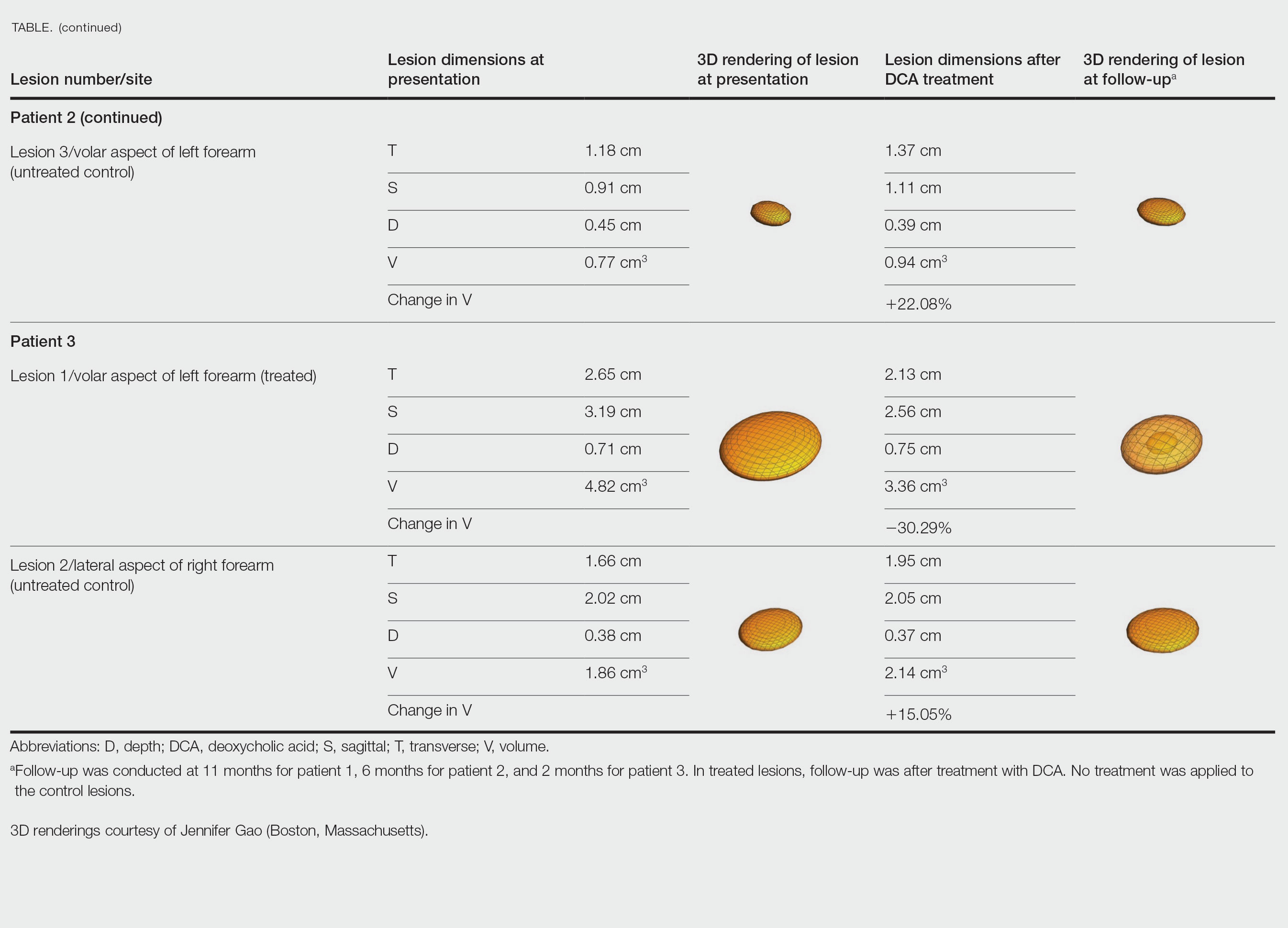

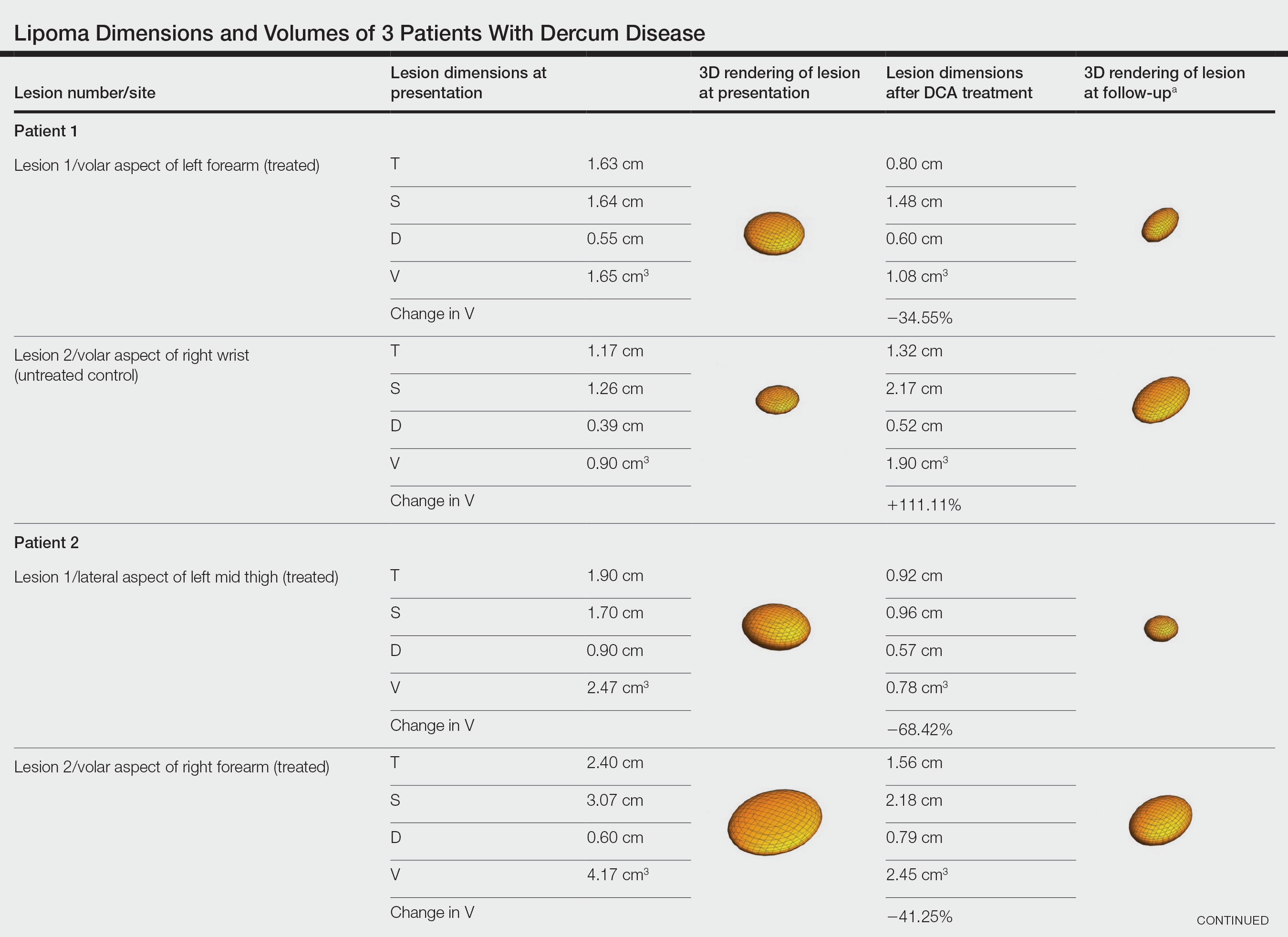

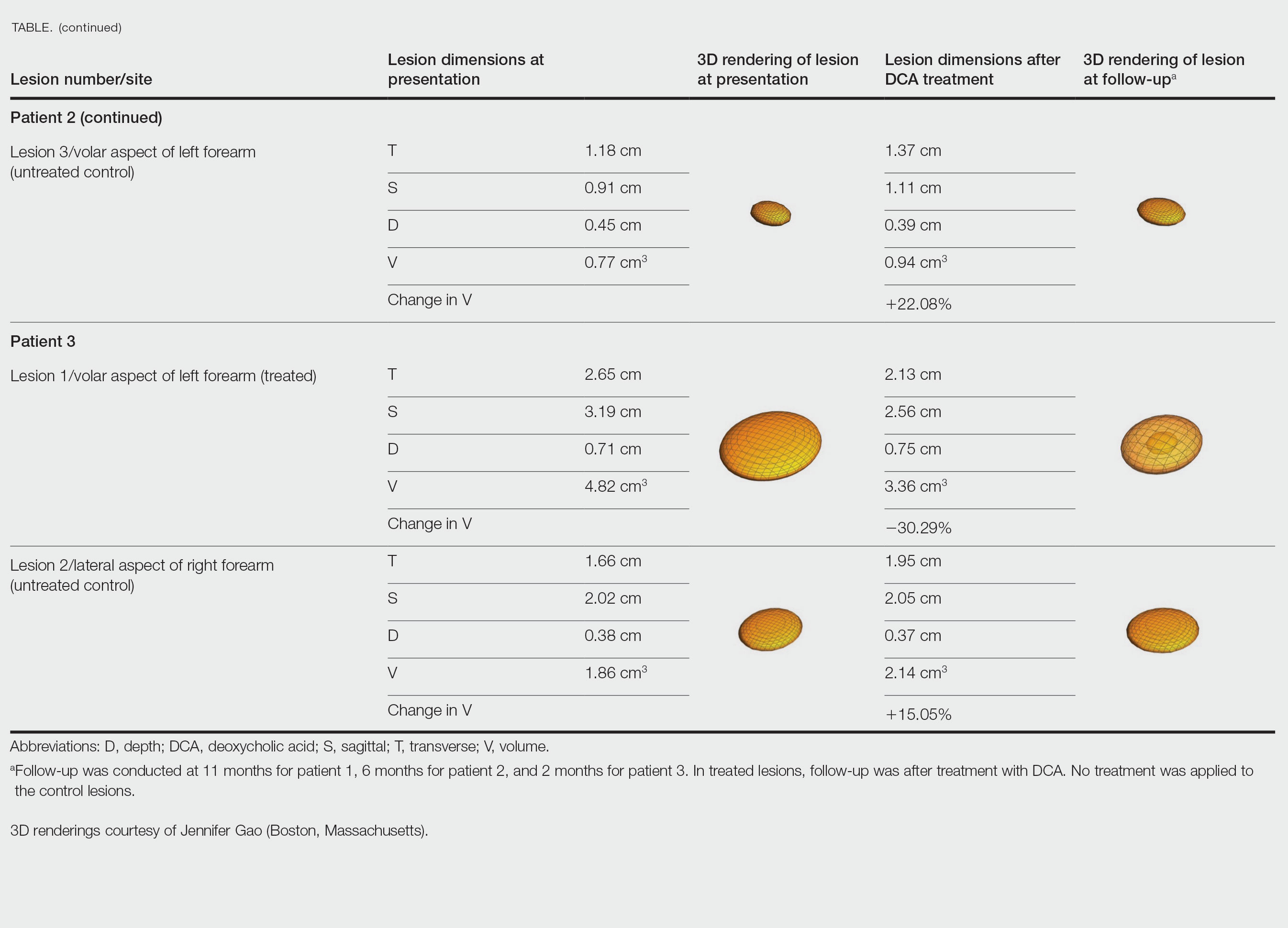

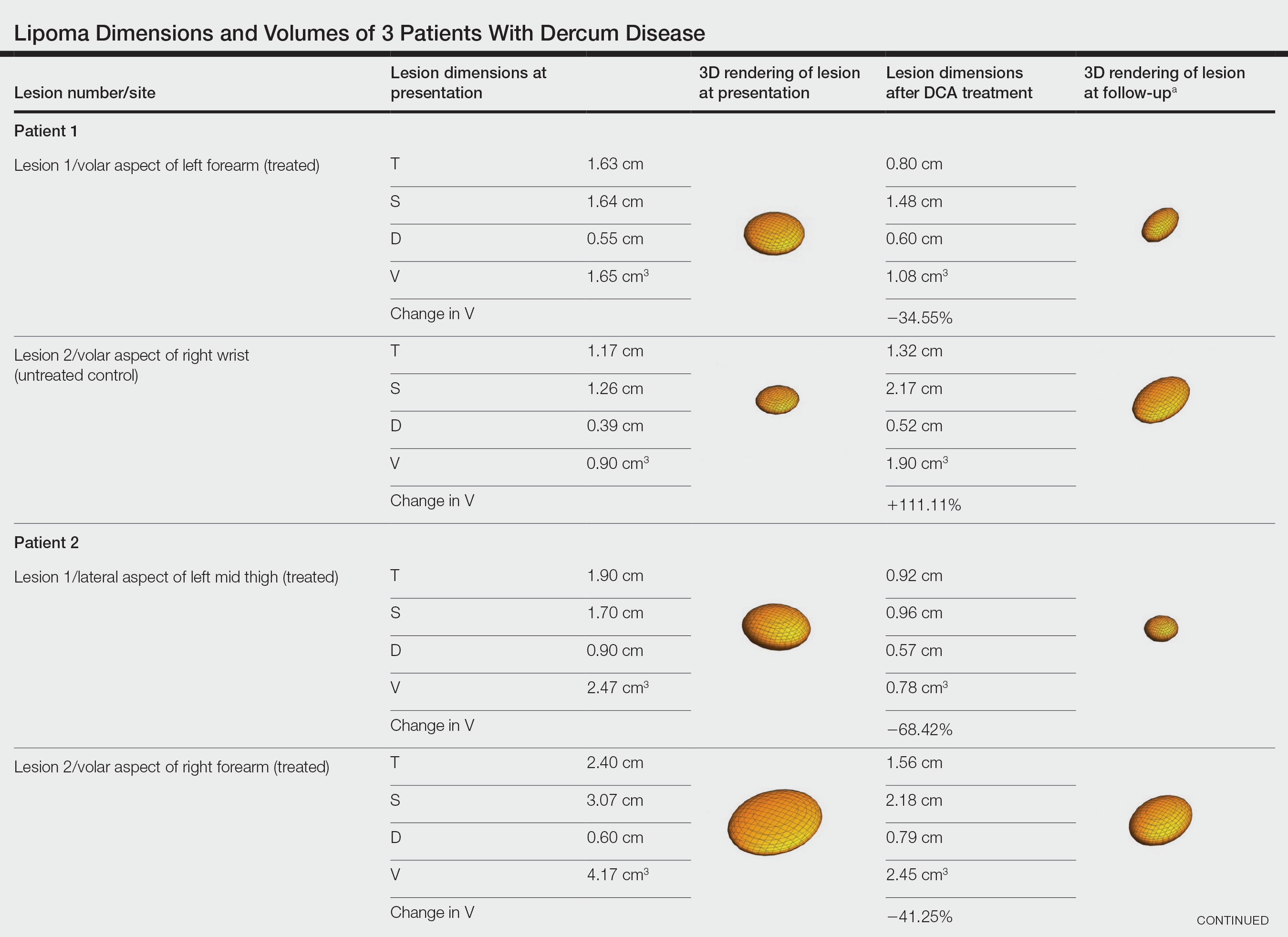

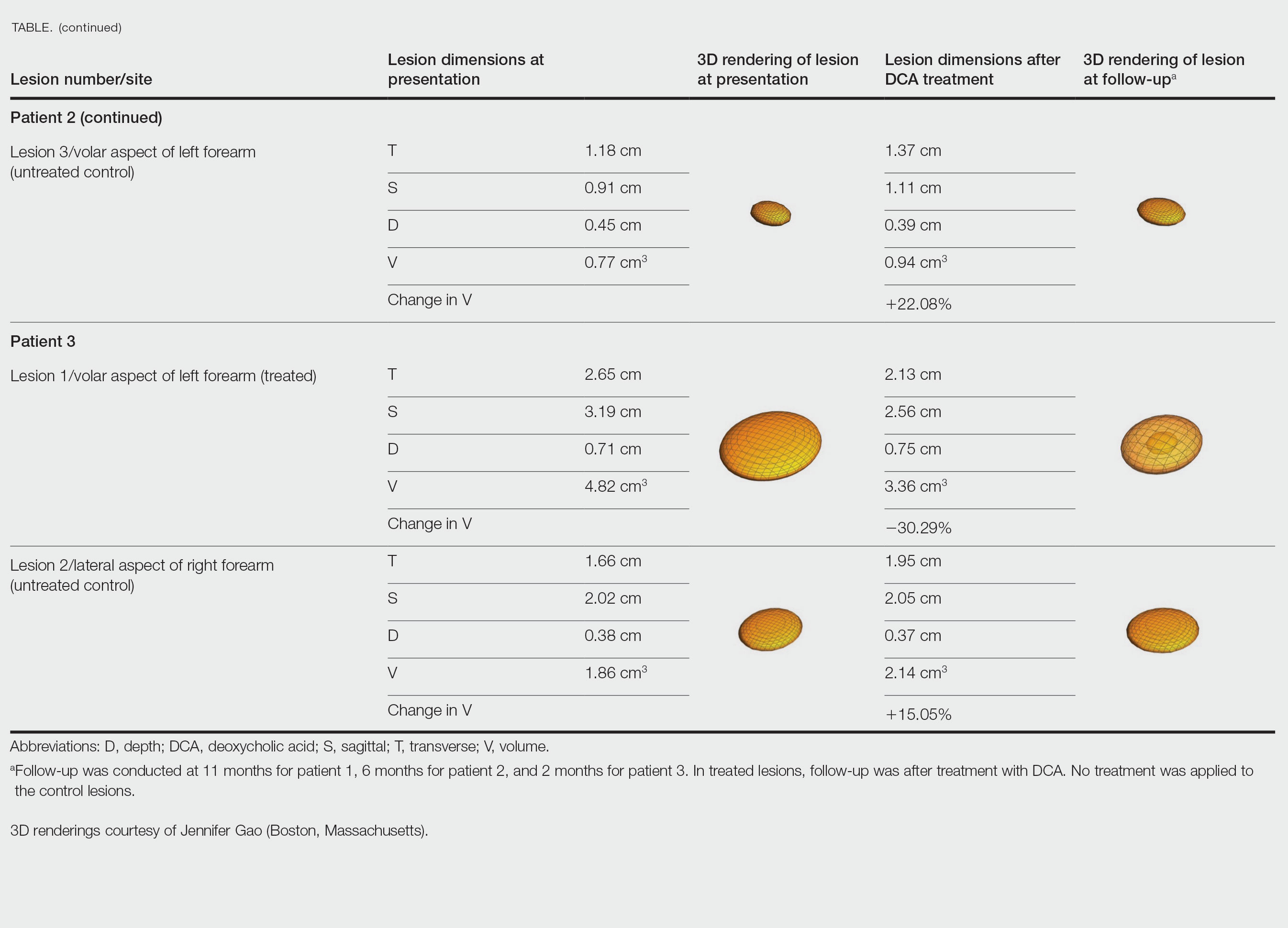

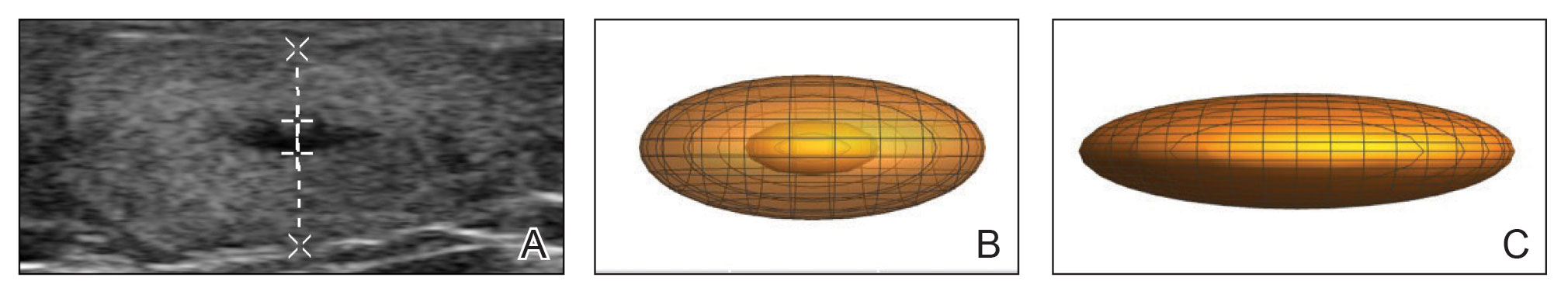

Three patients presented to clinic with multiple painful subcutaneous nodules throughout several areas of the body and were screened using radiography. Ultrasonography demonstrated numerous lipomas consistent with Dercum disease. The lipomas were measured by ultrasonography to obtain 3-dimensional measurements of each lesion. The most painful lipomas identified by the patients were either treated with 2 mL of DCA (10 mg/mL) or served as a control with no treatment. Patients returned for symptom monitoring and repeat measurements of both treated and untreated lipomas. Two physicians with expertise in ultrasonography measured lesions in a blinded fashion. Photographs were obtained with patient consent.

Patient 1—A 45-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease that was confirmed via ultrasonography. A painful 1.63×1.64×0.55-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the left forearm, and a 1.17×1.26×0.39-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the right wrist. At a follow-up visit 11 months later, 2 mL of DCA was administered to the lipoma on the volar aspect of the left forearm, while the lipoma on the volar aspect of the right wrist was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported 1 week of swelling and tenderness of the treated area. Repeat imaging 4 months after administration of DCA revealed reduction of the treated lesion to 0.80×1.48×0.60 cm and growth of the untreated lesion to 1.32×2.17×0.52 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 34.55%, while the lipoma in the untreated control increased in volume from its original measurement by 111.11% (Table). The patient also reported decreased pain in the treated area at all follow-up visits in the 1 year following the procedure.

Patient 2—A 42-year-old woman with Dercum disease received administration of 2 mL of DCA to a 1.90×1.70×0.90-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh and 2 mL of DCA to a 2.40×3.07×0.60-cm lipoma on the volar aspect of the right forearm 2 weeks later. A 1.18×0.91×0.45-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm was monitored as an untreated control. The patient reported bruising and discoloration a few weeks following the procedure. At subsequent 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, the patient reported induration in the volar aspect of the right forearm and noticeable reduction in size of the lesion in the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported reduction in size of both lesions and improvement of the previously noted side effects. Repeat ultrasonography approximately 6 months after administration of DCA demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh to 0.92×0.96×0.57 cm and the volar aspect of the right forearm to 1.56×2.18×0.79 cm, with growth of the untreated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 1.37×1.11×0.39 cm. The treated lipomas reduced in volume by 68.42% and 41.25%, respectively, and the untreated control increased in volume by 22.08% (Table).

Patient 3—A 75-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease verified by ultrasonography. The patient was administered 2 mL of DCA to a 2.65×3.19×0.71-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm. A 1.66×2.02×0.38-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the right forearm was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported initial swelling that persisted for a few weeks followed by notable pain relief and a decrease in lipoma size. At 2-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain or other adverse effects, while repeat imaging demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 2.13×2.56×0.75 cm and growth of the untreated lesion on the lateral aspect of the right forearm to 1.95×2.05×0.37 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 30.29%, and the untreated control increased in volume by 15.05% (Table).

Comment

Deoxycholic acid is a bile acid naturally found in the body that helps to emulsify and solubilize fats in the intestines. When injected subcutaneously, DCA becomes an adipolytic agent that induces inflammation and targets adipose degradation by macrophages, and it has been manufactured to reduce submental fat.7 Off-label use of DCA has been explored for nonsurgical body contouring and lipomas with promising results in some cases; however, these prior studies have been limited by the lack of quantitative objective measurements to effectively demonstrate the impact of treatment.8,9

We present 3 patients who requested treatment for numerous painful lipomas. Given the extent of their disease, surgical options were not feasible, and the patients opted to try a nonsurgical alternative. In each case, the painful lipomas that were chosen for treatment were injected with 2 mL of DCA. Injection-associated symptoms included swelling, tenderness, discoloration, and induration, which resolved over a period of months. Patient 1 had a treated lipoma that reduced in volume by approximately 35%, while the control continued to grow and doubled in volume. In patient 2, the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the mid thigh reduced in volume by almost 70%, and the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the right forearm reduced in volume by more than 40%, while the control grew by more than 20%. In patient 3, the volume of the treated lipoma decreased by 30%, and the control increased by 15%. The follow-up interval was shortest in patient 3—2 months as opposed to 11 months and 6 months for patients 1 and 2, respectively; therefore, more progress may be seen in patient 3 with more time. Interestingly, a change in shape of the lipoma was noted in patient 3 (Figure)—an increase in its depth while the center became anechoic, which is a sign of hollowing in the center due to the saponification of fat and a possible cause for the change from an elliptical to a more spherical or doughnutlike shape. Intralesional administration of DCA may offer patients with extensive lipomas, such as those seen in patients with Dercum disease, an alternative, less-invasive option to assist with pain and tumor burden when excision is not feasible. Although treatments with DCA can be associated with side effects, including pain, swelling, bruising, erythema, induration, and numbness, all 3 of our patients had ultimate mitigation of pain and reduction in lipoma size within months of the injection. Additional studies should be explored to determine the optimal dose and frequency of administration of DCA that could benefit patients with Dercum disease.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Dercum’s disease. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dercums-disease/.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛drek M, Kramza J, et al. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a review of clinical presentation and management. Reumatologia. 2019;57:281-287. doi:10.5114/reum.2019.89521

- Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:23. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-23

- Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (Lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:17-22. doi:10.1007/s00296-008-0635-3

- Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153. doi:10.2147/JPR.S12351

- Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, et al. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e950. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000950

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary for CID 222528, deoxycholic acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Deoxycholic-acid. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Liu C, Li MK, Alster TS. Alternative cosmetic and medical applications of injectable deoxycholic acid: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1466-1472. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003159

- Santiago-Vázquez M, Michelen-Gómez EA, Carrasquillo-Bonilla D, et al. Intralesional deoxycholic acid: a potential therapeutic alternative for the treatment of lipomas arising in the face. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:112-114. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.037

Dercum disease (or adiposis dolorosa) is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by multiple painful lipomas localized throughout the body.1,2 It typically presents in adults aged 35 to 50 years and is at least 5 times more common in women.3 It often is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, fatigue and weakness.1 There currently are no approved treatments for Dercum disease, only therapies tried with little to no efficacy for symptom management, including analgesics, excision, liposuction,1 lymphatic drainage,4 hypobaric pressure,5 and frequency rhythmic electrical modulation systems.6 For patients who continually develop widespread lesions, surgical excision is not feasible, which poses a therapeutic challenge. Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a bile acid that is approved to treat submental fat, disrupts the integrity of cell membranes, induces adipocyte lysis, and solubilizes fat when injected subcutaneously.7 We used DCA to mitigate pain and reduce lipoma size in patients with Dercum disease, which demonstrated lipoma reduction via ultrasonography in 3 patients.

Case Reports

Three patients presented to clinic with multiple painful subcutaneous nodules throughout several areas of the body and were screened using radiography. Ultrasonography demonstrated numerous lipomas consistent with Dercum disease. The lipomas were measured by ultrasonography to obtain 3-dimensional measurements of each lesion. The most painful lipomas identified by the patients were either treated with 2 mL of DCA (10 mg/mL) or served as a control with no treatment. Patients returned for symptom monitoring and repeat measurements of both treated and untreated lipomas. Two physicians with expertise in ultrasonography measured lesions in a blinded fashion. Photographs were obtained with patient consent.

Patient 1—A 45-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease that was confirmed via ultrasonography. A painful 1.63×1.64×0.55-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the left forearm, and a 1.17×1.26×0.39-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the right wrist. At a follow-up visit 11 months later, 2 mL of DCA was administered to the lipoma on the volar aspect of the left forearm, while the lipoma on the volar aspect of the right wrist was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported 1 week of swelling and tenderness of the treated area. Repeat imaging 4 months after administration of DCA revealed reduction of the treated lesion to 0.80×1.48×0.60 cm and growth of the untreated lesion to 1.32×2.17×0.52 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 34.55%, while the lipoma in the untreated control increased in volume from its original measurement by 111.11% (Table). The patient also reported decreased pain in the treated area at all follow-up visits in the 1 year following the procedure.

Patient 2—A 42-year-old woman with Dercum disease received administration of 2 mL of DCA to a 1.90×1.70×0.90-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh and 2 mL of DCA to a 2.40×3.07×0.60-cm lipoma on the volar aspect of the right forearm 2 weeks later. A 1.18×0.91×0.45-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm was monitored as an untreated control. The patient reported bruising and discoloration a few weeks following the procedure. At subsequent 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, the patient reported induration in the volar aspect of the right forearm and noticeable reduction in size of the lesion in the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported reduction in size of both lesions and improvement of the previously noted side effects. Repeat ultrasonography approximately 6 months after administration of DCA demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh to 0.92×0.96×0.57 cm and the volar aspect of the right forearm to 1.56×2.18×0.79 cm, with growth of the untreated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 1.37×1.11×0.39 cm. The treated lipomas reduced in volume by 68.42% and 41.25%, respectively, and the untreated control increased in volume by 22.08% (Table).

Patient 3—A 75-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease verified by ultrasonography. The patient was administered 2 mL of DCA to a 2.65×3.19×0.71-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm. A 1.66×2.02×0.38-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the right forearm was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported initial swelling that persisted for a few weeks followed by notable pain relief and a decrease in lipoma size. At 2-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain or other adverse effects, while repeat imaging demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 2.13×2.56×0.75 cm and growth of the untreated lesion on the lateral aspect of the right forearm to 1.95×2.05×0.37 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 30.29%, and the untreated control increased in volume by 15.05% (Table).

Comment

Deoxycholic acid is a bile acid naturally found in the body that helps to emulsify and solubilize fats in the intestines. When injected subcutaneously, DCA becomes an adipolytic agent that induces inflammation and targets adipose degradation by macrophages, and it has been manufactured to reduce submental fat.7 Off-label use of DCA has been explored for nonsurgical body contouring and lipomas with promising results in some cases; however, these prior studies have been limited by the lack of quantitative objective measurements to effectively demonstrate the impact of treatment.8,9

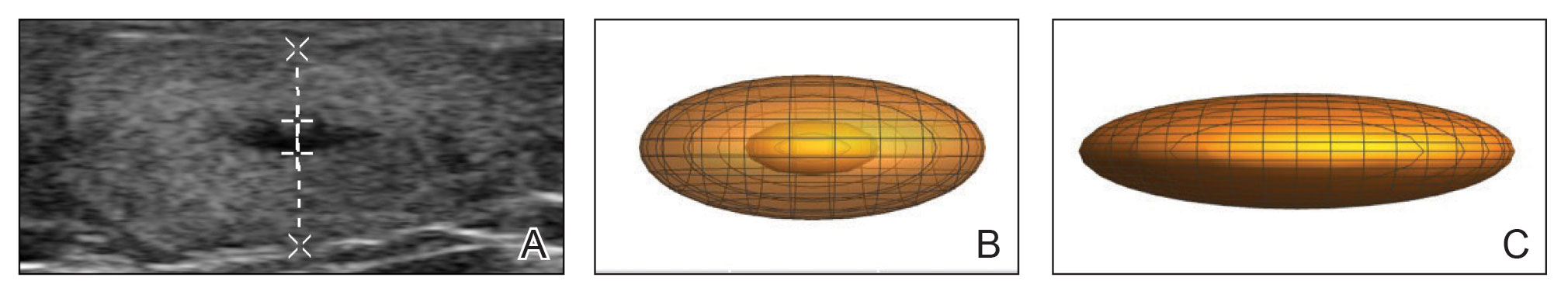

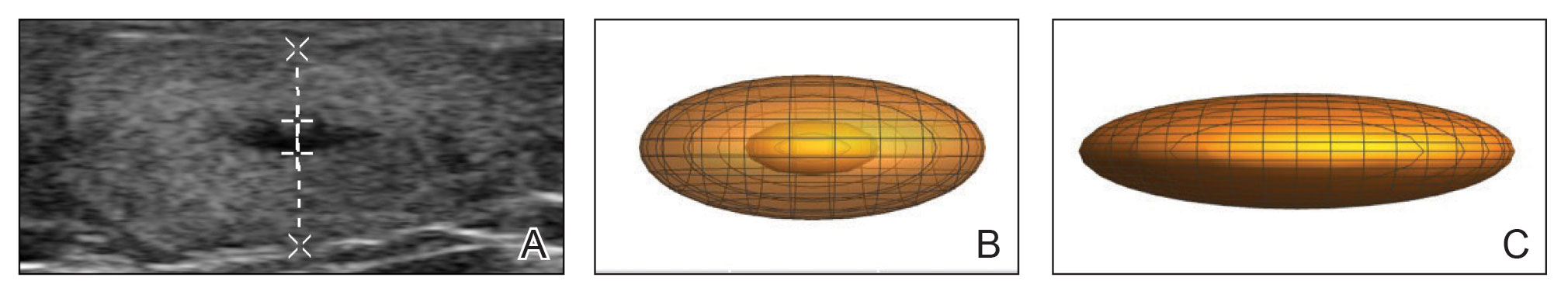

We present 3 patients who requested treatment for numerous painful lipomas. Given the extent of their disease, surgical options were not feasible, and the patients opted to try a nonsurgical alternative. In each case, the painful lipomas that were chosen for treatment were injected with 2 mL of DCA. Injection-associated symptoms included swelling, tenderness, discoloration, and induration, which resolved over a period of months. Patient 1 had a treated lipoma that reduced in volume by approximately 35%, while the control continued to grow and doubled in volume. In patient 2, the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the mid thigh reduced in volume by almost 70%, and the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the right forearm reduced in volume by more than 40%, while the control grew by more than 20%. In patient 3, the volume of the treated lipoma decreased by 30%, and the control increased by 15%. The follow-up interval was shortest in patient 3—2 months as opposed to 11 months and 6 months for patients 1 and 2, respectively; therefore, more progress may be seen in patient 3 with more time. Interestingly, a change in shape of the lipoma was noted in patient 3 (Figure)—an increase in its depth while the center became anechoic, which is a sign of hollowing in the center due to the saponification of fat and a possible cause for the change from an elliptical to a more spherical or doughnutlike shape. Intralesional administration of DCA may offer patients with extensive lipomas, such as those seen in patients with Dercum disease, an alternative, less-invasive option to assist with pain and tumor burden when excision is not feasible. Although treatments with DCA can be associated with side effects, including pain, swelling, bruising, erythema, induration, and numbness, all 3 of our patients had ultimate mitigation of pain and reduction in lipoma size within months of the injection. Additional studies should be explored to determine the optimal dose and frequency of administration of DCA that could benefit patients with Dercum disease.

Dercum disease (or adiposis dolorosa) is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by multiple painful lipomas localized throughout the body.1,2 It typically presents in adults aged 35 to 50 years and is at least 5 times more common in women.3 It often is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, fatigue and weakness.1 There currently are no approved treatments for Dercum disease, only therapies tried with little to no efficacy for symptom management, including analgesics, excision, liposuction,1 lymphatic drainage,4 hypobaric pressure,5 and frequency rhythmic electrical modulation systems.6 For patients who continually develop widespread lesions, surgical excision is not feasible, which poses a therapeutic challenge. Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a bile acid that is approved to treat submental fat, disrupts the integrity of cell membranes, induces adipocyte lysis, and solubilizes fat when injected subcutaneously.7 We used DCA to mitigate pain and reduce lipoma size in patients with Dercum disease, which demonstrated lipoma reduction via ultrasonography in 3 patients.

Case Reports

Three patients presented to clinic with multiple painful subcutaneous nodules throughout several areas of the body and were screened using radiography. Ultrasonography demonstrated numerous lipomas consistent with Dercum disease. The lipomas were measured by ultrasonography to obtain 3-dimensional measurements of each lesion. The most painful lipomas identified by the patients were either treated with 2 mL of DCA (10 mg/mL) or served as a control with no treatment. Patients returned for symptom monitoring and repeat measurements of both treated and untreated lipomas. Two physicians with expertise in ultrasonography measured lesions in a blinded fashion. Photographs were obtained with patient consent.

Patient 1—A 45-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease that was confirmed via ultrasonography. A painful 1.63×1.64×0.55-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the left forearm, and a 1.17×1.26×0.39-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the right wrist. At a follow-up visit 11 months later, 2 mL of DCA was administered to the lipoma on the volar aspect of the left forearm, while the lipoma on the volar aspect of the right wrist was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported 1 week of swelling and tenderness of the treated area. Repeat imaging 4 months after administration of DCA revealed reduction of the treated lesion to 0.80×1.48×0.60 cm and growth of the untreated lesion to 1.32×2.17×0.52 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 34.55%, while the lipoma in the untreated control increased in volume from its original measurement by 111.11% (Table). The patient also reported decreased pain in the treated area at all follow-up visits in the 1 year following the procedure.

Patient 2—A 42-year-old woman with Dercum disease received administration of 2 mL of DCA to a 1.90×1.70×0.90-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh and 2 mL of DCA to a 2.40×3.07×0.60-cm lipoma on the volar aspect of the right forearm 2 weeks later. A 1.18×0.91×0.45-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm was monitored as an untreated control. The patient reported bruising and discoloration a few weeks following the procedure. At subsequent 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, the patient reported induration in the volar aspect of the right forearm and noticeable reduction in size of the lesion in the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported reduction in size of both lesions and improvement of the previously noted side effects. Repeat ultrasonography approximately 6 months after administration of DCA demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh to 0.92×0.96×0.57 cm and the volar aspect of the right forearm to 1.56×2.18×0.79 cm, with growth of the untreated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 1.37×1.11×0.39 cm. The treated lipomas reduced in volume by 68.42% and 41.25%, respectively, and the untreated control increased in volume by 22.08% (Table).

Patient 3—A 75-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease verified by ultrasonography. The patient was administered 2 mL of DCA to a 2.65×3.19×0.71-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm. A 1.66×2.02×0.38-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the right forearm was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported initial swelling that persisted for a few weeks followed by notable pain relief and a decrease in lipoma size. At 2-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain or other adverse effects, while repeat imaging demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 2.13×2.56×0.75 cm and growth of the untreated lesion on the lateral aspect of the right forearm to 1.95×2.05×0.37 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 30.29%, and the untreated control increased in volume by 15.05% (Table).

Comment

Deoxycholic acid is a bile acid naturally found in the body that helps to emulsify and solubilize fats in the intestines. When injected subcutaneously, DCA becomes an adipolytic agent that induces inflammation and targets adipose degradation by macrophages, and it has been manufactured to reduce submental fat.7 Off-label use of DCA has been explored for nonsurgical body contouring and lipomas with promising results in some cases; however, these prior studies have been limited by the lack of quantitative objective measurements to effectively demonstrate the impact of treatment.8,9

We present 3 patients who requested treatment for numerous painful lipomas. Given the extent of their disease, surgical options were not feasible, and the patients opted to try a nonsurgical alternative. In each case, the painful lipomas that were chosen for treatment were injected with 2 mL of DCA. Injection-associated symptoms included swelling, tenderness, discoloration, and induration, which resolved over a period of months. Patient 1 had a treated lipoma that reduced in volume by approximately 35%, while the control continued to grow and doubled in volume. In patient 2, the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the mid thigh reduced in volume by almost 70%, and the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the right forearm reduced in volume by more than 40%, while the control grew by more than 20%. In patient 3, the volume of the treated lipoma decreased by 30%, and the control increased by 15%. The follow-up interval was shortest in patient 3—2 months as opposed to 11 months and 6 months for patients 1 and 2, respectively; therefore, more progress may be seen in patient 3 with more time. Interestingly, a change in shape of the lipoma was noted in patient 3 (Figure)—an increase in its depth while the center became anechoic, which is a sign of hollowing in the center due to the saponification of fat and a possible cause for the change from an elliptical to a more spherical or doughnutlike shape. Intralesional administration of DCA may offer patients with extensive lipomas, such as those seen in patients with Dercum disease, an alternative, less-invasive option to assist with pain and tumor burden when excision is not feasible. Although treatments with DCA can be associated with side effects, including pain, swelling, bruising, erythema, induration, and numbness, all 3 of our patients had ultimate mitigation of pain and reduction in lipoma size within months of the injection. Additional studies should be explored to determine the optimal dose and frequency of administration of DCA that could benefit patients with Dercum disease.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Dercum’s disease. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dercums-disease/.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛drek M, Kramza J, et al. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a review of clinical presentation and management. Reumatologia. 2019;57:281-287. doi:10.5114/reum.2019.89521

- Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:23. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-23

- Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (Lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:17-22. doi:10.1007/s00296-008-0635-3

- Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153. doi:10.2147/JPR.S12351

- Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, et al. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e950. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000950

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary for CID 222528, deoxycholic acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Deoxycholic-acid. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Liu C, Li MK, Alster TS. Alternative cosmetic and medical applications of injectable deoxycholic acid: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1466-1472. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003159

- Santiago-Vázquez M, Michelen-Gómez EA, Carrasquillo-Bonilla D, et al. Intralesional deoxycholic acid: a potential therapeutic alternative for the treatment of lipomas arising in the face. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:112-114. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.037

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Dercum’s disease. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dercums-disease/.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛drek M, Kramza J, et al. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a review of clinical presentation and management. Reumatologia. 2019;57:281-287. doi:10.5114/reum.2019.89521

- Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:23. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-23

- Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (Lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:17-22. doi:10.1007/s00296-008-0635-3

- Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153. doi:10.2147/JPR.S12351

- Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, et al. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e950. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000950

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary for CID 222528, deoxycholic acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Deoxycholic-acid. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Liu C, Li MK, Alster TS. Alternative cosmetic and medical applications of injectable deoxycholic acid: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1466-1472. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003159

- Santiago-Vázquez M, Michelen-Gómez EA, Carrasquillo-Bonilla D, et al. Intralesional deoxycholic acid: a potential therapeutic alternative for the treatment of lipomas arising in the face. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:112-114. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.037

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should consider Dercum disease when encountering a patient with numerous painful lipomas.

- Subcutaneous administration of deoxycholic acid resulted in a notable reduction in pain and size of lipomas by 30% to 68% per radiographic review.

- Deoxycholic acid may provide an alternative therapeutic option for patients who have Dercum disease with substantial tumor burden.

Napping and AFib risk: The long and the short of it

Napping for more than half an hour during the day was associated with a 90% increased risk of atrial fibrillation (AFib), but shorter naps were linked to a reduced risk, based on data from more than 20,000 individuals.

“Short daytime napping is a common, healthy habit, especially in Mediterranean countries,” Jesus Diaz-Gutierrez, MD, of Juan Ramon Jimenez University Hospital, Huelva, Spain, said in a presentation at the annual congress of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC).

Previous studies have shown a potential link between sleep patterns and AFib risk, but the association between specific duration of daytime naps and AFib risk has not been explored, he said.

Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez and colleagues used data from the University of Navarra Follow-up (SUN) Project, a prospective cohort of Spanish university graduates, to explore the possible link between naps and AFib. The study population included 20,348 individuals without AFib at baseline who were followed for a median of 13.8 years. The average age of participants at baseline was 38 years; 61% were women.

Daytime napping patterns were assessed at baseline, and participants were divided into nap groups of short nappers (defined as less than 30 minutes per day), and longer nappers (30 minutes or more per day), and those who reported no napping.

The researchers identified 131 incident cases of AFib during the follow-up period. Overall, the relative risk of incident AFib was significantly higher for the long nappers (adjusted hazard ratio 1.90) compared with short nappers in a multivariate analysis, while no significant risk appeared among non-nappers compared to short nappers (aHR 1.26).

The researchers then excluded the non-nappers in a secondary analysis to explore the impact of more specific daily nap duration on AFib risk. In a multivariate analysis, they found a 42% reduced risk of AF among those who napped for less than 15 minutes, and a 56% reduced risk for those who napped for 15-30 minutes, compared with those who napped for more than 30 minutes (aHR 0.56 and 0.42, respectively).

Potential explanations for the associations include the role of circadian rhythms, Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez said in a press release accompanying the presentation at the meeting. “Long daytime naps may disrupt the body’s internal clock (circadian rhythm), leading to shorter nighttime sleep, more nocturnal awakening, and reduced physical activity. In contrast, short daytime napping may improve circadian rhythm, lower blood pressure levels, and reduce stress.” More research is needed to validate the findings and the optimum nap duration, and whether a short nap is more advantageous than not napping in terms of AFib risk reduction, he said.

The study results suggest that naps of 15-30 minutes represent “a potential novel healthy lifestyle habit in the primary prevention of AFib,” Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez said in his presentation. However, the results also suggest that daily naps be limited to less than 30 minutes, he concluded.

Sleep habits may serve as red flag

“As we age, most if not all of us will develop sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and other sleep issues,” Lawrence S. Rosenthal, MD, of the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, said in an interview.

Therefore, “this study is near and dear to most people, and most would agree that poor sleeping habits affect our health.” In particular, OSA has been linked to AFib, although that was not measured in the current study, he added.

Dr. Rosenthal said he was not surprised by the current study findings. “It seems that a quick recharge of your ‘battery’ during the day is healthier than a long, deep sleep daytime nap,” he said. In addition, “Longer naps may be a marker of OSA,” he noted.

For clinicians, the take-home message of the current study is the need to consider underlying medical conditions in patients who regularly take long afternoon naps, and to consider these longer naps as a potential marker for AFib, said Dr. Rosenthal.

Looking ahead, a “deeper dive into the makeup of the populations studied” would be useful as a foundation for additional research, he said.

The SUN Project disclosed funding from the Spanish Government-Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), the Navarra Regional Government, Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas, the University of Navarra, and the European Research Council. The researchers, and Dr. Rosenthal, had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Napping for more than half an hour during the day was associated with a 90% increased risk of atrial fibrillation (AFib), but shorter naps were linked to a reduced risk, based on data from more than 20,000 individuals.

“Short daytime napping is a common, healthy habit, especially in Mediterranean countries,” Jesus Diaz-Gutierrez, MD, of Juan Ramon Jimenez University Hospital, Huelva, Spain, said in a presentation at the annual congress of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC).

Previous studies have shown a potential link between sleep patterns and AFib risk, but the association between specific duration of daytime naps and AFib risk has not been explored, he said.

Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez and colleagues used data from the University of Navarra Follow-up (SUN) Project, a prospective cohort of Spanish university graduates, to explore the possible link between naps and AFib. The study population included 20,348 individuals without AFib at baseline who were followed for a median of 13.8 years. The average age of participants at baseline was 38 years; 61% were women.

Daytime napping patterns were assessed at baseline, and participants were divided into nap groups of short nappers (defined as less than 30 minutes per day), and longer nappers (30 minutes or more per day), and those who reported no napping.

The researchers identified 131 incident cases of AFib during the follow-up period. Overall, the relative risk of incident AFib was significantly higher for the long nappers (adjusted hazard ratio 1.90) compared with short nappers in a multivariate analysis, while no significant risk appeared among non-nappers compared to short nappers (aHR 1.26).

The researchers then excluded the non-nappers in a secondary analysis to explore the impact of more specific daily nap duration on AFib risk. In a multivariate analysis, they found a 42% reduced risk of AF among those who napped for less than 15 minutes, and a 56% reduced risk for those who napped for 15-30 minutes, compared with those who napped for more than 30 minutes (aHR 0.56 and 0.42, respectively).

Potential explanations for the associations include the role of circadian rhythms, Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez said in a press release accompanying the presentation at the meeting. “Long daytime naps may disrupt the body’s internal clock (circadian rhythm), leading to shorter nighttime sleep, more nocturnal awakening, and reduced physical activity. In contrast, short daytime napping may improve circadian rhythm, lower blood pressure levels, and reduce stress.” More research is needed to validate the findings and the optimum nap duration, and whether a short nap is more advantageous than not napping in terms of AFib risk reduction, he said.

The study results suggest that naps of 15-30 minutes represent “a potential novel healthy lifestyle habit in the primary prevention of AFib,” Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez said in his presentation. However, the results also suggest that daily naps be limited to less than 30 minutes, he concluded.

Sleep habits may serve as red flag

“As we age, most if not all of us will develop sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and other sleep issues,” Lawrence S. Rosenthal, MD, of the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, said in an interview.

Therefore, “this study is near and dear to most people, and most would agree that poor sleeping habits affect our health.” In particular, OSA has been linked to AFib, although that was not measured in the current study, he added.

Dr. Rosenthal said he was not surprised by the current study findings. “It seems that a quick recharge of your ‘battery’ during the day is healthier than a long, deep sleep daytime nap,” he said. In addition, “Longer naps may be a marker of OSA,” he noted.

For clinicians, the take-home message of the current study is the need to consider underlying medical conditions in patients who regularly take long afternoon naps, and to consider these longer naps as a potential marker for AFib, said Dr. Rosenthal.

Looking ahead, a “deeper dive into the makeup of the populations studied” would be useful as a foundation for additional research, he said.

The SUN Project disclosed funding from the Spanish Government-Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), the Navarra Regional Government, Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas, the University of Navarra, and the European Research Council. The researchers, and Dr. Rosenthal, had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Napping for more than half an hour during the day was associated with a 90% increased risk of atrial fibrillation (AFib), but shorter naps were linked to a reduced risk, based on data from more than 20,000 individuals.

“Short daytime napping is a common, healthy habit, especially in Mediterranean countries,” Jesus Diaz-Gutierrez, MD, of Juan Ramon Jimenez University Hospital, Huelva, Spain, said in a presentation at the annual congress of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC).

Previous studies have shown a potential link between sleep patterns and AFib risk, but the association between specific duration of daytime naps and AFib risk has not been explored, he said.

Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez and colleagues used data from the University of Navarra Follow-up (SUN) Project, a prospective cohort of Spanish university graduates, to explore the possible link between naps and AFib. The study population included 20,348 individuals without AFib at baseline who were followed for a median of 13.8 years. The average age of participants at baseline was 38 years; 61% were women.

Daytime napping patterns were assessed at baseline, and participants were divided into nap groups of short nappers (defined as less than 30 minutes per day), and longer nappers (30 minutes or more per day), and those who reported no napping.

The researchers identified 131 incident cases of AFib during the follow-up period. Overall, the relative risk of incident AFib was significantly higher for the long nappers (adjusted hazard ratio 1.90) compared with short nappers in a multivariate analysis, while no significant risk appeared among non-nappers compared to short nappers (aHR 1.26).

The researchers then excluded the non-nappers in a secondary analysis to explore the impact of more specific daily nap duration on AFib risk. In a multivariate analysis, they found a 42% reduced risk of AF among those who napped for less than 15 minutes, and a 56% reduced risk for those who napped for 15-30 minutes, compared with those who napped for more than 30 minutes (aHR 0.56 and 0.42, respectively).

Potential explanations for the associations include the role of circadian rhythms, Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez said in a press release accompanying the presentation at the meeting. “Long daytime naps may disrupt the body’s internal clock (circadian rhythm), leading to shorter nighttime sleep, more nocturnal awakening, and reduced physical activity. In contrast, short daytime napping may improve circadian rhythm, lower blood pressure levels, and reduce stress.” More research is needed to validate the findings and the optimum nap duration, and whether a short nap is more advantageous than not napping in terms of AFib risk reduction, he said.

The study results suggest that naps of 15-30 minutes represent “a potential novel healthy lifestyle habit in the primary prevention of AFib,” Dr. Diaz-Gutierrez said in his presentation. However, the results also suggest that daily naps be limited to less than 30 minutes, he concluded.

Sleep habits may serve as red flag

“As we age, most if not all of us will develop sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and other sleep issues,” Lawrence S. Rosenthal, MD, of the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, said in an interview.

Therefore, “this study is near and dear to most people, and most would agree that poor sleeping habits affect our health.” In particular, OSA has been linked to AFib, although that was not measured in the current study, he added.

Dr. Rosenthal said he was not surprised by the current study findings. “It seems that a quick recharge of your ‘battery’ during the day is healthier than a long, deep sleep daytime nap,” he said. In addition, “Longer naps may be a marker of OSA,” he noted.

For clinicians, the take-home message of the current study is the need to consider underlying medical conditions in patients who regularly take long afternoon naps, and to consider these longer naps as a potential marker for AFib, said Dr. Rosenthal.

Looking ahead, a “deeper dive into the makeup of the populations studied” would be useful as a foundation for additional research, he said.

The SUN Project disclosed funding from the Spanish Government-Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), the Navarra Regional Government, Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas, the University of Navarra, and the European Research Council. The researchers, and Dr. Rosenthal, had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM ESC PREVENTIVE CARDIOLOGY 2023

Most adults, more than one in three children take dietary supplements: Report

The new figures continue a 15-year trend of small, steady increases in how many people in the United States use the products that can deliver essential nutrients, but their usage includes a risk of getting more nutrients than recommended. In 2007, 48% of adults took supplements, and that figure has reached nearly 59% in this latest count.

The new report looked at whether people took a multivitamin, as well as other more specific supplements. Among children and adolescents aged 19 and under, 23.5% took a multivitamin, while 31.5% of adults reported taking one. The most common specialized supplement that people took was vitamin D.

The report, released by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, compiled survey data from 2017 through 2020 in which 15,548 people reported their household’s usage of dietary supplements. Dietary supplements include vitamins, minerals, herbs, or other botanicals that are taken by mouth in pill, capsule, tablet, or liquid form. The researchers said the vitamin and supplement market is large and growing, totaling $55.7 billion in sales in 2020.

More than one-third of adults (36%) reported taking more than one supplement, and one in four people aged 60 and older said they took four or more.

The data showed demographic trends in who uses dietary supplements. Women and girls were more likely to take supplements than men and boys, although there were similar usage levels for both genders among 1- to 2-year-olds. People with higher education or income levels were more likely to use supplements. Asian people and White people were more likely to take supplements, compared with Hispanic people and Black people.

The authors wrote that monitoring trends in supplement use is important because the products “contribute substantially to nutrient intake as well as increase the risk of excessive intake of certain micronutrients.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The new figures continue a 15-year trend of small, steady increases in how many people in the United States use the products that can deliver essential nutrients, but their usage includes a risk of getting more nutrients than recommended. In 2007, 48% of adults took supplements, and that figure has reached nearly 59% in this latest count.

The new report looked at whether people took a multivitamin, as well as other more specific supplements. Among children and adolescents aged 19 and under, 23.5% took a multivitamin, while 31.5% of adults reported taking one. The most common specialized supplement that people took was vitamin D.

The report, released by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, compiled survey data from 2017 through 2020 in which 15,548 people reported their household’s usage of dietary supplements. Dietary supplements include vitamins, minerals, herbs, or other botanicals that are taken by mouth in pill, capsule, tablet, or liquid form. The researchers said the vitamin and supplement market is large and growing, totaling $55.7 billion in sales in 2020.

More than one-third of adults (36%) reported taking more than one supplement, and one in four people aged 60 and older said they took four or more.

The data showed demographic trends in who uses dietary supplements. Women and girls were more likely to take supplements than men and boys, although there were similar usage levels for both genders among 1- to 2-year-olds. People with higher education or income levels were more likely to use supplements. Asian people and White people were more likely to take supplements, compared with Hispanic people and Black people.

The authors wrote that monitoring trends in supplement use is important because the products “contribute substantially to nutrient intake as well as increase the risk of excessive intake of certain micronutrients.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The new figures continue a 15-year trend of small, steady increases in how many people in the United States use the products that can deliver essential nutrients, but their usage includes a risk of getting more nutrients than recommended. In 2007, 48% of adults took supplements, and that figure has reached nearly 59% in this latest count.

The new report looked at whether people took a multivitamin, as well as other more specific supplements. Among children and adolescents aged 19 and under, 23.5% took a multivitamin, while 31.5% of adults reported taking one. The most common specialized supplement that people took was vitamin D.

The report, released by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, compiled survey data from 2017 through 2020 in which 15,548 people reported their household’s usage of dietary supplements. Dietary supplements include vitamins, minerals, herbs, or other botanicals that are taken by mouth in pill, capsule, tablet, or liquid form. The researchers said the vitamin and supplement market is large and growing, totaling $55.7 billion in sales in 2020.

More than one-third of adults (36%) reported taking more than one supplement, and one in four people aged 60 and older said they took four or more.

The data showed demographic trends in who uses dietary supplements. Women and girls were more likely to take supplements than men and boys, although there were similar usage levels for both genders among 1- to 2-year-olds. People with higher education or income levels were more likely to use supplements. Asian people and White people were more likely to take supplements, compared with Hispanic people and Black people.

The authors wrote that monitoring trends in supplement use is important because the products “contribute substantially to nutrient intake as well as increase the risk of excessive intake of certain micronutrients.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Scattered Red-Brown, Centrally Violaceous, Blanching Papules on an Infant

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

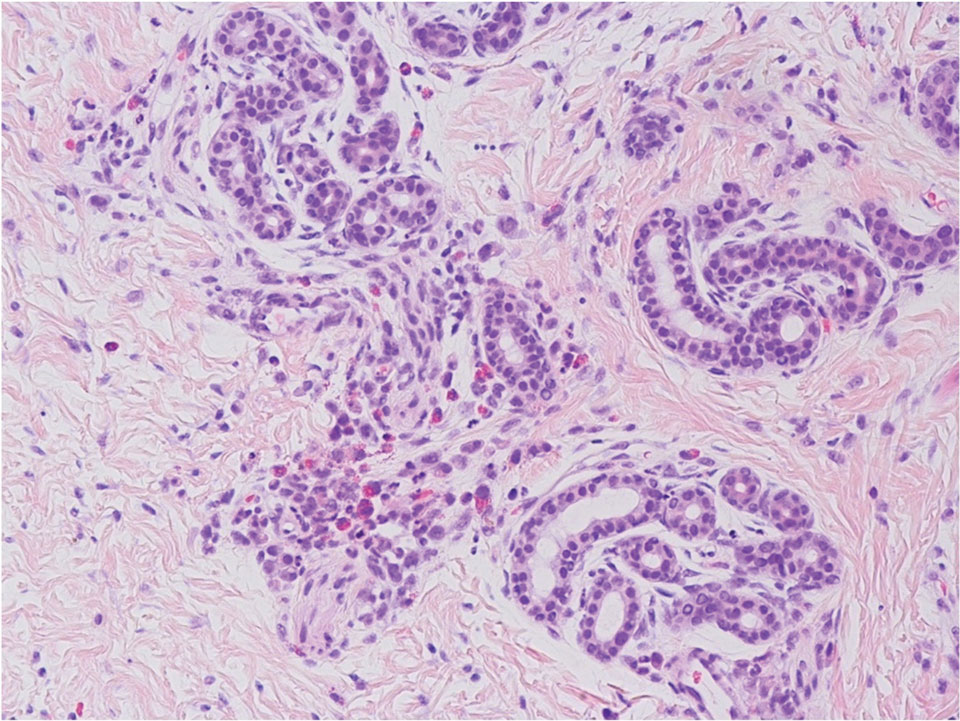

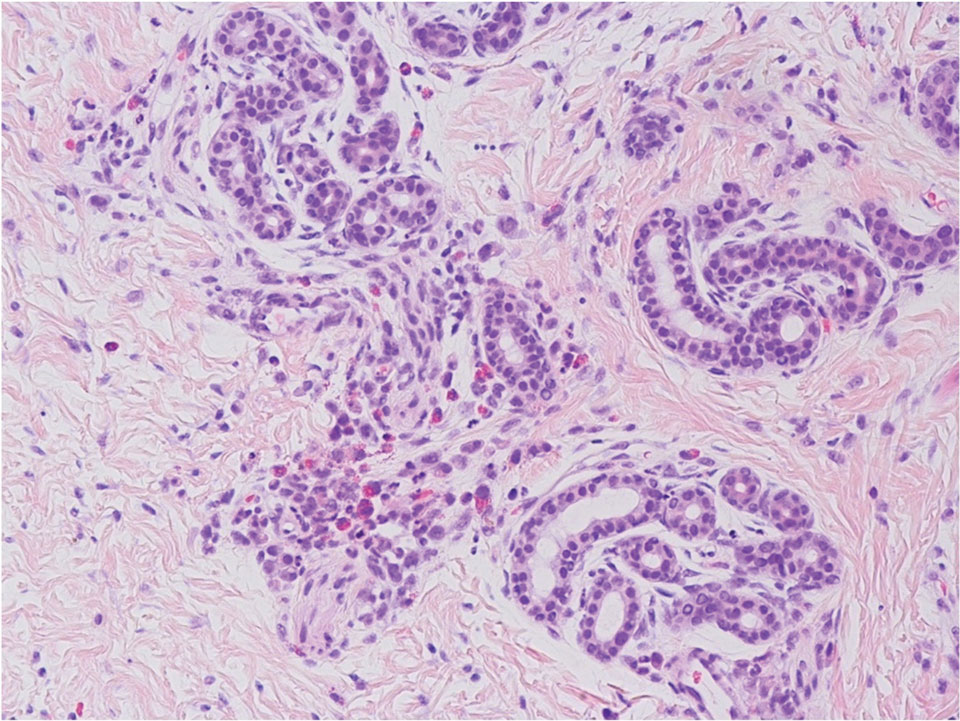

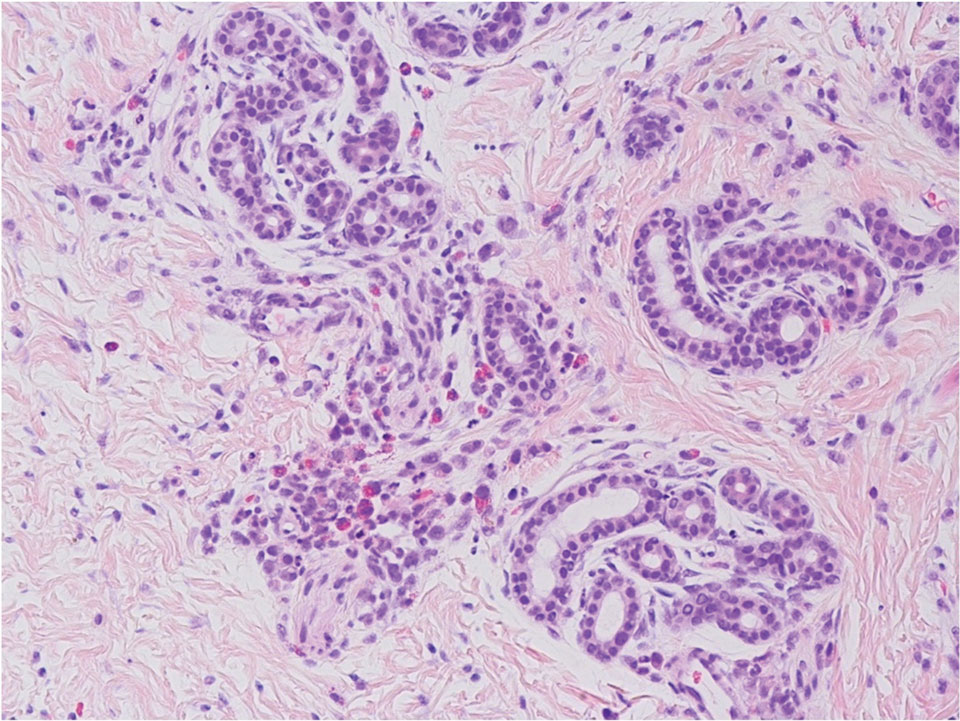

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5

Genetic testing, skin biopsies, ophthalmic examinations, neuroimaging, joint radiography, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and hearing examinations can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis and evaluation of systemic complications.4 A skin biopsy may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate. Ophthalmic examination can demonstrate uveitis and optic disk edema. Neuroimaging may reveal cerebral atrophy or ventricular dilation. Lastly, joint radiography can be used to evaluate for the presence of premature long bone ossification or osseous overgrowth.4

In summary, NOMID is a multisystemic disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Early recognition of this entity is important given the severe sequelae and available efficacious therapy. Dermatologists should be aware of these manifestations, as dermatologic consultation and a skin biopsy may aid in diagnosis.

- Lachmann HJ. Periodic fever syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:596-609. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2017.12.001

- Hull KM, Shoham N, Jin Chae J, et al. The expanding spectrum of systemic autoinflammatory disorders and their rheumatic manifestations. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:61-69. doi:10.1097/00002281-200301000-00011

- Ahmadi N, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, et al. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: otolaryngologic and audiologic manifestations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:295-302. doi:10.1177/0194599811402296

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Ozen S, Tyrrell PN, et al. Diagnostic criteria for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:942-947. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209686

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrinassociated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:3340-3348. doi:10.1002/art.10688

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5

Genetic testing, skin biopsies, ophthalmic examinations, neuroimaging, joint radiography, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and hearing examinations can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis and evaluation of systemic complications.4 A skin biopsy may reveal a neutrophilic infiltrate. Ophthalmic examination can demonstrate uveitis and optic disk edema. Neuroimaging may reveal cerebral atrophy or ventricular dilation. Lastly, joint radiography can be used to evaluate for the presence of premature long bone ossification or osseous overgrowth.4

In summary, NOMID is a multisystemic disorder with cutaneous manifestations. Early recognition of this entity is important given the severe sequelae and available efficacious therapy. Dermatologists should be aware of these manifestations, as dermatologic consultation and a skin biopsy may aid in diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Neonatal-Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disorder (NOMID)

The punch biopsy demonstrated a predominantly deep but somewhat superficial, periadnexal, neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrate (Figure). The eruption resolved 3 days later with supportive treatment, including appropriate wound care. Genetic analysis revealed an autosomal-dominant NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 gene, NLRP3, de novo variant associated with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disorder (NOMID). Additional workup to characterize our patient’s inflammatory profile revealed elevated IL-18, CD3, CD4, S100A12, and S100A8/A9 levels. On day 48 of life, she was started on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, at a dose of 1 mg/kg subcutaneously, which eventually was titrated to 10 mg/kg at hospital discharge. Hearing screenings were within normal limits.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) consist of 3 rare, IL-1–associated, autoinflammatory disorders, including familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and NOMID (also known as chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous and articular syndrome). These conditions result from a sporadic or autosomal-dominant gain-of-function mutations in a single gene, NLRP3, on chromosome 1q44. NLRP3 encodes for cryopyrin, an important component of an IL-1 and IL-18 activating inflammasome.1 The most severe manifestation of CAPS is NOMID, which typically presents at birth as a migratory urticarial eruption, growth failure, myalgia, fever, and abnormal facial features, including frontal bossing, saddle-shaped nose, and protruding eyes.2 The illness also can manifest with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, uveitis, sensorineural hearing loss, cerebral atrophy, and other neurologic manifestations.3 A diagnosis of chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome was less likely given that our patient remained afebrile and did not show signs of lipodystrophy and persistent violaceous eyelid swelling. Both FCAS and MWS are less severe forms of CAPS when compared to NOMID. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome was less likely given the absence of the typical periodic fever pattern associated with the condition and severity of our patient’s symptoms. Muckle-Wells syndrome typically presents in adolescence with symptoms of FCAS, painful urticarial plaques, and progressive sensorinueral hearing loss. Tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic fever (TRAPS) usually is associated with episodic fevers, abdominal pain, periorbital edema, migratory erythema, and arthralgia.1,3,4

Diagnostic criteria for CAPS include elevated inflammatory markers and serum amyloid, plus at least 2 of the typical CAPS symptoms: urticarial rash, cold-triggered episodes, sensorineural hearing loss, musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities.4 The sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic criteria are 84% and 91%, respectively. Additional findings that can be seen but are not part of the diagnostic criteria include intermittent fever, transient joint swelling, bony overgrowths, uveitis, optic disc edema, impaired growth, and hepatosplenomegaly.5 Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, eosinophilia, anemia, and/or thrombocytopenia.3,5