User login

Sports: An underutilized tool for patients with disabilities

Approximately 6.5 million people in the United States have an intellectual disability, the most common type of developmental disability.1 People with disabilities are 3 times more likely to have heart disease, stroke, or diabetes than adults without disabilities.2

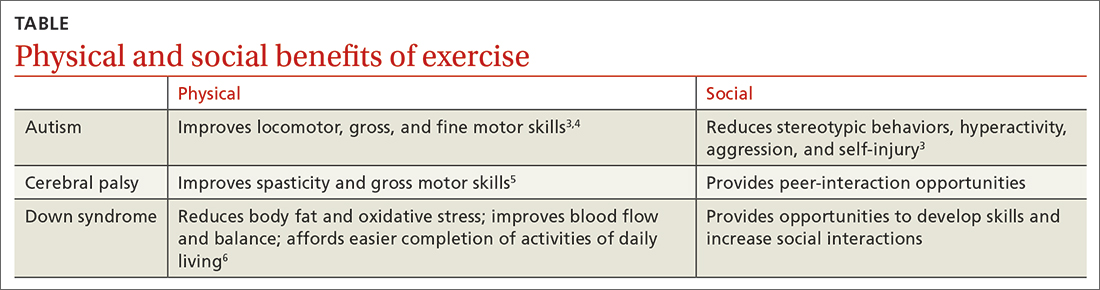

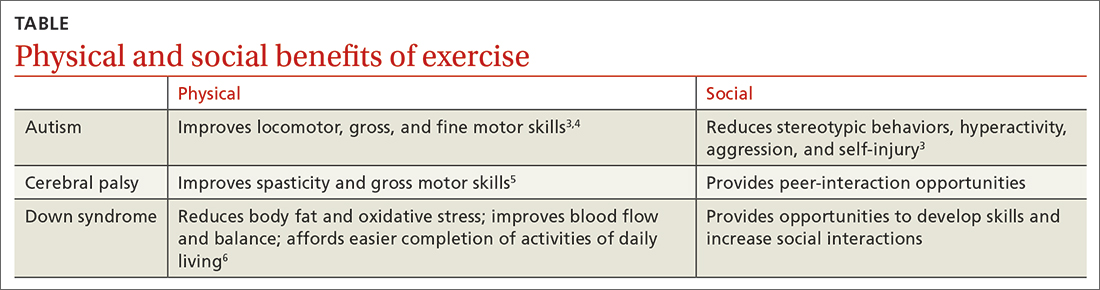

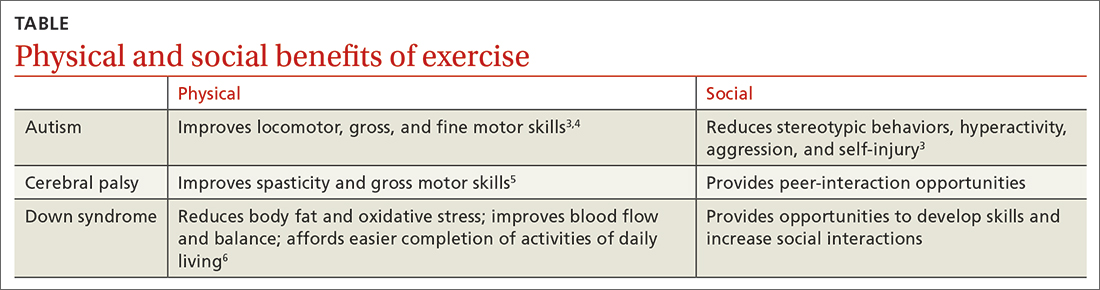

Sports as a treatment modality are not used to full advantage to combat these conditions in people with intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDDs). Participation in sport activities can lead to weight loss, reduce risk for cardiovascular disease, and optimize physical health. Sports also can help enhance social and communication skills and improve quality of life for this patient population (TABLE).3-6

However, a 2014 report found that while inactive adults with disabilities (hearing, vision, cognition, mobility) were 50% more likely to report 1 or more chronic diseases than those who were physically active, only 44% of adults with disabilities who visited a health professional in the previous 12 months received a physical activity recommendation.7 In addition, more than 50% of adults with disabilities are not meeting US recommended exercise guidelines.7-9

Family physicians may not feel they have adequate training to counsel patients with IDDs. Additional limiting factors include dependence on caregivers for exercise participation, expense, transportation difficulties, a lack of choice in sporting activities, and the patient’s level of motivation.10The guidance reviewed here details how to modify the pre-participation sports physical exam specifically for patients with IDDs. It also provides sport and exercise recommendations for patients with 3 disabilities: Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and autism spectrum disorder.

Worth noting: As is true for adults without disabilities, those with IDDs should participate in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity, aerobic physical activity each week.9 Recommend muscle-strengthening activities be performed at least 2 days each week.9

Exercise recommendations for patients with Down syndrome

One in every 700 babies receives a diagnosis of Down syndrome.11 Among its many possible manifestations—which include intellectual disability, heart disease, and diabetes—Down syndrome is associated with an increased risk for obesity, which makes exercise an extremely important lifestyle modification for these patients. Obesity can lead to obstructive sleep apnea causing cor pulmonale and even premature death. Continuous positive airway pressure intervention can be difficult in terms of patient compliance. However, weight loss through exercise and sports is an effective intervention to mitigate these obesity-related health comorbidities.

Pre-participation exam. A focused history and physical exam are often conducted before a patient engages in organized competitive or recreational sports. The pre-participation sports physical exam typically focuses on cardiac, neurologic, hereditary, and musculoskeletal disorders. While we recommend including these baseline elements as part of the exam for patients with disabilities, we also recommend modifying the exam to include disability-specific screening for associated comorbidities.

Continue to: For patients with Down syndrome...

For patients with Down syndrome, a complete pre-participation sports physical exam is warranted. Inquire specifically about neck pain or dislocations, heart murmur, cardiac surgery, seizures, sleep issues, history of congenital abdominal defect, hematologic malignancy, and bone pain as part of the focused physical exam.

Look for evidence of patellofemoral instability, pes planus, scoliosis, hallux deformities, decreased muscle tone, and muscular weakness. Check for cataracts and perform a thorough cardiovascular exam to assess for murmur or signs of chronic hypoxia, such as cyanosis. If a heart murmur is detected, refer the patient to a cardiologist.

Patients with Down syndrome are also at increased risk for atlantoaxial instability. A thorough neurologic evaluation to screen for this condition is indicated; however, routine radiologic screening is not needed.12

An annual complete blood cell count and thyroid-stimulating hormone test are recommended for all children with Down syndrome.13 For patients with Down syndrome who are 13 to 21 years of age, an echocardiogram also is recommended for concerning symptoms.13 Ferritin levels also should be assessed annually for patients who are younger than 13 years of age to check for iron-deficiency anemia.13Consider high-risk screening strategies for patients with diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

Special considerations. Patients with Down syndrome were found to be injured more frequently than individuals with other disabilities during the Special Olympics.14 These patients may be hypersensitive to pain with prolonged pain responses, or unable to verbally communicate their pain or injury.15

Continue to: The complexity of pain assessment...

The complexity of pain assessment in patients with Down syndrome may increase the difficulty of accurately diagnosing an injury, leading to underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis. To increase accuracy of pain assessment in this setting, we recommend using the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale or a numeric pain rating scale in verbal patients.15 In nonverbal patients, facial expressions are reliable indicators of pain.

Which exercise? Healthy patients with Down syndrome can participate in any sport. Aerobic exercise can help lower body fat, reduce oxidative stress, and improve blood flow.6 Muscle-strengthening exercises can lead to improved daily functioning and balance. Strength training and aerobic exercise benefit aging patients with Down syndrome who are struggling with obesity. Such exercise also helps increase bone mineral density and improve cardiovascular fitness, especially when initiated at a young age. Consistent exercise promotes positive health outcomes throughout the lifespan.16

Exercise recommendations for patients with cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy, the most common motor disability in children, is associated with intellectual disability, seizures, respiratory insufficiency, scoliosis, osteoporosis, mood disorders, dysphagia, and speech and hearing impairment.17 The increasing survival of premature babies born with cerebral palsy and the growing prevalence of adults with the condition point to the importance of expanding one’s knowledge of how best to care for this population.18

Pre-participation exam. In addition to a complete sport physical exam, it’s important to further evaluate patients with cerebral palsy for epilepsy, joint contractures, muscle weakness, spinal deformities, and respiratory insufficiency. The Gross Motor Function Classification system, commonly used for patients with cerebral palsy, scores functional ability in 5 levels.18 Patients at Level I are the most mobile; patients at Level V need wheelchair transport in all settings.

Further evaluation of spinal deformities can be initiated with x-ray screening. Consider ordering dual x-ray absorptiometry scans to evaluate bone mass.17

Continue to: Special considerations

Special considerations. Patients with cerebral palsy have a heightened risk for depression and anxiety.19 Mental health can be assessed via the General Anxiety Disorder-7, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions tools, among others. Mental health screening may need to be adjusted depending on the patient’s level of cognition and ability to communicate. The patient’s caregiver also can provide supplemental information.

Consider screening vitamin D levels in patients with cerebral palsy. Approximately 50% of adults with cerebral palsy are vitamin D–deficient secondary to sedentary behavior and lack of sun exposure.20-22

Optimal medical management has been shown to decrease muscle spasticity and may be beneficial before initiating an exercise program. For patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms, referral for physical therapy to further improve gross motor function and spasticity may be required before initiating an exercise program.

Which exercise? Individuals with cerebral palsy spend 76% to 99% of their waking hours being sedentary.5 Consequently, they typically have decreased cardiorespiratory endurance and decreased muscle strength. Strength training may improve muscle spasticity, gross motor function, joint health, and respiratory insufficiency.5 Even in those who function at Level IV-V of the Gross Motor Function Classification system, exercise reduces vertebral fractures and improves time spent standing.23 By improving endurance, spasticity, and strength with exercise, deconditioning can be mitigated.

Involvement in sports promotes peer interactions, personal interests, and positive self-identity. It can give a newfound passion for life. Additionally, families of children with disabilities who engage in leisure activities together have less caregiver burden.24,25 Sporting activities offer a way to optimize psychosocial well-being for the patient and the entire family.

Continue to: Dance promotes functionality...

Dance promotes functionality and psychosocial adjustment.26 Hippotherapy, defined as therapy and rehabilitation during which the patient interacts with horses, can diminish muscle spasticity.27 Aquatic therapy also may increase muscle strength.28

Sports for patients with autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder is defined as persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction that are usually evident in the first 3 years of life.29 Autism can manifest with or without intellectual or language impairment. Patients with autism commonly have difficulty processing sensory stimuli and can experience “sensory overload.” More than half have a coexisting mental health disorder, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder.30

Aversions to foods and food selectivity, as well as adverse effects from medical treatment of autism-related agitation, result in a higher incidence of obesity in patients with autism.31,32

Pre-participation exam. In addition to a comprehensive pre-participation exam, the Autism Spectrum Syndrome Questionnaire (ASSQ) and Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers are tools to screen school-age children with normal cognition to mild intellectual disability.33 These questionnaires have limitations, however. For example, ASSQ has limited ability to identify the female autistic phenotype.34 As such, these are solely screening tools. Final diagnosis is based on clinical judgment.

Special considerations. Include screening for constipation or diarrhea, fiber intake, food aversions, and common mental health comorbidities using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition criteria.29 Psychiatric referral may be necessary if certain previously undiagnosed condition(s) become apparent. The patient’s caregiver can provide supplemental information

Continue to: During the physical exam...

During the physical exam, limit sensory stimuli as much as possible, including lights and sounds. Verbalize components of the exam before touching a patient with autism who is sensitive to physical touch.

Which exercise? Participation in sports is an effective therapy for autism and can help patients develop communication skills and promote socialization. Vigorous exercise is associated with a reduction in stereotypic behaviors, hyperactivity, aggression, and self-injury.3 Sports also can offer an alternative channel for social interaction. Children with autism may have impaired or delayed motor skills, and exercise can improve motor skill proficiency.4

The prevalence of feeding problems in children with autism spectrum disorder is estimated to be as high as 90%, and close to 70% are selective eaters.31,35,36 For those with gastrointestinal disorders, exercise can exert positive effects on the microbiome-gut-brain axis.37 Additionally, patients with autism are much more likely to be overweight or obese.32 Physical activity offers those with autism health benefits similar to those for the general population.32

Children with autism spectrum disorder have similar odds of injury, including serious injury, relative to population controls.38 Karate and swimming are among the most researched sports therapy options for patients with autism.38-40 Both are shown to improve motor ability and reduce communication deficits.

Summing up

The literature, although limited, demonstrates that exercise and sports improve the health and well-being of people with IDDs throughout the lifespan, especially if childhood exercise/sports involvement is maintained.

Encourage your patients to participate in sports, but be aware of factors that can limit (or facilitate) participation.41 Exercise participation increases based on, among other things, the individual’s desire to be fit and active, skills practice, peer involvement, family support, accessible facilities, and skilled staff.10

Additional resources that can help people with IDDs access sports and recreational activities include the Special Olympics; Paralympics; YMCA; after-school programs; The American College of Sports Medicine; The National Center on Health, Physical Activity, and Disability; and disability-certified inclusive fitness trainers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristina Jones, BS, 12901 Bruce B. Downs Boulevard, Tampa, FL 33612; kjones15@usf.edu

1. CDC. Addressing gaps in healthcare for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Updated October 15, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2023. www.cdc.gov/grand-rounds/pp/2019/20191015-intellectual-disabilities.html

2. CDC. Vital signs: adults with disabilities. Physical activity is for everybody. Updated November 16, 2018. Accessed January 21, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/disabilities/index.html

3. Di Palma D, Molisso V. Sport for autism. J Humanities Soc Pol. 2017;3:42-49.

4. Pan CY, Chu CH, Tsai CL, et al. The impacts of physical activity intervention on physical and cognitive outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2017;21:190-202. doi: 10.1177/1362361316633562

5. Verschuren O, Peterson MD, Balemans AC, et al. Exercise and physical activity recommendations for people with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:798-808. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13053

6. Paul Y, Ellapen TJ, Barnard M, et al. The health benefits of exercise therapy for patients with Down syndrome: a systematic review. Afr J Disabil. 2019;8:576. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v8i0.576

7. Carroll DD, Courtney-Long EA, Stevens AC, et al. Vital signs: disability and physical activity—United States, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:407-413.

8. Rimmer JH. Physical activity for people with disabilities: how do we reach those with the greatest need? NAM Perspectives. Published April 6, 2015. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://nam.edu/perspectives-2015-physical-activity-for-people-with-disabilities-how-do-we-reach-those-with-the-greatest-need/

9. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines For Americans. 2nd edition. Published 2018. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

10. Darcy S, Dowse L. In search of a level playing field—the constraints and benefits of sport participation for people with intellectual disability. Disabil Soc. 2013;28:393-407. doi: 10.1080/ 09687599.2012.714258

11. Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, et al. National population‐based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111:1420-1435. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1589

12. MyŚliwiec A, Posłuszny A, Saulicz E, et al. Atlanto-axial instability in people with Down’s syndrome and its impact on the ability to perform sports activities—a review. J Hum Kinet. 2015;48:17-24. doi: 10.1515/hukin-2015-0087

13. Bunt CW, Bunt SK. Role of the family physician in the care of children with Down syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:851-858.

14. McCormick DP, Niebuhr VN, Risser WL. Injury and illness surveillance at local Special Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med. 1990; 24:221-224. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.24.4.221

15. McGuire BE, Defrin R. Pain perception in people with Down syndrome: a synthesis of clinical and experimental research. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00194

16. Barnhart RC, Connolly B. Aging and Down syndrome: implications for physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1399-1406. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060334

17. Vitrikas K, Dalton H, Breish D. Cerebral palsy: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101:213-220.

18. Maenner MJ, Blumberg SJ, Kogan MD, et al. Prevalence of cerebral palsy and intellectual disability among children identified in two US national surveys, 2011-2013. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:222-226. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.01.001

19. Smith KJ, Peterson MD, O’Connell NE, et al. Risk of depression and anxiety in adults with cerebral palsy. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76;294-300. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4147

20. Peterson MD, Haapala HJ, Chaddha A, et al. Abdominal obesity is an independent predictor of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in adults with cerebral palsy. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2014;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-11-22

21. Yi YG, Jung SH, Bang MS. Emerging issues in cerebral palsy associated with aging: a physiatrist perspective. Ann Rehabil Med. 2019;43:241-249. doi: 10.5535/arm.2019.43.3.241

22. Sarathy K, Doshi C, Aroojis A. Clinical examination of children with cerebral palsy. Indian J Orthop. 2019;53:35-44. doi: 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_409_17

23. Caulton JM, Ward KA, Alsop CW, et al. A randomised controlled trial of standing programme on bone mineral density in non-ambulant children with cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:131-135. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.009316

24. Clutterbuck G, Auld M, Johnston L. Active exercise interventions improve gross motor function of ambulant/semi-ambulant children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:1131-1151. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1422035

25. Shikako-Thomas K, Majnemer A, Law M, et al. Determinants of participation in leisure activities in children and youth with cerebral palsy: systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pedi. 2008;28:155-169. doi: 10.1080/01942630802031834

26. Teixeira-Machado L, Azevedo-Santos I, DeSantana JM. Dance improves functionality and psychosocial adjustment in cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:424-429. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000646

27. Lucena-Antón D, Rosety-Rodríguez I, Moral-Munoz JA. Effects of a hippotherapy intervention on muscle spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;31:188-192. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.02.013

28. Roostaei M, Baharlouei H, Azadi H, et al. Effects of aquatic intervention on gross motor skills in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2017;37:496-515. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2016.1247938

29. American Psychiatric Association. Autism spectrum disorder, section II. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013:50-56.

30. Romero M, Aguilar JM, Del-Rey-Mejías Á, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in autism spectrum disorder: a comparative study between DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 diagnosis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2016;16:266-275. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2016.03.001

31. Volkert VM, Vaz PC. Recent studies on feeding problems in children with autism. J Appl Behav Anal. 2015;43:155-159. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-155

32. Broder-Fingert S, Brazauskas K, Lindgren K, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in a large clinical sample of children with autism. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:408-414. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.04.004. PMID: 24976353

33. Adachi M, Takahashi M, Takayanagi N, et al. Adaptation of the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ) to preschool children. PLoS One. 2018;10;13:e0199590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199590

34. Kopp S. Gillberg C. The Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ)-Revised Extended Version (ASSQ-REV): an instrument for better capturing the autism phenotype in girls? A preliminary study involving 191 clinical cases and community controls. Res Develop Disabil. 2011:32: 2875-2888.

35. Kotak T. Piazza CC. Assessment and behavioral treatment of feeding and sleeping disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Adol Psych Clin North Am. 2008;17:887-905. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.005

36. Twachtman-Reilly J, Amaral SC, Zebrowski PP. Addressing feeding behaviors in children on the autism spectrum in school-based settings: physiological and behavioral issues. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2008:39:261-272. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/025)

37. Dalton A, Mermier C, Zuhl M. Exercise influence on the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Gut Microbes. 2019;10:555-568. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1562268

38. Iliadis I, Apteslis N. The role of physical education and exercise for children with autism spectrum disorder and the effects on socialization, communication, behavior, fitness, and quality of life. Dial Clin Neurosc Mental Health. 2020;3:71-78. doi: 10.26386/obrela.v3i1.178

39. Phung JN, Goldberg WA. Promoting executive functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder through mixed martial arts training. J Autism Dev Dis. 2019;49:3660-3684. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04072-3

40. Bahrami F, Movahedi A, Marandi SM, et al. The effect of karate techniques training on communication deficit of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46: 978-986. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2643-y

41. Shields N, Synnot A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0544-7

Approximately 6.5 million people in the United States have an intellectual disability, the most common type of developmental disability.1 People with disabilities are 3 times more likely to have heart disease, stroke, or diabetes than adults without disabilities.2

Sports as a treatment modality are not used to full advantage to combat these conditions in people with intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDDs). Participation in sport activities can lead to weight loss, reduce risk for cardiovascular disease, and optimize physical health. Sports also can help enhance social and communication skills and improve quality of life for this patient population (TABLE).3-6

However, a 2014 report found that while inactive adults with disabilities (hearing, vision, cognition, mobility) were 50% more likely to report 1 or more chronic diseases than those who were physically active, only 44% of adults with disabilities who visited a health professional in the previous 12 months received a physical activity recommendation.7 In addition, more than 50% of adults with disabilities are not meeting US recommended exercise guidelines.7-9

Family physicians may not feel they have adequate training to counsel patients with IDDs. Additional limiting factors include dependence on caregivers for exercise participation, expense, transportation difficulties, a lack of choice in sporting activities, and the patient’s level of motivation.10The guidance reviewed here details how to modify the pre-participation sports physical exam specifically for patients with IDDs. It also provides sport and exercise recommendations for patients with 3 disabilities: Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and autism spectrum disorder.

Worth noting: As is true for adults without disabilities, those with IDDs should participate in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity, aerobic physical activity each week.9 Recommend muscle-strengthening activities be performed at least 2 days each week.9

Exercise recommendations for patients with Down syndrome

One in every 700 babies receives a diagnosis of Down syndrome.11 Among its many possible manifestations—which include intellectual disability, heart disease, and diabetes—Down syndrome is associated with an increased risk for obesity, which makes exercise an extremely important lifestyle modification for these patients. Obesity can lead to obstructive sleep apnea causing cor pulmonale and even premature death. Continuous positive airway pressure intervention can be difficult in terms of patient compliance. However, weight loss through exercise and sports is an effective intervention to mitigate these obesity-related health comorbidities.

Pre-participation exam. A focused history and physical exam are often conducted before a patient engages in organized competitive or recreational sports. The pre-participation sports physical exam typically focuses on cardiac, neurologic, hereditary, and musculoskeletal disorders. While we recommend including these baseline elements as part of the exam for patients with disabilities, we also recommend modifying the exam to include disability-specific screening for associated comorbidities.

Continue to: For patients with Down syndrome...

For patients with Down syndrome, a complete pre-participation sports physical exam is warranted. Inquire specifically about neck pain or dislocations, heart murmur, cardiac surgery, seizures, sleep issues, history of congenital abdominal defect, hematologic malignancy, and bone pain as part of the focused physical exam.

Look for evidence of patellofemoral instability, pes planus, scoliosis, hallux deformities, decreased muscle tone, and muscular weakness. Check for cataracts and perform a thorough cardiovascular exam to assess for murmur or signs of chronic hypoxia, such as cyanosis. If a heart murmur is detected, refer the patient to a cardiologist.

Patients with Down syndrome are also at increased risk for atlantoaxial instability. A thorough neurologic evaluation to screen for this condition is indicated; however, routine radiologic screening is not needed.12

An annual complete blood cell count and thyroid-stimulating hormone test are recommended for all children with Down syndrome.13 For patients with Down syndrome who are 13 to 21 years of age, an echocardiogram also is recommended for concerning symptoms.13 Ferritin levels also should be assessed annually for patients who are younger than 13 years of age to check for iron-deficiency anemia.13Consider high-risk screening strategies for patients with diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

Special considerations. Patients with Down syndrome were found to be injured more frequently than individuals with other disabilities during the Special Olympics.14 These patients may be hypersensitive to pain with prolonged pain responses, or unable to verbally communicate their pain or injury.15

Continue to: The complexity of pain assessment...

The complexity of pain assessment in patients with Down syndrome may increase the difficulty of accurately diagnosing an injury, leading to underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis. To increase accuracy of pain assessment in this setting, we recommend using the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale or a numeric pain rating scale in verbal patients.15 In nonverbal patients, facial expressions are reliable indicators of pain.

Which exercise? Healthy patients with Down syndrome can participate in any sport. Aerobic exercise can help lower body fat, reduce oxidative stress, and improve blood flow.6 Muscle-strengthening exercises can lead to improved daily functioning and balance. Strength training and aerobic exercise benefit aging patients with Down syndrome who are struggling with obesity. Such exercise also helps increase bone mineral density and improve cardiovascular fitness, especially when initiated at a young age. Consistent exercise promotes positive health outcomes throughout the lifespan.16

Exercise recommendations for patients with cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy, the most common motor disability in children, is associated with intellectual disability, seizures, respiratory insufficiency, scoliosis, osteoporosis, mood disorders, dysphagia, and speech and hearing impairment.17 The increasing survival of premature babies born with cerebral palsy and the growing prevalence of adults with the condition point to the importance of expanding one’s knowledge of how best to care for this population.18

Pre-participation exam. In addition to a complete sport physical exam, it’s important to further evaluate patients with cerebral palsy for epilepsy, joint contractures, muscle weakness, spinal deformities, and respiratory insufficiency. The Gross Motor Function Classification system, commonly used for patients with cerebral palsy, scores functional ability in 5 levels.18 Patients at Level I are the most mobile; patients at Level V need wheelchair transport in all settings.

Further evaluation of spinal deformities can be initiated with x-ray screening. Consider ordering dual x-ray absorptiometry scans to evaluate bone mass.17

Continue to: Special considerations

Special considerations. Patients with cerebral palsy have a heightened risk for depression and anxiety.19 Mental health can be assessed via the General Anxiety Disorder-7, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions tools, among others. Mental health screening may need to be adjusted depending on the patient’s level of cognition and ability to communicate. The patient’s caregiver also can provide supplemental information.

Consider screening vitamin D levels in patients with cerebral palsy. Approximately 50% of adults with cerebral palsy are vitamin D–deficient secondary to sedentary behavior and lack of sun exposure.20-22

Optimal medical management has been shown to decrease muscle spasticity and may be beneficial before initiating an exercise program. For patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms, referral for physical therapy to further improve gross motor function and spasticity may be required before initiating an exercise program.

Which exercise? Individuals with cerebral palsy spend 76% to 99% of their waking hours being sedentary.5 Consequently, they typically have decreased cardiorespiratory endurance and decreased muscle strength. Strength training may improve muscle spasticity, gross motor function, joint health, and respiratory insufficiency.5 Even in those who function at Level IV-V of the Gross Motor Function Classification system, exercise reduces vertebral fractures and improves time spent standing.23 By improving endurance, spasticity, and strength with exercise, deconditioning can be mitigated.

Involvement in sports promotes peer interactions, personal interests, and positive self-identity. It can give a newfound passion for life. Additionally, families of children with disabilities who engage in leisure activities together have less caregiver burden.24,25 Sporting activities offer a way to optimize psychosocial well-being for the patient and the entire family.

Continue to: Dance promotes functionality...

Dance promotes functionality and psychosocial adjustment.26 Hippotherapy, defined as therapy and rehabilitation during which the patient interacts with horses, can diminish muscle spasticity.27 Aquatic therapy also may increase muscle strength.28

Sports for patients with autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder is defined as persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction that are usually evident in the first 3 years of life.29 Autism can manifest with or without intellectual or language impairment. Patients with autism commonly have difficulty processing sensory stimuli and can experience “sensory overload.” More than half have a coexisting mental health disorder, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder.30

Aversions to foods and food selectivity, as well as adverse effects from medical treatment of autism-related agitation, result in a higher incidence of obesity in patients with autism.31,32

Pre-participation exam. In addition to a comprehensive pre-participation exam, the Autism Spectrum Syndrome Questionnaire (ASSQ) and Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers are tools to screen school-age children with normal cognition to mild intellectual disability.33 These questionnaires have limitations, however. For example, ASSQ has limited ability to identify the female autistic phenotype.34 As such, these are solely screening tools. Final diagnosis is based on clinical judgment.

Special considerations. Include screening for constipation or diarrhea, fiber intake, food aversions, and common mental health comorbidities using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition criteria.29 Psychiatric referral may be necessary if certain previously undiagnosed condition(s) become apparent. The patient’s caregiver can provide supplemental information

Continue to: During the physical exam...

During the physical exam, limit sensory stimuli as much as possible, including lights and sounds. Verbalize components of the exam before touching a patient with autism who is sensitive to physical touch.

Which exercise? Participation in sports is an effective therapy for autism and can help patients develop communication skills and promote socialization. Vigorous exercise is associated with a reduction in stereotypic behaviors, hyperactivity, aggression, and self-injury.3 Sports also can offer an alternative channel for social interaction. Children with autism may have impaired or delayed motor skills, and exercise can improve motor skill proficiency.4

The prevalence of feeding problems in children with autism spectrum disorder is estimated to be as high as 90%, and close to 70% are selective eaters.31,35,36 For those with gastrointestinal disorders, exercise can exert positive effects on the microbiome-gut-brain axis.37 Additionally, patients with autism are much more likely to be overweight or obese.32 Physical activity offers those with autism health benefits similar to those for the general population.32

Children with autism spectrum disorder have similar odds of injury, including serious injury, relative to population controls.38 Karate and swimming are among the most researched sports therapy options for patients with autism.38-40 Both are shown to improve motor ability and reduce communication deficits.

Summing up

The literature, although limited, demonstrates that exercise and sports improve the health and well-being of people with IDDs throughout the lifespan, especially if childhood exercise/sports involvement is maintained.

Encourage your patients to participate in sports, but be aware of factors that can limit (or facilitate) participation.41 Exercise participation increases based on, among other things, the individual’s desire to be fit and active, skills practice, peer involvement, family support, accessible facilities, and skilled staff.10

Additional resources that can help people with IDDs access sports and recreational activities include the Special Olympics; Paralympics; YMCA; after-school programs; The American College of Sports Medicine; The National Center on Health, Physical Activity, and Disability; and disability-certified inclusive fitness trainers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristina Jones, BS, 12901 Bruce B. Downs Boulevard, Tampa, FL 33612; kjones15@usf.edu

Approximately 6.5 million people in the United States have an intellectual disability, the most common type of developmental disability.1 People with disabilities are 3 times more likely to have heart disease, stroke, or diabetes than adults without disabilities.2

Sports as a treatment modality are not used to full advantage to combat these conditions in people with intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDDs). Participation in sport activities can lead to weight loss, reduce risk for cardiovascular disease, and optimize physical health. Sports also can help enhance social and communication skills and improve quality of life for this patient population (TABLE).3-6

However, a 2014 report found that while inactive adults with disabilities (hearing, vision, cognition, mobility) were 50% more likely to report 1 or more chronic diseases than those who were physically active, only 44% of adults with disabilities who visited a health professional in the previous 12 months received a physical activity recommendation.7 In addition, more than 50% of adults with disabilities are not meeting US recommended exercise guidelines.7-9

Family physicians may not feel they have adequate training to counsel patients with IDDs. Additional limiting factors include dependence on caregivers for exercise participation, expense, transportation difficulties, a lack of choice in sporting activities, and the patient’s level of motivation.10The guidance reviewed here details how to modify the pre-participation sports physical exam specifically for patients with IDDs. It also provides sport and exercise recommendations for patients with 3 disabilities: Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and autism spectrum disorder.

Worth noting: As is true for adults without disabilities, those with IDDs should participate in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity, aerobic physical activity each week.9 Recommend muscle-strengthening activities be performed at least 2 days each week.9

Exercise recommendations for patients with Down syndrome

One in every 700 babies receives a diagnosis of Down syndrome.11 Among its many possible manifestations—which include intellectual disability, heart disease, and diabetes—Down syndrome is associated with an increased risk for obesity, which makes exercise an extremely important lifestyle modification for these patients. Obesity can lead to obstructive sleep apnea causing cor pulmonale and even premature death. Continuous positive airway pressure intervention can be difficult in terms of patient compliance. However, weight loss through exercise and sports is an effective intervention to mitigate these obesity-related health comorbidities.

Pre-participation exam. A focused history and physical exam are often conducted before a patient engages in organized competitive or recreational sports. The pre-participation sports physical exam typically focuses on cardiac, neurologic, hereditary, and musculoskeletal disorders. While we recommend including these baseline elements as part of the exam for patients with disabilities, we also recommend modifying the exam to include disability-specific screening for associated comorbidities.

Continue to: For patients with Down syndrome...

For patients with Down syndrome, a complete pre-participation sports physical exam is warranted. Inquire specifically about neck pain or dislocations, heart murmur, cardiac surgery, seizures, sleep issues, history of congenital abdominal defect, hematologic malignancy, and bone pain as part of the focused physical exam.

Look for evidence of patellofemoral instability, pes planus, scoliosis, hallux deformities, decreased muscle tone, and muscular weakness. Check for cataracts and perform a thorough cardiovascular exam to assess for murmur or signs of chronic hypoxia, such as cyanosis. If a heart murmur is detected, refer the patient to a cardiologist.

Patients with Down syndrome are also at increased risk for atlantoaxial instability. A thorough neurologic evaluation to screen for this condition is indicated; however, routine radiologic screening is not needed.12

An annual complete blood cell count and thyroid-stimulating hormone test are recommended for all children with Down syndrome.13 For patients with Down syndrome who are 13 to 21 years of age, an echocardiogram also is recommended for concerning symptoms.13 Ferritin levels also should be assessed annually for patients who are younger than 13 years of age to check for iron-deficiency anemia.13Consider high-risk screening strategies for patients with diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

Special considerations. Patients with Down syndrome were found to be injured more frequently than individuals with other disabilities during the Special Olympics.14 These patients may be hypersensitive to pain with prolonged pain responses, or unable to verbally communicate their pain or injury.15

Continue to: The complexity of pain assessment...

The complexity of pain assessment in patients with Down syndrome may increase the difficulty of accurately diagnosing an injury, leading to underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis. To increase accuracy of pain assessment in this setting, we recommend using the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale or a numeric pain rating scale in verbal patients.15 In nonverbal patients, facial expressions are reliable indicators of pain.

Which exercise? Healthy patients with Down syndrome can participate in any sport. Aerobic exercise can help lower body fat, reduce oxidative stress, and improve blood flow.6 Muscle-strengthening exercises can lead to improved daily functioning and balance. Strength training and aerobic exercise benefit aging patients with Down syndrome who are struggling with obesity. Such exercise also helps increase bone mineral density and improve cardiovascular fitness, especially when initiated at a young age. Consistent exercise promotes positive health outcomes throughout the lifespan.16

Exercise recommendations for patients with cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy, the most common motor disability in children, is associated with intellectual disability, seizures, respiratory insufficiency, scoliosis, osteoporosis, mood disorders, dysphagia, and speech and hearing impairment.17 The increasing survival of premature babies born with cerebral palsy and the growing prevalence of adults with the condition point to the importance of expanding one’s knowledge of how best to care for this population.18

Pre-participation exam. In addition to a complete sport physical exam, it’s important to further evaluate patients with cerebral palsy for epilepsy, joint contractures, muscle weakness, spinal deformities, and respiratory insufficiency. The Gross Motor Function Classification system, commonly used for patients with cerebral palsy, scores functional ability in 5 levels.18 Patients at Level I are the most mobile; patients at Level V need wheelchair transport in all settings.

Further evaluation of spinal deformities can be initiated with x-ray screening. Consider ordering dual x-ray absorptiometry scans to evaluate bone mass.17

Continue to: Special considerations

Special considerations. Patients with cerebral palsy have a heightened risk for depression and anxiety.19 Mental health can be assessed via the General Anxiety Disorder-7, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions tools, among others. Mental health screening may need to be adjusted depending on the patient’s level of cognition and ability to communicate. The patient’s caregiver also can provide supplemental information.

Consider screening vitamin D levels in patients with cerebral palsy. Approximately 50% of adults with cerebral palsy are vitamin D–deficient secondary to sedentary behavior and lack of sun exposure.20-22

Optimal medical management has been shown to decrease muscle spasticity and may be beneficial before initiating an exercise program. For patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms, referral for physical therapy to further improve gross motor function and spasticity may be required before initiating an exercise program.

Which exercise? Individuals with cerebral palsy spend 76% to 99% of their waking hours being sedentary.5 Consequently, they typically have decreased cardiorespiratory endurance and decreased muscle strength. Strength training may improve muscle spasticity, gross motor function, joint health, and respiratory insufficiency.5 Even in those who function at Level IV-V of the Gross Motor Function Classification system, exercise reduces vertebral fractures and improves time spent standing.23 By improving endurance, spasticity, and strength with exercise, deconditioning can be mitigated.

Involvement in sports promotes peer interactions, personal interests, and positive self-identity. It can give a newfound passion for life. Additionally, families of children with disabilities who engage in leisure activities together have less caregiver burden.24,25 Sporting activities offer a way to optimize psychosocial well-being for the patient and the entire family.

Continue to: Dance promotes functionality...

Dance promotes functionality and psychosocial adjustment.26 Hippotherapy, defined as therapy and rehabilitation during which the patient interacts with horses, can diminish muscle spasticity.27 Aquatic therapy also may increase muscle strength.28

Sports for patients with autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder is defined as persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction that are usually evident in the first 3 years of life.29 Autism can manifest with or without intellectual or language impairment. Patients with autism commonly have difficulty processing sensory stimuli and can experience “sensory overload.” More than half have a coexisting mental health disorder, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder.30

Aversions to foods and food selectivity, as well as adverse effects from medical treatment of autism-related agitation, result in a higher incidence of obesity in patients with autism.31,32

Pre-participation exam. In addition to a comprehensive pre-participation exam, the Autism Spectrum Syndrome Questionnaire (ASSQ) and Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers are tools to screen school-age children with normal cognition to mild intellectual disability.33 These questionnaires have limitations, however. For example, ASSQ has limited ability to identify the female autistic phenotype.34 As such, these are solely screening tools. Final diagnosis is based on clinical judgment.

Special considerations. Include screening for constipation or diarrhea, fiber intake, food aversions, and common mental health comorbidities using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition criteria.29 Psychiatric referral may be necessary if certain previously undiagnosed condition(s) become apparent. The patient’s caregiver can provide supplemental information

Continue to: During the physical exam...

During the physical exam, limit sensory stimuli as much as possible, including lights and sounds. Verbalize components of the exam before touching a patient with autism who is sensitive to physical touch.

Which exercise? Participation in sports is an effective therapy for autism and can help patients develop communication skills and promote socialization. Vigorous exercise is associated with a reduction in stereotypic behaviors, hyperactivity, aggression, and self-injury.3 Sports also can offer an alternative channel for social interaction. Children with autism may have impaired or delayed motor skills, and exercise can improve motor skill proficiency.4

The prevalence of feeding problems in children with autism spectrum disorder is estimated to be as high as 90%, and close to 70% are selective eaters.31,35,36 For those with gastrointestinal disorders, exercise can exert positive effects on the microbiome-gut-brain axis.37 Additionally, patients with autism are much more likely to be overweight or obese.32 Physical activity offers those with autism health benefits similar to those for the general population.32

Children with autism spectrum disorder have similar odds of injury, including serious injury, relative to population controls.38 Karate and swimming are among the most researched sports therapy options for patients with autism.38-40 Both are shown to improve motor ability and reduce communication deficits.

Summing up

The literature, although limited, demonstrates that exercise and sports improve the health and well-being of people with IDDs throughout the lifespan, especially if childhood exercise/sports involvement is maintained.

Encourage your patients to participate in sports, but be aware of factors that can limit (or facilitate) participation.41 Exercise participation increases based on, among other things, the individual’s desire to be fit and active, skills practice, peer involvement, family support, accessible facilities, and skilled staff.10

Additional resources that can help people with IDDs access sports and recreational activities include the Special Olympics; Paralympics; YMCA; after-school programs; The American College of Sports Medicine; The National Center on Health, Physical Activity, and Disability; and disability-certified inclusive fitness trainers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristina Jones, BS, 12901 Bruce B. Downs Boulevard, Tampa, FL 33612; kjones15@usf.edu

1. CDC. Addressing gaps in healthcare for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Updated October 15, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2023. www.cdc.gov/grand-rounds/pp/2019/20191015-intellectual-disabilities.html

2. CDC. Vital signs: adults with disabilities. Physical activity is for everybody. Updated November 16, 2018. Accessed January 21, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/disabilities/index.html

3. Di Palma D, Molisso V. Sport for autism. J Humanities Soc Pol. 2017;3:42-49.

4. Pan CY, Chu CH, Tsai CL, et al. The impacts of physical activity intervention on physical and cognitive outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2017;21:190-202. doi: 10.1177/1362361316633562

5. Verschuren O, Peterson MD, Balemans AC, et al. Exercise and physical activity recommendations for people with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:798-808. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13053

6. Paul Y, Ellapen TJ, Barnard M, et al. The health benefits of exercise therapy for patients with Down syndrome: a systematic review. Afr J Disabil. 2019;8:576. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v8i0.576

7. Carroll DD, Courtney-Long EA, Stevens AC, et al. Vital signs: disability and physical activity—United States, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:407-413.

8. Rimmer JH. Physical activity for people with disabilities: how do we reach those with the greatest need? NAM Perspectives. Published April 6, 2015. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://nam.edu/perspectives-2015-physical-activity-for-people-with-disabilities-how-do-we-reach-those-with-the-greatest-need/

9. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines For Americans. 2nd edition. Published 2018. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

10. Darcy S, Dowse L. In search of a level playing field—the constraints and benefits of sport participation for people with intellectual disability. Disabil Soc. 2013;28:393-407. doi: 10.1080/ 09687599.2012.714258

11. Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, et al. National population‐based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111:1420-1435. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1589

12. MyŚliwiec A, Posłuszny A, Saulicz E, et al. Atlanto-axial instability in people with Down’s syndrome and its impact on the ability to perform sports activities—a review. J Hum Kinet. 2015;48:17-24. doi: 10.1515/hukin-2015-0087

13. Bunt CW, Bunt SK. Role of the family physician in the care of children with Down syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:851-858.

14. McCormick DP, Niebuhr VN, Risser WL. Injury and illness surveillance at local Special Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med. 1990; 24:221-224. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.24.4.221

15. McGuire BE, Defrin R. Pain perception in people with Down syndrome: a synthesis of clinical and experimental research. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00194

16. Barnhart RC, Connolly B. Aging and Down syndrome: implications for physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1399-1406. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060334

17. Vitrikas K, Dalton H, Breish D. Cerebral palsy: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101:213-220.

18. Maenner MJ, Blumberg SJ, Kogan MD, et al. Prevalence of cerebral palsy and intellectual disability among children identified in two US national surveys, 2011-2013. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:222-226. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.01.001

19. Smith KJ, Peterson MD, O’Connell NE, et al. Risk of depression and anxiety in adults with cerebral palsy. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76;294-300. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4147

20. Peterson MD, Haapala HJ, Chaddha A, et al. Abdominal obesity is an independent predictor of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in adults with cerebral palsy. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2014;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-11-22

21. Yi YG, Jung SH, Bang MS. Emerging issues in cerebral palsy associated with aging: a physiatrist perspective. Ann Rehabil Med. 2019;43:241-249. doi: 10.5535/arm.2019.43.3.241

22. Sarathy K, Doshi C, Aroojis A. Clinical examination of children with cerebral palsy. Indian J Orthop. 2019;53:35-44. doi: 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_409_17

23. Caulton JM, Ward KA, Alsop CW, et al. A randomised controlled trial of standing programme on bone mineral density in non-ambulant children with cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:131-135. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.009316

24. Clutterbuck G, Auld M, Johnston L. Active exercise interventions improve gross motor function of ambulant/semi-ambulant children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:1131-1151. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1422035

25. Shikako-Thomas K, Majnemer A, Law M, et al. Determinants of participation in leisure activities in children and youth with cerebral palsy: systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pedi. 2008;28:155-169. doi: 10.1080/01942630802031834

26. Teixeira-Machado L, Azevedo-Santos I, DeSantana JM. Dance improves functionality and psychosocial adjustment in cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:424-429. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000646

27. Lucena-Antón D, Rosety-Rodríguez I, Moral-Munoz JA. Effects of a hippotherapy intervention on muscle spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;31:188-192. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.02.013

28. Roostaei M, Baharlouei H, Azadi H, et al. Effects of aquatic intervention on gross motor skills in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2017;37:496-515. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2016.1247938

29. American Psychiatric Association. Autism spectrum disorder, section II. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013:50-56.

30. Romero M, Aguilar JM, Del-Rey-Mejías Á, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in autism spectrum disorder: a comparative study between DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 diagnosis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2016;16:266-275. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2016.03.001

31. Volkert VM, Vaz PC. Recent studies on feeding problems in children with autism. J Appl Behav Anal. 2015;43:155-159. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-155

32. Broder-Fingert S, Brazauskas K, Lindgren K, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in a large clinical sample of children with autism. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:408-414. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.04.004. PMID: 24976353

33. Adachi M, Takahashi M, Takayanagi N, et al. Adaptation of the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ) to preschool children. PLoS One. 2018;10;13:e0199590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199590

34. Kopp S. Gillberg C. The Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ)-Revised Extended Version (ASSQ-REV): an instrument for better capturing the autism phenotype in girls? A preliminary study involving 191 clinical cases and community controls. Res Develop Disabil. 2011:32: 2875-2888.

35. Kotak T. Piazza CC. Assessment and behavioral treatment of feeding and sleeping disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Adol Psych Clin North Am. 2008;17:887-905. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.005

36. Twachtman-Reilly J, Amaral SC, Zebrowski PP. Addressing feeding behaviors in children on the autism spectrum in school-based settings: physiological and behavioral issues. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2008:39:261-272. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/025)

37. Dalton A, Mermier C, Zuhl M. Exercise influence on the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Gut Microbes. 2019;10:555-568. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1562268

38. Iliadis I, Apteslis N. The role of physical education and exercise for children with autism spectrum disorder and the effects on socialization, communication, behavior, fitness, and quality of life. Dial Clin Neurosc Mental Health. 2020;3:71-78. doi: 10.26386/obrela.v3i1.178

39. Phung JN, Goldberg WA. Promoting executive functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder through mixed martial arts training. J Autism Dev Dis. 2019;49:3660-3684. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04072-3

40. Bahrami F, Movahedi A, Marandi SM, et al. The effect of karate techniques training on communication deficit of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46: 978-986. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2643-y

41. Shields N, Synnot A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0544-7

1. CDC. Addressing gaps in healthcare for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Updated October 15, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2023. www.cdc.gov/grand-rounds/pp/2019/20191015-intellectual-disabilities.html

2. CDC. Vital signs: adults with disabilities. Physical activity is for everybody. Updated November 16, 2018. Accessed January 21, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/disabilities/index.html

3. Di Palma D, Molisso V. Sport for autism. J Humanities Soc Pol. 2017;3:42-49.

4. Pan CY, Chu CH, Tsai CL, et al. The impacts of physical activity intervention on physical and cognitive outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2017;21:190-202. doi: 10.1177/1362361316633562

5. Verschuren O, Peterson MD, Balemans AC, et al. Exercise and physical activity recommendations for people with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:798-808. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13053

6. Paul Y, Ellapen TJ, Barnard M, et al. The health benefits of exercise therapy for patients with Down syndrome: a systematic review. Afr J Disabil. 2019;8:576. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v8i0.576

7. Carroll DD, Courtney-Long EA, Stevens AC, et al. Vital signs: disability and physical activity—United States, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:407-413.

8. Rimmer JH. Physical activity for people with disabilities: how do we reach those with the greatest need? NAM Perspectives. Published April 6, 2015. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://nam.edu/perspectives-2015-physical-activity-for-people-with-disabilities-how-do-we-reach-those-with-the-greatest-need/

9. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines For Americans. 2nd edition. Published 2018. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

10. Darcy S, Dowse L. In search of a level playing field—the constraints and benefits of sport participation for people with intellectual disability. Disabil Soc. 2013;28:393-407. doi: 10.1080/ 09687599.2012.714258

11. Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, et al. National population‐based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111:1420-1435. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1589

12. MyŚliwiec A, Posłuszny A, Saulicz E, et al. Atlanto-axial instability in people with Down’s syndrome and its impact on the ability to perform sports activities—a review. J Hum Kinet. 2015;48:17-24. doi: 10.1515/hukin-2015-0087

13. Bunt CW, Bunt SK. Role of the family physician in the care of children with Down syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:851-858.

14. McCormick DP, Niebuhr VN, Risser WL. Injury and illness surveillance at local Special Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med. 1990; 24:221-224. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.24.4.221

15. McGuire BE, Defrin R. Pain perception in people with Down syndrome: a synthesis of clinical and experimental research. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00194

16. Barnhart RC, Connolly B. Aging and Down syndrome: implications for physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1399-1406. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060334

17. Vitrikas K, Dalton H, Breish D. Cerebral palsy: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101:213-220.

18. Maenner MJ, Blumberg SJ, Kogan MD, et al. Prevalence of cerebral palsy and intellectual disability among children identified in two US national surveys, 2011-2013. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:222-226. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.01.001

19. Smith KJ, Peterson MD, O’Connell NE, et al. Risk of depression and anxiety in adults with cerebral palsy. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76;294-300. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4147

20. Peterson MD, Haapala HJ, Chaddha A, et al. Abdominal obesity is an independent predictor of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in adults with cerebral palsy. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2014;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-11-22

21. Yi YG, Jung SH, Bang MS. Emerging issues in cerebral palsy associated with aging: a physiatrist perspective. Ann Rehabil Med. 2019;43:241-249. doi: 10.5535/arm.2019.43.3.241

22. Sarathy K, Doshi C, Aroojis A. Clinical examination of children with cerebral palsy. Indian J Orthop. 2019;53:35-44. doi: 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_409_17

23. Caulton JM, Ward KA, Alsop CW, et al. A randomised controlled trial of standing programme on bone mineral density in non-ambulant children with cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:131-135. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.009316

24. Clutterbuck G, Auld M, Johnston L. Active exercise interventions improve gross motor function of ambulant/semi-ambulant children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:1131-1151. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1422035

25. Shikako-Thomas K, Majnemer A, Law M, et al. Determinants of participation in leisure activities in children and youth with cerebral palsy: systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pedi. 2008;28:155-169. doi: 10.1080/01942630802031834

26. Teixeira-Machado L, Azevedo-Santos I, DeSantana JM. Dance improves functionality and psychosocial adjustment in cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:424-429. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000646

27. Lucena-Antón D, Rosety-Rodríguez I, Moral-Munoz JA. Effects of a hippotherapy intervention on muscle spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;31:188-192. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.02.013

28. Roostaei M, Baharlouei H, Azadi H, et al. Effects of aquatic intervention on gross motor skills in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2017;37:496-515. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2016.1247938

29. American Psychiatric Association. Autism spectrum disorder, section II. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013:50-56.

30. Romero M, Aguilar JM, Del-Rey-Mejías Á, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in autism spectrum disorder: a comparative study between DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 diagnosis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2016;16:266-275. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2016.03.001

31. Volkert VM, Vaz PC. Recent studies on feeding problems in children with autism. J Appl Behav Anal. 2015;43:155-159. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-155

32. Broder-Fingert S, Brazauskas K, Lindgren K, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in a large clinical sample of children with autism. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:408-414. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.04.004. PMID: 24976353

33. Adachi M, Takahashi M, Takayanagi N, et al. Adaptation of the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ) to preschool children. PLoS One. 2018;10;13:e0199590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199590

34. Kopp S. Gillberg C. The Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ)-Revised Extended Version (ASSQ-REV): an instrument for better capturing the autism phenotype in girls? A preliminary study involving 191 clinical cases and community controls. Res Develop Disabil. 2011:32: 2875-2888.

35. Kotak T. Piazza CC. Assessment and behavioral treatment of feeding and sleeping disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Adol Psych Clin North Am. 2008;17:887-905. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.005

36. Twachtman-Reilly J, Amaral SC, Zebrowski PP. Addressing feeding behaviors in children on the autism spectrum in school-based settings: physiological and behavioral issues. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2008:39:261-272. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/025)

37. Dalton A, Mermier C, Zuhl M. Exercise influence on the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Gut Microbes. 2019;10:555-568. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1562268

38. Iliadis I, Apteslis N. The role of physical education and exercise for children with autism spectrum disorder and the effects on socialization, communication, behavior, fitness, and quality of life. Dial Clin Neurosc Mental Health. 2020;3:71-78. doi: 10.26386/obrela.v3i1.178

39. Phung JN, Goldberg WA. Promoting executive functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder through mixed martial arts training. J Autism Dev Dis. 2019;49:3660-3684. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04072-3

40. Bahrami F, Movahedi A, Marandi SM, et al. The effect of karate techniques training on communication deficit of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46: 978-986. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2643-y

41. Shields N, Synnot A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0544-7

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend physical activity as an adjunct to traditional medical management to maximize physical and psychosocial benefits in patients with intellectual/developmental disabilities. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Conversion disorder: An integrated care approach

THE CASE

Janice M* presented to the emergency department (ED) with worsening slurred speech. The 55-year-old patient’s history was significant for diabetes; hypertension; depression; sleep apnea; multiple transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) thought to be stress related; and left lower-extremity weakness secondary to prior infarct. Ms. M had been to the hospital multiple times in the previous 2 to 3 years for similar symptoms. Her most recent visit to the ED had been 2 months earlier.

In the ED, the patient’s NIH stroke score was 1 for the presence of dysarthria, and a code for emergency stroke management was initiated. Ms. M was alert and oriented x 3, with no focal motor or sensory deficits noted. Computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography were negative for any acute abnormality. Throughout the course of the ED visit, her NIH score improved to 0. Ms. M exhibited staccato/stuttering speech, but it was believed that this would likely improve over the next few days.

According to the hospital neurologist, the ED work-up suggested either a TIA, stress-induced psychiatric speech disorder, or conversion disorder. The patient was discharged home in stable condition and was asked to follow up with the outpatient neurologist in 1 week.

Ms. M was seen approximately 2 weeks later in the outpatient neurology stroke clinic. Her symptoms had resolved, and she did not report any new or worsening symptoms. An outpatient stroke work-up was initiated, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, echocardiography, and measurement of low-density lipoprotein and hemoglobin A1C; all results were unremarkable. Given the timeline for symptom improvement and results of the work-up, the patient was given a diagnosis of conversion disorder. Ms. M was encouraged to follow up with her primary care physician (PCP) for further medical management.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

What is conversion disorder, and how common is it?

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, text revision, conversion disorder (also known as functional neurological symptom disorder) is characterized as a somatic symptom and related disorder.1 The prominent feature shared among disorders in this category is the presence of somatic symptoms that are associated with distress and impairment.

In conversion disorder, the focus is on symptoms that are neurologic in nature but are not due to underlying neurologic disease and are incongruent with typical patterns of presentation for any neurologic condition. Patients with conversion disorder may present with motor symptoms (eg, weakness, paralysis, tremor, dystonia), altered sensory or cognitive function, seizure-like symptoms, alterations in speech, or changes in swallowing.1,2

For a diagnosis of conversion disorder, the following criteria must be met1:

- The patient has 1 or more symptoms of altered voluntary motor or sensory function.

- Symptom presentation is incongruent with recognized neurologic or medical disease or conditions.

S ymptoms are not better explained by another medical or mental health condition.- There is significant distress or impairment in functioning due to symptoms or the deficit.

The etiology of conversion disorder has not been firmly established. While the literature suggests that psychological stressors play a role,3,4 an effort also has been made to better understand the underlying neural and biological basis. Specifically, studies have utilized brain imaging to explore brain pathways and mechanisms that could account for symptom presentation.5,6

Prevalence rates for conversion disorder vary depending on the population studied. While it is estimated that 5% of patients in a general hospital setting meet full criteria for conversion disorder,7 higher rates may exist in specialty settings; 1 study found that 30% of patients in a neurology specialty clinic exhibited symptoms that were medically unexplained.8

Continue to: In primary care...

In primary care, prevalence of conversion disorder can be difficult to pinpoint; however, 1 study indicated that physicians identified medically unexplained symptoms as the main presenting problem for nearly 20% of patients in a primary care setting.9 Therefore, it is important for family physicians (FPs) to be familiar with the assessment and treatment of conversion disorder (and other disorders in which medically unexplained symptoms may be at the core of the patient presentation).

The differential: Neurologic and psychiatric conditions

Patients with conversion disorder may present with a variety of neurologic symptoms that can mimic those of organic disease. This can pose a diagnostic challenge, increase the chance of misdiagnosis, and delay treatment.

Motor symptoms may include paralysis, gait disturbance, dysphagia, or aphasia. Patients also may have sensory symptoms, such as blindness, deafness, or anesthesia.10,11 As a result, it is important to rule out both urgent neurologic presentations, such as TIA, acute stroke, and brain tumor, and other chronic neurologic conditions, including multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, and epilepsy.11,12

Multiple sclerosis will demonstrate characteristic lesions on MRI that differentiate it from conversion disorder.

Myasthenia gravis is distinguished by positive findings on autoantibodies testing and on electrophysiologic studies.

Continue to: Epilepsy

Epilepsy. Patients with conversion disorder may present with unresponsiveness and abnormal movements, such as generalized limb shaking and hip thrusting, that mimic an epileptic seizure. In contrast to epileptic seizures, psychogenic nonepileptic seizures may last longer, symptoms may wax and wane, and patients generally do not have bowel or bladder incontinence or sustain injury as they would during an actual seizure.12

There are several psychiatric/psychosocial conditions that also should be considered in the differential diagnosis of conversion disorder.

Somatic symptom disorder, like conversion disorder, produces somatic symptoms that can cause significant distress for patients. The difference in the 2 conditions is that symptoms of somatic symptom disorder may be compatible with a recognized neurologic or general medical condition, whereas in conversion disorder, the symptoms are not consistent with a recognized disease.1,12

Factitious disorder, similar to conversion disorder, can involve neurologic symptoms that are not attributed to disease. However, patients with factitious disorder deliberately simulate symptoms to receive medical care. A thorough clinical interview and physical exam can help to distinguish conversion disorder from factitious disorder.

Malingering is not a psychiatric condition but a behavior that involves intentionally feigning symptoms for the purpose of personal or financial gain. There is no evidence that patients with conversion disorder simulate their symptoms.12,13

Continue to: Negative results and positive signs point to the Dx

Negative results and positive signs point to the Dx

Conversion disorder is not a diagnosis of exclusion. Diagnosis requires detailed history taking and a thorough neurologic exam. Laboratory testing and neuroimaging are also important, and results will have to be negative to support the diagnosis.

Neurologic deficits with conversion disorder do not follow a known neurologic insult.14 There are many tests that can be used to distinguish functional symptoms vs organic symptoms. Two of the most well-known tests are the Hoover sign and the abductor sign, which will be positive in conversion disorder. Both can be performed easily in an outpatient setting.

The Hoover sign is considered positive when there is weakness of voluntary hip extension in the presence of normal involuntary hip extension during contralateral hip flexion against resistance. According to a meta-analysis of multiple studies of patients with conversion disorder, the overall estimated sensitivity of this test is 94% and the specificity, 99%.15

The abductor sign follows the same principle as the Hoover sign: When the patient abducts the nonparetic leg, both the nonparetic and “paretic” leg are strong. When the patient abducts just the “paretic” leg, both legs become weak.16

Other symptom evaluations. For patients who have functional seizures, video electroencephalography is helpful to distinguish functional seizures from “true” seizures.17,18 In conversion disorder, functional dysarthria normally resembles a stutter or speech that is extremely slow with long hesitations that are hard to interrupt.18 Dysphonia and functional dysphagia are also very common functional symptoms. Usually after extensive work-up, no organic cause of the patient’s symptoms is ever found.18

Continue to: Treatment requires an integrated team approach

Treatment requires an integrated team approach

Treatment for conversion disorder can be difficult due to the complex and not fully understood etiology of the condition. Due to its multifaceted nature, an integrated team approach can be beneficial at each stage, including assessment and intervention.

Explain the diagnosis clearly. An essential initial step in the treatment of conversion disorder is careful explanation of the diagnosis. Clear explanation of the terminology and presentation of conversion disorder may prevent the patient from misinterpreting their diagnosis as a suggestion that they are feigning or malingering symptoms or feeling that their symptoms or concerns are being dismissed.2 Understanding the condition can help improve the likelihood of the patient accepting the treatment plan and help decrease the likelihood of unnecessary testing, health care visits, and consultations. Developing a strong rapport with the patient is key when explaining the diagnosis.

Recommend cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In a meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials, CBT significantly reduced somatic, anxious, and depressive symptoms and improved physical functioning in patients with somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms.19 Another study, utilizing a case series, demonstrated significant improvement in social, emotional, and behavioral functioning in children and adolescents with functional neurologic symptoms (conversion disorder) post–CBT intervention.20

Given that research supports CBT’s effectiveness in the management of conversion disorder, it is beneficial to engage a behavioral health professional as a part of the treatment team to focus on factors such as stress management, development of coping skills, and treatment of underlying psychiatric conditions.

Consider these other options. The addition of medication management can be considered for patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Evidence suggests that physical therapy is helpful in the treatment of motor and gait dysfunction seen in conversion disorder.21,22 The role of hypnosis in the management of conversion disorder has also been studied, but more randomized clinical trials are needed to further explore this treatment.2,23,24

Continue to: The FP's role in coordination of care

The FP’s role in coordination of care

Conversion disorder can be challenging to diagnose and often involves a multidisciplinary approach. Patients with conversion disorder may see multiple clinicians as they undergo evaluation for their symptoms, but they usually are referred back to their PCP for management and coordination of care. Thus, the FP’s understanding of how the condition is diagnosed and appropriately managed is beneficial.

Open and effective communication among all members of the health care team can ensure consistency in treatment, a strong patient–provider relationship, favorable prognosis, and prevention of symptom relapse. FPs, by establishing a good rapport with patients, can help them understand the condition and the mind-body connection. Once other diagnoses have been ruled out, the FP can provide reassurance to patients and minimize further diagnostic testing.