User login

REALITY trial supports restrictive transfusion in anemic MI

in the landmark REALITY trial.

Randomized trial data already support a restrictive transfusion strategy in patients undergoing cardiac and noncardiac surgery, as well as in other settings. Those trials deliberately excluded patients with acute myocardial ischemia.

Cardiologists have been loath to adopt a restrictive strategy in the absence of persuasive supporting evidence because of a theoretic concern that low hemoglobin might be particularly harmful to ischemic myocardium. Anemia occurs in 5%-10% patients with MI, and clinicians have been eager for evidence-based guidance on how to best manage it.

“Blood is a precious resource and transfusion is costly, logistically cumbersome, and has side effects,” Philippe Gabriel Steg, MD, chair of the REALITY trial, noted in presenting the study results at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

REALITY was the first-ever large randomized trial of a restrictive versus liberal transfusion strategy in acute MI. The study, which featured a noninferiority design, included 668 stable patients with acute MI and anemia with a hemoglobin of 7-10 g/dL at 35 hospitals in France and Spain. Participants were randomized to a restrictive strategy in which transfusion was withheld unless the hemoglobin dropped to 8 g/dL or less, or to a conventional liberal strategy triggered by a hemoglobin of 10 g/dL or lower. The transfusion target was a hemoglobin level of 8-10 g/dL in the restrictive strategy group and greater than 11 g/dL in the liberal transfusion group. In the restrictive transfusion group, 36% received at least one RBC transfusion, as did 87% in the liberal transfusion study arm. The restrictive strategy group used 414 fewer units of blood.

The two coprimary endpoints were 30-day major adverse cardiovascular events and cost-effectiveness. The 30-day composite of all-cause mortality, reinfarction, stroke, and emergency percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial ischemia occurred in 11% of the restrictive transfusion group and 14% of the liberal transfusion group. The resultant 21% relative risk reduction established that the restrictive strategy was noninferior. Of note, all of the individual components of the composite endpoint numerically favored the restrictive approach.

In terms of safety, patients in the restrictive transfusion group were significantly less likely to develop an infection, by a margin of 0% versus 1.5%. The rate of acute lung injury was also significantly lower in the restrictive group: 0.3%, compared with 2.2%. The median hospital length of stay was identical at 7 days in both groups.

The cost-effectiveness analysis concluded that the restrictive transfusion strategy had an 84% probability of being both less expensive and more effective.

Patients were enrolled in REALITY regardless of whether they had active bleeding, as long as the bleeding wasn’t deemed massive and life-threatening. Notably, there was no difference in the results of restrictive versus liberal transfusion regardless of whether active bleeding was present, nor did baseline hemoglobin or the presence or absence of preexisting anemia affect the results.

Dr. Steg noted that a much larger randomized trial of restrictive versus liberal transfusion in the setting of acute MI with anemia is underway in the United States and Canada. The 3,000-patient MINT trial, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, is testing the superiority of restrictive transfusion, rather than its noninferiority, as in REALITY. Results are a couple of years away.

“I think that will be an important piece of additional evidence,” he said.

Discussant Marco Roffi, MD, didn’t mince words.

“I really love the REALITY trial,” declared Dr. Roffi, professor and vice chairman of the cardiology department and director of the interventional cardiology unit at University Hospital of Geneva.

He ticked off a series of reasons: The trial addressed a common clinical dilemma about which there has been essentially no prior high-quality evidence, it provided convincing results, and it carried important implications for responsible stewardship of the blood supply.

“REALITY allows clinicians to comfortably refrain from transfusing anemic patients presenting with myocardial infarction, and this should lead to a reduction in the consumption of blood products,” Dr. Roffi said.

He applauded the investigators for their success in obtaining public funding for a study lacking a commercial hook. And as a clinical investigator, he was particularly impressed by one of the technical details about the REALITY trial: “I was amazed by the fact that the observed event rates virtually corresponded to the estimated ones used for the power calculations. This is rarely the case in such a trial.”

Dr. Roffi said the REALITY findings should have an immediate impact on clinical practice, as well as on the brand new 2020 ESC guidelines on the management of non–ST-elevation ACS issued during the ESC virtual congress.

The freshly inked guidelines state: “Based on inconsistent study results and the lack of adequately powered randomized, controlled trials, a restrictive policy of transfusion in anemic patients with MI may be considered.” As of today, Dr. Roffi argued, the phrase “may be considered” ought to be replaced by the stronger phrase “should be considered.”

During the discussion period, he was asked if it’s appropriate to extrapolate the REALITY results to patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, among whom anemia is highly prevalent.

“I think this is a different patient population. Nevertheless, the concept of being restrictive is one that in my opinion now remains until proven otherwise. So we are being very restrictive in these patients,” he replied.

Asked about possible mechanisms by which liberal transfusion might have detrimental effects in acute MI patients, Dr. Steg cited several, including evidence that transfusion may not improve oxygen delivery to as great an extent as traditionally thought. There is also the risk of volume overload, increased blood viscosity, and enhanced platelet aggregation and activation, which could promote myocardial ischemia.

The REALITY trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness with no commercial support. Outside the scope of the trial, Dr. Steg reported receiving research grants from Bayer, Merck, Servier, and Sanofi as well as serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

in the landmark REALITY trial.

Randomized trial data already support a restrictive transfusion strategy in patients undergoing cardiac and noncardiac surgery, as well as in other settings. Those trials deliberately excluded patients with acute myocardial ischemia.

Cardiologists have been loath to adopt a restrictive strategy in the absence of persuasive supporting evidence because of a theoretic concern that low hemoglobin might be particularly harmful to ischemic myocardium. Anemia occurs in 5%-10% patients with MI, and clinicians have been eager for evidence-based guidance on how to best manage it.

“Blood is a precious resource and transfusion is costly, logistically cumbersome, and has side effects,” Philippe Gabriel Steg, MD, chair of the REALITY trial, noted in presenting the study results at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

REALITY was the first-ever large randomized trial of a restrictive versus liberal transfusion strategy in acute MI. The study, which featured a noninferiority design, included 668 stable patients with acute MI and anemia with a hemoglobin of 7-10 g/dL at 35 hospitals in France and Spain. Participants were randomized to a restrictive strategy in which transfusion was withheld unless the hemoglobin dropped to 8 g/dL or less, or to a conventional liberal strategy triggered by a hemoglobin of 10 g/dL or lower. The transfusion target was a hemoglobin level of 8-10 g/dL in the restrictive strategy group and greater than 11 g/dL in the liberal transfusion group. In the restrictive transfusion group, 36% received at least one RBC transfusion, as did 87% in the liberal transfusion study arm. The restrictive strategy group used 414 fewer units of blood.

The two coprimary endpoints were 30-day major adverse cardiovascular events and cost-effectiveness. The 30-day composite of all-cause mortality, reinfarction, stroke, and emergency percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial ischemia occurred in 11% of the restrictive transfusion group and 14% of the liberal transfusion group. The resultant 21% relative risk reduction established that the restrictive strategy was noninferior. Of note, all of the individual components of the composite endpoint numerically favored the restrictive approach.

In terms of safety, patients in the restrictive transfusion group were significantly less likely to develop an infection, by a margin of 0% versus 1.5%. The rate of acute lung injury was also significantly lower in the restrictive group: 0.3%, compared with 2.2%. The median hospital length of stay was identical at 7 days in both groups.

The cost-effectiveness analysis concluded that the restrictive transfusion strategy had an 84% probability of being both less expensive and more effective.

Patients were enrolled in REALITY regardless of whether they had active bleeding, as long as the bleeding wasn’t deemed massive and life-threatening. Notably, there was no difference in the results of restrictive versus liberal transfusion regardless of whether active bleeding was present, nor did baseline hemoglobin or the presence or absence of preexisting anemia affect the results.

Dr. Steg noted that a much larger randomized trial of restrictive versus liberal transfusion in the setting of acute MI with anemia is underway in the United States and Canada. The 3,000-patient MINT trial, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, is testing the superiority of restrictive transfusion, rather than its noninferiority, as in REALITY. Results are a couple of years away.

“I think that will be an important piece of additional evidence,” he said.

Discussant Marco Roffi, MD, didn’t mince words.

“I really love the REALITY trial,” declared Dr. Roffi, professor and vice chairman of the cardiology department and director of the interventional cardiology unit at University Hospital of Geneva.

He ticked off a series of reasons: The trial addressed a common clinical dilemma about which there has been essentially no prior high-quality evidence, it provided convincing results, and it carried important implications for responsible stewardship of the blood supply.

“REALITY allows clinicians to comfortably refrain from transfusing anemic patients presenting with myocardial infarction, and this should lead to a reduction in the consumption of blood products,” Dr. Roffi said.

He applauded the investigators for their success in obtaining public funding for a study lacking a commercial hook. And as a clinical investigator, he was particularly impressed by one of the technical details about the REALITY trial: “I was amazed by the fact that the observed event rates virtually corresponded to the estimated ones used for the power calculations. This is rarely the case in such a trial.”

Dr. Roffi said the REALITY findings should have an immediate impact on clinical practice, as well as on the brand new 2020 ESC guidelines on the management of non–ST-elevation ACS issued during the ESC virtual congress.

The freshly inked guidelines state: “Based on inconsistent study results and the lack of adequately powered randomized, controlled trials, a restrictive policy of transfusion in anemic patients with MI may be considered.” As of today, Dr. Roffi argued, the phrase “may be considered” ought to be replaced by the stronger phrase “should be considered.”

During the discussion period, he was asked if it’s appropriate to extrapolate the REALITY results to patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, among whom anemia is highly prevalent.

“I think this is a different patient population. Nevertheless, the concept of being restrictive is one that in my opinion now remains until proven otherwise. So we are being very restrictive in these patients,” he replied.

Asked about possible mechanisms by which liberal transfusion might have detrimental effects in acute MI patients, Dr. Steg cited several, including evidence that transfusion may not improve oxygen delivery to as great an extent as traditionally thought. There is also the risk of volume overload, increased blood viscosity, and enhanced platelet aggregation and activation, which could promote myocardial ischemia.

The REALITY trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness with no commercial support. Outside the scope of the trial, Dr. Steg reported receiving research grants from Bayer, Merck, Servier, and Sanofi as well as serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

in the landmark REALITY trial.

Randomized trial data already support a restrictive transfusion strategy in patients undergoing cardiac and noncardiac surgery, as well as in other settings. Those trials deliberately excluded patients with acute myocardial ischemia.

Cardiologists have been loath to adopt a restrictive strategy in the absence of persuasive supporting evidence because of a theoretic concern that low hemoglobin might be particularly harmful to ischemic myocardium. Anemia occurs in 5%-10% patients with MI, and clinicians have been eager for evidence-based guidance on how to best manage it.

“Blood is a precious resource and transfusion is costly, logistically cumbersome, and has side effects,” Philippe Gabriel Steg, MD, chair of the REALITY trial, noted in presenting the study results at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

REALITY was the first-ever large randomized trial of a restrictive versus liberal transfusion strategy in acute MI. The study, which featured a noninferiority design, included 668 stable patients with acute MI and anemia with a hemoglobin of 7-10 g/dL at 35 hospitals in France and Spain. Participants were randomized to a restrictive strategy in which transfusion was withheld unless the hemoglobin dropped to 8 g/dL or less, or to a conventional liberal strategy triggered by a hemoglobin of 10 g/dL or lower. The transfusion target was a hemoglobin level of 8-10 g/dL in the restrictive strategy group and greater than 11 g/dL in the liberal transfusion group. In the restrictive transfusion group, 36% received at least one RBC transfusion, as did 87% in the liberal transfusion study arm. The restrictive strategy group used 414 fewer units of blood.

The two coprimary endpoints were 30-day major adverse cardiovascular events and cost-effectiveness. The 30-day composite of all-cause mortality, reinfarction, stroke, and emergency percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial ischemia occurred in 11% of the restrictive transfusion group and 14% of the liberal transfusion group. The resultant 21% relative risk reduction established that the restrictive strategy was noninferior. Of note, all of the individual components of the composite endpoint numerically favored the restrictive approach.

In terms of safety, patients in the restrictive transfusion group were significantly less likely to develop an infection, by a margin of 0% versus 1.5%. The rate of acute lung injury was also significantly lower in the restrictive group: 0.3%, compared with 2.2%. The median hospital length of stay was identical at 7 days in both groups.

The cost-effectiveness analysis concluded that the restrictive transfusion strategy had an 84% probability of being both less expensive and more effective.

Patients were enrolled in REALITY regardless of whether they had active bleeding, as long as the bleeding wasn’t deemed massive and life-threatening. Notably, there was no difference in the results of restrictive versus liberal transfusion regardless of whether active bleeding was present, nor did baseline hemoglobin or the presence or absence of preexisting anemia affect the results.

Dr. Steg noted that a much larger randomized trial of restrictive versus liberal transfusion in the setting of acute MI with anemia is underway in the United States and Canada. The 3,000-patient MINT trial, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, is testing the superiority of restrictive transfusion, rather than its noninferiority, as in REALITY. Results are a couple of years away.

“I think that will be an important piece of additional evidence,” he said.

Discussant Marco Roffi, MD, didn’t mince words.

“I really love the REALITY trial,” declared Dr. Roffi, professor and vice chairman of the cardiology department and director of the interventional cardiology unit at University Hospital of Geneva.

He ticked off a series of reasons: The trial addressed a common clinical dilemma about which there has been essentially no prior high-quality evidence, it provided convincing results, and it carried important implications for responsible stewardship of the blood supply.

“REALITY allows clinicians to comfortably refrain from transfusing anemic patients presenting with myocardial infarction, and this should lead to a reduction in the consumption of blood products,” Dr. Roffi said.

He applauded the investigators for their success in obtaining public funding for a study lacking a commercial hook. And as a clinical investigator, he was particularly impressed by one of the technical details about the REALITY trial: “I was amazed by the fact that the observed event rates virtually corresponded to the estimated ones used for the power calculations. This is rarely the case in such a trial.”

Dr. Roffi said the REALITY findings should have an immediate impact on clinical practice, as well as on the brand new 2020 ESC guidelines on the management of non–ST-elevation ACS issued during the ESC virtual congress.

The freshly inked guidelines state: “Based on inconsistent study results and the lack of adequately powered randomized, controlled trials, a restrictive policy of transfusion in anemic patients with MI may be considered.” As of today, Dr. Roffi argued, the phrase “may be considered” ought to be replaced by the stronger phrase “should be considered.”

During the discussion period, he was asked if it’s appropriate to extrapolate the REALITY results to patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, among whom anemia is highly prevalent.

“I think this is a different patient population. Nevertheless, the concept of being restrictive is one that in my opinion now remains until proven otherwise. So we are being very restrictive in these patients,” he replied.

Asked about possible mechanisms by which liberal transfusion might have detrimental effects in acute MI patients, Dr. Steg cited several, including evidence that transfusion may not improve oxygen delivery to as great an extent as traditionally thought. There is also the risk of volume overload, increased blood viscosity, and enhanced platelet aggregation and activation, which could promote myocardial ischemia.

The REALITY trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness with no commercial support. Outside the scope of the trial, Dr. Steg reported receiving research grants from Bayer, Merck, Servier, and Sanofi as well as serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM ESC CONGRESS 2020

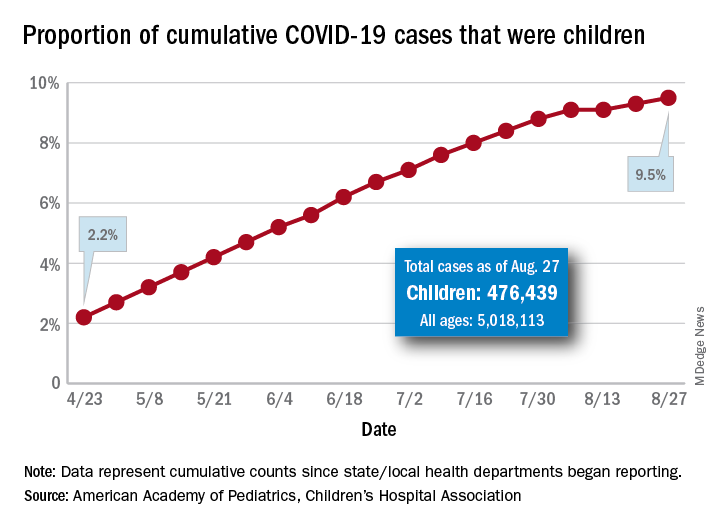

Latest report adds almost 44,000 child COVID-19 cases in 1 week

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

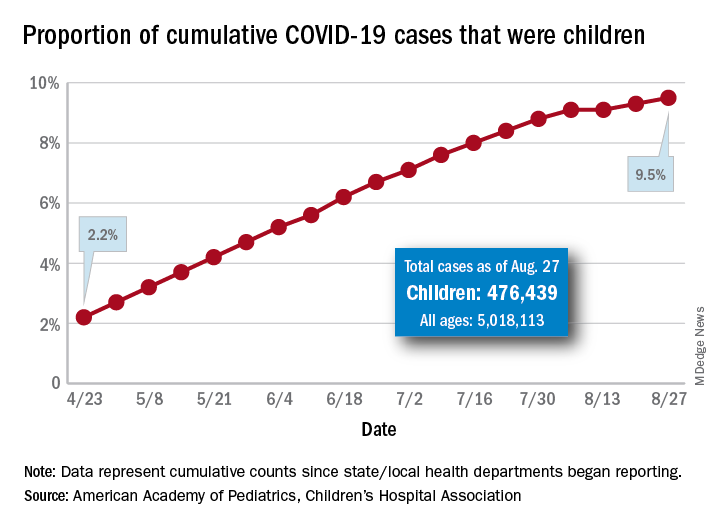

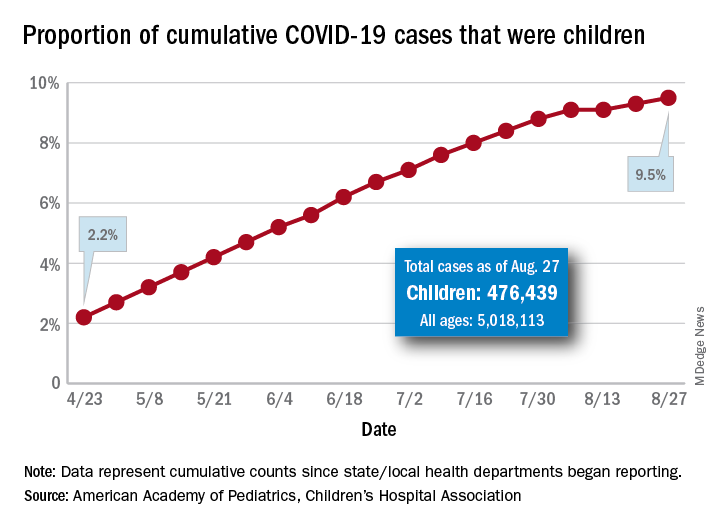

The new cases bring the cumulative number of infected children to over 476,000, and that figure represents 9.5% of the over 5 million COVID-19 cases reported among all ages, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report. The cumulative number of children covers 49 states (New York is not reporting age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

From lowest to highest, the states occupying opposite ends of the cumulative proportion spectrum are New Jersey at 3.4% – New York City was lower with a 3.2% figure but is not a state – and Wyoming at 18.3%, the report showed.

Children represent more than 15% of all reported COVID-19 cases in five other states: Tennessee (17.1%), North Dakota (16.0%), Alaska (15.9%), New Mexico (15.7%), and Minnesota (15.1%). The states just above New Jersey are Florida (5.8%), Connecticut (5.9%), and Massachusetts (6.7%). Texas has a rate of 5.6% but has reported age for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Children make up a much lower share of COVID-19 hospitalizations – 1.7% of the cumulative number for all ages – although that figure has been slowly rising over the course of the pandemic: it was 1.2% on July 9 and 0.9% on May 8. Arizona (4.1%) is the highest of the 22 states reporting age for hospitalizations and Hawaii (0.6%) is the lowest, based on the AAP/CHA data.

Mortality figures for children continue to be even lower. Nationwide, 0.07% of all COVID-19 deaths occurred in children, and 19 of the 43 states reporting age distributions have had no deaths yet. Pediatric deaths totaled 101 as of Aug. 27, the two groups reported.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The new cases bring the cumulative number of infected children to over 476,000, and that figure represents 9.5% of the over 5 million COVID-19 cases reported among all ages, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report. The cumulative number of children covers 49 states (New York is not reporting age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

From lowest to highest, the states occupying opposite ends of the cumulative proportion spectrum are New Jersey at 3.4% – New York City was lower with a 3.2% figure but is not a state – and Wyoming at 18.3%, the report showed.

Children represent more than 15% of all reported COVID-19 cases in five other states: Tennessee (17.1%), North Dakota (16.0%), Alaska (15.9%), New Mexico (15.7%), and Minnesota (15.1%). The states just above New Jersey are Florida (5.8%), Connecticut (5.9%), and Massachusetts (6.7%). Texas has a rate of 5.6% but has reported age for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Children make up a much lower share of COVID-19 hospitalizations – 1.7% of the cumulative number for all ages – although that figure has been slowly rising over the course of the pandemic: it was 1.2% on July 9 and 0.9% on May 8. Arizona (4.1%) is the highest of the 22 states reporting age for hospitalizations and Hawaii (0.6%) is the lowest, based on the AAP/CHA data.

Mortality figures for children continue to be even lower. Nationwide, 0.07% of all COVID-19 deaths occurred in children, and 19 of the 43 states reporting age distributions have had no deaths yet. Pediatric deaths totaled 101 as of Aug. 27, the two groups reported.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The new cases bring the cumulative number of infected children to over 476,000, and that figure represents 9.5% of the over 5 million COVID-19 cases reported among all ages, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report. The cumulative number of children covers 49 states (New York is not reporting age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

From lowest to highest, the states occupying opposite ends of the cumulative proportion spectrum are New Jersey at 3.4% – New York City was lower with a 3.2% figure but is not a state – and Wyoming at 18.3%, the report showed.

Children represent more than 15% of all reported COVID-19 cases in five other states: Tennessee (17.1%), North Dakota (16.0%), Alaska (15.9%), New Mexico (15.7%), and Minnesota (15.1%). The states just above New Jersey are Florida (5.8%), Connecticut (5.9%), and Massachusetts (6.7%). Texas has a rate of 5.6% but has reported age for only 8% of confirmed cases, the AAP and CHA noted.

Children make up a much lower share of COVID-19 hospitalizations – 1.7% of the cumulative number for all ages – although that figure has been slowly rising over the course of the pandemic: it was 1.2% on July 9 and 0.9% on May 8. Arizona (4.1%) is the highest of the 22 states reporting age for hospitalizations and Hawaii (0.6%) is the lowest, based on the AAP/CHA data.

Mortality figures for children continue to be even lower. Nationwide, 0.07% of all COVID-19 deaths occurred in children, and 19 of the 43 states reporting age distributions have had no deaths yet. Pediatric deaths totaled 101 as of Aug. 27, the two groups reported.

First randomized trial reassures on ACEIs, ARBs in COVID-19

The first randomized study to compare continuing versus stopping ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients with COVID-19 has shown no difference in key outcomes between the two approaches.

The BRACE CORONA trial – conducted in patients had been taking an ACE inhibitor or an ARB on a long-term basis and who were subsequently hospitalized with COVID-19 – showed no difference in the primary endpoint of number of days alive and out of hospital among those whose medication was suspended for 30 days and those who continued undergoing treatment with these agents.

“Because these data indicate that there is no clinical benefit from routinely interrupting these medications in hospitalized patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, they should generally be continued for those with an indication,” principal investigator Renato Lopes, MD, of Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., concluded.

The BRACE CORONA trial was presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 on Sept. 1.

Dr. Lopes explained that there are two conflicting hypotheses about the role of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in COVID-19.

One hypothesis suggests that use of these drugs could be harmful by increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors (which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells), thus potentially enhancing viral binding and viral entry. The other suggests that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be protective by reducing production of angiotensin II and enhancing the generation of angiotensin 1-7, which attenuates inflammation and fibrosis and therefore could attenuate lung injury.

The BRACE CORONA trial was an academic-led randomized study that tested two strategies: temporarily stopping the ACE inhibitor/ARB for 30 days or continuing these drugs for patients who had been taking these medications on a long-term basis and were hospitalized with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

The primary outcome was the number of days alive and out of hospital at 30 days. Patients who were using more than three antihypertensive drugs or sacubitril/valsartan or who were hemodynamically unstable at presentation were excluded from the study.

The trial enrolled 659 patients from 29 sites in Brazil. The mean age of patients was 56 years, 40% were women, and 52% were obese. ACE inhibitors were being taken by 15% of the trial participants; ARBs were being taken by 85%. The median duration of ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment was 5 years.

Patients were a median of 6 days from COVID-19 symptom onset. For 30% of the patients, oxygen saturation was below 94% at entry. In terms of COVID-19 symptoms, 57% were classified as mild, and 43% as moderate.

Those with severe COVID-19 symptoms who needed intubation or vasoactive drugs were excluded. Antihypertensive therapy would generally be discontinued in these patients anyway, Dr. Lopes said.

Results showed that the average number of days alive and out of hospital was 21.9 days for patients who stopped taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 22.9 days for patients who continued taking these medications. The average difference between groups was –1.1 days.

The average ratio of days alive and out of hospital between the suspending and continuing groups was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90-1.01; P = .09).

The proportion of patients alive and out of hospital by the end of 30 days in the suspending ACE inhibitor/ARB group was 91.8% versus 95% in the continuing group.

A similar 30-day mortality rate was seen for patients who continued and those who suspended ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy, at 2.8% and 2.7%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.97). The median number of days that patients were alive and out of hospital was 25 in both groups.

Dr. Lopes said that there was no difference between the two groups with regard to many other secondary outcomes. These included COVID-19 disease progression (need for intubation, ventilation, need for vasoactive drugs, or imaging results) and cardiovascular endpoints (MI, stroke, thromboembolic events, worsening heart failure, myocarditis, or hypertensive crisis).

“Our results endorse with reliable and more definitive data what most medical and cardiovascular societies are recommending – that patients do not stop ACE inhibitor or ARB medication. This has been based on observational data so far, but BRACE CORONA now provides randomized data to support this recommendation,” Dr. Lopes concluded.

Dr. Lopes noted that several subgroups had been prespecified for analysis. Factors included age, obesity, difference between ACE inhibitors/ARBs, difference in oxygen saturation at presentation, time since COVID-19 symptom onset, degree of lung involvement on CT, and symptom severity on presentation.

“We saw very consistent effects of our main findings across all these subgroups, and we plan to report more details of these in the near future,” he said.

Protective for older patients?

The discussant of the study at the ESC Hotline session, Gianfranco Parati, MD, University of Milan-Bicocca and San Luca Hospital, Milan, congratulated Lopes and his team for conducting this important trial at such a difficult time.

He pointed out that patients in the BRACE CORONA trial were quite young (average age, 56 years) and that observational data so far suggest that ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a stronger protective effect in older COVID-19 patients.

He also noted that the percentage of patients alive and out of hospital at 30 days was higher for the patients who continued on treatment in this study (95% vs. 91.8%), which suggested an advantage in maintaining the medication.

Dr. Lopes replied that one-quarter of the population in the BRACE CORONA trial was older than 65 years, which he said was a “reasonable number.”

“Subgroup analysis by age did not show a significant interaction, but the effect of continuing treatment does seem to be more favorable in older patients and also in those who were sicker and had more comorbidities,” he added.

Dr. Parati also suggested that it would have been difficult to discern differences between ACE inhibitors and ARBs in the BRACE CORONA trial, because so few patents were taking ACE inhibitors; the follow-up period of 30 days was relatively short, inasmuch as these drugs may have long-term effects; and it would have been difficult to show differences in the main outcomes used in the study – mortality and time out of hospital – in these patients with mild to moderate disease.

Franz H. Messerli, MD, and Christoph Gräni, MD, University of Bern (Switzerland), said in a joint statement: “The BRACE CORONA trial provides answers to what we know from retrospective studies: if you have already COVID, don’t stop renin-angiotensin system blocker medication.”

But they added that the study does not answer the question about the risk/benefit of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with regard to possible enhanced viral entry through the ACE2 receptor. “What about all those on these drugs who are not infected with COVID? Do they need to stop them? We simply don’t know yet,” they said.

Dr. Messerli and Dr. Gräni added that they would like to see a study that compared patients before SARS-CoV-2 infection who were without hypertension, patients with hypertension who were taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and patients with hypertension taking other antihypertensive drugs.

The BRACE CORONA trial was sponsored by D’Or Institute for Research and Education and the Brazilian Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Lopes has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The first randomized study to compare continuing versus stopping ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients with COVID-19 has shown no difference in key outcomes between the two approaches.

The BRACE CORONA trial – conducted in patients had been taking an ACE inhibitor or an ARB on a long-term basis and who were subsequently hospitalized with COVID-19 – showed no difference in the primary endpoint of number of days alive and out of hospital among those whose medication was suspended for 30 days and those who continued undergoing treatment with these agents.

“Because these data indicate that there is no clinical benefit from routinely interrupting these medications in hospitalized patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, they should generally be continued for those with an indication,” principal investigator Renato Lopes, MD, of Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., concluded.

The BRACE CORONA trial was presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 on Sept. 1.

Dr. Lopes explained that there are two conflicting hypotheses about the role of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in COVID-19.

One hypothesis suggests that use of these drugs could be harmful by increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors (which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells), thus potentially enhancing viral binding and viral entry. The other suggests that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be protective by reducing production of angiotensin II and enhancing the generation of angiotensin 1-7, which attenuates inflammation and fibrosis and therefore could attenuate lung injury.

The BRACE CORONA trial was an academic-led randomized study that tested two strategies: temporarily stopping the ACE inhibitor/ARB for 30 days or continuing these drugs for patients who had been taking these medications on a long-term basis and were hospitalized with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

The primary outcome was the number of days alive and out of hospital at 30 days. Patients who were using more than three antihypertensive drugs or sacubitril/valsartan or who were hemodynamically unstable at presentation were excluded from the study.

The trial enrolled 659 patients from 29 sites in Brazil. The mean age of patients was 56 years, 40% were women, and 52% were obese. ACE inhibitors were being taken by 15% of the trial participants; ARBs were being taken by 85%. The median duration of ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment was 5 years.

Patients were a median of 6 days from COVID-19 symptom onset. For 30% of the patients, oxygen saturation was below 94% at entry. In terms of COVID-19 symptoms, 57% were classified as mild, and 43% as moderate.

Those with severe COVID-19 symptoms who needed intubation or vasoactive drugs were excluded. Antihypertensive therapy would generally be discontinued in these patients anyway, Dr. Lopes said.

Results showed that the average number of days alive and out of hospital was 21.9 days for patients who stopped taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 22.9 days for patients who continued taking these medications. The average difference between groups was –1.1 days.

The average ratio of days alive and out of hospital between the suspending and continuing groups was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90-1.01; P = .09).

The proportion of patients alive and out of hospital by the end of 30 days in the suspending ACE inhibitor/ARB group was 91.8% versus 95% in the continuing group.

A similar 30-day mortality rate was seen for patients who continued and those who suspended ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy, at 2.8% and 2.7%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.97). The median number of days that patients were alive and out of hospital was 25 in both groups.

Dr. Lopes said that there was no difference between the two groups with regard to many other secondary outcomes. These included COVID-19 disease progression (need for intubation, ventilation, need for vasoactive drugs, or imaging results) and cardiovascular endpoints (MI, stroke, thromboembolic events, worsening heart failure, myocarditis, or hypertensive crisis).

“Our results endorse with reliable and more definitive data what most medical and cardiovascular societies are recommending – that patients do not stop ACE inhibitor or ARB medication. This has been based on observational data so far, but BRACE CORONA now provides randomized data to support this recommendation,” Dr. Lopes concluded.

Dr. Lopes noted that several subgroups had been prespecified for analysis. Factors included age, obesity, difference between ACE inhibitors/ARBs, difference in oxygen saturation at presentation, time since COVID-19 symptom onset, degree of lung involvement on CT, and symptom severity on presentation.

“We saw very consistent effects of our main findings across all these subgroups, and we plan to report more details of these in the near future,” he said.

Protective for older patients?

The discussant of the study at the ESC Hotline session, Gianfranco Parati, MD, University of Milan-Bicocca and San Luca Hospital, Milan, congratulated Lopes and his team for conducting this important trial at such a difficult time.

He pointed out that patients in the BRACE CORONA trial were quite young (average age, 56 years) and that observational data so far suggest that ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a stronger protective effect in older COVID-19 patients.

He also noted that the percentage of patients alive and out of hospital at 30 days was higher for the patients who continued on treatment in this study (95% vs. 91.8%), which suggested an advantage in maintaining the medication.

Dr. Lopes replied that one-quarter of the population in the BRACE CORONA trial was older than 65 years, which he said was a “reasonable number.”

“Subgroup analysis by age did not show a significant interaction, but the effect of continuing treatment does seem to be more favorable in older patients and also in those who were sicker and had more comorbidities,” he added.

Dr. Parati also suggested that it would have been difficult to discern differences between ACE inhibitors and ARBs in the BRACE CORONA trial, because so few patents were taking ACE inhibitors; the follow-up period of 30 days was relatively short, inasmuch as these drugs may have long-term effects; and it would have been difficult to show differences in the main outcomes used in the study – mortality and time out of hospital – in these patients with mild to moderate disease.

Franz H. Messerli, MD, and Christoph Gräni, MD, University of Bern (Switzerland), said in a joint statement: “The BRACE CORONA trial provides answers to what we know from retrospective studies: if you have already COVID, don’t stop renin-angiotensin system blocker medication.”

But they added that the study does not answer the question about the risk/benefit of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with regard to possible enhanced viral entry through the ACE2 receptor. “What about all those on these drugs who are not infected with COVID? Do they need to stop them? We simply don’t know yet,” they said.

Dr. Messerli and Dr. Gräni added that they would like to see a study that compared patients before SARS-CoV-2 infection who were without hypertension, patients with hypertension who were taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and patients with hypertension taking other antihypertensive drugs.

The BRACE CORONA trial was sponsored by D’Or Institute for Research and Education and the Brazilian Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Lopes has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The first randomized study to compare continuing versus stopping ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients with COVID-19 has shown no difference in key outcomes between the two approaches.

The BRACE CORONA trial – conducted in patients had been taking an ACE inhibitor or an ARB on a long-term basis and who were subsequently hospitalized with COVID-19 – showed no difference in the primary endpoint of number of days alive and out of hospital among those whose medication was suspended for 30 days and those who continued undergoing treatment with these agents.

“Because these data indicate that there is no clinical benefit from routinely interrupting these medications in hospitalized patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, they should generally be continued for those with an indication,” principal investigator Renato Lopes, MD, of Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., concluded.

The BRACE CORONA trial was presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 on Sept. 1.

Dr. Lopes explained that there are two conflicting hypotheses about the role of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in COVID-19.

One hypothesis suggests that use of these drugs could be harmful by increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors (which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells), thus potentially enhancing viral binding and viral entry. The other suggests that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be protective by reducing production of angiotensin II and enhancing the generation of angiotensin 1-7, which attenuates inflammation and fibrosis and therefore could attenuate lung injury.

The BRACE CORONA trial was an academic-led randomized study that tested two strategies: temporarily stopping the ACE inhibitor/ARB for 30 days or continuing these drugs for patients who had been taking these medications on a long-term basis and were hospitalized with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

The primary outcome was the number of days alive and out of hospital at 30 days. Patients who were using more than three antihypertensive drugs or sacubitril/valsartan or who were hemodynamically unstable at presentation were excluded from the study.

The trial enrolled 659 patients from 29 sites in Brazil. The mean age of patients was 56 years, 40% were women, and 52% were obese. ACE inhibitors were being taken by 15% of the trial participants; ARBs were being taken by 85%. The median duration of ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment was 5 years.

Patients were a median of 6 days from COVID-19 symptom onset. For 30% of the patients, oxygen saturation was below 94% at entry. In terms of COVID-19 symptoms, 57% were classified as mild, and 43% as moderate.

Those with severe COVID-19 symptoms who needed intubation or vasoactive drugs were excluded. Antihypertensive therapy would generally be discontinued in these patients anyway, Dr. Lopes said.

Results showed that the average number of days alive and out of hospital was 21.9 days for patients who stopped taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 22.9 days for patients who continued taking these medications. The average difference between groups was –1.1 days.

The average ratio of days alive and out of hospital between the suspending and continuing groups was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.90-1.01; P = .09).

The proportion of patients alive and out of hospital by the end of 30 days in the suspending ACE inhibitor/ARB group was 91.8% versus 95% in the continuing group.

A similar 30-day mortality rate was seen for patients who continued and those who suspended ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy, at 2.8% and 2.7%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.97). The median number of days that patients were alive and out of hospital was 25 in both groups.

Dr. Lopes said that there was no difference between the two groups with regard to many other secondary outcomes. These included COVID-19 disease progression (need for intubation, ventilation, need for vasoactive drugs, or imaging results) and cardiovascular endpoints (MI, stroke, thromboembolic events, worsening heart failure, myocarditis, or hypertensive crisis).

“Our results endorse with reliable and more definitive data what most medical and cardiovascular societies are recommending – that patients do not stop ACE inhibitor or ARB medication. This has been based on observational data so far, but BRACE CORONA now provides randomized data to support this recommendation,” Dr. Lopes concluded.

Dr. Lopes noted that several subgroups had been prespecified for analysis. Factors included age, obesity, difference between ACE inhibitors/ARBs, difference in oxygen saturation at presentation, time since COVID-19 symptom onset, degree of lung involvement on CT, and symptom severity on presentation.

“We saw very consistent effects of our main findings across all these subgroups, and we plan to report more details of these in the near future,” he said.

Protective for older patients?

The discussant of the study at the ESC Hotline session, Gianfranco Parati, MD, University of Milan-Bicocca and San Luca Hospital, Milan, congratulated Lopes and his team for conducting this important trial at such a difficult time.

He pointed out that patients in the BRACE CORONA trial were quite young (average age, 56 years) and that observational data so far suggest that ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a stronger protective effect in older COVID-19 patients.

He also noted that the percentage of patients alive and out of hospital at 30 days was higher for the patients who continued on treatment in this study (95% vs. 91.8%), which suggested an advantage in maintaining the medication.

Dr. Lopes replied that one-quarter of the population in the BRACE CORONA trial was older than 65 years, which he said was a “reasonable number.”

“Subgroup analysis by age did not show a significant interaction, but the effect of continuing treatment does seem to be more favorable in older patients and also in those who were sicker and had more comorbidities,” he added.

Dr. Parati also suggested that it would have been difficult to discern differences between ACE inhibitors and ARBs in the BRACE CORONA trial, because so few patents were taking ACE inhibitors; the follow-up period of 30 days was relatively short, inasmuch as these drugs may have long-term effects; and it would have been difficult to show differences in the main outcomes used in the study – mortality and time out of hospital – in these patients with mild to moderate disease.

Franz H. Messerli, MD, and Christoph Gräni, MD, University of Bern (Switzerland), said in a joint statement: “The BRACE CORONA trial provides answers to what we know from retrospective studies: if you have already COVID, don’t stop renin-angiotensin system blocker medication.”

But they added that the study does not answer the question about the risk/benefit of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with regard to possible enhanced viral entry through the ACE2 receptor. “What about all those on these drugs who are not infected with COVID? Do they need to stop them? We simply don’t know yet,” they said.

Dr. Messerli and Dr. Gräni added that they would like to see a study that compared patients before SARS-CoV-2 infection who were without hypertension, patients with hypertension who were taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and patients with hypertension taking other antihypertensive drugs.

The BRACE CORONA trial was sponsored by D’Or Institute for Research and Education and the Brazilian Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Lopes has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Pandemic worsens disparities in GI and liver disease

Suspension of disease screening and nonurgent procedures because of the COVID-19 pandemic will negatively impact long-term outcomes of GI and liver disease, and people of color will be disproportionately affected, according to a leading expert.

Novel, multipronged approaches are needed to overcome widening disparities in gastroenterology and hepatology, said Rachel Issaka, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented drops in breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer screenings,” Dr. Issaka said during an AGA FORWARD Program webinar. Screening rates for these diseases are down 83%-90%, she said.

“Certainly this creates a backlog of cancer screenings that need to occur, which poses very significant challenges for health systems as they’re adapting to this new state of health care that we have to provide,” Dr. Issaka said.

During her presentation, Dr. Issaka first addressed pandemic-related issues in colorectal cancer (CRC).

The sudden decrease in colonoscopies has already affected diagnoses, she said, as 32% fewer cases of CRC were diagnosed in April 2020 compared with April 2019, a finding that is “obviously very concerning.” All downstream effects remain to be seen; however, one estimate suggests that over the next decade, delayed screening may lead to an additional 4,500 deaths from CRC.

“These effects are particularly noticeable in medically underserved communities where CRC morbidity and mortality are highest,” Dr. Issaka wrote, as coauthor of a study published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Dr. Issaka and colleagues predict that the pandemic will likely worsen “persistent CRC disparities” in African-American and Hispanic communities, including relatively decreased screening participation, delayed follow-up of abnormal stool results, limited community-based research and partnerships, and limited community engagement and advocacy.

“COVID-19 related pauses in medical care, as well as shifts in resource allocation and workforce deployment, threaten decades worth of work to improve CRC disparities in medically underserved populations,” wrote Dr. Issaka and colleagues.

Dr. Issaka described similar issues in hepatology. She referred to a recent opinion article by Tapper and colleagues, which predicted that the COVID-19 pandemic will impact patients with liver disease in three waves: first, by delaying liver transplants, elective procedures, imaging, and routine patient follow-up; second, by increasing emergent decompensations, transplant wait-list dropouts, and care deferrals; and third, by losing patients to follow-up, resulting in missed diagnoses, incomplete cancer screening, and progressive disease.

“This could disproportionately impact Black, Hispanic, and Native-American populations, who may have already had difficulty accessing [liver care],” Dr. Issaka said.

To mitigate growing disparities, Dr. Issaka proposed a variety of strategies for CRC and liver disease.

For CRC screening, Dr. Issaka suggested noninvasive modalities, including mailed fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), with focused follow-up on patients with highest FIT values. For those conducting CRC research, Dr. Issaka recommended using accessible technology, engaging with community partners, providing incentives where appropriate, and other methods. For cirrhosis care, Dr. Issaka suggested that practitioners turn to telehealth and remote care, including weight monitoring, cognitive function testing, home medication delivery, and online education.

More broadly, Dr. Issaka called for universal health insurance not associated with employment, research funding for health disparities, sustainable employment wages, climate justice, desegregation of housing, and universal broadband Internet.

“The solutions to these problems are multipronged,” Dr. Issaka said. “Some will happen locally; for instance, well-executed planning around telehealth. Some will happen at the state level through opportunities like advocacy or even just reaching out to your own [congressional representative]. And then some will also happen programmatically – How can we as a health system begin to leverage something like mailed FIT?”

Finally, Dr. Issaka suggested that tools from another branch of science can help improve screening rates.

“We don’t, in medicine, tap into the benefits of behavioral psychology enough,” she said. “That’s a great discipline with really great tools that we can all use.”

Dr. Issaka described the power of community, in that people are more likely to undergo screening if they know how many others in their community are also being screened.

“I think as much as we can gather those kinds of data and share those with individuals to provide reassurance about the safety and importance of screening, I think [that] will help,” she said.

The AGA FORWARD program is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (DK118761). Dr. Issaka has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Issaka. AGA FORWARD Program Webinar. 2020 Aug 27; Balzora et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020 June 20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.042; Tapper et al. Journal of Hepatology. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.005.

Suspension of disease screening and nonurgent procedures because of the COVID-19 pandemic will negatively impact long-term outcomes of GI and liver disease, and people of color will be disproportionately affected, according to a leading expert.

Novel, multipronged approaches are needed to overcome widening disparities in gastroenterology and hepatology, said Rachel Issaka, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented drops in breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer screenings,” Dr. Issaka said during an AGA FORWARD Program webinar. Screening rates for these diseases are down 83%-90%, she said.

“Certainly this creates a backlog of cancer screenings that need to occur, which poses very significant challenges for health systems as they’re adapting to this new state of health care that we have to provide,” Dr. Issaka said.

During her presentation, Dr. Issaka first addressed pandemic-related issues in colorectal cancer (CRC).

The sudden decrease in colonoscopies has already affected diagnoses, she said, as 32% fewer cases of CRC were diagnosed in April 2020 compared with April 2019, a finding that is “obviously very concerning.” All downstream effects remain to be seen; however, one estimate suggests that over the next decade, delayed screening may lead to an additional 4,500 deaths from CRC.

“These effects are particularly noticeable in medically underserved communities where CRC morbidity and mortality are highest,” Dr. Issaka wrote, as coauthor of a study published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Dr. Issaka and colleagues predict that the pandemic will likely worsen “persistent CRC disparities” in African-American and Hispanic communities, including relatively decreased screening participation, delayed follow-up of abnormal stool results, limited community-based research and partnerships, and limited community engagement and advocacy.

“COVID-19 related pauses in medical care, as well as shifts in resource allocation and workforce deployment, threaten decades worth of work to improve CRC disparities in medically underserved populations,” wrote Dr. Issaka and colleagues.

Dr. Issaka described similar issues in hepatology. She referred to a recent opinion article by Tapper and colleagues, which predicted that the COVID-19 pandemic will impact patients with liver disease in three waves: first, by delaying liver transplants, elective procedures, imaging, and routine patient follow-up; second, by increasing emergent decompensations, transplant wait-list dropouts, and care deferrals; and third, by losing patients to follow-up, resulting in missed diagnoses, incomplete cancer screening, and progressive disease.

“This could disproportionately impact Black, Hispanic, and Native-American populations, who may have already had difficulty accessing [liver care],” Dr. Issaka said.

To mitigate growing disparities, Dr. Issaka proposed a variety of strategies for CRC and liver disease.

For CRC screening, Dr. Issaka suggested noninvasive modalities, including mailed fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), with focused follow-up on patients with highest FIT values. For those conducting CRC research, Dr. Issaka recommended using accessible technology, engaging with community partners, providing incentives where appropriate, and other methods. For cirrhosis care, Dr. Issaka suggested that practitioners turn to telehealth and remote care, including weight monitoring, cognitive function testing, home medication delivery, and online education.

More broadly, Dr. Issaka called for universal health insurance not associated with employment, research funding for health disparities, sustainable employment wages, climate justice, desegregation of housing, and universal broadband Internet.

“The solutions to these problems are multipronged,” Dr. Issaka said. “Some will happen locally; for instance, well-executed planning around telehealth. Some will happen at the state level through opportunities like advocacy or even just reaching out to your own [congressional representative]. And then some will also happen programmatically – How can we as a health system begin to leverage something like mailed FIT?”

Finally, Dr. Issaka suggested that tools from another branch of science can help improve screening rates.

“We don’t, in medicine, tap into the benefits of behavioral psychology enough,” she said. “That’s a great discipline with really great tools that we can all use.”

Dr. Issaka described the power of community, in that people are more likely to undergo screening if they know how many others in their community are also being screened.

“I think as much as we can gather those kinds of data and share those with individuals to provide reassurance about the safety and importance of screening, I think [that] will help,” she said.

The AGA FORWARD program is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (DK118761). Dr. Issaka has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Issaka. AGA FORWARD Program Webinar. 2020 Aug 27; Balzora et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020 June 20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.042; Tapper et al. Journal of Hepatology. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.005.

Suspension of disease screening and nonurgent procedures because of the COVID-19 pandemic will negatively impact long-term outcomes of GI and liver disease, and people of color will be disproportionately affected, according to a leading expert.

Novel, multipronged approaches are needed to overcome widening disparities in gastroenterology and hepatology, said Rachel Issaka, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented drops in breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer screenings,” Dr. Issaka said during an AGA FORWARD Program webinar. Screening rates for these diseases are down 83%-90%, she said.

“Certainly this creates a backlog of cancer screenings that need to occur, which poses very significant challenges for health systems as they’re adapting to this new state of health care that we have to provide,” Dr. Issaka said.

During her presentation, Dr. Issaka first addressed pandemic-related issues in colorectal cancer (CRC).

The sudden decrease in colonoscopies has already affected diagnoses, she said, as 32% fewer cases of CRC were diagnosed in April 2020 compared with April 2019, a finding that is “obviously very concerning.” All downstream effects remain to be seen; however, one estimate suggests that over the next decade, delayed screening may lead to an additional 4,500 deaths from CRC.

“These effects are particularly noticeable in medically underserved communities where CRC morbidity and mortality are highest,” Dr. Issaka wrote, as coauthor of a study published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Dr. Issaka and colleagues predict that the pandemic will likely worsen “persistent CRC disparities” in African-American and Hispanic communities, including relatively decreased screening participation, delayed follow-up of abnormal stool results, limited community-based research and partnerships, and limited community engagement and advocacy.

“COVID-19 related pauses in medical care, as well as shifts in resource allocation and workforce deployment, threaten decades worth of work to improve CRC disparities in medically underserved populations,” wrote Dr. Issaka and colleagues.

Dr. Issaka described similar issues in hepatology. She referred to a recent opinion article by Tapper and colleagues, which predicted that the COVID-19 pandemic will impact patients with liver disease in three waves: first, by delaying liver transplants, elective procedures, imaging, and routine patient follow-up; second, by increasing emergent decompensations, transplant wait-list dropouts, and care deferrals; and third, by losing patients to follow-up, resulting in missed diagnoses, incomplete cancer screening, and progressive disease.

“This could disproportionately impact Black, Hispanic, and Native-American populations, who may have already had difficulty accessing [liver care],” Dr. Issaka said.

To mitigate growing disparities, Dr. Issaka proposed a variety of strategies for CRC and liver disease.

For CRC screening, Dr. Issaka suggested noninvasive modalities, including mailed fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), with focused follow-up on patients with highest FIT values. For those conducting CRC research, Dr. Issaka recommended using accessible technology, engaging with community partners, providing incentives where appropriate, and other methods. For cirrhosis care, Dr. Issaka suggested that practitioners turn to telehealth and remote care, including weight monitoring, cognitive function testing, home medication delivery, and online education.

More broadly, Dr. Issaka called for universal health insurance not associated with employment, research funding for health disparities, sustainable employment wages, climate justice, desegregation of housing, and universal broadband Internet.

“The solutions to these problems are multipronged,” Dr. Issaka said. “Some will happen locally; for instance, well-executed planning around telehealth. Some will happen at the state level through opportunities like advocacy or even just reaching out to your own [congressional representative]. And then some will also happen programmatically – How can we as a health system begin to leverage something like mailed FIT?”

Finally, Dr. Issaka suggested that tools from another branch of science can help improve screening rates.

“We don’t, in medicine, tap into the benefits of behavioral psychology enough,” she said. “That’s a great discipline with really great tools that we can all use.”

Dr. Issaka described the power of community, in that people are more likely to undergo screening if they know how many others in their community are also being screened.

“I think as much as we can gather those kinds of data and share those with individuals to provide reassurance about the safety and importance of screening, I think [that] will help,” she said.

The AGA FORWARD program is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (DK118761). Dr. Issaka has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Issaka. AGA FORWARD Program Webinar. 2020 Aug 27; Balzora et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2020 June 20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.042; Tapper et al. Journal of Hepatology. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.005.

FROM THE AGA FORWARD PROGRAM

Obesity boosts risks in COVID-19 from diagnosis to death

A new analysis of existing research confirms a stark link between excess weight and COVID-19:

Obese patients faced the greatest bump in risk on the hospitalization front, with their odds of being admitted listed as 113% higher. The odds of diagnosis, ICU admission, and death were 46% higher (odds ratio [OR], 1.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.30-1.65; P < .0001); 74% higher (OR, 1.74, CI, 1.46-2.08, P < .0001); 48% (OR, 1.48, CI, 1.22–1.80, P < .001, all pooled analyses and 95% CI), respectively. All differences were highly significantly different, investigators reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis published online Aug. 26 in Obesity Reviews.

“Essentially, these are pretty scary statistics,” nutrition researcher and study lead author Barry M. Popkin, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Public Health, said in an interview. “Other studies have talked about an increase in mortality, and we were thinking there’d be a little increase like 10% – nothing like 48%.”

According to the Johns Hopkins University of Medicine tracker, nearly 6 million people in the United States had been diagnosed with COVID-19 as of Aug. 30. The number of deaths had surpassed 183,000.

The authors of the new review launched their project to better understand the link between obesity and COVID-19 “all the way from being diagnosed to death,” Dr. Popkin said, adding that the meta-analysis is the largest of its kind to examine the link.

Dr. Popkin and colleagues analyzed 75 studies during January to June 2020 that tracked 399,461 patients (55% of whom were male) diagnosed with COVID-19. They found that 18 of 20 studies linked obesity with a 46% higher risk of diagnosis, but Dr. Popkin cautioned that this may be misleading. “I suspect it’s because they’re sicker and getting tested more for COVID,” he said. “I don’t think obesity enhances your likelihood of getting COVID. We don’t have a biological rationale for that.”

The researchers examined 19 studies that explored a link between obesity and hospitalization; all 19 found a higher risk of hospitalization in patients with obesity (pooled OR, 2.13). Twenty-one of 22 studies that looked at ICU admissions discovered a higher risk for patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.74). And 27 of 35 studies that examined COVID-19 mortality found a higher death rate in patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.48).

The review also looked at 14 studies that examined links between obesity and administration of invasive mechanical ventilation. All the studies found a higher risk for patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.38-1.99; P < .0001).

Could socioeconomic factors explain the difference in risk for people with obesity? It’s not clear. According to Dr. Popkin, most of the studies don’t examine factors such as income. While he believes physical factors are the key to the higher risk, he said “there’s clearly a social side to this.”

On the biological front, it appears that “the immune system is much weaker if you’re obese,” he said, and excess weight may worsen the course of a respiratory disease such as COVID-19 because of lung disorders such as sleep apnea.

In addition to highlighting inflammation and a weakened immune system, the review offers multiple explanations for why patients with obesity face worse outcomes in COVID-19. It may be more difficult for medical professionals to care for them in the hospital because of their weight, the authors wrote, and “obesity may also impair therapeutic treatments during COVID-19 infections.” The authors noted that ACE inhibitors may worsen COVID-19 in patients with type 2 diabetes.

The researchers noted that “potentially the vaccines developed to address COVID-19 will be less effective for individuals with obesity due to a weakened immune response.” They pointed to research that suggests T-cell responses are weaker and antibody titers wane at a faster rate in people with obesity who are vaccinated against influenza.

Pulmonologist Joshua L. Denson, MD, MS, of Tulane University, New Orleans, praised the review in an interview, but noted that some of the included studies have wide confidence intervals. One study that links COVID-19 to a sixfold higher mortality rate (OR, 6.29) has a confidence interval of 1.76-22.45.

Dr. Denson said he’s seen about 100 patients with COVID-19, and many are obese and have metabolic syndrome.

Like the authors of the study, he believes higher levels of inflammation play a crucial role in making these patients more vulnerable. “For whatever reason, the virus tends to really like that state. That’s driving these people to get sick,” he said.

Moving forward, Dr. Popkin urged physicians to redouble their efforts to warn patients about the risks of obesity and the importance of healthy eating. He also said COVID-19 vaccine researchers must stratify obese vs. nonobese subjects in clinical trials.

The review was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Carolina Population Center, World Bank, and Saudi Health Council. The review authors report no relevant disclosures. Dr. Denson reports no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Popkin BM et al. Obes Rev. 2020 Aug 26. doi: 10.1111/obr.13128.

A new analysis of existing research confirms a stark link between excess weight and COVID-19:

Obese patients faced the greatest bump in risk on the hospitalization front, with their odds of being admitted listed as 113% higher. The odds of diagnosis, ICU admission, and death were 46% higher (odds ratio [OR], 1.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.30-1.65; P < .0001); 74% higher (OR, 1.74, CI, 1.46-2.08, P < .0001); 48% (OR, 1.48, CI, 1.22–1.80, P < .001, all pooled analyses and 95% CI), respectively. All differences were highly significantly different, investigators reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis published online Aug. 26 in Obesity Reviews.

“Essentially, these are pretty scary statistics,” nutrition researcher and study lead author Barry M. Popkin, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Public Health, said in an interview. “Other studies have talked about an increase in mortality, and we were thinking there’d be a little increase like 10% – nothing like 48%.”

According to the Johns Hopkins University of Medicine tracker, nearly 6 million people in the United States had been diagnosed with COVID-19 as of Aug. 30. The number of deaths had surpassed 183,000.

The authors of the new review launched their project to better understand the link between obesity and COVID-19 “all the way from being diagnosed to death,” Dr. Popkin said, adding that the meta-analysis is the largest of its kind to examine the link.

Dr. Popkin and colleagues analyzed 75 studies during January to June 2020 that tracked 399,461 patients (55% of whom were male) diagnosed with COVID-19. They found that 18 of 20 studies linked obesity with a 46% higher risk of diagnosis, but Dr. Popkin cautioned that this may be misleading. “I suspect it’s because they’re sicker and getting tested more for COVID,” he said. “I don’t think obesity enhances your likelihood of getting COVID. We don’t have a biological rationale for that.”

The researchers examined 19 studies that explored a link between obesity and hospitalization; all 19 found a higher risk of hospitalization in patients with obesity (pooled OR, 2.13). Twenty-one of 22 studies that looked at ICU admissions discovered a higher risk for patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.74). And 27 of 35 studies that examined COVID-19 mortality found a higher death rate in patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.48).

The review also looked at 14 studies that examined links between obesity and administration of invasive mechanical ventilation. All the studies found a higher risk for patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.38-1.99; P < .0001).

Could socioeconomic factors explain the difference in risk for people with obesity? It’s not clear. According to Dr. Popkin, most of the studies don’t examine factors such as income. While he believes physical factors are the key to the higher risk, he said “there’s clearly a social side to this.”

On the biological front, it appears that “the immune system is much weaker if you’re obese,” he said, and excess weight may worsen the course of a respiratory disease such as COVID-19 because of lung disorders such as sleep apnea.

In addition to highlighting inflammation and a weakened immune system, the review offers multiple explanations for why patients with obesity face worse outcomes in COVID-19. It may be more difficult for medical professionals to care for them in the hospital because of their weight, the authors wrote, and “obesity may also impair therapeutic treatments during COVID-19 infections.” The authors noted that ACE inhibitors may worsen COVID-19 in patients with type 2 diabetes.

The researchers noted that “potentially the vaccines developed to address COVID-19 will be less effective for individuals with obesity due to a weakened immune response.” They pointed to research that suggests T-cell responses are weaker and antibody titers wane at a faster rate in people with obesity who are vaccinated against influenza.

Pulmonologist Joshua L. Denson, MD, MS, of Tulane University, New Orleans, praised the review in an interview, but noted that some of the included studies have wide confidence intervals. One study that links COVID-19 to a sixfold higher mortality rate (OR, 6.29) has a confidence interval of 1.76-22.45.

Dr. Denson said he’s seen about 100 patients with COVID-19, and many are obese and have metabolic syndrome.

Like the authors of the study, he believes higher levels of inflammation play a crucial role in making these patients more vulnerable. “For whatever reason, the virus tends to really like that state. That’s driving these people to get sick,” he said.

Moving forward, Dr. Popkin urged physicians to redouble their efforts to warn patients about the risks of obesity and the importance of healthy eating. He also said COVID-19 vaccine researchers must stratify obese vs. nonobese subjects in clinical trials.

The review was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Carolina Population Center, World Bank, and Saudi Health Council. The review authors report no relevant disclosures. Dr. Denson reports no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Popkin BM et al. Obes Rev. 2020 Aug 26. doi: 10.1111/obr.13128.

A new analysis of existing research confirms a stark link between excess weight and COVID-19:

Obese patients faced the greatest bump in risk on the hospitalization front, with their odds of being admitted listed as 113% higher. The odds of diagnosis, ICU admission, and death were 46% higher (odds ratio [OR], 1.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.30-1.65; P < .0001); 74% higher (OR, 1.74, CI, 1.46-2.08, P < .0001); 48% (OR, 1.48, CI, 1.22–1.80, P < .001, all pooled analyses and 95% CI), respectively. All differences were highly significantly different, investigators reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis published online Aug. 26 in Obesity Reviews.

“Essentially, these are pretty scary statistics,” nutrition researcher and study lead author Barry M. Popkin, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Public Health, said in an interview. “Other studies have talked about an increase in mortality, and we were thinking there’d be a little increase like 10% – nothing like 48%.”

According to the Johns Hopkins University of Medicine tracker, nearly 6 million people in the United States had been diagnosed with COVID-19 as of Aug. 30. The number of deaths had surpassed 183,000.

The authors of the new review launched their project to better understand the link between obesity and COVID-19 “all the way from being diagnosed to death,” Dr. Popkin said, adding that the meta-analysis is the largest of its kind to examine the link.

Dr. Popkin and colleagues analyzed 75 studies during January to June 2020 that tracked 399,461 patients (55% of whom were male) diagnosed with COVID-19. They found that 18 of 20 studies linked obesity with a 46% higher risk of diagnosis, but Dr. Popkin cautioned that this may be misleading. “I suspect it’s because they’re sicker and getting tested more for COVID,” he said. “I don’t think obesity enhances your likelihood of getting COVID. We don’t have a biological rationale for that.”

The researchers examined 19 studies that explored a link between obesity and hospitalization; all 19 found a higher risk of hospitalization in patients with obesity (pooled OR, 2.13). Twenty-one of 22 studies that looked at ICU admissions discovered a higher risk for patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.74). And 27 of 35 studies that examined COVID-19 mortality found a higher death rate in patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.48).

The review also looked at 14 studies that examined links between obesity and administration of invasive mechanical ventilation. All the studies found a higher risk for patients with obesity (pooled OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.38-1.99; P < .0001).

Could socioeconomic factors explain the difference in risk for people with obesity? It’s not clear. According to Dr. Popkin, most of the studies don’t examine factors such as income. While he believes physical factors are the key to the higher risk, he said “there’s clearly a social side to this.”

On the biological front, it appears that “the immune system is much weaker if you’re obese,” he said, and excess weight may worsen the course of a respiratory disease such as COVID-19 because of lung disorders such as sleep apnea.

In addition to highlighting inflammation and a weakened immune system, the review offers multiple explanations for why patients with obesity face worse outcomes in COVID-19. It may be more difficult for medical professionals to care for them in the hospital because of their weight, the authors wrote, and “obesity may also impair therapeutic treatments during COVID-19 infections.” The authors noted that ACE inhibitors may worsen COVID-19 in patients with type 2 diabetes.

The researchers noted that “potentially the vaccines developed to address COVID-19 will be less effective for individuals with obesity due to a weakened immune response.” They pointed to research that suggests T-cell responses are weaker and antibody titers wane at a faster rate in people with obesity who are vaccinated against influenza.

Pulmonologist Joshua L. Denson, MD, MS, of Tulane University, New Orleans, praised the review in an interview, but noted that some of the included studies have wide confidence intervals. One study that links COVID-19 to a sixfold higher mortality rate (OR, 6.29) has a confidence interval of 1.76-22.45.

Dr. Denson said he’s seen about 100 patients with COVID-19, and many are obese and have metabolic syndrome.