User login

COVID-19: Can doctors refuse to see unvaccinated patients?

In June, Gerald Bock, MD, a dermatologist in central California, instituted a new office policy: He would not be seeing any more patients who remain unvaccinated against COVID-19 in his practice.

“[It is] the height of self-centered and irresponsible behavior,” he told me. “People who come in unvaccinated, when vaccination is widely available, are stating that their personal preferences are more important than their health, and are more important than any risk that they may expose their friends and family to, and also to any risk they might present to my staff and me. We have gone to considerable effort and expense to diminish any risk that visiting our office might entail. I see no reason why we should tolerate this.”

Other doctors appear to be following in his footsteps. There is no question that physicians have the right to choose their patients, just as patients are free to choose their doctors, but That is a complicated question without a clear answer. In a statement on whether physicians can decline unvaccinated patients, the American Medical Association continues to maintain that “in general” a physician may not “ethically turn a patient away based solely on the individual’s infectious disease status,” but does concede that “the decision to accept or decline a patient must balance the urgency of the individual patient’s need; the risk the patient may pose to other patients in the physician’s practice; and the need for the physician and staff, to be available to provide care in the future.”

Medical ethics experts have offered varying opinions. Daniel Wikler, PhD, professor of ethics and population health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post that “ignorance or other personal failing” should not be factors in the evaluation of patients for health care. He argues that “doctors and hospitals are not in the blame and punishment business. Nor should they be. That doctors treat sinners and responsible citizens alike is a noble tradition.”

Timothy Hoff, professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston, maintains that, in nonemergency situations, physicians are legally able to refuse patients for a variety of reasons, provided they are not doing so because of some aspect of the patient’s race, gender, sexuality, or religion. However, in the same Northeastern University news release,Robert Baginski, MD, the director of interdisciplinary affairs for the department of medical sciences at Northeastern, cautions that it is vital for health authorities to continue urging the public to get vaccinated, but not at the expense of care.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the head of the division of medical ethics at New York University, said in a Medscape commentary, that the decision to refuse to see patients who can vaccinate, but choose not to, is justifiable. “If you’re trying to protect yourself, your staff, or other patients, I think you do have the right to not take on somebody who won’t vaccinate,” he writes. “This is somewhat similar to when pediatricians do not accept a family if they won’t give their kids the state-required shots to go to school. That’s been happening for many years now.

“I also think it is morally justified if they won’t take your advice,” he continues. “If they won’t follow what you think is the best healthcare for them [such as getting vaccinated], there’s not much point in building that relationship.”

The situation is different in ED and hospital settings, however. “It’s a little harder to use unvaccinated status when someone really is at death’s door,” Dr. Caplan pointed out. “When someone comes in very sick, or whatever the reason, I think we have to take care of them ethically, and legally we’re bound to get them stable in the emergency room. I do think different rules apply there.”

In the end, every private practitioner will have to make his or her own decision on this question. Dr. Bock feels he made the right one. “Since instituting the policy, we have written 55 refund checks for people who had paid for a series of cosmetic procedures. We have no idea how many people were deterred from making appointments. We’ve had several negative online reviews and one woman who wrote a letter to the Medical Board of California complaining that we were discriminating against her,” he said. He added, however, that “we’ve also had several patients who commented favorably about the policy. I have no regrets about instituting the policy, and would do it again.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In June, Gerald Bock, MD, a dermatologist in central California, instituted a new office policy: He would not be seeing any more patients who remain unvaccinated against COVID-19 in his practice.

“[It is] the height of self-centered and irresponsible behavior,” he told me. “People who come in unvaccinated, when vaccination is widely available, are stating that their personal preferences are more important than their health, and are more important than any risk that they may expose their friends and family to, and also to any risk they might present to my staff and me. We have gone to considerable effort and expense to diminish any risk that visiting our office might entail. I see no reason why we should tolerate this.”

Other doctors appear to be following in his footsteps. There is no question that physicians have the right to choose their patients, just as patients are free to choose their doctors, but That is a complicated question without a clear answer. In a statement on whether physicians can decline unvaccinated patients, the American Medical Association continues to maintain that “in general” a physician may not “ethically turn a patient away based solely on the individual’s infectious disease status,” but does concede that “the decision to accept or decline a patient must balance the urgency of the individual patient’s need; the risk the patient may pose to other patients in the physician’s practice; and the need for the physician and staff, to be available to provide care in the future.”

Medical ethics experts have offered varying opinions. Daniel Wikler, PhD, professor of ethics and population health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post that “ignorance or other personal failing” should not be factors in the evaluation of patients for health care. He argues that “doctors and hospitals are not in the blame and punishment business. Nor should they be. That doctors treat sinners and responsible citizens alike is a noble tradition.”

Timothy Hoff, professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston, maintains that, in nonemergency situations, physicians are legally able to refuse patients for a variety of reasons, provided they are not doing so because of some aspect of the patient’s race, gender, sexuality, or religion. However, in the same Northeastern University news release,Robert Baginski, MD, the director of interdisciplinary affairs for the department of medical sciences at Northeastern, cautions that it is vital for health authorities to continue urging the public to get vaccinated, but not at the expense of care.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the head of the division of medical ethics at New York University, said in a Medscape commentary, that the decision to refuse to see patients who can vaccinate, but choose not to, is justifiable. “If you’re trying to protect yourself, your staff, or other patients, I think you do have the right to not take on somebody who won’t vaccinate,” he writes. “This is somewhat similar to when pediatricians do not accept a family if they won’t give their kids the state-required shots to go to school. That’s been happening for many years now.

“I also think it is morally justified if they won’t take your advice,” he continues. “If they won’t follow what you think is the best healthcare for them [such as getting vaccinated], there’s not much point in building that relationship.”

The situation is different in ED and hospital settings, however. “It’s a little harder to use unvaccinated status when someone really is at death’s door,” Dr. Caplan pointed out. “When someone comes in very sick, or whatever the reason, I think we have to take care of them ethically, and legally we’re bound to get them stable in the emergency room. I do think different rules apply there.”

In the end, every private practitioner will have to make his or her own decision on this question. Dr. Bock feels he made the right one. “Since instituting the policy, we have written 55 refund checks for people who had paid for a series of cosmetic procedures. We have no idea how many people were deterred from making appointments. We’ve had several negative online reviews and one woman who wrote a letter to the Medical Board of California complaining that we were discriminating against her,” he said. He added, however, that “we’ve also had several patients who commented favorably about the policy. I have no regrets about instituting the policy, and would do it again.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In June, Gerald Bock, MD, a dermatologist in central California, instituted a new office policy: He would not be seeing any more patients who remain unvaccinated against COVID-19 in his practice.

“[It is] the height of self-centered and irresponsible behavior,” he told me. “People who come in unvaccinated, when vaccination is widely available, are stating that their personal preferences are more important than their health, and are more important than any risk that they may expose their friends and family to, and also to any risk they might present to my staff and me. We have gone to considerable effort and expense to diminish any risk that visiting our office might entail. I see no reason why we should tolerate this.”

Other doctors appear to be following in his footsteps. There is no question that physicians have the right to choose their patients, just as patients are free to choose their doctors, but That is a complicated question without a clear answer. In a statement on whether physicians can decline unvaccinated patients, the American Medical Association continues to maintain that “in general” a physician may not “ethically turn a patient away based solely on the individual’s infectious disease status,” but does concede that “the decision to accept or decline a patient must balance the urgency of the individual patient’s need; the risk the patient may pose to other patients in the physician’s practice; and the need for the physician and staff, to be available to provide care in the future.”

Medical ethics experts have offered varying opinions. Daniel Wikler, PhD, professor of ethics and population health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post that “ignorance or other personal failing” should not be factors in the evaluation of patients for health care. He argues that “doctors and hospitals are not in the blame and punishment business. Nor should they be. That doctors treat sinners and responsible citizens alike is a noble tradition.”

Timothy Hoff, professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston, maintains that, in nonemergency situations, physicians are legally able to refuse patients for a variety of reasons, provided they are not doing so because of some aspect of the patient’s race, gender, sexuality, or religion. However, in the same Northeastern University news release,Robert Baginski, MD, the director of interdisciplinary affairs for the department of medical sciences at Northeastern, cautions that it is vital for health authorities to continue urging the public to get vaccinated, but not at the expense of care.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the head of the division of medical ethics at New York University, said in a Medscape commentary, that the decision to refuse to see patients who can vaccinate, but choose not to, is justifiable. “If you’re trying to protect yourself, your staff, or other patients, I think you do have the right to not take on somebody who won’t vaccinate,” he writes. “This is somewhat similar to when pediatricians do not accept a family if they won’t give their kids the state-required shots to go to school. That’s been happening for many years now.

“I also think it is morally justified if they won’t take your advice,” he continues. “If they won’t follow what you think is the best healthcare for them [such as getting vaccinated], there’s not much point in building that relationship.”

The situation is different in ED and hospital settings, however. “It’s a little harder to use unvaccinated status when someone really is at death’s door,” Dr. Caplan pointed out. “When someone comes in very sick, or whatever the reason, I think we have to take care of them ethically, and legally we’re bound to get them stable in the emergency room. I do think different rules apply there.”

In the end, every private practitioner will have to make his or her own decision on this question. Dr. Bock feels he made the right one. “Since instituting the policy, we have written 55 refund checks for people who had paid for a series of cosmetic procedures. We have no idea how many people were deterred from making appointments. We’ve had several negative online reviews and one woman who wrote a letter to the Medical Board of California complaining that we were discriminating against her,” he said. He added, however, that “we’ve also had several patients who commented favorably about the policy. I have no regrets about instituting the policy, and would do it again.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Call them by their names in your office

Given that approximately 9.5% of youth aged 13-17 in the United States identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ),1 it is likely that a general pediatrician or pediatric subspecialist is going to encounter at least one LGBTQ patient during the course of the average workweek. By having an easy way to identify these patients and store this data in a user-friendly manner, you can ensure that your practice is LGBTQ friendly and an affirming environment for all sexual- and gender-minority youth.

One way to do this is to look over any paper or electronic forms your practice uses and make sure that they provide patients and families a range of options to identify themselves. For example, you could provide more options for gender, other than male or female, including a nonbinary or “other” (with a free text line) option. This allows your patients to give you an accurate description of what their affirmed gender is. Instead of having a space for mother’s name and father’s name, you could list these fields as “parent/guardian #1” and “parent/guardian #2.” These labels allow for more inclusivity and to reflect the diverse makeup of modern families. Providing a space for a patient to put the name and pronouns that they use allows your staff to make sure that you are calling a patient by the correct name and using the correct pronouns.

Within your EMR, there may be editable fields that allow for you or your staff to list the patient’s affirmed name and pronouns. Making this small change allows any staff member who accesses the chart to have that information displayed correctly for them and reduces the chances of staff misgendering or dead-naming a patient. Underscoring the importance of this, Sequeira et al. found that in a sample of youth from a gender clinic, only 9% of those adolescents reported that they were asked their name/pronouns outside of the gender clinic.2 If those fields are not there, you may check with your IT staff or your EMR vendor to see if these fields may be added in. However, staff needs to make sure that they check with the child/adolescent first to discern with whom the patient has discussed their gender identity. If you were to put a patient’s affirmed name into the chart and then call the patient by that name in front of the parent/guardian, the parent/guardian may look at you quizzically about why you are calling their child by that name. This could then cause an uncomfortable conversation in the exam room or result in harm to the patient after the visit.

It is not just good clinical practice to ensure that you use a patient’s affirmed name and pronouns. Russell et al. looked at the relationship between depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation and whether an adolescent’s name/pronouns were used in the context of their home, school, work, and/or friend group. They found that use of an adolescent’s affirmed name in at least one of these contexts was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms and a 29% decrease in suicidal ideation.3 Therefore, the use of an adolescent’s affirmed name and pronouns in your office contributes to the overall mental well-being of your patients.

Fortunately, there are many guides to help you and your practice be successful at implementing some of these changes. The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Health Access Project put together its “Community Standards of Practice for the Provision of Quality Health Care Services to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Clients” to aid practices in developing environments that are LGBTQ affirming. The National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center, a part of the Fenway Institute, has a series of learning modules that you and your staff can view for interactive training and tips for best practices. These resources offer pediatricians and their practices free resources to improve their policies and procedures. By instituting these small changes, you can ensure that your practice continues to be an affirming environment for your LGBTQ children and adolescents.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

References

1. Conran KJ. LGBT youth population in the United States, UCLA School of Law, Williams Institute, 2020 Sep.

2. Sequeira GM et al. Affirming transgender youths’ names and pronouns in the electronic medical record. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):501-3.

3. Russell ST et al. Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(4):503-5.

Given that approximately 9.5% of youth aged 13-17 in the United States identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ),1 it is likely that a general pediatrician or pediatric subspecialist is going to encounter at least one LGBTQ patient during the course of the average workweek. By having an easy way to identify these patients and store this data in a user-friendly manner, you can ensure that your practice is LGBTQ friendly and an affirming environment for all sexual- and gender-minority youth.

One way to do this is to look over any paper or electronic forms your practice uses and make sure that they provide patients and families a range of options to identify themselves. For example, you could provide more options for gender, other than male or female, including a nonbinary or “other” (with a free text line) option. This allows your patients to give you an accurate description of what their affirmed gender is. Instead of having a space for mother’s name and father’s name, you could list these fields as “parent/guardian #1” and “parent/guardian #2.” These labels allow for more inclusivity and to reflect the diverse makeup of modern families. Providing a space for a patient to put the name and pronouns that they use allows your staff to make sure that you are calling a patient by the correct name and using the correct pronouns.

Within your EMR, there may be editable fields that allow for you or your staff to list the patient’s affirmed name and pronouns. Making this small change allows any staff member who accesses the chart to have that information displayed correctly for them and reduces the chances of staff misgendering or dead-naming a patient. Underscoring the importance of this, Sequeira et al. found that in a sample of youth from a gender clinic, only 9% of those adolescents reported that they were asked their name/pronouns outside of the gender clinic.2 If those fields are not there, you may check with your IT staff or your EMR vendor to see if these fields may be added in. However, staff needs to make sure that they check with the child/adolescent first to discern with whom the patient has discussed their gender identity. If you were to put a patient’s affirmed name into the chart and then call the patient by that name in front of the parent/guardian, the parent/guardian may look at you quizzically about why you are calling their child by that name. This could then cause an uncomfortable conversation in the exam room or result in harm to the patient after the visit.

It is not just good clinical practice to ensure that you use a patient’s affirmed name and pronouns. Russell et al. looked at the relationship between depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation and whether an adolescent’s name/pronouns were used in the context of their home, school, work, and/or friend group. They found that use of an adolescent’s affirmed name in at least one of these contexts was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms and a 29% decrease in suicidal ideation.3 Therefore, the use of an adolescent’s affirmed name and pronouns in your office contributes to the overall mental well-being of your patients.

Fortunately, there are many guides to help you and your practice be successful at implementing some of these changes. The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Health Access Project put together its “Community Standards of Practice for the Provision of Quality Health Care Services to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Clients” to aid practices in developing environments that are LGBTQ affirming. The National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center, a part of the Fenway Institute, has a series of learning modules that you and your staff can view for interactive training and tips for best practices. These resources offer pediatricians and their practices free resources to improve their policies and procedures. By instituting these small changes, you can ensure that your practice continues to be an affirming environment for your LGBTQ children and adolescents.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

References

1. Conran KJ. LGBT youth population in the United States, UCLA School of Law, Williams Institute, 2020 Sep.

2. Sequeira GM et al. Affirming transgender youths’ names and pronouns in the electronic medical record. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):501-3.

3. Russell ST et al. Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(4):503-5.

Given that approximately 9.5% of youth aged 13-17 in the United States identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ),1 it is likely that a general pediatrician or pediatric subspecialist is going to encounter at least one LGBTQ patient during the course of the average workweek. By having an easy way to identify these patients and store this data in a user-friendly manner, you can ensure that your practice is LGBTQ friendly and an affirming environment for all sexual- and gender-minority youth.

One way to do this is to look over any paper or electronic forms your practice uses and make sure that they provide patients and families a range of options to identify themselves. For example, you could provide more options for gender, other than male or female, including a nonbinary or “other” (with a free text line) option. This allows your patients to give you an accurate description of what their affirmed gender is. Instead of having a space for mother’s name and father’s name, you could list these fields as “parent/guardian #1” and “parent/guardian #2.” These labels allow for more inclusivity and to reflect the diverse makeup of modern families. Providing a space for a patient to put the name and pronouns that they use allows your staff to make sure that you are calling a patient by the correct name and using the correct pronouns.

Within your EMR, there may be editable fields that allow for you or your staff to list the patient’s affirmed name and pronouns. Making this small change allows any staff member who accesses the chart to have that information displayed correctly for them and reduces the chances of staff misgendering or dead-naming a patient. Underscoring the importance of this, Sequeira et al. found that in a sample of youth from a gender clinic, only 9% of those adolescents reported that they were asked their name/pronouns outside of the gender clinic.2 If those fields are not there, you may check with your IT staff or your EMR vendor to see if these fields may be added in. However, staff needs to make sure that they check with the child/adolescent first to discern with whom the patient has discussed their gender identity. If you were to put a patient’s affirmed name into the chart and then call the patient by that name in front of the parent/guardian, the parent/guardian may look at you quizzically about why you are calling their child by that name. This could then cause an uncomfortable conversation in the exam room or result in harm to the patient after the visit.

It is not just good clinical practice to ensure that you use a patient’s affirmed name and pronouns. Russell et al. looked at the relationship between depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation and whether an adolescent’s name/pronouns were used in the context of their home, school, work, and/or friend group. They found that use of an adolescent’s affirmed name in at least one of these contexts was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms and a 29% decrease in suicidal ideation.3 Therefore, the use of an adolescent’s affirmed name and pronouns in your office contributes to the overall mental well-being of your patients.

Fortunately, there are many guides to help you and your practice be successful at implementing some of these changes. The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Health Access Project put together its “Community Standards of Practice for the Provision of Quality Health Care Services to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Clients” to aid practices in developing environments that are LGBTQ affirming. The National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center, a part of the Fenway Institute, has a series of learning modules that you and your staff can view for interactive training and tips for best practices. These resources offer pediatricians and their practices free resources to improve their policies and procedures. By instituting these small changes, you can ensure that your practice continues to be an affirming environment for your LGBTQ children and adolescents.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

References

1. Conran KJ. LGBT youth population in the United States, UCLA School of Law, Williams Institute, 2020 Sep.

2. Sequeira GM et al. Affirming transgender youths’ names and pronouns in the electronic medical record. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):501-3.

3. Russell ST et al. Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(4):503-5.

You’ve been uneasy about the mother’s boyfriend: This may be why

The first patient of the afternoon is a 4-month-old in for his health maintenance visit. You’ve known his 20-year-old mother since she was a toddler. This infant has a 2-year-old sister. Also in the exam room is a young man you don’t recognize whom the mother introduces as Jason, her new boyfriend. He never makes eye contact and despite your best efforts you can’t get him to engage.

At the child’s next visit you are relieved to see the 6-month-old is alive and well and learn that your former patient and her two children have moved back in with her parents and Jason is no longer in the picture.

You don’t have to have been doing pediatrics very long to have learned that a “family” that includes an infant and a young adult male who is probably not the father is an environment in which the infant’s health and well-being is at significant risk. It is a situation in which child abuse even to the point of infanticide should be waving a red flag in your face.

Infanticide occurs in many animal species including our own. As abhorrent we may find the act, it occurs often enough to be, if not normal, at least not unexpected in certain circumstances. Theories abound as to what advantage the act of infanticide might convey to the success of a species. However, little if anything is known about any possible mechanisms that would allow it to occur.

Recently, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University discovered a specific set of neurons in the mouse brain that controls aggressive behavior toward infants (Biological triggers for infant abuse, by Juan Siliezar, The Harvard Gazette, Sept 27, 2021). This same set of neurons also appears to trigger avoidance and neglect behaviors as well.

Research in other animal species has found that these antiparental behaviors occur in both virgins and sexually mature males who are strangers to the group. Interestingly, the behaviors switch off once individuals have their own offspring or have had the opportunity to familiarize themselves with infants. Not surprisingly, other studies have found that in some species environmental stress such as food shortage or threats of predation have triggered females to attack or ignore their offspring.

I think it is safe to assume a similar collection of neurons controlling aggressive behavior also exists in humans. One can imagine some well-read defense attorney dredging up this study and claiming that because his client had not yet fathered a child of his own that it was his nervous system’s normal response that made him toss his girlfriend’s baby against the wall.

The lead author of the study intends to study this collection of neurons in more depth to discover more about the process. It is conceivable that with more information her initial findings may help in the development of treatment and specific prevention strategies. Until that happens, we must rely on our intuition and keep our antennae tuned and alert for high-risk scenarios like the one I described at the opening of this letter.

We are left with leaning heavily on our community social work networks to keep close tabs on these high-risk families, offering both financial and emotional support. Parenting classes may be helpful, but some of this research leads me to suspect that immersing these young parents-to-be in hands-on child care situations might provide the best protection we can offer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

The first patient of the afternoon is a 4-month-old in for his health maintenance visit. You’ve known his 20-year-old mother since she was a toddler. This infant has a 2-year-old sister. Also in the exam room is a young man you don’t recognize whom the mother introduces as Jason, her new boyfriend. He never makes eye contact and despite your best efforts you can’t get him to engage.

At the child’s next visit you are relieved to see the 6-month-old is alive and well and learn that your former patient and her two children have moved back in with her parents and Jason is no longer in the picture.

You don’t have to have been doing pediatrics very long to have learned that a “family” that includes an infant and a young adult male who is probably not the father is an environment in which the infant’s health and well-being is at significant risk. It is a situation in which child abuse even to the point of infanticide should be waving a red flag in your face.

Infanticide occurs in many animal species including our own. As abhorrent we may find the act, it occurs often enough to be, if not normal, at least not unexpected in certain circumstances. Theories abound as to what advantage the act of infanticide might convey to the success of a species. However, little if anything is known about any possible mechanisms that would allow it to occur.

Recently, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University discovered a specific set of neurons in the mouse brain that controls aggressive behavior toward infants (Biological triggers for infant abuse, by Juan Siliezar, The Harvard Gazette, Sept 27, 2021). This same set of neurons also appears to trigger avoidance and neglect behaviors as well.

Research in other animal species has found that these antiparental behaviors occur in both virgins and sexually mature males who are strangers to the group. Interestingly, the behaviors switch off once individuals have their own offspring or have had the opportunity to familiarize themselves with infants. Not surprisingly, other studies have found that in some species environmental stress such as food shortage or threats of predation have triggered females to attack or ignore their offspring.

I think it is safe to assume a similar collection of neurons controlling aggressive behavior also exists in humans. One can imagine some well-read defense attorney dredging up this study and claiming that because his client had not yet fathered a child of his own that it was his nervous system’s normal response that made him toss his girlfriend’s baby against the wall.

The lead author of the study intends to study this collection of neurons in more depth to discover more about the process. It is conceivable that with more information her initial findings may help in the development of treatment and specific prevention strategies. Until that happens, we must rely on our intuition and keep our antennae tuned and alert for high-risk scenarios like the one I described at the opening of this letter.

We are left with leaning heavily on our community social work networks to keep close tabs on these high-risk families, offering both financial and emotional support. Parenting classes may be helpful, but some of this research leads me to suspect that immersing these young parents-to-be in hands-on child care situations might provide the best protection we can offer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

The first patient of the afternoon is a 4-month-old in for his health maintenance visit. You’ve known his 20-year-old mother since she was a toddler. This infant has a 2-year-old sister. Also in the exam room is a young man you don’t recognize whom the mother introduces as Jason, her new boyfriend. He never makes eye contact and despite your best efforts you can’t get him to engage.

At the child’s next visit you are relieved to see the 6-month-old is alive and well and learn that your former patient and her two children have moved back in with her parents and Jason is no longer in the picture.

You don’t have to have been doing pediatrics very long to have learned that a “family” that includes an infant and a young adult male who is probably not the father is an environment in which the infant’s health and well-being is at significant risk. It is a situation in which child abuse even to the point of infanticide should be waving a red flag in your face.

Infanticide occurs in many animal species including our own. As abhorrent we may find the act, it occurs often enough to be, if not normal, at least not unexpected in certain circumstances. Theories abound as to what advantage the act of infanticide might convey to the success of a species. However, little if anything is known about any possible mechanisms that would allow it to occur.

Recently, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University discovered a specific set of neurons in the mouse brain that controls aggressive behavior toward infants (Biological triggers for infant abuse, by Juan Siliezar, The Harvard Gazette, Sept 27, 2021). This same set of neurons also appears to trigger avoidance and neglect behaviors as well.

Research in other animal species has found that these antiparental behaviors occur in both virgins and sexually mature males who are strangers to the group. Interestingly, the behaviors switch off once individuals have their own offspring or have had the opportunity to familiarize themselves with infants. Not surprisingly, other studies have found that in some species environmental stress such as food shortage or threats of predation have triggered females to attack or ignore their offspring.

I think it is safe to assume a similar collection of neurons controlling aggressive behavior also exists in humans. One can imagine some well-read defense attorney dredging up this study and claiming that because his client had not yet fathered a child of his own that it was his nervous system’s normal response that made him toss his girlfriend’s baby against the wall.

The lead author of the study intends to study this collection of neurons in more depth to discover more about the process. It is conceivable that with more information her initial findings may help in the development of treatment and specific prevention strategies. Until that happens, we must rely on our intuition and keep our antennae tuned and alert for high-risk scenarios like the one I described at the opening of this letter.

We are left with leaning heavily on our community social work networks to keep close tabs on these high-risk families, offering both financial and emotional support. Parenting classes may be helpful, but some of this research leads me to suspect that immersing these young parents-to-be in hands-on child care situations might provide the best protection we can offer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Underrepresented Minority Students Applying to Dermatology Residency in the COVID-19 Era: Challenges and Considerations

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8

In addition, we encourage continuation of the proposed coordinated interview invite release from the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which was implemented in the 2020-2021 cycle. In light of the recent AAMC letter9 on the maldistribution of interview invitations to highest-tier applicants, coordination of interview release dates and other similar initiatives to prevent programs from offering more invites than their available slots and improve transparency about interview days are needed. Furthermore, continuing to offer optional virtual interviews for applicants in future cycles could make the process less cost-prohibitive for many URM students.4,5

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residency programs must intentionally guard against falling back to traditional standards of assessment as the only means of student evaluation, especially in this virtual era. It is our responsibility to remove artificial barriers that continue to stall progress in diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging in dermatology.

- Underrepresented in medicine definition. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. table 13. practice specialty, males by race/ethnicity, 2018. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-13-practice-specialty-males-race/ethnicity-2018 1B

- US Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Williams C, Kwan B, Pereira A, et al. A call to improve conditions for conducting holistic review in graduate medical education recruitment. MedEdPublish. 2019;8:6. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000076.1

- Holistic principles in resident selection: an introduction. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-08/aa-member-capacity-building-holistic-review-transcript-activities-GME-081420.pdf

- Luke J, Cornelius L, Lim H. Dermatology resident selection: shifting toward holistic review? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;84:1208-1209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.025

- Open letter on residency interviews from Alison Whelan, MD, AAMC Chief Medical Education Officer. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/50291/download

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8

In addition, we encourage continuation of the proposed coordinated interview invite release from the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which was implemented in the 2020-2021 cycle. In light of the recent AAMC letter9 on the maldistribution of interview invitations to highest-tier applicants, coordination of interview release dates and other similar initiatives to prevent programs from offering more invites than their available slots and improve transparency about interview days are needed. Furthermore, continuing to offer optional virtual interviews for applicants in future cycles could make the process less cost-prohibitive for many URM students.4,5

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residency programs must intentionally guard against falling back to traditional standards of assessment as the only means of student evaluation, especially in this virtual era. It is our responsibility to remove artificial barriers that continue to stall progress in diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging in dermatology.

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8

In addition, we encourage continuation of the proposed coordinated interview invite release from the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which was implemented in the 2020-2021 cycle. In light of the recent AAMC letter9 on the maldistribution of interview invitations to highest-tier applicants, coordination of interview release dates and other similar initiatives to prevent programs from offering more invites than their available slots and improve transparency about interview days are needed. Furthermore, continuing to offer optional virtual interviews for applicants in future cycles could make the process less cost-prohibitive for many URM students.4,5

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residency programs must intentionally guard against falling back to traditional standards of assessment as the only means of student evaluation, especially in this virtual era. It is our responsibility to remove artificial barriers that continue to stall progress in diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging in dermatology.

- Underrepresented in medicine definition. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. table 13. practice specialty, males by race/ethnicity, 2018. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-13-practice-specialty-males-race/ethnicity-2018 1B

- US Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Williams C, Kwan B, Pereira A, et al. A call to improve conditions for conducting holistic review in graduate medical education recruitment. MedEdPublish. 2019;8:6. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000076.1

- Holistic principles in resident selection: an introduction. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-08/aa-member-capacity-building-holistic-review-transcript-activities-GME-081420.pdf

- Luke J, Cornelius L, Lim H. Dermatology resident selection: shifting toward holistic review? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;84:1208-1209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.025

- Open letter on residency interviews from Alison Whelan, MD, AAMC Chief Medical Education Officer. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/50291/download

- Underrepresented in medicine definition. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. table 13. practice specialty, males by race/ethnicity, 2018. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-13-practice-specialty-males-race/ethnicity-2018 1B

- US Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Williams C, Kwan B, Pereira A, et al. A call to improve conditions for conducting holistic review in graduate medical education recruitment. MedEdPublish. 2019;8:6. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000076.1

- Holistic principles in resident selection: an introduction. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-08/aa-member-capacity-building-holistic-review-transcript-activities-GME-081420.pdf

- Luke J, Cornelius L, Lim H. Dermatology resident selection: shifting toward holistic review? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;84:1208-1209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.025

- Open letter on residency interviews from Alison Whelan, MD, AAMC Chief Medical Education Officer. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/50291/download

Practice Points

- Dermatology remains one of the least diverse medical specialties.

- Underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine residency applicants might be negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The implementation of holistic review, diversity and inclusion initiatives, and virtual opportunities might mitigate some of the barriers faced by URM applicants.

Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on respiratory infectious diseases in primary care practice

A secondary consequence of public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 included a concurrent reduction in risk for children to acquire and spread other respiratory viral infectious diseases. In the Rochester, N.Y., area, we had an ongoing prospective study in primary care pediatric practices that afforded an opportunity to assess the effect of the pandemic control measures on all infectious disease illness visits in young children. Specifically, in children aged 6-36 months old, our study was in place when the pandemic began with a primary objective to evaluate the changing epidemiology of acute otitis media (AOM) and nasopharyngeal colonization by potential bacterial respiratory pathogens in community-based primary care pediatric practices. As the public health measures mandated by New York State Department of Health were implemented, we prospectively quantified their effect on physician-diagnosed infectious disease illness visits. The incidence of infectious disease visits by a cohort of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic period March 15, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2020, was compared with the same time frame in the preceding year, 2019.1

Recommendations of the New York State Department of Health for public health, changes in school and day care attendance, and clinical practice during the study time frame

On March 7, 2020, a state of emergency was declared in New York because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All schools were required to close. A mandated order for public use of masks in adults and children more than 2 years of age was enacted. In the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where the two primary care pediatric practices reside, complete lockdown was partially lifted on May 15, 2020, and further lifted on June 26, 2020. Almost all regional school districts opened to at least hybrid learning models for all students starting Sept. 8, 2020. On March 6, 2020, video telehealth and telephone call visits were introduced as routine practice. Well-child visits were limited to those less than 2 years of age, then gradually expanded to all ages by late May 2020. During the “stay at home” phase of the New York State lockdown, day care services were considered an essential business. Day care child density was limited. All children less than 2 years old were required to wear a mask while in the facility. Upon arrival, children with any respiratory symptoms or fever were excluded. For the school year commencing September 2020, almost all regional school districts opened to virtual, hybrid, or in-person learning models. Exclusion occurred similar to that of the day care facilities.

Incidence of respiratory infectious disease illnesses

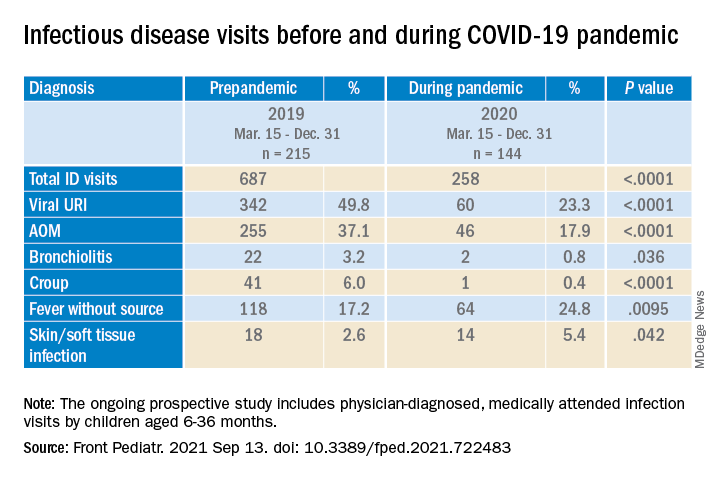

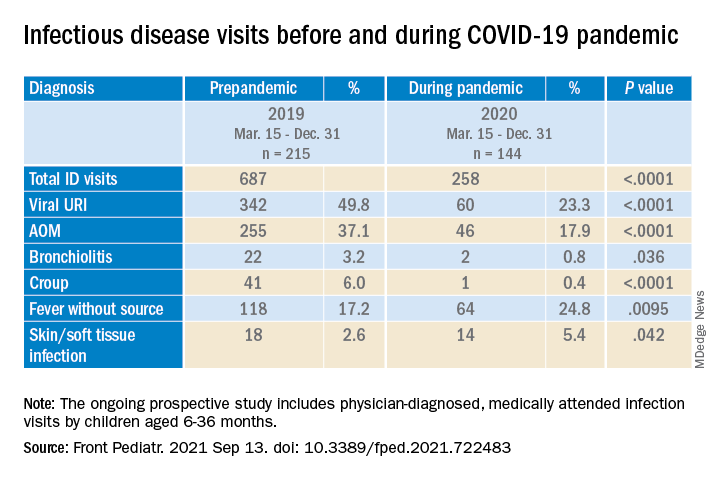

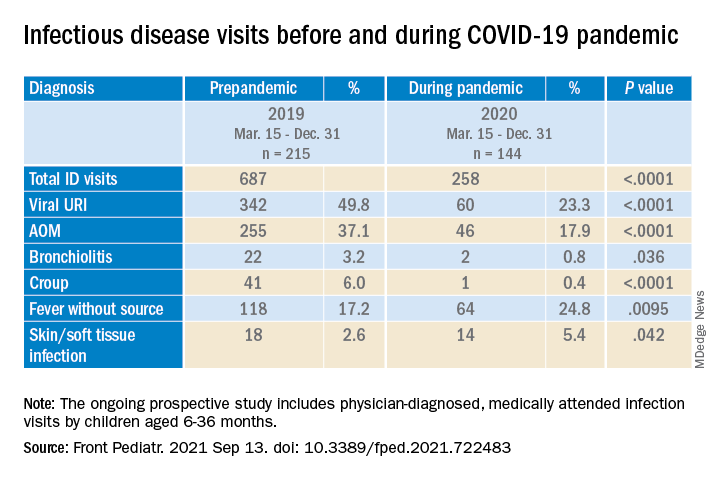

Clinical diagnoses and healthy visits of 144 children from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (beginning of the pandemic) were compared to 215 children during the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates trended up alongside community spread. Pediatric practice positivity rates rose from 1.9% in October 2020 to 19% in December 2020.

The table shows the incidence of significantly different infectious disease illness visits in the two study cohorts.

During the pandemic, 258 infection visits occurred among 144 pandemic cohort children, compared with 687 visits among 215 prepandemic cohort children, a 1.8-fold decrease (P < .0001). The proportion of children with visits for AOM (3.7-fold; P < .0001), bronchiolitis (7.4-fold; P = .036), croup (27.5-fold; P < .0001), and viral upper respiratory infection (3.8-fold; P < .0001) decreased significantly. Fever without a source (1.4-fold decrease; P = .009) and skin/soft tissue infection (2.1-fold decrease; P = .042) represented a higher proportion of visits during the pandemic.

Prescription of antibiotics significantly decreased (P < .001) during the pandemic.

Change in care practices

In the prepandemic period, virtual visits, leading to a diagnosis and treatment and referring children to an urgent care or hospital emergency department during regular office hours were rare. During the pandemic, this changed. Significantly increased use of telemedicine visits (P < .0001) and significantly decreased office and urgent care visits (P < .0001) occurred during the pandemic. Telehealth visits peaked the week of April 12, 2020, at 45% of all pediatric visits. In-person illness visits gradually returned to year-to-year volumes in August-September 2020 with school opening. Early in the pandemic, both pediatric offices limited patient encounters to well-child visits in the first 2 years of life to not miss opportunities for childhood vaccinations. However, some parents were reluctant to bring their children to those visits. There was no significant change in frequency of healthy child visits during the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this was the first study from primary care pediatric practices in the United States to analyze the effect on infectious diseases during the first 9 months of the pandemic, including the 6-month time period after the reopening from the first 3 months of lockdown. One prior study from a primary care network in Massachusetts reported significant decreases in respiratory infectious diseases for children aged 0-17 years during the first months of the pandemic during lockdown.2 A study in Tennessee that included hospital emergency department, urgent care, primary care, and retail health clinics also reported respiratory infection diagnoses as well as antibiotic prescription were reduced in the early months of the pandemic.3

Our study shows an overall reduction in frequency of respiratory illness visits in children 6-36 months old during the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We learned the value of using technology in the form of virtual visits to render care. Perhaps as the pandemic subsides, many of the hand-washing and sanitizing practices will remain in place and lead to less frequent illness in children in the future. However, there may be temporary negative consequences from the “immune debt” that has occurred from a prolonged time span when children were not becoming infected with respiratory pathogens.4 We will see what unfolds in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director at Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Schulz have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;(9)722483:1-8.

2. Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020006460.

3. Katz SE et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(1):62-4.

4. Cohen R et al. Infect. Dis Now. 2021; 51(5)418-23.

A secondary consequence of public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 included a concurrent reduction in risk for children to acquire and spread other respiratory viral infectious diseases. In the Rochester, N.Y., area, we had an ongoing prospective study in primary care pediatric practices that afforded an opportunity to assess the effect of the pandemic control measures on all infectious disease illness visits in young children. Specifically, in children aged 6-36 months old, our study was in place when the pandemic began with a primary objective to evaluate the changing epidemiology of acute otitis media (AOM) and nasopharyngeal colonization by potential bacterial respiratory pathogens in community-based primary care pediatric practices. As the public health measures mandated by New York State Department of Health were implemented, we prospectively quantified their effect on physician-diagnosed infectious disease illness visits. The incidence of infectious disease visits by a cohort of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic period March 15, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2020, was compared with the same time frame in the preceding year, 2019.1

Recommendations of the New York State Department of Health for public health, changes in school and day care attendance, and clinical practice during the study time frame