User login

MDedge conference coverage features onsite reporting of the latest study results and expert perspectives from leading researchers.

Food insecurity drives poor glycemic control

People with diabetes who had a poor-quality diet and food insecurity were significantly more likely to have poor glycemic and cholesterol control than were those with a healthier diet and food security, based on data from a national study of more than 2,000 individuals.

The American Diabetes Association recommends a high-quality diet for people with diabetes (PWD) to achieve treatment goals; however, roughly 18% of PWD in the United States are food insecure and/or have a poor-quality diet, Sarah S. Casagrande, PhD, of DLH Corporation, Silver Spring, Md., and colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the annual scientific sessions of the ADA in New Orleans.

To examine the impact of food insecurity and diet quality on diabetes and lipid management, the researchers reviewed data from 2,075 adults with self-reported diabetes who completed the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys between 2013 and 2018.

Diet quality was divided into quartiles based on the 2015 Healthy Eating Index. Food insecurity was assessed using a standard 10-item questionnaire including questions about running out of food and not being able to afford more, reducing meal sizes, eating less or not at all, and going hungry because of lack of money for food.

The logistic regression analysis controlled for factors including sociodemographics, health care use, smoking, diabetes medications, blood pressure medication use, cholesterol medication use, and body mass index.

Overall, 17.6% of the participants were food insecure and had a low-quality diet, 14.2% were food insecure with a high-quality diet, 33.1% were food secure with a low-quality diet, and 35.2% were food secure with a high-quality diet.

PWD in the food insecure/low-quality diet group were significantly more likely to be younger, non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, and uninsured compared to those in the food secure/high-quality diet group (P < .001 for all).

When the researchers examined glycemic control, they found that PWD in the food insecurity/low-quality diet groups were significantly more likely than were those with food security/high-quality diets to have hemoglobin A1c of at least 7.0% (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85), A1c of at least 8.0% (aOR, 1.79), low HDL cholesterol (aOR, 1.69), and high triglycerides (aOR, 3.26).

PWD with food insecurity but a high-quality diet also were significantly more likely than were those with food security and a high quality diet to have A1c of at least 7.0% (aOR, 1.69), A1c of at least 8.0% (aOR, 1.83), and high triglycerides (aOR, 2.44). PWD with food security but a low-quality diet were significantly more likely than was the food security/high-quality diet group to have A1c of at least 7% (aOR, 1.55).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, reliance on self-reports, and inability to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, the researchers wrote.

However, the results were strengthened by the large, nationally representative sample and the inclusion of multiple clinical outcomes in the patient assessment, they said.

The results suggest that food insecurity had a significant impact on both glycemic control and cholesterol management independent of diet quality, the researchers noted. Based on these findings, health care providers treating PWD may wish to assess their patients’ food security status, and “interventions could address disparities in food security,” they concluded.

Food insecurity a growing problem

“With more communities being pushed into state of war, drought, and famine globally, it is important to track impact of food insecurity and low quality food on common medical conditions like diabetes in our vulnerable communities,” Romesh K. Khardori, MD, professor of medicine: endocrinology, and metabolism at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said in an interview.

Dr. Khardori, who was not involved in the study, said he was not surprised by the current study findings.

“Type of food, amount of food, and quality of food have been stressed in diabetes management for more than 100 years,” he said. “Organizations charged with recommendations, such as the ADA and American Dietetic Association, have regularly updated their recommendations,” he noted. “It was not surprising, therefore, to find food insecurity and low quality tied to poor glycemic control.”

The take-home message for clinicians is to consider the availability and quality of food that their patients are exposed to when evaluating barriers to proper glycemic control, Dr. Khardori emphasized.

However, additional research is needed to explore whether the prescription of a sufficient amount of good quality food would alleviate the adverse impact seen in the current study, he said.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The researchers and Dr. Khardori had no financial conflicts to disclose.

People with diabetes who had a poor-quality diet and food insecurity were significantly more likely to have poor glycemic and cholesterol control than were those with a healthier diet and food security, based on data from a national study of more than 2,000 individuals.

The American Diabetes Association recommends a high-quality diet for people with diabetes (PWD) to achieve treatment goals; however, roughly 18% of PWD in the United States are food insecure and/or have a poor-quality diet, Sarah S. Casagrande, PhD, of DLH Corporation, Silver Spring, Md., and colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the annual scientific sessions of the ADA in New Orleans.

To examine the impact of food insecurity and diet quality on diabetes and lipid management, the researchers reviewed data from 2,075 adults with self-reported diabetes who completed the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys between 2013 and 2018.

Diet quality was divided into quartiles based on the 2015 Healthy Eating Index. Food insecurity was assessed using a standard 10-item questionnaire including questions about running out of food and not being able to afford more, reducing meal sizes, eating less or not at all, and going hungry because of lack of money for food.

The logistic regression analysis controlled for factors including sociodemographics, health care use, smoking, diabetes medications, blood pressure medication use, cholesterol medication use, and body mass index.

Overall, 17.6% of the participants were food insecure and had a low-quality diet, 14.2% were food insecure with a high-quality diet, 33.1% were food secure with a low-quality diet, and 35.2% were food secure with a high-quality diet.

PWD in the food insecure/low-quality diet group were significantly more likely to be younger, non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, and uninsured compared to those in the food secure/high-quality diet group (P < .001 for all).

When the researchers examined glycemic control, they found that PWD in the food insecurity/low-quality diet groups were significantly more likely than were those with food security/high-quality diets to have hemoglobin A1c of at least 7.0% (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85), A1c of at least 8.0% (aOR, 1.79), low HDL cholesterol (aOR, 1.69), and high triglycerides (aOR, 3.26).

PWD with food insecurity but a high-quality diet also were significantly more likely than were those with food security and a high quality diet to have A1c of at least 7.0% (aOR, 1.69), A1c of at least 8.0% (aOR, 1.83), and high triglycerides (aOR, 2.44). PWD with food security but a low-quality diet were significantly more likely than was the food security/high-quality diet group to have A1c of at least 7% (aOR, 1.55).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, reliance on self-reports, and inability to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, the researchers wrote.

However, the results were strengthened by the large, nationally representative sample and the inclusion of multiple clinical outcomes in the patient assessment, they said.

The results suggest that food insecurity had a significant impact on both glycemic control and cholesterol management independent of diet quality, the researchers noted. Based on these findings, health care providers treating PWD may wish to assess their patients’ food security status, and “interventions could address disparities in food security,” they concluded.

Food insecurity a growing problem

“With more communities being pushed into state of war, drought, and famine globally, it is important to track impact of food insecurity and low quality food on common medical conditions like diabetes in our vulnerable communities,” Romesh K. Khardori, MD, professor of medicine: endocrinology, and metabolism at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said in an interview.

Dr. Khardori, who was not involved in the study, said he was not surprised by the current study findings.

“Type of food, amount of food, and quality of food have been stressed in diabetes management for more than 100 years,” he said. “Organizations charged with recommendations, such as the ADA and American Dietetic Association, have regularly updated their recommendations,” he noted. “It was not surprising, therefore, to find food insecurity and low quality tied to poor glycemic control.”

The take-home message for clinicians is to consider the availability and quality of food that their patients are exposed to when evaluating barriers to proper glycemic control, Dr. Khardori emphasized.

However, additional research is needed to explore whether the prescription of a sufficient amount of good quality food would alleviate the adverse impact seen in the current study, he said.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The researchers and Dr. Khardori had no financial conflicts to disclose.

People with diabetes who had a poor-quality diet and food insecurity were significantly more likely to have poor glycemic and cholesterol control than were those with a healthier diet and food security, based on data from a national study of more than 2,000 individuals.

The American Diabetes Association recommends a high-quality diet for people with diabetes (PWD) to achieve treatment goals; however, roughly 18% of PWD in the United States are food insecure and/or have a poor-quality diet, Sarah S. Casagrande, PhD, of DLH Corporation, Silver Spring, Md., and colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the annual scientific sessions of the ADA in New Orleans.

To examine the impact of food insecurity and diet quality on diabetes and lipid management, the researchers reviewed data from 2,075 adults with self-reported diabetes who completed the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys between 2013 and 2018.

Diet quality was divided into quartiles based on the 2015 Healthy Eating Index. Food insecurity was assessed using a standard 10-item questionnaire including questions about running out of food and not being able to afford more, reducing meal sizes, eating less or not at all, and going hungry because of lack of money for food.

The logistic regression analysis controlled for factors including sociodemographics, health care use, smoking, diabetes medications, blood pressure medication use, cholesterol medication use, and body mass index.

Overall, 17.6% of the participants were food insecure and had a low-quality diet, 14.2% were food insecure with a high-quality diet, 33.1% were food secure with a low-quality diet, and 35.2% were food secure with a high-quality diet.

PWD in the food insecure/low-quality diet group were significantly more likely to be younger, non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, and uninsured compared to those in the food secure/high-quality diet group (P < .001 for all).

When the researchers examined glycemic control, they found that PWD in the food insecurity/low-quality diet groups were significantly more likely than were those with food security/high-quality diets to have hemoglobin A1c of at least 7.0% (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85), A1c of at least 8.0% (aOR, 1.79), low HDL cholesterol (aOR, 1.69), and high triglycerides (aOR, 3.26).

PWD with food insecurity but a high-quality diet also were significantly more likely than were those with food security and a high quality diet to have A1c of at least 7.0% (aOR, 1.69), A1c of at least 8.0% (aOR, 1.83), and high triglycerides (aOR, 2.44). PWD with food security but a low-quality diet were significantly more likely than was the food security/high-quality diet group to have A1c of at least 7% (aOR, 1.55).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, reliance on self-reports, and inability to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, the researchers wrote.

However, the results were strengthened by the large, nationally representative sample and the inclusion of multiple clinical outcomes in the patient assessment, they said.

The results suggest that food insecurity had a significant impact on both glycemic control and cholesterol management independent of diet quality, the researchers noted. Based on these findings, health care providers treating PWD may wish to assess their patients’ food security status, and “interventions could address disparities in food security,” they concluded.

Food insecurity a growing problem

“With more communities being pushed into state of war, drought, and famine globally, it is important to track impact of food insecurity and low quality food on common medical conditions like diabetes in our vulnerable communities,” Romesh K. Khardori, MD, professor of medicine: endocrinology, and metabolism at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said in an interview.

Dr. Khardori, who was not involved in the study, said he was not surprised by the current study findings.

“Type of food, amount of food, and quality of food have been stressed in diabetes management for more than 100 years,” he said. “Organizations charged with recommendations, such as the ADA and American Dietetic Association, have regularly updated their recommendations,” he noted. “It was not surprising, therefore, to find food insecurity and low quality tied to poor glycemic control.”

The take-home message for clinicians is to consider the availability and quality of food that their patients are exposed to when evaluating barriers to proper glycemic control, Dr. Khardori emphasized.

However, additional research is needed to explore whether the prescription of a sufficient amount of good quality food would alleviate the adverse impact seen in the current study, he said.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The researchers and Dr. Khardori had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM ADA 2022

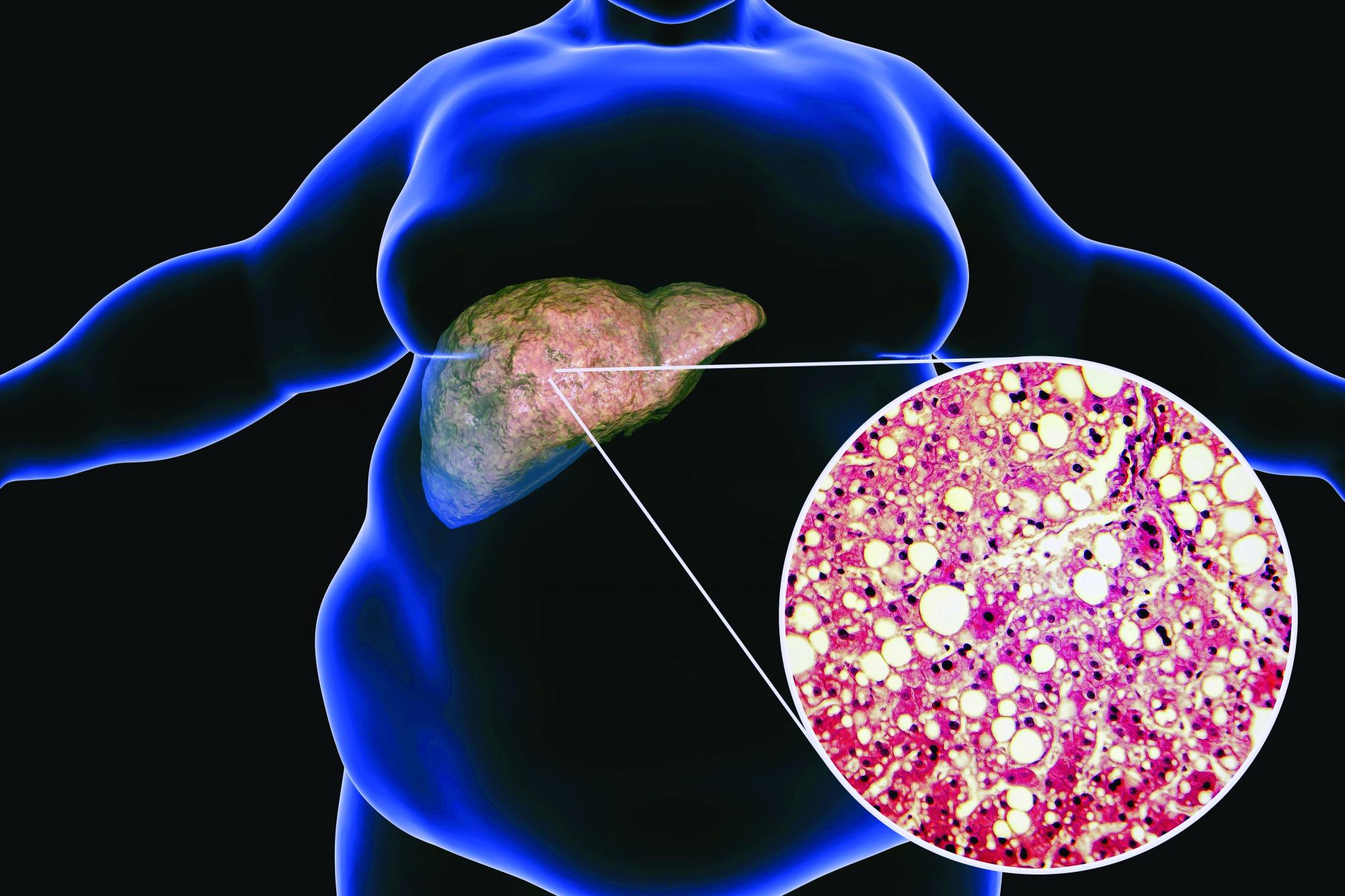

Low-carb, high-fat diet improves A1c, reduces liver fat

LONDON – A low-carbohydrate, high-fat (LCHF) diet reduced the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and despite no calorie restriction, participants with both NAFLD and type 2 diabetes lost 5.8% of their body weight, according to a randomized controlled study.

“Based on these results, the LCHF diet may be recommended to people with NAFLD and type 2 diabetes,” said Camilla Dalby Hansen, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, who presented the data at the International Liver Congress (ILC) 2022.

“Basically, if you have fat in your liver, you will benefit from eating fat,” she said.

The LCHF diet was compared with a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet more typically followed for these conditions. The low-fat diet was also found to reduce the progression of NAFLD, but to a lesser extent than the LCHF diet.

Dr. Dalby Hansen called their study one of the most extensive investigations of the LCHF diet in patients with type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease.

“Combining this [reduction in NAFLD score] with the huge weight loss, the lower HbA1c [blood sugar], the lowering of blood pressure in women, the rise in HDL levels, and reduction in triglycerides – all in all, this diet is very promising,” she said.

Stephen Harrison, MD, visiting professor, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, medical director of Pinnacle Clinical Research and president of Summit Clinical Research, San Antonio, commended Dr. Dalby Hansen on her methodology, which included before-and-after liver biopsies. “It’s a heinous effort to do paired liver biopsies in a lifestyle modification trial. That’s huge.”

“This study tells me that the way we manage patients doesn’t change – it is still lifestyle modification,” said Dr. Harrison, who was not involved with the study. “It’s eat less [rather] than more. It’s exercise and try to lose weight. In the long term, we give patients benefit, and we show that the disease has improved, and we offer something that means they can maintain a healthy life.”

He added that the relatively small and short trial was informative.

“They improved the NAFLD activity score [NAS],” he said. “I don’t know by how much. There was no change in fibrosis, but we wouldn’t expect this at 6 months.”

“It’s provocative work, and it gives us healthy information about how we can help manage our patients from a lifestyle perspective,” he concluded.

‘Do not lose weight. Eat until you are full’

In the study, 110 participants with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, aged 18-78 years, were allocated to the LCHF diet, and 55 were allocated to the low-fat diet for 6 months.

The researchers performed liver biopsies at baseline and 6 months, which were blinded for scoring.

Participants had ongoing dietitian consultations, with follow-up visits at 3 and 6 months. Compliance was reported continuously through an online food diary platform.

The primary endpoint was change in glycemic control as measured by A1c level over 6 months. The secondary endpoints comprised the proportion of participants with changes in the NAS of at least 2 points over 6 months. Both these measures were compared between the two dietary groups.

The two groups were matched at baseline, with a mean age of 55-57 years, 58% were women, 89% with metabolic syndrome, and a mean BMI 34 kg/m2.

In baseline liver disease, F1 level fibrosis was the most common (58%), followed by hepatic steatosis (S1, 47%; S2, 32%), with a median NAS of 3, and 19% had nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

The special thing about these diets was that participants were told to “not lose weight, but eat until you are full,” remarked Dr. Dalby Hansen.

Those on the LCHF diet consumed an average of 61% energy from fat, 13% from carbohydrates, and 23% from protein, compared with the low-fat diet, which comprised an average of 29% energy from fat, 46% from carbohydrates, and 21% from protein.

“It’s a lot of fat and corresponds to a quarter of a liter of olive oil per day,” said Dr. Dalby Hansen. “They really had to change their mindset a lot, because it was difficult for them to start eating all these fats, especially since we’ve all been told for decades that it isn’t good. But we supported them, and they got into it.”

The LCHF diet was primarily comprised of unsaturated fats – for example, avocado, oil, nuts, and seeds – but also included saturated fats, such as cheese, cream, and high-fat dairy products. Participants were free to eat unsaturated and saturated fats, but Dr. Dalby Hansen and her team advised participants that “good” unsaturated fats were preferable.

“Also, this diet contained vegetables but no bread, no potatoes, no rice, and no pasta. It was low in carbohydrates, below 20%,” she added.

Improved glycemic control, reduced liver fat

“We found that the LCHF diet improved diabetes control, it reduced the fat in the liver, and, even though they’re eating as many calories as they were used to until they were full, they lost 5.8% of body weight,” said Dr. Dalby Hansen in reporting the results. Participants in the low-fat group lost only 1.8% of body weight.

However, mean calorie intake dropped in both groups, by –2.2% in the LCHF group and –8.7% in the low-fat group.

“The LCHF diet improved the primary outcome of A1c by 9.5 mmol/mol, which is similar to some anti-diabetic medications, such as DPP-4 inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors,” she said.

The low-fat group reduced A1c by 3.4 mmol/mol, resulting in a between-group difference of 6.1 mmol/mol.

“Upon follow-up of 3 months, after stopping the diets, on average the participants in both groups returned their HbA1c levels to nearly baseline values,” she said. Results were adjusted for weight loss and baseline values.

Both diets also improved the NAS. The proportion of participants who improved their NAS score by 2 or more points was 22% in the LCHF group versus 17% in the low-fat group (P = 0.58). Additionally, in the LCHF group, 70% of participants improved their score by 1 or more points, compared with 49% in the low-fat group and fewer in the LCHF group experienced a worsening of their score (1% vs. 23%, respectively).

One participant on LCHF had high triglycerides of 12 mmol/L after 3 months. Overall, the low-density lipoprotein increased marginally by 0.2 mmol per liter in the high-fat group, said Dr. Dalby Hansen.

Dr. Dalby Hansen noted some limitations. The findings might not be applicable in more severe NAFLD, dietary assessment relied on self-reporting, no food was provided, and participants had to cook themselves. It was also an open-label study because of the nature of the intervention.

Some hope for more sustainable dieting

Many diets are difficult to adhere to, remarked Dr. Dalby Hansen. “We thought this [diet] might be easier to comply with in the longer term, and we hope that these results might provide patients with more options.”

She added that most people who started the diet adapted and complied with it. “However, it might not be for everyone, but I think we can say that if people try, and it fits into their lives, then they go for it.”

However, “it is not about going out and eating whatever fat and how much of it you want. It’s important that you cut the carbohydrates too,” she said. “With this approach, we really saw amazing results.”

Dr. Dalby Hansen added that having various diets available, including the LCHF one, meant that as clinicians they could empower patients to take control of their metabolic health.

“We can ask them directly, ‘What would fit into their life?’” she said. “We know that one size does not fit at all, and I believe that if we could engage patients more, then they can take control of their own situation.”

Asked whether these findings were enough to change guidelines, Zobair Younossi, MD, professor and chairman, department of medicine, Inova Fairfax Medical Campus, Falls Church, Va., remarked that it was the sugar at work here.

“Dietary fat – it’s not the same as fat in the liver, and this diet has more to do with the sugar levels,” he said.

“I’m always reluctant to take results from a short-term study without long-term follow-up,” Dr. Younossi said. “I want to know will patients live longer, and long-term data are needed for this. Until I have that strong evidence that outcomes are going to change, or at least some sign that the outcome is going to change, it is too early to change any guidelines.”

Dr. Dalby Hansen reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Harrison reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Younossi reports the following financial relationships: research funds and/or consultant to Abbott, Allergan, Bristol Myers Squibb, Echosens, Genfit, Gilead Sciences, Intercept, Madrigal, Merck, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LONDON – A low-carbohydrate, high-fat (LCHF) diet reduced the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and despite no calorie restriction, participants with both NAFLD and type 2 diabetes lost 5.8% of their body weight, according to a randomized controlled study.

“Based on these results, the LCHF diet may be recommended to people with NAFLD and type 2 diabetes,” said Camilla Dalby Hansen, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, who presented the data at the International Liver Congress (ILC) 2022.

“Basically, if you have fat in your liver, you will benefit from eating fat,” she said.

The LCHF diet was compared with a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet more typically followed for these conditions. The low-fat diet was also found to reduce the progression of NAFLD, but to a lesser extent than the LCHF diet.

Dr. Dalby Hansen called their study one of the most extensive investigations of the LCHF diet in patients with type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease.

“Combining this [reduction in NAFLD score] with the huge weight loss, the lower HbA1c [blood sugar], the lowering of blood pressure in women, the rise in HDL levels, and reduction in triglycerides – all in all, this diet is very promising,” she said.

Stephen Harrison, MD, visiting professor, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, medical director of Pinnacle Clinical Research and president of Summit Clinical Research, San Antonio, commended Dr. Dalby Hansen on her methodology, which included before-and-after liver biopsies. “It’s a heinous effort to do paired liver biopsies in a lifestyle modification trial. That’s huge.”

“This study tells me that the way we manage patients doesn’t change – it is still lifestyle modification,” said Dr. Harrison, who was not involved with the study. “It’s eat less [rather] than more. It’s exercise and try to lose weight. In the long term, we give patients benefit, and we show that the disease has improved, and we offer something that means they can maintain a healthy life.”

He added that the relatively small and short trial was informative.

“They improved the NAFLD activity score [NAS],” he said. “I don’t know by how much. There was no change in fibrosis, but we wouldn’t expect this at 6 months.”

“It’s provocative work, and it gives us healthy information about how we can help manage our patients from a lifestyle perspective,” he concluded.

‘Do not lose weight. Eat until you are full’

In the study, 110 participants with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, aged 18-78 years, were allocated to the LCHF diet, and 55 were allocated to the low-fat diet for 6 months.

The researchers performed liver biopsies at baseline and 6 months, which were blinded for scoring.

Participants had ongoing dietitian consultations, with follow-up visits at 3 and 6 months. Compliance was reported continuously through an online food diary platform.

The primary endpoint was change in glycemic control as measured by A1c level over 6 months. The secondary endpoints comprised the proportion of participants with changes in the NAS of at least 2 points over 6 months. Both these measures were compared between the two dietary groups.

The two groups were matched at baseline, with a mean age of 55-57 years, 58% were women, 89% with metabolic syndrome, and a mean BMI 34 kg/m2.

In baseline liver disease, F1 level fibrosis was the most common (58%), followed by hepatic steatosis (S1, 47%; S2, 32%), with a median NAS of 3, and 19% had nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

The special thing about these diets was that participants were told to “not lose weight, but eat until you are full,” remarked Dr. Dalby Hansen.

Those on the LCHF diet consumed an average of 61% energy from fat, 13% from carbohydrates, and 23% from protein, compared with the low-fat diet, which comprised an average of 29% energy from fat, 46% from carbohydrates, and 21% from protein.

“It’s a lot of fat and corresponds to a quarter of a liter of olive oil per day,” said Dr. Dalby Hansen. “They really had to change their mindset a lot, because it was difficult for them to start eating all these fats, especially since we’ve all been told for decades that it isn’t good. But we supported them, and they got into it.”

The LCHF diet was primarily comprised of unsaturated fats – for example, avocado, oil, nuts, and seeds – but also included saturated fats, such as cheese, cream, and high-fat dairy products. Participants were free to eat unsaturated and saturated fats, but Dr. Dalby Hansen and her team advised participants that “good” unsaturated fats were preferable.

“Also, this diet contained vegetables but no bread, no potatoes, no rice, and no pasta. It was low in carbohydrates, below 20%,” she added.

Improved glycemic control, reduced liver fat

“We found that the LCHF diet improved diabetes control, it reduced the fat in the liver, and, even though they’re eating as many calories as they were used to until they were full, they lost 5.8% of body weight,” said Dr. Dalby Hansen in reporting the results. Participants in the low-fat group lost only 1.8% of body weight.

However, mean calorie intake dropped in both groups, by –2.2% in the LCHF group and –8.7% in the low-fat group.

“The LCHF diet improved the primary outcome of A1c by 9.5 mmol/mol, which is similar to some anti-diabetic medications, such as DPP-4 inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors,” she said.

The low-fat group reduced A1c by 3.4 mmol/mol, resulting in a between-group difference of 6.1 mmol/mol.

“Upon follow-up of 3 months, after stopping the diets, on average the participants in both groups returned their HbA1c levels to nearly baseline values,” she said. Results were adjusted for weight loss and baseline values.

Both diets also improved the NAS. The proportion of participants who improved their NAS score by 2 or more points was 22% in the LCHF group versus 17% in the low-fat group (P = 0.58). Additionally, in the LCHF group, 70% of participants improved their score by 1 or more points, compared with 49% in the low-fat group and fewer in the LCHF group experienced a worsening of their score (1% vs. 23%, respectively).

One participant on LCHF had high triglycerides of 12 mmol/L after 3 months. Overall, the low-density lipoprotein increased marginally by 0.2 mmol per liter in the high-fat group, said Dr. Dalby Hansen.

Dr. Dalby Hansen noted some limitations. The findings might not be applicable in more severe NAFLD, dietary assessment relied on self-reporting, no food was provided, and participants had to cook themselves. It was also an open-label study because of the nature of the intervention.

Some hope for more sustainable dieting

Many diets are difficult to adhere to, remarked Dr. Dalby Hansen. “We thought this [diet] might be easier to comply with in the longer term, and we hope that these results might provide patients with more options.”

She added that most people who started the diet adapted and complied with it. “However, it might not be for everyone, but I think we can say that if people try, and it fits into their lives, then they go for it.”

However, “it is not about going out and eating whatever fat and how much of it you want. It’s important that you cut the carbohydrates too,” she said. “With this approach, we really saw amazing results.”

Dr. Dalby Hansen added that having various diets available, including the LCHF one, meant that as clinicians they could empower patients to take control of their metabolic health.

“We can ask them directly, ‘What would fit into their life?’” she said. “We know that one size does not fit at all, and I believe that if we could engage patients more, then they can take control of their own situation.”

Asked whether these findings were enough to change guidelines, Zobair Younossi, MD, professor and chairman, department of medicine, Inova Fairfax Medical Campus, Falls Church, Va., remarked that it was the sugar at work here.

“Dietary fat – it’s not the same as fat in the liver, and this diet has more to do with the sugar levels,” he said.

“I’m always reluctant to take results from a short-term study without long-term follow-up,” Dr. Younossi said. “I want to know will patients live longer, and long-term data are needed for this. Until I have that strong evidence that outcomes are going to change, or at least some sign that the outcome is going to change, it is too early to change any guidelines.”

Dr. Dalby Hansen reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Harrison reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Younossi reports the following financial relationships: research funds and/or consultant to Abbott, Allergan, Bristol Myers Squibb, Echosens, Genfit, Gilead Sciences, Intercept, Madrigal, Merck, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LONDON – A low-carbohydrate, high-fat (LCHF) diet reduced the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and despite no calorie restriction, participants with both NAFLD and type 2 diabetes lost 5.8% of their body weight, according to a randomized controlled study.

“Based on these results, the LCHF diet may be recommended to people with NAFLD and type 2 diabetes,” said Camilla Dalby Hansen, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, who presented the data at the International Liver Congress (ILC) 2022.

“Basically, if you have fat in your liver, you will benefit from eating fat,” she said.

The LCHF diet was compared with a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet more typically followed for these conditions. The low-fat diet was also found to reduce the progression of NAFLD, but to a lesser extent than the LCHF diet.

Dr. Dalby Hansen called their study one of the most extensive investigations of the LCHF diet in patients with type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease.

“Combining this [reduction in NAFLD score] with the huge weight loss, the lower HbA1c [blood sugar], the lowering of blood pressure in women, the rise in HDL levels, and reduction in triglycerides – all in all, this diet is very promising,” she said.

Stephen Harrison, MD, visiting professor, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, medical director of Pinnacle Clinical Research and president of Summit Clinical Research, San Antonio, commended Dr. Dalby Hansen on her methodology, which included before-and-after liver biopsies. “It’s a heinous effort to do paired liver biopsies in a lifestyle modification trial. That’s huge.”

“This study tells me that the way we manage patients doesn’t change – it is still lifestyle modification,” said Dr. Harrison, who was not involved with the study. “It’s eat less [rather] than more. It’s exercise and try to lose weight. In the long term, we give patients benefit, and we show that the disease has improved, and we offer something that means they can maintain a healthy life.”

He added that the relatively small and short trial was informative.

“They improved the NAFLD activity score [NAS],” he said. “I don’t know by how much. There was no change in fibrosis, but we wouldn’t expect this at 6 months.”

“It’s provocative work, and it gives us healthy information about how we can help manage our patients from a lifestyle perspective,” he concluded.

‘Do not lose weight. Eat until you are full’

In the study, 110 participants with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, aged 18-78 years, were allocated to the LCHF diet, and 55 were allocated to the low-fat diet for 6 months.

The researchers performed liver biopsies at baseline and 6 months, which were blinded for scoring.

Participants had ongoing dietitian consultations, with follow-up visits at 3 and 6 months. Compliance was reported continuously through an online food diary platform.

The primary endpoint was change in glycemic control as measured by A1c level over 6 months. The secondary endpoints comprised the proportion of participants with changes in the NAS of at least 2 points over 6 months. Both these measures were compared between the two dietary groups.

The two groups were matched at baseline, with a mean age of 55-57 years, 58% were women, 89% with metabolic syndrome, and a mean BMI 34 kg/m2.

In baseline liver disease, F1 level fibrosis was the most common (58%), followed by hepatic steatosis (S1, 47%; S2, 32%), with a median NAS of 3, and 19% had nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

The special thing about these diets was that participants were told to “not lose weight, but eat until you are full,” remarked Dr. Dalby Hansen.

Those on the LCHF diet consumed an average of 61% energy from fat, 13% from carbohydrates, and 23% from protein, compared with the low-fat diet, which comprised an average of 29% energy from fat, 46% from carbohydrates, and 21% from protein.

“It’s a lot of fat and corresponds to a quarter of a liter of olive oil per day,” said Dr. Dalby Hansen. “They really had to change their mindset a lot, because it was difficult for them to start eating all these fats, especially since we’ve all been told for decades that it isn’t good. But we supported them, and they got into it.”

The LCHF diet was primarily comprised of unsaturated fats – for example, avocado, oil, nuts, and seeds – but also included saturated fats, such as cheese, cream, and high-fat dairy products. Participants were free to eat unsaturated and saturated fats, but Dr. Dalby Hansen and her team advised participants that “good” unsaturated fats were preferable.

“Also, this diet contained vegetables but no bread, no potatoes, no rice, and no pasta. It was low in carbohydrates, below 20%,” she added.

Improved glycemic control, reduced liver fat

“We found that the LCHF diet improved diabetes control, it reduced the fat in the liver, and, even though they’re eating as many calories as they were used to until they were full, they lost 5.8% of body weight,” said Dr. Dalby Hansen in reporting the results. Participants in the low-fat group lost only 1.8% of body weight.

However, mean calorie intake dropped in both groups, by –2.2% in the LCHF group and –8.7% in the low-fat group.

“The LCHF diet improved the primary outcome of A1c by 9.5 mmol/mol, which is similar to some anti-diabetic medications, such as DPP-4 inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors,” she said.

The low-fat group reduced A1c by 3.4 mmol/mol, resulting in a between-group difference of 6.1 mmol/mol.

“Upon follow-up of 3 months, after stopping the diets, on average the participants in both groups returned their HbA1c levels to nearly baseline values,” she said. Results were adjusted for weight loss and baseline values.

Both diets also improved the NAS. The proportion of participants who improved their NAS score by 2 or more points was 22% in the LCHF group versus 17% in the low-fat group (P = 0.58). Additionally, in the LCHF group, 70% of participants improved their score by 1 or more points, compared with 49% in the low-fat group and fewer in the LCHF group experienced a worsening of their score (1% vs. 23%, respectively).

One participant on LCHF had high triglycerides of 12 mmol/L after 3 months. Overall, the low-density lipoprotein increased marginally by 0.2 mmol per liter in the high-fat group, said Dr. Dalby Hansen.

Dr. Dalby Hansen noted some limitations. The findings might not be applicable in more severe NAFLD, dietary assessment relied on self-reporting, no food was provided, and participants had to cook themselves. It was also an open-label study because of the nature of the intervention.

Some hope for more sustainable dieting

Many diets are difficult to adhere to, remarked Dr. Dalby Hansen. “We thought this [diet] might be easier to comply with in the longer term, and we hope that these results might provide patients with more options.”

She added that most people who started the diet adapted and complied with it. “However, it might not be for everyone, but I think we can say that if people try, and it fits into their lives, then they go for it.”

However, “it is not about going out and eating whatever fat and how much of it you want. It’s important that you cut the carbohydrates too,” she said. “With this approach, we really saw amazing results.”

Dr. Dalby Hansen added that having various diets available, including the LCHF one, meant that as clinicians they could empower patients to take control of their metabolic health.

“We can ask them directly, ‘What would fit into their life?’” she said. “We know that one size does not fit at all, and I believe that if we could engage patients more, then they can take control of their own situation.”

Asked whether these findings were enough to change guidelines, Zobair Younossi, MD, professor and chairman, department of medicine, Inova Fairfax Medical Campus, Falls Church, Va., remarked that it was the sugar at work here.

“Dietary fat – it’s not the same as fat in the liver, and this diet has more to do with the sugar levels,” he said.

“I’m always reluctant to take results from a short-term study without long-term follow-up,” Dr. Younossi said. “I want to know will patients live longer, and long-term data are needed for this. Until I have that strong evidence that outcomes are going to change, or at least some sign that the outcome is going to change, it is too early to change any guidelines.”

Dr. Dalby Hansen reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Harrison reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Younossi reports the following financial relationships: research funds and/or consultant to Abbott, Allergan, Bristol Myers Squibb, Echosens, Genfit, Gilead Sciences, Intercept, Madrigal, Merck, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ILC 2022

At-home colorectal cancer testing and follow-up vary by ethnicity

Doctors were significantly less likely to order colorectal cancer screening with the at-home test Cologuard (Exact Sciences) for Black patients and were more likely to order the test for Asian patients, new evidence reveals.

Investigators retrospectively studied 557,156 patients in the Mayo Clinic health system from 2012 to 2022. They found that Cologuard was ordered for 8.7% of Black patients, compared to 11.9% of White patients and 13.1% of Asian patients.

Both minority groups were less likely than White patients to undergo a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of Cologuard testing. Cologuard tests the stool for blood and DNA markers associated with colorectal cancer.

Although the researchers did not examine the reasons driving the disparities, lead investigator Ahmed Ouni, MD, told this news organization that “it could be patient preferences ... or there could be some bias as providers ourselves in how we present the data to patients.”

Dr. Ouni presented the findings on May 22 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), held in person in San Diego and virtually.

Breakdown by physician specialty

“We looked at the specialty of physicians ordering these because we wanted to see where the disparity was coming from, if there was a disparity,” said Dr. Ouni, a gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida.

Just over half (51%) of the patients received care from family medicine physicians, 27% received care from internists, and 22% were seen by gastroenterologists.

Family physicians ordered Cologuard testing for 8.7% of Black patients, compared with 16.1% of White patients, a significant difference (P < .001). Internists ordered the test for 10.5% of Black patients and 11.1% of White patients (P < .001). Gastroenterologists ordered Cologuard screening for 2.4% of Black patients and 3.2% of White patients (P = .009).

Gastroenterologists were 47% more likely to order Cologuard for Asian patients, and internists were 16% more likely to order it for this population than for White patients. However, the findings were not statistically significant for the overall cohort of Asian patients when the researchers adjusted for age and sex (P = 0.52).

Black patients were 25% less likely to have a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of undergoing a Cologuard test (odds ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.94), and Asian patients were 35% less likely (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.52-0.82).

Ongoing and future research

Of the total study population, only 2.9% self-identified as Black; according to the 2020 U.S. Census, 12.4% of the population of the United States are Black persons.

When asked about the relatively low proportion of Black persons in the study, Dr. Ouni replied that the investigators are partnering with a Black physician group in the Jacksonville, Fla., area to expand the study to a more diverse population.

Additional plans include assessing how many positive Cologuard test results led to follow-up colonoscopies.

The investigators are also working with family physicians at the Mayo Clinic to examine how physicians explain colorectal cancer screening options to patients and are studying patient preferences regarding screening options, which include Cologuard, fecal immunochemical test (FIT)/fecal occult blood testing, CT colonography, and colonoscopy.

“We’re analyzing the data by ZIP code to see if this could be related to finances,” Dr. Ouni added. “So, if you’re Black or White and more financially impoverished, how does that affect how you view Cologuard and colorectal cancer screening?”

Some unanswered questions

“Overall this study supports other studies of a disparity in colorectal cancer screening for African Americans,” John M. Carethers, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment. “This is known for FIT and colonoscopy, and Cologuard, which is a genetic test in addition to FIT, appears to be in that same realm.”

“Noninvasive tests will have a role to reach populations who may not readily have access to colonoscopy,” said Dr. Carethers, John G. Searle Professor and chair of the department of internal medicine and professor of human genetics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and president of the American Gastroenterological Association. “The key here is if the test is positive, it needs to be followed up with a colonoscopy.”

Dr. Carethers added that the study raises some unanswered questions; for example, does the cost difference between testing options make a difference?

“FIT is under $20, but Cologuard is generally $300 or more,” he said. What percentage of the study population were offered other options, such as FIT? How does insurance status affect screening in different populations?”

“The findings should be taken in context of what other screening options were offered to or elected by patients,” agreed Gregory S. Cooper, MD, professor of medicine and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University and a gastroenterologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

According to guidelines, patients can be offered a menu of options, including FIT, colonoscopy, and Cologuard, Dr. Cooper said in an interview.

“If more African Americans elected colonoscopy, for example, the findings may balance out,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not affiliated with the study. “It would also be of interest to know if the racial differences changed over time. With the pandemic, the use of noninvasive options, such as Cologuard, have increased.”

“I will note that specifically for colonoscopy in the United States, the disparity gap had been closing from about 15% to 18% 20 years ago to about 3% in 2020 pre-COVID,” Dr. Carethers added. “I am fearful that COVID may have led to a widening of that gap again as we get more data.”

“It is important that noninvasive tests for screening be a part of the portfolio of offerings to patients, as about 35% of eligible at-risk persons who need to be screened are not screened in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said.

The study was not industry sponsored. Dr. Ouni and Dr. Carethers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Cooper has received consulting fees from Exact Sciences.

To help your patients understand their colorectal cancer screening options, send them to the AGA GI Patient Center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors were significantly less likely to order colorectal cancer screening with the at-home test Cologuard (Exact Sciences) for Black patients and were more likely to order the test for Asian patients, new evidence reveals.

Investigators retrospectively studied 557,156 patients in the Mayo Clinic health system from 2012 to 2022. They found that Cologuard was ordered for 8.7% of Black patients, compared to 11.9% of White patients and 13.1% of Asian patients.

Both minority groups were less likely than White patients to undergo a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of Cologuard testing. Cologuard tests the stool for blood and DNA markers associated with colorectal cancer.

Although the researchers did not examine the reasons driving the disparities, lead investigator Ahmed Ouni, MD, told this news organization that “it could be patient preferences ... or there could be some bias as providers ourselves in how we present the data to patients.”

Dr. Ouni presented the findings on May 22 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), held in person in San Diego and virtually.

Breakdown by physician specialty

“We looked at the specialty of physicians ordering these because we wanted to see where the disparity was coming from, if there was a disparity,” said Dr. Ouni, a gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida.

Just over half (51%) of the patients received care from family medicine physicians, 27% received care from internists, and 22% were seen by gastroenterologists.

Family physicians ordered Cologuard testing for 8.7% of Black patients, compared with 16.1% of White patients, a significant difference (P < .001). Internists ordered the test for 10.5% of Black patients and 11.1% of White patients (P < .001). Gastroenterologists ordered Cologuard screening for 2.4% of Black patients and 3.2% of White patients (P = .009).

Gastroenterologists were 47% more likely to order Cologuard for Asian patients, and internists were 16% more likely to order it for this population than for White patients. However, the findings were not statistically significant for the overall cohort of Asian patients when the researchers adjusted for age and sex (P = 0.52).

Black patients were 25% less likely to have a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of undergoing a Cologuard test (odds ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.94), and Asian patients were 35% less likely (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.52-0.82).

Ongoing and future research

Of the total study population, only 2.9% self-identified as Black; according to the 2020 U.S. Census, 12.4% of the population of the United States are Black persons.

When asked about the relatively low proportion of Black persons in the study, Dr. Ouni replied that the investigators are partnering with a Black physician group in the Jacksonville, Fla., area to expand the study to a more diverse population.

Additional plans include assessing how many positive Cologuard test results led to follow-up colonoscopies.

The investigators are also working with family physicians at the Mayo Clinic to examine how physicians explain colorectal cancer screening options to patients and are studying patient preferences regarding screening options, which include Cologuard, fecal immunochemical test (FIT)/fecal occult blood testing, CT colonography, and colonoscopy.

“We’re analyzing the data by ZIP code to see if this could be related to finances,” Dr. Ouni added. “So, if you’re Black or White and more financially impoverished, how does that affect how you view Cologuard and colorectal cancer screening?”

Some unanswered questions

“Overall this study supports other studies of a disparity in colorectal cancer screening for African Americans,” John M. Carethers, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment. “This is known for FIT and colonoscopy, and Cologuard, which is a genetic test in addition to FIT, appears to be in that same realm.”

“Noninvasive tests will have a role to reach populations who may not readily have access to colonoscopy,” said Dr. Carethers, John G. Searle Professor and chair of the department of internal medicine and professor of human genetics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and president of the American Gastroenterological Association. “The key here is if the test is positive, it needs to be followed up with a colonoscopy.”

Dr. Carethers added that the study raises some unanswered questions; for example, does the cost difference between testing options make a difference?

“FIT is under $20, but Cologuard is generally $300 or more,” he said. What percentage of the study population were offered other options, such as FIT? How does insurance status affect screening in different populations?”

“The findings should be taken in context of what other screening options were offered to or elected by patients,” agreed Gregory S. Cooper, MD, professor of medicine and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University and a gastroenterologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

According to guidelines, patients can be offered a menu of options, including FIT, colonoscopy, and Cologuard, Dr. Cooper said in an interview.

“If more African Americans elected colonoscopy, for example, the findings may balance out,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not affiliated with the study. “It would also be of interest to know if the racial differences changed over time. With the pandemic, the use of noninvasive options, such as Cologuard, have increased.”

“I will note that specifically for colonoscopy in the United States, the disparity gap had been closing from about 15% to 18% 20 years ago to about 3% in 2020 pre-COVID,” Dr. Carethers added. “I am fearful that COVID may have led to a widening of that gap again as we get more data.”

“It is important that noninvasive tests for screening be a part of the portfolio of offerings to patients, as about 35% of eligible at-risk persons who need to be screened are not screened in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said.

The study was not industry sponsored. Dr. Ouni and Dr. Carethers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Cooper has received consulting fees from Exact Sciences.

To help your patients understand their colorectal cancer screening options, send them to the AGA GI Patient Center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors were significantly less likely to order colorectal cancer screening with the at-home test Cologuard (Exact Sciences) for Black patients and were more likely to order the test for Asian patients, new evidence reveals.

Investigators retrospectively studied 557,156 patients in the Mayo Clinic health system from 2012 to 2022. They found that Cologuard was ordered for 8.7% of Black patients, compared to 11.9% of White patients and 13.1% of Asian patients.

Both minority groups were less likely than White patients to undergo a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of Cologuard testing. Cologuard tests the stool for blood and DNA markers associated with colorectal cancer.

Although the researchers did not examine the reasons driving the disparities, lead investigator Ahmed Ouni, MD, told this news organization that “it could be patient preferences ... or there could be some bias as providers ourselves in how we present the data to patients.”

Dr. Ouni presented the findings on May 22 at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), held in person in San Diego and virtually.

Breakdown by physician specialty

“We looked at the specialty of physicians ordering these because we wanted to see where the disparity was coming from, if there was a disparity,” said Dr. Ouni, a gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida.

Just over half (51%) of the patients received care from family medicine physicians, 27% received care from internists, and 22% were seen by gastroenterologists.

Family physicians ordered Cologuard testing for 8.7% of Black patients, compared with 16.1% of White patients, a significant difference (P < .001). Internists ordered the test for 10.5% of Black patients and 11.1% of White patients (P < .001). Gastroenterologists ordered Cologuard screening for 2.4% of Black patients and 3.2% of White patients (P = .009).

Gastroenterologists were 47% more likely to order Cologuard for Asian patients, and internists were 16% more likely to order it for this population than for White patients. However, the findings were not statistically significant for the overall cohort of Asian patients when the researchers adjusted for age and sex (P = 0.52).

Black patients were 25% less likely to have a follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year of undergoing a Cologuard test (odds ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.94), and Asian patients were 35% less likely (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.52-0.82).

Ongoing and future research

Of the total study population, only 2.9% self-identified as Black; according to the 2020 U.S. Census, 12.4% of the population of the United States are Black persons.

When asked about the relatively low proportion of Black persons in the study, Dr. Ouni replied that the investigators are partnering with a Black physician group in the Jacksonville, Fla., area to expand the study to a more diverse population.

Additional plans include assessing how many positive Cologuard test results led to follow-up colonoscopies.

The investigators are also working with family physicians at the Mayo Clinic to examine how physicians explain colorectal cancer screening options to patients and are studying patient preferences regarding screening options, which include Cologuard, fecal immunochemical test (FIT)/fecal occult blood testing, CT colonography, and colonoscopy.

“We’re analyzing the data by ZIP code to see if this could be related to finances,” Dr. Ouni added. “So, if you’re Black or White and more financially impoverished, how does that affect how you view Cologuard and colorectal cancer screening?”

Some unanswered questions

“Overall this study supports other studies of a disparity in colorectal cancer screening for African Americans,” John M. Carethers, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment. “This is known for FIT and colonoscopy, and Cologuard, which is a genetic test in addition to FIT, appears to be in that same realm.”

“Noninvasive tests will have a role to reach populations who may not readily have access to colonoscopy,” said Dr. Carethers, John G. Searle Professor and chair of the department of internal medicine and professor of human genetics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and president of the American Gastroenterological Association. “The key here is if the test is positive, it needs to be followed up with a colonoscopy.”

Dr. Carethers added that the study raises some unanswered questions; for example, does the cost difference between testing options make a difference?

“FIT is under $20, but Cologuard is generally $300 or more,” he said. What percentage of the study population were offered other options, such as FIT? How does insurance status affect screening in different populations?”

“The findings should be taken in context of what other screening options were offered to or elected by patients,” agreed Gregory S. Cooper, MD, professor of medicine and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University and a gastroenterologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

According to guidelines, patients can be offered a menu of options, including FIT, colonoscopy, and Cologuard, Dr. Cooper said in an interview.

“If more African Americans elected colonoscopy, for example, the findings may balance out,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not affiliated with the study. “It would also be of interest to know if the racial differences changed over time. With the pandemic, the use of noninvasive options, such as Cologuard, have increased.”

“I will note that specifically for colonoscopy in the United States, the disparity gap had been closing from about 15% to 18% 20 years ago to about 3% in 2020 pre-COVID,” Dr. Carethers added. “I am fearful that COVID may have led to a widening of that gap again as we get more data.”

“It is important that noninvasive tests for screening be a part of the portfolio of offerings to patients, as about 35% of eligible at-risk persons who need to be screened are not screened in the United States,” Dr. Carethers said.

The study was not industry sponsored. Dr. Ouni and Dr. Carethers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Cooper has received consulting fees from Exact Sciences.

To help your patients understand their colorectal cancer screening options, send them to the AGA GI Patient Center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Acute hepatitis cases in children show declining trend; adenovirus, COVID-19 remain key leads

LONDON – Case numbers of acute hepatitis in children show “a declining trajectory,” and COVID-19 and adenovirus remain the most likely, but as yet unproven, causative agents, said experts in an update at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Philippa Easterbrook, MD, medical expert at the World Health Organization Global HIV, Hepatitis, and STI Programme, shared the latest case numbers and working hypotheses of possible causative agents in the outbreak of acute hepatitis among children in Europe and beyond.

Global data across the five WHO regions show there were 244 cases in the past month, bringing the total to 894 probable cases reported since October 2021 from 33 countries.

“It’s important to remember that this includes new cases, as well as retrospectively identified cases,” Dr.Easterbrook said. “Over half (52%) are from the European region, while 262 cases (30% of the global total) are from the United Kingdom.”

Data from Europe and the United States show a declining trajectory of reports of new cases. “This is a positive development,” she said.

The second highest reporting region is the Americas, she said, with 368 cases total, 290 cases of which come from the United States, accounting for 35% of the global total.

“Together the United Kingdom and the United States make up 65% of the global total,” she said.

Dr. Easterbrook added that 17 of the 33 reporting countries had more than five cases. Most cases (75%) are in young children under 5 years of age.

Serious cases are relatively few, but 44 (5%) children have required liver transplantation. Data from the European region show that 30% have required intensive care at some point during their hospitalization. There have been 18 (2%) reported deaths.

Possible post-COVID phenomenon, adenovirus most commonly reported

Dr. Easterbrook acknowledged the emerging hypothesis of a post-COVID phenomenon.

“Is this a variant of the rare but recognized multisystem inflammatory syndrome condition in children that’s been reported, often 1-2 months after COVID, causing widespread organ damage?” But she pointed out that the reported COVID cases with hepatitis “don’t seem to fit these features.”

Adenovirus remains the most commonly detected virus in acute hepatitis in children, found in 53% of cases overall, she said. The adenovirus detection rate is higher in the United Kingdom, at 68%.

“There are quite high rates of detection, but they’re not in all cases. There does seem to be a high rate of detection in the younger age groups and in those who are developing severe disease, so perhaps there is some link to severity,” Dr. Easterbrook said.

The working hypotheses continue to favor adenovirus together with past or current SARS-CoV-2 infection, as proposed early in the outbreak, she said. “These either work independently or work together as cofactors in some way to result in hepatitis. And there has been some clear progress on this. WHO is bringing together the data from different countries on some of these working hypotheses.”

Dr. Easterbrook highlighted the importance of procuring global data, especially given that two countries are reporting the majority of cases and in high numbers. “It’s a mixed picture with different rates of adenovirus detection and of COVID,” she said. “We need good-quality data collected in a standardized way.” WHO is requesting that countries provide these data.

She also highlighted the need for good in-depth studies, citing the UK Health Security Agency as an example of this. “There’s only a few countries that have the capacity or the patient numbers to look at this in detail, for example, the U.K. and the UKHSA.”

She noted that the UKHSA had laid out a comprehensive, systematic set of further investigations. For example, a case-control study is trying to establish whether there is a difference in the rate of adenovirus detection in children with hepatitis compared with other hospitalized children at the same time. “This aims to really tease out whether adenovirus is a cause or just a bystander,” she said.

She added that there were also genetic studies investigating whether genes were predisposing some children to develop a more severe form of disease. Other studies are evaluating the immune response of the patients.

Dr. Easterbrook added that the WHO will soon launch a global survey asking whether the reports of acute hepatitis are greater than the expected background rate for cases of hepatitis of unknown etiology.

Acute hepatitis is not new, but high caseload is

Also speaking at the ILC special briefing was Maria Buti, MD, PhD, policy and public health chair for the European Association for the Study of the Liver, and chief of the internal medicine and hepatology department at Hospital General Universitari Valle Hebron in Barcelona.

Dr. Buti drew attention to the fact that severe acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in children is not new.

“We have cases of acute hepatitis that even needed liver transplantation some years ago, and every year in our clinics we see these type of patients,” Dr. Buti remarked. What is really new, she added, is the amount of cases, particularly in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Easterbrook and Dr. Buti have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LONDON – Case numbers of acute hepatitis in children show “a declining trajectory,” and COVID-19 and adenovirus remain the most likely, but as yet unproven, causative agents, said experts in an update at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Philippa Easterbrook, MD, medical expert at the World Health Organization Global HIV, Hepatitis, and STI Programme, shared the latest case numbers and working hypotheses of possible causative agents in the outbreak of acute hepatitis among children in Europe and beyond.

Global data across the five WHO regions show there were 244 cases in the past month, bringing the total to 894 probable cases reported since October 2021 from 33 countries.

“It’s important to remember that this includes new cases, as well as retrospectively identified cases,” Dr.Easterbrook said. “Over half (52%) are from the European region, while 262 cases (30% of the global total) are from the United Kingdom.”

Data from Europe and the United States show a declining trajectory of reports of new cases. “This is a positive development,” she said.

The second highest reporting region is the Americas, she said, with 368 cases total, 290 cases of which come from the United States, accounting for 35% of the global total.

“Together the United Kingdom and the United States make up 65% of the global total,” she said.

Dr. Easterbrook added that 17 of the 33 reporting countries had more than five cases. Most cases (75%) are in young children under 5 years of age.

Serious cases are relatively few, but 44 (5%) children have required liver transplantation. Data from the European region show that 30% have required intensive care at some point during their hospitalization. There have been 18 (2%) reported deaths.

Possible post-COVID phenomenon, adenovirus most commonly reported

Dr. Easterbrook acknowledged the emerging hypothesis of a post-COVID phenomenon.

“Is this a variant of the rare but recognized multisystem inflammatory syndrome condition in children that’s been reported, often 1-2 months after COVID, causing widespread organ damage?” But she pointed out that the reported COVID cases with hepatitis “don’t seem to fit these features.”

Adenovirus remains the most commonly detected virus in acute hepatitis in children, found in 53% of cases overall, she said. The adenovirus detection rate is higher in the United Kingdom, at 68%.

“There are quite high rates of detection, but they’re not in all cases. There does seem to be a high rate of detection in the younger age groups and in those who are developing severe disease, so perhaps there is some link to severity,” Dr. Easterbrook said.

The working hypotheses continue to favor adenovirus together with past or current SARS-CoV-2 infection, as proposed early in the outbreak, she said. “These either work independently or work together as cofactors in some way to result in hepatitis. And there has been some clear progress on this. WHO is bringing together the data from different countries on some of these working hypotheses.”

Dr. Easterbrook highlighted the importance of procuring global data, especially given that two countries are reporting the majority of cases and in high numbers. “It’s a mixed picture with different rates of adenovirus detection and of COVID,” she said. “We need good-quality data collected in a standardized way.” WHO is requesting that countries provide these data.

She also highlighted the need for good in-depth studies, citing the UK Health Security Agency as an example of this. “There’s only a few countries that have the capacity or the patient numbers to look at this in detail, for example, the U.K. and the UKHSA.”

She noted that the UKHSA had laid out a comprehensive, systematic set of further investigations. For example, a case-control study is trying to establish whether there is a difference in the rate of adenovirus detection in children with hepatitis compared with other hospitalized children at the same time. “This aims to really tease out whether adenovirus is a cause or just a bystander,” she said.

She added that there were also genetic studies investigating whether genes were predisposing some children to develop a more severe form of disease. Other studies are evaluating the immune response of the patients.

Dr. Easterbrook added that the WHO will soon launch a global survey asking whether the reports of acute hepatitis are greater than the expected background rate for cases of hepatitis of unknown etiology.

Acute hepatitis is not new, but high caseload is

Also speaking at the ILC special briefing was Maria Buti, MD, PhD, policy and public health chair for the European Association for the Study of the Liver, and chief of the internal medicine and hepatology department at Hospital General Universitari Valle Hebron in Barcelona.

Dr. Buti drew attention to the fact that severe acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in children is not new.

“We have cases of acute hepatitis that even needed liver transplantation some years ago, and every year in our clinics we see these type of patients,” Dr. Buti remarked. What is really new, she added, is the amount of cases, particularly in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Easterbrook and Dr. Buti have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LONDON – Case numbers of acute hepatitis in children show “a declining trajectory,” and COVID-19 and adenovirus remain the most likely, but as yet unproven, causative agents, said experts in an update at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

Philippa Easterbrook, MD, medical expert at the World Health Organization Global HIV, Hepatitis, and STI Programme, shared the latest case numbers and working hypotheses of possible causative agents in the outbreak of acute hepatitis among children in Europe and beyond.

Global data across the five WHO regions show there were 244 cases in the past month, bringing the total to 894 probable cases reported since October 2021 from 33 countries.

“It’s important to remember that this includes new cases, as well as retrospectively identified cases,” Dr.Easterbrook said. “Over half (52%) are from the European region, while 262 cases (30% of the global total) are from the United Kingdom.”

Data from Europe and the United States show a declining trajectory of reports of new cases. “This is a positive development,” she said.

The second highest reporting region is the Americas, she said, with 368 cases total, 290 cases of which come from the United States, accounting for 35% of the global total.

“Together the United Kingdom and the United States make up 65% of the global total,” she said.

Dr. Easterbrook added that 17 of the 33 reporting countries had more than five cases. Most cases (75%) are in young children under 5 years of age.

Serious cases are relatively few, but 44 (5%) children have required liver transplantation. Data from the European region show that 30% have required intensive care at some point during their hospitalization. There have been 18 (2%) reported deaths.

Possible post-COVID phenomenon, adenovirus most commonly reported

Dr. Easterbrook acknowledged the emerging hypothesis of a post-COVID phenomenon.

“Is this a variant of the rare but recognized multisystem inflammatory syndrome condition in children that’s been reported, often 1-2 months after COVID, causing widespread organ damage?” But she pointed out that the reported COVID cases with hepatitis “don’t seem to fit these features.”

Adenovirus remains the most commonly detected virus in acute hepatitis in children, found in 53% of cases overall, she said. The adenovirus detection rate is higher in the United Kingdom, at 68%.

“There are quite high rates of detection, but they’re not in all cases. There does seem to be a high rate of detection in the younger age groups and in those who are developing severe disease, so perhaps there is some link to severity,” Dr. Easterbrook said.

The working hypotheses continue to favor adenovirus together with past or current SARS-CoV-2 infection, as proposed early in the outbreak, she said. “These either work independently or work together as cofactors in some way to result in hepatitis. And there has been some clear progress on this. WHO is bringing together the data from different countries on some of these working hypotheses.”

Dr. Easterbrook highlighted the importance of procuring global data, especially given that two countries are reporting the majority of cases and in high numbers. “It’s a mixed picture with different rates of adenovirus detection and of COVID,” she said. “We need good-quality data collected in a standardized way.” WHO is requesting that countries provide these data.

She also highlighted the need for good in-depth studies, citing the UK Health Security Agency as an example of this. “There’s only a few countries that have the capacity or the patient numbers to look at this in detail, for example, the U.K. and the UKHSA.”

She noted that the UKHSA had laid out a comprehensive, systematic set of further investigations. For example, a case-control study is trying to establish whether there is a difference in the rate of adenovirus detection in children with hepatitis compared with other hospitalized children at the same time. “This aims to really tease out whether adenovirus is a cause or just a bystander,” she said.

She added that there were also genetic studies investigating whether genes were predisposing some children to develop a more severe form of disease. Other studies are evaluating the immune response of the patients.

Dr. Easterbrook added that the WHO will soon launch a global survey asking whether the reports of acute hepatitis are greater than the expected background rate for cases of hepatitis of unknown etiology.

Acute hepatitis is not new, but high caseload is

Also speaking at the ILC special briefing was Maria Buti, MD, PhD, policy and public health chair for the European Association for the Study of the Liver, and chief of the internal medicine and hepatology department at Hospital General Universitari Valle Hebron in Barcelona.

Dr. Buti drew attention to the fact that severe acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in children is not new.

“We have cases of acute hepatitis that even needed liver transplantation some years ago, and every year in our clinics we see these type of patients,” Dr. Buti remarked. What is really new, she added, is the amount of cases, particularly in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Easterbrook and Dr. Buti have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ILC 2022

Pemvidutide promising for fatty liver disease

LONDON – Weight loss, lipid reductions, and “robust improvements” in lipid species associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were achieved in patients who were treated with pemvidutide in a first-in-human, phase 1 clinical trial reported at the annual International Liver Congress, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The presenting study investigator, Stephen A. Harrison, MD, said that pemvidutide, which is also being developed for the treatment of obesity, appeared to be well tolerated. There were no serious or severe adverse events, and no patient had to discontinue treatment because of side effects.

Overall, “pemvidutide represents a promising new agent,” said Dr. Harrison, medical director of Pinnacle Research in San Antonio, Texas.

Dual incretin effect

Pemvidutide is a “balanced” dual agonist of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucagon, Dr. Harrison explained in his oral abstract.