User login

New guidelines dispel myths about COVID-19 treatment

Recommendations, as well as conspiracy theories about COVID-19, have changed at distressing rates over the past year. No disease has ever been more politicized, or more polarizing.

Experts, as well as the least educated, take a stand on what they believe is the most important way to prevent and treat this virus.

Just recently, a study was published revealing that ivermectin is not effective as a COVID-19 treatment while people continue to claim it works. It has never been more important for doctors, and especially family physicians, to have accurate and updated guidelines.

The NIH and CDC have been publishing recommendations and guidelines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Like any new disease, these have been changing to keep up as new knowledge related to the disease becomes available.

NIH updates treatment guidelines

A recent update to the NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines was published on March 5, 2021. While the complete guidelines are quite extensive, spanning over 200 pages, it’s most important to understand the most recent updates in them.

Since preventative medicine is an integral part of primary care, it is important to note that no medications have been advised to prevent infection with COVID-19. In fact, taking drugs for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEp) is not recommended even in the highest-risk patients, such as health care workers.

In the updated guidelines, tocilizumab in a single IV dose of 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg can be given only in combination with dexamethasone (or equivalent corticosteroid) in certain hospitalized patients exhibiting rapid respiratory decompensation. These patients include recently hospitalized patients who have been admitted to the ICU within the previous 24 hours and now require mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula. Those not in the ICU who require rapidly increasing oxygen levels and have significantly increased levels of inflammatory markers should also receive this therapy. In the new guidance, the NIH recommends treating other hospitalized patients who require oxygen with remdesivir, remdesivir + dexamethasone, or dexamethasone alone.

In outpatients, those who have mild to moderate infection and are at increased risk of developing severe disease and/or hospitalization can be treated with bamlanivimab 700 mg + etesevimab 1,400 mg. This should be started as soon as possible after a confirmed diagnosis and within 10 days of symptom onset, according to the NIH recommendations. There is no evidence to support its use in patients hospitalized because of infection. However, it can be used in patients hospitalized for other reasons who have mild to moderate infection, but should be reserved – because of limited supply – for those with the highest risk of complications.

Hydroxychloroquine and casirivimab + imdevimab

One medication that has been touted in the media as a tool to treat COVID-19 has been hydroxychloroquine. Past guidelines recommended against this medication as a treatment because it lacked efficacy and posed risks for no therapeutic benefit. The most recent guidelines also recommend against the use of hydroxychloroquine for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis.

Casirivimab + imdevimab has been another talked about therapy. However, current guidelines recommend against its use in hospitalized patients. In addition, it is advised that hospitalized patients be enrolled in a clinical trial to receive it.

Since the pandemic began, the world has seen more than 120 million infections and more than 2 million deaths. Family physicians have a vital role to play as we are often the first ones patients turn to for treatment and advice. It is imperative we stay current with the guidelines and follow the most recent updates as research data are published.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Recommendations, as well as conspiracy theories about COVID-19, have changed at distressing rates over the past year. No disease has ever been more politicized, or more polarizing.

Experts, as well as the least educated, take a stand on what they believe is the most important way to prevent and treat this virus.

Just recently, a study was published revealing that ivermectin is not effective as a COVID-19 treatment while people continue to claim it works. It has never been more important for doctors, and especially family physicians, to have accurate and updated guidelines.

The NIH and CDC have been publishing recommendations and guidelines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Like any new disease, these have been changing to keep up as new knowledge related to the disease becomes available.

NIH updates treatment guidelines

A recent update to the NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines was published on March 5, 2021. While the complete guidelines are quite extensive, spanning over 200 pages, it’s most important to understand the most recent updates in them.

Since preventative medicine is an integral part of primary care, it is important to note that no medications have been advised to prevent infection with COVID-19. In fact, taking drugs for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEp) is not recommended even in the highest-risk patients, such as health care workers.

In the updated guidelines, tocilizumab in a single IV dose of 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg can be given only in combination with dexamethasone (or equivalent corticosteroid) in certain hospitalized patients exhibiting rapid respiratory decompensation. These patients include recently hospitalized patients who have been admitted to the ICU within the previous 24 hours and now require mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula. Those not in the ICU who require rapidly increasing oxygen levels and have significantly increased levels of inflammatory markers should also receive this therapy. In the new guidance, the NIH recommends treating other hospitalized patients who require oxygen with remdesivir, remdesivir + dexamethasone, or dexamethasone alone.

In outpatients, those who have mild to moderate infection and are at increased risk of developing severe disease and/or hospitalization can be treated with bamlanivimab 700 mg + etesevimab 1,400 mg. This should be started as soon as possible after a confirmed diagnosis and within 10 days of symptom onset, according to the NIH recommendations. There is no evidence to support its use in patients hospitalized because of infection. However, it can be used in patients hospitalized for other reasons who have mild to moderate infection, but should be reserved – because of limited supply – for those with the highest risk of complications.

Hydroxychloroquine and casirivimab + imdevimab

One medication that has been touted in the media as a tool to treat COVID-19 has been hydroxychloroquine. Past guidelines recommended against this medication as a treatment because it lacked efficacy and posed risks for no therapeutic benefit. The most recent guidelines also recommend against the use of hydroxychloroquine for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis.

Casirivimab + imdevimab has been another talked about therapy. However, current guidelines recommend against its use in hospitalized patients. In addition, it is advised that hospitalized patients be enrolled in a clinical trial to receive it.

Since the pandemic began, the world has seen more than 120 million infections and more than 2 million deaths. Family physicians have a vital role to play as we are often the first ones patients turn to for treatment and advice. It is imperative we stay current with the guidelines and follow the most recent updates as research data are published.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Recommendations, as well as conspiracy theories about COVID-19, have changed at distressing rates over the past year. No disease has ever been more politicized, or more polarizing.

Experts, as well as the least educated, take a stand on what they believe is the most important way to prevent and treat this virus.

Just recently, a study was published revealing that ivermectin is not effective as a COVID-19 treatment while people continue to claim it works. It has never been more important for doctors, and especially family physicians, to have accurate and updated guidelines.

The NIH and CDC have been publishing recommendations and guidelines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Like any new disease, these have been changing to keep up as new knowledge related to the disease becomes available.

NIH updates treatment guidelines

A recent update to the NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines was published on March 5, 2021. While the complete guidelines are quite extensive, spanning over 200 pages, it’s most important to understand the most recent updates in them.

Since preventative medicine is an integral part of primary care, it is important to note that no medications have been advised to prevent infection with COVID-19. In fact, taking drugs for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEp) is not recommended even in the highest-risk patients, such as health care workers.

In the updated guidelines, tocilizumab in a single IV dose of 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg can be given only in combination with dexamethasone (or equivalent corticosteroid) in certain hospitalized patients exhibiting rapid respiratory decompensation. These patients include recently hospitalized patients who have been admitted to the ICU within the previous 24 hours and now require mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen via nasal cannula. Those not in the ICU who require rapidly increasing oxygen levels and have significantly increased levels of inflammatory markers should also receive this therapy. In the new guidance, the NIH recommends treating other hospitalized patients who require oxygen with remdesivir, remdesivir + dexamethasone, or dexamethasone alone.

In outpatients, those who have mild to moderate infection and are at increased risk of developing severe disease and/or hospitalization can be treated with bamlanivimab 700 mg + etesevimab 1,400 mg. This should be started as soon as possible after a confirmed diagnosis and within 10 days of symptom onset, according to the NIH recommendations. There is no evidence to support its use in patients hospitalized because of infection. However, it can be used in patients hospitalized for other reasons who have mild to moderate infection, but should be reserved – because of limited supply – for those with the highest risk of complications.

Hydroxychloroquine and casirivimab + imdevimab

One medication that has been touted in the media as a tool to treat COVID-19 has been hydroxychloroquine. Past guidelines recommended against this medication as a treatment because it lacked efficacy and posed risks for no therapeutic benefit. The most recent guidelines also recommend against the use of hydroxychloroquine for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis.

Casirivimab + imdevimab has been another talked about therapy. However, current guidelines recommend against its use in hospitalized patients. In addition, it is advised that hospitalized patients be enrolled in a clinical trial to receive it.

Since the pandemic began, the world has seen more than 120 million infections and more than 2 million deaths. Family physicians have a vital role to play as we are often the first ones patients turn to for treatment and advice. It is imperative we stay current with the guidelines and follow the most recent updates as research data are published.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

Applying lessons from Oprah to your practice

In my last column, I explained how I’m like Tom Brady. I’m not really. Brady is a Super Bowl–winning quarterback worth over $200 million. No, I’m like Oprah. Well, trying anyway.

Brady and Oprah, in addition to being gazillionaires, have in common that they’re arguably the GOATs (Greatest Of All Time) in their fields. Watching Oprah interview Meghan Markle and Prince Harry was like watching Tom Brady on the jumbotron – she made it look easy. Her ability to create conversation and coax information from guests is hall-of-fame good. But although they are both admirable, trying to be like Brady is useful only for next Thanksgiving when you’re trying to beat your cousins from Massachusetts in touch football. .

1. Prepare ahead. It’s clear that Oprah has binders of notes about her guests and thoroughly reviewed them before she invites them to sit down. We should do the same. Open the chart and read as much as you can before you open the door. Have important information in your head so you don’t have to break from your interview to refer to it.

2. Sprinkle pleasantry. She’d never start an interview with: So why are you here? Nor should we. Even one nonscripted question or comment can help build a little rapport before getting to the work.

3. Be brief. Oprah gets her question out fast, then gets out of the way. And as a bonus, this is the easiest place to shave a few minutes from your appointments from your own end. Think for a second before you speak and try to find the shortest route to your question. Try to keep your questions to just a sentence or two.

4. Stay on it. Once you’ve discovered something relevant, stay with it, resisting the urge to finish the review of symptoms. This is not just to make a diagnosis, but as importantly, trying to diagnose “the real reason” for the visit. Then, when the question is done, own the transition. Oprah uses: “Let’s move on.” This is a bit abrupt for us, but it can be helpful if used sparingly and gently. I might soften this a little by adding “I want to be sure we have enough time to get through everything for you.”

5. Wait. A few seconds seems an eternity on the air (and in clinic), but sometimes the silent pause is just what’s needed to help the patient expand and share.

6. Be nonjudgmental. Most of us believe we’re pretty good at this, yet, it’s sometimes a blind spot. It’s easy to blame the obese patient for his stasis dermatitis or the hidradenitis patient who hasn’t stop smoking for her cysts. It also helps to be nontransactional. If you make patients feel that you’re asking questions only to extract information, you’ll never reach Oprah level.

7. Be in the moment. It is difficult, but when possible, avoid typing notes while you’re still interviewing. We’re not just there to get the facts, we’re also trying to get the story and that sometimes takes really listening.

I’m no more like Oprah than Brady, of course. But it is more fun to close my eyes and imagine myself being her when I see my next patient. That is, until Thanksgiving. Watch out, Bedards from Attleboro.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In my last column, I explained how I’m like Tom Brady. I’m not really. Brady is a Super Bowl–winning quarterback worth over $200 million. No, I’m like Oprah. Well, trying anyway.

Brady and Oprah, in addition to being gazillionaires, have in common that they’re arguably the GOATs (Greatest Of All Time) in their fields. Watching Oprah interview Meghan Markle and Prince Harry was like watching Tom Brady on the jumbotron – she made it look easy. Her ability to create conversation and coax information from guests is hall-of-fame good. But although they are both admirable, trying to be like Brady is useful only for next Thanksgiving when you’re trying to beat your cousins from Massachusetts in touch football. .

1. Prepare ahead. It’s clear that Oprah has binders of notes about her guests and thoroughly reviewed them before she invites them to sit down. We should do the same. Open the chart and read as much as you can before you open the door. Have important information in your head so you don’t have to break from your interview to refer to it.

2. Sprinkle pleasantry. She’d never start an interview with: So why are you here? Nor should we. Even one nonscripted question or comment can help build a little rapport before getting to the work.

3. Be brief. Oprah gets her question out fast, then gets out of the way. And as a bonus, this is the easiest place to shave a few minutes from your appointments from your own end. Think for a second before you speak and try to find the shortest route to your question. Try to keep your questions to just a sentence or two.

4. Stay on it. Once you’ve discovered something relevant, stay with it, resisting the urge to finish the review of symptoms. This is not just to make a diagnosis, but as importantly, trying to diagnose “the real reason” for the visit. Then, when the question is done, own the transition. Oprah uses: “Let’s move on.” This is a bit abrupt for us, but it can be helpful if used sparingly and gently. I might soften this a little by adding “I want to be sure we have enough time to get through everything for you.”

5. Wait. A few seconds seems an eternity on the air (and in clinic), but sometimes the silent pause is just what’s needed to help the patient expand and share.

6. Be nonjudgmental. Most of us believe we’re pretty good at this, yet, it’s sometimes a blind spot. It’s easy to blame the obese patient for his stasis dermatitis or the hidradenitis patient who hasn’t stop smoking for her cysts. It also helps to be nontransactional. If you make patients feel that you’re asking questions only to extract information, you’ll never reach Oprah level.

7. Be in the moment. It is difficult, but when possible, avoid typing notes while you’re still interviewing. We’re not just there to get the facts, we’re also trying to get the story and that sometimes takes really listening.

I’m no more like Oprah than Brady, of course. But it is more fun to close my eyes and imagine myself being her when I see my next patient. That is, until Thanksgiving. Watch out, Bedards from Attleboro.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In my last column, I explained how I’m like Tom Brady. I’m not really. Brady is a Super Bowl–winning quarterback worth over $200 million. No, I’m like Oprah. Well, trying anyway.

Brady and Oprah, in addition to being gazillionaires, have in common that they’re arguably the GOATs (Greatest Of All Time) in their fields. Watching Oprah interview Meghan Markle and Prince Harry was like watching Tom Brady on the jumbotron – she made it look easy. Her ability to create conversation and coax information from guests is hall-of-fame good. But although they are both admirable, trying to be like Brady is useful only for next Thanksgiving when you’re trying to beat your cousins from Massachusetts in touch football. .

1. Prepare ahead. It’s clear that Oprah has binders of notes about her guests and thoroughly reviewed them before she invites them to sit down. We should do the same. Open the chart and read as much as you can before you open the door. Have important information in your head so you don’t have to break from your interview to refer to it.

2. Sprinkle pleasantry. She’d never start an interview with: So why are you here? Nor should we. Even one nonscripted question or comment can help build a little rapport before getting to the work.

3. Be brief. Oprah gets her question out fast, then gets out of the way. And as a bonus, this is the easiest place to shave a few minutes from your appointments from your own end. Think for a second before you speak and try to find the shortest route to your question. Try to keep your questions to just a sentence or two.

4. Stay on it. Once you’ve discovered something relevant, stay with it, resisting the urge to finish the review of symptoms. This is not just to make a diagnosis, but as importantly, trying to diagnose “the real reason” for the visit. Then, when the question is done, own the transition. Oprah uses: “Let’s move on.” This is a bit abrupt for us, but it can be helpful if used sparingly and gently. I might soften this a little by adding “I want to be sure we have enough time to get through everything for you.”

5. Wait. A few seconds seems an eternity on the air (and in clinic), but sometimes the silent pause is just what’s needed to help the patient expand and share.

6. Be nonjudgmental. Most of us believe we’re pretty good at this, yet, it’s sometimes a blind spot. It’s easy to blame the obese patient for his stasis dermatitis or the hidradenitis patient who hasn’t stop smoking for her cysts. It also helps to be nontransactional. If you make patients feel that you’re asking questions only to extract information, you’ll never reach Oprah level.

7. Be in the moment. It is difficult, but when possible, avoid typing notes while you’re still interviewing. We’re not just there to get the facts, we’re also trying to get the story and that sometimes takes really listening.

I’m no more like Oprah than Brady, of course. But it is more fun to close my eyes and imagine myself being her when I see my next patient. That is, until Thanksgiving. Watch out, Bedards from Attleboro.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

School refusal and COVID-19: The pediatrician's role

Hooray for back to school! But not for everyone. ... what to do with those who have trouble transitioning back?

As we have now passed a year since COVID-19–related shutdowns were implemented throughout the United States; and with returns to in-person schooling continuing to vary based on location, many of us either in our personal lives, or through conversations with patients and families, are experiencing a yearning for the “good old days” of fully in-person schooling. As the place where children and adolescents spend a good portion of their waking hours, school is integral to not just children’s academic development, but to emotional and social development as well. One interesting phenomenon I’ve seen working with many children and families is that the strong desire to go back to school is not universal. Some of my patients are perfectly happy to be doing “remote schooling”, as it reduces the stress that they were experiencing in this setting before the pandemic.1 These families find themselves wondering – how will I get my child to return to school? As we (hopefully) turn the corner toward a return to normalcy, I believe many of us may find ourselves counseling families on whether a return to in-person schooling is in their child’s best interest. Even when a family decides it is best for their child to return, we might encounter scenarios in which children and adolescents outright refuse to go to school, or engage in avoidant behavior, which is broadly known as “school refusal.” Discussion of a treatment approach to this often challenging clinical scenario is warranted.

The first step in addressing the issue is defining it. School refusal is not a “diagnosis” in psychiatric lexicon, rather it describes a behavior which may be a symptom or manifestation of any number of underlying factors. One helpful definition proposed is (a) missing 25% of total school time for at least 2 weeks or (b) experiencing difficulty attending school such that there is significant interference in the child’s or family’s daily routine for at least 2 weeks, or (c) missing at least 10 days of school over a period of 15 weeks.2 The common thread of this, and any other definition, is sustained absenteeism or avoidance with significant impact to education, family life, or both. It is estimated that the prevalence of this phenomenon is between 1% and 2% of school-aged children.

Next to consider is what might be prompting or underlying the behavior. A comprehensive evaluation approach should include consideration of environmental factors such as bullying and learning difficulties, as well as presence of an anxiety or depressive disorder. Awareness of whether the child/adolescent has a 504 plan or individualized education program (IEP) is vital, as these can be marshaled for additional support. Family factors, including parental illness (medical and/or psychiatric), should also be considered. As school avoidance behaviors often include somatic symptoms of anxiety such as palpitations, shortness of breath, and abdominal pain; a rule out of medical etiology is recommended, as well as a caution to consider both medical and behavioral factors simultaneously, as focus on either separately can lead to missing the other.

Separation anxiety and social anxiety disorders are two specific conditions that may manifest in school refusal and should be evaluated for specifically. Separation anxiety is characterized by developmentally inappropriate, excessive worry or distress associated with separation from a primary caregiver or major attachment figure. Social anxiety is characterized by excessive fear or worry about being negatively evaluated by others in social situations.3 One publicly available tool that can be helpful for screening for a variety of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents is the SCARED.4 The PHQ-9 Adolescent5 is one such screening instrument for depression, which can be a driving factor or co-occur in children with school refusal.

When it comes to treatment, the best evidence out there is for a cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)–based approach motivated toward a return to the school setting as soon as possible.6,7 This will involve looking at how thoughts, behaviors, and feelings are interacting with each other in the clinical scenario and how these might be challenged or changed in a positive manner. Coping and problem-solving skills are often incorporated. This approach may also involve gradual exposure to the anxiety-producing situation in a hierarchical fashion starting with less anxiety-provoking scenarios and moving toward increasingly challenging ones. CBT for school refusal is likely most effective when including both school and family involvement to ensure consistency across settings. Making sure that there are not inadvertent reinforcing factors motivating staying home (for instance unrestricted access to electronic devices) is an important step to consider. If anxiety or depression is moderately to severely impairing – which is frequently the case when school refusal comes to clinical attention, consider use of medication as part of the treatment strategy. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a class are the most commonly used medications and deserve strong consideration.

To summarize, school refusal can occur for a variety of reasons. Early identification and comprehensive treatment taking into account child and family preference and using a multimodal approach to encourage and support a quick return to the school environment is considered best practice.

Dr. Hoffnung is a pediatric psychiatrist at the University of Vermont Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Robert Larner, M.D. College of Medicine at the University of Vermont, both in Burlington. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. See, for example: www.npr.org/2021/03/08/971457441/as-many-parents-fret-over-remote-learning-some-find-their-kids-are-thriving.

2. Kearney CA. Educ Psychol Rev. 2008;20:257-82.

3. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

4. Available at: www.pediatricbipolar.pitt.edu/resources/instruments.

5. Available at: www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/member_resources/toolbox_for_clinical_practice_and_outcomes/symptoms/GLAD-PC_PHQ-9.pdf.

6. Elliott JG and Place M. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(1):4-15.

7. Prabhuswamy M. J Paed Child Health. 2018;54(10):1117-20.

Hooray for back to school! But not for everyone. ... what to do with those who have trouble transitioning back?

As we have now passed a year since COVID-19–related shutdowns were implemented throughout the United States; and with returns to in-person schooling continuing to vary based on location, many of us either in our personal lives, or through conversations with patients and families, are experiencing a yearning for the “good old days” of fully in-person schooling. As the place where children and adolescents spend a good portion of their waking hours, school is integral to not just children’s academic development, but to emotional and social development as well. One interesting phenomenon I’ve seen working with many children and families is that the strong desire to go back to school is not universal. Some of my patients are perfectly happy to be doing “remote schooling”, as it reduces the stress that they were experiencing in this setting before the pandemic.1 These families find themselves wondering – how will I get my child to return to school? As we (hopefully) turn the corner toward a return to normalcy, I believe many of us may find ourselves counseling families on whether a return to in-person schooling is in their child’s best interest. Even when a family decides it is best for their child to return, we might encounter scenarios in which children and adolescents outright refuse to go to school, or engage in avoidant behavior, which is broadly known as “school refusal.” Discussion of a treatment approach to this often challenging clinical scenario is warranted.

The first step in addressing the issue is defining it. School refusal is not a “diagnosis” in psychiatric lexicon, rather it describes a behavior which may be a symptom or manifestation of any number of underlying factors. One helpful definition proposed is (a) missing 25% of total school time for at least 2 weeks or (b) experiencing difficulty attending school such that there is significant interference in the child’s or family’s daily routine for at least 2 weeks, or (c) missing at least 10 days of school over a period of 15 weeks.2 The common thread of this, and any other definition, is sustained absenteeism or avoidance with significant impact to education, family life, or both. It is estimated that the prevalence of this phenomenon is between 1% and 2% of school-aged children.

Next to consider is what might be prompting or underlying the behavior. A comprehensive evaluation approach should include consideration of environmental factors such as bullying and learning difficulties, as well as presence of an anxiety or depressive disorder. Awareness of whether the child/adolescent has a 504 plan or individualized education program (IEP) is vital, as these can be marshaled for additional support. Family factors, including parental illness (medical and/or psychiatric), should also be considered. As school avoidance behaviors often include somatic symptoms of anxiety such as palpitations, shortness of breath, and abdominal pain; a rule out of medical etiology is recommended, as well as a caution to consider both medical and behavioral factors simultaneously, as focus on either separately can lead to missing the other.

Separation anxiety and social anxiety disorders are two specific conditions that may manifest in school refusal and should be evaluated for specifically. Separation anxiety is characterized by developmentally inappropriate, excessive worry or distress associated with separation from a primary caregiver or major attachment figure. Social anxiety is characterized by excessive fear or worry about being negatively evaluated by others in social situations.3 One publicly available tool that can be helpful for screening for a variety of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents is the SCARED.4 The PHQ-9 Adolescent5 is one such screening instrument for depression, which can be a driving factor or co-occur in children with school refusal.

When it comes to treatment, the best evidence out there is for a cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)–based approach motivated toward a return to the school setting as soon as possible.6,7 This will involve looking at how thoughts, behaviors, and feelings are interacting with each other in the clinical scenario and how these might be challenged or changed in a positive manner. Coping and problem-solving skills are often incorporated. This approach may also involve gradual exposure to the anxiety-producing situation in a hierarchical fashion starting with less anxiety-provoking scenarios and moving toward increasingly challenging ones. CBT for school refusal is likely most effective when including both school and family involvement to ensure consistency across settings. Making sure that there are not inadvertent reinforcing factors motivating staying home (for instance unrestricted access to electronic devices) is an important step to consider. If anxiety or depression is moderately to severely impairing – which is frequently the case when school refusal comes to clinical attention, consider use of medication as part of the treatment strategy. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a class are the most commonly used medications and deserve strong consideration.

To summarize, school refusal can occur for a variety of reasons. Early identification and comprehensive treatment taking into account child and family preference and using a multimodal approach to encourage and support a quick return to the school environment is considered best practice.

Dr. Hoffnung is a pediatric psychiatrist at the University of Vermont Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Robert Larner, M.D. College of Medicine at the University of Vermont, both in Burlington. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. See, for example: www.npr.org/2021/03/08/971457441/as-many-parents-fret-over-remote-learning-some-find-their-kids-are-thriving.

2. Kearney CA. Educ Psychol Rev. 2008;20:257-82.

3. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

4. Available at: www.pediatricbipolar.pitt.edu/resources/instruments.

5. Available at: www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/member_resources/toolbox_for_clinical_practice_and_outcomes/symptoms/GLAD-PC_PHQ-9.pdf.

6. Elliott JG and Place M. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(1):4-15.

7. Prabhuswamy M. J Paed Child Health. 2018;54(10):1117-20.

Hooray for back to school! But not for everyone. ... what to do with those who have trouble transitioning back?

As we have now passed a year since COVID-19–related shutdowns were implemented throughout the United States; and with returns to in-person schooling continuing to vary based on location, many of us either in our personal lives, or through conversations with patients and families, are experiencing a yearning for the “good old days” of fully in-person schooling. As the place where children and adolescents spend a good portion of their waking hours, school is integral to not just children’s academic development, but to emotional and social development as well. One interesting phenomenon I’ve seen working with many children and families is that the strong desire to go back to school is not universal. Some of my patients are perfectly happy to be doing “remote schooling”, as it reduces the stress that they were experiencing in this setting before the pandemic.1 These families find themselves wondering – how will I get my child to return to school? As we (hopefully) turn the corner toward a return to normalcy, I believe many of us may find ourselves counseling families on whether a return to in-person schooling is in their child’s best interest. Even when a family decides it is best for their child to return, we might encounter scenarios in which children and adolescents outright refuse to go to school, or engage in avoidant behavior, which is broadly known as “school refusal.” Discussion of a treatment approach to this often challenging clinical scenario is warranted.

The first step in addressing the issue is defining it. School refusal is not a “diagnosis” in psychiatric lexicon, rather it describes a behavior which may be a symptom or manifestation of any number of underlying factors. One helpful definition proposed is (a) missing 25% of total school time for at least 2 weeks or (b) experiencing difficulty attending school such that there is significant interference in the child’s or family’s daily routine for at least 2 weeks, or (c) missing at least 10 days of school over a period of 15 weeks.2 The common thread of this, and any other definition, is sustained absenteeism or avoidance with significant impact to education, family life, or both. It is estimated that the prevalence of this phenomenon is between 1% and 2% of school-aged children.

Next to consider is what might be prompting or underlying the behavior. A comprehensive evaluation approach should include consideration of environmental factors such as bullying and learning difficulties, as well as presence of an anxiety or depressive disorder. Awareness of whether the child/adolescent has a 504 plan or individualized education program (IEP) is vital, as these can be marshaled for additional support. Family factors, including parental illness (medical and/or psychiatric), should also be considered. As school avoidance behaviors often include somatic symptoms of anxiety such as palpitations, shortness of breath, and abdominal pain; a rule out of medical etiology is recommended, as well as a caution to consider both medical and behavioral factors simultaneously, as focus on either separately can lead to missing the other.

Separation anxiety and social anxiety disorders are two specific conditions that may manifest in school refusal and should be evaluated for specifically. Separation anxiety is characterized by developmentally inappropriate, excessive worry or distress associated with separation from a primary caregiver or major attachment figure. Social anxiety is characterized by excessive fear or worry about being negatively evaluated by others in social situations.3 One publicly available tool that can be helpful for screening for a variety of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents is the SCARED.4 The PHQ-9 Adolescent5 is one such screening instrument for depression, which can be a driving factor or co-occur in children with school refusal.

When it comes to treatment, the best evidence out there is for a cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)–based approach motivated toward a return to the school setting as soon as possible.6,7 This will involve looking at how thoughts, behaviors, and feelings are interacting with each other in the clinical scenario and how these might be challenged or changed in a positive manner. Coping and problem-solving skills are often incorporated. This approach may also involve gradual exposure to the anxiety-producing situation in a hierarchical fashion starting with less anxiety-provoking scenarios and moving toward increasingly challenging ones. CBT for school refusal is likely most effective when including both school and family involvement to ensure consistency across settings. Making sure that there are not inadvertent reinforcing factors motivating staying home (for instance unrestricted access to electronic devices) is an important step to consider. If anxiety or depression is moderately to severely impairing – which is frequently the case when school refusal comes to clinical attention, consider use of medication as part of the treatment strategy. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a class are the most commonly used medications and deserve strong consideration.

To summarize, school refusal can occur for a variety of reasons. Early identification and comprehensive treatment taking into account child and family preference and using a multimodal approach to encourage and support a quick return to the school environment is considered best practice.

Dr. Hoffnung is a pediatric psychiatrist at the University of Vermont Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Robert Larner, M.D. College of Medicine at the University of Vermont, both in Burlington. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. See, for example: www.npr.org/2021/03/08/971457441/as-many-parents-fret-over-remote-learning-some-find-their-kids-are-thriving.

2. Kearney CA. Educ Psychol Rev. 2008;20:257-82.

3. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

4. Available at: www.pediatricbipolar.pitt.edu/resources/instruments.

5. Available at: www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/member_resources/toolbox_for_clinical_practice_and_outcomes/symptoms/GLAD-PC_PHQ-9.pdf.

6. Elliott JG and Place M. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(1):4-15.

7. Prabhuswamy M. J Paed Child Health. 2018;54(10):1117-20.

Office etiquette: Answering patient phone calls

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.

12. NEVER answer, “Doctor’s office, please hold.” To a patient, that is even worse than not answering at all. No matter how often your hold message tells callers how important they are, they know they are being ignored. Such encounters never end well: Those who wait will be grumpy and rude when you get back to them; those who hang up will be even more grumpy and rude when they call back. Worst of all are those who don’t call back and seek care elsewhere – often leaving a nasty comment on social media besides.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.

12. NEVER answer, “Doctor’s office, please hold.” To a patient, that is even worse than not answering at all. No matter how often your hold message tells callers how important they are, they know they are being ignored. Such encounters never end well: Those who wait will be grumpy and rude when you get back to them; those who hang up will be even more grumpy and rude when they call back. Worst of all are those who don’t call back and seek care elsewhere – often leaving a nasty comment on social media besides.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.

12. NEVER answer, “Doctor’s office, please hold.” To a patient, that is even worse than not answering at all. No matter how often your hold message tells callers how important they are, they know they are being ignored. Such encounters never end well: Those who wait will be grumpy and rude when you get back to them; those who hang up will be even more grumpy and rude when they call back. Worst of all are those who don’t call back and seek care elsewhere – often leaving a nasty comment on social media besides.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Virtual is the new real

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the transformation of Internet-based, remotely accessible innovative technologies. Internet-based customer service delivery technology was rapidly adopted and utilized by several services industries, but health care systems in most of the countries across the world faced unique challenges in adopting the technology for the delivery of health care services. The health care ecosystem of the United States was not immune to such challenges, and several significant barriers surfaced while the pandemic was underway.

Complexly structured, fragmented, unprepared, and overly burnt-out health systems in the United States arguably have fallen short of maximizing the value of telehealth in delivering safe, easily accessible, comprehensive, and cost-effective health care services. In this essay, we examine the reasons for such a suboptimal performance and discuss a few important strategies that may be useful in maximizing the value of telehealth value in several, appropriate health care services.

Hospitals and telehealth

Are hospitalists preparing ourselves “not to see” patients in a hospital-based health care delivery setting? If you have not yet started yet, now may be the right time! Yes, a certain percentage of doctor-patient encounters in hospital settings will remain virtual forever.

A well-established telehealth infrastructure is rarely found in most U.S. hospitals, although the COVID-19 pandemic has unexpectedly boosted the rapid growth of telehealth in the country.1 Public health emergency declarations in the United States in the face of the COVID-19 crisis have facilitated two important initiatives to restore health care delivery amidst formal and informal lockdowns that brought states to a grinding halt. These extend from expansion of virtual services, including telehealth, virtual check-ins, and e-visits, to the decision by the Department of Health & Human Services Office of Civil Rights to exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for the use of relatively inexpensive, non–public-facing mobile and other audiovisual technology tools.2

Hospital-based care in the United States taps nearly 33% of national health expenditure. An additional 30% of national health expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities is indirectly influenced by care delivered at health care facilities.3 Studies show that about 20% of ED visits could potentially be avoided via virtual urgent care offerings.4 A rapidly changing health care ecosystem is proving formidable for most hospital systems, and a test for their resilience and agility. Not just the implementation of telehealth is challenging, but getting it right is the key success factor.

Hospital-based telehealth

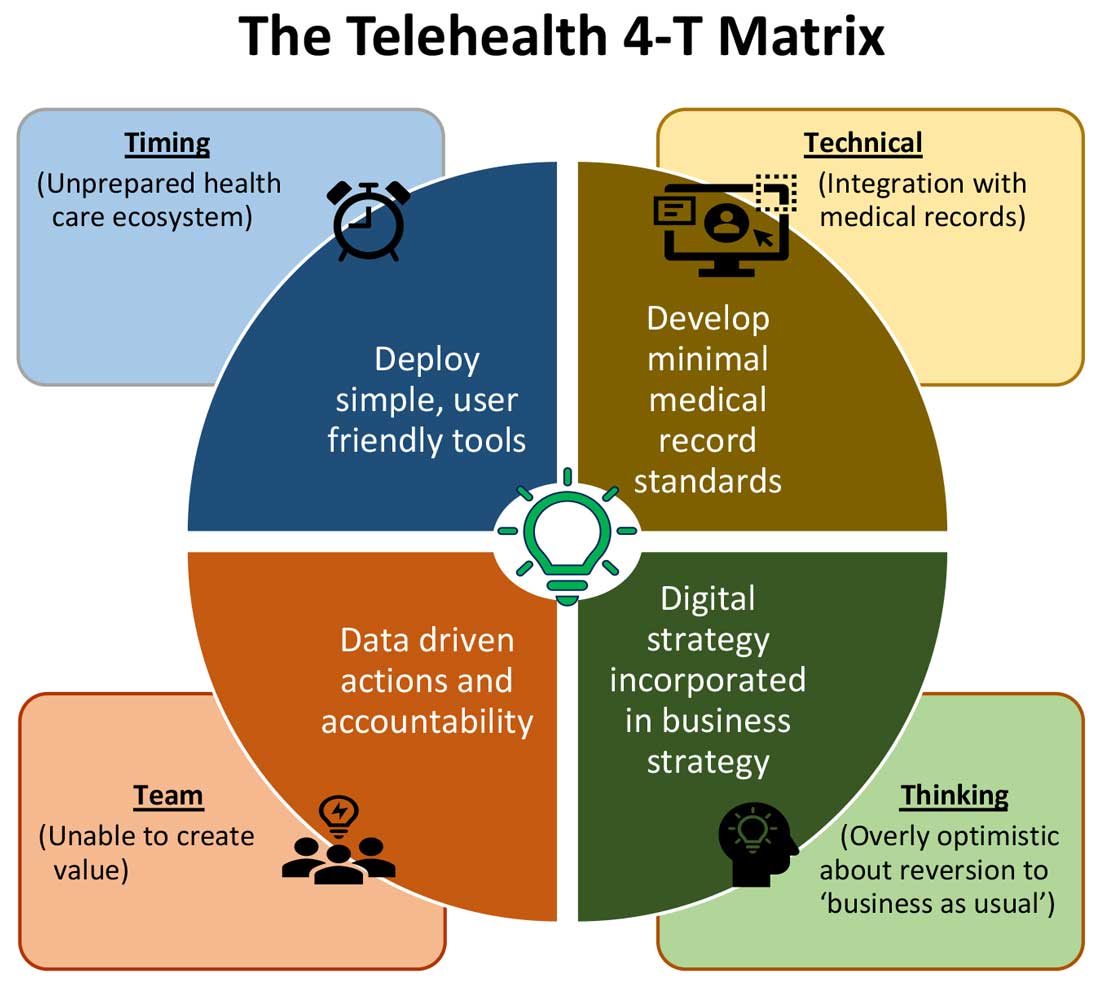

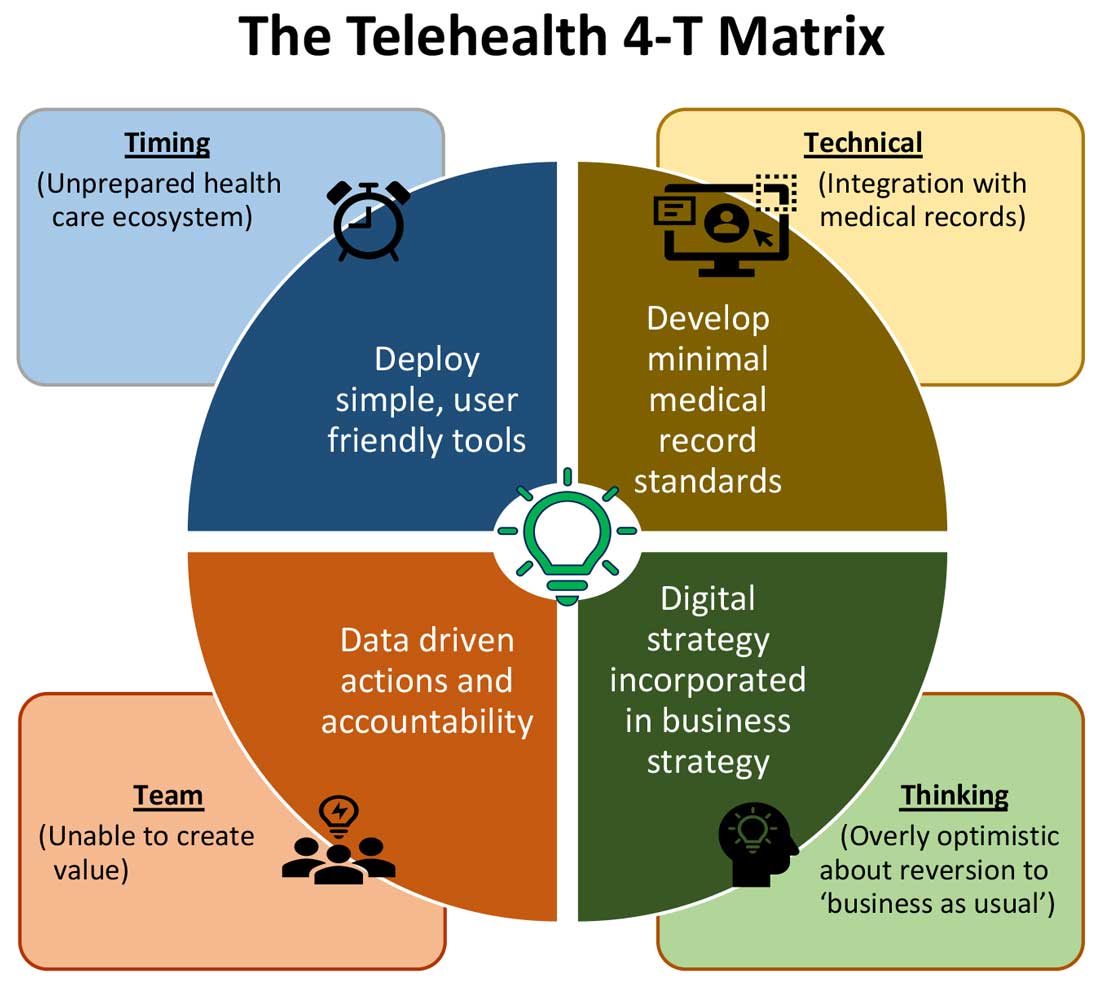

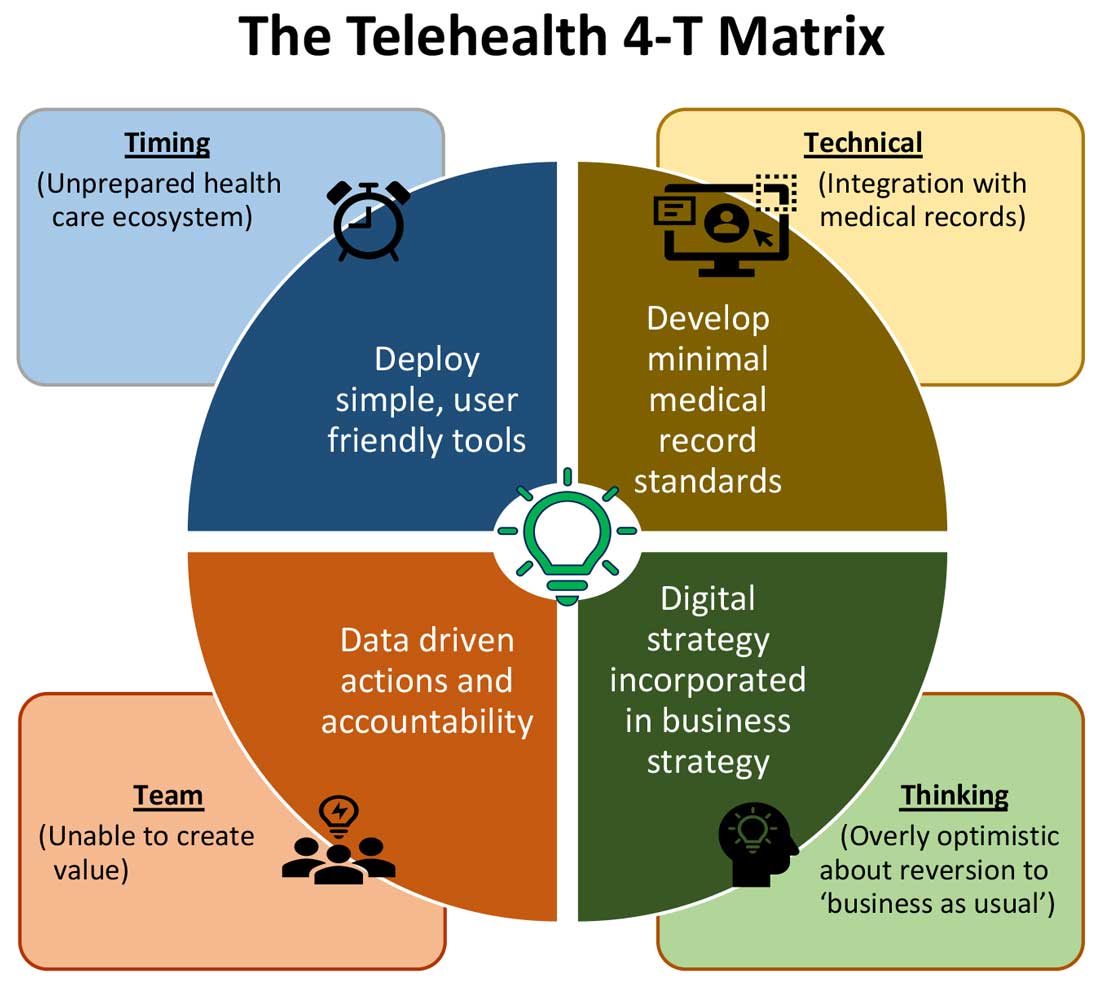

Expansion of telehealth coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and most commercial payers did not quite ride the pandemic-induced momentum across the care continuum. Hospitals are lagging far behind ambulatory care in implementing telehealth. As illustrated in the “4-T Matrix” (see graphic) we would like to examine four key reasons for such a sluggish initial uptake and try to propose four important strategies that may help us to maximize the value created by telehealth technologies.

1. Timing

The health care system has always lagged far behind other service industries in terms of technology adaptation. Because of the unique nature of health care services, face-to-face interaction supersedes all other forms of communication. A rapidly evolving pandemic was not matched by simultaneous technology education for patients and providers. The enormous choice of hard-to-navigate telehealth tools; time and labor-intensive implementation; and uncertainty around payer, policy, and regulatory expectations might have precluded providers from the rapid adoption of telehealth in the hospital setting. Patients’ specific characteristics, such as the absence of technology-centered education, information, age, comorbidities, lack of technical literacy, and dependency on caregivers contributed to the suboptimal response from patients and families.

Deploying simple, ubiquitous, user-friendly, and technologically less challenging telehealth solutions may be a better approach to increase the adoption of such solutions by providers and patients. Hospitals need to develop and distribute telehealth user guides in all possible modes of communication. Provider-centric in-service sessions, workshops, and live support by “superuser teams” often work well in reducing end-user resistance.

2. Technical

Current electronic medical records vary widely in their features and offerings, and their ability to interact with third-party software and platforms. Dissatisfaction of end users with EMRs is well known, as is their likely relationship to burnout. Recent research continues to show a strong relationship between EMR usability and the odds of burnout among physicians.5 In the current climate, administrators and health informaticists have the responsibility to avoid adding increased burdens to end users.

Another issue is the limited connectivity in many remote/rural areas that would impact implementation of telehealth platforms. Studies indicate that 33% of rural Americans lack access to high-speed broadband Internet to support video visits.6 The recent successful implementation of telehealth across 530 providers in 75 ambulatory practices operated by Munson Healthcare, a rural health system in northern Michigan, sheds light on the technology’s enormous potential in providing safe access to rural populations.6,7

Privacy and safety of patient data is of paramount importance. According to a national poll on healthy aging by the University of Michigan in May 2019, targeting older adults, 47% of survey responders expressed difficulty using technology and 49% of survey responders were concerned about privacy.8 Use of certification and other tools offered by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology would help reassure users, and the ability to capture and share images between providers would be of immense benefit in facilitating e-consults.

The need of the hour is redesigned work flow, to help providers adopt and use virtual care/telehealth efficiently. Work flow redesign must be coupled with technological advances to allow seamless integration of third-party telehealth platforms into existing EMR systems or built directly into EMRs. Use of quality metrics and analytical tools specific to telehealth would help measure the technology’s impact on patient care, outcomes, and end-user/provider experience.

3. Teams and training

Outcomes of health care interventions are often determined by the effectiveness of teams. Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and patients to a breaking point.5 Decentralized, uncoordinated, and siloed efforts by individual teams across the care continuum were contributing factors for the partial success of telehealth care delivery pathways. The hospital systems with telehealth-ready teams at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were so rare that the knowledge and technical training opportunities for innovators grew severalfold during the pandemic.

As per the American Medical Association, telehealth success is massively dependent on building the right team. Core, leadership, advisory, and implementation teams comprised of clinical representatives, end users, administrative personnel, executive members of the organization, technical experts, and payment/policy experts should be put together before implementing a telehealth strategy.9 Seamless integration of hospital-based care with ambulatory care via a telehealth platform is only complete when care managers are trained and deployed to fulfill the needs of a diverse group of patients. Deriving overall value from telehealth is only possible when there is a skill development, training and mentoring team put in place.

4. Thinking

In most U.S. hospitals, inpatient health care is equally distributed between nonprocedure and procedure-based services. Hospitals resorted to suspension of nonemergent procedures to mitigate the risk of spreading COVID-19. This was further compounded by many patients’ self-selection to defer care, an abrupt reduction in the influx of patients from the referral base because of suboptimally operating ambulatory care services, leading to low hospital occupancy.

Hospitals across the nation have gone through a massive short-term financial crunch and unfavorable cash-flow forecast, which prompted a paradoxical work-force reduction. While some argue that it may be akin to strategic myopia, the authors believed that such a response is strategically imperative to keep the hospital afloat. It is reasonable to attribute the paucity of innovation to constrained resources, and health systems are simply staying overly optimistic about “weathering the storm” and reverting soon to “business as usual.” The technological framework necessary for deploying a telehealth solution often comes with a price. Financially challenged hospital systems rarely exercise any capital-intensive activities. By contrast, telehealth adoption by ambulatory care can result in quicker resumption of patient care in community settings. A lack of operational and infrastructure synchrony between ambulatory and in-hospital systems has failed to capture telehealth-driven inpatient volume. For example, direct admissions from ambulatory telehealth referrals was a missed opportunity in several places. Referrals for labs, diagnostic tests, and other allied services could have helped hospitals offset their fixed costs. Similarly, work flows related to discharge and postdischarge follow up rarely embrace telehealth tools or telehealth care pathways. A brisk change in the health care ecosystem is partly responsible for this.

Digital strategy needs to be incorporated into business strategy. For the reasons already discussed, telehealth technology is not a “nice to have” anymore, but a “must have.” At present, providers are of the opinion that about 20% of their patient services can be delivered via a telehealth platform. Similar trends are observed among patients, as a new modality of access to care is increasingly beneficial to them. Telehealth must be incorporated in standardized hospital work flows. Use of telehealth for preoperative clearance will greatly minimize same-day surgery cancellations. Given the potential shortage in resources, telehealth adoption for inpatient consultations will help systems conserve personal protective equipment, minimize the risk of staff exposure to COVID-19, and improve efficiency.

Digital strategy also prompts the reengineering of care delivery.10 Excessive and unused physical capacity can be converted into digital care hubs. Health maintenance, prevention, health promotion, health education, and chronic disease management not only can serve a variety of patient groups but can also help address the “last-mile problem” in health care. A successful digital strategy usually has three important components – Commitment: Hospital leadership is committed to include digital transformation as a strategic objective; Cost: Digital strategy is added as a line item in the budget; and Control: Measurable metrics are put in place to monitor the performance, impact, and influence of the digital strategy.

Conclusion

For decades, most U.S. health systems occupied the periphery of technological transformation when compared to the rest of the service industry. While most health systems took a heroic approach to the adoption of telehealth during COVID-19, despite being unprepared, the need for a systematic telehealth deployment is far from being adequately fulfilled. The COVID-19 pandemic brought permanent changes to several business disciplines globally. Given the impact of the pandemic on the health and overall wellbeing of American society, the U.S. health care industry must leave no stone unturned in its quest for transformation.

Dr. Lingisetty is a hospitalist and physician executive at Baptist Health System, Little Rock, Ark, and is cofounder/president of SHM’s Arkansas chapter. Dr. Prasad is medical director of care management and a hospitalist at Advocate Aurora Health in Milwaukee. He is cochair of SHM’s IT Special Interest Group, sits on the HQPS committee, and is president of SHM’s Wisconsin chapter. Dr. Palabindala is the medical director, utilization management, and physician advisory services at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and an associate professor of medicine and academic hospitalist at the University of Mississippi, both in Jackson.

References

1. Finnegan M. “Telehealth booms amid COVID-19 crisis.” Computerworld. 2020 Apr 27. www.computerworld.com/article/3540315/telehealth-booms-amid-covid-19-crisis-virtual-care-is-here-to-stay.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

2. Department of Health & Human Services. “OCR Announces Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency.” 2020 Mar 17. www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/03/17/ocr-announces-notification-of-enforcement-discretion-for-telehealth-remote-communications-during-the-covid-19.html. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

3. National Center for Health Statistics. “Health Expenditures.” www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

4. Bestsennyy O et al. “Telehealth: A post–COVID-19 reality?” McKinsey & Company. 2020 May 29. www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality. Accessed 2020 Sep 12.

5. Melnick ER et al. The Association Between Perceived Electronic Health Record Usability and Professional Burnout Among U.S. Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020 March;95(3):476-87.

6. Hirko KA et al. Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Nov;27(11):1816-8. .

7. American Academy of Family Physicians. “Study Examines Telehealth, Rural Disparities in Pandemic.” 2020 July 30. www.aafp.org/news/practice-professional-issues/20200730ruraltelehealth.html. Accessed 2020 Dec 15.

8. Kurlander J et al. “Virtual Visits: Telehealth and Older Adults.” National Poll on Healthy Aging. 2019 Oct. hdl.handle.net/2027.42/151376.

9. American Medical Association. Telehealth Implementation Playbook. 2019. www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-04/ama-telehealth-implementation-playbook.pdf.

10. Smith AC et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare. 2020 Jun;26(5):309-13.

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

Why did we fall short on maximizing telehealth’s value in the COVID-19 pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the transformation of Internet-based, remotely accessible innovative technologies. Internet-based customer service delivery technology was rapidly adopted and utilized by several services industries, but health care systems in most of the countries across the world faced unique challenges in adopting the technology for the delivery of health care services. The health care ecosystem of the United States was not immune to such challenges, and several significant barriers surfaced while the pandemic was underway.

Complexly structured, fragmented, unprepared, and overly burnt-out health systems in the United States arguably have fallen short of maximizing the value of telehealth in delivering safe, easily accessible, comprehensive, and cost-effective health care services. In this essay, we examine the reasons for such a suboptimal performance and discuss a few important strategies that may be useful in maximizing the value of telehealth value in several, appropriate health care services.

Hospitals and telehealth

Are hospitalists preparing ourselves “not to see” patients in a hospital-based health care delivery setting? If you have not yet started yet, now may be the right time! Yes, a certain percentage of doctor-patient encounters in hospital settings will remain virtual forever.

A well-established telehealth infrastructure is rarely found in most U.S. hospitals, although the COVID-19 pandemic has unexpectedly boosted the rapid growth of telehealth in the country.1 Public health emergency declarations in the United States in the face of the COVID-19 crisis have facilitated two important initiatives to restore health care delivery amidst formal and informal lockdowns that brought states to a grinding halt. These extend from expansion of virtual services, including telehealth, virtual check-ins, and e-visits, to the decision by the Department of Health & Human Services Office of Civil Rights to exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for the use of relatively inexpensive, non–public-facing mobile and other audiovisual technology tools.2

Hospital-based care in the United States taps nearly 33% of national health expenditure. An additional 30% of national health expenditure that is related to physicians, prescriptions, and other facilities is indirectly influenced by care delivered at health care facilities.3 Studies show that about 20% of ED visits could potentially be avoided via virtual urgent care offerings.4 A rapidly changing health care ecosystem is proving formidable for most hospital systems, and a test for their resilience and agility. Not just the implementation of telehealth is challenging, but getting it right is the key success factor.

Hospital-based telehealth

Expansion of telehealth coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and most commercial payers did not quite ride the pandemic-induced momentum across the care continuum. Hospitals are lagging far behind ambulatory care in implementing telehealth. As illustrated in the “4-T Matrix” (see graphic) we would like to examine four key reasons for such a sluggish initial uptake and try to propose four important strategies that may help us to maximize the value created by telehealth technologies.

1. Timing

The health care system has always lagged far behind other service industries in terms of technology adaptation. Because of the unique nature of health care services, face-to-face interaction supersedes all other forms of communication. A rapidly evolving pandemic was not matched by simultaneous technology education for patients and providers. The enormous choice of hard-to-navigate telehealth tools; time and labor-intensive implementation; and uncertainty around payer, policy, and regulatory expectations might have precluded providers from the rapid adoption of telehealth in the hospital setting. Patients’ specific characteristics, such as the absence of technology-centered education, information, age, comorbidities, lack of technical literacy, and dependency on caregivers contributed to the suboptimal response from patients and families.

Deploying simple, ubiquitous, user-friendly, and technologically less challenging telehealth solutions may be a better approach to increase the adoption of such solutions by providers and patients. Hospitals need to develop and distribute telehealth user guides in all possible modes of communication. Provider-centric in-service sessions, workshops, and live support by “superuser teams” often work well in reducing end-user resistance.

2. Technical

Current electronic medical records vary widely in their features and offerings, and their ability to interact with third-party software and platforms. Dissatisfaction of end users with EMRs is well known, as is their likely relationship to burnout. Recent research continues to show a strong relationship between EMR usability and the odds of burnout among physicians.5 In the current climate, administrators and health informaticists have the responsibility to avoid adding increased burdens to end users.

Another issue is the limited connectivity in many remote/rural areas that would impact implementation of telehealth platforms. Studies indicate that 33% of rural Americans lack access to high-speed broadband Internet to support video visits.6 The recent successful implementation of telehealth across 530 providers in 75 ambulatory practices operated by Munson Healthcare, a rural health system in northern Michigan, sheds light on the technology’s enormous potential in providing safe access to rural populations.6,7

Privacy and safety of patient data is of paramount importance. According to a national poll on healthy aging by the University of Michigan in May 2019, targeting older adults, 47% of survey responders expressed difficulty using technology and 49% of survey responders were concerned about privacy.8 Use of certification and other tools offered by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology would help reassure users, and the ability to capture and share images between providers would be of immense benefit in facilitating e-consults.

The need of the hour is redesigned work flow, to help providers adopt and use virtual care/telehealth efficiently. Work flow redesign must be coupled with technological advances to allow seamless integration of third-party telehealth platforms into existing EMR systems or built directly into EMRs. Use of quality metrics and analytical tools specific to telehealth would help measure the technology’s impact on patient care, outcomes, and end-user/provider experience.

3. Teams and training

Outcomes of health care interventions are often determined by the effectiveness of teams. Irrespective of how robust health care systems may have been initially, rapidly spreading infectious diseases like COVID-19 can quickly derail the system, bringing the workforce and patients to a breaking point.5 Decentralized, uncoordinated, and siloed efforts by individual teams across the care continuum were contributing factors for the partial success of telehealth care delivery pathways. The hospital systems with telehealth-ready teams at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were so rare that the knowledge and technical training opportunities for innovators grew severalfold during the pandemic.

As per the American Medical Association, telehealth success is massively dependent on building the right team. Core, leadership, advisory, and implementation teams comprised of clinical representatives, end users, administrative personnel, executive members of the organization, technical experts, and payment/policy experts should be put together before implementing a telehealth strategy.9 Seamless integration of hospital-based care with ambulatory care via a telehealth platform is only complete when care managers are trained and deployed to fulfill the needs of a diverse group of patients. Deriving overall value from telehealth is only possible when there is a skill development, training and mentoring team put in place.

4. Thinking