User login

More U.S. states cap insulin cost, but activists will ‘fight harder’

Twelve U.S. states have now passed laws aimed at making insulin more affordable – and more than 30 are considering such legislation – but they all have gaps that still put the cost of this basic and essential medication out of reach for many with diabetes.

The laws only apply to health insurance through state-regulated plans, and not to the majority of health plans that cover most Americans: Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs health system, or self-funded employer-sponsored plans.

Overall, Hannah Crabtree, an activist who writes the blog Data for Insulin, estimates state laws that limit copays, deductibles, or other out-of-pocket costs for insulin cover an average of 27% of people with diabetes across the United States.

And while diabetes activists have applauded state actions, most want more help for the under- and uninsured.

“Our chapter will be fighting harder next legislative session for the uninsured,” said Mindie Hooley, the leader of the Utah #insulin4all chapter, which successfully lobbied legislators to pass a bill signed by the state’s governor on March 30.

“With so many losing their jobs because of the pandemic, there’s no better time than now to fight for these patients who don’t have insurance,” Ms. Hooley said in an interview.

The American Diabetes Association has also been lobbying for state caps as one of many avenues for making insulin more affordable, said Stephen Habbe, the ADA’s director for state government affairs.

One in four insulin users report rationing the medication, Mr. Habbe said.

The state laws “can really provide important relief in terms of affordability for their insulin costs, which we know can be critical in terms of preserving their life and helping to prevent complications that can potentially be disabling or even deadly,” he said in an interview.

Activists with T1 International, which created the #insulin4all campaign, are working nationwide to convince state legislators to back measures that limit out-of-pocket costs for insulin, or for other diabetes medications and supplies.

Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Utah, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia have enacted such limits, with caps ranging from $25 to $100.

Insulin makers unfazed, blame insurers, PBMs for high prices

The three insulin manufacturers in the United States – Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi– have not overtly fought against the laws, although in July, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America did sue to block a related Minnesota law that provides a free emergency supply of insulin.

And the nonprofit news organization FairWarning reported in August that a lobbyist from Eli Lilly had attempted to push a Tennessee legislator to keep the uninsured from being eligible for any out-of-pocket limits.

The insulin makers have also not lowered prices in response to the mounting number of state laws.

They see no need, said Tara O’Neill Hayes, director of human welfare policy at the American Action Forum, a center right–leaning Washington, D.C., think tank.

“You’re going to do what you can get away with,” Ms. O’Neill Hayes said in an interview. “To the extent that they can keep their prices high and people are still buying, they have limited incentives to lower those costs.”

The insulin market is dysfunctional, she added. “The increasing cost of insulin seems primarily to be the result of a lack of competition in the market and convoluted drug pricing and insurance practices,” Ms. O’Neill Hayes and colleagues wrote in a report in April on federal and state attempts to address insulin affordability.

Novo Nordisk, however, maintains that drugmakers are not solely to blame.

“Everyone in the health care system has a role to play in affordability,” said Ken Inchausti, Novo Nordisk’s senior director for corporate communications. State legislation “attempts to address a systemic issue in [U.S.] health care: How benefit design can make medicines unaffordable for many, especially for those in high-deductible health plans,” he said in an interview.

“Efforts to place copay caps on insurance plans covering insulin can certainly help lower out-of-pocket costs,” said Mr. Inchausti.

Sanofi spokesperson Jon Florio said the company supports actions that increase affordable access to insulin. However, “while we support capped copays, we feel this should not be limited to just one class of medicines,” he said. Mr. Florio also noted that Sanofi provides out-of-pocket caps to anyone with commercial insurance and that anyone without insurance can buy one or multiple Sanofi insulins for a fixed price of $99 per month, up to 10 boxes of pens and/or 10-mL vials.

And Sanofi will take part in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ new insulin demonstration program. Starting in 2021, CMS will cap insulin copays at $35 for people in Part D plans that participate.

Eli Lilly spokesperson Brad Jacklin said the company “believes in the common goal of ensuring affordable access to insulin and other life-saving medicines because nobody should have to forgo or ration because of cost.”

Lilly supports efforts “that more directly affect patients’ cost-sharing based on their health care coverage,” he said. Insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should pass savings on to patients, Mr. Jacklin urged. Lilly caps some insulins at $35 for the uninsured or commercially insured. The company will also participate in the CMS program.

Meanwhile, a PhRMA-sponsored website www.letstalkaboutcost.org said that, because they do not share savings, insurers and PBMs are responsible for high insulin costs.

Manufacturer assistance programs for patients with diabetes and other chronic diseases, on the other hand, can save individuals $300-$500 a year, PhRMA said in August.

PBMs point back at insulin manufacturers

PBMs, however, point back at drug companies. “PBMs have been able to moderate insulin costs for most consumers with insurance,” said J.C. Scott, president and CEO of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the PBM trade group, in a statement.

The rising cost of insulin is caused by a lack of competition and overuse of patent extensions, PCMA maintains.

Health insurers, which, in tandem with PBMs, give insulins formulary preference based on a discounted price, are most likely to feel the impact of laws limiting out-of-pocket costs.

If they have to make up the shortfall from a patient’s reduced payment for a prescription, they will likely raise premiums, said Ms. O’Neill Hayes.

And if patients pay the same price for insulin – regardless of who makes it – drugmakers won’t have much incentive to offer discounts or rebates for formulary placement, she said. Again, that would likely lead to higher premiums.

David Allen, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, said in an interview that AHIP believes lack of competition has driven up insulin prices.

“High prices for insulin correspond with high health insurance costs for insulin,” he said. When CMS starts requiring drugmakers to discount their insulins for Medicare that will allow “health plans to use those savings to reduce out-of-pocket [costs] for seniors.”

He did not respond to a question as to why health insurers were not already passing savings on to commercially insured patients, especially in states with out-of-pocket limits.

Mr. Allen did say that AHIP’s plans “stand ready to work with state policymakers to remove barriers to lower insulin prices for Americans.”

Utah savings hopefully saving lives already

In Utah, legislators tuned out the blame game, and instead were keen to listen to patients, who had many stories about how the high cost of insulin had hurt them, said Ms. Hooley.

She noted an estimated 50,000 Utahans rely on insulin to stay alive.

Ms. Hooley and her chapter convinced legislators to pass a bill that gives insurers the option to cap patient copays at $30 per month, or to put insulin on its lowest formulary tier and waive any patient deductible. That aspect of the law does not go into effect until January 2021, but insurers are already starting to move insulin to the lowest formulary tier.

That has helped some people immediately. One state resident said her most recent insulin prescription cost $7 – instead of the usual $200.

The uninsured are not left totally high and dry either. Starting June 1, anyone in the state could buy through a state bulk-purchasing program, which guaranteed a 60% discount.

Ms. Hooley said she’d recently heard about a patient who usually spent $300 per prescription but was able to buy insulin for $100 through the program.

“Although $100 is still too much, it is nice knowing the Utah Insulin Savings Program is saving lives,” Ms. Hooley concluded.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Twelve U.S. states have now passed laws aimed at making insulin more affordable – and more than 30 are considering such legislation – but they all have gaps that still put the cost of this basic and essential medication out of reach for many with diabetes.

The laws only apply to health insurance through state-regulated plans, and not to the majority of health plans that cover most Americans: Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs health system, or self-funded employer-sponsored plans.

Overall, Hannah Crabtree, an activist who writes the blog Data for Insulin, estimates state laws that limit copays, deductibles, or other out-of-pocket costs for insulin cover an average of 27% of people with diabetes across the United States.

And while diabetes activists have applauded state actions, most want more help for the under- and uninsured.

“Our chapter will be fighting harder next legislative session for the uninsured,” said Mindie Hooley, the leader of the Utah #insulin4all chapter, which successfully lobbied legislators to pass a bill signed by the state’s governor on March 30.

“With so many losing their jobs because of the pandemic, there’s no better time than now to fight for these patients who don’t have insurance,” Ms. Hooley said in an interview.

The American Diabetes Association has also been lobbying for state caps as one of many avenues for making insulin more affordable, said Stephen Habbe, the ADA’s director for state government affairs.

One in four insulin users report rationing the medication, Mr. Habbe said.

The state laws “can really provide important relief in terms of affordability for their insulin costs, which we know can be critical in terms of preserving their life and helping to prevent complications that can potentially be disabling or even deadly,” he said in an interview.

Activists with T1 International, which created the #insulin4all campaign, are working nationwide to convince state legislators to back measures that limit out-of-pocket costs for insulin, or for other diabetes medications and supplies.

Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Utah, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia have enacted such limits, with caps ranging from $25 to $100.

Insulin makers unfazed, blame insurers, PBMs for high prices

The three insulin manufacturers in the United States – Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi– have not overtly fought against the laws, although in July, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America did sue to block a related Minnesota law that provides a free emergency supply of insulin.

And the nonprofit news organization FairWarning reported in August that a lobbyist from Eli Lilly had attempted to push a Tennessee legislator to keep the uninsured from being eligible for any out-of-pocket limits.

The insulin makers have also not lowered prices in response to the mounting number of state laws.

They see no need, said Tara O’Neill Hayes, director of human welfare policy at the American Action Forum, a center right–leaning Washington, D.C., think tank.

“You’re going to do what you can get away with,” Ms. O’Neill Hayes said in an interview. “To the extent that they can keep their prices high and people are still buying, they have limited incentives to lower those costs.”

The insulin market is dysfunctional, she added. “The increasing cost of insulin seems primarily to be the result of a lack of competition in the market and convoluted drug pricing and insurance practices,” Ms. O’Neill Hayes and colleagues wrote in a report in April on federal and state attempts to address insulin affordability.

Novo Nordisk, however, maintains that drugmakers are not solely to blame.

“Everyone in the health care system has a role to play in affordability,” said Ken Inchausti, Novo Nordisk’s senior director for corporate communications. State legislation “attempts to address a systemic issue in [U.S.] health care: How benefit design can make medicines unaffordable for many, especially for those in high-deductible health plans,” he said in an interview.

“Efforts to place copay caps on insurance plans covering insulin can certainly help lower out-of-pocket costs,” said Mr. Inchausti.

Sanofi spokesperson Jon Florio said the company supports actions that increase affordable access to insulin. However, “while we support capped copays, we feel this should not be limited to just one class of medicines,” he said. Mr. Florio also noted that Sanofi provides out-of-pocket caps to anyone with commercial insurance and that anyone without insurance can buy one or multiple Sanofi insulins for a fixed price of $99 per month, up to 10 boxes of pens and/or 10-mL vials.

And Sanofi will take part in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ new insulin demonstration program. Starting in 2021, CMS will cap insulin copays at $35 for people in Part D plans that participate.

Eli Lilly spokesperson Brad Jacklin said the company “believes in the common goal of ensuring affordable access to insulin and other life-saving medicines because nobody should have to forgo or ration because of cost.”

Lilly supports efforts “that more directly affect patients’ cost-sharing based on their health care coverage,” he said. Insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should pass savings on to patients, Mr. Jacklin urged. Lilly caps some insulins at $35 for the uninsured or commercially insured. The company will also participate in the CMS program.

Meanwhile, a PhRMA-sponsored website www.letstalkaboutcost.org said that, because they do not share savings, insurers and PBMs are responsible for high insulin costs.

Manufacturer assistance programs for patients with diabetes and other chronic diseases, on the other hand, can save individuals $300-$500 a year, PhRMA said in August.

PBMs point back at insulin manufacturers

PBMs, however, point back at drug companies. “PBMs have been able to moderate insulin costs for most consumers with insurance,” said J.C. Scott, president and CEO of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the PBM trade group, in a statement.

The rising cost of insulin is caused by a lack of competition and overuse of patent extensions, PCMA maintains.

Health insurers, which, in tandem with PBMs, give insulins formulary preference based on a discounted price, are most likely to feel the impact of laws limiting out-of-pocket costs.

If they have to make up the shortfall from a patient’s reduced payment for a prescription, they will likely raise premiums, said Ms. O’Neill Hayes.

And if patients pay the same price for insulin – regardless of who makes it – drugmakers won’t have much incentive to offer discounts or rebates for formulary placement, she said. Again, that would likely lead to higher premiums.

David Allen, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, said in an interview that AHIP believes lack of competition has driven up insulin prices.

“High prices for insulin correspond with high health insurance costs for insulin,” he said. When CMS starts requiring drugmakers to discount their insulins for Medicare that will allow “health plans to use those savings to reduce out-of-pocket [costs] for seniors.”

He did not respond to a question as to why health insurers were not already passing savings on to commercially insured patients, especially in states with out-of-pocket limits.

Mr. Allen did say that AHIP’s plans “stand ready to work with state policymakers to remove barriers to lower insulin prices for Americans.”

Utah savings hopefully saving lives already

In Utah, legislators tuned out the blame game, and instead were keen to listen to patients, who had many stories about how the high cost of insulin had hurt them, said Ms. Hooley.

She noted an estimated 50,000 Utahans rely on insulin to stay alive.

Ms. Hooley and her chapter convinced legislators to pass a bill that gives insurers the option to cap patient copays at $30 per month, or to put insulin on its lowest formulary tier and waive any patient deductible. That aspect of the law does not go into effect until January 2021, but insurers are already starting to move insulin to the lowest formulary tier.

That has helped some people immediately. One state resident said her most recent insulin prescription cost $7 – instead of the usual $200.

The uninsured are not left totally high and dry either. Starting June 1, anyone in the state could buy through a state bulk-purchasing program, which guaranteed a 60% discount.

Ms. Hooley said she’d recently heard about a patient who usually spent $300 per prescription but was able to buy insulin for $100 through the program.

“Although $100 is still too much, it is nice knowing the Utah Insulin Savings Program is saving lives,” Ms. Hooley concluded.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Twelve U.S. states have now passed laws aimed at making insulin more affordable – and more than 30 are considering such legislation – but they all have gaps that still put the cost of this basic and essential medication out of reach for many with diabetes.

The laws only apply to health insurance through state-regulated plans, and not to the majority of health plans that cover most Americans: Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs health system, or self-funded employer-sponsored plans.

Overall, Hannah Crabtree, an activist who writes the blog Data for Insulin, estimates state laws that limit copays, deductibles, or other out-of-pocket costs for insulin cover an average of 27% of people with diabetes across the United States.

And while diabetes activists have applauded state actions, most want more help for the under- and uninsured.

“Our chapter will be fighting harder next legislative session for the uninsured,” said Mindie Hooley, the leader of the Utah #insulin4all chapter, which successfully lobbied legislators to pass a bill signed by the state’s governor on March 30.

“With so many losing their jobs because of the pandemic, there’s no better time than now to fight for these patients who don’t have insurance,” Ms. Hooley said in an interview.

The American Diabetes Association has also been lobbying for state caps as one of many avenues for making insulin more affordable, said Stephen Habbe, the ADA’s director for state government affairs.

One in four insulin users report rationing the medication, Mr. Habbe said.

The state laws “can really provide important relief in terms of affordability for their insulin costs, which we know can be critical in terms of preserving their life and helping to prevent complications that can potentially be disabling or even deadly,” he said in an interview.

Activists with T1 International, which created the #insulin4all campaign, are working nationwide to convince state legislators to back measures that limit out-of-pocket costs for insulin, or for other diabetes medications and supplies.

Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Utah, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia have enacted such limits, with caps ranging from $25 to $100.

Insulin makers unfazed, blame insurers, PBMs for high prices

The three insulin manufacturers in the United States – Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi– have not overtly fought against the laws, although in July, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America did sue to block a related Minnesota law that provides a free emergency supply of insulin.

And the nonprofit news organization FairWarning reported in August that a lobbyist from Eli Lilly had attempted to push a Tennessee legislator to keep the uninsured from being eligible for any out-of-pocket limits.

The insulin makers have also not lowered prices in response to the mounting number of state laws.

They see no need, said Tara O’Neill Hayes, director of human welfare policy at the American Action Forum, a center right–leaning Washington, D.C., think tank.

“You’re going to do what you can get away with,” Ms. O’Neill Hayes said in an interview. “To the extent that they can keep their prices high and people are still buying, they have limited incentives to lower those costs.”

The insulin market is dysfunctional, she added. “The increasing cost of insulin seems primarily to be the result of a lack of competition in the market and convoluted drug pricing and insurance practices,” Ms. O’Neill Hayes and colleagues wrote in a report in April on federal and state attempts to address insulin affordability.

Novo Nordisk, however, maintains that drugmakers are not solely to blame.

“Everyone in the health care system has a role to play in affordability,” said Ken Inchausti, Novo Nordisk’s senior director for corporate communications. State legislation “attempts to address a systemic issue in [U.S.] health care: How benefit design can make medicines unaffordable for many, especially for those in high-deductible health plans,” he said in an interview.

“Efforts to place copay caps on insurance plans covering insulin can certainly help lower out-of-pocket costs,” said Mr. Inchausti.

Sanofi spokesperson Jon Florio said the company supports actions that increase affordable access to insulin. However, “while we support capped copays, we feel this should not be limited to just one class of medicines,” he said. Mr. Florio also noted that Sanofi provides out-of-pocket caps to anyone with commercial insurance and that anyone without insurance can buy one or multiple Sanofi insulins for a fixed price of $99 per month, up to 10 boxes of pens and/or 10-mL vials.

And Sanofi will take part in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ new insulin demonstration program. Starting in 2021, CMS will cap insulin copays at $35 for people in Part D plans that participate.

Eli Lilly spokesperson Brad Jacklin said the company “believes in the common goal of ensuring affordable access to insulin and other life-saving medicines because nobody should have to forgo or ration because of cost.”

Lilly supports efforts “that more directly affect patients’ cost-sharing based on their health care coverage,” he said. Insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should pass savings on to patients, Mr. Jacklin urged. Lilly caps some insulins at $35 for the uninsured or commercially insured. The company will also participate in the CMS program.

Meanwhile, a PhRMA-sponsored website www.letstalkaboutcost.org said that, because they do not share savings, insurers and PBMs are responsible for high insulin costs.

Manufacturer assistance programs for patients with diabetes and other chronic diseases, on the other hand, can save individuals $300-$500 a year, PhRMA said in August.

PBMs point back at insulin manufacturers

PBMs, however, point back at drug companies. “PBMs have been able to moderate insulin costs for most consumers with insurance,” said J.C. Scott, president and CEO of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the PBM trade group, in a statement.

The rising cost of insulin is caused by a lack of competition and overuse of patent extensions, PCMA maintains.

Health insurers, which, in tandem with PBMs, give insulins formulary preference based on a discounted price, are most likely to feel the impact of laws limiting out-of-pocket costs.

If they have to make up the shortfall from a patient’s reduced payment for a prescription, they will likely raise premiums, said Ms. O’Neill Hayes.

And if patients pay the same price for insulin – regardless of who makes it – drugmakers won’t have much incentive to offer discounts or rebates for formulary placement, she said. Again, that would likely lead to higher premiums.

David Allen, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, said in an interview that AHIP believes lack of competition has driven up insulin prices.

“High prices for insulin correspond with high health insurance costs for insulin,” he said. When CMS starts requiring drugmakers to discount their insulins for Medicare that will allow “health plans to use those savings to reduce out-of-pocket [costs] for seniors.”

He did not respond to a question as to why health insurers were not already passing savings on to commercially insured patients, especially in states with out-of-pocket limits.

Mr. Allen did say that AHIP’s plans “stand ready to work with state policymakers to remove barriers to lower insulin prices for Americans.”

Utah savings hopefully saving lives already

In Utah, legislators tuned out the blame game, and instead were keen to listen to patients, who had many stories about how the high cost of insulin had hurt them, said Ms. Hooley.

She noted an estimated 50,000 Utahans rely on insulin to stay alive.

Ms. Hooley and her chapter convinced legislators to pass a bill that gives insurers the option to cap patient copays at $30 per month, or to put insulin on its lowest formulary tier and waive any patient deductible. That aspect of the law does not go into effect until January 2021, but insurers are already starting to move insulin to the lowest formulary tier.

That has helped some people immediately. One state resident said her most recent insulin prescription cost $7 – instead of the usual $200.

The uninsured are not left totally high and dry either. Starting June 1, anyone in the state could buy through a state bulk-purchasing program, which guaranteed a 60% discount.

Ms. Hooley said she’d recently heard about a patient who usually spent $300 per prescription but was able to buy insulin for $100 through the program.

“Although $100 is still too much, it is nice knowing the Utah Insulin Savings Program is saving lives,” Ms. Hooley concluded.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Drug Overdose and Suicide Among Veteran Enrollees in the VHA: Comparison Among Local, Regional, and National Data

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the US. In 2017, there were 47,173 deaths by suicide (14 deaths per 100,000 people), representing a 33% increase from 1999.1 In 2017 veterans accounted for 13.5% of all suicide deaths among US adults, although veterans comprised only 7.9% of the adult population; the age- and sex-adjusted suicide rate was 1.5 times higher for veterans than that of nonveteran adults.2,3

Among veteran users of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services, mental health and substance use disorders, chronic medical conditions, and chronic pain are associated with an increased risk for suicide.3 About one-half of VHA veterans have been diagnosed with chronic pain.4 A chronic pain diagnosis (eg, back pain, migraine, and psychogenic pain) increased the risk of death by suicide even after adjusting for comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, according to a study on pain and suicide among US veterans.5

One-quarter of veterans received an opioid prescription during VHA outpatient care in 2012.4 Increased prescribing of opioid medications has been associated with opioid overdose and suicides.6-10 Opioids are the most common drugs found in suicide by overdose.11 The rate of opioid-related suicide deaths is 13 times higher among individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) than it is for those without OUD.12 The rate of OUD diagnosis among VHA users was 7 times higher than that for non-VHA users.13

In the US the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths increased from 6 per 100,000 persons in 1999 to 22 per 100,000 in 2017.14 Drug overdoses accounted for 52,404 US deaths in 2015; 33,091 (63.1%) were from opioids.15 In 2017, there were 70,237 drug overdose deaths; 67.8% involved opioids (ie, 5 per 100,000 population represent prescription opioids).16

The VHA is committed to reducing opioid use and veteran suicide prevention. In 2013 the VHA launched the Opioid Safety Initiative employing 4 strategies: education, pain management, risk management, and addiction treatment.17 To address the opioid epidemic, the North Florida/South Georgia Veteran Health System (NF/SGVHS) developed and implemented a multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program that is fully integrated with mental health and addiction services. The purpose of the NF/SGVHS one-stop pain addiction clinic is to provide a treatment program for chronic pain and addiction. The program includes elements of a whole health approach to pain care, including battlefield and traditional acupuncture. The focus went beyond replacing pharmacologic treatments with a complementary integrative health approach to helping veterans regain control of their lives through empowerment, skill building, shared goal setting, and reinforcing self-management.

The self-management programs include a pain school for patient education, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, all stressing self-management offered onsite and via telehealth. Special effort was directed to identify patients with OUD and opioid dependence. Many of these patients were transitioned to buprenorphine, a potent analgesic that suppresses opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms associated with stopping opioids. The clinic was structured so that patients could be seen often for follow-up and support. In addition, open lines of communication and referral were set up between this clinic, the interventional pain clinic, and the physical medicine and rehabilitation service. A detailed description of this program has been published elsewhere.18

The number of veterans receiving opioid prescription across the VHA system decreased by 172,000 prescriptions quarterly between 2012 and 2016.19 Fewer veterans were prescribed high doses of opioids or concomitant interacting medicines and more veterans were receiving nonopioid therapies.19 The prescription reduction across the VHA has varied. For example, from 2012 to 2017 the NF/SGVHS reported an 87% reduction of opioid prescriptions (≥ 100 mg morphine equivalents/d), compared with the VHA national average reduction of 49%.18

Vigorous opioid reduction is controversial. In a systematic review on opioid reduction, Frank and colleagues reported some beneficial effects of opioid reduction, such as increased health-related quality of life.20 However, another study suggested a risk of increased pain with opioid tapering.21 The literature findings on the association between prescription opioid use and suicide are mixed. The VHA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention literature review reported that veterans were at increased risk of committing suicide within the first 6 months of discontinuing opioid therapy.22 Another study reported that veterans who discontinued long-term opioid treatment had an increased risk for suicidal ideation.23 However, higher doses of opioids were associated with an increased risk for suicide among individuals with chronic pain.10 The link between opioid tapering and the risk of suicide or overdose is uncertain.

Bohnert and Ilgen suggested that discontinuing prescription opioids leads to suicide without examining the risk factors that influenced discontinuation is ill-informed.7 Strong evidence about the association or relationship among opioid use, overdose, and suicide is needed. To increase our understanding of that association, Bohnert and Ilgen argued for multifaceted interventions that simultaneously address the shared causes and risk factors for OUD,7 such as the multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program at NF/SGVHS.

Because of the reported association between robust integrated mental health and addiction, primary care pain clinic intervention, and the higher rate of opioid tapering in NF/SGVHS,18 this study aims to describe the pattern of overdose diagnosis (opioid overdose and nonopioid overdose) and pattern of suicide rates among veterans enrolled in NF/SGVHS, Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 8, and the entire VA health care system during 2012 to 2016.The study reviewed and compared overdose diagnosis and suicide rates among veterans across NF/SGVHS and 2 other levels of the VA health care system to determine whether there were variances in the pattern of overdose/suicide rates and to explore these differences.

Methods

In this retrospective study, aggregate data were obtained from several sources. First, the drug overdose data were extracted from the VA Support Service Center (VSSC) medical diagnosis cube. We reviewed the literature for opioid codes reported in the literature and compared these reported opioid International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes with the local facility patient-level comprehensive overdose diagnosis codes. Based on the comparison, we found 98 ICD-9 and ICD-10 overdose diagnosis codes and ran the modified codes against the VSSC national database. Overdose data were aggregated by facility and fiscal year, and the overdose rates (per 1,000) were calculated for unique veteran users at the 3 levels (NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VA national) as the denominator.

Each of the 18 VISNs comprise multiple VAMCs and clinics within a geographic region. VISN 8 encompasses most of Florida and portions of southern Georgia and the Caribbean (Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands), including NF/SGVHS.

In this study, drug overdose refers to the overdose or poisoning from all drugs (ie, opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, sedatives, etc) and defined as any unintentional (accidental), deliberate, or intent undetermined drug poisoning.24 The suicide data for this study were drawn from the VA Suicide Prevention Program at 3 different levels: NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national. Suicide is death caused by an intentional act of injuring oneself with the intent to die.25

This descriptive study compared the rate of annual drug overdoses (per 1,000 enrollees) between NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national from 2012 to 2016. It also compared the annual rate of suicide per 100,000 enrollees across these 3 levels of the VHA. The overdose and suicide rates and numbers are mutually exclusive, meaning the VISN 8 data do not include the NF/SGVHS information, and the national data excluded data from VISN 8 and NF/SGVHS. This approach helped improve the quality of multiple level comparisons for different levels of the VHA system.

Results

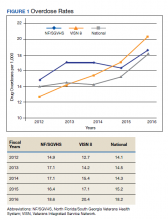

Figure 1 shows the pattern of overdose diagnosis by rates (per 1,000) across the study period (2012 to 2016) and compares patterns at 3 levels of VHA (NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national). The average annual rate of overdose diagnoses for NF/SGVHS during the study was slightly higher (16.8 per 1,000) than that of VISN 8 (16 per 1,000) and VHA national (15.3 per 1,000), but by the end of the study period the NF/SGVHS rate (18.6 per 1,000) nearly matched the national rate (18.2 per 1,000) and was lower than the VISN 8 rate (20.4 per 1,000). Additionally, NF/SGVHS had less variability (SD, 1.34) in yearly average overdose rates compared with VISN 8 (SD, 2.96), and VHA national (SD, 1.69).

From 2013 to 2014 the overdose diagnosis rate for NF/SGVHS remained the same (17.1 per 1,000). A similar pattern was observed for the VHA national data, whereas the VISN 8 data showed a steady increase during the same period. In 2015, the NF/SGVHS had 0.7 per 1,000 decrease in overdose diagnosis rate, whereas VISN 8 and VHA national data showed 1.7 per 1,000 and 0.9 per 1,000 increases, respectively. During the last year of the study (2016), there was a dramatic increase in overdose diagnosis for all the health care systems, ranging from 2.2 per 1,000 for NF/SGVHS to 3.3 per 1,000 for VISN 8.

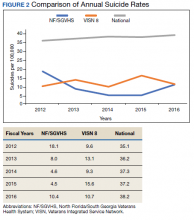

Figure 2 shows the annual rates (per 100,000 individuals) of suicide for NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national. The suicide pattern for VISN 8 shows a cyclical acceleration and deceleration trend across the study period. From 2012 to 2014, the VHA national data show a steady increase of about 1 per 100,000 from year to year. On the contrary, NF/SGVHS shows a low suicide rate from year to year within the same period with a rate of 10 per 100,000 in 2013 compared with the previous year. Although the NF/SGVHS suicide rate increased in 2016 (10.4 per 100,000), it remained lower than that of VISN 8 (10.7 per 100,00) and VHA national (38.2 per 100,000).

This study shows that NF/SGVHS had the lowest average annual rate of suicide (9.1 per 100,000) during the study period, which was 4 times lower than that of VHA national and 2.6 times lower than VISN 8.

Discussion

This study described and compared the distribution pattern of overdose (nonopioid and opioid) and suicide rates at different levels of the VHA system. Although VHA implemented systemwide opioid tapering in 2013, little is known about the association between opioid tapering and overdose and suicide. We believe a retrospective examination regarding overdose and suicide among VHA users at 3 different levels of the system from 2012 to 2016 could contribute to the discussion regarding the potential risks and benefits of discontinuing opioids.

First, the average annual rate of overdose diagnosis for NF/SGVHS during the study period was slightly higher (16.8 per 1,000) compared with those of VISN 8 (16.0 per 1,000) and VHA national (15.3 per 1,000) with a general pattern of increase and minimum variations in the rates observed during the study period among the 3 levels of the system. These increased overdose patterns are consistent with other reports in the literature.14 By the end of the study period, the NF/SGVHS rate (18.6 per 1,000) nearly matched the national rate (18.2 per 1,000) and was lower than VISN 8 (20.4 per 1,000). During the last year of the study period (2016), there was a dramatic increase in overdose diagnosis for all health care systems ranging from 2.2 per 1,000 for NF/SGVHS to 3.3 per 1,000 for VISN 8, which might be because of the VHA systemwide change of diagnosis code from ICD-9 to ICD-10, which includes more detailed diagnosis codes.

Second, our results showed that NF/SGVHS had the lowest average annual suicide rate (9.1 per 100,000) during the study period, which is one-fourth the VHA national rate and 2.6 per 100,000 lower than the VISN 8 rate. According to Bohnert and Ilgen,programs that improve the quality of pain care, expand access to psychotherapy, and increase access to medication-assisted treatment for OUDs could reduce suicide by drug overdose.7 We suggest that the low suicide rate at NF/SGVHS and the difference in the suicide rates between the NF/SGVHS and VISN 8 and VHA national data might be associated with the practice-based biopsychosocial interventions implemented at NF/SGVHS.

Our data showed a rise in the incidence of suicide at the NF/SGVHS in 2016. We are not aware of a local change in conditions, policy, and practice that would account for this increase. Suicide is variable, and data are likely to show spikes and valleys. Based on the available data, although the incidence of suicides at the NF/SGVHS in 2016 was higher, it remained below the VISN 8 and national VHA rate. This study seems to support the practice of tapering or stopping opioids within the context of a multidisciplinary approach that offers frequent follow-up, nonopioid options, and treatment of opioid addiction/dependence.

Limitations

The research findings of this study are limited by the retrospective and descriptive nature of its design. However, the findings might provide important information for understanding variations of overdose and suicide among VHA enrollees. Studies that use more robust methodologies are warranted to clinically investigate the impact of a multispecialty opioid risk reduction program targeting chronic pain and addiction management and identify best practices of opioid reduction and any unintended consequences that might arise from opioid tapering.26 Further, we did not have access to the VA national overdose and suicide data after 2016. Similar to most retrospective data studies, ours might be limited by availability of national overdose and suicide data after 2016. It is important for future studies to cross-validate our study findings.

Conclusions

The NF/SGVHS developed and implemented a biopsychosocial model of pain treatment that includes multicomponent primary care integrated with mental health and addiction services as well as the interventional pain and physical medicine and rehabilitation services. The presence of this program, during a period when the facility was tapering opioids is likely to account for at least part of the relative reduction in suicide.

1. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Suicide statistics. https://afsp.org/about-suicide/suicide-statistics. Updated 2019. Accessed September 2, 2020.

2. Shane L 3rd. New veteran suicide numbers raise concerns among experts hoping for positive news. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2019/10/09/new-veteran-suicide-numbers-raise-concerns-among-experts-hoping-for-positive-news. Published October 9, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2020.

3. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Veteran suicide data report, 2005–2017. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf. Published September 2019. Accessed July 20, 2020.

4. Gallagher RM. Advancing the pain agenda in the veteran population. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(2):357-378. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2016.01.003

5. Ilgen MA, Kleinberg F, Ignacio RV, et al. Noncancer pain conditions and risk of suicide. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):692-697. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.908

6. Frenk SM, Porter KS, Paulozzi LJ. Prescription opioid analgesic use among adults: United States, 1999-2012. National Center for Health Statistics data brief. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db189.htm. Published February 25, 2015. Accessed July 20, 2020.

7. Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA. Understanding links among opioid use, overdose, and suicide. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):71-79. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1901540

8. Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85-92. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006

9. Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):686-691. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117

10. Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS, Ganoczy D, Bair MJ, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Opioid dose and risk of suicide. Pain. 2016;157(5):1079-1084. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000484

11. Sinyor M, Howlett A, Cheung AH, Schaffer A. Substances used in completed suicide by overdose in Toronto: an observational study of coroner’s data. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(3):184-191. doi:10.1177/070674371205700308

12. Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: an empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(suppl):S11-S19 doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003.

13. Baser OL, Mardekian XJ, Schaaf D, Wang L, Joshi AV. Prevalence of diagnosed opioid abuse and its economic burden in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Pract. 2014;14(5):437-445. doi:10.1111/papr.12097

14. Hedegaard H, Warner M, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the united states, 1999-2015. National Center for Health Statistics data brief. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db273.pdf. Published February 2017. Accessed July 20, 2020.

15. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1

16. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019,67(5152):1419-1427. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain version 3.0. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/pain/cot. Updated March 1, 2018. Accessed July 20, 2020.

18. Vaughn IA, Beyth RJ, Ayers ML, et al. Multispecialty opioid risk reduction program targeting chronic pain and addiction management in veterans. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):406-411.

19. Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611-612. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0147

20. Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, et al. Patient outcomes in dose reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(3):181-191. doi:10.7326/M17-0598

21. Berna C, Kulich RJ, Rathmell JP. Tapering long-term opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: evidence and recommendations for everyday practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(6):828-842. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.003

22. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Opioid use and suicide risk. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Literature_Review_Opioid_Use_and_Suicide_Risk_508_FINAL_04-26-2019.pdf. Published April 26, 2019. Accessed July 20, 2020.

23. Demidenko MI, Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, Meath THA, Ilgen MA, Lovejoy TI. Suicidal ideation and suicidal self-directed violence following clinician-initiated prescription opioid discontinuation among long-term opioid users. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;47:29-35. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.011

24. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Intentional versus unintentional overdose deaths. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/treatment/intentional-vs-unintentional-overdose-deaths. Updated February 13, 2017. Accessed July 20, 2020.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing suicide. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-factsheet.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed July 20, 2020.

26. Webster LR. Pain and suicide: the other side of the opioid story. Pain Med. 2014;15(3):345-346. doi:10.1111/pme.12398

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the US. In 2017, there were 47,173 deaths by suicide (14 deaths per 100,000 people), representing a 33% increase from 1999.1 In 2017 veterans accounted for 13.5% of all suicide deaths among US adults, although veterans comprised only 7.9% of the adult population; the age- and sex-adjusted suicide rate was 1.5 times higher for veterans than that of nonveteran adults.2,3

Among veteran users of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services, mental health and substance use disorders, chronic medical conditions, and chronic pain are associated with an increased risk for suicide.3 About one-half of VHA veterans have been diagnosed with chronic pain.4 A chronic pain diagnosis (eg, back pain, migraine, and psychogenic pain) increased the risk of death by suicide even after adjusting for comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, according to a study on pain and suicide among US veterans.5

One-quarter of veterans received an opioid prescription during VHA outpatient care in 2012.4 Increased prescribing of opioid medications has been associated with opioid overdose and suicides.6-10 Opioids are the most common drugs found in suicide by overdose.11 The rate of opioid-related suicide deaths is 13 times higher among individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) than it is for those without OUD.12 The rate of OUD diagnosis among VHA users was 7 times higher than that for non-VHA users.13

In the US the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths increased from 6 per 100,000 persons in 1999 to 22 per 100,000 in 2017.14 Drug overdoses accounted for 52,404 US deaths in 2015; 33,091 (63.1%) were from opioids.15 In 2017, there were 70,237 drug overdose deaths; 67.8% involved opioids (ie, 5 per 100,000 population represent prescription opioids).16

The VHA is committed to reducing opioid use and veteran suicide prevention. In 2013 the VHA launched the Opioid Safety Initiative employing 4 strategies: education, pain management, risk management, and addiction treatment.17 To address the opioid epidemic, the North Florida/South Georgia Veteran Health System (NF/SGVHS) developed and implemented a multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program that is fully integrated with mental health and addiction services. The purpose of the NF/SGVHS one-stop pain addiction clinic is to provide a treatment program for chronic pain and addiction. The program includes elements of a whole health approach to pain care, including battlefield and traditional acupuncture. The focus went beyond replacing pharmacologic treatments with a complementary integrative health approach to helping veterans regain control of their lives through empowerment, skill building, shared goal setting, and reinforcing self-management.

The self-management programs include a pain school for patient education, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, all stressing self-management offered onsite and via telehealth. Special effort was directed to identify patients with OUD and opioid dependence. Many of these patients were transitioned to buprenorphine, a potent analgesic that suppresses opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms associated with stopping opioids. The clinic was structured so that patients could be seen often for follow-up and support. In addition, open lines of communication and referral were set up between this clinic, the interventional pain clinic, and the physical medicine and rehabilitation service. A detailed description of this program has been published elsewhere.18

The number of veterans receiving opioid prescription across the VHA system decreased by 172,000 prescriptions quarterly between 2012 and 2016.19 Fewer veterans were prescribed high doses of opioids or concomitant interacting medicines and more veterans were receiving nonopioid therapies.19 The prescription reduction across the VHA has varied. For example, from 2012 to 2017 the NF/SGVHS reported an 87% reduction of opioid prescriptions (≥ 100 mg morphine equivalents/d), compared with the VHA national average reduction of 49%.18

Vigorous opioid reduction is controversial. In a systematic review on opioid reduction, Frank and colleagues reported some beneficial effects of opioid reduction, such as increased health-related quality of life.20 However, another study suggested a risk of increased pain with opioid tapering.21 The literature findings on the association between prescription opioid use and suicide are mixed. The VHA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention literature review reported that veterans were at increased risk of committing suicide within the first 6 months of discontinuing opioid therapy.22 Another study reported that veterans who discontinued long-term opioid treatment had an increased risk for suicidal ideation.23 However, higher doses of opioids were associated with an increased risk for suicide among individuals with chronic pain.10 The link between opioid tapering and the risk of suicide or overdose is uncertain.

Bohnert and Ilgen suggested that discontinuing prescription opioids leads to suicide without examining the risk factors that influenced discontinuation is ill-informed.7 Strong evidence about the association or relationship among opioid use, overdose, and suicide is needed. To increase our understanding of that association, Bohnert and Ilgen argued for multifaceted interventions that simultaneously address the shared causes and risk factors for OUD,7 such as the multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program at NF/SGVHS.

Because of the reported association between robust integrated mental health and addiction, primary care pain clinic intervention, and the higher rate of opioid tapering in NF/SGVHS,18 this study aims to describe the pattern of overdose diagnosis (opioid overdose and nonopioid overdose) and pattern of suicide rates among veterans enrolled in NF/SGVHS, Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 8, and the entire VA health care system during 2012 to 2016.The study reviewed and compared overdose diagnosis and suicide rates among veterans across NF/SGVHS and 2 other levels of the VA health care system to determine whether there were variances in the pattern of overdose/suicide rates and to explore these differences.

Methods

In this retrospective study, aggregate data were obtained from several sources. First, the drug overdose data were extracted from the VA Support Service Center (VSSC) medical diagnosis cube. We reviewed the literature for opioid codes reported in the literature and compared these reported opioid International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes with the local facility patient-level comprehensive overdose diagnosis codes. Based on the comparison, we found 98 ICD-9 and ICD-10 overdose diagnosis codes and ran the modified codes against the VSSC national database. Overdose data were aggregated by facility and fiscal year, and the overdose rates (per 1,000) were calculated for unique veteran users at the 3 levels (NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VA national) as the denominator.

Each of the 18 VISNs comprise multiple VAMCs and clinics within a geographic region. VISN 8 encompasses most of Florida and portions of southern Georgia and the Caribbean (Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands), including NF/SGVHS.

In this study, drug overdose refers to the overdose or poisoning from all drugs (ie, opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, sedatives, etc) and defined as any unintentional (accidental), deliberate, or intent undetermined drug poisoning.24 The suicide data for this study were drawn from the VA Suicide Prevention Program at 3 different levels: NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national. Suicide is death caused by an intentional act of injuring oneself with the intent to die.25

This descriptive study compared the rate of annual drug overdoses (per 1,000 enrollees) between NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national from 2012 to 2016. It also compared the annual rate of suicide per 100,000 enrollees across these 3 levels of the VHA. The overdose and suicide rates and numbers are mutually exclusive, meaning the VISN 8 data do not include the NF/SGVHS information, and the national data excluded data from VISN 8 and NF/SGVHS. This approach helped improve the quality of multiple level comparisons for different levels of the VHA system.

Results

Figure 1 shows the pattern of overdose diagnosis by rates (per 1,000) across the study period (2012 to 2016) and compares patterns at 3 levels of VHA (NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national). The average annual rate of overdose diagnoses for NF/SGVHS during the study was slightly higher (16.8 per 1,000) than that of VISN 8 (16 per 1,000) and VHA national (15.3 per 1,000), but by the end of the study period the NF/SGVHS rate (18.6 per 1,000) nearly matched the national rate (18.2 per 1,000) and was lower than the VISN 8 rate (20.4 per 1,000). Additionally, NF/SGVHS had less variability (SD, 1.34) in yearly average overdose rates compared with VISN 8 (SD, 2.96), and VHA national (SD, 1.69).

From 2013 to 2014 the overdose diagnosis rate for NF/SGVHS remained the same (17.1 per 1,000). A similar pattern was observed for the VHA national data, whereas the VISN 8 data showed a steady increase during the same period. In 2015, the NF/SGVHS had 0.7 per 1,000 decrease in overdose diagnosis rate, whereas VISN 8 and VHA national data showed 1.7 per 1,000 and 0.9 per 1,000 increases, respectively. During the last year of the study (2016), there was a dramatic increase in overdose diagnosis for all the health care systems, ranging from 2.2 per 1,000 for NF/SGVHS to 3.3 per 1,000 for VISN 8.

Figure 2 shows the annual rates (per 100,000 individuals) of suicide for NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national. The suicide pattern for VISN 8 shows a cyclical acceleration and deceleration trend across the study period. From 2012 to 2014, the VHA national data show a steady increase of about 1 per 100,000 from year to year. On the contrary, NF/SGVHS shows a low suicide rate from year to year within the same period with a rate of 10 per 100,000 in 2013 compared with the previous year. Although the NF/SGVHS suicide rate increased in 2016 (10.4 per 100,000), it remained lower than that of VISN 8 (10.7 per 100,00) and VHA national (38.2 per 100,000).

This study shows that NF/SGVHS had the lowest average annual rate of suicide (9.1 per 100,000) during the study period, which was 4 times lower than that of VHA national and 2.6 times lower than VISN 8.

Discussion

This study described and compared the distribution pattern of overdose (nonopioid and opioid) and suicide rates at different levels of the VHA system. Although VHA implemented systemwide opioid tapering in 2013, little is known about the association between opioid tapering and overdose and suicide. We believe a retrospective examination regarding overdose and suicide among VHA users at 3 different levels of the system from 2012 to 2016 could contribute to the discussion regarding the potential risks and benefits of discontinuing opioids.

First, the average annual rate of overdose diagnosis for NF/SGVHS during the study period was slightly higher (16.8 per 1,000) compared with those of VISN 8 (16.0 per 1,000) and VHA national (15.3 per 1,000) with a general pattern of increase and minimum variations in the rates observed during the study period among the 3 levels of the system. These increased overdose patterns are consistent with other reports in the literature.14 By the end of the study period, the NF/SGVHS rate (18.6 per 1,000) nearly matched the national rate (18.2 per 1,000) and was lower than VISN 8 (20.4 per 1,000). During the last year of the study period (2016), there was a dramatic increase in overdose diagnosis for all health care systems ranging from 2.2 per 1,000 for NF/SGVHS to 3.3 per 1,000 for VISN 8, which might be because of the VHA systemwide change of diagnosis code from ICD-9 to ICD-10, which includes more detailed diagnosis codes.

Second, our results showed that NF/SGVHS had the lowest average annual suicide rate (9.1 per 100,000) during the study period, which is one-fourth the VHA national rate and 2.6 per 100,000 lower than the VISN 8 rate. According to Bohnert and Ilgen,programs that improve the quality of pain care, expand access to psychotherapy, and increase access to medication-assisted treatment for OUDs could reduce suicide by drug overdose.7 We suggest that the low suicide rate at NF/SGVHS and the difference in the suicide rates between the NF/SGVHS and VISN 8 and VHA national data might be associated with the practice-based biopsychosocial interventions implemented at NF/SGVHS.

Our data showed a rise in the incidence of suicide at the NF/SGVHS in 2016. We are not aware of a local change in conditions, policy, and practice that would account for this increase. Suicide is variable, and data are likely to show spikes and valleys. Based on the available data, although the incidence of suicides at the NF/SGVHS in 2016 was higher, it remained below the VISN 8 and national VHA rate. This study seems to support the practice of tapering or stopping opioids within the context of a multidisciplinary approach that offers frequent follow-up, nonopioid options, and treatment of opioid addiction/dependence.

Limitations

The research findings of this study are limited by the retrospective and descriptive nature of its design. However, the findings might provide important information for understanding variations of overdose and suicide among VHA enrollees. Studies that use more robust methodologies are warranted to clinically investigate the impact of a multispecialty opioid risk reduction program targeting chronic pain and addiction management and identify best practices of opioid reduction and any unintended consequences that might arise from opioid tapering.26 Further, we did not have access to the VA national overdose and suicide data after 2016. Similar to most retrospective data studies, ours might be limited by availability of national overdose and suicide data after 2016. It is important for future studies to cross-validate our study findings.

Conclusions

The NF/SGVHS developed and implemented a biopsychosocial model of pain treatment that includes multicomponent primary care integrated with mental health and addiction services as well as the interventional pain and physical medicine and rehabilitation services. The presence of this program, during a period when the facility was tapering opioids is likely to account for at least part of the relative reduction in suicide.

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the US. In 2017, there were 47,173 deaths by suicide (14 deaths per 100,000 people), representing a 33% increase from 1999.1 In 2017 veterans accounted for 13.5% of all suicide deaths among US adults, although veterans comprised only 7.9% of the adult population; the age- and sex-adjusted suicide rate was 1.5 times higher for veterans than that of nonveteran adults.2,3

Among veteran users of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services, mental health and substance use disorders, chronic medical conditions, and chronic pain are associated with an increased risk for suicide.3 About one-half of VHA veterans have been diagnosed with chronic pain.4 A chronic pain diagnosis (eg, back pain, migraine, and psychogenic pain) increased the risk of death by suicide even after adjusting for comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, according to a study on pain and suicide among US veterans.5

One-quarter of veterans received an opioid prescription during VHA outpatient care in 2012.4 Increased prescribing of opioid medications has been associated with opioid overdose and suicides.6-10 Opioids are the most common drugs found in suicide by overdose.11 The rate of opioid-related suicide deaths is 13 times higher among individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) than it is for those without OUD.12 The rate of OUD diagnosis among VHA users was 7 times higher than that for non-VHA users.13

In the US the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths increased from 6 per 100,000 persons in 1999 to 22 per 100,000 in 2017.14 Drug overdoses accounted for 52,404 US deaths in 2015; 33,091 (63.1%) were from opioids.15 In 2017, there were 70,237 drug overdose deaths; 67.8% involved opioids (ie, 5 per 100,000 population represent prescription opioids).16

The VHA is committed to reducing opioid use and veteran suicide prevention. In 2013 the VHA launched the Opioid Safety Initiative employing 4 strategies: education, pain management, risk management, and addiction treatment.17 To address the opioid epidemic, the North Florida/South Georgia Veteran Health System (NF/SGVHS) developed and implemented a multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program that is fully integrated with mental health and addiction services. The purpose of the NF/SGVHS one-stop pain addiction clinic is to provide a treatment program for chronic pain and addiction. The program includes elements of a whole health approach to pain care, including battlefield and traditional acupuncture. The focus went beyond replacing pharmacologic treatments with a complementary integrative health approach to helping veterans regain control of their lives through empowerment, skill building, shared goal setting, and reinforcing self-management.

The self-management programs include a pain school for patient education, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, all stressing self-management offered onsite and via telehealth. Special effort was directed to identify patients with OUD and opioid dependence. Many of these patients were transitioned to buprenorphine, a potent analgesic that suppresses opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms associated with stopping opioids. The clinic was structured so that patients could be seen often for follow-up and support. In addition, open lines of communication and referral were set up between this clinic, the interventional pain clinic, and the physical medicine and rehabilitation service. A detailed description of this program has been published elsewhere.18

The number of veterans receiving opioid prescription across the VHA system decreased by 172,000 prescriptions quarterly between 2012 and 2016.19 Fewer veterans were prescribed high doses of opioids or concomitant interacting medicines and more veterans were receiving nonopioid therapies.19 The prescription reduction across the VHA has varied. For example, from 2012 to 2017 the NF/SGVHS reported an 87% reduction of opioid prescriptions (≥ 100 mg morphine equivalents/d), compared with the VHA national average reduction of 49%.18

Vigorous opioid reduction is controversial. In a systematic review on opioid reduction, Frank and colleagues reported some beneficial effects of opioid reduction, such as increased health-related quality of life.20 However, another study suggested a risk of increased pain with opioid tapering.21 The literature findings on the association between prescription opioid use and suicide are mixed. The VHA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention literature review reported that veterans were at increased risk of committing suicide within the first 6 months of discontinuing opioid therapy.22 Another study reported that veterans who discontinued long-term opioid treatment had an increased risk for suicidal ideation.23 However, higher doses of opioids were associated with an increased risk for suicide among individuals with chronic pain.10 The link between opioid tapering and the risk of suicide or overdose is uncertain.

Bohnert and Ilgen suggested that discontinuing prescription opioids leads to suicide without examining the risk factors that influenced discontinuation is ill-informed.7 Strong evidence about the association or relationship among opioid use, overdose, and suicide is needed. To increase our understanding of that association, Bohnert and Ilgen argued for multifaceted interventions that simultaneously address the shared causes and risk factors for OUD,7 such as the multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program at NF/SGVHS.

Because of the reported association between robust integrated mental health and addiction, primary care pain clinic intervention, and the higher rate of opioid tapering in NF/SGVHS,18 this study aims to describe the pattern of overdose diagnosis (opioid overdose and nonopioid overdose) and pattern of suicide rates among veterans enrolled in NF/SGVHS, Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 8, and the entire VA health care system during 2012 to 2016.The study reviewed and compared overdose diagnosis and suicide rates among veterans across NF/SGVHS and 2 other levels of the VA health care system to determine whether there were variances in the pattern of overdose/suicide rates and to explore these differences.

Methods

In this retrospective study, aggregate data were obtained from several sources. First, the drug overdose data were extracted from the VA Support Service Center (VSSC) medical diagnosis cube. We reviewed the literature for opioid codes reported in the literature and compared these reported opioid International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes with the local facility patient-level comprehensive overdose diagnosis codes. Based on the comparison, we found 98 ICD-9 and ICD-10 overdose diagnosis codes and ran the modified codes against the VSSC national database. Overdose data were aggregated by facility and fiscal year, and the overdose rates (per 1,000) were calculated for unique veteran users at the 3 levels (NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VA national) as the denominator.

Each of the 18 VISNs comprise multiple VAMCs and clinics within a geographic region. VISN 8 encompasses most of Florida and portions of southern Georgia and the Caribbean (Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands), including NF/SGVHS.

In this study, drug overdose refers to the overdose or poisoning from all drugs (ie, opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, sedatives, etc) and defined as any unintentional (accidental), deliberate, or intent undetermined drug poisoning.24 The suicide data for this study were drawn from the VA Suicide Prevention Program at 3 different levels: NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national. Suicide is death caused by an intentional act of injuring oneself with the intent to die.25

This descriptive study compared the rate of annual drug overdoses (per 1,000 enrollees) between NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national from 2012 to 2016. It also compared the annual rate of suicide per 100,000 enrollees across these 3 levels of the VHA. The overdose and suicide rates and numbers are mutually exclusive, meaning the VISN 8 data do not include the NF/SGVHS information, and the national data excluded data from VISN 8 and NF/SGVHS. This approach helped improve the quality of multiple level comparisons for different levels of the VHA system.

Results

Figure 1 shows the pattern of overdose diagnosis by rates (per 1,000) across the study period (2012 to 2016) and compares patterns at 3 levels of VHA (NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national). The average annual rate of overdose diagnoses for NF/SGVHS during the study was slightly higher (16.8 per 1,000) than that of VISN 8 (16 per 1,000) and VHA national (15.3 per 1,000), but by the end of the study period the NF/SGVHS rate (18.6 per 1,000) nearly matched the national rate (18.2 per 1,000) and was lower than the VISN 8 rate (20.4 per 1,000). Additionally, NF/SGVHS had less variability (SD, 1.34) in yearly average overdose rates compared with VISN 8 (SD, 2.96), and VHA national (SD, 1.69).

From 2013 to 2014 the overdose diagnosis rate for NF/SGVHS remained the same (17.1 per 1,000). A similar pattern was observed for the VHA national data, whereas the VISN 8 data showed a steady increase during the same period. In 2015, the NF/SGVHS had 0.7 per 1,000 decrease in overdose diagnosis rate, whereas VISN 8 and VHA national data showed 1.7 per 1,000 and 0.9 per 1,000 increases, respectively. During the last year of the study (2016), there was a dramatic increase in overdose diagnosis for all the health care systems, ranging from 2.2 per 1,000 for NF/SGVHS to 3.3 per 1,000 for VISN 8.

Figure 2 shows the annual rates (per 100,000 individuals) of suicide for NF/SGVHS, VISN 8, and VHA national. The suicide pattern for VISN 8 shows a cyclical acceleration and deceleration trend across the study period. From 2012 to 2014, the VHA national data show a steady increase of about 1 per 100,000 from year to year. On the contrary, NF/SGVHS shows a low suicide rate from year to year within the same period with a rate of 10 per 100,000 in 2013 compared with the previous year. Although the NF/SGVHS suicide rate increased in 2016 (10.4 per 100,000), it remained lower than that of VISN 8 (10.7 per 100,00) and VHA national (38.2 per 100,000).

This study shows that NF/SGVHS had the lowest average annual rate of suicide (9.1 per 100,000) during the study period, which was 4 times lower than that of VHA national and 2.6 times lower than VISN 8.

Discussion

This study described and compared the distribution pattern of overdose (nonopioid and opioid) and suicide rates at different levels of the VHA system. Although VHA implemented systemwide opioid tapering in 2013, little is known about the association between opioid tapering and overdose and suicide. We believe a retrospective examination regarding overdose and suicide among VHA users at 3 different levels of the system from 2012 to 2016 could contribute to the discussion regarding the potential risks and benefits of discontinuing opioids.

First, the average annual rate of overdose diagnosis for NF/SGVHS during the study period was slightly higher (16.8 per 1,000) compared with those of VISN 8 (16.0 per 1,000) and VHA national (15.3 per 1,000) with a general pattern of increase and minimum variations in the rates observed during the study period among the 3 levels of the system. These increased overdose patterns are consistent with other reports in the literature.14 By the end of the study period, the NF/SGVHS rate (18.6 per 1,000) nearly matched the national rate (18.2 per 1,000) and was lower than VISN 8 (20.4 per 1,000). During the last year of the study period (2016), there was a dramatic increase in overdose diagnosis for all health care systems ranging from 2.2 per 1,000 for NF/SGVHS to 3.3 per 1,000 for VISN 8, which might be because of the VHA systemwide change of diagnosis code from ICD-9 to ICD-10, which includes more detailed diagnosis codes.

Second, our results showed that NF/SGVHS had the lowest average annual suicide rate (9.1 per 100,000) during the study period, which is one-fourth the VHA national rate and 2.6 per 100,000 lower than the VISN 8 rate. According to Bohnert and Ilgen,programs that improve the quality of pain care, expand access to psychotherapy, and increase access to medication-assisted treatment for OUDs could reduce suicide by drug overdose.7 We suggest that the low suicide rate at NF/SGVHS and the difference in the suicide rates between the NF/SGVHS and VISN 8 and VHA national data might be associated with the practice-based biopsychosocial interventions implemented at NF/SGVHS.

Our data showed a rise in the incidence of suicide at the NF/SGVHS in 2016. We are not aware of a local change in conditions, policy, and practice that would account for this increase. Suicide is variable, and data are likely to show spikes and valleys. Based on the available data, although the incidence of suicides at the NF/SGVHS in 2016 was higher, it remained below the VISN 8 and national VHA rate. This study seems to support the practice of tapering or stopping opioids within the context of a multidisciplinary approach that offers frequent follow-up, nonopioid options, and treatment of opioid addiction/dependence.

Limitations

The research findings of this study are limited by the retrospective and descriptive nature of its design. However, the findings might provide important information for understanding variations of overdose and suicide among VHA enrollees. Studies that use more robust methodologies are warranted to clinically investigate the impact of a multispecialty opioid risk reduction program targeting chronic pain and addiction management and identify best practices of opioid reduction and any unintended consequences that might arise from opioid tapering.26 Further, we did not have access to the VA national overdose and suicide data after 2016. Similar to most retrospective data studies, ours might be limited by availability of national overdose and suicide data after 2016. It is important for future studies to cross-validate our study findings.

Conclusions

The NF/SGVHS developed and implemented a biopsychosocial model of pain treatment that includes multicomponent primary care integrated with mental health and addiction services as well as the interventional pain and physical medicine and rehabilitation services. The presence of this program, during a period when the facility was tapering opioids is likely to account for at least part of the relative reduction in suicide.

1. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Suicide statistics. https://afsp.org/about-suicide/suicide-statistics. Updated 2019. Accessed September 2, 2020.

2. Shane L 3rd. New veteran suicide numbers raise concerns among experts hoping for positive news. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2019/10/09/new-veteran-suicide-numbers-raise-concerns-among-experts-hoping-for-positive-news. Published October 9, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2020.

3. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Veteran suicide data report, 2005–2017. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf. Published September 2019. Accessed July 20, 2020.

4. Gallagher RM. Advancing the pain agenda in the veteran population. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(2):357-378. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2016.01.003

5. Ilgen MA, Kleinberg F, Ignacio RV, et al. Noncancer pain conditions and risk of suicide. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):692-697. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.908

6. Frenk SM, Porter KS, Paulozzi LJ. Prescription opioid analgesic use among adults: United States, 1999-2012. National Center for Health Statistics data brief. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db189.htm. Published February 25, 2015. Accessed July 20, 2020.

7. Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA. Understanding links among opioid use, overdose, and suicide. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):71-79. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1901540

8. Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85-92. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006

9. Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):686-691. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117

10. Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS, Ganoczy D, Bair MJ, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Opioid dose and risk of suicide. Pain. 2016;157(5):1079-1084. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000484

11. Sinyor M, Howlett A, Cheung AH, Schaffer A. Substances used in completed suicide by overdose in Toronto: an observational study of coroner’s data. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(3):184-191. doi:10.1177/070674371205700308

12. Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: an empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(suppl):S11-S19 doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003.