User login

Pan-Pseudothrombocytopenia in COVID-19: A Harbinger for Lethal Arterial Thrombosis?

In late 2019 a new pandemic started in Wuhan, China, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) due to its similarities with the virus responsible for the SARS outbreak of 2003. The disease manifestations are named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or platelet clumping, visualized on the peripheral blood smear, is a common cause for artificial thrombocytopenia laboratory reporting and is frequently attributed to laboratory artifact. In this case presentation, a critically ill patient with COVID-19 developed pan-pseudothrombocytopenia (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], sodium citrate, and heparin tubes) just prior to his death from a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the setting of therapeutic anticoagulation during a prolonged hospitalization. This case raises the possibility that pseudothrombocytopenia in the setting of COVID-19 critical illness may represent an ominous feature of COVID-19-associated coagulopathy (CAC). Furthermore, it prompts the question whether pseudothrombocytopenia in this setting is representative of increased platelet aggregation activity in vivo.

Case Presentation

A 50-year-old African American man who was diagnosed with COVID-19 3 days prior to admission presented to the emergency department of the W.G. (Bill) Hefner VA Medical Center in Salisbury, North Carolina, with worsening dyspnea and fever. His primary chronic medical problems included obesity (body mass index, 33), type 2 diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c 2 months prior of 6.6%), migraine headaches, and obstructive sleep apnea. Shortly after presentation, his respiratory status declined, requiring intubation. He was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further management.

Notable findings at admission included > 20 mcg/mL FEU D-dimer (normal range, 0-0.56 mcg/mL FEU), 20.4 mg/dL C-reactive protein (normal range, < 1 mg/dL), 30 mm/h erythrocyte sedimentation rate (normal range, 0-25 mm/h), and 3.56 ng/mL procalcitonin (normal range, 0.05-1.99 ng/mL). Patient’s hemoglobin and platelet counts were normal. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was initiated with ceftriaxone (2 g IV daily) and doxycycline (100 mg IV twice daily) due to concern of superimposed infection in the setting of an elevated procalcitonin.

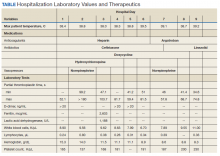

A heparin infusion was initiated (5,000 U IV bolus followed by continuous infusion with goal partial thromboplastin time [PTT] of 1.5x the upper limit of normal) on admission to treat CAC. Renal function worsened requiring intermittent renal replacement therapy on day 3. His lactate dehydrogenase was elevated to 1,188 U/L (normal range: 100-240 U/L) and ferritin was elevated to 2,603 ng/mL (normal range: 25-350 ng/mL) (Table). Initial neuromuscular blockade and prone positioning maneuvers were instituted to optimize oxygenation based on the latest literature for respiratory distress in the COVID-19 management.2

Intermittent norepinephrine infusion (5 mcg/min with a 2 mcg/min titration every 5 minutes as needed to maintain mean arterial pressure of > 65 mm Hg) was required for hemodynamic support throughout the patient’s course. Several therapies for COVID-19 were considered and were a reflection of the rapidly evolving literature during the care of patients with this disease. The patient originally received hydroxychloroquine (200 mg by mouth twice daily) in accordance with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) institutional protocol between day 2 and day 4; however, hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to concerns of QTc prolongation. The patient also received 1 unit of convalescent plasma on day 6 after being enrolled in the expanded access program.3 The patient was not a candidate for remdesivir due to his unstable renal function and need for vasopressors. Finally, interleukin-6 inhibitors also were considered; however, the risk of superimposed infection precluded its use.

On day 7 antimicrobial therapy was transitioned to linezolid (600 mg IV twice daily) due to the persistence of fever and a portable chest radiograph revealing diffuse infiltrates throughout the bilateral lungs, worse compared with prior radiograph on day 5, suggesting a worsening of pneumonia. On day 12, the patient was transitioned to cefepime (1 gram IV daily) to broaden antimicrobial coverage and was continued thereafter. Blood cultures were negative throughout his hospitalization.

Given his worsening clinical scenario there was a question about whether or not the patient was still shedding virus for prognostic and therapeutic implications. Therefore, his SARS-CoV-2 test by polymerase chain reaction nasopharyngeal was positive again on day 18. On day 20, the patient developed leukocytosis, his fever persisted, and a portable chest radiograph revealed extensive bilateral pulmonary opacities with focal worsening in left lower base. Due to this constellation of findings, a vancomycin IV (1,500 mg once) was started for empirical treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Sputum samples obtained on day 20 revealed Staphylococcus aureus on subsequent days.

From a hematologic perspective, on day 9 due to challenges to maintain a therapeutic level of anticoagulation with heparin infusion thought to be related to antithrombin deficiency, anticoagulation was changed to argatroban infusion (0.5 mcg/kg/min targeting a PTT of 70-105 seconds) for ongoing management of CAC. Although D-dimer was > 20 mcg/mL FEU on admission and on days 4 and 5, D-dimer trended down to 12.5 mcg/mL FEU on day 16.

Throughout the patient’s hospital stay, no significant bleeding was seen. Hemoglobin was 15.2 g/dL on admission, but anemia developed with a nadir of 6.5 g/dL, warranting transfusion of red blood cells on day 22. Platelet count was 165,000 per microliter on admission and remained within normal limits until platelet clumping was noted on day 15 laboratory collection.

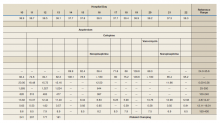

Hematology was consulted on day 20 to obtain an accurate platelet count. A peripheral blood smear from a sodium citrate containing tube was remarkable for prominent platelet clumping, particularly at the periphery of the slide (Figure 1). Platelet clumping was reproduced in samples containing EDTA and heparin. Other features of the peripheral blood smear included the presence of echinocytes with rare schistocytes. To investigate for presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation on day 22, fibrinogen was found to be mildly elevated at 538 mg/dL (normal range: 243-517 mg/dL) and a D-dimer value of 11.96 mcg/mL FEU.

On day 22, the patient’s ventilator requirements escalated to requiring 100% FiO2 and 10 cm H20 of positive end-expiratory pressure with mean arterial pressures in the 50 to 60 mm Hg range. Within 30 minutes an electrocardiogram (EKG) obtained revealed a STEMI (Figure 2). Troponin was measured at 0.65 ng/mL (normal range: 0.02-0.06 ng/mL). Just after an EKG was performed, the patient developed a ventricular fibrillation arrest and was unable to obtain return of spontaneous circulation. The patient was pronounced dead. The family declined an autopsy.

Discussion

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or platelet clumping (agglutination), is estimated to be present in up to 2% of hospitalized patients.4 Pseudothrombocytopenia was found to be the root cause of thrombocytopenia hematology consultations in up to 4% of hospitalized patients.5 The etiology is commonly ascribed to EDTA inducing a conformational change in the GpIIb-IIIa platelet complex, rendering it susceptible to binding of autoantibodies, which cause subsequent platelet agglutination.6 In most cases (83%), the use of a non-EDTA anticoagulant, such as sodium citrate, resolves the platelet agglutination and allows for accurate platelet count reporting.4 Pseudothrombocytopenia in most cases is considered an in vitro finding without clinical relevance.7 However, in this patient’s case, his pan-pseudothrombocytopenia was temporally associated with an arterial occlusive event (STEMI) leading to his demise despite therapeutic anticoagulation in the setting of CAC. This temporal association raises the possibility that pseudothrombocytopenia seen on the peripheral blood smear is an accurate representation of in vivo activity.

Pseudothrombocytopenia has been associated with sepsis from bacterial and viral causes as well as autoimmune and medication effect.4,8-10 Li and colleagues reported transient EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with COVID-19 infection; however, platelet clumping resolved with use of a citrate tube, and the EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia phenomenon resolved with patient recovery.11 The frequency of COVID-19-related pseudothrombocytopenia is currently unknown.

Although the understanding of COVID-19-associated CAC continues to evolve, it seems that initial reports support the idea that hemostatic dysfunction tends to more thrombosis than to bleeding.12 Rather than overt disseminated intravascular coagulation with reduced fibrinogen and bleeding, CAC is more closely associated with blood clotting, as demonstrated by autopsy studies revealing microvascular thrombosis in the lungs.13 The D-dimer test has been identified as the most useful biomarker by the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis to screen for CAC and stratify patients who warrant admission or closer monitoring.12 Other identified features of CAC include prolonged prothrombin time and thrombocytopenia.12

There have been varying clinical approaches to CAC management. A retrospective review found that prophylactic heparin doses were associated with improved mortality in those with elevated D-dimer > 3.0 mg/L.14 There continues to be a diversity of varying clinical approaches with many medical centers advocating for an intensified prophylactic twice daily low molecular-weight heparin compared with others advocating for full therapeutic dose anticoagulation for patients with elevated D-dimer.15 This patient was treated aggressively with full-dose anticoagulation, and despite his having a down-trend in D-dimer, he suffered a lethal arterial thrombosis in the form of a STEMI.

Varatharajah and Rajah

Conclusions

This patient’s case highlights the presence of pan-pseudothrombocytopenia despite the use of a sodium citrate and heparin containing tube in a COVID-19 infection with multiorgan dysfunction. This developed 1 week prior to the patient suffering a STEMI despite therapeutic anticoagulation. Although the exact nature of CAC remains to be worked out, it is possible that platelet agglutination/clumping seen on the peripheral blood smear is representative of in vivo activity and serves as a harbinger for worsening thrombosis. The frequency of such phenomenon and efficacy of further interventions has yet to be explored.

1. World Health Organization. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(COVID-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it. Accessed July 15, 2020.

2. Ghelichkhani P, Esmaeili M. Prone position in management of COVID-19 patients; a commentary. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e48. Published 2020 April 11.

3. National Library of Medicine, Clinicaltrials.gov. Expanded access to convalescent plasma for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. NCT04338360. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/nct04338360. Update April 20, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020.

4. Tan GC, Stalling M, Dennis G, Nunez M, Kahwash SB. Pseudothrombocytopenia due to platelet clumping: a case report and brief review of the literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2016;2016:3036476. doi:10.1155/2016/3036476

5. Boxer M, Biuso TJ. Etiologies of thrombocytopenia in the community hospital: the experience of 1 hematologist. Am J Med. 2020;133(5):e183-e186. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.027

6. Fiorin F, Steffan A, Pradella P, Bizzaro N, Potenza R, De Angelis V. IgG platelet antibodies in EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia bind to platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110(2):178-183. doi:10.1093/ajcp/110.2.178

7. Nagler M, Keller P, Siegrist S, Alberio L. A case of EDTA-Dependent pseudothrombocytopenia: simple recognition of an underdiagnosed and misleading phenomenon. BMC Clin Pathol. 2014;14:19. doi:10.1186/1472-6890-14-19

8. Mori M, Kudo H, Yoshitake S, Ito K, Shinguu C, Noguchi T. Transient EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(2):218-220. doi:10.1007/s001340050050.

9. Choe W-H, Cho Y-U, Chae J-D, Kim S-H. 2013. Pseudothrombocytopenia or platelet clumping as a possible cause of low platelet count in patients with viral infection: a case series from single institution focusing on hepatitis A virus infection. Int J Lab Hematol. 2013;35(1):70-76. doi:10.1111/j.1751-553x.2012.01466.

10. Hsieh AT, Chao TY, Chen YC. Pseudothrombocytopenia associated with infectious mononucleosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127(1):e17-e18. doi:10.1043/0003-9985(2003)1272.0.CO;2

11. Li H, Wang B, Ning L, Luo Y, Xiang S. Transient appearance of EDTA dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 5]. Platelets. 2020;1-2. doi:10.1080/09537104.2020.1760231

12. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023-1026. doi:10.1111/jth.14810

13. Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

14. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094-1099. doi:10.1111/jth.14817

15. Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;125(23):2033-2040. doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020006000.

16. Varatharajah N, Rajah S. Microthrombotic complications of COVID-19 are likely due to embolism of circulating endothelial derived ultralarge von Willebrand factor (eULVWF) Decorated-Platelet Strings. Fed Pract. 2020;37(6):258-259. doi:10.12788/fp.0001

17. Bernardo A, Ball C, Nolasco L, Choi H, Moake JL, Dong JF. Platelets adhered to endothelial cell-bound ultra-large von Willebrand factor strings support leukocyte tethering and rolling under high shear stress. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(3):562-570. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01122.x

In late 2019 a new pandemic started in Wuhan, China, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) due to its similarities with the virus responsible for the SARS outbreak of 2003. The disease manifestations are named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or platelet clumping, visualized on the peripheral blood smear, is a common cause for artificial thrombocytopenia laboratory reporting and is frequently attributed to laboratory artifact. In this case presentation, a critically ill patient with COVID-19 developed pan-pseudothrombocytopenia (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], sodium citrate, and heparin tubes) just prior to his death from a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the setting of therapeutic anticoagulation during a prolonged hospitalization. This case raises the possibility that pseudothrombocytopenia in the setting of COVID-19 critical illness may represent an ominous feature of COVID-19-associated coagulopathy (CAC). Furthermore, it prompts the question whether pseudothrombocytopenia in this setting is representative of increased platelet aggregation activity in vivo.

Case Presentation

A 50-year-old African American man who was diagnosed with COVID-19 3 days prior to admission presented to the emergency department of the W.G. (Bill) Hefner VA Medical Center in Salisbury, North Carolina, with worsening dyspnea and fever. His primary chronic medical problems included obesity (body mass index, 33), type 2 diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c 2 months prior of 6.6%), migraine headaches, and obstructive sleep apnea. Shortly after presentation, his respiratory status declined, requiring intubation. He was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further management.

Notable findings at admission included > 20 mcg/mL FEU D-dimer (normal range, 0-0.56 mcg/mL FEU), 20.4 mg/dL C-reactive protein (normal range, < 1 mg/dL), 30 mm/h erythrocyte sedimentation rate (normal range, 0-25 mm/h), and 3.56 ng/mL procalcitonin (normal range, 0.05-1.99 ng/mL). Patient’s hemoglobin and platelet counts were normal. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was initiated with ceftriaxone (2 g IV daily) and doxycycline (100 mg IV twice daily) due to concern of superimposed infection in the setting of an elevated procalcitonin.

A heparin infusion was initiated (5,000 U IV bolus followed by continuous infusion with goal partial thromboplastin time [PTT] of 1.5x the upper limit of normal) on admission to treat CAC. Renal function worsened requiring intermittent renal replacement therapy on day 3. His lactate dehydrogenase was elevated to 1,188 U/L (normal range: 100-240 U/L) and ferritin was elevated to 2,603 ng/mL (normal range: 25-350 ng/mL) (Table). Initial neuromuscular blockade and prone positioning maneuvers were instituted to optimize oxygenation based on the latest literature for respiratory distress in the COVID-19 management.2

Intermittent norepinephrine infusion (5 mcg/min with a 2 mcg/min titration every 5 minutes as needed to maintain mean arterial pressure of > 65 mm Hg) was required for hemodynamic support throughout the patient’s course. Several therapies for COVID-19 were considered and were a reflection of the rapidly evolving literature during the care of patients with this disease. The patient originally received hydroxychloroquine (200 mg by mouth twice daily) in accordance with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) institutional protocol between day 2 and day 4; however, hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to concerns of QTc prolongation. The patient also received 1 unit of convalescent plasma on day 6 after being enrolled in the expanded access program.3 The patient was not a candidate for remdesivir due to his unstable renal function and need for vasopressors. Finally, interleukin-6 inhibitors also were considered; however, the risk of superimposed infection precluded its use.

On day 7 antimicrobial therapy was transitioned to linezolid (600 mg IV twice daily) due to the persistence of fever and a portable chest radiograph revealing diffuse infiltrates throughout the bilateral lungs, worse compared with prior radiograph on day 5, suggesting a worsening of pneumonia. On day 12, the patient was transitioned to cefepime (1 gram IV daily) to broaden antimicrobial coverage and was continued thereafter. Blood cultures were negative throughout his hospitalization.

Given his worsening clinical scenario there was a question about whether or not the patient was still shedding virus for prognostic and therapeutic implications. Therefore, his SARS-CoV-2 test by polymerase chain reaction nasopharyngeal was positive again on day 18. On day 20, the patient developed leukocytosis, his fever persisted, and a portable chest radiograph revealed extensive bilateral pulmonary opacities with focal worsening in left lower base. Due to this constellation of findings, a vancomycin IV (1,500 mg once) was started for empirical treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Sputum samples obtained on day 20 revealed Staphylococcus aureus on subsequent days.

From a hematologic perspective, on day 9 due to challenges to maintain a therapeutic level of anticoagulation with heparin infusion thought to be related to antithrombin deficiency, anticoagulation was changed to argatroban infusion (0.5 mcg/kg/min targeting a PTT of 70-105 seconds) for ongoing management of CAC. Although D-dimer was > 20 mcg/mL FEU on admission and on days 4 and 5, D-dimer trended down to 12.5 mcg/mL FEU on day 16.

Throughout the patient’s hospital stay, no significant bleeding was seen. Hemoglobin was 15.2 g/dL on admission, but anemia developed with a nadir of 6.5 g/dL, warranting transfusion of red blood cells on day 22. Platelet count was 165,000 per microliter on admission and remained within normal limits until platelet clumping was noted on day 15 laboratory collection.

Hematology was consulted on day 20 to obtain an accurate platelet count. A peripheral blood smear from a sodium citrate containing tube was remarkable for prominent platelet clumping, particularly at the periphery of the slide (Figure 1). Platelet clumping was reproduced in samples containing EDTA and heparin. Other features of the peripheral blood smear included the presence of echinocytes with rare schistocytes. To investigate for presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation on day 22, fibrinogen was found to be mildly elevated at 538 mg/dL (normal range: 243-517 mg/dL) and a D-dimer value of 11.96 mcg/mL FEU.

On day 22, the patient’s ventilator requirements escalated to requiring 100% FiO2 and 10 cm H20 of positive end-expiratory pressure with mean arterial pressures in the 50 to 60 mm Hg range. Within 30 minutes an electrocardiogram (EKG) obtained revealed a STEMI (Figure 2). Troponin was measured at 0.65 ng/mL (normal range: 0.02-0.06 ng/mL). Just after an EKG was performed, the patient developed a ventricular fibrillation arrest and was unable to obtain return of spontaneous circulation. The patient was pronounced dead. The family declined an autopsy.

Discussion

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or platelet clumping (agglutination), is estimated to be present in up to 2% of hospitalized patients.4 Pseudothrombocytopenia was found to be the root cause of thrombocytopenia hematology consultations in up to 4% of hospitalized patients.5 The etiology is commonly ascribed to EDTA inducing a conformational change in the GpIIb-IIIa platelet complex, rendering it susceptible to binding of autoantibodies, which cause subsequent platelet agglutination.6 In most cases (83%), the use of a non-EDTA anticoagulant, such as sodium citrate, resolves the platelet agglutination and allows for accurate platelet count reporting.4 Pseudothrombocytopenia in most cases is considered an in vitro finding without clinical relevance.7 However, in this patient’s case, his pan-pseudothrombocytopenia was temporally associated with an arterial occlusive event (STEMI) leading to his demise despite therapeutic anticoagulation in the setting of CAC. This temporal association raises the possibility that pseudothrombocytopenia seen on the peripheral blood smear is an accurate representation of in vivo activity.

Pseudothrombocytopenia has been associated with sepsis from bacterial and viral causes as well as autoimmune and medication effect.4,8-10 Li and colleagues reported transient EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with COVID-19 infection; however, platelet clumping resolved with use of a citrate tube, and the EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia phenomenon resolved with patient recovery.11 The frequency of COVID-19-related pseudothrombocytopenia is currently unknown.

Although the understanding of COVID-19-associated CAC continues to evolve, it seems that initial reports support the idea that hemostatic dysfunction tends to more thrombosis than to bleeding.12 Rather than overt disseminated intravascular coagulation with reduced fibrinogen and bleeding, CAC is more closely associated with blood clotting, as demonstrated by autopsy studies revealing microvascular thrombosis in the lungs.13 The D-dimer test has been identified as the most useful biomarker by the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis to screen for CAC and stratify patients who warrant admission or closer monitoring.12 Other identified features of CAC include prolonged prothrombin time and thrombocytopenia.12

There have been varying clinical approaches to CAC management. A retrospective review found that prophylactic heparin doses were associated with improved mortality in those with elevated D-dimer > 3.0 mg/L.14 There continues to be a diversity of varying clinical approaches with many medical centers advocating for an intensified prophylactic twice daily low molecular-weight heparin compared with others advocating for full therapeutic dose anticoagulation for patients with elevated D-dimer.15 This patient was treated aggressively with full-dose anticoagulation, and despite his having a down-trend in D-dimer, he suffered a lethal arterial thrombosis in the form of a STEMI.

Varatharajah and Rajah

Conclusions

This patient’s case highlights the presence of pan-pseudothrombocytopenia despite the use of a sodium citrate and heparin containing tube in a COVID-19 infection with multiorgan dysfunction. This developed 1 week prior to the patient suffering a STEMI despite therapeutic anticoagulation. Although the exact nature of CAC remains to be worked out, it is possible that platelet agglutination/clumping seen on the peripheral blood smear is representative of in vivo activity and serves as a harbinger for worsening thrombosis. The frequency of such phenomenon and efficacy of further interventions has yet to be explored.

In late 2019 a new pandemic started in Wuhan, China, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) due to its similarities with the virus responsible for the SARS outbreak of 2003. The disease manifestations are named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or platelet clumping, visualized on the peripheral blood smear, is a common cause for artificial thrombocytopenia laboratory reporting and is frequently attributed to laboratory artifact. In this case presentation, a critically ill patient with COVID-19 developed pan-pseudothrombocytopenia (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], sodium citrate, and heparin tubes) just prior to his death from a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the setting of therapeutic anticoagulation during a prolonged hospitalization. This case raises the possibility that pseudothrombocytopenia in the setting of COVID-19 critical illness may represent an ominous feature of COVID-19-associated coagulopathy (CAC). Furthermore, it prompts the question whether pseudothrombocytopenia in this setting is representative of increased platelet aggregation activity in vivo.

Case Presentation

A 50-year-old African American man who was diagnosed with COVID-19 3 days prior to admission presented to the emergency department of the W.G. (Bill) Hefner VA Medical Center in Salisbury, North Carolina, with worsening dyspnea and fever. His primary chronic medical problems included obesity (body mass index, 33), type 2 diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c 2 months prior of 6.6%), migraine headaches, and obstructive sleep apnea. Shortly after presentation, his respiratory status declined, requiring intubation. He was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further management.

Notable findings at admission included > 20 mcg/mL FEU D-dimer (normal range, 0-0.56 mcg/mL FEU), 20.4 mg/dL C-reactive protein (normal range, < 1 mg/dL), 30 mm/h erythrocyte sedimentation rate (normal range, 0-25 mm/h), and 3.56 ng/mL procalcitonin (normal range, 0.05-1.99 ng/mL). Patient’s hemoglobin and platelet counts were normal. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was initiated with ceftriaxone (2 g IV daily) and doxycycline (100 mg IV twice daily) due to concern of superimposed infection in the setting of an elevated procalcitonin.

A heparin infusion was initiated (5,000 U IV bolus followed by continuous infusion with goal partial thromboplastin time [PTT] of 1.5x the upper limit of normal) on admission to treat CAC. Renal function worsened requiring intermittent renal replacement therapy on day 3. His lactate dehydrogenase was elevated to 1,188 U/L (normal range: 100-240 U/L) and ferritin was elevated to 2,603 ng/mL (normal range: 25-350 ng/mL) (Table). Initial neuromuscular blockade and prone positioning maneuvers were instituted to optimize oxygenation based on the latest literature for respiratory distress in the COVID-19 management.2

Intermittent norepinephrine infusion (5 mcg/min with a 2 mcg/min titration every 5 minutes as needed to maintain mean arterial pressure of > 65 mm Hg) was required for hemodynamic support throughout the patient’s course. Several therapies for COVID-19 were considered and were a reflection of the rapidly evolving literature during the care of patients with this disease. The patient originally received hydroxychloroquine (200 mg by mouth twice daily) in accordance with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) institutional protocol between day 2 and day 4; however, hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to concerns of QTc prolongation. The patient also received 1 unit of convalescent plasma on day 6 after being enrolled in the expanded access program.3 The patient was not a candidate for remdesivir due to his unstable renal function and need for vasopressors. Finally, interleukin-6 inhibitors also were considered; however, the risk of superimposed infection precluded its use.

On day 7 antimicrobial therapy was transitioned to linezolid (600 mg IV twice daily) due to the persistence of fever and a portable chest radiograph revealing diffuse infiltrates throughout the bilateral lungs, worse compared with prior radiograph on day 5, suggesting a worsening of pneumonia. On day 12, the patient was transitioned to cefepime (1 gram IV daily) to broaden antimicrobial coverage and was continued thereafter. Blood cultures were negative throughout his hospitalization.

Given his worsening clinical scenario there was a question about whether or not the patient was still shedding virus for prognostic and therapeutic implications. Therefore, his SARS-CoV-2 test by polymerase chain reaction nasopharyngeal was positive again on day 18. On day 20, the patient developed leukocytosis, his fever persisted, and a portable chest radiograph revealed extensive bilateral pulmonary opacities with focal worsening in left lower base. Due to this constellation of findings, a vancomycin IV (1,500 mg once) was started for empirical treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Sputum samples obtained on day 20 revealed Staphylococcus aureus on subsequent days.

From a hematologic perspective, on day 9 due to challenges to maintain a therapeutic level of anticoagulation with heparin infusion thought to be related to antithrombin deficiency, anticoagulation was changed to argatroban infusion (0.5 mcg/kg/min targeting a PTT of 70-105 seconds) for ongoing management of CAC. Although D-dimer was > 20 mcg/mL FEU on admission and on days 4 and 5, D-dimer trended down to 12.5 mcg/mL FEU on day 16.

Throughout the patient’s hospital stay, no significant bleeding was seen. Hemoglobin was 15.2 g/dL on admission, but anemia developed with a nadir of 6.5 g/dL, warranting transfusion of red blood cells on day 22. Platelet count was 165,000 per microliter on admission and remained within normal limits until platelet clumping was noted on day 15 laboratory collection.

Hematology was consulted on day 20 to obtain an accurate platelet count. A peripheral blood smear from a sodium citrate containing tube was remarkable for prominent platelet clumping, particularly at the periphery of the slide (Figure 1). Platelet clumping was reproduced in samples containing EDTA and heparin. Other features of the peripheral blood smear included the presence of echinocytes with rare schistocytes. To investigate for presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation on day 22, fibrinogen was found to be mildly elevated at 538 mg/dL (normal range: 243-517 mg/dL) and a D-dimer value of 11.96 mcg/mL FEU.

On day 22, the patient’s ventilator requirements escalated to requiring 100% FiO2 and 10 cm H20 of positive end-expiratory pressure with mean arterial pressures in the 50 to 60 mm Hg range. Within 30 minutes an electrocardiogram (EKG) obtained revealed a STEMI (Figure 2). Troponin was measured at 0.65 ng/mL (normal range: 0.02-0.06 ng/mL). Just after an EKG was performed, the patient developed a ventricular fibrillation arrest and was unable to obtain return of spontaneous circulation. The patient was pronounced dead. The family declined an autopsy.

Discussion

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or platelet clumping (agglutination), is estimated to be present in up to 2% of hospitalized patients.4 Pseudothrombocytopenia was found to be the root cause of thrombocytopenia hematology consultations in up to 4% of hospitalized patients.5 The etiology is commonly ascribed to EDTA inducing a conformational change in the GpIIb-IIIa platelet complex, rendering it susceptible to binding of autoantibodies, which cause subsequent platelet agglutination.6 In most cases (83%), the use of a non-EDTA anticoagulant, such as sodium citrate, resolves the platelet agglutination and allows for accurate platelet count reporting.4 Pseudothrombocytopenia in most cases is considered an in vitro finding without clinical relevance.7 However, in this patient’s case, his pan-pseudothrombocytopenia was temporally associated with an arterial occlusive event (STEMI) leading to his demise despite therapeutic anticoagulation in the setting of CAC. This temporal association raises the possibility that pseudothrombocytopenia seen on the peripheral blood smear is an accurate representation of in vivo activity.

Pseudothrombocytopenia has been associated with sepsis from bacterial and viral causes as well as autoimmune and medication effect.4,8-10 Li and colleagues reported transient EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with COVID-19 infection; however, platelet clumping resolved with use of a citrate tube, and the EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia phenomenon resolved with patient recovery.11 The frequency of COVID-19-related pseudothrombocytopenia is currently unknown.

Although the understanding of COVID-19-associated CAC continues to evolve, it seems that initial reports support the idea that hemostatic dysfunction tends to more thrombosis than to bleeding.12 Rather than overt disseminated intravascular coagulation with reduced fibrinogen and bleeding, CAC is more closely associated with blood clotting, as demonstrated by autopsy studies revealing microvascular thrombosis in the lungs.13 The D-dimer test has been identified as the most useful biomarker by the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis to screen for CAC and stratify patients who warrant admission or closer monitoring.12 Other identified features of CAC include prolonged prothrombin time and thrombocytopenia.12

There have been varying clinical approaches to CAC management. A retrospective review found that prophylactic heparin doses were associated with improved mortality in those with elevated D-dimer > 3.0 mg/L.14 There continues to be a diversity of varying clinical approaches with many medical centers advocating for an intensified prophylactic twice daily low molecular-weight heparin compared with others advocating for full therapeutic dose anticoagulation for patients with elevated D-dimer.15 This patient was treated aggressively with full-dose anticoagulation, and despite his having a down-trend in D-dimer, he suffered a lethal arterial thrombosis in the form of a STEMI.

Varatharajah and Rajah

Conclusions

This patient’s case highlights the presence of pan-pseudothrombocytopenia despite the use of a sodium citrate and heparin containing tube in a COVID-19 infection with multiorgan dysfunction. This developed 1 week prior to the patient suffering a STEMI despite therapeutic anticoagulation. Although the exact nature of CAC remains to be worked out, it is possible that platelet agglutination/clumping seen on the peripheral blood smear is representative of in vivo activity and serves as a harbinger for worsening thrombosis. The frequency of such phenomenon and efficacy of further interventions has yet to be explored.

1. World Health Organization. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(COVID-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it. Accessed July 15, 2020.

2. Ghelichkhani P, Esmaeili M. Prone position in management of COVID-19 patients; a commentary. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e48. Published 2020 April 11.

3. National Library of Medicine, Clinicaltrials.gov. Expanded access to convalescent plasma for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. NCT04338360. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/nct04338360. Update April 20, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020.

4. Tan GC, Stalling M, Dennis G, Nunez M, Kahwash SB. Pseudothrombocytopenia due to platelet clumping: a case report and brief review of the literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2016;2016:3036476. doi:10.1155/2016/3036476

5. Boxer M, Biuso TJ. Etiologies of thrombocytopenia in the community hospital: the experience of 1 hematologist. Am J Med. 2020;133(5):e183-e186. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.027

6. Fiorin F, Steffan A, Pradella P, Bizzaro N, Potenza R, De Angelis V. IgG platelet antibodies in EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia bind to platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110(2):178-183. doi:10.1093/ajcp/110.2.178

7. Nagler M, Keller P, Siegrist S, Alberio L. A case of EDTA-Dependent pseudothrombocytopenia: simple recognition of an underdiagnosed and misleading phenomenon. BMC Clin Pathol. 2014;14:19. doi:10.1186/1472-6890-14-19

8. Mori M, Kudo H, Yoshitake S, Ito K, Shinguu C, Noguchi T. Transient EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(2):218-220. doi:10.1007/s001340050050.

9. Choe W-H, Cho Y-U, Chae J-D, Kim S-H. 2013. Pseudothrombocytopenia or platelet clumping as a possible cause of low platelet count in patients with viral infection: a case series from single institution focusing on hepatitis A virus infection. Int J Lab Hematol. 2013;35(1):70-76. doi:10.1111/j.1751-553x.2012.01466.

10. Hsieh AT, Chao TY, Chen YC. Pseudothrombocytopenia associated with infectious mononucleosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127(1):e17-e18. doi:10.1043/0003-9985(2003)1272.0.CO;2

11. Li H, Wang B, Ning L, Luo Y, Xiang S. Transient appearance of EDTA dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 5]. Platelets. 2020;1-2. doi:10.1080/09537104.2020.1760231

12. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023-1026. doi:10.1111/jth.14810

13. Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

14. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094-1099. doi:10.1111/jth.14817

15. Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;125(23):2033-2040. doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020006000.

16. Varatharajah N, Rajah S. Microthrombotic complications of COVID-19 are likely due to embolism of circulating endothelial derived ultralarge von Willebrand factor (eULVWF) Decorated-Platelet Strings. Fed Pract. 2020;37(6):258-259. doi:10.12788/fp.0001

17. Bernardo A, Ball C, Nolasco L, Choi H, Moake JL, Dong JF. Platelets adhered to endothelial cell-bound ultra-large von Willebrand factor strings support leukocyte tethering and rolling under high shear stress. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(3):562-570. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01122.x

1. World Health Organization. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(COVID-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it. Accessed July 15, 2020.

2. Ghelichkhani P, Esmaeili M. Prone position in management of COVID-19 patients; a commentary. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e48. Published 2020 April 11.

3. National Library of Medicine, Clinicaltrials.gov. Expanded access to convalescent plasma for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. NCT04338360. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/nct04338360. Update April 20, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020.

4. Tan GC, Stalling M, Dennis G, Nunez M, Kahwash SB. Pseudothrombocytopenia due to platelet clumping: a case report and brief review of the literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2016;2016:3036476. doi:10.1155/2016/3036476

5. Boxer M, Biuso TJ. Etiologies of thrombocytopenia in the community hospital: the experience of 1 hematologist. Am J Med. 2020;133(5):e183-e186. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.027

6. Fiorin F, Steffan A, Pradella P, Bizzaro N, Potenza R, De Angelis V. IgG platelet antibodies in EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia bind to platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110(2):178-183. doi:10.1093/ajcp/110.2.178

7. Nagler M, Keller P, Siegrist S, Alberio L. A case of EDTA-Dependent pseudothrombocytopenia: simple recognition of an underdiagnosed and misleading phenomenon. BMC Clin Pathol. 2014;14:19. doi:10.1186/1472-6890-14-19

8. Mori M, Kudo H, Yoshitake S, Ito K, Shinguu C, Noguchi T. Transient EDTA-dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(2):218-220. doi:10.1007/s001340050050.

9. Choe W-H, Cho Y-U, Chae J-D, Kim S-H. 2013. Pseudothrombocytopenia or platelet clumping as a possible cause of low platelet count in patients with viral infection: a case series from single institution focusing on hepatitis A virus infection. Int J Lab Hematol. 2013;35(1):70-76. doi:10.1111/j.1751-553x.2012.01466.

10. Hsieh AT, Chao TY, Chen YC. Pseudothrombocytopenia associated with infectious mononucleosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127(1):e17-e18. doi:10.1043/0003-9985(2003)1272.0.CO;2

11. Li H, Wang B, Ning L, Luo Y, Xiang S. Transient appearance of EDTA dependent pseudothrombocytopenia in a patient with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 5]. Platelets. 2020;1-2. doi:10.1080/09537104.2020.1760231

12. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023-1026. doi:10.1111/jth.14810

13. Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

14. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094-1099. doi:10.1111/jth.14817

15. Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;125(23):2033-2040. doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020006000.

16. Varatharajah N, Rajah S. Microthrombotic complications of COVID-19 are likely due to embolism of circulating endothelial derived ultralarge von Willebrand factor (eULVWF) Decorated-Platelet Strings. Fed Pract. 2020;37(6):258-259. doi:10.12788/fp.0001

17. Bernardo A, Ball C, Nolasco L, Choi H, Moake JL, Dong JF. Platelets adhered to endothelial cell-bound ultra-large von Willebrand factor strings support leukocyte tethering and rolling under high shear stress. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(3):562-570. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01122.x

Antibiotic resistance: Personal responsibility in somewhat short supply

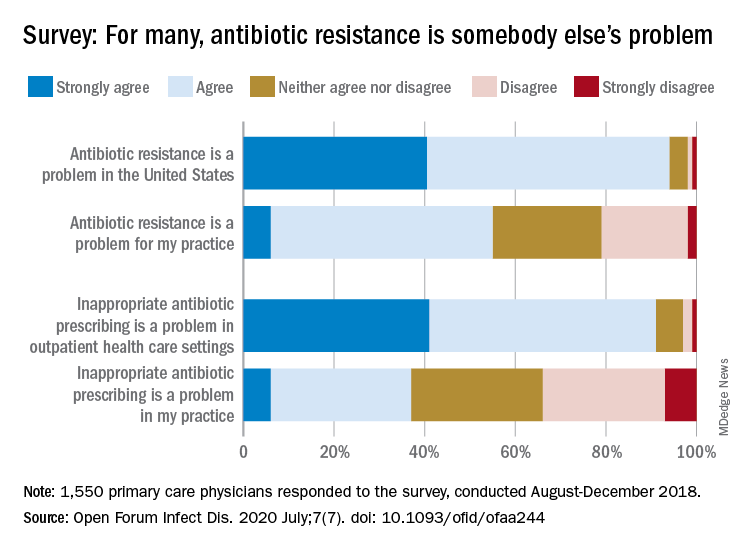

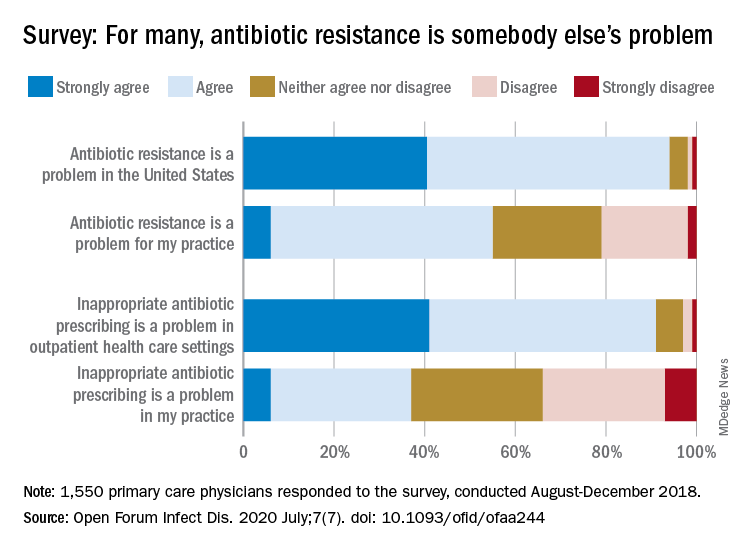

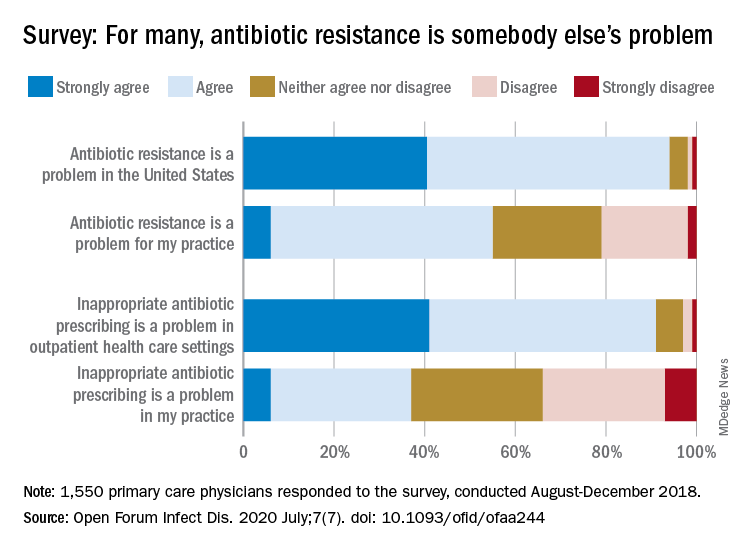

Most primary care physicians agree that antibiotic resistance and inappropriate prescribing are problems in the United States, but they are much less inclined to recognize these issues in their own practices, according to the results of a nationwide survey.

Rachel M. Zetts, MPH, of the Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, D.C., and associates wrote in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

Almost all (94%) of the 1,550 internists, family physicians, and pediatricians who responded to the survey said that antibiotic resistance is a national problem, and nearly that many (91%) agreed that “inappropriate antibiotic prescribing is a problem in outpatient health care settings,” the investigators acknowledged.

Narrowing the focus to their own practices, however, changed some opinions. At that level, only 55% of the respondents said that resistance was a problem for their practices, and just 37% said that there any sort of inappropriate prescribing going on, based on data from the survey, which was conducted from August to October 2018 by Pew and the American Medical Association.

Antibiotic stewardship, defined as activities meant to ensure appropriate prescribing of antibiotics, should include “staff and patient education, clinician-level antibiotic prescribing feedback, and communications training on how to discuss antibiotic prescribing with patients,” Ms. Zetts and associates explained.

The need for such stewardship in health care settings was acknowledged by 72% of respondents, but 53% of those surveyed also said that all they need to do to support such efforts “is to talk with their patients about the value of an antibiotic for their symptoms,” they noted.

The bacteria, it seems, are not the only ones with some resistance. Half of the primary care physicians believe that it would be difficult to fairly and accurately track the appropriate use of antibiotics, and 52% agreed with the statement that “practice-based reporting requirements for antibiotic use would be too onerous,” the researchers pointed out.

“Antibiotic resistance is an impending public health crisis. We are seeing today, as we respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, what our health system looks like with no or limited treatments available to tackle an outbreak. … We must all remain vigilant in combating the spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria and be prudent when prescribing antibiotics,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a written statement.

SOURCE: Zetts RM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 July;7(7). doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa244.

Most primary care physicians agree that antibiotic resistance and inappropriate prescribing are problems in the United States, but they are much less inclined to recognize these issues in their own practices, according to the results of a nationwide survey.

Rachel M. Zetts, MPH, of the Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, D.C., and associates wrote in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

Almost all (94%) of the 1,550 internists, family physicians, and pediatricians who responded to the survey said that antibiotic resistance is a national problem, and nearly that many (91%) agreed that “inappropriate antibiotic prescribing is a problem in outpatient health care settings,” the investigators acknowledged.

Narrowing the focus to their own practices, however, changed some opinions. At that level, only 55% of the respondents said that resistance was a problem for their practices, and just 37% said that there any sort of inappropriate prescribing going on, based on data from the survey, which was conducted from August to October 2018 by Pew and the American Medical Association.

Antibiotic stewardship, defined as activities meant to ensure appropriate prescribing of antibiotics, should include “staff and patient education, clinician-level antibiotic prescribing feedback, and communications training on how to discuss antibiotic prescribing with patients,” Ms. Zetts and associates explained.

The need for such stewardship in health care settings was acknowledged by 72% of respondents, but 53% of those surveyed also said that all they need to do to support such efforts “is to talk with their patients about the value of an antibiotic for their symptoms,” they noted.

The bacteria, it seems, are not the only ones with some resistance. Half of the primary care physicians believe that it would be difficult to fairly and accurately track the appropriate use of antibiotics, and 52% agreed with the statement that “practice-based reporting requirements for antibiotic use would be too onerous,” the researchers pointed out.

“Antibiotic resistance is an impending public health crisis. We are seeing today, as we respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, what our health system looks like with no or limited treatments available to tackle an outbreak. … We must all remain vigilant in combating the spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria and be prudent when prescribing antibiotics,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a written statement.

SOURCE: Zetts RM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 July;7(7). doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa244.

Most primary care physicians agree that antibiotic resistance and inappropriate prescribing are problems in the United States, but they are much less inclined to recognize these issues in their own practices, according to the results of a nationwide survey.

Rachel M. Zetts, MPH, of the Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, D.C., and associates wrote in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

Almost all (94%) of the 1,550 internists, family physicians, and pediatricians who responded to the survey said that antibiotic resistance is a national problem, and nearly that many (91%) agreed that “inappropriate antibiotic prescribing is a problem in outpatient health care settings,” the investigators acknowledged.

Narrowing the focus to their own practices, however, changed some opinions. At that level, only 55% of the respondents said that resistance was a problem for their practices, and just 37% said that there any sort of inappropriate prescribing going on, based on data from the survey, which was conducted from August to October 2018 by Pew and the American Medical Association.

Antibiotic stewardship, defined as activities meant to ensure appropriate prescribing of antibiotics, should include “staff and patient education, clinician-level antibiotic prescribing feedback, and communications training on how to discuss antibiotic prescribing with patients,” Ms. Zetts and associates explained.

The need for such stewardship in health care settings was acknowledged by 72% of respondents, but 53% of those surveyed also said that all they need to do to support such efforts “is to talk with their patients about the value of an antibiotic for their symptoms,” they noted.

The bacteria, it seems, are not the only ones with some resistance. Half of the primary care physicians believe that it would be difficult to fairly and accurately track the appropriate use of antibiotics, and 52% agreed with the statement that “practice-based reporting requirements for antibiotic use would be too onerous,” the researchers pointed out.

“Antibiotic resistance is an impending public health crisis. We are seeing today, as we respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, what our health system looks like with no or limited treatments available to tackle an outbreak. … We must all remain vigilant in combating the spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria and be prudent when prescribing antibiotics,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a written statement.

SOURCE: Zetts RM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 July;7(7). doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa244.

FROM OPEN FORUM INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Guidance covers glycemia in dexamethasone-treated COVID-19 patients

New guidance from the U.K. National Diabetes COVID-19 Response Group addresses glucose management in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving dexamethasone therapy.

Although there are already guidelines that address inpatient management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia, the authors of the new document wrote that this new expert opinion paper was needed “given the ‘triple insult’ of dexamethasone-induced–impaired glucose metabolism, COVID-19–induced insulin resistance, and COVID-19–impaired insulin production.”

RECOVERY trial spurs response

The document, which is the latest in a series from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists, was published online Aug. 2 in Diabetic Medicine. The group is chaired by Gerry Rayman, MD, consultant physician at the diabetes centre and diabetes research unit, East Suffolk (England) and North East NHS Foundation Trust.

The guidance was developed in response to the recent “breakthrough” Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, which showed that dexamethasone reduced deaths in patients with COVID-19 on ventilators or receiving oxygen therapy. The advice is not intended for critical care units but can be adapted for that use.

The dose used in RECOVERY – 6 mg daily for 10 days – is 400%-500% greater than the therapeutic glucocorticoid replacement dose. High glucocorticoid doses can exacerbate hyperglycemia in people with established diabetes, unmask undiagnosed diabetes, precipitate hyperglycemia or new-onset diabetes, and can also cause hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), the authors explained.

They recommended a target glucose of 6.0-10.0 mmol/L (108-180 mg/dL), although they say up to 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) is “acceptable.” They then gave advice on frequency of monitoring for people with and without known diabetes, exclusion of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS, correction of initial hyperglycemia and maintenance of glycemic control using subcutaneous insulin, and prevention of hypoglycemia at the end of dexamethasone therapy (day 10) with insulin down-titration, discharge, and follow-up.

The detailed insulin guidance covers dose escalation for both insulin-treated and insulin-naive patients. A table suggests increasing correction doses of rapid-acting insulin based on prior total daily dose or weight.

Use of once- or twice-daily NPH insulin is recommended for patients whose glucose has risen above 12 mmol/L, in some cases with the addition of a long-acting analog. A second chart gives dose adjustments for those insulins. Additional guidance addresses patients on insulin pumps.

Guidance useful for U.S. physicians

Francisco Pasquel, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that he believes the guidance is “acceptable” for worldwide use, and that “it’s coherent and consistent with what we typically do.”

However, Dr. Pasquel, who founded COVID-in-Diabetes, an online repository of published guidance and shared experience – to which this new document has now been added – did take issue with one piece of advice. The guidance says that patients already taking premixed insulin formulations can continue using them while increasing the dose by 20%-40%. Given the risk of hypoglycemia associated with those formulations, Dr. Pasquel said he would switch those patients to NPH during the time that they’re on dexamethasone.

He also noted that the rapid-acting insulin dose range of 2-10 units provided in the first table, for correction of initial hyperglycemia, are more conservative than those used at his hospital, where correction doses of up to 14-16 units are sometimes necessary.

But Dr. Pasquel praised the group’s overall efforts since the pandemic began, noting that “they’re very organized and constantly updating their recommendations. They have a unified system in the [National Health Service], so it’s easier to standardize. They have a unique [electronic health record] which is far superior to what we do from a public health perspective.”

Dr. Rayman reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pasquel reported receiving research funding from Dexcom, Merck, and the National Institutes of Health, and consulting for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New guidance from the U.K. National Diabetes COVID-19 Response Group addresses glucose management in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving dexamethasone therapy.

Although there are already guidelines that address inpatient management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia, the authors of the new document wrote that this new expert opinion paper was needed “given the ‘triple insult’ of dexamethasone-induced–impaired glucose metabolism, COVID-19–induced insulin resistance, and COVID-19–impaired insulin production.”

RECOVERY trial spurs response

The document, which is the latest in a series from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists, was published online Aug. 2 in Diabetic Medicine. The group is chaired by Gerry Rayman, MD, consultant physician at the diabetes centre and diabetes research unit, East Suffolk (England) and North East NHS Foundation Trust.

The guidance was developed in response to the recent “breakthrough” Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, which showed that dexamethasone reduced deaths in patients with COVID-19 on ventilators or receiving oxygen therapy. The advice is not intended for critical care units but can be adapted for that use.

The dose used in RECOVERY – 6 mg daily for 10 days – is 400%-500% greater than the therapeutic glucocorticoid replacement dose. High glucocorticoid doses can exacerbate hyperglycemia in people with established diabetes, unmask undiagnosed diabetes, precipitate hyperglycemia or new-onset diabetes, and can also cause hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), the authors explained.

They recommended a target glucose of 6.0-10.0 mmol/L (108-180 mg/dL), although they say up to 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) is “acceptable.” They then gave advice on frequency of monitoring for people with and without known diabetes, exclusion of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS, correction of initial hyperglycemia and maintenance of glycemic control using subcutaneous insulin, and prevention of hypoglycemia at the end of dexamethasone therapy (day 10) with insulin down-titration, discharge, and follow-up.

The detailed insulin guidance covers dose escalation for both insulin-treated and insulin-naive patients. A table suggests increasing correction doses of rapid-acting insulin based on prior total daily dose or weight.

Use of once- or twice-daily NPH insulin is recommended for patients whose glucose has risen above 12 mmol/L, in some cases with the addition of a long-acting analog. A second chart gives dose adjustments for those insulins. Additional guidance addresses patients on insulin pumps.

Guidance useful for U.S. physicians

Francisco Pasquel, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that he believes the guidance is “acceptable” for worldwide use, and that “it’s coherent and consistent with what we typically do.”

However, Dr. Pasquel, who founded COVID-in-Diabetes, an online repository of published guidance and shared experience – to which this new document has now been added – did take issue with one piece of advice. The guidance says that patients already taking premixed insulin formulations can continue using them while increasing the dose by 20%-40%. Given the risk of hypoglycemia associated with those formulations, Dr. Pasquel said he would switch those patients to NPH during the time that they’re on dexamethasone.

He also noted that the rapid-acting insulin dose range of 2-10 units provided in the first table, for correction of initial hyperglycemia, are more conservative than those used at his hospital, where correction doses of up to 14-16 units are sometimes necessary.

But Dr. Pasquel praised the group’s overall efforts since the pandemic began, noting that “they’re very organized and constantly updating their recommendations. They have a unified system in the [National Health Service], so it’s easier to standardize. They have a unique [electronic health record] which is far superior to what we do from a public health perspective.”

Dr. Rayman reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pasquel reported receiving research funding from Dexcom, Merck, and the National Institutes of Health, and consulting for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New guidance from the U.K. National Diabetes COVID-19 Response Group addresses glucose management in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving dexamethasone therapy.

Although there are already guidelines that address inpatient management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia, the authors of the new document wrote that this new expert opinion paper was needed “given the ‘triple insult’ of dexamethasone-induced–impaired glucose metabolism, COVID-19–induced insulin resistance, and COVID-19–impaired insulin production.”

RECOVERY trial spurs response

The document, which is the latest in a series from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists, was published online Aug. 2 in Diabetic Medicine. The group is chaired by Gerry Rayman, MD, consultant physician at the diabetes centre and diabetes research unit, East Suffolk (England) and North East NHS Foundation Trust.

The guidance was developed in response to the recent “breakthrough” Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, which showed that dexamethasone reduced deaths in patients with COVID-19 on ventilators or receiving oxygen therapy. The advice is not intended for critical care units but can be adapted for that use.

The dose used in RECOVERY – 6 mg daily for 10 days – is 400%-500% greater than the therapeutic glucocorticoid replacement dose. High glucocorticoid doses can exacerbate hyperglycemia in people with established diabetes, unmask undiagnosed diabetes, precipitate hyperglycemia or new-onset diabetes, and can also cause hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), the authors explained.

They recommended a target glucose of 6.0-10.0 mmol/L (108-180 mg/dL), although they say up to 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) is “acceptable.” They then gave advice on frequency of monitoring for people with and without known diabetes, exclusion of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS, correction of initial hyperglycemia and maintenance of glycemic control using subcutaneous insulin, and prevention of hypoglycemia at the end of dexamethasone therapy (day 10) with insulin down-titration, discharge, and follow-up.

The detailed insulin guidance covers dose escalation for both insulin-treated and insulin-naive patients. A table suggests increasing correction doses of rapid-acting insulin based on prior total daily dose or weight.

Use of once- or twice-daily NPH insulin is recommended for patients whose glucose has risen above 12 mmol/L, in some cases with the addition of a long-acting analog. A second chart gives dose adjustments for those insulins. Additional guidance addresses patients on insulin pumps.

Guidance useful for U.S. physicians

Francisco Pasquel, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that he believes the guidance is “acceptable” for worldwide use, and that “it’s coherent and consistent with what we typically do.”

However, Dr. Pasquel, who founded COVID-in-Diabetes, an online repository of published guidance and shared experience – to which this new document has now been added – did take issue with one piece of advice. The guidance says that patients already taking premixed insulin formulations can continue using them while increasing the dose by 20%-40%. Given the risk of hypoglycemia associated with those formulations, Dr. Pasquel said he would switch those patients to NPH during the time that they’re on dexamethasone.

He also noted that the rapid-acting insulin dose range of 2-10 units provided in the first table, for correction of initial hyperglycemia, are more conservative than those used at his hospital, where correction doses of up to 14-16 units are sometimes necessary.

But Dr. Pasquel praised the group’s overall efforts since the pandemic began, noting that “they’re very organized and constantly updating their recommendations. They have a unified system in the [National Health Service], so it’s easier to standardize. They have a unique [electronic health record] which is far superior to what we do from a public health perspective.”

Dr. Rayman reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pasquel reported receiving research funding from Dexcom, Merck, and the National Institutes of Health, and consulting for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Study: Immune checkpoint inhibitors don’t increase risk of death in cancer patients with COVID-19

The study included 113 cancer patients who had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 within 12 months of receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The patients did not receive chemotherapy within 3 months of testing positive for COVID-19.

In all, 33 patients were admitted to the hospital, including 6 who were admitted to the ICU, and 9 patients died.

“Nine out of 113 patients is a mortality rate of 8%, which is in the middle of the earlier reported rates for cancer patients in general [7.6%-12%],” said Aljosja Rogiers, MD, PhD, of the Melanoma Institute Australia in Sydney.

COVID-19 was the primary cause of death in seven of the patients, including three of those who were admitted to the ICU, Dr. Rogiers noted.

He reported these results during the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

Study details

Patients in this study were treated at 19 hospitals in North America, Europe, and Australia, and the data cutoff was May 15, 2020. Most patients (64%) were treated in Europe, which was the epicenter for the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of data collection, Dr. Rogiers noted. A third of patients were in North America, and 3% were in Australia.

The patients’ median age was 63 years (range, 27-86 years). Most patients were men (65%), and most had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance scores of 0-1 (90%).

The most common malignancies were melanoma (57%), non–small cell lung cancer (17%), and renal cell carcinoma (9%). Treatment was for early cancer in 26% of patients and for advanced cancer in 74%. Comorbidities included cardiovascular disease in 27% of patients, diabetes in 15%, pulmonary disease in 12%, and renal disease in 5%.

Immunosuppressive therapy equivalent to a prednisone dose of 10 mg or greater daily was given in 13% of patients, and other immunosuppressive therapies, such as infliximab, were given in 3%.

Among the 60% of patients with COVID-19 symptoms, 68% had fever, 59% had cough, 34% had dyspnea, and 15% had myalgia. Most of the 40% of asymptomatic patients were tested because they had COVID-19–positive contact, Dr. Rogiers noted.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment included monotherapy with a programmed death–1/PD–ligand 1 inhibitor in 82% of patients, combination anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA4 therapy in 13%, and other therapy – usually a checkpoint inhibitor combined with a different type of targeted agent – in 5%.

At the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, 30% of patients had achieved a partial response, complete response, or had no evidence of disease, 18% had stable disease, and 15% had progression. Response data were not available in 37% of cases, usually because treatment was only recently started prior to COVID-19 diagnosis, Dr. Rogiers said.

Treatments administered for COVID-19 included antibiotic therapy in 25% of patients, oxygen therapy in 20%, glucocorticoids in 10%, antiviral drugs in 6%, and intravenous immunoglobulin or anti–interleukin-6 in 2% each.

Among patients admitted to the ICU, 3% required mechanical ventilation, 2% had vasopressin, and 1% received renal replacement therapy.

At the data cutoff, 20 of 33 hospitalized patients (61%) had been discharged, and 4 (12%) were still in the hospital.

Mortality results

Nine patients died. The rate of death was 8% overall and 27% among hospitalized patients.

“The mortality rate of COVID-19 in the general population without comorbidities is about 1.4%,” Dr. Rogiers said. “For cancer patients, this is reported to be in the range of 7.6%-12%. To what extent patients on immune checkpoint inhibition are at a higher risk of mortality is currently unknown.”

Theoretically, immune checkpoint inhibition could either mitigate or exacerbate COVID-19 infection. It has been hypothesized that immune checkpoint inhibitors could increase the risk of severe acute lung injury or other complications of COVID-19, Dr. Rogiers said, explaining the rationale for the study.

The study shows that the patients who died had a median age of 72 years (range, 49-81 years), which is slightly higher than the median overall age of 63 years. Six patients were from North America, and three were from Italy.

“Two melanoma patients and two non–small cell lung cancer patients died,” Dr. Rogiers said. He noted that two other deaths were in patients with renal cell carcinoma, and three deaths were in other cancer types. All patients had advanced or metastatic disease.

Given that 57% of patients in the study had melanoma and 17% had NSCLC, this finding may indicate that COVID-19 has a slightly higher mortality rate in NSCLC patients than in melanoma patients, but the numbers are small, Dr. Rogiers said.

Notably, six of the patients who died were not admitted to the ICU. In four cases, this was because of underlying malignancy; in the other two cases, it was because of a constrained health care system, Dr. Rogiers said.

Overall, the findings show that the mortality rate of patients with COVID-19 and cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors is similar to the mortality rate reported in the general cancer population, Dr. Rogiers said.

“Treatment with immune checkpoint inhibition does not seem to pose an additional mortality risk for cancer patients with COVID-19,” he concluded.

Dr. Rogiers reported having no conflicts of interest. There was no funding disclosed for the study.

SOURCE: Rogiers A et al. AACR: COVID-19 and Cancer, Abstract S02-01.

The study included 113 cancer patients who had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 within 12 months of receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The patients did not receive chemotherapy within 3 months of testing positive for COVID-19.

In all, 33 patients were admitted to the hospital, including 6 who were admitted to the ICU, and 9 patients died.

“Nine out of 113 patients is a mortality rate of 8%, which is in the middle of the earlier reported rates for cancer patients in general [7.6%-12%],” said Aljosja Rogiers, MD, PhD, of the Melanoma Institute Australia in Sydney.

COVID-19 was the primary cause of death in seven of the patients, including three of those who were admitted to the ICU, Dr. Rogiers noted.

He reported these results during the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

Study details

Patients in this study were treated at 19 hospitals in North America, Europe, and Australia, and the data cutoff was May 15, 2020. Most patients (64%) were treated in Europe, which was the epicenter for the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of data collection, Dr. Rogiers noted. A third of patients were in North America, and 3% were in Australia.

The patients’ median age was 63 years (range, 27-86 years). Most patients were men (65%), and most had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance scores of 0-1 (90%).

The most common malignancies were melanoma (57%), non–small cell lung cancer (17%), and renal cell carcinoma (9%). Treatment was for early cancer in 26% of patients and for advanced cancer in 74%. Comorbidities included cardiovascular disease in 27% of patients, diabetes in 15%, pulmonary disease in 12%, and renal disease in 5%.

Immunosuppressive therapy equivalent to a prednisone dose of 10 mg or greater daily was given in 13% of patients, and other immunosuppressive therapies, such as infliximab, were given in 3%.

Among the 60% of patients with COVID-19 symptoms, 68% had fever, 59% had cough, 34% had dyspnea, and 15% had myalgia. Most of the 40% of asymptomatic patients were tested because they had COVID-19–positive contact, Dr. Rogiers noted.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment included monotherapy with a programmed death–1/PD–ligand 1 inhibitor in 82% of patients, combination anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA4 therapy in 13%, and other therapy – usually a checkpoint inhibitor combined with a different type of targeted agent – in 5%.

At the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, 30% of patients had achieved a partial response, complete response, or had no evidence of disease, 18% had stable disease, and 15% had progression. Response data were not available in 37% of cases, usually because treatment was only recently started prior to COVID-19 diagnosis, Dr. Rogiers said.

Treatments administered for COVID-19 included antibiotic therapy in 25% of patients, oxygen therapy in 20%, glucocorticoids in 10%, antiviral drugs in 6%, and intravenous immunoglobulin or anti–interleukin-6 in 2% each.

Among patients admitted to the ICU, 3% required mechanical ventilation, 2% had vasopressin, and 1% received renal replacement therapy.

At the data cutoff, 20 of 33 hospitalized patients (61%) had been discharged, and 4 (12%) were still in the hospital.

Mortality results

Nine patients died. The rate of death was 8% overall and 27% among hospitalized patients.

“The mortality rate of COVID-19 in the general population without comorbidities is about 1.4%,” Dr. Rogiers said. “For cancer patients, this is reported to be in the range of 7.6%-12%. To what extent patients on immune checkpoint inhibition are at a higher risk of mortality is currently unknown.”

Theoretically, immune checkpoint inhibition could either mitigate or exacerbate COVID-19 infection. It has been hypothesized that immune checkpoint inhibitors could increase the risk of severe acute lung injury or other complications of COVID-19, Dr. Rogiers said, explaining the rationale for the study.

The study shows that the patients who died had a median age of 72 years (range, 49-81 years), which is slightly higher than the median overall age of 63 years. Six patients were from North America, and three were from Italy.

“Two melanoma patients and two non–small cell lung cancer patients died,” Dr. Rogiers said. He noted that two other deaths were in patients with renal cell carcinoma, and three deaths were in other cancer types. All patients had advanced or metastatic disease.

Given that 57% of patients in the study had melanoma and 17% had NSCLC, this finding may indicate that COVID-19 has a slightly higher mortality rate in NSCLC patients than in melanoma patients, but the numbers are small, Dr. Rogiers said.

Notably, six of the patients who died were not admitted to the ICU. In four cases, this was because of underlying malignancy; in the other two cases, it was because of a constrained health care system, Dr. Rogiers said.

Overall, the findings show that the mortality rate of patients with COVID-19 and cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors is similar to the mortality rate reported in the general cancer population, Dr. Rogiers said.

“Treatment with immune checkpoint inhibition does not seem to pose an additional mortality risk for cancer patients with COVID-19,” he concluded.

Dr. Rogiers reported having no conflicts of interest. There was no funding disclosed for the study.

SOURCE: Rogiers A et al. AACR: COVID-19 and Cancer, Abstract S02-01.

The study included 113 cancer patients who had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 within 12 months of receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The patients did not receive chemotherapy within 3 months of testing positive for COVID-19.

In all, 33 patients were admitted to the hospital, including 6 who were admitted to the ICU, and 9 patients died.

“Nine out of 113 patients is a mortality rate of 8%, which is in the middle of the earlier reported rates for cancer patients in general [7.6%-12%],” said Aljosja Rogiers, MD, PhD, of the Melanoma Institute Australia in Sydney.

COVID-19 was the primary cause of death in seven of the patients, including three of those who were admitted to the ICU, Dr. Rogiers noted.

He reported these results during the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

Study details

Patients in this study were treated at 19 hospitals in North America, Europe, and Australia, and the data cutoff was May 15, 2020. Most patients (64%) were treated in Europe, which was the epicenter for the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of data collection, Dr. Rogiers noted. A third of patients were in North America, and 3% were in Australia.

The patients’ median age was 63 years (range, 27-86 years). Most patients were men (65%), and most had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance scores of 0-1 (90%).

The most common malignancies were melanoma (57%), non–small cell lung cancer (17%), and renal cell carcinoma (9%). Treatment was for early cancer in 26% of patients and for advanced cancer in 74%. Comorbidities included cardiovascular disease in 27% of patients, diabetes in 15%, pulmonary disease in 12%, and renal disease in 5%.

Immunosuppressive therapy equivalent to a prednisone dose of 10 mg or greater daily was given in 13% of patients, and other immunosuppressive therapies, such as infliximab, were given in 3%.

Among the 60% of patients with COVID-19 symptoms, 68% had fever, 59% had cough, 34% had dyspnea, and 15% had myalgia. Most of the 40% of asymptomatic patients were tested because they had COVID-19–positive contact, Dr. Rogiers noted.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment included monotherapy with a programmed death–1/PD–ligand 1 inhibitor in 82% of patients, combination anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA4 therapy in 13%, and other therapy – usually a checkpoint inhibitor combined with a different type of targeted agent – in 5%.

At the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, 30% of patients had achieved a partial response, complete response, or had no evidence of disease, 18% had stable disease, and 15% had progression. Response data were not available in 37% of cases, usually because treatment was only recently started prior to COVID-19 diagnosis, Dr. Rogiers said.