User login

Labial growth

White-to-pink friable plaques occurring acutely in the vulva is concerning for one form of secondary syphilis that affects mucous membranes: condyloma lata.

Known as the great imitator for its variety of clinical presentations, syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Three to 10 days following contact with the spirochete, a painless ulcer or chancre forms and subsequently resolves—sometimes without notice.

Secondary syphilis develops from hematogenous spread of bacteria taking many forms—most commonly a widespread rash over the whole body of many (although sometimes faint) macules or papules up to about 1 cm in size and haphazardly spread out about every 1 cm. Palms and soles may be affected, even if faintly. Another, less common form of secondary syphilis includes the friable plaques (often in the anogenital area, as pictured) that are highly concentrated with bacteria. These occur 3 to 12 weeks after the appearance of a primary chancre and are variably symptomatic.

The differential diagnosis includes genital warts, vulvar carcinoma, and pemphigus vegetans. The relatively rapid, multifocal presentation helps to separate this disorder from vulvar carcinoma. A biopsy can distinguish the 2. However, diagnosis is better made with serology using nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Treponemal tests (assaying immunoglobulin [Ig]M and IgG to Treponema pallidum) are also an option and are very specific. Following this, an RPR titer can help guide treatment. Darkfield microscopy, which can reveal spirochetes directly, isn’t readily available but could be used to diagnose condyloma lata.

Patients who have been given a diagnosis of syphilis should be offered screening for other STIs, including HIV. Anyone who has had sexual contact with the patient within the previous 90 days should be notified, tested, and treated. Patients with primary or secondary syphilis should be treated with 2.4 million units of intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G in a single dose—regardless of whether they test positive for HIV. To exclude tertiary syphilis, a careful neurologic exam should take place at the time of diagnosis and again 6 and 12 months after treatment (sooner if follow-up may be uncertain). Consider treatment failure if RPR titers haven’t fallen fourfold in 12 months. In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a notice that COVID-19-vaccinated patients may have false-positive RPR titers performed from Bio-Rad Laboratories (BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR kit).1

In this case, the patient tested positive for treponemal antibodies and had an RPR titer of 1:128. She was treated with IM benzathine penicillin with lasting clearance.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infection Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Reviewed December 22, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm

White-to-pink friable plaques occurring acutely in the vulva is concerning for one form of secondary syphilis that affects mucous membranes: condyloma lata.

Known as the great imitator for its variety of clinical presentations, syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Three to 10 days following contact with the spirochete, a painless ulcer or chancre forms and subsequently resolves—sometimes without notice.

Secondary syphilis develops from hematogenous spread of bacteria taking many forms—most commonly a widespread rash over the whole body of many (although sometimes faint) macules or papules up to about 1 cm in size and haphazardly spread out about every 1 cm. Palms and soles may be affected, even if faintly. Another, less common form of secondary syphilis includes the friable plaques (often in the anogenital area, as pictured) that are highly concentrated with bacteria. These occur 3 to 12 weeks after the appearance of a primary chancre and are variably symptomatic.

The differential diagnosis includes genital warts, vulvar carcinoma, and pemphigus vegetans. The relatively rapid, multifocal presentation helps to separate this disorder from vulvar carcinoma. A biopsy can distinguish the 2. However, diagnosis is better made with serology using nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Treponemal tests (assaying immunoglobulin [Ig]M and IgG to Treponema pallidum) are also an option and are very specific. Following this, an RPR titer can help guide treatment. Darkfield microscopy, which can reveal spirochetes directly, isn’t readily available but could be used to diagnose condyloma lata.

Patients who have been given a diagnosis of syphilis should be offered screening for other STIs, including HIV. Anyone who has had sexual contact with the patient within the previous 90 days should be notified, tested, and treated. Patients with primary or secondary syphilis should be treated with 2.4 million units of intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G in a single dose—regardless of whether they test positive for HIV. To exclude tertiary syphilis, a careful neurologic exam should take place at the time of diagnosis and again 6 and 12 months after treatment (sooner if follow-up may be uncertain). Consider treatment failure if RPR titers haven’t fallen fourfold in 12 months. In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a notice that COVID-19-vaccinated patients may have false-positive RPR titers performed from Bio-Rad Laboratories (BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR kit).1

In this case, the patient tested positive for treponemal antibodies and had an RPR titer of 1:128. She was treated with IM benzathine penicillin with lasting clearance.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

White-to-pink friable plaques occurring acutely in the vulva is concerning for one form of secondary syphilis that affects mucous membranes: condyloma lata.

Known as the great imitator for its variety of clinical presentations, syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Three to 10 days following contact with the spirochete, a painless ulcer or chancre forms and subsequently resolves—sometimes without notice.

Secondary syphilis develops from hematogenous spread of bacteria taking many forms—most commonly a widespread rash over the whole body of many (although sometimes faint) macules or papules up to about 1 cm in size and haphazardly spread out about every 1 cm. Palms and soles may be affected, even if faintly. Another, less common form of secondary syphilis includes the friable plaques (often in the anogenital area, as pictured) that are highly concentrated with bacteria. These occur 3 to 12 weeks after the appearance of a primary chancre and are variably symptomatic.

The differential diagnosis includes genital warts, vulvar carcinoma, and pemphigus vegetans. The relatively rapid, multifocal presentation helps to separate this disorder from vulvar carcinoma. A biopsy can distinguish the 2. However, diagnosis is better made with serology using nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Treponemal tests (assaying immunoglobulin [Ig]M and IgG to Treponema pallidum) are also an option and are very specific. Following this, an RPR titer can help guide treatment. Darkfield microscopy, which can reveal spirochetes directly, isn’t readily available but could be used to diagnose condyloma lata.

Patients who have been given a diagnosis of syphilis should be offered screening for other STIs, including HIV. Anyone who has had sexual contact with the patient within the previous 90 days should be notified, tested, and treated. Patients with primary or secondary syphilis should be treated with 2.4 million units of intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G in a single dose—regardless of whether they test positive for HIV. To exclude tertiary syphilis, a careful neurologic exam should take place at the time of diagnosis and again 6 and 12 months after treatment (sooner if follow-up may be uncertain). Consider treatment failure if RPR titers haven’t fallen fourfold in 12 months. In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a notice that COVID-19-vaccinated patients may have false-positive RPR titers performed from Bio-Rad Laboratories (BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR kit).1

In this case, the patient tested positive for treponemal antibodies and had an RPR titer of 1:128. She was treated with IM benzathine penicillin with lasting clearance.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infection Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Reviewed December 22, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infection Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Reviewed December 22, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm

Discoid lupus

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

DLE is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

DLE lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. DLE lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

2. Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

3. Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

4. McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

5. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

6. Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

7. Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patient-physician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

8. Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

DLE is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

DLE lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. DLE lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

DLE is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

DLE lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. DLE lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

2. Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

3. Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

4. McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

5. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

6. Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

7. Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patient-physician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

8. Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

2. Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

3. Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

4. McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

5. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

6. Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

7. Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patient-physician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

8. Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

Complex link between gut microbiome and immunotherapy response in advanced melanoma

A large-scale than previously thought.

Overall, researchers identified a panel of species, including Roseburia spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila, associated with responses to ICI therapy. However, no single species was a “fully consistent biomarker” across the studies, the authors explain.

This “machine learning analysis confirmed the link between the microbiome and overall response rates (ORRs) and progression-free survival (PFS) with ICIs but also revealed limited reproducibility of microbiome-based signatures across cohorts,” Karla A. Lee, PhD, a clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and colleagues report. The results suggest that “the microbiome is predictive of response in some, but not all, cohorts.”

The findings were published online Feb. 28 in Nature Medicine.

Despite recent advances in targeted therapies for melanoma, less than half of the those who receive a single-agent ICI respond, and those who receive combination ICI therapy often suffer from severe drug toxicity problems. That is why finding patients more likely to respond to a single-agent ICI has become a priority.

Previous studies have identified the gut microbiome as “a potential biomarker of response, as well as a therapeutic target” in melanoma and other malignancies, but “little consensus exists on which microbiome characteristics are associated with treatment responses in the human setting,” the authors explain.

To further clarify the microbiome–immunotherapy relationship, the researchers performed metagenomic sequencing of stool samples collected from 165 ICI-naive patients with unresectable stage III or IV cutaneous melanoma from 5 observational cohorts in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and Spain. These data were integrated with 147 samples from publicly available datasets.

First, the authors highlighted the variability in findings across these observational studies. For instance, they analyzed stool samples from one UK-based observational study of patients with melanoma (PRIMM-UK) and found a small but statistically significant difference in the microbiome composition of immunotherapy responders versus nonresponders (P = .05) but did not find such an association in a parallel study in the Netherlands (PRIMM-NL, P = .61).

The investigators also explored biomarkers of response across different cohorts and found several standouts. In trials using ORR as an endpoint, two uncultivated Roseburia species (CAG:182 and CAG:471) were associated with responses to ICIs. For patients with available PFS data, Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens and Lactobacillus vaginalis were “enriched in responders” across 7 datasets and significant in 3 of the 8 meta-analysis approaches. A muciniphila and Dorea formicigenerans were also associated with ORR and PFS at 12 months in several meta-analyses.

However, “no single bacterium was a fully consistent biomarker of response across all datasets,” the authors wrote.

Still, the findings could have important implications for the more than 50% of patients with advanced melanoma who don’t respond to single-agent ICI therapy.

“Our study shows that studying the microbiome is important to improve and personalize immunotherapy treatments for melanoma,” study coauthor Nicola Segata, PhD, principal investigator in the Laboratory of Computational Metagenomics, University of Trento, Italy, said in a press release. “However, it also suggests that because of the person-to-person variability of the gut microbiome, even larger studies must be carried out to understand the specific gut microbial features that are more likely to lead to a positive response to immunotherapy.”

Coauthor Tim Spector, PhD, head of the Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London, added that “the ultimate goal is to identify which specific features of the microbiome are directly influencing the clinical benefits of immunotherapy to exploit these features in new personalized approaches to support cancer immunotherapy.”

In the meantime, he said, “this study highlights the potential impact of good diet and gut health on chances of survival in patients undergoing immunotherapy.”

This study was coordinated by King’s College London, CIBIO Department of the University of Trento and European Institute of Oncology in Italy, and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and was funded by the Seerave Foundation. Dr. Lee, Dr. Segata, and Dr. Spector have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A large-scale than previously thought.

Overall, researchers identified a panel of species, including Roseburia spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila, associated with responses to ICI therapy. However, no single species was a “fully consistent biomarker” across the studies, the authors explain.

This “machine learning analysis confirmed the link between the microbiome and overall response rates (ORRs) and progression-free survival (PFS) with ICIs but also revealed limited reproducibility of microbiome-based signatures across cohorts,” Karla A. Lee, PhD, a clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and colleagues report. The results suggest that “the microbiome is predictive of response in some, but not all, cohorts.”

The findings were published online Feb. 28 in Nature Medicine.

Despite recent advances in targeted therapies for melanoma, less than half of the those who receive a single-agent ICI respond, and those who receive combination ICI therapy often suffer from severe drug toxicity problems. That is why finding patients more likely to respond to a single-agent ICI has become a priority.

Previous studies have identified the gut microbiome as “a potential biomarker of response, as well as a therapeutic target” in melanoma and other malignancies, but “little consensus exists on which microbiome characteristics are associated with treatment responses in the human setting,” the authors explain.

To further clarify the microbiome–immunotherapy relationship, the researchers performed metagenomic sequencing of stool samples collected from 165 ICI-naive patients with unresectable stage III or IV cutaneous melanoma from 5 observational cohorts in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and Spain. These data were integrated with 147 samples from publicly available datasets.

First, the authors highlighted the variability in findings across these observational studies. For instance, they analyzed stool samples from one UK-based observational study of patients with melanoma (PRIMM-UK) and found a small but statistically significant difference in the microbiome composition of immunotherapy responders versus nonresponders (P = .05) but did not find such an association in a parallel study in the Netherlands (PRIMM-NL, P = .61).

The investigators also explored biomarkers of response across different cohorts and found several standouts. In trials using ORR as an endpoint, two uncultivated Roseburia species (CAG:182 and CAG:471) were associated with responses to ICIs. For patients with available PFS data, Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens and Lactobacillus vaginalis were “enriched in responders” across 7 datasets and significant in 3 of the 8 meta-analysis approaches. A muciniphila and Dorea formicigenerans were also associated with ORR and PFS at 12 months in several meta-analyses.

However, “no single bacterium was a fully consistent biomarker of response across all datasets,” the authors wrote.

Still, the findings could have important implications for the more than 50% of patients with advanced melanoma who don’t respond to single-agent ICI therapy.

“Our study shows that studying the microbiome is important to improve and personalize immunotherapy treatments for melanoma,” study coauthor Nicola Segata, PhD, principal investigator in the Laboratory of Computational Metagenomics, University of Trento, Italy, said in a press release. “However, it also suggests that because of the person-to-person variability of the gut microbiome, even larger studies must be carried out to understand the specific gut microbial features that are more likely to lead to a positive response to immunotherapy.”

Coauthor Tim Spector, PhD, head of the Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London, added that “the ultimate goal is to identify which specific features of the microbiome are directly influencing the clinical benefits of immunotherapy to exploit these features in new personalized approaches to support cancer immunotherapy.”

In the meantime, he said, “this study highlights the potential impact of good diet and gut health on chances of survival in patients undergoing immunotherapy.”

This study was coordinated by King’s College London, CIBIO Department of the University of Trento and European Institute of Oncology in Italy, and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and was funded by the Seerave Foundation. Dr. Lee, Dr. Segata, and Dr. Spector have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A large-scale than previously thought.

Overall, researchers identified a panel of species, including Roseburia spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila, associated with responses to ICI therapy. However, no single species was a “fully consistent biomarker” across the studies, the authors explain.

This “machine learning analysis confirmed the link between the microbiome and overall response rates (ORRs) and progression-free survival (PFS) with ICIs but also revealed limited reproducibility of microbiome-based signatures across cohorts,” Karla A. Lee, PhD, a clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and colleagues report. The results suggest that “the microbiome is predictive of response in some, but not all, cohorts.”

The findings were published online Feb. 28 in Nature Medicine.

Despite recent advances in targeted therapies for melanoma, less than half of the those who receive a single-agent ICI respond, and those who receive combination ICI therapy often suffer from severe drug toxicity problems. That is why finding patients more likely to respond to a single-agent ICI has become a priority.

Previous studies have identified the gut microbiome as “a potential biomarker of response, as well as a therapeutic target” in melanoma and other malignancies, but “little consensus exists on which microbiome characteristics are associated with treatment responses in the human setting,” the authors explain.

To further clarify the microbiome–immunotherapy relationship, the researchers performed metagenomic sequencing of stool samples collected from 165 ICI-naive patients with unresectable stage III or IV cutaneous melanoma from 5 observational cohorts in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and Spain. These data were integrated with 147 samples from publicly available datasets.

First, the authors highlighted the variability in findings across these observational studies. For instance, they analyzed stool samples from one UK-based observational study of patients with melanoma (PRIMM-UK) and found a small but statistically significant difference in the microbiome composition of immunotherapy responders versus nonresponders (P = .05) but did not find such an association in a parallel study in the Netherlands (PRIMM-NL, P = .61).

The investigators also explored biomarkers of response across different cohorts and found several standouts. In trials using ORR as an endpoint, two uncultivated Roseburia species (CAG:182 and CAG:471) were associated with responses to ICIs. For patients with available PFS data, Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens and Lactobacillus vaginalis were “enriched in responders” across 7 datasets and significant in 3 of the 8 meta-analysis approaches. A muciniphila and Dorea formicigenerans were also associated with ORR and PFS at 12 months in several meta-analyses.

However, “no single bacterium was a fully consistent biomarker of response across all datasets,” the authors wrote.

Still, the findings could have important implications for the more than 50% of patients with advanced melanoma who don’t respond to single-agent ICI therapy.

“Our study shows that studying the microbiome is important to improve and personalize immunotherapy treatments for melanoma,” study coauthor Nicola Segata, PhD, principal investigator in the Laboratory of Computational Metagenomics, University of Trento, Italy, said in a press release. “However, it also suggests that because of the person-to-person variability of the gut microbiome, even larger studies must be carried out to understand the specific gut microbial features that are more likely to lead to a positive response to immunotherapy.”

Coauthor Tim Spector, PhD, head of the Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London, added that “the ultimate goal is to identify which specific features of the microbiome are directly influencing the clinical benefits of immunotherapy to exploit these features in new personalized approaches to support cancer immunotherapy.”

In the meantime, he said, “this study highlights the potential impact of good diet and gut health on chances of survival in patients undergoing immunotherapy.”

This study was coordinated by King’s College London, CIBIO Department of the University of Trento and European Institute of Oncology in Italy, and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and was funded by the Seerave Foundation. Dr. Lee, Dr. Segata, and Dr. Spector have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Methotrexate plus leflunomide proves effective for PsA

A new study has found that methotrexate plus leflunomide outperforms methotrexate alone as a treatment option for patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

“We believe that prescribing this combination in routine practice is viable when combined with shared decision-making and strict monitoring of side effects,” write Michelle L.M. Mulder, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Sint Maartenskliniek in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and her coauthors. Their findings were published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

The latest treatment guidelines from the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommend conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for patients with active PsA, but Dr. Mulder and her colleagues note a distinct lack of information on their effectiveness, especially this particular combination.

To assess the efficacy and safety of methotrexate plus leflunomide, they launched a single-center, double-blind, randomized trial that included 78 Dutch patients with PsA. The majority of the participants in this trial – dubbed COMPLETE-PsA – were men (64%), and the median age of the patients was 55 years. All had active disease at baseline; the median swollen joint count (SJC) and tender joint count were 4.0 in both groups.

Participants were assigned to receive either methotrexate plus leflunomide (n = 39) or methotrexate plus placebo (n = 39). After 16 weeks, mean Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Score (PASDAS) had improved for patients in the combination therapy group in comparison with the monotherapy group (3.1; standard deviation, 1.4 vs. 3.7; SD, 1.3; treatment difference, –0.6; 90% confidence interval, –1.0 to –0.1; P = .025). The combination therapy group also achieved PASDAS low disease activity at a higher rate (59%) than did the monotherapy group (34%; P = .019).

Other notable differences after 16 weeks included improvements in SJC for 66 joints (–3.0 in the combination therapy group vs. –2.0 in the monotherapy group) and significantly better skin and nail measures – such as active psoriasis and change in body surface area – in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group.

When asked who should be prescribed the combination therapy and who should be prescribed methotrexate going forward, Dr. Mulder told this news organization, “At the moment, we have insufficient knowledge on who will benefit most or who will develop clinically relevant side effects. It seems warranted to discuss with every patient which approach they would prefer. This could be a step-down or -up approach.

“We hope to be able to better predict treatment response and side effects in the future via post hoc analysis of our study and via extensive flow-cytometric phenotyping of immune blood cells taken at baseline,” she added.

Three patients in the combination therapy group experienced serious adverse events, two of which were deemed unrelated to leflunomide. The most frequently occurring adverse events were nausea or vomiting, tiredness, and elevated alanine aminotransferase. Mild adverse events were more common in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group. No participants died, and all patients with adverse events recovered completely.

“It appears good practice to do blood draws for laboratory tests on liver enzymes at least monthly for the first 4 months and every 4 months after that once stable dosing is achieved, as well as have a telephone consultation after 6-8 weeks to talk about possible side effects a patient might experience and change or add therapy if necessary,” Dr. Mulder added.

Study turns perception of combination therapy into reality

It had already been perceived by rheumatologists that methotrexate plus leflunomide was an effective combo for PsA, and this study reinforces those beliefs, Clementina López-Medina, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the University of Cordoba (Spain), write in an accompanying editorial.

They highlight this study’s notable strengths, one of which was defining “active disease” as two or more swollen joints, which opened the study up to a larger patient population. The editorialists also underline the confirmation that leflunomide plus methotrexate reduces both joint symptoms and skin involvement in this subset of patients, which had also been found in a previous study.

“Leflunomide is usually considered as a second-line option after methotrexate is unsuccessful,” they note, “despite the fact that methotrexate did not show superiority over placebo in previous trials.”

The editorialists were not surprised that the combination therapy was more toxic than the monotherapy. Rheumatologists could use these data to individualize treatment accordingly, they write, while keeping an eye on “gastrointestinal disturbances.”

Overall, Dr. López-Medina and colleagues say that the study results should “be considered not only in daily clinical practice but also in the development of future recommendations.”

Leflunomide: Forgotten no longer, at least for PsA

“I think we probably underutilize leflunomide,” Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Innovative Therapy at the University of California, San Diego, told this news organization. “Sometimes medicines get ‘old,’ for lack of a better term, and fall a little bit of out of favor, sometimes unnecessarily. Leflunomide falls into that category. Because it’s older, it doesn’t get as much buzz as what’s new and shiny.

“I was not surprised by the results on the joints,” he said, “because we know from previous studies that leflunomide works in that regard. What did surprise me is that the skin got better, especially with the combination.”

Regarding the side effects for the combination therapy, he commended the authors for limiting potential uncertainty by using such a high dose of methotrexate.

“By going with a dose of 25 mg [per week], no one can say, ‘They pulled their punches and methotrexate monotherapy would’ve been just as good if it was given at a higher dose,’ “ he said. “And they also used leflunomide at a high dose. It makes you wonder: Could you use lower doses, and do lower doses mean fewer lab test abnormalities? This positive study does lend itself to some other permutations in terms of study design.

“Even though this was a small study,” he added, “it brings us right back to: We should really consider leflunomide in the treatment of PsA.”

The authors acknowledge their study’s limitations, including the fact that it was conducted in a single country and the absence of a nontreatment placebo group. They also note the higher percentage of women in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group, “which might have lowered the treatment response and increased the adverse event rate, resulting in bias.”

The study was funded by a Regional Junior Researcher Grant from Sint Maartenskliniek. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving payment, research grants, and consulting and speaker fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that methotrexate plus leflunomide outperforms methotrexate alone as a treatment option for patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

“We believe that prescribing this combination in routine practice is viable when combined with shared decision-making and strict monitoring of side effects,” write Michelle L.M. Mulder, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Sint Maartenskliniek in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and her coauthors. Their findings were published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

The latest treatment guidelines from the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommend conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for patients with active PsA, but Dr. Mulder and her colleagues note a distinct lack of information on their effectiveness, especially this particular combination.

To assess the efficacy and safety of methotrexate plus leflunomide, they launched a single-center, double-blind, randomized trial that included 78 Dutch patients with PsA. The majority of the participants in this trial – dubbed COMPLETE-PsA – were men (64%), and the median age of the patients was 55 years. All had active disease at baseline; the median swollen joint count (SJC) and tender joint count were 4.0 in both groups.

Participants were assigned to receive either methotrexate plus leflunomide (n = 39) or methotrexate plus placebo (n = 39). After 16 weeks, mean Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Score (PASDAS) had improved for patients in the combination therapy group in comparison with the monotherapy group (3.1; standard deviation, 1.4 vs. 3.7; SD, 1.3; treatment difference, –0.6; 90% confidence interval, –1.0 to –0.1; P = .025). The combination therapy group also achieved PASDAS low disease activity at a higher rate (59%) than did the monotherapy group (34%; P = .019).

Other notable differences after 16 weeks included improvements in SJC for 66 joints (–3.0 in the combination therapy group vs. –2.0 in the monotherapy group) and significantly better skin and nail measures – such as active psoriasis and change in body surface area – in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group.

When asked who should be prescribed the combination therapy and who should be prescribed methotrexate going forward, Dr. Mulder told this news organization, “At the moment, we have insufficient knowledge on who will benefit most or who will develop clinically relevant side effects. It seems warranted to discuss with every patient which approach they would prefer. This could be a step-down or -up approach.

“We hope to be able to better predict treatment response and side effects in the future via post hoc analysis of our study and via extensive flow-cytometric phenotyping of immune blood cells taken at baseline,” she added.

Three patients in the combination therapy group experienced serious adverse events, two of which were deemed unrelated to leflunomide. The most frequently occurring adverse events were nausea or vomiting, tiredness, and elevated alanine aminotransferase. Mild adverse events were more common in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group. No participants died, and all patients with adverse events recovered completely.

“It appears good practice to do blood draws for laboratory tests on liver enzymes at least monthly for the first 4 months and every 4 months after that once stable dosing is achieved, as well as have a telephone consultation after 6-8 weeks to talk about possible side effects a patient might experience and change or add therapy if necessary,” Dr. Mulder added.

Study turns perception of combination therapy into reality

It had already been perceived by rheumatologists that methotrexate plus leflunomide was an effective combo for PsA, and this study reinforces those beliefs, Clementina López-Medina, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the University of Cordoba (Spain), write in an accompanying editorial.

They highlight this study’s notable strengths, one of which was defining “active disease” as two or more swollen joints, which opened the study up to a larger patient population. The editorialists also underline the confirmation that leflunomide plus methotrexate reduces both joint symptoms and skin involvement in this subset of patients, which had also been found in a previous study.

“Leflunomide is usually considered as a second-line option after methotrexate is unsuccessful,” they note, “despite the fact that methotrexate did not show superiority over placebo in previous trials.”

The editorialists were not surprised that the combination therapy was more toxic than the monotherapy. Rheumatologists could use these data to individualize treatment accordingly, they write, while keeping an eye on “gastrointestinal disturbances.”

Overall, Dr. López-Medina and colleagues say that the study results should “be considered not only in daily clinical practice but also in the development of future recommendations.”

Leflunomide: Forgotten no longer, at least for PsA

“I think we probably underutilize leflunomide,” Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Innovative Therapy at the University of California, San Diego, told this news organization. “Sometimes medicines get ‘old,’ for lack of a better term, and fall a little bit of out of favor, sometimes unnecessarily. Leflunomide falls into that category. Because it’s older, it doesn’t get as much buzz as what’s new and shiny.

“I was not surprised by the results on the joints,” he said, “because we know from previous studies that leflunomide works in that regard. What did surprise me is that the skin got better, especially with the combination.”

Regarding the side effects for the combination therapy, he commended the authors for limiting potential uncertainty by using such a high dose of methotrexate.

“By going with a dose of 25 mg [per week], no one can say, ‘They pulled their punches and methotrexate monotherapy would’ve been just as good if it was given at a higher dose,’ “ he said. “And they also used leflunomide at a high dose. It makes you wonder: Could you use lower doses, and do lower doses mean fewer lab test abnormalities? This positive study does lend itself to some other permutations in terms of study design.

“Even though this was a small study,” he added, “it brings us right back to: We should really consider leflunomide in the treatment of PsA.”

The authors acknowledge their study’s limitations, including the fact that it was conducted in a single country and the absence of a nontreatment placebo group. They also note the higher percentage of women in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group, “which might have lowered the treatment response and increased the adverse event rate, resulting in bias.”

The study was funded by a Regional Junior Researcher Grant from Sint Maartenskliniek. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving payment, research grants, and consulting and speaker fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that methotrexate plus leflunomide outperforms methotrexate alone as a treatment option for patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

“We believe that prescribing this combination in routine practice is viable when combined with shared decision-making and strict monitoring of side effects,” write Michelle L.M. Mulder, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Sint Maartenskliniek in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and her coauthors. Their findings were published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

The latest treatment guidelines from the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommend conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for patients with active PsA, but Dr. Mulder and her colleagues note a distinct lack of information on their effectiveness, especially this particular combination.

To assess the efficacy and safety of methotrexate plus leflunomide, they launched a single-center, double-blind, randomized trial that included 78 Dutch patients with PsA. The majority of the participants in this trial – dubbed COMPLETE-PsA – were men (64%), and the median age of the patients was 55 years. All had active disease at baseline; the median swollen joint count (SJC) and tender joint count were 4.0 in both groups.

Participants were assigned to receive either methotrexate plus leflunomide (n = 39) or methotrexate plus placebo (n = 39). After 16 weeks, mean Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Score (PASDAS) had improved for patients in the combination therapy group in comparison with the monotherapy group (3.1; standard deviation, 1.4 vs. 3.7; SD, 1.3; treatment difference, –0.6; 90% confidence interval, –1.0 to –0.1; P = .025). The combination therapy group also achieved PASDAS low disease activity at a higher rate (59%) than did the monotherapy group (34%; P = .019).

Other notable differences after 16 weeks included improvements in SJC for 66 joints (–3.0 in the combination therapy group vs. –2.0 in the monotherapy group) and significantly better skin and nail measures – such as active psoriasis and change in body surface area – in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group.

When asked who should be prescribed the combination therapy and who should be prescribed methotrexate going forward, Dr. Mulder told this news organization, “At the moment, we have insufficient knowledge on who will benefit most or who will develop clinically relevant side effects. It seems warranted to discuss with every patient which approach they would prefer. This could be a step-down or -up approach.

“We hope to be able to better predict treatment response and side effects in the future via post hoc analysis of our study and via extensive flow-cytometric phenotyping of immune blood cells taken at baseline,” she added.

Three patients in the combination therapy group experienced serious adverse events, two of which were deemed unrelated to leflunomide. The most frequently occurring adverse events were nausea or vomiting, tiredness, and elevated alanine aminotransferase. Mild adverse events were more common in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group. No participants died, and all patients with adverse events recovered completely.

“It appears good practice to do blood draws for laboratory tests on liver enzymes at least monthly for the first 4 months and every 4 months after that once stable dosing is achieved, as well as have a telephone consultation after 6-8 weeks to talk about possible side effects a patient might experience and change or add therapy if necessary,” Dr. Mulder added.

Study turns perception of combination therapy into reality

It had already been perceived by rheumatologists that methotrexate plus leflunomide was an effective combo for PsA, and this study reinforces those beliefs, Clementina López-Medina, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the University of Cordoba (Spain), write in an accompanying editorial.

They highlight this study’s notable strengths, one of which was defining “active disease” as two or more swollen joints, which opened the study up to a larger patient population. The editorialists also underline the confirmation that leflunomide plus methotrexate reduces both joint symptoms and skin involvement in this subset of patients, which had also been found in a previous study.

“Leflunomide is usually considered as a second-line option after methotrexate is unsuccessful,” they note, “despite the fact that methotrexate did not show superiority over placebo in previous trials.”

The editorialists were not surprised that the combination therapy was more toxic than the monotherapy. Rheumatologists could use these data to individualize treatment accordingly, they write, while keeping an eye on “gastrointestinal disturbances.”

Overall, Dr. López-Medina and colleagues say that the study results should “be considered not only in daily clinical practice but also in the development of future recommendations.”

Leflunomide: Forgotten no longer, at least for PsA

“I think we probably underutilize leflunomide,” Arthur Kavanaugh, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Innovative Therapy at the University of California, San Diego, told this news organization. “Sometimes medicines get ‘old,’ for lack of a better term, and fall a little bit of out of favor, sometimes unnecessarily. Leflunomide falls into that category. Because it’s older, it doesn’t get as much buzz as what’s new and shiny.

“I was not surprised by the results on the joints,” he said, “because we know from previous studies that leflunomide works in that regard. What did surprise me is that the skin got better, especially with the combination.”

Regarding the side effects for the combination therapy, he commended the authors for limiting potential uncertainty by using such a high dose of methotrexate.

“By going with a dose of 25 mg [per week], no one can say, ‘They pulled their punches and methotrexate monotherapy would’ve been just as good if it was given at a higher dose,’ “ he said. “And they also used leflunomide at a high dose. It makes you wonder: Could you use lower doses, and do lower doses mean fewer lab test abnormalities? This positive study does lend itself to some other permutations in terms of study design.

“Even though this was a small study,” he added, “it brings us right back to: We should really consider leflunomide in the treatment of PsA.”

The authors acknowledge their study’s limitations, including the fact that it was conducted in a single country and the absence of a nontreatment placebo group. They also note the higher percentage of women in the methotrexate plus leflunomide group, “which might have lowered the treatment response and increased the adverse event rate, resulting in bias.”

The study was funded by a Regional Junior Researcher Grant from Sint Maartenskliniek. The authors reported numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving payment, research grants, and consulting and speaker fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

Extensive scarring alopecia and widespread rash

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

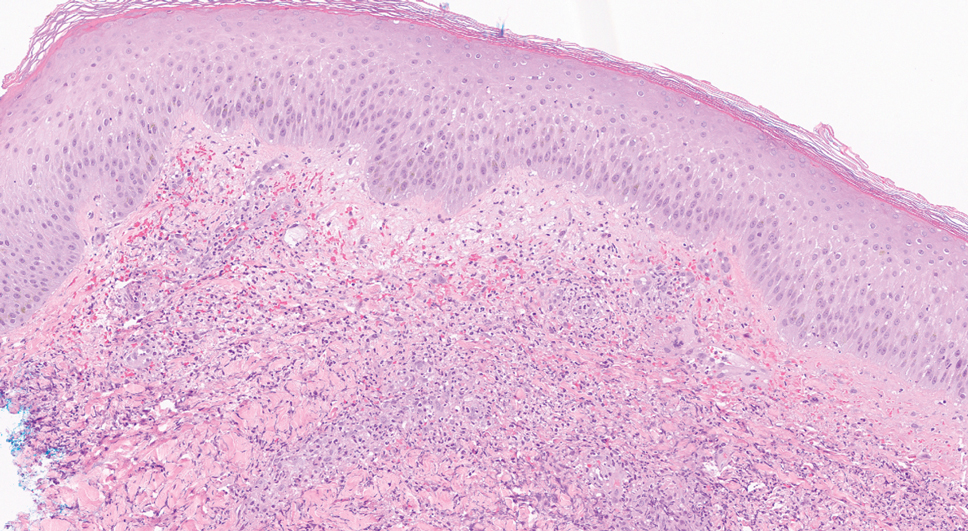

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

1. Petty AJ, Floyd L, Henderson C, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: progress and challenges. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00906-8

2. Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.021

3. Durosaro O, Davis MDP, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249-253. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.21

4. Merola JF. Overview of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. UpToDate. Updated September 19, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus

5. Biazar C, Sigges J, Patsinakidis N, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: first multicenter database analysis of 1002 patients from the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (EUSCLE). Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:444-454. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.08.019

6. O’Brien JC, Chong BF. not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

7. Kuhn A, Ruland V, Bonsmann G. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: update of therapeutic options part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e179-e193. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.018

8. Kindle SA, Wetter DA, Davis MDP, et al. Lenalidomide treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e431-e439. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13226

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

1. Petty AJ, Floyd L, Henderson C, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: progress and challenges. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00906-8

2. Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.021

3. Durosaro O, Davis MDP, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249-253. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.21