User login

Cohort study finds a twofold greater psoriasis risk linked to a PCOS diagnosis

PCOS is characterized by androgen elevation that can lead to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, which have also been associated with an increased risk of psoriasis. Previous retrospective analyses have suggested an increased risk of psoriasis associated with PCOS, and psoriasis patients with PCOS have been reported to have more severe skin lesions, compared with those who do not have PCOS.

“The incidence of psoriasis is indeed higher in the PCOS group than in the control group, and the comorbidities related to metabolic syndrome did not modify the adjusted hazard ratio,” said Ming-Li Chen, during her presentation of the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Dr. Chen is at Chung Shan Medical University in Taiwan.

The researchers analyzed 1 million randomly selected records from Taiwan’s Longitudinal Health Insurance database, a subset of the country’s National Health Insurance Program. Between 2000 and 2012, they identified a case group with at least three outpatient diagnoses or one inpatient diagnosis of PCOS; they then compared each with four patients who did not have PCOS who were matched by age and index year. The mean age in both groups was about 27 years.

The mean follow-up times were 6.99 years for 4,707 cases and 6.94 years for 18,828 controls. Comorbidities were slightly higher in the PCOS group, including asthma (6.7% vs. 4.9%; P less than .001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (14% vs. 11%; P less than .001), chronic liver disease (8.0% vs. 5.0%; P less than .001), diabetes mellitus (3.0% vs. 1.4%; P less than .001), hypertension (2.4% vs. 1.5%; P less than .001), hyperlipidemia (5.4% vs. 2.5%; P less than .001), depression (5.4% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001), and sleep apnea (0.23% vs. 0.10%; P = .040).

There was a higher cumulative incidence of psoriasis in the PCOS group (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.25-3.44). Other factors associated with increased risk of psoriasis were advanced age (greater than 50 years old; aHR, 14.13; 95% CI, 1.8-110.7) and having a cancer diagnosis (aHR, 11.72; 95% CI, 2.87-47.9).

When PCOS patients were stratified by age, the researchers noted a higher risk of psoriasis among those 20 years or younger (aHR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.16-13.9) than among those aged 20-50 years (aHR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.07-3.29). Among those older than 50 years, there was no significantly increased risk, although the number of psoriasis diagnoses and population sizes were small in the latter category. Among patients with PCOS, a cancer diagnosis was not associated with a statistically significant increased risk of psoriasis.

The mechanisms underlying the association between PCOS and psoriasis should be studied further, she noted.

Following Dr. Chen’s prerecorded presentation, there was a live discussion session led by Alice Gottlieb, MD, PhD, medical director of Mount Sinai Beth Israel Dermatology, New York, and Ennio Lubrano, MD, associate professor of rheumatology at the University of Molise (Italy). Dr. Gottlieb noted that the study did not appear to account for weight in the association between PCOS and psoriasis, since heavier people are known to be at greater risk of developing psoriasis. Dr. Chen acknowledged that the study had no records of BMI or weight.

Dr. Gottlieb also wondered if treatment of PCOS led to any improvements in psoriasis in patients with the two diagnoses. “If we treat PCOS, does the psoriasis get better?” Again, the study did not address the question. “We didn’t follow up on therapies,” Dr. Chen said.

Dr. Chen reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Gottlieb is a consultant, advisory board member and/or speaker for AbbVie, Allergan, Avotres Therapeutics, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Reddy Labs, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, UCB Pharma and Xbiotech. She has received research or educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis and Xbiotech.

PCOS is characterized by androgen elevation that can lead to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, which have also been associated with an increased risk of psoriasis. Previous retrospective analyses have suggested an increased risk of psoriasis associated with PCOS, and psoriasis patients with PCOS have been reported to have more severe skin lesions, compared with those who do not have PCOS.

“The incidence of psoriasis is indeed higher in the PCOS group than in the control group, and the comorbidities related to metabolic syndrome did not modify the adjusted hazard ratio,” said Ming-Li Chen, during her presentation of the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Dr. Chen is at Chung Shan Medical University in Taiwan.

The researchers analyzed 1 million randomly selected records from Taiwan’s Longitudinal Health Insurance database, a subset of the country’s National Health Insurance Program. Between 2000 and 2012, they identified a case group with at least three outpatient diagnoses or one inpatient diagnosis of PCOS; they then compared each with four patients who did not have PCOS who were matched by age and index year. The mean age in both groups was about 27 years.

The mean follow-up times were 6.99 years for 4,707 cases and 6.94 years for 18,828 controls. Comorbidities were slightly higher in the PCOS group, including asthma (6.7% vs. 4.9%; P less than .001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (14% vs. 11%; P less than .001), chronic liver disease (8.0% vs. 5.0%; P less than .001), diabetes mellitus (3.0% vs. 1.4%; P less than .001), hypertension (2.4% vs. 1.5%; P less than .001), hyperlipidemia (5.4% vs. 2.5%; P less than .001), depression (5.4% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001), and sleep apnea (0.23% vs. 0.10%; P = .040).

There was a higher cumulative incidence of psoriasis in the PCOS group (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.25-3.44). Other factors associated with increased risk of psoriasis were advanced age (greater than 50 years old; aHR, 14.13; 95% CI, 1.8-110.7) and having a cancer diagnosis (aHR, 11.72; 95% CI, 2.87-47.9).

When PCOS patients were stratified by age, the researchers noted a higher risk of psoriasis among those 20 years or younger (aHR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.16-13.9) than among those aged 20-50 years (aHR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.07-3.29). Among those older than 50 years, there was no significantly increased risk, although the number of psoriasis diagnoses and population sizes were small in the latter category. Among patients with PCOS, a cancer diagnosis was not associated with a statistically significant increased risk of psoriasis.

The mechanisms underlying the association between PCOS and psoriasis should be studied further, she noted.

Following Dr. Chen’s prerecorded presentation, there was a live discussion session led by Alice Gottlieb, MD, PhD, medical director of Mount Sinai Beth Israel Dermatology, New York, and Ennio Lubrano, MD, associate professor of rheumatology at the University of Molise (Italy). Dr. Gottlieb noted that the study did not appear to account for weight in the association between PCOS and psoriasis, since heavier people are known to be at greater risk of developing psoriasis. Dr. Chen acknowledged that the study had no records of BMI or weight.

Dr. Gottlieb also wondered if treatment of PCOS led to any improvements in psoriasis in patients with the two diagnoses. “If we treat PCOS, does the psoriasis get better?” Again, the study did not address the question. “We didn’t follow up on therapies,” Dr. Chen said.

Dr. Chen reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Gottlieb is a consultant, advisory board member and/or speaker for AbbVie, Allergan, Avotres Therapeutics, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Reddy Labs, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, UCB Pharma and Xbiotech. She has received research or educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis and Xbiotech.

PCOS is characterized by androgen elevation that can lead to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, which have also been associated with an increased risk of psoriasis. Previous retrospective analyses have suggested an increased risk of psoriasis associated with PCOS, and psoriasis patients with PCOS have been reported to have more severe skin lesions, compared with those who do not have PCOS.

“The incidence of psoriasis is indeed higher in the PCOS group than in the control group, and the comorbidities related to metabolic syndrome did not modify the adjusted hazard ratio,” said Ming-Li Chen, during her presentation of the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Dr. Chen is at Chung Shan Medical University in Taiwan.

The researchers analyzed 1 million randomly selected records from Taiwan’s Longitudinal Health Insurance database, a subset of the country’s National Health Insurance Program. Between 2000 and 2012, they identified a case group with at least three outpatient diagnoses or one inpatient diagnosis of PCOS; they then compared each with four patients who did not have PCOS who were matched by age and index year. The mean age in both groups was about 27 years.

The mean follow-up times were 6.99 years for 4,707 cases and 6.94 years for 18,828 controls. Comorbidities were slightly higher in the PCOS group, including asthma (6.7% vs. 4.9%; P less than .001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (14% vs. 11%; P less than .001), chronic liver disease (8.0% vs. 5.0%; P less than .001), diabetes mellitus (3.0% vs. 1.4%; P less than .001), hypertension (2.4% vs. 1.5%; P less than .001), hyperlipidemia (5.4% vs. 2.5%; P less than .001), depression (5.4% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001), and sleep apnea (0.23% vs. 0.10%; P = .040).

There was a higher cumulative incidence of psoriasis in the PCOS group (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.25-3.44). Other factors associated with increased risk of psoriasis were advanced age (greater than 50 years old; aHR, 14.13; 95% CI, 1.8-110.7) and having a cancer diagnosis (aHR, 11.72; 95% CI, 2.87-47.9).

When PCOS patients were stratified by age, the researchers noted a higher risk of psoriasis among those 20 years or younger (aHR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.16-13.9) than among those aged 20-50 years (aHR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.07-3.29). Among those older than 50 years, there was no significantly increased risk, although the number of psoriasis diagnoses and population sizes were small in the latter category. Among patients with PCOS, a cancer diagnosis was not associated with a statistically significant increased risk of psoriasis.

The mechanisms underlying the association between PCOS and psoriasis should be studied further, she noted.

Following Dr. Chen’s prerecorded presentation, there was a live discussion session led by Alice Gottlieb, MD, PhD, medical director of Mount Sinai Beth Israel Dermatology, New York, and Ennio Lubrano, MD, associate professor of rheumatology at the University of Molise (Italy). Dr. Gottlieb noted that the study did not appear to account for weight in the association between PCOS and psoriasis, since heavier people are known to be at greater risk of developing psoriasis. Dr. Chen acknowledged that the study had no records of BMI or weight.

Dr. Gottlieb also wondered if treatment of PCOS led to any improvements in psoriasis in patients with the two diagnoses. “If we treat PCOS, does the psoriasis get better?” Again, the study did not address the question. “We didn’t follow up on therapies,” Dr. Chen said.

Dr. Chen reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Gottlieb is a consultant, advisory board member and/or speaker for AbbVie, Allergan, Avotres Therapeutics, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Reddy Labs, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, UCB Pharma and Xbiotech. She has received research or educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis and Xbiotech.

FROM GRAPPA 2020 VIRTUAL ANNUAL MEETING

New topicals for excessive sweating are in sight

Safe and effective of novel agents presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Both investigational topical anticholinergic agents – 5% sofpironium bromide (SPB) gel and 1% glycopyrronium bromide (GPB) cream – met all of the efficacy and safety endpoints required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Primary axillary hyperhidrosis, or symmetrical bilateral excessive armpit sweating, has a prevalence worldwide of 1%-16%, with 5%-6% the most frequently cited numbers. The condition has a strong adverse impact on quality of life. Primary axillary hyperhidrosis is not caused by a disorder of the sweat glands; rather, it’s actually a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system leading to disproportionate sweating, explained Christoph Abels, MD, PhD, medical director at Dr. August Wolff in Bielefeld, Germany.

“What’s surprising is that more than 50% of patients do not receive appropriate treatment, very likely due to lack of awareness or embarrassment,” he added.

Also, many patients are put off by the systemic side effects of the oral anticholinergic agents, which are the current off-label treatment mainstay for patients with moderate or severe disease, according to Tomoko Fujimoto, MD, PhD, director of Ikebukuro Nishiguchi Fukurou Dermatology, near Tokyo.

Sofpironium bromide gel

Dr. Fujimoto presented the results of a phase 3, double-blind, multicenter, 6-week, vehicle-controlled clinical trial conducted in 281 Japanese patients with moderate to severe primary axillary hyperhidrosis as defined by a baseline score of 3 or 4 on the 4-point Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS). Participants were randomized to self-application of 5% SPB gel or its vehicle once daily before bedtime.

Sofpironium bromide blocks the cholinergic response mediated by the M3 muscarinic receptor subtype expressed on eccrine sweat glands, thereby inhibiting sweating. The drug then undergoes breakdown into an inactive metabolite after reaching the blood.

An important aspect of both SPB gel and GPB cream is that these agents are rolled onto the axillae using a dedicated applicator. Patients never touch the medications with their hands, thus avoiding accidental exposure to the mucous membranes. This largely prevents problems with mydriasis and blurred vision as anticholinergic side effects, which has been an issue with glycopyrronium tosylate topical cloth wipes (Qbrexza), the first FDA-approved treatment for primary axillary hyperhidrosis.

The primary endpoint in the Japanese study was at least a 1-point improvement on the HDSS plus at least a 50% reduction in gravimetric sweat production between baseline and week 6. This composite outcome was achieved in 53.9% of patients in the active treatment arm, compared with 36.4% of controls.

The secondary endpoint consisting of a week-6 HDSS score of 1 or 2 – that is, underarm sweating that’s either never noticeable or is tolerable – occurred in 60.3% of the sofpironium bromide group and 47.9% of controls, a between-group difference that achieved statistical significance by week 2, when the rates were 46.8% and 28.2%.

The reduction in total gravimetric weight of axillary sweat from a mean baseline of 227 mg collected over 5 minutes was also significantly greater in the SPB group: a decrease of 157.6 mg, compared with 127.6 mg in controls; a between-group difference that also was significant by week 2. The mean Dermatology Life Quality Index score dropped by 6.8 points in the active-treatment arm from a baseline of 11.3, a significant improvement over the mean 4.5-point drop in controls.

A new 5-point measure of subjective symptoms of primary axillary hyperhidrosis – the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Measure–Axilla (HDSM-Ax) – improved by 1.41 points in the SPB group, significantly better than the 0.93 points in vehicle-treated controls. About 48% of patients on SBP experienced at least a 1.5-point reduction on the HDSM-Ax, compared with 26% of controls.

Regarding safety, there was a 2% incidence of application-site itch or scale in the SBP group. Anticholinergic side effects consisted of a single case of mydriasis, another of constipation, and two complaints of thirst, all mild, none resulting in treatment discontinuation. There were no reports of headache or blurred vision.

“These results indicate that the safety risks of sofpironium bromide can be considered small and controllable,” Dr. Fujimoto said. “Moreover, sofpironium bromide is a topical agent that patients can use by themselves, so it is highly convenient, unlike, say, botulinum toxin type A injections.”

Glycopyrronium bromide cream

Following on the heels of a recently published dose-ranging study (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Jan;182[1]:229-231), Dr. Abels presented the 4-week outcomes of a phase 3a, double-blind, randomized, five-country trial of once-daily 1% GPB cream or placebo in 171 patients with moderate or severe primary axillary hyperhidrosis. A phase 3b, open-label, 72-week, long-term safety trial is ongoing in 516 patients.

The primary endpoint of the 4-week trial was the reduction in gravimetric sweat production from day 1 to day 29. A reduction of 50% or more was documented in 57.5% of the patients on GBP and 34.5% of controls. A 75% or greater reduction occurred in 32.2% of the active-treatment group and 16.7% of those on placebo. And a decrease of at least 90% was seen in 23% of patients on topical GBP, compared with 9.5% of controls. All these between-group differences were significant.

The FDA now requires a quality of life measurement as a coprimary endpoint in phase 3 hyperhidrosis studies, and the phase 3 GBP trial also served as the successful validation study for a new patient-reported quality of life instrument designed specifically for this purpose. The new tool, known as the Hyperhydrosis Quality of Life questionnaire (HidroQol), proved much more sensitive than the HDSS or DLQI for evaluating clinical improvement in response to treatment (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Jun 8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19300).

Initial results from the long-term phase 3b safety study should be available this fall on the first 100 patients followed on topical GBP for 1 year and for 300 followed for 6 months, Dr. Abels said.

Dr. Fujimoto reported serving as a paid consultant to and speaker for Kaken Pharmaceutical, which is developing SBP gel with Brickell Biotech. Dr. Abels is an employee of the company that is developing GPB cream.

Safe and effective of novel agents presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Both investigational topical anticholinergic agents – 5% sofpironium bromide (SPB) gel and 1% glycopyrronium bromide (GPB) cream – met all of the efficacy and safety endpoints required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Primary axillary hyperhidrosis, or symmetrical bilateral excessive armpit sweating, has a prevalence worldwide of 1%-16%, with 5%-6% the most frequently cited numbers. The condition has a strong adverse impact on quality of life. Primary axillary hyperhidrosis is not caused by a disorder of the sweat glands; rather, it’s actually a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system leading to disproportionate sweating, explained Christoph Abels, MD, PhD, medical director at Dr. August Wolff in Bielefeld, Germany.

“What’s surprising is that more than 50% of patients do not receive appropriate treatment, very likely due to lack of awareness or embarrassment,” he added.

Also, many patients are put off by the systemic side effects of the oral anticholinergic agents, which are the current off-label treatment mainstay for patients with moderate or severe disease, according to Tomoko Fujimoto, MD, PhD, director of Ikebukuro Nishiguchi Fukurou Dermatology, near Tokyo.

Sofpironium bromide gel

Dr. Fujimoto presented the results of a phase 3, double-blind, multicenter, 6-week, vehicle-controlled clinical trial conducted in 281 Japanese patients with moderate to severe primary axillary hyperhidrosis as defined by a baseline score of 3 or 4 on the 4-point Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS). Participants were randomized to self-application of 5% SPB gel or its vehicle once daily before bedtime.

Sofpironium bromide blocks the cholinergic response mediated by the M3 muscarinic receptor subtype expressed on eccrine sweat glands, thereby inhibiting sweating. The drug then undergoes breakdown into an inactive metabolite after reaching the blood.

An important aspect of both SPB gel and GPB cream is that these agents are rolled onto the axillae using a dedicated applicator. Patients never touch the medications with their hands, thus avoiding accidental exposure to the mucous membranes. This largely prevents problems with mydriasis and blurred vision as anticholinergic side effects, which has been an issue with glycopyrronium tosylate topical cloth wipes (Qbrexza), the first FDA-approved treatment for primary axillary hyperhidrosis.

The primary endpoint in the Japanese study was at least a 1-point improvement on the HDSS plus at least a 50% reduction in gravimetric sweat production between baseline and week 6. This composite outcome was achieved in 53.9% of patients in the active treatment arm, compared with 36.4% of controls.

The secondary endpoint consisting of a week-6 HDSS score of 1 or 2 – that is, underarm sweating that’s either never noticeable or is tolerable – occurred in 60.3% of the sofpironium bromide group and 47.9% of controls, a between-group difference that achieved statistical significance by week 2, when the rates were 46.8% and 28.2%.

The reduction in total gravimetric weight of axillary sweat from a mean baseline of 227 mg collected over 5 minutes was also significantly greater in the SPB group: a decrease of 157.6 mg, compared with 127.6 mg in controls; a between-group difference that also was significant by week 2. The mean Dermatology Life Quality Index score dropped by 6.8 points in the active-treatment arm from a baseline of 11.3, a significant improvement over the mean 4.5-point drop in controls.

A new 5-point measure of subjective symptoms of primary axillary hyperhidrosis – the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Measure–Axilla (HDSM-Ax) – improved by 1.41 points in the SPB group, significantly better than the 0.93 points in vehicle-treated controls. About 48% of patients on SBP experienced at least a 1.5-point reduction on the HDSM-Ax, compared with 26% of controls.

Regarding safety, there was a 2% incidence of application-site itch or scale in the SBP group. Anticholinergic side effects consisted of a single case of mydriasis, another of constipation, and two complaints of thirst, all mild, none resulting in treatment discontinuation. There were no reports of headache or blurred vision.

“These results indicate that the safety risks of sofpironium bromide can be considered small and controllable,” Dr. Fujimoto said. “Moreover, sofpironium bromide is a topical agent that patients can use by themselves, so it is highly convenient, unlike, say, botulinum toxin type A injections.”

Glycopyrronium bromide cream

Following on the heels of a recently published dose-ranging study (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Jan;182[1]:229-231), Dr. Abels presented the 4-week outcomes of a phase 3a, double-blind, randomized, five-country trial of once-daily 1% GPB cream or placebo in 171 patients with moderate or severe primary axillary hyperhidrosis. A phase 3b, open-label, 72-week, long-term safety trial is ongoing in 516 patients.

The primary endpoint of the 4-week trial was the reduction in gravimetric sweat production from day 1 to day 29. A reduction of 50% or more was documented in 57.5% of the patients on GBP and 34.5% of controls. A 75% or greater reduction occurred in 32.2% of the active-treatment group and 16.7% of those on placebo. And a decrease of at least 90% was seen in 23% of patients on topical GBP, compared with 9.5% of controls. All these between-group differences were significant.

The FDA now requires a quality of life measurement as a coprimary endpoint in phase 3 hyperhidrosis studies, and the phase 3 GBP trial also served as the successful validation study for a new patient-reported quality of life instrument designed specifically for this purpose. The new tool, known as the Hyperhydrosis Quality of Life questionnaire (HidroQol), proved much more sensitive than the HDSS or DLQI for evaluating clinical improvement in response to treatment (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Jun 8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19300).

Initial results from the long-term phase 3b safety study should be available this fall on the first 100 patients followed on topical GBP for 1 year and for 300 followed for 6 months, Dr. Abels said.

Dr. Fujimoto reported serving as a paid consultant to and speaker for Kaken Pharmaceutical, which is developing SBP gel with Brickell Biotech. Dr. Abels is an employee of the company that is developing GPB cream.

Safe and effective of novel agents presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Both investigational topical anticholinergic agents – 5% sofpironium bromide (SPB) gel and 1% glycopyrronium bromide (GPB) cream – met all of the efficacy and safety endpoints required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Primary axillary hyperhidrosis, or symmetrical bilateral excessive armpit sweating, has a prevalence worldwide of 1%-16%, with 5%-6% the most frequently cited numbers. The condition has a strong adverse impact on quality of life. Primary axillary hyperhidrosis is not caused by a disorder of the sweat glands; rather, it’s actually a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system leading to disproportionate sweating, explained Christoph Abels, MD, PhD, medical director at Dr. August Wolff in Bielefeld, Germany.

“What’s surprising is that more than 50% of patients do not receive appropriate treatment, very likely due to lack of awareness or embarrassment,” he added.

Also, many patients are put off by the systemic side effects of the oral anticholinergic agents, which are the current off-label treatment mainstay for patients with moderate or severe disease, according to Tomoko Fujimoto, MD, PhD, director of Ikebukuro Nishiguchi Fukurou Dermatology, near Tokyo.

Sofpironium bromide gel

Dr. Fujimoto presented the results of a phase 3, double-blind, multicenter, 6-week, vehicle-controlled clinical trial conducted in 281 Japanese patients with moderate to severe primary axillary hyperhidrosis as defined by a baseline score of 3 or 4 on the 4-point Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS). Participants were randomized to self-application of 5% SPB gel or its vehicle once daily before bedtime.

Sofpironium bromide blocks the cholinergic response mediated by the M3 muscarinic receptor subtype expressed on eccrine sweat glands, thereby inhibiting sweating. The drug then undergoes breakdown into an inactive metabolite after reaching the blood.

An important aspect of both SPB gel and GPB cream is that these agents are rolled onto the axillae using a dedicated applicator. Patients never touch the medications with their hands, thus avoiding accidental exposure to the mucous membranes. This largely prevents problems with mydriasis and blurred vision as anticholinergic side effects, which has been an issue with glycopyrronium tosylate topical cloth wipes (Qbrexza), the first FDA-approved treatment for primary axillary hyperhidrosis.

The primary endpoint in the Japanese study was at least a 1-point improvement on the HDSS plus at least a 50% reduction in gravimetric sweat production between baseline and week 6. This composite outcome was achieved in 53.9% of patients in the active treatment arm, compared with 36.4% of controls.

The secondary endpoint consisting of a week-6 HDSS score of 1 or 2 – that is, underarm sweating that’s either never noticeable or is tolerable – occurred in 60.3% of the sofpironium bromide group and 47.9% of controls, a between-group difference that achieved statistical significance by week 2, when the rates were 46.8% and 28.2%.

The reduction in total gravimetric weight of axillary sweat from a mean baseline of 227 mg collected over 5 minutes was also significantly greater in the SPB group: a decrease of 157.6 mg, compared with 127.6 mg in controls; a between-group difference that also was significant by week 2. The mean Dermatology Life Quality Index score dropped by 6.8 points in the active-treatment arm from a baseline of 11.3, a significant improvement over the mean 4.5-point drop in controls.

A new 5-point measure of subjective symptoms of primary axillary hyperhidrosis – the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Measure–Axilla (HDSM-Ax) – improved by 1.41 points in the SPB group, significantly better than the 0.93 points in vehicle-treated controls. About 48% of patients on SBP experienced at least a 1.5-point reduction on the HDSM-Ax, compared with 26% of controls.

Regarding safety, there was a 2% incidence of application-site itch or scale in the SBP group. Anticholinergic side effects consisted of a single case of mydriasis, another of constipation, and two complaints of thirst, all mild, none resulting in treatment discontinuation. There were no reports of headache or blurred vision.

“These results indicate that the safety risks of sofpironium bromide can be considered small and controllable,” Dr. Fujimoto said. “Moreover, sofpironium bromide is a topical agent that patients can use by themselves, so it is highly convenient, unlike, say, botulinum toxin type A injections.”

Glycopyrronium bromide cream

Following on the heels of a recently published dose-ranging study (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Jan;182[1]:229-231), Dr. Abels presented the 4-week outcomes of a phase 3a, double-blind, randomized, five-country trial of once-daily 1% GPB cream or placebo in 171 patients with moderate or severe primary axillary hyperhidrosis. A phase 3b, open-label, 72-week, long-term safety trial is ongoing in 516 patients.

The primary endpoint of the 4-week trial was the reduction in gravimetric sweat production from day 1 to day 29. A reduction of 50% or more was documented in 57.5% of the patients on GBP and 34.5% of controls. A 75% or greater reduction occurred in 32.2% of the active-treatment group and 16.7% of those on placebo. And a decrease of at least 90% was seen in 23% of patients on topical GBP, compared with 9.5% of controls. All these between-group differences were significant.

The FDA now requires a quality of life measurement as a coprimary endpoint in phase 3 hyperhidrosis studies, and the phase 3 GBP trial also served as the successful validation study for a new patient-reported quality of life instrument designed specifically for this purpose. The new tool, known as the Hyperhydrosis Quality of Life questionnaire (HidroQol), proved much more sensitive than the HDSS or DLQI for evaluating clinical improvement in response to treatment (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Jun 8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19300).

Initial results from the long-term phase 3b safety study should be available this fall on the first 100 patients followed on topical GBP for 1 year and for 300 followed for 6 months, Dr. Abels said.

Dr. Fujimoto reported serving as a paid consultant to and speaker for Kaken Pharmaceutical, which is developing SBP gel with Brickell Biotech. Dr. Abels is an employee of the company that is developing GPB cream.

FROM AAD 20

For suspected hair disorders, consider trichoscopy before biopsy

In the clinical experience of Bianca Maria Piraccini, MD,

Dermoscopic imaging, also known as trichoscopy, “avoids invasive procedures and provides immediate results,” Dr. Piraccini, of the University of Bologna’s division of dermatology in the department of experimental, diagnostic, and specialty medicine, said during the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is helpful for diagnosing all sorts of alopecia, starting with those that appear at birth, such as aplasia cutis congenita to those that appear in adolescence, such as androgenetic alopecia.”

Dr. Piraccini noted that lanugo hair is produced at 16-20 weeks’ gestation and is shed in utero and replaced by thicker hair at 32-36 weeks. “The speed of transition from vellus to intermediate and terminal hair varies from child to child,” she said. “The scalp at birth presents with thin, intermediate, or thick hair.”

In a dermoscopic evaluation of hair in 45 neonates during their first 30 days of life, Dr. Piraccini and colleagues found that 70% had low density hair while the remaining 30% had high density hair (Br J Dermatol 2013; 169:896-900). Two neonates presented a frontal-temporal pattern of hair loss. Trichoscopy revealed that nine neonates, all in the poor hair density group, had a particular hair shaft dermoscopic feature, characterized by the presence of widespread thin hair.

In some children, she continued, hair in the occipital area does not enter the telogen phase until after birth. These hairs remain on the scalp for 8-12 weeks and then fall out, resulting in neonatal occipital alopecia, which is the most common form of transient neonatal hair loss. Neonatal occipital alopecia is characterized by a band-like shape or oval alopecic patch with a sharp lower margin, but it often goes unnoticed by parents.

“It occurs with higher prevalence in infants born to mothers younger than age 34, in those with a non-cesarean birth, and in those with a gestational age greater than 37 weeks,” Dr. Piraccini said. “There are different degrees of severity. On trichoscopy, the condition appears as thin regrowing hair. The outcome is totally benign, with normal hair growth within the first year of life.”

Any aspect of alopecia in the occipital area in young children may be a sign of hair shaft disorders, which are characterized by increased hair fragility. “Trichoscopy is diagnostic,” she said. “When applied to the hair you see monilethrix, a rare inherited disorder characterized by sparse, brittle hair that often breaks before reaching a few inches in length. As the child grows, the hair gradually acquires the characteristics it will have in adulthood. “It may remain thin and with a short anagen phase for several years, but acute shedding is rare,” she said.

When an older child presents with increased hair shedding, the first exam to perform is the pull test. If it results in painless traction of several anagen hair without sheaths and with ragged cuticles, think about loose anagen hair syndrome. This condition affects females more than males, usually occurs between the ages of 2 and 5, and is characterized by a defective anchoring of the hair shaft to the hair follicle. The three clinical types of loose anagen hair syndrome are short, rough sparse hair; increased shedding; and areas of alopecia. The syndrome “tends to be inherited but spontaneously improves with aging,” Dr. Piraccini said.

Alopecia areata, another common pediatric hair disorder, occurs in 20% of patients younger than 16 years of age and 9% of those with Down syndrome, and is associated with a family history of the condition. Young age at onset is a negative prognostic factor. “On trichoscopy, common features of alopecia areata are yellow dots, black dots, exclamation mark hairs, and broken hair,” she said. “Trichoscopy can also help you distinguish acute from chronic alopecia areata. The risk of relapse is common, and psychological support is mandatory, because it is very stressful for children.”

Another form of patchy alopecia, trichotillomania, occurs mainly in school-aged children and appears as irregular patches of alopecia with hairs broken at different lengths. “The pull test is negative because all telogen hairs have been pulled out by the patient,” Dr. Piraccini said. “Parents often do not accept the diagnosis as they do not see the child touching his or her hair. It has a good prognosis.”

Trichoscopic signs of trichotillomania include black dots, hair broken at different length, flame hair, clots of hair, and tulip hair. Treatment typically consists of psychological counseling and N-acetylcysteine 600-2,400 g/day.

Dr. Piraccini reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

In the clinical experience of Bianca Maria Piraccini, MD,

Dermoscopic imaging, also known as trichoscopy, “avoids invasive procedures and provides immediate results,” Dr. Piraccini, of the University of Bologna’s division of dermatology in the department of experimental, diagnostic, and specialty medicine, said during the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is helpful for diagnosing all sorts of alopecia, starting with those that appear at birth, such as aplasia cutis congenita to those that appear in adolescence, such as androgenetic alopecia.”

Dr. Piraccini noted that lanugo hair is produced at 16-20 weeks’ gestation and is shed in utero and replaced by thicker hair at 32-36 weeks. “The speed of transition from vellus to intermediate and terminal hair varies from child to child,” she said. “The scalp at birth presents with thin, intermediate, or thick hair.”

In a dermoscopic evaluation of hair in 45 neonates during their first 30 days of life, Dr. Piraccini and colleagues found that 70% had low density hair while the remaining 30% had high density hair (Br J Dermatol 2013; 169:896-900). Two neonates presented a frontal-temporal pattern of hair loss. Trichoscopy revealed that nine neonates, all in the poor hair density group, had a particular hair shaft dermoscopic feature, characterized by the presence of widespread thin hair.

In some children, she continued, hair in the occipital area does not enter the telogen phase until after birth. These hairs remain on the scalp for 8-12 weeks and then fall out, resulting in neonatal occipital alopecia, which is the most common form of transient neonatal hair loss. Neonatal occipital alopecia is characterized by a band-like shape or oval alopecic patch with a sharp lower margin, but it often goes unnoticed by parents.

“It occurs with higher prevalence in infants born to mothers younger than age 34, in those with a non-cesarean birth, and in those with a gestational age greater than 37 weeks,” Dr. Piraccini said. “There are different degrees of severity. On trichoscopy, the condition appears as thin regrowing hair. The outcome is totally benign, with normal hair growth within the first year of life.”

Any aspect of alopecia in the occipital area in young children may be a sign of hair shaft disorders, which are characterized by increased hair fragility. “Trichoscopy is diagnostic,” she said. “When applied to the hair you see monilethrix, a rare inherited disorder characterized by sparse, brittle hair that often breaks before reaching a few inches in length. As the child grows, the hair gradually acquires the characteristics it will have in adulthood. “It may remain thin and with a short anagen phase for several years, but acute shedding is rare,” she said.

When an older child presents with increased hair shedding, the first exam to perform is the pull test. If it results in painless traction of several anagen hair without sheaths and with ragged cuticles, think about loose anagen hair syndrome. This condition affects females more than males, usually occurs between the ages of 2 and 5, and is characterized by a defective anchoring of the hair shaft to the hair follicle. The three clinical types of loose anagen hair syndrome are short, rough sparse hair; increased shedding; and areas of alopecia. The syndrome “tends to be inherited but spontaneously improves with aging,” Dr. Piraccini said.

Alopecia areata, another common pediatric hair disorder, occurs in 20% of patients younger than 16 years of age and 9% of those with Down syndrome, and is associated with a family history of the condition. Young age at onset is a negative prognostic factor. “On trichoscopy, common features of alopecia areata are yellow dots, black dots, exclamation mark hairs, and broken hair,” she said. “Trichoscopy can also help you distinguish acute from chronic alopecia areata. The risk of relapse is common, and psychological support is mandatory, because it is very stressful for children.”

Another form of patchy alopecia, trichotillomania, occurs mainly in school-aged children and appears as irregular patches of alopecia with hairs broken at different lengths. “The pull test is negative because all telogen hairs have been pulled out by the patient,” Dr. Piraccini said. “Parents often do not accept the diagnosis as they do not see the child touching his or her hair. It has a good prognosis.”

Trichoscopic signs of trichotillomania include black dots, hair broken at different length, flame hair, clots of hair, and tulip hair. Treatment typically consists of psychological counseling and N-acetylcysteine 600-2,400 g/day.

Dr. Piraccini reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

In the clinical experience of Bianca Maria Piraccini, MD,

Dermoscopic imaging, also known as trichoscopy, “avoids invasive procedures and provides immediate results,” Dr. Piraccini, of the University of Bologna’s division of dermatology in the department of experimental, diagnostic, and specialty medicine, said during the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is helpful for diagnosing all sorts of alopecia, starting with those that appear at birth, such as aplasia cutis congenita to those that appear in adolescence, such as androgenetic alopecia.”

Dr. Piraccini noted that lanugo hair is produced at 16-20 weeks’ gestation and is shed in utero and replaced by thicker hair at 32-36 weeks. “The speed of transition from vellus to intermediate and terminal hair varies from child to child,” she said. “The scalp at birth presents with thin, intermediate, or thick hair.”

In a dermoscopic evaluation of hair in 45 neonates during their first 30 days of life, Dr. Piraccini and colleagues found that 70% had low density hair while the remaining 30% had high density hair (Br J Dermatol 2013; 169:896-900). Two neonates presented a frontal-temporal pattern of hair loss. Trichoscopy revealed that nine neonates, all in the poor hair density group, had a particular hair shaft dermoscopic feature, characterized by the presence of widespread thin hair.

In some children, she continued, hair in the occipital area does not enter the telogen phase until after birth. These hairs remain on the scalp for 8-12 weeks and then fall out, resulting in neonatal occipital alopecia, which is the most common form of transient neonatal hair loss. Neonatal occipital alopecia is characterized by a band-like shape or oval alopecic patch with a sharp lower margin, but it often goes unnoticed by parents.

“It occurs with higher prevalence in infants born to mothers younger than age 34, in those with a non-cesarean birth, and in those with a gestational age greater than 37 weeks,” Dr. Piraccini said. “There are different degrees of severity. On trichoscopy, the condition appears as thin regrowing hair. The outcome is totally benign, with normal hair growth within the first year of life.”

Any aspect of alopecia in the occipital area in young children may be a sign of hair shaft disorders, which are characterized by increased hair fragility. “Trichoscopy is diagnostic,” she said. “When applied to the hair you see monilethrix, a rare inherited disorder characterized by sparse, brittle hair that often breaks before reaching a few inches in length. As the child grows, the hair gradually acquires the characteristics it will have in adulthood. “It may remain thin and with a short anagen phase for several years, but acute shedding is rare,” she said.

When an older child presents with increased hair shedding, the first exam to perform is the pull test. If it results in painless traction of several anagen hair without sheaths and with ragged cuticles, think about loose anagen hair syndrome. This condition affects females more than males, usually occurs between the ages of 2 and 5, and is characterized by a defective anchoring of the hair shaft to the hair follicle. The three clinical types of loose anagen hair syndrome are short, rough sparse hair; increased shedding; and areas of alopecia. The syndrome “tends to be inherited but spontaneously improves with aging,” Dr. Piraccini said.

Alopecia areata, another common pediatric hair disorder, occurs in 20% of patients younger than 16 years of age and 9% of those with Down syndrome, and is associated with a family history of the condition. Young age at onset is a negative prognostic factor. “On trichoscopy, common features of alopecia areata are yellow dots, black dots, exclamation mark hairs, and broken hair,” she said. “Trichoscopy can also help you distinguish acute from chronic alopecia areata. The risk of relapse is common, and psychological support is mandatory, because it is very stressful for children.”

Another form of patchy alopecia, trichotillomania, occurs mainly in school-aged children and appears as irregular patches of alopecia with hairs broken at different lengths. “The pull test is negative because all telogen hairs have been pulled out by the patient,” Dr. Piraccini said. “Parents often do not accept the diagnosis as they do not see the child touching his or her hair. It has a good prognosis.”

Trichoscopic signs of trichotillomania include black dots, hair broken at different length, flame hair, clots of hair, and tulip hair. Treatment typically consists of psychological counseling and N-acetylcysteine 600-2,400 g/day.

Dr. Piraccini reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM SPD 2020

New psoriasis guidelines focus on topical and alternative treatments, and severity measures

and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

The guidelines, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, focus on treatment for adults, and follow the release of other AAD-NPF guidelines on biologics for psoriasis, psoriasis-related comorbidities, pediatric psoriasis, and phototherapy in 2019, and earlier this year, guidelines for systemic nonbiologic treatments. The latest guidelines’ section on topical treatment outlines evidence for the efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse events related to topical steroids, topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, vitamin D analogues, tazarotene, moisturizers, salicylic acid, anthralin, coal tar, combinations with biologic agents, and combinations with nonbiologic treatments (methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and apremilast).

The guidelines noted the “key role” of topical corticosteroids in treating psoriasis “especially for localized disease,” and include a review of the data on low-, moderate-, high-, and ultrahigh-potency topical steroids for psoriasis.

In general, all topical steroids can be used in combination with biologics, according to the guidelines, but the strongest recommendations based on the latest evidence include the addition of an ultra-high potency topical corticosteroid to standard dose etanercept for 12 weeks. Currently, 11 biologics are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of psoriasis.

In addition, “while not FDA approved for psoriasis, the topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are often employed in the treatment of psoriasis,” can be helpful for “thinner skin such as facial and intertriginous areas,” and can be steroid sparing when used for more than 4 weeks, according to the guidelines.

Don’t discount the role of patient preferences when choosing topical treatments, the authors noted. “The optimal vehicle choice is the one the patient is mostly likely to use.”

The guidelines also address the evidence for effectiveness, and adverse events in the use of several alternative medicines for psoriasis including traditional Chinese medicine, and the herbal therapies aloe vera and St. John’s wort, as well as the potential role of dietary supplements including fish oil, vitamin D, turmeric, and zinc in managing psoriasis, and the potential role of a gluten-free diet.

In general, research on the efficacy, effectiveness, and potential adverse effects of these strategies are limited, according to the guidelines, although many patients express interest in supplements and herbal products. For example, “Many patients ask about the overall role of vitamin D in skin health. Rather than adding oral vitamin D supplementation, topical therapy with vitamin D agents is effective for the treatment of psoriasis,” the authors noted.

In addition, they noted that mind/body strategies, namely hypnosis and stress reduction or meditation techniques, have been shown to improve symptoms and can be helpful for some patients, but clinical evidence is limited.

The guidelines also addressed methods for assessing disease severity in psoriasis. They recommended using body surface area (BSA) to assess psoriasis severity and patient response to treatment in the clinical setting. However, BSA is a provider assessment tool that “does not take into account location on the body, clinical characteristics of the plaques, symptoms, or quality of life issues,” the authors noted. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) measures erythema, induration, and scaling and is more suited to assessing psoriasis severity and response to treatment in clinical trials rather than in practice, they said.

Prior AAD guidelines on psoriasis were published more than 10 years ago, and major developments including the availability of new biologic drugs and new data on comorbidities have been recognized in the past decade, working group cochair and author of the guidelines Alan Menter, MD, said in an interview.

The key game-changers from previous guidelines include the full section published on comorbidities plus the development of two new important cytokine classes: three IL-17 drugs and three new IL-23 drugs now available for moderate to severe psoriasis, said Dr. Menter, chairman of the division of dermatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas.

Barriers to implementing the guidelines in practice may occur when “third party payers make the decision on which of the 11 biologic drugs now approved for moderate to severe psoriasis should be used,” he noted.

As for next steps in psoriasis studies, “new biomarker research is currently underway,” Dr. Menter said. With 11 biologic agents new formally approved by the FDA for moderate to severe psoriasis, the next steps are to determine which drug is likely to be the most appropriate for each individual patient.

Dr. Menter disclosed relationships with multiple companies that develop and manufacture psoriasis therapies, including Abbott Labs, AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma USA, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma US, Menlo Therapeutics, and Novartis. The updated guidelines were designed by a multidisciplinary work group of psoriasis experts including dermatologists, a rheumatologist, a cardiologist, and representatives from a patient advocacy organization.

SOURCE: Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087.

and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

The guidelines, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, focus on treatment for adults, and follow the release of other AAD-NPF guidelines on biologics for psoriasis, psoriasis-related comorbidities, pediatric psoriasis, and phototherapy in 2019, and earlier this year, guidelines for systemic nonbiologic treatments. The latest guidelines’ section on topical treatment outlines evidence for the efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse events related to topical steroids, topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, vitamin D analogues, tazarotene, moisturizers, salicylic acid, anthralin, coal tar, combinations with biologic agents, and combinations with nonbiologic treatments (methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and apremilast).

The guidelines noted the “key role” of topical corticosteroids in treating psoriasis “especially for localized disease,” and include a review of the data on low-, moderate-, high-, and ultrahigh-potency topical steroids for psoriasis.

In general, all topical steroids can be used in combination with biologics, according to the guidelines, but the strongest recommendations based on the latest evidence include the addition of an ultra-high potency topical corticosteroid to standard dose etanercept for 12 weeks. Currently, 11 biologics are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of psoriasis.

In addition, “while not FDA approved for psoriasis, the topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are often employed in the treatment of psoriasis,” can be helpful for “thinner skin such as facial and intertriginous areas,” and can be steroid sparing when used for more than 4 weeks, according to the guidelines.

Don’t discount the role of patient preferences when choosing topical treatments, the authors noted. “The optimal vehicle choice is the one the patient is mostly likely to use.”

The guidelines also address the evidence for effectiveness, and adverse events in the use of several alternative medicines for psoriasis including traditional Chinese medicine, and the herbal therapies aloe vera and St. John’s wort, as well as the potential role of dietary supplements including fish oil, vitamin D, turmeric, and zinc in managing psoriasis, and the potential role of a gluten-free diet.

In general, research on the efficacy, effectiveness, and potential adverse effects of these strategies are limited, according to the guidelines, although many patients express interest in supplements and herbal products. For example, “Many patients ask about the overall role of vitamin D in skin health. Rather than adding oral vitamin D supplementation, topical therapy with vitamin D agents is effective for the treatment of psoriasis,” the authors noted.

In addition, they noted that mind/body strategies, namely hypnosis and stress reduction or meditation techniques, have been shown to improve symptoms and can be helpful for some patients, but clinical evidence is limited.

The guidelines also addressed methods for assessing disease severity in psoriasis. They recommended using body surface area (BSA) to assess psoriasis severity and patient response to treatment in the clinical setting. However, BSA is a provider assessment tool that “does not take into account location on the body, clinical characteristics of the plaques, symptoms, or quality of life issues,” the authors noted. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) measures erythema, induration, and scaling and is more suited to assessing psoriasis severity and response to treatment in clinical trials rather than in practice, they said.

Prior AAD guidelines on psoriasis were published more than 10 years ago, and major developments including the availability of new biologic drugs and new data on comorbidities have been recognized in the past decade, working group cochair and author of the guidelines Alan Menter, MD, said in an interview.

The key game-changers from previous guidelines include the full section published on comorbidities plus the development of two new important cytokine classes: three IL-17 drugs and three new IL-23 drugs now available for moderate to severe psoriasis, said Dr. Menter, chairman of the division of dermatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas.

Barriers to implementing the guidelines in practice may occur when “third party payers make the decision on which of the 11 biologic drugs now approved for moderate to severe psoriasis should be used,” he noted.

As for next steps in psoriasis studies, “new biomarker research is currently underway,” Dr. Menter said. With 11 biologic agents new formally approved by the FDA for moderate to severe psoriasis, the next steps are to determine which drug is likely to be the most appropriate for each individual patient.

Dr. Menter disclosed relationships with multiple companies that develop and manufacture psoriasis therapies, including Abbott Labs, AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma USA, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma US, Menlo Therapeutics, and Novartis. The updated guidelines were designed by a multidisciplinary work group of psoriasis experts including dermatologists, a rheumatologist, a cardiologist, and representatives from a patient advocacy organization.

SOURCE: Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087.

and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

The guidelines, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, focus on treatment for adults, and follow the release of other AAD-NPF guidelines on biologics for psoriasis, psoriasis-related comorbidities, pediatric psoriasis, and phototherapy in 2019, and earlier this year, guidelines for systemic nonbiologic treatments. The latest guidelines’ section on topical treatment outlines evidence for the efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse events related to topical steroids, topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, vitamin D analogues, tazarotene, moisturizers, salicylic acid, anthralin, coal tar, combinations with biologic agents, and combinations with nonbiologic treatments (methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and apremilast).

The guidelines noted the “key role” of topical corticosteroids in treating psoriasis “especially for localized disease,” and include a review of the data on low-, moderate-, high-, and ultrahigh-potency topical steroids for psoriasis.

In general, all topical steroids can be used in combination with biologics, according to the guidelines, but the strongest recommendations based on the latest evidence include the addition of an ultra-high potency topical corticosteroid to standard dose etanercept for 12 weeks. Currently, 11 biologics are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of psoriasis.

In addition, “while not FDA approved for psoriasis, the topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are often employed in the treatment of psoriasis,” can be helpful for “thinner skin such as facial and intertriginous areas,” and can be steroid sparing when used for more than 4 weeks, according to the guidelines.

Don’t discount the role of patient preferences when choosing topical treatments, the authors noted. “The optimal vehicle choice is the one the patient is mostly likely to use.”

The guidelines also address the evidence for effectiveness, and adverse events in the use of several alternative medicines for psoriasis including traditional Chinese medicine, and the herbal therapies aloe vera and St. John’s wort, as well as the potential role of dietary supplements including fish oil, vitamin D, turmeric, and zinc in managing psoriasis, and the potential role of a gluten-free diet.

In general, research on the efficacy, effectiveness, and potential adverse effects of these strategies are limited, according to the guidelines, although many patients express interest in supplements and herbal products. For example, “Many patients ask about the overall role of vitamin D in skin health. Rather than adding oral vitamin D supplementation, topical therapy with vitamin D agents is effective for the treatment of psoriasis,” the authors noted.

In addition, they noted that mind/body strategies, namely hypnosis and stress reduction or meditation techniques, have been shown to improve symptoms and can be helpful for some patients, but clinical evidence is limited.

The guidelines also addressed methods for assessing disease severity in psoriasis. They recommended using body surface area (BSA) to assess psoriasis severity and patient response to treatment in the clinical setting. However, BSA is a provider assessment tool that “does not take into account location on the body, clinical characteristics of the plaques, symptoms, or quality of life issues,” the authors noted. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) measures erythema, induration, and scaling and is more suited to assessing psoriasis severity and response to treatment in clinical trials rather than in practice, they said.

Prior AAD guidelines on psoriasis were published more than 10 years ago, and major developments including the availability of new biologic drugs and new data on comorbidities have been recognized in the past decade, working group cochair and author of the guidelines Alan Menter, MD, said in an interview.

The key game-changers from previous guidelines include the full section published on comorbidities plus the development of two new important cytokine classes: three IL-17 drugs and three new IL-23 drugs now available for moderate to severe psoriasis, said Dr. Menter, chairman of the division of dermatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas.

Barriers to implementing the guidelines in practice may occur when “third party payers make the decision on which of the 11 biologic drugs now approved for moderate to severe psoriasis should be used,” he noted.

As for next steps in psoriasis studies, “new biomarker research is currently underway,” Dr. Menter said. With 11 biologic agents new formally approved by the FDA for moderate to severe psoriasis, the next steps are to determine which drug is likely to be the most appropriate for each individual patient.

Dr. Menter disclosed relationships with multiple companies that develop and manufacture psoriasis therapies, including Abbott Labs, AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma USA, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma US, Menlo Therapeutics, and Novartis. The updated guidelines were designed by a multidisciplinary work group of psoriasis experts including dermatologists, a rheumatologist, a cardiologist, and representatives from a patient advocacy organization.

SOURCE: Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Biologics may delay psoriatic arthritis, study finds

(DMARDs), in a single center retrospective analysis in Argentina that followed patients for almost 2 decades.

About 30%-40% of patients with psoriasis go on to develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), usually on average about 10 years after the onset of psoriasis. One potential mechanism of PsA onset is through enthesitis, which has been described at subclinical levels in psoriasis.

“It could be speculated that treatment with biologics in patients with psoriasis could prevent the development of psoriatic arthritis, perhaps by inhibiting the subclinical development of enthesitis,” Luciano Lo Giudice, MD, a rheumatology fellow at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, said during his presentation at the virtual annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

Although these results do not prove that treatment of the underlying disease delays progression to PsA, it is suggestive, and highlights an emerging field of research, according to Diamant Thaçi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, who led a live discussion following a prerecorded presentation of the results. “We’re going in this direction – how can we prevent psoriatic arthritis, how can we delay it. We are just starting to think about this,” Dr. Thaçi said in an interview.

The researchers examined medical records of 1,626 patients with psoriasis treated at their center between 2000 and 2019, with a total of 15,152 years of follow-up. Of these patients, 1,293 were treated with topical medication, 229 with conventional DMARDs (methotrexate in 77%, cyclosporine in 13%, and both in 10%), and 104 with biologics, including etanercept (34%), secukinumab (20%), adalimumab (20%), ustekinumab (12%), ixekizumab (9%), and infliximab (5%).

They found that 11% in the topical treatment group developed PsA, as did 3.5% in the conventional DMARD group, 1.9% in the biologics group, and 9.1% overall. Treatment with biologics was associated with a significantly lower odds of developing PsA compared with treatment with conventional DMARDs (3 versus 17.2 per 1,000 patient-years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.17; P = .0177). There was a trend toward reduced odds of developing PsA among those on biologic therapy compared with those on topicals (3 versus 9.8 per 1,000 patient-years; IRR, 0.3; P = .0588).

The researchers confirmed all medical encounters using electronic medical records and the study had a long follow-up time, but was limited by the single center and its retrospective nature. It also could not associate reduced risk with specific biologics.

The findings probably reflect the presence of subclinical PsA that many clinicians don’t see, according to Dr. Thaçi. While a dermatology practice might find PsA in 2% or 3%, or at most, 10% of patients with psoriasis, “in our department it’s about 50 to 60 percent of patients who have psoriatic arthritis, because we diagnose it early,” he said.

He found the results of the study encouraging. “It looks like some of the biologics, for example IL [interleukin]-17 or even IL-23 [blockers] may have an influence on occurrence or delay the occurrence of psoriatic arthritis.”

Dr. Thaçi noted that early treatment of skin lesions can increase the probability of longer remissions, especially with IL-23 blockers. Still, that’s no guarantee the same would hold true for PsA risk. “Skin is skin and joints are joints,” Dr. Thaçi said.

Dr. Thaçi and Dr. Lo Giudice had no relevant financial disclosures.

(DMARDs), in a single center retrospective analysis in Argentina that followed patients for almost 2 decades.

About 30%-40% of patients with psoriasis go on to develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), usually on average about 10 years after the onset of psoriasis. One potential mechanism of PsA onset is through enthesitis, which has been described at subclinical levels in psoriasis.

“It could be speculated that treatment with biologics in patients with psoriasis could prevent the development of psoriatic arthritis, perhaps by inhibiting the subclinical development of enthesitis,” Luciano Lo Giudice, MD, a rheumatology fellow at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, said during his presentation at the virtual annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

Although these results do not prove that treatment of the underlying disease delays progression to PsA, it is suggestive, and highlights an emerging field of research, according to Diamant Thaçi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, who led a live discussion following a prerecorded presentation of the results. “We’re going in this direction – how can we prevent psoriatic arthritis, how can we delay it. We are just starting to think about this,” Dr. Thaçi said in an interview.

The researchers examined medical records of 1,626 patients with psoriasis treated at their center between 2000 and 2019, with a total of 15,152 years of follow-up. Of these patients, 1,293 were treated with topical medication, 229 with conventional DMARDs (methotrexate in 77%, cyclosporine in 13%, and both in 10%), and 104 with biologics, including etanercept (34%), secukinumab (20%), adalimumab (20%), ustekinumab (12%), ixekizumab (9%), and infliximab (5%).

They found that 11% in the topical treatment group developed PsA, as did 3.5% in the conventional DMARD group, 1.9% in the biologics group, and 9.1% overall. Treatment with biologics was associated with a significantly lower odds of developing PsA compared with treatment with conventional DMARDs (3 versus 17.2 per 1,000 patient-years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.17; P = .0177). There was a trend toward reduced odds of developing PsA among those on biologic therapy compared with those on topicals (3 versus 9.8 per 1,000 patient-years; IRR, 0.3; P = .0588).

The researchers confirmed all medical encounters using electronic medical records and the study had a long follow-up time, but was limited by the single center and its retrospective nature. It also could not associate reduced risk with specific biologics.

The findings probably reflect the presence of subclinical PsA that many clinicians don’t see, according to Dr. Thaçi. While a dermatology practice might find PsA in 2% or 3%, or at most, 10% of patients with psoriasis, “in our department it’s about 50 to 60 percent of patients who have psoriatic arthritis, because we diagnose it early,” he said.

He found the results of the study encouraging. “It looks like some of the biologics, for example IL [interleukin]-17 or even IL-23 [blockers] may have an influence on occurrence or delay the occurrence of psoriatic arthritis.”

Dr. Thaçi noted that early treatment of skin lesions can increase the probability of longer remissions, especially with IL-23 blockers. Still, that’s no guarantee the same would hold true for PsA risk. “Skin is skin and joints are joints,” Dr. Thaçi said.

Dr. Thaçi and Dr. Lo Giudice had no relevant financial disclosures.

(DMARDs), in a single center retrospective analysis in Argentina that followed patients for almost 2 decades.

About 30%-40% of patients with psoriasis go on to develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), usually on average about 10 years after the onset of psoriasis. One potential mechanism of PsA onset is through enthesitis, which has been described at subclinical levels in psoriasis.

“It could be speculated that treatment with biologics in patients with psoriasis could prevent the development of psoriatic arthritis, perhaps by inhibiting the subclinical development of enthesitis,” Luciano Lo Giudice, MD, a rheumatology fellow at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, said during his presentation at the virtual annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

Although these results do not prove that treatment of the underlying disease delays progression to PsA, it is suggestive, and highlights an emerging field of research, according to Diamant Thaçi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, who led a live discussion following a prerecorded presentation of the results. “We’re going in this direction – how can we prevent psoriatic arthritis, how can we delay it. We are just starting to think about this,” Dr. Thaçi said in an interview.

The researchers examined medical records of 1,626 patients with psoriasis treated at their center between 2000 and 2019, with a total of 15,152 years of follow-up. Of these patients, 1,293 were treated with topical medication, 229 with conventional DMARDs (methotrexate in 77%, cyclosporine in 13%, and both in 10%), and 104 with biologics, including etanercept (34%), secukinumab (20%), adalimumab (20%), ustekinumab (12%), ixekizumab (9%), and infliximab (5%).

They found that 11% in the topical treatment group developed PsA, as did 3.5% in the conventional DMARD group, 1.9% in the biologics group, and 9.1% overall. Treatment with biologics was associated with a significantly lower odds of developing PsA compared with treatment with conventional DMARDs (3 versus 17.2 per 1,000 patient-years; incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.17; P = .0177). There was a trend toward reduced odds of developing PsA among those on biologic therapy compared with those on topicals (3 versus 9.8 per 1,000 patient-years; IRR, 0.3; P = .0588).

The researchers confirmed all medical encounters using electronic medical records and the study had a long follow-up time, but was limited by the single center and its retrospective nature. It also could not associate reduced risk with specific biologics.

The findings probably reflect the presence of subclinical PsA that many clinicians don’t see, according to Dr. Thaçi. While a dermatology practice might find PsA in 2% or 3%, or at most, 10% of patients with psoriasis, “in our department it’s about 50 to 60 percent of patients who have psoriatic arthritis, because we diagnose it early,” he said.

He found the results of the study encouraging. “It looks like some of the biologics, for example IL [interleukin]-17 or even IL-23 [blockers] may have an influence on occurrence or delay the occurrence of psoriatic arthritis.”

Dr. Thaçi noted that early treatment of skin lesions can increase the probability of longer remissions, especially with IL-23 blockers. Still, that’s no guarantee the same would hold true for PsA risk. “Skin is skin and joints are joints,” Dr. Thaçi said.

Dr. Thaçi and Dr. Lo Giudice had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM GRAPPA 2020 VIRTUAL ANNUAL MEETING

COVID-19–related skin changes: The hidden racism in documentation

Belatedly, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on patients of color is getting attention. By now, we’ve read the headlines. Black people in the United States make up about 13% of the population but account for almost three times (34%) as many deaths. This story repeats – in other countries and in other minority communities.

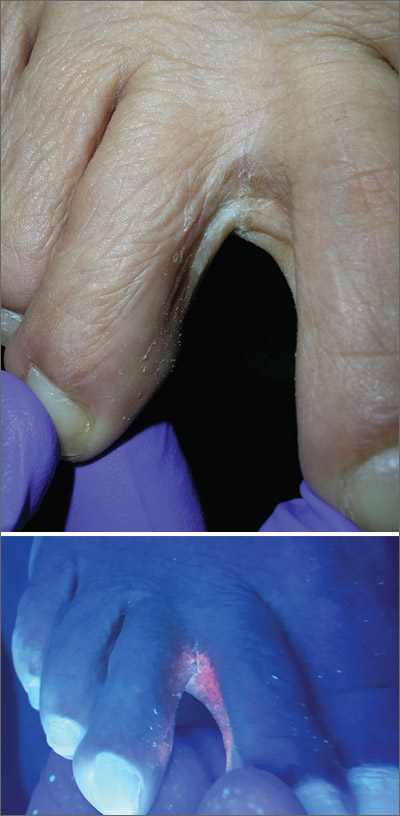

Early detection is critical both to initiate supportive care and to isolate affected individuals and limit spread. Skin manifestations of COVID-19, especially those that occur early in the disease (eg, vesicular eruptions) or have prognostic significance (livedo, retiform purpura, necrosis), are critical to this goal of early recognition.

In this context, a recent systematic literature review looked at all articles describing skin manifestations associated with COVID-19. The investigators identified 46 articles published between March and May 2020 which included a total of 130 clinical images.

The following findings from this study are striking:

- 92% of the published images of COVID-associated skin manifestations were in I-III.

- Only 6% of COVID skin lesions included in the articles were in patients with skin type IV.

- None showed COVID skin lesions in skin types V or VI.

- Only six of the articles reported race and ethnicity demographics. In those, 91% of the patients were White and 9% were Hispanic.

These results reveal a critical lack of representative clinical images of COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color. This deficiency is made all the more egregious given the fact that patients of color, including those who are Black, Latinx, and Native American, have been especially hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and suffer disproportionate disease-related morbidity and mortality.

As the study authors point out, skin manifestations in people of color often differ significantly from findings in White skin (for example, look at the figure depicting the rash typical of Kawasaki disease in a dark-skinned child compared with a light-skinned child). It is not a stretch to suggest that skin manifestations associated with COVID-19 may look very different in darker skin.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. Almost half of dermatologists feel that they’ve had insufficient exposure to skin disease in darker skin types. Skin of color remains underrepresented in medical journals.

Like other forms of passive, institutional racism, this deficiency will only be improved if dermatologists and dermatology publications actively seek out COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color and prioritize sharing these images. A medical student in the United Kingdom has gotten the ball rolling, compiling a handbook of clinical signs in darker skin types as part of a student-staff partnership at St. George’s Hospital and the University of London. At this time, Mind the Gap is looking for a publisher.

Dr. Lipper is an assistant clinical professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a staff physician in the department of dermatology at Danbury (Conn.) Hospital. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Belatedly, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on patients of color is getting attention. By now, we’ve read the headlines. Black people in the United States make up about 13% of the population but account for almost three times (34%) as many deaths. This story repeats – in other countries and in other minority communities.

Early detection is critical both to initiate supportive care and to isolate affected individuals and limit spread. Skin manifestations of COVID-19, especially those that occur early in the disease (eg, vesicular eruptions) or have prognostic significance (livedo, retiform purpura, necrosis), are critical to this goal of early recognition.

In this context, a recent systematic literature review looked at all articles describing skin manifestations associated with COVID-19. The investigators identified 46 articles published between March and May 2020 which included a total of 130 clinical images.

The following findings from this study are striking:

- 92% of the published images of COVID-associated skin manifestations were in I-III.

- Only 6% of COVID skin lesions included in the articles were in patients with skin type IV.

- None showed COVID skin lesions in skin types V or VI.

- Only six of the articles reported race and ethnicity demographics. In those, 91% of the patients were White and 9% were Hispanic.

These results reveal a critical lack of representative clinical images of COVID-associated skin manifestations in patients of color. This deficiency is made all the more egregious given the fact that patients of color, including those who are Black, Latinx, and Native American, have been especially hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and suffer disproportionate disease-related morbidity and mortality.

As the study authors point out, skin manifestations in people of color often differ significantly from findings in White skin (for example, look at the figure depicting the rash typical of Kawasaki disease in a dark-skinned child compared with a light-skinned child). It is not a stretch to suggest that skin manifestations associated with COVID-19 may look very different in darker skin.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. Almost half of dermatologists feel that they’ve had insufficient exposure to skin disease in darker skin types. Skin of color remains underrepresented in medical journals.