User login

New Edition of the ‘Go-To’ Book on Diabetes Available

“Diabetes in America was written to serve as the go-to book for anything you ever wanted to know about diabetes,” says Catherine Cowie, PhD, editor and senior advisor for the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases’ Diabetes Epidemiology Program. “It’s a resource for everyone, because diabetes affects just about everyone.”

Written by recognized experts who “represent every facet of diabetes,” the book covers relevant research, data and trends, complications and related conditions, and prevention and medical care. It is “rich in data,” says Dr. Cowie, and includes cross-sectional national data, as well as smaller geographic community and longitudinal studies. This edition includes both published and unpublished data that were specifically analyzed for the book.

Clinical trial data are summarized to show the strongest evidence available for the effectiveness of interventions, but the book also emphasizes “points of hope” found through research: For example, people at high risk can prevent or delay type 2 diabetes by losing a modest amount of weight, and rates of some complications, such as lower extremity amputations, are on the decline.

Cowie says Diabetes in America is designed to be useful to a variety of readers. Patients can use it to better understand their condition or risk factors; practitioners can use it to assess patients’ risk of diabetes and associated complications; health policy makers who need “sound quantitative knowledge” can use it to guide decision making; scientists can use it to help identify areas of needed research.

To download, visit: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/diabetes-in-america-3rd-edition.

“Diabetes in America was written to serve as the go-to book for anything you ever wanted to know about diabetes,” says Catherine Cowie, PhD, editor and senior advisor for the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases’ Diabetes Epidemiology Program. “It’s a resource for everyone, because diabetes affects just about everyone.”

Written by recognized experts who “represent every facet of diabetes,” the book covers relevant research, data and trends, complications and related conditions, and prevention and medical care. It is “rich in data,” says Dr. Cowie, and includes cross-sectional national data, as well as smaller geographic community and longitudinal studies. This edition includes both published and unpublished data that were specifically analyzed for the book.

Clinical trial data are summarized to show the strongest evidence available for the effectiveness of interventions, but the book also emphasizes “points of hope” found through research: For example, people at high risk can prevent or delay type 2 diabetes by losing a modest amount of weight, and rates of some complications, such as lower extremity amputations, are on the decline.

Cowie says Diabetes in America is designed to be useful to a variety of readers. Patients can use it to better understand their condition or risk factors; practitioners can use it to assess patients’ risk of diabetes and associated complications; health policy makers who need “sound quantitative knowledge” can use it to guide decision making; scientists can use it to help identify areas of needed research.

To download, visit: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/diabetes-in-america-3rd-edition.

“Diabetes in America was written to serve as the go-to book for anything you ever wanted to know about diabetes,” says Catherine Cowie, PhD, editor and senior advisor for the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases’ Diabetes Epidemiology Program. “It’s a resource for everyone, because diabetes affects just about everyone.”

Written by recognized experts who “represent every facet of diabetes,” the book covers relevant research, data and trends, complications and related conditions, and prevention and medical care. It is “rich in data,” says Dr. Cowie, and includes cross-sectional national data, as well as smaller geographic community and longitudinal studies. This edition includes both published and unpublished data that were specifically analyzed for the book.

Clinical trial data are summarized to show the strongest evidence available for the effectiveness of interventions, but the book also emphasizes “points of hope” found through research: For example, people at high risk can prevent or delay type 2 diabetes by losing a modest amount of weight, and rates of some complications, such as lower extremity amputations, are on the decline.

Cowie says Diabetes in America is designed to be useful to a variety of readers. Patients can use it to better understand their condition or risk factors; practitioners can use it to assess patients’ risk of diabetes and associated complications; health policy makers who need “sound quantitative knowledge” can use it to guide decision making; scientists can use it to help identify areas of needed research.

To download, visit: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/diabetes-in-america-3rd-edition.

GBS in T2DM patients: Study highlights pros and cons, need for better patient selection

ORLANDO – , according to a nationwide, matched, observational cohort study in Sweden.

After 9 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality was 49% lower among 5,321 patients with T2DM compared with 5,321 matched control (183 vs. 351 deaths; hazard ratio, 0.51), as has been reported in prior studies, Vasileios Liakopoulos, MD, of the University of Gothenburg (Sweden) reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk was 34% lower (108 vs. 150 patients; HR, 0.66), fatal CVD risk was 66% lower (21 vs. 64 patients; HR, 0.34), acute myocardial infarction risk was 45% lower (51 vs. 85 events; HR, 0.55) congestive heart failure risk was 51% lower (109 vs. 225 events; HR, 0.49), and cancer risk was 22% lower (153 vs. 188 cases; HR, 0.78) in cases vs. controls, respectively.

“[As for] the diagnoses that related to diabetes, hyperglycemia was lower by 66%, admission to the hospital due to amputation was 49% lower, and we also found something relatively new – that renal disease was lower by 42%,” Dr. Liakopoulos said.

Renal disease occurred in 105 cases vs. 187 controls (HR, 0.58), with the difference between the groups intensifying after the third year of follow-up, he noted.

However, numerous adverse events occurred more often in case patients, he said.

For example, hospitalizations for psychiatric disorders were increased by 33% (317 vs. 268; HR, 1.33), alcohol-related diagnoses were nearly threefold higher (180 vs. 65; HR, 2.90), malnutrition occurred nearly three times more often (128 vs. 46 patients; HR, 2.81), and anemia occurred nearly twice as often (84 vs. 46 cases; HR, 1.92) in cases vs. controls.

Of course, all the surgery-related adverse events occurred more often in the case patients, but interestingly, those events – which included things like gastrointestinal surgery other than gastric bypass, abdominal pain, gallstones/pancreatitis, gastrointestinal ulcers and reflux, and bowel obstruction – did not occur more often in case patients than in gastric bypass patients without diabetes in other studies, he noted.

The findings were based on merged data from the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry, the Swedish National Diabetes Register, and other national databases, and persons with T2DM who had undergone gastric bypass surgery between 2007 and 2013 were matched by propensity score (based on sex, age, body mass index, and calendar time from the beginning of the study) with obese individuals who were not surgically treated for obesity. The risks of postoperative outcomes were assessed using a Cox regression model adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, and socioeconomic status, Dr. Liakopoulos said.

This study, though limited by its observational nature, minor differences in patient characteristics between the cases and controls, and potential residual confounding, confirms the benefits of gastric bypass surgery in obese patients with T2DM but also characterizes an array of both short- and long-term adverse events after bariatric surgery in these patients, he said.

“The beneficial effects of gastric bypass have been presented in terms of weight reduction, improvements in risk factors and cardiovascular disease, and mortality reduction in people with or without diabetes,” he said, noting, however, that only a few reports have addressed long-term incidence of complications after gastric bypass – and type 2 diabetes has only been addressed in small randomized studies or in low proportions in large prospective studies.

“[Based on the findings] we suggest better selection of patients for bariatric surgery, and we think improved long-term postoperative monitoring might further improve the results of such treatment,” he concluded.

Dr. Liakopoulos reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Liakopoulos V et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 131-OR.

ORLANDO – , according to a nationwide, matched, observational cohort study in Sweden.

After 9 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality was 49% lower among 5,321 patients with T2DM compared with 5,321 matched control (183 vs. 351 deaths; hazard ratio, 0.51), as has been reported in prior studies, Vasileios Liakopoulos, MD, of the University of Gothenburg (Sweden) reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk was 34% lower (108 vs. 150 patients; HR, 0.66), fatal CVD risk was 66% lower (21 vs. 64 patients; HR, 0.34), acute myocardial infarction risk was 45% lower (51 vs. 85 events; HR, 0.55) congestive heart failure risk was 51% lower (109 vs. 225 events; HR, 0.49), and cancer risk was 22% lower (153 vs. 188 cases; HR, 0.78) in cases vs. controls, respectively.

“[As for] the diagnoses that related to diabetes, hyperglycemia was lower by 66%, admission to the hospital due to amputation was 49% lower, and we also found something relatively new – that renal disease was lower by 42%,” Dr. Liakopoulos said.

Renal disease occurred in 105 cases vs. 187 controls (HR, 0.58), with the difference between the groups intensifying after the third year of follow-up, he noted.

However, numerous adverse events occurred more often in case patients, he said.

For example, hospitalizations for psychiatric disorders were increased by 33% (317 vs. 268; HR, 1.33), alcohol-related diagnoses were nearly threefold higher (180 vs. 65; HR, 2.90), malnutrition occurred nearly three times more often (128 vs. 46 patients; HR, 2.81), and anemia occurred nearly twice as often (84 vs. 46 cases; HR, 1.92) in cases vs. controls.

Of course, all the surgery-related adverse events occurred more often in the case patients, but interestingly, those events – which included things like gastrointestinal surgery other than gastric bypass, abdominal pain, gallstones/pancreatitis, gastrointestinal ulcers and reflux, and bowel obstruction – did not occur more often in case patients than in gastric bypass patients without diabetes in other studies, he noted.

The findings were based on merged data from the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry, the Swedish National Diabetes Register, and other national databases, and persons with T2DM who had undergone gastric bypass surgery between 2007 and 2013 were matched by propensity score (based on sex, age, body mass index, and calendar time from the beginning of the study) with obese individuals who were not surgically treated for obesity. The risks of postoperative outcomes were assessed using a Cox regression model adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, and socioeconomic status, Dr. Liakopoulos said.

This study, though limited by its observational nature, minor differences in patient characteristics between the cases and controls, and potential residual confounding, confirms the benefits of gastric bypass surgery in obese patients with T2DM but also characterizes an array of both short- and long-term adverse events after bariatric surgery in these patients, he said.

“The beneficial effects of gastric bypass have been presented in terms of weight reduction, improvements in risk factors and cardiovascular disease, and mortality reduction in people with or without diabetes,” he said, noting, however, that only a few reports have addressed long-term incidence of complications after gastric bypass – and type 2 diabetes has only been addressed in small randomized studies or in low proportions in large prospective studies.

“[Based on the findings] we suggest better selection of patients for bariatric surgery, and we think improved long-term postoperative monitoring might further improve the results of such treatment,” he concluded.

Dr. Liakopoulos reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Liakopoulos V et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 131-OR.

ORLANDO – , according to a nationwide, matched, observational cohort study in Sweden.

After 9 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality was 49% lower among 5,321 patients with T2DM compared with 5,321 matched control (183 vs. 351 deaths; hazard ratio, 0.51), as has been reported in prior studies, Vasileios Liakopoulos, MD, of the University of Gothenburg (Sweden) reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk was 34% lower (108 vs. 150 patients; HR, 0.66), fatal CVD risk was 66% lower (21 vs. 64 patients; HR, 0.34), acute myocardial infarction risk was 45% lower (51 vs. 85 events; HR, 0.55) congestive heart failure risk was 51% lower (109 vs. 225 events; HR, 0.49), and cancer risk was 22% lower (153 vs. 188 cases; HR, 0.78) in cases vs. controls, respectively.

“[As for] the diagnoses that related to diabetes, hyperglycemia was lower by 66%, admission to the hospital due to amputation was 49% lower, and we also found something relatively new – that renal disease was lower by 42%,” Dr. Liakopoulos said.

Renal disease occurred in 105 cases vs. 187 controls (HR, 0.58), with the difference between the groups intensifying after the third year of follow-up, he noted.

However, numerous adverse events occurred more often in case patients, he said.

For example, hospitalizations for psychiatric disorders were increased by 33% (317 vs. 268; HR, 1.33), alcohol-related diagnoses were nearly threefold higher (180 vs. 65; HR, 2.90), malnutrition occurred nearly three times more often (128 vs. 46 patients; HR, 2.81), and anemia occurred nearly twice as often (84 vs. 46 cases; HR, 1.92) in cases vs. controls.

Of course, all the surgery-related adverse events occurred more often in the case patients, but interestingly, those events – which included things like gastrointestinal surgery other than gastric bypass, abdominal pain, gallstones/pancreatitis, gastrointestinal ulcers and reflux, and bowel obstruction – did not occur more often in case patients than in gastric bypass patients without diabetes in other studies, he noted.

The findings were based on merged data from the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry, the Swedish National Diabetes Register, and other national databases, and persons with T2DM who had undergone gastric bypass surgery between 2007 and 2013 were matched by propensity score (based on sex, age, body mass index, and calendar time from the beginning of the study) with obese individuals who were not surgically treated for obesity. The risks of postoperative outcomes were assessed using a Cox regression model adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, and socioeconomic status, Dr. Liakopoulos said.

This study, though limited by its observational nature, minor differences in patient characteristics between the cases and controls, and potential residual confounding, confirms the benefits of gastric bypass surgery in obese patients with T2DM but also characterizes an array of both short- and long-term adverse events after bariatric surgery in these patients, he said.

“The beneficial effects of gastric bypass have been presented in terms of weight reduction, improvements in risk factors and cardiovascular disease, and mortality reduction in people with or without diabetes,” he said, noting, however, that only a few reports have addressed long-term incidence of complications after gastric bypass – and type 2 diabetes has only been addressed in small randomized studies or in low proportions in large prospective studies.

“[Based on the findings] we suggest better selection of patients for bariatric surgery, and we think improved long-term postoperative monitoring might further improve the results of such treatment,” he concluded.

Dr. Liakopoulos reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Liakopoulos V et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 131-OR.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Bariatric surgery lowers mortality, CVD, and renal and other risks in obese T2DM patients but also has high complication rates.

Major finding: All-cause mortality, CVD, and renal disease risks were 49%, 34%, and 42% lower, respectively, in cases vs. controls.

Study details: A matched observational cohort study of 5,321 cases and 5,321 controls.

Disclosures: Dr. Liakopoulos reported having no disclosures.

Source: Liakopoulos V et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 131-OR.

One-step gestational diabetes screening doesn’t improve outcomes

according to data from a before-and-after cohort study of women in the state of Washington.

The one-step test, a 75-g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), was recommended for all pregnant women in 2010, although the traditional two-step test – a 50-g screening glucose challenge test followed by a 100-g 3-hour OGTT – remains widely used, wrote Gaia Pocobelli, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, and her colleagues. “No randomized trial has been published comparing outcomes of the two approaches.”

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers compared data from 23,257 women who received prenatal care in Washington State between January 2009 and December 2014, including 8,363 women who received care before the guideline change, 4,103 who received care during a transition period, and 10,791 after the guideline change. Approximately 60% of the women received care from clinicians internal to Kaiser Permanente; 40% received care from external providers. Most (87%) of the internal clinicians switched to the one-step approach, the researchers said. Only 5% of external providers did so.

Overall, adopting the one-step approach was associated with a 41% increase in the diagnosis of GDM without improved maternal or neonatal outcomes, the researchers noted.

The incidence of GDM increased from 7% before the guideline change to 11% afterward for women seen by internal providers. For women seen by external providers, gestational diabetes incidence increased from 10% to 11%.

For women seen by internal providers, the use of insulin increased from 1% before the guideline change to 4% afterward; for women seen by external providers, use of insulin increased from 1.3% to 1.4% (change between the groups P less than .001).

In addition, women seen by internal providers were more likely to undergo induction of labor after the guideline change (25% to 29%), while labor induction decreased for women seen by external providers (31% to 29%) for a relative risk of 1.2.

Neonatal hypoglycemia increased from 1% to 2% among women seen by internal providers, but decreased slightly from 2.4% to 2.1% for women seen by external providers, for a relative risk of 1.77.

There were no significant differences between the women seen by internal and external providers in risk of primary cesarean section, large for gestational age, small for gestational age, or neonatal ICU admission.

The main limitation of the study was the potential confounding variables including maternal diet and exercise, and possible underreporting of risk factors such as smoking, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large study population, and the results “do not suggest a benefit of adopting the one-step over the two-step approach.

“Kaiser Permanente Washington has revised [its] guidelines to return to a two-step process. We recommend that any health care system considering switching to the one-step approach incorporate a rigorous evaluation of changes in maternal and neonatal outcomes,” Dr. Pocobelli and her associates added.

Dr. Pocobelli disclosed funding from Jazz Pharmaceuticals for work unrelated to this study. The study was supported in part by a grant from the Group Health Foundation Momentum Fund.

Diabetes is a significant global public health concern, but is especially problematic for women of reproductive age because diabetes in pregnancy can cause significant health complications for the mother and baby. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects up to 10% of pregnancies in the United States annually, and is associated with perinatal loss, operative delivery, macrosomia, hypoglycemia, respiratory distress syndrome, and metabolic derangements for the offspring. For the mother, GDM is associated with hypertensive disorders, infections, hydramnios, and increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes later in life. As the incidence of GDM continues to rise, studies examining how to reduce, manage or prevent this condition become increasingly important.

The authors’ conclusions, that adopting the one-step approach increased the number of women with diagnosed GDM but did not significantly improve maternal or neonatal outcomes, are not surprising. Since the initial publication of the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Study, upon which the International Association of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups based its recommendations to go to a one-step approach, much debate has ensued about the best method to diagnose GDM. Indeed, the National Institutes of Health convened a consensus panel to review the literature and determine whether the one-step approach should be universally adopted (the panel concluded that more information was needed, and that the current two-step approach should continue to be used).

As the authors concede, studies have shown conflicting results, and no large-scale randomized controlled trial has been conducted to date. However, the literature does not bear out the idea that the one-step approach is truly better. The current study, although including a significant number of women and a reasonable control group, only serves as yet another study to reinforce what has previously been published.

I would agree with the researchers’ conclusions that the one-step approach is not necessarily beneficial. Although the one-step approach may identify a subset of patients who might not otherwise be diagnosed with GDM, it still remains unclear whether the outcomes for these patients will be improved. Furthermore, additional testing, need for insulin or other oral antidiabetic medications, etc., would result in additional stress to the patient and the health care system. Based on the authors’ findings, and results of other studies, it remains to be determined if the effort (diagnosing additional patients with GDM) is justified medically, economically, or otherwise.

As ob.gyns., we must continually ask ourselves: “By not doing something, are we causing harm to our patients?” If we change the diagnostic criteria for GDM, thereby increasing the number of women with the condition who would then require additional care, medications, and, potentially, more complex decisions around timing and mode of delivery, we need to be certain that we are not doing harm. This, and other studies examining the use of the one- versus two-step approach have yet to demonstrate, unequivocally, that changing the criteria reduces harm, and, perhaps, might – unintentionally – cause more.

As the study authors and the NIH consensus panel concluded, more rigorous evaluation is needed; that is, a large, multicenter randomized controlled trial that examines not only the benefits during pregnancy but also the long-term benefits to women and their children.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He provided commentary on the study by Pocobelli et al. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Diabetes is a significant global public health concern, but is especially problematic for women of reproductive age because diabetes in pregnancy can cause significant health complications for the mother and baby. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects up to 10% of pregnancies in the United States annually, and is associated with perinatal loss, operative delivery, macrosomia, hypoglycemia, respiratory distress syndrome, and metabolic derangements for the offspring. For the mother, GDM is associated with hypertensive disorders, infections, hydramnios, and increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes later in life. As the incidence of GDM continues to rise, studies examining how to reduce, manage or prevent this condition become increasingly important.

The authors’ conclusions, that adopting the one-step approach increased the number of women with diagnosed GDM but did not significantly improve maternal or neonatal outcomes, are not surprising. Since the initial publication of the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Study, upon which the International Association of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups based its recommendations to go to a one-step approach, much debate has ensued about the best method to diagnose GDM. Indeed, the National Institutes of Health convened a consensus panel to review the literature and determine whether the one-step approach should be universally adopted (the panel concluded that more information was needed, and that the current two-step approach should continue to be used).

As the authors concede, studies have shown conflicting results, and no large-scale randomized controlled trial has been conducted to date. However, the literature does not bear out the idea that the one-step approach is truly better. The current study, although including a significant number of women and a reasonable control group, only serves as yet another study to reinforce what has previously been published.

I would agree with the researchers’ conclusions that the one-step approach is not necessarily beneficial. Although the one-step approach may identify a subset of patients who might not otherwise be diagnosed with GDM, it still remains unclear whether the outcomes for these patients will be improved. Furthermore, additional testing, need for insulin or other oral antidiabetic medications, etc., would result in additional stress to the patient and the health care system. Based on the authors’ findings, and results of other studies, it remains to be determined if the effort (diagnosing additional patients with GDM) is justified medically, economically, or otherwise.

As ob.gyns., we must continually ask ourselves: “By not doing something, are we causing harm to our patients?” If we change the diagnostic criteria for GDM, thereby increasing the number of women with the condition who would then require additional care, medications, and, potentially, more complex decisions around timing and mode of delivery, we need to be certain that we are not doing harm. This, and other studies examining the use of the one- versus two-step approach have yet to demonstrate, unequivocally, that changing the criteria reduces harm, and, perhaps, might – unintentionally – cause more.

As the study authors and the NIH consensus panel concluded, more rigorous evaluation is needed; that is, a large, multicenter randomized controlled trial that examines not only the benefits during pregnancy but also the long-term benefits to women and their children.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He provided commentary on the study by Pocobelli et al. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Diabetes is a significant global public health concern, but is especially problematic for women of reproductive age because diabetes in pregnancy can cause significant health complications for the mother and baby. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects up to 10% of pregnancies in the United States annually, and is associated with perinatal loss, operative delivery, macrosomia, hypoglycemia, respiratory distress syndrome, and metabolic derangements for the offspring. For the mother, GDM is associated with hypertensive disorders, infections, hydramnios, and increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes later in life. As the incidence of GDM continues to rise, studies examining how to reduce, manage or prevent this condition become increasingly important.

The authors’ conclusions, that adopting the one-step approach increased the number of women with diagnosed GDM but did not significantly improve maternal or neonatal outcomes, are not surprising. Since the initial publication of the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Study, upon which the International Association of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups based its recommendations to go to a one-step approach, much debate has ensued about the best method to diagnose GDM. Indeed, the National Institutes of Health convened a consensus panel to review the literature and determine whether the one-step approach should be universally adopted (the panel concluded that more information was needed, and that the current two-step approach should continue to be used).

As the authors concede, studies have shown conflicting results, and no large-scale randomized controlled trial has been conducted to date. However, the literature does not bear out the idea that the one-step approach is truly better. The current study, although including a significant number of women and a reasonable control group, only serves as yet another study to reinforce what has previously been published.

I would agree with the researchers’ conclusions that the one-step approach is not necessarily beneficial. Although the one-step approach may identify a subset of patients who might not otherwise be diagnosed with GDM, it still remains unclear whether the outcomes for these patients will be improved. Furthermore, additional testing, need for insulin or other oral antidiabetic medications, etc., would result in additional stress to the patient and the health care system. Based on the authors’ findings, and results of other studies, it remains to be determined if the effort (diagnosing additional patients with GDM) is justified medically, economically, or otherwise.

As ob.gyns., we must continually ask ourselves: “By not doing something, are we causing harm to our patients?” If we change the diagnostic criteria for GDM, thereby increasing the number of women with the condition who would then require additional care, medications, and, potentially, more complex decisions around timing and mode of delivery, we need to be certain that we are not doing harm. This, and other studies examining the use of the one- versus two-step approach have yet to demonstrate, unequivocally, that changing the criteria reduces harm, and, perhaps, might – unintentionally – cause more.

As the study authors and the NIH consensus panel concluded, more rigorous evaluation is needed; that is, a large, multicenter randomized controlled trial that examines not only the benefits during pregnancy but also the long-term benefits to women and their children.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He provided commentary on the study by Pocobelli et al. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

according to data from a before-and-after cohort study of women in the state of Washington.

The one-step test, a 75-g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), was recommended for all pregnant women in 2010, although the traditional two-step test – a 50-g screening glucose challenge test followed by a 100-g 3-hour OGTT – remains widely used, wrote Gaia Pocobelli, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, and her colleagues. “No randomized trial has been published comparing outcomes of the two approaches.”

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers compared data from 23,257 women who received prenatal care in Washington State between January 2009 and December 2014, including 8,363 women who received care before the guideline change, 4,103 who received care during a transition period, and 10,791 after the guideline change. Approximately 60% of the women received care from clinicians internal to Kaiser Permanente; 40% received care from external providers. Most (87%) of the internal clinicians switched to the one-step approach, the researchers said. Only 5% of external providers did so.

Overall, adopting the one-step approach was associated with a 41% increase in the diagnosis of GDM without improved maternal or neonatal outcomes, the researchers noted.

The incidence of GDM increased from 7% before the guideline change to 11% afterward for women seen by internal providers. For women seen by external providers, gestational diabetes incidence increased from 10% to 11%.

For women seen by internal providers, the use of insulin increased from 1% before the guideline change to 4% afterward; for women seen by external providers, use of insulin increased from 1.3% to 1.4% (change between the groups P less than .001).

In addition, women seen by internal providers were more likely to undergo induction of labor after the guideline change (25% to 29%), while labor induction decreased for women seen by external providers (31% to 29%) for a relative risk of 1.2.

Neonatal hypoglycemia increased from 1% to 2% among women seen by internal providers, but decreased slightly from 2.4% to 2.1% for women seen by external providers, for a relative risk of 1.77.

There were no significant differences between the women seen by internal and external providers in risk of primary cesarean section, large for gestational age, small for gestational age, or neonatal ICU admission.

The main limitation of the study was the potential confounding variables including maternal diet and exercise, and possible underreporting of risk factors such as smoking, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large study population, and the results “do not suggest a benefit of adopting the one-step over the two-step approach.

“Kaiser Permanente Washington has revised [its] guidelines to return to a two-step process. We recommend that any health care system considering switching to the one-step approach incorporate a rigorous evaluation of changes in maternal and neonatal outcomes,” Dr. Pocobelli and her associates added.

Dr. Pocobelli disclosed funding from Jazz Pharmaceuticals for work unrelated to this study. The study was supported in part by a grant from the Group Health Foundation Momentum Fund.

according to data from a before-and-after cohort study of women in the state of Washington.

The one-step test, a 75-g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), was recommended for all pregnant women in 2010, although the traditional two-step test – a 50-g screening glucose challenge test followed by a 100-g 3-hour OGTT – remains widely used, wrote Gaia Pocobelli, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, and her colleagues. “No randomized trial has been published comparing outcomes of the two approaches.”

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers compared data from 23,257 women who received prenatal care in Washington State between January 2009 and December 2014, including 8,363 women who received care before the guideline change, 4,103 who received care during a transition period, and 10,791 after the guideline change. Approximately 60% of the women received care from clinicians internal to Kaiser Permanente; 40% received care from external providers. Most (87%) of the internal clinicians switched to the one-step approach, the researchers said. Only 5% of external providers did so.

Overall, adopting the one-step approach was associated with a 41% increase in the diagnosis of GDM without improved maternal or neonatal outcomes, the researchers noted.

The incidence of GDM increased from 7% before the guideline change to 11% afterward for women seen by internal providers. For women seen by external providers, gestational diabetes incidence increased from 10% to 11%.

For women seen by internal providers, the use of insulin increased from 1% before the guideline change to 4% afterward; for women seen by external providers, use of insulin increased from 1.3% to 1.4% (change between the groups P less than .001).

In addition, women seen by internal providers were more likely to undergo induction of labor after the guideline change (25% to 29%), while labor induction decreased for women seen by external providers (31% to 29%) for a relative risk of 1.2.

Neonatal hypoglycemia increased from 1% to 2% among women seen by internal providers, but decreased slightly from 2.4% to 2.1% for women seen by external providers, for a relative risk of 1.77.

There were no significant differences between the women seen by internal and external providers in risk of primary cesarean section, large for gestational age, small for gestational age, or neonatal ICU admission.

The main limitation of the study was the potential confounding variables including maternal diet and exercise, and possible underreporting of risk factors such as smoking, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large study population, and the results “do not suggest a benefit of adopting the one-step over the two-step approach.

“Kaiser Permanente Washington has revised [its] guidelines to return to a two-step process. We recommend that any health care system considering switching to the one-step approach incorporate a rigorous evaluation of changes in maternal and neonatal outcomes,” Dr. Pocobelli and her associates added.

Dr. Pocobelli disclosed funding from Jazz Pharmaceuticals for work unrelated to this study. The study was supported in part by a grant from the Group Health Foundation Momentum Fund.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Increased diagnoses of gestational diabetes did not significantly improve maternal or fetal outcomes.

Major finding: Adoption of a one-step screening process for gestational diabetes increased diagnoses by 41%.

Study details: The data come from a before-and-after cohort study with a population of 23,257 women.

Disclosures: Dr. Pocobelli disclosed funding from Jazz Pharmaceuticals for work unrelated to this study. The study was supported in part by a grant from the Group Health Foundation Momentum Fund.

Source: Pocobelli G et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:859-67.

Elevated type 2 diabetes risk seen in PsA patients

Patients with incident psoriatic arthritis are at a significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes when compared against patients with psoriasis alone and with the general population, according to recent research published in Rheumatology.

Rachel Charlton, PhD, of the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath (England), and her colleagues performed an analysis of 6,783 incident cases of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink who were diagnosed during 1998-2014. Patients were between 18 years and 89 years old with a median age of 49 years at PsA diagnosis.

In the study, the researchers randomly matched PsA cases at a 1:4 ratio to either a cohort of general population patients with no PsA, psoriasis, or inflammatory arthritis or a cohort of patients with psoriasis but no PsA or inflammatory arthritis. Patients were followed from match to the point where they either no longer met inclusion criteria for the cohort or received a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), ischemic heart disease (IHD), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD) with a mean follow-up duration of approximately 5.5 years across all patient groups.

Patients in the PsA group had a significantly higher incidence of type 2 diabetes, compared with the general population (adjusted relative risk, 1.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.70; P = .0007) and psoriasis groups (adjusted RR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.19-1.97; P = .0009). In the PsA group, risk of CVD (adjusted RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.99-1.56; P = .06), IHD (adjusted RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.54; P = .02), and PVD (adjusted RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02-1.92; P = .04) were significantly higher than in the general population but not when compared with the psoriasis group. The overall risk of cardiovascular disease (including CVD, IHD, and PVD) for the PsA group was significantly higher (adjusted RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.48; P = .0005), compared with the general population.

“These results support the proposal in existing clinical guidelines that, in order to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA, it is important to treat inflammatory disease as well as to screen and treat traditional risk factors early in the disease course,” Ms. Charlton and her colleagues wrote in their study.

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Charlton RA et al. Rheumatology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key286.

Patients with incident psoriatic arthritis are at a significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes when compared against patients with psoriasis alone and with the general population, according to recent research published in Rheumatology.

Rachel Charlton, PhD, of the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath (England), and her colleagues performed an analysis of 6,783 incident cases of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink who were diagnosed during 1998-2014. Patients were between 18 years and 89 years old with a median age of 49 years at PsA diagnosis.

In the study, the researchers randomly matched PsA cases at a 1:4 ratio to either a cohort of general population patients with no PsA, psoriasis, or inflammatory arthritis or a cohort of patients with psoriasis but no PsA or inflammatory arthritis. Patients were followed from match to the point where they either no longer met inclusion criteria for the cohort or received a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), ischemic heart disease (IHD), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD) with a mean follow-up duration of approximately 5.5 years across all patient groups.

Patients in the PsA group had a significantly higher incidence of type 2 diabetes, compared with the general population (adjusted relative risk, 1.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.70; P = .0007) and psoriasis groups (adjusted RR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.19-1.97; P = .0009). In the PsA group, risk of CVD (adjusted RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.99-1.56; P = .06), IHD (adjusted RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.54; P = .02), and PVD (adjusted RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02-1.92; P = .04) were significantly higher than in the general population but not when compared with the psoriasis group. The overall risk of cardiovascular disease (including CVD, IHD, and PVD) for the PsA group was significantly higher (adjusted RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.48; P = .0005), compared with the general population.

“These results support the proposal in existing clinical guidelines that, in order to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA, it is important to treat inflammatory disease as well as to screen and treat traditional risk factors early in the disease course,” Ms. Charlton and her colleagues wrote in their study.

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Charlton RA et al. Rheumatology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key286.

Patients with incident psoriatic arthritis are at a significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes when compared against patients with psoriasis alone and with the general population, according to recent research published in Rheumatology.

Rachel Charlton, PhD, of the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath (England), and her colleagues performed an analysis of 6,783 incident cases of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink who were diagnosed during 1998-2014. Patients were between 18 years and 89 years old with a median age of 49 years at PsA diagnosis.

In the study, the researchers randomly matched PsA cases at a 1:4 ratio to either a cohort of general population patients with no PsA, psoriasis, or inflammatory arthritis or a cohort of patients with psoriasis but no PsA or inflammatory arthritis. Patients were followed from match to the point where they either no longer met inclusion criteria for the cohort or received a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), ischemic heart disease (IHD), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD) with a mean follow-up duration of approximately 5.5 years across all patient groups.

Patients in the PsA group had a significantly higher incidence of type 2 diabetes, compared with the general population (adjusted relative risk, 1.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.70; P = .0007) and psoriasis groups (adjusted RR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.19-1.97; P = .0009). In the PsA group, risk of CVD (adjusted RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.99-1.56; P = .06), IHD (adjusted RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.54; P = .02), and PVD (adjusted RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02-1.92; P = .04) were significantly higher than in the general population but not when compared with the psoriasis group. The overall risk of cardiovascular disease (including CVD, IHD, and PVD) for the PsA group was significantly higher (adjusted RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.48; P = .0005), compared with the general population.

“These results support the proposal in existing clinical guidelines that, in order to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA, it is important to treat inflammatory disease as well as to screen and treat traditional risk factors early in the disease course,” Ms. Charlton and her colleagues wrote in their study.

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Charlton RA et al. Rheumatology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key286.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: It is important to treat inflammatory disease as well as to screen and treat traditional cardiovascular risk factors early in the course of PsA.

Major finding: (adjusted RR = 1.53) and a general population control group (adjusted RR = 1.40).

Study details: An analysis of 6,783 patients with psoriatic arthritis in the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink who were diagnosed between 1998 and 2014.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Charlton RA et al. Rheumatology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key286.

Study suggests “alarming” diabetes med discontinuation

ORLANDO – Most patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus stop taking their medication within a year, and nearly one-third stop within the first 3 months, a retrospective analysis of claims data for more than 324,000 patients suggests.

The findings in this population of commercially insured adults are startling and highlight a need for interventions to improve treatment persistence, according to Lisa Latts, MD, deputy chief health officer for IBM Watson Health in Cambridge, Mass.

Dr. Latts and her colleagues reviewed medication claims data for 324,136 patients with at least one diagnosis for type 2 diabetes mellitus and one outpatient pharmacy claim for a type 2 diabetes medication after at least 12 prior months without such a claim.

Of those patients, 58% discontinued treatment within 12 months, 31% discontinued within the first 3 months, and 44% discontinued within 6 months, Dr. Latts reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Less than half of those patients who discontinued had a restart within the following year. So what we’re seeing here is a huge percentage of individuals who had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, were prescribed a medication, and then did not continue the medication,” she said.

Of those who discontinued within the 12-month follow-up, 27% restarted therapy within 60 days and 39% restarted therapy anytime during the 12-month follow-up (mean treatment gap, 107 days). Of those who discontinued by 3 months, 45% restarted within a year (mean treatment gap, 112 days), and of those who discontinued by 6 months, 44% restarted within a year (mean treatment gap, 119 days).

Patients included in the review, which was a collaborative effort of IBM Watson Health and the ADA, had at least 12 months of continuous enrollment in the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases between 2013 and 2017, before and after the therapy initiation date.

They had a mean age of 55 years, with 28% aged 45-54 years and 35% aged 55-64 years. About 46% were women, and all had at least one diagnosis for type 2 diabetes mellitus during the study period and at least one outpatient pharmacy claim for a type 2 diabetes medication that was prescribed to be taken for at least 30 days.

“As you would expect, far and away the majority [68%] were given metformin,” Dr. Latts said.

Other prescribed treatments after the initial diagnosis included sulfonylureas (7%), insulin (6%), dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors (6%), sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (1.5%), and a variety of combination treatments – typically metformin plus sulfonylureas (5%).

This study provides real-world evidence that a majority of patients with type 2 diabetes discontinue their treatment within 1 year – an important finding given that medication persistence is imperative for successful treatment, Dr. Latts said. She noted that prior research has shown treatment discontinuation of prescribed medication within the first year is common for a number of chronic disease treatments and is associated with poor clinical outcomes.

“If you treat diabetes, this is alarming,” she said. “These are people who should be on a diabetes med, their doctor probably thinks they’re on a diabetes med, and they’re not taking it.”

The findings are limited by factors associated with the use of administrative claims data, such as possible coding inaccuracies and missed cases in which patients paid out of pocket for medications through low-cost pharmacy offers, as well as by the 12-month window used for the study. She added that the findings may not be generalizable to uninsured or Medicare patients.

Nevertheless, the findings are concerning and may reflect misunderstandings among patients about the need to refill prescriptions after the initial supply runs out, or may relate to side effects that patients don’t report to their physicians, Sherita Golden, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said during a question-and-answer period following Dr. Latts’ presentation.

“I do treat patients with diabetes so I am very alarmed,” she said, adding that there is a need to improve communication between patients and physicians about treatment and side effects.

Dr. Latts reported relationships with Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. Her coauthors from IBM Watson and the ADA all reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Latts L et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 135-OR.

ORLANDO – Most patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus stop taking their medication within a year, and nearly one-third stop within the first 3 months, a retrospective analysis of claims data for more than 324,000 patients suggests.

The findings in this population of commercially insured adults are startling and highlight a need for interventions to improve treatment persistence, according to Lisa Latts, MD, deputy chief health officer for IBM Watson Health in Cambridge, Mass.

Dr. Latts and her colleagues reviewed medication claims data for 324,136 patients with at least one diagnosis for type 2 diabetes mellitus and one outpatient pharmacy claim for a type 2 diabetes medication after at least 12 prior months without such a claim.

Of those patients, 58% discontinued treatment within 12 months, 31% discontinued within the first 3 months, and 44% discontinued within 6 months, Dr. Latts reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Less than half of those patients who discontinued had a restart within the following year. So what we’re seeing here is a huge percentage of individuals who had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, were prescribed a medication, and then did not continue the medication,” she said.

Of those who discontinued within the 12-month follow-up, 27% restarted therapy within 60 days and 39% restarted therapy anytime during the 12-month follow-up (mean treatment gap, 107 days). Of those who discontinued by 3 months, 45% restarted within a year (mean treatment gap, 112 days), and of those who discontinued by 6 months, 44% restarted within a year (mean treatment gap, 119 days).

Patients included in the review, which was a collaborative effort of IBM Watson Health and the ADA, had at least 12 months of continuous enrollment in the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases between 2013 and 2017, before and after the therapy initiation date.

They had a mean age of 55 years, with 28% aged 45-54 years and 35% aged 55-64 years. About 46% were women, and all had at least one diagnosis for type 2 diabetes mellitus during the study period and at least one outpatient pharmacy claim for a type 2 diabetes medication that was prescribed to be taken for at least 30 days.

“As you would expect, far and away the majority [68%] were given metformin,” Dr. Latts said.

Other prescribed treatments after the initial diagnosis included sulfonylureas (7%), insulin (6%), dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors (6%), sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (1.5%), and a variety of combination treatments – typically metformin plus sulfonylureas (5%).

This study provides real-world evidence that a majority of patients with type 2 diabetes discontinue their treatment within 1 year – an important finding given that medication persistence is imperative for successful treatment, Dr. Latts said. She noted that prior research has shown treatment discontinuation of prescribed medication within the first year is common for a number of chronic disease treatments and is associated with poor clinical outcomes.

“If you treat diabetes, this is alarming,” she said. “These are people who should be on a diabetes med, their doctor probably thinks they’re on a diabetes med, and they’re not taking it.”

The findings are limited by factors associated with the use of administrative claims data, such as possible coding inaccuracies and missed cases in which patients paid out of pocket for medications through low-cost pharmacy offers, as well as by the 12-month window used for the study. She added that the findings may not be generalizable to uninsured or Medicare patients.

Nevertheless, the findings are concerning and may reflect misunderstandings among patients about the need to refill prescriptions after the initial supply runs out, or may relate to side effects that patients don’t report to their physicians, Sherita Golden, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said during a question-and-answer period following Dr. Latts’ presentation.

“I do treat patients with diabetes so I am very alarmed,” she said, adding that there is a need to improve communication between patients and physicians about treatment and side effects.

Dr. Latts reported relationships with Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. Her coauthors from IBM Watson and the ADA all reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Latts L et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 135-OR.

ORLANDO – Most patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus stop taking their medication within a year, and nearly one-third stop within the first 3 months, a retrospective analysis of claims data for more than 324,000 patients suggests.

The findings in this population of commercially insured adults are startling and highlight a need for interventions to improve treatment persistence, according to Lisa Latts, MD, deputy chief health officer for IBM Watson Health in Cambridge, Mass.

Dr. Latts and her colleagues reviewed medication claims data for 324,136 patients with at least one diagnosis for type 2 diabetes mellitus and one outpatient pharmacy claim for a type 2 diabetes medication after at least 12 prior months without such a claim.

Of those patients, 58% discontinued treatment within 12 months, 31% discontinued within the first 3 months, and 44% discontinued within 6 months, Dr. Latts reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Less than half of those patients who discontinued had a restart within the following year. So what we’re seeing here is a huge percentage of individuals who had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, were prescribed a medication, and then did not continue the medication,” she said.

Of those who discontinued within the 12-month follow-up, 27% restarted therapy within 60 days and 39% restarted therapy anytime during the 12-month follow-up (mean treatment gap, 107 days). Of those who discontinued by 3 months, 45% restarted within a year (mean treatment gap, 112 days), and of those who discontinued by 6 months, 44% restarted within a year (mean treatment gap, 119 days).

Patients included in the review, which was a collaborative effort of IBM Watson Health and the ADA, had at least 12 months of continuous enrollment in the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases between 2013 and 2017, before and after the therapy initiation date.

They had a mean age of 55 years, with 28% aged 45-54 years and 35% aged 55-64 years. About 46% were women, and all had at least one diagnosis for type 2 diabetes mellitus during the study period and at least one outpatient pharmacy claim for a type 2 diabetes medication that was prescribed to be taken for at least 30 days.

“As you would expect, far and away the majority [68%] were given metformin,” Dr. Latts said.

Other prescribed treatments after the initial diagnosis included sulfonylureas (7%), insulin (6%), dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors (6%), sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (1.5%), and a variety of combination treatments – typically metformin plus sulfonylureas (5%).

This study provides real-world evidence that a majority of patients with type 2 diabetes discontinue their treatment within 1 year – an important finding given that medication persistence is imperative for successful treatment, Dr. Latts said. She noted that prior research has shown treatment discontinuation of prescribed medication within the first year is common for a number of chronic disease treatments and is associated with poor clinical outcomes.

“If you treat diabetes, this is alarming,” she said. “These are people who should be on a diabetes med, their doctor probably thinks they’re on a diabetes med, and they’re not taking it.”

The findings are limited by factors associated with the use of administrative claims data, such as possible coding inaccuracies and missed cases in which patients paid out of pocket for medications through low-cost pharmacy offers, as well as by the 12-month window used for the study. She added that the findings may not be generalizable to uninsured or Medicare patients.

Nevertheless, the findings are concerning and may reflect misunderstandings among patients about the need to refill prescriptions after the initial supply runs out, or may relate to side effects that patients don’t report to their physicians, Sherita Golden, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said during a question-and-answer period following Dr. Latts’ presentation.

“I do treat patients with diabetes so I am very alarmed,” she said, adding that there is a need to improve communication between patients and physicians about treatment and side effects.

Dr. Latts reported relationships with Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. Her coauthors from IBM Watson and the ADA all reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Latts L et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 135-OR.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In total, 58% of patients discontinued treatment within 12 months, and just 39% of those patients restarted within 1 year.

Study details: An analysis of claims data for more than 324,000 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Latts reported relationships with Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. Her coauthors from IBM Watson and the American Diabetes Association all reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Latts L et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 135-OR.

FDA grants praliciguat Fast Track Designation for HFpEF

fraction (HFpEF), according to its developer Ironwood.

A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial is currently enrolling patients to evaluate praliciguat as a treatment for HFpEF. The trial aims to enroll about 175 patients and intends to evaluate safety and efficacy, and topline data is expected later in 2019.

Praliciguat is an oral, once-daily, soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator. It is being studied in patients with diabetic nephropathy and in patients with HFpEF. The condition affects an estimated 3 million Americans, but there are no approved therapies at this time to treat it; however, praliciguat may have the potential to treat the underlying causes by improving nitric oxide signaling, according to the press release from Ironwood.

fraction (HFpEF), according to its developer Ironwood.

A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial is currently enrolling patients to evaluate praliciguat as a treatment for HFpEF. The trial aims to enroll about 175 patients and intends to evaluate safety and efficacy, and topline data is expected later in 2019.

Praliciguat is an oral, once-daily, soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator. It is being studied in patients with diabetic nephropathy and in patients with HFpEF. The condition affects an estimated 3 million Americans, but there are no approved therapies at this time to treat it; however, praliciguat may have the potential to treat the underlying causes by improving nitric oxide signaling, according to the press release from Ironwood.

fraction (HFpEF), according to its developer Ironwood.

A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial is currently enrolling patients to evaluate praliciguat as a treatment for HFpEF. The trial aims to enroll about 175 patients and intends to evaluate safety and efficacy, and topline data is expected later in 2019.

Praliciguat is an oral, once-daily, soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator. It is being studied in patients with diabetic nephropathy and in patients with HFpEF. The condition affects an estimated 3 million Americans, but there are no approved therapies at this time to treat it; however, praliciguat may have the potential to treat the underlying causes by improving nitric oxide signaling, according to the press release from Ironwood.

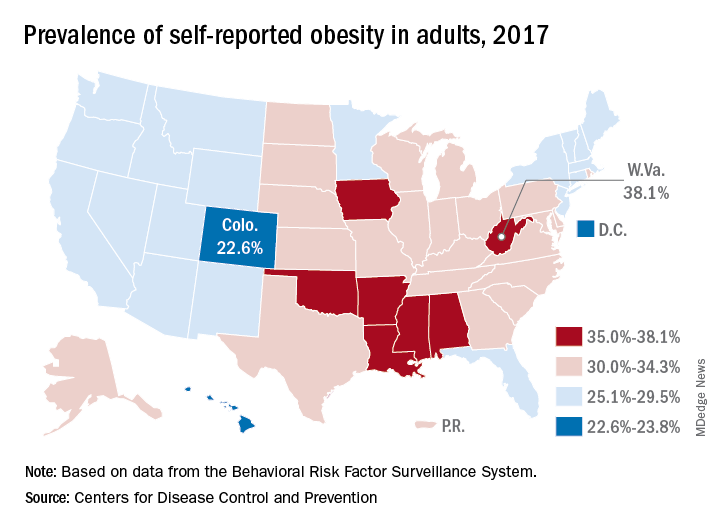

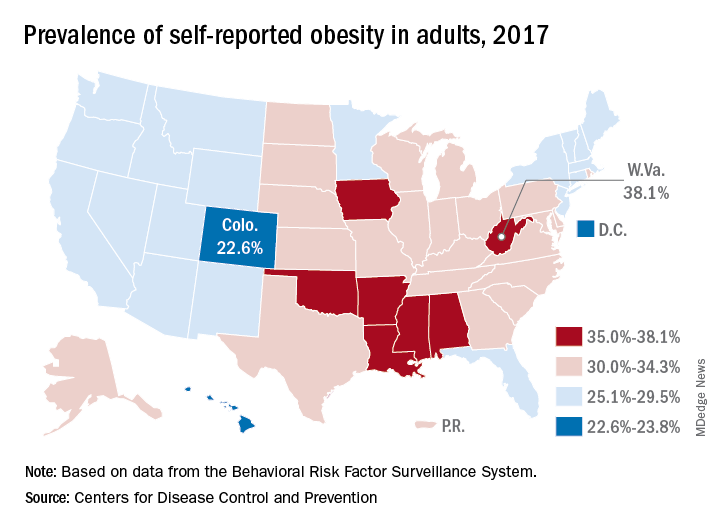

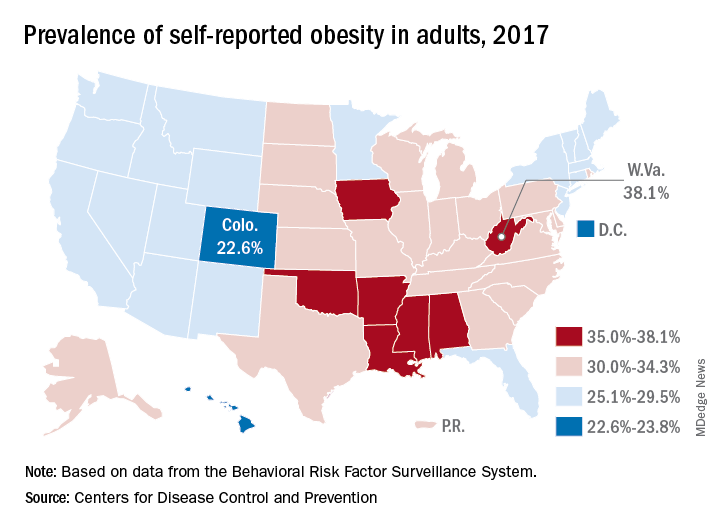

CDC: Obesity affects over 35% in 7 states

Iowa and Oklahoma, the two newest states with prevalences at or exceeding 35%, joined Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, which has the country’s highest rate of adult obesity at 38.1%. Colorado’s 22.6% rate is the lowest prevalence among all states. The District of Columbia and Hawaii also have prevalences under 25%; previously, Massachusetts also was in this group, but its prevalence went up to 25.9% last year, the CDC reported.

Regional disparities in self-reported adult obesity put the South (32.4%) and the Midwest (32.3%) well ahead of the Northeast (27.7%) and the West (26.1%) in 2017. Racial and ethnic disparities also were seen, with large gaps between blacks, who had a prevalence of 39%, and Hispanics (32.4%) and whites (29.3%). Obesity prevalence was 35% or higher among black adults in 31 states and D.C., while this was true among Hispanics in eight states and among whites in one (West Virginia), although the prevalence was at or above 35% for multiple racial groups in some of these states, the CDC reported based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Obesity costs the United States health care system over $147 billion a year [and] research has shown that obesity affects work productivity and military readiness,” the CDC said in a written statement. “To protect the health of the next generation, support for healthy behaviors such as healthy eating, better sleep, stress management, and physical activity should start early and expand to reach Americans across the lifespan in the communities where they live, learn, work, and play.”

Iowa and Oklahoma, the two newest states with prevalences at or exceeding 35%, joined Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, which has the country’s highest rate of adult obesity at 38.1%. Colorado’s 22.6% rate is the lowest prevalence among all states. The District of Columbia and Hawaii also have prevalences under 25%; previously, Massachusetts also was in this group, but its prevalence went up to 25.9% last year, the CDC reported.

Regional disparities in self-reported adult obesity put the South (32.4%) and the Midwest (32.3%) well ahead of the Northeast (27.7%) and the West (26.1%) in 2017. Racial and ethnic disparities also were seen, with large gaps between blacks, who had a prevalence of 39%, and Hispanics (32.4%) and whites (29.3%). Obesity prevalence was 35% or higher among black adults in 31 states and D.C., while this was true among Hispanics in eight states and among whites in one (West Virginia), although the prevalence was at or above 35% for multiple racial groups in some of these states, the CDC reported based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Obesity costs the United States health care system over $147 billion a year [and] research has shown that obesity affects work productivity and military readiness,” the CDC said in a written statement. “To protect the health of the next generation, support for healthy behaviors such as healthy eating, better sleep, stress management, and physical activity should start early and expand to reach Americans across the lifespan in the communities where they live, learn, work, and play.”

Iowa and Oklahoma, the two newest states with prevalences at or exceeding 35%, joined Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, which has the country’s highest rate of adult obesity at 38.1%. Colorado’s 22.6% rate is the lowest prevalence among all states. The District of Columbia and Hawaii also have prevalences under 25%; previously, Massachusetts also was in this group, but its prevalence went up to 25.9% last year, the CDC reported.

Regional disparities in self-reported adult obesity put the South (32.4%) and the Midwest (32.3%) well ahead of the Northeast (27.7%) and the West (26.1%) in 2017. Racial and ethnic disparities also were seen, with large gaps between blacks, who had a prevalence of 39%, and Hispanics (32.4%) and whites (29.3%). Obesity prevalence was 35% or higher among black adults in 31 states and D.C., while this was true among Hispanics in eight states and among whites in one (West Virginia), although the prevalence was at or above 35% for multiple racial groups in some of these states, the CDC reported based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Obesity costs the United States health care system over $147 billion a year [and] research has shown that obesity affects work productivity and military readiness,” the CDC said in a written statement. “To protect the health of the next generation, support for healthy behaviors such as healthy eating, better sleep, stress management, and physical activity should start early and expand to reach Americans across the lifespan in the communities where they live, learn, work, and play.”

Review protocols, follow reprocessing guidelines to cut device-related HAIs

ATLANTA – Ongoing vigilance regarding the role of and transmission of antimicrobial-resistant pathogen is needed, according to Isaac Benowitz, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion (DHQP).

A review of records from the DHQP, which investigates and responds to infections and related adverse events in health care settings upon invitation, showed that in 2017 environmental pathogens were most often the triggers for these investigations, said Dr. Benowitz, a medical epidemiologist.

He reviewed internal records for consultations with state and local health departments involving medical devices and collected data on health care setting, pathogen, investigation findings including possible exposure or transmission, and public health actions.

Of 285 consultations, 48 involved a specific medical device or general medical device reprocessing, he said, noting that most of those 48 were in an acute care hospital (63%) or clinic (19%).

“The most frequent pathogens noted in these consultations were nontuberculous mycobacteria at 21%, Candida species ... at 10%, and Burkholderia species ... at 8%,” he said, noting that a wide variety of devices were implicated.

In the inpatient setting these devices included ventilators, dialysis machines, breast pumps, central lines, and respiratory therapy equipment. In the outpatient setting they included glucometers and opthalmic equipment.

“In many settings we saw issues with endoscopes, including duodenoscopes, but also bronchoscopes,” he added.

Actions taken as part of the investigations included medical device recalls, improved infection control and reprocessing procedures, and patient notification, education, guidance, testing, and treatment.

In some cases there was disciplinary action or oversight for health care professionals, he added.

Investigations identified medical devices contaminated in manufacturing, incorrect reprocessing of endoscopes or ventilators, and inappropriate medical device use or reuse, he said.

A number of lessons can be learned from these and other investigations, he added.

“First, devices can be reservoirs and transmission vectors for health care–associated infections. Second, health care facilities, health care facility staff, and public health partners should take opportunities to review protocols and the practices within those protocol,” he said. “These are opportunities to strengthen infection control practices even in the absence of documented transmission.”

In fact, in most of the investigations he discussed, transmission was rarely confirmed to be associated with a medical device. This was largely because of a lack of “epidemiological rigor,” but associations between health care–associated infections and medical devices “are still quite meaningful and often actionable,” he said.

Dr. Benowitz stressed the importance of engaging public health partners to discuss findings and actions, explaining that “what may look like a single-facility issue may have a very different perspective when you realize that there’s a similar issue at another facility elsewhere.”

“For all devices, it’s important to ensure adherence to the device reprocessing guidelines, “ he added, noting that these include a combination of facility protocols, manufacturer instructions for use, and guidance from organizations like the Food and Drug Administration and the CDC.

Dr. Benowitz reported having no disclosures.

sworcester@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Benowitz I et al. ICEID 2018, Oral Abstract Presentation E2.

ATLANTA – Ongoing vigilance regarding the role of and transmission of antimicrobial-resistant pathogen is needed, according to Isaac Benowitz, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion (DHQP).

A review of records from the DHQP, which investigates and responds to infections and related adverse events in health care settings upon invitation, showed that in 2017 environmental pathogens were most often the triggers for these investigations, said Dr. Benowitz, a medical epidemiologist.

He reviewed internal records for consultations with state and local health departments involving medical devices and collected data on health care setting, pathogen, investigation findings including possible exposure or transmission, and public health actions.

Of 285 consultations, 48 involved a specific medical device or general medical device reprocessing, he said, noting that most of those 48 were in an acute care hospital (63%) or clinic (19%).

“The most frequent pathogens noted in these consultations were nontuberculous mycobacteria at 21%, Candida species ... at 10%, and Burkholderia species ... at 8%,” he said, noting that a wide variety of devices were implicated.

In the inpatient setting these devices included ventilators, dialysis machines, breast pumps, central lines, and respiratory therapy equipment. In the outpatient setting they included glucometers and opthalmic equipment.

“In many settings we saw issues with endoscopes, including duodenoscopes, but also bronchoscopes,” he added.

Actions taken as part of the investigations included medical device recalls, improved infection control and reprocessing procedures, and patient notification, education, guidance, testing, and treatment.

In some cases there was disciplinary action or oversight for health care professionals, he added.

Investigations identified medical devices contaminated in manufacturing, incorrect reprocessing of endoscopes or ventilators, and inappropriate medical device use or reuse, he said.

A number of lessons can be learned from these and other investigations, he added.

“First, devices can be reservoirs and transmission vectors for health care–associated infections. Second, health care facilities, health care facility staff, and public health partners should take opportunities to review protocols and the practices within those protocol,” he said. “These are opportunities to strengthen infection control practices even in the absence of documented transmission.”

In fact, in most of the investigations he discussed, transmission was rarely confirmed to be associated with a medical device. This was largely because of a lack of “epidemiological rigor,” but associations between health care–associated infections and medical devices “are still quite meaningful and often actionable,” he said.

Dr. Benowitz stressed the importance of engaging public health partners to discuss findings and actions, explaining that “what may look like a single-facility issue may have a very different perspective when you realize that there’s a similar issue at another facility elsewhere.”

“For all devices, it’s important to ensure adherence to the device reprocessing guidelines, “ he added, noting that these include a combination of facility protocols, manufacturer instructions for use, and guidance from organizations like the Food and Drug Administration and the CDC.

Dr. Benowitz reported having no disclosures.

sworcester@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Benowitz I et al. ICEID 2018, Oral Abstract Presentation E2.

ATLANTA – Ongoing vigilance regarding the role of and transmission of antimicrobial-resistant pathogen is needed, according to Isaac Benowitz, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion (DHQP).

A review of records from the DHQP, which investigates and responds to infections and related adverse events in health care settings upon invitation, showed that in 2017 environmental pathogens were most often the triggers for these investigations, said Dr. Benowitz, a medical epidemiologist.

He reviewed internal records for consultations with state and local health departments involving medical devices and collected data on health care setting, pathogen, investigation findings including possible exposure or transmission, and public health actions.

Of 285 consultations, 48 involved a specific medical device or general medical device reprocessing, he said, noting that most of those 48 were in an acute care hospital (63%) or clinic (19%).

“The most frequent pathogens noted in these consultations were nontuberculous mycobacteria at 21%, Candida species ... at 10%, and Burkholderia species ... at 8%,” he said, noting that a wide variety of devices were implicated.

In the inpatient setting these devices included ventilators, dialysis machines, breast pumps, central lines, and respiratory therapy equipment. In the outpatient setting they included glucometers and opthalmic equipment.

“In many settings we saw issues with endoscopes, including duodenoscopes, but also bronchoscopes,” he added.

Actions taken as part of the investigations included medical device recalls, improved infection control and reprocessing procedures, and patient notification, education, guidance, testing, and treatment.

In some cases there was disciplinary action or oversight for health care professionals, he added.

Investigations identified medical devices contaminated in manufacturing, incorrect reprocessing of endoscopes or ventilators, and inappropriate medical device use or reuse, he said.

A number of lessons can be learned from these and other investigations, he added.