User login

Prompt palliative care cut hospital costs in pooled study

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Average cost savings per admission were $3,237 overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P-values less than .001).

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of six cohort studies of 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease.

Disclosures: Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

Understanding palliative care: An important part of practicing hospital medicine

according to Brett Hendel-Paterson, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Region’s Hospital in St. Paul, Minn. and a presenter for this session.

Dr. Hendel-Paterson, Jeffrey L. Greenwald, MD, SFHM, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Jeffrey Frank, MD, MBA, of Vituity, will each present on the topic of administering palliative care as a hospitalist and why it is important for hospitalists to better understand this area of medicine.

A common misunderstanding about palliative care is that it is end-of-life care only, a misconception within both the medical and patient community. Most people believe that palliative care is associated with the “angel of death,” as Dr. Greenwald stated. Palliative care does encompass end-of-life care but is also associated with life-limiting illness. Both areas of palliative can be improved with better patient communication and symptom management.

As frontline providers at times of critical illness, and throughout illness, hospitalists are ideally positioned to provide palliative care services, Dr. Greenwald stated during an interview.

With hospitalists in such a prominent role in providing palliative care, Dr. Hendel-Paterson offered a detailed explanation about why the information from this session is important for hospitalists.

“The majority of Americans who die in this country die in hospitals. We see and we know that patients sometimes get more aggressive care leading to greater suffering in their final days,” he said. “As hospitalists, we are expected to be the primary physicians in the hospital caring for patients with a variety of health conditions. We are expected to have a basic expertise and be able to independently manage health conditions. For example, we are expected to be able to diagnose and treat pneumonia without consulting infectious disease or pulmonology specialists for basic care. In the same way, we must be able to communicate well with our patients and families and help lead them through discussions of prognosis and advance care planning. Primary palliative care refers to the skill set that includes communications about serious illness and basic symptom management.”

Dr. Greenwald expanded on Dr. Hendel-Paterson’s point concerning the growing need for hospitalists who are competent in palliative care.

“As the population ages, this issue is going to become more and more important for our field, because there isn’t a sufficient pipeline, current state – or predicted future state – of palliative care providers in hospitals to meet the need. So there’s a gap in the need, and that need is increasing.”

According to Dr. Hendel-Paterson, he and his copresenters “hope that, after this session, participants will better understand primary palliative care, take ownership of end-of-life care of their patients, and will be motivated to increase skills in areas where they are lacking.”

Building on this idea of increasing one’s skills as a hospitalist, he emphasized the importance of understanding palliative care.

“The ability to practice high-quality primary palliative care is essential to being a competent hospitalist.”

Primary Palliative Care – What Every Hospitalist Should Know

Wednesday, 10:00-10:40 a.m.

Crystal Ballroom J1

according to Brett Hendel-Paterson, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Region’s Hospital in St. Paul, Minn. and a presenter for this session.

Dr. Hendel-Paterson, Jeffrey L. Greenwald, MD, SFHM, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Jeffrey Frank, MD, MBA, of Vituity, will each present on the topic of administering palliative care as a hospitalist and why it is important for hospitalists to better understand this area of medicine.

A common misunderstanding about palliative care is that it is end-of-life care only, a misconception within both the medical and patient community. Most people believe that palliative care is associated with the “angel of death,” as Dr. Greenwald stated. Palliative care does encompass end-of-life care but is also associated with life-limiting illness. Both areas of palliative can be improved with better patient communication and symptom management.

As frontline providers at times of critical illness, and throughout illness, hospitalists are ideally positioned to provide palliative care services, Dr. Greenwald stated during an interview.

With hospitalists in such a prominent role in providing palliative care, Dr. Hendel-Paterson offered a detailed explanation about why the information from this session is important for hospitalists.

“The majority of Americans who die in this country die in hospitals. We see and we know that patients sometimes get more aggressive care leading to greater suffering in their final days,” he said. “As hospitalists, we are expected to be the primary physicians in the hospital caring for patients with a variety of health conditions. We are expected to have a basic expertise and be able to independently manage health conditions. For example, we are expected to be able to diagnose and treat pneumonia without consulting infectious disease or pulmonology specialists for basic care. In the same way, we must be able to communicate well with our patients and families and help lead them through discussions of prognosis and advance care planning. Primary palliative care refers to the skill set that includes communications about serious illness and basic symptom management.”

Dr. Greenwald expanded on Dr. Hendel-Paterson’s point concerning the growing need for hospitalists who are competent in palliative care.

“As the population ages, this issue is going to become more and more important for our field, because there isn’t a sufficient pipeline, current state – or predicted future state – of palliative care providers in hospitals to meet the need. So there’s a gap in the need, and that need is increasing.”

According to Dr. Hendel-Paterson, he and his copresenters “hope that, after this session, participants will better understand primary palliative care, take ownership of end-of-life care of their patients, and will be motivated to increase skills in areas where they are lacking.”

Building on this idea of increasing one’s skills as a hospitalist, he emphasized the importance of understanding palliative care.

“The ability to practice high-quality primary palliative care is essential to being a competent hospitalist.”

Primary Palliative Care – What Every Hospitalist Should Know

Wednesday, 10:00-10:40 a.m.

Crystal Ballroom J1

according to Brett Hendel-Paterson, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Region’s Hospital in St. Paul, Minn. and a presenter for this session.

Dr. Hendel-Paterson, Jeffrey L. Greenwald, MD, SFHM, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Jeffrey Frank, MD, MBA, of Vituity, will each present on the topic of administering palliative care as a hospitalist and why it is important for hospitalists to better understand this area of medicine.

A common misunderstanding about palliative care is that it is end-of-life care only, a misconception within both the medical and patient community. Most people believe that palliative care is associated with the “angel of death,” as Dr. Greenwald stated. Palliative care does encompass end-of-life care but is also associated with life-limiting illness. Both areas of palliative can be improved with better patient communication and symptom management.

As frontline providers at times of critical illness, and throughout illness, hospitalists are ideally positioned to provide palliative care services, Dr. Greenwald stated during an interview.

With hospitalists in such a prominent role in providing palliative care, Dr. Hendel-Paterson offered a detailed explanation about why the information from this session is important for hospitalists.

“The majority of Americans who die in this country die in hospitals. We see and we know that patients sometimes get more aggressive care leading to greater suffering in their final days,” he said. “As hospitalists, we are expected to be the primary physicians in the hospital caring for patients with a variety of health conditions. We are expected to have a basic expertise and be able to independently manage health conditions. For example, we are expected to be able to diagnose and treat pneumonia without consulting infectious disease or pulmonology specialists for basic care. In the same way, we must be able to communicate well with our patients and families and help lead them through discussions of prognosis and advance care planning. Primary palliative care refers to the skill set that includes communications about serious illness and basic symptom management.”

Dr. Greenwald expanded on Dr. Hendel-Paterson’s point concerning the growing need for hospitalists who are competent in palliative care.

“As the population ages, this issue is going to become more and more important for our field, because there isn’t a sufficient pipeline, current state – or predicted future state – of palliative care providers in hospitals to meet the need. So there’s a gap in the need, and that need is increasing.”

According to Dr. Hendel-Paterson, he and his copresenters “hope that, after this session, participants will better understand primary palliative care, take ownership of end-of-life care of their patients, and will be motivated to increase skills in areas where they are lacking.”

Building on this idea of increasing one’s skills as a hospitalist, he emphasized the importance of understanding palliative care.

“The ability to practice high-quality primary palliative care is essential to being a competent hospitalist.”

Primary Palliative Care – What Every Hospitalist Should Know

Wednesday, 10:00-10:40 a.m.

Crystal Ballroom J1

How well do POLST forms assure that patients get the end-of-life care they requested?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The POLST form offers choices within 4 treatment areas: “attempt CPR” or “allow natural death” if the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest; “comfort,” “limited,” or “full” medical interventions if pulse or breathing is present; choices of additional orders, including intravenous fluids, feeding tubes, and antibiotics; and additional written orders. Most POLST studies used cross-sectional and retrospective cohort designs and assessed whether CPR was attempted. Fewer studies also evaluated adherence to orders in the other treatment areas.

Community settings: Patients with POLST more likely to die out of hospital

The largest study of POLST use in community settings evaluated deaths in Oregon over one year.1 It found that patients who indicated “do not attempt CPR” on a POLST form were 6 times more likely to die a natural, out-of-hospital death than those who had no POLST form (TABLE1-10).

A West Virginia study found that patients with POLST forms had 30% higher out-of-hospital death rates than those with traditional advanced directives and no POLST.2 In a Wisconsin study, no decedents who indicated DNR on their POLST forms received CPR.3

One study that evaluated the consistency of actual medical interventions with POLST orders in all 4 treatment areas found it to be good in most areas (“feeding tubes,” “attempting CPR.” “antibiotics,” and “IV fluids”) except “additional written orders.4

Skilled nursing facilities: Generally high adherence to POLST orders

The largest study to evaluate the consistency of treatments with POLST orders among nursing home residents found high adherence overall (94%).5 Caregivers performed CPR on none of 299 residents who selected “DNR.” However, they did not administer CPR to 6 of 7 who chose “attempt CPR” and administered antibiotics to 32% of patients who specified “no antibiotics” on their POLST forms.5

A second study of nursing home residents who selected “comfort measures only” also found high consistency for attempting CPR, intensive care admission, and ventilator support, although physicians hospitalized 2% of patients to extend life.6 Similarly, treatments matched POLST orders well overall in a Washington state study, although one patient got a feeding tube against orders.7

POLST adherence is good, but can EMS workers find the form?

A study comparing emergency medical services (EMS) management with POLST orders in an Oregon registry found good consistency.8 EMS providers didn’t attempt or halted CPR in most patients with DNR orders who were found in cardiac arrest and initiated CPR in most patients who chose “attempt CPR.” EMS providers initiated CPR in the field on 11 patients (22%) with a DNR order but discontinued resuscitation en route to the hospital.

In a smaller study, EMS providers never located paper POLST forms at the scene in most cases.9

Hospice: POLST orders prevent unwanted Tx, except maybe antibiotics

A study evaluating management in hospice programs in 3 states found that care providers followed POLST orders for limited treatment in 98% of cases.10 No patients received unwanted CPR, intubation, or feeding tubes. POLST orders didn’t predict whether patients were treated with antibiotics, however.

1. Fromme EK, Zive D, Schmidt TA, et al. Association between physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for scope of treatment and in-hospital death in Oregon. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1246-1251.

2. Pedraza SL, Culp S, Falkenstine EC, et al. POST forms more than advance directives associated with out-of-hospital death: insights from a state registry. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016; 51:240-246.

3. Hammes B, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD, et al. The POLST program: a retrospective review of the demographics of use and outcomes in one community where advance directives are prevalent. J Palliative Med. 2012;15:77-85.

4. Lee MA, Brummel-Smith K, Meyer J, et al. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): outcomes in a PACE program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1219-1225.

5. Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2091-2099.

6. Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Nelson CA, et al. A prospective study of the efficacy of the physician order form for life sustaining treatment. J Am Ger Soc.1998;46:1097-1102.

7. Meyers J, Moore C, McGrory A, et al. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form: honoring end-of-life directives for nursing home residents. J Geron Nursing. 2004;30:37-46.

8. Richardson DK, Fromme E, Zive D, et al. Concordance of out-of-hospital and emergency department cardiac arrest resuscitation with documented end-of-life choices in Oregon. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:375-383.

9. Schmidt T, Olszewski EA, Zive D, et al. The Oregon physician orders for life-sustaining treatment registry: a preliminary study of emergency medical services utilization. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:796-805.

10. Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. Use of the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice setting. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:133-141.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The POLST form offers choices within 4 treatment areas: “attempt CPR” or “allow natural death” if the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest; “comfort,” “limited,” or “full” medical interventions if pulse or breathing is present; choices of additional orders, including intravenous fluids, feeding tubes, and antibiotics; and additional written orders. Most POLST studies used cross-sectional and retrospective cohort designs and assessed whether CPR was attempted. Fewer studies also evaluated adherence to orders in the other treatment areas.

Community settings: Patients with POLST more likely to die out of hospital

The largest study of POLST use in community settings evaluated deaths in Oregon over one year.1 It found that patients who indicated “do not attempt CPR” on a POLST form were 6 times more likely to die a natural, out-of-hospital death than those who had no POLST form (TABLE1-10).

A West Virginia study found that patients with POLST forms had 30% higher out-of-hospital death rates than those with traditional advanced directives and no POLST.2 In a Wisconsin study, no decedents who indicated DNR on their POLST forms received CPR.3

One study that evaluated the consistency of actual medical interventions with POLST orders in all 4 treatment areas found it to be good in most areas (“feeding tubes,” “attempting CPR.” “antibiotics,” and “IV fluids”) except “additional written orders.4

Skilled nursing facilities: Generally high adherence to POLST orders

The largest study to evaluate the consistency of treatments with POLST orders among nursing home residents found high adherence overall (94%).5 Caregivers performed CPR on none of 299 residents who selected “DNR.” However, they did not administer CPR to 6 of 7 who chose “attempt CPR” and administered antibiotics to 32% of patients who specified “no antibiotics” on their POLST forms.5

A second study of nursing home residents who selected “comfort measures only” also found high consistency for attempting CPR, intensive care admission, and ventilator support, although physicians hospitalized 2% of patients to extend life.6 Similarly, treatments matched POLST orders well overall in a Washington state study, although one patient got a feeding tube against orders.7

POLST adherence is good, but can EMS workers find the form?

A study comparing emergency medical services (EMS) management with POLST orders in an Oregon registry found good consistency.8 EMS providers didn’t attempt or halted CPR in most patients with DNR orders who were found in cardiac arrest and initiated CPR in most patients who chose “attempt CPR.” EMS providers initiated CPR in the field on 11 patients (22%) with a DNR order but discontinued resuscitation en route to the hospital.

In a smaller study, EMS providers never located paper POLST forms at the scene in most cases.9

Hospice: POLST orders prevent unwanted Tx, except maybe antibiotics

A study evaluating management in hospice programs in 3 states found that care providers followed POLST orders for limited treatment in 98% of cases.10 No patients received unwanted CPR, intubation, or feeding tubes. POLST orders didn’t predict whether patients were treated with antibiotics, however.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The POLST form offers choices within 4 treatment areas: “attempt CPR” or “allow natural death” if the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest; “comfort,” “limited,” or “full” medical interventions if pulse or breathing is present; choices of additional orders, including intravenous fluids, feeding tubes, and antibiotics; and additional written orders. Most POLST studies used cross-sectional and retrospective cohort designs and assessed whether CPR was attempted. Fewer studies also evaluated adherence to orders in the other treatment areas.

Community settings: Patients with POLST more likely to die out of hospital

The largest study of POLST use in community settings evaluated deaths in Oregon over one year.1 It found that patients who indicated “do not attempt CPR” on a POLST form were 6 times more likely to die a natural, out-of-hospital death than those who had no POLST form (TABLE1-10).

A West Virginia study found that patients with POLST forms had 30% higher out-of-hospital death rates than those with traditional advanced directives and no POLST.2 In a Wisconsin study, no decedents who indicated DNR on their POLST forms received CPR.3

One study that evaluated the consistency of actual medical interventions with POLST orders in all 4 treatment areas found it to be good in most areas (“feeding tubes,” “attempting CPR.” “antibiotics,” and “IV fluids”) except “additional written orders.4

Skilled nursing facilities: Generally high adherence to POLST orders

The largest study to evaluate the consistency of treatments with POLST orders among nursing home residents found high adherence overall (94%).5 Caregivers performed CPR on none of 299 residents who selected “DNR.” However, they did not administer CPR to 6 of 7 who chose “attempt CPR” and administered antibiotics to 32% of patients who specified “no antibiotics” on their POLST forms.5

A second study of nursing home residents who selected “comfort measures only” also found high consistency for attempting CPR, intensive care admission, and ventilator support, although physicians hospitalized 2% of patients to extend life.6 Similarly, treatments matched POLST orders well overall in a Washington state study, although one patient got a feeding tube against orders.7

POLST adherence is good, but can EMS workers find the form?

A study comparing emergency medical services (EMS) management with POLST orders in an Oregon registry found good consistency.8 EMS providers didn’t attempt or halted CPR in most patients with DNR orders who were found in cardiac arrest and initiated CPR in most patients who chose “attempt CPR.” EMS providers initiated CPR in the field on 11 patients (22%) with a DNR order but discontinued resuscitation en route to the hospital.

In a smaller study, EMS providers never located paper POLST forms at the scene in most cases.9

Hospice: POLST orders prevent unwanted Tx, except maybe antibiotics

A study evaluating management in hospice programs in 3 states found that care providers followed POLST orders for limited treatment in 98% of cases.10 No patients received unwanted CPR, intubation, or feeding tubes. POLST orders didn’t predict whether patients were treated with antibiotics, however.

1. Fromme EK, Zive D, Schmidt TA, et al. Association between physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for scope of treatment and in-hospital death in Oregon. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1246-1251.

2. Pedraza SL, Culp S, Falkenstine EC, et al. POST forms more than advance directives associated with out-of-hospital death: insights from a state registry. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016; 51:240-246.

3. Hammes B, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD, et al. The POLST program: a retrospective review of the demographics of use and outcomes in one community where advance directives are prevalent. J Palliative Med. 2012;15:77-85.

4. Lee MA, Brummel-Smith K, Meyer J, et al. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): outcomes in a PACE program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1219-1225.

5. Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2091-2099.

6. Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Nelson CA, et al. A prospective study of the efficacy of the physician order form for life sustaining treatment. J Am Ger Soc.1998;46:1097-1102.

7. Meyers J, Moore C, McGrory A, et al. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form: honoring end-of-life directives for nursing home residents. J Geron Nursing. 2004;30:37-46.

8. Richardson DK, Fromme E, Zive D, et al. Concordance of out-of-hospital and emergency department cardiac arrest resuscitation with documented end-of-life choices in Oregon. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:375-383.

9. Schmidt T, Olszewski EA, Zive D, et al. The Oregon physician orders for life-sustaining treatment registry: a preliminary study of emergency medical services utilization. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:796-805.

10. Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. Use of the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice setting. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:133-141.

1. Fromme EK, Zive D, Schmidt TA, et al. Association between physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for scope of treatment and in-hospital death in Oregon. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1246-1251.

2. Pedraza SL, Culp S, Falkenstine EC, et al. POST forms more than advance directives associated with out-of-hospital death: insights from a state registry. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016; 51:240-246.

3. Hammes B, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD, et al. The POLST program: a retrospective review of the demographics of use and outcomes in one community where advance directives are prevalent. J Palliative Med. 2012;15:77-85.

4. Lee MA, Brummel-Smith K, Meyer J, et al. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): outcomes in a PACE program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1219-1225.

5. Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2091-2099.

6. Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Nelson CA, et al. A prospective study of the efficacy of the physician order form for life sustaining treatment. J Am Ger Soc.1998;46:1097-1102.

7. Meyers J, Moore C, McGrory A, et al. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form: honoring end-of-life directives for nursing home residents. J Geron Nursing. 2004;30:37-46.

8. Richardson DK, Fromme E, Zive D, et al. Concordance of out-of-hospital and emergency department cardiac arrest resuscitation with documented end-of-life choices in Oregon. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:375-383.

9. Schmidt T, Olszewski EA, Zive D, et al. The Oregon physician orders for life-sustaining treatment registry: a preliminary study of emergency medical services utilization. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:796-805.

10. Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. Use of the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice setting. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:133-141.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Quite well, for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Most patients (91%-100%) who select “do not resuscitate” (DNR) on their physician’s orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) forms are allowed a natural death without attempted CPR across a variety of settings (community, skilled nursing facilities, emergency medical services, and hospice). Few patients (6%) who select “comfort measures only” die in the hospital, whereas more (22%) who choose “limited interventions,” and still more (34%) without a POLST form, die in the hospital (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, large, consistent cross-sectional and cohort studies).

Most patients (84%) who select “attempt resuscitation” receive resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in emergency services settings (SOR: B, small retrospective cohort study).

POLST orders declining other services (intravenous fluids, intensive care, intubation, feeding tubes) are carried out in most (84%-100%) cases. POLST orders regarding antibiotic treatments are less effectively implemented (SOR: B, moderate-sized retrospective chart review).

Distress Screening and Management in an Outpatient VA Cancer Clinic: A Pilot Project Involving Ambulatory Patients Across the Disease Trajectory (FULL)

A diagnosis of cancer, its treatment, and surveillance are fraught with distress. Distress is defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) as “a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment.”1 Distress is known to occur at any point along the cancer-disease trajectory: during diagnosis, during treatment, at the end of treatment, at pivotal treatment decision points, from survivorship through to end of life.2 The severity of the distress can range from “common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears to problems that can become disabling, such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation, and existential and spiritual crisis.”1 Most important, the impact of distress has been associated with reduced quality of life (QOL) and potentially reduced survival.3,4

About 33% of all persons with cancer experience severe distress.5,6 As a result of the prevalence and severity of distress, the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Distress Management recommend that all patients with cancer should be screened for distress, using a standardized tool, at their initial visit, at appropriate intervals, and as clinically indicated.1 The time line for longitudinal screening of “appropriate intervals” has not been firmly established.2 However, it is well recognized that appropriate intervals include times of vulnerability such as remission, recurrence, termination of treatment, and progression.1,7 Despite efforts to improve distress screening and intervention, many institutions struggle to adhere to the NCCN Guidelines®.8,9

In 2012, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (ACoS CoC) identified distress screening as an essential accreditation standard by 2015.10 The standard mandates that patients be screened a minimum of 1 time at a “pivotal” medical visit (such as time of diagnosis, transitions in cancer treatment, recurrence, completion of cancer treatment, and progression of disease). In practice, most institutions typically screen at diagnosis.2 According to the ACoS CoC, 41 VAMCs are accredited sites that will be impacted by the implementation of this standard.10

Distress Screening Tools

A major challenge and barrier to integrating distress screening in cancer clinics is the lack of consensus on the best measurement tool in a busy ambulatory clinic. Although a number of screening tools are available for measuring cancer-related distress, they vary in efficacy and feasibility. According to Zabora and Macmurray, the perfect screening instrument for distress in persons with cancer does not exist.6 Brief screening tools demonstrate high sensitivity in identifying very distressed patients but lack specificity, resulting in false positives.8,11 More extensive screening instruments, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)-18, and the Psycho-Oncology Screening Tool (POST), have lower rates of false positives but may be more burdensome for providers, especially when considering copyright and cost.6

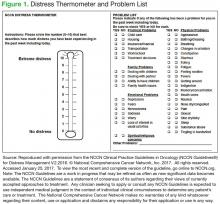

Ambulatory cancer care requires a rapid screening method with high sensitivity and minimal burden.12 The NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT) has face validity and allows for rapid screening; however, its psychometric properties are not as robust as other instru ments, such as the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Psychological Distress Inventory, or Brief Symptom Inventory.13 Although the DT has been shown to identify clinically significant anxiety, it is not as sensitive in identifying depression.4

The NCCN DT has 2 parts to the screening: (1) an overall distressintensity score within the past week, including the current day; and (2) an accompanying problem list, grouped into 5 categories, addressing QOL domains.14 The quantitative score ranges from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress). The problem list complements the quantitative score by providing information about the source of distress and can help to tailor the intervention (Figure 1). Access to the NCCN Guideline and DT is free for clinical and personal use.

According to the NCCN Guideline, scores of ≥ 4 require distress-management intervention.1 Mild distress (score < 4) usually can be managed by the primary oncology team.15 However, if the patient’s score is moderate (4-7) or severe (8-10), urgent intervention is necessary. Depending on the source of the distress, the patient should be seen by the appropriate discipline. For patients with practical problems, such as transportation, finances, and housing issues, a referral to social work is needed. For those with distress related to mental health issues, psychology, psychiatry, or social work may be appropriate.

Patients with distressing physical symptoms should be seen by the physician or advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) from the oncology or palliative care team. With limited psychosocial resources available at many cancer clinics, identification and triage for those with the highest levels of distress are critical.5 Triage must incorporate both the total distress score and the components of the distress so that the appropriate disciplines are accessed for the plan of care. More than one discipline may be needed to address multifactorial distress.

Despite strong recommendations from NCCN, ACoS, and many other professional and accrediting agencies, numerous cancer programs face challenges implementing routine screening. This article reports on a large, inner city ambulatory clinic’s pilot project to distress screen all patients at every appointment in the Cancer Center of Excellence (CoE) at Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC (LSCVAMC) between May 2012 and May 2014 and to provide immediate intervention from the appropriate discipline for patients scoring ≥ 4 on a 0 to 10 DT scale. Results of the screenings, feasibility of screening in an ambulatory VA cancer clinic, and impact on psychosocial resources are presented.

Center of Excellence Project

The LSCVAMC CoE Cancer Care Clinic began as a 3-year grant-funded project from the VA Offices of Specialty Care and Academic Affiliations with 2 major objectives: (1) to deliver quality patient-centered cancer care as measured by implementation of a process for distress screening and management, and development and implementation of a survivorship care plan for patients who have completed cancer treatment; and (2) to provide interprofessional education for the interdisciplinary health care professionals who participate in the clinic as part of their training experience.

Patients in this unique CoE cancer clinic have sameday access to all members of the interdisciplinary and interprofessional team. The ambulatory cancer care CoE team was originally composed of a surgical oncologist, a medical oncologist, a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) patient navigator, a nurse practitioner (NP) in survivorship care, a registered nurse (RN), a psychologist, and an oncology social worker. The project’s patient population included patients with a cancer concern (positive family history and suspicious scans) or a diagnosis of breast cancer, melanoma, sarcoma, or hematologic malignancies. The patient population for the project was based on the CoE team expertise and feasibility of implementation, with plans to roll out the model of care for all patients with any cancer diagnosis across the VAMC at the completion of the project.

The CoE made distress screening and management the leading priority for quality patient-centered care at the start of the project. The purpose of this emphasis on distress screening was to develop a process at LSCVAMC that would meet the 2015 CoC standards and to teach health care professional trainees (NP students, residents, social work students, and fellows in psychology and medical oncology) about distress screening and intervention.

A plan-do-act model of quality improvement (QI) was used to support the development and implementation of the distress-screening process. At the beginning of the project, the institutional review board (IRB) reviewed the protocol and determined that informed consent was not necessary because a QI project for a new standard of care did not require IRB approval. The CoE team met for about 4 months to develop a policy and procedure for the process, based on evidence from national guidelines, a review of the literature, and a discussion of the benefits and burdens of implementation within the current practice.

Limiting initial implementation to a single clinic day made the process more manageable. Descriptive methods analyzed the incidence and percentage of overall distress in this veteran population and quantified the incidences and percentages of each DT component. Feedback from patients and staff offered information on the feasibility of and satisfaction with the process.

From May 2012 to May 2014, all patients who attended the Monday outpatient CoE clinic with a diagnosis of cancer or a cancer concern were given the NCCN, 2.2013 DT instrument by the registration desk clerk at the time they registered for their clinic appointment. 16 Veterans who had difficulty filling out the DT or who had diminished capacity were assisted in completing the instrument by a designated family member and/or the clinic RN.

The completed instrument was evaluated by the CNS patient navigator, and any patient with a score ≥ 4 received an automatic referral to the behavioral health psychologist, social worker, NP, or all team members and their trainees, depending on the areas of distress (eg, practical, family, and emotional problems, spiritual/religious concerns, and/or physical problems) endorsed by the patient.

A psychiatrist was not embedded into the team but worked closely with the team’s oncology psychologist. The psychologist communicated directly with the psychiatrist, and the plan was shared with the team through the electronic medical record (EMR). The appropriate team member(s) and trainee(s) saw the patient at the visit to address needs in real time. Access to palliative care support and spiritual care was readily available if needed.

Distress screenings were recorded in a templated note in the patient’s EMR, which allowed the team to follow the distress scores on an individual basis across the cancer disease trajectory and to assess response to interventions. Multiple screenings of individuals resulted from the fact that many of the patients were seen monthly or every 3/6/9 months, depending on their disease and treatment status. Because levels of distress can fluctuate, distress was assessed at every visit to determine whether an intervention was needed at that visit. Once distress screenings were recorded in the patient’s EMR, the DT instrument was de-identified and given to the CoE research consultant to enter into a database file for analysis.

Trainees were educated about the use of the DT at time of diagnosis and across the disease trajectory. The 4-week CoE curriculum included 2 weeks of conference time to teach about the roles of psychologist, oncology social worker, and survivorship NP in assessing and initiating interventions to address the multidimensional components of the DT. Trainees working with a veteran who was distressed participated in the assessment(s) and intervention(s) for all components of distress that were endorsed.

Results

A total of 866 distress screenings were performed during the first 2 years of the project. Since all patients were screened at all visits, the 866 distress screenings reflect multiple screenings for 445 unique patients. Of the 866 screenings, 290 (33%) had distress scores of ≥ 4, meeting the criteria for intervention. Screenings reflected patient visits at any point in the disease trajectory. Because this was a new standard of care QI project rather than a research project, additional data, such as diagnosis or staging, were not collected, and IRB approval was not needed.

Because the NCCN Guideline recommendation for intervention is a score of ≥ 4, the descriptive statistics focused on those with moderate-to-severe distress. However, there were numerous occasions when the veteran would report a score of 0 to 3 and still endorse a number of the problems on the DT. The CNS and RN on the team discussed these findings with the appropriate discipline. For example, if the veteran reported a score of 1 but endorsed all 6 components on the emotional problem list, the nurses discussed the patient with the social worker or psychologist to determine whether behavioral health intervention was needed.

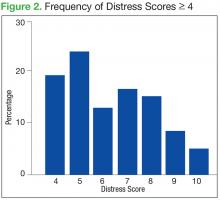

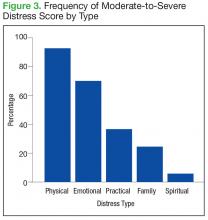

The mean distress score for the 290 screenings ≥ 4 was 6.3 on a 0 to 10 scale; median was 6.0 and mode 5.0. Two hundred ten of these screenings (72%) were categorized as moderate distress (4-7), and 80 patients (28%) reported severe distress (Figure 2). If the veteran left a box empty on the problem list, itwas recorded as missing. The frequency that patients reported each type of distress are reported in Figure 3.

The incidence of each component of distress, from those screenings with a score of ≥ 4 is described below, along with case study examples for each component. Team members involved in patient interventions provided these case studies to demonstrate clinical examples of the veteran’s distress from the problem list on the DT.

Practical/Family Distress

Practical issues were reported in 38% of the screenings (109/290). Intervention for moderate-to-severe distress associated with practical problems and family issues was provided by the team social worker. The social worker frequently addressed transportationrelated distress. Providing transportation was essential for adherence to clinic appointments, follow-up testing, treatments, and ultimately, disease management. Housing was also a problem for many veterans. It is critical that patients have access to electricity, heating, food, and water to be able to safely undergo adjuvant therapy. Thus, treatments decisions could be impacted by the veterans’ housing and transportation issues; immediate access to social work support is essential for quality cancer care.

Twenty-six percent of patients that were screened expressed concerns with practical and/or family problems (75/289). Issues of domestic violence, difficulties dealing with a significant other, and concerns about children were referred to social work (Table 1).

Case Study

Ms. S. is a veteran aged 71 years with recently diagnosed breast cancer. She is being seen in the clinic for a postoperative visit following partial mastectomy and is anticipating beginning radiation therapy within the next 3 weeks. She reports a distress score of 7 and identifies concerns about work and transportation to the clinic as the sources of distress. The social worker meets with the patient and learns that she fears losing her job because of the daily travel time to and from radiation and that she cannot afford to travel 65 miles daily to LSCVAMC for radiation. The social worker listens to her concerns and assists her with a plan for short-term disability and VA housing during her radiation therapy treatments. Ms. S. was able to complete radiation at LSCVAMC with temporary housing and to return to work after therapy.

Emotional Distress

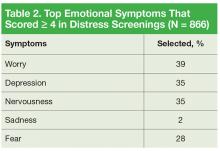

Patients who identified that their moderate-to-severe distress was related to emotional problems received same-day intervention from a psychologist skilled in providing emotional support, cognitive behavioral strategies, and assessing the need for referral to either a psychiatrist or oncology social worker. Seventy-one percent of patients reported emotional problems, such as worry, depression, and nervousness (Table 2).

Case Study

Mr. K. is a veteran aged 71 years with a new diagnosis of breast cancer. He lives on his own but has family and a few friends nearby. He reports that he doesn’t like to share his problems with others and has not told anyone of his new diagnosis. Mr. K. rates his distress a 7 and endorses worry, fear, and depression. At a treatment-planning visit, he agrees to see the psychologist for help in dealing with his distress. Treatment involves a mastectomy followed by hormonal therapy.

Mr. K. was scared about having cancer; some of his veteran colleagues have developed cancer recently, and 2 have died. He told the psychologist that he feels worthless and that this disease just makes him more of a burden on society. He has had thoughts of taking his life so that he doesn’t have to deal with cancer, but he does not have a plan. The team formulated a plan to address his anxiety and depression. Mr. K. started a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and he met with the VA psychiatrist weekly to help develop coping strategies. The team’s psychologist worked closely with Mr. K.’s psychiatrist, and he successfully completed surgery and chemotherapy. He is now being seen in survivorship clinic, continuing care with the team and his psychologist.

Spiritual Distress

Although spiritual/religious concerns are part of DT screening, it is only a single item on the DT. Just 8% of patients (21/276) reported moderate-to-severe spiritual distress. However, there was access to a chaplain at LSCVAMC.

Case Study

Mr. H., a 63-year-old veteran with stage IV melanoma, was seen in the clinic for severe pain in his left hip and ribs (8 on a 10-point scale); he was unresponsive to escalating doses of oxycodone. During the visit, he reported that his distress level is a 10, and in addition to identifying pain as a source of distress, he indicated that he has spiritual distress. When questioned further about spiritual distress, Mr. H. reported that he deserves this pain since he caused so many others pain during his time in Vietnam. The chaplain was contacted, and the patient was seen in clinic at this visit. The chaplain gave him the opportunity to share his feelings of guilt. The importance of spiritual care when the patient is experiencing “total pain” is essential to pain management. Within 3 days, his pain score decreased to an acceptable level of 3 with no additional pharmacologic intervention.

Physical Distress

Physical problems associated with the distress scores were addressed by the surgical and medical oncologists and the APRNs (CNS patient navigator and survivorship NP). When the clinic opened, the team used the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale to assess physical and psychological symptoms.16 However, patients reported experiencing distress at having to complete 2 tools that had a great deal of overlap. The team determined that the DT could be used as the sole screening tool for all QOL domains.

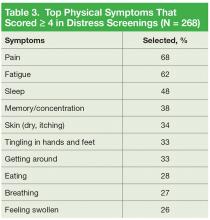

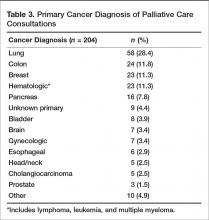

It is important to note that 92% of patients with moderate-to-severe distress reported physical symptoms as a source of distress (Table 3).

Case Study

Ms. L. is a Vietnam War veteran aged 64 years who was seen in the survivorship clinic. She was diagnosed with estrogen-receptor (ER) and progesterone-receptor (PR) breast cancer 1 year previously, had a lumpectomy followed by radiation therapy, and was on hormonal therapy. She recorded her distress score as a 6 and indicated that multiple physical symptoms were her major concern. She had difficulty with insomnia, fatigue, and hot flashes. The survivorship NP talked with Ms. L. about her symptoms and made nonpharmacologic recommendations for improving sleep, provided an exercise plan for fatigue, and initiated venlafaxine to manage the hot flashes. Ms. L. continued to be seen by the team in survivorship clinic, and during her 3-month follow-up visit, she reported improvement in sleep as the hot flashes diminished.

Multifactoral Distress

Many patients endorsed ≥ 1 component of distress. This required a team approach to intervene for the multifactorial nature of the distress.

Case Study

Mr. K. is a veteran aged 82 years who had been a farmer most of his life. He was cared for at the VA for an advancedstage squamous cell skin cancer of his scalp, which he had allowed to go untreated. The cancer has completely eroded beneath his scalp, and he wore a hat to cover the foul-smelling wound. He lived in rural Ohio with his wife of 55 years; 3 adult daughters lived in the Cleveland area. His daughters served as primary caregivers when Mr. K. came to Cleveland for daily radiation and weekly chemotherapy treatments. He had not been away from his wife since the war and misses her terribly, returning home only on weekends during the 6-week course of radiation.

His primary goal was to return home in time to harvest his farm’s produce 2 months later. He was aware that he has < 6 months to live but wanted chemotherapy and radiation to control the growth of the cancer. During this visit to the ambulatory clinic, he reported a distress score of 5 andidentified family concerns (eg, living away from his wife most of every week) and endorsed emotional concerns of fear, worry, and sadness, and reported pain, fatigue, insomnia, and constipation as physical concerns.

Mr. K. received support from the social worker, the psychologist, and the APRN for symptom management during this visit. The social worker was able to advocate for limited palliative radiation therapy treatments rather than a 6-week course; the psychologist spent 45 minutes talking with him about his fears of a painful death, worries about his wife, and sadness at not being alive for another planting season. The APRN recommended both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions for his fatigue and insomnia and initiated a pain and bowel pharmacologic regimen. The team respected Mr. K.’s wish to reconsider hospice care at the following visit after he had talked with his wife. Mr. K. died peacefully in his home with his wife and family just before the start of planting season.

Clinical Implications

Distress screening and intervention is essential for quality cancer care. While a great deal of controversy exists about the best time to screen for distress, the LSCVAMC CoE has taken on the challenge of screening and intervening in real time at every patient visit across the disease trajectory. The model of distress screening all veterans at CoE clinic visits has been rolled out to other cancer clinics at LSCVAMC.

Distress screening at each visit is not time intensive. Patients are willing to fill out the instrument while waiting for their clinic visit, and most patients find that it takes less than 5 minutes to complete. The major challenge for institutions considering screening with each visit is not the screening but access to appropriate providers able to provide timely intervention. The success of this model results, in part, because the clinic RN assesses the responses to the DT and refers to the appropriate discipline, utilizing precious resources of social work and psychology appropriately. The VA system is already committed to improving the psychosocial well-being of veterans and has established social work and psychology resources specifically for the cancer clinics.

Many patients reported to the authors that they might not have been able or willing to return to LSCVAMC to see the behavioral health specialists on another day. In addition, scheduling behavioral health appointments at another time would not allow for attending to the distress in real time. Also, from a systems standpoint, it would have been an added cost to the VA and/or the veteran for transportation for additional appointments on different days.

Finally, although the impact of the CoE project on health professional trainees has been reported elsewhere, the distress screening and intervention process were valued as being very positive for all trainees who participated in CoE clinic.17 The trainees were able to stay with the patient for the entire clinic visit, including the visits made by disciplines other than their own. For example, the family medicine residents stayed with the patient they examined to observe the distress assessments and interventions offered by the social worker and/or psychologist for the patients who scored ≥ 4 on the DT.

At the end of their rotations in the CoE, trainees reported an increased awareness of the importance of distress screening in a cancer clinic. Many were not aware of the NCCN guidelines and the ACoS CoC mandate for distress screening as a standard of cancer care. Interdisciplinary trainees rated the CoE curriculum and the conference teaching/learning sessions on distress management highly. However, observing the role of the social worker and psychologist were the most valuable to trainees, regardless of the area of practice they enter.

Conclusion

Addressing practical, psychosocial, physical, and spiritual needs will help decrease distress, support patients’ ability to tolerate treatment, and improve veterans’ QOL across the cancer-disease trajectory. Screening all patients at an outpatient cancer clinic at LSCVAMC is feasible and does not seem to be a burden for patients or providers. This pilot project has become standard of care across the LSCVAMC cancer clinics, demonstrating its sustainability.

Screening with the DT provides information about the intensity of the distress and the components contributing to the distress. The most important aspect of the screening is assessing the components of the distress and providing real-time intervention from the appropriate discipline. It is critical that the oncology team refer to the appropriate discipline based on the source of the distress rather than on only the intensity. Findings from this project indicate that physical symptoms are frequently the source of distress and may not require behavioral health intervention. However, for patients with psychosocial needs, rapid access to behavioral health care services is critical for quality veteran-centered cancer care.

Since 2015, all VA cancer centers are required to have implemented distress screening. According to the CoC, at least 1 screening must be done on every patient.10 Many institutions have begun to screen at diagnosis, but it is well known that there are many points along the cancer trajectory when patients may experience an increase in distress. Simple screening with the DT at every cancer clinic visit helps identify the veterans’ needs at any point along the disease spectrum.

At LSCVAMC, the CoE was designed as an interdisciplinary cancer clinic. With the conclusion of funding in FY 2015, the clinic has continued to function. The rollout into other clinics has continued with movement toward use of formal consult requests and continual, real-time evaluation of the process. Work on accurate, timely identification of new cancer patients and identifying pivotal cancer visits is underway. The LSCVAMC is committed to improving care and access to its veterans with cancer to ensure appropriate and adequate services across the cancer trajectory.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Holand JC, Jacobsen PB, Anderson A, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Distress Management 2.2016. © 2014 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf. Updated July 25, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2017.

2. Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1160-1177.

3. Hamer M, Chida Y, Molloy G. Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(3):255-258.

4. Mitchell AJ. Short screening tools for cancer-related distress: a review and diagnostic validity meta-analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;8(4):487-494.

5. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19-28.

6. Zabora JR, Macmurray L. The history of psychosocial screening among cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(6):625-635.

7. Pirl WF, Fann JR, Greer JA, et al. Recommendations for the implementation of distress screening programs in cancer centers: report from the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (APOS), Association of Oncology Social Work (AOSW), and Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) joint task force. Cancer. 2014;120(91):2946-2954.

8. Parry C, Padgett LS, Zebrack B. Now what? Toward an integrated research and practice agenda in distress screening. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(6):715-727.

9. Wagner LI, Spiegel D, Pearman T. Using the science of psychosocial care to implement the new American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer distress screening standard. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(2):214-221.

10. American College of Surgeons Commision on Cancer. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc Published 1996. Updated January 19, 2017. Accessed April 16, 2016.

11. Rohan EA. Removing the stress from selecting instruments: arming social workers to take leadership in routine distress screening implementation. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(6):667-678.

12. Merport A, Bober SL, Grose A, Recklitis CJ. Can the distress thermometer (DT) identify significant psychological distress in long-term cancer survivors? A comparison with the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18). Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):195-198.

13. Carlson LE, Bultz BD. Cancer distress screening: Needs, models, and methods. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(5):403-409.

14. Holland JC, Alici Y. Management of distress in cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2010:8(1):4-12.

15. Jacobsen P, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494-1502.

16. Portenoy R, Thaler HT, Korblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(9):1326-1336.

17. Arfons L, Mazanec P, Smith J, et al. Training health care professionals in interprofessional collaborative cancer care. Health Interprof Pract. 2015;2(3):eP1073.

A diagnosis of cancer, its treatment, and surveillance are fraught with distress. Distress is defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) as “a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment.”1 Distress is known to occur at any point along the cancer-disease trajectory: during diagnosis, during treatment, at the end of treatment, at pivotal treatment decision points, from survivorship through to end of life.2 The severity of the distress can range from “common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears to problems that can become disabling, such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation, and existential and spiritual crisis.”1 Most important, the impact of distress has been associated with reduced quality of life (QOL) and potentially reduced survival.3,4

About 33% of all persons with cancer experience severe distress.5,6 As a result of the prevalence and severity of distress, the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Distress Management recommend that all patients with cancer should be screened for distress, using a standardized tool, at their initial visit, at appropriate intervals, and as clinically indicated.1 The time line for longitudinal screening of “appropriate intervals” has not been firmly established.2 However, it is well recognized that appropriate intervals include times of vulnerability such as remission, recurrence, termination of treatment, and progression.1,7 Despite efforts to improve distress screening and intervention, many institutions struggle to adhere to the NCCN Guidelines®.8,9

In 2012, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (ACoS CoC) identified distress screening as an essential accreditation standard by 2015.10 The standard mandates that patients be screened a minimum of 1 time at a “pivotal” medical visit (such as time of diagnosis, transitions in cancer treatment, recurrence, completion of cancer treatment, and progression of disease). In practice, most institutions typically screen at diagnosis.2 According to the ACoS CoC, 41 VAMCs are accredited sites that will be impacted by the implementation of this standard.10

Distress Screening Tools

A major challenge and barrier to integrating distress screening in cancer clinics is the lack of consensus on the best measurement tool in a busy ambulatory clinic. Although a number of screening tools are available for measuring cancer-related distress, they vary in efficacy and feasibility. According to Zabora and Macmurray, the perfect screening instrument for distress in persons with cancer does not exist.6 Brief screening tools demonstrate high sensitivity in identifying very distressed patients but lack specificity, resulting in false positives.8,11 More extensive screening instruments, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)-18, and the Psycho-Oncology Screening Tool (POST), have lower rates of false positives but may be more burdensome for providers, especially when considering copyright and cost.6

Ambulatory cancer care requires a rapid screening method with high sensitivity and minimal burden.12 The NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT) has face validity and allows for rapid screening; however, its psychometric properties are not as robust as other instru ments, such as the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Psychological Distress Inventory, or Brief Symptom Inventory.13 Although the DT has been shown to identify clinically significant anxiety, it is not as sensitive in identifying depression.4

The NCCN DT has 2 parts to the screening: (1) an overall distressintensity score within the past week, including the current day; and (2) an accompanying problem list, grouped into 5 categories, addressing QOL domains.14 The quantitative score ranges from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress). The problem list complements the quantitative score by providing information about the source of distress and can help to tailor the intervention (Figure 1). Access to the NCCN Guideline and DT is free for clinical and personal use.

According to the NCCN Guideline, scores of ≥ 4 require distress-management intervention.1 Mild distress (score < 4) usually can be managed by the primary oncology team.15 However, if the patient’s score is moderate (4-7) or severe (8-10), urgent intervention is necessary. Depending on the source of the distress, the patient should be seen by the appropriate discipline. For patients with practical problems, such as transportation, finances, and housing issues, a referral to social work is needed. For those with distress related to mental health issues, psychology, psychiatry, or social work may be appropriate.

Patients with distressing physical symptoms should be seen by the physician or advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) from the oncology or palliative care team. With limited psychosocial resources available at many cancer clinics, identification and triage for those with the highest levels of distress are critical.5 Triage must incorporate both the total distress score and the components of the distress so that the appropriate disciplines are accessed for the plan of care. More than one discipline may be needed to address multifactorial distress.

Despite strong recommendations from NCCN, ACoS, and many other professional and accrediting agencies, numerous cancer programs face challenges implementing routine screening. This article reports on a large, inner city ambulatory clinic’s pilot project to distress screen all patients at every appointment in the Cancer Center of Excellence (CoE) at Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC (LSCVAMC) between May 2012 and May 2014 and to provide immediate intervention from the appropriate discipline for patients scoring ≥ 4 on a 0 to 10 DT scale. Results of the screenings, feasibility of screening in an ambulatory VA cancer clinic, and impact on psychosocial resources are presented.

Center of Excellence Project

The LSCVAMC CoE Cancer Care Clinic began as a 3-year grant-funded project from the VA Offices of Specialty Care and Academic Affiliations with 2 major objectives: (1) to deliver quality patient-centered cancer care as measured by implementation of a process for distress screening and management, and development and implementation of a survivorship care plan for patients who have completed cancer treatment; and (2) to provide interprofessional education for the interdisciplinary health care professionals who participate in the clinic as part of their training experience.

Patients in this unique CoE cancer clinic have sameday access to all members of the interdisciplinary and interprofessional team. The ambulatory cancer care CoE team was originally composed of a surgical oncologist, a medical oncologist, a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) patient navigator, a nurse practitioner (NP) in survivorship care, a registered nurse (RN), a psychologist, and an oncology social worker. The project’s patient population included patients with a cancer concern (positive family history and suspicious scans) or a diagnosis of breast cancer, melanoma, sarcoma, or hematologic malignancies. The patient population for the project was based on the CoE team expertise and feasibility of implementation, with plans to roll out the model of care for all patients with any cancer diagnosis across the VAMC at the completion of the project.

The CoE made distress screening and management the leading priority for quality patient-centered care at the start of the project. The purpose of this emphasis on distress screening was to develop a process at LSCVAMC that would meet the 2015 CoC standards and to teach health care professional trainees (NP students, residents, social work students, and fellows in psychology and medical oncology) about distress screening and intervention.

A plan-do-act model of quality improvement (QI) was used to support the development and implementation of the distress-screening process. At the beginning of the project, the institutional review board (IRB) reviewed the protocol and determined that informed consent was not necessary because a QI project for a new standard of care did not require IRB approval. The CoE team met for about 4 months to develop a policy and procedure for the process, based on evidence from national guidelines, a review of the literature, and a discussion of the benefits and burdens of implementation within the current practice.

Limiting initial implementation to a single clinic day made the process more manageable. Descriptive methods analyzed the incidence and percentage of overall distress in this veteran population and quantified the incidences and percentages of each DT component. Feedback from patients and staff offered information on the feasibility of and satisfaction with the process.

From May 2012 to May 2014, all patients who attended the Monday outpatient CoE clinic with a diagnosis of cancer or a cancer concern were given the NCCN, 2.2013 DT instrument by the registration desk clerk at the time they registered for their clinic appointment. 16 Veterans who had difficulty filling out the DT or who had diminished capacity were assisted in completing the instrument by a designated family member and/or the clinic RN.

The completed instrument was evaluated by the CNS patient navigator, and any patient with a score ≥ 4 received an automatic referral to the behavioral health psychologist, social worker, NP, or all team members and their trainees, depending on the areas of distress (eg, practical, family, and emotional problems, spiritual/religious concerns, and/or physical problems) endorsed by the patient.

A psychiatrist was not embedded into the team but worked closely with the team’s oncology psychologist. The psychologist communicated directly with the psychiatrist, and the plan was shared with the team through the electronic medical record (EMR). The appropriate team member(s) and trainee(s) saw the patient at the visit to address needs in real time. Access to palliative care support and spiritual care was readily available if needed.

Distress screenings were recorded in a templated note in the patient’s EMR, which allowed the team to follow the distress scores on an individual basis across the cancer disease trajectory and to assess response to interventions. Multiple screenings of individuals resulted from the fact that many of the patients were seen monthly or every 3/6/9 months, depending on their disease and treatment status. Because levels of distress can fluctuate, distress was assessed at every visit to determine whether an intervention was needed at that visit. Once distress screenings were recorded in the patient’s EMR, the DT instrument was de-identified and given to the CoE research consultant to enter into a database file for analysis.

Trainees were educated about the use of the DT at time of diagnosis and across the disease trajectory. The 4-week CoE curriculum included 2 weeks of conference time to teach about the roles of psychologist, oncology social worker, and survivorship NP in assessing and initiating interventions to address the multidimensional components of the DT. Trainees working with a veteran who was distressed participated in the assessment(s) and intervention(s) for all components of distress that were endorsed.

Results