User login

Improving Patient Safety, One Hematology/Oncology Order Set a Time. An Outpatient VA Oncology Clinic Experience

Purpose: A VISN initiative in 2015 led to development of hematology/oncology medication order sets to improve the translation of medication orders from CPRS provider order entry program to pharmacy verification program in VistA. Our purpose is to report the incidence of averted errors due to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues prior to order set initiative as compared to incidence post-order set initiative.

Background: Hematology/oncology medication orders at this outpatient VA oncology clinic are prescribed via provider order entry within CPRS. Safety concerns existed due to inefficient communication between CPRS order entry and pharmacy verification within VistA. A pharmacist verifying orders within VistA was required to re-enter critical medication order information such as drug dose into VistA. In order to find the dose ordered by a provider, the verification pharmacist

advanced at least one screen in VistA then returned to the original VistA verification screen to enter drug dose.

Methods: Incidence of averted errors related to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues between CPRS and VistA are reported for the 2-year time period (October 2013 through September 2015) prior to order set initiative and for the 2-year time period (October 2015 through September 2017) after beginning the order set initiative. Additional information includes facility resources, such as: treatment area, providers, staffing, oncology pharmacy, pharmacy ADPAC, and CACs; mechanisms of orders and notes entering/recording; dosing and safety checks;

and available order sets.

Results: The incidence rate of averted errors related to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues prior to order set initiative was 0.379% as compared to 0.128% rate of averted errors in the two years post order set initiative. Results showed hematology/oncology medication order sets used at this facility positively impacted the incidence of averted errors attributed to translation issues from CPRS to VistA. With fewer averted errors, patient safety increased.

Implications: Using limited VA resources, order sets were implemented for use at this VA outpatient oncology clinic. The hematology/oncology health care team worked together to provide vigilant oversight of order sets and to incorporate necessary revisions, updates, and additions. With fewer averted errors, the effectiveness of this initiative is quantified with improved patient care, safety and efficiency.

Purpose: A VISN initiative in 2015 led to development of hematology/oncology medication order sets to improve the translation of medication orders from CPRS provider order entry program to pharmacy verification program in VistA. Our purpose is to report the incidence of averted errors due to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues prior to order set initiative as compared to incidence post-order set initiative.

Background: Hematology/oncology medication orders at this outpatient VA oncology clinic are prescribed via provider order entry within CPRS. Safety concerns existed due to inefficient communication between CPRS order entry and pharmacy verification within VistA. A pharmacist verifying orders within VistA was required to re-enter critical medication order information such as drug dose into VistA. In order to find the dose ordered by a provider, the verification pharmacist

advanced at least one screen in VistA then returned to the original VistA verification screen to enter drug dose.

Methods: Incidence of averted errors related to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues between CPRS and VistA are reported for the 2-year time period (October 2013 through September 2015) prior to order set initiative and for the 2-year time period (October 2015 through September 2017) after beginning the order set initiative. Additional information includes facility resources, such as: treatment area, providers, staffing, oncology pharmacy, pharmacy ADPAC, and CACs; mechanisms of orders and notes entering/recording; dosing and safety checks;

and available order sets.

Results: The incidence rate of averted errors related to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues prior to order set initiative was 0.379% as compared to 0.128% rate of averted errors in the two years post order set initiative. Results showed hematology/oncology medication order sets used at this facility positively impacted the incidence of averted errors attributed to translation issues from CPRS to VistA. With fewer averted errors, patient safety increased.

Implications: Using limited VA resources, order sets were implemented for use at this VA outpatient oncology clinic. The hematology/oncology health care team worked together to provide vigilant oversight of order sets and to incorporate necessary revisions, updates, and additions. With fewer averted errors, the effectiveness of this initiative is quantified with improved patient care, safety and efficiency.

Purpose: A VISN initiative in 2015 led to development of hematology/oncology medication order sets to improve the translation of medication orders from CPRS provider order entry program to pharmacy verification program in VistA. Our purpose is to report the incidence of averted errors due to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues prior to order set initiative as compared to incidence post-order set initiative.

Background: Hematology/oncology medication orders at this outpatient VA oncology clinic are prescribed via provider order entry within CPRS. Safety concerns existed due to inefficient communication between CPRS order entry and pharmacy verification within VistA. A pharmacist verifying orders within VistA was required to re-enter critical medication order information such as drug dose into VistA. In order to find the dose ordered by a provider, the verification pharmacist

advanced at least one screen in VistA then returned to the original VistA verification screen to enter drug dose.

Methods: Incidence of averted errors related to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues between CPRS and VistA are reported for the 2-year time period (October 2013 through September 2015) prior to order set initiative and for the 2-year time period (October 2015 through September 2017) after beginning the order set initiative. Additional information includes facility resources, such as: treatment area, providers, staffing, oncology pharmacy, pharmacy ADPAC, and CACs; mechanisms of orders and notes entering/recording; dosing and safety checks;

and available order sets.

Results: The incidence rate of averted errors related to hematology/oncology medication order translation issues prior to order set initiative was 0.379% as compared to 0.128% rate of averted errors in the two years post order set initiative. Results showed hematology/oncology medication order sets used at this facility positively impacted the incidence of averted errors attributed to translation issues from CPRS to VistA. With fewer averted errors, patient safety increased.

Implications: Using limited VA resources, order sets were implemented for use at this VA outpatient oncology clinic. The hematology/oncology health care team worked together to provide vigilant oversight of order sets and to incorporate necessary revisions, updates, and additions. With fewer averted errors, the effectiveness of this initiative is quantified with improved patient care, safety and efficiency.

Oncology Nursing Professionalism: Advocating and Developing Oncology Certified Nurses

Introduction: The Commission on Cancer (COC), the New Mexico VA Health Care System (NMVAHCS) accrediting body for cancer care, mandates 25% of nurses maintain oncology nurse certification (OCN) to validate competency. However, the NMVAHCS remains deficient: threatening facility ability to maintain accreditation. Per the Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation, Albuquerque maintains 160 OCNs. However, 50% have retired and the remaining 50% are over 52. Leaving approximately 40 OCN nurses in a population of 500,000. This problem was not only a NMVAHCS problem, but a community problem: affecting quality of oncology care.

Problem: Not only is certification required for COC accredited facilities, it represents validation of expertise and skill set. Validation serves to build trust of Veterans, enables superior clinical judgment, and contributes to improved outcomes. With the Choice Program, many Veterans can leave the VAHCS. Certification serves to build necessary confidence required to keep Veterans within the VAHCS.

Methods: Barriers prohibiting certification were identified through survey of oncology nurses. Nurses reported fear related to failure, study material costs, exam fees, lack of mentors, and lack of internal leadership encouragement and support as barriers of certification. Funding was sought to provide a review course for 40 nurses, study guides, reimbursement of course and exam fees and held June 2017 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. A second review course, held during the 2017 AVAHO meeting, was conducted for another 24 nurses. The courses aimed to build confidence and decrease barriers. Both exceeded capacity.

Results: As a result of the Albuquerque course, VISN 22 and non-VA nurses attended from several states. Each received

a 30% reduction in exam fees and were eligible for exam reimbursement after passing: 50% of attendees are now OCNs.

The AVAHO course, to date, has resulted in an additional 2 OCNs, 2 certification renewals, and an additional 5 are registered for the exam. Those not taking the exam cite lack of leadership support and encouragement as the main

barrier.

Implications: Certification validates care provided and builds Veterans trust: necessary with Choice. Facilities that retain a strong foundation of OCNs, mentor staff, and maintain leadership support remain more apt to produce and sustain certified nurses. Therefore, leadership buy-in remains essential.

Introduction: The Commission on Cancer (COC), the New Mexico VA Health Care System (NMVAHCS) accrediting body for cancer care, mandates 25% of nurses maintain oncology nurse certification (OCN) to validate competency. However, the NMVAHCS remains deficient: threatening facility ability to maintain accreditation. Per the Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation, Albuquerque maintains 160 OCNs. However, 50% have retired and the remaining 50% are over 52. Leaving approximately 40 OCN nurses in a population of 500,000. This problem was not only a NMVAHCS problem, but a community problem: affecting quality of oncology care.

Problem: Not only is certification required for COC accredited facilities, it represents validation of expertise and skill set. Validation serves to build trust of Veterans, enables superior clinical judgment, and contributes to improved outcomes. With the Choice Program, many Veterans can leave the VAHCS. Certification serves to build necessary confidence required to keep Veterans within the VAHCS.

Methods: Barriers prohibiting certification were identified through survey of oncology nurses. Nurses reported fear related to failure, study material costs, exam fees, lack of mentors, and lack of internal leadership encouragement and support as barriers of certification. Funding was sought to provide a review course for 40 nurses, study guides, reimbursement of course and exam fees and held June 2017 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. A second review course, held during the 2017 AVAHO meeting, was conducted for another 24 nurses. The courses aimed to build confidence and decrease barriers. Both exceeded capacity.

Results: As a result of the Albuquerque course, VISN 22 and non-VA nurses attended from several states. Each received

a 30% reduction in exam fees and were eligible for exam reimbursement after passing: 50% of attendees are now OCNs.

The AVAHO course, to date, has resulted in an additional 2 OCNs, 2 certification renewals, and an additional 5 are registered for the exam. Those not taking the exam cite lack of leadership support and encouragement as the main

barrier.

Implications: Certification validates care provided and builds Veterans trust: necessary with Choice. Facilities that retain a strong foundation of OCNs, mentor staff, and maintain leadership support remain more apt to produce and sustain certified nurses. Therefore, leadership buy-in remains essential.

Introduction: The Commission on Cancer (COC), the New Mexico VA Health Care System (NMVAHCS) accrediting body for cancer care, mandates 25% of nurses maintain oncology nurse certification (OCN) to validate competency. However, the NMVAHCS remains deficient: threatening facility ability to maintain accreditation. Per the Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation, Albuquerque maintains 160 OCNs. However, 50% have retired and the remaining 50% are over 52. Leaving approximately 40 OCN nurses in a population of 500,000. This problem was not only a NMVAHCS problem, but a community problem: affecting quality of oncology care.

Problem: Not only is certification required for COC accredited facilities, it represents validation of expertise and skill set. Validation serves to build trust of Veterans, enables superior clinical judgment, and contributes to improved outcomes. With the Choice Program, many Veterans can leave the VAHCS. Certification serves to build necessary confidence required to keep Veterans within the VAHCS.

Methods: Barriers prohibiting certification were identified through survey of oncology nurses. Nurses reported fear related to failure, study material costs, exam fees, lack of mentors, and lack of internal leadership encouragement and support as barriers of certification. Funding was sought to provide a review course for 40 nurses, study guides, reimbursement of course and exam fees and held June 2017 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. A second review course, held during the 2017 AVAHO meeting, was conducted for another 24 nurses. The courses aimed to build confidence and decrease barriers. Both exceeded capacity.

Results: As a result of the Albuquerque course, VISN 22 and non-VA nurses attended from several states. Each received

a 30% reduction in exam fees and were eligible for exam reimbursement after passing: 50% of attendees are now OCNs.

The AVAHO course, to date, has resulted in an additional 2 OCNs, 2 certification renewals, and an additional 5 are registered for the exam. Those not taking the exam cite lack of leadership support and encouragement as the main

barrier.

Implications: Certification validates care provided and builds Veterans trust: necessary with Choice. Facilities that retain a strong foundation of OCNs, mentor staff, and maintain leadership support remain more apt to produce and sustain certified nurses. Therefore, leadership buy-in remains essential.

Use of Simulated Patients to Teach Goals of Care Conversations

Background: Understanding a patient’s expectations with treatment for their cancer is an important first step in caring for patients with cancer. Establishing goals of care allows providers to understand what their patients are willing to endure especially if they have a limited life expectancy. It provides a plan of care that is agreed upon by both the patient and provider. However, talking to patients about goals of care requires a skill set that many providers have not fully developed.

The use of simulated patients (SPs) has been shown to be an effective method to teach communication skills. However, many people feel intimidated when they are asked to work with SPs, especially if their conversations are viewed and critiqued by others. At the Pittsburgh VA we have developed a method that uses SPs to teach communication skills in a comfortable non-threatening environment for the learner. We tested this method with our Oncology providers.

Methods: Oncologists, nurses and social workers attended a meeting where they were asked to view a scenario where a patient and his family( SPs) were informed that the patient had progression of his cancer. In the first scenario the information was presented to SPs focusing on the cancer and treatment options. In the second scenario the same information was presented by an oncologist trained in palliative care focusing on the patient’s understanding of his disease and his goals of care. SPs were asked to contrast and comment on the different styles. The audience was then asked to provide comments and feedback.

Results: Twenty-two participants provided feedback. Twenty one of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that the simulation improved their knowledge and skill set and was done in a safe and comfortable learning environment.

Conclusions: Using SPs and allowing providers to contrast different styles of communicating the same set of information can be an effective and non-threatening teaching method of teaching communication skills. Longitudinal review of patient records will further help to determine the effectiveness of this method of training.

Background: Understanding a patient’s expectations with treatment for their cancer is an important first step in caring for patients with cancer. Establishing goals of care allows providers to understand what their patients are willing to endure especially if they have a limited life expectancy. It provides a plan of care that is agreed upon by both the patient and provider. However, talking to patients about goals of care requires a skill set that many providers have not fully developed.

The use of simulated patients (SPs) has been shown to be an effective method to teach communication skills. However, many people feel intimidated when they are asked to work with SPs, especially if their conversations are viewed and critiqued by others. At the Pittsburgh VA we have developed a method that uses SPs to teach communication skills in a comfortable non-threatening environment for the learner. We tested this method with our Oncology providers.

Methods: Oncologists, nurses and social workers attended a meeting where they were asked to view a scenario where a patient and his family( SPs) were informed that the patient had progression of his cancer. In the first scenario the information was presented to SPs focusing on the cancer and treatment options. In the second scenario the same information was presented by an oncologist trained in palliative care focusing on the patient’s understanding of his disease and his goals of care. SPs were asked to contrast and comment on the different styles. The audience was then asked to provide comments and feedback.

Results: Twenty-two participants provided feedback. Twenty one of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that the simulation improved their knowledge and skill set and was done in a safe and comfortable learning environment.

Conclusions: Using SPs and allowing providers to contrast different styles of communicating the same set of information can be an effective and non-threatening teaching method of teaching communication skills. Longitudinal review of patient records will further help to determine the effectiveness of this method of training.

Background: Understanding a patient’s expectations with treatment for their cancer is an important first step in caring for patients with cancer. Establishing goals of care allows providers to understand what their patients are willing to endure especially if they have a limited life expectancy. It provides a plan of care that is agreed upon by both the patient and provider. However, talking to patients about goals of care requires a skill set that many providers have not fully developed.

The use of simulated patients (SPs) has been shown to be an effective method to teach communication skills. However, many people feel intimidated when they are asked to work with SPs, especially if their conversations are viewed and critiqued by others. At the Pittsburgh VA we have developed a method that uses SPs to teach communication skills in a comfortable non-threatening environment for the learner. We tested this method with our Oncology providers.

Methods: Oncologists, nurses and social workers attended a meeting where they were asked to view a scenario where a patient and his family( SPs) were informed that the patient had progression of his cancer. In the first scenario the information was presented to SPs focusing on the cancer and treatment options. In the second scenario the same information was presented by an oncologist trained in palliative care focusing on the patient’s understanding of his disease and his goals of care. SPs were asked to contrast and comment on the different styles. The audience was then asked to provide comments and feedback.

Results: Twenty-two participants provided feedback. Twenty one of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that the simulation improved their knowledge and skill set and was done in a safe and comfortable learning environment.

Conclusions: Using SPs and allowing providers to contrast different styles of communicating the same set of information can be an effective and non-threatening teaching method of teaching communication skills. Longitudinal review of patient records will further help to determine the effectiveness of this method of training.

Model of Integrated Oncology- Palliative Care in an Outpatient Setting

Background: Early introduction of palliative care for oncology patients has demonstrated enhanced quality of life and satisfaction. We developed a model for integrating palliative care into outpatient oncology care.

Hypothesis: Optimal integration of oncology and palliative care requires palliative care clinician’s presence at initial, and many subsequent, patient encounters.

Objective: To implement and evaluate outpatient integrated oncology and palliative care.

Method: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated outpatient practice of oncology and palliative care with: Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify patients in need of palliative care; shared palliative care-oncology appointments. Initial visit: New oncology patients are seen by an oncologist and palliative care physician together. Palliative care physician introduces palliative care and initiates advance care planning. Concurrent oncology-palliative care follow-up: High-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc) are followed by oncologist and palliative care physician. Palliative care physician facilitates goals of care discussions and addresses symptom management. End-of-life care: Hospice care remains a part of oncology care. Palliative care physician and oncology team co-manage all oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

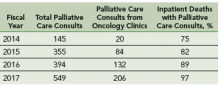

Results: Increase in palliative care consults from oncology clinics: After this intervention, there is a 10-fold increase in number of palliative care consultation requests from oncology clinics from fiscal year 2014 to 2017. Increase in percentage of inpatients deaths with prior palliative care consultation: Since the implementation of this model, there is an increase in the percentage of inpatient deaths with prior palliative care consultations; from 75% in fiscal year 2014 to 97% in fiscal year 2017.

Challenges/Limitations: Single clinic setting, with one oncologist and palliative care physician, palliative care staffing, clinic space, administrative support.

Conclusions: Studies are needed to show impact of palliative care integration on acute care utilization, hospice care accession and satisfaction with care. There is a need to explore improved training and structures for both oncology and palliative care teams.

Background: Early introduction of palliative care for oncology patients has demonstrated enhanced quality of life and satisfaction. We developed a model for integrating palliative care into outpatient oncology care.

Hypothesis: Optimal integration of oncology and palliative care requires palliative care clinician’s presence at initial, and many subsequent, patient encounters.

Objective: To implement and evaluate outpatient integrated oncology and palliative care.

Method: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated outpatient practice of oncology and palliative care with: Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify patients in need of palliative care; shared palliative care-oncology appointments. Initial visit: New oncology patients are seen by an oncologist and palliative care physician together. Palliative care physician introduces palliative care and initiates advance care planning. Concurrent oncology-palliative care follow-up: High-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc) are followed by oncologist and palliative care physician. Palliative care physician facilitates goals of care discussions and addresses symptom management. End-of-life care: Hospice care remains a part of oncology care. Palliative care physician and oncology team co-manage all oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

Results: Increase in palliative care consults from oncology clinics: After this intervention, there is a 10-fold increase in number of palliative care consultation requests from oncology clinics from fiscal year 2014 to 2017. Increase in percentage of inpatients deaths with prior palliative care consultation: Since the implementation of this model, there is an increase in the percentage of inpatient deaths with prior palliative care consultations; from 75% in fiscal year 2014 to 97% in fiscal year 2017.

Challenges/Limitations: Single clinic setting, with one oncologist and palliative care physician, palliative care staffing, clinic space, administrative support.

Conclusions: Studies are needed to show impact of palliative care integration on acute care utilization, hospice care accession and satisfaction with care. There is a need to explore improved training and structures for both oncology and palliative care teams.

Background: Early introduction of palliative care for oncology patients has demonstrated enhanced quality of life and satisfaction. We developed a model for integrating palliative care into outpatient oncology care.

Hypothesis: Optimal integration of oncology and palliative care requires palliative care clinician’s presence at initial, and many subsequent, patient encounters.

Objective: To implement and evaluate outpatient integrated oncology and palliative care.

Method: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated outpatient practice of oncology and palliative care with: Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify patients in need of palliative care; shared palliative care-oncology appointments. Initial visit: New oncology patients are seen by an oncologist and palliative care physician together. Palliative care physician introduces palliative care and initiates advance care planning. Concurrent oncology-palliative care follow-up: High-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc) are followed by oncologist and palliative care physician. Palliative care physician facilitates goals of care discussions and addresses symptom management. End-of-life care: Hospice care remains a part of oncology care. Palliative care physician and oncology team co-manage all oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

Results: Increase in palliative care consults from oncology clinics: After this intervention, there is a 10-fold increase in number of palliative care consultation requests from oncology clinics from fiscal year 2014 to 2017. Increase in percentage of inpatients deaths with prior palliative care consultation: Since the implementation of this model, there is an increase in the percentage of inpatient deaths with prior palliative care consultations; from 75% in fiscal year 2014 to 97% in fiscal year 2017.

Challenges/Limitations: Single clinic setting, with one oncologist and palliative care physician, palliative care staffing, clinic space, administrative support.

Conclusions: Studies are needed to show impact of palliative care integration on acute care utilization, hospice care accession and satisfaction with care. There is a need to explore improved training and structures for both oncology and palliative care teams.

Better ICU staff communication with family may improve end-of-life choices

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A family communication intervention didn’t improve 6-month psychological symptoms among those with loved ones in intensive care units.

Major finding: There was no significant difference on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at 6 months (11.7 vs. 12 points).

Study details: The study randomized 1,420 ICU patients and surrogates to the intervention or to usual care.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White had no financial disclosures.

Source: White et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75.

Medicare hospital deaths decline, hospice usage increases

Since 2000, Medicare beneficiaries have become less likely to die in hospitals, and more likely to die in their homes or in community health care facilities.

A review of Medicare records also determined that there was a decline in health care transitions in the final 3 days of life for these patients, Joan M. Teno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA.

It is not possible to identify a specific reason for the shift, wrote Dr. Teno, professor of medicine at the Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. Between the study years of 2000 and 2015, there were several large efforts to improve care at the end of life.

“Since 2009, programs ranging from ensuring informed patient decision making to enhanced care coordination have had the goal of improving care at the end of life. Specific interventions have included promoting conversations about the goals of care, continued growth of hospice services and palliative care, and the debate and passage of the Affordable Care Act … It is difficult to disentangle efforts such as public education, promotion of advance directives through the Patient Self- Determination Act, increased access to hospice and palliative care services, financial incentives of payment policies, and other secular changes.”

The study mined data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and examined end-of-life outcomes among two Medicare groups: Medicare fee-for-service recipients (1,361,870) during 2009-2015, and Medicare Advantage recipients (871,845), comparing 2011 and 2015. The mean age of both cohorts was 82 years.

Outcomes included site of death and “potentially burdensome transitions,” during the last days of life. These were defined as three or more hospitalizations in the previous 3 months, or two or more hospitalizations for pneumonia, urinary tract infection, dehydration, or sepsis during the last 120 days of life. Prolonged mechanical ventilation also was deemed potentially burdensome.

Among fee-for-service recipients, deaths in acute care hospitals declined from 32.6% to19.8%. Deaths in nursing homes remained steady, at 27.2% and 24.9%. Many of these deaths (42.9%) were preceded by a stay in an ICU. There was a transient increase in end-of-life ICU use, around 2009, but by 2015, the percentage was down to 29%, compared with 65.2% in 2000.

Transitions between a nursing home and hospital in the last 90 days of life were 0.49/person in 2000 and 0.33/person in 2015. Hospitalizations for infection or dehydration fell from 14.6% to12.2%. Hospitalization with prolonged ventilation fell from 3.1% to 2.5%.

Dying in hospice care increased from 21.6% to 50.4%, and people were taking advantage of hospice services longer: the proportion using short-term services (3 days or less) fell from 9.8% to 7.7%.

Among Medicare Advantage recipients, the numbers were somewhat different. More than 50% of recipients entered hospice care in both 2011 and 2015; in both years, 8% had services for more than 3 days. About 27% had ICU care in the last days of life, in both years. Compared to fee-for-service recipients, fewer Medicare Advantage patients were in nursing homes at the time of death, and that number declined from 2011 to 2015 (37.7% to 33.2%).

In each year, about 10% of these patients had a hospitalization for dehydration or infection, and 3% had a stay requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation in each year. The mean number of health care transitions remained steady, at 0.23 and 0.21 per person each year.

Dr. Teno had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Teno JM et al. JAMA. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8981.

Since 2000, Medicare beneficiaries have become less likely to die in hospitals, and more likely to die in their homes or in community health care facilities.

A review of Medicare records also determined that there was a decline in health care transitions in the final 3 days of life for these patients, Joan M. Teno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA.

It is not possible to identify a specific reason for the shift, wrote Dr. Teno, professor of medicine at the Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. Between the study years of 2000 and 2015, there were several large efforts to improve care at the end of life.

“Since 2009, programs ranging from ensuring informed patient decision making to enhanced care coordination have had the goal of improving care at the end of life. Specific interventions have included promoting conversations about the goals of care, continued growth of hospice services and palliative care, and the debate and passage of the Affordable Care Act … It is difficult to disentangle efforts such as public education, promotion of advance directives through the Patient Self- Determination Act, increased access to hospice and palliative care services, financial incentives of payment policies, and other secular changes.”

The study mined data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and examined end-of-life outcomes among two Medicare groups: Medicare fee-for-service recipients (1,361,870) during 2009-2015, and Medicare Advantage recipients (871,845), comparing 2011 and 2015. The mean age of both cohorts was 82 years.

Outcomes included site of death and “potentially burdensome transitions,” during the last days of life. These were defined as three or more hospitalizations in the previous 3 months, or two or more hospitalizations for pneumonia, urinary tract infection, dehydration, or sepsis during the last 120 days of life. Prolonged mechanical ventilation also was deemed potentially burdensome.

Among fee-for-service recipients, deaths in acute care hospitals declined from 32.6% to19.8%. Deaths in nursing homes remained steady, at 27.2% and 24.9%. Many of these deaths (42.9%) were preceded by a stay in an ICU. There was a transient increase in end-of-life ICU use, around 2009, but by 2015, the percentage was down to 29%, compared with 65.2% in 2000.

Transitions between a nursing home and hospital in the last 90 days of life were 0.49/person in 2000 and 0.33/person in 2015. Hospitalizations for infection or dehydration fell from 14.6% to12.2%. Hospitalization with prolonged ventilation fell from 3.1% to 2.5%.

Dying in hospice care increased from 21.6% to 50.4%, and people were taking advantage of hospice services longer: the proportion using short-term services (3 days or less) fell from 9.8% to 7.7%.

Among Medicare Advantage recipients, the numbers were somewhat different. More than 50% of recipients entered hospice care in both 2011 and 2015; in both years, 8% had services for more than 3 days. About 27% had ICU care in the last days of life, in both years. Compared to fee-for-service recipients, fewer Medicare Advantage patients were in nursing homes at the time of death, and that number declined from 2011 to 2015 (37.7% to 33.2%).

In each year, about 10% of these patients had a hospitalization for dehydration or infection, and 3% had a stay requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation in each year. The mean number of health care transitions remained steady, at 0.23 and 0.21 per person each year.

Dr. Teno had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Teno JM et al. JAMA. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8981.

Since 2000, Medicare beneficiaries have become less likely to die in hospitals, and more likely to die in their homes or in community health care facilities.

A review of Medicare records also determined that there was a decline in health care transitions in the final 3 days of life for these patients, Joan M. Teno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA.

It is not possible to identify a specific reason for the shift, wrote Dr. Teno, professor of medicine at the Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. Between the study years of 2000 and 2015, there were several large efforts to improve care at the end of life.

“Since 2009, programs ranging from ensuring informed patient decision making to enhanced care coordination have had the goal of improving care at the end of life. Specific interventions have included promoting conversations about the goals of care, continued growth of hospice services and palliative care, and the debate and passage of the Affordable Care Act … It is difficult to disentangle efforts such as public education, promotion of advance directives through the Patient Self- Determination Act, increased access to hospice and palliative care services, financial incentives of payment policies, and other secular changes.”

The study mined data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and examined end-of-life outcomes among two Medicare groups: Medicare fee-for-service recipients (1,361,870) during 2009-2015, and Medicare Advantage recipients (871,845), comparing 2011 and 2015. The mean age of both cohorts was 82 years.

Outcomes included site of death and “potentially burdensome transitions,” during the last days of life. These were defined as three or more hospitalizations in the previous 3 months, or two or more hospitalizations for pneumonia, urinary tract infection, dehydration, or sepsis during the last 120 days of life. Prolonged mechanical ventilation also was deemed potentially burdensome.

Among fee-for-service recipients, deaths in acute care hospitals declined from 32.6% to19.8%. Deaths in nursing homes remained steady, at 27.2% and 24.9%. Many of these deaths (42.9%) were preceded by a stay in an ICU. There was a transient increase in end-of-life ICU use, around 2009, but by 2015, the percentage was down to 29%, compared with 65.2% in 2000.

Transitions between a nursing home and hospital in the last 90 days of life were 0.49/person in 2000 and 0.33/person in 2015. Hospitalizations for infection or dehydration fell from 14.6% to12.2%. Hospitalization with prolonged ventilation fell from 3.1% to 2.5%.

Dying in hospice care increased from 21.6% to 50.4%, and people were taking advantage of hospice services longer: the proportion using short-term services (3 days or less) fell from 9.8% to 7.7%.

Among Medicare Advantage recipients, the numbers were somewhat different. More than 50% of recipients entered hospice care in both 2011 and 2015; in both years, 8% had services for more than 3 days. About 27% had ICU care in the last days of life, in both years. Compared to fee-for-service recipients, fewer Medicare Advantage patients were in nursing homes at the time of death, and that number declined from 2011 to 2015 (37.7% to 33.2%).

In each year, about 10% of these patients had a hospitalization for dehydration or infection, and 3% had a stay requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation in each year. The mean number of health care transitions remained steady, at 0.23 and 0.21 per person each year.

Dr. Teno had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Teno JM et al. JAMA. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8981.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: During 2000-2015, Medicare recipients became less likely to die in hospitals.

Major finding:

Study details: The retrospective study comprised more than 2.3 million Medicare recipients.

Disclosures: Dr. Teno had no financial disclosures.

Source: Teno JM et al. JAMA. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8981.

Cancer Care Collaborative Approach to Optimize Clinical Care (FULL)

A collaboration between clinicians and industrial engineers resulted in significant improvements in cancer screening, the development of toolkits, and more efficient care for hepatocellular carcinoma and breast, colorectal, lung, head and neck, and prostate cancers.

Cancer is one of the most common causes of premature death and disability that requires long-term follow-up surveillance and oftentimes ongoing treatment for survivors that can lead to important health, psychosocial

Like other cancer treatment systems, the VA faces some challenges in timeliness, surveillance, and quality of the cancer care process.12-18 Although implementation of cancer patientcentered home care and other efforts were developed to improve delivery and efficiency of cancer care in VA and non-VA facilities, the patient continuum of care remains convoluted.2,19-23

In 2004, the Clinical Cancer Care Collaborative (C4), a national VA program, was launched to improve timeliness, quality, access improvement, efficiency, and the “sustainability and spread” of successful programs at the VA. This program included representatives throughout the VA and encompassed cancer care coordinators (clinical nurse navigators), advisory panels, and a multidisciplinary team of clinicians.

In 2009, the VA promoted the Cancer Care Collaborative (CCC) to focus on optimizing the timeliness and quality of colorectal, breast, lung, prostate, and hematologic cancer care throughout the VA health care system. The VA Office of Systems Redesign (SR) partnered with the VA-Center for Applied Systems Engineering (VA-CASE) Veteran Engineering Resource Center (VERC), including industrial engineers (IEs) to provide their expertise and support. The CCC provided a forum to develop teams; set aims; and map, measure, analyze, and implement changes to assure timely diagnosis and initiation of evidence-based treatment and subsequently sustain the practices that led to improvements in these areas.

The CCC structure was separated into 6 distinct support areas: (1) industrial/systems engineering support; (2) informatics and clinical application support; (3) development and dissemination of improvement resource guides; (4) real-time and rapid-cycle evaluation tools and approaches; (5) application of advanced operational systems engineering techniques, such as simulation and modeling to inform further system optimization; and (6) advisory panels focused on quality topics that were identified, developed, implemented, and evaluated by the participants with support from the CCC faculty.

Here the authors describe the framework of the CCC model developed by VA-CASE, demonstrate the performance improvement results of teams focusing on several types of cancer, and highlight the key indicators to best practices.

Methods

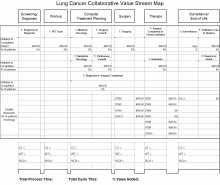

Figure 1 outlines the CCC 3-Phase Conceptual Model. Phase 1 included diagnosis (screening and symptoms); phase 2 included treatment (from diagnosis to beyond treatment); and phase 3 was designed for hub and spoke facilities where screening/diagnosis occurs in a smaller (spoke) facility and treatment occurs in the larger (hub) facility.

In the first phase, 18 facility-based teams were selected through an application and interview process and immediately applied SR to their team’s specific improvement projects, which included the following cancers: breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate.

In addition to the cancer types covered in the initial phase, phase 2 also included hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and head and neck cancers. National VHA Toolkits were products that developed from and for use in lung and colorectal cancers (CRCs) (phases 1 and 2). These were organized and disseminated throughout the entire VA, offering specific knowledge and tools that could be applied to improving cancer care. The toolkit included guidance documents, specific process examples, and items that could be downloaded into Microsoft SharePoint (Redmond, WA) for adaptation and use by VA facilities. The toolkit contents were primarily developed and/or identified by CCC participants and funded by the VA Office of Quality and Performance (OQP) and SR. The toolkits included links to the following resources for each cancer type in phase 2: quality indicators, tool tables, timeliness measures, understanding the continuum of care, and a resource entitled, “How Can the Quality Metrics Help Me?” (eAppendix 1, available at fedprac.com/AVAHO).

The phase 3 collaborative was designed for hub and spoke facilities by focusing on current state vs ideal state processes, communication patterns, and care coordination between the hub and spoke facilities. There were 10 facilities in which all teams focused on lung cancer. Each facility was made up of 1 hub and had the ability to send up to 8 participants (from either the hub or the spoke facility) to the CCC workgroup meetings. Participants were specialists, radiologists, primary care providers, pathologists, nurses, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants.

Conceptual Model Deployment

The deployment of the CCC 3-phase conceptual model was based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Breakthrough Series Collaborative Model.24,25 Implementation was carried out over 3 phases (2005-2011) after proper teaching, coaching, and learning sessions (LS)

Each LS incorporated instruction in basic systems engineering and Lean Six Sigma principles (an approach to quality improvement that focuses on reducing waste and variability) with practical, health care-based examples, case studies, and immediate application of the VA-TAMMCS (vision/analyze, team/aim, map, measure, change, sustain) SR organizational framework (Figure 2), tools, and methodologies to the process under investigation.26 The VA-TAMMCS (eAppendix 2, available at fedprac.com/AVAHO)

The CCC encouraged joint facilitation. A SR clinical coach, a VERC IE, and participating facilities were required to work together intensively (mentor and support) for 10 to 12 months. The mix of clinicians and engineers helped the facilities by bringing in diverse perspectives, which led to better decisions in the improvement of cancer care.28 During the CCC, the IEs partnered with and supported clinicians, using Lean Six Sigma and SR tools and approaches to health care quality improvement to quickly make improvements in efficiency and quality (eAppendix 3a, 3b, and 3c, available at fedprac.com/AVAHO).26,29

The IEs provided on-site support at all participating VAMCs during all 3 phases by providing the clinical teams with a variety of VA-TAMMCS process improvement tools to support the analysis and improvement of their organizations.

Data Collection

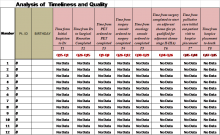

As part of the overall improvement process, the facilities worked on several aim statements in order to improve a primary constraint; such as timeliness and quality of care. An aim statement communicates what you want to do (eg, reduce, improve, or eliminate), by how much, and when. In order to improve timeliness, the CCC focused on measures from first evidence to tissue diagnosis, from diagnosis to treatment, and also intermediate measures, such as time from positron emission tomography scan ordered to completion. While working on overall quality of care unique to cancer, the CCC focused on measures related to documentation compliance and consistency of care provided to patients.

Phase 1

Facilities were to optimize their process (time from initial suspicion to diagnosis). Hence, participating facilities were allowed to simply identify their aim statement and pick and choose the area of focus.

Phases 2 and 3

Timeliness Aims. These aims were addressed through improvements in information technology in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) electronic medical record by creating electronic order sets containing codes that alert providers daily to retrieve and follow up on abnormal test results. Primary care physicians and front desk staff also were educated on the use of these order sets and to schedule a follow-up test or specialist consult within 3 to 7 days.

Aim 1: Reduce to 15 days the time from initial suspicion to diagnosis within 1 year.

Aim 2: Reduce to 30 days the time from diagnosis to start of treatment within 1 year.

Quality Aim. Improve the compliance rate of identified quality indicators to 100% within 1 year.

Measurement Tools

The Cancer Care Measurement Tools were designed to support the OQP performance metric (Figure 3). The OQP creates and collects data on evidence-based national benchmarks to measure the quality of preventive and therapeutic health care services at the facility, VISN, and national levels. These metrics may be performance measures, performance monitors, quality indicators, and special studies, among other measures, to support clinicians, managers, and employees in improving care to veterans.

For each of the 3 CCC phases, VA-CASE IEs facilitated the development of standardized measurement and tracking tools for each cancer type. The tools identified key timeliness and quality measures as a function of entered patient data (eAppendixes 4-7, available at fedprac.com/AVAHO).

Quality Improvement Toolkit Series

The Quality Improvement Toolkit Series (QITS) was created for VA clinical managers and policy makers to improve diagnosis, treatment, and patient outcomes for high-priority conditions. The goal of the QITS is to serve as the cancer care improvement resource guide to produce and disseminate the National Quality Improvement Toolkit resource.

Each tool included in the QITS is matched to 1 or more metrics of the OQP (such as a performance measure or quality indicator). For example, the types of tools include CPRS order sets and templates, enhanced registries and patient databases, service agreements, and care process flow maps. Each toolkit served as a resource for improving facility performance on a specific set of established performance measures and/or quality indicators. Toolkits that helped VA facilities improve performance on OQP quality indicators and performance measures were based on the VA-TAMMCS model and continuous improvement that was tailored to the structure and needs of the VA system. The VA-CASE staff provided guidance on the criteria for inclusion in the toolkits to promote best practice and quality in clinical practice. The criteria used by a condition-specific expert panel were based on whether or not it was (1) not already part of VA routine care nationwide; (2) can be matched to 1 or more VA quality metrics/indicators; and (3) currently in use at a health care facility (innovative VA colleagues nationwide and by non-VA health care organizations).

Evaluation

After each LS, VA CCC evaluation data were collected using standardized 5-point Likert scale questions.

Results

Industrial engineers provided > 1,200 days of on-site support across the 60 teams and built 63 flow maps and 47 customized tools based on the team’s requests throughout the implementation period. Throughout the 3-phase CCC, the IEs developed standardized measurement and tracking tools for each cancer type (lung, colorectal, prostate, head and neck, and HCC). Outcomes included the sharing of best practices that spread across programs (uploaded to the national QITS site, available only to VA employees); as well as enterprisewide development of the special interest group (eg, VHA survivorship), which led to a national survivorship toolkit.

The table illustrates the overall collaborative impact across the CCC. In phase 1, 78% of the 64 aims (breast, CRC, lung, prostate) were met at 18 facilities. In phase 2, 72% of the 94 aims (CRC; HCC; and head and neck, lung, and prostate cancers) were met at 21 facilities. In phase 3, 47% of the 64 aims for head and neck and lung cancer were met at 11 facilities. The difference in the percentage of aims met during each phase was due to the variations in complexity of cancer types as well as additional logistic barriers at each institution.

Discussion

Overall, the CCC had a positive impact that improved timeliness, accessibility, and quality of the cancer care process in participating VAMCs. The majority of VAMCs focused on optimizing the lung cancer care process in all the phases of the collaborative, given that lung cancer suspicion-to-treatment process is highly complex, requiring multiple departments to coordinate workup and care, leading to the greatest room for improvement.

Industrial engineers introduced a variety of approaches to improvement to the collaborative teams, and they were integral to the development of standardized measurement and tracking tools for each type of cancer, introducing advanced SR methods for specific aims and performing appropriate data analysis. The ability of the VA system to recognize where improvements were needed was complemented by the efforts of VA clinicians and administration with direction from VERC IEs and their toolkits. Improvements were made, sometimes decreasing time from diagnosis to treatment by 50%. The VA facilities were encouraged to sustain this improvement using the toolkits with continued data gathering and implementation. In phase 1, lung cancer improvements included (1) establishing the multidisciplinary clinic, multidisciplinary rounds, and improved communication among key service lines; (2) developing a database (measurement tool) to prospectively track all cancer patients; (3) scheduling weekly multidisciplinary meetings to provide a mechanism to rapidly review patients and triage to appropriate pathways in the treatment algorithm; and (4) increasing physician participation, including oncologists, surgeons, radiologists, and radiation oncologists, to identify methods and process

changes that could eliminate wasteful steps and improve access for expediting diagnosis and treatment of patients with lung cancer who require surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation. The overall impact on time from abnormal CT to lung cancer surgery was reduced by > 5 months from 180 to 20 days. Substantial improvements were made in timeliness and reliability in caring for veterans with lung cancer.12

Groundbreaking work and exceptional results continued in the second phase for lung cancer care. In addition, the creation of a prostate cancer care web-based clinical measurement tool helped to improve the ability to proactively manage patients. The tool included same-day scheduling of biopsy and urology appointments for veterans with possible prostate cancer and the development of a protocol for expedited high-risk patients with metastatic disease. Ultimately, the wait time from urology consult to diagnosis was cut from 96 to 46 days for veterans with prostate cancer (Figure 4).

Once the face-to-face CCC process was established, tested, refined, and replicated successfully, the virtual team proved to be a cost-effective model. The virtual team did not travel to LSs, a major source of expense, so a process was set in place for their participation in all other facets of the collaborative. This led to the pilot testing of national virtual collaboratives (eg, specialty and surgical care collaboratives).

The toolkits for lung and CRC (phases 1 and 2) were organized, standardized, and disseminated throughout the VA to provide specific knowledge and tools to improve cancer care. The content of toolkits was primarily developed and/or identified by CCC participants. Funding for the toolkits was secured by OQP and SR, which led to the creation of the integration and crosswalk documents (eAppendix 7, available at fedprac.com/AVAHO).

In phase 3, lung cancer care teams showed the most improvement among all 3 phases of the collaborative. Aims statements in lung cancer process showed an increased percentage of improvement in all phases. Weekly multidisciplinary meetings provided a mechanism to rapidly review patients and triage appropriate pathways in the treatment algorithm. Open communication among sites and disciplines was vital and increased participation by physicians to identify ways to expedite diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. In addition to access and timeliness of care (accommodating patients’ preference for scheduling), the teams identified areas they deemed important for successful programs and developed advisory panels that focused on quality, such as tumor boards, clinical trials, patient education, cancer care coordinator/navigator, survivorship, standard order sets and progress notes, reliable handoff, chemotherapy and radiation make/buy tools, head and neck toolkit, clinical documentation, chemotherapy efficiency, and Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation recovery for metastatic cancer.

Based on the evaluation results, participants gave their highest average ratings to items that asked about the general potential of SR to improve patient care and patient satisfaction, team dynamics, site leadership support; confidence in self, team, and coach; and the general potential of SR to improve staff satisfaction. Participants gave their lowest ratings to questions that asked about having the necessary time and resources to implement SR initiatives at their site as well as the level of active engagement by site leadership in SR work.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Klemp JR. Breast cancer prevention across the cancer care continuum. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2015;31(2):89-99.

2. Tralongo P, Ferraù F, Borsellino N, et al. Cancer patientcentered home care: a new model for health care in oncology. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:387-392.

3. Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2013/Quality-Cancer-Care/qualitycancercare_rb.pdf. Published September 2013. Accessed April 6, 2017.

4. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69-90.

5. Jabaaij L, van den Akker M, Schellevis FG. Excess of health care use in general practice and of comorbid chronic conditions in cancer patients compared to controls. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:60

6. Brazil K, Whelan T, O’Brien MA, Sussman J, Pyette N, Bainbridge D. Towards improving the co-ordination of supportive cancer care services in the community. Health Policy. 2004;70(1):125-131.

7. Husain A, Barbera L, Howell D, Moineddin R, Bezjak A, Sussman J. Advanced lung cancer patients’ experience with continuity of care and supportive care needs. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(5):1351-1358.

8. Sayed S, Moloo Z, Bird P, et al. Breast cancer diagnosis in a resource poor environment through a collaborative multidisciplinary approach: the Kenyan experience. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66(4):307-311.

9. Morgan PA, Murray S, Moffatt CJ, Honnor A. The challenges of managing complex lymphoedema/chronic oedema in the UK and Canada. Int Wound J. 2011;9(1):54-69.

10. Renshaw M. Lymphorrhoea: ‘leaky legs’ are not just the nurse’s problem. Br J Community Nurs. 2007;12(4):S18-S21.

11. Morgan PA. Health professionals’ ideal roles in lympoedema management. Br J Community Nurs. 2006;11(suppl):5-8.

12. Hunnibell LS, Rose MG, Connery DM, et al. Using nurse navigation to improve timeliness of lung cancer care at a veterans hospital. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(1):29-36.

13. Schultz EM, Powell AA, McMillan A, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with timeliness of care in veterans with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(7):

595-600.

14. Gould MK, Ghaus SJ, Olsson JK, Schultz EM. Timeliness of care in veterans with non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2008;133(5):1167-1173.

15. Jackson GL, Melton LD, Abbott DH, et al. Quality of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3176-3181.

16. Walling AM, Tisnado D, Asch SM, et al. The quality of supportive cancer care in the Veterans Affairs system and targets for improvement. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2071-2079.

17. Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Quality of care for older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(11):727-736.

18. Kaiser AM, Nunoo-Mensah JW, Wasserberg N. Surgical volume and long-term survival following surgery for colorectal cancer in the Veterans Affairs Health-Care System. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):250.

19. Abrahams E, Foti M, Kean MA. Accelerating the delivery of patient-centered, high-quality cancer care. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(10):2263-2267.

20. Taplin SH, Weaver S, Salas E, et al. Reviewing cancer care team effectiveness. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):239-246.

21. Kosty MP, Bruinooge SS, Cox JV. Intentional approach to team-based oncology care: evidence-based teamwork to improve collaboration and patient engagement. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):247-248.

22. Ko NY, Darnell JS, Calhoun E, et al. Can patient navigation improve receipt of recommended breast cancer care? Evidence from the National Patient Navigation Research Program. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(25):2758-2764.

23. Zapka JG, Taplin SH, Solberg LI, Manos MM. A framework for improving the quality of cancer care: the case of breast and cervical cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(1):4-13.

24. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Boston, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003.

25. Boushon B, Provost L, Gagnon J, Carver P. Using a virtual breakthrough series collaborative to improve access in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(10):573-584.

26. Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1996.

27. Bidassie B, Davies ML, Stark R, Boushon B. VA experience in implementing patient-centered medical home using a breakthrough series collaborative. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(suppl 2):S563-S5671.

28. Bidassie B, Williams LS, Woodward-Hagg H, Matthias MS, Damush TM. Key components of external facilitation in an acute stroke quality improvement collaborative in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):69.

29. Woodward-Hagg H, Workman-Germann J, Flanagan M, et al. Implementation of systems redesign: approaches to spread and sustain adoption. In: Henriksen K, Battles J, Keyes M, Grady ML, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches: Vol. 2: Culture and Redesign. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

30. American Cancer Society. National roundtable recognizes leaders in colorectal cancer prevention effort with 80% by 2018 National Achievement Award. [press release]. http://pressroom.cancer.org/2017-02-01-National-Colorectal-Cancer-Roundtable-Recognizes-Leaders-in-Colorectal-Cancer-Prevention-Effort-with-80-by-2018-National-Achievement-Award. Published February 1, 2017. Accessed March 29, 2017.

31. Margolis PA, Lannon CM, Stuart JM, Fried BJ, Keyes-Elstein L, Moore DE Jr. Practice based education to improve delivery systems for prevention in primary care: randomized trial. BMJ. 2004;328(7436):388.

A collaboration between clinicians and industrial engineers resulted in significant improvements in cancer screening, the development of toolkits, and more efficient care for hepatocellular carcinoma and breast, colorectal, lung, head and neck, and prostate cancers.

Cancer is one of the most common causes of premature death and disability that requires long-term follow-up surveillance and oftentimes ongoing treatment for survivors that can lead to important health, psychosocial

Like other cancer treatment systems, the VA faces some challenges in timeliness, surveillance, and quality of the cancer care process.12-18 Although implementation of cancer patientcentered home care and other efforts were developed to improve delivery and efficiency of cancer care in VA and non-VA facilities, the patient continuum of care remains convoluted.2,19-23