User login

Palliative Care: Ave atque vale

Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the modern hospice movement, gave me this advice early in my palliative medicine career: “Never stop thanking those who help you along.” There are many to thank and much to be thankful for since the palliative care series in ACS Surgery News commenced in September 2012. The series proposal was enthusiastically endorsed by the then Editor, Layton F. Rikkers, and promptly launched owing to the personal interest of the first series editor, Elizabeth Wood. Their strong advocacy continues with the current co-editors, Karen Deveney and Tyler Hughes and the ever-watchful eye and assistance of managing editor, Therese Borden.

The purpose of the series was to keep the concept of surgical palliative care visible to the Fellowship through the reflections of surgeons and surgeons in training, while commenting on timely issues relevant to palliative care. We were fortunate to be coupled with Peter Angelos’s astute, widely read series on ethics. Our respective areas of interest widely overlap and have come into sharper focus for the surgical community over roughly the same period of time.

It was my hope that our contributions on palliative care would emulate the qualities and quality of Dr. Angelos’s articles – commentaries that would be of interest to the entire spectrum of surgical specialties and venues of practice. While the ethics column focused on doing the right thing, we would be focused on how to do the right thing in our response to suffering. Thanks are due to ACS Surgery News for its consistent representation of the new specialty of surgical palliative care on a par with other surgical specialties. It is culturally significant that this advocacy included strong support from laypeople.

I have been gratified and am thankful for the frequent uplifting discussions and debates triggered by palliative care columns in well-thumbed copies of ACS Surgery News in our OR lounge.

I didn’t have to look far to find inspiration and direction for the advocacy of palliative care in surgical practice. My father, David D. Dunn, MD, FACS, who represented everything noble, humane, and sensible in surgery, was a community-based general surgeon practicing in an era when the “general surgeon” performed thoracic, vascular, trauma, pediatric, and plastic surgery in addition to abdominal surgery. He had extensive experience with responding to suffering in a fundamentally affirmative way. He founded the first hospice in our community to meet the needs of a proud, cantankerous, elderly man septic with a gangrenous leg who declined amputation. He also witnessed mass suffering when he commanded a field hospital tasked with the resuscitation of survivors of a liberated Nazi concentration camp. The experience could have easily destroyed him from the resulting cynicism about humanity or PTSD. But instead he claimed he learned the first step in responding to mass calamity is the resuscitation of hope. He recalled a rescued physician who was given a clean lab coat and a stethoscope even before he was given his first real meal in years. He believed the hallmarks of steadfastness and non-abandonment are the core of the surgical persona. Late in his long life that ended just before this series launched, he observed, “It’s all palliative when you get right down to it. You [meaning the next generation] have to figure out the details and do your bit.”

The future is bright to “figure out the details and do your bit” for surgeons interested in palliative care. A number of young surgeons and surgeons in training, some who have done fellowships and become ABS certified in Hospice and Palliative Medicine, have had the opportunity to be heard and their specialty field be recognized by the greater surgical community because of ACS Surgery News.

I once asked a physically and emotionally exhausted family member of an “ICU to nowhere” patient why he thought patients get “stuck” in the ICU. He answered eloquently, “People just don’t think they should die.” The prevailing biophysical and increasingly “corporate” framework for care of the seriously ill is handicapped by its inability to effectively respond to the psychological and spiritual questions raised by this comment. Inability of surgeons to reconcile personal moral imperatives with big data and corporate medicine may be contributing to burnout, one of the most frequently acknowledged problems for surgeons today. Disease management alone, even if completely evidence-based, will not break this type of gridlock nor leave patients, families, and practitioners with a lasting sense of support. We will always need a broader framework that gives us a lens through which we can see and a voice with which we can answer the serious concerns that trouble our seriously ill patients and their families. I thank ACS Surgery News for conscientiously providing us a lens and a voice over the past 7 years.

Dr. Dunn was formerly the medical director of the palliative care consultation service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot in Erie, Pa., and Chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the modern hospice movement, gave me this advice early in my palliative medicine career: “Never stop thanking those who help you along.” There are many to thank and much to be thankful for since the palliative care series in ACS Surgery News commenced in September 2012. The series proposal was enthusiastically endorsed by the then Editor, Layton F. Rikkers, and promptly launched owing to the personal interest of the first series editor, Elizabeth Wood. Their strong advocacy continues with the current co-editors, Karen Deveney and Tyler Hughes and the ever-watchful eye and assistance of managing editor, Therese Borden.

The purpose of the series was to keep the concept of surgical palliative care visible to the Fellowship through the reflections of surgeons and surgeons in training, while commenting on timely issues relevant to palliative care. We were fortunate to be coupled with Peter Angelos’s astute, widely read series on ethics. Our respective areas of interest widely overlap and have come into sharper focus for the surgical community over roughly the same period of time.

It was my hope that our contributions on palliative care would emulate the qualities and quality of Dr. Angelos’s articles – commentaries that would be of interest to the entire spectrum of surgical specialties and venues of practice. While the ethics column focused on doing the right thing, we would be focused on how to do the right thing in our response to suffering. Thanks are due to ACS Surgery News for its consistent representation of the new specialty of surgical palliative care on a par with other surgical specialties. It is culturally significant that this advocacy included strong support from laypeople.

I have been gratified and am thankful for the frequent uplifting discussions and debates triggered by palliative care columns in well-thumbed copies of ACS Surgery News in our OR lounge.

I didn’t have to look far to find inspiration and direction for the advocacy of palliative care in surgical practice. My father, David D. Dunn, MD, FACS, who represented everything noble, humane, and sensible in surgery, was a community-based general surgeon practicing in an era when the “general surgeon” performed thoracic, vascular, trauma, pediatric, and plastic surgery in addition to abdominal surgery. He had extensive experience with responding to suffering in a fundamentally affirmative way. He founded the first hospice in our community to meet the needs of a proud, cantankerous, elderly man septic with a gangrenous leg who declined amputation. He also witnessed mass suffering when he commanded a field hospital tasked with the resuscitation of survivors of a liberated Nazi concentration camp. The experience could have easily destroyed him from the resulting cynicism about humanity or PTSD. But instead he claimed he learned the first step in responding to mass calamity is the resuscitation of hope. He recalled a rescued physician who was given a clean lab coat and a stethoscope even before he was given his first real meal in years. He believed the hallmarks of steadfastness and non-abandonment are the core of the surgical persona. Late in his long life that ended just before this series launched, he observed, “It’s all palliative when you get right down to it. You [meaning the next generation] have to figure out the details and do your bit.”

The future is bright to “figure out the details and do your bit” for surgeons interested in palliative care. A number of young surgeons and surgeons in training, some who have done fellowships and become ABS certified in Hospice and Palliative Medicine, have had the opportunity to be heard and their specialty field be recognized by the greater surgical community because of ACS Surgery News.

I once asked a physically and emotionally exhausted family member of an “ICU to nowhere” patient why he thought patients get “stuck” in the ICU. He answered eloquently, “People just don’t think they should die.” The prevailing biophysical and increasingly “corporate” framework for care of the seriously ill is handicapped by its inability to effectively respond to the psychological and spiritual questions raised by this comment. Inability of surgeons to reconcile personal moral imperatives with big data and corporate medicine may be contributing to burnout, one of the most frequently acknowledged problems for surgeons today. Disease management alone, even if completely evidence-based, will not break this type of gridlock nor leave patients, families, and practitioners with a lasting sense of support. We will always need a broader framework that gives us a lens through which we can see and a voice with which we can answer the serious concerns that trouble our seriously ill patients and their families. I thank ACS Surgery News for conscientiously providing us a lens and a voice over the past 7 years.

Dr. Dunn was formerly the medical director of the palliative care consultation service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot in Erie, Pa., and Chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the modern hospice movement, gave me this advice early in my palliative medicine career: “Never stop thanking those who help you along.” There are many to thank and much to be thankful for since the palliative care series in ACS Surgery News commenced in September 2012. The series proposal was enthusiastically endorsed by the then Editor, Layton F. Rikkers, and promptly launched owing to the personal interest of the first series editor, Elizabeth Wood. Their strong advocacy continues with the current co-editors, Karen Deveney and Tyler Hughes and the ever-watchful eye and assistance of managing editor, Therese Borden.

The purpose of the series was to keep the concept of surgical palliative care visible to the Fellowship through the reflections of surgeons and surgeons in training, while commenting on timely issues relevant to palliative care. We were fortunate to be coupled with Peter Angelos’s astute, widely read series on ethics. Our respective areas of interest widely overlap and have come into sharper focus for the surgical community over roughly the same period of time.

It was my hope that our contributions on palliative care would emulate the qualities and quality of Dr. Angelos’s articles – commentaries that would be of interest to the entire spectrum of surgical specialties and venues of practice. While the ethics column focused on doing the right thing, we would be focused on how to do the right thing in our response to suffering. Thanks are due to ACS Surgery News for its consistent representation of the new specialty of surgical palliative care on a par with other surgical specialties. It is culturally significant that this advocacy included strong support from laypeople.

I have been gratified and am thankful for the frequent uplifting discussions and debates triggered by palliative care columns in well-thumbed copies of ACS Surgery News in our OR lounge.

I didn’t have to look far to find inspiration and direction for the advocacy of palliative care in surgical practice. My father, David D. Dunn, MD, FACS, who represented everything noble, humane, and sensible in surgery, was a community-based general surgeon practicing in an era when the “general surgeon” performed thoracic, vascular, trauma, pediatric, and plastic surgery in addition to abdominal surgery. He had extensive experience with responding to suffering in a fundamentally affirmative way. He founded the first hospice in our community to meet the needs of a proud, cantankerous, elderly man septic with a gangrenous leg who declined amputation. He also witnessed mass suffering when he commanded a field hospital tasked with the resuscitation of survivors of a liberated Nazi concentration camp. The experience could have easily destroyed him from the resulting cynicism about humanity or PTSD. But instead he claimed he learned the first step in responding to mass calamity is the resuscitation of hope. He recalled a rescued physician who was given a clean lab coat and a stethoscope even before he was given his first real meal in years. He believed the hallmarks of steadfastness and non-abandonment are the core of the surgical persona. Late in his long life that ended just before this series launched, he observed, “It’s all palliative when you get right down to it. You [meaning the next generation] have to figure out the details and do your bit.”

The future is bright to “figure out the details and do your bit” for surgeons interested in palliative care. A number of young surgeons and surgeons in training, some who have done fellowships and become ABS certified in Hospice and Palliative Medicine, have had the opportunity to be heard and their specialty field be recognized by the greater surgical community because of ACS Surgery News.

I once asked a physically and emotionally exhausted family member of an “ICU to nowhere” patient why he thought patients get “stuck” in the ICU. He answered eloquently, “People just don’t think they should die.” The prevailing biophysical and increasingly “corporate” framework for care of the seriously ill is handicapped by its inability to effectively respond to the psychological and spiritual questions raised by this comment. Inability of surgeons to reconcile personal moral imperatives with big data and corporate medicine may be contributing to burnout, one of the most frequently acknowledged problems for surgeons today. Disease management alone, even if completely evidence-based, will not break this type of gridlock nor leave patients, families, and practitioners with a lasting sense of support. We will always need a broader framework that gives us a lens through which we can see and a voice with which we can answer the serious concerns that trouble our seriously ill patients and their families. I thank ACS Surgery News for conscientiously providing us a lens and a voice over the past 7 years.

Dr. Dunn was formerly the medical director of the palliative care consultation service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot in Erie, Pa., and Chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Despite interest, few liver transplant candidates discuss advance care planning with clinicians

SAN FRANCISCO – .

“Recent studies have shown that there have been low rates of these types of discussions in all areas of medicine, not just in liver transplantation per se,” Connie W. Wang, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “We were curious to see what it looked like in our practice setting.”

In an effort to evaluate current advanced care planning documentation practices in the liver transplantation setting, she and her colleagues reviewed the medical charts of 168 adults who underwent an initial liver transplant evaluation at the University of California, San Francisco, from January 2017 to June 2017. Next, to assess readiness to complete advanced care planning among liver transplant candidates, the researchers administered the Advanced Care Planning Engagement Survey to 41 adults who underwent an initial liver transplant evaluation from March 2018 to May 2018. The survey was scored on a Likert scale of 1-4, in which a score of 4 equaled “ready” or “confident,” and a score of 5 equaled “very ready” or “very confident.”

The mean age of the 168 transplant candidates was 53 years, 35% were female, and 52% were non-Hispanic white. Only 15 patients (9%) reported completing advanced care planning prior to their liver transplant evaluation and none had legal advance care planning forms scanned or end-of-life wishes documented in the medical record. Durable power of attorney for health care was discussed with 17 patients (10%). On logistic regression analysis, only white race was associated with completion of advanced care planning (OR 4.16; P = .03), but age, Child-Pugh score, and MELD-Na score were not.

The mean age of the 41 transplant candidates who completed the Advanced Care Planning Engagement Survey was 58 years, 39% were female, and 58% were non-Hispanic white. Nearly all respondents (93%) indicated that they were ready to appoint a durable power of attorney, 85% were ready to discuss end-of-life care, and 93% were ready to ask physicians questions about medical decisions. Similarly, 93% of patients felt confident to appoint a durable power of attorney, 88% felt confident to discuss end-of-life care, and 93% felt confident to ask physicians questions about medical decisions.

“It seems like from the patients’ perspective, they are very much open to having these conversations, but there hasn’t been [the right] environment or setting to have them,” said Dr. Wang, a third-year internal medicine resident at UCSF. “Or, there may be a barrier from the provider’s perspective. Clearly, there is a huge need that can be filled.” She noted that future research should focus on development of tools to facilitate discussions and documentation between transplant clinicians, patients, and their caregivers.

One of the study authors, Jennifer C. Lai, MD, reported being a consultant for Third Rock Ventures, LLC. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Hepatol. 2018;68[S1]: Abstract 771.

SAN FRANCISCO – .

“Recent studies have shown that there have been low rates of these types of discussions in all areas of medicine, not just in liver transplantation per se,” Connie W. Wang, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “We were curious to see what it looked like in our practice setting.”

In an effort to evaluate current advanced care planning documentation practices in the liver transplantation setting, she and her colleagues reviewed the medical charts of 168 adults who underwent an initial liver transplant evaluation at the University of California, San Francisco, from January 2017 to June 2017. Next, to assess readiness to complete advanced care planning among liver transplant candidates, the researchers administered the Advanced Care Planning Engagement Survey to 41 adults who underwent an initial liver transplant evaluation from March 2018 to May 2018. The survey was scored on a Likert scale of 1-4, in which a score of 4 equaled “ready” or “confident,” and a score of 5 equaled “very ready” or “very confident.”

The mean age of the 168 transplant candidates was 53 years, 35% were female, and 52% were non-Hispanic white. Only 15 patients (9%) reported completing advanced care planning prior to their liver transplant evaluation and none had legal advance care planning forms scanned or end-of-life wishes documented in the medical record. Durable power of attorney for health care was discussed with 17 patients (10%). On logistic regression analysis, only white race was associated with completion of advanced care planning (OR 4.16; P = .03), but age, Child-Pugh score, and MELD-Na score were not.

The mean age of the 41 transplant candidates who completed the Advanced Care Planning Engagement Survey was 58 years, 39% were female, and 58% were non-Hispanic white. Nearly all respondents (93%) indicated that they were ready to appoint a durable power of attorney, 85% were ready to discuss end-of-life care, and 93% were ready to ask physicians questions about medical decisions. Similarly, 93% of patients felt confident to appoint a durable power of attorney, 88% felt confident to discuss end-of-life care, and 93% felt confident to ask physicians questions about medical decisions.

“It seems like from the patients’ perspective, they are very much open to having these conversations, but there hasn’t been [the right] environment or setting to have them,” said Dr. Wang, a third-year internal medicine resident at UCSF. “Or, there may be a barrier from the provider’s perspective. Clearly, there is a huge need that can be filled.” She noted that future research should focus on development of tools to facilitate discussions and documentation between transplant clinicians, patients, and their caregivers.

One of the study authors, Jennifer C. Lai, MD, reported being a consultant for Third Rock Ventures, LLC. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Hepatol. 2018;68[S1]: Abstract 771.

SAN FRANCISCO – .

“Recent studies have shown that there have been low rates of these types of discussions in all areas of medicine, not just in liver transplantation per se,” Connie W. Wang, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “We were curious to see what it looked like in our practice setting.”

In an effort to evaluate current advanced care planning documentation practices in the liver transplantation setting, she and her colleagues reviewed the medical charts of 168 adults who underwent an initial liver transplant evaluation at the University of California, San Francisco, from January 2017 to June 2017. Next, to assess readiness to complete advanced care planning among liver transplant candidates, the researchers administered the Advanced Care Planning Engagement Survey to 41 adults who underwent an initial liver transplant evaluation from March 2018 to May 2018. The survey was scored on a Likert scale of 1-4, in which a score of 4 equaled “ready” or “confident,” and a score of 5 equaled “very ready” or “very confident.”

The mean age of the 168 transplant candidates was 53 years, 35% were female, and 52% were non-Hispanic white. Only 15 patients (9%) reported completing advanced care planning prior to their liver transplant evaluation and none had legal advance care planning forms scanned or end-of-life wishes documented in the medical record. Durable power of attorney for health care was discussed with 17 patients (10%). On logistic regression analysis, only white race was associated with completion of advanced care planning (OR 4.16; P = .03), but age, Child-Pugh score, and MELD-Na score were not.

The mean age of the 41 transplant candidates who completed the Advanced Care Planning Engagement Survey was 58 years, 39% were female, and 58% were non-Hispanic white. Nearly all respondents (93%) indicated that they were ready to appoint a durable power of attorney, 85% were ready to discuss end-of-life care, and 93% were ready to ask physicians questions about medical decisions. Similarly, 93% of patients felt confident to appoint a durable power of attorney, 88% felt confident to discuss end-of-life care, and 93% felt confident to ask physicians questions about medical decisions.

“It seems like from the patients’ perspective, they are very much open to having these conversations, but there hasn’t been [the right] environment or setting to have them,” said Dr. Wang, a third-year internal medicine resident at UCSF. “Or, there may be a barrier from the provider’s perspective. Clearly, there is a huge need that can be filled.” She noted that future research should focus on development of tools to facilitate discussions and documentation between transplant clinicians, patients, and their caregivers.

One of the study authors, Jennifer C. Lai, MD, reported being a consultant for Third Rock Ventures, LLC. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Hepatol. 2018;68[S1]: Abstract 771.

REPORTING FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2018

Key clinical point: There is a paucity of documentation of advance care planning or identification of a durable power of attorney in the medical record of liver transplant candidates.

Major finding: Only 9% of liver transplant candidates reported completing advanced care planning prior to their liver transplant evaluations and none had legal advance care planning forms scanned or end-of-life wishes documented in the medical record.

Study details: A retrospective review of 168 adults who underwent an initial liver transplant evaluation at the University of California, San Francisco.

Disclosures: One of the study authors, Jennifer C. Lai, MD, reported being a consultant for Third Rock Ventures, LLC. The other researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Hepatol. 2018;68[S1]:Abstract 771.

Dialysis decision in elderly needs to factor in comorbidities

SAN DIEGO – The wider picture of the patient’s health and prognosis, not just chronologic age, should enter into the clinical decision to initiate dialysis, according to Bjorg Thorsteinsdottir, MD, a palliative care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“People perceive they have no choice [but treatment], and we perceive we have to do things to them until everything is lost, then we expect them to do a 180 [degree turn],” she said in a presentation at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“A 90-year-old fit individual, with minimal comorbidity living independently, would absolutely be a good candidate for dialysis, while a 75-year-old patient with bad peripheral vascular disease and dementia, living in a nursing home, would be unlikely to live longer on dialysis than off dialysis,” she said. “We need to weigh the risks and benefits for each individual patient against their goals and values. We need to be honest about the lack of benefit for certain subgroups of patients and the heavy treatment burdens of dialysis. Age, comorbidity, and frailty all factor into these deliberations and prognosis.”

More than 107,000 people over age 75 in the United States received dialysis in 2015, according to statistics gathered by the National Kidney Foundation. Yet the survival advantage of dialysis is more limited in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, Dr. Thorsteinsdottir said. “It becomes important to think about the harms of treatment.”

A 2016 study from the Netherlands found no survival advantage to dialysis, compared with conservative management among kidney failure patients aged 80 and older. The survival advantage was limited with dialysis in patients aged 70 and older who also had multiple comorbidities. (Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Apr;11(4):633-40)

In an interview, Dr. Thorsteinsdottir acknowledged that “determining who is unlikely to benefit from dialysis is complicated.” However, she said, “we know that the following comorbidities are the worst: dementia and peripheral vascular disease.”

“No one that I know of currently has an age cutoff for dialysis,” Dr. Thorsteinsdottir said in the interview, “and I do not believe the U.S. is ready for any kind of explicit limit setting by the government on dialysis treatment.”

“We must respond to legitimate concerns raised by recent studies that suggest that strong moral imperatives – to treat anyone we can treat – have created a situation where we are not pausing and asking hard questions about whether the patient in front of us is likely to benefit from dialysis,” she said in the interview. “Patients sense this and do not feel that they are given any alternatives to dialysis treatment. This needs to change.”

Dr. Thorsteinsdottir reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The wider picture of the patient’s health and prognosis, not just chronologic age, should enter into the clinical decision to initiate dialysis, according to Bjorg Thorsteinsdottir, MD, a palliative care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“People perceive they have no choice [but treatment], and we perceive we have to do things to them until everything is lost, then we expect them to do a 180 [degree turn],” she said in a presentation at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“A 90-year-old fit individual, with minimal comorbidity living independently, would absolutely be a good candidate for dialysis, while a 75-year-old patient with bad peripheral vascular disease and dementia, living in a nursing home, would be unlikely to live longer on dialysis than off dialysis,” she said. “We need to weigh the risks and benefits for each individual patient against their goals and values. We need to be honest about the lack of benefit for certain subgroups of patients and the heavy treatment burdens of dialysis. Age, comorbidity, and frailty all factor into these deliberations and prognosis.”

More than 107,000 people over age 75 in the United States received dialysis in 2015, according to statistics gathered by the National Kidney Foundation. Yet the survival advantage of dialysis is more limited in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, Dr. Thorsteinsdottir said. “It becomes important to think about the harms of treatment.”

A 2016 study from the Netherlands found no survival advantage to dialysis, compared with conservative management among kidney failure patients aged 80 and older. The survival advantage was limited with dialysis in patients aged 70 and older who also had multiple comorbidities. (Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Apr;11(4):633-40)

In an interview, Dr. Thorsteinsdottir acknowledged that “determining who is unlikely to benefit from dialysis is complicated.” However, she said, “we know that the following comorbidities are the worst: dementia and peripheral vascular disease.”

“No one that I know of currently has an age cutoff for dialysis,” Dr. Thorsteinsdottir said in the interview, “and I do not believe the U.S. is ready for any kind of explicit limit setting by the government on dialysis treatment.”

“We must respond to legitimate concerns raised by recent studies that suggest that strong moral imperatives – to treat anyone we can treat – have created a situation where we are not pausing and asking hard questions about whether the patient in front of us is likely to benefit from dialysis,” she said in the interview. “Patients sense this and do not feel that they are given any alternatives to dialysis treatment. This needs to change.”

Dr. Thorsteinsdottir reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The wider picture of the patient’s health and prognosis, not just chronologic age, should enter into the clinical decision to initiate dialysis, according to Bjorg Thorsteinsdottir, MD, a palliative care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“People perceive they have no choice [but treatment], and we perceive we have to do things to them until everything is lost, then we expect them to do a 180 [degree turn],” she said in a presentation at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“A 90-year-old fit individual, with minimal comorbidity living independently, would absolutely be a good candidate for dialysis, while a 75-year-old patient with bad peripheral vascular disease and dementia, living in a nursing home, would be unlikely to live longer on dialysis than off dialysis,” she said. “We need to weigh the risks and benefits for each individual patient against their goals and values. We need to be honest about the lack of benefit for certain subgroups of patients and the heavy treatment burdens of dialysis. Age, comorbidity, and frailty all factor into these deliberations and prognosis.”

More than 107,000 people over age 75 in the United States received dialysis in 2015, according to statistics gathered by the National Kidney Foundation. Yet the survival advantage of dialysis is more limited in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, Dr. Thorsteinsdottir said. “It becomes important to think about the harms of treatment.”

A 2016 study from the Netherlands found no survival advantage to dialysis, compared with conservative management among kidney failure patients aged 80 and older. The survival advantage was limited with dialysis in patients aged 70 and older who also had multiple comorbidities. (Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Apr;11(4):633-40)

In an interview, Dr. Thorsteinsdottir acknowledged that “determining who is unlikely to benefit from dialysis is complicated.” However, she said, “we know that the following comorbidities are the worst: dementia and peripheral vascular disease.”

“No one that I know of currently has an age cutoff for dialysis,” Dr. Thorsteinsdottir said in the interview, “and I do not believe the U.S. is ready for any kind of explicit limit setting by the government on dialysis treatment.”

“We must respond to legitimate concerns raised by recent studies that suggest that strong moral imperatives – to treat anyone we can treat – have created a situation where we are not pausing and asking hard questions about whether the patient in front of us is likely to benefit from dialysis,” she said in the interview. “Patients sense this and do not feel that they are given any alternatives to dialysis treatment. This needs to change.”

Dr. Thorsteinsdottir reported no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2018

Quick Byte: Palliative care

Rapid adoption of a key program

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

Rapid adoption of a key program

Rapid adoption of a key program

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

A physician’s response to observational studies of opioid prescribing

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

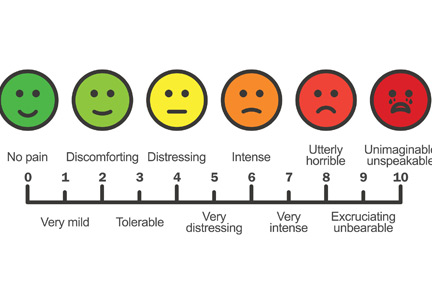

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

Palliative care update highlights role of nonspecialists

The new edition of providing care for critically ill patients, not just those clinicians actively specialized in palliative care.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th Edition, emphasizes the importance of palliative care provided by “clinicians in primary care and specialty care practices, such as oncologists,” the guideline authors stated.

The latest revision of the guideline aims to establish a foundation for “gold-standard” palliative care for people living with serious illness, regardless of diagnosis, prognosis, setting, or age, according to the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care, which published the clinical practice guidelines.

The update was developed by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP), which includes 16 national organizations with palliative care and hospice expertise, and is endorsed by more than 80 national organizations, including the American Society of Hematology and the Oncology Nurses Society.

One key reason for the update, according to the NCP, was to acknowledge that today’s health care system may not be meeting patients’ palliative care needs.

Specifically, the guidelines call on all clinicians who are not palliative specialists to integrate palliative care principles into their routine assessment of seriously ill patients with conditions such as heart failure, lung disease, and cancer.

This approach differs from the way palliative care is traditionally practiced, often by fellowship-trained physicians, trained nurses, and other specialists who provide that support.

The guidelines are organized into sections covering palliative care structure and processes, care for the patient nearing the end of life, and specific aspects of palliative care, including physical, psychological, and psychiatric; social; cultural, ethical, and legal; and spiritual, religious, and existential aspects.

“The expectation is that all clinicians caring for seriously ill patients will integrate palliative care competencies, such as safe and effective pain and symptom management and expert communication skills in their practice, and palliative care specialists will provide expertise for those with the most complex needs,” the guideline authors wrote.

Implications for treatment of oncology patients

These new guidelines represent a “blueprint for what it looks like to provide high-quality, comprehensive palliative care to people with serious illness,” said Thomas W. LeBlanc, MD, who is a medical oncologist, palliative care physician, and patient experience researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“Part of this report to is about trying to raise the game of everybody in medicine and provide a higher basic level of primary palliative care to all people with serious illness, but then also to figure out who has higher levels of needs where the specialists should be applied, since they are a scarce resource,” said Dr. LeBlanc.

An issue with that traditional model is a shortage of specialized clinicians to meet palliative care needs, said Dr. LeBlanc, whose clinical practice and research focuses on palliative care needs of patients with hematologic malignancies.

“Palliative care has matured as a field such that we are now actually facing workforce shortage issues and really fundamental questions about who needs us the most, and how we increase our reach to improve the lives of more patients and families facing serious illness,” he said in an interview.

That’s a major driver behind the emphasis in these latest guidelines on providing palliative care in the community, coordinating care, and dealing with care transitions, he added.

“I hope that this document will help to demonstrate the value and the need for palliative care specialists, and for improvements in primary care in the care of patients with hematologic diseases in general,” he said. “To me, this adds increasing legitimacy to this whole field.”

Palliative care in surgical care

These guidelines are particularly useful to surgeons in part because of their focus on what’s known as primary palliative care, said to Geoffrey P. Dunn, MD, former chair of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Surgical Palliative Care. Palliative care, the new guidelines suggest, can be implemented by nonspecialists.

Primary palliative care includes diverse skills such as breaking adverse news to patients, managing uncomplicated pain, and being able to recognize signs and symptoms of imminent demise. “These are the minimum deliverables for all people dealing with seriously ill patients,” Dr. Dunn said in an interview. “It’s palliative care that any practicing physician should be able to handle.”

Dr. Dunn concurred with Dr. LaBlanc about the workforce shortage in the palliative field. The traditional model has created a shortage of specialized clinicians to meet palliative care needs. Across the board, “staffing for palliative teams is very inconsistent,” said Dr. Dunn. “It’s a classic unfunded mandate.”

While these guidelines are a step forward in recognizing the importance of palliative care outside of the palliative care specialty, there is no reference to surgery anywhere in the text of the 141-page prepublication draft provided by the NCP, Dr. Dunn noted in the interview.

“There’s still a danger of parallel universes, where surgery is developing its own understanding of this in parallel with the more general national palliative care movement,” he said. Despite that, there is a growing connection between surgery and the broader palliative care community. That linkage is especially important given the number of seriously ill patients with high symptom burden that are seen in surgery.

“I think where surgeons are beginning to find [palliative principles] very helpful is dealing with these protracted serial discussions with families in difficult circumstances, such as how long is the life support going to be prolonged in someone with a devastating head injury, or multiple system organ failure in the elderly,” Dr. Dunn added.

The new edition of providing care for critically ill patients, not just those clinicians actively specialized in palliative care.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th Edition, emphasizes the importance of palliative care provided by “clinicians in primary care and specialty care practices, such as oncologists,” the guideline authors stated.

The latest revision of the guideline aims to establish a foundation for “gold-standard” palliative care for people living with serious illness, regardless of diagnosis, prognosis, setting, or age, according to the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care, which published the clinical practice guidelines.

The update was developed by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP), which includes 16 national organizations with palliative care and hospice expertise, and is endorsed by more than 80 national organizations, including the American Society of Hematology and the Oncology Nurses Society.

One key reason for the update, according to the NCP, was to acknowledge that today’s health care system may not be meeting patients’ palliative care needs.

Specifically, the guidelines call on all clinicians who are not palliative specialists to integrate palliative care principles into their routine assessment of seriously ill patients with conditions such as heart failure, lung disease, and cancer.

This approach differs from the way palliative care is traditionally practiced, often by fellowship-trained physicians, trained nurses, and other specialists who provide that support.

The guidelines are organized into sections covering palliative care structure and processes, care for the patient nearing the end of life, and specific aspects of palliative care, including physical, psychological, and psychiatric; social; cultural, ethical, and legal; and spiritual, religious, and existential aspects.

“The expectation is that all clinicians caring for seriously ill patients will integrate palliative care competencies, such as safe and effective pain and symptom management and expert communication skills in their practice, and palliative care specialists will provide expertise for those with the most complex needs,” the guideline authors wrote.

Implications for treatment of oncology patients

These new guidelines represent a “blueprint for what it looks like to provide high-quality, comprehensive palliative care to people with serious illness,” said Thomas W. LeBlanc, MD, who is a medical oncologist, palliative care physician, and patient experience researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“Part of this report to is about trying to raise the game of everybody in medicine and provide a higher basic level of primary palliative care to all people with serious illness, but then also to figure out who has higher levels of needs where the specialists should be applied, since they are a scarce resource,” said Dr. LeBlanc.

An issue with that traditional model is a shortage of specialized clinicians to meet palliative care needs, said Dr. LeBlanc, whose clinical practice and research focuses on palliative care needs of patients with hematologic malignancies.

“Palliative care has matured as a field such that we are now actually facing workforce shortage issues and really fundamental questions about who needs us the most, and how we increase our reach to improve the lives of more patients and families facing serious illness,” he said in an interview.

That’s a major driver behind the emphasis in these latest guidelines on providing palliative care in the community, coordinating care, and dealing with care transitions, he added.

“I hope that this document will help to demonstrate the value and the need for palliative care specialists, and for improvements in primary care in the care of patients with hematologic diseases in general,” he said. “To me, this adds increasing legitimacy to this whole field.”

Palliative care in surgical care

These guidelines are particularly useful to surgeons in part because of their focus on what’s known as primary palliative care, said to Geoffrey P. Dunn, MD, former chair of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Surgical Palliative Care. Palliative care, the new guidelines suggest, can be implemented by nonspecialists.

Primary palliative care includes diverse skills such as breaking adverse news to patients, managing uncomplicated pain, and being able to recognize signs and symptoms of imminent demise. “These are the minimum deliverables for all people dealing with seriously ill patients,” Dr. Dunn said in an interview. “It’s palliative care that any practicing physician should be able to handle.”

Dr. Dunn concurred with Dr. LaBlanc about the workforce shortage in the palliative field. The traditional model has created a shortage of specialized clinicians to meet palliative care needs. Across the board, “staffing for palliative teams is very inconsistent,” said Dr. Dunn. “It’s a classic unfunded mandate.”

While these guidelines are a step forward in recognizing the importance of palliative care outside of the palliative care specialty, there is no reference to surgery anywhere in the text of the 141-page prepublication draft provided by the NCP, Dr. Dunn noted in the interview.

“There’s still a danger of parallel universes, where surgery is developing its own understanding of this in parallel with the more general national palliative care movement,” he said. Despite that, there is a growing connection between surgery and the broader palliative care community. That linkage is especially important given the number of seriously ill patients with high symptom burden that are seen in surgery.

“I think where surgeons are beginning to find [palliative principles] very helpful is dealing with these protracted serial discussions with families in difficult circumstances, such as how long is the life support going to be prolonged in someone with a devastating head injury, or multiple system organ failure in the elderly,” Dr. Dunn added.

The new edition of providing care for critically ill patients, not just those clinicians actively specialized in palliative care.

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th Edition, emphasizes the importance of palliative care provided by “clinicians in primary care and specialty care practices, such as oncologists,” the guideline authors stated.

The latest revision of the guideline aims to establish a foundation for “gold-standard” palliative care for people living with serious illness, regardless of diagnosis, prognosis, setting, or age, according to the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care, which published the clinical practice guidelines.

The update was developed by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP), which includes 16 national organizations with palliative care and hospice expertise, and is endorsed by more than 80 national organizations, including the American Society of Hematology and the Oncology Nurses Society.

One key reason for the update, according to the NCP, was to acknowledge that today’s health care system may not be meeting patients’ palliative care needs.

Specifically, the guidelines call on all clinicians who are not palliative specialists to integrate palliative care principles into their routine assessment of seriously ill patients with conditions such as heart failure, lung disease, and cancer.

This approach differs from the way palliative care is traditionally practiced, often by fellowship-trained physicians, trained nurses, and other specialists who provide that support.

The guidelines are organized into sections covering palliative care structure and processes, care for the patient nearing the end of life, and specific aspects of palliative care, including physical, psychological, and psychiatric; social; cultural, ethical, and legal; and spiritual, religious, and existential aspects.

“The expectation is that all clinicians caring for seriously ill patients will integrate palliative care competencies, such as safe and effective pain and symptom management and expert communication skills in their practice, and palliative care specialists will provide expertise for those with the most complex needs,” the guideline authors wrote.

Implications for treatment of oncology patients

These new guidelines represent a “blueprint for what it looks like to provide high-quality, comprehensive palliative care to people with serious illness,” said Thomas W. LeBlanc, MD, who is a medical oncologist, palliative care physician, and patient experience researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“Part of this report to is about trying to raise the game of everybody in medicine and provide a higher basic level of primary palliative care to all people with serious illness, but then also to figure out who has higher levels of needs where the specialists should be applied, since they are a scarce resource,” said Dr. LeBlanc.

An issue with that traditional model is a shortage of specialized clinicians to meet palliative care needs, said Dr. LeBlanc, whose clinical practice and research focuses on palliative care needs of patients with hematologic malignancies.

“Palliative care has matured as a field such that we are now actually facing workforce shortage issues and really fundamental questions about who needs us the most, and how we increase our reach to improve the lives of more patients and families facing serious illness,” he said in an interview.

That’s a major driver behind the emphasis in these latest guidelines on providing palliative care in the community, coordinating care, and dealing with care transitions, he added.

“I hope that this document will help to demonstrate the value and the need for palliative care specialists, and for improvements in primary care in the care of patients with hematologic diseases in general,” he said. “To me, this adds increasing legitimacy to this whole field.”

Palliative care in surgical care

These guidelines are particularly useful to surgeons in part because of their focus on what’s known as primary palliative care, said to Geoffrey P. Dunn, MD, former chair of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Surgical Palliative Care. Palliative care, the new guidelines suggest, can be implemented by nonspecialists.

Primary palliative care includes diverse skills such as breaking adverse news to patients, managing uncomplicated pain, and being able to recognize signs and symptoms of imminent demise. “These are the minimum deliverables for all people dealing with seriously ill patients,” Dr. Dunn said in an interview. “It’s palliative care that any practicing physician should be able to handle.”

Dr. Dunn concurred with Dr. LaBlanc about the workforce shortage in the palliative field. The traditional model has created a shortage of specialized clinicians to meet palliative care needs. Across the board, “staffing for palliative teams is very inconsistent,” said Dr. Dunn. “It’s a classic unfunded mandate.”

While these guidelines are a step forward in recognizing the importance of palliative care outside of the palliative care specialty, there is no reference to surgery anywhere in the text of the 141-page prepublication draft provided by the NCP, Dr. Dunn noted in the interview.

“There’s still a danger of parallel universes, where surgery is developing its own understanding of this in parallel with the more general national palliative care movement,” he said. Despite that, there is a growing connection between surgery and the broader palliative care community. That linkage is especially important given the number of seriously ill patients with high symptom burden that are seen in surgery.

“I think where surgeons are beginning to find [palliative principles] very helpful is dealing with these protracted serial discussions with families in difficult circumstances, such as how long is the life support going to be prolonged in someone with a devastating head injury, or multiple system organ failure in the elderly,” Dr. Dunn added.

Antipsychotic drugs failed to shorten ICU delirium

The antipsychotic medications in patients in intensive care, new research has found.

In a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers reported the results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 566 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock and hypoactive or hyperactive delirium. Participants were randomized either to a maximum of 20 mg IV haloperidol daily, maximum 40 mg ziprasidone daily, or placebo.

At the end of the 14-day intervention period, the placebo group had a median of 8.5 days alive without delirium or coma, the haloperidol group had a median of 7.9 days, and the ziprasidone group had a median of 8.7 days. The difference between groups was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences between the three groups in the secondary end point of duration of delirium and coma, 30-day and 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Timothy D. Girard, MD, from the department of critical care at the University of Pittsburgh, and his coauthors wrote that their findings echoed those of two previous placebo-controlled trials in smaller numbers of ICU patients.

“One possible reason that we found no evidence that the use of haloperidol or ziprasidone resulted in a fewer days with delirium or coma than placebo is that the mechanism of brain dysfunction that is considered to be targeted by antipsychotic medications – increased dopamine signaling – may not play a major role in the pathogenesis of delirium during critical illness,” they wrote.

“In the current trial, approximately 90% of the patients received one or more doses of sedatives or analgesics, and the doses of sedatives and offtrial antipsychotic medications and the durations of exposures to those agents were similar in all trial groups,” the authors added.

Most of the patients in the trial had hypotensive delirium, which made it difficult to assess the effects of antipsychotics on hypertensive delirium.

The authors also commented that the patients enrolled were a mixed group, so their findings did not rule out the possibility that certain subgroups of patients – such as nonintubated patients with hyperactive delirium, those with alcohol withdrawal, or with other delirium phenotypes – may still benefit from antipsychotics.

Patients treated with ziprasidone were more likely to experience prolongation of the corrected QT interval. Two patients in the haloperidol group developed torsades de pointes but neither had received haloperidol in the 4 days preceding the onset of the arrhythmia.

One patient in each group – including the placebo group – experienced extrapyramidal symptoms and had treatment withheld. One patient in the haloperidol group also had the trial drug withheld because of suspected neuroleptic malignant syndrome, but this was later ruled out, and one patient had haloperidol withheld because of dystonia.

The dose of haloperidol used in the study was considered high, the authors said, but they left open the possibility that even higher doses might help. However, they also noted that doses of 25 mg and above were known to have adverse effects on cognition, which is why they chose the 20-mg dosage.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center. Most authors declared support from the NIH or VA during the course of the study. Four authors also reported fees and grants from private industry outside the context of the study.

SOURCE: Girard TD et al. N Engl J Med.2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808217.

In a comment published with this study, Thomas P. Bleck, MD, of the department of neurologic sciences at Rush Medical College, Chicago, wrote, “A change in mental status in a patient in intensive care can be one of the most vexing problems. In the past 2 decades, the idea has arisen that antipsychotic drugs – and particularly dopamine antagonists, which ameliorate thought disorders in psychotic patients – could help patients with disordered thinking in other contexts, such as the intensive care unit. However, yet another trial has now called this idea into question.”

He noted that, in the study group, a bolus of placebo was just as effective as a bolus of active medication, which may be because of the majority of patients having hypoactive delirium, which the active drugs may not impact.

“I would still consider using dopamine agonists in patients at imminent risk of injurious behaviors but have less confidence in their benefits than I once had,” Dr. Bleck wrote.

Dr. Bleck did not report any conflicts of interest.

In a comment published with this study, Thomas P. Bleck, MD, of the department of neurologic sciences at Rush Medical College, Chicago, wrote, “A change in mental status in a patient in intensive care can be one of the most vexing problems. In the past 2 decades, the idea has arisen that antipsychotic drugs – and particularly dopamine antagonists, which ameliorate thought disorders in psychotic patients – could help patients with disordered thinking in other contexts, such as the intensive care unit. However, yet another trial has now called this idea into question.”

He noted that, in the study group, a bolus of placebo was just as effective as a bolus of active medication, which may be because of the majority of patients having hypoactive delirium, which the active drugs may not impact.

“I would still consider using dopamine agonists in patients at imminent risk of injurious behaviors but have less confidence in their benefits than I once had,” Dr. Bleck wrote.

Dr. Bleck did not report any conflicts of interest.

In a comment published with this study, Thomas P. Bleck, MD, of the department of neurologic sciences at Rush Medical College, Chicago, wrote, “A change in mental status in a patient in intensive care can be one of the most vexing problems. In the past 2 decades, the idea has arisen that antipsychotic drugs – and particularly dopamine antagonists, which ameliorate thought disorders in psychotic patients – could help patients with disordered thinking in other contexts, such as the intensive care unit. However, yet another trial has now called this idea into question.”

He noted that, in the study group, a bolus of placebo was just as effective as a bolus of active medication, which may be because of the majority of patients having hypoactive delirium, which the active drugs may not impact.

“I would still consider using dopamine agonists in patients at imminent risk of injurious behaviors but have less confidence in their benefits than I once had,” Dr. Bleck wrote.

Dr. Bleck did not report any conflicts of interest.

The antipsychotic medications in patients in intensive care, new research has found.

In a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers reported the results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 566 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock and hypoactive or hyperactive delirium. Participants were randomized either to a maximum of 20 mg IV haloperidol daily, maximum 40 mg ziprasidone daily, or placebo.

At the end of the 14-day intervention period, the placebo group had a median of 8.5 days alive without delirium or coma, the haloperidol group had a median of 7.9 days, and the ziprasidone group had a median of 8.7 days. The difference between groups was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences between the three groups in the secondary end point of duration of delirium and coma, 30-day and 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Timothy D. Girard, MD, from the department of critical care at the University of Pittsburgh, and his coauthors wrote that their findings echoed those of two previous placebo-controlled trials in smaller numbers of ICU patients.

“One possible reason that we found no evidence that the use of haloperidol or ziprasidone resulted in a fewer days with delirium or coma than placebo is that the mechanism of brain dysfunction that is considered to be targeted by antipsychotic medications – increased dopamine signaling – may not play a major role in the pathogenesis of delirium during critical illness,” they wrote.

“In the current trial, approximately 90% of the patients received one or more doses of sedatives or analgesics, and the doses of sedatives and offtrial antipsychotic medications and the durations of exposures to those agents were similar in all trial groups,” the authors added.

Most of the patients in the trial had hypotensive delirium, which made it difficult to assess the effects of antipsychotics on hypertensive delirium.

The authors also commented that the patients enrolled were a mixed group, so their findings did not rule out the possibility that certain subgroups of patients – such as nonintubated patients with hyperactive delirium, those with alcohol withdrawal, or with other delirium phenotypes – may still benefit from antipsychotics.

Patients treated with ziprasidone were more likely to experience prolongation of the corrected QT interval. Two patients in the haloperidol group developed torsades de pointes but neither had received haloperidol in the 4 days preceding the onset of the arrhythmia.

One patient in each group – including the placebo group – experienced extrapyramidal symptoms and had treatment withheld. One patient in the haloperidol group also had the trial drug withheld because of suspected neuroleptic malignant syndrome, but this was later ruled out, and one patient had haloperidol withheld because of dystonia.

The dose of haloperidol used in the study was considered high, the authors said, but they left open the possibility that even higher doses might help. However, they also noted that doses of 25 mg and above were known to have adverse effects on cognition, which is why they chose the 20-mg dosage.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center. Most authors declared support from the NIH or VA during the course of the study. Four authors also reported fees and grants from private industry outside the context of the study.

SOURCE: Girard TD et al. N Engl J Med.2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808217.

The antipsychotic medications in patients in intensive care, new research has found.

In a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers reported the results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 566 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock and hypoactive or hyperactive delirium. Participants were randomized either to a maximum of 20 mg IV haloperidol daily, maximum 40 mg ziprasidone daily, or placebo.

At the end of the 14-day intervention period, the placebo group had a median of 8.5 days alive without delirium or coma, the haloperidol group had a median of 7.9 days, and the ziprasidone group had a median of 8.7 days. The difference between groups was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences between the three groups in the secondary end point of duration of delirium and coma, 30-day and 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Timothy D. Girard, MD, from the department of critical care at the University of Pittsburgh, and his coauthors wrote that their findings echoed those of two previous placebo-controlled trials in smaller numbers of ICU patients.

“One possible reason that we found no evidence that the use of haloperidol or ziprasidone resulted in a fewer days with delirium or coma than placebo is that the mechanism of brain dysfunction that is considered to be targeted by antipsychotic medications – increased dopamine signaling – may not play a major role in the pathogenesis of delirium during critical illness,” they wrote.

“In the current trial, approximately 90% of the patients received one or more doses of sedatives or analgesics, and the doses of sedatives and offtrial antipsychotic medications and the durations of exposures to those agents were similar in all trial groups,” the authors added.

Most of the patients in the trial had hypotensive delirium, which made it difficult to assess the effects of antipsychotics on hypertensive delirium.

The authors also commented that the patients enrolled were a mixed group, so their findings did not rule out the possibility that certain subgroups of patients – such as nonintubated patients with hyperactive delirium, those with alcohol withdrawal, or with other delirium phenotypes – may still benefit from antipsychotics.

Patients treated with ziprasidone were more likely to experience prolongation of the corrected QT interval. Two patients in the haloperidol group developed torsades de pointes but neither had received haloperidol in the 4 days preceding the onset of the arrhythmia.

One patient in each group – including the placebo group – experienced extrapyramidal symptoms and had treatment withheld. One patient in the haloperidol group also had the trial drug withheld because of suspected neuroleptic malignant syndrome, but this was later ruled out, and one patient had haloperidol withheld because of dystonia.

The dose of haloperidol used in the study was considered high, the authors said, but they left open the possibility that even higher doses might help. However, they also noted that doses of 25 mg and above were known to have adverse effects on cognition, which is why they chose the 20-mg dosage.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center. Most authors declared support from the NIH or VA during the course of the study. Four authors also reported fees and grants from private industry outside the context of the study.

SOURCE: Girard TD et al. N Engl J Med.2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808217.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE